Preface Jean-Louis Cohen

Introduction Arthur Rüegg

From Grade School to early career

Childhood

École de l’Union centrale des arts décoratifs

Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925

Early Career, 1926

metal: a revolution in Furniture deSiGn

Le Bar sous le toit, 1927

The Saint-Sulpice Dining Room, the Unité de choc Travail et Sport, 1927

PartnerShiP with le corbuSier and Pierre Jeanneret For Furniture and home FurniShinGS

Meeting Le Corbusier

The Mobilier nouveau Program, 1928

The Chaise longue basculante, 1928

The Fauteuil dossier basculant, 1928

The Fauteuil grand confort, 1928 Tables, 1928

Production of New Tubular Metal Furniture, 1928

Research on Extendable Tables and Folding, Swiveling, Swinging Chairs

Picture Gallery at the Villa La Roche, 1928

Interior Design of the Villa Church, 1928

Interior Design of the Villa Savoye, 1928–31

Maisons Loucheur, 1928–29

La Cellule de 14 mètres carrés par habitant, 1929–30

Wood or Metal?

Standard Storage Cabinets, 1929

Un équipement intérieur d’une habitation, 1929

Furniture Lines

L’Union des artistes modernes

A Few Private Commissions

“Mimi Pinson” in Montparnasse, 1932

The First Building, an Air Terminal, 1930

Villa Martínez de Hoz, 1930 Venesta, 1930

Thumbing Noses at the German Avant-Garde, 1931

The Cité du refuge, Salvation Army Headquarters, Paris, 1929–33

Dwellings for the Ferme radieuse

Houses with Brise-Soleil for Barcelona, 1933

Pavillon suisse at the Cité universitaire, 1931–33

The rue Nungesser-et-Coli Building in Paris, 1931–34

Bat’a Project, 1936

PhotoGraPhy

A Contemporary Tool

L’Art brut, 1933

A Universe of Forms

the militant yearS

Hope for a New World

The Athens Charter, 1933

Return to Moscow, 1934

Developing a Taste for Our Work among the People

CIAM-France

Preparation for the Exposition internationale de Paris, 1937

Vernacular Architecture, or the Genius of the People

PreFabricated leiSure architecture

La Maison au bord de l’eau, 1934

Vacation Resort in Bandol, 1935

L’Hôtel de haute montagne, 1935

High-Altitude Refuge Chalet, 1936–37

Bivouac Refuge, 1936–37

The Tritrianon, 1937

Mountain Chalet Hotel, 1937–38

The Tonneau Refuge, 1938

Singular Architecture

Public exhibitionS and Social enGaGement

La Maison du jeune homme, 1935

Imperative of Reality-Based Work

Practical Advice on Furnishing a Dwelling, 1936

An Affordable Living Room for the Masses, 1936

La Grande Misère de Paris, 1936

Waiting Room of the Minister of Agriculture, 1936

The CIAM, the Pavillon des Temps nouveaux, Rupture, 1937

At the UAM Pavilion, 1937

The Ministry of Agriculture Pavilion, 1937

aFter the break with the rue de SèvreS Studio

Joy of Man’s Desiring

Analysis of Urban Chaos, Can Our Cities Survive?

