GRADE 6

Student Workbook

Grade 6

Published by Accelerate Learning Inc., 5177 Richmond Ave, Suite 800, Houston, TX 77056. Copyright © 2025, by Accelerate Learning Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written consent of Accelerate Learning Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning.

To learn more, visit us at www.stemscopes.com.

This Student Notebook is designed to be used as a companion piece to our online curriculum.

The pages of this book are organized and follow the 5E model.

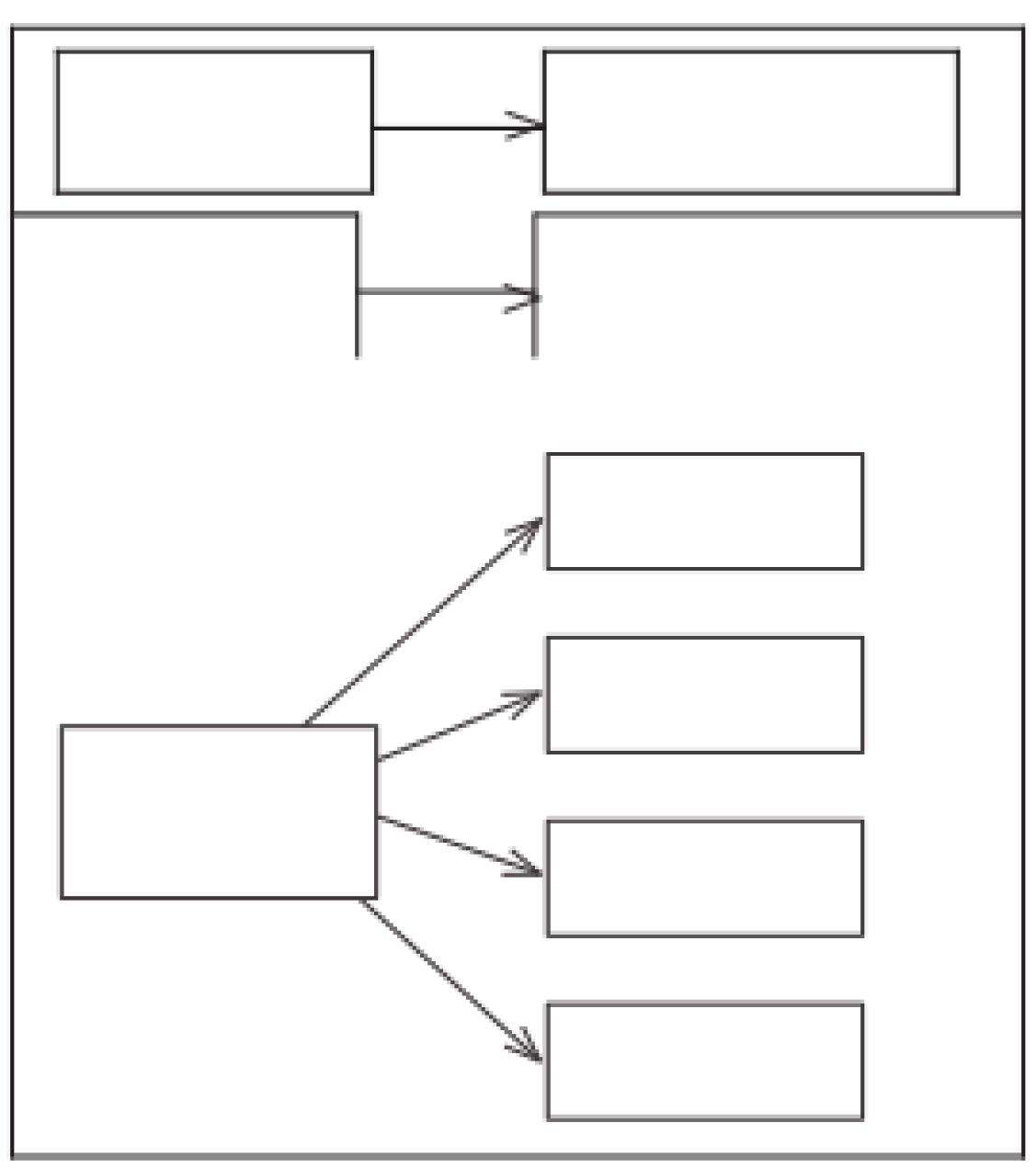

ENGAGE

A short activity to grab students’ interest

EXPLORE Student Journal

Hands-on tasks, including scientific investigations, engineering solutions, and problem-based learning (PBL)

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning (CER)

A formative assessment in which students write a scientific explanation to show their understanding

STEMscopedia

EXPLAIN

ELABORATE

A reference material that includes parent connections, technology, and science news

Reading Science

A reading passage about the concept that includes comprehension questions

EVALUATE

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning (CER)

A summative assessment in which students write a scientific explanation to show their understanding

Open-Ended Response (OER)

A short answer and essay assessment to evaluate mastery of the concept

Only student pages are included in this book and directions on how to use these pages are found in our online curriculum. Use the URL address and password provided to you by your district to access our full curriculum.

L.6.1.3 and 1.4

L.6.1.1, 1.2, 1.5, and 1.6 Parts of

L.6.3.1, 3.2, and 3.3

L.6.3.4 and 3.5

L.6.4.1 and 4.2

L.6.4.3, 4.4, and 4.5

P.6.6.1, 6.5, and 6.7

Newton’s

P.6.6.2, 6.3, 6.4, and 6.6

Forces

E.6.8.1, 8.2, and 8.3

E.6.8.4, 8.5, 8.6, and 8.7

L.6.1.1, 1.2, 1.5, and 1.6

Cell Theory

Units of Life

Activity

1. Obtain a set of picture cards from your teacher.

2. Arrange the cards into four rows: Organisms Structures Cells Organelles

3. Copy your final organization into your lab journal using words or drawings.

4. How did you decide where to place the picture of bacteria? Write the answer in your lab journal.

Name:

Explore 1

Part I: Cells Equal Living

Scientific Investigation

Multicellular vs. Unicellular

All living or once-living things contain cells. Living things, whether unicellular or multicellular, also display life functions. Some important life functions include the following:

• Obtaining food and water

• Disposing of waste

• The ability to grow and reproduce

L.6.1.1, 1.2, 1.5, and 1.6 Cell Theory

In addition to life functions, living things must have environments in which they can live. Never-living things do not contain cells and show none of the life functions.

Procedure

Plan an investigation to determine if living things are made of cells.

Step 1: Question

Step 2: Relevance

Step 3: Variables, if applicable

Independent variable (also known as the manipulated variable):

Dependent variable (also known as the responding variable):

Control variable(s) or group (also known as constants):

Explore 1

Step 4: Hypothesis

Is a hypothesis needed? If so, what is it?

How will the responding variable change when the manipulated variable changes?

Step 5: Materials

Step 6: Safety Considerations

Step 7: Procedure

1. Make a wet mount of different items your teacher gives you.

2. Observe each item under the microscope. Determine if the specimen has cells, if it is living or nonliving, and what life function the observed cells may perform.

3. Draw all observations.

4. Label all drawings.

Explore 1

Step 8: Data Collection

Use the chart to record your data.

Step 9: Data Analysis

Create a graph based upon the data, if needed. Make a general statement about the results shown. Specimen

Explore 1

Step 10: Conclusion and Scientific Explanation Write a scientific explanation on what all living things have in common.

Claim:

Evidence:

Reasoning:

Explore 1

Part II: Single or Multi?

Activity

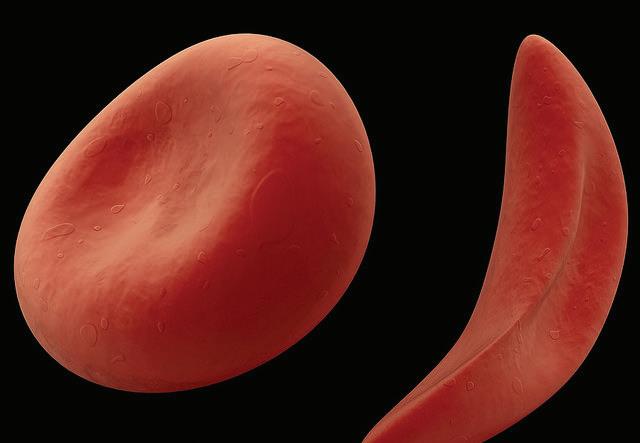

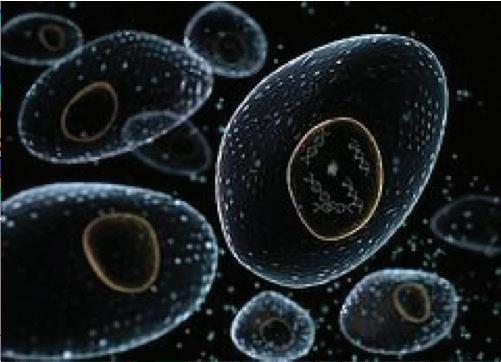

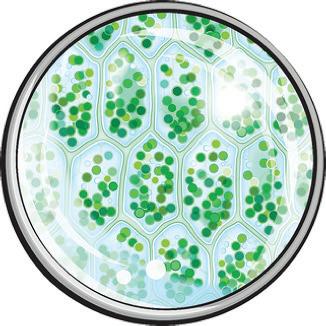

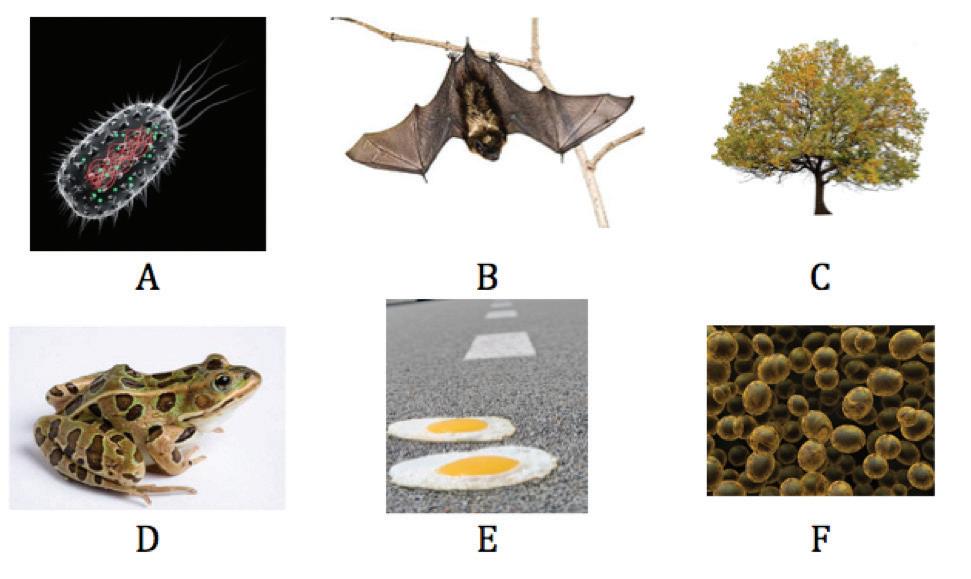

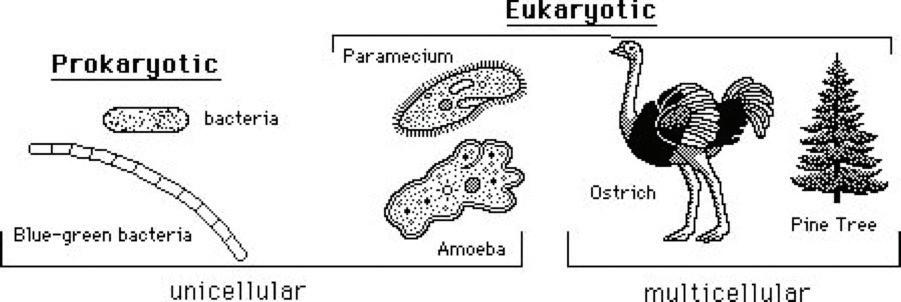

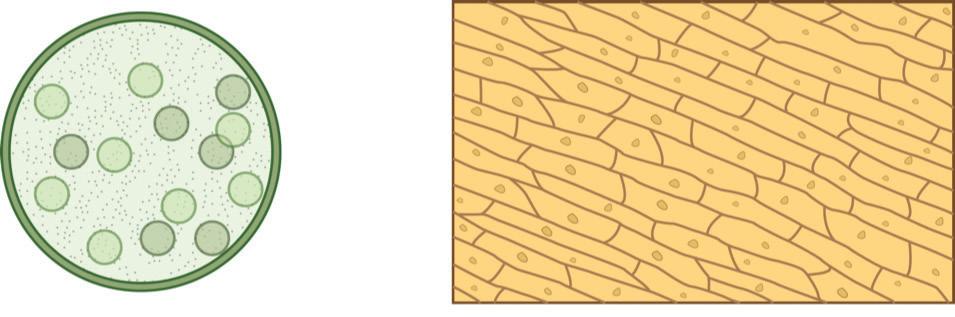

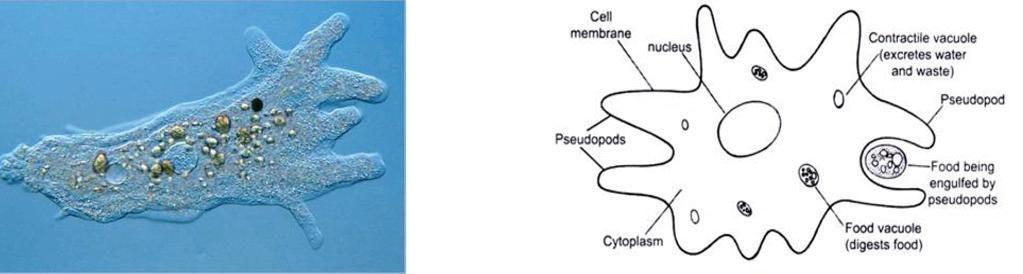

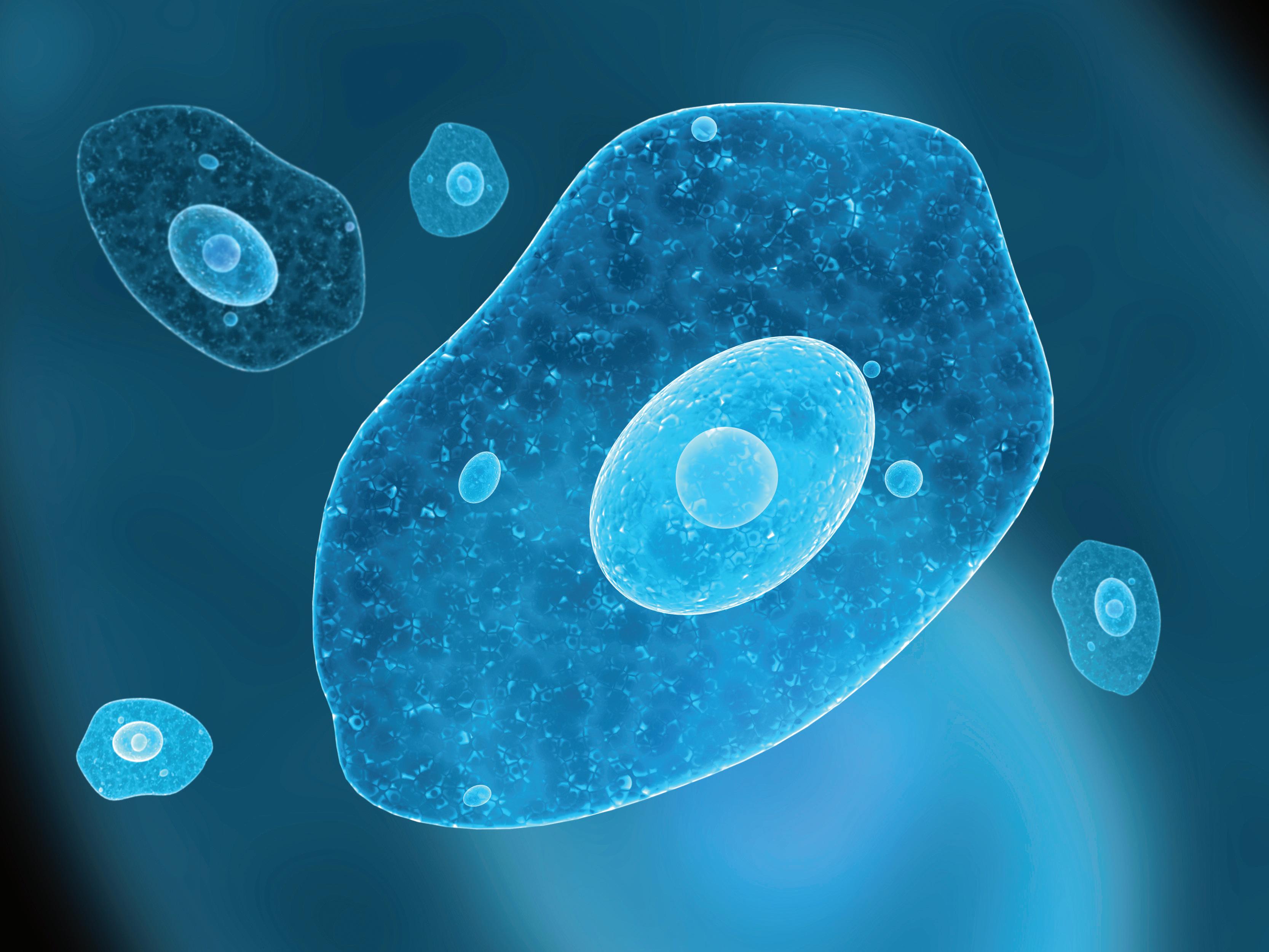

A cell is a fundamental unit of structure, function, and organization in all living organisms. Every living organism is made up of one or more cells. Some organisms are unicellular, meaning they consist of only a single cell. Other organisms, such as plants and humans, are multicellular, consisting of many cells. Humans have about 100 trillion cells!

Procedure

As you observe the images below, discuss the following questions with your group. Be prepared to defend your conclusions.

1. Which of the following organisms would you consider to be unicellular?

2. Which of the following organisms would you consider to be multicellular?

3. Write your ideas on the back of this sheet. 4. Share your ideas with your classmates.

Explore 2

Cell Theory

Activity

Cell theory is an explanation of the relationship between cells and living organisms. It states that all living organisms are composed of cells, cells are the basic unit of structure and function in living things, and that cells arise from preexisting cells. This theory holds true for all living things, unicellular or multicellular.

Procedure

Part I

1. Write down three things that are needed for life.

2. After two minutes, your teacher will call time, and you will need to share with the members of your group.

3. Write down all ideas.

4. When your teacher calls time, one member of your group will move to another group and share the list that your group came up with.

5. The new group will share what their group wrote, and the member of your group will write down any new information.

6. The traveling member of your group will continue to the next group until the teacher calls time.

7. The traveling member of your group will share any new information with your group.

8. Your teacher will place a list of the basic characteristics of life on the board or project it on the wall.

9. Check off all the characteristics your group came up with and add any that were missed.

Explore 2

Part II

1. Your group will be assigned a scientist to research.

2. Your group should find the answer to the question, “What did this scientist contribute to the idea of the cell theory?”

3. Your research must include three different sources.

4. After you have conducted the research, draw a poster about the scientist and his contribution.

5. The only words on the poster should be the scientist’s name and the year or range of years during which he contributed. Everything else should be a drawing representing the scientist’s contribution.

6. Your group will present your poster to the class. Your presentation must include a new question about cell theory based on your findings.

