The Fate Of SF State’s Hidden Gem

Overcrowded Bay Area

Animal Shelters

Pokémon GO Culture

On Campus

Overcrowded Bay Area

Animal Shelters

Pokémon GO Culture

On Campus

As we start the school year, there is a renewed sense of beginning. The quad is busy with student groups looking for fresh blood and freshmen navigating their new environment. While the campus may feel as if it’s bursting with life, enrollment continues to decline. Budgets have been slashed in different departments, resulting in class cancellations across the university. Our Tiburon campus across the bay is at risk. And for Xpress, it’s having to cross “four (more) print issues” off the drawing board. But not all is lost.

Like all groups on campus, we have to work with what we have and make that work. Getting creative is all we can do to make the dollars we do have stretch. Though our first and last issue won’t be in print, the online format pushes us to explore new ways of reaching our readers while also expanding our current skill set. This semester, we launched our online column “Ask Xpress’’ and are looking forward to answering the questions that plague our student body.

– Zackery StehrStaff Writers

Zackery Stehr

Andrea Sto. Domingo

Nadia Castro

Daniela Perez

David Ye

Leilani Xicotencatl

Tam Vu

Alicia Montoya

Ella Lerissa

Amy Burke Bessette

Andrea Jiménez

David Chin

Div Lukic

Enrique García

Faya Beeldstroo

Giovanna Montoya

Isabella Minnis

Lydia Perez

Sarah Louie

Sydney Williams

Photographers

Andrew Fogel

Colin Flynn

Feven Mamo

Neal Wong

Spotify Playlist

A curated collection of dreamy melodies.

The odds and ends in the Mission District.

Ryosuke Kojima 03 13

04 07 17

As enrollment continues to decline at SF State, the fate of the EOS center may be grim.

Bay Area Animal Shelters Face Overcrowding

A tale of two cities… and countless dogs.

Yes, People Still Play Pokémon GO

Gotta catch them all!

Pokémon GO culture at SF State.

1. Open Spotify

2. Tap search bar

3. Tap camera

4. Scan code

5. Listen 6. Enjoy

1. Open Spotify

2. Tap search bar

3. Tap camera

4. Scan code

5. Listen 6. Enjoy

In the heart of the Mission, the surrounding streets are spotted with canopy tents and fold-out tables belonging to street vendors. T-shirts and jeans are strung up on clotheslines for passing pedestrians to inspect, tortillas sizzle in pans of hot oil and jewelry is spread out on plaid-covered tables.

Within the outdoor community space City Station, SF State alum and Porter Vintage proprietor Katie Porter sets up tables and clothing racks packed with vintage clothes, boots, jewelry and accessories like bandanas and sunglasses. In addition to leasing a space in City Station, Porter also has a street vendor permit for when she operates outside of the parking lot.

While Porter may be permitted, she’s one of the exceptions among other street vendors in the Mission.

“We’re here every weekend, so we gotta be as legit as possible,” Porter said.

Although their products vary immensely, there’s something many of San Francisco’s street vendors have in common: the lack of a street vending permit. San Francisco’s Public Works Department only specifies two kinds of vendors that are ineligible for a permit: vendors of alcohol and vendors of unpackaged food or drink.

Eric Molina is one such vendor. Like many other vendors, he spends his weekends at Dolores Park walking back and forth, up and down the steep hills of the park, weaving his way between picnic blankets and unleashed dogs, waiting for someone to beckon him over to make a purchase.

Molina began his career as a street vendor in the spring of 2020 after being let go from his job in the hospitality industry due to COVID-19. Originally from Peru, Molina was used to seeing people set up little shops in public spaces to sell their products. After hearing about someone making a living from selling rum and coconuts in Dolores Park, he decided to start selling mixed drinks in the park himself.

“There’s people who have to find the ways to survive,” Molina said. “The funny part for Americans is the world has changed so much, you know, what we did in South America, for survival, it became a norm.”

Indeed, this fight for survival is happening in Dolores Park. Vendors of alcoholic drinks are not uncommon in the park and neither are vendors of other prohibited substances like marijuana and psilocybin mushrooms. Although vendors like Molina do not qualify for a street vending permit, the business could still be profitable enough to withstand any potential tickets or fines.

According to Molina, Dolores Park vendors who are caught selling without a permit are told to pack up and leave. If they’re caught again, they can be fined $100-$200.

