Canova’s Gypsotheca

Carlo Scarpa 1955–1957

Chronology of Carlo Scarpa’s main works

Museo Correr, Venice, 1952–53 and 1957–60

Musée Correr, Venise, 1952-53 et 1957-60

Musée Palazzo Abatellis, Palerme, 1953-54

Museo di Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, 1953–54

Pav illon du Venezuela, Venise, 1953-56

Venezuela Pavilion, Venice, 1953–56

Canova’s Gypsotheca, Possagno, 1955–57

Musée Canova, Possagno, 1955-57

Villa Veritti, Udine, 1955–61

Villa Veritti, Udine, 1955-61

Olivetti Showroom, Piazza San Marco, Venice, 1957–58

Oliv etti showroom, Place San Marco, Venise, 1957-58

Musée Castelvecchio, Vérone, 1957-64 et 1966-67 et 1973-75

Castelvecchio Museum, Verona, 1957–64 and 1966–67 and 1973–75

Gavina Showroom, Bologna, 1961–63

Gavina showroom, Bologne, 1961-63

Querini Stampalia Foundation, Venice 1961–63

Fondation Querini-Stampalia, Venise 1961-63

Zentner House, Zurich, 1964–68

Maison Zentner, Zurich, 1964-68

Mausolée de la famille Brion, San Vito d'Altivole, 1969-78

Brion Cemetery, San Vito d’Altivole, 1969–78

Apartment block, Contrà del Quartiere, Vicenza, 1975–78

Immeuble de logements-Contra del quartiere-Vincence 1975-78

Banca Popolare di Verona, Verona, 1973–78

Banque populaire, Vérone, 1973-78

Villa Ottolenghi, Bardolino, Verona, 1974–78

Villa Ottolenghi, Bardolino, Vérone, 1974-78

Canova’s Gypsotheca

Carlo Scarpa 1955–1957

This project is one of the first museum buildings designed by Carlo Scarpa.

It follows on from the Palazzo Abatellis Museum in Palermo.

It should be noted that the Venezuelan pavilion was underway in Venice at the time. Certain connections can be observed, especially in the shape of the upper windows.

