Published by Accelerate Learning Inc., 5177 Richmond Ave, Suite 800, Houston, TX 77056. Copyright © 2025, by Accelerate Learning Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written consent of Accelerate Learning Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning.

To learn more, visit us at www.stemscopes.com.

By analyzing data and designing a solution for sustaining biodiversity, the student is expected to demonstrate an understanding of the importance that matter cycles between living and nonliving parts of the ecosystem to sustain life. Student Expectations

How do plants, animals, and even tiny microbes work together to keep our planet full of life and variety?

Key Concepts

• Matter cycles through the atmosphere and biosphere. Matter is ultimately recycled by decomposers. These cycles are important for nutrient availability in ecosystems. Disruptions of the cycling of matter result in the disequilibrium of nutrients in an ecosystem; this can ultimately lead to the destruction of the ecosystem itself.

• Photosynthesis and cellular respiration cycle carbon, moving it through the ecosystem. The carbon cycle links the atmosphere and biosphere. The carbon cycle can be disrupted in various ways.

• Animals obtain food from eating plants or eating other animals. Within individual organisms, food moves through a series of chemical reactions in which it is broken down and rearranged to form new molecules to support growth or to release energy.

• Nitrogen exists in different forms, and only a small portion of it is available for plants to absorb (in the form of ammonium or nitrate-containing compounds). Nitrogen availability is a limiting factor in ecosystems, and increasing its availability disrupts the ecological balance.

• Water is cycled through its many states within the geosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere.

• Biodiversity can be protected through preservation, reforestation, sustainable agriculture and fishing practices, composting instead of landfills, use of green products, etc.

This unit develops students’ understanding of how matter cycles between living and nonliving components and sustains life. Learners trace carbon through food webs and decomposition, model photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and digestion to connect energy flow with conservation of matter, and compare major biogeochemical cycles. They analyze data on disruptions, synthesize patterns in impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services, and communicate evidence-based claims. Students then apply their learning in a design challenge, creating and refining a mitigation plan that balances biodiversity with human needs.

The terms below and their definitions can be found in Picture Vocabulary and are embedded in context throughout the scope.

Atmosphere

The layer of gas surrounding a planet that is held in place by gravity

Biodiversity

The number of different species of plants and animals in an area

Biosphere

The sum of all living matter on Earth

Carbon Cycle

The continuous movement of carbon in and between the abiotic and biotic environments

Carbon Dioxide

A gas that is a natural component of the atmosphere; produced by cells during cellular respiration and used by plants and other organisms for photosynthesis

Carbon Dioxide–Oxygen Cycle

The movement of carbon dioxide and oxygen on Earth by the processes of respiration and photosynthesis

Cellular Respiration

The process of obtaining energy from the breaking of chemical bonds in nutrients

Cycle of Matter

The continuous movement of different types of matter, such as water, phosphorous, nitrogen, and carbon, through different parts of the hydrosphere, lithosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere

Geosphere

Portion of the system of Earth that includes Earth’s interior, rocks and minerals, landforms, and the processes that shape Earth’s surface

Lithosphere

The cool, rigid, outermost layer of Earth that consists of the crust and the uppermost part of the mantle; broken into pieces or segments called plates

Nitrogen Cycle

The process by which nitrogen is converted among various chemical forms as it cycles among the soil, biosphere, lithosphere, and atmosphere

Oxygen

A gas produced by plants during photosynthesis that animals use for respiration

Water Cycle

The constant movement of water through the land, air, oceans, and living things

Students revisit food chains to trace how carbon moves through living and nonliving parts of ecosystems.

• Analyze slides of a food chain and a compost bin to discuss carbon transfer among organisms, decomposers, soil, and plants.

• Create and refine diagrams showing carbon flow through food chains and composting, including uptake by plants via photosynthesis.

• Identify and add pathways that return carbon to the atmosphere (organism respiration, burning of fossil fuels).

• Briefly compare carbon cycling to other element or compound cycles.

Making a Model - Cycling Through Organisms

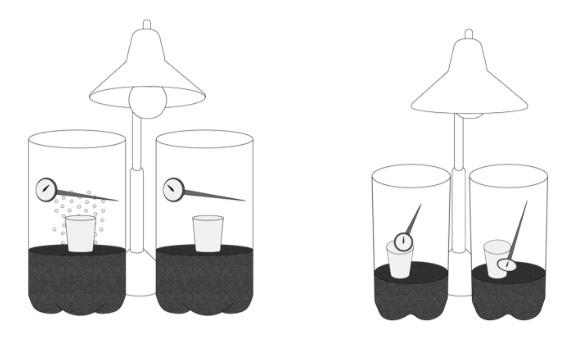

Students investigate how energy flows and matter cycles through photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and digestion using hands-on models.

• Model photosynthesis with station-based snap cubes to simulate inputs, products, and energy transfer in chloroplasts.

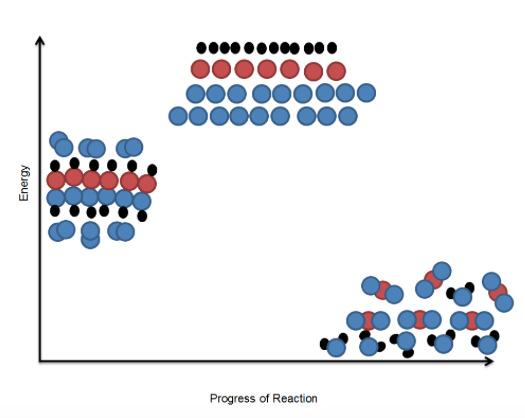

• Construct and break apart molecular models to represent cellular respiration in mitochondria, emphasizing conservation of matter and energy release from bonds.

• Complete enzyme-focused puzzles to model digestion of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids into smaller molecules, connecting breakdown products to respiration.

Students examine how matter cycles sustain ecosystems and how disruptions alter biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human wellbeing.

• Analyze diagrams of the water, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen cycles and write evidence-based explanations of their importance to organisms and ecosystems.

• In groups, investigate assigned disruption scenarios and create skits showing which cycles are affected and how biodiversity, ecosystem services, and humans are impacted.

• Record impacts from their own and peers’ scenarios to synthesize patterns across disruptions.

• Write a letter to the editor explaining why limiting disruptions to matter cycling is essential for sustaining human life.

Students engage in an engineering design challenge to create a wetland mitigation plan that maintains biodiversity and supports human needs.

• Research a local wetland context and collaborate in teams to define criteria and constraints.

• Brainstorm and draft a to-scale diagram or model, including materials, safety, and procedures.

• Build, test, analyze, and iteratively refine the design to meet all criteria and constraints.

• Present solutions, field peer questions, and evaluate designs to identify the strongest features.

Estimated 15 min - 30 min

In this brief Engage activity, students revisit food chains to discuss how carbon cycles through living systems.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Carbon—It's a Cycle (per student)

● 1 Carbon—It's a Cycle Answer Key (per teacher)

● 1 Slide Show (per class)

Set up a computer and projector to show a slide show to the class.

Developing and Using Models, and Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions, and Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will develop and use models to describe and predict how carbon cycles through living systems, illustrating the interactions and energy flows within ecosystems. By drawing diagrams of carbon flow through food chains and compost bins, students will evaluate the limitations of their models and modify them based on evidence to account for changes in variables, such as the introduction of compost as fertilizer. This process will help them construct explanations supported by scientific ideas and principles, demonstrating the interconnectedness of plants, animals, and microbes in maintaining life and biodiversity on Earth.

