July/August 2024 Douglas Fir Die-Off In Southern Oregon Gives A Glimpse Into The Future Of West Coast Forests

July/August 2024 Douglas Fir Die-Off In Southern Oregon Gives A Glimpse Into The Future Of West Coast Forests

“Aside from the excellent Applegate wines I’ve had from producer, Vineyard, made such an impression on me over the last few years that I from the July the attitude, which are

“But Aside from the excellent Applegate wines I’ve had from Willamette producers, the wines of one producer, Troon Vineyard, made such an impression on me over the last few years that I drove seven hours from the Mendocino Coast in July to pay a visit to Applegate Valley, While I admire the way Troon farms and its empirical attitude, the proof is in the wines, which are invariably fresh, lively and expressive,”

—Eric Asimov The New York Times

—Eric The York

JPR Foundation

Officers

Ken Silverman – Ashland

President

Liz Shelby – Vice President

Cynthia Harelson –Medford/Grants Pass

Treasurer

Andrea Pedley – Eureka

Secretary

Ex-Officio

Rick Bailey

President, SOU

Paul Westhelle

Executive Director, JPR

Shelley Austin

Jefferson Live Executive Director, Ex-officio

Directors

Eric Monroe – Medford

Ron Meztger – North Bend

Rosalind Sumner – Montague

Dan Mullin – Eugene

Margaret Redmon – Redding

Karen Doolen – Medford

JPR Staff

Paul Westhelle

Executive Director

Darin Ransom

Director of Engineering

Sue Jaffe

Membership Coordinator

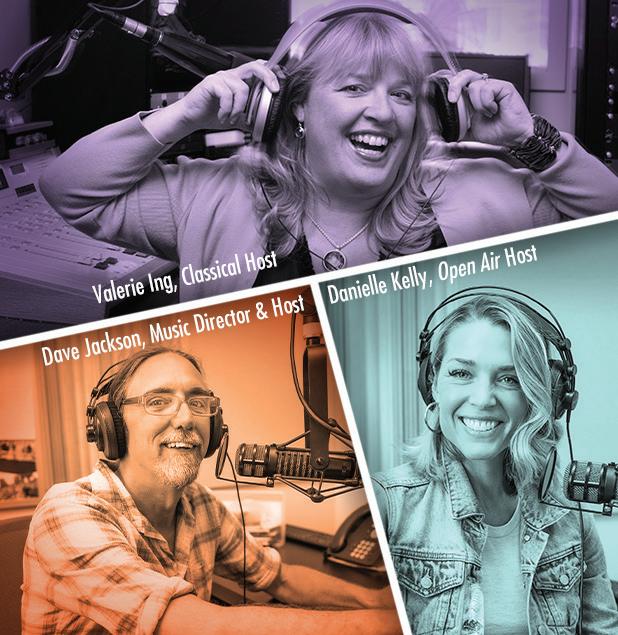

Valerie Ing

Northern California Program Coordinator/Announcer

Abigail Kraft

Business Support Manager/ Jefferson Journal Editor

Geoffrey Riley

Assistant Producer/

Jefferson Exchange Host

Erik Neumann

News Director/Regional Reporter

Dave Jackson

Music Director/Open Air Host

Danielle Kelly

Open Air Host

Soleil Mycko

Business Manager

Angela Decker

Jefferson Exchange Senior

Producer

Charlie Zimmerman

JPR News Production Assistant

Zack Biegel

JPR News Production Assistant

Calena Reeves

Audience & Business Services

Coordinator

Liam Bull

Audience Services Assistant

Vanessa Finney

All Things Considered Host

Roman Battaglia

Regional Reporter

Justin Higginbottom

Regional Reporter

Jane Vaughan Regional Reporter

Milt Radford

Morning Edition Host

Dave Young

Operations Manager

JPR News Contributors

Juliet Grable Kelby McIntosh

Don Matthews

Classical Music Director/ Announcer

JEFFERSON JOURNAL (ISSN 1079-2015), July/August 2024, volume 48 number 4. Published

bi-monthly (six times a year) by JPR Foundation, Inc., 1250 Siskiyou Blvd., Ashland, OR 97520. Periodical postage paid at Ashland, OR and additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to The Jefferson Journal, 1250 Siskiyou Blvd. Ashland, OR. 97520

Jefferson Journal Credits:

Editor: Abigail Kraft

Managing Editor: Paul Westhelle

Poetry Editor: Amy Miller

Design/Production: Impact Publications

Printing: Oregon Web Press

By Erik Neumann

Douglas fir trees around Ashland are dying in the thousands. It’s one example of how our changing climate is affecting forests in the region. Experts are calling it a decline spiral. Others are calling it “firmageddon.”

By Jamie Hale

In recent years, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians have created opportunities for members to reforge connections to the lands their ancestors knew intimately. Their removal from this place in 1856, an event some historians call the Rogue River Trail of Tears, has become a road map that many tribal members are retracing into the future.

PAUL WESTHELLE

Abill championed by Oregon Senator Ron Wyden that would establish federal protections for the newsgathering rights of journalists received new energy recently when the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP) submitted a letter to the U.S. Senate urging it to pass the PRESS Act (short for the Protect Reporters from Exploitative State Spying Act). The letter was endorsed by 53 national news organizations.

The PRESS Act would prohibit the federal government from compelling journalists through the use of subpoenas, search warrants, or other compulsory actions, to disclose information, identify confidential sources, or provide newsgathering records except in very limited circumstances, such as to prevent terrorism or imminent violence.

The PRESS Act was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in January under suspension of its rules, a procedure generally reserved for noncontroversial, bipartisan legislation, but has been tied up in the Senate Judiciary Committee ever since.

The PRESS Act is what’s referred to as a shield law, a law designed to protect a journalist’s privilege under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Currently, there is no federal shield law, but 40 states have enacted laws with varying degrees of protections for journalists. Both Oregon and California have shield laws in place that are considered to be strong, and California voters passed a proposition in 1980 that elevated these protections to its state constitution.

There are many benefits to enacting the PRESS Act at the federal level. It would establish a stronger and more durable standard for the U.S. Department of Justice, which currently treats journalists according to internal policy, which can change at any time. Under the PRESS Act, the federal government would be expressly prohibited from surveilling journalists by gathering their phone, messaging, or email records and it couldn’t force a journalist to disclose their sources. This protection would also extend to telecommunications companies which may store a journalist’s work product. Also, acknowledging the changing trends in journalism, the act defines “covered journalist” broadly to apply to any person who regularly publishes news or information in the public interest.

While a federal shield law would not supersede state laws, protection on the federal level would send a clear message about the importance of preserving every journalist’s independence, help minimize frivolous lawsuits which news organizations need to defend, and strengthen the relationships between journalists and their sources.

In an age when our political parties disagree about most everything, there seems to be general agreement on the value of the PRESS Act. The House bill was sponsored by Representatives Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) and Kevin Kiley (R-Calif.) and co-sponsored by a group of 18 other members, nine Republicans and nine Democrats. When it was considered in the House, no Republicans or Democrats objected to the act. The Senate version of the bill is co-sponsored by Senators Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), Mike Lee (R-Utah) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.). Other prominent Republicans like Mike Pence, Bob Goodlatte, and Jim Jordan have supported shield legislation in the past.

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson famously wrote: “… were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” It’s time to strengthen the essential role the press plays as a watchdog of our democracy and protect the journalists who work on our behalf to provide the information we need as citizens of a free society.

Paul Westhelle is JPR’s Executive Director.

By ERIK NEUMANN

On a clearing overlooking Siskiyou Mountain Park in Ashland, a navy-blue helicopter is making laps back and forth up the forested hillside. A long cable hangs down and on each pass the helicopter picks up three or four large trees, stripped of their branches. It ferries them down the mountain to a log truck that’s waiting below.

“They’re shooting to get 20 loads per hour. Yesterday they got 174 loads,” says Chris Chambers, the wildfire division chief with Ashland Fire and Rescue. He’s helping coordinate this project where they’re thinning trees on around 500 acres.

In areas of this forest, anywhere from 20-80% of the fir trees are dead, he says. Experts are calling it a decline spiral. Others are calling it “firmageddon.” Chambers worries it’s increasing the number of dead trees that could burn in future wildfires.

“There are many, many neighborhoods right at the bottom of the slope here at Siskiyou Mountain Park. The vast majority of what is dead are right next to those neighborhoods,” he says.

He’s also worried that a large wildfire could permanently change this forest if hotter temperatures driven by climate change make it hard for fir trees to grow back after a fire. He says this thinning work will help soften the blow.

“This forest as we know it is going away. There’s going to be a new forest in the next decade to two decades. And if we don’t stay ahead of it, then we might not have a forest in 20, 30, 40 years,” Chambers says.

The work in the Ashland watershed is aimed at the symptoms of the Douglas fir die-off. But it doesn’t explain why the trees are dying in the first place.

On a hiking trail just outside of Jacksonville, Oregon, Max Bennett is staring up at a collection of fir trees.

“We’ve tagged these trees. There’s a little metal tag on the other side,” Bennett says, peering upwards.

Bennett is a retired Oregon State University extension forester. He’s been researching this fir tree die-off and he co-authored a 2023 paper called Trees on the Edge. As the name of his report suggests, this forest in Jacksonville is an environment that’s right on the edge of where Douglas fir trees can grow. That means it just takes a little change in conditions -- like drought or hotter summers -- to push them over the edge.