For Molina, vending can be more lucrative than most jobs. He may be

Street vendors are a common sight on the streets of San Francisco, although valid street vendor permits are a bit rarer.

making a comfortable living off his street vending, but this isn’t necessarily the case with every vendor.

J.B. Higgins is another street vendor without a permit but he doesn’t sell alcohol or unpackaged food. He’s a photographer who sets up his table at many of the city’s art fairs to sell prints of the scenes he captures within San Francisco.

Higgins has been taking photos since 1977 and has recently decided to make some money through his hobby. His application process came to a halt when he lost the email address he originally applied with. Qualifying for a permit might seem like a simple checklist of requirements but unexpected issues like this can slow or even stop the process. Thankfully, Higgins’s street vending is a secondary source of income, unlike many vendors.

“This is a side hustle, but sometimes I’ll make enough money for this to be my main gig,” Higgins said.

Estella Estrella sells makeup, beauty creams and boxes of hair dye on the sidewalk of Mission Street. As a full-time vendor, Estrella is much more reliant on the profits from vending compared to Higgins. According to her, the daily profits from street vending can fluctuate dramatically.

“Sometimes it’s $100, sometimes $40 or $50, sometimes nothing,” Estrella said.

Estrella is one of these legitimate vendors who was able to obtain a street vending permit. She got her permit with the help of Calle 24, a Mission-based nonprofit that helps local Latinx business owners with the process of applying for a street vending permit. Although Estrella is now fully permitted, she still has to keep track of all business-related documents. She’s been ticketed several times after failing to show receipts of where she purchased her products.

Although Higgins and Molina haven’t been able to obtain street vending permits, the city has issued close to 200 permits since Mayor London Breed signed the street vending legislation in July 2022, according to San Francisco’s Department of Public Works Deputy Director of Policy and Communications, Beth Rubenstein.

Down the block from Estrella, Manuel Lopez sells a variety of “Mexican cravings” such as elote, chicharrones preparados and tostilocos. He also received a permit with the help of Calle 24. Like Estrella, he has sometimes been punished for failing to adhere to the rules of the street vendor permit. Even after successfully receiving permits, street vendors have to be mindful of all of the accompanying rules and regulations.

“The health department sometimes throws out our stuff… you need to have all the food covered in ice and sometimes we just forget the ice,” Lopez said.

Although the city recognizes the presence of unpermitted street vendors, there has not been any assessment of the exact number of them. According to Rubenstein, unpermitted street vendors can get wary when asked about their permit status, which makes getting an estimated number of unpermitted vendors difficult.

“We believe that there are many who are selling stolen goods and therefore would not be interested [in obtaining a permit],” Rubenstein said.

“There’s people who have to find the ways to survive... The funny part for Americans is the world has changed so much.”

The city’s attitude is not to chastise and punish unpermitted vendors, but to educate them.

“Our inspection teams work first to educate vendors. When asked, if a vendor doesn’t have a permit, we talk to them about the process of obtaining one,” Rubenstein said.

By preventing the sale of stolen goods and enforcing health regulations on food and drink vendors, issuing permits to street vendors has made neighborhoods cleaner and safer.

“From our work with community groups, legitimate vendors have welcomed the program as it makes their neighborhoods safer and sidewalks and Muni stops more accessible,” Rubenstein said.

“From our work with community groups, legitimate vendors have welcomed the program as it makes their neighborhoods safer and sidewalks and Muni stops more accessible.”