Office Project for the Minister of National Education, 1937

Free-Form Furniture, 1938–39

Saint-Nicolas-de-Véroce, Flight to the Mountains, 1938

A Mountain Hideaway, 1939

A Hotel in Méribel, 1939

A Village House for her Mother, 1939

Military Housing and Emergency Shelters, 1939

The Flying Schools, 1939

Buildings for the SCAL in Issoire, 1939–40

Departure for the End of the World, 1940

Preface

Jean-Louis Cohen

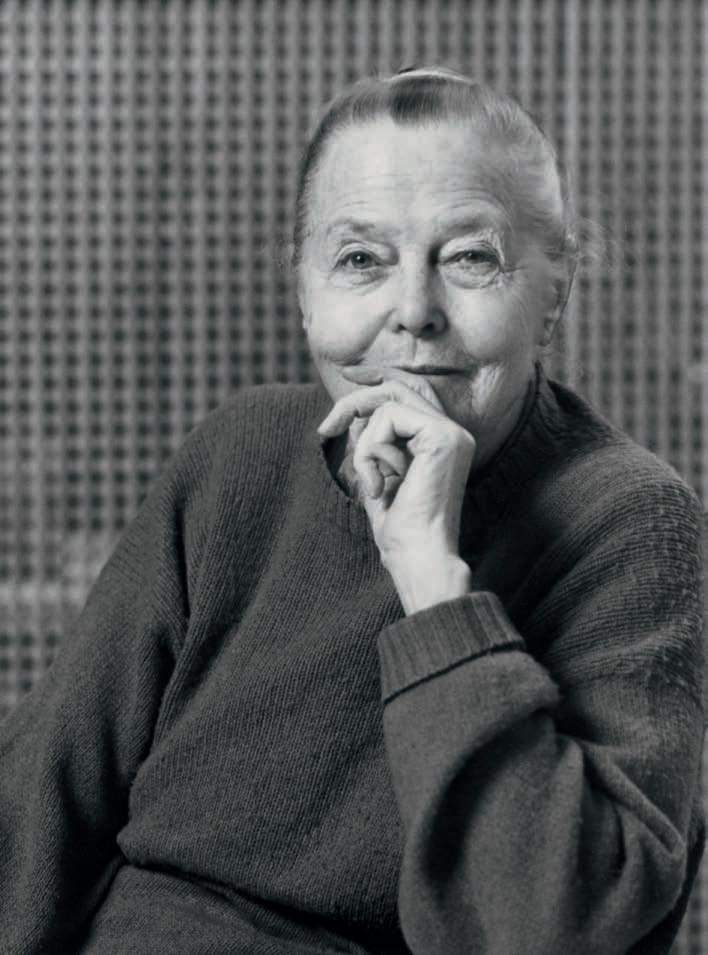

Opposite Charlotte Perriand in her studio, circa 1995. Photograph Gaston/AChP.

For seven decades, Charlotte Perriand shaped the world through her inventions, leaving in her wake an array of images, objects, places, and buildings, all registers of an oeuvre that now appears in all its fullness. Few comprehensive analyses of the ensemble were conducted during her lifetime, as the meticulously preserved traces of her work were kept in her Parisian studio on rue Les Cases where they continuously provided the framework for her research. The survey of her archives undertaken by Jacques Barsac over a span of many years has enabled not only the clarification of a number of points that remained obscure, but, as witnessed in the following pages, the restructuring of facets of her production long ignored by historians, such as her intense work as a photographer during the 1930s, which Barsac exhibited, first in Zurich in 2010, and then in Paris. The trajectory of her international travels has also been reconstructed in all its complexity, including her discovery of Japanese culture between 1940 and 1942 that would enrich her own work, as seen in the presentations made in Japan in 2011–12 and Saint-Etienne in 2013.

More concerned with action than with remembrance and—a fortiori—commemoration, Perriand found time to publish a memoir in 1998 that remains a document as moving as it is informative. Yet she herself never undertook the systematic publication of her own work, as did her associates and friends Le Corbusier and Jeanneret from 1930 on. Thus knowledge of her projects and production has remained discontinuous, like an ancient mosaic where substantial portions have been lost. Certain patterns became discolored or rendered illegible by the absence of fragments that were essential to an understanding of the whole. The lucid accounts by Arthur Rüegg extend research conducted on both sides of the Atlantic and enable the evaluation of this significant body of work, enhancing the indispensable interpretations put forward over the past twenty years. Far from contradicting Rüegg’s accounts, the three volumes of Charlotte Perriand: Complete Works, conceived and written by Jacques Barsac, reinsert them into a grand narrative, where landscapes, people, and objects interact in a continuous ballet. While impossible to isolate one from another, the components of this chronicle extending over three quarters of a century may still be considered in and of themselves.