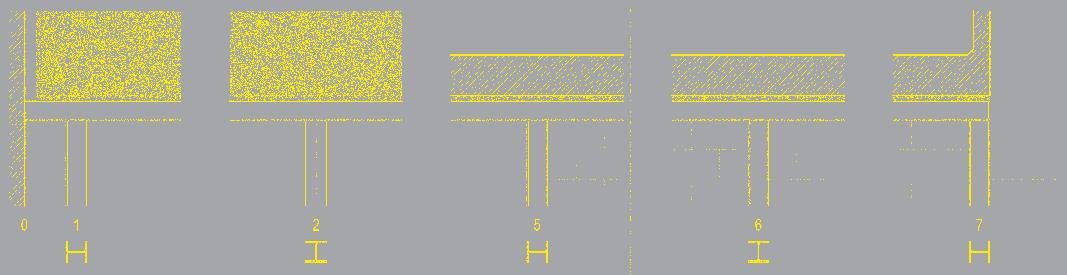

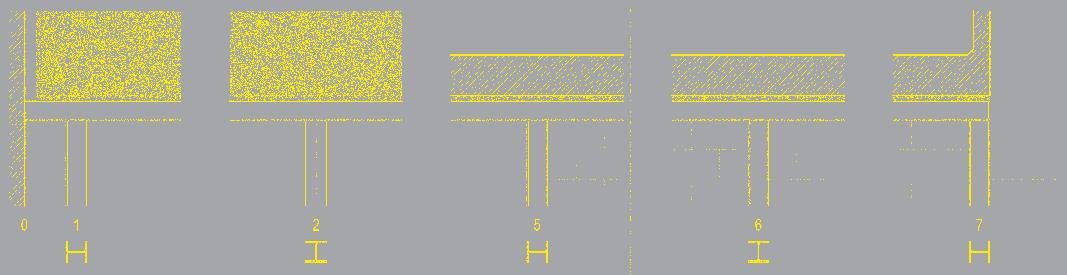

Columns 1 and 2 – Columns 3 and 4

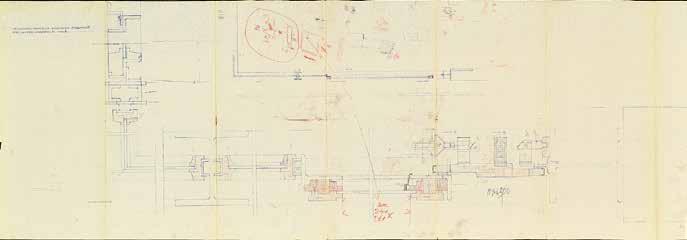

17. Elevation / plan for columns 1 and 2.

18. Elevation / plan for columns 1 and 2.

19. Column 4 incorporates the external joinery. The joinery work runs between columns 4 and 5.

Structural expression

Column 1

This is where the line begins. It approaches the existing wall (the wall of the preserved ‘tettoia’, the canopy) by means of a cantilever, so as not to lean on it. Similarly, the supported wall does not touch the existing preserved wall and a vertical void acts as a concrete-stone joint and thus shows that the wall is not a concrete beam and that it is indeed ‘supported’ and not ‘load-bearing’.

The column is welded under the beam directly without a plate. This assembly is a (non-perfect) fitting of the column to the beam.

Column 2

It is turned to allow the beam to pass through. It is recessed so that column 1 meets column 3, thus visually widening the frame of the void.

The post is welded under the beam directly without a plate. This assembly cannot be considered as an embedding of the column in the beam.

Column 2 is neutralised when scanning the trajectory of the beam cavity (ill. 17).

Column 3

It is turned in the direction of the beam. It marks the halfway point of the empty or glazed part of the portico. Together with column 1, it forms a frame towards the wall of the basilica, on which the bas-reliefs are arranged.

The post is welded under the beam directly without a plate. This assembly means that the column is embedded in the beam.

Formally, the lines of the profile flanges correspond to each other (ill. 18).

Column 4

It is turned to fit with the joinery, which is fixed on either side in the hollow of the profile. The flange of the column makes the vertical part of the wooden joinery disappear. As in the case of column 2, this assembly cannot be considered as the column being embedded in the beam.

Formally, the column recedes and offers its hollow joints to the wooden frames of the exterior joinery (ill. 19–20).

20. Drawing of the exterior wood and steel joinery incorporated into the structure.

1

High floor structure

The high floor of the ground floor, initially made of 80cm-thick wood, was demolished to lower the floor of the first floor so that the natural lighting could come in higher up in relation to the works of art and so that the light would be more diffused.

The reconstruction of the high floors on the lower level of the Museum was the subject of precise composition and design.

The room is roughly square,1 so there is no preferred direction for the span of the floors. Carlo Scarpa chose to arrange the installation of a steel beam in the axis of the tour, while balancing the ceiling by dividing it into four equal parts.

This made it possible to reduce the thickness of the floor and avoid losing ceiling height at the lower level. (ill. 37–38).

The rooms are in fact slightly trapezoid. The design of the floor is then detached from the walls by a stone edge, to create a rigorous geometry that gives rhythm to the tour.

