With the publication in early spring of Paffard Keatinge-Clay: Modern tect(ure)/Modern Master(s),1 this remark able figure’s work reemerged into awareness after thirty years of complete obscurity. The drama of its return the oeuvre’s dramatic finale: after flowering in San Francisco during heyday of the countercultural revolution,

spring 2006

Modern Archiremark into public complete return recalls after a brief during the revolution,

-

If disciplinary boundaries are mere speedbumps on the information superhighway, if the regime of flows washes away stable identity, if any kind of continuing conven tion is ignored in the culture of the NEW!—all of which are claimed somewhere today— then Architecture is probably in trouble. In fact, architecture does seem unusually unsure of its own status in a world

The literature on disciplinarity usually ties the idea of “the discipline” to education. For our purposes, though, the term will be reserved for the nature of that which is learned or taught, rather than the subject being taught or the teaching itself. As a verb, “discipline” connotes a less positive activity than

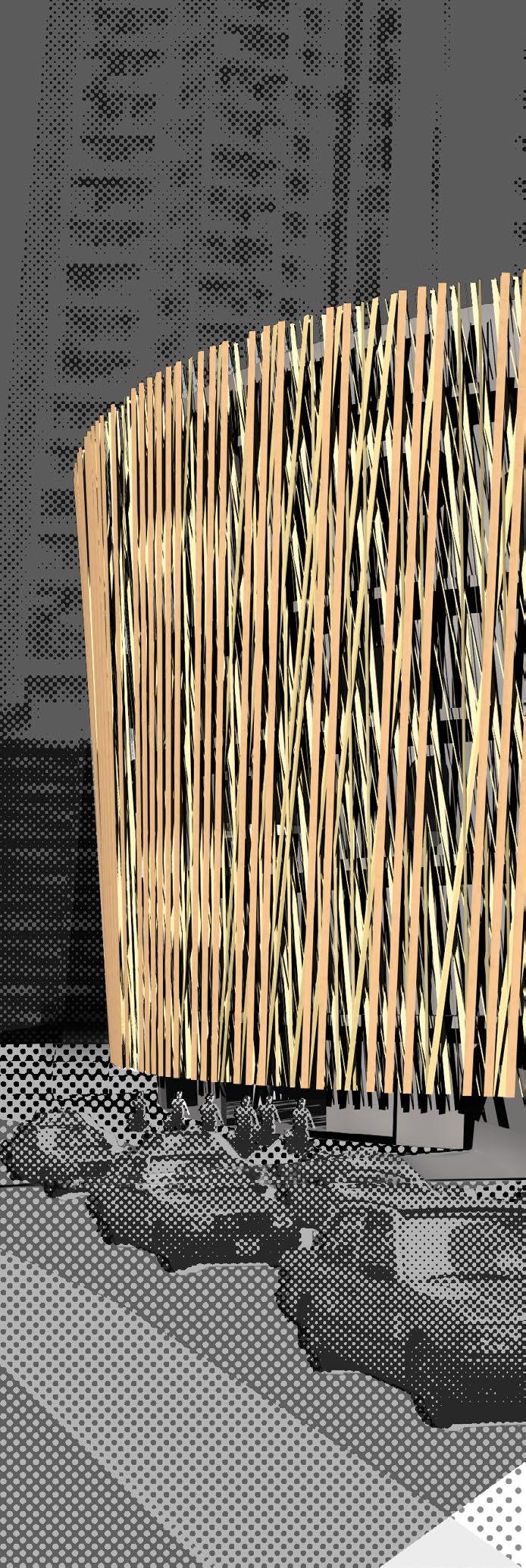

and wood as a statement of belief in the worthiness of its development, asserting that it is no cheap, fly-by-night developer special, but a real, quality building, intending to be around for awhile.