Distant Scenes

Perriand’s trajectory was neither linear nor premeditated. She proceeded by leaps and bounds, through encounters with leading figures and experiences of challenging situations. These events led her from one stage to another, while creating a feedback loop of places and themes that inspired her. Each scene wherein she acted as both protagonist and observer can be characterized by a specific configuration of the arts, technology, and lifestyle, the backdrops against which she evolved and that she herself transformed. Paris proved the most enduring of these, the city where she grew up, matured, and also caused provocation with her first interior designs. Between the Exposition des arts décoratifs of 1925 and the Exposition internationale of 1937 she constructed an approach attentive to the field of technology, to bicycles and front-wheel drive cars by Citroën, and to airplanes whose tubular elements and metal skins she would use to her own ends. From her Bar sous le toit (Bar under the Roof) to her mountain shelters, she offered a radical interpretation of French industrial modernity. At the same time, Paris was also a political arena where Perriand encountered the forces of the Left during the Popular Front, responding to some of their needs for projects and propaganda.

Regarding the rest of Europe, Perriand had little to do with Germany other than participating in the Internationale Raumausstellung of 1931 in Cologne, where, just this once, she acted in complete complicity with Le Corbusier in opposing functionalist puritanism with a colorful, figurative carpet. On the other hand, she shared her generation’s fascination with the experiments of the young Soviet Union, where she saw herself moving one day, as several Germans and Swiss architects had done in 1930. They were joined by former employees of

Charlotte Perriand

View of the bar–kitchen which opens on the work space and the exercise space by a sliding panel. Axonometric projection published in Répertoire du goût moderne II, fig. 21, 1929. AChP.

Phonograph cabinet, typewriter table and seat, bed with metal tubing, tubing and canvas stool, Tabouret pivotant (swivel stool). Published in Répertoire du goût moderne II, fig. 22, 1929. AChP.

in full swing, Renato De Fusco laid the groundwork for a scholarly analysis of the furniture; Le Corbusier Designer: I mobili del 1929 (Milan: Casabella, 1976), Maurizio Di Puolo, Marcello Fagiolo, and Maria Luisa Madonna in their “La machine à s’asseoir”: (Rome: De Luca Editore, 1976) became the first scholars to acknowledge the crucial role played by Perriand. Since 2004, Cassina has been issuing a steadily growing collection of furniture designed by Perriand alone.

During her own lifetime, Perriand had thrown open a window upon her intellectual and material world by staging the impressive 1985 retrospective at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and accompanying it with what she called an “annotated biography”—a collage put together Charlotte Perriand—Un Art de vivre, Paris: Flammarion, 1985). It was in the context of this exhibition that Jacques Barsac saw through to completion what has remained to this day an indispensable video portrait of the Charlotte Perriand: créer l’habitat au XXe siècle (1985). The scenography of Perriand’s three last exhibitions in London (1996), Tokyo (1997), and Biot (1999) was also the work of the artist herself. Upon her death, the first task of her heirs was to sift through and take stock of the wealth of documents stored in the cave. Barsac was able to draw extensively on these new materials for his monograph of 2005, which covered Perriand’s life and work up to 1959. Such a wealth of material also whetted the appetite for inquiry into fields that had hitherto received but scant attention, such as Perriand’s early ties to the Alpine Charlotte Perriand—Carnet de montagne, textes et images choisis par Roger Aujame et Pernette Perriand, Albertville: Éditions Maison des Jeux olympiques d’hiver, 2007). The following year saw the publication of Barsac’s second volume, Charlotte Perriand et le Japon (Paris: Éditions Norma, 2008), which casts Perriand as an enthusiastic proselytizer in the cause of modern architecture in the Far East, and studies the enduring influence of Japanese culture on her work. The third eye-opener delivered by Barsac was contained in his wonderful Charlotte Perriand and Photography: A Wide-Angle Eye (Milan: 5 Continents Éditions, 2011), which appraises the poetry of her Art brut—an art practice she shared with both Jeanneret and Fernand Léger—from a hitherto unexplored angle, portraying Perriand as a socially engaged woman and activist. These milestones of Perriand scholarship were accompanied by three major exhibitions: in Paris (The Complete Works, 2005); in Zurich, Paris, and Chalon-sur-Saône (Photography/Collages, 2010–11); and in Saint-Étienne Métropole (Japan, 2013).