Notes

Cause and effect: Mechanism and explanation

Systems and system models

Energy and matter: Flows, cycles, and conservation

During this activity, students will explore the phenomenon of how plants, animals, and microbes work together to sustain life on Earth by examining the carbon cycle. They will classify relationships as causal or correlational, recognizing that correlation does not imply causation, and use cause and effect relationships to predict how carbon cycles through natural systems. By creating models of food chains and compost systems, students will understand how systems interact and how energy and matter flow within these systems, illustrating the conservation of matter and the transfer of energy that drives the cycling of carbon.

● Print one Carbon—It's a Cycle document for each student.

● Show the slide of a food chain.

● Ask students to describe the relationship of the element carbon in a food chain.

● The element carbon is a component of all living organisms. When a cow eats a plant, carbon from the plant is passed on to the cow.

● Show the slide of a compost bin.

● Ask students to describe the relationship of carbon in a compost bin.

● Carbon is passed on to the decomposers and into the compost of the bin. When the compost is used as fertilizer, the carbon in the compost is passed on to the soil and then the plants.

● Have students draw a diagram of carbon flowing through a food chain and compost bin.

● Ask students where plants get carbon.

● From the air during photosynthesis

● Ask students how carbon flows from Earth materials and organisms back into the atmosphere.

● Burning of fossil fuels, respiration of organisms

● Have students add the flow of carbon from Earth materials and organisms into the atmosphere in their diagrams.

● Discuss the following:

○ Carbon is one element that cycles through ecosystems to organisms. What are other elements or compounds that flow through similar cycles? Accept all ideas.

Phenomenon Connection

How do the interactions and processes within ecosystems ensure the continuous cycling of carbon, and what role do these cycles play in maintaining life on Earth?

1. In what ways do plants, animals, and microbes contribute to the cycling of carbon within an ecosystem, and how does this process support the diversity of life?

2. How might changes in one part of the carbon cycle, such as increased fossil fuel burning, impact the balance and health of ecosystems globally?

3. What are some other essential cycles, like the carbon cycle, that involve the interaction of living organisms and Earth materials, and how do they contribute to sustaining life on our planet?

FACILITATION TIP

While showing the compost slide, ask: “Does anyone compost at home or know someone who does? What happens to food scraps over time?” This helps students connect science to personal experience.

FACILITATION TIP

As students draw their diagrams, encourage them to use arrows and labels that clearly show processes (photosynthesis, respiration, decomposition, combustion). This builds diagram literacy.

FACILITATION TIP

When discussing other cycles (like nitrogen, water, or oxygen), guide students to compare similarities: matter cycles continuously, energy flows one way.

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

In Part I, students model the process of photosynthesis and demonstrate the transfer of energy in a system. In Part II, students model the breaking down of glucose and oxygen to water and carbon dioxide during cellular respiration. In Part III, students use a puzzle to model how large molecules are broken down into small usable molecules during the digestion of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 Station Cards (per class)

● 1 Mitochondrion (per group)

● 1 Puzzle Pieces (per student)

Reusable

Part I

● 3 snap cubes, yellow (per group)

● 3 snap cubes, orange (per group)

● 12 snap cubes, blue (per group)

● 18 snap cubes, white (per group)

● 6 snap cubes, black (per group)

● 1 bag, plastic, ziplock, quart-size (per group)

● 6 bags, paper, brown, lunch-size (per class)

● 1 marker, black (per teacher)

Part II

● 12 snap cubes of one color (per group)

● 6 snap cubes of another color (per group)

● 18 snap cubes of a different color (per group)

Part III

● 1 scissors (per student)

● 1 glue stick (per student)

Consumable

Part I

● 5 note cards, 5 x 7 inch (per class)

*Note if using STEMscopes kits the colors of the snap cubes may vary.

1. Student Journals can be printed individually for student use, printed as a reusable class set, or assigned online.

2. Review the CER Key prior to conducting the CER with students.

3. Print one Station Cards. Cut the cards for each station and place at the appropriate station.

4. Colors of cubes may be added or substituted if needed. The math department often has snap cubes you can borrow.

5. Label the quart-sized plastic bag as "Photosynthetic Organism." Label one brown paper bag for each station as follows: "Chloroplasts," "Energy," "Hydrogen and Oxygen," and "Oxygen and Carbon."

6. Make a card for each station below with the name and phrase. The number of snap cubes needed for each station should be placed by the Station Card.

Chloroplast Station Supplies: Each group will need three orange cubes. Place all of the cubes needed for the class in the bag labeled "Chloroplasts."

Chloroplast Station Card: To be able to capture the energy from sunlight, you will need to go get chloroplasts for cells. Place three cubes in the "Photosynthetic Organism" bag (the plastic bag).

Energy Station Supplies: Each group will need three yellow cubes. Place all of the cubes needed for the class in the bag labeled "Energy."

Energy Station Card: Collect sunlight. The sunlight will hit the chlorophyll in the chloroplast and start the process. Get three photons (light waves) of light. Snap them to the chloroplasts. Place in the "Photosynthetic Organism" bag (the plastic bag).

Water Station Supplies: Each group will need six oxygen/hydrogen molecules. You may need to use shades of blue due to the high number needed.

Water Station Card: Collect at least six water molecules for the process. You will need two snap cubes for hydrogen (blue) and one white snap cube (oxygen) together to represent one molecule of water. Place the completed water molecules in the "Photosynthetic Organism" bag (the plastic bag).

Carbon Dioxide Station Supplies: You will need two white snap cubes for oxygen and one black snap cube for carbon. Each group will need six molecules of carbon dioxide.

Carbon Dioxide Station Card: The photosynthetic organism will gather carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. You will need six molecules of carbon dioxide (six carbon atoms and 12 oxygen atoms) to make food (chemical energy) for the plant. Place the needed atoms in the "Photosynthetic Organism" bag (the plastic bag).

Print one Student Journal for each student in your class.

Obtain materials. The math department may have snap cubes available, or you may use snap beads.

Each group does not need to have the same colors to represent the three elements, but within each group, all of the snap cubes for the element carbon should be the same color and so on.

Print one Puzzle Pieces for each student.

Developing and Using Models, and Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions, and Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will develop and use models to describe and predict how plants, animals, and microbes interact to sustain life on Earth. By modeling photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and digestion, students will evaluate the limitations of these models and modify them based on evidence to understand the cycling of energy and matter. This process allows students to construct explanations and design solutions for the phenomenon of how these organisms work together to maintain biodiversity and life on our planet.

Cause and effect: Mechanism and explanation

Systems and system models

Energy and matter: Flows, cycles, and conservation

During this activity, students will explore the phenomenon of how plants, animals, and microbes work together to sustain life on Earth by modeling photosynthesis and cellular respiration. They will use cause and effect relationships to predict and understand these processes, recognizing that multiple factors contribute to these natural systems. Students will also use system models to represent interactions within and between systems, such as energy and matter flows, and learn that these models have limitations. Through this, they will gain insights into the conservation of matter and the transfer of energy, which drives the cycling of matter in Earth’s systems.

Notes

Part I

Students work in groups of four to complete this task.

Pre-Activity Discussion

1. What do plants need to live? Plants need water, air, soil, and sunlight.

2. What materials do plants need for growth? Plants need water, air, and sunlight.

3. How do plants get energy? Plants get energy from the Sun. Have students complete Part I of their Student Journal.

Post-Activity Discussion

1. How does photosynthesis cycle carbon into and out of organisms? The carbon begins as gas in the air and is absorbed into the leaves. It is then changed into a solid and part of the plant as glucose. When an animal eats the plant, the carbon becomes part of the animal.

