11 minute read

SIQI ZHU

How would you define public space at present and what challenges can you identify in the design and use of public spaces?

I guess there are a couple of ways of talking about this one. In one sense, the definition of public space hasn’t really changed all that much in the era of visualization. We have parks, plazas, streets and things that we’ve traditionally considered part of the sort of public realm and civic infrastructure of the welfare state. We have maybe a permutation of that that are sort of privately owned, privately operated public spaces that are accessible by the public and yet remain under private control. We have things like privately owned public spaces called ‘POPs’ in New York City, these are part of a program whereby private development provides open spaces and public spaces in exchange for greater development permission. They can be atriums and even sort of plazas on public spaces. So this might be a slightly newer permutation of the notion of public space. There are spheres that are not personally private, but where public life sort of happens in them.

Advertisement

And you know, one could always make the argument that digital platforms — Twitter, Facebook and others — all constitute a sort of a public sphere in the digital world, where though, you know, there are obviously degrees of publicness when you talk about all of these spaces.

I think there are very particular challenges related to today, this moment that we’re in, right now, having to do, for example, with climate change and the fact that many cities will become less inhabitable because of climate change and the role of public spaces in these places wanting to evolve, to accommodate that reality.

Over the last 20 to 30 years, the idea of fiscal austerity has really degraded the quality of parks and other kinds of public infrastructure in our cities. So I would say a common challenge over the last 20, 30, 40 years is the challenge of upkeep and funding and maintenance and how to do those things to a certain level of standard while at the same time, contending with diminishing resources for those things. There are fundamental values of good public spaces that involve inclusion and accessibility and a vibrancy. I think an ongoing question is how to accommodate different kinds of bodies. People don’t come in normal shapes and sizes, right? People’s bodies and abilities and their cultural contexts around public spaces are increasingly different. I think how to recognize that diversity and design for those things has become really interesting. A particular question I have is, What does a truly multigenerational public space look like?

”I think an ongoing question is how to accommodate different kinds of bodies. People don’t come in normal shapes and sizes, right? People’s bodies and abilities and their cultural contexts around public spaces are increasingly different. I think how to recognize that diversity and design for those things has become really interesting. A particular question I have is, What does a truly multigenerational public space look like?”

I don’t know if you guys know this phenomenon in China, in public spaces, in the evenings, a lot of elderly women come together and gather to do dances, dance classes and plazas, and they blare music. And that’s been a huge source of conflict between these people, these elderly women, and everybody else who uses the park. So that’s just a good illustration to me that we haven’t really figured out how to design spaces for multigenerational occupancy.

To what extent is context specificity important in the creation of successful public spaces, compared to generic or prototypical approaches to urban activation?

I do think context provides kind of, not just constraints, but really creative drivers for design projects, right? One thing that could be interesting is thinking about the notion of value. What is valuable to people? Because in urban regeneration projects, the narrative is always, you know, we take a derelict piece of land and we redevelop it into a high-value, highly active, highly usable public space and adjacent development. But, that’s sort of discounting the value of the space as it is today and the way that some people might already know it.

I mean, you can think of so many examples where you know, maybe it was, a skate park, you know, for skaters or for like illegal raves, for example. And then over time that space becomes normalized and regularized as a civic public space and a lot of sort of what the nice quality of these spaces was actually got lost in the process.

How do you envisage digital technologies being applied in the process of shaping public spaces?

Several different ways — develop a taxonomy for the use of technology in public space. I think in the front end, it’s a tool for analysis, for information gathering, and a tool for a collaborative sort of collaborative visioning. The technology of monitoring and analysis, that’s also another, different family of technologies. Sensors that monitor usage, that monitor, for example, the buildup of trash, the coming and going of people and vehicles where there might be conflict between these two modes.

And then there is also a class of technology that is sort of making the physical aspects of a physical environment into tangible computing interfaces. They’re basically sort of making inanimate physical objects interactive and physically actuated. There are like connected streetlights, for example, that you can control via the network. There’s even, you know, a very recent central example: Central Park in New York has been doing these ‘sound walks’ that are location-based sound media works. You basically take your phone, for which an artist was asked to create different soundscapes. And various parts of the park get activated when you’re with your phone, traveling to that area. So this idea that technology can provide an additional a sort of sensorial overlay to the park is interesting.