“Those two things: not enough rainfall and higher temperatures, particularly in the summer, are what people are talking about much more now as hotter drought. It’s not just drought the way we normally think about it, its hotter drought,” he says.

That combination of above-average temperatures and below-average precipitation is stressing out Douglas fir trees. Bennett suspects these conditions are messing with trees’ ability to pull water up from their roots.

“The hotter it is and the dryer it is, the more pull; the more draw from the atmosphere. It’s like a straw. You’re sucking really hard on that straw, and instead of liquid, you draw in air,” he says. “Think of it as a tree heart attack in a way.”

Southwest Oregon is being especially affected by hot drought conditions because there’s so little water here to begin with.

If hot drought is the first factor driving the die-off, the second one is a little metallic-green bug.

On a hillside midway up Woodrat Mountain in the Applegate Valley, Laura Lowrey swings an ax into the bark of a standing dead Douglas fir tree.

“I usually try to make a square,” she says between swings. “You can peel the bark off these long-dead trees.”

Lowrey is an entomologist for the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. She’s trying to look under the bark to find the squiggly tracks of an insect called the flatheaded fir borer.

Some

Rogue Valley residents say the BLM and the City of Ashland are motivated by timber sales, not forest health or public safety.

She rips off a chunk of bark. Inside are little tunnels where the insect’s larvae have chewed. On the outside, tiny jewels of pitch or sap show where fir borers went in and the tree tried to stop them.

These bugs aren’t inherently bad.

“They are more of the cleanup crew. They’re not tree killers themselves. They’re more like, trees are dying, now they’re helping recycle them, turn them into soil,” Lowrey says.

Fir borers smell stress signals from trees that aren’t healthy, she explains. But now, with so many dead and dying trees in the area, the beetle population has exploded; it’s even overwhelming healthy green trees.

Before Oregon, Lowrey worked in Idaho and the Rocky Mountains where she studied other types of beetle outbreaks. She says they went in cycles: the outbreak would grow, then peak and then crash as predators caught up.

“Here, we don’t get the sense that this outbreak is crashing,” she says.

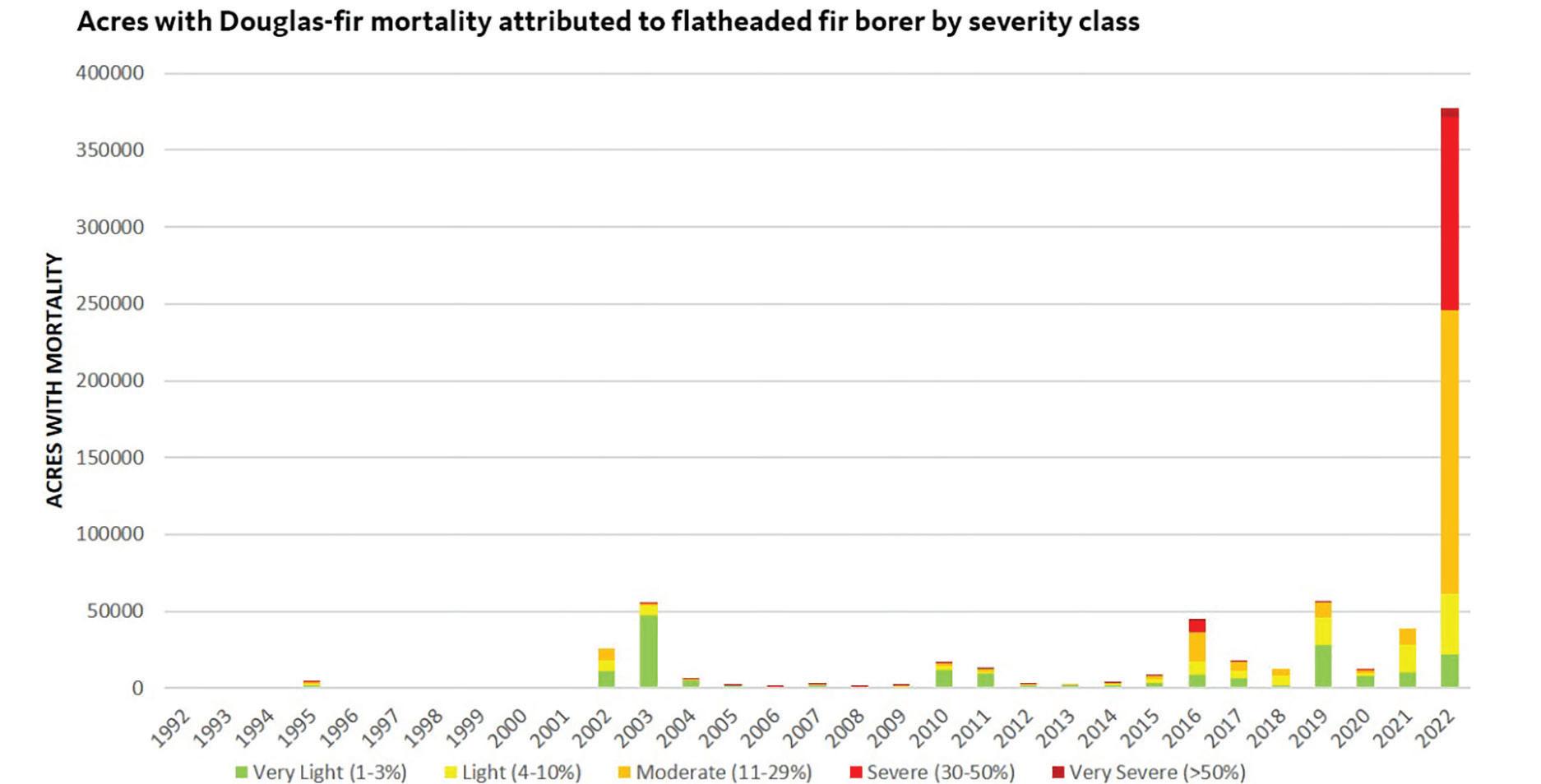

In Trees on the Edge, for which Lowrey contributed aerial survey work, the acres with Douglas fir mortality attributed to the flatheaded fir borer jumps from a high of about 50,000 acres in 2019 to around 375,000 acres in 2022.

Lowrey has done aerial surveys over all types of federal lands across Southern Oregon, scanning out of plane windows for dying firs. She says when she moved here just four years ago there weren’t nearly as many stands of dead trees.

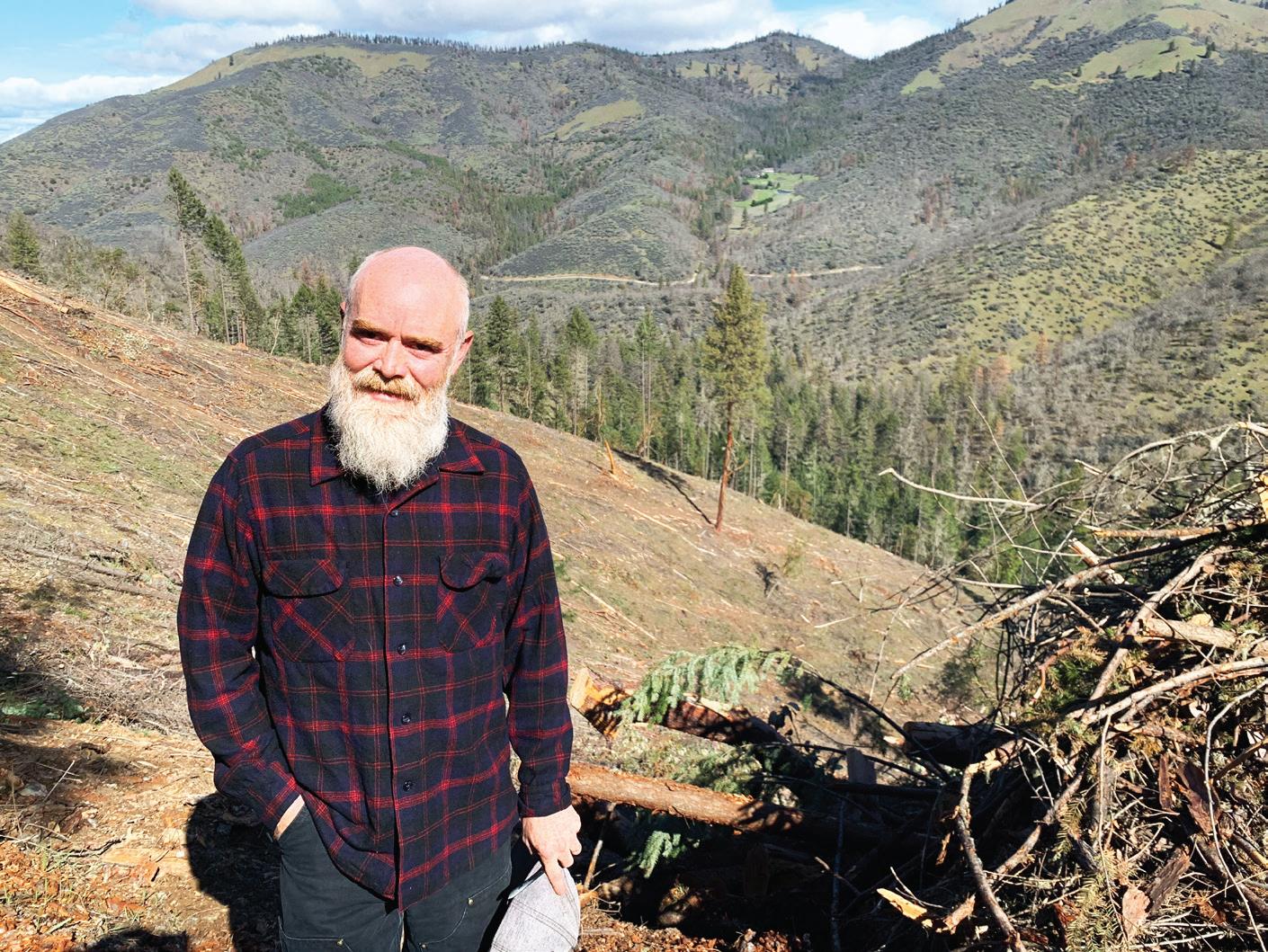

left: Retired Oregon State University

“We’re like, ‘Wow, it’s very fast. It’s real time. Watching the effects of climate change in real time,’ which is an odd feeling to say the least,” she says.