The name Charlotte Perriand has since become a grande signature. Her works regularly fetch record prices on the international art market, and scholars today take just as much interest in the ramifications of her own work as they do in the relationships that shaped her biography. But who was Perriand really? The question now seems more topical than ever before. And it was this that motivated Jacques Barsac to descend once again into the cave, to marshal all the research done hitherto, and to embark on the monumental project of a “definitive” three-volume monograph.

“Brightness, Loyalty, Liberty”: New Furniture for a New World

Charlotte Perriand’s venture into the world of les arts décoratifs was blessed with good luck right from the start. Her teachers Henri Rapin and in particular Maurice Dufrêne, head of the studio La Maîtrise and cofounder of the Société des artistes décorateurs, attracted everyone who was anyone in the world of French furniture design around 1925, and they supported their exceptionally gifted pupil to the best of their abilities. Henri Clouzot, director of the Musée Galliera, can be credited with having engendered in Perriand a distaste for the imitation of old styles and a sure feel for the values of the new age then perceived to be dawning. Given how deeply immersed Perriand was in the world of her masters, it is little wonder that she barely

Travail et Sport, 1927.

noticed either the Russian pavilion designed by Konstantin Melnikoff, nor Le Corbusier’s and Jeanneret’s Pavillon de L’Esprit nouveau at the groundbreaking Exposition des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes of 1925.

The idiom conveyed at the show was demonstratively “modern” and unmistakably indebted to avant-garde art, which had brought with it a completely new style. This is all the more astonishing given that for all their interest in the applied arts, the Cubists, Orphists, and Futurists had hitherto been perceived primarily as eccentrics who threatened to destabilize the cozy world of the bourgeoisie. Almost all the wall-mounted décor and furniture exhibited in 1925, all the bric-à-brac and book bindings, and even the glazing, to say nothing of several other architectural elements, were endowed with a rigorously geometrical design. “The caprice hides in the geometry,” as Léon Werth remarked. Perriand’s experimental Bar sous le toit continued to manifest stylized, slightly Art Deco profiles even as late as 1927. Yet notwithstanding the new motifs, precious metals, colored leather, exotic woods, and even tortoiseshell and sharkskin were still considered de rigueur raw materials for finely crafted furniture. Like French haute couture, the new style was addressed at a rich, cultured elite—a class of sophisticates anxious to carry over into the modern age the ritualized gestures that can ultimately be traced back to the ceremonial formality of life at court.

The fact is that, since the eighteenth century, it had indeed been France that had supplied the most enduring solutions for the interior, seen as something that fused architecture and interior design into a unified whole—even to the point of providing names for all the most prominent styles. In the France of the 1920s, even the most progressive ensembliers continued to approach the interior as a luxurious Gesamtkunstwerk, while out of the European avant-garde only the Dutch De Stijl movement insisted on combining interior space and furniture to form a coherently styled whole, as exemplified by Gerrit Rietveld’s 1924 Schröder House in Utrecht. The forward-looking interiors designed by adherents of Neues Bauen (New Building), by contrast, were remarkable for their programmatic separation of interior space and contents, their eradication of all things superfluous, and their use of type furniture. Objects in various shapes and styles could form a “whole” only to the extent that they could be understood as expressing the same position or ideology—as in the case of Hannes Meyer’s Co-op interior of 1926, which can be read as the very antithesis of the homogeneous interior.