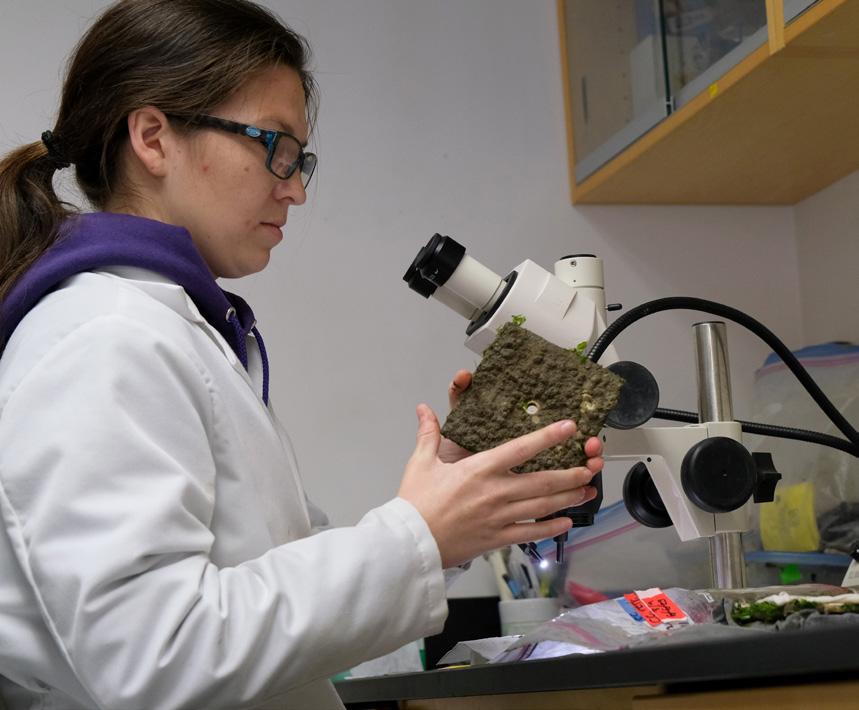

As enrollment rates continue to decline, the budget continues to shrink, leaving the fate of SF State’s Estuary & Ocean Science (EOS) Center unknown.

Story by Isabella Minnis

Photography by Andrew Fogel and Gina Castro

Story by Isabella Minnis

Photography by Andrew Fogel and Gina Castro

Starting on a windy unpaved road accompanied by trees that cover the sun, you begin to make your way to SF State’s Tiburon campus. After passing the South Barracks with chips in its wood dating as far back as WWII, you finally meet the sea. On one side, you see the perfect image of the Richmond-San Rafael bridge while on the other, seals and birds roam free.

Upon entering the Delta Hall, where the main laboratories, offices and classrooms are located, there is a range of experiments being conducted by researchers and SF State students such as shoreline restoration and the monitoring of sea level rise in connection to climate change. But despite the center’s natural pleasantries and the importance of its research, SF State may soon turn away from the center, citing its lack of financial sustainability amidst broader university budget concerns.

SF State’s Estuary & Ocean Science Center is located on the university’s Romberg Tiburon Campus, just 20 miles from SF State’s main campus. This 53-acre center looks on the San Francisco Bay and despite its 8-decades long streak without any renovations, this campus is rich with history.

In 1977, the proposal to develop a field station and marine lab dedicated to the study of the San Francisco Bay was submitted by then-SF State president Paul Romberg. The following year, several building renovations were completed including a greenhouse and experimental tanks built near t he campus’s boat ramp.

With the launch of the Estuary and Ocean Science (EOS) Center in January of 2017, the Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies was renamed to the Romberg Tiburon Campus in honor of Romberg himself.

With the SF Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s west coast lab headquartered at the site, it has become the core and link of many collaborative estuarine and coastal ecosystem research and educational activities.

Together, students and researchers cover most of the sensitive issues in the bay today, including nature-based solutions to climate change, impacts of freshwater diversion, human additions of pollutants, invasive species, wetland restoration, harmful algal blooms and marine mammal and bird conservation.

Since June 2022, Katharyn Boyer has acted as the Interim Executive Director of the EOS Center. She has also been a biology faculty member since 2004, making her experience with SF State over 20 years.

Additional research also includes monitoring the effects of climate change and changes of sea level rise using the science and equipment provided by the EOS Center.

“A lot of the restoration work that my research lab does now is very much focused on how to use native species for climate change adaptation or mitigation,” Boyer said. “So we’ve been interested in these native species and their restoration for many decades but now we’re interested in thinking about how we can do that restoration in a way that serves other purposes for climate adaptation and mitigation.”

Students use fleet boats in order to actively get involved in the research and have the opportunity to learn how to restore

and understand the environments of the San Francisco Bay.

“Students participate in all the research that we do and the EOS Center is essential for that research, because it’s right on the bay,” said Boyer. “It allows us to get out to the places that we’re restoring or studying to understand how best to do the restoration with our boats.”

Additionally, the EOS Center provides the researchers and students with a watering system called a bay water system, where water from the bay is extracted from a pipe and filled into the tanks and aquaria that is used within the center for experiments. This system is unique to the center in the sense that it simulates the environment of the bay within the center.

