Preface: A Family of Collectors

Klaus KirchheimThe Carpet Collector’s Passion

In the late 1960s my father, E. Heinrich Kirchheim, surprised my mother, Waltraut, with a rather bulky present. On his return home from a business trip to Tehran, his luggage contained a silk Qum carpet measuring about 2 by 4 metres. A graduate in fashion design, my mother was an expert on textiles as well as textile designs and colours, so my father was sure that it would give her pleasure too. She examined the piece, and her experienced eye discerned that, although hand knotted, it was made with synthetic dyes and machine-spun materials; so it was not quite worth its price. Even though their pleasure was somewhat diminished by this realisation, the carpet nevertheless took pride of place as an everyday item in our living-room. From then on, my parents began to think about rugs that might be even more beautiful and decorative. Over time, these thoughts and conversations developed into a passion for old Anatolian and Caucasian rugs.

These textiles held such fascination for both my mother and father because natural dyes had been used to make them, producing colours of incomparable intensity; because they had been hand-knotted, often over many generations; and their designs reflected just that. My parents took particular delight in the thought that family histories were being told, sometimes spanning several generations. This was one of the reasons why they preferred such authentic tribal rugs to the carpets commissioned by royal houses. The seed of a collection had been planted. Thanks to their enthusiasm as a collector couple, this collection grew within a short space of time to become one of the most important of its kind.

Aside from the pleasure my parents took in these beautiful pieces and their history, it gave them special joy to share this pleasure with others. Based on a mutual interest, they developed friendships which sometimes lasted a lifetime. Particularly worthy of mention are their friendships with Jacqueline and Michael Franses, Friedrich Spuhler and William Robinson, as well as Esther and Jürg Rageth, Ingrid and Franz Sailer and, last but not least, Christa and Detlef Maltzahn.

It was only when my father’s collecting focus shifted towards ever-more fragmented pieces and the increasingly scientific study they received that this shared passion diverged into different paths, since my mother continued to be fascinated primarily by designs and craftsmanship.

As their children, how did my sister Christiane and I perceive our parents’ collecting passion? In the first instance, it was instructive: I remember an event from my school days. In a mathematics lesson, I had just been taught that a straight line is the shortest path between two points. Back home I decided to make use of this insight. As I always had a good appetite when arriving home from school, I wanted to get from the front door to the kitchen in the briefest possible time, so I used my newly gained knowledge by walking from the door straight there. Having taken just a couple of steps on a carpet, I was stopped rather vociferously by my father. He explained that my shoes carried dust from the street which would destroy the carpets in our house. He asked me to make my way along the small strips of floor left bare between the carpets. When I remarked that a straight line was the shortest path between two points, my father replied somewhat indignantly that it was a good thing

I had paid attention in school, but that this kind of mathematics did not apply in our home.

Attentive readers will have noted at this point that for us children the carpet collection was not always associated with happy thoughts. Their shared passion for Caucasian and Anatolian rugs allowed my parents to spend much of their time together. Sadly, however, they did not have the opportunity to share this passion with us.

Educational Olive Trees

In the early 1980s, my parents bought a gorgeous house on the Côte d‘Azur. When they were designing the garden, their eye was caught by an impressive, gnarled, obviously ancient olive tree in the plant nursery. It was over 1,000 years old and, having ceased to bear fruit, had been dug up from its original site in Spain and taken to France, where it was now for sale. All our family immediately fell in love with this monument. The tree was purchased and planted in our garden, where it thrived.

Bearing in mind the collecting gene inherent in our family, it is then not surprising that this one olive tree very quickly grew into a considerable quantity. Nor is it surprising that this hobby, which the whole family engaged in across the generations, is still being pursued by Christiane and me today, even though regrettably the house on the Côte d‘Azur has been sold. My sister now has a younger olive tree on the patio of her Stuttgart apartment. She harvests and pickles its fruits every year and enjoys them later with her children and our mother. Ten years ago we planted a 450-year-old olive tree imported from Spain in the garden of our house in Hanover. We give it love and care, protect it in winter and, together with our children, enjoy it and the memories it brings.