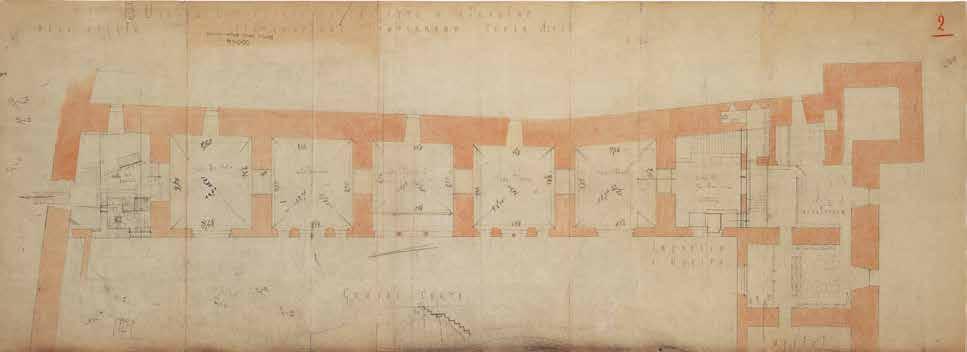

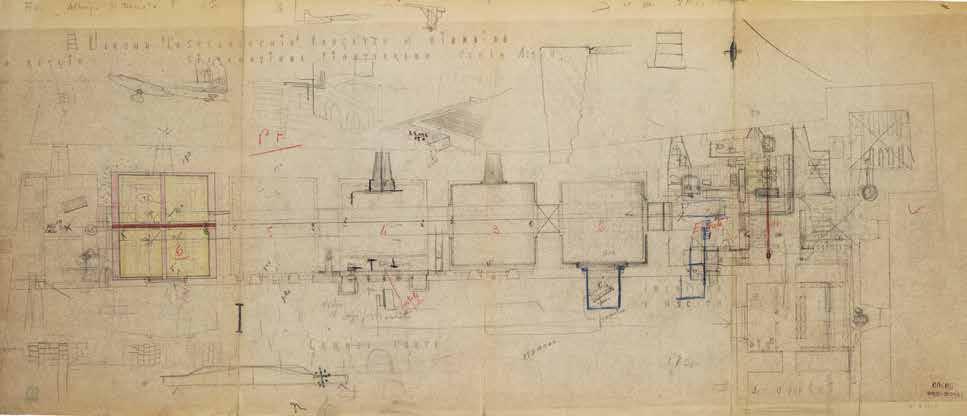

37. Initial survey.

38. Project scheduling.

Implementation

The existing floors were demolished. The concrete support was set into the brick wall. The steel beam was erected in situ, in three parts, in the first phase.

In the second phase, the concrete beams were formworked and poured in situ at the same time as the floors.

The floors are made of terracotta hollow-core slabs, between which reinforcements are placed before the concrete is poured on top to form a lightweight floor using very little concrete (ill. 55–57).

Message of the structure

The imaginary column

The steel beam literally picks up the concrete beams, replacing an imaginary missing column. This substitutes a simpler structure consisting of a single beam and joisting. The whole structure would have been thicker, but also much more visually static.

Engineer Carlo Maschietto had calculated the height of the concrete beams at 80 cm.

Carlo Scarpa thought this was too much, so he joked back: ‘Why don’t you put a post in the middle of each room?’

Carlo Scarpa implemented a modification to the structure of an

existing floor, even though everything had been rebuilt from scratch. The formworked concrete beams can be seen as the petrification of the wooden construction.4

The succession of rooms, all based on the same structural principle, helps to guide the visitor and, above all, unifies all the rooms in an apparently ‘free’ layout, via the ceiling.

Re-establishing an architectonic order

To ‘re-establish an architectonic order’,5 the design of the high floor structure is a key element, especially if it is the only structural modification. The façades would not be structurally altered.

It is also the only element indicating this direction: the floor layout is in the other direction and the spacing is not regular.

The division into four squares is a stable geometric element sought by Carlo Scarpa6 as it gives a certain permanence to the whole.

To reinforce the identity of the structure, the walls are separated from the flooring by a void, and the passages are framed by two massive Verona stones laid on edge.

Finally, the double metal C-beam creates tension between these two load-bearing lines, as Carlo Scarpa wanted: ‘So I imagined, I found this tension of a double beam composed in a C shape, because this height was so..., in order to do it, it became so wide that it did it.’ 7

4 K. Frampton, ‘Carlo Scarpa and the adoration of the joint’, in Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, Cambridge, Mass./ London: The MIT Press, 1995, Chapter 9.

