DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD

Xa Sturgis

TRACING LOSS AND CONNECTING LINES THOUGHTS ON PIO ABAD’S DRAWINGS

Lena Fritsch

TO THOSE SITTING IN DARKNESS

Pio Abad

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

PIO ABAD AND BRINGING TO LIGHT DARK HISTORIES

Vera Mey

DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD

Xa Sturgis

TRACING LOSS AND CONNECTING LINES THOUGHTS ON PIO ABAD’S DRAWINGS

Lena Fritsch

TO THOSE SITTING IN DARKNESS

Pio Abad

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

PIO ABAD AND BRINGING TO LIGHT DARK HISTORIES

Vera Mey

Lena Fritsch

A drawing is an autobiographical record of one’s discovery of an event – seen, remembered or imagined 1 John Berger

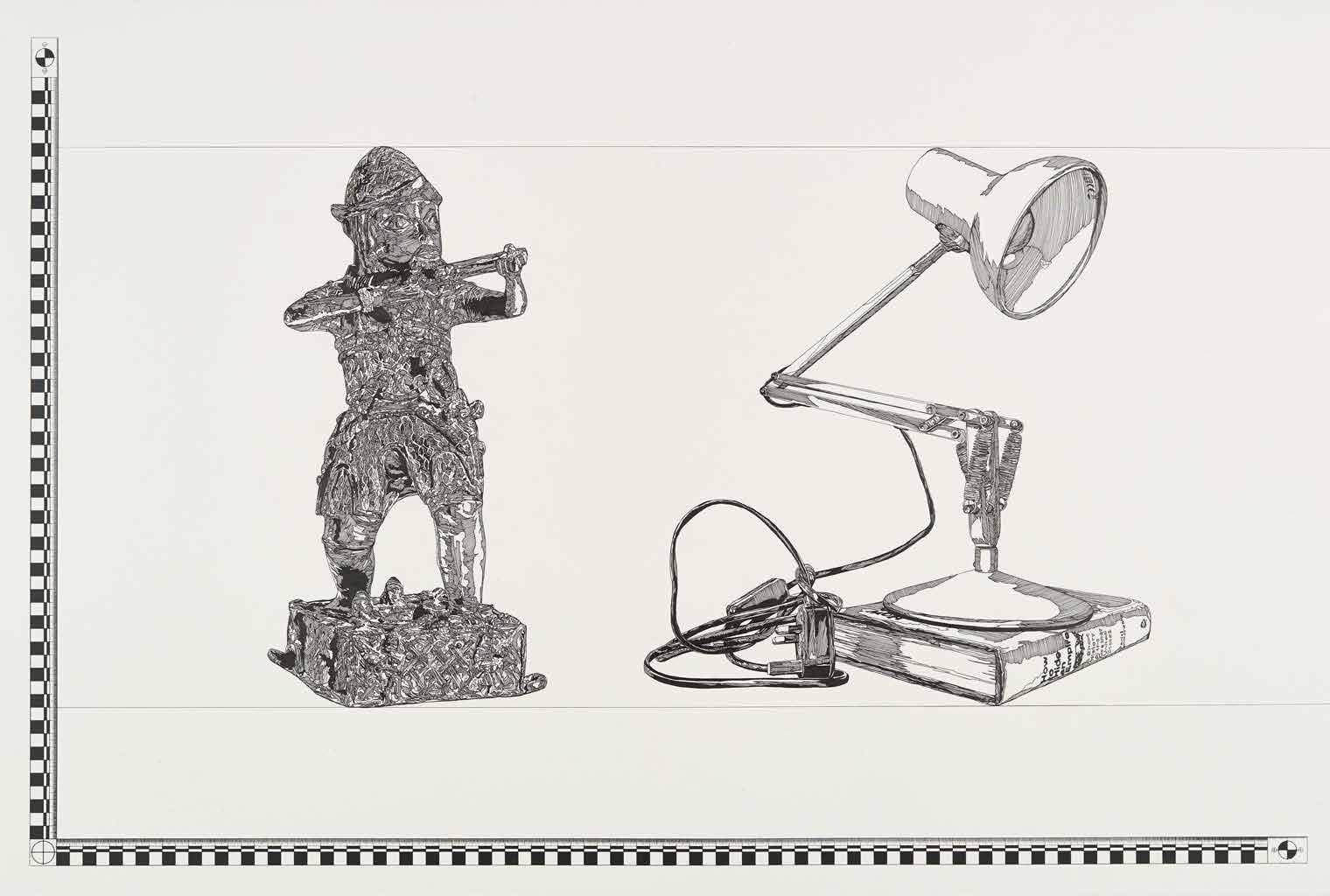

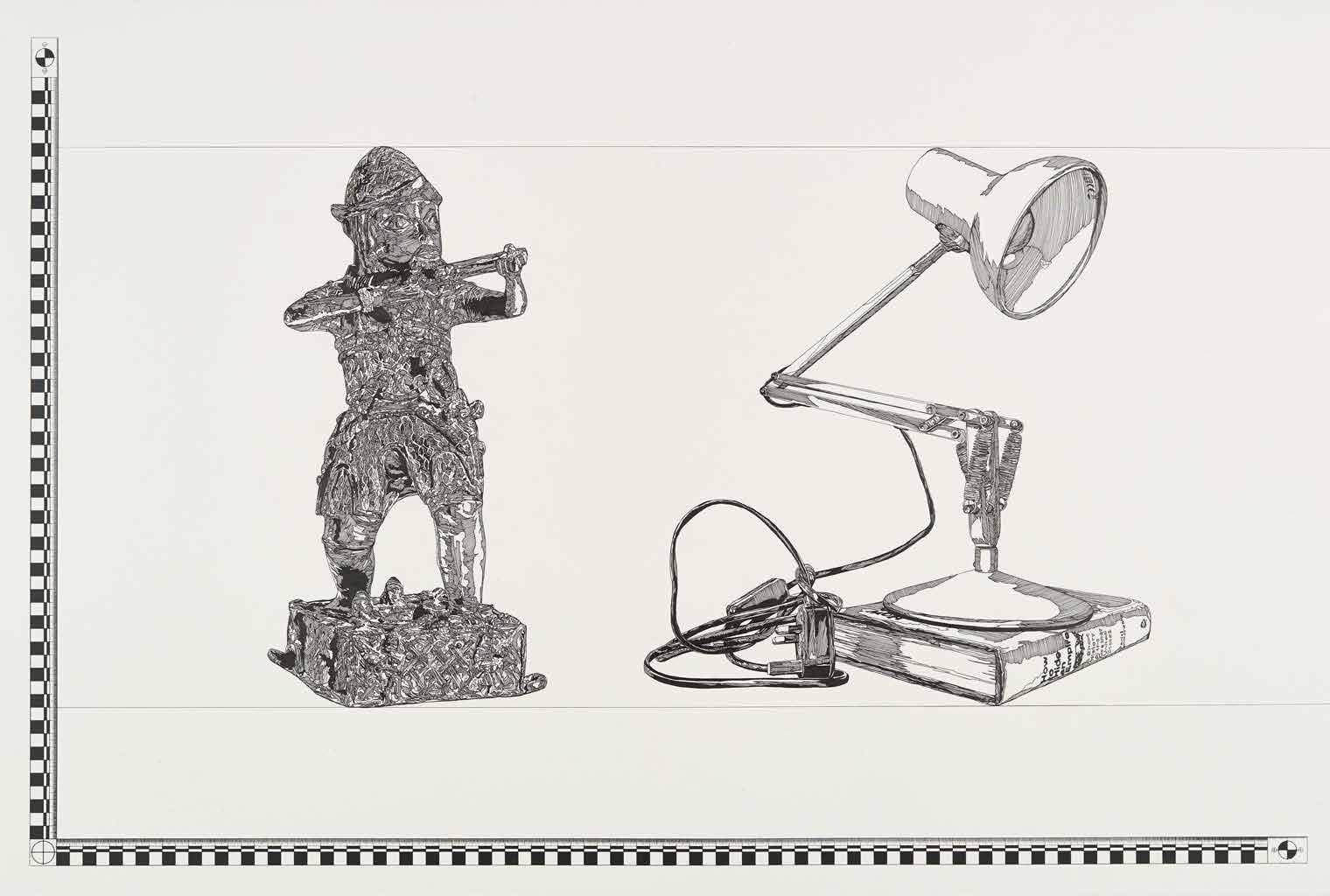

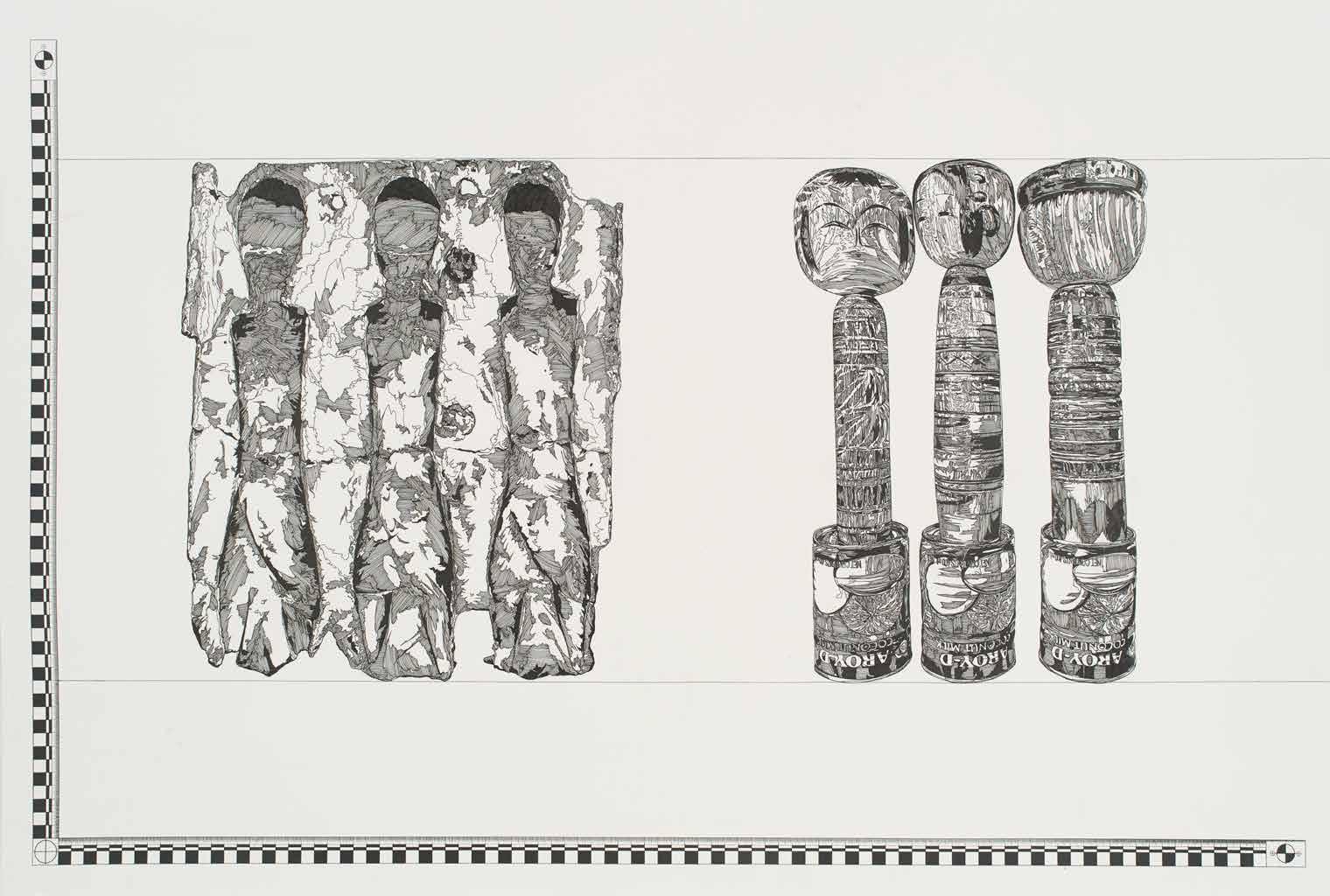

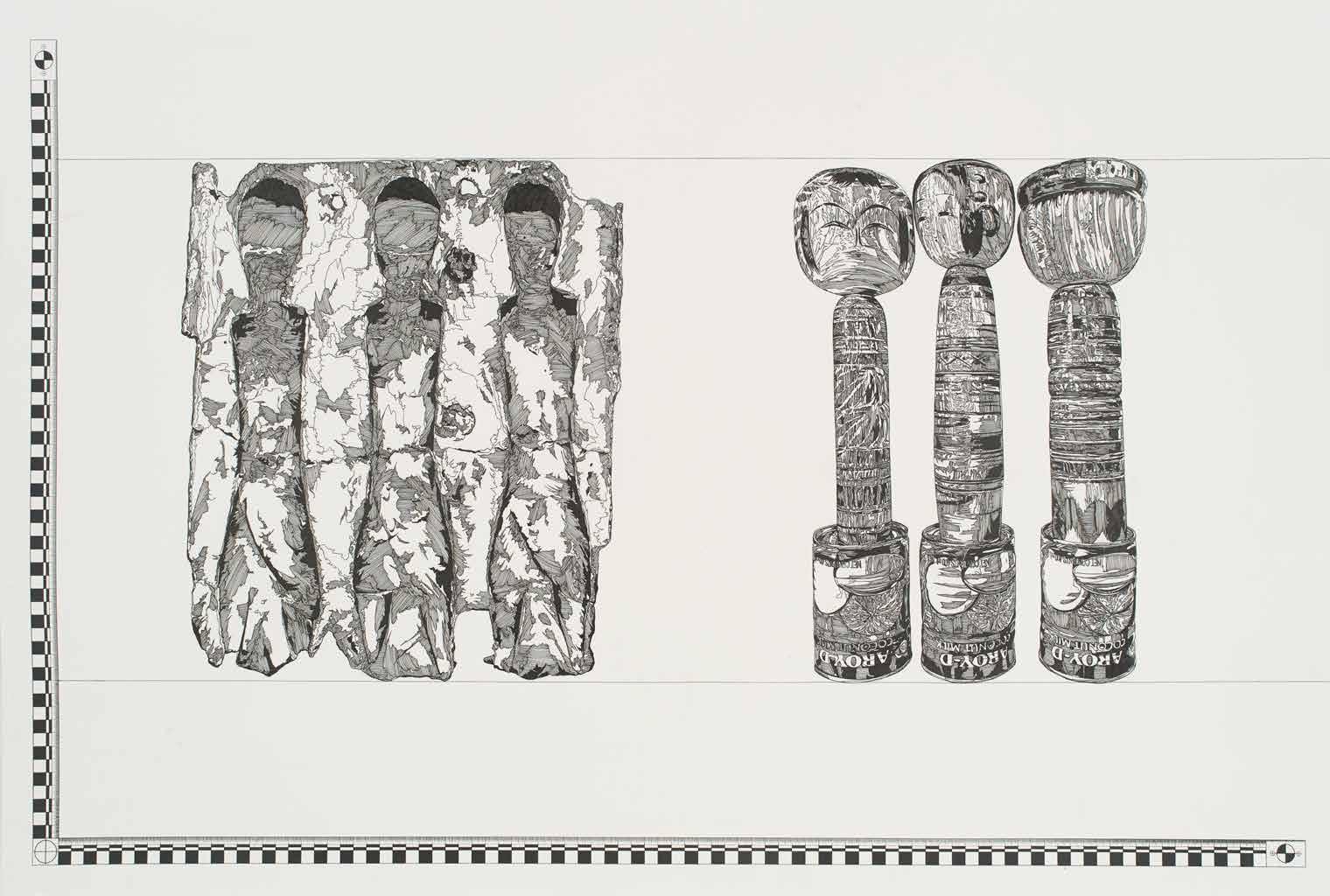

A small, elaborately decorated warrior figure rides towards Isamu Noguchi’s iconic rice paper lamp, which is placed on top of two thick books: a book on Filipino American artist Alfonso A. Ossorio, and Parapolitics, a reader on cultural politics during the Cold War, published by Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 2021. A meticulously ornamented leopard sculpture approaches a stack of exhibition catalogues, art books, and novels An elongated African mask faces away from us, ignoring the photograph of a woman that is placed on top of a jar and Hisham Matar’s slim travelogue A Month in Siena. These surprising encounters between objects happen on paper, in detailed black lines on a white background. A fine measuring bar on the left and bottom of the image, and a thin horizontal line above and below the objects subtly indicate their height: the sculpture on the left and the things on the right always have the exact same height. The drawings are part of a series entitled 1897.76 36 18 6 (pp.64–91). On the left side they feature ancient sculptures from Benin that can be found in the British Museum, and on the right they show personal objects in the artist’s home

