PREFACE 8

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9

INTRODUCTION 11

CLOSE TO THE PARKS

Axton House 22

Gohmann House 34

Dearie House 44

Assumption Green 54

Dominican Sisters Chapel 60

Passionist Center 64

Bland House 70

CLOSE TO THE RIVER

Roseman House 86

Fisher House 92

Hinson House 100

Stone House 108

River Road House 114

Woodstone House 120

Arthouse I 126

Arthouse II 130

Orsini-Heath House 134

METROPOLITAN PROJECTS

Performing and Visual Arts Center 142

Arts and Sciences Building 148

German–Carter House 154

619/621 Magnolia 164

Urban School of Art and Design 168

Gallery Square 172

Hagan Office Building 178

BCH Offices 188

Sky Chapel and Contemplative Garden 194

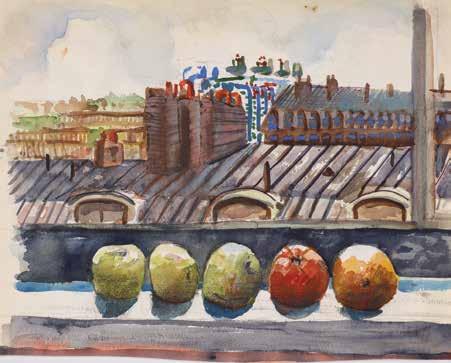

As an architecture student nearing the end of several months of study and travel across Europe in 1978, I found myself in Paris lodging in a small room on the sixth floor of a nineteenth-century walk-up pension. Viewed through an old stone window frame, the city that spread out before me was stunning. Centuries of building styles, shapes, and materials created a mix of powerful images—protruding stone cornices, sloping copper-clad mansard roofs, towering steeples, and gargoyles extending precariously over the streets. In the distance, the newly completed Pompidou Centre’s sculptural frame and colorful mass shimmered in the afternoon sun. Visually colliding and competing, these elements somehow formed a strangely harmonious and well-ordered whole. For an aspiring architect from Kentucky, this amazing scene left an indelible impression. Filled with a good deal of hope, a little bit of knowledge, and a lot of anticipation, I imagined that a bright and alluring future of designing buildings was almost at hand, and the world would be the sphere in which I was to work.

As it turned out, that sphere ended up being not quite as expansive. After returning to Louisville, I discovered that the region I’d observed and thought about since childhood was in many ways every bit as interesting and historically rich—and presented as many opportunities— as most of the places I’d seen in my travels. So this midsized American city, situated on the Ohio River in a lovely valley, would become my creative base.

Surrounded by exceptional clients and a small cadre of friends all deeply interested in the opportunities and beauty that modern architecture offered, I would spend the next forty years living and working in and around this place.