In response to the fir die-off, the BLM is doing thinning on 5,000 of the 876,000 acres managed by the Medford District. Officials say the projects will be meant to protect communities and roads. They’re planning to cut down trees, some of which will be sold as timber. They’ll also do prescribed fire operations. The BLM’s proposed environmental assessment for the project will be released in early summer which the public can comment on.

But some Rogue Valley residents say the BLM and the City of Ashland are motivated by timber sales, not forest health or public safety.

“One of our contentions is what they’re calling hazard tree removal, is starting to look, feel and function much more like unit logging and much more like broadscale clearcutting than clearing hazards adjacent to the road,” says longtime Applegate resident Luke Ruediger.

He argues that these beetle-killed trees would be better left as standing snags for animal habitat like birds that eat the fir borers. And, he says, these same areas have been thinned in the past. He believes aggressive forest management now will make the area more vulnerable to drought and beetle mortality in the future.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that right now the areas being targeted for salvage logging are also some of the areas that have been the most heavily managed by the BLM, by the City of Ashland, and by the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest,” Ruediger says.

A better way to protect communities, he argues, is to help residents who live around these forests create defensible space and take steps to harden their homes from the risks of wildfires.

Five miles north, in Central Point, Bryan Reatini is standing in a big green grid of Douglas fir trees in the middle of a farm field. He examines a tag on one of the trees.

“This block is “Oregon Cascade low,” which makes sense. This is around where we are at locally,” he says.

Reatini is a geneticist with the Forest Service and he’s at JH Stone Nursery. The trees here are examples of Douglas fir that have been cultivated from different seed sources across the species’ range. The grid is part of a project to study climate adaptation so that land managers across the West Coast can help forests withstand future climate scenarios.

He walks into one section where the firs are not looking great. They’re scraggly and stunted. Some have gone from green to orange.

“Washington coast,” he says. “A very different environment. And as you can see, they’re not doing very well here, are they?”

There’s wide genetic diversity, even within a single species like Doug fir, he explains. Fir trees that are adapted to the Washington State coast are not suited to Southern Oregon. But others from warmer climates might grow better here as temperatures increase.

“By transferring seeds from those environments that have adapted to those conditions, to where those conditions exist now presently, we can essentially help trees track climate change,” he says.

The steps they’re taking are conservative. They might plant seedlings just a thousand feet higher in elevation from their original source. Researchers are trying to mimic how trees would naturally shift, he says, if climate change wasn’t happening so fast.

A graph published in Trees on the Edge: “Acres with Douglas-fir mortality attributed to flatheaded fir borer by severity class. The estimate for the number of acres affected is based on aerial sketchmaps that show the general areas Douglas-fir dieback has occurred. It does not necessarily mean that all or even most of the Douglas-fir trees in those areas have been killed. Instead, the estimate represents a mosaic of trees that were recently killed and living trees. Aerial survey data are most appropriate for monitoring damage and mortality trends at a watershed scale. They do not provide precise estimates of the number of trees killed or the area affected.”

LAURA LOWREY VIA MAX BENNETT/U.S. FOREST SERVICE, OSU EXTENSION SERVICE

The bigger goal for Reatini’s team is to help land managers plan ahead when reforesting places like the hills around Ashland or the Applegate Valley.

“I think we have our work cut out for us for sure. I think we’re behind and things like the Douglas fir decline spiral are examples of that. But I am optimistic that we are going to be able to maintain healthy forest populations. It’s going to require a lot of thinking and a lot of effort and a lot of innovation but yes, I absolutely think we can accomplish that goal,” he says.

In the years ahead, he says, they expect to see changes to tree species’ ranges. Douglas fir trees in Southern Oregon are just one example where the effects of climate change will slowly be revealed.

Erik Neumann is JPR’s news director. He earned a master’s degree from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and joined JPR as a reporter in 2019 after working at NPR member station KUER in Salt Lake City.

“I had never used the bus and had no idea where to start. RVTD’s Travel Trainer showed me the way—from setting up my Umo account to understanding the routes and transfers.” — Gene

Getting there together since 1975.

By JAMIE HALE

Forged by an explosive volcanic eruption in southwest Oregon, Table Rocks took their shape over millions of years, carved by the steady waters of the Rogue River, which now flows more than 800 feet below the rim.

Every autumn, as temperatures drop and rainclouds return, acorns fall from oak trees that surround the pair of flattopped mesas. The return of the acorns precedes the return of Native peoples, who gather the bitter nuts, grind them up and turn them into a nutritious mush – a practice that goes back millennia.

In recent years, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians have created opportunities for members to reforge connections to the lands their ancestors knew intimately. Their removal from this place in 1856, an event some historians call the Rogue River Trail of Tears, has become a road map that many tribal members are retracing into the future.

In the fall, the two tribes come together to gather acorns at an event called Acorn Camp in southwest Oregon. This June, they will host their first joint Camas Camp, where they will harvest camas lilies and other spring plants. And, just after Memorial Day Weekend, the Siletz tribe will host its annual Run to the Rogue marathon, a 216-mile relay down the coastline and up the Rogue River.

Greg Archuleta, cultural policy analyst with the Grand Ronde tribe, said the current focus is on refamiliarizing tribal members with the places of their ancestors, as well as passing down practices that have survived for generations.

“Our primary focus right now is really to get tribal members out on the landscape,” Archuleta said. “It’s all about presence.”

That presence has also created a new sense of home for many Indigenous families who have spent generations living elsewhere – on reservations far away, in bigger cities or out of the region altogether.

“It’s kind of like meeting a relative that you’ve heard about for a long time but never had a chance to meet,” Robert Kentta, tribal council member for the Siletz tribe, said of returning to southwest Oregon. “That connection is still there.”

For tribal members, revisiting Table Rocks isn’t always easy. There is trauma there, buried in the ground, filling the recesses of the hard, volcanic rock.

At the start of the 19th century, the region was home to the Takelma, Shastan and Athabaskan peoples who had lived in the area for untold generations. But it was also becoming home to a growing number of non-Indigenous settlers. The first to arrive, French fur trappers called the Indigenous people in the region “rogues,” a derogatory nickname that was often used as a justification for violence, according to historian Gray Whaley in “Oregon and the Collapse of Illahee.”

When gold miners showed up in 1849, they treated the “rogues” as a threat, and waged an open campaign of extermination, according to historical documents. That first year, a militia killed 60 Indigenous people after allegedly finding an

There is trauma there, buried in the ground, filling the recesses of the hard, volcanic rock.

Indigenous man “secreted” in a white woman’s home, according to Whaley. Tribal historians say their ancestors suffered violence both casual and organized, by both local militias and the U.S. Army.

“Pretty much the whole philosophy was to exterminate the Indians,” Archuleta said. “It was something that was pretty extreme during that time.”

In 1853, many of the Rogue River peoples gathered at Table Rocks to sign a treaty with the U.S. government in which they agreed to cede the lands in exchange for a permanent reservation, where they might be safe. Violence from militias continued during the treaty negotiations, an attempt to derail the process, tribal historians said. After signing the treaty, the people were removed to a temporary reservation at Table Rocks, where hardships continued.

Being forced to remain in one location kept the Rogue River peoples from their traditionally mobile practices of gathering, hunting and creating seasonal homes, resulting in starvation in addition to disease and continued attacks, according to historians. Those who left the reservation were often hunted down and killed by local militias.

The situation came to a head in 1855, when the deaths of two packers were blamed on Indigenous men. A white militia seeking to avenge the deaths left under the cover of darkness to the

Table Rock Reservation, where they killed about 25 people sleeping by the banks of the river, according to historical accounts. As they left, the militiamen killed another 50 to 80 Indigenous people in the area, most of whom were women and children.

The violence was particularly brutal. One witness recalled seeing two elderly women who were bashed to death with clubs and a child who was “taken by the heels and its brains dashed out against a tree.” According to Whaley, one attacker later said that while the extermination made him feel bad, “the understanding was that [the Indians] were all to be killed. So we did that work.”

In response to the attacks, a group of Indigenous leaders retaliated with raids on homesteads and settlements. In less than a year, roughly 250 Indigenous people were killed, along with some 50 non-Indigenous soldiers and 44 civilians, according to historical records.

Tribal members have been holding those horrific memories for generations.