Explore 3

Activity

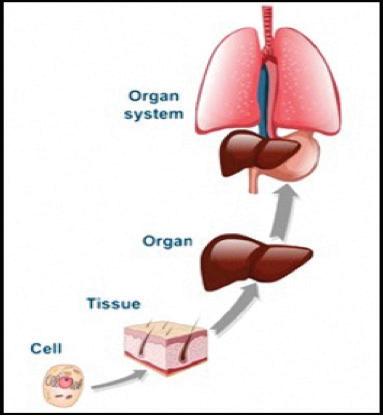

Levels of Organization

Multicellular organisms, such as plants and animals, have various levels of organization within them. The levels of organization from simplest to most complex are cells → tissues → organs → organ systems → organisms.

Cells are the first and simplest level, as they are the basic structural and functional units in living things. Tissues, the next level, are made up of cells that are similar in structure and function which work together to perform a specific activity. Organs are made up of tissues that work together to perform a specific activity. The fourth level is made up of the organ systems. These are groups of two or more organs that work together to perform a specific function for the organism.

Procedure

Part I

1. Your body is organized like an apartment building. The cells are like the bricks. A number of cells put together form tissues. A number of tissues put together form organs. The organs make up an organ system, and all the organ systems make up the organism.

2. To help yourself remember the order of a list of things, you can make up a silly sentence using words that start with the first letter of each word on the list. For the levels of organization you need a silly sentence such as Can Tigers Own Orange Spotted Orangutans? (C for cells, T for tissues, O for organs, OS for organ systems, and O for organism.)

3. Make up your own silly sentence to help you remember the correct order of the levels of organization.

Explore 3

Part II

1. Your teacher will give you a sheet of paper with pictures. Cut the pictures out and place them on your desk.

2. Find the pictures of the brick, rooms, and building. Place and then glue them in order from simplest to most complex.

3. Next, look at the rest of the pictures. Find the single cells and match up the tissue, organ, organ system, and organism that go together.

4. Place and then glue them in order from simplest to most complex.

5. Label them from cells to organism.

Part III

Now it is your turn to create your own levels of organization analogy. Using the apartment building analogy as an example, create a new levels of organization analogy. Some examples are a city, school, sports team, and the world.

My analogy is

• A cell is like:

• A tissue is like:

• An organ is like:

• An organ system is like:

• The whole body is like:

Organelle Tissue Organ System

Organism’s Need That Is Met

Explore 3

Part IV

1. Your teacher will give your group a new set of cards.

2. Use the information provided on the cards to complete the following chart.

Part V

1. Read the Student Reference Sheet: Body Systems to find evidence that these systems are made of cells.

2. Write a scientific explanation to support the statement, “The human body is a system of interacting subsystems composed of groups of cells.” Use evidence from Parts II, III, and IV of this activity to support your claim.

3. After completing your scientific explanation, exchange your paper with a classmate and evaluate the evidence and reasoning.

Name: ____________________________ Date: ___________

STEMscopedia

Which duck is alive?

You probably think Duck 1 is a nonliving thing and Duck 2 is a living thing. How can you tell? What evidence do you find to prove your conclusion? Perhaps you observe that Duck 1 is a plastic duck and Duck 2 is a live duck.

Living versus Nonliving

What signs of life do you find for evidence that Duck 1 is nonliving? Does it have fake features, no legs, and no feathers? A factory probably made the duck.

Scientists would say that Duck 1 is not living because it does not have needs that must be met. It will not grow or develop, and it cannot reproduce new life. Duck 1 might move as it bobbles in the water, but it is not moving on its own, nor can it respond to change.

On the other hand, Duck 2 is swimming in water with webbed feet and has feathers. This duck came from an egg that a parent duck laid, it hatched, and it began its life as a duckling. This duck has needs, grows, will eventually reproduce new ducklings, moves on its own, and responds to the environment.

Reflect Look Out!

All

living organisms are made of cells.

There is one more important piece of evidence that the duck is alive—it is made of cells! All living organisms are made of cells. Life is the quality that distinguishes living things (composed of living cells) from nonliving objects. The cell is the smallest unit of life.

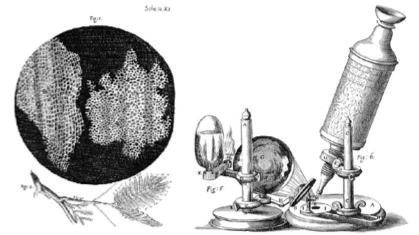

Hooke’s microscope and drawing of a cork cell

Discovery of Cells

Prior to the 1600s, scientists did not know about cells because the microscope had not yet been invented. In 1674, Anton van Leeuwenhoek used a single-lens microscope to see the first unicellular organisms, which he called “animalcules.” Later that century, experimental scientist Robert Hooke used the term cell for the boxlike structures he observed when viewing the tissue of a cork through a lens.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

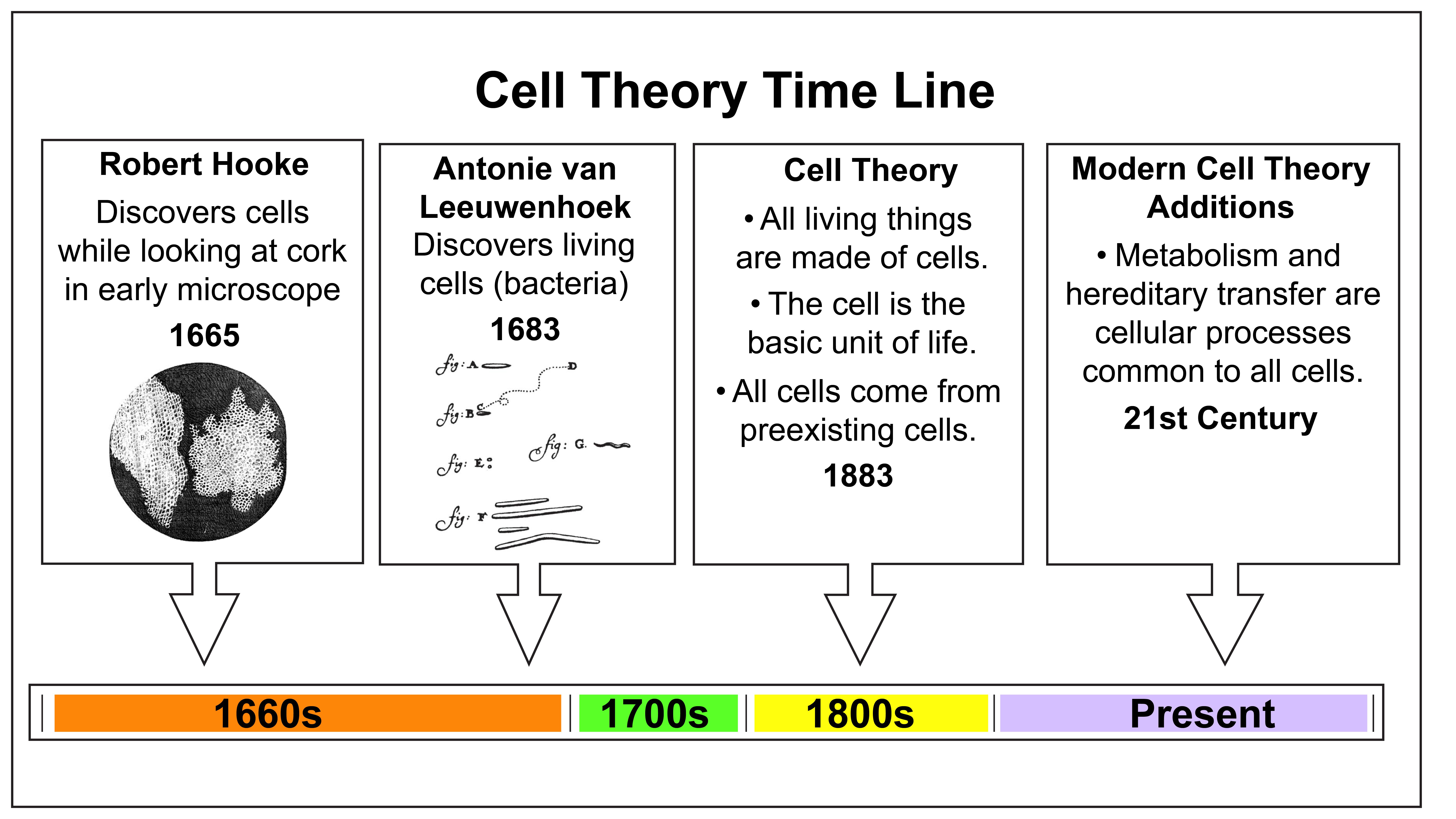

The cell theory summarizes the characteristics common to all cells and the fundamental role cells play as the basic building blocks of life. In the 1830s, almost two hundred years after van Leeuwenhoek saw his first “animalcules,” more discoveries about cells led to the development of the cell theory by two German scientists, botanist Matthias Schleiden and zoologist Theodor Schwann. They proposed a unified cell theory with two parts that were proven true with supporting evidence:

• All living things are composed of one or more cells. Evidence is based on observations by biologists using early microscopes to see structures of organisms: Robert Hooke’s observations of a piece of cork with small compartments he called “cells” (1663), Anton van Leeuwenhoek’s observations of bacteria and Protozoa through his microscope (1673), and observations by Schleiden and Schwann of plant and animal cells (1838–39).

• The cell is the basic unit of life. Evidence is based on experiments that have shown that the structures within the cell cannot exist independently. The entire cell is needed to support cell function.

In 1855, German biologist Rudolf Virchow added his important contribution to this theory:

• All cells come from preexisting cells. Evidence from early experiments by Francesco Redi showed that new maggots (fly larvae) did not appear spontaneously. Fly larvae did not appear on meat in a screened container but did on an unscreened jar where flies could lay their eggs. Louis Pasteur repeated similar experiments in curved neck containers to better control air access to the sample. He also found the air contained tiny particles that contaminated the meat. His work led to the pasteurization of milk to protect it from bacteria. Scientists have imaged actual cell division (mitosis and meiosis).

STEMscopedia

For the first 150 years, the cell theory was primarily about a cell’s structural components and cell reproduction. Since the 1950s, however, cell biology has focused on DNA and its informational features. Today we look at the cell as a unit of self-control, which is the description of how a cell’s genetic information is converted to structure. Three principles were added to the original cell theory:

• Cells contain hereditary information that is passed from cell to cell during cell division.

• All cells are basically the same in chemical composition.

• All energy flow (metabolism and biochemistry) of life occurs within cells.

What Do You Think?

Have you ever wondered how people are similar to bacteria? It may seem like a silly question. After all, humans and bacteria are very different in size and complexity. Yet scientists have learned that we also have much in common with our microscopic companions.

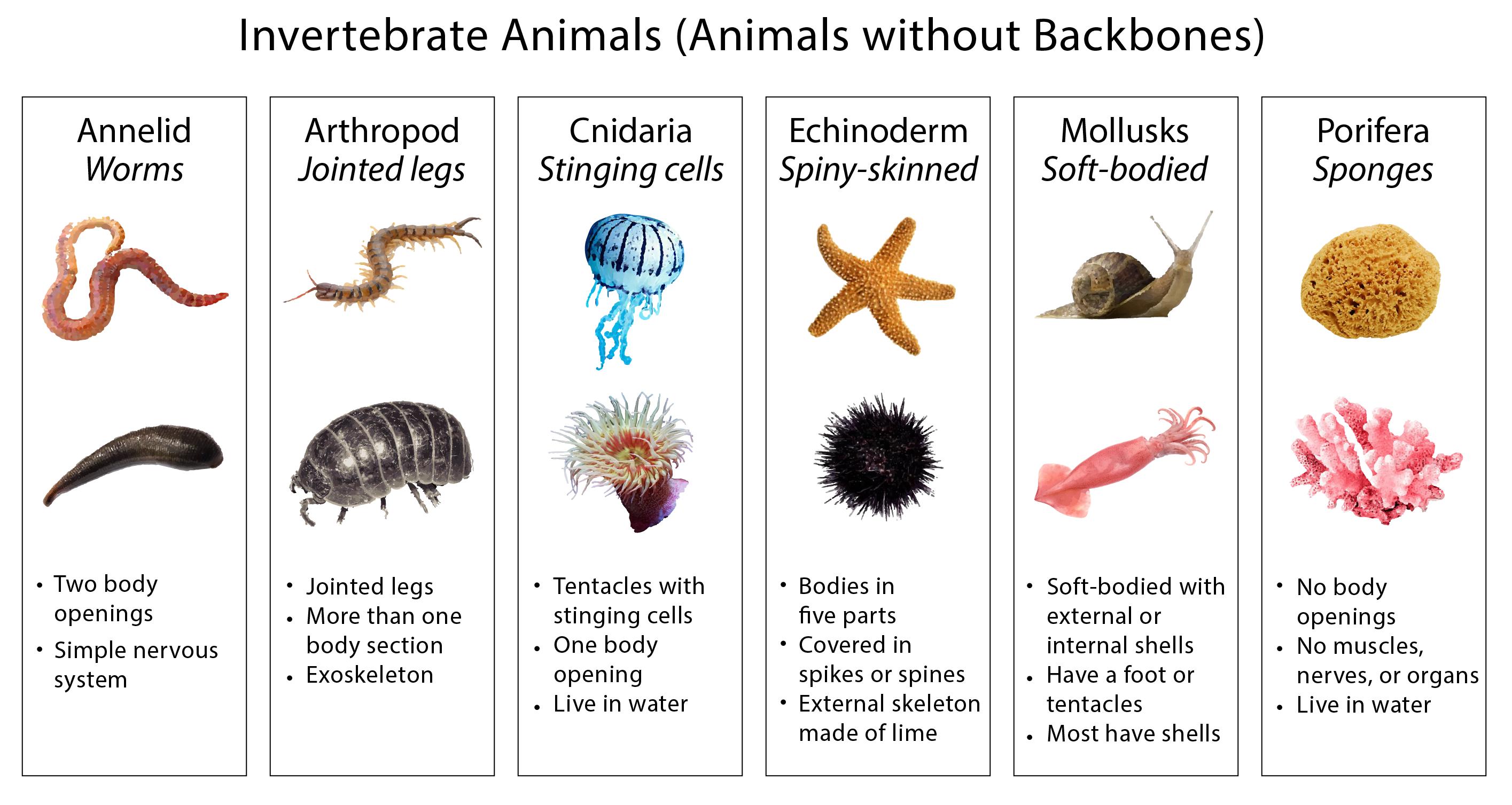

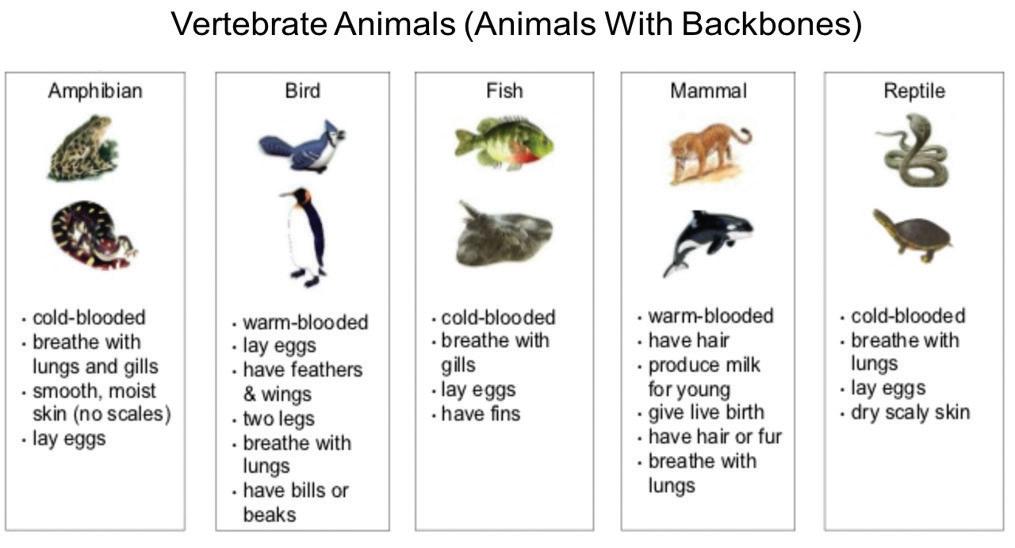

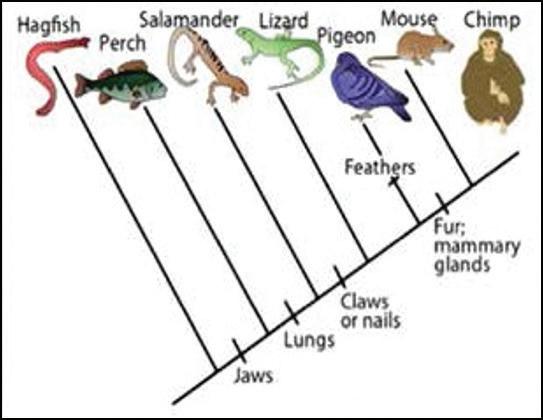

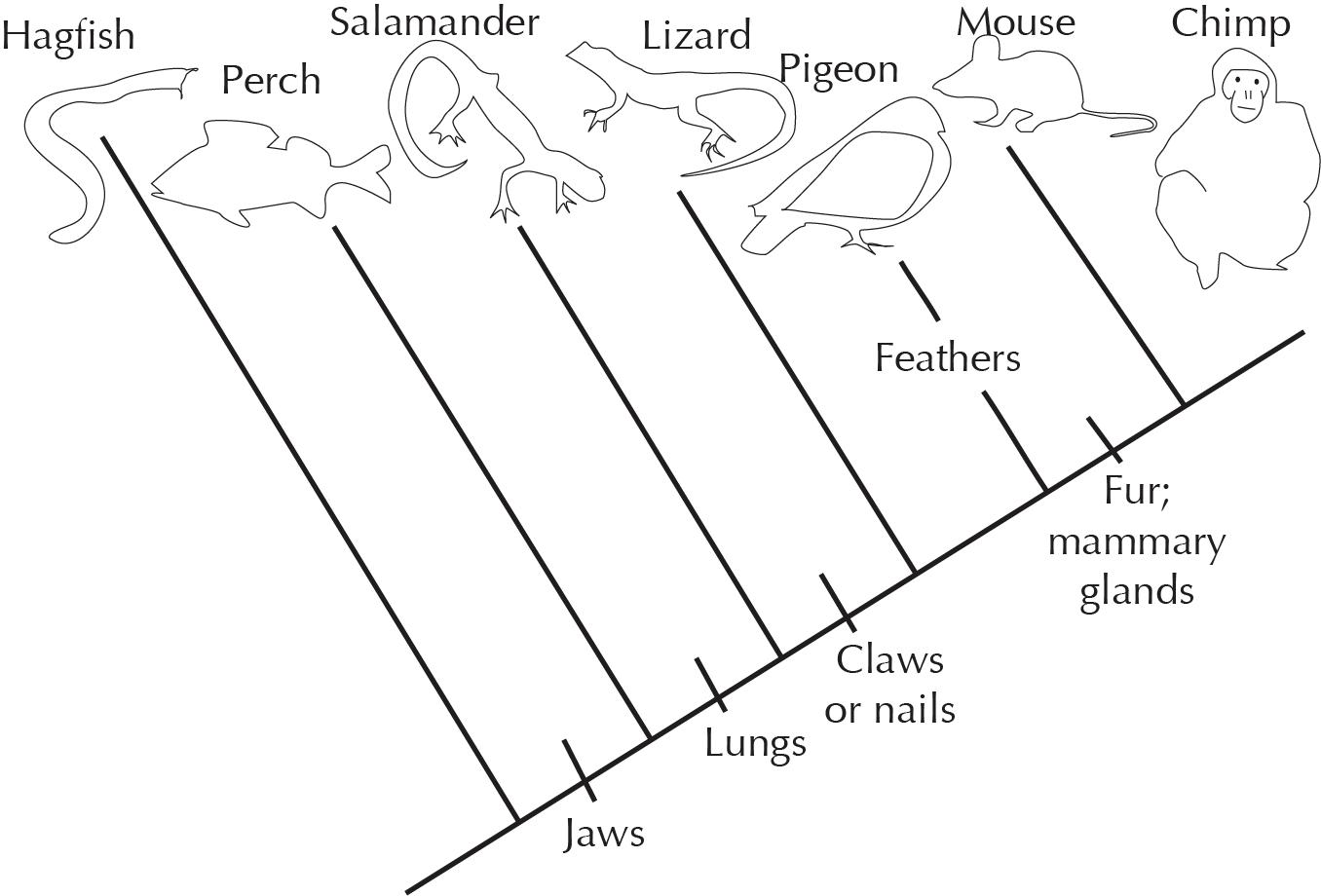

Scientists classify all organisms into groups based on their external characteristics. For example, some plants produce fruits with seeds, but other plants do not. Scientists also use internal characteristics to classify organisms. For example, some animals have backbones, while others do not. Can you think of some other external or internal characteristics that scientists can use to classify organisms?