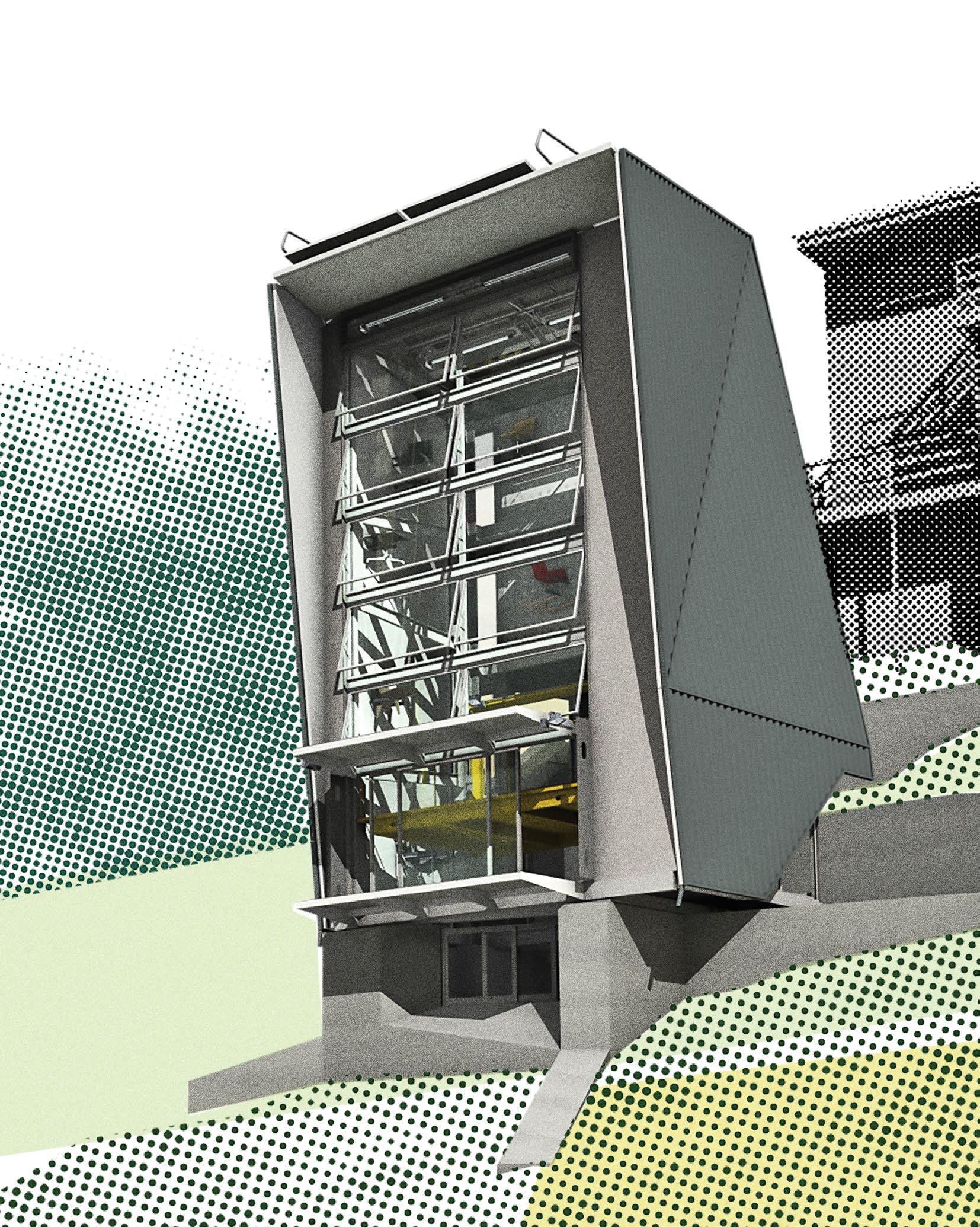

San Francisco and the Bay Area boasts a proud tradition of Modern architecture, the best examples of which were built in the sixties and seventies in the béton brut concrete system, by Paffard Keatinge-Clay, Luigi Nervi, Joseph Esherick, William Wurster, and others. In the present design this history is proudly recalled not only by the fact of its materiality but also by its form and massing, which exhibits the plasticity and dignified character particular to the material. Refusing to treat the concrete as merely a structural system to be covered up, the design instead emphasizes its unique, ever-changing surface quality, varying its handling from rough board-forming at its “rusticated” base to the smooth interior surfaces of steel formwork and plywoodformed exterior planes above. The honest durability of the material benefits both the owners and the community, ensuring a lasting sense of quality to the development, requiring little expensive or time-consuming maintenance, insulating neighbors from each other and the elements with effective sound control and environmentally friendly thermal mass.

Complementing the concrete is a façade system of dark anodized aluminum and painted steel storefront and mall-slidertype glazing. Wood sunscreen louvers and interior finishes add warmth without compromising the integrity of the whole, and in combination with the painted sidewalls of the unit’s integral outside decks, bring out noble historical associations reaching back to Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute and Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation.

This project is as much an urban design proposal as an architectural one. It takes its cues in this regard from the City’s General Plan goals to “reconstruct the physical fabric of the neighborhood” and “promote innovative urban infill

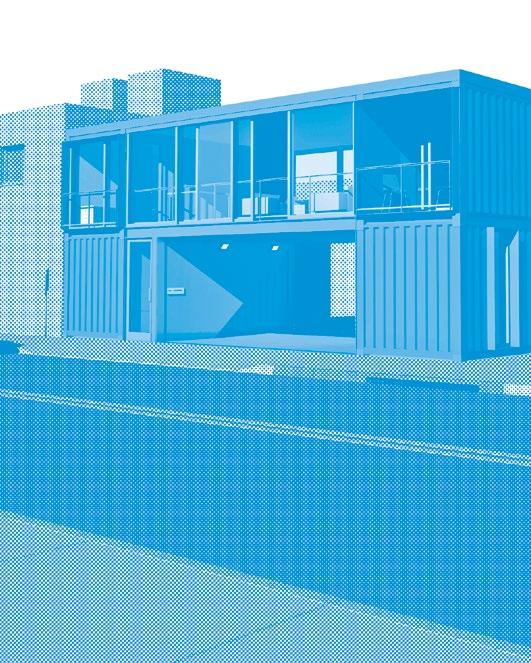

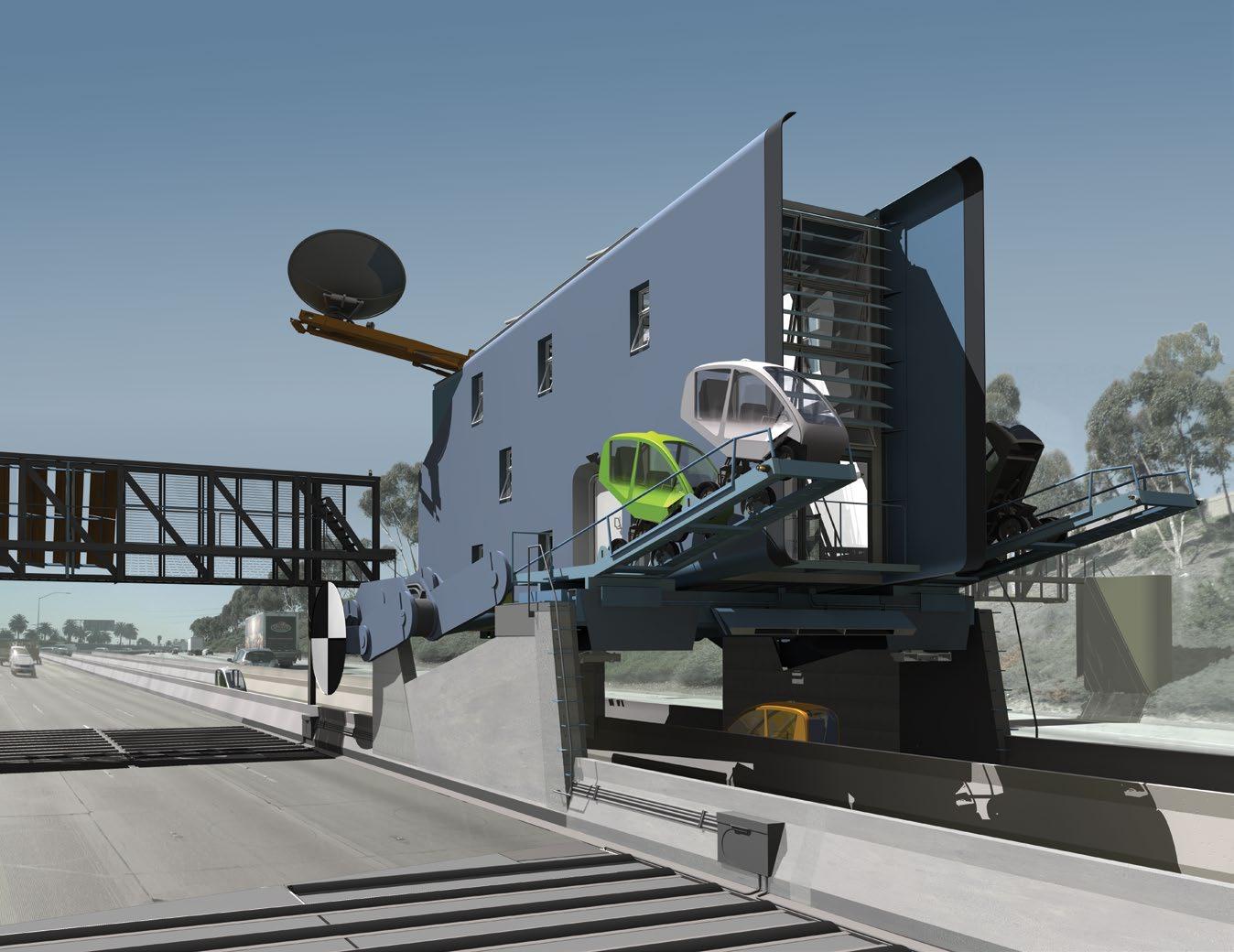

On a small parcel of vacant land at the corner of S. Alameda and Jackson in Carson, a new two-level structure will be built to house a small ornamental iron and cabinetry fabrication shop for the design/ build architecture practice of Jones, Partners: Architecture. Also included will be a caretaker’s residence in two modules, located on end trucks rolling along light gauge crane rails on the roof of the office/shop structure. The office/shop will be constructed of 8" CMU

Carson, CA

Program Fabrication shop and office for design/build architecture practice, with a caretaker’s residence

Size 4,300 sq. ft.