Insignificant collecting objects though they may be compared with the carpets, the olive trees have taught our family that a mutual collecting passion immensely adds to the joy shared by a family.

Lessons Learned: The Vintage Cars

My children, Felicitas and Maximilian, have been enthusiastic about two- and four-wheeled motor vehicles from an early age. In light of this it is hardly surprising that they were easily inspired by my pleasure in vintage cars. On the occasion of his A-levels, Maximilian was given a 1971 BMW 2002 convertible, a model of which only 200 were built. For her A-levels, Felicitas received a 1967 BMW 1600ti, a model of which only seventeen cars still existed in Germany in the late 1990s. Both our children and my wife, Martina, have gone on to buy further vintage vehicles. In this way our family has jointly created a collection of rare BMW vehicles that is highly rated by experts. Many a time have we come together to discuss purchases and sales, changes in collectors’ focus and special cars; many a time have we rediscovered vehicles that we had all thought lost; many a time have we worked together on the cars; and many a time have we gone out together on rallies. Lessons learned. A collection that inspires enthusiasm in a whole family tremendously enhances enjoyment of the collection – and the family.

Orient Stars Four Decades Later: The Metropolitan Museum Loans

Walter B. DennyIn January 1994 the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and Daniel Walker, who was at that time in charge of the Department of Islamic Art, arranged with the Kirchheim Collection for the long-term loan of six carpets to the Met. All of them had been exhibited in Hamburg in 1993 and were included in Orient Stars; they are among the forty-three that were chosen to be republished in this volume. Up to the time of the closing of the Islamic Art galleries for the major renovations that took place during the years 2006–2011, the Orient Stars loans were exhibited as part of regular rotations in the museum’s galleries.

While the Metropolitan’s collection is counted among world’s richest, especially in the realm of early Mughal and Safavid carpets, in the area of early Anatolian weaving its holdings were, and continue to be, notably less complete. With the acquisition of the Cagan animal carpet (fig. 2) under Walker’s curatorship in 1990, the museum took a major step to remedy this weakness, and in subsequent years a few other early Anatolian carpets have further enriched the museum’s collection in this area.

Four of the six Orient Stars carpets loaned to the Met in 1994 may be considered ‘fragmentary carpets’ rather than ‘carpet fragments’ – the notion of what constitutes exhibitable carpet material, including Anatolian tribal or village production of both great antiquity and fragmentary condition, has changed dramatically over the past half-century. Thanks to Walker’s initiative, the early Orient Stars carpets were exhibited in various gallery rotations from 1994 to 2006, alongside other carpet masterpieces from the Met collection, in the gallery devoted to the arts of the Ottoman Empire. The labels for the carpets were short, and largely ignored the text entries that accompanied their publication in Orient Stars

The task of writing about these carpets today, almost four decades after their original publication, presents both an opportunity and challenges. The opportunity is to approach these works not in an exclusively carpet-centered context, but rather from the broader and more holistic perspective of an art historian familiar with the full spectrum of the documents, history, art and architecture of Anatolia during this period.

The major challenges are two: first, over the past forty years the ways scholars see and interpret these carpets have changed substantially; second, even within the present moment, interpretations of the meanings of the forms and motifs of these carpets may still vary widely. A new perspective on several of these carpets, published as this essay was being written, illustrates this very challenge: it appeared in HALI (206, pp. 52–61), in an article by my long-time friend and colleague Michael Franses, titled ‘Fabulous Creatures’.

Writers about early Anatolian carpets may be broadly divided into two groups: those who posit anthropomorphic and zoomorphic – human and animal –origins for many of the forms we see; and those who prefer a more conservative view of these forms as in the main either originating in the geometry of the medium, or reflecting vegetal or, at a minimum, non-figural origins.