“It means we have an opportunity to simulate the bay conditions and study them and to do the restoration and conservation work that no one else has the ability to do,” Boyer said. “And so it’s an amazing resource that San Francisco State has that no one else has. None of them have this kind of a system on the bay that allows us to manipulate the conditions like this and to really understand how the bay works.”

Without this center, the research faces danger of discontinuation and SF State’s mission to connect science, society and the sea will cease to exist. However, despite the EOS Center’s current estate, SF State’s current president, Lynn Mahoney, states that no plans to improve the buildings at the site are in the works.

“The answer is no. We have no plans to touch those buildings,” President Mahoney said. “It has to support itself. I need every penny we have to support the campus here.”

Now that the facility is facing financial issues concerning upkeep and an uncertain future, members of the SF State community such as Adam Paganini are reflecting on the center’s importance to the SF State community.

“I know every part of SF State is looking for budget solutions so I don’t think there’s any malicious intent on the part of the university to target the EOS Center for termination,”

Paganini said. “But it’s a gem of the university, it is definitely a bright spot on the university’s record. That would be a total waste if they let it die.”

Paganini, the former Interdisciplinary Marine and Estuarine Sciences graduate program coordinator, was a student at the EOS Center in 2009. He proceeded to enter the graduate program at the center in Jonathon Stillman’s lab and graduated from the program with his master’s degree. He then worked as a monitoring technician at the center and conducted research.

“Students participate in all the research that we do and the EOS Center is essential for that research because it’s right on the bay.”

During his graduate experience, Paganini remembered how the EOS Center’s minimal funding affected the students and their ability to perform experiments vital to their education.

“There wasn’t infrastructure ready to go for a grad student who wanted to study XYZ,” Paganini said. “You basically had to build it from scratch.”

According to Paganini, the student along with the professor would have to accumulate the money needed to conduct research and construct an experimental setup at the center. As a result, students would learn how to build scientific equipment from scratch. This raised other issues, as graduate students would spend more time building equipment than actually working on their assignments.

Jason Porth, vice president for University Enterprises at SF State, said President Mahoney asked a group of people to form the Committee for Fiscal and Operational Sustainability, which has been meeting since May 2023. The committee works to evaluate the costs of running the EOS Center, the risks and opportunities there and determine whether the campus can have a financially sustainable future.

“The committee was asked to look at a range of alternatives,” Porth said. “Everything from what would happen if we had to look at everything that happens out there and move back to the Holloway campus and discontinue use of the site all the way to how do we invest in the site and find ways that might

ultimately generate revenue going forward.”

Caitlin Steele, the director of Sustainability and Energy at SF State and one of the committee’s 11 members, is tasked with evaluating the site’s physicalities and devising a plan based on what new buildings could be built and what pre-existing buildings could be repaired. She has been contemplating these different options for what to do with the site since before the pandemic, such as enlarging its conference center or converting the center to a housing site.

This updated vision plan has yet to be released, but the latest vision plan from 2019 mentions these improvements.

“The committee was thinking quite broadly about how we might find ways to make the site valuable to continue the important research and scholarship that goes on there, but also to address some of the most vexing issues facing the Bay Area,” Porth said.

Porth was referring to two specific on-site buildings that were barracks for enlisted naval personnel who worked on the site. According to Porth, each of the barracks is just under 18,000 square feet. However, the appropriate federal funds needed to support a renovation would cost around $20 million per building.

According to Steele, one of the main issues with Tiburon’s site is students commuting from the SF State’s main campus to the Tiburon campus.

“In the vision plan, we looked at transit as it has always been

an issue with the Tiburon’s site,” Steele said.

But according to Paganini, SF State had a shuttle that would go from the main campus to Tiburon twice a week. The shuttle was discontinued eight or nine years ago, Paganini said.

“In fact, there was one point in which I was hired to drive that shuttle for a semester as a grad student,” Paganini said. “That was very helpful because, you know, that would allow students from the main campus to come take classes out at the EOS Center and it would also allow students at the EOS Center to go to campus together.”

Since then, there hasn’t been any recorded efforts by the university to bring an alternate method of transportation for students to commute to the Tiburon campus specifically. However, SF State has provided students with a regional transit pass called the Clipper BayPass, which gives students unlimited free access to all Bay Area transit systems that use the Clipper system, such as Muni and BART.

