The notion of ‘spaces becoming places’ through the involvement of an artist in the design process, often in collaboration with an architect or landscape architect, saw a resurgence in the mid-twentieth century in the United States, Mexico and France (under the villes nouvelles public art programme). In Britain Victor Pasmore’s role in the development of the new town of Peterlee in 1955, was the main precedent for an artist’s vision informing the wider environment. Pasmore created an abstract, concrete pavilion that would become the centre of a housing estate, creating at once an artwork, a bridge and a gathering point. From the mid-1970s, the Arts Council of Great Britain promoted public art, initially through a scheme then entitled Art in Public Spaces led by the visual arts officer Alister Warman. Regional initiatives followed, with the development corporations and garden festivals supporting policies and programmes of public art. As a curator of public art, the integration of art within architecture and the public realm has formed the core of my focus. Whilst more common today, it is still rare to have the opportunity to invite an artist to design public spaces and it has been a pleasure to work with Tess Jaray on a number of her public commissions.

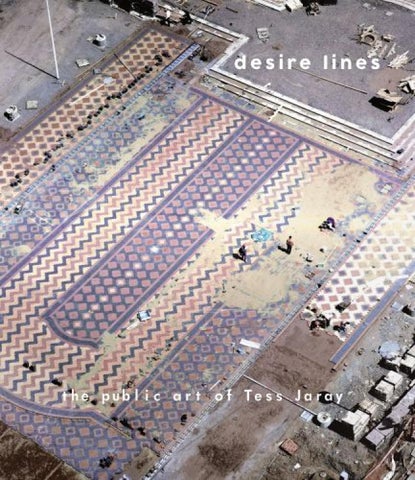

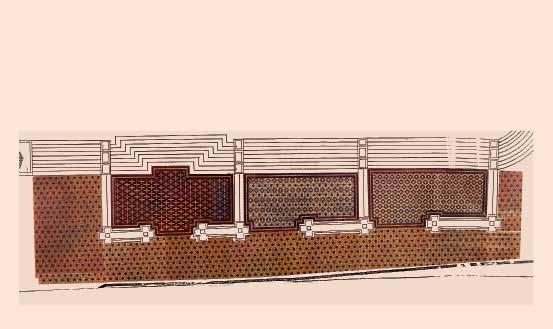

As sculpture co-ordinator for the Stoke-on-Trent National Garden Festival in 1986, I invited Jaray to propose a grand design for the main entrance pavement, to extend underneath the elegant greenhouse structure designed by the Festival’s architects, Sebire Allsopp (p.21). Following Jaray’s minimalist terrazzo floor at Victoria Station (1985; p.11), these exotically rich colours and patterning of her brick designs represented a step forward in her work, yet one entirely consistent with her studio practice. Possibly, few of the Festival visitors may

have realised that they were walking across an artistdesigned brick ‘tapestry’ yet the resultant artwork entirely transformed the experience of entering the site.