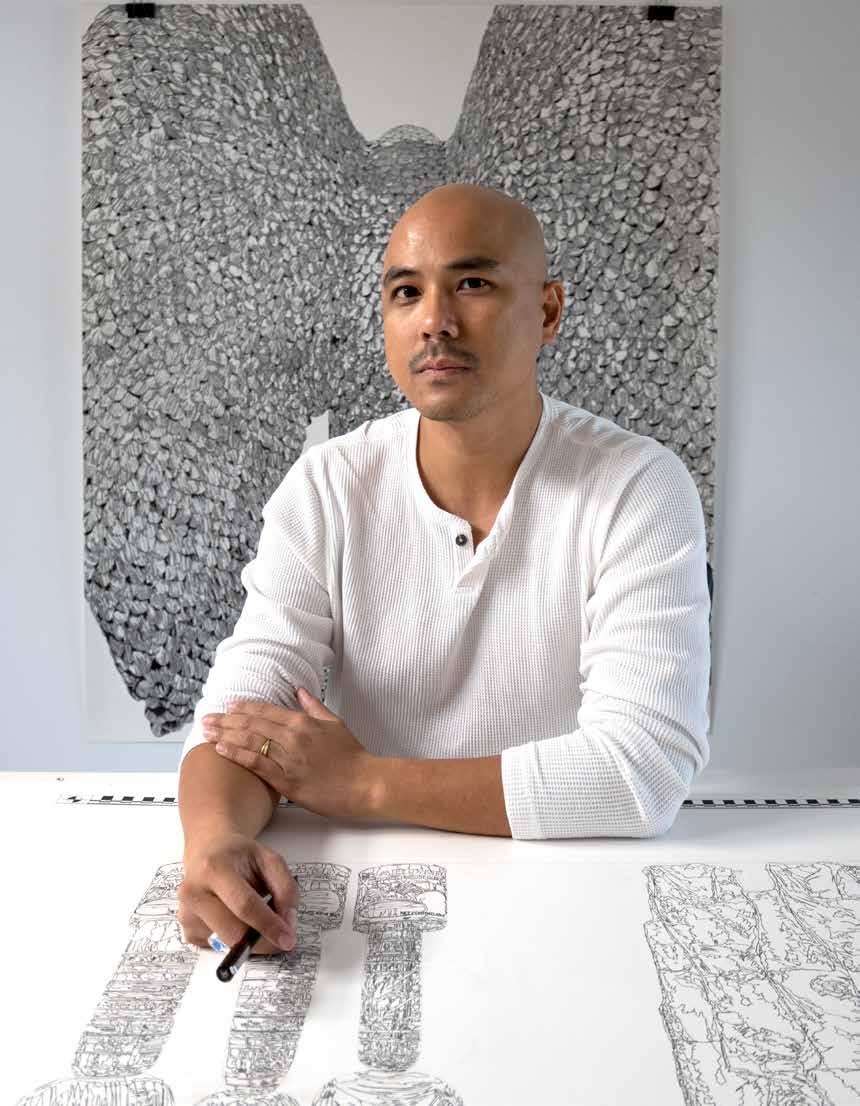

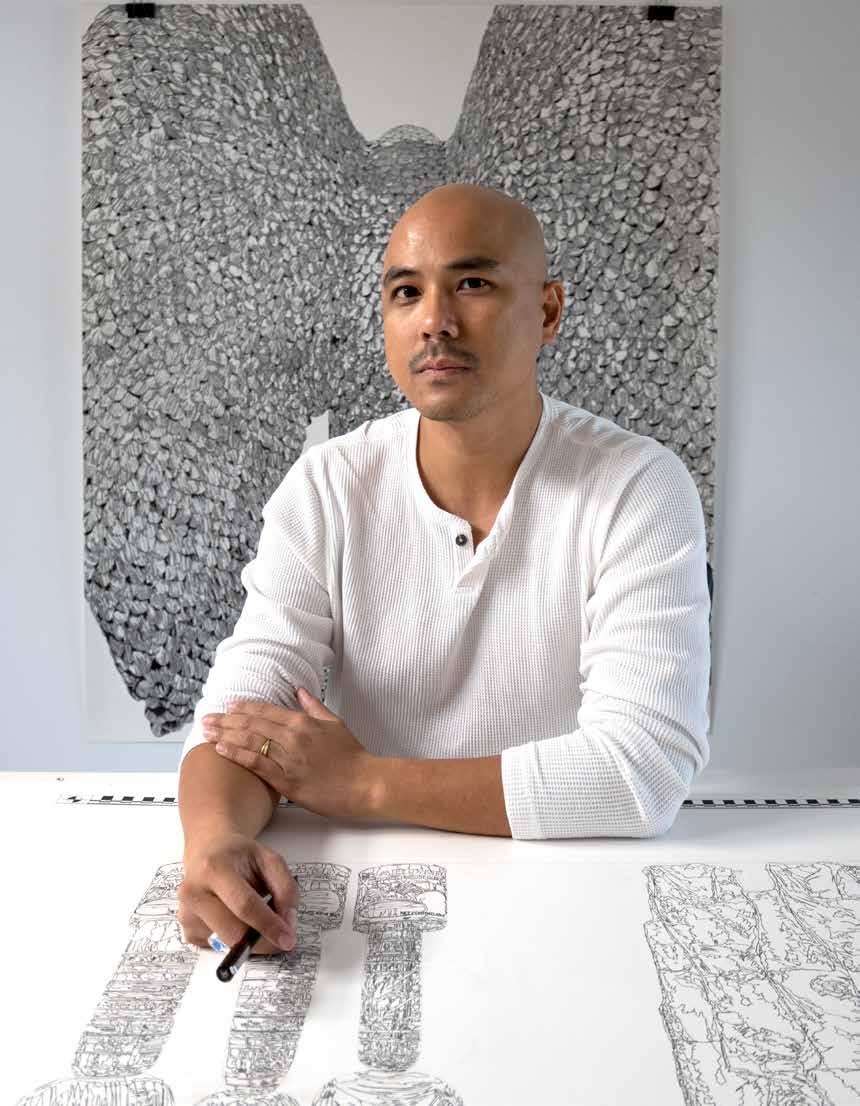

The series was made in 2023 by London-based artist Pio Abad (b.1983). Deeply informed by the history of the world and particularly the Philippines, where Abad was born and raised, his works ‘draw out’ lines between historical incidents and people, and our lives today Abad’s approach of connecting the past with the present through visually alluring and thought-provoking projects

‘IN FREEING GIOLO FROM THE ARCHIVES I WANTED TO PORTRAY HIM AS A TRAFFICKED BODY AND A GRIEVING SON, NOT A SPECIMEN OF CURIOSITY.’

As a project that seeks to articulate both a shared and a personal vocabulary for loss, it seems only fitting that this story of entanglement begins with piracy.

In August 1687, the English pirate William Dampier landed in an island south of Taiwan that he would name the Duke of Grafton’s Isle.14 Despite gaining a buccaneering reputation, Dampier was a keen observer of everyday life. He recorded that the island inhabitants were largely seafaring but built their homes on hills and mountains, they were ‘greedy’ for iron, which they used for everyday tools, and sugarcane wine was widely consumed. Dampier’s description in his diary, later published as New Voyage Round the World (1697), provided one of the earliest pictures of a Pacific Islander society during the Iron Age.

Duke of Grafton’s Isle would later be called Batan Island, the largest island in the Batanes archipelago and the northernmost province in the Philippines. Crucially, Batanes is where I locate my place in the world. My father was born on the island in 1954 and my family have a long history of living on the island, stretching back to the time of Dampier’s brief layover. It is where I get to spend time with my family, in a house that my father built overlooking the Pacific. It is where my ancestors and, more recently, my mother are laid to rest.