My own predilection aligns with the latter group, and from this viewpoint I find many of the catalogue entries in Orient Stars, which describe motifs as human and animal forms, or the stylised descendants of such forms, to be at best unconvincing and at worst profoundly disturbing. I believe scepticism on

The Kirchheim Gifts to the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin

Anna BeselinToday, the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin includes a small number of carpets and fragments that were donated by Heinrich Kirchheim because they either related to, or were part of, carpets already in Berlin.

Ever since the exhibition ‘Orient Stars: Eine Teppichsammlung’ in Hamburg in 1993, 34 a unique, brilliant-yellow 17th-century carpet (fig. 3) has been known to a wider public.35 Although in fragmented condition, its length of over three metres still makes it an eye-catcher. In 1998, together with two small associated border fragments (fig. 4), it was donated to the museum by Heinrich Kirchheim.

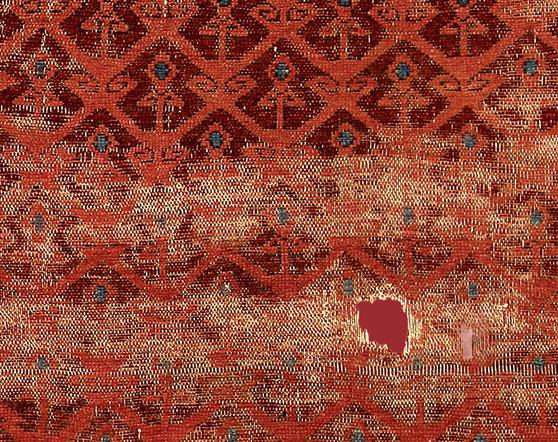

Its bold, almost massive motifs invariably attract attention. The scholarly appraisal of the piece in the Orient Stars catalogue that accompanied the Hamburg exhibition has drawn similar interest. Michael Franses divided the yellow-ground carpet and some 100 further examples into sub-groups and, based on technique, for the first time assigned them to Khorasan, an area which in the 17th century corresponded to the tri-border region of eastern Iran, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan.36 His ground-breaking essay remains to this day the basis for all further discussions.

The Museum of Islamic Art is now in the fortunate position of owning two representatives of the so-called Khorasan lattice carpets, namely rugs with a field structured by a large diamond lattice. The second is a blue-ground example, the largest part of which was donated by Wilhelm von Bode in 1906 (figs 6, 7). 37 This fact is all the more significant if we bear in mind that only seven carpets (mostly fragmented or fragments) of this Khorasan sub-group are currently known. 38 What is it that makes the yellow-ground Kirchheim carpet so interesting? Can we still unlock its secrets after so many years?

A direct comparison of the two Berlin pieces provides a striking illustration of both their similarities and their differences. Most of these have been discussed in the literature and will be mentioned only briefly below.39 We will focus on the details. Although experience has shown that close examination tends to raise further questions, it does provide answers too: answers which help bring us closer to the mystery of these rugs and their great allure.

All the Khorasan lattice rugs share the same composition: narrow, vertical diamonds are aligned in horizontal rows, slightly overlapping one another to form new, smaller diamonds. A further, offset horizontal row adjoins the diamonds above and below. The vertical points of the narrow diamonds meet the points of the smaller diamonds in the preceding row. A lattice is thus created. All the points and the sides of the large diamonds are studded with highly diverse blossoms. The main lattice is complemented by an underlying, similarly offset lattice system of thin vines. It is embellished with smaller blossoms and leaves.40 The repeat of this basic structure is determined by the height of one large diamond and two small, halved diamonds, as well as the width of one large diamond minus one small diamond, and can be continued into infinity in all the lattice rugs.41 The mirror axis of the repeat runs horizontally across the small diamonds.42

The main lattice of the yellow-ground fragment is woven in red and brown; the outlines are reversed accordingly, and the inner lines (stems) are either blue or red. The constant changes in colour, slight misalignment of the diamond sides and the fact that none of the large diamonds is completely preserved make the

Notes on the Early History of Rug Making

Michael FransesKnotted-pile carpets have an amazing history spanning thousands of years. As one studies their designs and weaving techniques one uncovers more about the peoples that wove them, about their lives and what sustained them, their cultures and their religions. All of this is reflected in the colours employed in their weavings, the patterns they chose and the symbols they adopted.