What Charlotte Perriand found in Le Corbusier in 1927 was the escape route she had instinctively been seeking—a chance to venture beyond Art Deco with its interiors premised on effect rather than on the things themselves. As an avant-garde figurehead, Le Corbusier even made use of anonymous makes of furniture, albeit without ever relinquishing control over their formal cohesion. He defined the aesthetic rules which relentlessly governed the selection, development, and arrangement of his objets-types, according to principles that he himself had put to the test in Purist painting. This was a framework within which Perriand could give free rein to her talents. While certain combinations of materials and colors in the new metal furniture that she developed together with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret are redolent of her past in Parisian applied arts, she seems to have made the leap effortlessly from a domestic ideal anchored in the decorative to one anchored in the functional and the rational. Her youthful enthusiasm was fired by the notion of the physically and mentally fit “Man of the XXth Century” as the prospective occupant of her 1929 studio apartment, full of glossy, gleaming, reflective surfaces and noiselessly adaptable fittings and furnishings. Unveiled at the Salon d’automne, it was at once both a spectacular celebration of glass and metal as the materials of the future and an allegory of the ominous “machine à habiter.” As the principle underpinning this manifesto-like luxury apartment, however, Taylorist

Charlotte Perriand Le Bar sous le toit, 1927.

Perspective rendering of the project designed for the place Saint-Sulpice apartment–studio. Published in Intérieurs, fig. 40, 1929. AChP.

Salle à manger 28 (Dining room 28).

Perspective drawing of the project designed for the studio–apartment, place Saint-Sulpice, 1927. Published in Intérieurs, fig. 40, 1929. AChP.

Fauteuil pivotant (Swivel armchair), 1927. Execution Plan, 1928. India ink on vellum. AChP 27 001.

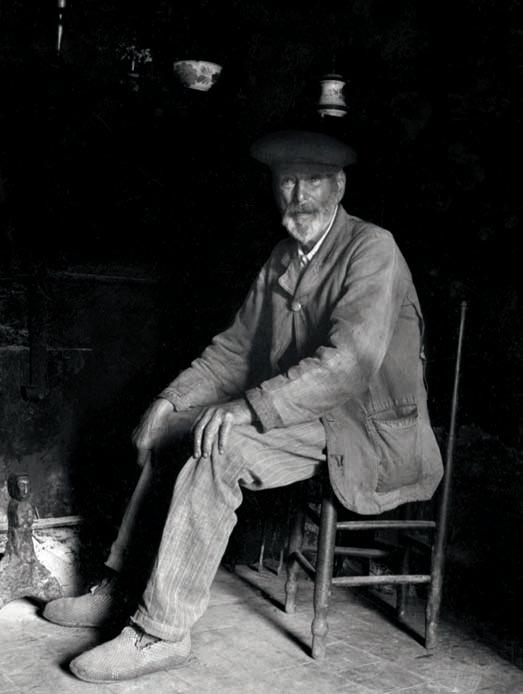

Childhood

Charlotte Perriand, the only child of a Savoyard father and a mother from Burgundy, was born in Paris in 1903. Unhealthy living conditions and poor hygiene were common at the time in the capital, and the trades practiced by her parents prompted them to send her to Moulery, the village in Burgundy where her mother was born, to live with a great-uncle, a farmer whom Charlotte called “papa Desmoulin.” She spent the first three years of her life there showered with affection and enjoying great freedom. “I was enveloped in nature’s embrace, in tune with the seasons, stretching out to the stars. It sparked a feeling of respect for all country folk around the world, people whose roots were strongly grounded in the earth,” she later wrote.1 She would retain from this experience the visceral link with nature and farming which she went on to glorify in 1936 during the period of the Front Populaire. Here she learned about simplicity, authenticity, and economic efficiency: a farmer’s common sense, otherwise known as pragmatism. In 1906, she returned to Paris to live with her parents, on the place du Marché-Saint-Honoré, where she grew up in a neighborhood surrounded by craftsmen and women working in luxury industries. Her father, Charles Perriand, the son of a blacksmith and the last born of eleven sons, left home at a very early age for Paris, where he became a tailor. He was employed by Cumberland, the prestigious English couture house on the rue Scribe, and would participate in the International Exhibition of Barcelona in 1929.2 Her mother, Victorine Perriand, a vest-maker, was the daughter of one of Ferdinand Barbedienne’s metalworkers whose hour of glory had come when he traveled with the Statue of Liberty to New York. She had her own workshop where she employed five or six seamstresses who made striking vests for the couture houses. She was a woman of conviction, in the revolutionary tradition of the Paris suburbs. In the manner of many French people, during the Great War she gave all her savings to the state and strenuously economized to defend her homeland. A hard-working yet beautiful, precise, generous, and effervescent woman, she loved dancing on Sundays and at carnivals and cafés. She repeated to her daughter every morning the refrain, “Charlotte, get up,” and every evening, “Charlotte, work. Work is freedom.” In the aftermath of World War I, work was the only possible way for women to gain their independence and take charge of their own destiny. Victorine Perriand dreamed of running an antiques shop. With her taste for heavily ornate furniture and secondhand stores, she was always bringing home knick-knacks and decorative sculptures, cluttering up the family apartment with a random selection of varied objects. To the great satisfaction of Charlotte and her father, who would have been perfectly happy with just a simple table in pine,3 “fortunately, there was a cat that was always knocking things over and breaking them.”4 She never managed to fulfill her dream nor pass beyond the stage of a Sunday flea market bargain-hunter.

