13 minute read

CLARE LYSTER

We are really interested in your latest work, the book, Learning from Logistics, and we wanted to know from you, why logistics? Why do you think it’s so important to bring the logistics discourse specifically back to the attention of designers and architects?

Well, the book isn’t really that new. It was published in 2016, but it is having another moment because there’s so much talk about logistics now. For example, during Covid, we were shuttled into this virtual world by relying more on streaming media and e-commerce much quicker than we would have otherwise. So the book has a new relevance. But even 10 years ago (in fact, ever since the 1970s), if you looked around the world, it was hard not to notice that infrastructure and mobility systems were suddenly becoming more important to city-building than architecture. Everything was moving.

Advertisement

Architectural form used to be the way that we would think about making the city, and then it began to become apparent that, if you look around at information flows, material flows, people flows, architecture, which is traditionally the study of the object or the figure, was becoming unable to deal with all these new mobility systems in the city. And so that’s really why I wrote the book, to explore and to question how, as designers, can we move from thinking about the city from figure to flow? And if we start to do that, then what changes? There are a couple of images that I use comparatively, to clearly articulate this idea. One is the traditional figure-ground image of the city that all of us learn to draw. From the get-go, we think of the city from the perspective of the figure-ground drawing: black figures on a white background. But there’s a very famous drawing by Louis Kahn produced in the late 1950s for a project in Philadelphia where he starts to draw the downtown area through traffic flow systems. He is using notational systems like dots and dash lines and arrows rather than pochéd figures. Yet this drawing is an equally valid image of the city, one that completely dematerializes the building fabric of the city in favor of flow.

That image was a precedent for the book. How do we take that project of representation and how do we draw the city in this kind of moment of flow?

While the book analyzes many emerging logistical platforms, Amazon, Fed Ex, Ryanair, etc., which became the lens through which I wrote the book, but from a disciplinary perspective, it deals with the representation and design of the built environment in an era where flows dominate.

So that’s the idea behind the book. How do we, as architects, move away from solely building figures to integrating architecture with systems of flow into the design of the city?

“How do we, as architects, move away from solely building figures to integrating architecture with systems of flow into the design of the city?”

In your book, you also talk a lot about this comparison of these traditional infrastructures, as we’ve seen in the nineteenth century, to these new virtual or digital infrastructures that we now see in the twenty-first century. How are these virtual infrastructures affecting our build environment today in comparison to before?

The book looks at a very particular set of flows, what we now call logistical platforms. As I mentioned above, it looks at Amazon, FedEx, and Ryanair, which are the anchor platforms, and I look at these from the perspective of five different themes: planning the city, siting the city, time, architecture and landscape, and circulation. Each chapter tries to make a comparison between older or even existing circulation systems with these new platforms, so taking lessons from previous logistical systems in cities. It’s not as if this is a new way to think about the city. There has always been logistics in some shape or form historically.

For example, the second chapter looks at the industrial city, which was geographically determined. If you look at all the great cities of the industrial era, like Manchester in the UK, or even in France, cities that emerged from the first wave of industrialization, they all developed in areas next to natural resources — coal mines, or streams, and rivers in the case of the mill towns in the UK. They were all tied to some sort of natural or extractive resource. But now if you start to look at how logistical systems operate, place has less meaning. The city is less tied to geographic criteria and emerges instead out of a network condition. Ryanair exemplifies this. Post-‘89, it leveraged the political situation of the opening up of Europe, and started to fly to areas in the Eastern Bloc. This, combined with landing in airports outside of the main tour circuits as a way to save money, opened up a new map of Europe. So rather than fly to Paris, you went to Beauvais instead. Since its landing slots are always in smaller airports on the periphery of a big city, the Ryanair network became a catalyst for the popularization of second- and third-tier cities. For example, Charleroi, a postindustrial town in Belgium, suddenly became a headquarters for Ryanair and development comes with that. So, it seemed to me then that the network was now the agent for urbanization in the way geography or resources were the agents of urbanization in the industrial city. Maybe my favorite chapter in the book, or at least one of the more successful ones, starts to look at the infrastructural systems and the attendant spaces of logistics. It focuses on Amazon. I’m interested in these platforms as proto-infrastructural landscapes, given that the warehouses (fulfillment centers), which are vast big boxes measured in acres, are calibrating space with measurement systems, more akin to landscape than architecture. Moreover, Amazon is evidence of a hybrid assemblage – a mixture of online with the physical and the digital. Just look at all the gadgets and apps that we use as an interface between ourselves and the company. Finally, I’m looking at how these fulfillment centers are located on the outskirts of cities, although that’s changed a lot since I wrote the book, because now it’s moving the fulfillment centers closer and closer to urban areas so that it can enact same-day delivery in dense urban areas. The format of the fulfillment center is changing.