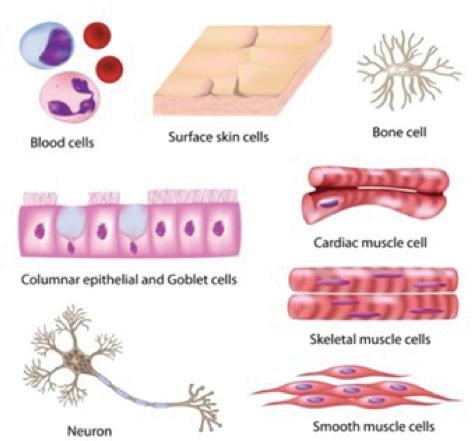

All of these different types of cells are found in the human body. Can you identify where you find these cells in the body?

The cell is the basic unit of life.

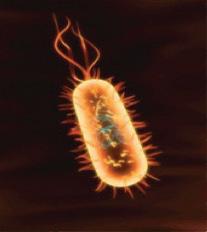

How is this bacterium similar to a human?

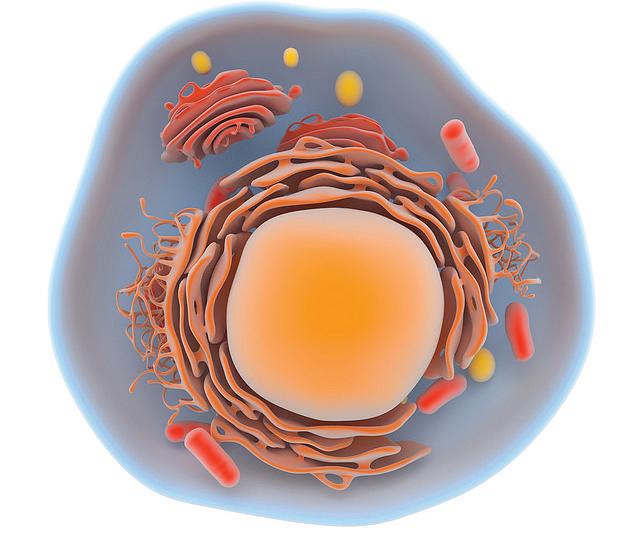

One of the most important internal characteristics that scientists use to classify organisms is the cell. All organisms are made up of one or more cells. A cell is the basic unit of life; it is surrounded by a cell membrane that keeps the cell intact. Inside all eukaryotic cells are specialized structures called organelles that carry out specific functions inside the cell. Organelles are suspended in a thick, gel-like fluid called cytoplasm

All cells also have genetic material called DNA, which contains instructions for making new organisms and for carrying out all functions that keep a cell alive. In some cells, DNA is packaged inside a membrane in an organelle called a nucleus. In other cells, it floats freely in the cytoplasm.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

All living organisms are composed of one or more cells. When you think about an organism, you might think of something very familiar, such as people, cats, or trees. These organisms are complex; they are made up of a great number of different kinds of cells. Scientists estimate that the average adult human has somewhere between 10 and 100 trillion cells in his or her body!

Cells come in many different sizes and types, and they are very different from each other in their shapes and functions. The diagram on the previous page shows examples of different types of cells in the human body.

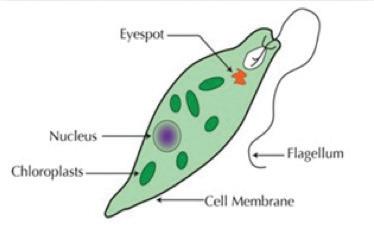

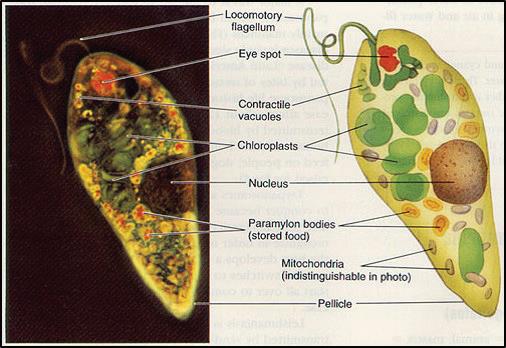

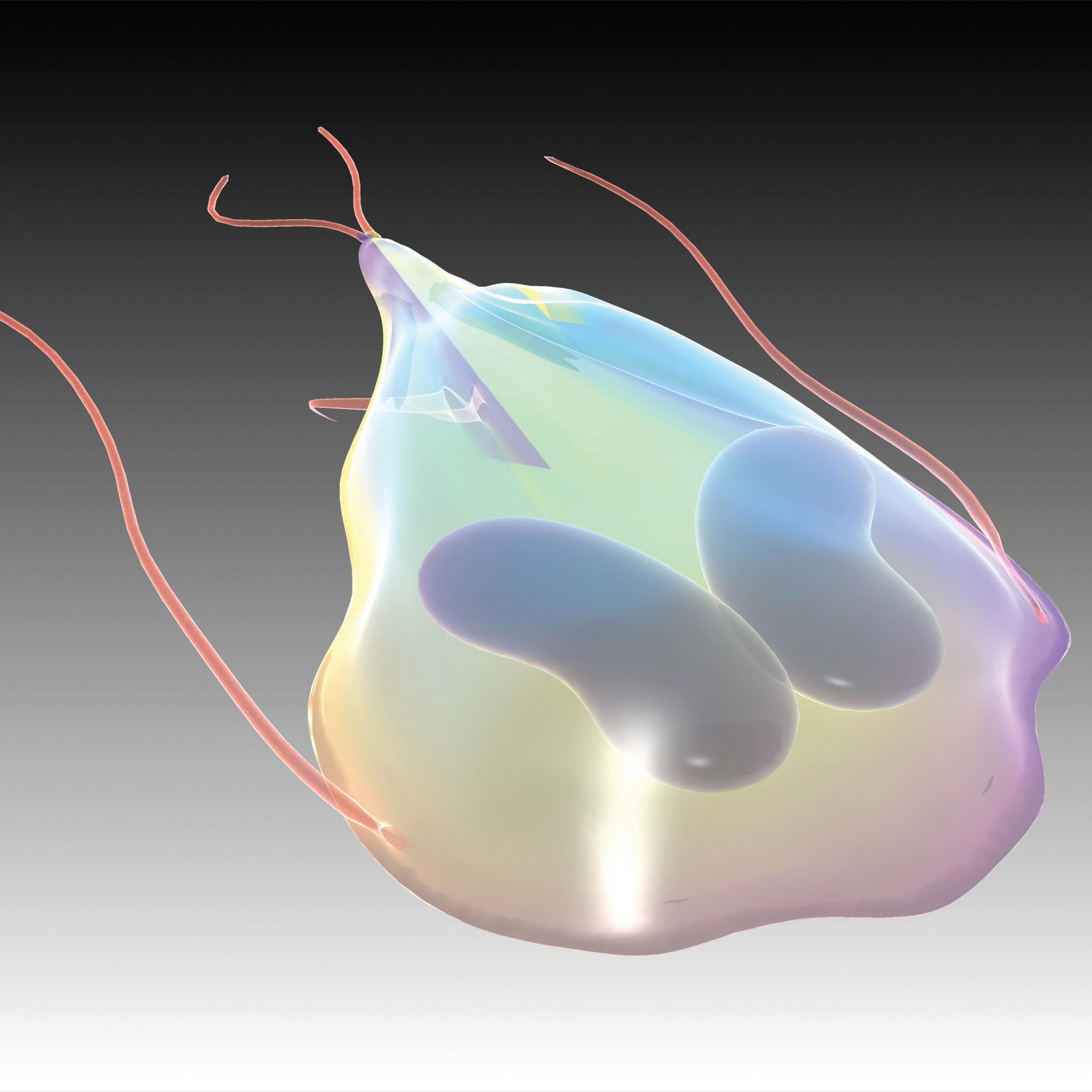

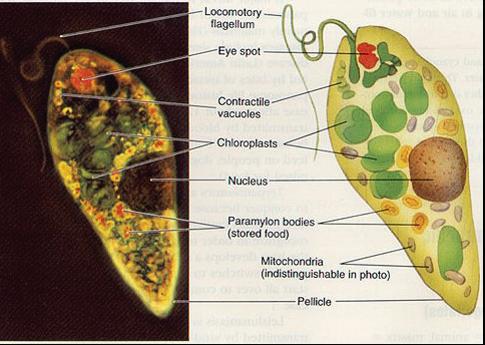

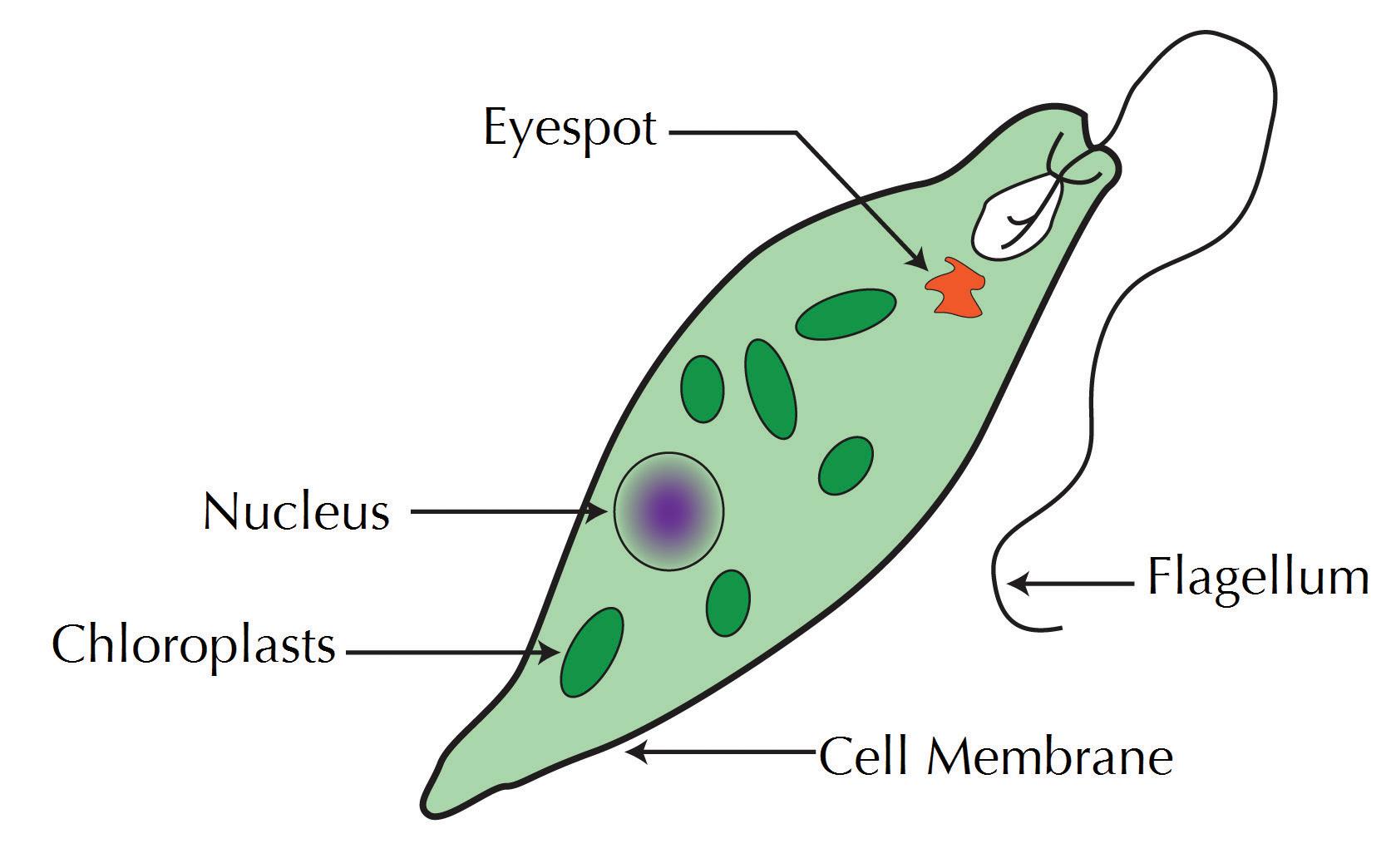

Euglena are single-cell organisms that live in fresh and salt water.

Not all organisms are complex. Some are very simple. In fact, some organisms are made up of only one cell. Take a look at this Euglena. A Euglena is an organism made up of a single cell. Unlike humans, it does not have specialized organs such as a brain or stomach. However, it can move through its environment using its whip-like flagellum. It even has a primitive eye called an eyespot for sensing light levels. All this in a single cell!

Look Out!

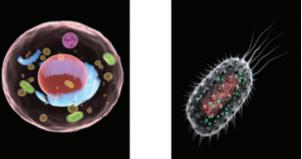

The two main types of cells are prokaryotic and eukaryotic.

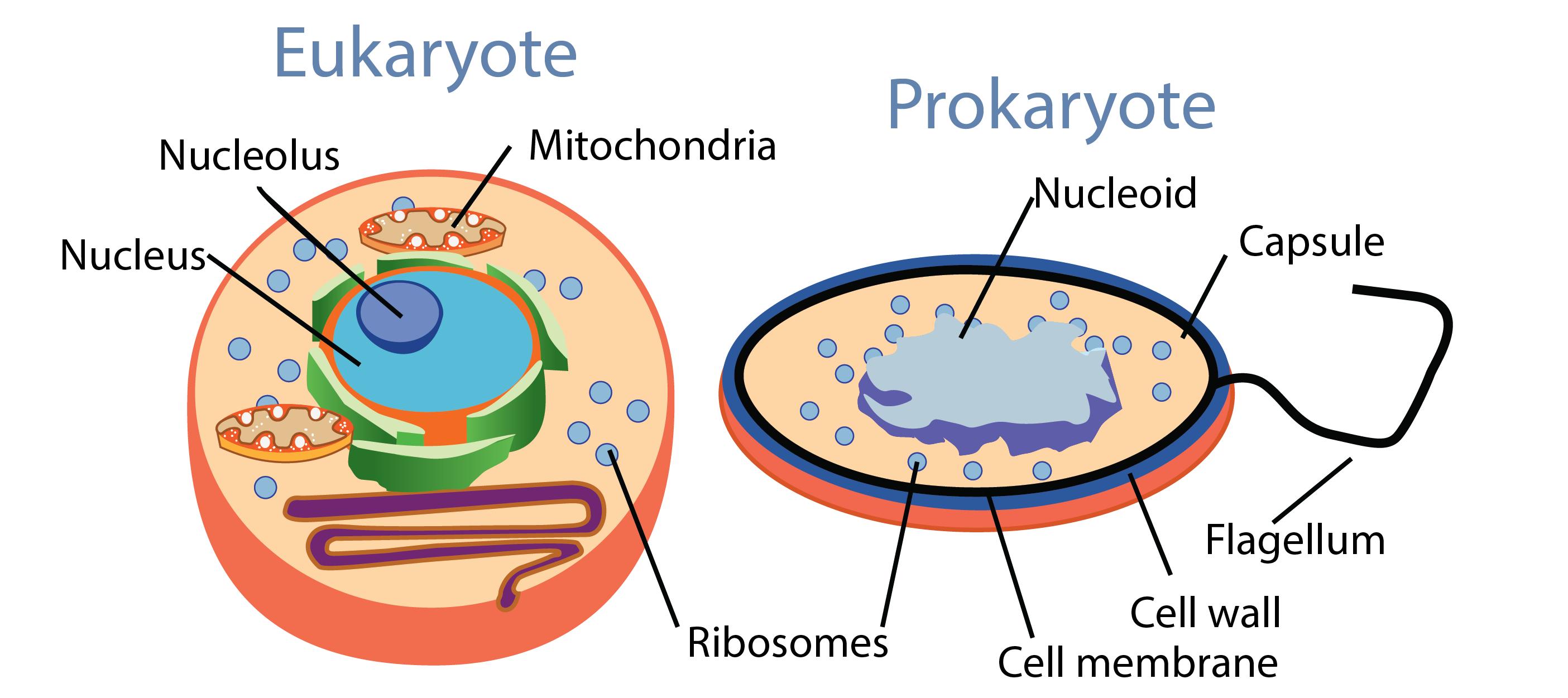

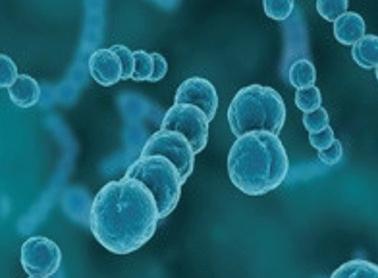

All organisms are made up of cells. However, scientists separate cells into two categories: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. Examples of prokaryotic cells include bacteria. Eukaryotic cells include the cells of plants, animals, and fungi.

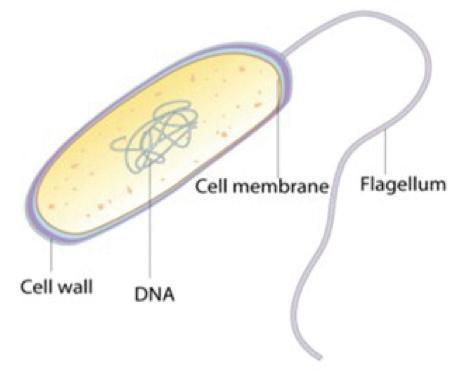

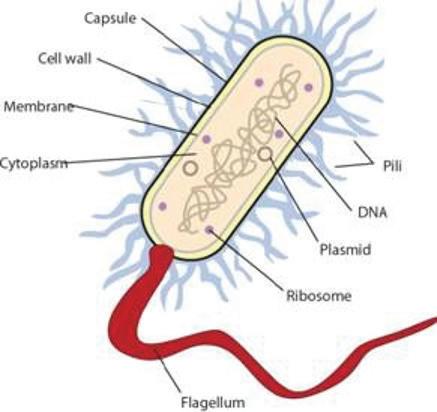

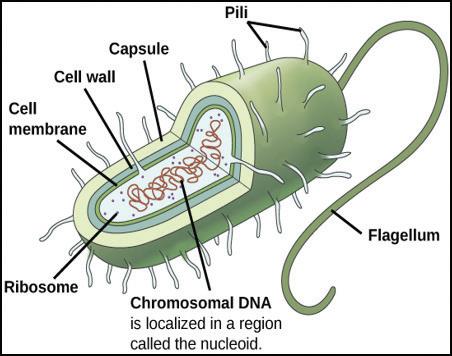

Prokaryotic cells were probably the first cells on Earth dating to around 3.8 to 4 billion years ago. Prokaryotic cells have the basic structures common to all cells: a plasma membrane surrounding cytoplasm. However, they do not have membrane-enclosed organelles, such as mitochondria or a nucleus.

