11 minute read

BAERBEL MUELLER

How would you define public space and what challenges would you identify in the design and use of public spaces?

Talking about public space is super interesting. And therefore I’m excited about the new Abstrakt Issue. I would say there are two definitions of public space: on the one hand, there is more like a twentieth-century definition, and then we have a twenty-first-century reality of public space. I would say the twentiethcentury definition for me is, or was, that public space is the space where basically every individual in society can freely move and be in an open space, mostly open space. But that might also be easily related to open space because I’m so used to public space in the nonWestern world. But what is crucial in the twentiethcentury definition I would say is that it is also a space which is free or can be free of consumption, where I as an individual can enter with little constraints and just be and stay and gather. And I think the twentyfirst-century definition needs to be very different, as we are not private and public individuals anymore in our private and public spaces. So I would say that the time-space relations we experience today are very different. We are never necessarily fully private and never fully public anymore. I can be in public space and have a very private encounter through my smartphone, let’s say, and I can basically stay in bed and be an influencer with an audience of millions via Instagram, for example. So I think this idea of public and private is very upside down and very different nowadays. And that obviously has repercussions on the use and design of public spaces.

Advertisement

Having spent a lot of time in Ghana and other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, how would you describe public spaces in Ghana and what are their biggest differences to cities in Western/Central Europe?

Actually, it was around 2005, 2007, that I did research on that topic together with Andrea Börner in Kumasi, looking at public spaces and market spaces in Ghana at that time. And it was very interesting to identify that. First of all, I would say that I don’t really use the definition or the notion of public space in this context. I would rather talk about open spaces because like I said before, with this twenty-first- century situation, we are never fully public or private. That led to the fact that I only talk about open space in the inner West African context.

So in a place like Vienna, for example, you have a public space or an open space, and there are certain given regulations. There are certain clearly defined zones where appropriation takes place or like where someone is putting up a kiosk, let’s say to sell drinks or if an event is happening, you need to reserve it and it’s very restrictive. But I would say in the West African context, it’s still more fluid. I mean, there are more regulations coming year after year, but there’s this fluidity of appropriating open space. I was amazed that it was possible that a lady would lay a towel down on the floor and put onions on top and that was basically considered a shop. And everyone would respect these two dimensions of borders of the towel. Or that someone would demarcate a kind of border with a line on the floor, and would position himself under a mango tree, putting up a chair and a table and being a barber or a hairdresser. So very little is needed to appropriate space. And there is also of course negotiation. Like, you cannot just put up whatever you want. So there are regulations, but these gestures then are really respected, even if they are tiny, and I think in a Western city, it needs more formal setups to be respected.

One of aFA’s latest projects, the New Guabuliga Market, is a perfect example of creating new public space for the local community to enhance commercial and social activities. Could you tell us more about the process, its intention and visions?

That’s a very interesting example because it’s somehow approved that architecture matters or buildings matter. So the genesis was that the authorities of Guabuliga, their local NGO, which aFA had already been working with for years, approached us and asked if we would be willing and available to design a market for Guabuliga. And the background was that there was no physical space. There was a location in the village which served as a marketplace and there would be like two or three women putting up tables and selling stuff, but they were exposed to the sun and they really suffered from that. And the result was that most traders in this small town or village would just put bowls on their heads and sell whatever they had to sell and move from house to house. And then there was this wish to have a proper marketplace. And it was clear that there were certain spatial requirements, such as the provision of shade and a sealed surface.

At first, I was quite sceptical that architecture would be the solution because it’s a matter of attitude and also a matter of economics. And that was really fascinating and wonderful to see that it really attracted traders, also traders from neighboring communities and even regional towns, to sell and to come to buy. I was really doubtful if behaviour and movement patterns would change that easily only because there was a physical structure. And the other thing I have to say is that there are very rigid designs of markets, all over Ghana, which are these very rectangular, equally shared places where, women and also male traders would have their portion of their square meter to sell, or sometimes even a physical, shop-like structure. And we decided differently, we felt that the roofscape was super necessary and urgent, and that it should be modular so that there was a potential for expansion.