Considering our experience of cities and more particularly, shared urban spaces, do you believe that they are the consequences of these shifts? How would you define public space at all and how do you think this definition has actually changed over the last few years?

That’s a tricky question. I mean, on the one hand, logistics have not changed the city as much as I might’ve thought they would. Other than what I mentioned above about the exurbs, the downtown city that we live in is still very much the nineteenth-century industrial city, at least the Western city. Chicago looks the same as it did pretty much 150 years ago. I’m not sure about Vienna. It’s interesting, these new systems are infiltrating the city, but sometimes they’re hard to find and they don’t register very strongly. Maybe in the retail environment, not to say that retail is the only kind of public space, but as we do more online shopping, I do think the city is emptying out. Like in Chicago, we have a lot of vacant real estate on our main city streets, the city streets that everyone would go to, where in previous eras, you would dress up to go out on a weekend, and it was an urban event. The demise of retail was even happening before Covid. So, there’s a certain emptying out of the city that I think is impacting public space.

In the American city in the 1980s, when we started to revitalize the downtowns, retail was presented as a savior of the city. If you were doing an urban development, you had to have ground-floor retail because that would activate the street. I think our streetscapes are suffering because of online commerce and in some areas, there is not the same busy atmosphere on the streetscape. And that’s a little sad. So I think that’s the biggest impact on public space so far. But then again, I’m always looking for new ways to think about public space. The sharing economy made possible by logistics will start to

(1) CLUAA - “Winterwaterway”, Isometric Drawing, 2018

A modular pontoon system, assembled in the canal waterway, proposes an adaptive reuse of selected stretches of the Erie Canal in wintertime, now that commercial navigation of the canal is over. The Erie Canal, a 363-mile inland waterway completed in 1825, connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Great Lakes and was responsible for the urbanization of many of North America’s largest cities.

become even more legible in the public realm –logistics matches people up as well as things and events and in so doing, other things happen, maybe very different things, and public events that piggyback as a result. In this way, logistics can leverage the atomization of contemporary culture by curating microspaces that respond to niche collectives.

Taking into account the current developments of digitalization, information technology, and the globalized networks that you are talking about, where do you see the biggest challenges for architects and urban planners in the production of urban space?

The problem with these systems is that they homogenize space. Amazon looks the same, no matter where it is. These logistical platforms operate on universal rules. Yet the design of the built environment needs to amplify the specificity of place. We still need to have atmosphere and experiences and spaces be different, no matter if you’re in Vienna or Chicago. And so for me, the challenge is how to resolve the kind of universal claims of these logistical platforms with the specificity of a place.

I was involved in the Irish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale last year with a group called Annex. We were looking at data infrastructure systems, which is really the backstage of logistics because, without information networks and data centers to store the information, none of these contemporary platforms can work. We were looking at how Ireland has emerged as a sort of data hub in Europe. There are many reasons for this, and I’ll just highlight one reason here. The high-speed transatlantic cables coming from the US to mainland Europe and beyond come aground here to link up to other terrestrial networks, given Ireland’s location at the western edge of Europe. And so a Google cable, that’s sending your Instagram pictures in nanoseconds, is coming aground in these really rural coastal villages where 500 people live. And so that’s an example of the overlay of this global universal system on this super tiny, specific rural space.

One job of the architect is to reveal these very strange contradictions. People go on these logistical platforms and have absolutely no clue about what goes into shipping a book that you order on Amazon to your door and all the spaces and locations that are involved in that flow. This might not be the realistic answer you’re looking for, but I think part of our job is exposing or unveiling these contradictions between technology and place and representing these graphically so we can grasp the implications and opportunities.