Prokaryotic cells do contain ribosomes, but there is debate as to whether or not a ribosome counts as a type of organelle. Therefore, the question of whether or not prokaryotic cells contain any organelles is still up for debate.

Prokaryotes have no nucleus and have a single circular DNA.

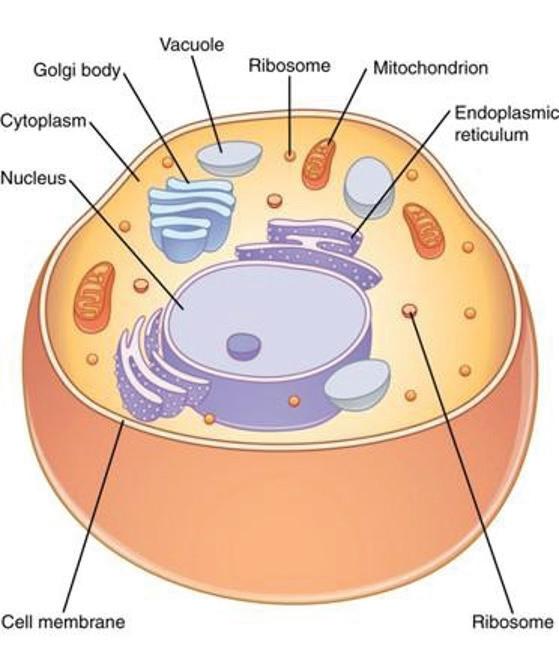

Eukaryotic cells are more complex. Similar to prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells have a cell membrane, cytoplasm, and DNA. However, they have something that prokaryotic cells do not. Eukaryotic cells have organelles surrounded by membranes. This includes mitochondria and a nucleus, where DNA is stored.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

A prokaryotic cell (right) has a cell membrane, cytoplasm, and DNA. A eukaryotic cell (left) also has these features. Eukaryotic cells also have membrane-enclosed organelles such as mitochondria and a nucleus.

Look Out!

Prokaryotic cells were the first cells to evolve on Earth. However, this does not mean they disappeared when the eukaryotic cells evolved 1.5 billion years ago. Bacteria are prokaryotic cells that are very much still alive today. In fact, thousands of species may live in one spoonful of soil.

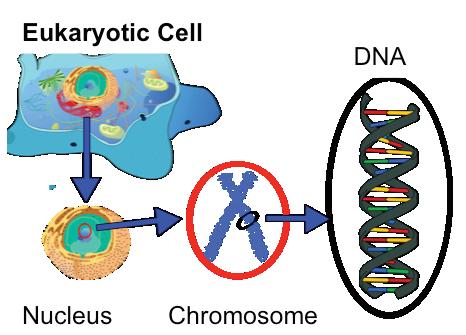

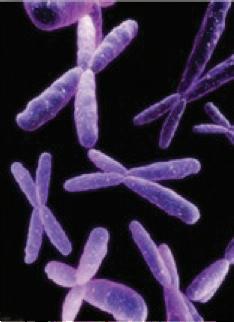

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells store DNA in different ways. Both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells have DNA, the “blueprint” of an organism. In eukaryotic cells, the DNA is neatly organized inside a nuclear membrane. The combination of nuclear membrane and DNA is called the nucleus. Each eukaryotic cell has just one nucleus. The DNA inside the nucleus is organized into units called chromosomes, which are linear and can be seen under a microscope when the cell divides.

Prokaryotic cells are less organized than eukaryotic cells. They lack a nuclear membrane around their DNA. Instead, their DNA floats in the cytoplasm. The DNA of a prokaryotic cell is all contained within a single, circular chromosome.

Eukaryotic cells organize their DNA into chromosomes.

STEMscopedia

What Do You Think?

Does the picture to the left show a prokaryotic or eukaryotic cell? Why do you think this? What is the evidence for your conclusion?

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have other important similarities and differences.

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have other things in common. Both have ribosomes in their cytoplasm. Ribosomes are responsible for making proteins in the cytoplasm. The ribosomes in eukaryotic cells are bigger and more complex than those in prokaryotic cells. However, they have the same function of making proteins.

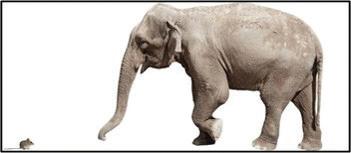

Prokaryotic cells tend to be much smaller than eukaryotic cells. Bacteria are prokaryotes. On average, eukaryotic cells are about 10 times larger than prokaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells have much greater diversity in shape and size than prokaryotic cells.

Organisms with prokaryotic cells are so small they can be seen only through a microscope. You also need a microscope to see eukaryotic cells. However, many organisms with eukaryotic cells are large enough to see without a microscope.

Discover Science: How did organelles become established in eukaryotes?

Scientists have an interesting theory to explain how organelles came to be present in eukaryotic cells. They theorize that prokaryotes were present on Earth long before eukaryotes. Lacking food, some prokaryotes lost their cell walls. Their flexible membranes began to fold and create several internal membranes and a nucleus.

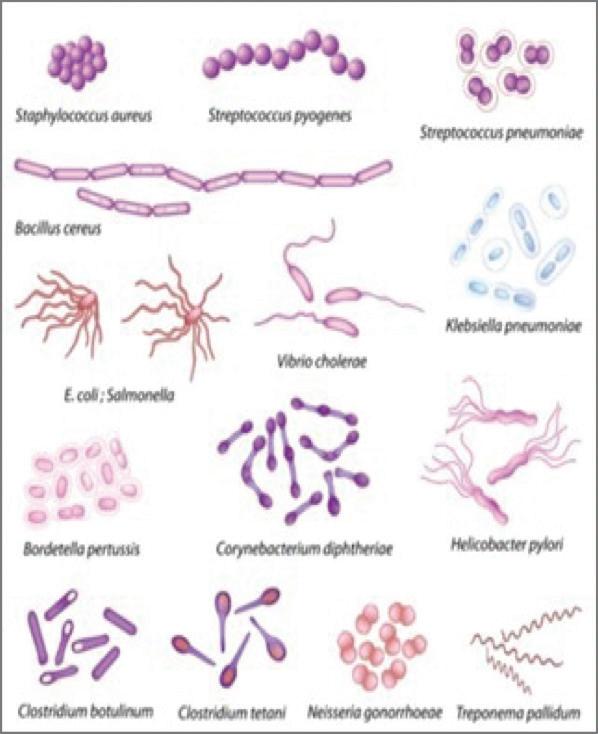

These bacteria commonly infect humans. Can you identify the cells that are spherical (round), rod-shaped, and spiral?

These primitive eukaryotic cells began engulfing or taking in smaller prokaryotes as shown in the diagram below.

STEMscopedia

However, scientists think some of these events did not result in the larger cell digesting the smaller cell. Instead, the smaller cell may have provided some advantage to the larger cell. For example, if the smaller cell could carry out photosynthesis, it could provide energy from this process for the larger cell. In return, the larger cell provided protection for the smaller cell. This mutually beneficial relationship is known as symbiosis. The theory about the origin of organelles is known as endosymbiotic theory. The word endosymbiotic is used because the root word endo- refers to the engulfing process, and symbiotic refers to the relationship that led to organelle development. According to the theory, over many years, the two symbiotic cells became a more complex eukaryotic cell.

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells can be single-celled organisms. However, there are no multicellular prokaryotes. Only eukaryotes can be multicellular.

Eukaryotic cells come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Prokaryotic cells have just three basic shapes: rod, spherical, and spiral. The cell shapes help scientists identify prokaryotes using a microscope.

Career Corner: Knowing the different types of cells can save lives.

When a person is infected with a bacterium, it is important to know the identity of the infectious agent. Antibiotic drugs can be specific for particular organisms. If a doctor does not know which organism is causing an illness, the doctor may not be able to treat the patient.

For example, a patient with symptoms of strep throat may be given a throat swab. The swab is then cultured to grow any microorganisms present in the patient. When there are enough microorganisms growing in the culture, the doctor may be able to identify which species is causing the illness. Then an appropriate treatment can be prescribed.

STEMscopedia

What are the differences between unicellular and multicellular organisms?

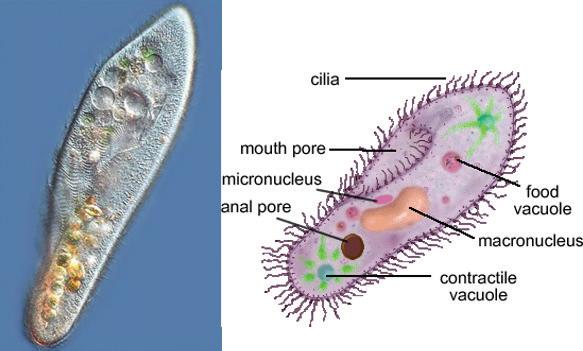

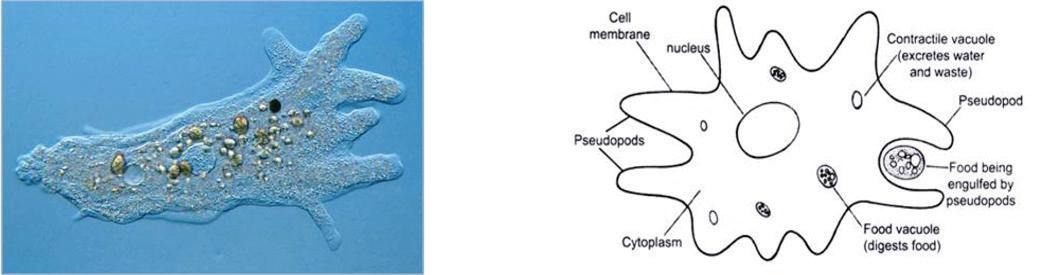

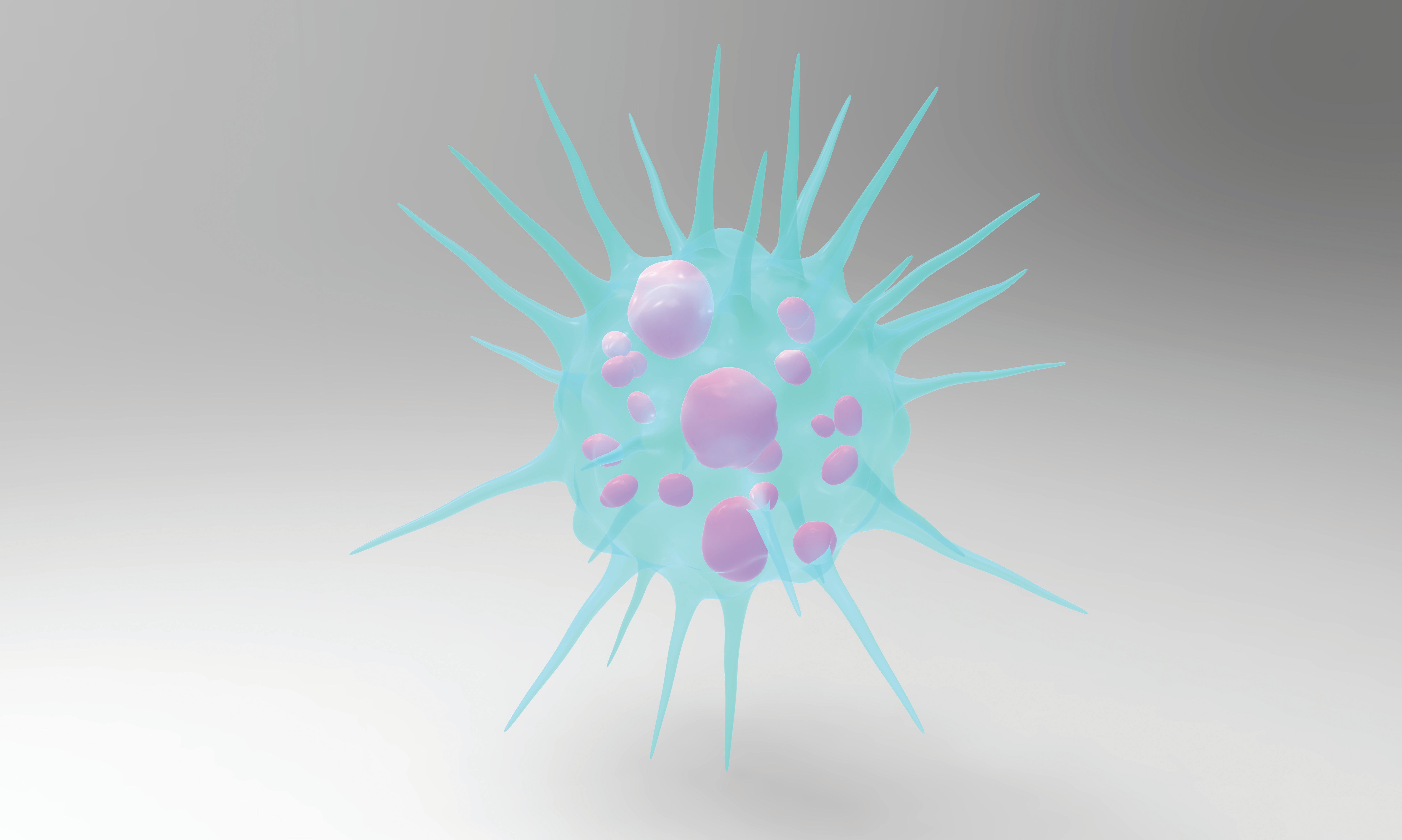

Unicellular: Unicellular means the organism is made up of just one cell, like bacteria or an amoeba. Both prokaryotes and eukaryotes can be one-celled organisms. Recall that prokaryotes do not have a nucleus or membrane-covered small structures called organelles.

Unicellular organisms include prokaryotes (bacteria) and eukaryotes (amoeba). However, multicellular organisms include only eukaryotes.

Look Out!

Multicellular: Multicellular refers to multiple cells organized into cells, tissue, organs, an organ system, and an organism. Multicellular organisms are made of more than one cell and do have a nucleus and membrane-covered organelles. All multicellular organisms are eukaryotic. As plants and animals evolved, a hierarchy of organization developed: Groups of similar cells grouped into specialized functions as tissues. Groups of tissue with similar function grouped together as an organ. Organs began functioning together as an organ system. Multiple organ systems began functioning together as a living organism.

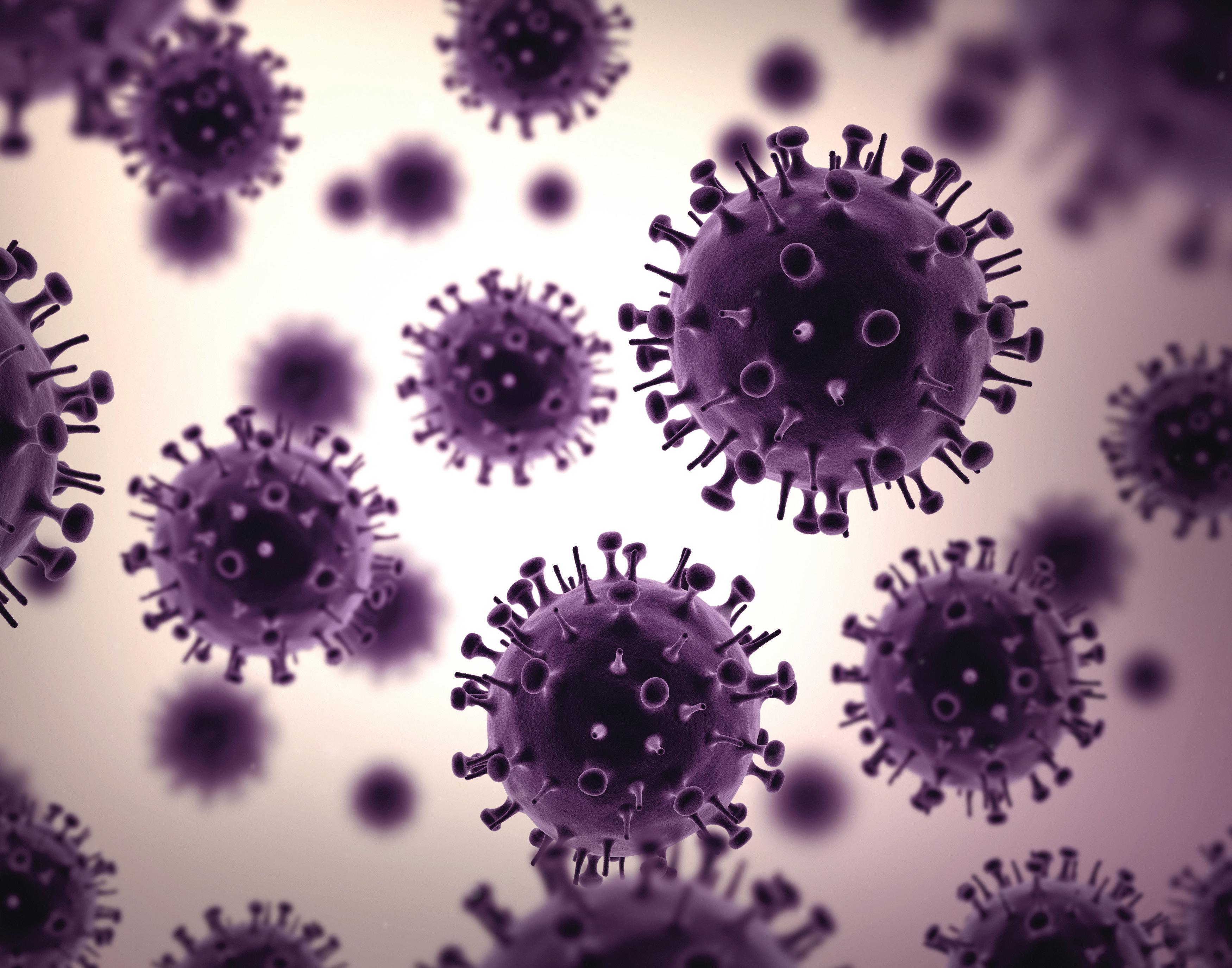

Viruses are not living things! Viruses are infectious agents that enter a host cell and use it to survive. Viruses do not have cell structure, which is the basis for life. Although they do have DNA, they cannot replicate without using the host cell. Viruses do respond to their environment, but they do not grow and cannot live on their own. Therefore, viruses are not alive. Examples of viruses are the common cold, smallpox, polio, rabies, chicken pox, and the AIDS virus.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

Scientists classify organisms in different ways. Scientists organize the living world using a process called taxonomy, which is the science of classifying organisms based on shared structures, functions, and relationships to other organisms.

For example, organisms can be classified based on their cellular structure. Organisms that have nuclei are eukaryotes. Eukaryotes also have organelles, or specialized structures bound in a membrane. Prokaryotes are organisms that do not have nuclei. Also, many unicellular organisms are in a different group than multicellular organisms. For example, bacteria are unicellular organisms. They are in a different group than animals, which are multicellular.

nuclei: plural for nucleus; part of a cell that holds structures that control cell activities

unicellular: made up of one cell

multicellular: made up of more than one cell

STEMscopedia

What Do You Think?

Take a look at the images below. Which organisms would you group together? Why? What additional information

would you need to know about the organisms to improve how you classified them?

