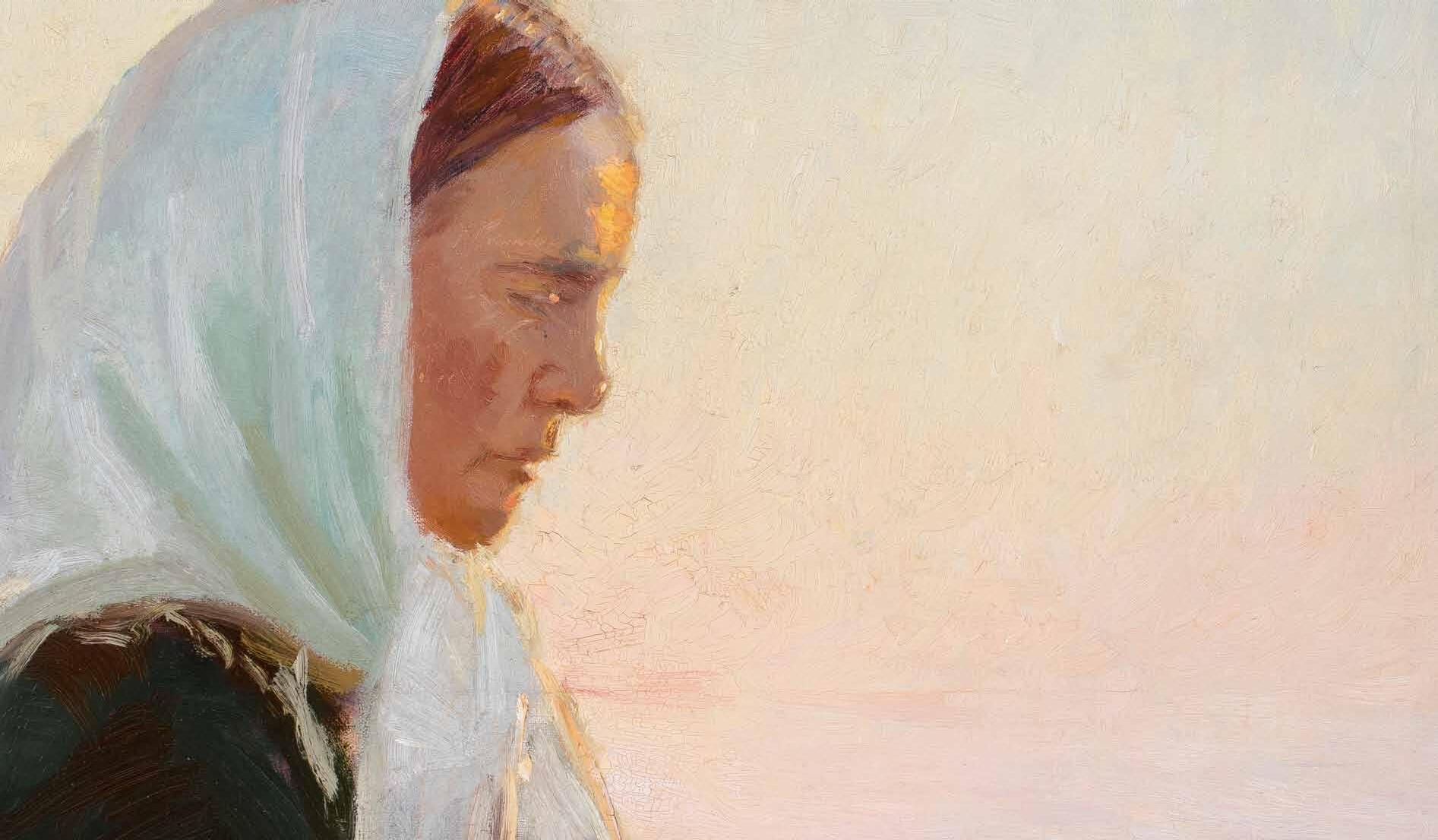

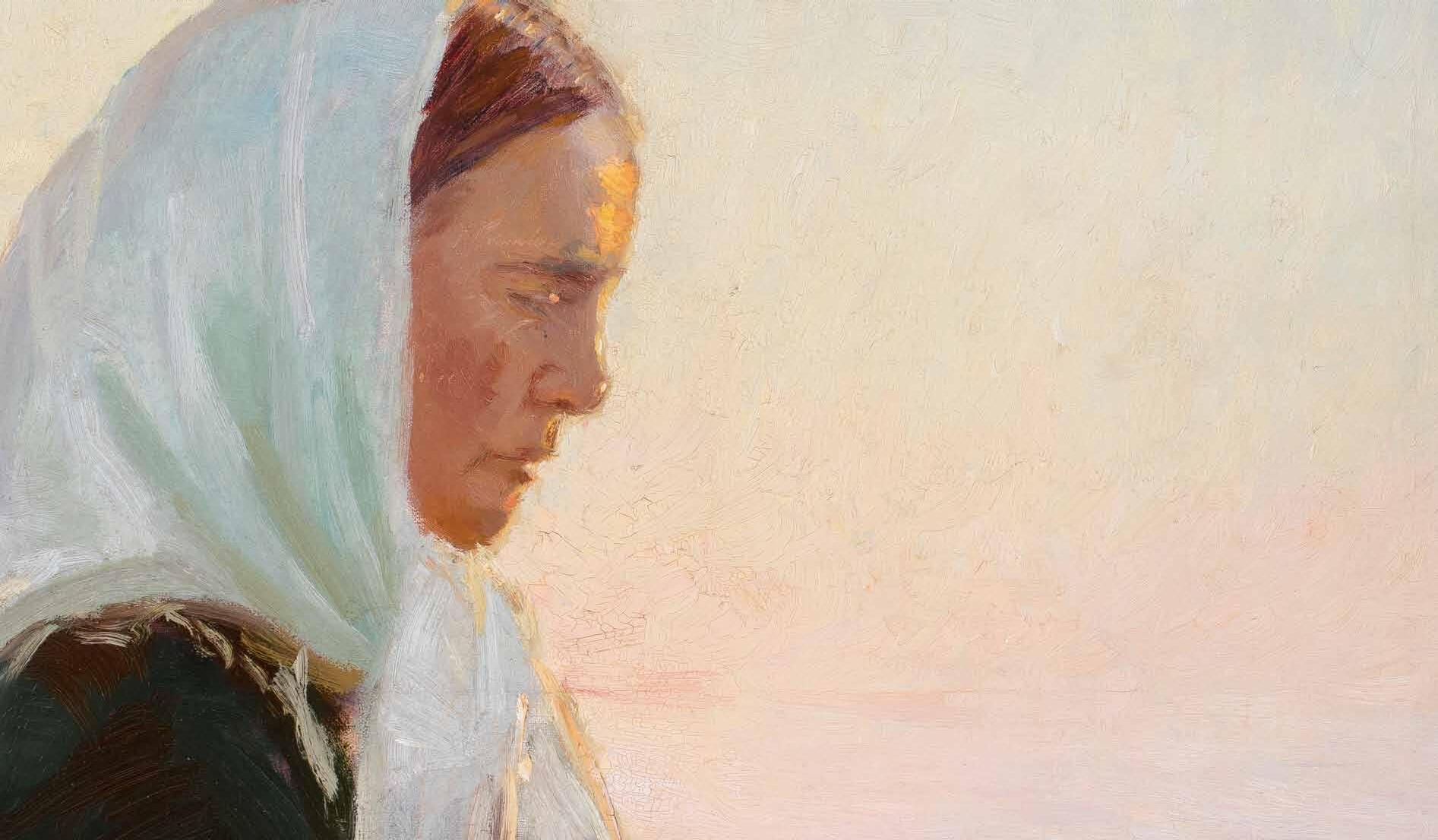

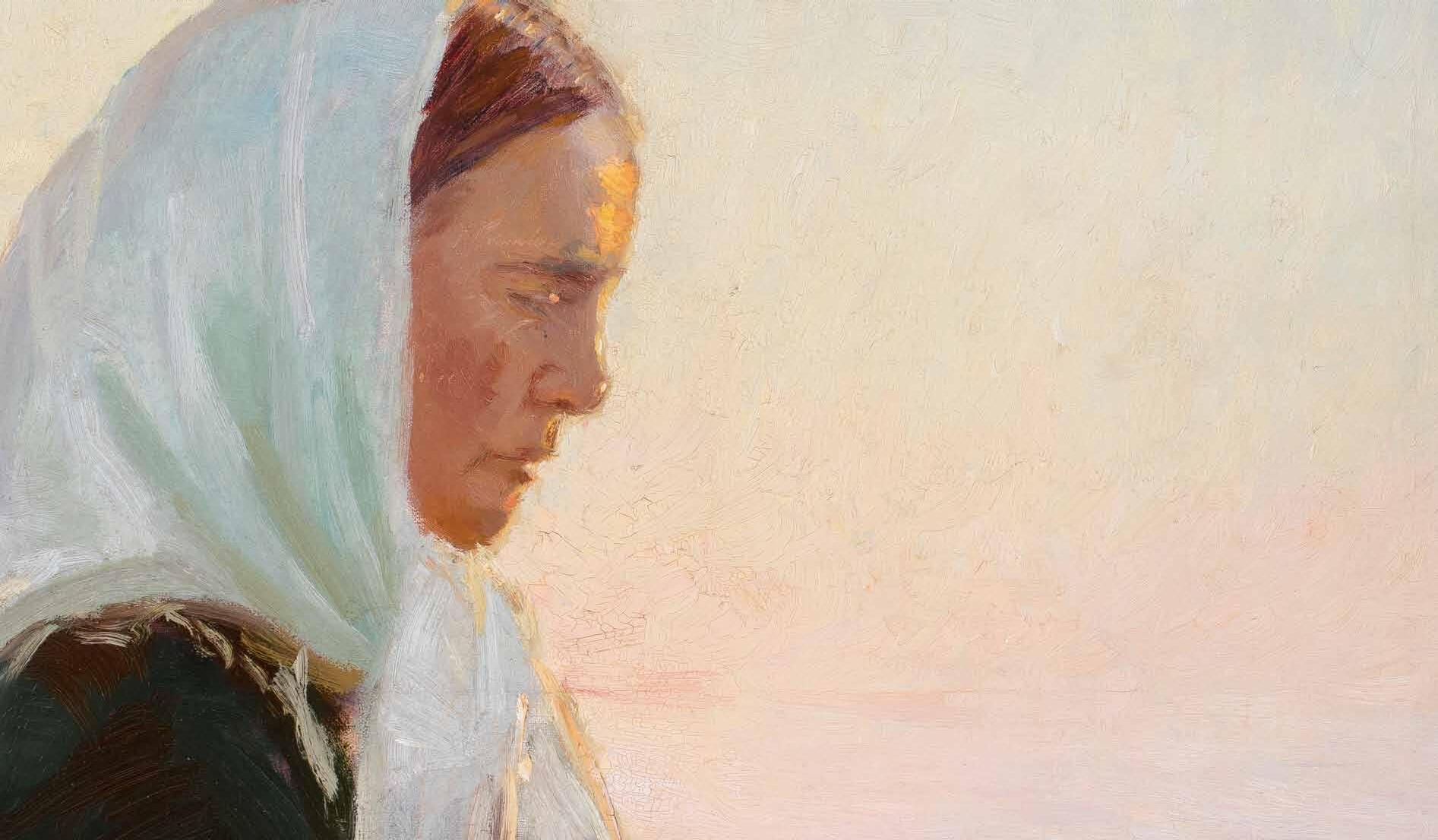

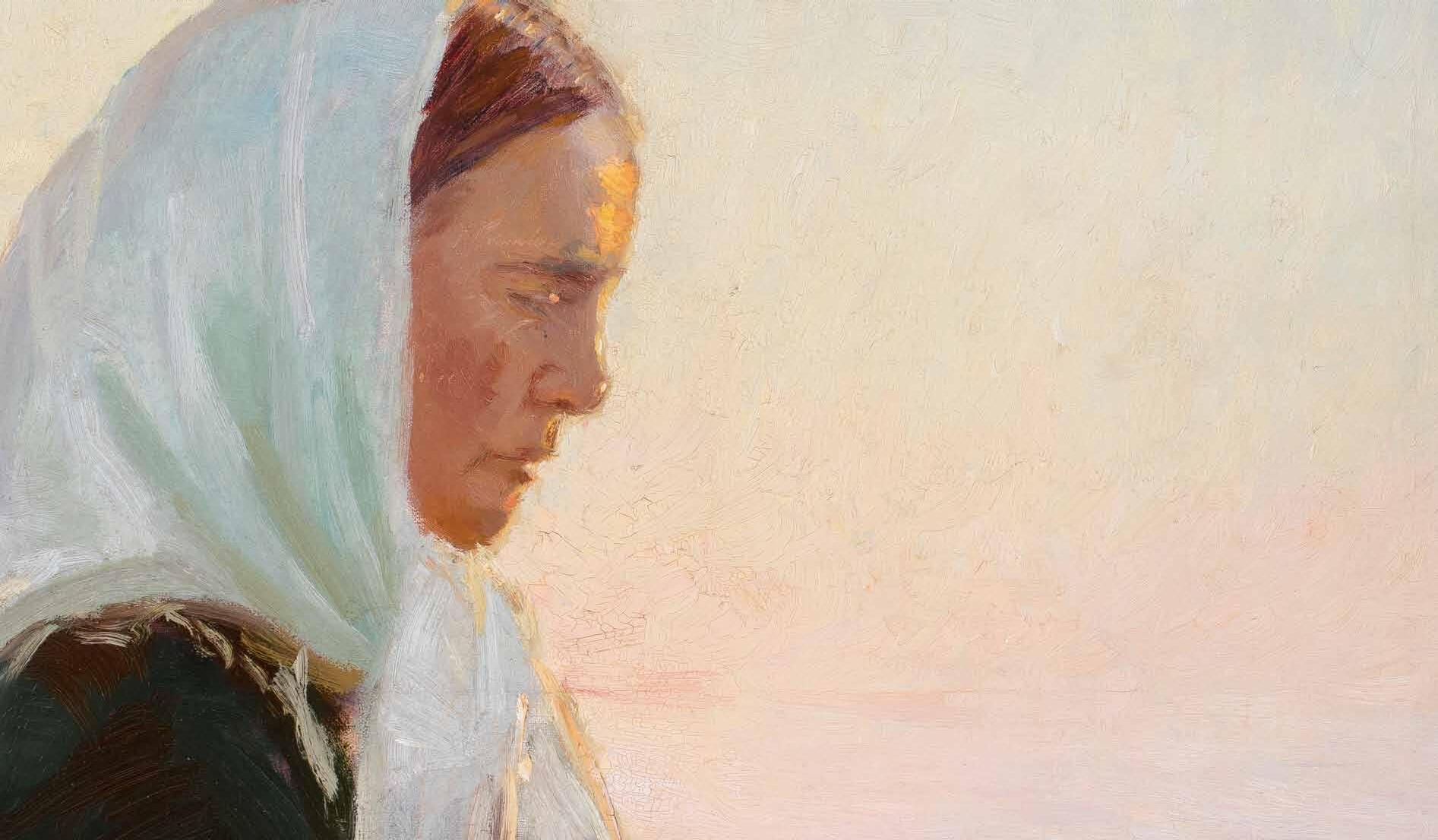

Religious themes were a relatively rare subject in the work of the Skagen artists, and Ancher was one of the few artists to consider such themes within her work.15 It was perhaps her upbringing that gave her the impetus, and the confidence, to tackle such subjects. Balancing her artistic and spiritual values cannot have been an easy task. Grief [cat. 34] can be interpreted as Ancher questioning her religious beliefs, illustrating the confrontation between tradition and modernity.16 The younger, naked woman, tormented and in pain, faces a representative of the older generation, her black attire symbolic of her piety and religious conservatism. Produced at the turn of the twentieth century, Grief is one of Ancher’s most provocative works. In it, she makes visible her internal struggle as a modern artist coming to terms with the context and the values with which she was raised.

