3 minute read

Two | The Institute of Archaeology 1957-1959

from Digging Deep

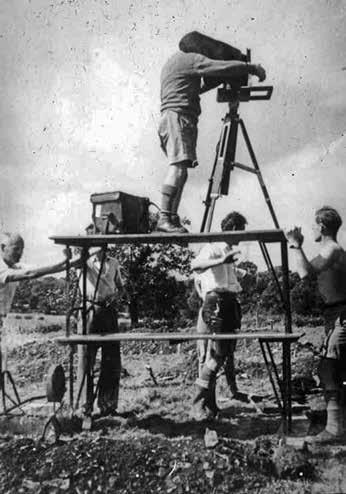

The Institute was housed in St John’s Lodge on the Inner Circle of Regent’s Park. It is a grand Palladian building dating back to 1812, that had a succession of lordly owners, including the 3rd Marquess of Bute, then reputedly the richest man in the world. When sold to the Brunei royal family in 1994 for £40 million, it was the most expensive house in Great Britain. However, between 1937 and 1958, it was the home of the Institute of Archaeology, founded by Sir Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler. One walked through a grand entrance into a hall giving immediate access to the library. The basement housed the photography studio run by Maurice Cookson, “Cookie”, and his assistant Mrs Conlon. Mr Stewart taught surveying, and there was a conservation laboratory under the aegis of Ione Gedye and Henry Hodges. That most vital of venues, the tearoom, was located on the ground floor, while upstairs there were staff offices, to which I was ushered to meet Mr Sheppard Frere, who was to teach me all about the Romans. The students for the Postgraduate Diploma were distributed across the various specialities from Roman to Palaeolithic to Middle Eastern and European prehistory. I was one of just two in Frere’s Roman class, the other being John Ellison, a classics graduate from Oxford. But we all joined forces to attend the practical courses on photography, conservation and surveying. Hence, my first lecture on the 3rd October by Mr Cookson was attended by eight students. There were rather more for Mr Frere’s lectures because we were joined by classics students from nearby Bedford College. The Institute was very welcoming. The tearoom was egalitarian, staff and students mingled. The course I followed reflected Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s resolve that we should be well grounded in the practical as well as the academic sides of the discipline. Conservation included sticking together sherds into a whole pot. We surveyed round the Institute building to the background noise of the lions in the nearby London Zoo. Cookie had been Wheeler’s site photographer for years. He used a big mahogany box camera and rightfully imparted the imperative to photograph only the clearest and cleanest targets. He used half-plate film, and explained the importance of stopping down to f45 in order to ensure everything was in focus, and exposed the camera by lifting off the lens hood for about one third of a second, manually. I wonder how he would have adapted to the digital photography I use today, but I owe him a considerable debt for his sometimes rather abrasive criticism of some of my earlier efforts. Mrs Conlon was always on hand to counter his critical barks with soothing encouragement.

Mr Frere was a formidable scholar with a Cambridge classics degree and considerable experience excavating Roman sites, including post-war Canterbury. I found too, that my course also covered the British Iron Age as a prelude to the Roman annexation. John Ellison and I were given tutorials in his office, and these included translating Roman inscriptions. The first of these somewhat forbidding experiences involved him placing in front of us a Latin inscription to translate. My problem was that the Romans were very parsimonious when it came to using marble, and abbreviated almost every word. So my first text began with the letter L. I looked at it long and hard while his eyes bored into me, until I suggested, tentatively, “50?” “Oh, Glory!” he murmured. I should have said Lucius, someone’s name.

I went up to the Institute most weekdays on my NSU Quickly, through Battersea Park and Hyde Park. On Monday 21st October, I arrived to find everyone there in mourning, for on the 19th October, my 18th birthday, Gordon Childe had died in his native Australia. It was only a few months since he had retired on reaching the age of 65, and as the news seeped out, it seemed that he had fallen to his death from a cliff top in the Blue Mountains known as Govett’s Leap. Those in the know at the Institute were aware of his depression, ill health and resolve to commit suicide. Fifty-one years later I paid a pilgrimage to Govett’s Leap. We booked accommodation via the internet and found to our surprise that the house had been the childhood home of Gordon Childe. The owner had a photograph of him in his mother’s arms in the garden, so Polly took a photo of me in exactly the same spot.

I greatly enjoyed my first term. It ended on the 8th December, and the next day I began my holiday job to pay the necessary £23 for my fees by working at the Post Office. The new term began with a setback. On my way home I unwisely cut between a stationary bus and the kerb when the lights turned green and the bus turning left, hemmed me against a metal railing. I was untouched, but my trusty NSU Quickly was badly damaged. Going up for lectures now involved a borrowed

The iron portals of St Catharine's College, Cambridge, swung open for me in October 1959.