“There was nothing since then in terms of transportation that I can think of from the university perspective that would help students get out there,” Paganini said. “And getting out there is a pain in the ass.”

According to the EOS Center homepage, the only listed way to get to the Tiburon campus from the main campus is by driving. According to Google Maps, it takes 40 minutes by car and over two hours by train.

“I think that there are a lot of students and others on our

“

It’s a gem of the university; it is definitely a bright spot on the university’s record. That would be a total waste if they let it die.”

main campus who don’t even know that we have this facility out in Tiburon,” Boyer said. “And it’s your facility. And now it’s your place to come and be on the water and learn and participate and gain the skills you need for this job market.”

Paganini also added that places like the EOS Center are important in this time in history and vital for our futures, given the escalating effects of climate change.

“We’re dealing with the climate crisis and an environmental justice rectification that needs to happen,” Paganini said. “I cannot overstate that because this is where the next generation of STEM professionals and climate change researchers are going to learn their craft. And if you don’t invest in that, you’re creating a vacuum that can be filled by other things that aren’t going to help with the climate crisis and aren’t going to help solve societal challenges that climate change is causing.”

“And it’s your facility... it’s your place to come and be on the water and learn and participate.”

Multiple issues animal shelters face accumulate to the main problem of overcrowding.

The echoes of barking dogs fill animal shelters across the Bay Area, with more dogs than there are kennels to house them. Local animal shelters struggle to find alternatives to euthanization.

According to an Oakland Animal Services report from 2020 to 2022, there was a 31% increase in dogs that resided there. Similarly, in a 2019-2023 report from SF Animal Care and Control, there was a 19% increase in dog residents.

Recently, Oakland Animal Services euthanized two dogs due to the lack of space in the shelter. According to Director of Oakland Animal Services Ann Dunn, the shelter frequently updates its website for dogs who are in urgent need of getting adopted to try to avoid euthanization.

“At 73 [kennels], we have no space for incoming dogs. So if we’re at 100 dogs, that means many of those dogs are in half-kennels, which is really just not fair to them, and something we can’t do for very long,” said Dunn. “And I’ll say we’ve been able to avoid euthanizing for space largely up until this point, but it’s getting harder and harder.”

Dunn said with an average of 10 dogs coming per day, the shelter gets an adoption average of 30 dogs per week and yet constantly leaves them at maximum capacity.

“We’re doing everything we can to save these dogs,” Dunn said. “But this is not about numbers, right? This is a life that is in our care, and to be in a position where we really felt like we had no other choice.”

Oakland Animal Services’ underlying issue is partially due to a veterinarian shortage, according to Dunn. She also added that people who have animals can’t get them spayed and neutered because of a lack of access to veterinary care.

Chloe Ettinger, a recent SF State alumna and founder of the Pre-Veterinarian Society Club at SF State, said one of the factors that play into the national veterinary shortage is that it’s hard to get into veterinary school, citing her own experience applying to veterinary schools.

The same holds true even for prospective veterinary students from other schools; the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California, Davis, saw 1,007

“It’s a constant game of trying to fit the pieces into the puzzle, and they don’t always fit. It’s not just a Bay Area problem, but it’s a national problem.”

total applicants for its Class of 2025, but only 149 were accepted. UC Davis’s veterinary graduate program is also only one of two in California ‒the other being the College of Veterinary Medicine at the Western University of Health Sciences, according to the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges.

Ettinger also said from her understanding, a factor of the overcrowding is adoptions made during the pandemic. Now that things are going back to normal, people aren’t able to take care of the animals.

“People have realized that they can’t actually take care of these animals probably as they had been and so a lot of pets are ending up back in the shelters which I think is a factor in the overcrowding,” Ettinger said.

SF Animal Care and Control volunteer and outreach coordinator Deb Campbell agrees that the pandemic has played a role in overcrowding at shelters.

“It’s a constant game of trying to fit the pieces into the puzzle, and they don’t always fit. It’s not just a Bay Area problem, but it’s a national problem,” Campbell said.

Since SF Animal Care and Control is an animal law enforcement agency, which has control officers who respond to animal emergencies. Even as three to five dogs adopted a week, Campbell said the problem lies in the influx of unadoptable dogs.

“They’re taking in animals from situations like cruelty [environments] [and] investigations. These animals come to us, and they stay with us indefinitely,” said Campbell.