Charlotte Perriand lived in a world where moral uprightness and a sense of duty and solidarity were bedrock values. Her parents instilled in her a love for beautiful craftsmanship, a strict insistence on the quality and flawless workmanship that defined Parisian luxury houses, and the pleasure of working with talented craftsmen and women.

As a child, she marveled at the red trucks in the fire station located just below her parents’ window, and at the firemen who practiced gymnastics and high-flying acrobatic routines on their tall ladders, “seeming to defy all notions of gravity. I arranged things so I would become a sort of distraction for them, slipping out of the house and cajoling them to let me clamber on top of their magnificent red machines trimmed in polished, gleaming copper.”5 “I would go over to the station and play with them and they trained me in gymnastics.”6

Preceding double page

Charlotte Perriand in 1904 and circa 1906. DR/AChP.

Charlotte Perriand Study of landscape, circa 1922. Gouache on board. AChP.

Charles Perriand, Charlotte’s father. Photograph Charlotte Perriand/AChP.

Victorine Perriand, Charlotte’s mother. DR/AChP.

“Papa Desmoulin,” Charlotte’s great-uncle. Photograph Charlotte Perriand/AChP.

Fabric designs, 1922–23. Gouache and pencil on Canson paper. AChP.

Opposite Two tile studies, circa 1922. Gouache and ink on Canson paper. AChP.

Charlotte Perriand Works for the École de l’Union centrale des arts décoratifs.

Le Bar sous le toit, 1927

On December 22, 1926, Charlotte Perriand married Percy Scholefield, against the advice of her father and to the great surprise of her friends due to the difference in age and mindsets.39 The young, athletic, audacious, effervescent woman chose a mature and reassuring bourgeois man; “at the time marriage was the only way for the chrysalis that I was to turn into a butterfly, and a butterfly is a creature that takes flight.”40

While apartment hunting, she decided to cross the Seine to mark her emancipation, renting a former photography studio at the corner of place Saint-Sulpice with a magnificent view of the church, the square, and the rooftops of Paris. “I set about converting it, feeling freed from the constraints of my artistic education, probably because this time I was creating something for myself.”41 She found this freedom expressed in the street: “I would wander down the avenue des Champs-Élysées to watch all the expensive cars go by with their gleaming bodywork. I soaked up their technical qualities at the Paris automobile show.”42 The universe of chrome-plated

Le

toit

Perspective rendering of the project designed for the place Saint-Sulpice apartment–studio. Published in Intérieurs, fig. 40, 1929. AChP.

Right and opposite

Le Bar sous le toit, presented at the Salon d’automne, 1927. Banquette, card table, phonograph cabinet, bar, cascade lamps, Tabourets de bar (bar stools) in nickel-plated copper. Stool with cross-shaped base, chrome-plated copper and leather.

Photographs Rep/AChP.

Preceding double page Salle à manger 28 (Dining Room 28), exhibited at the Salon des artistes décorateurs, 1928.

Photograph Rep/AChP.