The majority of developments in cities are shaped predominantly by private influence, while in your projects, you work closely with local communities. What do you believe to be the role of the architect in the negotiation between interests of different stakeholders in a project?

I mean, what I think is the beauty in our profession is that we are really trained to understand complex processes. And therefore we are really capable of understanding situations in a holistic manner. I think we are somehow capable of orchestrating complex processes on the one hand, but also the interests of different stakeholders. And yes, it’s true that there is a lot of communal involvement in at least the projects I do through aFA, but I also always insist that we come in as experts. So I’m quite critical, nevertheless, when it comes to participatory processes. I think that we bring a certain expertise and we need to address all stakeholders, but nevertheless, we’re the ones who orchestrate this process and then we also

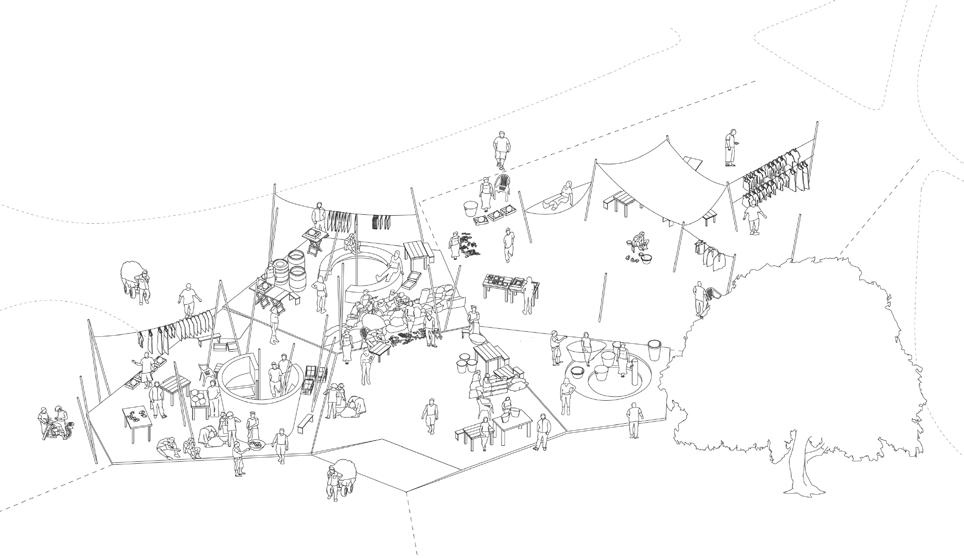

(1) New Guabuliga Market by [applied] Foreign Affairs

©Juergen Strohmayer

(2)

New Guabuliga Market, Axonometry, Market Day

©[a]FA

(3) New Guabuliga Market by [applied] Foreign Affairs

©Juergen Strohmayer need to translate that into our spatial findings and architectural manifestation.

What public space have you enjoyed the most and found the most engaging?

Oh, this is not an easy question because I also think that it’s always the question of who you consume or enjoy or spend time with in a certain place. There was a time when I was living in the second district in Vienna and I really enjoyed being at the Augarten. And also as an architect, I think the Augarten is one of these spaces where there is the potential to spend a lot of time in very different ways together without the need to consume or spend money. And it’s very inclusive. Like basically everyone can go there, be there, and you can do whatever you like. You can sit on a bench and read, you can meet your friends and play. So I think that’s a huge quality in an urban setting. Maybe it’s also now because the climate is changing. For example, if you are in New York, at one point you’re going to Central Park. And also in Vienna, if you have an apartment and you don’t have a balcony, you go to Augarten. So, I think that’s also something which is becoming more and more interesting to people, being in green space, and the Augarten is one of these.