Completion January 2007

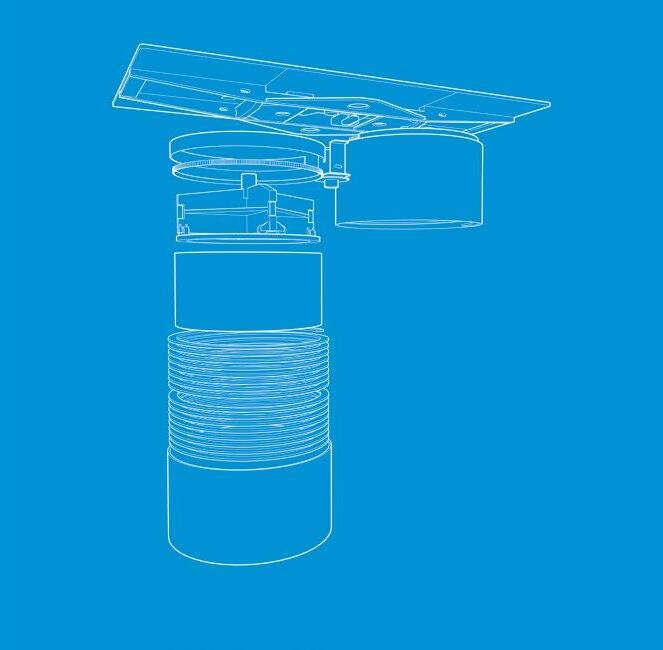

Materials + Systems CMU-bearing and glass curtain walls with sliding doors on lower level; steel-framed structure with corrugated metal cladding on end trucks and crane rails above. Steel beams, wood joists, and decking for the roof and mezzanine structure in the office/shop.

neither buildings nor breadboxes are ever more than marks on the horizon, farther or closer, and this inculcates a sort of pragmatic humility in the objects that ultimately makes them less aloof.

This modesty characterizes the object’s genesis within an environment of tinkering. Such design proceeds by solving problems rather than making statements; consequently style is seldom an issue. Refinements arrived at by tinkering are pragmatic and particular rather than theoretical and systemic. The individual customizations do not necessarily “add up” to anything other than their piece of the problem, and so the cumulative judgment necessary to achieve a sense of style is lacking. In the absence of the larger conversation, a bizarre and sometimes charming idiosyncrasy may develop, as with the work of Bruce Goff or, more recently, Greg Lynn; more often, though, the result is the straightforward reasonableness for which American design has been known, deriving from the lack of claims for more than the solution of a particular problem or the matter-of-fact mastery of a corresponding piece of the construction puzzle.

“How-to” TV shows are popular in America, including sitcoms with that theme ( Home Improvement ), and the reality TV trend has generated many shows that could be considered the tinkerer’s equivalent to Survivor: American Chopper, Monster Garage, Monster House, Junkyard Wars, Extreme Makeover Home Edition and Robot Wars Programs featuring objects also proliferate in the virtual space of the television set: Mega Structures, Modern Marvels, Building the Ultimate, Extreme Engineering and others celebrate big things doing big things, while spaces are featured as the subject of shows like World’s Best Implosions. Unlike Europe, which has a collective History peering over its shoulder, America has felt only the pressure of the Neilson box, the market and the creative challenge of a vast territory with harsh demands.

Underlying all of these symptoms of design difference between the two cultures is their fundamentally different rapport with technology. This factor was less apparent before globalization, or before the global cataclysm of WWII precipitated economic globalization, because technology itself varied around the world. Since WWII erased any entrenched differences among the allies or between the former combatants, encouraging cooperation among the former and wiping the slate clean for the latter, a consistent technology has insinuated itself into all aspects of life, making the variation in outlooks more obvious. In America, where the prevailing attitude toward the machine was always more or less one of trust and companionship, the postwar spread of technology was not alarming; technology was equipment, its presence in the home as labor saving devices, central air and family entertainment was welcomed. In Europe, on the other hand, the war metastasized a historically more hesitant relationship with technology into fear or awe. Heidegger’s early (prewar) respect for “equipment” in

bearing walls along Alameda and the alley that parallels it behind the lot, with glass curtain wall and sliding doors interspersed on the Alameda façade and Jackson Street façades, while the caretakers residence is a steel frame structure with corrugated metal cladding. The roof and mezzanine level structure in the office/ shop will be steel beams

and celebratory of technical considerations). Where curves are introduced at the Student Union, they are far from free: the hyperbolic surfaces at the base of the building, explained as light scoops, betray their greater interest in geometric rigor by the mathematical precision of their shapes and by the uniformity of those shapes around the building despite the variation in their orientation to the sun.

While the Student Union may stand as the highpoint of the oeuvre, a masterpiece at least equal to the achievements of those it emulates, it seems there is still work to be done: the pyramids do not penetrate the plinth/base, nor do they manifest interior conditions in themselves suitable to their spectacular geometry and structural bravado. While the resolution of their meeting with the base is complete and satisfying as viewed from without, handled with the same sophistication as the rest of the composition, it remains just that—a compositional effect, without significance for the disposition of the interior or integration with the triangulated structure below (which seems inspired by the geometry of the pyramids in the first place). In fact, as if in some perverse, final affirmation of the pavilion/rooftop type, the pyramids just sit on this base, like objects on a table. For someone who would claim structure as the foundation of his architectural sensibility, this obvious resignation (which Keatinge-Clay freely admits) before the structural conflicts in such an otherwise apparent structural tour de force, not to mention career milestone, is extraordinary. Something must be up here.

The mastery of the whole makes the viewer wish that the relationship of the pyramids to the base were more complete, with the pyramids not merely resting on top of the base, but rising from the ground, through the plinth and into the sky, committing the passing interaction of the two figures, the two systems, the two attitudes toward fixity and place, to a dialog rather than a self-satisfied, simple congruence. It seems so obvious. And yet, in analyzing all the topologically reasonable variations of such an integration,14 none can surpass the impaired actuality. Indeed, the exquisite tension evident in the built example slackens in the most “correct” alternatives.