Charlotte Perriand

Bar sous le

(Bar under the Roof), 1927.

metal, the bright and shiny fire trucks and the size of the pared-down hospital room of her childhood “came back to the surface at that very moment,” she would later recall.43 Her approach consisted of “applying to furniture the same techniques utilized in the fabrication of the bodies of cars”: welding, folding sheet metal, curved tubes, mechanics, and metal fastenings.44 These were techniques rarely used in France in the business of furniture making, and their vast palette allowed her broad formal and constructive freedom. To mark her break with tradition from the outset, she replaced the door to her apartment with a sliding one in lacquer. In the entry hall, Charlotte Perriand designed her “equipped wall,” a piece of built-in furniture serving as a storage cabinet and forming a wall separating the entry and the bar, which was completely integrated into the architecture. It was composed of three superimposed compartments with sliding doors, regularly spaced, with three niches designed for displaying objects. These were lit from the sides by three recessed light boxes hidden in the large vertical support.

Charlotte Perriand, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret Chaise longue basculante, version 1, 1928. DR/AChP.

Balancelle and base of the Chaise longue basculante, 1928. DR/AChP.

Charlotte Perriand on the Chaise longue basculante, 1928. DR/AChP.

Chaise longue basculante, version 2, 1928. Version corresponding to the patent. DR/AChP.

Opposite

Charlotte Perriand

Production plans for the Chaise longue basculante, 1928.

Balancelle base, pied balancelle 2 with ovoid tubing, 1928, and chaise longue base with lentoid tubing and “olive” end pieces, 1930. Ink on tracing paper.

AChP 28 008, 28 007, 28 006.

Charlotte Perriand, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret

Patent drawing for the invention of the sliding system for the Chaise longue basculante, n. 672.824, requested on April 8, 1929 under the names “Mme Scholefield, née Perriand, MM. Jeanneret (C.-E.), dit Le Corbusier and Jeanneret (A.-P.).”

Printed on paper.

AChP 28 025.

onto the music room. There, an entire wall was taken up by four rows of stacked metal cabinets, similar to the prototypes presented at the Salon d’automne of 1929 but with a different design in terms of fabrication. Learning her lesson from early examples, Perriand attempted to improve on them. The sides were load-bearing, and their exposed edges were lacquered in color to give the wall a square framework, emphasized by solid color sliding doors in Plymax. 208 The second row from the bottom was equipped with clear glass doors, revealing the back of the interior which was painted in bright colors, thus organizing the wall horizontally and visually enlarging the room. Retractable shelves hidden in the horizontal supports could be pulled out to display objects or serve as desks or lecturns. A discreet light fixture composed of narrow-diameter metal tubing with a slot designed to light the shelf and the interior of the cabinet was affixed on the supports. This was the first genuine application of the metal storage cabinets in a dwelling, and also the last. For this apartment, Perriand created a new juxtaposable armchair model that could be assembled to form a banquette. The painted tubing structure was a single piece; the seat cushion was affixed to frame with corner pieces while the back cushion rested freely against the back of the frame. In the kitchen, she installed the new model of her Table extensible , which now had a crank handle for enlarging the tabletop, which was covered in pink rubber. This was probably the same piece that was shown at the first exhibition of the UAM.

In the early 1930s, Charlotte Perriand completed a few modest personal commissions— the interior design of the Gutmann, Morvan, and Baumann apartments, for which only oral descriptions remain of the furniture used, but no images, apart from rare photographs of the apartment of Paul and Ange Gutmann, with whom she maintained a long-lasting friendship.

Sliding door mounted on a rail, tinted glass panel.

Fauteuils juxtaposables (juxtaposable armchairs) made of metal tubing, can be assembled to form a banquette, 1930.

Charlotte Perriand Jean Rivier’s apartment in Paris, 1930–32. Photographs Pernette Perriand-Barsac/AChP.

Charlotte Perriand Jean Rivier’s music room in Paris, 1930–32. Photographs Pernette Perriand-Barsac/AChP.