“We have these historical legal traumas as well as physical and emotional and spiritual traumas,” which metastasized into issues like substance abuse and domestic violence, Kentta said. “We often hear about elders who don’t want to be hugged.”

Kentta’s great-grandfather was 7 or 8 years old when his people were removed from their homelands. After the boy’s father was killed, his mother left him with his paternal grandparents while she left to find her family. She never returned. The

boy left southwest Oregon as an orphan.

In February 1856, amid the fighting, U.S. soldiers led by Bureau of Indian Affairs agent George Ambrose moved 325 people by foot from the Table Rocks Reservation to a place that would become the Grand Ronde Reservation, 263 miles away. The 33-day journey went over mountains and along rivers, north through the Willamette Valley, roughly following the future Interstate 5 corridor, and up into the Coast Range.

Aside from the rugged environment, winter weather and generally poor conditions, the captive travelers also faced the constant threat of violence from militiamen stalking the group. Ambrose, who apprehended one man, eventually dissuaded militias from murdering members of the group, though casualties still mounted. According to Ambrose’s journal, the journey saw eight deaths among the captives – as well as eight births.

The Rogue River people who chose to stay and fight against removal held out until that summer, eventually surrendering after brutal losses. The surviving holdouts were taken to both the Grand Ronde and Siletz/Coast reservations, according to tribal historians.

Despite generations of oppression and the attempted genocide of a people, leaders in the Grand Ronde and Siletz tribes said they prefer a frame of resilience.

“There’s pride in the resilience of our ancestors,” Kentta said. “And some of it’s probably a stroke of luck that they didn’t get swept away.”

Travis

and Cultural Center

Ronde, stands outside a plankhouse named achaf-hammi.

Only in the past few decades have the tribes directly faced the past, seeking healing through conversation, support and returning to places of tragedy.

In the Grand Ronde Community, just a mile down the road from the tribe’s Spirit Mountain Casino, is a quiet place: the Uyxat Powwow Grounds, home to an outdoor arena lined with turf and a large ceremonial plankhouse named achaf-hammi.

Outside the plankhouse is a tall gray pole carved from a single western redcedar tree, marking this place as the end of the Rogue River Trail of Tears.

Travis Stewart, director of the tribe’s Chachalu Museum and Cultural Center, created the pole with a carving group for the plankhouse’s dedication in 2010. Standing at the base of the roughly 26-foot pole, he pointed out the headman at the top and coyote running down either side. The length of the pole is decorated with five tiers of faces representing five treaties signed by the tribe, he said, each face crying a stream of tears.

Those tears are not just from grief, Stewart explained, “they’re bringing their generational knowledge to this place and it’s coming out into the ground here.”

Traditional practices like carving and basket weaving, as well as harvesting plants for food and medicine, are now representations of the resiliency of Indigenous people throughout generations of hardship, Stewart said. The pole, the plankhouse, and events like Acorn Camp and Camas Camp are proof that this generational knowledge still exists.

“There was a lot of effort and sacrifice on behalf of those old people that made tough decisions ultimately in order to preserve that (knowledge),” Stewart said. “It’s a responsibility of ours to continue that.”

After the removal from southwest Oregon, the Grand Ronde and Siletz reservations became home to more Indigenous survivors, people from neighboring lands who spoke different languages, ate different food and practiced their own customs. At first, most people kept to their own (going so far as to organize themselves geographically), according to tribal historians, but as the U.S. Government shrank the reservations – Siletz from 1.1 million acres to nearly 17,000 today, Grand Ronde from 61,000 acres to 11,500 today – the people came together, creating new tribal communities.

“We’ve made our footprint here,” said Chris Mercier, vice chair of the Grand Ronde tribal council. “It wasn’t under the best circumstances that the tribal people were ushered up here, but I like the fact that we’ve established this community, one that’s been existing for over 150 years now.”

Of the 5,700 enrolled members of the Grand Ronde tribe, only about 1,200 today live in or around Grand Ronde, Mercier said. But those who do enjoy a tight-knit community, where the past, present and future of the tribe seem to collide at every turn.

For several generations after removal, people didn’t want to directly confront the traumas of the past, tribal leaders said. That was in large part due to ongoing struggles, including being forced to send their children to boarding schools, which were rampant with abuse, and the 1954 termination of western Oregon tribes, during which the government severed all federal support.

Only in the past few decades have the tribes directly faced the past, they said, seeking healing through conversation, support and returning to places of tragedy.

In the mid 1990s, the Siletz tribe started Run to the Rogue, in which tribal members run and walk their way down the coastline, then up the Rogue River to a place called Oak Flat, about 50 miles from Table Rocks, where in 1856 several bands of the tribe’s ancestors surrendered to the U.S. Army.

Buddy Lane, cultural resources manager for the tribe, has been organizing the event since 2012. He said runners of all abilities participate to different degrees. The tribe’s youngest members take the first mile in Siletz, and the elders take the final mile to Oak Flat. The strongest runners take the hardest miles along U.S. 101 at Cape Perpetua, a stretch Lane has done before.

“The trek is a lot easier than it was for our ancestors,” Lane said.

Many tribal members follow runners along the route, supporting their effort and finding ways to reconnect with their roots, he said. Some pay visits to the lands where their families once lived, or gather in parks, staying up late into the night as runners come and go.

“It’s an emotionally charged event,” Lane said. “We’re not celebrating something, but we’re remembering things and making sure those folks with stories are not forgotten.”

The relay, along with the Acorn Camp and Camas Camp, represents a new generation of tribal members who are actively connecting with their past through new experiences in the present, they said. The fact that these homecoming events all include a return trip back home – to Siletz, Grand Ronde and other places – underlines a complex question: What is “home” to a displaced people?

For Kentta, who has lived his whole life in Siletz and whose ancestors are from the Applegate Valley as well as Finland, southwest Oregon is like a home away from home.

“Whenever I’m in the Rogue Valley it’s kind of an emotional feeling of like a connection, even though I didn’t grow up there,” he said. “It’s an ancestral home rather than my current home.”

Archuleta grew up primarily in east Portland and traces his ancestry to the Willamette Tumwater, Clackamas Chinook, Cascades Chinook, Santiam Kalapooia, Shasta and Rogue River peoples. He has family ties to the Warm Springs, Yakama, Siletz and Klamath tribes. “Pretty much all of western Oregon” is home, he said.

“It’s really each person, each family’s perspective of how they see it,” he said.

While many other places may be home, for these sister tribes, there’s still something special about the land in southwest Oregon. Table Rocks has always been an important place,

a site of harvest and ritual, as well as the setting of creation stories, tribal historians said. Today, for non-Indigenous people, Lower Table Rock and Upper Table Rock are primarily places for recreation and conservation, managed by the Bureau of Land Management and environmental nonprofit The Nature Conservancy.

The area is home to more than 340 species of plants and 70 animals, including the tiny dwarf-wooly meadowfoam wildflower, which grows nowhere else in the world, as well as a threatened species of fairy shrimp, which hatches in vernal pools that form in the rocky soil every winter.

For the descendants of the Takelma, Shastan and Athabaskan people, it is also once again becoming a place to build community, while communing with a landscape that holds a rich and complicated history.

“Some of these activities that we’re doing is to bring back healing, bring back families together, and to connect to the landscape, and to continue that stewardship and responsibility to the land,” Archuleta said. “Just being able to fish in a place where your ancestor fished or gathered … it’s restoring what’s always been there, and what’s always been in our hearts and minds.”

Beach Creek is a neotraditional neighborhood of 55 smartly designed view homes focused on e cient living, wise resource use, and a low carbon footprint. For more information or to schedule a tour, please visit www.Kda-homes.com or call us at 541-944-7730.

JON HAMILTON

Aflexible film bristling with tiny sensors could make surgery safer for patients with a brain tumor or severe epilepsy.

The experimental film, which looks like Saran wrap, rests on the brain’s surface and detects the electrical activity of nerve cells below. It’s designed to help surgeons remove diseased tissue while preserving important functions like language and memory.

“This will enable us to do a better job,” says Dr. Ahmed Raslan, a neurosurgeon at Oregon Health and Science University who helped develop the film.

The technology is similar in concept to sensor grids already used in brain surgery. But the resolution is 100 times higher, says Shadi Dayeh, an engineer at the University of California, San Diego, who is leading the development effort.

“Imagine that you’re looking on a clear night at the moon,” Dayeh says, “then imagine [looking through] a telescope.”

In addition to aiding surgery, the film should offer researchers a much clearer view of the neural activity responsible for functions including movement, speech, sensation, and even thought.

“We have these complex circuits in our brains,” says John Ngai, who directs the BRAIN Initiative at the National Institutes of Health, which has funded much of the film’s development. “This will give us a better understanding of how they work.”

The film is intended to improve a process called functional brain mapping, which is often used when a person needs surgery to remove a brain tumor or tissue causing severe epileptic seizures.

During an operation, surgeons place a grid of sensors on the surface of an awake patient’s brain, taking care not to tear the delicate film. Then they ask the patient to do tasks, like counting or moving a finger.

Some of the tasks may be specific to a particular patient.

“If somebody is a mathematician, we’ll give them a math formula,” Raslan says. “If somebody is a painter, we’ll give them what’s called a visual cognition task.”

The sensors show which brain areas become active during each activity. But the borders of these areas tend to be irregular, Raslan says.