5 Di Lieto, Verona. Carlo Scarpa and Castelvecchio. Visit guide op. cit.

6 F. Semi, A Lezione con Carlo Scarpa, Milan: Hoepli, 2019. Scarpa explained the design to his students.

7 Ibid

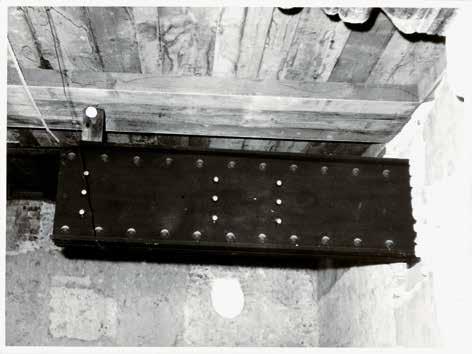

55. The double beam being assembled.

56. The existing floors were demolished. The steel beam was erected in situ, in three parts, in the first phase.

57. The floors were then laid with hollow terracotta slabs and concrete reinforcement.

Apartment block, Contrà del Quartiere, Vicenza

Carlo Scarpa 1975–1978

Introduction - History

Museo Correr, Venice, 1952–53 and 1957–60

Musée Correr, Venise, 1952-53 et 1957-60

Museo di Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, 1953–54

Musée Palazzo Abatellis, Palerme, 1953-54

Venezuela Pavilion, Venice, 1953–56

Pavillon du Venezuela, Venise, 1953-56

Canova’s Gypsotheca, Possagno, 1955–57

Musée Canova, Possagno, 1955-57

Villa Veritti, Udine, 1955–61

Villa Veritti, Udine, 1955-61

Olivetti Showroom, Piazza San Marco, Venice, 1957–58

Magasin Olivetti, Place San Marco, Venise, 1957-5 8

Castelvecchio Museum, Verona, 1957–64 and 1966–67 and 1973–75

Musée Castelvecchio, Vérone, 1957-64 et 1966-67 et 1973-75

Gavina Showroom, Bologna, 1961–63

Magasin Gavina, Bologne, 1961-63

Querini Stampalia Foundation, Venice 1961–63

Fondation Querini-Stampalia, Venise 1961-63

Zentner House, Zurich, 1964–68

Maison Zentner, Zurich, 1964-68

Brion Cemetery, San Vito d’Altivole, 1969–78

Mausolée de la famille Brion, San Vito d'Altivole, 1969-78

Apartment block, Contrà del Quartiere, Vicenza, 1975–78

Immeuble de logements-Contra del quartiere-Vincence 1975-78

Banca Popolare di Verona, Verona, 1973–78

Banque populaire, Vérone, 1973-78

Villa Ottolenghi, Bardolino, Verona, 1974–78

Villa Ottolenghi, Bardolino, Vérone, 1974-78

The Borgo residence, or apartment block, Contrà del Quartiere, Vicenza

Carlo Scarpa 1975-1978

The Borgo residence is a private development located in Contrà del Quartiere in Vicenza.

Carlo Scarpa was called in by the developer because he was having difficulty obtaining planning permission on the boundaries of the historic centre.

After much to-ing and fro-ing, not least over the shape of the roof, which the authorities wanted to be pitched, but which Carlo Scarpa wanted to be terraced, a solution was found.

Planning permission was granted in 1975, but the construction plans

were drawn up by the engineer Guiotto. Guiotto made a number of changes to the interior without Carlo Scarpa’s agreement. When Carlo Scarpa died (1978), the building was incomplete, but the main points of the project remained as planned.

Description of the project

The project comprises a building on the street and a building backing onto the garden. The garden is quite deep, and the aim behind the project was to raise the building overlooking the street by means of pilings, in order to offer a view of the garden from the street.