Storage wall unit designed according to the Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perriand principle of juxtaposable and stackable metal storage cabinets. The storage cabinets are closed with sliding panels made of Plymax (rust-free aluminum with a matte satin finish), runners in chrome-plated copper. Cabinets intended to hold books and collections of objects are lacquered in beige, red, and gray, with plate-glass panels.

note illustrated by these photographs and a statement outlining the general characteristics. Three versions with different diameters were envisioned: one for ten climbers on two levels, and two others for thirty or thirty-eight climbers on three levels. Building materials included steel, aluminum, Duralumin, fiberglass, hardboard, tarpaper, and wood. The components did not exceed forty kilos and 1.05 by 2.1 meters, so that they could be easily carried. It would have taken six people three days to assemble.

Transported by their futuristic enthusiasm, Jeanneret and Perriand designed a shelter for gliders near the refuge, intended for their engineer friend, André Tournon, who hated long walks in order to reach great heights. The name Tonneau (barrel) is derived from its shape. Space capsules did not exist at the time, and it is regrettable that Hergé never saw this project: Tintin would probably have sought refuge there while in the Himalayas with Captain Haddock and Professor Tournesol, under the watchful eyes of yetis looking in the portholes.

Although the Tonneau Refuge would remain at the model stage because of the war, there have been natural descendents: the Concordia Station was built on a similar principle at the South Pole in 2002, with the same architectural form but with contemporary techniques and materials, by architects who did not know Perriand and Jeanneret’s project, but who came to the same conclusions.

Seventy years after its creation, the association ACTE built the first copy of the Tonneau Refuge in Thônes, based on period plans.368 In 2011 the firm Cassina realized a second copy, complete with the original interior design, including furniture provided in the drawings.369 As in the case of the Maison au bord de l’eau (1934), the manufacture of the Tonneau Refuge demonstrates the correctness of Perriand and Jeanneret’s approach, offering the comforts of a shelter in a cozy space where one can look out the windows and dream.

Charlotte Perriand, Pierre Jeanneret Tonneau refuge, 1938.

Photographs Charlotte Perriand/AChP.

Model showing the different stages of assembly, 1938.

Opposite Children’s carousel in Croatia, 1937. Source of inspiration for the construction of the Tonneau refuge.

Photograph Charlotte Perriand/AChP.

Description sheet of the three refuge models with diagrams for the arrangement of bunk beds for ten, thirty, and thirty-eight people, 1938. Ink on board. AChP.

The publication of this book was generously supported by Cassina S.p.A., Meda

Dust jacket

Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand LC4 CP (1928), 2014. Cassina edition

Limited edition in collaboration with Louis Vuitton

Photograph Cassina Archive

Coordination: Mandana Mortazavi

Translated from the French by Genevieve Hendricks, Juan Martin, Eileen Powis, Gammon Sharpley, Andromède Tait

Translated from the German by Bronwen Saunders (Arthur Rüegg’s text)

Copyediting: Siobhán Fitzgerald, Joe Nankivell, Ben Young

Consultants: Genevieve Hendricks and Bronwen Saunders

Design and typesetting: Delphine Renon

Lithographs: Les artisans du Regard, Paris Printing and binding: Musumeci, S.p.A., Italy

© 2014 Archives Charlotte Perriand, Paris, and Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess AG, Zurich © Original French edition published by Éditions Norma, 149 rue de Rennes, 75006 Paris, France www.editions-norma.com

For all works by Charlotte Perriand: © Archives Charlotte Perriand, Paris / 2014, ProLitteris, Zurich / Adagp

For all works by Le Corbusier: © FLC / 2014, ProLitteris, Zurich / Adagp

For all works by Pierre Jeanneret: © Jacqueline Jeanneret, Geneva / 2014, ProLitteris, Zurich / Adagp

For all works by André Arbus, André Bauchant, Fernand Léger, André Masson, Jean Prouvé, Jean Puiforcat: © 2014, ProLitteris, Zurich / Adagp

For all works by Pablo Picasso: © 2014, ProLitteris, Zurich

Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess AG

Niederdorfstrasse 54

CH-8001 Zurich

Switzerland

ISBN 978-3-85881-746-4

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publishers.

www.scheidegger-spiess.ch