“It’s like a shoreline,” he says, “it zigzags and it curves around.”

The accuracy of a brain map depends on the number of sensors used.

“The clinical grid we use now uses one point of recording every one centimeter,” Raslan says. “The new grid uses at least 100 points.”

That’s possible because each sensor on the new grid is “a fraction of the diameter of the human hair,” Dayeh says. And the grid

itself is bonded to a plastic film so thin and flexible that it conforms to every contour of the brain’s surface.

The device works well in animals. And in May, the FDA approved it for testing in people.

Dayeh and Raslan, who both hold a financial interest in the device, say the team is already working on a wireless version that could be implanted for up to 30 days. That would allow people with severe epilepsy to be monitored for seizures at home instead of in the hospital.

Ultimately, the researchers hope to use this diagnostic tool as a brain-computer interface for people who are unable to communicate or move.

That would allow them to “transduce their thoughts into actions,” Dayeh says.

Scientists have already created this sort of brain computer interface using sensors implanted deep in the brain. But a grid on the brain’s surface would be safer, and could potentially detect the activity of many more neurons.

Daye’s research is part of the federal BRAIN Initiative, which was launched a decade ago to develop tools that would reveal the inner workings of the human brain.

The new grid is one of the tools, Ngai says. But it also promises to improve care for people with brain disorders.

“Ultimately, the goal was to develop better ways of treating human beings,” Ngai says, “and I think this gives us a pretty big stride toward that goal.

Future strides may come more slowly. This year, Congress cut BRAIN Initiative funding by about 40 percent.

Even so, Ngai says, the new sensor grid and its wireless counterpart show just how far the field has come.

A decade ago, Ngai says, some of the nation’s top electrical engineers and computer scientists said there was no way devices like these would work.

“You look now,” he says, “and it’s being done.”

Jon Hamilton is a correspondent for NPR’s Science Desk. Currently he focuses on neuroscience and health risks.

• Hundreds of classes, take all you want

• Social events, discussion groups, activities

• All-inclusive annual member fee of $150

• Visit dozens of exhibits from OLLI faculty, SOU, and community partners

• Preview 100+ OLLI fall courses and activities

• Enjoy free refreshments and enter to win valuable door prizes

ANNA KING

On a warm day in Centralia, Washington, south of Olympia, Alan Woods is standing surrounded by his 90 million bees.

“So, we’re in the middle of the bee field,” he said. “You look around, and you can see bees everywhere.”

A halo of bees buzzes around his head; he’s not wearing a protective veil.

Woods, who heads the Washington State Beekeepers Association, is what’s called a sideliner beekeeper, or a small operator. It can be a tough business. Woods said beekeepers lose about 30 percent of their hives per year now, and he often comforts beekeepers who’ve lost hives. He’s also a Christian pastor, maybe even a bee-pastor.

“I talk to a lot of people about God and bees at the same time,” Woods said with a chuckle.

Commercial beekeepers around the United States rent more than 2 million hives to pollinate almond crops in California. Hundreds of thousands of those hives are trucked from the greater Northwest.

However, there’s a problem this year. The pandemic, international shipping problems and over-planting have led to a glut of nuts in California, and almond growers there are in bad economic shape. Many of them are reducing their top expenses –like bees. That’s an issue for the beekeepers of the Northwest who rely on the income – and for the bees themselves.

Brandon Hopkins, a Washington State University honeybee researcher, keeps a close eye on the industry.

Hopkins said that after winter, bees wake up weak with diminished numbers in each colony. Pollinating almonds nourishes them with an abundant flow of nectar and pollen. He said the bees that are sent to California return home stronger and often double their colony numbers, splitting into new colonies.

Hopkins said this year, fewer colonies went to California. Some almond orchardists couldn’t afford the insects; others tried to scrape by with fewer bees than normal.

“If a half million colonies don’t go to almonds, then you have a half million colonies that sort of miss that really early spring buildup,” Hopkins said. “And so you have … fewer colonies from which you can do those early spring splits and things like that.”

He said those half million colonies mean, ultimately, a million colonies missing in the commercial bee ecosystem – that’s a $100 million hit to the beekeeping industry, and that’s not good news for fruit growers in the Northwest.

“I think what’s not so well known is how much the almond industry has really supported all the other industries that depend on honeybees for pollination,” Hopkins said. That includes Washington and Oregon apples, cherries and vegetable crops.

Meanwhile, commercial beekeepers have to keep an eye on their economic health. This year, Bud Wilhelm, who runs a large commercial beekeeping operation in Royal City, Washington, didn’t bring all of his 8,000 colonies to California, the way he usually would. It’s expensive and a big risk — shipping costs, feed for the bees, hotels for his workers.

“It was wise on our part to hold back some hives,” Wilhelm said. He wasn’t sure that he would get paid. “Especially, as some of these individuals I thought would pay, who are in a strong cash position, and who know me personally, you know, they are struggling to find the money to get us paid for those services.”

Wilhelm said bees are a sensor of things across the wider agricultural ecosystem. Many in ag are struggling now, he said. For the first time in his 15 years of beekeeping business, Wilhelm is seeing growers needing payment plans to cover his pollination services. He said farmers are tough.

“Even through all that strength and that hope and faith that these farmers have, they get to a point where they just financially can’t do it,” he said.

Wilhelm said for almonds and bees, he hopes for a brighter day.

Anna King calls Richland, Washington home and loves unearthing great stories about people in the Northwest. She reports for the Northwest News Network from a studio at Washington State University, Tri-Cities. She covers the Mid-Columbia region, from nuclear reactors to Mexican rodeos.

Telegraph Quartet

Friday, September 20 v 7:30pm

Quartetto di Cremona

Saturday, October 26 v 3pm

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Winds & Piano

Friday, November 15 v 7:30pm

Israeli Chamber Project

Wednesday, December 4 v 7:30pm

Isidore Quartet

Wednesday, January 8 v 7:30pm

Ulysses Quartet

Friday, January 24 v 7:30pm

AGAVE with Reginald Mobley, countertenor

Sunday, February 9 v 3pm

by request: tenThing

By Request: Underwritten by Dr. Margaret R. Evans & Anonymous

Wednesday, February 26 v 7:30pm

Marmen Quartet

Saturday, March 8 v 3pm

Leonkoro Quartet

Friday, March 21 v 7:30pm

Trio Zimbalist

Saturday, April 12 v 3pm

ALEJANDRO FIGUEROA

The coastal seafood butchery program also serves a broader economic purpose: to bolster the seafood workforce as industry groups look to keep more Oregon-caught fish local.

Patrick Clarke is outside, setting up a big pot of broth with Cajun spices over a propane flame. He’s already got a grill running and has set out the corn, potatoes, sausage and pink shrimp.

He leans down to a chest cooler filled with ice and pulls out a live Dungeness crab.

“This is the money maker right here on the Oregon coast,” he says. “The crab fishery is probably the most valuable fishery that we have in Oregon. It’s a billion-dollar industry. And a lot of it comes straight into Newport right down the road here.”

Clarke is the culinary director at Siletz Valley School — a K-12 charter school serving the Siletz Indian Reservation about a 20-minute drive outside Newport — and teaches a handful of cooking courses there. His school is one of six coastal high schools participating in a pilot seafood butchery program that launched in April with the intent to teach students how to clean and cut all sorts of fish and crustaceans found on the Oregon coast. They also learn how to cook seafood, and, perhaps more significantly, they learn about its relationship to communities up and down the coast.

Clarke, a nearly 20-year veteran of the restaurant industry, said filleting is a dying art around the coast and much of the Pacific Northwest.

“You could run into a bunch of these high-end restaurants, I bet you six out of 10, if you ask one of their head chefs to fillet a salmon and pin bone it, he would get very nervous at that point,” he says. “Because they don’t do it anymore.”

The coastal seafood butchery program also serves a broader economic purpose: to bolster the seafood workforce as industry groups look to keep more Oregon-caught fish local. But first, the hands-on part. On the menu for the day: gumbo, with crab boil and shrimp cakes and a side of lamb chops.

Clarke puts two students in charge of grilling the sausages and the lamb chops. Another small group joins him to split the crabs and boil the legs. They begin doing it carefully by hand and discarding the guts into a trash bin.

Dean Smith, a junior, says it was easy to get the hang of it.

“I pretty much understand it, all I needed was to see it one time,” he says. “I just wanted to take this class so I could learn how to cook for myself when I’m older.”

Another student, Landynn Larson, a sophomore, points out an easier way to do it. He grabs one of the crabs firmly by the legs and with one single motion jabs the head of the crab against the edge of a metal table, cleanly separating the head from the legs.

“There you go, you take his whole head off. That was pretty good. I’ve never done it that way,” Clarke says, praising Larson.

Larson says he learned that from his grandfather, who’s taught him how to clean and cut fish and to hunt. Larson plans to go to college to study architecture, but can see himself working at the docks and restaurants filleting fish.

“I can get a degree for that and work around here cutting up fish and cooking and all that for boats and for people, businesses,” Larson says. “That’d be a cool job to have, kind of a back up plan.”

Clarke says it’s hard to come by skilled filleters. That’s partly because it’s more cost-efficient for restaurants to order portioned fish rather than paying someone to clean and cut it. Plus many of the seafood processing plants along the coast have shut down or consolidated over the years. Most of them are now concentrated around Newport and Astoria in the north and Charleston on the southern coast.