Of course, the idea of a creative anxiety or productive irresolution like this does not seem so remarkable. Retrospectively considered, this possibility could explain much of what is otherwise anomalous in KeatingeClay’s projects, from the ill-defined plinth condition of the Mt. Tamalpais pavilion to the awkward lecture hall spring point at the San Francisco Art Institute. Overlaid across the implicit axes of Modernism’s architectural interest and character (structure, program, romance, pragmatism) is the grid of judgment (realization, invention, precedent, originality, mastery, innovation) to which Keatinge-Clay was perhaps more consciously attuned. Because his compulsion for ideality would not allow him to suffer such impurities willingly, they must be ascribed to inability, ignorance, or, as the pyramid problem suggests, intention.15 And each of these possibilities must be considered against that grid of judgment. In the previous anomalous cases, the conflicts were not resolved, and no innovation was forthcoming. In the present case, it is easy to imagine the Miesian angel on one shoulder shaking its head as the Corbusian devil on the other whispers in his ear, trying to talk him into greater outrageousness. With this final project, Keatinge-Clay demonstrated the mastery to ignore these voices and realize something that exceeded both.

Wes Jones is an architect practicing in Los Angeles who occasionally runs a studio at the GSD.

f or several years in Canada following his escape from San Francisco, where he focused exclusively on designing unremarkable but eminently pragmatic medical buildings, styling himself as an expert in this arcane specialty. According to Eric Keune in conversation, though, he left Canada under similar circumstances, this time in truly dramatic fashion, slipping away in the night onto a tramp steamer that eventually deposited him in North Africa, where he had previously taught as a visiting critic in Morocco. After this the trail becomes obscure until he shows up in Spain many years later.

will use Modernism and Modern architecture interchangeably here for convenience, since the issues discussed do not involve the distinctions usually attributable to the different terms.

1 / I B y Eric Keune; (Los Angeles: Southern California Institute of Architecture Press, 2006

12 / XII Keune, Jean Louis Cohen and Stanislaus von Moos, all writing in Keune, op. cit., see in the triangles the influence of Wright and remark on the relation, most likely uninformed, to Kahn. Keatinge-Clay, however, will admit in conversation only Buckminster Fuller as an inspiration

7 / VII J encks, Modern Movements in Architecture (Garden City, NY: Anchor, 1973), 32. The variables here were filled-in by prominent figures from almost every intellectual discipline at the time, giving versions as widely varied as book/painting/theater/art/ house is a machine for reading/moving us/acting/making art/living. Is the fact that only the architectural version survives today really evidence of the outrageousness of the formula’s application in this realm, as Jencks asserts, or of the recognition of a tantalizing element of truth?

8 / VIII K eune, 178.

13 / XIII D uring the analysis phase of the studio, the students made the analogy to Einstein’s theory of relativity: after the initial insight about the constancy of the speed of light, the rest of the theory unfolds logically without further elective invention. The working out of the theory is really the rigorous working out of the implications of that one insight. Yet because of the novelty of the original insight, each of the otherwise straightforward steps from that become tinged with its own novelty.

9 / IX T he ideas in the following treatment were the product of the studio’s analysis and discussions; the studio worked in groups to document and analyze most of the buildings mentioned here and the particular points raised in this paper must be understood as products of the studio’s joint efforts.

10 / X Paffard

14 / XIV This exercise was done by the students.

15 / XV In conversation, Keatinge-Clay admits that the anomalous Stonehenge-like cummerbund around the glazing at the Great Western Savings is simply a mistake: “I didn’t know what I was thinking.”

Keatinge-Clay’s recounting of Le Corbusier’s excited description of this discovery of the board-formed concrete finish on his return to the office—where the staff was already working on the Unité—is one of his better anecdotes. It shows how the master himself fit into the chain of “realization,” thereby legitimizing the practice for those who followed.

11 / XI At the risk of spoiling the drama of the story, Paffard Keatinge-Clay did in fact practice

2 / II Since much of the work was built in cast-in-place concrete, its physical survival was assured, but its anonymity has generally caused it to suffer a fate worse than demolition, i.e., the destructive renovation and rehabilitation (HistoPoMo frosting, for example) by later generations of less skilled architects unsympathetic or deaf to the original language.

3 / III All of the factual material in this tremendously compressed summary and in the following analysis is taken from lectures by Paffard Keatinge-Clay and conversations with him, as well as from Eric Keune’s book, the only published source for any biographical information. Also, discussions with Erik Keune, who has read KeatingeClay’s unpublished autobiography manuscript, have filled in places the book does not cover 4 / IV Keatinge-Clay gave the inaugural talk of the lecture series at the Harvard GSD in fall 2006. In addition, offered a studio during that fall semester, inspired by his work and the example it seems to offer of innovation from within the discipline, rather than exclusively through external appropriation. This article presents some of the conclusions of the research done by the studio’s students (Bryan Boyer, Kate Feather, Tomas Janka, Manuel Lam, Qiuda Lin, Ted Lin, Adriel Mesznik, Saverio Panata, Chris Parlato, Chris Talbot, Jeff Temple, Isik Neusser).

5 / V Keune, 179. 6 / VI

cies and non-profit organizations [for] relevance, responsiveness, [and] recognition, the strong architectural identity of our proposal is balanced by an urban sensitivity and nuanced openness to the community. Finally, to create a dynamic and comprehensive learning environment…of design theory and practice… nurturing creativity, independence, self-confidence, and free-thinking, our design presents an exciting variety of challenging spaces, guaranteed to stimulate the imagination, and a symbolic architectural presence that will generate pride. In addition to these goals provided by the mission statement, the design also recognizes the Institute’s vested interest in sustainability and in innovative development ideas that would optimize the opportunities in the area. In particular the scheme sees the latter as a mandate for a strong approach to the question of shared community facilities, proposing a vertical expansion program to preserve open space for recreation uses.

To accomplish these goals the present scheme strives for a balance between aesthetic and practical concerns— to be a model of good design—so that it may serve as an exemplar for the studies that will be pursued in its studios and laboratories. Accordingly, this scheme demonstrates how a strong form is made stronger by efficient functioning, how pragmatic issues can be elevated through honest expression, and how even the most fanciful ideas can be realized if pursued with rigor and dedication. It has both serious and lighthearted aspects, and the inherent flexibility to be either as required by the evolving pedagogy of the various programs that will call it home.