What’s interesting to me as a future direction for exploration: How do we use technology to create larger spatio-temporal communities around a single public space? What I mean by that is, you have this experience of going to a public space and you are alone there by yourself. And there are other people, but you realize that you and all the other people there at the moment, and all the people that were there before and will be after you, are really part of a larger collectivity.

So how do you think that data analysis could improve physical public space?

I can only think of a really concrete example. One sensor technology I’ve worked with extensively is called Numina. It was developed here in Brooklyn, and it basically uses anonymized computer vision to detect and count people in vehicles. And one of the analyses that you can do with it is understanding conflict areas where people and vehicles tend to come into conflict, creating danger. So I think that’s just one tangible example where data analysis can be used to identify gaps, shortcomings in safety and accessibility. I think that’s a very tangible and a fairly realistic use case for technology in this case.

In your lecture you gave to Studio Lynn last semester, “Streets Ahead”, you discussed the possibility of turning the street surface into a technology platform by creating a spatial and temporal zoning for multiple constituents such as technologies, private ventures that operate on the curbside, their clients, and the remaining inhabitants of the city. How do you think each of those stakeholders would benefit from such an organization?

They have a need for a space that can benefit from being on the curbside and a sort of sharing platform for space on the street would allow everyone to have access to that space — pretty self-evident as a good thing.

Now, I think that the risk here is, How do you fairly sort of adjudicate between competing uses on the street right there? People are always in competition for the same space. How do you make that allocation fair? I think that’s an interesting question. I don’t know if there’s like an across-the-board answer for that, I think maybe the best thing I can say is, people need to recognize that that decision of how to allocate time and space in public spaces generally is a highly value-laden decision, right? I think there was always a tension between regulation and flexibility. I don’t think that there can be one without the other. The sort of minimum threshold for safety and accessibility needs to be respected.

We were very curious about the Charlestown Navy visitor experience plan. In this project, you took up the role of a mediator between multiple stakeholders, including the local community, employing a mix of hands-on and computational methods. Can you describe the reasons for choosing those methods and the outcome, and how do you integrate the community’s opinion into the planning process?

It was the city of Boston. It was a museum. It was also the US Navy. And besides that, it was the members of the public. So it was really, really a lot of different people. So the challenge was how to get

“People are not always available at the same time. Digital technology plays a role of creating a sort of virtual forum for people to meet across space and time. And that is why we use digital methods in addition to the analog and physical ones. You de facto create exclusion of certain people that maybe for various reasons can’t come to these physical conversations.” everybody together in the same physical space and time to be able to talk together at the same time. People are not always available at the same time. Digital technology plays a role of creating a sort of virtual forum for people to meet across space and time. And that is why we use digital methods in addition to the analog and physical ones. You de facto create exclusion of certain people that maybe for various reasons can’t come to these physical conversations. So you need a bit of both to really ensure that you have a fair and representative cross section of insights and people’s opinions.

I think we have some very practical, on-the-ground, early evidence for what that digitization is doing to physical environments, whether you’re talking about what’s happening with Amazon deliveries or what that is doing to urban streets and sidewalks — the virtualization of retail and what that is doing to urban retail spaces. I think there is some early evidence that the impact has been quite negative, in the short run anyway. And then, you know, this might be partly a function of the fact that we just haven’t really had a lot of time to let these effects play out. But I think the idea of using the digital to augment the physical has not been fully explored yet. I think one of the interesting things to me is always this notion of spaces that are rendered obsolete by digitized retail. I think there are some really easy examples, those large suburban shopping centers, suburban malls in the U S. So many of them are being redeveloped into housing and new mixed-use communities, that’s already happening. US-based developers who are redeveloping suburban malls, all they’re trying to do is to make it look more urban, make it look happier, build some of the textures of the normal city back into the suburban, vast sort of a mall by creating public spaces and plazas and even streets in some cases, pedestrianized streets.

How do you see the role of architects and urban planners evolving in the future in the negotiation between different stakeholders?