The earliest phases of rug making in Anatolia are not recorded, but evidence of weaving from circa 30,000 BCE has been found in nearby Georgia, in Dzudzuana Cave, based on mud impressions and basket-making. 96 Also discovered were dyed flax fibres with a colour range including yellow, red, blue, violet, black, brown, green and khaki. One of the threads was twisted, and several had been spun. The ends of the fibres show evidence of having been deliberately cut. 97 Whether or not some sort of patterned woollen tapestries or rugs survived from early Anatolian villages such as Catalhoyuk from 9,000 years ago remains unproven. While there are sceptics who believe this is nonsense, I prefer to retain an open mind. On my first visit to Catalhoyuk, together with Anna Beselin, we were informed that samples of animal fibres remain there, although we did not get the opportunity to examine them.

Elizabeth Wayland Barber, the renowned scholar of ancient weaving, informs us that around 7,000 years ago in Mesopotamia sheep were being bred especially for their wool, whereas previously they had been used just for meat. In 1993, she wrote that:

… the first direct proof of weaving in the Old World occurs around 7000 BCE at a site called Jarmo, in the Kurdish foothills of northeast Iraq … Our first preserved textiles from a dry cave in Israel’s Judaean desert, about 6500 BCE, are all made of linen. Our next find of cloth, at Çatal Hüyük [near Konya] in Turkey, dates to about 6000 BCE … The people of Çatal Hüyük were highly skilled. They wove narrow tapes as well as wide cloths, they knew how to reinforce selvedges, they rolled and sewed cut edges, and they knew how to tie knotted fringes. They wove coarse cloths and fine ones, as well as tight weaves and loose, lacy ones. Considerable confusion has arisen because the excavators published these textiles as being woollen before actually testing them. They assumed the cloths must be wool because they had found sheep bones at the site and no flax seed. But careful chemical testing later (by Michael Ryder) showed the fabrics to be linen, just like those from the Judean desert, apparently woven flax collected in the wild. 98

Igor Khlopin relates the possible evidence of pile carpets found in 1972 in Kara-Kala in Turkmenistan from 3,000–3,500 years ago. Stone spinning wheels as well as knitting and sewing needles were found. The most convincing evidence was the discovery of many carpet-shearing blades. Erich Schmidt found other carpet blades made at about the same time in Tepe Hissar, Iran. 99 When carpets were first studied by art historians 130 years ago, it was believed that the oldest survivors dated from about 600 years ago, their age being assessed by comparison with similar examples depicted in European paintings. For the history of carpet making before around the 14th century, there were only legends and sparse documentary references. What was reputedly the

The Historical Context

Carpets from Anatolia constitute the core of this publication: just under seventy of the seventy-five examples presented, spanning a period of some 700 years from circa 1050–1750. The only comparable holdings of this size and quality survive in the museums in Istanbul; this is the most significant and historically important collection of its kind outside of Turkey today.

The carpets represent a very good cross-section of the art of the tribal peoples of Anatolia from the time of the first migrations of Turkic peoples into this region until the 18th century. By the middle of that century, many of the small family groups who for centuries had woven knotted-pile carpets for their own use had gradually settled into village life, with some making rugs commercially.

The history of these family groups has been insufficiently studied; their movements within Anatolia and their role in society are left unaddressed mainly due to a lack of written source material. It is not a new idea that the history of nomadic communities has suffered on account of a readiness (on the part of both contemporaneous sources and later historians) to ascribe to them a two-dimensional role as the enemies of settled economy and culture.135

A certain bias also comes to bear in carpet scholarship in the form of the supposition that the best carpets could have been woven only in settled, ‘village’ communities, and within a commercial context. By looking again at the historical context of Turkmen nomads in Anatolia from their arrival up to the 18th century, new possibilities emerge regarding the production of carpets in this period.