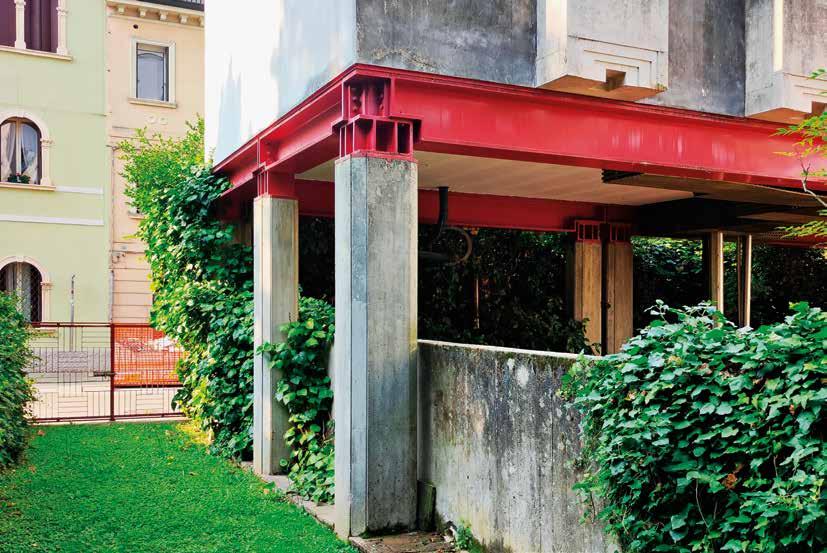

The corner column on the northern façade overlooking the garden (ill. 104)

The bolts explain the assembly using corner angles. The gaps between the vertical slats, if deliberate, dramatize the load transfer by lightening the mass at the most critical point. (ill. 105)

The bolts explain the assembly using corner angles.

The gaps between the vertical slats are deliberate: they dramatize the load transfer by lightening the mass at the most critical point.

104. Literal transparency between stiffeners.

105. The symmetry of the angle: the structure turns around.

The column forms the vertical joint between the return wall and the street wing.

The concrete column marks its independence, and thus its strength.

A column next to a wall

The column forms the vertical joint between the return wall and the ground supports of the street wing.

The concrete column marks its independence, and thus its strength. The red-painted steel beam runs around the raised building.

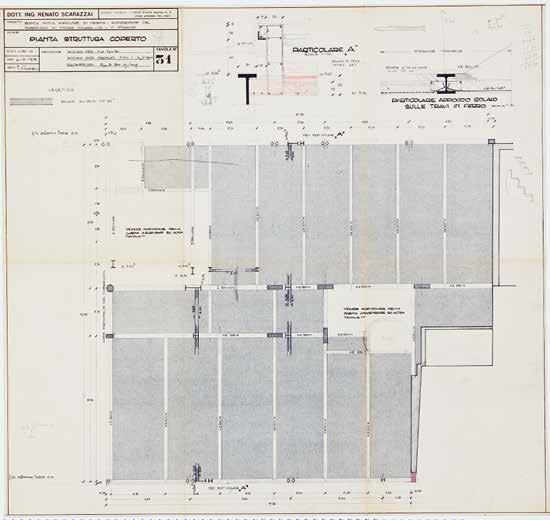

The structure of the flat roof

155. Plan of the flat roof (May 1975): the structure is made of steel, with concrete floors built with hollow terracotta floor slabs incorporated into the thickness of the load-bearing steel beams. The reinforced concrete

parapet is connected to the floor. Its upper level corresponds to that of the slabs on platforms. Some of the steel beams are higher than the thickness of the floor: the extra height is placed in the apron wall and will

be incorporated into the central part of the terrace, which is higher to allow ventilation ducts to pass underneath.

R. Scarazzai Archives – ref tb39206r.

156. The raised part of the roof runs along the loggia on the courtyard side and stops to the right of the old building. The waterproofing is hidden by slabs on platforms.

to the passage of the ventilation ducts between two main metal beams. The waterproofing is covered with slabs on platforms according to a specific design comprising Prun stone slabs with a natural finish and aggregate concrete slabs.