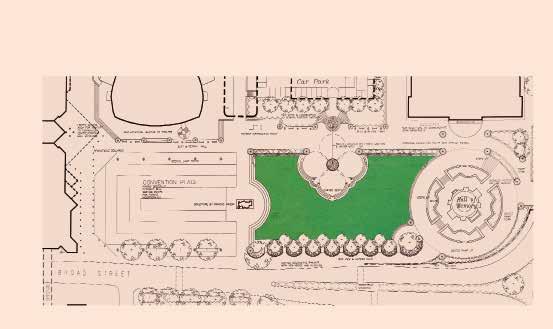

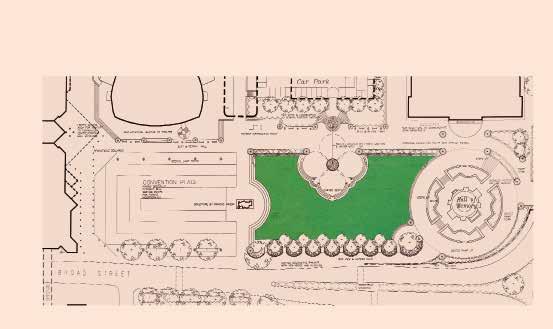

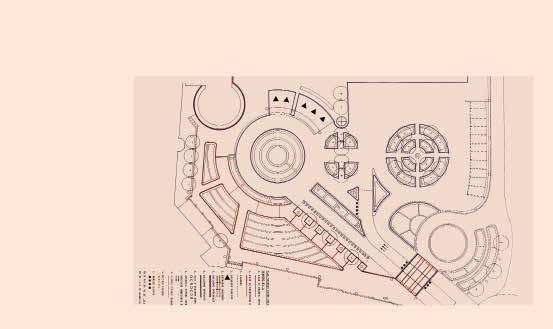

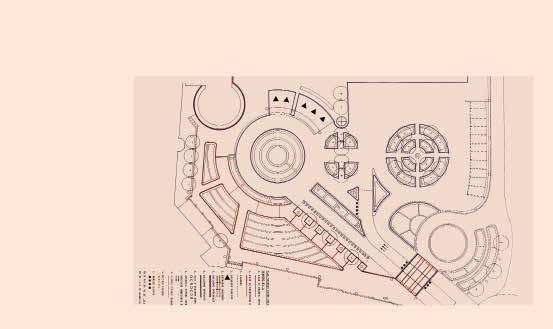

Although the Festival was a temporary event, after six months the brick pavers were relocated to the Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham, which was then upgrading its public space. Jaray reconfigured the original design for a circular public courtyard area and this remained in place until the early 2000s. Shortly after this commission, Birmingham City Council – after much prompting –adopted our recommendation for a ‘1 percent for Art’ policy in relation to the redevelopment of Centenary Square and International Convention Centre project. In 1988 Jaray was selected for the design of the ‘new’ Centenary Square: a public space originally designed in the 1930s and partially realised after the Second World War. Jaray was duly appointed as the artist member of the City Architect’s design team and there followed an intensive concept and detailed design phase.