The Oregon coastline spans over 300 miles, and it’s bountiful with fish like lingcod, rockfish, Chinook salmon and Dungeness crabs.

But 90% of the seafood sold and consumed on the Oregon coast is imported from domestic or international markets while most of what’s caught is exported. Yet locally, there’s a growing demand for more fish and crab caught on the Oregon coast, according to Maggie Michaels, the lead for the High School Seafood Butchery program for the Oregon Ocean Cluster Initiative — a group supporting efforts to keep more local seafood.

Kelly Barnett cleans and organizes equipment in his trawler boat after a day of fishing off the coast in Garibaldi, Ore., May 23, 2024. Barnett is a fishmonger on the Oregon coast that catches, fillets and sell fish to local customers and visitors.

“Schools want more of it, institutions want more of it. People going to the grocery stores want more of it,” Michaels says.

Oregon’s “blue economy” — the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth — is driven by its commercial fishing industry. Much of it is also supported by tourism. According to the Oregon Ocean Cluster Initiative’s latest figures, visitors to the Oregon coast spend about $800 million on seafood and other food services per year, though much of that money isn’t spent on locally caught seafood.

Michaels says the group is looking to change that, and as more people ask where their seafood is coming from, communities need a workforce that matches that pent-up demand.

“We’re going to need more people to fillet because across the continuum of the seafood industry and seafaring industry we have a graying out,” Michaels says. “The folks who have these skills are getting older.”

Kelly “the Blade” Barnett knows just how valuable those skills are.

“You need somebody who can get all the meat off the fish because you don’t wanna waste it. That fish has sacrificed himself for us to eat. And to waste it is a crime,” he says.

Barnett is a fishmonger, he also catches his own fish and sells it at his market, the Spot, at the Port of Garibaldi.

After a day of fishing, he’s getting caught up on cleaning and smoking a batch of salmon ahead of Memorial Day weekend. He’s been filleting fish for nearly four decades. As for his nickname, he says there was a charter boat operator several years ago that used to put on a P.T. Barnum voice to introduce him whenever he showed up.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, children of all ages, Siggi-G charters proudly presents Kelly ‘the Blade,’” he says. “And that name stuck.”

He’s seen things change.

“There was a fish plant at the end of the road here. And there were 12 to 20 skilled filleters there that worked full-time. And they would lend their talents to cutting the sports people’s fish,” he says. “And now there’s maybe two or three of us that do it commercially [in Garibaldi].”

He remembers when the filleters in training at the nowclosed plants used to practice on the fish that were too small to be commercially viable.

“Then we would take that — you know, 10 to 12 of us — up to the bar and give it to the bartender,” he says. “They would cook it up in their fish fryer and serve it to everybody in the bar. And so everybody enjoyed.”

He says what’s lost when the talent disappears from the coast is a sense of community and the ability to prepare and share a meal with someone. But he doesn’t let that keep him down. He’s helped train some of the high schoolers in the butchery program and sees similar efforts as a continuation of his community.

“They genuinely want that knowledge,” he says. “They made me feel really good that I had a skill to share that not everybody’s gonna get, but once you get it, you’ve got it for life.”

Back at Siletz, students are done boiling the crab legs and grilling the lamb chops, and are lining up for a plate. Students and teachers from other classes are queuing up for a bite too.

Some distance away, Clarke looks back and says seeing his students sharing the food they’ve made is one of the moments he most looks forward to.

“I don’t know how important, just that scene right there is,” he says.

He knows not all high schoolers will want to go into seafood. But at least they’ve done it and they learned something.

“[Cooking] is a gigantic part of life. It’s relaxing. It’s fun to do. You can impress dates with it,” he says. ”You create social dynamics by just sitting at the dinner table and having everybody sit down and share a meal.”

He knows how uncertain life can be as a teenager, and maybe, he says, he’ll run into an old face down the line.

“I hope I have students that come back and maybe they’ll get a James Beard nomination,” he says. “Or maybe I’ll just see them 10 years down the road and they’ll be like, ‘Pat, I’m cooking, I’m a chef now,’ and I’ll be like, ‘What? No kidding.’”

Copyright 2024 Oregon Public Broadcasting

Alejandro Figueroa is a reporter and producer covering food production and agriculture through a climate change lens for OPB.

If you’d asked my children when they were growing up, “How many are in your family?” They’d have said, “Five: a Mom, a Dad, two daughters and the Rogue River.”

And they’d have been right. For fifty years I have had the privilege of living on the banks of the Rogue. This ancient river has served at times as sibling, friend, nurturer, challenger and, always, as teacher. Two hundred times I have been a witness, watching and listening as the season changes.

Autumn announces its arrival when the vine maple turns a gaudy shade of almost fuchsia, its long tendrils graceful, floating on invisible breezes.

Then---it’s the same every year---my windows wide open to feel the welcome downturn in temperature, I hear a singular sound. It’s the briefest of splashes, quick, over in a second. It’s a salmon using her tail to dig a hole in the gravel, so she can lay her eggs.

I call my family to tell them she has come home.

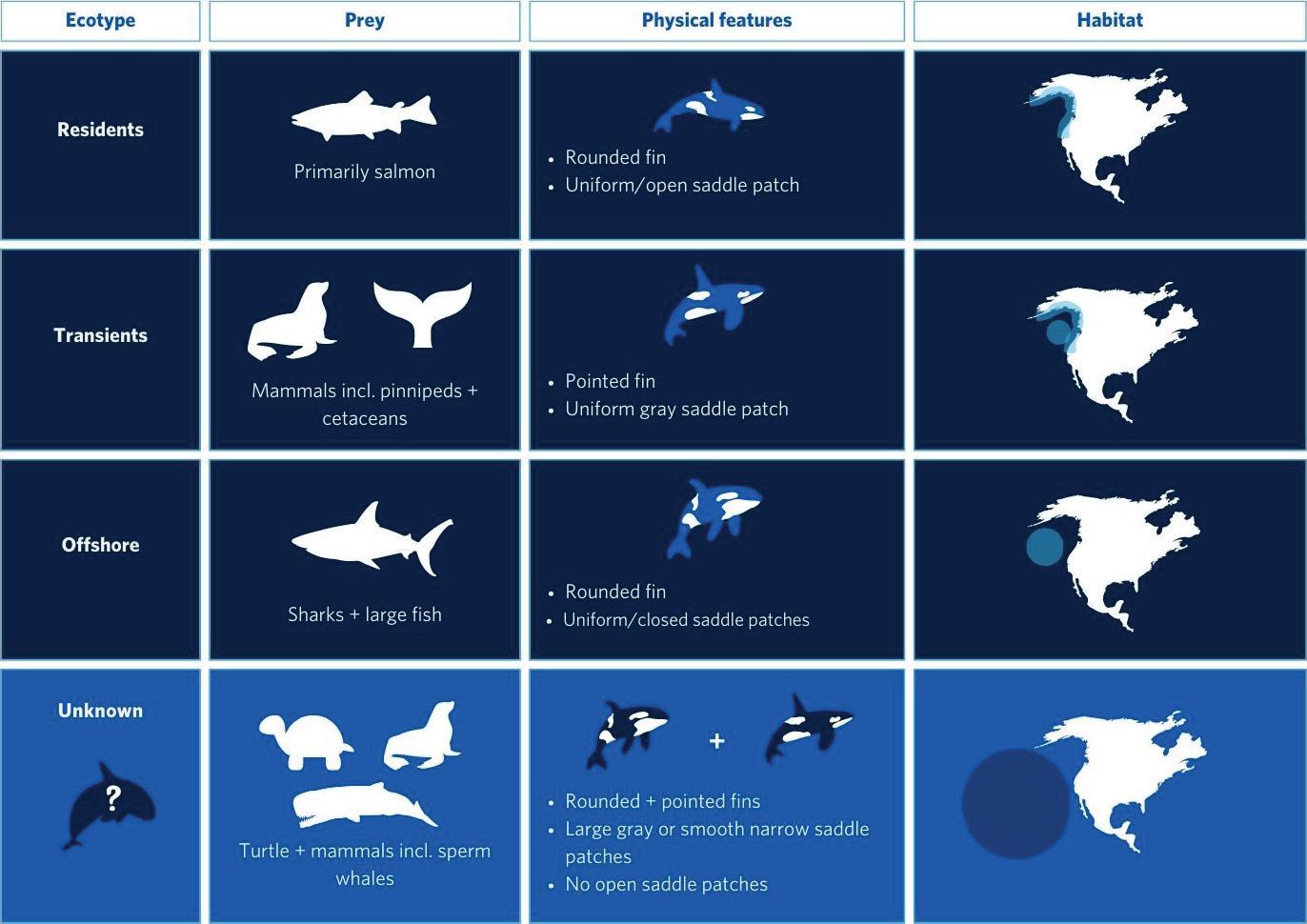

The salmon are coming back! I grab binoculars and run outside to see the arrival of the first of the spawners. This fish spends her youth in the river, where she survives the fisherman’s hook. Then she heads to the salt water of the ocean for a few years, where she survives the orcas, seals and sea lions. Returning home, she’s old, her body scarred and mottled from her long journey. She has traveled an amazing hundred miles from the sea to lay her eggs close to where she was born. I’m a mother, too. I think I understand her perseverance. I’m old now, too, I think I understand her sacrifice.

I stare at her unblinking eyes. Does she see me watching her? Is she looking back at me?