The Pastures of Anatolia

The pastures of Anatolia afford perfect conditions for grazing sheep. Nomadic sheep-rearing tribes have inhabited Anatolia for the past 4,000 years. Marcus Tullius Cicero, Roman Governor of the Anatolian province of Cilicia from 51–49 bce, wrote that there were ‘permanent nomadic groups near Antalya’ and that ‘the Phrygian, Pisidian and Cilician herders, [migrated] through the flatlands in the summer and winter… rearing animals.’136

From 1048 onwards, in the wake of the Seljuk conquest, clans of Oguz Turkmen arrived from the mountainous Caucasus and the desert oases of modern Turkmenistan to feed their flocks on the abundant grasslands.137 The lure of the pastures was not the only cause of this migration. These centuries saw successive invasions, the destruction of settlements, and the intermittent lack of coordinated governance, especially in eastern Anatolia. The Mongol incursions of the mid-13th century precipitated a westward movement of the Turkmen people, as did the subsequent invasion of Anatolia by Timur in the 15th century. These events were followed by the fractured period of beylik rule (numerous individual principalities governed by a local bey or lord) before the establishment of Ottoman hegemony, itself not without periods of disruption.

Eastern Anatolia was for a long time a ‘frontier’ zone. The Ottomans later managed this situation by employing Turkmen soldiers as akinji warriors to patrol the ever-changing border regions. They were unsalaried by the state, supporting themselves by raiding villages and plundering. It is important that the Turkmen pastoralists who brought their weaving traditions with them to Anatolia in this period be placed within this context: uncertainty, mercenaries, lawlessness and a swiftly changing map.

Anatolian Tribal Rugs 1050–1750: The Orient Stars Collection and Some Related Examples

Michael FransesIntroduction

Anatolian rugs such as those illustrated in this volume are often referred to as ‘village’ rugs. However, I believe it is more likely that most if not all of the carpets made in central and eastern Anatolia from before circa 1550 were produced by nomadic tribes, probably small family groups who migrated between seasonal pasturelands, with no regard for any notional boundaries that the authorities may have wished to impose. Although the Ottomans began to settle the Turkmen nomads of western Anatolia into towns and villages from the 1380s onwards, it was not until the mid-16th century that they made a concerted effort to settle some of the tribal groups in central and eastern Anatolia. Even then, many nomads were extremely reluctant to change their traditional way of life, and as late as the 1960s small rug-making tribal groups were still wandering across Anatolia.

The purpose of the present publication is to attempt to place the Orient Stars Collection’s Anatolian tribal rugs from circa 1050–1750 into some artistic and historical context. In the absence of any pre-existing reference books on the subject, and given the limited research that has been carried out to date, to do true justice to such a project would require an intense and dedicated study over many years and need to draw upon and illustrate most of the surviving examples in public and private collections all over the world.

Although it was not my plan to write a volume on Anatolian tribal rugs, I had promised Heinrich Kirchheim that I would fulfil his wishes and publish a volume of the masterpieces that he and Waltraut had assembled. Initially, I started to write simple catalogue entries for each rug, but soon realised that it was essential to place each example in context through extensive notes and illustrations of comparative examples, thereby to facilitate the appreciation and understanding of this important private collection. This book will add to the body of published material and, most important of all, hopefully encourage younger enthusiasts to travel widely to see and study in person a large number of surviving examples, keeping an open mind before putting pen to paper.

One can only fully understand a work of art through the physical examination of as many related examples as possible. To locate and study the approximately 3,500 known Anatolian rugs woven between the 11th and 18th centuries would be a long and fascinating project. To date there have not been any exhibitions of Anatolian tribal rugs focused on specific groups, thus allowing one to see closely related examples side-by-side. Nor has a serious book yet been written on Anatolian tribal rugs from before 1800, by an author who has physically examined enough surviving examples and is sufficiently familiar with the subject to be able to sort this body of material into clusters based on tribal groups.