The majority of their overcrowding issue is animals that go into SF Animal Care and Control are in other programs the shelter has that are non-adoptable or can’t be sent to a rescue.

Campbell said since any animals are taken in, there are certain animals that aren’t adoptable due to some being older and sick, etc. Muttville is

one of the many rescues that partner with shelters to receive such animals.

A cage-free dog rescue in SF, Muttville focuses on giving older dogs homes. Rescue partners give Muttville dog-tolerant dogs that can live in cagefree rescues.

“One of the challenges is that senior dogs tend to be more overlooked by adopters who walk into a shelter. If you think about it, a lot of folks who go to a regular local municipal shelter are probably looking for family dogs,” Alice Ensor, Muttville’s adoptions coordinator said. She added that adopters don’t want to spend money on medical costs.

In 2020, Oakland Animal Services started a fostering program for big dogs and has changed the way they do adoption.

“Well, I would put it like this. Small dogs fly off the shelf. And as soon as we have small dogs available for adoption, they get adopted right away,” said Dunn.

According to Dunn, in 2019, 17% of dogs that came into the shelter were euthanized. That figure dropped to 5% because of the foster program.

Logan Daniels signed up for Oakland Animal Services’s foster program recently after finding out about the dogs who were on the priority list. He and his partner were notified about being able to foster and were shown several dogs, including Angelo, a 2-year-old German Shepherd mix. Daniels described Angelo as a sweetheart who’s young at heart and a companion.

“So I look at him and I’m like ‘Dude, how could you still be here, you’re gorgeous, dude,’” Daniels said. “I’ll always do whatever I can to help them because I’m definitely not for euthanizing anything ever.”

Another option to reduce overcrowding is for

shelters to try to locate their family by scanning the dog for a microchip.

“When a dog comes in as a stray, they have a hold time that the shelter has to keep them while they try to locate an owner,” Ensor said. “If the dog is chipped, it lengthens that time because they usually need to try and call and send a letter to the address on file for that microchip,” Ensor said.

For dogs, being in half-kennels can create a mixture of stress, confusion and sometimes a kennel cough: a highly contagious respiratory disease according to American Kennel Club – or as Dunn puts it, the canine equivalent of a human cold.

Despite the overwhelming number of reasons for overcrowded animal shelters, people like Dunn continue to work hard to find each and every animal a home they can live peacefully in.

On

On

“Unless there’s some miracle and our intake starts going down, every week we will have dogs in that category [up for euthanization] because that is just our reality right now that there are just far more dogs coming in than we can help,” said Dunn. “It’s terrifying, honestly to think ‘What does that mean for the future?’”.

“Unless there’s some miracle and our intake starts going down, every week we will have dogs in that category [up for euthanization] because... there are just far more dogs coming in than we can help.