Dampier stayed in Batanes for around three months and then set sail, carrying on with his plan to travel south where he imagined islands full of nutmeg, cloves, and gold waiting to be exploited. Dampier found neither minerals nor spices, but instead travelled back to England empty-handed apart for his journals and a young man he purchases as slave in Mindanao named Giolo.15 In his diaries, Dampier elaborates on Giolo’s appearance:

He was painted all down the Breast, between his Shoulders behind; on his Thighs (mostly) before; and the Form of several broad Rings, or Bracelets around his Arms and Legs. I cannot liken the Drawings to any Figure of Animals, or the like; but they were very curious, full of great variety of Lines, Flourishes, Chequered-Work, etc. keeping a very graceful Proportion, and appearing very artificial, even to Wonder, especially that upon and between his Shoulder-blades … I understood that the Painting was done in the same manner, as the Jerusalem Cross is made in Mens Arms, by pricking the Skin, and rubbing in a Pigment.16

Upon arrival in England Giolo was sold once again, and almost immediately put on display as a curiosity at the Blue Boar’s Head Inn in Fleet Street, where he is fictionalised as ‘The Painted Prince.’

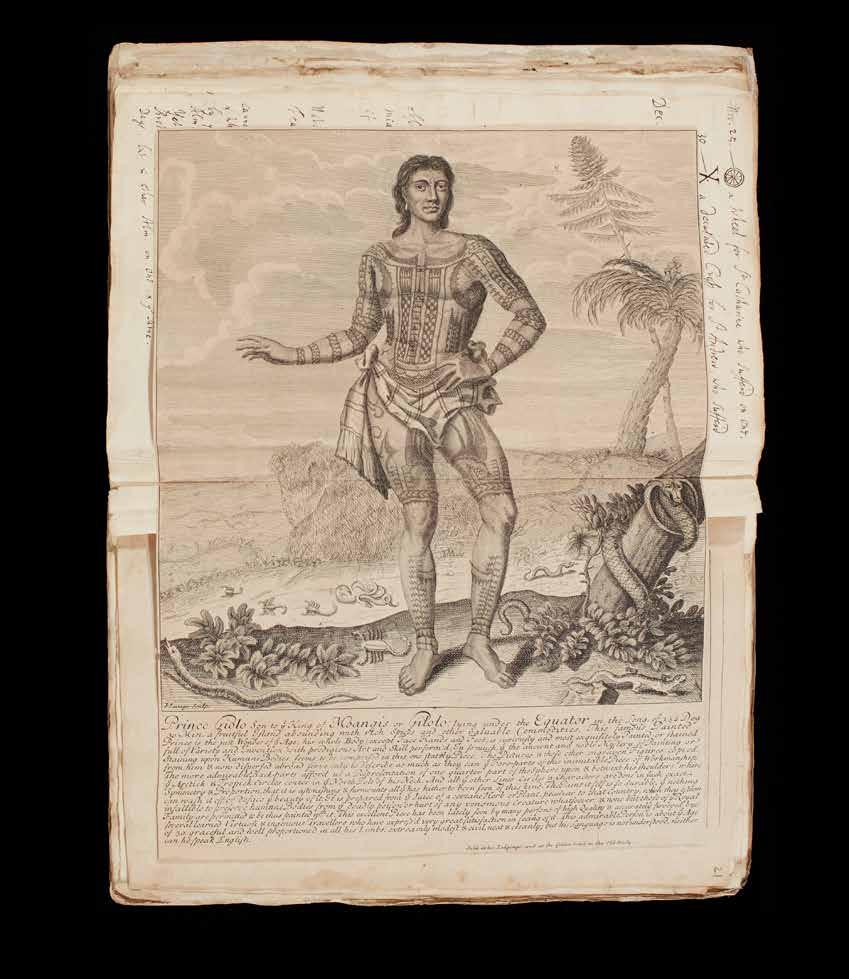

A 1692 etching by John Savage advertising Giolo’s public appearances survives in the catalogue to the

Musaeum Pointerianum, the cabinet of curiosities that John Pointer donated to St John’s College in 1740. In the only visual representation of Giolo his tattoos are richly detailed, but his appearance is closer to a classical contrapposto sculpture than a young man from Mindanao in the late seventeenth century. He was on show every day from nine in the morning to midday, and then from three in the afternoon to seven in the evening. Private viewings were also offered, where Giolo would be sent to London homes in a coach at any appointed time. However inaccurate, the etching is perhaps one of the earliest depictions of a trafficked Filipino body – a narrative of exploitation that continues to this day.

A handwritten page attached to the etching further elaborates on Giolo’s life. Three months after arriving in England Giolo was brought to Oxford where he would succumb to smallpox. His body is interred in an unmarked grave at St Ebbes churchyard. A fragment of his tattooed skin removed and put on display at the Anatomy College in Oxford University. Reading this account of Giolo’s life, it was a passage detailing his journey to England that struck me:

This Indian prince was taken Prisoner by an English Man of War, as He and his Mother were going out upon the Sea in a Pleasure-boat. His Mother dyd on Ship-board; at which the Prince her Son showed abundance of concern and sorrow.17

While thinking about Giolo’s story I found myself looking at Indigenous poetry from Batanes, where seafaring, filial love and lament are inextricably bound. One folk lyric in particular I could imagine resonating with Giolo’s grief.

mana an pakulibuten mo yaken du bulsa mo ta pidavatavayay nu daya du dapsapen, as pachidektekay ko na du pamtangan 18

(why don’t you put me in your pocket so that my blood will be mixed with the water at the bottom of the boat, and so that, perchance, I may be lost with you in the sea)

Giolo’s Lament traverses his tattooed hand through eleven engravings on marble arranged on the gallery walls like a musical score. A spectral limb grasping for something out of reach, perhaps reaching out for a body lost at sea. Inscribed on pink marble, Giolo is at once monument and flesh, etching the forgotten prince into permanence, but also reminding us of his fragile humanity. In freeing Giolo from the archives I wanted to portray him as a trafficked body and a grieving son, not a specimen of curiosity.

In the gardens of Blenheim Palace sit a pair of leaden Sphinx sculptures bearing the intriguing likeness of Gladys Deacon, Duchess of Marlborough, who lived in the palace during her tumultuous marriage to Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough. The French American socialite was the duke’s second wife, after an unhappy arrangement with the wealthy heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt, whose family fortune was deployed to refurbish the crumbling palace and rescue the SpencerChurchills from penury, in exchange for a royal title.