She has done all she can, and so her life ends.

In winter, with the distraction of the vivid leaves fallen from the trees, and many of the birds away---migrated to warmer climes---the river comes fully into view. Besides bare branches, it’s the only thing to see outside my window.

Wider and wilder than in other seasons, the river roars with power, its sound deafening, drowning conversation. Its level going up and up, closer and closer. The river swallows rain, devours delicate snowflakes. Grey in the daylight, black at night. I can only surrender to its threatening presence. The Rogue, true to its name, promises no fairness.

Spring brings the play of otters, a quick glimpse of beavers, and the riot of color like the vibrant hues of newborn leaves and the primary colors of wildflowers that compete with the river for attention. My eyes don’t know where to look first. But, infused with mountain snow melt that clarifies its riffles and rapids, the river is at its most playful in spring, its sound a child’s song.

Fox dart across the meadow, turkeys peck and strut, and deer give birth under the big pine, then drink from the river and, sometimes, swim across to the other side.

I know summer is here when the oak trees, at last, unfurl their baby leaves. The fragile forms are almost translucent, their color a holy green, hinting at some newer world.

These dry months of summer mean the river’s depth is shallow, its voice hushed, allowing the squawking variety of ducks and the chirping, singing, trilling of birds to dominate with their rowdy cacophony.

Bejeweled by the sun, the river’s summer face is so bright it should come with a warning: “The surgeon general has determined that glimpsing this river may damage your eyesight. Do so at your own risk.” But glimpse I must, when my soul longs for light, as it almost always does. When I hope for insight, as I almost always do.

Summer nights, when the sun finally falls behind the Table Rocks, the river becomes a quiet mirror, reflecting light from stars that ceased to exist eons ago.

Always, the river abides.

There are no words to describe the joy of being a witness to this cycle, to notice how each season is the same and yet unique from any that has gone before.

But also, through my times of despair, the loss and tragedy that my life---that every human life---experiences, the Rogue River maintains its constancy. It flows, as it has for millennia, from its source high up near Crater Lake to its Pacific Ocean destination. Its rhythm changes with the seasons, its colors morph from blue to green to grey to black, but its path is lucid, its timeless purpose unchanged.

FM Transmitters provide extended regional service. (KSOR, 90.1FM is JPR’s strongest transmitter and provides coverage throughout the Rogue Valley.)

FM Translators provide low-powered local service.

Monday through Friday..

5:00am Morning Edition

8:00am First Concert

12:00pm Siskiyou Music Hall

2:00pm Performance Today

4:00pm All Things Considered

6:30pm The Daily

7:00pm Exploring Music

8:00pm State Farm Music Hall

Saturday..

5:00am Weekend Edition

8:00am First Concert

10:00am Metropolitan Opera

2:00pm Played in Oregon

3:00pm The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

KSOR 90.1 FM ASHLAND

KSRG 88.3 FM ASHLAND

Big Bend 91.3 FM Brookings 101.7 FM Burney 90.9 FM Camas Valley 88.7 FM Canyonville 91.9 FM Cave Junction 89.5 FM

Chiloquin 91.7 FM

KSRS 91.5 FM ROSEBURG

KNYR 91.3 FM YREKA

KOOZ 94.1 FM

4:00pm All Things Considered

5:00pm New York Philharmonic

7:00pm State Farm Music Hall

Sunday..

5:00am Weekend Edition

9:00am Millennium of Music

10:00am Sunday Baroque

12:00pm American Landscapes

1:00pm Fiesta!

2:00pm Performance Today Weekend

4:00pm All Things Considered

5:00pm Chicago Symphony Orchestra

7:00pm State Farm Music Hall

MYRTLE POINT/COOS BAY

Coquille 88.1 FM Coos Bay 90.5 FM / 89.1 FM Etna / Ft. Jones 91.1 FM Gasquet 89.1 FM Gold Beach 91.5 FM

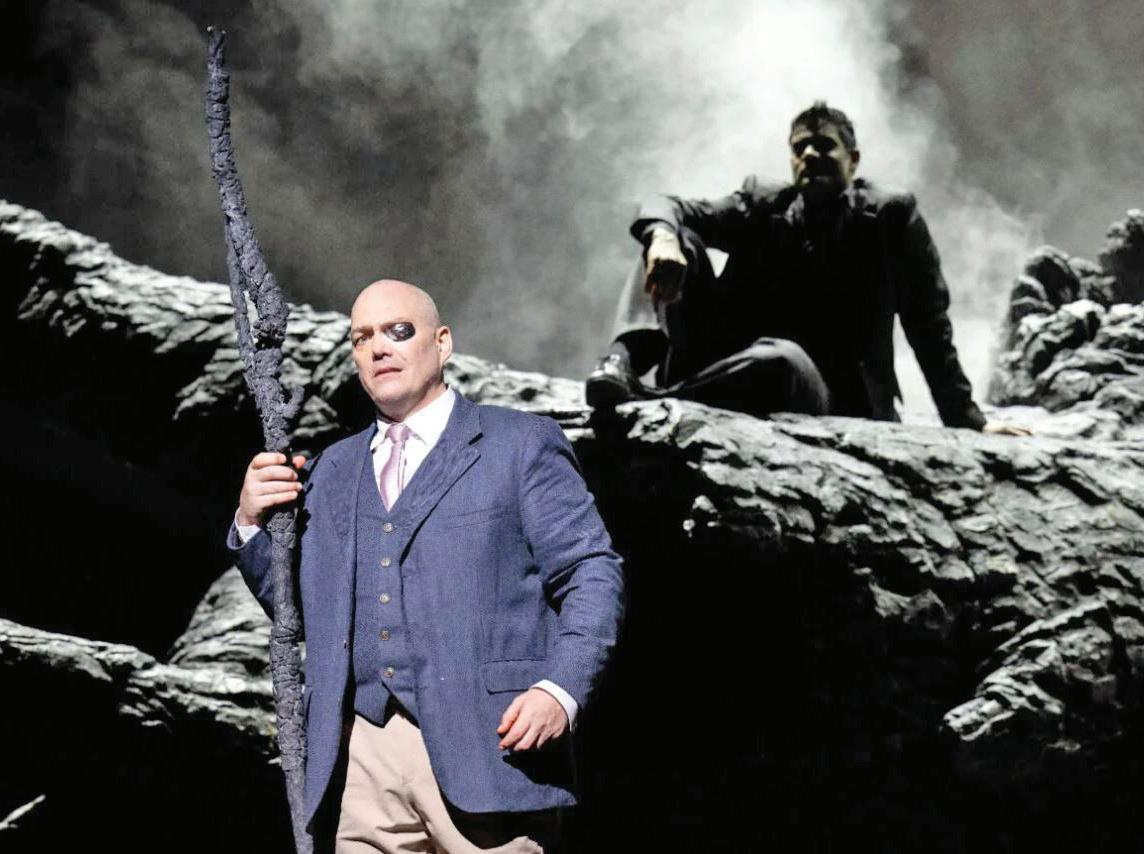

July 6 – Don Giovanni by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

July 13 – Das Rheingold by Richard Wagner

July 20 – Elektra by Richard Strauss

July 27 – Médée by Marc-Antoine Charpentier

August 3 – Damnation of Faust by Hector Berlioz

August 10 – Don Carlo by Giuseppe Verdi

August 17 – Rusalka by Antonin Dvorák

August 24 – Idomeneo by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

August 31 – Tosca by Giacomo Puccini

KZBY 90.5 FM

COOS BAY

KLMF 88.5 FM

KLAMATH FALLS

KNHT 102.5 FM RIO DELL/EUREKA

Grants Pass 101.5 FM Happy Camp 91.9 FM

Lakeview 89.5 FM

Langlois, Sixes 91.3 FM

LaPine/Beaver Marsh 89.1 FM

Monday through Friday..

5:00am Morning Edition

9:00am Open Air

3:00pm Today, Explained

3:30pm Marketplace

4:00pm All Things Considered

6:00pm World Café

8:00pm Folk Alley (M) Mountain Stage (Tu) American Routes (W) The Midnight Special (Th) Open Air Amplified (F)

10:00pm Turnstyles

3:00am World Cafe

Saturday..

5:00am Weekend Edition

9:00am Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me! 10:00am Radiolab

1:00pm Mountain Stage

3:00pm Folk Alley

5:00pm All Things Considered

6:00pm American Rhythm

8:00pm The Retro Cocktail Hour

9:00pm The Retro Lounge

10:00pm Late Night Blues

12:00am Turnstyles

Sunday..

5:00am Weekend Edition

9:00am TED Radio Hour

10:00am This American Life

11:00am The Moth Radio Hour

12:00pm Jazz Sunday

2:00pm American Routes

4:00pm Sound Opinions

5:00pm All Things Considered

6:00pm The Folk Show

FM Transmitters provide extended regional service.

FM Translators provide low-powered local service.

KSMF 89.1 FM ASHLAND

KSBA 88.5 FM COOS BAY

KSKF 90.9 FM KLAMATH FALLS

11:00am Snap Judgement 12:00pm E-Town

KNCA 89.7 FM BURNEY/REDDING

KNSQ 88.1 FM MT. SHASTA

KVYA 91.5 FM CEDARVILLE/ SURPRISE VALLEY

9:00pm WoodSongs Old-Time Radio Hour

10:00pm The Midnight Special 12:00am Turnstyles

Callahan/Ft Jones 89.1 FM Cave Junction 90.9 FM

89.3 FM

KSJK AM 1230

TALENT

KAGI AM 930

GRANTS PASS

AM Transmitters provide extended regional service.