Story by Daniela Perez

Photography by Neal Wong

Story by Daniela Perez

Photography by Neal Wong

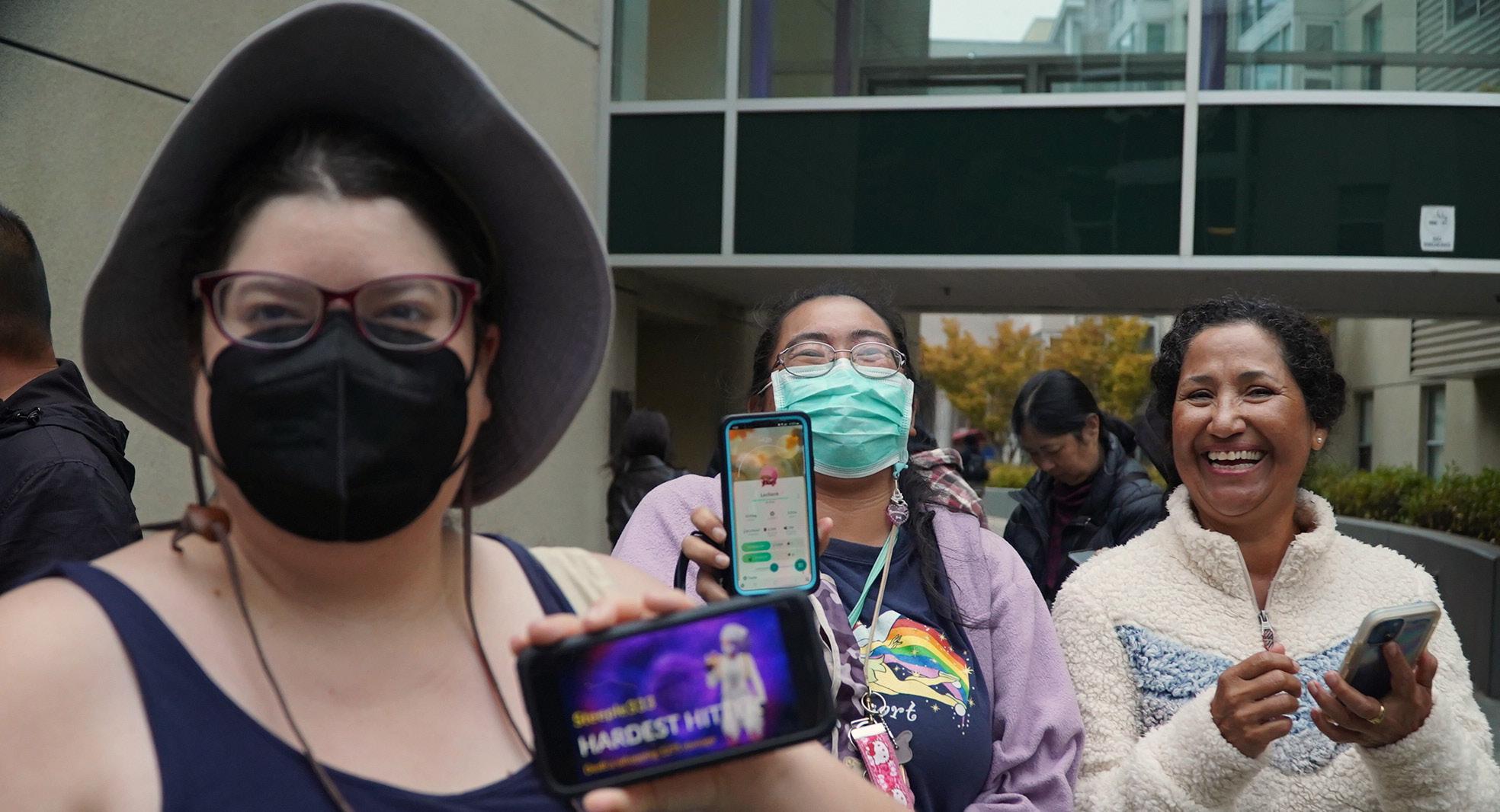

Behind the Humanities building, right outside of Taza’s Smoothies and Wraps at SF State, stands an 8-foot-tall time-worn copper statue of a couple dancing. It’s just a statue — what more can be seen To Pokémon GO players, their phone is a lens that opens to an augmented reality world of Pokémon. Their phone immerses players into a world of catching, collecting and battling Pokémon.

On the player’s phone screen, the statue digitally converts into a Pokémon gym: an inverted multi-ring tower structure on top of the location where players meet to digitally battle rival Pokémon teams.

Gwen Northcutt, a Japanese major student at SF State, is the only person huddled in a small corner near the statue on a Wednesday night. They are looking down at their phone, occasionally looking up to the players around the area. With Miniso shopping bags hanging from their forearm, they quickly tap on their phone screen.

Their main objective is to defeat the legendary in-game Pokémon raid boss, Primal Groudon, at the Pokémon gym. Every Wednesday, players have the opportunity to team up and battle a legendary Pokémon between 6-7 p.m. A new legendary Pokémon appears, offering a chance to collect the strongest Pokémon variant for a player’s collection. Raid bosses are categorized by levels and players must team up to battle and defeat the boss Pokémon to capture it.

Northcutt has played Pokémon GO since the game’s debut on July 6, 2016 and has never missed an in-game event. They always try their best to accommodate their schedule to participate in the community days featuring a single Pokémon throughout the whole day and in the Wednesday Raid Hour.

In 2016, Pokémon GO was a sensation. It soared to the No. 1 spot in both Free and Top Grossing Apps on the Apple App Store just one day after its release. Players swarmed around city streets and parks, with their heads down and eyes locked on their phones, continuously swiping upward, trying to capture the Pokémon that appeared on their screen.

The game immerses players as if they are Pokémon trainers catching, collecting and battling Pokémon. Some players have been dedicated to the game since its initial release and a Pokémon GO community exists at SF State.