Spencer-Churchill’s marriage to Deacon was equally fraught. Despite the grandeur of Blenheim, the couple could not bear living together, with Deacon often lamenting her husband’s patrician cruelty. There were even accounts of Deacon placing a loaded revolver next to her during dinner and threatening to shoot the duke on multiple occasions.19 Despite this animosity, the duke had her immortalised in the palace grounds with the Sphinxes – at once a monster and a muse.

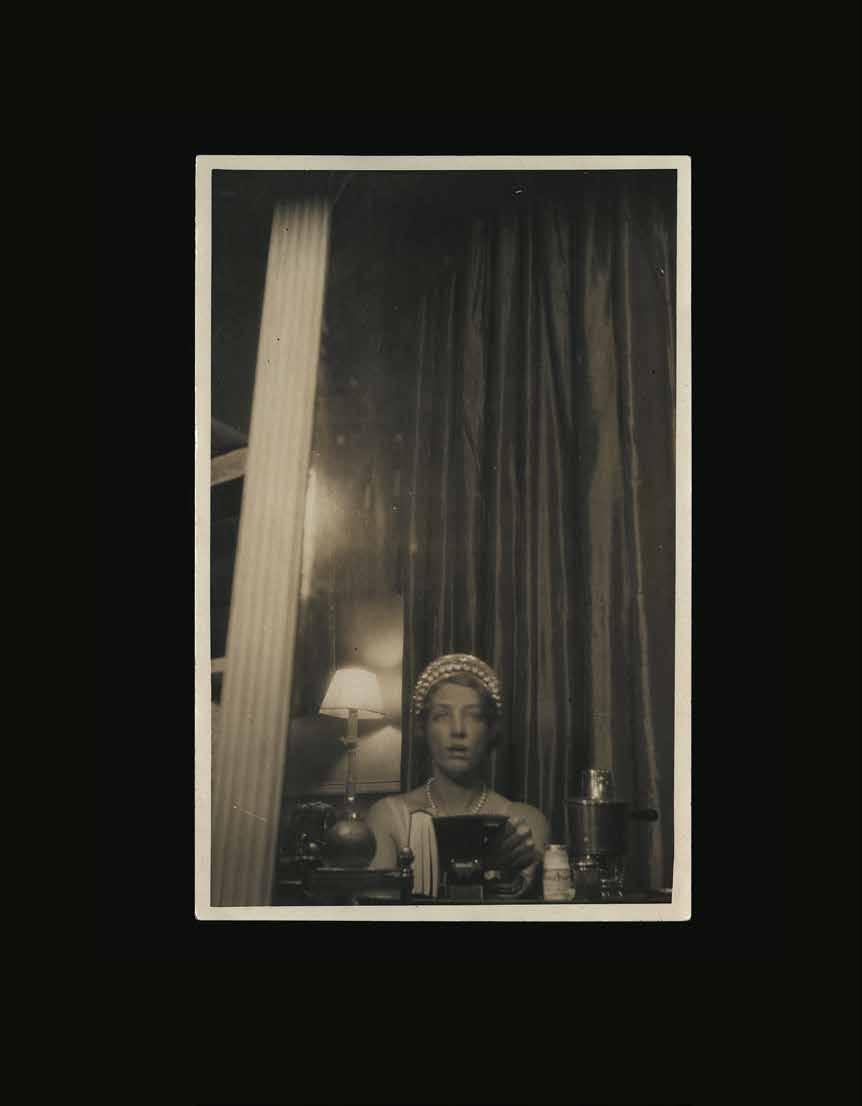

I ended up in Blenheim after coming across an intriguing photograph of Gladys Deacon taking a photograph of herself in front of a mirror – a proto selfie –with a pearl and diamond diadem perched on her head. The Kokoshnik tiara, as it is known, has assumed an almost mythic status owing to its controversial provenance.

The diadem, made up of 144 diamonds and 25 large pear-shaped pearls, is patterned after the kokoshnik, a traditional folk headdress worn by Russian woman. It was a favourite among several Romanov empresses, most notably Maria Federovna, the mother of Tsar Nicholas II, the last tsar of imperial Russia. After the execution of the Romanov family in 1918, the tiara, alongside the rest of the Russian crown jewels, was nationalised by the Bolshevik regime, and in 1927 was auctioned by Christie’s in London on behalf of Joseph Stalin’s government. The proceeds from the sale were intended to fund agrarian reform in newly Communist Russia – an effort that would

prove disastrous, leading to the complete collapse of agricultural production in the Soviet Union. It was during this Christie’s sale that Gladys Deacon acquired the tiara, via an intermediary. The Marlboroughs didn’t own any family jewels, so Deacon decided to buy her own.20

My first glimpse of the tiara, which sparked this longstanding fascination with its history, was during a press conference by the Philippine government in Manila in February 2016, where it unexpectedly appeared as the centrepiece of a horde of jewellery that the government had confiscated from the Philippine kleptocrat Imelda Marcos. It seemed that Marcos has purchased the diadem shortly after Deacon’s death in 1978 to fulfil her own imperial fantasies. After the fall of the Marcos’s kleptocratic dictatorship in 1986, Imelda’s horde of fine jewellery was seized, the Kokoshnik tiara amongst them.

A televised press conference announced the sale of the Marcos’s horde, to be held by Christie’s with the proceeds going towards agrarian reform in the Philippines. However, the victory of Rodrigo Duterte, a Marcos sympathiser, in the presidential elections later that year, and the subsequent election of Imelda’s son, Ferdinand Marcos Jr in 2022, have ensured that the auction of the ill-gotten jewellery has never taken place. The Kokoshnik tiara remains locked in the central bank vaults in Manila, condemned to a state of irresolution.

In the exhibition, the Kokoshnik tiara appears as a pair of identical bronze sculptures, meticulously reconstructed from news footage and scant archival documentation of Deacon wearing the piece (no footage of Imelda wearing the tiara exists in public), by my wife and collaborator, jeweller Frances Wadsworth Jones. Facing each other akin to the Sphinxes in the garden, the diadems bear witness to each other, their outrageous provenance and recurrence in history turning them into intimate and enduring testimonies to endless cycles of violence, upheaval, and impunity.