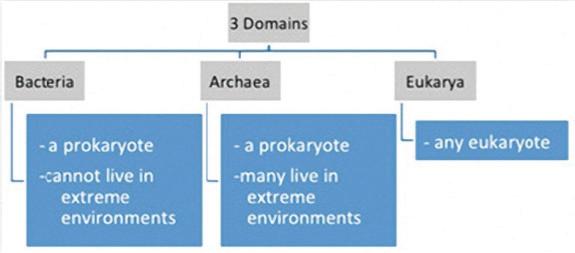

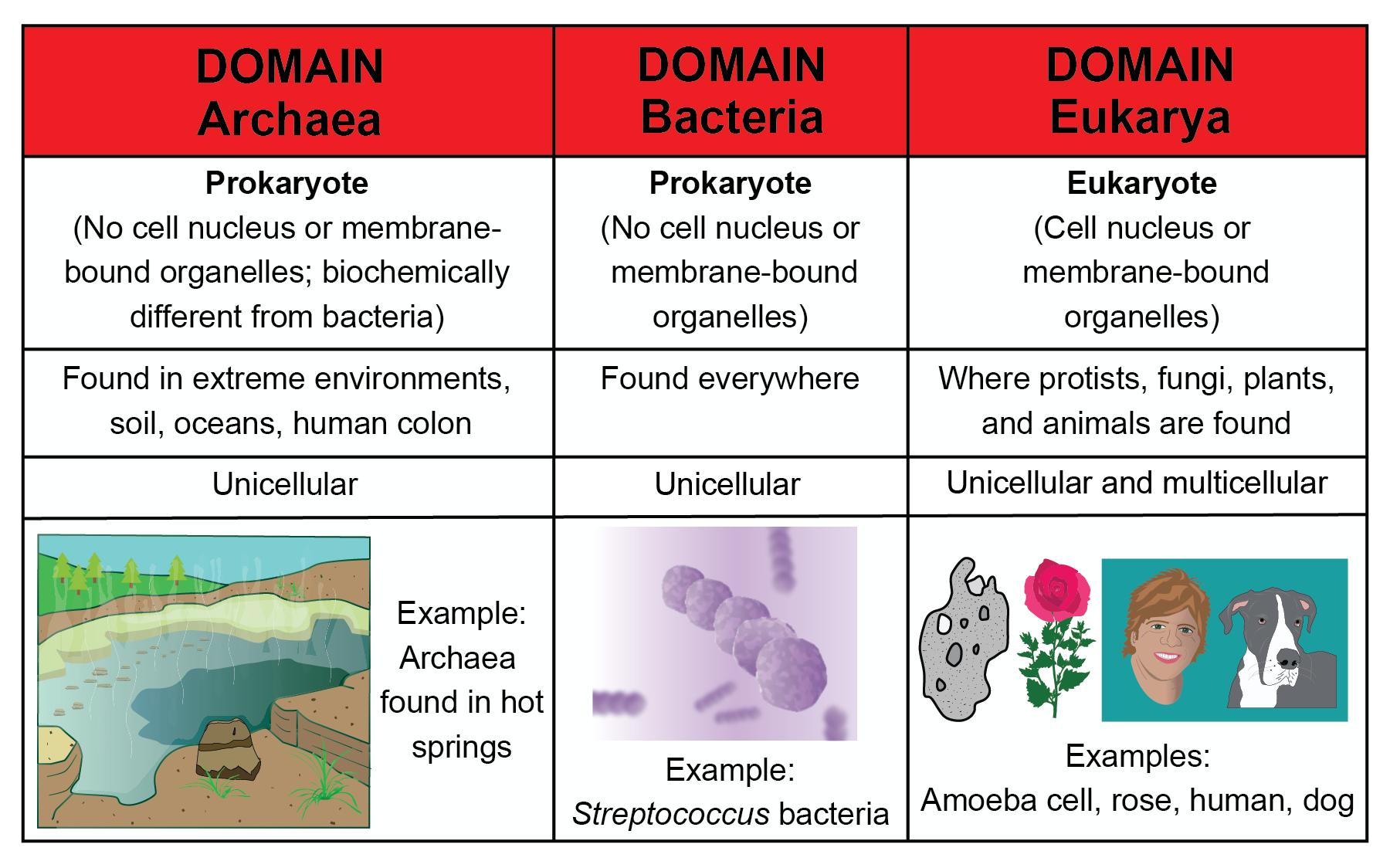

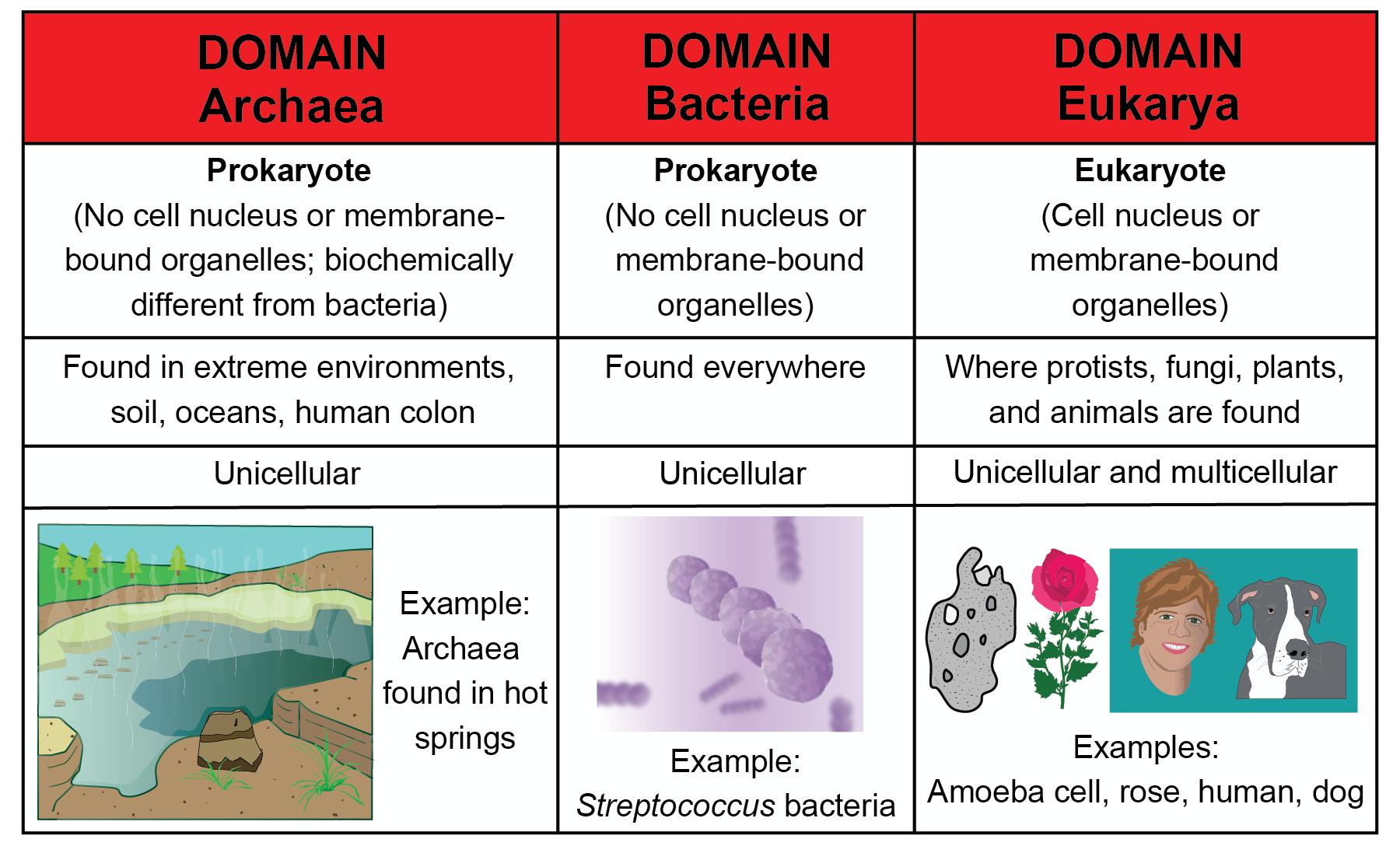

Scientists classify organisms into three domains. Scientists use a branching system of classification. The broadest group is the domain. Each domain is subdivided into kingdoms, followed by these subdivisions: phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. We will focus on domains and kingdoms.

All living organisms are classified into one of three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Domain Bacteria includes organisms commonly referred to as bacteria, which are unicellular prokaryotes. They are tiny organisms that reproduce asexually. Some bacteria are autotrophs (make their own food), but most of them are heterotrophs (consume their food).

STEMscopedia

The organisms in domain Archaea are a specialized group of unicellular prokaryotes. Scientists discovered these unique organisms living in areas of extreme conditions. Some archaea are found in hot springs and are called thermophiles (“heat loving”). Other archaea are found in very salty conditions and are called halophiles (“salt loving”). Similar to bacteria, archaea reproduce asexually. Some archaea are autotrophs, and others are heterotrophs. You might wonder why archaea and bacteria are divided into separate domains. After all, they are both unicellular prokaryotes. In the 1970s, a study revealed that the cellular structures of archaea were so different from bacteria they deserved their own domain. For example, archaea have a unique plasmid membrane structure not found in any other organisms.

Some of the first archaea were discovered in hot springs like this one. Hot springs are natural pools of extremely hot water.

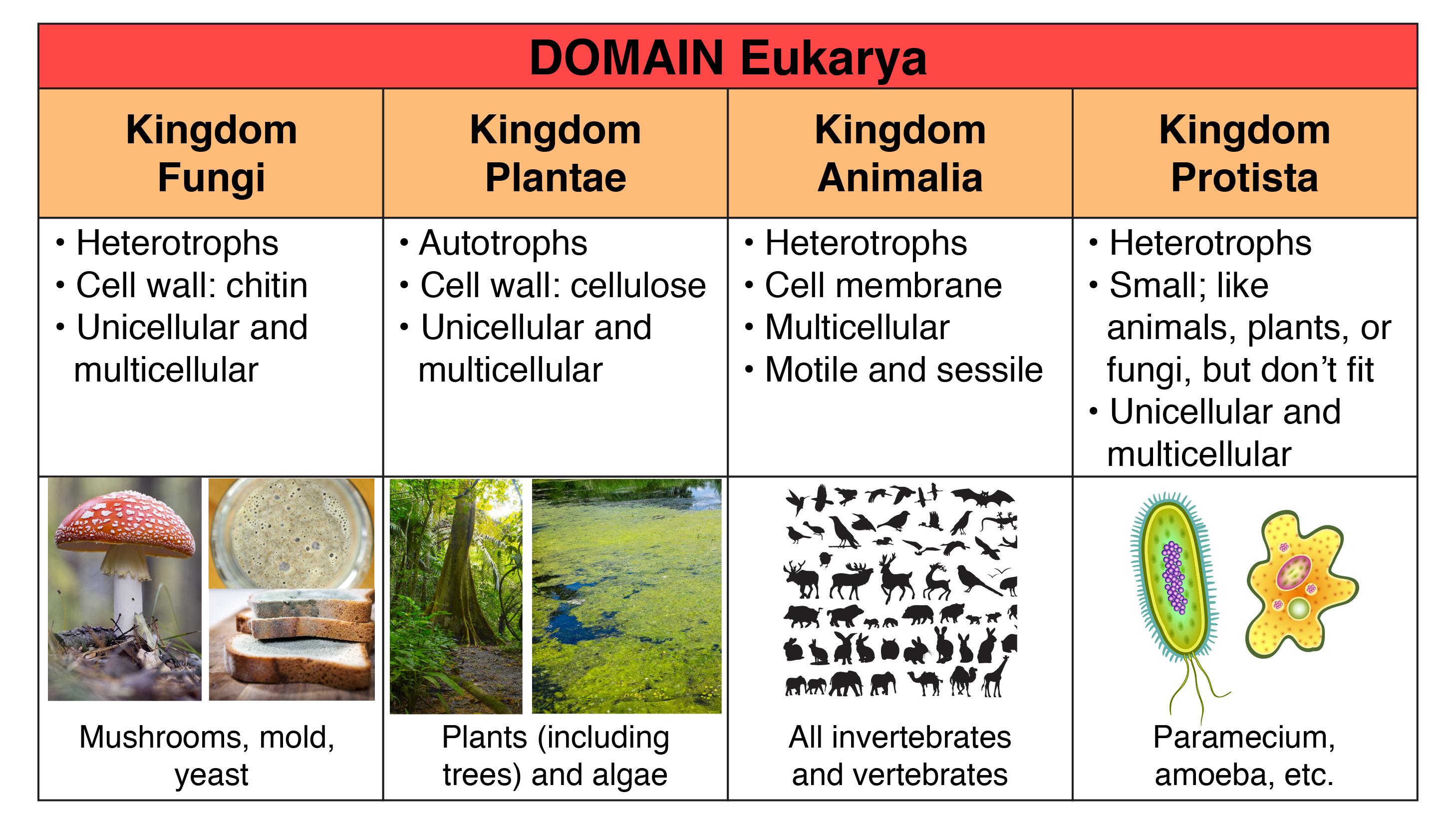

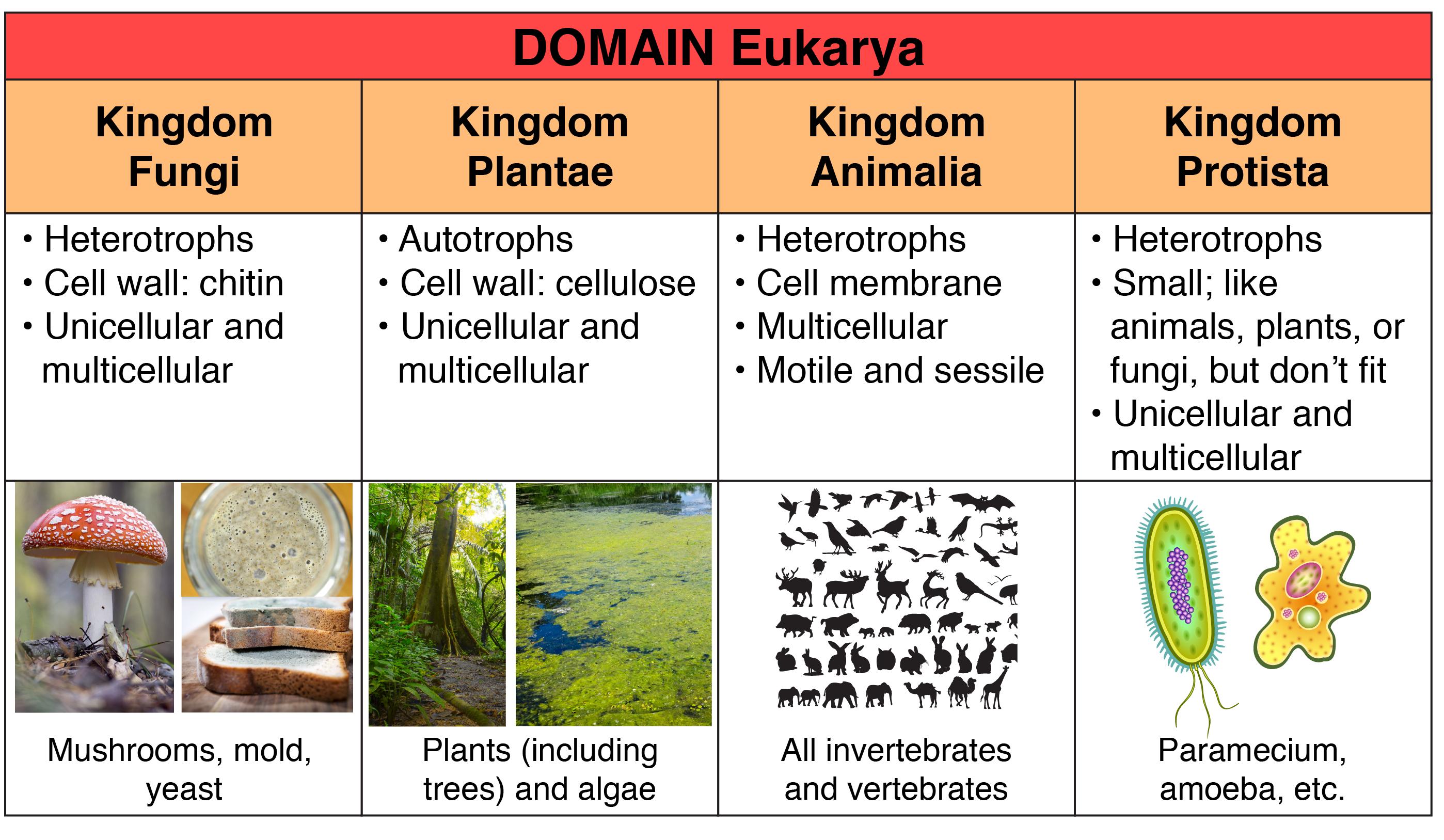

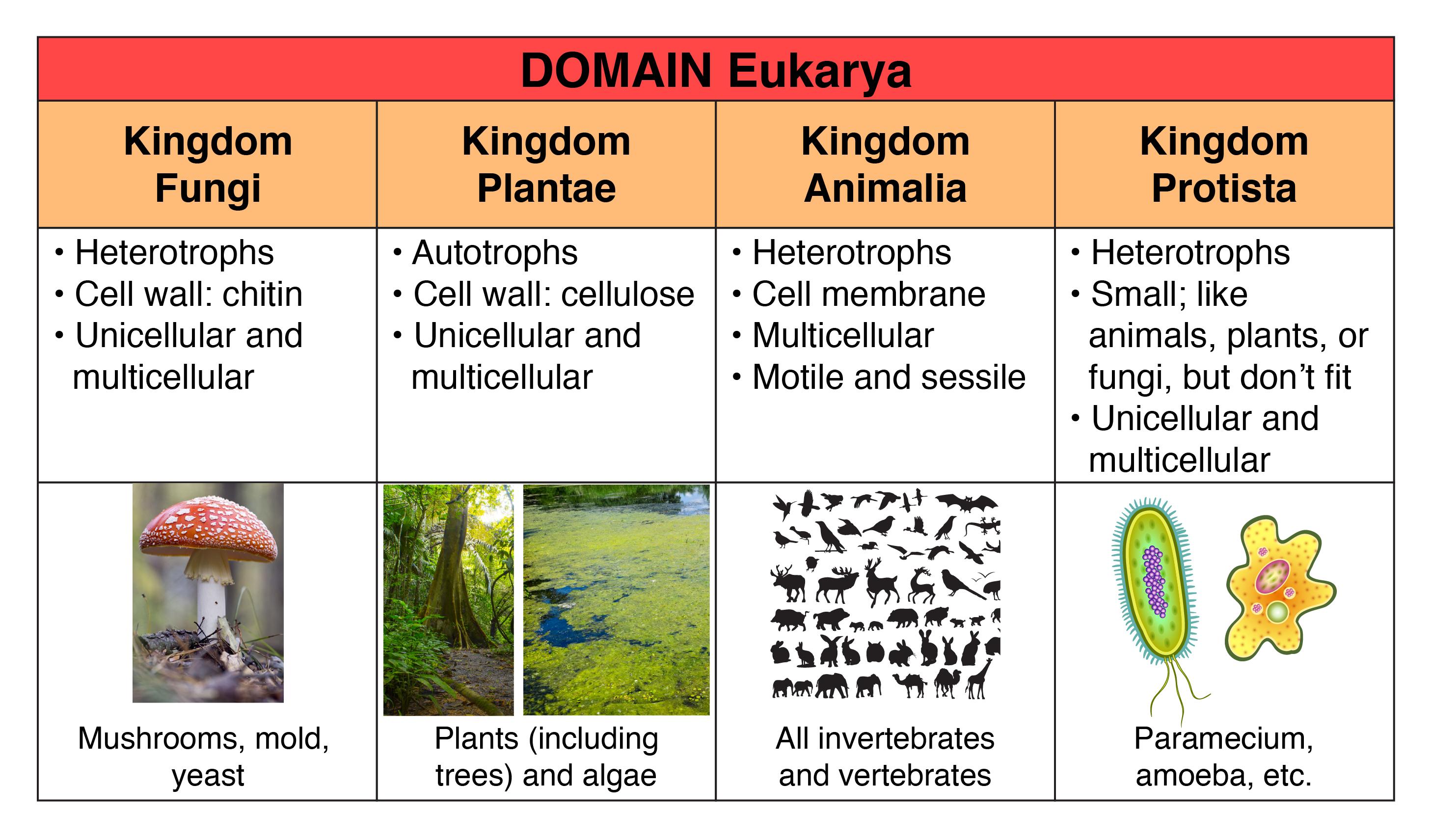

Domain Eukarya includes all eukaryotes. This is a diverse group of organisms. It includes plants, animals, fungi, and protists. These organisms are classified together because they are made up of eukaryotic cells. Characteristics like structure, function, and reproductive method further classify the organisms into smaller groups called kingdoms.