I think architecture always has its job of how to communicate a function to it, right? This idea that you are the conduit through which other people speak their desires and visualize their desires. And I think that remains true. I think where things might change a little bit is at least for some architects, this idea of using architecture as advocacy, to give voices to communities that have been up to this point, less represented. I hope that’s going to be more of the sort of practice that people incubate with their architecture. I also think there is increasing digital proficiency, and proficiency of architects to not just leverage, but also in some cases, design and implement digital technologies in physical space.

“What’s interesting to me as a future direction for exploration: How do we use technology to create larger spatio-temporal communities around a single public space? [...] You have this experience of going to a public space and you are alone there by yourself. And there are other people, but you realize that you and all the other people there at the moment, and all the people that were there before and after you, are really part of a larger collectivity.”

Siqi Zhu

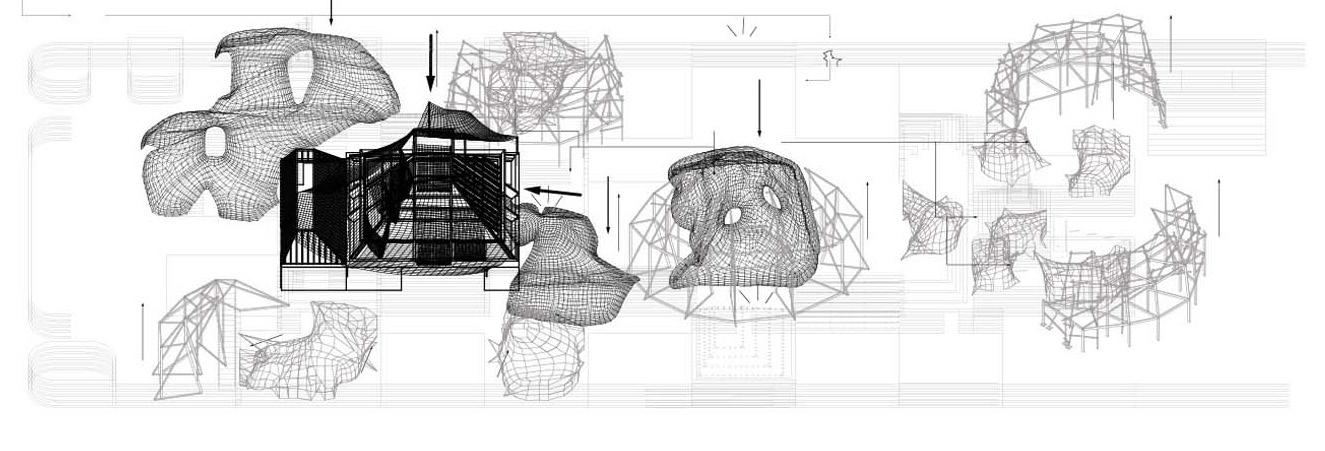

Garden of Posthuman Abundance

The project deals with the question of how hyperfunctional landscapes can be transformed into the pleasure gardens of the twenty-first century. The excessive and interesting character of the site (car park) is directly related to the historic type of garden that emerged in London in the eighteenth century: the Vauxhall Pleasure Garden. The project tries to curate the notion of escapism and strangeness that the site already has. What makes car parks especially interesting for this project is that most social norms don’t apply to them due to their purely functional nature. It’s a scenario that allows activities to happen which are commonly not accepted in public spaces. The project uses digital phenomena that are emerging in nonplaces like this, putting them in a relationship with people. The diversity of strange elements is the starting point of the design and is used to further develop their strangeness into follies of the future garden, based on the historic model of the English pleasure garden.