What else comes to my mind obviously is the Plaza del Campo in Sienna, which on the one hand is a touristic place, but I think it’s one of these examples where you approach a public space and you really have this wow effect because it’s so beautiful in its design and it is also very engaging like that. It is somehow boarded and there are opportunities to consume, but then there is also this dome. And then there is also the possibility to just sit on the floor and be, while also consuming privately or enjoying gatherings in the atmosphere. And the other space I have in mind is in Marrakesh, the Djemaa el Fna, which is again very touristy, but where you can consume food, and then you have musicians and people setting themselves up to entertain. So these are somehow very touristic, classic, examples, but I think they function quite well. And besides that, of course, as an architect, I’m always impressed by huge open spaces. For example, there is the Independent Square in Accra, where you have a huge sealed surface and it’s again, boarded by seatings. There is basically nothing going on there, but there is also a certain attraction of bigness, of big open spaces, to me as an architect.

What would be the most important message that you would like to teach the next generation of architects?

I really think we should be aware that we are really, through our education, capable of understanding complex processes, and therefore we are capable of orchestrating complex tasks. And then talking about the next generation of architects… That’s also the reason why I really love teaching at I oA and therefore I also strongly believe in the education of I oA that, as architects, it is about creating a surplus. I don’t define architecture as building only — investors and individuals are capable of building — but there always needs to be a surplus if we come in as architects. And the other thing is that what is beautiful about our profession is that we are capable of working on all scales. We can detail a piece of furniture or a door but we can also really think about the infrastructure, the beauty and the spatial manifestations of a whole city. Of course, we always need to involve partners from related professions, but nevertheless, we have the whole spectrum of scales and that makes us predestined to contribute to the becoming of public spaces.

One more comment: interview from January 6, 2022 conducted by Andriana Boeck, Velina Iantcheva, Viktoria Tudzharova