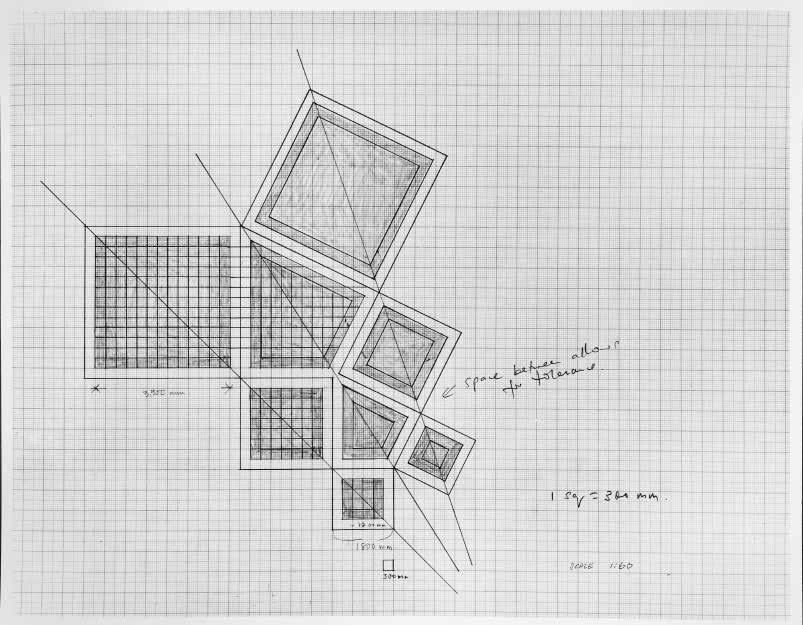

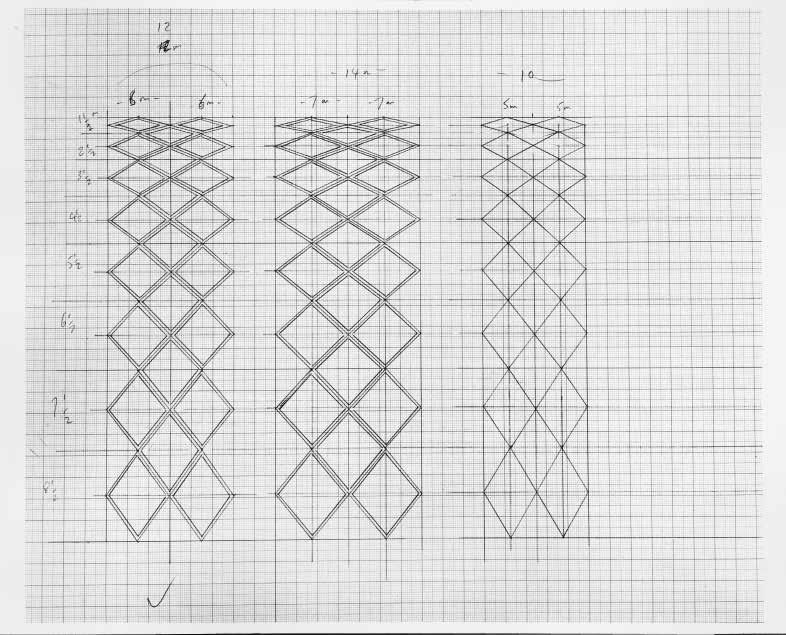

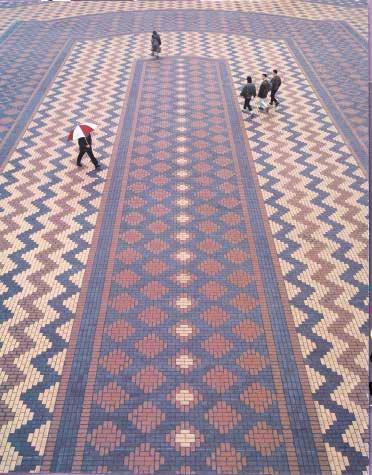

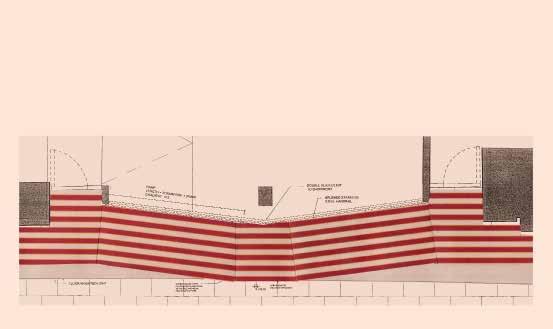

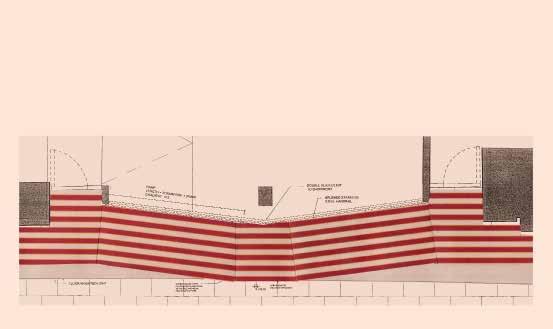

For the pavement, Jaray again chose to work in brick, designing a magnificent ‘oriental carpet’ that appears to unfurl from the Convention Centre. She also worked closely with fellow artist Tom Lomax on elements including the grand decorative metal screen that separated the square from Broad Street, the street furniture, lighting columns, litter bins and tree grids. Working in the pre-computer era, Jaray made scores of meticulous drawings for the scheme, a small selection of which are reproduced here.

Jaray’s Centenary Square successfully brought together the disparate surrounding architecture. It embraced the 1930s Hall of Memory and various sculptures, and it formed an effective stage for civic ceremonies, installations and events. Paradise Bridge,

also designed by Jaray, linked the new square with the modernist Central Library complex. As Paul Hills wrote:

Centenary Square is a place for people […] It owes its intimacy and spaciousness to the collaboration of the artist Tess Jaray with the City Architects Design Team. From simple materials, rectangular bricks in four colours, Jaray has created patterns related to the scale of the foot, yet extending and repeating with a magnificent sweep. 1

For the first time, Birmingham boasted a grand-scale public place of international status. Jaray’s approach offered an exemplary model of an artist’s environmental practice in the urban realm and set a benchmark for standards of public art in the UK. Ironically, Paradise Bridge may be the only element of Jaray’s grand vision that remains following Birmingham’s latest competition for the redesign of the square – a move depressingly consistent with the city’s habitual capacity to destroy its urban fabric in the quest to reinvent itself.

Jaray’s reputation was firmly established as a result of Birmingham’s multi-award-winning new square and invitations for further floor-based commissions followed in quick succession: Wakefield Cathedral Precinct, Leeds Infirmary, the British Embassy in Moscow. Immediately after Centenary Square, Sir Peter (now Lord) Palumbo, Chair of the Arts Council of Great Britain, invited Jaray to carry out a small but highly prestigious commission: the design of his roof terrace at the Arts Council’s new headquarters in Great Peter Street, London. This exquisite

1 Paul Hills, ‘Art at the International Convention Centre’, brochure, Public Art Commissions Agency, Birmingham, 1988.

work was created in the lavish materials of green slate and marble – very different from the warm rich tones of brick pavers but eminently suited to this sophisticated terrace in Westminster.