Home Is a Radical Place

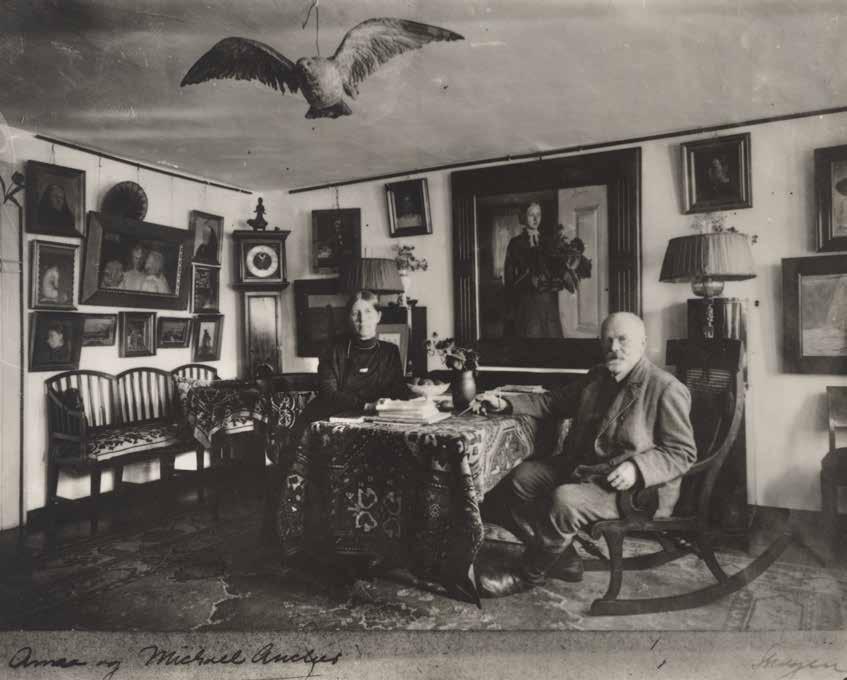

Throughout her career, Ancher concentrated on depicting the sights and settings familiar to her. Her family and friends were frequently the subject of her work, as was her own home [fig. 19]. As a result, previous generations of art historians have sometimes devalued her work, framing it within categories of ‘domestic’ and ‘feminine’ in contrast to the large-scale narrative paintings of her male peers. Such a view overlooks Ancher’s multi-figure compositions, such as A Field Sermon, and also fails to observe Ancher’s innate capacity for experimentation. It was precisely because she concentrated on subjects that were familiar to her, that she could pursue more radical approaches to the depiction of everyday life.17 Far from being ‘safe’, in the work of Ancher we see home as a radical place.

If we are to consider the Skagen colony as a sort of social and artistic experiment – one which provided the opportunity for artists to pursue the purest form of naturalism, by allowing artists to live and work amongst their subjects – then Ancher was its ideal agent. As the only member native to the town, she had known many of her sitters since childhood and could thus claim a different relationship with them. While she did not share their working-class background – as the daughter of local hotel owners, she would have been considered middle class –her family was well known and respected. Unlike other artists of the group, many of whom were from Copenhagen, Ancher could also speak and understand the heavily accented Danish dialect characteristic of rural Jutland.18

There are certain subjects that Ancher repeats within her work. Such repetition suggests that such scenes were part of everyday life in Skagen but, in reusing these themes, Ancher also had a sort of ‘scientific control’ for experimenting with different artistic approaches. In this regard, she operated in a similar manner to Claude Monet (1840–1926) who had produced works in series, depicting the same subject at different times of day, or under changing atmospheric conditions. This method allowed her to concentrate on a narrow range of effects, sometimes with only slight variation between works.19 Women Plucking Chickens [cat. 38] and Plucking the Geese [cat. 39] provide an illustration of this practice. Both works are in horizontal format, each showing a group plucking birds, collecting the feathers in baskets. Made just two years apart, they demonstrate a clear difference of approach. In Women Plucking Chickens, the earlier of the two works, she adopts a darker, richer palette, with a greater focus on the contrast