The competition brief addresses many issues of aesthetics and expressive form in relation to the Institute’s presence in the sensitive local residential context and associations to the student body. With respect to its urban

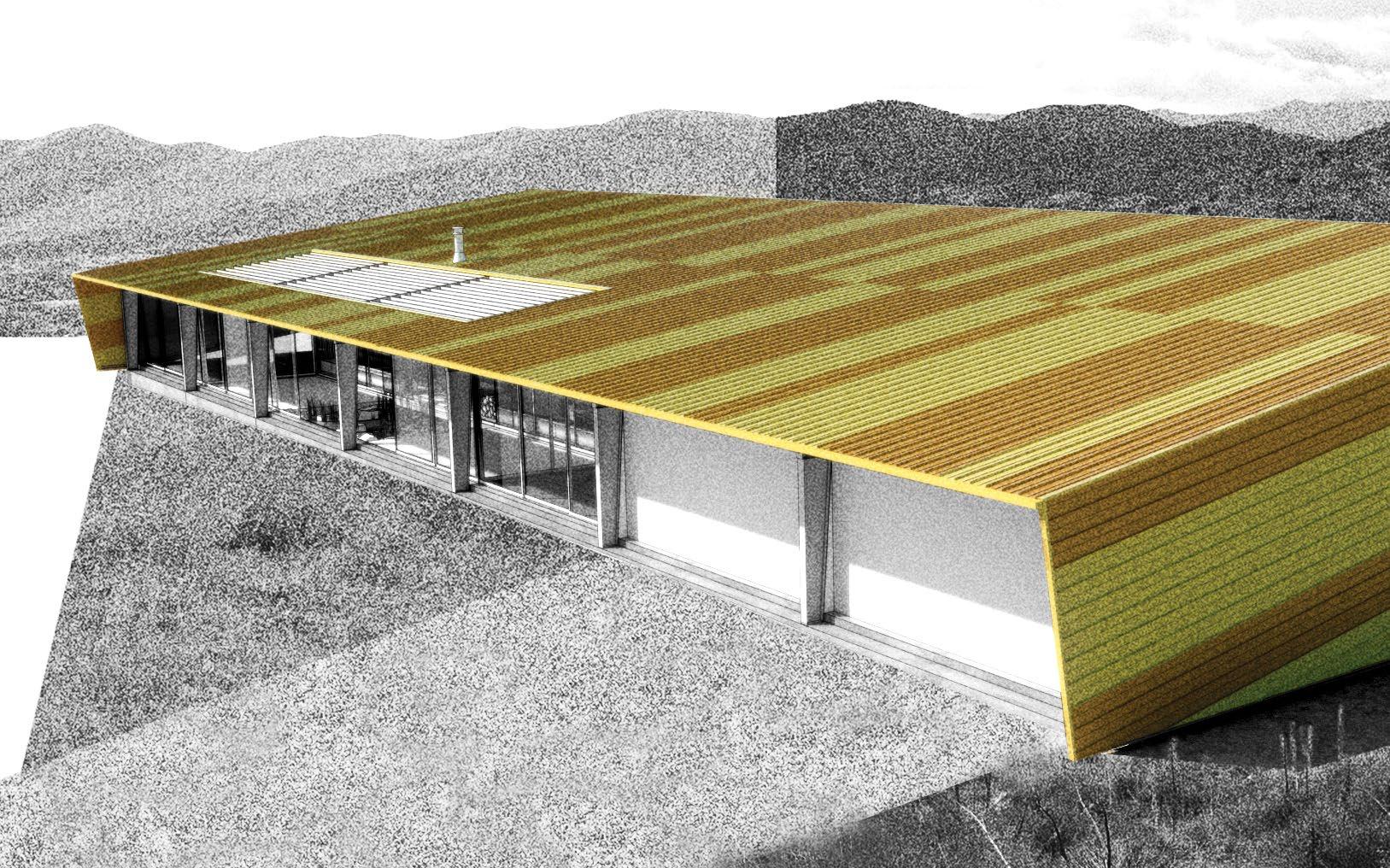

J,P:A was approached to design a retirement home and studio for a graphic designer and his artist wife on 80 acres, north of Los Angeles. Since this was for retirement, cost was a major consideration. The clients challenged the architects to use pre-engineered metal buildings as the basis of the design to save money. Unable to leave well enough alone, the architects ran off into left field with this idea, exploring the intentional misuse of the structural frame that is the heart of such preengineered products. The architects

Location Agua Dulce, CA

Program Single-family residence; a retirement home with a studio/workshop and detached out-buildings

Size 8,650 sq. ft., including barn and garage

Completion February 2007

Materials + Systems Pre-engineered metal building systems, including structure and cladding; thermal-pane sliding wall system, Type-V interior fit-out installed on concrete slab foundations

arbitrariness of the literary signifier, however. It is consumed by its intentionality, willfulness and determination.

Design: will

In the same way architecture is obliged to deal with its communicative aspect, so it must come to grips with the necessary intentionality behind that communication. When the designer must not only “write” the building, but also make up the “words,” or at least their spelling, such intentionality must be remarkable; it must suffuse the resulting work. Corbu’s anecdote in When the Cathedrals Were White captures the sense of this quality well: he describes slag heaps that he initially confused with manmade structures—his initial excitement at the purity of their forms giving way to disappointment as he realizes their shape is a product of natural laws rather than human intentionality (“after all, they are only piles of shale”)—and claims there is a difference between the affect their form has on the “mind” (understanding the natural law that dictates their angle of repose) and on the “heart” (feeling the human agency behind them, mistakenly in this case). The intentionality that sets design in motion is conserved in the resulting product as the quality of willfulness, which “touches the heart.”

A true live/work project, all

recognized that the structural properties would not be compromised in applications that respected the essential working-orientation of the steel bents, and so proposed a design based on the slightest variations of the bents themselves—tilting gestalt to the cladding—set off by the classic glazing-as-void move, in order to produce a restrained yet distinctive geometry that in no way recalls the clichéd inexpensiveness or industrial character of the building components.

The clarity of such effects must burden the designer with the responsibility to care about the reception of the design, to design in such a way that the product is beneficial beyond simply answering the need to build. But the willfulness attending this responsibility and the means of its discharge is not unproblematic. Willfulness in design has been criticized as repressive, as contrary to the openness it should encourage. Such criticism assumes that the willful design must force the user to relate to it in particular, predetermined ways. Since, as the source of the design, the designer is held to be the ultimate source of this repression, the possibility of removing the author has been advanced as a means of eliminating willfulness in the product. The point is that there is no such thing as free will in design. Not only is it constrained by the author’s history and experience (and thus subject to the conventions that must be repressive—Marx’s false needs or Lipton’s counterfeit nurturance), but it is also obligated to work within the bounds of the discipline (though it may appear to step outside these lines, the results will only be deemed architecture if the lines are redrawn—perhaps by those very efforts—to include those results). By such arguments even the intention to design non-deterministic, openended work must remain infected with the author’s subconscious allegiance to his own experience or desire to create an identifiable example of architecture.