But few people have the time or means to travel that would allow in-depth study of rugs in collections all over the world. Not many authors have had the opportunity to examine all or even some of the works they write about. For the most part, they have studied the patterns from illustrations and have relied on previous publications, whose authors may also not have seen the actual works. Contributors to a wide variety of websites, auction catalogues and reports often list related examples, but in many cases their observations suggest that they have not had the opportunity physically to examine the items they discuss.

Fig. 20 Map of the beyliks (principalities) of Anatolia during the 15th century.

Fig. 21 The Ala’eddin Mosque Diamond Lattice Carpet. Probably Konya region, central Anatolia, circa 1200–1300 (14C 1290–1420). One of three sections, 226 x 123 cm, wool pile on a wool foundation. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, inv. no. 683a.

Fig. 22 The Ala’eddin Mosque Diamond Lattice Carpet with Kufic Border. Probably Konya region, central Anatolia, circa 1200–1300 (14C 1250–1400). 294 x 512 cm, incomplete, wool pile on a wool foundation. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, inv. no. 681.

Fig. 23 The Ala’eddin Mosque Flowers and Stars Lattice Carpet. Probably Konya region, central Anatolia, circa 1200–1300 (14C 1390–1480). 243 x 333 cm, incomplete, wool pile on a wool foundation. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, inv. no. 685.

I will not, however, delve too deeply into the iconography here, or attempt to identify the creatures definitively, but merely comment that the highly schematic style of drawing suggests that they were the result of a long development, and that much earlier representations may well exist, on textiles, silver, stone or other media. Images of simurghs tend to be curvilinear and ‘naturalistic’; and I am unaware of depictions in other media of creatures within creatures, which I am sure must be significant. In some of the earliest carpets that have survived – such as the Pazyryk – the creatures also tend to be fairly naturalistic in their drawing, and such abstraction as can be seen in these animal carpets may have taken a long time to evolve. The creatures probably thus represent the end of a design tradition rather than the beginning of one. Plate 8 might have the oldest rendering of the same creature that is rendered di erently on the other carpets, but alternatively it might represent a di erent beast. If the former is the case, then careful examination of it might shed some light upon the species of the creatures on the other four. Both animals on the Orient Stars rug, the blue one in the foreground and the yellow one in the background, appear to resemble stylised versions of dromedaries, with their single humps, long, gira e-like necks and shortish legs. The two levels of pattern di erentiate this example from the other members of this group, as well as the fine proportional spacing between the borders.

I would contend that all these early Animal carpets found in Tibet are from Anatolia. There is nothing to prove this – apart from their similarity, both in their symmetrical knotting and in the wool and colours they employ, to other carpets made in Anatolia, and their di erences to carpets assumed to have been made elsewhere. One of the most fascinating things about this group of rugs is that, although they were made in the period after the Mongol departure from Anatolia, they show elements within the patterning that link to Mongol art and little that relates to Turkmen rug design.

The discovery of 13th- and 14th-century Anatolian carpets in Tibet raises many questions. How, for instance, could they have travelled more than 5,000 kilometres? It is possible that they were transported eastwards from Anatolia during the time of the Pax Mongolica. This lasted from around 1203, when Genghis Khan set up trading posts every fifty kilometres along the roads across his empire, eventually linking the Pacific to Anatolia, until 1331 when the spread of the plague more or less permanently shut the route down.

If we assume that the four earlier rugs all arrived in Tibet together, then how did the Cagan – with a similar pattern, and made in a tribal group not too far from the others but perhaps fifty to seventy-five years later – also reach there? One possible explanation is that all five carpets arrived in Tibet at the same time, but four were already old at this stage, and the Cagan had been made shortly before shipment. A further question is, what was so special about these rugs that people wanted to transport them such an incredible distance?

It is not as if rugs were not being made in India, Persia, Afghanistan and China at this time. Knotted-pile carpets had been made locally in western China since around 1350 BCE, if not long before.

The Marby Confronting Birds and Tree Rug (fig. 41) is one of the most iconic of all rugs. It is similar in colours and wools to later examples identified as

Fig. 38 The Birth of St Thomas Aquinas (detail), circa 1470. Agnolo degli Erri and Bartolomeo degli Erri. Tempera on panel, 44 x 32.7 cm. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, inv. no. 1871.41.