Outside Dublin (Ireland’s capital city), we have multiple data centers, as many as 60-100 of them, including large hyperscale facilities for Microsoft and Google, and Amazon is currently building a gigantic data campus. There’s a ton of design in these spaces, but it’s not designed in the way that you and I think of design. The design is in the equipment and the interior and the security systems and in berms around the edge that hide the facility. But these big warehouses and data centers are located in suburban areas. There are schools and houses on the next lot and there’s no integration of those systems into that neighborhood. So, I think another area where planners and architects can get involved is to synthesize across the material manifestations of these systems in a much more holistic as well as an aesthetic way.

At the moment in Vienna, there is a trend to mix different functions and programs together. So in one block there might be housing, mixed with industry, retail, infrastructure and so on. Do you think that mixing these different functions could be a way to avoid homogenizing and separation and to liven up public space?

I do. And that’s great that you can look at some examples in Vienna. I mean, the ethos of the modern city was separation. You have industry here, you live there, you’ve institution here, you’ve civic there. That was the model for the modern city. But we’re now seeing that maybe that wasn’t such a good idea. And so now we’re rethinking the city in terms of zoning and mixing occupations or functions that used to be separated. And I think that’s because now, the industry is different than it used to be. Obviously, you can’t live next to a plant where there’s toxic smoke coming out, but mostly industry is cleaner now, allowing adjacencies that were not possible previously, that allow for new mixes in a healthy way that we couldn’t have before.

Furthermore, there is a kind of cultural awareness now that favors mixing things. And that’s very promising. This is emerging out of the crisis that we’re finding ourselves in and the necessity to think about hybridizing, not just spatially, but in terms of energy systems and resources. How can we invent synergies between programs from the perspective of energy savings or energy demand? The public is also becoming more curious about where things come from suddenly. If you look at agricultural systems for

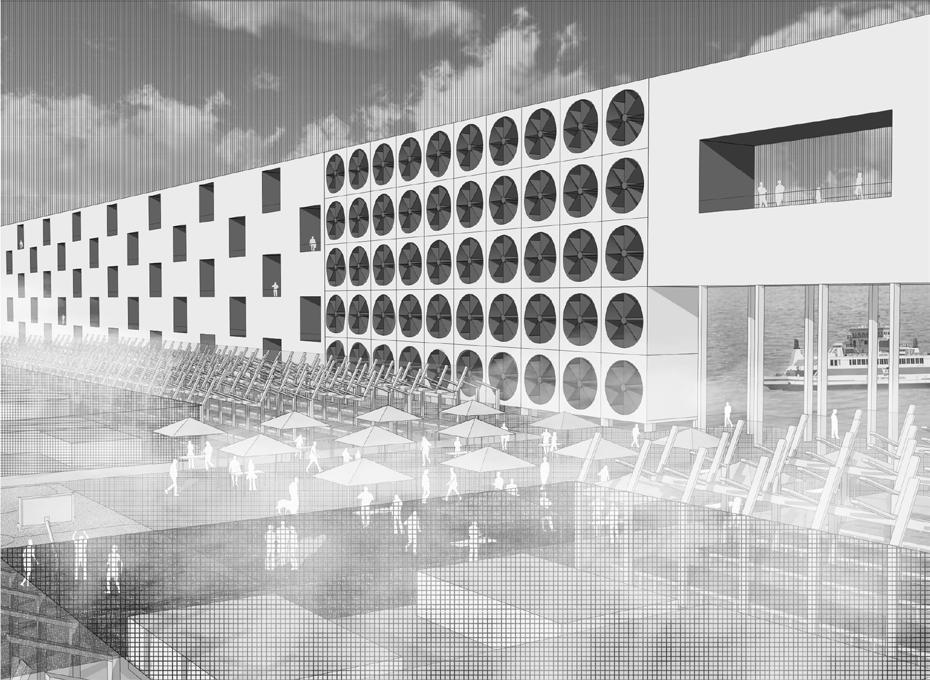

(2)

“Synergistic States,” Pier, Isometric, 2021. Speculative design proposal for a data farm with housing and greenhouse farming on the coast in Dublin, Ireland.