This, at least, is the political argument behind parametric design, mapping, diagramming, continuous differentiation and mass-customization, and other related methods that strive to purge decisions that originate with an author from the design process, replacing them with parametric adjustments to user choices or indexing of contextual influences. Through such techniques some hidden

In plan this violation is even more egregious, as the mezzanine

Each chair of this version is constructed from a single piece of folded, laser cut, powdercoated aluminum sheet marked by the gender-affirming holes. This design does not support a normal, stable seated posture. Instead, only rocking horse and seesaw activities may be enjoyed. For the child attempting to sit quietly in this chair at a wee little desk, say, while tackling a coloring book, he or she will be frustrated by an inability to stay within the lines. This may occur to them as a metaphor later in life.

boy’s chair girl’s chair connection studs visual notch

The three Jones boys grew up spending summers in a small cabin near Lake Arrowhead and weekends there sledding in the winter before they became adept enough to accompany their parents to the local ski slopes. The cabin featured mounted deer heads and antlers, a swing mounted between

two huge fir trees, a very large collection of ancient National Geographic magazines where barebreasted women could be spied, a wooden deck on the downhill side of the cabin overlooking a small creek that offered endless hours of fun chasing floating sticks and creating dams. There was a fireplace where marshmallows could be tortured, daddy long-legs spiders in the bathtub, an attic dormitory bedroom with eight beds, a very large woodpile and chopping stump, with mallet and wedge,

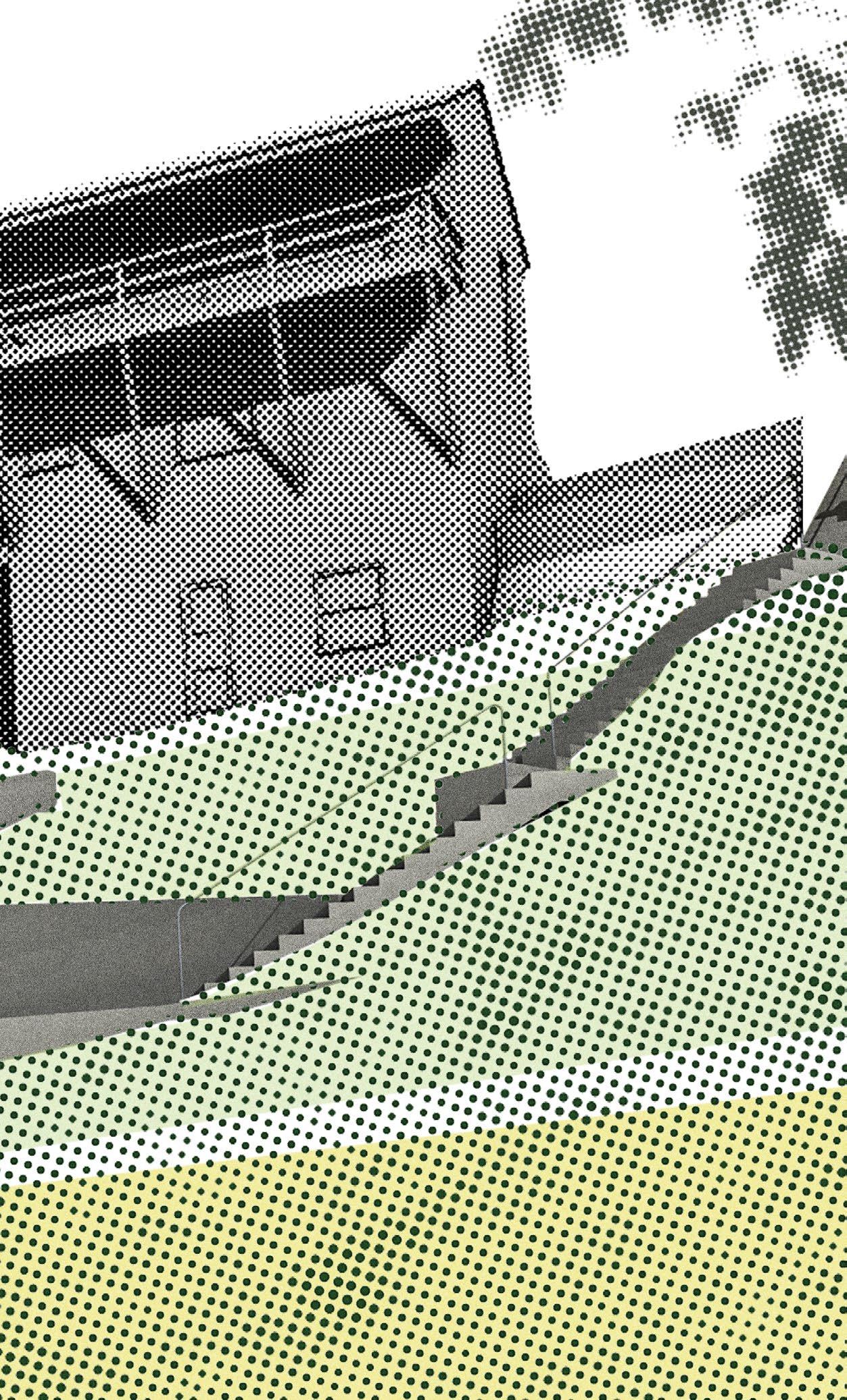

A small landslide in the downslope backyard of a bungalow in the Silver Lake hills is the occasion for this project; the necessary repair and stabilization of the damaged slope will require the construction of extensive new retaining walls that will become the foundation platform and lowest level of a new studio “towerino.”

Location Los Angeles, CA

Program

Completion January 2010

Materials

The design results from the relatively straightforward intersection of the competing opportunities and constraints on the site: the local planning rules limiting the size and programming of accessory buildings, exceptions for height allowance on a slope, the building code’s life / safety requirements, and the desires of the owner for living space where he could continuously “sample” his furniture collection.

generations of combative young architects determinedly pushed on to the unholy logical conclusion of objective measurement. Following those original trajectories, Dutch work came to it by way of sarcastic aloofness and the digital by blind ambition. Both were examples of conscious father-killing one-upmanship by the youth, yet in neither case did the youth realize that they were themselves well within the kill zone.

“Program” became an object of architectural interest before it found its computational apotheosis in Dutch work.5 An early token for Modernist functionalism, program truly became self-aware in Bernard Tschumi’s notions of “dis-programming, cross-programming, and trans-programming,” which applied the sort of collage techniques being used syntactically by Eisenman and the hard deconstructeurs to the semantic dimension. In such operations, and as adopted by Koolhaas, this “content” was handled at a remove, as the formal scrambling of the collaged elements and their associated programs facilitated the daring violations of programmatic “zoning” that charged such work with excitement. Not only was this practice formally critical, but, because the operations were applied to units of cultural activity, it also carried implicit social value as well. The fact that this value was the result of a cool diagrammatic automatism rather than hot liberal concern added the exquisite distance of irony, a necessary step to the ultimate estrangement of computation.

The irony manifest in the social predicaments manufactured by trans-programming spoiled any serious political interests of the deconstructive collage practices. Latent in this nascent ironic-euro-pragmatism—what eventually became “Dutch”—was an intellectually disarming drollery that was far more effective at stopping argument than the earnest rigor of the deconstructeurs. Humor, “the best medicine,” was also much better able to paper over the void where the faith-based value system of architectural necessity had been before the deconstructeurs had pulled back the curtain to reveal that in fact there was (by then) no man behind it to ignore. In contrast to the work of Archigram, which was merely funny, the “retroactive manifesto” Delirious New York and the bricolage practice of the theatrically anonymous “Office of Metropolitan Architecture” were “deeply” humorous.