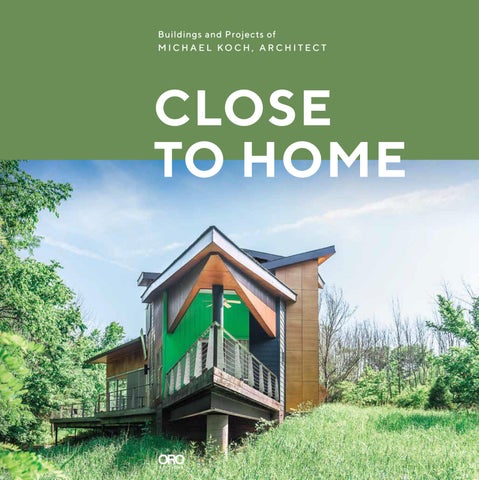

The projects featured in this book, Close to Home, are precisely that, close to home. They are within a 15-mile radius of where Joseph Michael Koch was born, raised, and practiced for almost forty years. The selected work offers insights into ways of incorporating architecture into the landscape and structure of the Ohio River Valley and Louisville. Michael’s practice comprises an accumulation of experiences from early childhood through high school and college, and his lifelong passion for painting and sculpture. His education at the University of Kentucky, during the height of the Dean Anthony Eardley era at the College of Architecture (1975–1980), provided him with a significant set of experiences that merged theory with formal design and vernacular approaches. His professors included Peter Carl, Stephen Deger, Judith DiMaio, Clyde Carpenter, and Herb Greene, who lauded the use of locally available materials such as limestone, hardwoods, concrete, and brick to develop buildings that blended into or actively engaged with Kentucky’s natural undulating terrain. This local experience, coupled with his active participation in the emerging European Study Abroad program under the direction of Chilean architect Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente, enabled Michael to translate Kentucky’s regional idioms into a vibrant modernism that aligned architecture with the poetics of place. His study abroad experience activated the creative potentials of architecture and provided him with a critical vantage point from which to design and build. Regardless of scale or type, whether residential or commercial, Michael sought to design spaces that enabled the client or visitor to experience the “psychological soaring of spirit” that he experienced firsthand in Europe. Site-specific, expressive, inclusive, and inspired are terms that characterize his architecture. This book aspires to capture his creative approach through the representational tools that he has used throughout his career—most notably large-scale abstract painting, collage, modeling, drawing, and building. The publication presents the creative, award-winning achievements of his firm Michael Koch and Associates Architects over the last four decades. The project descriptions, drawings,

and photographs give voice to the simple elegance and meaningful contributions he made and continues to make in and around this beautiful region in the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Background

Joseph Michael Koch (pronounced “cook”) was born in Louisville in 1956 to Louisville natives Joseph Michael Koch Jr. and Sallie O’Bryan Koch. Michael is the eldest of four children. In 1965, Michael’s father founded Koch Filter Corporation, a family-owned business specializing in the production of air filtration products.

Early Influences

Even though downtown Louisville was in decline and negatively impacted by urban renewal during the 1960s, the suburbs exhibited steady growth. Michael developed an interest in the houses, buildings, and environments in his immediate proximity that expressed a new, vibrant, clean-lined, and modern architecture. His childhood home, located a few miles from downtown, stood on a plateau in an area called the Highlands. Bordering Frederick Law Olmsted’s Cherokee Park and developed around the turn of the twentieth century as one of the city’s earliest subdivisions, the Highlands’ broad forested area of rolling hills and creek-lined valleys exemplify the natural beauty and rugged topography that characterize the region. Formed from parcels of several significant estate properties that surrounded Louisville, the Highlands developed in phases over nearly five decades, and includes a rich variety of architectural styles and types. Large Victorian-ornamented mansions from the late 1890s, surrounded by stately brick houses, shotgun cottages, and bungalows, sit harmoniously with multi-family apartments, monumental churches, and informal commercial structures.

The Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine have ministered to residents of Central Kentucky for more than 100 years. To celebrate these good works and to provide an intimate and new worship and gathering space, the Dominican Sisters sought to build a chapel located near the historic motherhouse on their campus.

The chapel’s entry sequence begins with doors framed by a bold and sculptural reminder of the complex world that lies beyond its walls. The entryway consists of fourteen vertical elements that protrude from the earth. The impact of this protrusion creates an external, mazelike sculpture above which sits a triangular-shaped roof. A bold, angled wall which rises from the ground to frame the interior spaces on the opposite side of this figural feature culminates in a carillon and glass spire.

A defining wall with a “community window” frames the simple altar space below. Perpendicular to this wall is the subtle “world window” wall composed of translucent panels.

A “solitary window” containing a small reflective glass frame encloses the chapel space and baptistery alcove. This element faces the motherhouse and the historic parts of the campus, while three pairs of doors cut from Kentucky hardwood open from the chapel onto the garden along the angled entry façade.

The goal of the project was to create an environment similar to the vibrant artistic communities of Providence, Savannah, and Baltimore, where student artists, professors, and designers collaborate to form a stimulating and exciting urban educational experience.

The campus sits along Louisville’s historic urban north-south axis. Following the city’s 200-year growth pattern, the corridor contains major landmarks and historic districts including Main Street, Downtown Louisville, Broadway, the Public Library, Spalding University, Old Louisville, the University of Louisville, and Churchill Downs, culminating at Iroquois Park.

The campus plan replaces an uninspiring green space and asphalt-covered parking lots with a great lawn that spans from 3rd Street to 4th Street. Beneath this lawn is a 240-space parking garage shared by the neighborhood anchor, Memorial Auditorium, several historic churches, Simmons College, and Spalding University.

The first phase of the project includes a 40,000 sq. ft., four-story building orienting east-west. It rises over an existing city alley, providing a backdrop to a proposed great lawn. A central pedestrian street bisects the center of the block and incorporates the rear of the buildings that front 3rd Street and 4th Street, creating a series of private urban assembly and performance spaces.