2. How does photosynthesis cycle oxygen into and out of organisms? Oxygen enters the plant in two different ways. Through water molecules, it enters the plant through its roots from the soil. Through carbon dioxide molecules, it enters the leaves from the atmosphere. Photosynthesis causes some of the oxygen to remain in the plant as part of the glucose molecule. The rest of the oxygen is released into the atmosphere as oxygen gas. Animals can get the oxygen either by breathing in the oxygen gas or by eating the plant and absorbing the oxygen in the water and carbohydrates of the plant.

3. What is the path or flow of energy in the process of photosynthesis? The energy flows from the Sun in the form of sunlight. The energy is absorbed by the organism into the chloroplasts. The process of photosynthesis transforms, or changes, the light energy into chemical energy or stored energy.

Pre-Activity Discussion

1. What is an element? A pure chemical substance consisting of a single type of atom

2. What is a molecule? The smallest particle in a chemical element or compound that has the chemical properties of that element or compound

3. How are molecules held together? Molecules are held together by chemical bonds.

4. What does a molecule of oxygen look like? It has two oxygen atoms bonded together.

Notes

5. What is the chemical formula for carbon dioxide? CO2

6. What would a molecule of carbon dioxide look like? It would have one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms bonded together. By the end of the Pre-Activity Discussion, students should be thinking about the molecules and their bonds.

Have students complete Part II of their Student Journal.

Post-Activity Discussion

1. Was matter created or destroyed in the cellular respiration process? No

2. How do you know? We ended with the same atoms with which we started, and no atoms were left in the mitochondrion.

3. What did you do to model the release of energy during the cellular respiration process? I broke the bonds holding the molecules together by unsnapping the cubes.

Part III

Students work individually to complete this task.

Pre-Activity Discussion

1. What are the three basic molecular categories of nutrients from food? Carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids

2. Molecules of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids are too large to enter our bloodstream. How are the molecules broken down into a usable size? Accept all ideas.

Work the Carbohydrate Puzzle as a class so students understand the correct placement of the pieces. Discuss what is occurring in each step. (Example: Before the reaction, the large molecule is intact. During the reaction, the large molecule begins to break apart. After the reaction, the large molecule has broken down into the smaller molecules. Throughout, the enzyme remains unchanged.)

Notes

FACILITATION TIP

Prompt students to compare their cube models to the actual chemical formulas written on the board, reinforcing the link between the physical model and symbolic notation.

If students struggle with molecular bonding, remind them that the snapping cubes represent bonds that can be broken and re-formed.

FACILITATION TIP

Nutrients may be new vocabulary for students. You can refer to nutrition labels to help students make sense of the terms.

Procedure

1. Locate the puzzle pieces on the Puzzle Pieces. Color the large carbohydrate molecule orange, the enzyme-engaged molecule orange, and the sugar molecules pink.

2. Cut out each of the pieces for the carbohydrate puzzle.

FACILITATION TIP

Have students work with a partner to check that their puzzle diagrams match the correct sequence before gluing them down.

3. Color the enzymes associated with the breakdown of carbohydrates green.

4. Glue the pieces to complete the carbohydrate puzzle.

5. Repeat steps 1 through 4 to complete the protein puzzle and the lipid puzzle, but color the pieces using the following coloring key:

○ Large protein molecules: red

○ Enzyme-engaged protein molecules: red

○ Amino acids: yellow

○ Enzymes associated with the breakdown of proteins: brown

○ Bile: gray

○ Large fat (lipid) molecules: blue

○ Enzyme-engaged lipid molecules: blue

○ Fatty acids: white

○ Enzymes associated with the breakdown of lipids: purple

6. Use the digestion models and your knowledge of cellular respiration to describe how food molecules are processed through chemical reactions involving oxygen to form new molecules.

Post-Activity Discussion

1. How are food molecules broken down into molecules usable by the human body? The large molecules are broken down by chemical reactions involving oxygen aided by enzymes and other substances such as water for carbohydrates, stomach acid for proteins, and bile for lipids.

2. How is the process of digestion part of the cycling of matter through Earth’s systems? Digestion involves the molecules of glucose moving from plants to a human, with some molecules of carbon dioxide being expelled into the air and some molecules remaining in the human.

This activity requires much writing, which may be difficult for some students. Since the goal is not to measure the ability to read and write, and since there are multiple questions to answer about the stations, students could dictate the answers to a scribe or orally answer the questions from the handout. Learn more strategies to help students with difficulty writing in the Intervention Toolbox.

Notes

For beginner and intermediate ELPs, have the materials translated into their native language as a reference for them to use during the activity. Prior to students completing the activity, say the words and have the students repeat them.

When teaching the words, concentrate on using them repeatedly and with examples. This will also facilitate students' ability to communicate with other students using academic vocabulary.

To check their understanding and to keep for future reference, students can draw pictures and complete the following sentence stems in their journals after the group activity. You can give students the option of using a word bank to label their pictures or of labeling them without a word bank. Students may also read the sentences out loud with a partner or in their groups.

Possible questions and sentence stems could be the following:

● Level 1 Knowledge Question: What are the starting chemicals in photosynthesis?

○ Stem: The starting chemicals in photosynthesis are _______.

● Level 2 Comprehension Question: Can you explain what a product is?

○ Stem: A product is ________.

● Level 3 Application Question: How would you show your understanding of the energy source of photosynthesis?

○ Stem: I would show my understanding of the energy source by ________.

● Level 4 Analysis Question: Can you categorize the differences between photosynthesis and cellular respiration?

○ Stem: The differences are _________.

● Level 5 Synthesis Question: Can you create a model that shows how cellular respiration works?

○ Stem: My model looks like ________.

● Level 6 Evaluation Question: How could you determine the types of energy transformations that occur during photosynthesis or cellular respiration?

○ Stem: I could determine the types of energy transformations that occur by __________.

How do these biological processes ensure the continuous cycling of matter and energy within ecosystems?

1. In what ways do photosynthesis and cellular respiration complement each other in the cycling of carbon and oxygen through ecosystems?

2. How does the digestion of food in animals contribute to the cycling of nutrients and energy in the environment?

3. How might disruptions in one of these processes affect the balance of life and variety on our planet?

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

In this activity, students analyze diagrams of the water, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen cycles to determine the importance of each to ecosystems and organisms. Students develop and perform skits addressing how disruptions in the cycling of matter could affect biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 Diagram Cycles (per group)

● 1 Disruption Scenarios (per class)

Reusable

● 1 marker, set (per group)

Consumable

● 1 board, poster, white (per group)

1. Print one set of Diagram Cycles per group. As this is a large packet, it is recommended that you print this packet double-sided and then laminate it for repeated use.

2. Print one Disruption Scenarios and cut the cards apart to distribute one card to each group.

3. Plan to divide the class into six groups for Part II.

4. Students can use props to help with the visual aid portion of their skits. Some props might include construction paper for students to write or draw their roles. Students may choose to bring props from home.

Developing and Using Models, and Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions, and Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will develop and use models to describe and predict how disruptions in the cycling of matter, such as water, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen cycles, affect biodiversity and ecosystem services. By analyzing diagrams and performing skits, they will construct explanations based on evidence to understand the interconnectedness of plants, animals, and microbes in maintaining Earth’s life and variety. Students will also communicate their findings through written and oral presentations, evaluating the impact of these disruptions on human sustainability and the natural world.

Cause and effect: Mechanism and explanation

Systems and system models

Energy and matter: Flows, cycles, and conservation

During this activity, students will explore the cause and effect relationships within the cycles of matter, such as water, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, to understand how disruptions can impact biodiversity and ecosystem services. By analyzing these cycles and performing skits, students will classify relationships as causal or correlational, recognizing that correlation does not necessarily imply causation. They will use models to represent systems and their interactions, understanding that systems may interact with other systems and have sub-systems. Additionally, students will track the transfer of energy and matter, learning how these flows drive the motion and cycling of matter within ecosystems, ultimately affecting the sustainability of human life on Earth.

1. Have students analyze the diagrams for each of the ways matter is cycled through Earth’s system.

2. Have them write an evidence-supported description of the importance of each cycle to the health of organisms and ecosystems.

1. Divide the class into six groups and assign each group one of the disruption scenarios.

2. Instruct students to collaborate with their group members to discuss how their ecosystem is affected.

3. Ask students to record their disruption and a brief description of its effect on the cycling of matter. They should include how the change to the affected cycle(s) results in changes to the ecosystem services and the biodiversity or the number of different types of organisms in the system. Students should also record how the changes could affect humans.

4. Have students plan their skit, using any supplies you provide for visual aids. Make sure students show how biodiversity and ecosystem services are affected and indicate which cycles are affected by the disruption. Have students discuss how the changes may impact human life.

5. While students watch the other groups perform their skits, have them record their disruptions and effects as well.

6. Instruct students to use their collected information to write a letter to the editor of their local paper to explain how disruptions to the cycling of matter affect the sustainability of human life on Earth and should be limited.

Disruption Scenarios

● An extended period of extreme drought

● Deforestation in a local forest to build a large shopping mall with parking lots

● Increase in fossil fuel emissions of carbon dioxide due to added power plants in an area

● Overuse of pesticides resulting in an almost total removal of the bacterial population living within the soil

● Increase in chemical fertilizers for plants, causing runoff to carry fertilizer to plants in natural areas

● Massive volcanic eruption resulting in global dimming from ash remaining in the atmosphere

Before starting, remind students of the law of conservation of matter and ask: “If matter can’t be created or destroyed, what must be happening when it moves through cycles?”

If students struggle with the “Interaction with Other Cycles” column, provide examples such as:

The carbon cycle interacts with the oxygen cycle during photosynthesis and respiration.

The water cycle impacts the nitrogen cycle through precipitation moving nitrogen into soils.

Wrap up with a reflection question: “Which ecosystem services do you personally depend on most, and how would your life change if they were disrupted?”

Sentence Stems

For beginner and intermediate ELPs, have the materials translated into their native language as a reference for them to use during the activity. Prior to the students completing the activity, say the words and have the students repeat them.

After the students have time to explore with the animal and plant cards, give them the opportunity to write down their self-reflections by using the following sentence stems:

● The plant and animal exchange _____________ and _____________________.

● The plant releases _____________, while the animal releases ______________.

● The plant uses __________________, and the animal uses _____________________.

Have the students write the sentence stems in their journals. Group them into partners so they can share their sentence stems with each other.

How do disruptions in natural cycles impact the collaboration between plants, animals, and microbes to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem services on Earth?

1. How do the water, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen cycles contribute to the balance and health of ecosystems?

2. In what ways might a disruption in one of these cycles affect the biodiversity within an ecosystem?

3. How could changes in these cycles impact human life and what actions can we take to mitigate these effects?

Estimated 2 hrs - 3 hrs

Students use criteria and constraints to design a wetland mitigation project with the goal of maintaining biodiversity and the resources humans need for survival.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student) The following materials are suggested per group. Other materials may be utilized in this Engineering Solution as available.

Reusable, suggested

● Ruler, metric (per group)

● Computer with Internet connection (per group)

● 1 box or container (per group)

● 1 set of markers (per group)

Consumable, suggested

● Paper, graph, 1 cm2, 8.5 x 11 (per group)

● Paper, notebook (per group)

● 6 straws (per group)

● Variety of cardboard scraps (per group)

● Construction paper, various colors (per group)

● Clay (per group)

● Duct tape (per group)

● Student Journals can be printed individually for student use, printed as a reusable class set, or assigned online.

● Students will request materials to create their models. Select and display materials that are readily available.

Technology Suggestion

You may want to review the process for using different search engine tools and the procedure for verifying sources of online information. You can also set up a web page with links for the assignment.

● String or wire (per group) Notes

Developing and Using Models, and Constructing, Explanations and Designing Solutions, and Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will develop and use models to describe and predict how plants, animals, and microbes interact within ecosystems to maintain biodiversity and support life on Earth. By designing a wetland mitigation project, students will evaluate the limitations of their models, modify them based on evidence, and construct explanations using scientific principles. This process will help them understand the complex interactions and energy flows within ecosystems, and how these systems can be designed to optimize biodiversity and resource availability.

Cause and effect: Mechanism and explanation

Systems and system models

Energy and matter: Flows, cycles, and conservation

During this activity, students will engage in designing a wetland mitigation project, which will allow them to explore the cause and effect relationships within ecosystems. They will classify these relationships as causal or correlational, recognizing that correlation does not necessarily imply causation. By using models to represent the interactions within the wetland system, students will understand how systems interact with other systems and how energy and matter flow within these systems. This hands-on experience will help them predict how plants, animals, and microbes work together to sustain biodiversity and maintain the resources necessary for life on Earth.

The deliverable for this design challenge is a detailed to-scale diagram or model of a wetland built as a mitigation project. If you choose to have the students actually build the wetland, be prepared to provide the materials students request, or set additional constraints based on the available materials. Select a local wetland to be the one replaced.

21st Century Skills addressed: Innovation

Students create a new and original solution to a problem by creating a new design for a wetland mitigation.

The skills used by engineers to identify and solve problems are useful well beyond the science classroom and an important part of being able to function in and contribute meaningfully to society. When we say “developing engineering solution,” we are describing the intentional immersion of students in the reiterative engineering design process. For further information regarding developing engineering solutions, please click the provided link. A. Introduce the design challenge.

● Discuss the criteria for the design challenge.

● Remind students that their design solution must include all needed materials, safety precautions, and procedures used so that anyone can replicate the investigation.

● Have students test their design as needed.

● Instruct students to have a method for determining that all criteria and constraints have been met.

Clarify the constraints visually.

Post a one-page “Challenge Card” that lists the 10-mi² size constraint, required services, resources requirement (rainfall), deliverables (to-scale diagram, materials list, construction, and maintenance instructions). Keep it visible throughout work time.

FACILITATION TIP

Use low-cost modelling constraints to teach trade-offs.

Limit the number of “premium” items (e.g., only two pumps or one waterproof liner per group). This forces trade-offs and mirrors real engineering constraints.

A. Research and explore the problem.

● Remind students that engineers usually work in groups or teams so that many different ideas can be generated and combined to come up with one great idea. Divide the class into groups.

● Give each group a copy of the design challenge along with the rubric.

● Make sure the materials needed to complete the project are in a central location where groups can access them as needed.

B. Brainstorm and design a solution to the problem.

● Give students time to brainstorm and design.

● Make sure students have created a materials list, safety precautions list, and a procedure before they proceed.

● Assist students as needed.

C. Build, test, and analyze your solution.

FACILITATION TIP

Provide design templates and a scale primer.

Give a simple scale worksheet (e.g., 1 cm = 0.5 mi) and a blank grid map so groups can quickly convert 10 square miles into a classroom drawing. Model one example conversion and a quick sketch.

● Monitor as the students complete the design process.

● Ask questions and redirect thinking as necessary.

● Allow sufficient in-class time for groups to complete their project.

D. Improve or redesign and retest your solution.

● Give the groups time to analyze their criteria on the design process.

● Assist the students in redesigning and retesting the solution as needed.

E. Present and share your solution.

● Allow time for each group to present their results.

● Let other groups ask questions. Discuss as desired.

● Lead class discussion of evaluations of each solution and possible combinations to create a best solution.

● Complete the group rubric for each group.

● Discuss with students.

● Hold a Post-Activity Discussion, which includes the post-activity discussion questions for students to evaluate their solution and make notes for improvement.

1. How many of the ecosystem services were you able to design into your wetland mitigation project? Answers will vary. Example: Our solution addresses all of the wetland services except for buffering ocean waves.

2. What services were you not able to use in your project? Explain why you could not put them in your project. Answers will vary. Example: Our solution does not address buffering ocean waves as our wetland does not share a coastline with the ocean.

3. After listening to each presentation, what solution to the design problem was the best? Explain. Answers will vary but should show how the solution meets the criteria.

4. If you could choose aspects of each of the designs presented, which could be combined to form the best possible solution? Answers will vary but should show how the chosen aspects best meet the criteria.

Connection Sticky Notes

For beginner and intermediate ELPs, have the materials translated into their native language as a reference for them to use during the activity. Prior to the students completing the activity, say the words and have the students repeat them.

As students research about wetlands and ways to conserve their biodiversity, they will run across many new terms. Instruct the students to create three columns in their lab journals with these labels:

● New Key Terms

○ Students should create at least four sticky notes for the New Key Terms section.

● Similar To

○ The Similar To section requires at least two sticky notes, on which students compare the results of their research to something that has occurred in their home state.

● Human Actions

○ The Human Actions section should include the ideas students uncover in their research, with one or two examples on each, either positively or negatively affecting wetlands.

Phenomenon Connection

How do the interactions between plants, animals, and microbes in a wetland ecosystem contribute to maintaining biodiversity and supporting human needs?

1. How does your wetland mitigation design ensure the survival and interaction of different species within the ecosystem?

2. In what ways does your project demonstrate the interdependence of plants, animals, and microbes in maintaining a healthy ecosystem?

3. How can the principles used in your wetland design be applied to other ecosystems to enhance biodiversity and resource availability for humans?

Notes

STEMscopedia

Reference materials that includes parent connections, career connections, technology, and science news.

Linking Literacy

Strategies to help students comprehend difficult informational text.

Picture Vocabulary

A slide presentation of important vocabulary terms along with a picture and definition.

Content Connections Video

A video-based activity where students watch a video clip that relates to the scope’s content and answer questions.

Career Connections - Arborist

STEM careers come to life with these leveled career exploration videos and student guides designed to take the learning further.

Math Connections

A practice that uses grade-level appropriate math activities to address the concept.

Reading Science - Carbon’s Long Journey

A reading passage about the concept, which includes five to eight comprehension questions.

Notes

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

An assessment in which students write a scientific explanation to show their understanding of the concept in a way that uses evidence.

Multiple Choice Assessment

A standards-based assessment designed to gauge students’ understanding of the science concept using their selections of the best possible answers from a list of choices

Open-Ended Response Assessment

A short-answer and essay assessment to evaluate student mastery of the concept.

Guided Practice

A guide that shows the teacher how to administer a smallgroup lesson to students who need intervention on the topic.

Independent Practice

A fill in the blank sheet that helps students master the vocabulary of this scope.

Extensions

A set of ideas and activities that can help further elaborate on the concept.

Use this template to decide how to assess your students for concept mastery. Depending on the format of the assessment, you can identify prompts and intended responses that would measure student mastery of the expectation. See the beginning of this scope to identify standards and grade-level expectations.

Student Learning Objectives

Matter cycles through the atmosphere and biosphere. Matter is ultimately recycled by decomposers. These cycles are important for nutrient availability in ecosystems. Disruptions of the cycling of matter result in the disequilibrium of nutrients in an ecosystem; this can ultimately lead to the destruction of the ecosystem itself.

Photosynthesis and cellular respiration cycle carbon, moving it through the ecosystem. The carbon cycle links the atmosphere and biosphere. The carbon cycle can be disrupted in various ways.

Animals obtain food from eating plants or eating other animals. Within individual organisms, food moves through a series of chemical reactions in which it is broken down and rearranged to form new molecules to support growth or to release energy.

Nitrogen exists in different forms, and only a small portion of it is available for plants to absorb (in the form of ammonium or nitratecontaining compounds). Nitrogen availability is a limiting factor in ecosystems, and increasing its availability disrupts the ecological balance.

Water is cycled through its many states within the geosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere.

Biodiversity can be protected through preservation, reforestation, sustainable agriculture and fishing practices, composting instead of landfills, use of green products, etc.

The student is expected to demonstrate an understanding of the physical and chemical properties of matter through analysis of qualitative data.

• The matter that makes up our world has physical and chemical properties that can be used for classification.

• The physical properties of matter include properties that describe the substance, such as color, smell, boiling point, and density.

• Chemical properties of matter include all the possible chemical changes that a sample of matter can undergo, such as corrosion, toxicity (the degree to which a substance is poisonous to an organism or the environment), and the ability to burn.

Scope Overview

This unit builds conceptual understanding of matter by contrasting physical and chemical properties through observation, discussion, and evidence-based classification. Students qualitatively analyze magnetism, density-related behavior, solubility, thermal and electrical conductivity, and melting/boiling points, then examine reactivity, rusting, combustion, and flammability using rotating stations. Culminating investigations have students plan tests to distinguish and identify unknown liquids, record observational data, compare to reference properties, and justify claims with evidence. Emphasis is on analyzing qualitative data to demonstrate understanding of matter’s properties.

Scope Vocabulary

The terms below and their definitions can be found in Picture Vocabulary and are embedded in context throughout the scope.

Chemical Energy

Energy stored in chemical bonds and released through chemical reactions

Chemical Property

A characteristic that can be observed or measured only when atoms rearrange during a chemical change

Corrosion

The process of destroying a solid material by a chemical reaction

Density

The amount of matter in a given space or volume

Physical Property

A characteristic that can be observed or measured without changing the substance

Toxic

Harmful to lif

Notes

Students explore how to distinguish between physical and chemical properties through sorting and discussion.

• Engage in a brief discussion on how observable characteristics and tests help identify substances.

• Work in pairs to sort scenario cards into physical vs. chemical properties using evidence from examples.

• Participate in a class review to confirm classifications and connect scenarios to key vocabulary (e.g., flammability, solubility, density).

Activity - Physical Properties

Students investigate the states and properties of matter through hands-on measurement and testing across six stations.

• Test household items for magnetism and classify materials as magnetic or nonmagnetic.

• Measure mass, volume, and displacement to calculate density and predict sinking or floating; compare solubility of common solutes in water over time.

• Compare thermal conductivity by observing ice melt in different cup materials and analyze which materials transfer heat best.

• Build a simple circuit to identify electrical conductors and insulators; organize substances by melting and boiling points using reference cards and a thermometer.

Activity - Observing Chemical Properties

Students investigate common chemical properties through rotating lab stations.

• Rotate through five stations to test materials: vinegar with baking soda, steel wool with vinegar/oxygen, match combustion, effervescent tablet with water, and iodine with potato starch.

• Observe and record evidence of chemical change in their journals.

• Identify and categorize chemical properties such as reactivity with acids and water, rusting, and flammability.

• Share and synthesize findings in a post-lab discussion.

Scientific Investigation - Identifying Liquids

Students plan and conduct an investigation to identify four unknown clear liquids using characteristic physical and chemical properties.

• Design and carry out tests (e.g., melting/boiling point, density, solubility, odor, flammability) to generate distinguishing data.

• Use lab tools to measure and record observations, then compare results to reference properties to determine each liquid’s identity.

• Justify identifications by constructing a concise conclusion and scientific explanation connecting evidence to claims.

Notes

Estimated 15 min - 30 min

In this activity, students determine whether properties are physical or chemical properties.

Material

Printed

● 1 Sorting Properties (per student)

● 1 Card Sort Cards (per pair)

● You may choose to either print out a page for each student, or you could also project the page on the board.

● Print Card Sort Cards on card stock and consider laminating them for reuse.

Planning and Carrying Out Investigations, and Analyzing and Interpreting Data, and Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking

During this activity, students will plan and carry out investigations to explore the phenomenon of a solid ice cube melting into liquid water and then disappearing into the air as gas. They will identify and analyze the physical and chemical properties involved in each phase change, such as melting point and boiling point, and use these investigations to provide evidence for the changes in properties. By analyzing and interpreting data, students will distinguish between physical and chemical changes, using mathematical and computational thinking to support their explanations and understand the underlying processes.

Conservation

During this activity, students will identify and analyze patterns in the physical and chemical properties of substances to understand the phenomenon of how a solid ice cube melts into liquid water and then disappears into the air as gas. They will recognize that macroscopic patterns, such as changes in state, are related to the microscopic and atomic-level structure of matter. Additionally, students will explore how the transfer of energy drives these changes, tracking how energy flows through the system as matter cycles between solid, liquid, and gas states. Activity

Pre-Activity Discussion

1. If you have a pencil and a pen in front of you, and you are instructed to pick up the pencil, how do you know which of the two objects to pick up? What tells you which one is the pen and which one is the pencil? Accept all ideas.

2. How do we tell the difference between all of the objects we encounter in our everyday lives? They look and feel different. They have different shapes, colors, sizes, and textures. They have different temperatures and scents. Each object has a group of characteristics that distinguish it from other objects.

3. What if the substances are colorless, odorless gases? You could perform tests on the gases.

Post-Activity Discussion

1. Discuss correct answers to the sort.

2. Introduce vocabulary related to scenarios.

Ice melts. (melting point)

Water evaporates. (boiling point)

A skillet conducts heat. (conductivity)

A rock sinks. (density)

Sugar dissolves in water. (solubility)

A penny is shiny. (luster)

Metals can be pulled and stretched. (ductility)

Iron filings are attracted to a magnet. (magnetism)

Phenomenon Connection

Chemical

Carbon dioxide extinguishes a fire. (flammability, not flammable)

Hydrogen gas lights on fire. (flammability)

Gasoline burns in an engine. (combustibility)

Iron rusts. (reacts with oxygen)

Baking soda and vinegar bubble when mixed. (chemical reactivity)

Uranium is radioactive. (radioactivity)

Sugar burns when heated. (flammability)

Sodium bursts into flames in water. (reacts with water)

How do the physical and chemical properties of substances help us understand the changes that occur when a solid ice cube melts into liquid water and then disappears into the air as gas?

1. What physical properties of ice and water can help us predict the conditions under which ice will melt and water will evaporate?

2. How do the chemical properties of water remain unchanged during the phase transitions from solid to liquid to gas?

3. In what ways can understanding the properties of substances help us manipulate the rate at which an ice cube melts or water evaporates?

FACILITATION TIP

Monitor for misconceptions. Listen for students confusing physical change (like melting) with chemical property. Redirect by asking: “Does the substance stay the same after this property is observed, or does it form something new?”

FACILITATION TIP

Show one example card to the whole class and think aloud: “This property describes how something looks/feels, so it’s physical. This one describes how it reacts with another substance, so it’s chemical.”

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

In this activity, students use various measurement tools to explore states and properties of matter. The activity is divided into six stations: Magnetism, Density, Solubility, Thermal Conductivity, Electrical Conductivity, and Phase Changes.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 Station Signs (per class)

● 1 Station 6: Thermometer (per class)

● 1 Station 6: Melting and Boiling Point Cards (per class)

● 2 Station 2: Density (per class)

● 1 Station Instruction Cards (per class)

Reusable

Station 1: Magnetism

● 20 common household items (mix of magnetic and nonmagnetic items) (per class)

● 1 container for the items (per class)

● 4 strong magnets (per student in each group)

Station 2: Density

● 1 triple-beam balance (per class)

● 1 graduated cylinder, plastic, 250 mL (per class)

● 1 metric ruler (per class)

● 1 calculator (per class)

● 2 regularly shaped objects (per class)

● 2 irregularly shaped objects (per class)

● 1 water source (per class)

● 4 sheet protectors (per class)

Station 3: Solubility

● 5 containers, labeled A, B, C, D, and E (per class)

● 5 timers or student watches (per class)

● 5 cups, clear, plastic, 9 oz (per class)

● 5 spoons, plastic (per class)

● 5 graduated cylinders, 100 mL (per class)

● 5 measuring spoons (per class)

● 1 goggles, pair (per student)

Station 4: Thermal Conductivity

● 3 aluminum baking pans, 2 in. deep (per class)

● 3 cups, clear, plastic, 9 oz (per class)

● 3 foam cups, 9 oz (per class)

● 3 cups, paper, 8 oz (per class)

● 1 cooler for ice cubes (per class)

● 1 timer (per class)

Station 5: Electrical Conductivity

● 1 piece of thick cloth, felt (per class)

● Several coins (penny, nickel, dime, quarter) (per class)

● 1 strip of aluminum foil (per class)

● 1 craft stick (per class)

● 1 plastic spoon (per class)

● Ceramic tiles (per class)

● Rubber erasers (per class)

● Materials to build a simple circuit: battery, battery holder, 3–6 in. wires, light bulbs, and bulb holder (per class)

Station 6: Melting and Boiling Points

● 1 resealable plastic bag (per class)

Consumable

Station 3: Solubility

● Solutes: salt, sugar, drink powder, baking soda, cornstarch (per class)

● Water, 500 mL (per class)

Station 4: Thermal Conductivity

● Ice cubes (per class)

Preparation

● Print and post the Station Signs.

● Print one Station Instruction Cards. Cut apart and place at the appropriate station.

Station 1: Magnetism

1. Place about 20 common household items in a container on the table. Examples of items include children’s toys, kitchen utensils or tools, office or school supplies, nature items, etc. Be sure that the materials from which these objects are made include plastic, rubber, cloth, wood, stone, magnetic, and nonmagnetic materials. About half the items should be magnetic.

Station 2: Density

1. Print and place in sheet protectors two copies of the Student Reference Sheet: Station 2: Density.

2. The irregularly shaped objects used should fit in the graduated cylinder without getting stuck. You can adjust the size of the graduated cylinder to be compatible with the size of the object.

3. Determine the density of each object before you implement this activity. If the density is greater than 1 g/cm3, the object will sink; if the density is less than 1 g/cm3, the object will float.

4. You may want students to rotate objects to decrease the number of items you have to deal with.

Station 3: Solubility

1. Caution! Remind students to wear goggles and waft scents at all times.

2. Fill each of the five labeled (A–E) containers with one of the solutes. Remember to record which solute is in which container for your reference.

Station 4: Thermal Conductivity

1. This activity may be done with partners in each group. Place a foam cup, a plastic cup, and a paper cup in the aluminum pan. Keep a small cooler to hold the ice during the class period.

2. You may determine that a longer time period—for example, 4 or 5 minutes—yields better observations for this station activity. If so, tell students to make the adjustment on their Station 4 procedure.

Station 5: Electrical Conductivity

1. Provide materials for students to create a simple electric circuit.

2. Each student can have his or her own circuit, or one circuit can be used by multiple students to test different materials.

Station 6: Melting and Boiling Points

1. Print and laminate the Melting and Boiling Point Cards.

2. Place the cards in a resealable plastic bag. Print, laminate, and cut out the Thermometer, and tape the two pieces together.

Planning and Carrying Out Investigations, and Analyzing and Interpreting Data, and Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking

During this activity, students will plan and carry out investigations to explore the phenomenon of why a solid ice cube melts into liquid water and then disappears into the air as gas. By using various measurement tools at different stations, they will identify independent and dependent variables, collect and analyze data, and evaluate the accuracy of their methods. This hands-on approach will help them understand the changes in properties during each phase transition and provide evidence to support scientific explanations for the observed phenomena.

Patterns and Energy and matter: Flows, cycles, and conservation

During this activity, students will explore the states and properties of matter through various measurement tools, allowing them to recognize patterns in the rates of change and numerical relationships at both macroscopic and microscopic levels. As they investigate phase changes, they will understand how energy transfer drives the motion and cycling of matter, and how matter is conserved during physical processes, providing insights into the phenomenon of an ice cube melting and transitioning into gas.

1. Review with students how to find the density of an object before they begin stations.

2. Station 2: You may want to have the students round their answers if they have trouble working with decimals.

3. Station 6: Tell students that not all the cards fit on the thermometer. They can place cards outside the thermometer range.

Safety Goggles

When using any form of very small particles or powder, it is safest for students to protect their eyes by wearing goggles.

Wafting

Students should waft in order to smell substances rather than directly inhaling.

Electric Circuit

When testing conductivity, tell students not to touch wires to objects, especially body parts or wet materials, unless directed to do so.

Think, Draw, Explain

For beginner and intermediate ELPs, have the materials translated into their native language as a reference for them to use during the activity. Prior to the students completing the activity, say the words and have the students repeat them.

After the students have had a chance to explore through the investigation, give them an opportunity to show their understanding. Write the following question on the board: What is the difference between density and mass?

● First, ask your students to think.

● Then ask them to draw their response on paper.

● After they are finished with the drawing, ask them to explain their answer.

● Provide them with the following sentence stem:

○ The difference between density and mass is ___________. The above process can be duplicated for any other term from the Explore activity that is giving students trouble.

When an ice cube melts and eventually turns into gas, what happens to its properties, and how can we be sure that all the matter is still present in a different form?

1. Based on your observations at the thermal conductivity station, how does the material of a container affect the rate at which an ice cube melts, and what implications does this have for the conservation of matter?

2. After comparing the density of different objects, how can we use density to predict whether the liquid from a melted ice cube will occupy the same volume when refrozen, and what does this tell us about the conservation of mass?

3. Considering the solubility station, how might the solubility of a substance change as it transitions from solid to liquid to gas, and how does this relate to the properties of matter during phase changes?

Estimated 30 min - 45 min

Students test objects to observe chemical properties.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 Station Instruction Cards (per class)

Reusable

● 2 large test tubes (per class)

● 2 sets of forceps (per class)

● 1 small beaker or plastic cup (per class)

● 1 dropper bottle (per class)

Consumable

● 50 mL vinegar (per group)

● 1 tbsp baking soda (per group)

● 1 piece steel wool, 2 cm x 2 cm (per group)

● 3–4 drops iodine (per group)

● 1 match (per group)

● ½ effervescent tablet (per group)

● 1 wooden coffee stir stick (per class)

● 1 potato

● Tap water

● Paper towels

● 1 disposable dropper pipette (per group)

● Print one Station Instruction Cards, cut the cards, and place at the appropriate station.

● Place materials for each station in a container for easy distribution and storage.

Station 1: Vinegar and Baking Soda

1. Set up station with vinegar and baking soda in separate small beakers or clear plastic cups.

2. Provide a dropper pipette for transferring the vinegar and a wooden coffee stirring stick for transferring the baking soda.

3. Provide a large test tube in a rack for performing the experiment.

Station 2: Steel Wool and Vinegar

1. Tear steel wool into small pieces. Set up station with vinegar in an easy-to-pour bottle and steel wool pieces in a small beaker or clear plastic cup.

2. Provide forceps for handling steel wool.

3. Provide a small beaker or clear plastic cup for the experiment.

4. Provide paper towels for drying the steel wool.

Station 3: Matches with Oxygen (May be performed by teacher as demonstration)

1. Provide one match per group. Do not distribute matches in advance!

Station 4: Effervescent Tablet with Water

1. Break effervescent tablets into small pieces.

2. Set up station with water in an easy-to-pour bottle (or access to faucet) and tablet pieces in a small beaker or clear plastic cup.

3. Provide a large test tube in a rack for performing the experiment.

Station 5: Iodine with Starch

1. Cut potato into thin slices and store underwater.

FACILITATION TIP

Ask: “Why does iodine change color in the presence of starch?”

Reinforce that color change is evidence of chemical change.

2. Provide forceps for handling potato.

3. Provide paper towel to prevent students handling potato after iodine is applied.

4. Provide iodine in a dropper bottle.

5. Caution students that iodine may stain fingers or clothing.

Notes

Planning and Carrying Out Investigations, and Analyzing and Interpreting Data, and Using Mathematics and Computational Thinking

During this activity, students will plan and carry out investigations to explore the phenomenon of phase changes in matter, such as why a solid ice cube melts into liquid water and then disappears into the air as gas. They will identify independent and dependent variables, use appropriate tools to gather data, and analyze and interpret this data to provide evidence for the changes in properties during each phase transition. By testing objects to observe chemical properties, students will gain insights into the molecular interactions and energy changes involved in phase changes, supporting their understanding of the phenomenon.

Procedure and Facilitation

During this activity, students will identify patterns in the rates of change and numerical relationships as they observe chemical reactions, such as the reaction of vinegar with baking soda or steel wool with oxygen. These patterns help them understand the cause and effect relationships at a macroscopic level, which are related to the microscopic and atomic-level structures involved in the changes of state from solid to liquid to gas. Additionally, students will explore how energy transfer drives the motion and cycling of matter, observing that matter is conserved as atoms are rearranged during these chemical processes.

This activity is designed as a laboratory exercise with lab stations.

1. Assign students to five groups.

2. Distribute a Student Journal to each student.

3. Discuss this question: Can you think of other examples of chemical properties? Guide students toward properties such as reaction with acids, reactions with water, tendency to rust, and explosiveness.

4. Go over safety precautions found in the Student Journal.

5. Give groups instructions on rotating.

6. Set a timer and have students rotate every three to five minutes.

Post-Lab Discussion

1. Upon completing the Student Journal, students should have identified chemical properties including reactivity with acids, reactivity with water, rusting, and flammability.

2. At Station 2, the steel wool is not reacting with the vinegar. The vinegar removes the protective coating and allows the iron in the steel wool to react with the oxygen.

3. At Station 4, water is one of the reactants. Students may not realize water can be involved in chemical reactions. Group 1 metals react violently with water. If time permits, you can show students video clips of alkali metals reacting with water.

Notes

Safety Guide

Safety Goggles

When using any form of chemicals, it is safest for students to protect their eyes by wearing goggles.

Gloves

When working with chemicals, students should wear gloves to protect their skin.

Aprons

Have students wear aprons or lab coats when handling chemicals.

Do Not Eat or Drink Materials

Students should be reminded not to eat or drink any materials unless directed to do so.

Do Not Mix Materials

Students should be reminded not to mix materials unless directed to do so.