Scientists classify organisms into six kingdoms. The three domains are further divided into six kingdoms. The first two kingdoms are easy to remember. Domain Bacteria has just one kingdom: Eubacteria. Domain Archaea also has just one kingdom: Archaebacteria. Identifying the organisms in domain Eukarya is when classification gets more complicated.

Domain Eukarya has four kingdoms: Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, and Protista. They are classified based on the complexity of their cellular organization, their ability to obtain nutrients, and their mode of reproduction.

Organisms in kingdom Animalia are the most complex and are commonly referred to as animals. They are multicellular heterotrophs. Most reproduction in this kingdom is sexual, although a few animals can reproduce asexually. For example, if you divide a flatworm in half, each of the two halves will grow into a new flatworm.

Bacteria Eubacteria

Archaea Eukarya

Archaebacteria

Animalia

Protista Plantae

Fungi

The three domains are divided into six kingdoms.

STEMscopedia

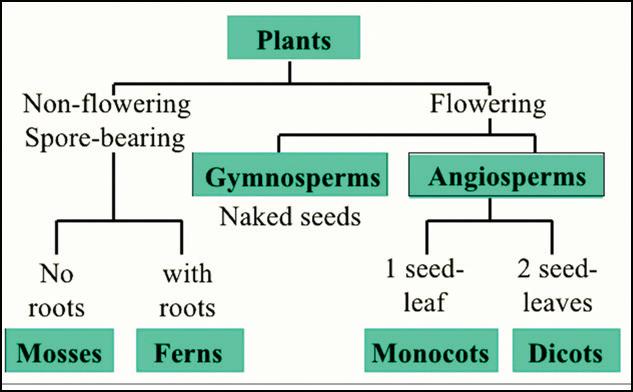

In the kingdom Plantae, the organisms are referred to as plants and are also very complex. Plants are autotrophs, since they make their own food. They are multicellular and can reproduce sexually or asexually.

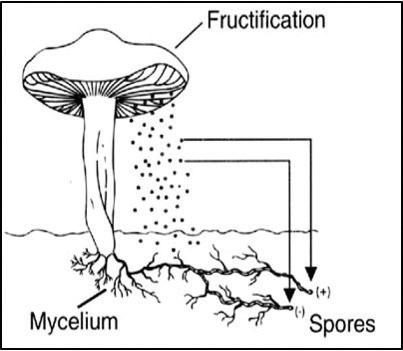

Kingdom Fungi includes organisms such as mushrooms and molds. Most fungi are multicellular and can reproduce sexually or asexually. All fungi are heterotrophs. However, the way in which they obtain food is unique. Fungi absorb nutrients from the environment. Think about a piece of moldy bread. The mold is a fungus that releases chemicals to break down the bread into smaller substances. The mold can then absorb these smaller substances, using them as nutrients. This characteristic makes fungi different from animals. The singular of fungi is fungus.

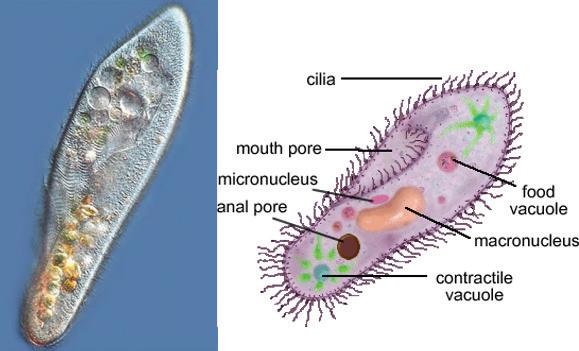

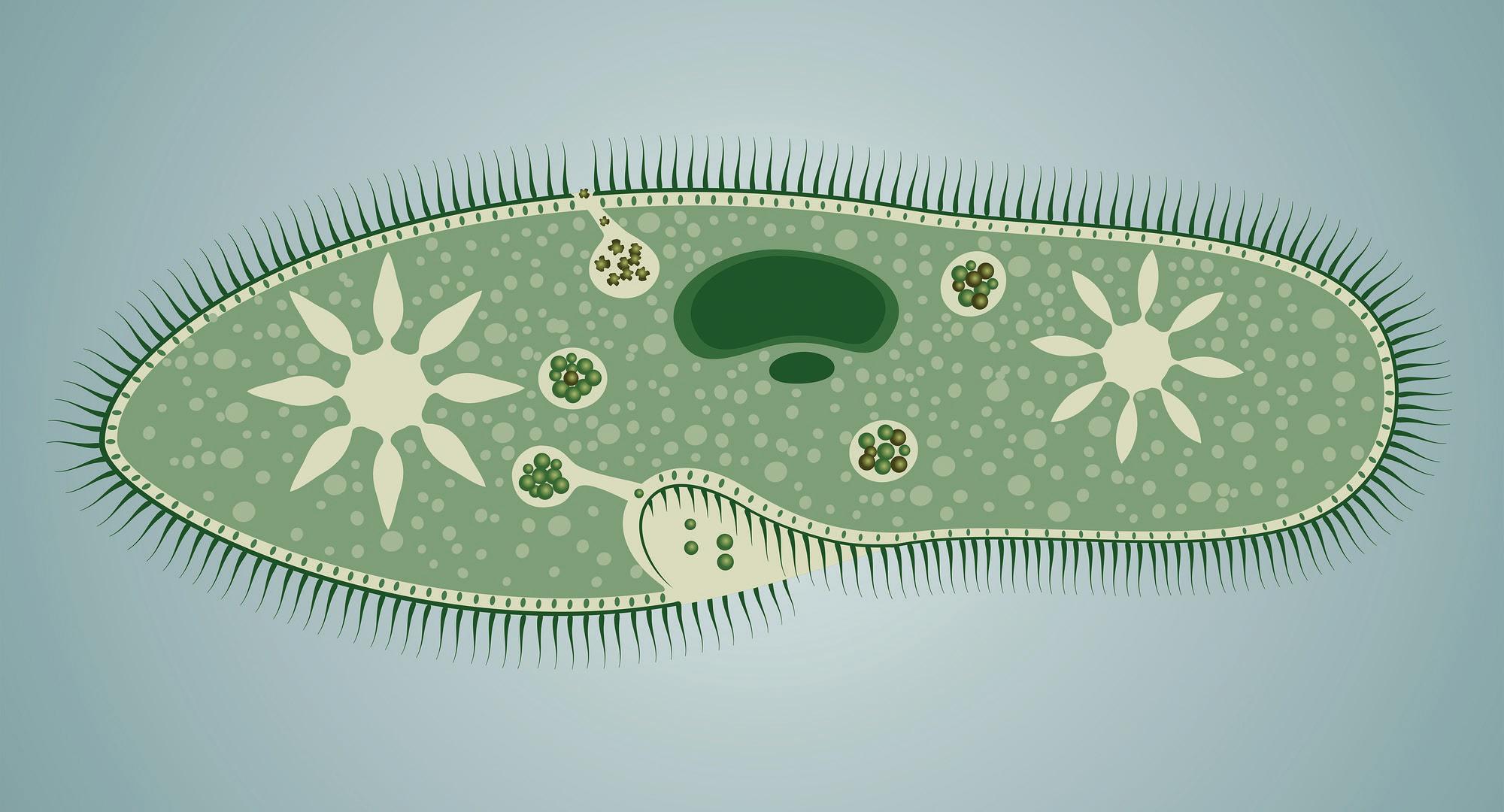

Kingdom Protista includes organisms with fairly simple structures compared to other eukaryotes. There is great diversity among the protists. Most of them are unicellular. However, some protists are multicellular. Some are autotrophs, in which case they resemble plants. Other protists are heterotrophs, more closely resembling animals. They swim through water and consume nutrients from their environment. Their simple organization keeps them in a separate kingdom from plants and animals.

Look Out!

The simple organization of seaweed places them in kingdom Protista.

Protists have been the most difficult group of organisms for scientists to classify. Some protists, like green algae, have the photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll that gives them a green color similar to plants. Other protists behave more like animals, with whip-like structures that allow them to zoom around in the water. You can think of protists as the “other” category. They are single-celled organisms with a nucleus, but their structures are too simple to qualify them as plants or animals.

Try Now

People often say that dogs are “man’s best friend.” How closely related are dogs and humans? To complete this activity, you will need a computer with Internet connection, a piece of paper, a pen or pencil, and crayons or markers.

STEMscopedia

Try Now

1.Search the Internet to find the taxonomies of the domestic dog and humans, from domain through species. Check at least three different sources to make sure the information you find is correct. Try using websites that end in .gov or .edu; they are usually reliable.

2. Create a chart listing the taxonomy of each species side by side, similar to the chart shown below.

Domestic Dog

Human

Domain

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

3. Circle classifications that are the same for dogs and humans using one color of crayon or marker. Circle the classifications that are different using another color of crayon or marker.

4. What does this information tell you about similarities and differences between dogs and people?

Discover Science: A Changing Classification System

The classification system we use today has changed many times over the years as new information has been discovered. Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus is known for creating the first version of the modern taxonomy system in the 1700s. He classified organisms into two kingdoms: Animalia and Plantae. Years later, as scientists were able to use better microscopes and observe organisms more closely, they added three more kingdoms to the system: Monera (unicellular prokaryotes), Protista, and Fungi. In recent years, the classification shifted again and is now the three-domain system you just learned about. The new system is based on information from cell studies and the fairly recent discovery of archaea. Do you think the system will change again in the future? If you answered yes, you are probably right! Scientists are always making new discoveries. Some of these discoveries will likely encourage them to rethink the current three-domain system.

STEMscopedia

Try Now

What Do You Know?

Think about the characteristics of prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells, and viruses. The table below has a list of terms. For each term, circle the category with which it is best associated.

Cell Structure

Mitochondria Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Unicellular Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Ribosomes Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Plant Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Virus Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Nucleus Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

DNA Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Multicellular Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Cell membrane Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Bacteria Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Dog Prokaryotic Eukaryotic

Classification Choice

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Virus

STEMscopedia

Connecting With Your Child

Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells in Your Neighborhood

Children remember information best when they are able to associate new information with familiar topics. Take your child for a walk in your neighborhood. Take turns playing “I Spy” to identify organisms you find. These may include animals, plants, and fungi. As you play the game, identify each organism as prokaryotic or eukaryotic. (All of the organisms you “spy” will be eukaryotic, as prokaryotic cells can be seen only with a microscope.) Be careful not to touch or otherwise disturb any organisms you observe.

Here are some questions to discuss with your child:

• Why did you find only eukaryotic organisms on your walk?

• Where might you expect to find prokaryotic organisms?

• Have you ever been sick because of an infection by a prokaryotic organism?

Your child might be tempted to classify organisms based on whether he or she can see them with the unaided eye or with a microscope only. It is important to stress that eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells are not classified on the basis of whether a microscope is necessary to observe them. Instead, the classification of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells is based primarily on whether the cell’s DNA is organized in a nucleus (eukaryotic) or whether it floats in the cytoplasm (prokaryotic).

Reading Science

Your Liver Is Your Friend

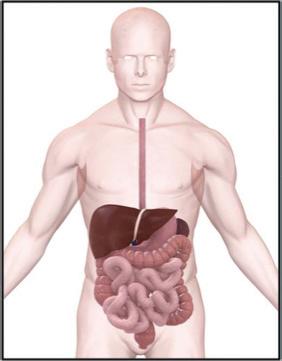

1 How do the levels of organization in biology create an entire biological system? When we study the biological world, we can see that every level is very complicated. Each part is organized, from the smallest atoms in an organism to the largest organism. In multicellular organisms (organisms with many cells, like us), atoms combine to make molecules, and molecules combine to make cells. Cells combine and work together to make tissues, like muscles. Tissues then work together in the form of organs, like your heart. Organs work together in organ systems, like your digestive system. In other words, all of the parts work together to create a whole.

2 One of the most important levels of organization relates to the different organ systems in our bodies. Each organ system performs an important function, such as helping with digestion, moving materials through the body, or breathing. Healthy organ function depends on the health of each of the cells of that organ and on the health of each organ and its cells. If one organ fails, the entire organism could die. This makes the organ system a good point to start the study of the levels of biological organization.

3 One of the most important organs in animal systems is the liver. It helps to maintain the balance of the entire organism. Its functions are tied to almost every other organ of the animal body. The liver is found in all animals with skeletons (vertebrates). While each vertebrate’s liver is slightly different, it is always one of the largest internal organs.

4 There are many reasons why the liver is so important. Your liver will pick up signals from molecules and blood cells and will respond as needed. This makes your liver the largest chemical-processing center in your body. It turns the carbohydrates (sugars) you eat into molecules that your body can use, releasing sugars back into your body as needed. The liver makes the building blocks of proteins, called amino acids. The liver also affects the function of the circulatory system. It creates necessary blood proteins, such as clotting factors. It also produces cholesterol, which your cells need to makes hormones and parts of cell membranes.

5 It also plays an important role in the breakdown and disposal of toxins, such as ammonia, damaged red blood cells, and other cell waste. The liver produces a thing called bile that helps break down the fats in the foods you eat. If your liver stops functioning properly, it can no longer break down this waste product. Vomiting bile, as the body attempts to get rid of unprocessed waste products, is another sign. The liver performs so many important functions that an animal would die within 24 hours if the liver stopped functioning. The good news is that the liver has an amazing ability to heal and repair itself.

Reading Science

1 Paragraph 1 talks about how the parts of biological organisms work together. Which of the following is the correct order?

A Cells, organs, molecules, tissues, atoms

B Molecules, cells, tissues, atoms, organs

C Atoms, molecules, cells, tissues, organs

D None of the above

2 In the biological order of systems, cells will combine to form–

A organs.

B bodies.

C tissues.

D molecules.

3 The word vertebrates is found in Paragraph 3. This word means–

A animals with cells.

B animals with organs.

C animals with livers.

D animals with skeletons.

Reading Science

4 In vertebrates, which biological system carries out more chemical reactions than any other organ or system?

A The liver

B The heart

C The digestive system

D The blood system

5 What does bile do?

A Breaks down the sugars in your body

B Breaks down the fats in the foods you eat

C Creates the proteins in your body

D Removes the toxins from your body

6 The liver is essential to the health of the organism. One major function of the liver is–

A to break down toxins.

B to make cholesterol.

C to make amino acids.

D all of the above.

Open-Ended Response

1. How can scientists determine whether a newly discovered object should be classified as living or nonliving?

2. Scientists examine a newly discovered object and discover that it is, indeed, made up of smaller parts. What must the smaller parts do in order for the object to be classified as living?

Open-Ended Response

3. Compare and contrast bacteria and viruses. Why are bacteria considered living things, but viruses are not considered living things?

BACTERIA

VIRUSES

Open-Ended Response

4. How are multicellular organisms organized?

5. Compare a car to a person. Choose a system in the car, compare it to a system in the human body, and explain how the two systems are similar.

Write a scientific explanation that describes the difference in roles between cells in a unicellular organism and cells in a multicellular organism. Scenario

A unicellular organism is a living thing made of only one cell, while a multicellular organism is a living thing made of more than one cell.

Peer Name: Rebuttal:

Parts of Cells

Think about a single cell and its parts—for example, a cell inside the human body. Now, select an everyday object that could be used as a model for a cell and its parts. In words and/or pictures, describe your model and how it is like the cell.

Explore 1

Designing a System

Activity

A sports team, business office, manufacturing plant, organism, and even individual plant and animal cells are all examples of different kinds of systems.

L.6.1.3

Although there are different kinds of systems that exist, they share certain characteristics. A system consists of one or more parts, or components, such as a “control center” that directs the system’s activities, basically coordinating all of the different parts to help make sure they work together smoothly. Each part of the system is assigned certain tasks, but together, the whole system has a generally shared purpose. For a sports team, it is to score the most points to win the game. For a business office, it is to fill customer needs. For a manufacturing plant, it is to keep the production line running smoothly and efficiently. For organisms and cells, it is to keep their systems functioning and healthy.

Procedure

1. Within your group, come up with one business idea for manufacturing a specific product.

2. Develop a flowchart that breaks down each component in a facility that is needed for the manufacturing process to occur. Make sure that each step includes a description of a) the inputs and outputs (e.g., raw materials or subproducts, energy source, waste, storage) and b) the processing needed. Processing points should include detailed descriptions of either the equipment or a person’s skills needed to complete that processing step.

Explore 1

3. On a large sheet of paper, transfer your manufacturing process to a floor plan format. The floor plan of your manufacturing plant should include an outer wall, one or more entry/exit points, a central administration office, and labeled areas with a short description about what is happening in that area—that is, the inputs/ outputs and processing.

4. Pair up with another group. Using your floor plan for reference, take about five minutes to explain your system to the other group.

5. Review the set of Organelle Labels, which name and describe the functions of different kinds of parts in animal and plant cells. Analyze the other group’s system diagram and stick each label on the system’s component that you think it best matches in terms of its function category. As needed, use the sticky notes to duplicate labels (with just the organelle name) and place in additional corresponding spots on the floor plan. When done, the group that placed the labels should explain to the other group why they put them in the spots they did.

L.6.1.3

Explore 2

Comparing Cells

Use the reference sheet to describe the various types of eukaryotic cells.

Animal Plant

1. Does this cell look simple or complex?

2. What organelles do you see present in this organism?

1. Does this cell look simple or complex?

2. What organelles do you see present in this organism?

3. What features make this cell type unique?

3. What features make this cell type unique?

Protist

1. Does this cell look simple or complex?

2. What organelles do you see present in this organism?

1. Does this cell look simple or complex?

2. What organelles do you see present in this organism?

3. What features make this cell type unique?

3. What features make this cell type unique?

Explore 2

Use the microscopes to observe samples of cells. Draw and describe what you see to determine the type of cell on each slide.

Slide:

Observations

Slide:

Observations

Type

Explore 2

Slide: Slide:

Observations

Observations

Organelles

Organelles

Cell Type

Cell Type

Explore 2

Reflections and Conclusions

Complete two Venn diagrams to compare and contrast the characteristics of the cell types. Plant

STEMscopedia

Reflect

Think for a moment about all the living things on Earth. There is great diversity among organisms, from microscopic bacteria to massive blue whales, the largest animals on the planet. Despite the tremendous variety of life, all organisms have something in common—they are all made of cells. Some organisms are unicellular, composed of just a single cell, while other organisms are multicellular, composed of more than one cell. The human body is made of about 100 trillion cells!

Although different cells can perform specific functions, all cells can be divided into two large categories. What do you think these categories might be? What are the characteristics of the cells in each category?

Structure and Function of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

The two categories of cells are prokaryotic cells and eukaryotic cells. A prokaryotic cell is a simple cell that does not contain a nucleus or other membrane-bound organelles.

A prokaryotic cell is typically defined by its shape, which may be rod-like, spherical, or spiral. Prokaryotic cells are unicellular organisms, bacteria, and archaea. Although they lack membranebound organelles, prokaryotic cells have some or all of the structures referenced in the table below. Can you locate each structure in the diagram at the top right of the page?

Structure

In addition to the structures shown, prokaryotic cells contain a central area around the DNA called the nucleoid.

archaea:

single-celled organisms that sometimes live in extremely harsh environments such as hot springs and salt lakes

Prokaryotic Cell Structures

Function

Capsule The capsule is the thin, outermost layer of the cell that provides protection.

Cell wall The cell wall surrounds the cell and maintains the cell’s shape.

Plasma membrane Individual membranes do not surround internal structures. However, a single plasma membrane surrounds the entire cell. The membrane helps move materials into and out of the cell.

Cytoplasm Prokaryotic cells contain a gel-like fluid called cytoplasm. Cytoplasm takes up most of the space inside the cell.

Accelerate Learning Inc. – All Rights

STEMscopedia

Reflect

DNA

Nucleoid

Plasmids

Ribosomes

Pili

Flagella

DNA within a prokaryotic cell is a single, circular molecule that is not enclosed in a membrane-bound compartment. DNA carries the instructions and genetic code for the cell.

Although DNA is not enclosed in a nucleus, it is generally confined to a central region called the nucleoid.

Plasmids are circular genetic structures found inside prokaryotic cells but are not part of the main DNA strand. They are involved in cell activities such as growth and metabolism.

Prokaryotic cells contain ribosomes that play roles in manufacturing proteins.

Hollow, hair-like structures called pili surround prokaryotic cells. Pili enable prokaryotic cells to attach to other cells.

Long, whip-like structures called flagella (singular: flagellum) help prokaryotic cells move. A cell may have one flagellum, or it may have several flagella.

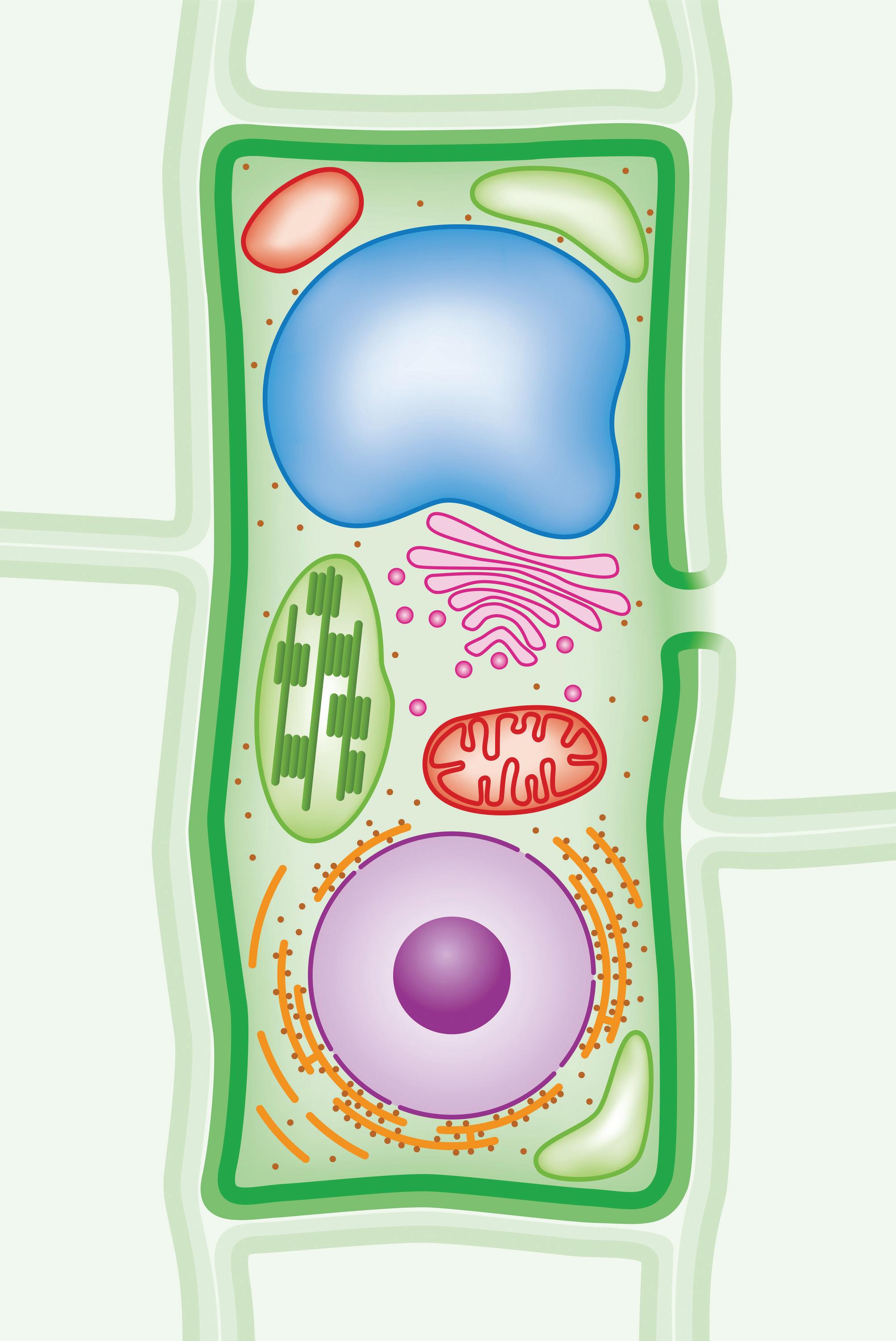

In contrast to prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells are more complex. They contain a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles that perform specific functions that contribute to the overall metabolism and growth of the cell. Eukaryotic cells are found in multicellular organisms including plants, animals, fungi, and protists. They can also be unicellular protists. Let us take a closer look at the main structures within a eukaryotic cell. Can you locate each structure in the diagram on the right?

metabolism: the process by which cells make, store, and transport chemicals

In addition to the structures shown in this animal cell, plant cells contain a cell wall, a central vacuole, and chloroplasts.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

Structure

Cell wall

Cell membrane

Cytoplasm

Nucleus

DNA

Mitochondria

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

Golgi body

Ribosomes

Lysosomes

Chloroplasts

Central vacuole

Vesicles

Eukaryotic Cell Structures

Function

The cell wall surrounds the cell and maintains its shape. Cell walls are found only in plant, fungal, and protist cells.

The cell membrane surrounds the entire cell. It helps move materials into and out of the cell.

As in prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells contain cytoplasm that takes up much of the space inside the cells.

The nucleus is the central organelle that holds DNA.

In eukaryotic cells, DNA is linear and organized into chromosomes. Like prokaryotic cells, DNA carries the instructions and genetic code for the cell.

The mitochondria play major roles in transforming the energy in food into a usable form of energy called ATP. The cell then uses ATP to carry out activities such as reproduction and growth.

The endoplasmic reticulum, called the ER, helps to transport proteins and to produce lipids

The Golgi body helps package and distribute proteins and lipids within the cell.

Like prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells contain ribosomes that play roles in manufacturing proteins. However, the ribosomes in eukaryotic cells are larger and more complex.

Lysosomes contain enzymes that help break down food or break down the cell when it dies.

Plant cells and some protists contain chloroplasts. These structures contain the green pigment chlorophyll, which captures the energy of sunlight for use in photosynthesis

Many plant cells contain a large central vacuole, which stores water, food, and waste. Animal cells contain vacuoles, but they are much smaller than the central vacuole found in plant cells.

These bubble-like structures encapsulate materials to transport them in and out of the cell.

STEMscopedia

What Do You Think?

Scientists classify organisms into three domains.

All living organisms are classified into one of three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Domain Bacteria includes bacteria, which are unicellular prokaryotes. They are tiny organisms that reproduce asexually. Some bacteria are autotrophs (make their own food), but most of them are heterotrophs (consume their food).

DOMAIN Archaea DOMAIN Bacteria

Kingdom

Archaebacteria

Archaebacteria

Prokaryotes

Unicellular

Live in extreme environmnents (hot springs, underwtaer thermal vents)

No nucleus

Kingdom Bacteria (or Eubacteria)

Circular DNA Bacteria

Prokaryotes

Unicellular

Live everywhere, but not in extreme environments

No nucleus

Circular DNA

Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, and Protista

They are classified based on the complexity of their cellular organization, their ability to obtain nutrients, and their mode of reproduction.

Scientists further classify organisms into kingdoms

The three domains are further divided into six kingdoms. The first two kingdoms are easy to remember. Domain Bacteria has just one kingdom: Eubacteria. Domain Archaea also has just one kingdom: Archaebacteria Domain Eukarya has four kingdoms:

STEMscopedia

Try Now

What Do You Know?

Compare prokaryotic cells and eukaryotic cells. Read the list of cell characteristics in the box below. Write each characteristic in the correct place on the Venn diagram.

Characteristics of Cells

• Contain a nucleus

• Undergo metabolism

• Contain DNA

• Are usually smaller than 10 micrometers

• Are found in fungi

• May contain a cell wall

• Reproduce

• Are bacteria and archaea

• Contain membrane-bound organelles

• Are found in all multicellular organisms

• Contain chloroplasts

Prokaryotic Cells Eukaryotic Cells

STEMscopedia

Connecting With Your Child

To help your child learn more about prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, have him or her draw or create a threedimensional model of each cell type. For eukaryotic cells, ask your child to choose either a plant cell or an animal cell.

If your child is drawing the cells, have your child use colored pencils to sketch the cells and their structures. He or she should include labels and list the functions of each structure.

If your child is creating three-dimensional models, help brainstorm ideas of materials that can be used, such as pipe cleaners, wax craft sticks, pom-poms, and string. Three-dimensional models should also include labels. Your child can use toothpicks, tape, and small pieces of paper to create numbered labels. Then he or she can create a written numbered key on a sheet of paper. For example, a toothpick taped with the number 1 can be placed on the nucleus. The written key would indicate that number 1 is a nucleus and is the centrally located organelle that contains DNA.

Here are some questions to discuss with your child:

• Which type of cell was easier to create a model for, prokaryotic or eukaryotic? Why?

• What are some types of prokaryotic cells that you could observe under a microscope? Do you think you would be able to see all of the structures? Explain.

• What are some types of eukaryotic cells that you could observe under a microscope? Do you think you would be able to see all of the structures? Explain.

Reading Science

Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

1 The cell, the basic unit of life, is found in every living organism on Earth. Some organisms are unicellular, or made of a single cell. Other organisms are multicellular, or made of many different types of cells. It is important to note that whatever cell type it is, all living biological cells have many things in common.

2 All living cells are bound by a plasma membrane. Within that membrane, all cells contain a fluid known as cytosol. Cytosol is where organelles are found. All living cells also contain ribosomes, one type of organelle, which make proteins. There are two major types of cells: prokaryotic cells and eukaryotic cells.

3 Most prokaryotic organisms are unicellular. They are very simple with no membrane-bound organelles. In prokaryotic cells, the DNA is loose and is found in an area called the nucleoid. Prokaryotic cells are surrounded by a cell wall. These cell types usually reproduce asexually.

4 Most eukaryotic organisms are multicellular. These cells usually have many membrane-bound organelles, each with its own structure and function. The DNA in eukaryotic cells can be found on chromosomes within a membrane-bound nucleus near the center of the cell. Some eukaryotic cells, such as those found in plants, fungi, and some protists, have cell walls outside their plasma membranes. These cell types usually reproduce sexually.

5 How are cell types identified and measured? One way is to look at the cell through a microscope lens on medium power of 100x. If any details of the cell can be observed at medium power, it is most likely a eukaryotic cell. Most prokaryotic cells cannot be seen without a higher-powered lens due to their very small size. On average, eukaryotic cells are 10 times larger than prokaryotic cells. Some eukaryotic cells can even be seen with the naked eye. For example, if an average prokaryotic cell was the size of a pea, then an average eukaryotic cell would be the size of a medium grapefruit.

6 Because of this great size difference, prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have different ways of moving materials through the cell. Materials inside prokaryotic cells move mainly by diffusion. Diffusion is like using bicycles or cars to move people around a small town. Eukaryotic cells, on the other hand, move materials in a similar way as mass transit in a large city like New York City or Los Angeles. Why? Because diffusion alone cannot move materials around these larger cells fast enough. Their bigger volume needs much more organization. Many membrane-bound organelles do separate, specialized jobs to move materials where they need to go.

Reading Science

1 Why can’t eukaryotic cells only use diffusion to transport materials around the cell?

A Eukaryotic cells are too small.

B Eukaryotic cells have no membranes.

C The materials cannot move fast enough in these cells.

D The organelles all do the same job.

2 What cell type has no membrane-bound organelles, has DNA that is found in an area called the nucleoid, and is very small?

A Eukaryotic cell

B Prokaryotic cell

C Animal cell

D Plant cell

3 A student is looking through a light microscope and wants to know what type of cells she is seeing. She can only see separate cells with 100x magnification. What type of cell is it? How much detail would she see?

A Prokaryotic cell, no detail

B Prokaryotic cell, some detail

C Eukaryotic cell, no detail

D Eukaryotic cell, some detail

Reading Science

4 A student is looking through a microscope at stained cells. The cells have outer edges and many smaller parts inside. What type of cells would he expect these to be? Why?

A Prokaryotic, because only prokaryotic cells have cell walls.

B Prokaryotic, because prokaryotic cells have ribosomes inside.

C Eukaryotic, because only eukaryotic cells have cell walls.

D Eukaryotic, because only eukaryotic cells have a nucleus and organelles.

5 Which organelle would not be found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells?

A Cytosol

B Nucleoid

C Ribosomes

D Plasma membrane

6 Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have several differences. Which statement below is NOT one of those differences?

A The DNA in prokaryotic cells is loose in the nucleoid.

B Eukaryotic cells have many separate organelles.

C Only prokaryotes have ribosomes.

D Eukaryotic cells may be 10 times larger than prokaryotic cells.

Open-Ended Response

1. Imagine a cell is a candy factory. What would each cellular component be in the candy factory? Why?

• Cell membrane:

• Cell wall:

• Nucleus:

• Chloroplast:

• Vacuole:

• Mitochondria:

2. Summarize how the functions of a cell are similar to the functions of an organism.

Open-Ended Response

3. Describe the structure and function of an organelle found in the cell of a plant that is not found in the cell of a fungus.

4. Observe the cell in the picture. Would you classify it as the cell of a plant, animal, fungus, or bacteria? How can you tell?

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

Claudia is a student in a middle school science classroom. She made a list of cellular structures and functions as a homework assignment for her science class. She decided to leave out the lysosome because she felt it was not important enough. The lysosome is the structure within the cell that breaks down unwanted material within the cell.

Cell memebrane Controls what enters and leaves the cell

Mitochondrion Breaks down nutrients into energy

Nucleus The control center of the cell

Vacuole Stores water, waste, and food

Cytoplasm Holds organelles in place within the cell

Ribosome Produces proteins

Golgi body Packages proteins

Write a scientific explanation agreeing or disagreeing with Claudia’s opinion that the lysosome is not important enough to include in her list.

PEER EVALUATION

Peer Name: Rebuttal:

3.2, and 3.3

Explore 1

Defining Biotic and Abiotic

Activity

1. Record what you observe in the photograph of the pond.

2. What interactions do you see in this photograph? What organisms may be working together?

3. Fill in the chart below using the photograph.

4. Which do you think is more important to an ecosystem, the biotic or abiotic elements? Why?

Organization and Interactions in an Environment

Background

1. What is a species? Provide an example.

2. What is the purpose of utilizing the levels of organization within an ecosystem?

3. What level of organization includes the abiotic factors?

4. How can developing a model help facilitate the understanding of the levels of organization?

5. In the triangle below, identify all parts of the levels of organization from your biome. Include an example of items that would be found at each level of organization from species to biome.

Explore 2

Part I: Planning Model

1. My Question of Inquiry:

2. What do you need to do to answer the question?

3. What are the variables that you will observe?

4. What materials, equipment, and technology will you need for this investigation?

5. What limitations can you identify with this model?

Explore 2

Explore 2

Analyze Data

1. What is your biome? What abiotic factors impact your ecosystem?

2. What materials can be used to develop your model of your ecosystem? How can these materials help to improve the accuracy of your model?

3. Compare your ecosystem to that of another group. Identify the differences. Why would their ecosystem be different?

4. Using your model, explain how your ecosystem could look different six months from now. Explain, including information about the abiotic and biotic factors.

5. If one of the organisms in your ecosystem were removed, what impact would that have on the other organisms in the same ecosystem?

6. Describe any limitations to your model of the levels of organization.

Explore 2

Part III: Reflections and Conclusions

1. What are the levels of organization within an ecosystem?

2. Were there limitations to consider when developing a model for the levels of organization? Explain.

3. How can you use your model and other students’ models to help facilitate an understanding of the levels of organization?

4. What would you do differently if you were to conduct this investigation again?

Explore 2

5. Fill in the following levels of organization triangles utilizing other groups’ models.

Ecology and Interdependence, Part I: Invasive Species

An isolated island ecosystem has the following food chain: grass → grasshopper → frog → snake

Four students were asked to predict what would happen to an ecosystem if an invasive species were introduced. Their responses are recorded below.

Event Description

1 Humans introduce kudzu (an Asian vine that grows very quickly).

2 Kudzu bugs, which thrive on kudzu, inhabit the isolated island’s ecosystem.

3 The native grasses cannot compete with the kudzu vines for resources and begin to die off.

The frog population would adapt to eat the vine. The grass in the ecosystem would grow more rapidly. The grasshopper population would increase. The frog population would increase.

Explore 3

1. Out of the four students’ responses, which one do you agree with the most? Explain your thinking.

2. Based on the events listed in this ecosystem, how would you define an invasive species?

3. How has the introduction of kudzu impacted this ecosystem?

4. Besides the introduction of an invasive species, what is another way an ecosystem can change?

Explore 3

Ecology and Interdependence, Part II: Natural Disasters

Activity

Large areas and their ecosystems are commonly disrupted by a variety of events. Catastrophic events, such as hurricanes, can rip apart the homes of humans, plants, and animals. The effects of this shake-up are predictable to some degree, but sometimes unknown variables cause further disruption and become apparent later. The scenarios you will explore during this activity feature major catastrophic events that can cause disruption to ecosystems.

Procedure

1. Review and analyze the Before and After in the Student Reference Sheet.

2. For each of the scenarios, answer the following questions.

• Based on what you know or have heard about this type of disruptive event, explain what generally happens as part of the nature of that event.

• What effects can the event have on abiotic factors of the ecosystem?

• What immediate effects did the event have on the plants that lived there?

• What immediate effects did the event have on the animals that lived there?

• What do you predict will happen over time in the affected area?

Explore 3

3. Pick one of the scenarios and draw a time line. Based on your answers, fill in the time line with some details. Use a combination of text and drawings to help illustrate the scenario and the area’s response over time.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

You wake up early on a Monday morning. You grab something to eat and drink and then go outside to catch the bus. When you arrive at school, you suddenly remember that you forgot to do part of your homework!

You find a classmate, and she helps you finish a few science questions. Then you both head into class, where your teacher is starting the school day.

organism: a living thing

From the time you woke up until the time you started class, you were interacting with your environment. Any behavior that causes something to affect something else is called an interaction. You ate food, drank liquids, breathed air, and relied on other people for help. In the same way, organisms interact with their environment every day.

These interactions help organisms survive. What are some things organisms might interact with? Are they living or nonliving? Can you think of some ways in which organisms interact with each other?

What Do You Think?

What is an ecosystem? What are the different parts of an ecosystem?

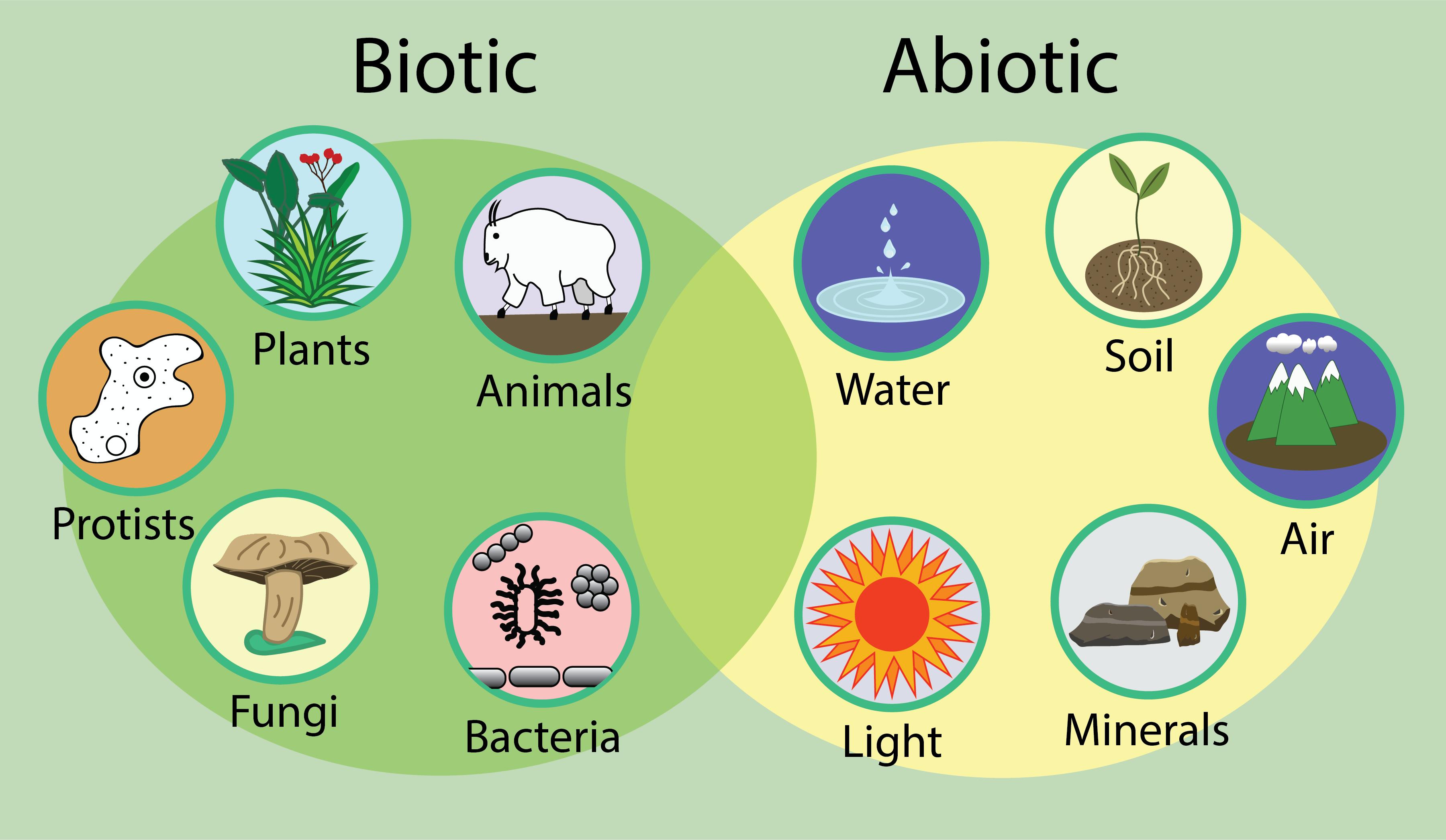

An ecosystem is a community made up of biotic (living) and abiotic (nonliving) things in an environment interacting with each other. Nonliving things do not grow, need food, or reproduce. Some examples of important nonliving things in an ecosystem are sunlight, water, air, minerals, and soil. Living things grow, change, produce waste, reproduce, and die. Some examples of living things are all organisms such as plants, animals, fungi, protists, and bacteria. Organisms interact with the living and nonliving things in their ecosystem to survive.

STEMscopedia

Levels of Biological Organization

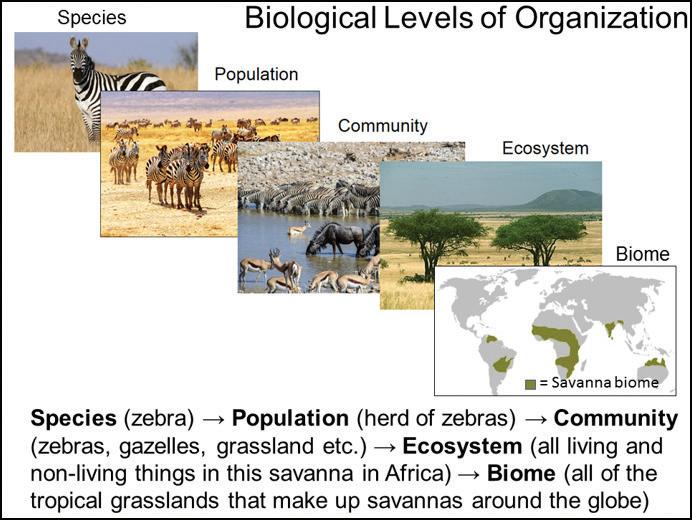

Biologists designate different levels of organization of the natural world into species, populations, communities, ecosystems, and biomes.

Species: Species are individual organisms that are self-replicating systems and maintain homeostasis (the balance of internal processes that make life possible) by responding to external stimuli. These individual organisms have common characteristics unique to their species. There are over eight million different species of living things. A zebra, giraffe, and fly are examples of different species.

Populations: Groups of interacting organisms of the same species are called populations. A population of organisms may be spread out within the ecosystem or exist together in the same area in an ecosystem, such as a herd of zebras or an area of grassland.

Communities: Groups of interacting populations are called communities. An example of a community is all the populations of zebras, elephants, giraffes, grasses, shrubs, insects, and other populations of organisms that live together on an African grassland or savanna.

Ecosystems: An ecosystem includes all the interacting biotic (living) and abiotic (nonliving) components in a given environment. Ecosystems are generally divided into two groups: aquatic (water) and terrestrial (land). Examples are the Amazon tropical rain forest, the African savanna, the Sahara Desert, etc.

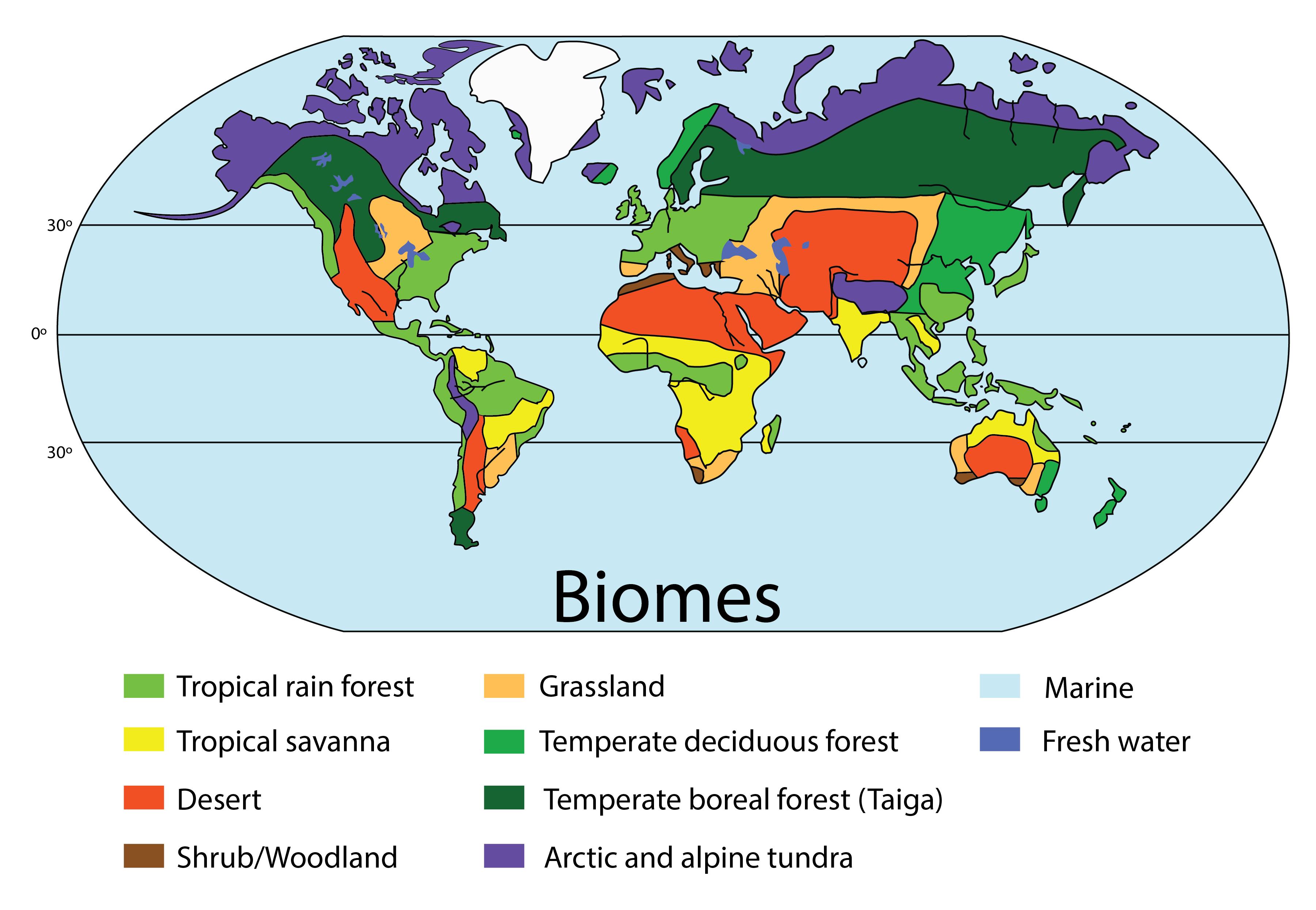

Biomes: Biomes refer to the larger biotic community across the planet. For example, the African savanna ecosystem is part of a large savanna biome of tropical grasslands found worldwide. Another example is the tropical rain forest biome that refers to an ecological community across the planet found in South America to Southeast Asia. However, the Amazon basin rain forest is a specific ecosystem within that biome. Look Out!

STEMscopedia

Below is a map of the major biomes of the world. Notice that many biomes are related to their location such as the northern arctic and alpine tundras or the midlatitude forests.

The living things in an ecosystem are interdependent. This means that living things depend on their interactions with each other and with nonliving things for survival. For example, a tree depends on sunlight for energy to make its own food. A snail depends on plants for food. A healthy ecosystem is one in which many different species are each able to meet their needs.

This bee is collecting pollen from a plant’s flower. It uses the pollen to make food for itself and other bees. The bee depends on the plant’s flower for food. What living and nonliving things do you think the plant depends on? Look Out!

Living things are also dependent on the right environment. The environment must meet the particular needs of the organism. Penguins and kingfishers both eat fish, but the penguin would not survive in the kingfisher’s tropical or temperate environment. Neither could the kingfisher survive in the penguin’s Antarctic environment.

What Do You Think?

STEMscopedia

Reflect

How do the nonliving components in an ecosystem support the other components?

Nonliving components are important parts of any ecosystem.

• Sunlight is one of the most important nonliving components. Light from the Sun helps plants produce food and oxygen.

Sunlight also provides heat that makes life on Earth possible. Without the Sun’s heat, Earth would be too cold for most living things to survive.

Take a deep breath. Every time you breathe, you take in air. Air is a mixture of gases, including nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide. These gases are nonliving components needed by almost all organisms on Earth.

• Water is another important nonliving component. All organisms depend on water. A healthy ecosystem is one that has enough water to support the variety of organisms that live there. What would happen if there was not enough water?

This plant uses nonliving components, such as sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide, to produce food (sugar) and oxygen.

• Temperature is a nonliving component that affects living things in an ecosystem. Think about what happens when the temperature drops in the winter.

Animals move to warmer areas or hibernate, trees lose their leaves and stop growing, and people begin to wear warmer clothing.

• Soil is another kind of nonliving component. In a desert, the soil is very sandy and has little moisture. It can support only certain plants that have adaptations to live with very little rainfall.

In a rain forest, the soil can be poor in nutrients but high in moisture. It supports large trees, long vines, and many other kinds of plants. These plants take up nutrients in the soil right away and often grow quickly.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

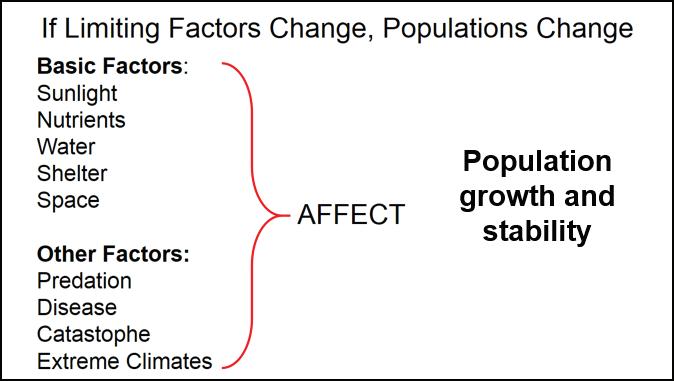

Changes in the physical environment can lead to population changes within an ecosystem. Environmental changes (natural or man-made) and limiting factors affect the health of an ecosystem. Examples of abiotic limiting factors include deforestation or seasonal changes. Examples of biotic limiting factors include disease or human activities.

Natural disasters, like floods, droughts, and fires, bring changes in resources that will cause some organisms or populations to perish or move while permitting other organisms or populations to thrive. The basic factors (sunlight, nutrients, water, shelter, space) and other factors (predators, disease, catastrophe, extreme climates) affect the health and growth of populations in an ecosystem.

What Do You Think?

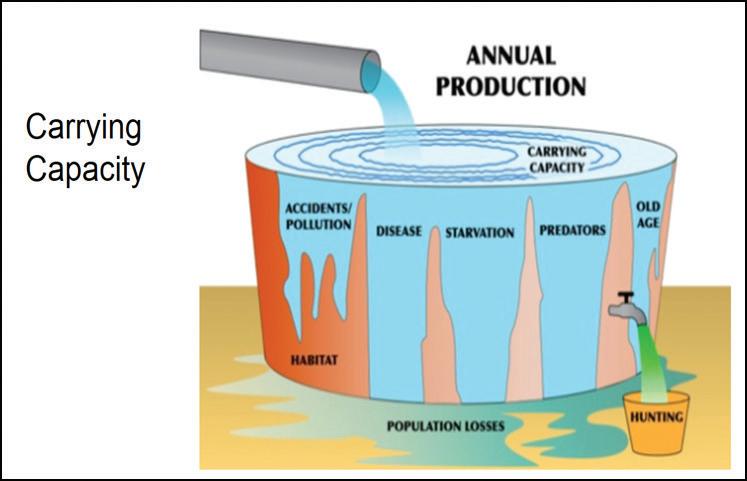

One measure of the impact of environmental changes from limiting factors or natural disasters is the carrying capacity of an ecosystem. The carrying capacity is the total number of living things that an ecosystem can support. An ecosystem can suffer a decrease in carrying capacity from major changes such as pollution, onset of disease, starvation, predators, hunting, or old age.

STEMscopedia

Reflect

Animals compete with each other for nonliving components, such as water. But animals are not the only organisms that compete for the resources around them! Plants also compete with each other and animals for nonliving parts of an ecosystem.

Suppose a fire destroys a forest. A short while later, new trees start to grow. At first, many young plants may grow in the forest. But some plants, such as trees, are able to absorb more water and nutrients, so they begin to grow taller.

As they grow, they block the sunlight to smaller plants growing below. The smaller plants cannot produce enough food to survive, and they die off. Forest ecosystems change because conditions in the forest are constantly changing.

How do the living components in an ecosystem support other components?

Think about some of the living components of a desert ecosystem. How do they interact with other things in the ecosystem? A desert has plants, such as grasses, bushes, and cacti. The grasses and bushes provide food to animals, such as deer and mice. Trees provide shade from the sunlight and shelter to other organisms. Birds help spread the seeds of a plant to new areas of the forest.

Burrowing creatures mix and move the soil, circulating nutrients back to the ecosystem. When organisms die, their bodies break down, become part of the soil, and provide nutrients to plants and other organisms. The living components of the desert depend on each other for survival.

A healthy ecosystem is one in which the population of each species is just the right size to support the other organisms that depend on it.

species: a group of organisms that are similar to one another and can combine to produce offspring

STEMscopedia

Look Out!

A single type of organism may play more than one part in an ecosystem. For example, you might think of a snake only as a predator. While a snake does eat other organisms, it may also be food for another predator. Certain birds, such as eagles or hawks, eat snakes for food. The snake is a predator and also a prey animal for other organisms.

Look Out!

What do you think would happen if a nonnative species were introduced into an ecosystem? The new species could actually damage the ecosystem!

The balance of an ecosystem can be greatly harmed by the introduction of a new species. In the 1700s, European rabbits arrived by ship in Australia as a food source. Those that escaped started a population explosion.

Since there were no natural predators of rabbits in Australia, there was no control of the population. Rabbits are herbivores, meaning they eat plants for energy. Millions of dollars of crops were destroyed by the abundance of rabbits.

New species of plants can also destroy the balance in ecosystems. An invasive vine from Japan was introduced to the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876.

It was sold as a shade plant and as a plant to prevent soil erosion. The climate and soil of the Southeast proved perfect for the unchecked spread of kudzu.

STEMscopedia

Connecting With Your Child

Ecosystems

To apply what your child has learned about ecosystems, take your child to a natural area nearby. It could be your backyard, a local park, a riverside, a city street, or any area where you might observe organisms in their natural environment. Work with your child to select an organism to observe. It could be an animal, such as a deer, squirrel, or fish. Keep in mind that smaller animals, such as insects, can be found in grass and under rocks. Insects often make fascinating subjects for observation. You may also choose to observe a type of plant or a fungus, such as a mushroom. Whatever you observe, be safe and do not touch or otherwise disturb the organism.

Write down the ways the organism is interacting with the living and nonliving components around it. For example, a beetle may be interacting with nonliving components by digging in the soil or drinking water. It may be interacting with living components by eating plants, or it may be prey for birds or other insects.

With your child, convert your list into a visual representation of these connections. Use a piece of poster board or butcher paper for your visual. Write the name of your organism at the center and draw a picture of it. Draw lines from the organism to all the living and nonliving components with which it interacts. Label each interaction on the line between the organism and the component. Feel free to draw lines between many different components.

For example, you may connect a beetle with a plant that it is eating, and then draw a line between the plant and the soil that the beetle is digging in. On the line between the plant and the soil, you can label that the plant obtains nutrients and water from the soil. The goal is to illustrate that the living and nonliving components in an ecosystem are highly interconnected.

Here are some questions to discuss with your child:

• How is your organism dependent on the living components in its environment?

• How is your organism dependent on the nonliving components in its environment?

• What components are needed by almost all organisms in the environment?