(3)

Entanglement, Irish Pavilion, 17th Venice Architecture Biennale, 2021. The pavilion curated by ANNEX explores the materiality of data infrastructure with a focus on the data industry in Ireland both historically and in the present day.

©Alan

Butler example, the industrialized food economy separates production and consumption. Up until maybe five to ten years ago, people were not bothered about where their food came from. Now there’s a cultural shift occuring to understand where things come from and wanting to trace metabolic flows from source to plate. So all these shifts are enabling new mixes, which will, in turn, generate new types of public space moving forward.

During the pandemic, we have seen a sharp increase in the popularity of digital alternatives for social exchange on digital platforms, as well as the purchase of goods and services which, as mentioned earlier, reduces physical encounters. Do you see this as a threat to physical space, or as a design potential — considering hybrid modes that we are recently seeing more and more of?

Yes, to hybrid modes and a mixture of both online and physical. During Covid, we were all online, on Zoom, watching movies, etc., but then people really wanted to get out into nature. If you look at the statistics for regional parks outside major cities, visitor attendance

“Hand in hand with the super technologization of space, there is also a return to a primitive notion about being in the world and looking at architecture at a far more fundamental and elemental level.” to natural areas completely peaked during Covid. Obviously, this was a result of lockdown and needing to social distance but the hyperdigital lifestyle somehow prompted a longing for more fundamental territories. I think this is something that’s going to stay. So I’m really excited to think about new forms of nature (constructed and real) in cities, as well as on the periphery of urban areas, and thinking about integrating nature into the everyday in a new way. The emphasis on greening old infrastructure and opening it up for public use (The High Line effect) is one example. The fusion of high-tech (virtual) with more ritualistic practices is also palpable. I usually have my students look at the film Blade Runner 2049. And there’s a very nice interview between Liam Young and Paul Inglis (in Machine Landscapes: Architectures of the Post Anthropocene [Architectural Design], edited by Liam), who was the urban designer for the film. And if you look at the scenes in the movie, they’re super high-tech in some places, but then super primitive in others. Hand in hand with the super technologization of space, there is also a return to a primitive notion about being in the world and looking at architecture at a far more fundamental and elemental level. This is a central theme in the Irish Pavilion called Entanglement at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021. And so that movie is interesting in that way. Taken together, a reclaiming of nature and a reclaiming of the primitive suggests a need to find something much more fundamental and elemental as an antidote to the digital or in tandem with it. There’s a lot of opportunity for rethinking cities from that perspective. interview from April 4, 2022 conducted by Adriana Boeck, Velina Iantcheva, Moritz Kuehn

I believe the combination of the digital with natural ecosystems will provide many opportunities for public space, moving forward.

I don’t think the digital is a threat to public space or physical space, but it’s part of our lifestyle and it’s part of the spaces we inhabit moving forward. I’m an optimist, I mean I’m a technological optimist. I think it’s exciting that we can start to devise new hybrids, technologies and physical space.

What has been or what is for you, your favorite public space or urban situation?

I like busy airports – not that I have been in one for two and a half years. I like that there’s public space and commercial space and lots of activity around an infrastructure node. So not necessarily a particular city, but I think the airport is an interesting urban moment. The flow and the operation of the place is very legible in the space. And so, it’s kind of nice.

“The sharing economy made possible by logistics will start to become even more legible in the public realm – logistics matches people up as well as things and events [...]. In this way, logistics can leverage the atomization of contemporary culture by curating microspaces that respond to niche collectives.”

Baerbel Mueller is an architect and researcher based in Austria and Ghana. She is associate professor and dean of the Institute of Architecture at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. She is also head of the [applied] Foreign Affairs lab, which investigates spatial, environmental and cultural phenomena in rural and urban Sub‐Saharan Africa and the Middle‐East. She is founder of nav_s baerbel mueller [navigations in the field of architecture and urban research within diverse cultural contexts], which has focused on projects located on the African continent since 2002.