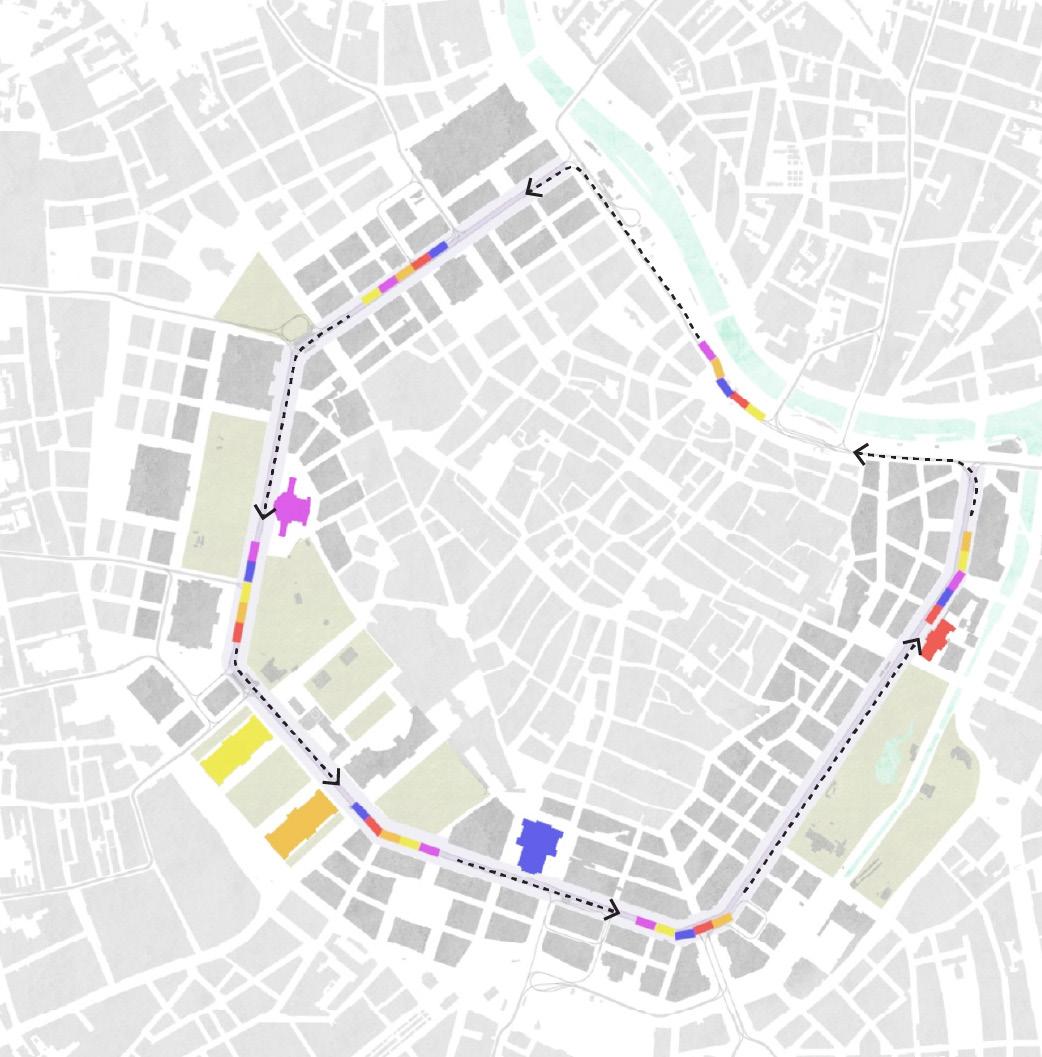

Talking about this term at I oA or this semester or academic year, I think it’s very exciting. And when we talk about public space, basically all three studios are engaged in very different ways. Studio Lynn is looking at the Ringstrasse (Vienna) and thinking about what this street could become if it were free of cars. And then in Studio Hani_Rashid, they are looking at extreme climatic challenges and coming up with large-scale proposals to solve these. And there are a lot of questions about how public spaces look in their respective self-chosen locations and also design proposals. And then Studio Díazmoreno Garcíagrinda is looking at London and how to engage with marginalized or difficult parts of the city and open spaces and green spaces. And so I think your Abstrakt topic is coming at the right time.

“I think [architects] are somehow capable of orchestrating complex processes on the one hand, but also the interests of different stakeholders. [...] I’m quite critical, nevertheless, when it comes to participatory processes. I think that we bring a certain expertise and we need to address all stakeholders, but we’re the ones who orchestrate this process, and then we also need to translate that into our spatial findings and architectural manifestation.”