Where Archigram spoke more to the culture than the discipline, architecture itself was the subject of Koolhaas’s jest. The pathos of the RCA Building catching the Chrysler Building in bed with the Empire State Building took the august institution of architecture down a few notches. By the time his Parc de la Villette scheme had given “cross-programming” its most radical and thus emblematic expression

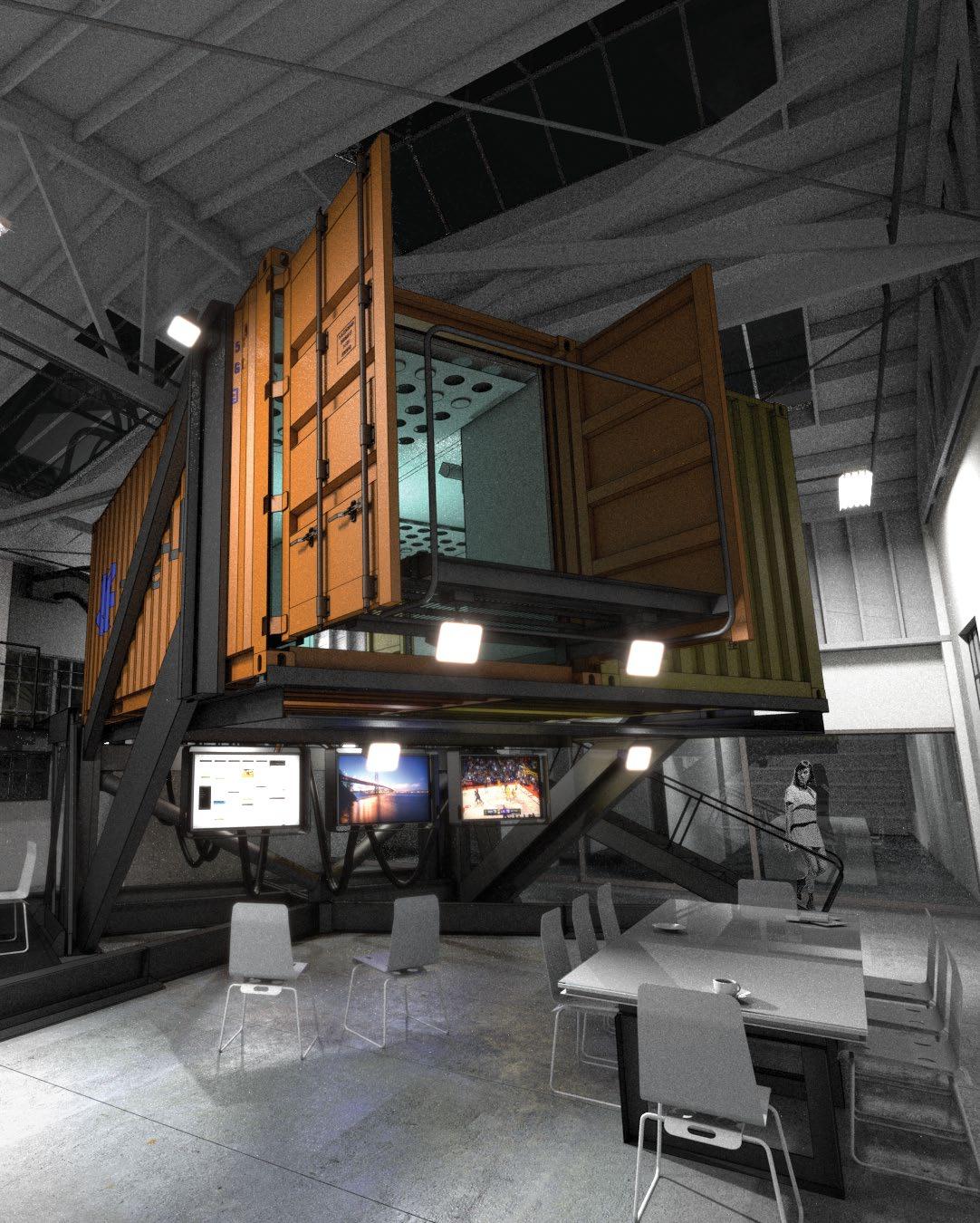

This feasibility study for the BSoA explored the use of containers for showers and toilet facilities at a major east coast Scout camp. This camp (‘The Summit’) hosts scout troops during summers and is the site for a major regional Jamboree held every four years. The client was interested in using these facilities as teaching tools as well as logistical support, in

Completion

particular making the Scouts more sensitive to their water usage and to help them understand the cycle of delivery and reuse as grey water.

In an unprecedented departure from adhering to the strictest tectonic conventions of the containers (orthogonal organization, connections at corner fittings only), the containers have been arranged for maximum, disciplined

efficacy and efficiency, which are of no concern to architecture when it is viewed as other than simple building or shelter. Something like faith—in the value of the effort, in the possibility of an outcome—must be involved. Architecture’s struggle with its own sense of worth, given its elective nature, has forced it to continuously raise the stakes in order to fend off the temptations of quantifiable, engineered certainty. However, the increasing sophistication of the technology available to supply this version of certainty has pushed architecture to the brink of abandoning its faith. In order to indulge a craving begun innocently enough so long ago, when the “eyes which do not see” were opened, architecture is on the verge of finding out what really happens when “form follows function.”

To Louis Sullivan, who first popularized that phrase, form and function were simply different sides of the same coin, but after Le Corbusier placed them aboard his planes, trains, and automobiles, the pair began a journey towards literalness that leads through Koolhaas and Eisenman to the present. Koolhaas stands for the functional side of Modernism, which saw architecture as a species of problem-solving, while Eisenman, despite the severity of his work, epitomizes its problem-transcending expression. The unity of the terms was assured by defining each through the other—expression as the face of function, function as the body of expression—while judging both according to a subjective sense of architectural necessity that could not derive from either alone. Functionalist problem-solving wanted to be appreciated rather than simply assessed, while expression was always asked to measure up. Whether their fissioning, so evident in the practices of Koolhaas and Eisenman, should be blamed on the culture-wide ascendancy of irony, or on the objectivity that backstops that irony, it set in motion today’s seismic division between authored and authorless (or willful and automatic) design, and attunement to either sense or sensation in appreciating that design. It remains to be seen if these are just forks in the road or the four point antlers of an impossible dilemma.