‘THOUSANDS OF THESE ORPHANED WEAPONS ARE STORED IN MUSEUM VAULTS, OFTEN REMAINING IN THE DARK AS THEY FALL INTO THE CRACKS OF RECOGNISED TAXONOMIES.’

In putting together her exhaustive inventory of Philippine artefacts, Marian Pastor Roces quickly realised that the most recurrent object in museum collections was the bladed weapon from Mindanao, the southern region of the Philippines where the Indigenous tribes, governed by sultans and datus, adapted Islam into their belief system. The founding collection of Lieutenant General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, which developed from an interest in the development of weaponry, included kris swords from Mindanao – wavy double-edged weapons with handles made of precious wood and bone carved in crocodile or bird-like forms, with mythic symbols incised on the blade

These krises are not just viewed as weapons, but as personal possessions made for individual warriors carrying a spiritual potency bestowed upon its owner. Thousands of these orphaned weapons are stored in museum vaults across the Global North, often remaining in the dark as they fall into the cracks of recognised taxonomies. In the words of Pastor Roces:

The blades were put to sleep, bloodless, with a few words attached about their removal from conflict sites (sometimes from the hands of the dead) … In their interment, tens of thousands of swords, daggers, head axes, spears, and other lethal projectiles and blades, were themselves severed, as though amputated limbs from the body of the Philippines’ tribalisms and martial arcana.21

These weapons were collected, not for their spiritual significance and exquisite craftsmanship, but were intended as tools to distinguish between civilisation and barbarism – between the natives willing to capitulate to Christianity and those that resisted conquest. Most of these weapons were gathered during the PhilippineAmerican War in the early twentieth century, when American colonisers waged asymmetric battles against the Moros, as the local Muslim population in Mindanao was known. The most horrific among these atrocities took place in the province of Sulu in 1906, where entire

families were murdered as they sought shelter in the crater of a dormant volcano. ‘We abolished them utterly, leaving not even a baby to cry for its dead mother,’ wrote Mark Twain bitterly after hearing of the massacre of over 1,000 men, women, and children.22

Since the arrival of the Spanish on Philippine soil, the Indigenous people of Mindanao have waged a secessionist struggle, which continues to the present day, against a predominantly Christian national government that has inherited the dehumanised depiction of Moros from their colonisers. The very categorisation of Moro weaponry as Philippine artefacts could be considered an act of taxonomical violence, appending them to a national category that they have resisted and a colonial imaginary that continues to brutalise them.

In the exhibition, a selection of Moro weapons from the Pitt Rivers collection are liberated from museum storage for the first time since accession. The exhibition display is an encounter that speaks to past and present accounts of dispossession. Each blade and its accompanying sheath are laid onto colourful woven fabric, made by hands of women who bear the legacy of the Moro struggle in Mindanao.

Outside of the Philippines, little is known about the siege of Marawi in 2017, when the national government under then President Rodrigo Duterte, aided by the American military, rained bombs on the north-western Mindanao city of Marawi in a quest to capture a militant group affiliated with the Islamic State (IS). The five-month conflict levelled the entire city and devastated hundreds of thousands of lives. Sinagtala is a community of weavers built on the ashes of this under-reported war. Established by Jamela Alindogan, an Al Jazeera journalist covering the siege, Sinagtala (‘starlight’ in English) served as a way for displaced women to find solace in the act of weaving. They wove as the bombs fell, the jagged motif on the traditional inaul fabric represent the tremors that reverberated around the women.23 Amid the inhumanity of war, the loom became their site of refuge, their grief woven ferociously into colour and pattern.

(opposite) Kris from the Philippines, with wavy blade, silver mounted hilt and wooden pommel.

Length: 697mm. Donated in 1911. © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1911.1.51

(following spread) Knife from the Philippines, with single-edged oval/leaf shaped blade. Length: 594mm. Loaned in 1918. © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1918.59.5.1