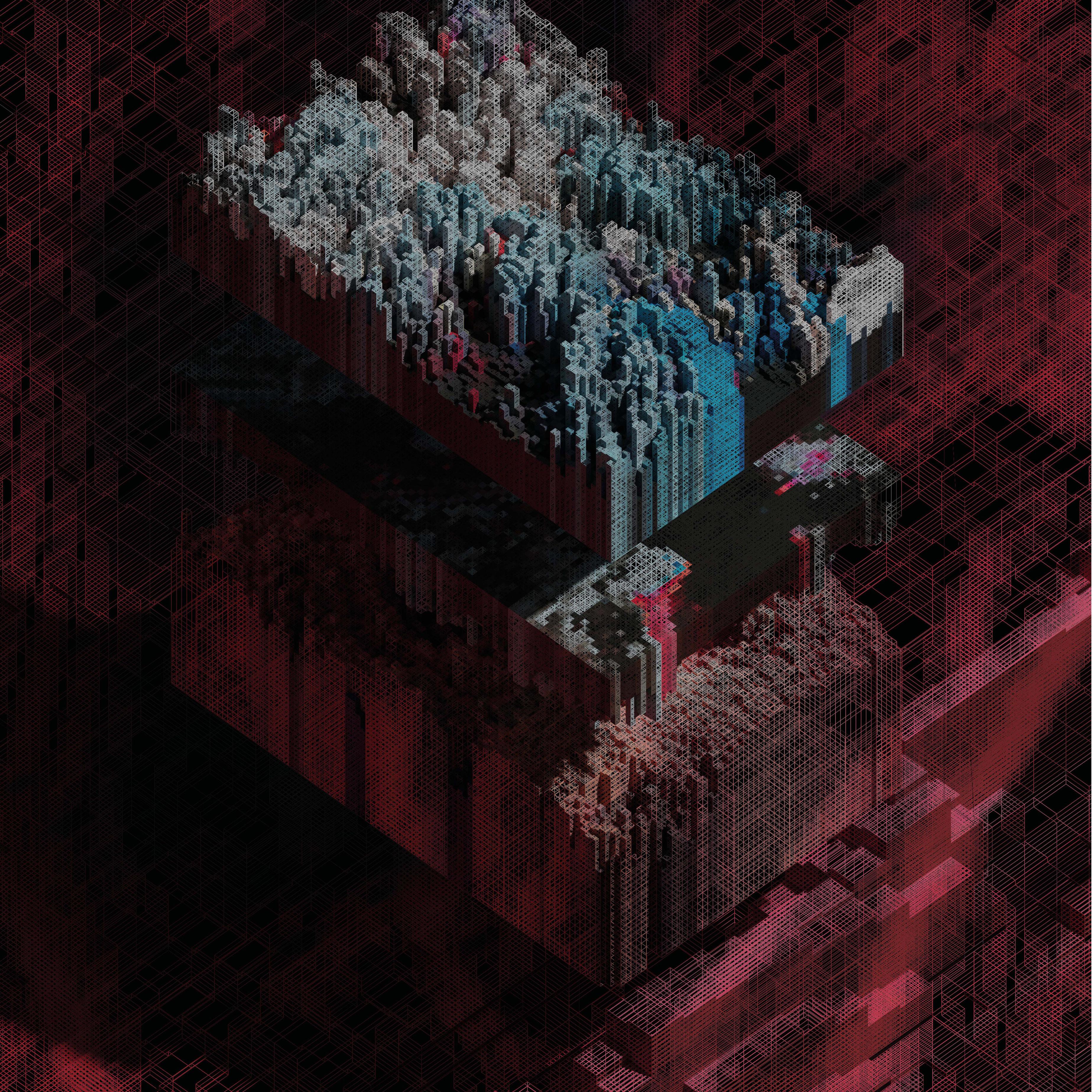

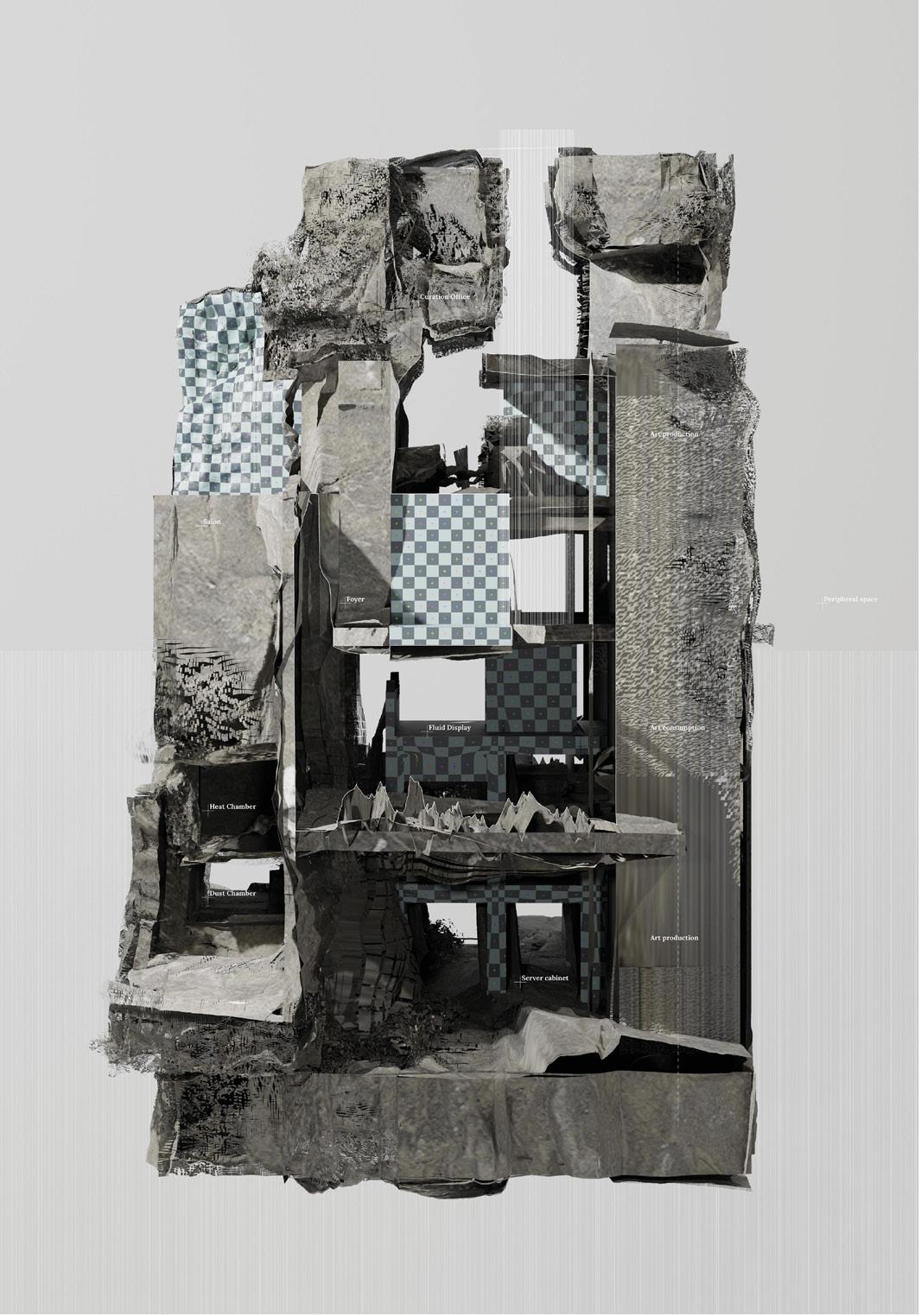

Project by Iga Mazur

Hot Fat DirtyProduction Display in Residence

The digital market of NFTs, rather than keeping the promise of a great disrupted future of new financialization, gives a cute little piece of the action from global capitalism to the artists, reproducing the traditional art market performed on the grounds of museums and art galleries. The project speculates about the radical cooperative residency for artistic production, its display, domesticity and storage in the City of London. It is focused on digital artists and art practices, rather than only exhibiting the end products of their work. The speculation about the ownership of objects or tokens and the private/public relationship of land and property lays the ground for creating a public space for collectors and digital audiences. The dirty matter accumulates heat to create apparently fat structures that act as thermal devices. The dirty construction builds up the space for the mess.