157. View of the roof terrace: the raised section corresponds

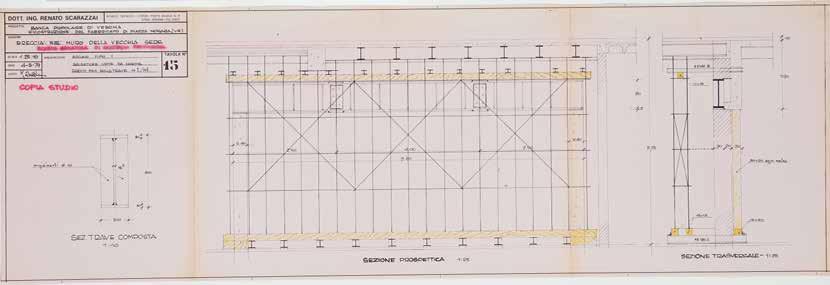

Sez. F-F

169. Working drawing of the steel structure: crosssection F-F. This section is positioned next to the lift shaft: the load-bearing beam is higher (905 mm) to support the loads of the lift shaft over a span of 9.72 m.

170. Working drawing of the steel structure: crosssection G-G. This section is located near the rounded lift. An HEM 200 beam is placed on the floor beam to support the aedicula.

Sez. G-G

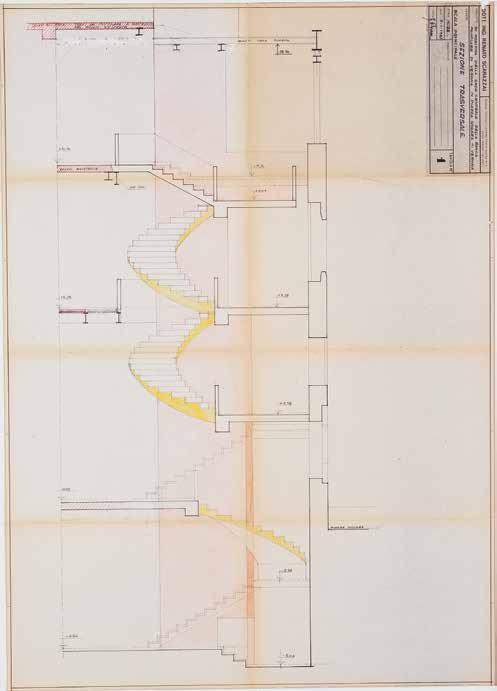

208. The spiral staircase was built in the second phase on the site of the Palazzo Righetti. The last three floors around the shaft were built using steel beams, as they were located in the existing palace. The floor at level 0.00 is made of concrete. Renato Scarazzai’s Archives.

The opening in the old part

The opening in the wall of the existing palace by means of a head frame does not show how the structure of the extension rests on the ground: the basement is not part of the project.

The beam is a welded reconstituted profile, set in place and assembled in three spliced parts by plates bolted to the web (ill. 209).

209. Plan of the opening in the wall of Palazzo Righetti to join the two buildings, which was executed during the second phase.

Renato Scarazzai’s Archives

236. View of the interior façade of the loggia of the Castelvecchio Museum’s Sculpture Gallery, Verona. The steel structure of the upper glazing rests on a folded slab of unfinished concrete, supported by vertical concrete frames, covered with a smooth grey rendering.

237. The concrete slab forms an initial ceiling laid on concrete walls clad in grey stucco. This architectural structure fits into the Gothic loggia loggia of the Castelvecchio Museum’s Sculpture Gallery, Verona.

238. Steel frames and display stands: steel is used in the furniture.mobilier.

Banca Popolare di Verona, Verona

The double beam of the entablature of the BPV façades has HEB 200 beams at the bottom, closed by plates at each support on the double columns: the plates of two successive bays are bolted together, but the position of the bolts does not constitute an embedding, only continuity in tension (or compression). On the other hand, the support of this continuous beam on double columns constitutes a stable system in his plan, due to the short distance between two columns. Only the flexibility of the columns could pose a problem (ill. 185, p. 160)

This lower beam carries no load. Its architectural role is to punctuate the attic of the façade, giving pride of place to the upper beam, which is open and carries the flat roof and its stone cornice.

In the BPV façade, the twin columns combined with the HEB beam form a stable load-bearing structure that takes the loads of the upper beam at the columns.