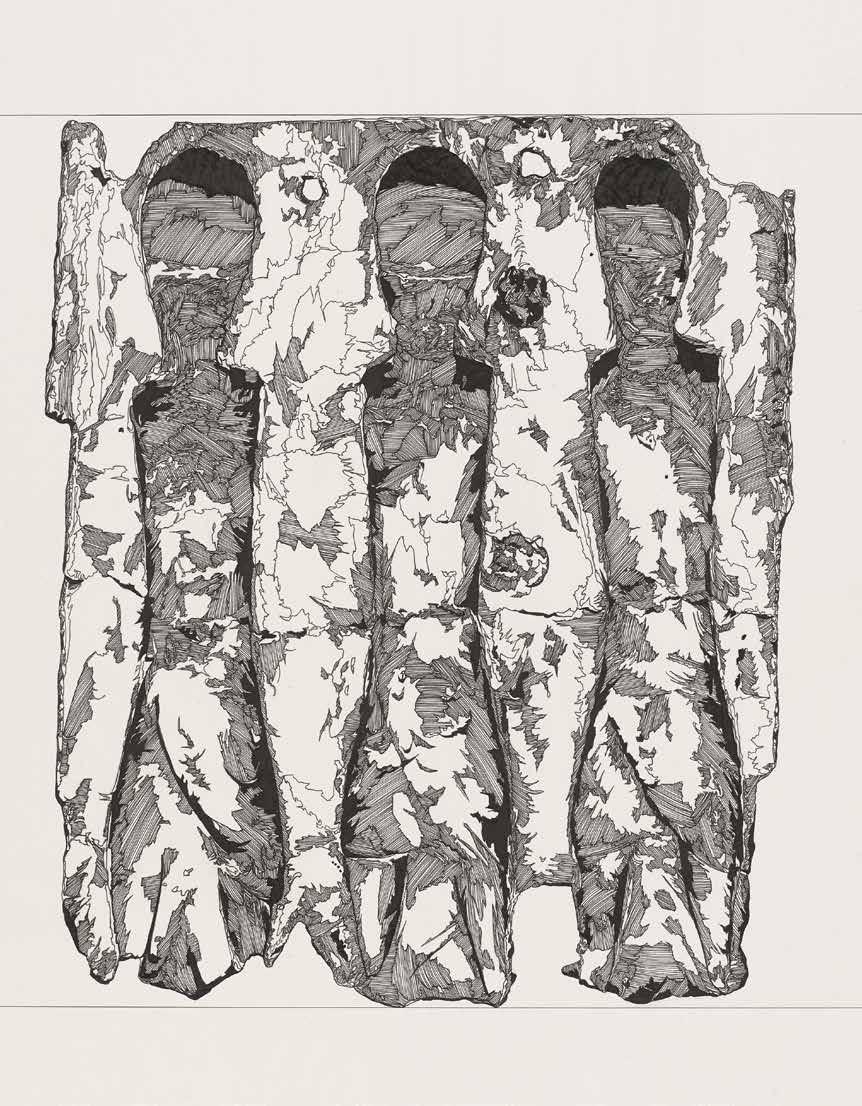

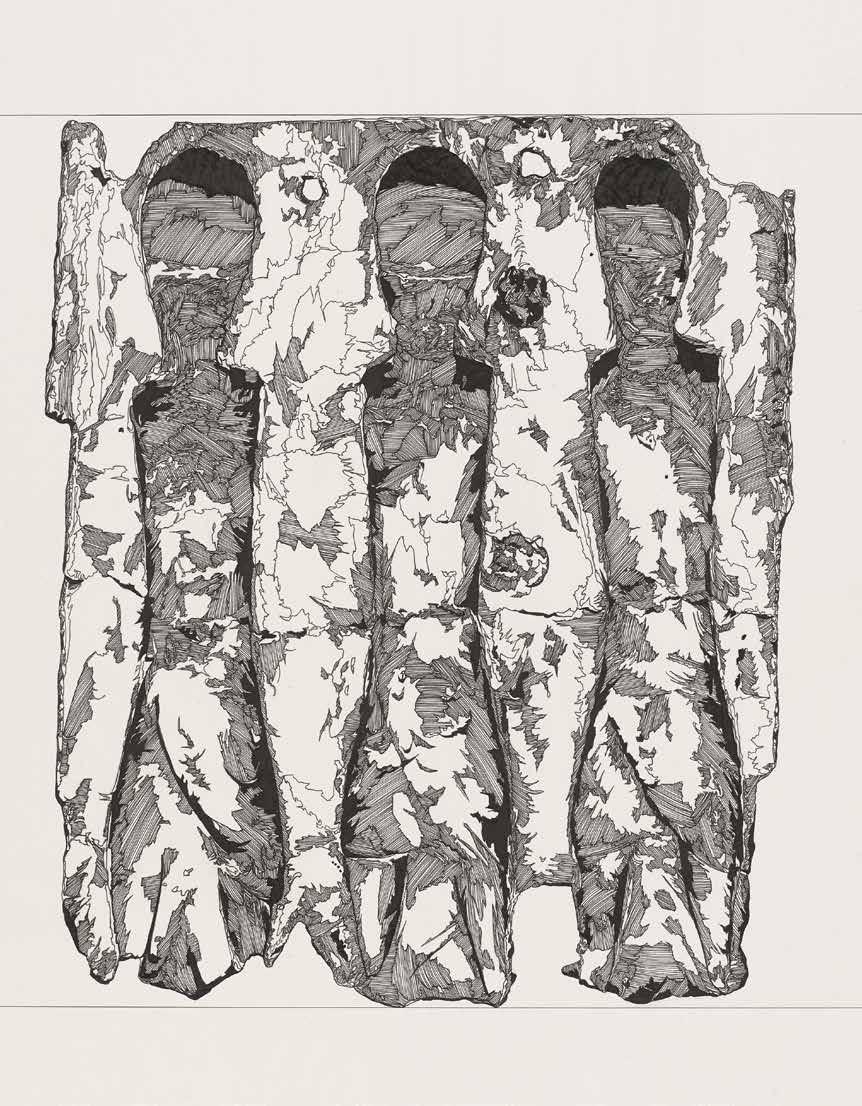

1897.76.36.18.6, 2023. India ink and screenprint on heritage woodfree paper, 1016 x 686 mm. © Pio

Courtesy the artist

1897.76.36.18.6, 2023.

India ink and screenprint on heritage woodfree paper, 1016 x 686 mm. © Pio

Vera Mey

The title of Pio Abad’s exhibition, ‘To Those Sitting in Darkness’, acts as a direct mode of address. It operates as a sincere extension of a hand, by the artist, towards a neglected human presence within the museum landscape – not unlike Abad’s tattooed arm depicted on marble in his new artwork Giolo’s Lament. This human presence is often represented as an object within an ethnographic museum collection, yet seldom imagined as its civilising audience member. Through careful research, Abad has excavated material from the dark enclaves of the University of Oxford collections, bringing to light objects and histories that command us to think about the entanglements across various colonised contexts. There is an ongoing demand for museums to reform as places that accept their complicity in the creation of knowledge through often questionable legacies. Yet despite aspirations to create an open space of and for many cultures, shedding the biases and baggage of the past, the legacy of collecting histories and classification systems continue to weigh heavily on historical collections, formed well before the role of the artist assigned to intervene within them.

With ‘To Those Sitting in Darkness’, Abad has created a call and response between objects. His own artworks sit alongside a selection of material from the Ashmolean collection and can be read as a form of, what decolonial theorist Walter Mignolo has called, ‘epistemic disobedience’ within the landscape of ‘the exhibitionary complex.’25 Here I also examine Abad’s exhibition through the framework of what Nicholas Mirzoeff describes as ‘the right to look’, an action inherently linked to hierarchies of power and surveillance,26 but which also has on its inverse a ‘right to be seen’.27 Mirzoeff argues that power is made to appear self-evident through techniques of classification, separation, and aestheticisation. Museums – through their

Ashmolean NOW: Pio Abad

10 February to 8 September 2024

Copyright © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, 2024

Pio Abad, Lena Fritsch and Vera Mey have asserted their moral rights to be identified as the authors of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-910807-60-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Catalogue designed by Ocky Murray Printed and bound in Wales by Gomer Press

For further details of Ashmolean titles please visit: www.ashmolean.org/shop

Exhibition Supported by:

Ampersand Foundation

Christian Levett

Mercedes U. Zobel

The Patrons of the Ashmolean Museum and those who wish to remain anonymous

All works by Pio Abad are on loan courtesy of the artist.

We thank Pio Abad for his deep engagement and remarkable collaboration.