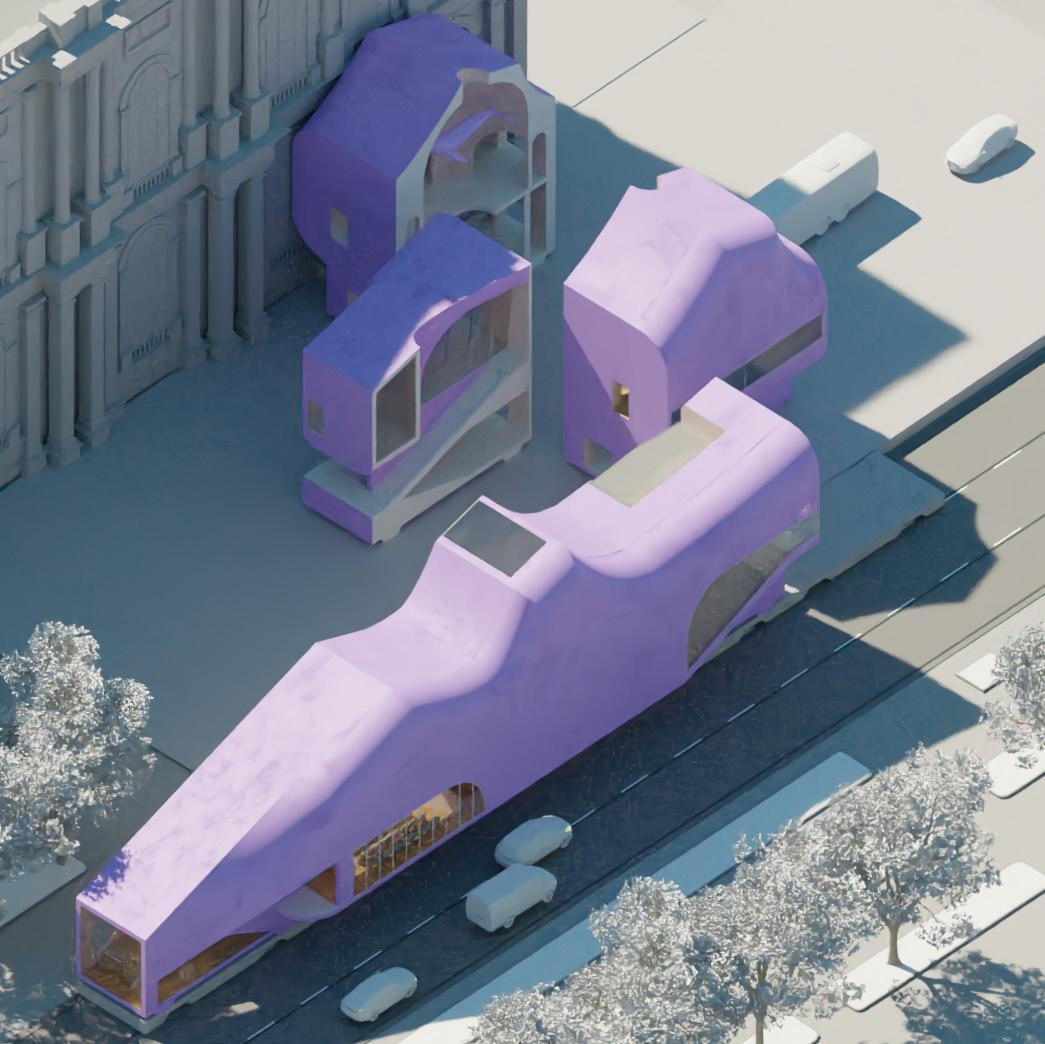

Ar[T]ram

Our proposal reimagines the traditional museum and extends the museum experience outdoors in a motional and dynamic way. It links the cultural facilities and provides a preview highlighting a bigger exhibition at a permanent museum. It combines mobility and pedestrianization. We treat the Ring as a running sushi table, where self-driving modular galleries and complementary museum programs travel along the street on the existing tram tracks. By adding to the existing transportation system, we get the opportunity to engage people with art while they are moving through the city, without signing up, for having a museum experience.

The Ar[T]ram turns the vehicle into a public space that offers an unconventional experience to its visitors. The ambition is to transform the Ringstrasse into a cultural and artistic hub that is constantly moving and inviting the public to gather and interact.

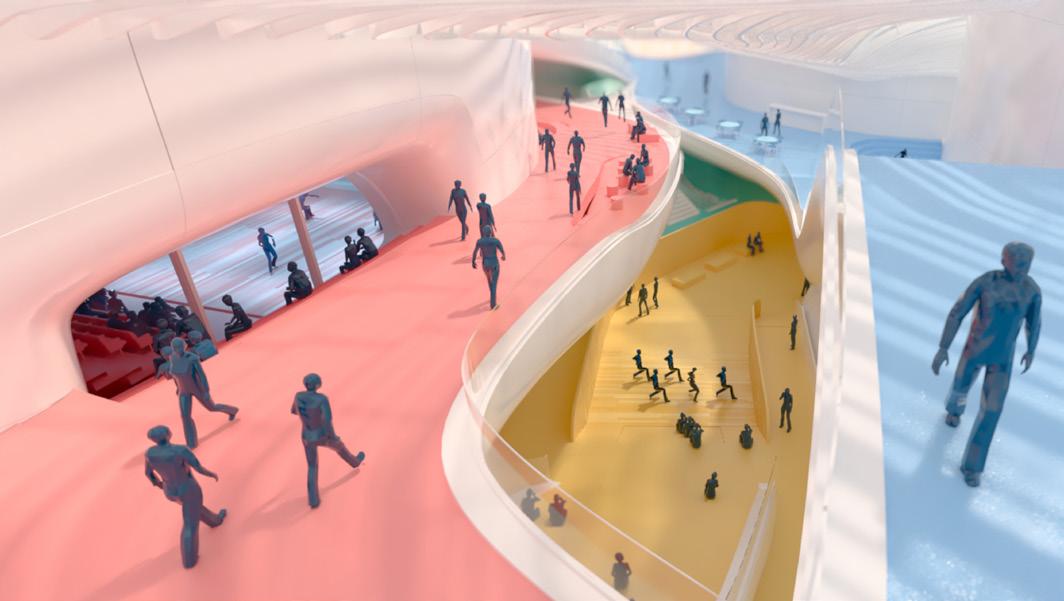

MoMAS Modern Museum of Audible Space

Modern Museum of Audible Space is a network of installations, art galleries, and spaces for artists to create – proposed as an expansion of the public space around New York’s shoreline. Using sound as the connective tissue of this network, it embodies the ambition of creating a form of languageless communication between the different components that compose the art world. Therefore, the project not only accommodates sound-related installations, it is also itself an instrument capable of producing and manipulating sound. Formally, the design is based upon sound visualization methods derived from the research of physicist and musician Ernst Chladni. With cohabitating spaces for artists, New York is kept available to a diverse population. The spaces open for social interactions, encouraging discourse and cross-disciplinary collaborations. The adaptable galleries are constantly reforming and transforming the adjoining public areas, while the areas for ‘creation and research’ are envisioned as a place where radical and critical thought can be incubated.

Culture has become the common language. It is an interconnected collection of spaces created to support, display and integrate art and artists into the fast-paced – and quite challenging – life of the dense city of New York.

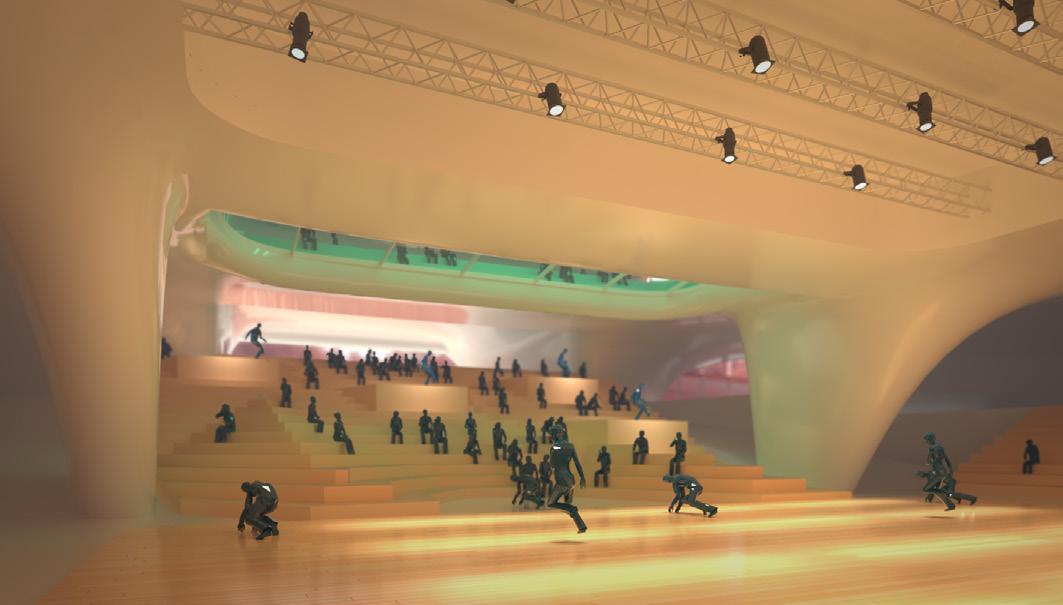

Dancing in the Street

This project aims to democratize access to both the limelight and the viewing seat by treating the facades as interfaces between theaters and a wider audience and by defining spaces for performance as an extension of the public realm.

Located in Helsinki, Finland, the proposal caters not only to summer activities, but aims to extend the calendar of street performances and informal social dances to the cold winter months by programming the circulation of the building with sequences of plazas, stages and cafes.

The visual relationships within the interior street network challenge the dichotomy of active actor versus passive spectator. The role of an individual is ambiguous — each visitor both observes and is observed, or rather becomes a participant in a collective performance.