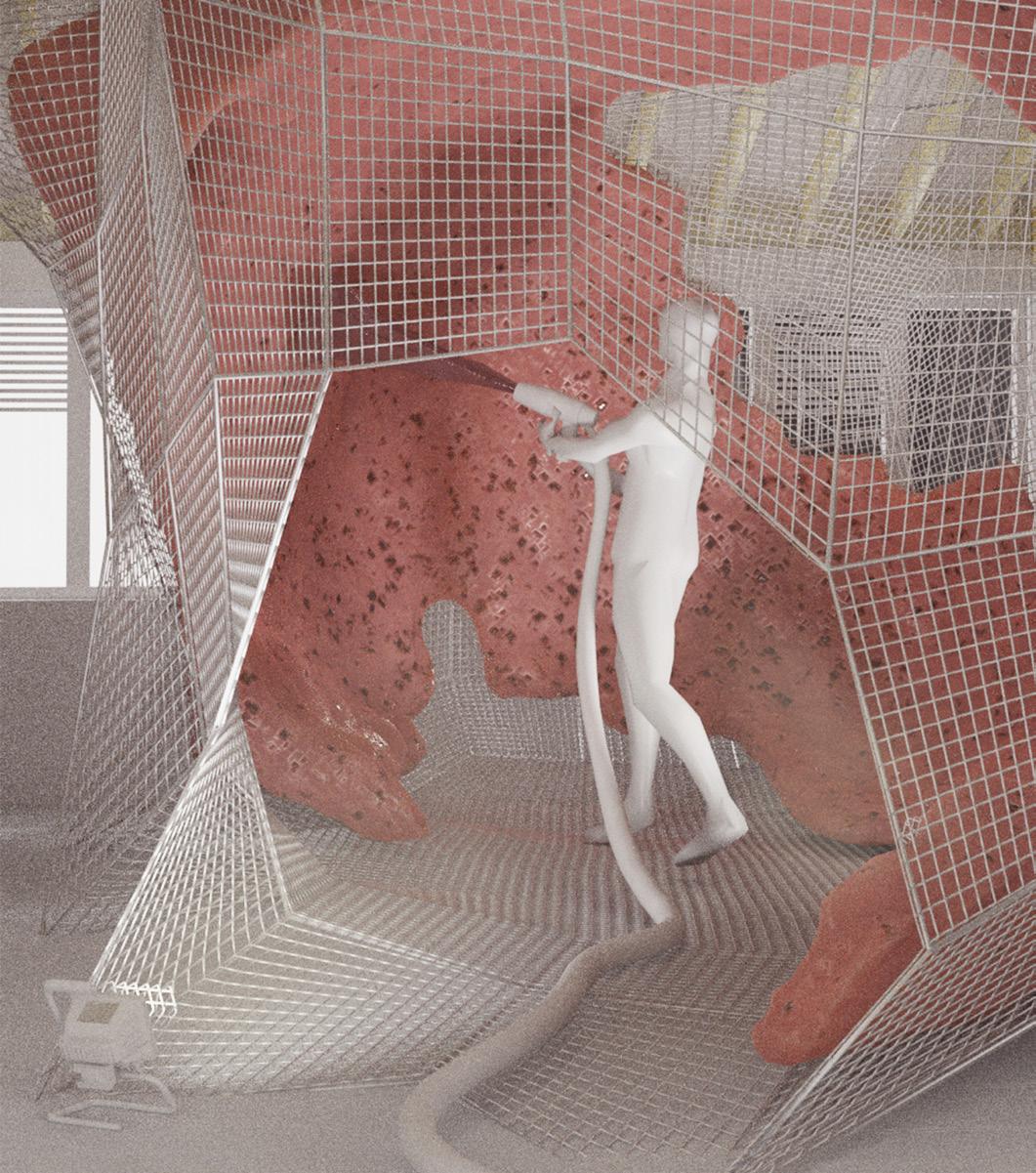

Bromley Intimate Garden

This project translates unused nonresidential property through the act of squatting into a hub for the CV Dazzle community to meet and exchange within a new spectrum of intimacy. Here, translations are a series of actions that gradually reconfigure an existing structure to a new typology and through these, opens itself to the public shifting from unused space to a common place for all. Intimacy: being able to contemplate and meet without the fear of being seen, heard or tracked.

