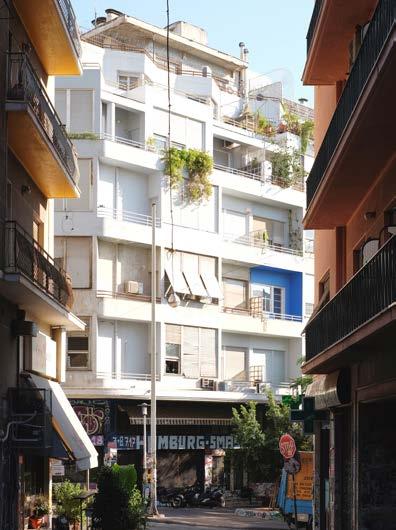

Panagiotakos

1932–33

61 Arachovis / 80 Themistokleous, Exarchia

This polykatoikia block was the first building to combine the bay and balcony projections permitted in the 1930s into a continuous layer covering the entire structure. The composition consists of a powerful rhythmic alternation of mass and void, articulated once again on the staggered floor as an expressionist serrated fold. The numerous balconies and fully glazed bay windows of the cantilevered layer form a habitable facade creating the image of a vertical neighbourhood on Exarchia Square. In programmatic terms, the building was developed as a kind of urban unité d’habitation. It contains large apartments on the main floors and small two-room units on the staggered ones, restaurants and stores on the ground floor, Athens’ first underground garage, and communal facilities including a bar on the roof. The name ‘Blue Polykatoikia’ derives from the original deep blue colour scheme, created by the painter Spyros Papaloukas.

25 Metsovou / Bouboulinas, Exarchia

Unlike all his other interwar polykatoikias [g62], this work by Takis Marthas is characterised by an exceedingly elegant and purist modernism. Bay windows and cantilevered balconies form a kind of second skin that seamlessly wraps around the structure with a rounded corner. The flat and wide attic beams and the downward overhanging balcony skirts convey the impression of a thin surface that is geometrically cut open to reveal the interior core of the building and connect it to the surrounding urban space. In the spatial arrangement of the apartments, Marthas reverted to the original concept of a central hall as a gathering place [g22], which here again forms the focal point of the living zone. In the layout of the third floor apartment, the hall merges forward into a living room (salóni) projecting into the street space and connects laterally with an office and a spacious dining room via two large doorways opposite one another.

In the early 1930s, Nikolaos Nikolaidis began to transform the sculptural curves of his earlier Art Nouveau designs into the abstract geometry of modernism. In this design, he did not fully utilize the side of the plot and had the building extend out onto Egypt Square as a giant structure from the depths of the lot. A clock on the upper left side emphasises the public appearance. An expansive bay-balcony composition sweeps around the building, which is rounded at the corner. While the building rises six storeys laterally, it staggers back where it faces the square above the third storey and ends with an elegant wave-shaped facade on the top floor. Behind it, curiously enough, are only the sleeping quarters of two apartments. The building has underground parking and a service lift in a glass-roofed atrium, replacing the uncomfortable steep exterior service stairs for the first time in a polykatoikia building.

Scale 1:500

Fig. 01: The hall (1930–1960)

26qm hall:

0 10m 5

Vasilios Kouremenos Kouremenos Apartments, 1933-35

1933–35, 17 D. Areopagitou, Makrigianni [g22]

Vasilios Kouremenos

Hall size: 26 sqm

1936, 10 Skoufa, Kolonaki [g74]

Vasilios Tsagris

Hall sizes: 20 + 20 sqm

Hall:20qm / 20qm

0 10m 5

Vasileos Tsagris Apartments Skoufa 10, 1936

Hall:5qm / 7qm / 10qm

0 10m 5

Aristomenis Proveleggios Chatzidaki Apartments, 1957-58

1957–58, 11 G. Chatzidaki, Patisia [g162]

Aristomenis Proveleggios

Hall sizes: 5 + 7 + 10 sqm

1957–58, 34 Mithimnis, Platia Amerikis [g158]

Dimitris Papazisis

0 10m 5

Hall sizes: 3–12 sqm

Dimitris Papazissis Apartments, Patision 172, 1957-58 3qm - 12qm Hall:

hall never appears as a corridor, but always as a room, due to its balanced proportions and mostly symmetrical arrangement. With its special connection to the living area with glass walls and sliding doors, the hall preserves the idea of a place where gathering and living are fundamentally indistinguishable. The Greek greeting “Come in to the hall” (Eláte sto chól) basically is an invitation to enter the living room.

Front and back

The concept of zoning, as adopted from the hôtel particulier model, aimed to separate subordinate and informal parts of the apartment from an official and public part. It introduced a hierarchical order to the polykatoikia floor plans that divided the dwelling into two spheres or halves. The arrangement was more or less pre-configured in the two unequal sides of the inner-city block: a public, representative and presentable living area on the architecturally designed street facade and a private, non-representative and hidden area consisting of bedrooms and service rooms on the inhospitable side of the backyard (akályptos). Memos Philippidis described this hierarchical arrangement as a patriarchal order: the spaces facing the street as the ceremonial world of men and those at the back as the excluded realm of housewives, children and domestic servants.5

The strict separation of the two spheres was ensured by a double access system that was common well into the post-war period: a main staircase and a service staircase, which was later replaced by a service lift, provided each apartment with official and informal access and divided the apartment users into two classes. In a spatial constellation of the two staircases that was often found, however, the asymmetrical relationship between representative and hidden parts of living was brought into an astonishingly complementary equilibrium: in the back-to-back arrangement of the staircases, the two spheres, which had been widely separated from each other in the apartments, suddenly move very close together and appear like two sides of the same coin: inside, the realm of apartment owners and visitors who meet in the stairwell; and outside, the realm of servants and perhaps housewives and children who meet on the balcony walkways that run in front

of the stairwell windows (Fig. 02). When Kyriakoulis Panagiotakos added clear glass to his stairwells [g46], it seemed to be a deliberate attempt to make visible the interplay of ‘stage’ and ‘backstage’ parts of life. But perhaps it was Takis Zenetos who brought this dualism into a balanced symmetry in his 1972 design [g270]: by fitting both sides of the building with continuous balconies, he juxtaposed the served and serving parts of living as equal.

Functional linkage

Creating clear three-part zoning, especially in floor plans with several apartments on each floor, was no easy task. The architects of the 1930s seemed to search obsessively for perfect zoning, culminating in the question of how to optimally position the kitchen areas: the kitchens had to be connected to the common service staircase on one side and simultaneously lead directly to the dining room on the other with a ‘discreet’ service door – a connection that was often inevitably and unattractively disrupted by the access to the sleeping areas [g46] [g58]. Modern Movement architects Polyvios Michailidis and Thoukydidis Valentis solved this problem best by moving the bedroom and kitchen areas apart and placing them on opposite sides of the living area [g32] [g38].

In general, tripartite zoning was decisively reinterpreted under the influence of the Modern Movement. And here it becomes understandable what Manolis Marmaras had in mind when he described the transition from the concept of hall to the concept of zoning as a “transition from a traditional way of living to another, innovative and contemporary”.6 In the Modern Movement designs, the hierarchical opposition of representative and non-representative areas of the hôtel particulier model was dispensed with. Three-part zoning was reduced to a merely functional order, an equal triangle of functions in which a new interplay between everyday living activities was established. The sleeping areas were significantly upgraded, provided with their own outdoor spaces on the courtyard side. Living and dining rooms were increasingly linked to form coherent living areas that once again became the centre of family life [g30] [g44]. Renewed attention was paid to the nexuses and interactions between the three zones: