Published by Accelerate Learning Inc., 5177 Richmond Ave, Suite 800, Houston, TX 77056. Copyright © 2025, by Accelerate Learning Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written consent of Accelerate Learning Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning.

To learn more, visit us at www.stemscopes.com.

Student Expectations

The student is expected to demonstrate an understanding of photosynthesis and the transfer of energy from the Sun into the chemical energy necessary for plant growth and survival, either naturally or artificially.

How do plants turn sunlight into the food and energy they need to grow and survive?

Key Concepts

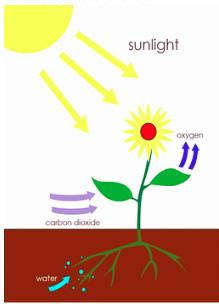

• Plants make their own food through photosynthesis, which combines sunlight, carbon dioxide from the air, and water to make plant food called glucose.

• Radiant energy from the Sun is converted to chemical energy and stored in sugar bonds during the chemical reaction of photosynthesis.

• Environments receive different amounts of direct sunlight, which can impact photosynthesis and plant growth. For example, the tundra does not receive direct sunlight for some parts of the year.

Scope Overview

This unit develops students’ understanding of how sunlight drives photosynthesis and becomes chemical energy for plant growth and survival. Students model light-driven energy transformations, identify roles of roots, stems, and leaves, and track inputs and outputs (water, carbon dioxide, sunlight, sugar, oxygen). They collaboratively construct explanations and visual models, then apply concepts to explain why different plants thrive in different ecosystems based on available light and structural adaptations. Emphasis is on demonstrating energy transfer in natural and artificial contexts.

Scope Vocabulary

The terms below and their definitions can be found in Picture Vocabulary and are embedded in context throughout the scope.

Carbon Dioxide

A gas produced by cells during respiration; used in photosynthesis to produce sugars

Leaf

Part of the plant that is attached to the stem and captures sunlight to make food for the plant

Nutrient Transport

Delivery of nutrients throughout the soil to the plant

Oxygen

A gas produced by plants during photosynthesis that animals use for respiration

Photosynthesis

The process where plants use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to produce sugar and release oxygen

Radiant Energy

Energy from the Sun that reaches Earth as visible light as well as ultraviolet and infrared (heat) radiation

Root

Part of a plant that grows into the ground, absorbs water, and holds the plant in place

Stem

Part of the plant that connects the roots with the leaves and branches; transports water and nutrients

Notes

Students explore how sunlight drives photosynthesis by modeling photosensitivity with light-sensitive paper.

• Elicit prior knowledge about plant energy needs and sunlight.

• Construct two identical masked samples on light-sensitive paper and expose one to direct light, the other to indirect light.

• Observe and record differences in image development to compare effects of light exposure.

• Discuss the energy transformation evidenced by the paper’s change and relate it to photosynthesis in plants.

Students investigate how plant structures support photosynthesis and communicate their understanding collaboratively.

• Read informational text to identify roles of roots, stem, and leaves in photosynthesis, including inputs and outputs (water, carbon dioxide, sunlight, sugar, oxygen).

• Work in groups to create a visual diagram/anchor chart of the process, labeling key terms and explaining each part’s function.

• Share products, conduct a gallery walk to compare representations, and discuss observations as a class.

• Co-create a class anchor chart synthesizing learning and record it in student journals.

Activity - Photosynthesis in Different Environments

Students investigate how plant structures, climate, and photosynthesis determine which plants thrive in different ecosystems.

• Work in pairs or small groups to research the rain forest and tundra, including direct vs. indirect sunlight.

• Use prior knowledge, research sources, and provided plant images to record findings.

• Sort plant images by the ecosystem where they would survive and justify placements with evidence about structures, climate, and photosynthesis.

• Discuss and compare reasoning with peers to refine understanding.

Estimated 30 min - 45 min

In this activity, students are introduced to photosynthesis by using light-sensitive paper to mimic the photosensitivity of chlorophyll in plants.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Introduction to Photosynthesis (per class)

Reusable

● 1 pair of scissors (per group)

Consumable

● 1 piece of 5" x 7" paper, lightsensitive (per group)

● ¼ piece of 8.5" x 11" black construction paper (per group)

● 1 piece of masking tape, 30 cm (per group)

● 1 lab journal (per student)

SEP Connection

● Light-sensitive paper can be ordered from teacher supply and science supply companies. Light-sensitive paper can typically be ordered in 5” x 7” sheets.

● Read the instructions that accompany your light-sensitive paper. Some brands of light-sensitive paper require that the exposed paper is rinsed and allowed to dry for full development. If needed, plan for students to rinse the exposed, light-sensitive paper under water, and provide a place for the papers to dry so that the images can develop prior to making observations.

● Cut the 8.5” x 11” sheets of black construction paper into quarters so that each group receives a 4.25” x 5.5” piece.

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will obtain and combine information from their observations of light-sensitive paper to explain the phenomenon of how plants turn sunlight into food and energy. They will evaluate the merit and accuracy of their observations by comparing the effects of direct and indirect sunlight on the paper, and communicate their findings through written formats in their lab journals, thereby engaging in scientific practices.

CCC Connection

Energy and Matter

Systems and System

During this activity, students will explore the phenomenon of how plants turn sunlight into food and energy by using light-sensitive paper to mimic the photosensitivity of chlorophyll in plants. This will help them understand the concept of energy and matter by observing how radiant energy from the Sun is transformed into chemical energy, similar to the process of photosynthesis. Additionally, students will learn about systems and system models by examining how different components (light, paper, and designs) interact to produce observable changes, reflecting how plants function as systems to utilize sunlight for growth and survival.

Notes

1. Begin the activity by having a discussion with students. If students are unsure of the answers, consider projecting the Introduction to Photosynthesis document and discussing in partners, small groups, or as a class. Ask the following questions:

● What is the source of energy plants need to grow? The Sun

● What else do you think plants need in order to utilize the Sun’s light? Accept all answers. Possible answers include water, carbon dioxide, and soil.

● Does the amount of sunlight change how a plant grows? Accept all answers. Yes, more sunlight will make a plant grow more.

● Do all plants look similar regardless of their environment? No, the environment/amount of sunlight dictates the specific adaptations of a plant (size of leaves, height, etc.).

2. Pass out the light-sensitive paper and black construction paper pieces to student groups.

3. Have students cut the light-sensitive paper in half.

4. Have students cut two similar designs out of their ¼ piece of black construction paper.

5. Pass out tape to students and have them tape one created black design onto each of the two halves of light-sensitive paper. Demonstrate that the tape must be rolled and placed on the back of the design and then pressed firmly onto the light-sensitive paper.

6. Place one of the pieces of light-sensitive paper in direct sunlight or under a sunlamp for 15 minutes. Place the other light-sensitive paper in an area that does not receive direct sunlight or direct lamplight, such as under a tree or under a table.

7. After 15 minutes, ask students to remove the taped-on black paper designs from the light-sensitive paper.

8. Ask students to record their observations in their lab journals.

Notes

FACILITATION TIP

Show students how to cut, tape, and place the paper before handing out supplies. A quick demo prevents wasted materials.

FACILITATION TIP

Encourage students to describe not only what they see, but also how the two pieces of paper differ (contrast words like darker/ lighter, sharper/fuzzier, stronger/weaker).

9. Review the activity as a class using the following discussion questions:

● What energy transformation took place in this activity? Radiant energy from the Sun was transformed to chemical energy in the paper.

● How do you know this transformation occurred? The paper changed color only where the sunlight touched the paper.

● Did the transformation still occur in indirect light? How was it different? Yes, the transformation still occurred, but the image was not as dark, clear, or defined.

● How do you think this activity relates to the use of sunlight by plants? Accept all answers. Lead students to the conclusion that sunlight drives photosynthesis, so plants that are in areas with lower amounts of direct sunlight make less food and appear different from plants that are in direct sunlight.

Some students may have difficulty cutting out various shapes from the paper. Provide precut shapes for students to select from for this activity. Find more strategies to assist students who have difficulty with fine motor control in the Interventions Toolbox.

How do plants use sunlight to transform energy into food, and what factors affect this process?

1. Based on your observations, how does the amount of sunlight exposure affect the energy transformation in plants?

2. If plants were placed in an environment with limited sunlight, how might their growth and energy production be impacted?

3. In what ways can plants adapt to varying levels of sunlight to ensure they continue to produce the energy they need?

Notes

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

Students research how plant parts contribute to the process of photosynthesis. Students communicate what they learn by creating a group diagram displaying the process of photosynthesis and the function of each plant part.

Materials

Printed Materials

● 1 What Is Your Job? (per student or per group)

Reusable Materials

● Scissors (as needed)

● Colored pencils (per group)

● Crayons (per group)

● Glue (as needed)

● Student Journals

Consumable Materials

● 1 piece of chart paper (per group)

● Colored construction paper (as needed)

SEP Connection

● Make sure student reference guides and supplies are accessible to all students.

● Consider doing a virtual photosynthesis lab before or after this activity. Several are available by typing “fifth grade virtual photosynthesis lab” into an online search.

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information by researching how plant parts contribute to the process of photosynthesis. They will read and comprehend complex texts to summarize and obtain scientific ideas, using evidence to support their understanding of how plants turn sunlight into the food and energy they need to grow and survive. Students will create a group diagram to visually communicate the process of photosynthesis, comparing and combining information from reliable sources, and presenting their findings through various media formats such as charts and diagrams.

Notes

CCC Connection

Energy and Matter Systems and System

During this activity, students will explore how plants convert sunlight into food and energy, enhancing their understanding of the conservation of matter and energy transfer. By creating diagrams of photosynthesis, students will observe how matter flows and cycles within the system of a plant, recognizing that the total weight of substances remains constant. They will also describe the plant as a system, identifying how its components—roots, stem, and leaves—interact to perform functions that individual parts cannot achieve alone.

1. Distribute What Is Your Job? to each student/group.

2. Explain to students that they are to read the information and create a diagram in groups that uses the information. Groups should use the large chart paper to create an anchor chart. Words that are in bold print in the text of the What Is Your Job? page must be labeled on the diagram groups make and should have a brief explanation written for its role in photosynthesis.

3. Explain that students may use construction paper, colored pencils, and crayons to make their charts.

4. Have groups share their finished products and hang their chart papers around the classroom. Allow students to do a gallery walk to look at how other groups have displayed the information.

5. Come together as a class to discuss what students saw during their gallery walk. Use the discussion to create a classroom anchor chart that students should then copy into their journals.

6. Discuss the following:

○ What did you discover is the role of the roots? They take in water and anchor the plant.

○ What is the role of the stem? The stem provides structure to the plant and transports water and nutrients between the roots and the leaves.

○ What is the role of the leaves? The leaves absorb sunlight and carbon dioxide and combine them with water from the roots to create a chemical reaction that produces sugar and oxygen.

○ What does the plant do with the sugar it produces? The plant uses the sugar for energy.

○ What happens to the oxygen created during photosynthesis? The plant releases the oxygen as waste.

○ Do you think the size of the leaf determines the amount of food the plant can make? Yes, larger leaves can absorb more sunlight and will therefore produce more food. Plants in the shade often have larger leaves to absorb whatever sunlight is available, whereas plants in the desert often have needlelike leaves so they do not absorb too much sunlight.

Possible teacher anchor chart:

To help check for misconceptions, ask students, “Where do plants get their food?” Many students will say soil. Address this upfront by explaining that plants get minerals from soil, but their actual food (sugar) comes from photosynthesis.

Provide a short checklist for groups to review before presenting:

Did we include all bold words?

Did we explain the role of each part?

Did we show how water, carbon dioxide, and sunlight move?

Research Presentation Strategies

After the research activity, students can create a presentation to share what their research found.

● Give students time to practice their presentations in front of smaller groups before presenting to the whole class.

● Give students specific ideas on what to speak about ahead of time. Have students use note cards to outline the major talking points of the research and refer to them during their presentations.

How do the different parts of a plant work together to convert sunlight into energy?

1. Based on your observations, how does the structure of a leaf contribute to its ability to absorb sunlight and facilitate photosynthesis?

2. If a plant’s roots were unable to absorb water efficiently, how might that impact the plant’s ability to perform photosynthesis?

3. How does the process of photosynthesis in plants compare to the way animals obtain energy?

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

Students work in partners or groups to research why differences in plant types exist between two environments. They then sort plant pictures and come up with an explanation for which environment the plant would belong in. Explanations should relate to plant structures, climate, and photosynthesis.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per partner or group)

● 1 Student Handout (per partner or group)

Reusable

● Scissors (per teacher)

● Plastic bag (per group)

● Research materials such as trade books, textbooks, etc. (optional)

● Access to an Internet-capable device such as a computer, tablet, or phone (optional)

● Print plant pictures, in color if possible, for each group or set of partners. Precut the plant pictures and place them in a bag, or allow students to cut the pictures apart within their groups.

● Gather research materials or Internet-ready devices.

● Consider previewing and bookmarking sites for your students based on the column headers. Students will need to visit multiple websites to collect all information on the chart. You may need to explain the difference between direct and indirect sunlight (as it falls on Earth's surface in equatorial latitudes vs far northern and southern latitudes).

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to explain the phenomenon of how plants turn sunlight into the food and energy they need to grow and survive. By researching plant types in different environments, students will read and comprehend complex texts and reliable media to summarize scientific ideas, compare information across sources, and communicate their findings through explanations that relate to plant structures, climate, and photosynthesis.

Notes

Energy and Matter Systems and System

During this activity, students will explore how plants turn sunlight into food and energy by examining the differences in plant types between two environments. They will use their understanding of energy and matter to track how energy from sunlight is captured and transformed through photosynthesis, and they will apply systems and system models to describe how plant structures and environmental factors interact to support plant survival in different ecosystems.

1. Place students in pairs or small groups.

2. Tell students that they are to research the types of plants that are found in the rain forest and the tundra and the amount of direct sunlight each ecosystem receives.

3. Tell students they are to use their prior knowledge, the provided pictures, and their research to complete the Student Journal page.

4. After student groups have completed their Student Journal pages, direct them to use their knowledge to sort the plant pictures from the Student Handout page into those that could live in the tundra and those that could live in the rain forest. Answers: Tundra: 1, 4, 6, 8; Rain forest: 2, 3, 5, 7

5. Have students discuss why a plant was placed in a specific environment. Amount of direct sunlight used, photosynthesis determining size, rainfall amounts, growing season, environmental conditions, etc.

6. After the sort, you may need to lead a class discussion that allows students to share their thinking about why a picture was placed in a specific environment. Clear up any misconceptions, and use the discussion to reiterate the connections between photosynthesis, plant structure, and climate.

This activity is a closure technique that encourages students to reflect upon the content of the recently completed lesson. It can be completed as a class, with a peer, or individually via a journal entry.

Write the following acronym on the board, or display it using a document camera:

C: Communicate what you have learned.

R: React to what you have learned.

O: Offer one sentence that sums up the lesson or activity.

W: Way you can use what you have learned.

N: Note how well you did today.

Have students complete a short writing exercise about the lesson using the CROWN technique.

How do the differences in environmental conditions, such as sunlight and climate, influence the way plants perform photosynthesis and adapt to their surroundings?

1. How does the amount of sunlight in the rain forest compared to the tundra affect the photosynthesis process in plants found in these environments?

2. In what ways do plant structures differ between those adapted to the rain forest and those adapted to the tundra, and how do these differences support their survival and growth?

3. How might changes in climate impact the ability of plants in both the rain forest and tundra to convert sunlight into food and energy?

FACILITATION TIP

Have students pause mid-sort to check their reasoning with another group before finalizing. This reduces random guesses and promotes justification.

FACILITATION TIP

Turn the final sort into a class chart on the board or projector. Groups can place their plant pictures in two columns, and the class can vote/discuss placements.

STEMscopedia

Reference materials that includes parent connections, career connections, technology, and science news.

Linking Literacy

Strategies to help students comprehend difficult informational text.

Picture Vocabulary

A slide presentation of important vocabulary terms along with a picture and definition.

Content Connections Video

A video-based activity where students watch a video clip that relates to the scope’s content and answer questions.

Career Connections - Arborist

STEM careers come to life with these leveled career exploration videos and student guides designed to take the learning further.

Math Connections

A practice that uses grade-level appropriate math activities to address the concept.

Reading Science - Thanks, Leaves!

A reading passage about the concept, which includes five to eight comprehension questions.

Notes

Multiple Choice Assessment

A standards-based assessment designed to gauge students’ understanding of the science concept using their selections of the best possible answers from a list of choices

Open-Ended Response Assessment

A short-answer and essay assessment to evaluate student mastery of the concept.

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

An assessment in which students write a scientific explanation to show their understanding of the concept in a way that uses evidence.

Guided Practice

A guide that shows the teacher how to administer a smallgroup lesson to students who need intervention on the topic.

Independent Practice

A fill in the blank sheet that helps students master the vocabulary of this scope.

Extensions

A set of ideas and activities that can help further elaborate on the concept.

Use this template to decide how to assess your students for concept mastery. Depending on the format of the assessment, you can identify prompts and intended responses that would measure student mastery of the expectation. See the beginning of this scope to identify standards and grade-level expectations.

Student Learning Objectives What Prompts Will Be Used?

Plants make their own food through photosynthesis, which combines sunlight, carbon dioxide from the air, and water to make plant food called glucose.

Radiant energy from the Sun is converted to chemical energy and stored in sugar bonds during the chemical reaction of photosynthesis.

Environments receive different amounts of direct sunlight, which can impact photosynthesis and plant growth. For example, the tundra does not receive direct sunlight for some parts of the year.

Does Student Mastery Look Like?

Student Expectations

The student is expected to demonstrate an understanding of a healthy ecosystem with a stable web of life and the roles of living things within a food chain and/or food web using models that include producers, primary and secondary consumers, and decomposers.

Student Wondering of Phenomenon

What would happen to a forest if all the insects suddenly disappeared?

Key Concepts

• Earth’s environments can be classified into a variety of ecosystems, including freshwater, marine, desert, forest, grassland, and tundra. These unique ecosystems support different varieties of organisms.

• Food chains diagram the transfer of energy as it flows from the Sun to producers (plants), to primary consumers (herbivores), to secondary consumers (carnivores that eat herbivores), and on to tertiary consumers (carnivores that eat carnivores).

• Food webs diagram the complex relationships of energy flow in an ecosystem containing a variety of producers, consumers, and decomposers.

• The removal or addition of an organism in a food chain can affect other organisms.

• Environmental changes, such as deforestation, disease, human activities, and invasive species, bring changes in resources that will cause some organisms or populations to perish or move while permitting other organisms or populations to thrive.

Scope Overview

This unit develops students’ understanding of how energy from the Sun drives interactions among producers, consumers, and decomposers within stable ecosystems. Through observation, research, and modeling, students identify abiotic and biotic components, build and compare food chains across ecosystems, and extend them into food webs to show multiple energy pathways. Simulations make energy transfer and trophic dynamics visible, including the effects of disturbances and human-driven changes. Students use evidence from their models to explain organism roles, predict cascading impacts, and describe characteristics of a healthy, stable web of life.

Scope Vocabulary

The terms below and their definitions can be found in Picture Vocabulary and are embedded in context throughout the scope.

Consumer

An organism that gets energy from eating plants or animals

Decomposer

An organism that breaks down the remains of dead plants or animals without need for internal digestion

Ecosystem

All living and nonliving things and all their interactions in an area

Energy Transfer

The movement of energy from one object or material to another or from one form to another

Environment

The space, conditions, and all the living and nonliving things around an organism

Food

What plants and animals use for energy; plants create their own using energy from the Sun, while animals must eat

Food Chain

The path of food energy from one organism to another in an ecosystem

Food Web

An interconnected set of food chains

Fungus

A type of organism that can break down just about any type of organic matter and can be large, such as a mushroom, or small, such as tiny pieces of mold

Niche

The role an organism plays in its ecosystem

Population

All the interacting members of a species in a single area

Producer

An organism that uses sunlight to make its own food for energy

Thrive

To grow well or strong

Students investigate ecosystem components and energy flow through observation and discussion.

• Observe an ecosystem (outdoors or projected) and catalog living and nonliving components.

• Discuss the role of abiotic factors (Sun, water, soil) and how living things interact.

• Construct simple food chains, emphasizing producers, consumers, decomposers, and energy flow from the Sun.

• Extend a class-created chain into a basic food web to show multiple energy pathways within the ecosystem.

Students investigate ecosystems and demonstrate energy transfer by building and comparing simple food chains.

• Students form groups by matching organism cards from the same ecosystem and research key ecosystem facts to complete their journals.

• Groups sequence organisms to model energy flow, starting with the Sun, and use arrows to show transfer from producers to consumers.

• Students create complete food chains for multiple ecosystems (e.g., pond, ocean, tundra, desert) and display their models.

• Class conducts a gallery walk and debrief to compare patterns across ecosystems and reinforce the role of the Sun, producers, and consumers.

Making a Model - Food Web

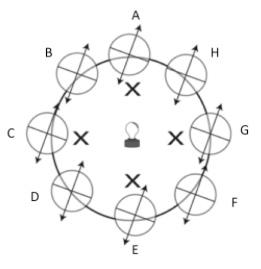

Students simulate energy flow in a food web to understand how energy moves from the Sun through producers to various consumers and how disruptions affect ecosystems.

• Assume roles (Sun, producers, consumers, decomposers) and model energy transfer using colored squares while “feeding” according to realistic food web interactions.

• Track gains/losses of energy; students who lose all energy become observers, while decomposers address organisms that have “died.”

• Play multiple rounds, including scenario-based disturbances (e.g., fire), to see how changes ripple through trophic levels.

• Discuss outcomes and record observations to connect the simulation to real-world processes like photosynthesis, consumer levels, and the water cycle’s role.

Students model energy flow in a rainforest ecosystem and use it to predict how human-driven changes alter organism interactions and populations.

• Construct and annotate a rainforest food web from organism images, identifying producers, consumers, and decomposers and tracing energy with arrows.

• Extract sample food chains from their webs and record them, reinforcing trophic relationships and energy transfer.

• Participate in a space-based simulation of habitat fragmentation (ranches/roads) and analyze environmental change scenarios— including an invasive species—to predict cascading effects on organisms using evidence from their food webs.

30 min - 45 min

Students observe an ecosystem and determine its living and nonliving components. They make connections between the various parts and are guided toward identifying food chains and food webs, with an emphasis on producers, primary and secondary consumers, and decomposers.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Parts of an Ecosystem (per student)

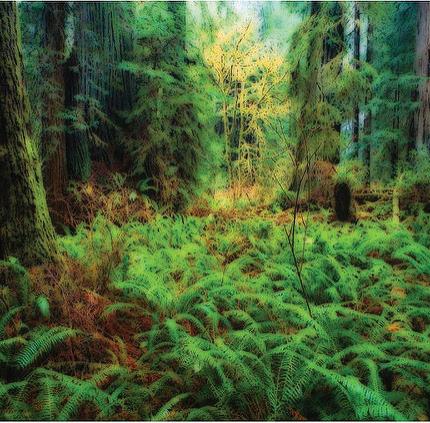

● 1 Forest Ecosystem (per class)

If you are unable to take the class outside or observe from a window, project the Forest Ecosystem for students to see.

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information Developing and Using Models

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information by observing an ecosystem to identify its living and nonliving components, and they will develop and use models to describe and predict the impact on the ecosystem if all insects were to disappear. By building and revising simple models of food chains and food webs, students will explore the relationships among producers, consumers, and decomposers, and communicate their findings through diagrams and discussions, thereby explaining the phenomenon of the potential consequences on a forest ecosystem in the absence of insects.

Notes

Energy and Matter

Stability and Change

During this activity, students will explore the phenomenon of what would happen to a forest if all the insects suddenly disappeared by observing an ecosystem and identifying its living and nonliving components. They will make connections between these components, focusing on food chains and food webs, to understand the flow of energy and matter. This will help them grasp the concept of energy transfer and the conservation of matter, as well as observe stability and change within the ecosystem over time.

1. View an ecosystem with your students by either going outside or projecting the Forest Ecosystem.

2. After viewing the ecosystem, have students list the things that they see on their Parts of an Ecosystem documents, deciding what is living and nonliving. Discuss the observations as a class.

3. Discuss how the Sun, water, soil, and other nonliving items are important to the health of the ecosystem.

4. Have students discuss how living things interact.

5. Guide students toward starting to build simple food chains. Discuss that energy flow for food is called a food chain, and all energy originally comes from the Sun. Write the words for each food chain on the board, and discuss that the direction the arrow is pointing is the direction the energy is flowing. Have students copy two examples in their Parts of an Ecosystem documents.

○ Examples:

○ Sun - Grass - Rabbit

○ Sun - Shrub - Deer - Bear

6. Aid students in identifying and understanding key vocabulary on the back of their Parts of an Ecosystem documents.

7. Using one of the food chains you have created with students, discuss whether more than one animal in that ecosystem might eat that same plant (for example, the deer and rabbit may both eat the grass in the forest picture). Writing the words and arrows on the board, show how energy would be transferred from the grass to both the deer and the rabbit. Explain that this is how a food web would be created for an ecosystem, and continue to develop the web by having students provide more examples of ways in which energy is transferred to more than just one organism throughout that ecosystem. Students do not need to copy this information down in their Parts of an Ecosystem documents; this is simply a basic introduction to the concept of food webs, which will be developed further in an Explore activity.

Phenomenon Connection

If insects were to suddenly disappear from a forest, how would this impact the food chains and food webs within that ecosystem?

1. How would the absence of insects affect the roles of producers, primary consumers, and secondary consumers in the forest ecosystem?

2. In what ways might the disappearance of insects influence the nonliving components of the ecosystem, such as soil and plant growth?

3. How could the loss of insects alter the interactions between different species within the food web, and what might be the long-term consequences for the forest ecosystem?

FACILITATION TIP

Activate prior knowledge by asking students, “What do you need to stay alive every day?” (food, water, shelter, energy). Then connect to what plants and animals in an ecosystem need.

FACILITATION TIP

Remind students that the arrow does not mean “eats” but “energy flows to.” This helps prevent the common misconception of “grass eats the Sun.”

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

In this activity, students research various ecosystems and the organisms that can inhabit them, and then they identify the flow of energy within those environments by creating basic food chains with sample organisms.

Materials

Printed

• 1 Student Journal (per student)

• 1 Food Chain Cards (per class)

• 1 Food Chain Arrows (per class)

Reusable

• Small yellow paper plates (per group)

• Device with Internet access (per group)

• Print and cut out (laminate if you want to keep) enough Food Chain Cards and Food Chain Arrows so that each student may have one. Students are tasked with locating the other organisms that belong in their ecosystems. To help students locate other organisms in their ecosystems, you might want to color-code the cards or place different-colored dots on the back of each card set (e.g., a blue dot on the back of the tundra cards, a red dot on the back of the rain forest cards).

• Cut out Food Chain Arrows (four arrows per food chain and one per student).

SEP Connection

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information Developing and Using Models

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information by researching various ecosystems and the organisms within them to create basic food chains. They will read and comprehend complex texts and reliable media to summarize scientific ideas supported by evidence. Students will also develop and use models by creating food chains to represent the flow of energy in ecosystems, using models to describe and predict the impact of phenomena such as the disappearance of insects on a forest ecosystem. Through this process, they will communicate their findings orally and in written formats, using diagrams and charts to convey their understanding of energy transfer and ecosystem dynamics.

• Scissors (per teacher) Notes

Connection

During this activity, students will explore the flow of energy and matter within ecosystems by creating food chains, which will help them understand the conservation of matter and energy transfer. This will allow them to observe how the disappearance of insects could disrupt these cycles and lead to changes over time, illustrating the concepts of stability and change within ecosystems.

1. Randomly pass out one Food Chain Card to each student. Make sure to use at least the first three cards from each ecosystem.

2. Give students time to find the other two to three members of their ecosystems. This will be their group.

3. Have students work within their groups to research basic facts about their ecosystem using the Internet. Direct them to fill out the Student Journal page as they research. Use the Student Journal Key as a guide to possible answers.

4. When students have completed their research and the questions in their Student Journals, have groups use their organism cards to put the organisms in an order that could illustrate the transfer of energy in their ecosystem.

5. Distribute a yellow paper plate to each group. Identify the plate as a representation of the Sun. Make sure all students start their chains with the yellow paper plate.

6. Instruct students to determine the flow of the Sun’s energy based on what the organisms consume to gain energy.

7. Pass out paper arrows to each group. Have students use the arrows to connect the organism pictures together. Students should understand that when an organism is eaten, it is passing energy on to the predator. All arrows in a food chain should point away from the Sun and toward the organism that is doing the eating.

○ Key for food chains in each ecosystem:

○ Pond: Algae - Tadpole - Fish - Kingfisher

○ Ocean: Algae - Shrimp - Squid - Whale

○ Tundra: Arctic moss - Arctic hare - Arctic fox - Polar bear

○ Desert: Cactus - Mouse - Snake - Hawk

○ Prairie: Flower - Butterfly - Lizard - Cougar

○ Rain forest: Ferns - Grasshopper - Tree frog - Jaguar

○ Saltwater marsh: Trees (roots) - Fish - Crab - Pelican

8. Explain to students that they have just created a complete food chain that shows the transfer of the Sun’s energy to plants and then on to animals within their ecosystem. Once all of the food chains are created, have groups lay their cards down on their tables.

9. Have students go on a gallery walk to see the other food chains, meeting back with their groups at the end of the walk to discuss the similarities and differences they noticed.

10. Lead students to understanding by discussing the following questions after the gallery walk:

○ What is the source of energy for all life on Earth? How do you know? The Sun. It is the beginning of all the food chains.

○ What type of organism is always found next to the Sun in a food chain? Why? Plants. All plants must receive energy from the Sun to make food.

○ Why did we include arrows in our food chains? The arrows show how energy is transferred from one thing to another, from the Sun to plants to animals in our ecosystem.

Provide a short list of teacher-approved student-friendly websites or a fact sheet with key organisms from each ecosystem. This prevents wasted time on aimless searching and helps ensure accuracy in the Student Journal.

If needed, use a whole class model.

Turn the food chain into a physical model: assign each student a role (Sun, producer, consumer, predator) and have them stand in order holding arrows between them. This kinesthetic approach reinforces the direction of energy transfer.

○ What are some similarities you noticed between the food chains in the different ecosystems? The food chain in each ecosystem always began with the Sun’s energy followed by a plant. Animals that eat plants came next (primary consumers), followed by an animal that could eat another animal (secondary consumer).

○ Would you be able to find the same food chain from one ecosystem within a different ecosystem? Each ecosystem’s food chain has animals that are adapted to live within that specific ecosystem. You would not be able to create a food chain consisting of tree roots > fish > crab > pelican within a prairie ecosystem, for example, because not all of those animals would be able to survive there. There might be tree roots and fish within a prairie pond, but these would be followed in a food chain by a different secondary consumer because crabs and pelicans would not be found living in a prairie ecosystem.

Card

Through this card sort, students demonstrate an understanding of the relationships in a food web.

Create a set of cards that have different vocabulary terms from this scope. Examples include food chain, food web, decomposers, producers, consumers, saltwater and freshwater ecosystems, desert ecosystems, grassland ecosystems, forest ecosystems, rain forest ecosystems, polar tundra ecosystems, or any other related vocabulary terms. Make a matching set of cards with nonlinguistic representations of these terms, such as images. Make enough matching sets for students to work in groups of two.

Have students work with a partner to match the vocabulary terms with their representations. Allow time for students to discuss their choices with other pairs.

When considering the role of insects in a forest ecosystem, how does their disappearance impact the flow of energy and the overall food chain?

1. How do insects contribute to the energy flow within a forest ecosystem, and what might happen to the food chain if they were removed?

2. In what ways do insects support the survival of other organisms in a forest, and how might their absence affect these organisms?

3. How can understanding the role of insects in a forest ecosystem help us predict changes in biodiversity and ecosystem stability if they were to disappear?

Notes

Estimated 1 hr - 2 hrs

In this activity, students play a role in the food web as either a producer or consumer.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Guide (per group)

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 set of Character Role Cards (per class)

● 1 set of Situation Cards (per class)

Reusable

● 3" x 3" colored paper squares: green, orange, yellow, red, brown (one set per class)

● Drawing paper (per student)

● Crayons or markers (per student)

● Scissors (per student)

● Sandwich-sized plastic bag (per student)

● Decide on an area large enough for free movement, such as a gymnasium or a playground.

● Print and copy the Character Role Cards on card stock. To model the energy pyramid, you should have more producers than herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores. You should have fewer herbivores and omnivores and the least amount of carnivores. For example, 24 students would yield 12 producers, 4 herbivores, 4 omnivores, 3 carnivores, and one Sun. All other students should be made decomposers.

● Cut colored squares: 24 yellow squares (so the Sun can give to producers; the Sun should give more after producers are partially eaten), 4 orange (each herbivore gives one to its consumer), 4 brown (each omnivore gives one to its consumer), 3 red (each carnivore gives one to its consumer), and 24–36 green (producers each have 2–3).

● Note that producers get a greater number of green squares because they can give many squares out without dying. They get additional yellow energy squares because unless they are completely destroyed, they continue to produce food. Consumers have one square each because if they are eaten, they die. Decomposers can be given an area and can go get the students that are producers or consumers that have died.

● Cut out situation cards. Sample student answers can be printed if needed.

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information Developing and Using Models

During this activity, students will engage in obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information by reading and comprehending complex texts and other reliable media to summarize and obtain scientific ideas about the phenomenon of what would happen to a forest if all the insects suddenly disappeared. They will compare and combine information to support their engagement in scientific practices, obtaining and combining information to explain the phenomenon. Additionally, students will develop and use models to describe and predict the effects on the food web, identifying limitations of models and using them to test cause and effect relationships concerning the functioning of the forest ecosystem.

During this activity, students will explore the concept of energy and matter by observing how the disappearance of insects affects the flow of energy and matter within a forest ecosystem. They will track the transfer of energy from the Sun to producers and through various levels of consumers, recognizing the conservation of matter and the impact on stability and change within the ecosystem. By simulating the roles of producers, consumers, and decomposers, students will measure changes over time and understand how the absence of insects can disrupt the balance and stability of the forest system.

1. Give a Character Role Card and plastic bag to each student. The plastic bag will be students' animals’ “stomachs.” Allow time for students to draw a picture of the animal/plant they received in their Student Journals.

2. Have one student read the procedures. Explain that yellow squares represent the Sun’s energy, so they are passed along from producers to consumers and to other consumers as they eat. Plants are producers and can give out many green squares without dying because they are renewable. Animals are consumers and have only one square because when they are eaten they are no longer living.

3. Ask students to predict what will happen to the food energy squares as the game progresses.

4. Remind students to be as realistic as possible in regard to what consumers would want to eat. For example, a human omnivore would not eat a carnivorous spider.

5. Begin by giving the Sun time to give yellow energy squares to each producer. Producers must stand in place. They cannot change locations to avoid being eaten.

6. Explain the following:

○ Producers give one yellow square (Sun) and one green square to each herbivore or omnivore that eats them.

○ Herbivores get yellow and green squares from producers and give their orange and yellow squares to the omnivores or carnivores that eat them.

○ Omnivores get yellow, green, brown, and red squares from plants and animals that they eat and give their brown and yellow squares to the omnivores or carnivores that eat them.

○ Carnivores get yellow, brown, and red squares from animals that they eat and give their red and yellow squares to the omnivores or carnivores that eat them.

7. Explain that when a student’s energy squares are gone, he or she becomes an observer and must sit out.

8. Continue the game as each member of the forest ecosystem finds food. As the game progresses, the Sun continues to give yellow energy squares to producers who lose theirs to consumers. At some point, the food web will no longer be viable, and no more squares can be given to eligible receivers.

Use cones, chalk, or tape to section off the play area into “zones” (e.g., Sun zone, producers’ zone, decomposers’ corner). This keeps the game more structured.

9. After the first round of play, facilitate a student discussion with guided questions to make connections to the natural world. Focus on the transfer of the Sun’s energy.

Check for Understanding with Quick Stops. Pause mid-game for a 1–2 minute “energy status check” where students look into their baggies and explain who they got energy from. This helps reinforce the flow of energy in real time.

○ Where are the yellow energy squares at the end of the game? What is the significance of this? All of the Sun’s energy has been transferred from the Sun to the producers and then to herbivores/omnivores, and it ends up with carnivores/omnivores. This is how the Sun’s energy moves through organisms within a food chain.

○ What do producers need to make their own food? They need energy from the Sun, water, and carbon dioxide.

○ How does the water cycle affect the flow of energy? Plants rely on the evaporation, condensation, and precipitation of water to make food through photosynthesis.

○ What was the role of the decomposers? The decomposers break down plants and animals that have died within the food web.

○ Who were the primary consumers? Were there secondary consumers? The primary consumers were the herbivores and any of the omnivores that ate plants. The secondary consumers were all of the carnivores and any omnivores that ate animals.

10. Before the second round, be sure that each student has identified himself or herself as a consumer, producer, or decomposer and have explained what that means.

11. Use a Situation Card, or allow students to agree on a new situation that introduces a negative change to the ecosystem. For example, a forest fire destroys half of the producers. Those affected should sit out and observe. After the second round, guide students to identify the effects caused by the change.

12. Play more rounds using the Situation Cards. Discuss the effects.

13. Have students record their observations in their Student Journals.

This activity can cause some students to become overly excited due to the new environment or the movement involved. Encourage students to think before they act and consider the results of their actions. Provide a location for students to remove themselves and pause if they become overexcited during the activity. Read more strategies for overstimulation in the Intervention Toolbox.

Notes

QSSS: Question, Signal, Stem, Share Question: *Please see below.

Signal: When you are finished answering the question, stand behind your seat. Stem: *Please see below.

Share: The tallest student will begin. Possible questions and sentence stems include the following:

● How would you explain a food chain?

○ Stem: I would explain a food chain by _______ .

● What are the differences between producers, consumers, and decomposers?

○ Stem: The differences between producers, consumers, and decomposers are _______ .

● Can you make a distinction between primary and secondary consumers?

○ Stem: A distinction between primary and secondary consumers is ________ .

● How would you improve a 2-D drawing of a food web?

○ Stem: I would improve a 2-D drawing of a food web by ________ .

In the activity, students explore the roles of producers, consumers, and decomposers in a food web. Considering this, what would happen to a forest ecosystem if all the insects, which are key consumers and decomposers, suddenly disappeared?

1. How would the disappearance of insects affect the energy flow from producers to higher-level consumers in the forest ecosystem?

2. What impact would the loss of insects have on the decomposition process and nutrient cycling within the forest?

3. How might the absence of insects influence the survival and reproduction of plant species that rely on insects for pollination?

Notes

Estimated 2 hrs - 3 hrs

Students design and interpret a food web within an ecosystem and then use the food web to predict the changes that will occur to organisms in the ecosystem due to human impact.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 Environmental Changes (per class)

● 1 Food Web Pictures (per group)

● 1 Teacher Slide (per class)

● 1 Teacher Guide Key (for teacher)

Reusable

● Glue stick (per group)

● Scissors (per group)

Consumable

● Blue painter’s tape (per class)

● 1 sheet of large chart paper (per group)

Preparation

● For Part I, print a set of Food Web Pictures for each group.

● For Part II, tape off an area large enough for students to stand in comfortably without touching.

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information Developing and Using Models

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information by designing and interpreting a food web within an ecosystem to predict changes that will occur to organisms if all insects suddenly disappeared. They will read and comprehend complex texts and reliable media to summarize scientific ideas, compare and combine information to support scientific practices, and communicate their findings through various formats. Additionally, students will develop and use models to represent the relationships within the food web, identify limitations of these models, and use them to describe and predict the effects of the disappearance of insects on the forest ecosystem.

Notes

Energy and Matter Stability and Change

During this activity, students will design and interpret a food web within an ecosystem to predict the changes that will occur to organisms due to human impact, thereby exploring the phenomenon of what would happen to a forest if all the insects suddenly disappeared. This exploration will help students understand the concepts of energy and matter by observing how energy is transferred between organisms and how matter cycles within the ecosystem. Additionally, students will measure stability and change by observing how the disappearance of insects can lead to changes in the ecosystem over time, affecting the balance and stability of the food web.

1. Distribute one Food Web Pictures handout to each group, along with chart paper, a glue stick, and scissors. Have students cut out the pictures. Refer to the previous Engage and Explore activities to review what a food web is, and explain that each group is going to use these pictures to create a possible food web for a rain forest ecosystem.

2. Remind students that the Sun is the beginning source of energy for all other organisms in the food web.

3. Guide students to select the plant pictures as those that would come after the Sun in the food web, and remind them of the definition of producers. Have students in each group begin to glue all of the plants on their chart paper, organized in one line (see the Teacher Guide Key for an example of where each organism might be placed throughout this activity).

4. Have students go through the animal pictures one by one in their groups, deciding where each animal might be placed in the food web based on how they would likely get energy. You may wish to have students identify herbivores/omnivores first and start by placing them near the plants in the food web and then placing carnivores and decomposers together. Review the definitions of consumers (primary and secondary) and decomposers. Tell students to glue pictures of animals onto the chart paper as they go, deciding on the best placement for each one.

5. Have students draw arrows to connect all of the organisms within the food web based on how each one is transferring its energy (see the Teacher Guide Key for examples).

6. Have all groups come together and compare the food webs they have created, holding up a few as examples. Walk the students through a few of the individual food chains within one of the entire food webs. For example, the orchid gives energy to the spider monkey, which gives its energy to the ocelot. The ocelot gives its energy to the velvet worm. At this point, you can pass out the Student Journal page and have students copy down three examples of food chains found within their own food webs in the designated space.

Notes

FACILITATION TIP

Review a few food chains from previous Explores. This gives students a concrete model to build from.

FACILITATION TIP

Check for Diversity in Webs by encouraging groups to include more than one path for energy transfer (e.g., jaguars can eat monkeys or tapirs). This helps move students beyond simple food chains.

Part II

1. Read the following scenario to students:

After each new “change” is introduced (ranch, road, invasive species), stop and have students predict the ripple effects before discussing them as a class.

● The taped-off area of the room represents the Amazon rain forest. Each one of you is one of the animals from our food web that lives in this rain forest and depends on it for food, water, and shelter. The rain forest has been experiencing rapid changes caused by ranchers expanding their grazing lands to raise more cattle. As we go through this activity, think about how these changes will affect you and the food web as a whole.

● Project the Teacher Slide to use as a visual for this scenario. If projection is not available, you may prefer to print a copy for each group.

2. Have all students stand in the large, taped-off square.

3. To represent a ranch, place a strip of tape on one end to make a smaller rectangle within the larger one. Place another strip of tape on the other end to represent another ranch within the taped-off rain forest area. Animals need to move out of the “ranch areas.”

4. Continue the scenario:

● The local government has built a road through this area for the ranchers to use when shipping their cattle to market. This road cuts right through the center of your new home.

5. Place a strip of tape through the center of the rain forest to represent the road. Make sure no one is standing on the road. All students must be on either side of middle piece of tape.

6. Continue the scenario:

● Now that the main road has been built, more ranches are popping up, and smaller roads are built to connect each ranch. More and more traffic is moving through your environment and changing it even more.

7. Discuss how these changes might affect the specific organisms living in this environment. Make sure students understand that the changes make space limited for the animals living in this part of the rain forest, and they are beginning to run out of space as well as resources to use for food and shelter.

8. As a class, discuss some positive and negative effects of this scenario. Examples could include the following:

Notes

Negative Effects

● Trees and plants are dying.

● Some animals will be forced to relocate.

● Some animals may perish because they will not have access to food, water, or shelter.

● Soil erosion increases due to loss of plants.

● Forest flooding increases due to soil erosion.

● Airways and waterways become polluted due to traffic and runoff from pesticides and fertilizers.

● Migration of sensitive wildlife who prefer dark forest interiors decreases.

● Fast-moving vehicles cause animal mortality.

● The human population grows, which causes more forest clearing, pollution, hunting, fires, etc.

Positive Effects

● Increase in economic growth for the area.

● Ranchers make a better living in order to support their families.

● More cattle are raised to feed hungry people.

9. Lead students to realize the specific repercussions related to the individual organisms in the food web the class created. For example, if there are fewer banana trees because they have been cut down to make room for ranches and roads, then there will be less food for howler monkeys. These monkeys will be forced to relocate, or they may die, creating a food shortage for ocelots and jaguars, who in turn will be forced to relocate or possibly die. With fewer of these predators in the ecosystem, populations of other species may increase.

10. Following the discussion, place students into groups of three to four. Distribute one of the Environmental Changes pictures to each group.

11. Have students fill out their Student Journals within their groups. You may want to offer support to the group that receives the card with the introduction of the wild boar. Provide students with background information, explaining that wild boars are native to Europe and Asia and were brought to the rain forest originally to be raised as a source of food for people who moved there. It is thought that a number of boars escaped their habitats over time and have now grown into a sizable wild population. They are harmful to the native animal species living in the rain forest because they bring diseases that the native animals are not able to fight against, and they also eat and destroy certain types of plants.

Notes

Show short visuals (photos of deforestation, roads through forests, or invasive species like wild boars) before the activity so students have background context.

Wild boars are a real-world parallel to invasive species students may know (like zebra mussels in U.S. lakes). Making this connection can strengthen understanding.

12. Discuss some of the environmental changes as a class, making sure to devote special attention to the discussion of the example involving the invasive species of the wild boar so the other groups of students can understand this concept. Lead students to understanding by asking the following questions:

● What created the change in this environment? For example, humans brought boars to raise on their home sites so that they could have a source of meat to eat. Over time, a number of boars escaped their manmade habitats and built up a wild population in the rain forest.

● How is this change helpful? How is this change harmful? Boars living in the wild could provide an additional food source for predators. Instead of certain other animal species that may be endangered, predators may choose to eat boars instead. This could potentially protect endangered species. Boars have been harmful in the rain forest because they have brought diseases that threaten the lives of the native animals who have never been exposed to them before. Also, boars eat and destroy native plants.

● What might happen to the organisms living in this environment? Some species may become endangered if they are threatened by a high rate of disease. If too many plants are eaten or destroyed by boars, it could negatively affect the populations of other animals that rely on those same plants for food.

Students toss a ball to each other and create a class summary of the activity or concept being discussed. Demonstrate how the ball should be thrown to minimize off-task behaviors.

Choose a student to go first. That student should start by giving a one-sentence response to summarize the investigation. Students who wish to go next can raise their hands. The first student should toss the ball to a student with his or her hand raised. Continue until a well-thought-out and thorough summary has been discussed, and then have students return to their seats and write the summary in their science notebooks.

When insects disappear from a forest ecosystem, how does this impact the food web and the survival of other organisms within it?

1. How would the disappearance of insects affect the producers and primary consumers in the food web you created?

2. What changes might occur in the population of secondary consumers and decomposers if insects were no longer part of the ecosystem?

3. How could the absence of insects lead to broader environmental changes, such as soil health and plant pollination, within the forest ecosystem?

STEMscopedia

Reference materials that includes parent connections, career connections, technology, and science news.

Linking Literacy

Strategies to help students comprehend difficult informational text.

Picture Vocabulary

A slide presentation of important vocabulary terms along with a picture and definition.

Content Connections Video

A video-based activity where students watch a video clip that relates to the scope’s content and answer questions.

Career Connections - Zoologist

STEM careers come to life with these leveled career exploration videos and student guides designed to take the learning further.

Math Connections

A practice that uses grade-level appropriate math activities to address the concept.

Reading Science - Let’s Farm Some Shrimp!

A reading passage about the concept, which includes five to eight comprehension questions.

Notes

Multiple Choice Assessment

A standards-based assessment designed to gauge students’ understanding of the science concept using their selections of the best possible answers from a list of choices

Open-Ended Response Assessment

A short-answer and essay assessment to evaluate student mastery of the concept.

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

An assessment in which students write a scientific explanation to show their understanding of the concept in a way that uses evidence.

Guided Practice

A guide that shows the teacher how to administer a smallgroup lesson to students who need intervention on the topic.

Independent Practice

A fill in the blank sheet that helps students master the vocabulary of this scope.

Extensions

A set of ideas and activities that can help further elaborate on the concept.

Use this template to decide how to assess your students for concept mastery. Depending on the format of the assessment, you can identify prompts and intended responses that would measure student mastery of the expectation. See the beginning of this scope to identify standards and grade-level expectations.

Student Learning Objectives

Earth’s environments can be classified into a variety of ecosystems, including freshwater, marine, desert, forest, grassland, and tundra. These unique ecosystems support different varieties of organisms.

Food chains diagram the transfer of energy as it flows from the Sun to producers (plants), to primary consumers (herbivores), to secondary consumers (carnivores that eat herbivores), and on to tertiary consumers (carnivores that eat carnivores).

Food webs diagram the complex relationships of energy flow in an ecosystem containing a variety of producers, consumers, and decomposers.

The removal or addition of an organism in a food chain can affect other organisms.

Environmental changes, such as deforestation, disease, human activities, and invasive species, bring changes in resources that will cause some organisms or populations to perish or move while permitting other organisms or populations to thrive.

The student is expected to demonstrate an understanding of the physical properties of matter, including hardness, reflectivity, conductivity, solubility, and density. Student Expectations

Why do some objects float in water while others sink, and what makes certain materials shiny, hard, or able to conduct electricity?

Key Concepts

• Matter has physical properties that can be observed to determine how matter is classified, changed, and used.

• Physical properties describe the appearance of an object, including mass (amount of matter), color, strength, hardness, flexibility, reflectivity, magnetism (attraction to a magnet), physical state (solid, liquid, or gas), relative density (sink or float), solubility (ability to dissolve in water), response to heat (melt or evaporate), and ability to insulate or conduct thermal or electrical energy.

• The density of an object affects whether the object sinks or floats when placed in a liquid.

This unit develops students’ understanding of physical properties of matter through observation, measurement, classification, and design. Learners examine matter from the macroscopic to the atomic, model atoms combining into molecules, and investigate hardness, reflectivity, conductivity, solubility, and density using empirical tests. Students compare states of matter, collect and analyze data, and use evidence to identify materials. They apply concepts of relative density and buoyancy to engineer, test, and iterate floating solutions, strengthening scientific reasoning and meeting the expectation.

The terms below and their definitions can be found in Picture Vocabulary and are embedded in context throughout the scope.

Conductivity

A physical property that describes the ability to transfer heat or electrical energy

Hardness

A measure of how easily the smooth surface of a mineral can be scratched

Physical Change

A change to a substance without forming a new substance, such as changing size or state of matter

Physical Properties

Characteristics that can be observed or measured; for example, color, melting point, and conductivity

Reflection

The bouncing of energy waves off the surface of an object

Relative Density

How dense something is compared with a reference material

Solubility

Measurement of the ability of a solid to dissolve in a liquid

Notes

Students explore and discuss physical properties of matter through a structured guessing game and classification task.

• Play a 21-questions–style game with Matter Cards, asking only yes/no questions about physical properties (e.g., size, hardness, conductivity, magnetism, solubility) to identify the card.

• Rotate turns selecting cards; if the card isn’t identified within 21 questions, reveal it and start a new round.

• After gameplay, choose five cards and group them by a shared physical property.

• Conduct a peer review by examining other groups’ sets and inferring the property used for classification.

Activity - Atomic Theory

Students investigate how matter is composed of atoms and molecules through observation, modeling, and reflection.

• Observe sand, iron filings, and aloe vera with the naked eye and under a microscope; record and compare drawings.

• Examine a series of leaf images at increasing magnifications to connect visible structures to atoms as fundamental building blocks.

• Reflect in journals on how magnification reveals finer details and supports the concept that all matter is made of atoms.

• Use colored snap cubes to model molecules from atoms (same and different elements) and answer questions to solidify understanding.

Scientific Investigation - Classifying Matter

Students investigate physical properties of matter through hands-on measurement and testing across states and materials.

• Measure temperature and volume of water as a solid, liquid, and gas; observe how shape depends on state and container.

• Test objects for electrical and thermal conductivity, magnetism, and reflectivity using simple circuits, a heat source, a magnet, and a light source; record observations.

• Explore solubility by mixing different powders with water and use evidence to identify each substance.

Engineering Solution - Float Your Boat

Students investigate density and apply engineering design to understand why objects sink or float and how to create a floating vessel.

• Predict and test whether various objects sink or float, using observations to relate outcomes to relative density; record and discuss results.

• Use insights from Part I to design, build, and test clay boats that can carry pennies while meeting criteria for buoyancy, stability, distance traveled, and simulated waves.

• Iterate on designs based on test data, then present results and reflect on performance against the criteria.

Estimated 15 min - 30 min

Students discuss and discover matter through a game of 21 questions.

Materials

Printed ● 1 set of Matter Cards (per group)

● Print and cut out a set of Matter Cards for each group. You may choose to laminate the cards to make them more durable.

SEP Connection

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information Planning and Carrying Out Investigations Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information by engaging in a game of 21 questions to explore the physical properties of matter, such as size, shape, hardness, color, reflectivity, and conductivity. They will plan and carry out investigations by collaboratively asking questions to identify the matter on the card, using fair tests and controlled variables. Students will construct explanations and design solutions by using evidence from their observations to classify and group materials based on shared physical properties, thereby explaining the phenomenon of why some objects float or sink and what makes certain materials shiny, hard, or conductive.

Notes

Structure and Function Scale, Proportion, and Quantity

During this activity, students will explore the phenomenon of why some objects float in water while others sink, and what makes certain materials shiny, hard, or able to conduct electricity by engaging in a game of 21 questions. This will help them understand the concept of Structure and Function by recognizing that different materials have different substructures, which can sometimes be observed, and these substructures have shapes and parts that serve functions. Additionally, they will apply the concept of Scale, Proportion, and Quantity by using standard units to measure and describe physical quantities such as size, shape, hardness, and conductivity.

1. Tell students the rules of the game:

○ Select a Matter Card, and do not share the card with the others in your group.

○ Group members may ask up to 21 "yes" or "no" questions to try to figure out what is on the card. (Each guess of the card takes away from the 21 questions.)

○ The questions can be about only the physical properties (size, shape, hardness, color, reflectivity, electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, response to magnetic forces, solubility, etc.) of the type of matter.

○ If the object is guessed, another student may choose a different card and start over. If the card is not guessed after 21 questions, share what was on the card, and another student may choose a different card to continue the game.

2. After the game is over, have students select five cards that can be grouped together based on a physical property they all share.

3. When the other groups are ready, have students take turns looking at each other’s groupings and guessing what property was used to classify the materials.

How do the physical properties of matter, such as size, shape, and conductivity, determine whether an object will float or sink in water, and what makes certain materials shiny or hard?

1. How do the physical properties of an object, like density and buoyancy, affect whether it will float or sink in water?

2. What role do properties like reflectivity and hardness play in determining the appearance and durability of materials?

3. How can understanding the electrical conductivity of materials help us predict their behavior in different environments or applications?

Notes

FACILITATION TIP

Review physical properties with students.

Size & Shape: measurable dimensions.

Hardness: resistance to scratching/ breaking.

Reflectivity: how much light bounces off.

Conductivity: ability to carry heat/ electricity.

Magnetism: attraction to magnets.

Solubility: ability to dissolve in water.

Estimated 30 min - 45 min

In this activity, students explore the properties of atoms and molecules by looking at items with their eyes and using a microscope to compare what they see.

Materials

Printed

● 1 Student Guide (per group)

● 1 Student Journal (per student)

● 1 Leaf Images (per class)

Reusable

● 1 microscope (per group)

● 2 red snap cubes (per group)

● 2 blue snap cubes (per group)

● 1 green snap cube (per group)

Consumable

● 1 spoonful of sand (per group)

● Iron filings (per group)

● 1 piece of aloe vera plant (per group)

● Place the sand, iron filings, and aloe vera plant piece at each group.

● If you do not have enough microscopes for each group, you can project what is seen under the microscope for the whole class.

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

Planning and Carrying Out Investigations

Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions

During this activity, students will obtain, evaluate, and communicate information by observing objects with their eyes and under a microscope to understand the properties of atoms and molecules. This will help them explain the phenomenon of why some objects float in water while others sink, and what makes certain materials shiny, hard, or able to conduct electricity. They will plan and carry out investigations by using fair tests to produce data that serves as evidence for their explanations. By constructing explanations and designing solutions, students will use evidence from their observations to describe and predict phenomena, such as the behavior of materials in water and their physical properties.

Structure and Function

Scale, Proportion, and Quantity