Fig. 39 The Fustat-Nahmann Dragon and Phoenix Rug. Possibly Konya region, central Anatolia, circa 1300–1400 (14C 1326–1442). 48 x 66 cm, section, wool pile on a wool foundation. Bruschettini Collection, Genoa.

Fig. 38 The Birth of St Thomas Aquinas (detail), circa 1470. Agnolo degli Erri and Bartolomeo degli Erri. Tempera on panel, 44 x 32.7 cm. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, inv. no. 1871.41.

Fig. 39 The Fustat-Nahmann Dragon and Phoenix Rug. Possibly Konya region, central Anatolia, circa 1300–1400 (14C 1326–1442). 48 x 66 cm, section, wool pile on a wool foundation. Bruschettini Collection, Genoa.

Compositions and Motifs Depicted by European Artists

During the period covered by this collection, circa 1050–1750, many thousands of Anatolian carpets were exported from Turkey to Europe and Central Asia. Those that reached Europe were highly valued and over the past 600 years numerous European artists have depicted them in their work. In some cases they might have been used simply because they were available, perhaps as studio props. However, the inclusion of Eastern rugs in some secular paintings represented wealth and status, while in religious works they might have been used to indicate the oriental environment of the Holy Family.

A number of these artists studied carpets particularly carefully, and it is likely that they made preliminarily sketches (although remarkably few have survived), as often the smallest details are portrayed with exceptional accuracy. Many artists clearly admired and were fascinated by carpets; some might have collected for themselves, others portrayed rugs that belonged to the sitter, and others simply copied examples from earlier paintings.

It should be noted again that carpets coming from the East may not have been newly made and it is highly unlikely that commercial workshops were set up there to produce carpets specifically for export until well into the 17th century. What is more probable is that both new and old carpets were available in bazaars, where they were acquired and shipped overseas to places like Venice for resale. Thus, many of the carpets in paintings may well have been old when they were portrayed. There are Italian artists of the 16th and 17th centuries who certainly depicted rugs made more than a century earlier.249

One of the first books to be published on carpets was Alt Orientalische Teppichmuster nach Bildern und Originalen des XV.–XVI. Jahrhunderts by Julius Lessing, the inaugural director of the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin, in 1877.250 Lessing, an eminent scholar and prolific author, believed that the decorative arts and the crafts in a multitude of media were often the work of inspired but unknown ‘artists’. Like his contemporaries Alois Riegl and Owen Jones,251 he was fascinated by pattern and ornament, and explored their history and development over the centuries. He wrote about the designs of oriental carpets and made particular reference to their depictions in European paintings.

Art historians have devised various methods of labelling unknown artists and unsigned works of art in order to be able to identify and discuss them with clarity. When Wilhelm von Bode wrote about carpets, he chose to label them with the name of their then-owner.252 The modified current practice of naming some carpets after their first-known owner can be useful for identifying individual works but does not cover the designs. It also became increasingly fashionable in the carpet literature to give names to the patterns on carpets, again for ease of identification, and one way of doing so was to label a specific composition or ornament after a European artist who depicted it. This did not mean that all the rugs with similar patterns were made in the same place, or at the same time, as that ornament was first depicted.

These labels (‘Lotto’, ‘Holbein’, ‘Ghirlandaio’, ‘Memling’, ‘Bellini’, and so on) became terms of convenience but, as they were never fully defined, they have often turned out to be more cumbersome – and confusing – than useful. For example, in 1929 and 1941 Kurt Erdmann used the term ‘Holbein’ extensively.253 In 1960, however, he wrote: ‘In rug literature [these groups] of geometrically patterned carpets of the early Ottoman period are still designated as “Holbein rugs” in deference to their incidence in paintings by the younger of the artists who bore that name. This is not only meaningless, but actually misleading for rugs of [these] groups had already appeared at a substantially earlier date in the paintings of other masters.’254