Roadblock: Unable to Generalize

Students may not be able to generalize the chemical changes seen in this activity to other chemical changes. Identify the parts of the demonstrations that are signs of a chemical change. Compare each to another real-world example and encourage students to think of their own. Speak in terms of analogies or make direct comparisons. Read more strategies for generalization in the Interventions Toolbox.

Notes

Think Time/Talk Time

For beginner and intermediate ELPs, have the materials translated into their native language as a reference for them to use during the activity. Prior to the students completing the activity, say the words and have the students repeat them.

After students complete the Explore lesson, allow them to form groups by numbering off from one to four. Allow them think time to answer the questions in their journals. Then give them talk time to discuss their answers with each other. When you call a number, the student with that number reports for their group.

Possible questions and sentence stems may include the following:

● Level 1 Knowledge Question: How would you describe a chemical reaction?

○ Stem: A chemical reaction is ______.

● Level 2 Comprehension Question: What can you say about a chemical change?

○ Stem: I can say that a chemical change is ______.

● Level 3 Application Question: How would you show your understanding of a chemical property?

○ Stem: I would show my understanding of a chemical property by ______.

● Level 4 Analysis Question: What is the difference between a chemical property and a physical property?

○ Stem: The difference between physical and chemical properties is ______.

● Level 5 Synthesis Question: What facts can you compile to determine whether a chemical reaction has occurred?

○ Stem: I can determine whether a chemical reaction has occurred by ______.

● Level 6 Evaluation Question: How could you use an object’s physical or chemical properties to identify it?

○ Stem: I could use an object’s physical or chemical properties to identify it by ______.

Phenomenon Connection

When observing the transformation of an ice cube from solid to liquid to gas, what chemical and physical changes are occurring, and how do these relate to the chemical reactions observed in the lab activity?

1. How do the chemical reactions observed in the lab (such as vinegar with baking soda or steel wool with oxygen) compare to the physical changes of an ice cube melting and evaporating?

2. In what ways do the properties of substances change during a chemical reaction, and how is this similar or different from the changes in properties when an ice cube melts and evaporates?

3. How can understanding the chemical properties of substances help us predict and explain the changes that occur when an ice cube transitions from solid to liquid to gas?

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

Students plan an investigation to identify four unknown clear liquids as water, alcohol, vinegar, or hydrogen peroxide by testing their properties.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student, group, or class)

● 1 Chemical and Physical Properties (per group)

Reusable

● 9 beakers, 100 mL (per group)

● 3 cups, plastic, 250 mL (per group)

● 1 graduated cylinder (per group)

● 1 balance, triple-beam or electronic scale (per group)

● 1 hot plate (per group)

● 1 thermometer or temperature probe (per group)

● 1 tongs, pair (per group)

● 1 mitts, safety, fire, pair (per group)

● 1 goggles, safety, pair (per student)

● 1 pan, aluminum, round, 9 in. (per group)

● 1 marker, black (per class)

Consumable

● Vinegar, 125 mL (per group)

● Water, 125 mL (per group)

● Alcohol, 125 mL (per group)

● Hydrogen peroxide, 125 mL (per group)

● Salt, 40 g (per group)

● Sugar, 40 g (per group)

● Oil, corn, 37 mL (~40 g) (per group)

● 1 candle (per group)

● 1 matches, box (per group)

● 4 paper, scraps (per group)

● 1 tape, masking, roll (per class)

● Student Journals can be printed individually for student use, printed as a reusable class set, or assigned online.

● Review the Writing a Scientific Explanation Rubric Key for Teacher prior to conducting the CER with students.

● Prepare the four unidentified liquids by pouring 100 mL of each liquid into a separate beaker for each group. Label the beakers as follows: 1 for the water, 2 for the vinegar, 3 for the alcohol, and 4 for the hydrogen peroxide. Plastic cups may be substituted for beakers if necessary.

● The night BEFORE the activity, freeze 25 mL samples of each liquid in beakers, labeled as above, for each group. These will be used to investigate melting point and boiling point of the liquids. Plastic cups may be substituted for beakers if necessary.

● Prepare and label plastic cups of salt, sugar, and corn oil for each group to be used for solubility testing.

● Lay out the rest of the materials and equipment where they can be available for student use as needed throughout the activity.

● Print one Chemical and Physical Properties for each group. Do not distribute until students complete their testing. Students will compare their results to the reference sheet.

During this activity, students will plan and carry out investigations to identify unknown clear liquids by testing their properties, which will help them understand the phenomenon of phase changes in substances like ice melting into water and evaporating into gas. By identifying independent and dependent variables, selecting appropriate tools, and collecting data, students will gather evidence to explain the changes in properties during each phase transition. They will analyze and interpret data to distinguish between causal and correlational relationships, using mathematical and computational thinking to support their conclusions and understand the underlying principles of the phenomenon.

During this activity, students will identify patterns in the properties of different liquids to understand the phenomenon of phase changes in matter, such as why a solid ice cube melts into liquid water and then disappears into the air as gas. By recognizing macroscopic patterns related to microscopic and atomic-level structures, students will explore how energy transfer drives the motion and cycling of matter, and how matter is conserved in these processes. Through their investigation, they will use graphs and charts to identify patterns in data, helping them to understand the cause and effect relationships in natural systems.

1. The following investigation is a sample investigation tightly aligned to the Mississippi College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Science with sample materials, procedures, and anticipated student answers provided.

2. All investigations are inquiry-based, so teachers guide students through differentiated science inquiry events within their comfort level.

3. A set of suggested procedures is given in the Student Journal. These procedures are to be used as an example. You may choose to guide the students in planning their own investigation by going through each of the suggested 10 steps before distributing the Student Journal, or you may have the students plan their investigations using the Student Journal as a guide.

The investigation is written to encourage students to plan and implement their own investigation with your guidance. You can provide appropriate grouping/ differentiated inquiry with the following scaffolding suggestions:

● Group students who need more guided practice together and spend more time with them. Let the other groups work more independently.

● Group students with mixed needs and have them work together. Monitor all groups equally.

1. Probeware may require a data interface to connect to a graphing calculator or computer, so students may need to review how to set up this connection beforehand, as well as find out if any system updates need to be performed.

2. Flammability tests can be done as a teacher demonstration depending on the school/district guidelines for safety in labs and classrooms.

FACILITATION TIP

Many students assume that clear equals water. Pause and highlight that appearance alone is not reliable.

Reinforce that multiple tests are always needed for identification.

Pre-Investigation Discussion

1. We know that pure substances are elements or compounds that cannot be broken down physically into smaller components. We also know that each pure substance has characteristic physical and chemical properties (for any bulk quantity under given conditions) that can be used to identify it. What are some of these properties? Color, density, solubility, and so on

2. If you were given a set of unidentified pure substances, what kind of tests might you do to identify the substances? Test for different properties, such as melting point, boiling point, flammability, observations of color and odor, etc.

3. If you had two unidentified clear liquids, which properties do you think would be most helpful in identifying them and distinguishing them from each other? Odor, boiling point, melting point, density, flammability. These are easy to observe and measure in liquids and would therefore be a good starting point.

FACILITATION TIP

Create a large class chart with columns for each property (odor, solubility, density, etc.). As groups test, ask them to add one observation to the shared tracker. This builds a collective data set and lets students see patterns emerge.

4. Tell the students their challenge is to plan an investigation to identify four clear liquids. They will be given unlabeled samples of water, vinegar, alcohol, and hydrogen peroxide.

Post-Investigation Discussion

1. Which liquid sample did you identify as water? Explain your reasoning. Sample 1; water has a density of 1 g/mL and is odorless.