The upper reconstructed beam is structurally designed to transmit the floor loads to this load-bearing system. It is oversized: 600 mm high for spans varying from 2.90 m to 5.81 m.

The system of fishplates placed on the webs and not on the flanges shows that this beam does not need to be calculated with continuity. Its architectural role is to form a continuous hollow joint, unifying the entire façade, the height of which is determined by the proportion

between the supporting lines and the supported lines. The large fishplates on the webs of the upper beam provide an aesthetic and rhythmic counterpoint to the end plates of the lower beam.

Carlo Scarpa has spoken at length about these ‘ancient metopes’8

The use of steel as a counterpoint

Steel is set in a universe of masonry, rendering and stone. Its apparent incongruity makes it seem like a heroic act and forces it to speak out, because its structural role is amplified.

In the Canova’s Gypsotheca, the portico is part of the straight line, the vertical plane that runs through the entire project and forms its framework, its reference plane. Most of this vertical plane is made of masonry, and the presence of steel, which brings together elements that all the make up this plane, is a decisive factor in the construction of the project.

In the façade of the BPV in Verona, the double entablature beam and the associated columns form the frame of the façade. They contain the composition of the façade in masonry, stone and marble, separate it from the façades of the adjacent buildings and carry the cornice that anticipates the plan of the roof.

Excerpt from Un’ora con Carlo Scarpa, documentary produced

Silvana Editoriale

General Director

Michele Pizzi

Editorial Director

Sergio Di Stefano

Art Director

Giacomo Merli

Editorial Coordinator Jacopo Ranzani

Graphic Design

Annamaria Ardizzi

Copy Editor

Filomena Moscatelli

Translation Sara Noss for Scriptum, Rome

Layout Denise Castelnovo

Production Coordinator

Antonio Micelli

Editorial Assistant Giulia Mercanti

Photo Editor

Silvia Sala, Federica Quaglia

Press Office Alessandra Olivari, press@silvanaeditoriale.it

All reproduction and translation rights reserved for all Countries

© 2025 Silvana Editoriale S.p.A., Cinisello Balsamo, Milano © 2025 Bruno Person

ISBN 9788836656691

Under copyright and civil law this book cannot be reproduced, wholly or in part, in any form, original or derived, or by any means: print, electronic, digital, mechanical, including photocopy, microfilm, film or any other medium, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Available through ARTBOOK | D.A.P. 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, N.Y. 10013 Tel: (212) 627-1999 Fax: (212) 627-9484

Photo credits

ARCHIVAL DRAWINGS

pp. 47, 50, 51, 52, 55, 57, 59, 61, 68, 70, 71, 75, 76, 77, 109, 114, 123, 124, 132, 133, 147, 156, 159, 171, 175, 180, 181, 195, 204, 205 – Archivio Carlo Scarpa, Museo di Castelvecchio, Musei Civici di Verona

GIPSOTECA CANOVIANA, Possagno

Fig. 6 – Archivio Storico, Banco BPM

Fig. 7 – Archivio Storico, Banco BPM

Fig. 20 – © MAK/Georg Mayer

Fig. 28 – MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Roma. Collezione MAXXI Architettura

Fig. 29 – MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Roma. Collezione MAXXI Architettura

MUSEO DI CASTELVECCHIO, Verona

Photographs by Luca Postini

Fig. 106 – MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Roma. Collezione MAXXI Architettura

CONTRÀ DEL QUARTIERE, Vicenza

Photographs by Luca Postini

BANCA POPOLARE DI VERONA, Verona

Fig. 109 – © Eugenio De Luigi

Fig. 114 – MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Roma. Collezione MAXXI Architettura

Fig. 210 – © Guido Pietropoli – CISA A. Palladio – Regione Veneto

Silvana Editoriale S.p.A. via dei Lavoratori, 78 20092 Cinisello Balsamo, Milano tel. 02 453 951 01 www.silvanaeditoriale.it

Reproductions, printing and binding in Italy Printed in december 2025