The momentum towards greater collaboration between artists and architects, explored at the ground-breaking Art & Architecture conference at the ICA in 1982, was propelled further in the early 1990s. Whilst chairing Public Art Forum with the new President of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Richard MacCormac, we formed an Alliance of Art, Architecture and Design: this was duly launched as a fixed term initiative at the RIBA with a panel consisting of Jaray, Palumbo, MacCormac and myself. Events and workshops followed, including one major event focusing on ‘Gateways for the Millennium’ with 120 artists, architects, landscape architects, philosophers, curators and critics taking over the whole RIBA building.

Dialogues between artists and architects fostered by the Alliance led to many future collaborative commissions. Today artists as members of design teams have become common. Recently I had the pleasure of working with Jaray again, brokering a collaboration between her and the architect Glyn Emrys for an integrated terrazzo pavement as part of a new development in Newman Street, London. We were able to extend her floor-based commission into the building’s interior. Emrys designed wall areas to accommodate the artist’s series of prints inspired by WG Sebald. Each image was juxtaposed with Sebald’s text. In this commission it was both satisfying and apt to see Jaray’s studio practice united with her work in the public realm.

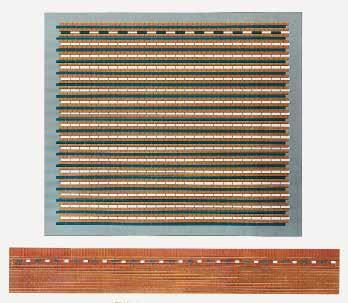

Proposed brick pavings

Brownhill’s Factory, Stoke-on-Trent

Proposed brick pavings

Brownhill’s Factory, Stoke-on-Trent

CENTENARY SQUARE

BRICK PAVING WITH STONE STEPS, WALLS & PLANTERS, METAL STREET LIGHTS, RAILINGS & STREET FURNITURE

BIRMINGHAM, UK

COMMISSIONED BY BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL WITH PACA IN COLLABORATION WITH TOM LOMAX & BIRMINGHAM CITY ARCHITECTS

Second City Finds Its Feet Richard Cork

The Times, 15 April 1991

Bullied, polluted and throttled for decades by the city’s obsession with traffic flow, the people of Birmingham are at last re-emerging from their subway-ridden oppression. Having suffered the tyranny of the Inner Ring Road ever since it was hatched in the post-war period they now find that the planners are attempting to release them from its coils. Nowhere more spectacular than in the re-modelled Centenary Square: an immense open space dedicated to the pedestrian rather than the car.

Discovering such an unexpected sanctuary in the heart of this beleaguered city is a tonic. Its aptly named Paradise Bridge has been flung over the road that once so noisily divided Centenary Square from the Victorian stateliness of the area around the town hall and art gallery. Astounding pedestrians, it is reserved for them alone as they walk, in unaccustomed serenity towards an expanse of richly patterned paving in brick, designed by the artist Tess Jaray. Quiet yet rigorous, its rhythm is first asserted outside the Hall of Memory, erected soon after the First World War and guarded by bronze figures redolent of heroism, vigilance and grief.

Jaray’s sinuous lines, honouring the Birmingham tradition of red and blue brick in its buildings, curve round the Hall like concentric rings spreading outwards from a momentous splash. They gently take command of our feet, leading them round the Hall and towards the arena where the main part of her pavement has been installed.

It unrolls in front of us with the steady, unforced authority of an oriental carpet. Rippling at the edges, its design grows in complexity as it approaches the centre of the Square. Alternating sections animated by zigzags, and bands filled with lozenges of colour, it pushes forward a drive as irresistible as a powerful mosaic floor

running up a cathedral nave.

But Jaray never allows the sense of exultation to lose sight of a human scale. This is a pavement softly attuned to the needs of the individual walker, and the figures appear reassuringly at home as they negotiate the individual components of the pattern she has devised.

The colours accentuate the air of welcome it offers. On a dry, warm day the overall hue is reminiscent of terracotta, interspersed with pale mustard, parched ochre, sunbaked orange and a refreshing use of darker, blue-tinged elements. It serves memories of dusty Renaissance piazzas, and Jaray acknowledges that Italy has provided her with indispensible sources of inspiration.

At Centenary Square, however, she was allowed to design light fittings, benches and even litter-bins as well as the pavement itself. These structures, in elegant yet sturdy iron-work, indicate her respect for the still surviving Victorian street furniture elsewhere in the city. But they also possess a lightness of touch and a leaning towards simplification, which identify them as late twentieth century in feeling. They certainly chime with the sensibility enlivening the pavement, and also provide congenial surroundings for the water sculpture produced by Tom Lomax.

How did a painter of her calibre manage to secure such a monumental and all-embracing civic commission? Jaray had previously proved her aptitude for multi-dimensional design by producing the plum-coloured terrazzo concourse at Victoria Station, and a decorative brickwork floor for Stoke-on-Trent Garden Festival.