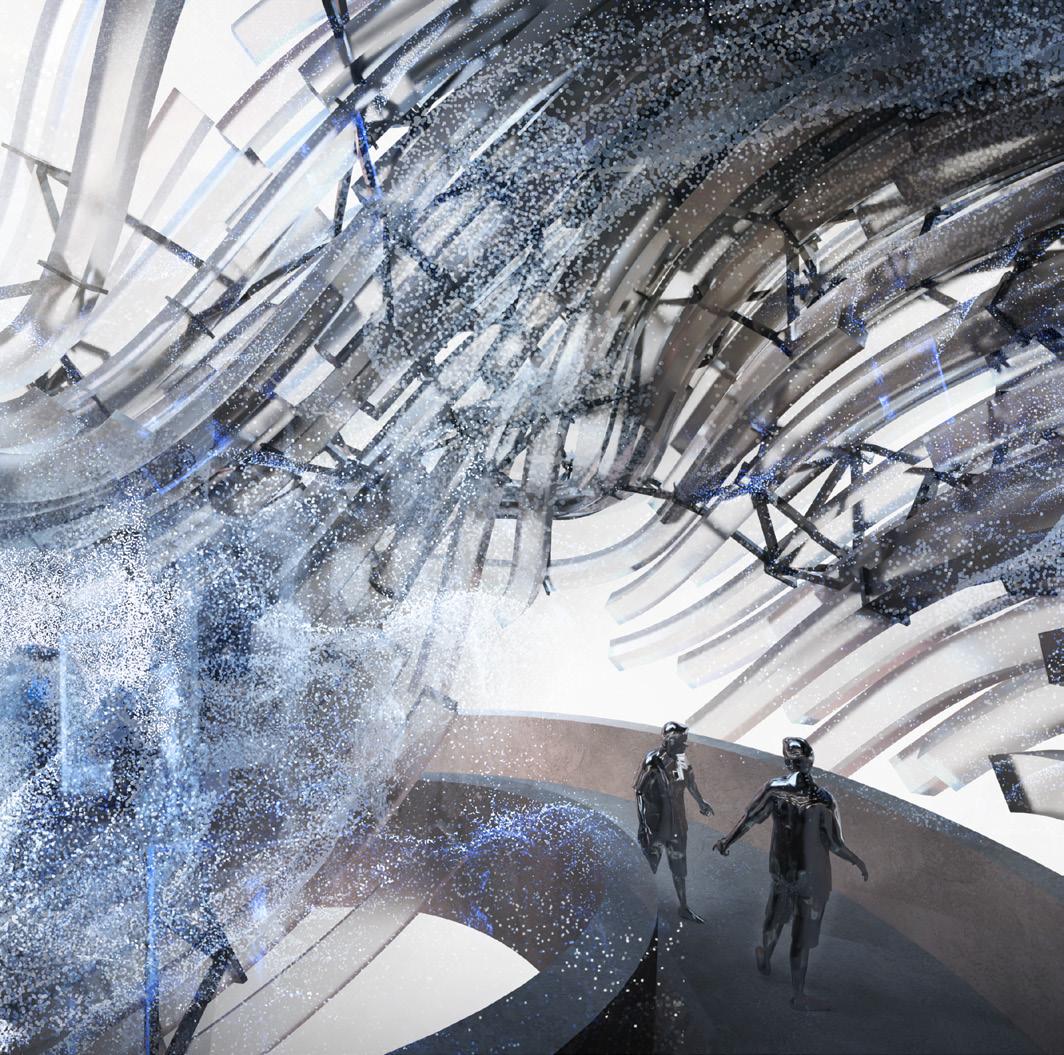

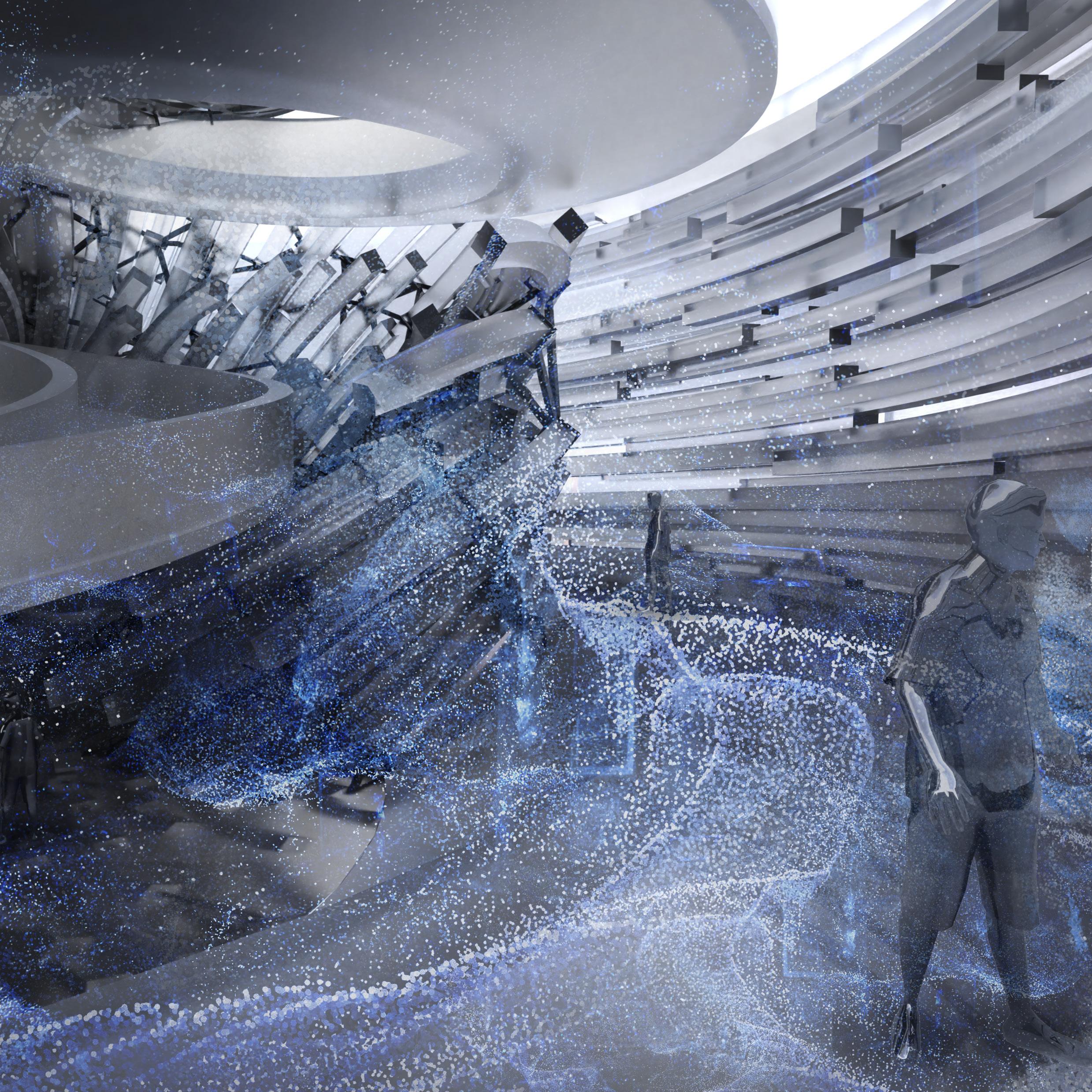

Reminisce Architecture - A Digital Fossil

Reminisce Architecture is about storing and revisualizing zeitgeist memories through architecture — specifically, how memories can become an architectural manifestation within a museum typology, as a monument and as a time capsule. Executed by three main design components and their corresponding technologies, digital fossils serve as memory-archives, memory theatres for the experience, and an agora as a place for discourse. A main influence for the project was Giulio Camillo’s Memory Theatre, specifically because it was not only an archive of knowledge, but even more, a renaissance search machine. Icons help to find our way through a labyrinth of information. Inspired by that, the digital fossils are accessible and browsing through the archive is made possible by making the stored memories visible as holograms with AR contact lenses. As a hybrid architecture, you can visit Reminisce Architecture on site, but also from all over the world with a digital device. As every visitor will be wearing AR lenses, the hybrid agora is a place where virtual avatars and actual individuals can meet and discuss zeitgeist memories.

In conclusion, the building is not only a storage for zeitgeist memories collected from all over the world, it is also a place to reimmerse oneself in and experience collective moments turning into a fossil over time…

Clare Lyster is an architect based in Chicago, where she is an associate professor at the UIC School of Architecture. Her work looks at urban sociotechnical systems and how they shape the built environment. She has authored or co-edited several books, including Learning from Logistics: How Networks Change Cities (Birkhäuser, 2016). Recently, she focused on data information systems for her project, Entanglement (Venice Architecture Biennale, 2021), and is currently looking at agricultural systems for a book called Future Farm Formats.