Vibeke

Christian Holmsted Olesen

152

Shape

George

Bertolt

Dieter Rams 369 List of Works

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Contributors

Index

Image credits

designs, the GUBI chair, with its 3D moulded plywood depended on a technology patented by Achim Müller from the DDR, or what in Soviet times was known as East Germany, almost as if he were looking back to a system that he rejected long ago. It is a burst of energy that shows that it is not necessary to follow Lars von Trier or Bjarke Ingels to move over and above the familiar language of Danish culture.

Rubber chair NON

I showed Sven Lundh the ‘design’ of a nondesigned, nonstyled chair – it had to look like it was made by a child asked to draw a chair. I just transferred it to threedimensionality.

I wanted to make it so anonymous that it could stand in any environment without attracting attention – almost invisible – so screamingly silent that this silence would become sound itself. Anonymity should become its Identity

It had to be as good for a Baroque interior as for a Frank Gehry building.

BOUND-UN-BOUND, 2002

INFELTRUM

felt walls, felt carpets, felt boots, felt hats as felt birds and felt chairs

wool felt, rabbit, hare and fox fur felt, matted and entangled

I love felt – the oldest textile ever made by our ancestors. Felt was invented to fit between the cold and heat of life

Installation for the SE2001 exhibition ‘Lebensraum’ with the participation of modiste Susanne Juul and textile designer Kristiina Wiherheimo.

Solid and pure in form as monoliths, the MONOLITE has a selfbearing tabletop without any supporting frame. Matte monochrome coating reinforces the monolithic character.

Like monoliths, it is firm and sturdy, but the MONOLITE is remarkably lightweight. The stiffness of the tabletop permits a long stretch without deflection, and its wide stance legs are firmly planted on the floor.

DS Rembrandt, of course, worked with demanding clients, just as a designer might; just think about The Night Watch, its need to fit a given space and to feature all the patrons. But Darwin is perhaps more relevant in a discussion about design than art. Surely the history of the chair can be seen as a matter of evolution and natural selection. It’s not driven only by style; materials and manufacturing methods are critical to an understanding of the meaning of a design.

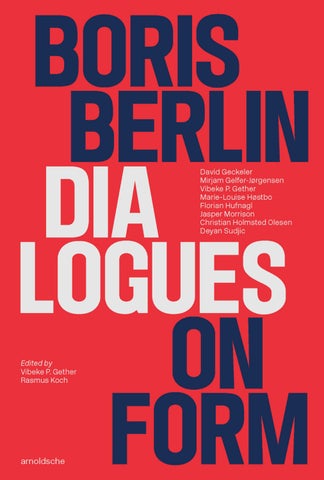

Since coming to Denmark from St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad) in 1983, Boris Berlin has made a significant contribution to Danish design, leaving his mark on the furniture sector with a style that contrasts with established approaches among Danish furniture manufacturers. He is based in Denmark and can be thought of as a Danish designer, but his background has given him a different outlook and his work is international in orientation.

It is, then, no easy task to describe the man and to situate his work in the context of contemporary Danish furniture art, something I am not alone in struggling with. It is hard to identify a common thread that connects his works.

One might wonder why, in design history and other visual creative fields, we feel a need to classify a designer’s work and place its characteristics in a stylistic hierarchy. But maybe it is not so surprising when we consider the wealth of design objects produced over the last hundred years or so. Since Darwin proposed his theory of evolution, Western art history (within which design, for good or ill, is typically classified) has used form and style to give a wider perspective. Historians are still concerned with the authenticity of works of art: is a piece from Rembrandt’s own hand or ‘just’ his workshop? This trend is exacerbated by the art market and has also affected the supply and sale of furniture, with an early version of a Finn Juhl chair fetching a higher price than a later one, for example. For at least a hundred years, architects have rebelled against their forced inscription within style history – not, as has been claimed, in search of a new style but because of a desire to choose shape and form in relation to context and materials. People still characterise architecture from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a confusion of styles, but this is clearly misleading; the task at hand defined the choice of style. Now, design history once more faces the task of classifying the unmanageable volume of production. And it still makes sense to use stylistic traits to do so.

But Boris Berlin hasn’t chosen one overarching stylistic trait to connect his various contributions to design, which also span a vast range, from the PENOL pen to a bus company’s graphic identity, where his unconventional designs helped them attract attention, and thus customers. As regards furniture, he has written a new chapter in the story of ‘the Danish chair’, one quite different from the romanticised narrative that furniture manufacturers, auction houses and museums market today, where each piece (presented as a unique, independent work) is elevated to the pantheon of art history. For example, recent editions of Wegner’s chairs are sold with the architect’s ‘signature’, ten years after his death … This is true not only of Danish design; most Scandinavian design holds fast to forms and trends that met with international success in the mid twentieth century and continues to market them as exclusive craftsmanship. Because there are people who want to buy this narrative which stresses craftsmanship, functionality and a national tradition that combines these two ingredients. Their appeal is probably also linked to the form itself and a certain sculptural quality. The design companies that have secured the copyright (or bought it from the heirs) not only continue to recycle furniture and cutlery by producing them in different materials, sizes or shifting, fashionable colours, but they also produce objects based on architects’ drafts that never made it beyond the drawing board. New companies can buy a well-known name, such as Kähler, and produce ceramics under the name Hammershøi, knowing full well that most people will associate it with the famous painter and not his lesser-known brother. There is, it appears, no limit to the exploitation of what

What can be more natural than sitting on a rug?

Our ancestors did this from the dawn of time. I was interested in felt for quite a while and took several study trips to different European manufacturers to learn more about it. Starting with wool felt, I eventually discovered the existence of needle-punched technical felt.

When I came to the factory producing felt, I saw the smoking spot in the yard where some halfbroken chairs covered in felt were standing. I said to myself, ‘Thank you – the chair is done!’

The GUBI Chair II is made from polyester fibre, a significant part of which has been extracted from used plastic water bottles and transformed into felt. In one single process, two mats made from this felt are moulded around a steel tube frame, water cut, and the chair is ready for use.

NOBODY’s additional qualities include its lightness and stackability, good air circulation, the perfect acoustic properties of the PET felt, and ease of cleaning.

It was natural to follow NOBODY with the appearance of Little NOBODY – a kid’s chair. It didn’t need any instruction for use – most children immediately crawled inside it.

Can you remember your beloved teddy? That cuddly childhood toy who followed you everywhere, day or night? Who comforted you and kept you safe? Perhaps it was a bear, or a dog, or a rabbit

BUNNY is a wing chair that reinterprets the traditional design. Instead of the austere and stiff-backed companion in which our grandfathers used to retire to read the paper, Bunny is meant to be a loving friend – a great big cuddly toy, large enough to comfort an adult.

BUNNY is playful, funny, sybaritic, and sensual, but with a twist – bound and shaped by the rope drawn taut across its soft ‘body’.