The Symphony Hall, where Simon Rattle will conduct the first concert tonight, has been given no architectural identity of its own. It is tucked away from view on the left of

the entrance, one more anonymous unit inside a building with no time for asserting the sense of occasion which the Symphony Hall clearly needs.

In one respect, though, the Convention Centre does deserve praise. Its upper storeys provide panoramic views of the paving below, and from here the full, sensuous extent of Jaray’s achievement becomes apparent.

WAKEFIELD CATHEDRAL PRECINCT

BRICK PAVING WITH STONE STEPS, SEATING & STONE PLANTERS, BRONZE STREET LIGHTS & METAL STREET FURNITURE PLANTERS

COMMISSIONED BY WAKEFIELD METROPOLITAN DISTRICT COUNCIL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH ARTS IN HEALTHCARE

UK

JUBILEE SQUARE BRICK WALLS, METAL STREET FURNITURE & FIVE SCULPTURES

BY TOM LOMAX

BY TOM LOMAX

LEEDS, UK

COMMISSIONED BY ARTS IN HEALTHCARE & LEEDS TEACHING HOSPITALS NHS TRUST IN COLLABORATION WITH TOM LOMAX & LLEWELYN DAVIES ARCHITECTS

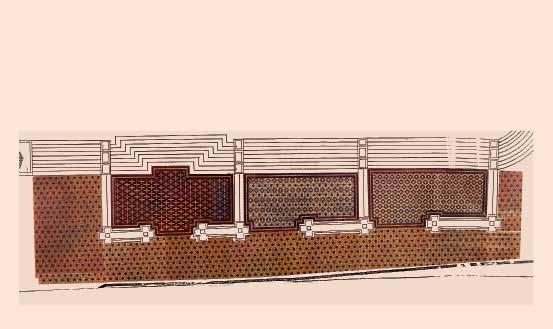

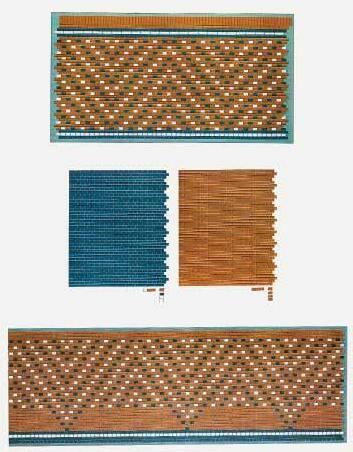

Brick designs for vent (left) and for long containing wall (right)

Brick designs for vent (left) and for long containing wall (right)

COMMISSIONED BY EMRYS ARCHITECTS FOR GREAT PORTLAND ESTATES WITH MODUS OPERANDI

Published in 2016 by Ridinghouse 46 Lexington Street

London

W1F 0LP

United Kingdom ridinghouse.co.uk

Publisher: Doro Globus

Publishing Manager: Louisa Green

Publishing Associate: Daniel Griffiths

Publishing Assistant: Jay Drinkall

Distributed in the UK and Europe by Cornerhouse Publications c/o Home

2 Tony Wilson Place

Manchester

M15 4FN

United Kingdom cornerhousepublications.org

Distributed in the US by RAM Publications + Distribution, Inc.

2525 Michigan Avenue

Building A2

Santa Monica

CA 90404

United States rampub.com

Images © Tess Jaray Texts © the authors

For the book in this form © Ridinghouse

Proofread by Dorothy Feaver

Designed by Georgia Vaux

Production by Louise Ramsay

Set in Neutra Text and Not Courier Sans

Repro by XY Digital Ltd

Printed in Slovenia by DZS Grafik

ISBN 978 1 909932 35 8

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any other information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguingin-Publication Data: A full catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Richard Bryant, Courtesy PACA. Sharon Morris: pp.18–19

Courtesy PACA: pp.23, 26–29

Rod Dorling: pp.33, 35, 37–39

John Riddy: pp.42–43, 46–47, back cover

Jerry Hardman Jones/Public Arts

1992: pp.51, 54–55

Courtesy Arts in Healthcare: pp.59, 62

Martin Hewitt, courtesy Coventry and Warwick NHS Trust: pp.72–73

Alan Williams: pp.77, 78 (bottom), 79

Martine Hamilton Knight: pp.83–85

Front cover: Centenary Square, Birmingham, UK

Back cover: Arts Council of Great Britain roof terrace, 1991

Images photographed by Sam Roberts Photography unless noted below