In Pokémon GO, there are PokéStops where players can stop to collect free in-game items like Pokéballs and potions to capture more Pokémon to increase in-game experience points, known as XP. These PokéStops include campus hallmarks such as the bronze Gator on top of a basketball in front of the Don Nasser Family Plaza, the granite cast of St. Francis’ head in the center of the quad and the colorful murals in front of the Cesar Chavez Student Center.

While circling around the quad, collecting Pokémon and joining in raids, Northcutt found a community of players at SF State. They can easily distinguish who is a player by observing the way someone swipes at their phone to collect items at the PokéStops or by the way they throw a Pokéball to capture a Pokémon.

“Usually if they look at their phones, and if they do a very specific kind of like — the way you throw a Pokéball, you have to do a little spin or if you’re tapping for like the raid, but that also — Pokémon GO players tend to have

extra battery packs so if you see someone connected to a battery pack while playing, that’s a good sign too,” Northcutt said.

Every Wednesday, players gather at the Norma Urcuyo-Siani Dedication gym, located at an ordinary bench near City Eats. From there, players make their way through a gym route, battling the weekly raid boss around campus. Families, neighboring residents, students and a cat in a carrier, walk their usual route toward the last Pokémon gym near the 19th Avenue Muni stop.

Hans Wu, a neighboring resident and active player since 2016, walks with the group. He occasionally brings his cat Mochi in a backpack carrier to accompany him while he plays. Mochi, the gray short-haired cat, hops in and out of her carrier and roams around the screen-tapping players. Wu believes the game itself is different in a way that makes others socialize and go outside.

“The nature of the game being, you know, very accessible and pretty easy to pick up and then being social and getting outdoors, you know, a lot of these people are pretty regular and you get to just know each other,” Wu said.

Players huddle together once they defeat the Pokémon raid boss. They step aside to form a circle to reveal a catchable version of the boss raid Pokémon. Everyone places their phones in the middle and, at the count of three, tap the screen in hopes of encountering a rare shiny or different colored version of the Pokémon they defeated. One, two, three — no one was lucky.

“But here, you know, elements of the game could be social in addition, right, because you can’t beat these raids on your own,” Wu said. “And so, you know, because of these raids, people started playing a little bit more together and then realize ‘Hey, that social aspect is a plus.’”

Slowly, the group of players walk toward the mosaic-encrusted SF State Tiger statue. Gloria Paz, an SF State alumna who started playing Pokémon GO in 2019, walks with the group. She looks down at her phone and tries her best to capture the Pokémon on her screen. Despite having graduated 25

years ago with a Master of Science in Accountancy, she continues to have fun with others on campus while feeling safe.

“I am semi-retired, and Pokémon makes me walk around and I feel safe here,” Paz said. “It’s mostly safety and also the crowd because if you go to other places, you don’t see other people playing, and here I always find people that I recognize, and I graduated, what, 25 years ago.”

Ryan Gabuyo, a visual communication design major at SF State, falls behind the group with his head down, capturing the Pokémon appearing on his screen. He has been playing the game since 2016, with occasional breaks.

Gabuyo enjoys capturing Pokémon at various locations, especially during special in-game events like the recent global event celebrating the game’s seventh anniversary, Pokémon GO Fest.

“Campus is kinda the easiest place to go because of all the stops, all the gyms, all the spawns, but for then maybe special events like this past weekend, Pokémon GO Fest, I went to Fisherman’s Wharf and I saw other people and students. A lot of locals go there because it’s very active.”

During Pokémon GO Fest, players gather at locations that have multiple PokéStops and Pokémon gyms to take advantage of the increased chance of capturing a shiny or new Pokémon and battling legendary Pokémon.

Shiaina Butler, a psychology major at SF State and a recurring player since 2016, plays Pokémon GO around campus but has never joined the group that walks around campus. She enjoys the game and often encourages her friends to play.

“So I think it’s just because there’s always so many things you can do in the game and it’s just constantly with them adding new Pokémon and new features all the time,” Butler said. “It’s never a boring moment playing the game.”

What keeps players coming back to Pokémon GO, you might ask?

The answer varies per player. For some, it’s the health incentive of walking and being active. For others, it’s the excitement of collecting and catching while playing with people who enjoy similar interests — including me.

“So I think it’s just because there’s always so many things you can do... It’s never a boring moment playing the game.”