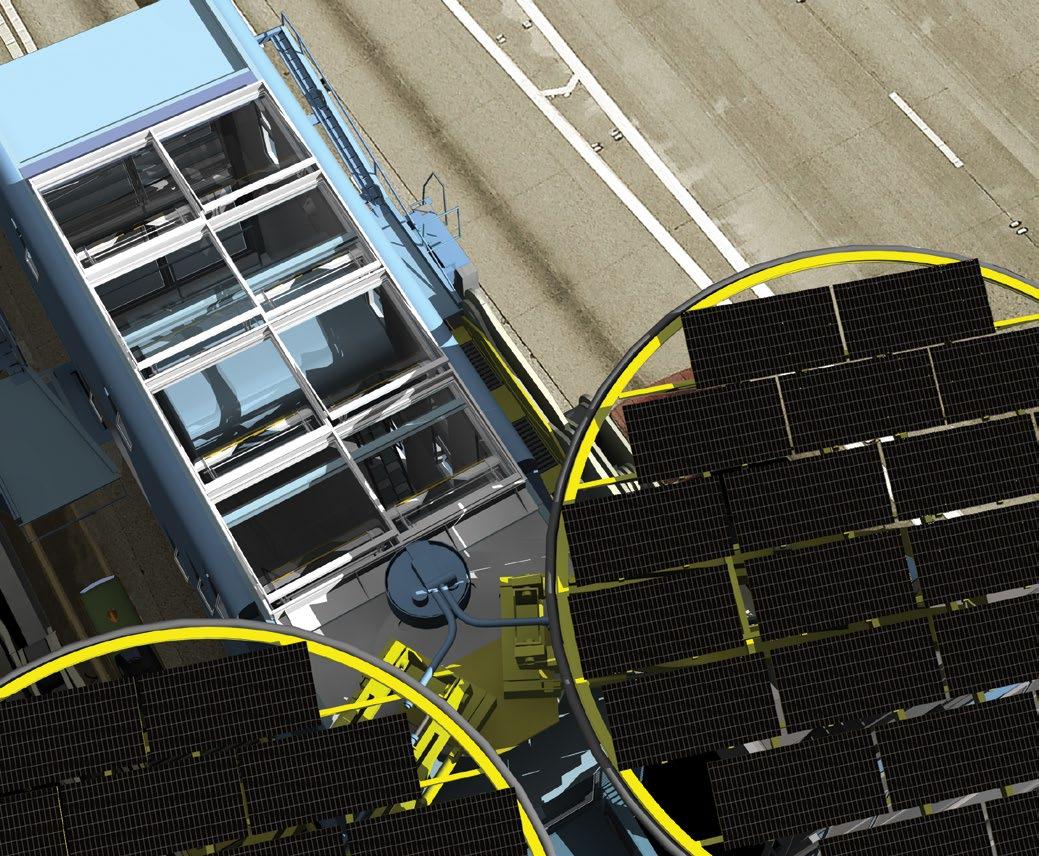

In this view the elov dispenser is full on the eastbound side, while the westbound dispenser rack has only one loaded

Visible here are the solar pizza end effectors and the operable rooftop glazed ventilation system—i.e., the sunroof

A small sampling of first-gen. elovs in several characteristic poses. Refer back to the Sub‘burb project in El Segundo for more on the earliest versions.

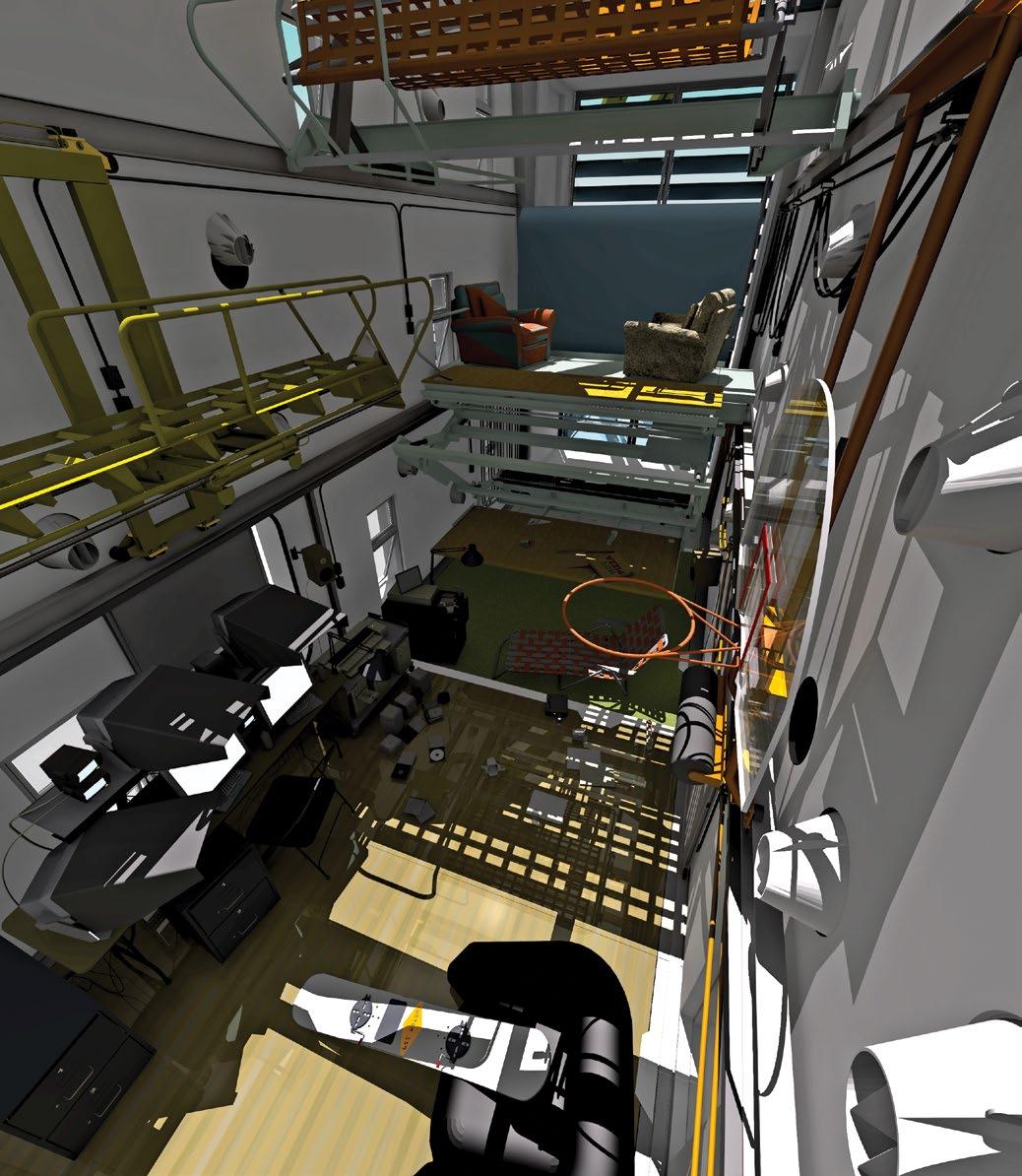

The section from an earlier iteration of the project without all the movable toys, shows the general shape of the enclosed volume and the light sources at either end

Stair and program cores are easily identifiable through their construction and color, whether you can see them straight on or not. Fully glazed slider door openings at either ends of the units would have been a major selling point for either scheme.