FM Transmitter

FM Translators provide low-powered local service.

KTBR AM 950 ROSEBURG

KRVM AM 1280 EUGENE

KSYC 103.9 FM YREKA

Monday through Friday

12:00am BBC World Service

7:00am 1A

9:00am The Jefferson Exchange

10:00am Here & Now

12:00pm BBC News Hour

1:00pm Today, Explained

1:30pm The Daily

2:00pm Think

3:00pm Fresh Air

4:00pm The World

5:00pm On Point

6:00pm 1A

7:00pm Fresh Air (repeat)

8:00pm The Jefferson Exchange (repeat of 9am broadcast)

9:00pm BBC World Service

Saturday..

12:00am BBC World Service

7:00am Inside Europe

8:00am Left, Right & Center

9:00am Freakonomics Radio

KHWA 102.3 FM MT. SHASTA/WEED

KJPR AM 1330

SHASTA LAKE CITY/ REDDING

KPMO AM 1300

MENDOCINO KNHM 91.5 FM BAYSIDE/EUREKA

10:00am Planet Money/How I Built This 11:00am Hidden Brain

12:00pm Living on Earth

1:00pm Science Friday

3:00pm To the Best of Our Knowledge 5:00pm Radiolab

6:00pm Selected Shorts

7:00pm BBC World Service

Sunday

12:00am BBC World Service

7:00am No Small Endeavor

8:00am On The Media

9:00am Throughline 10:00am Reveal

11:00am This American Life

12:00pm TED Radio Hour

1:00pm The New Yorker Radio Hour

2:00pm Fresh Air Weekend

3:00pm Milk Street Radio

4:00pm Travel with Rick Steves

5:00pm To the Best of Our Knowledge 7:00pm BBC World Service

Ashland/Medford 102.3 FM

Klamath Falls 90.5 FM / 91.9 FM

Grants Pass 97.9 FM

98.7 FM

As Oregon’s Summer Skies Become Increasingly Filled With Wildfire Smoke, Some Communities Will Have An Opportunity To See Just How Unhealthy Their Air Is.

April Ehrlich/OPB

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality is launching a program that will give four communities air monitors for pollutants and identify potential solutions. The three-year pilot program, called Community Air Action Planning, can test the air for smoke particulates — whether from wood stoves or wildfires — as well as traffic pollution. They’ll measure meteorological data, like heat and wind direction, which could help regulators determine why pollution might gather in certain neighborhoods.

The program will work closely alongside community members to identify their air quality concerns, install monitors throughout the area, collect data, and compile it into a report. The report also will summarize narratives collected from residents, in part to find if there are specific areas that people avoid because of air pollution.

DEQ will select communities this summer based on a variety of socioeconomic, health and pollution indicators.

DEQ public engagement analyst Ryan Bellinson, who’s helping run the program, said it’s intended to empower communities and broaden DEQ’s work.

“DEQ will be supporting them in gaining agency and taking action for improving their air quality,” Bellinson said. “But they’ll also be helping us as a regulatory agency learn about how we can support overburdened communities in effective ways.”

Bellinson said he hopes to work with at least one community that’s heavily impacted by wildfire smoke, such as in Central or Southern Oregon. The program might also include a dense, urban community that’s particularly vulnerable to “black carbon,” which is soot from traffic and other fossil fuel pollution.

The three-year pilot program is funded by a $1 million federal grant, but Bellinson hopes to find additional funding to continue the program in future years.

Program staff will help community members identify where to install the monitors and how to get them serviced if they’re not working.

These monitors will likely collect data over a span of six months to a year, depending on what type of pollution community members are most concerned about. After that, the air program will help identify ways to mitigate pollution, like establishing clean-air shelters, distributing air filters, or finding ways to monitor other pollutants and toxins. Bellinson said the program has some money to help fund these solutions, and if that’s not enough, DEQ can help community members apply for grants or other funding sources.

“We want to work with the community so when they get the data at the end, they’ll be empowered to take action, whatever that might look like for them,” Bellinson said.

Three other agencies are partnering with DEQ on the program. Desert Research Institute, a Nevada-based nonprofit, will visualize the data collected from air monitors. The Portland-based nonprofit Neighbors For Clean Air will help DEQ staff build relationships with community members. Then, Portland State University will evaluate outcomes from the pilot program.

Copyright 2024 Oregon Public Broadcasting

Roman Battaglia/JPR News

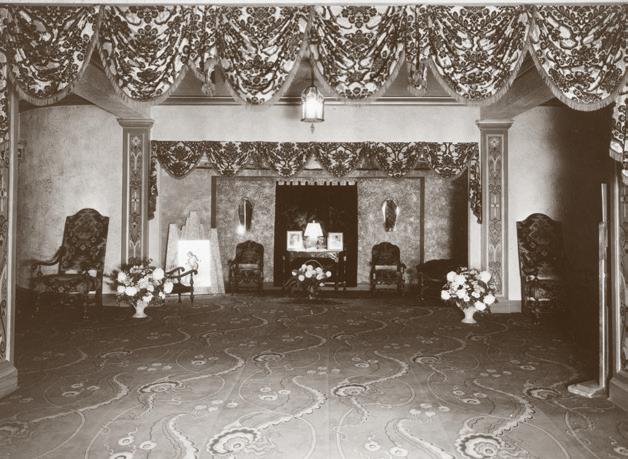

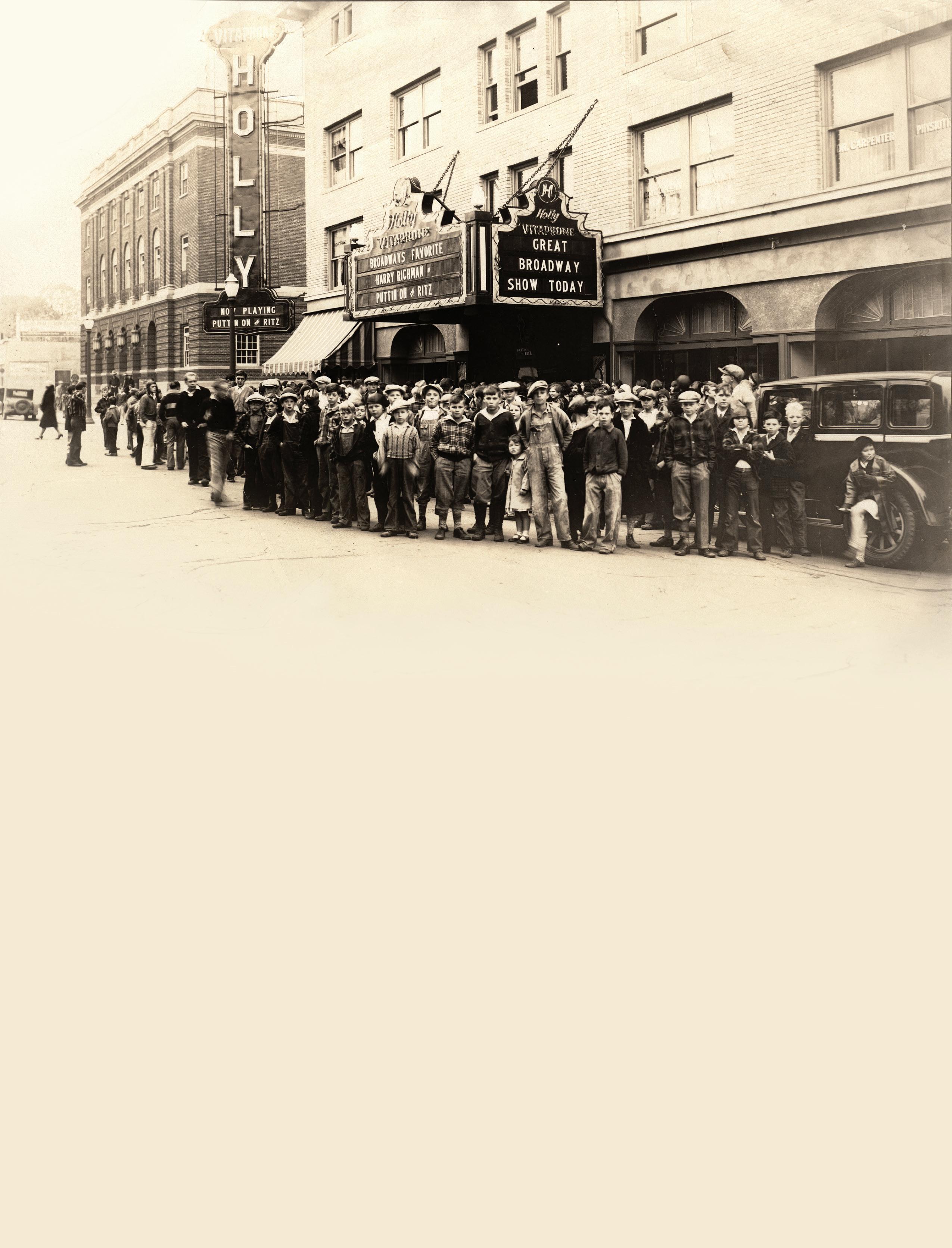

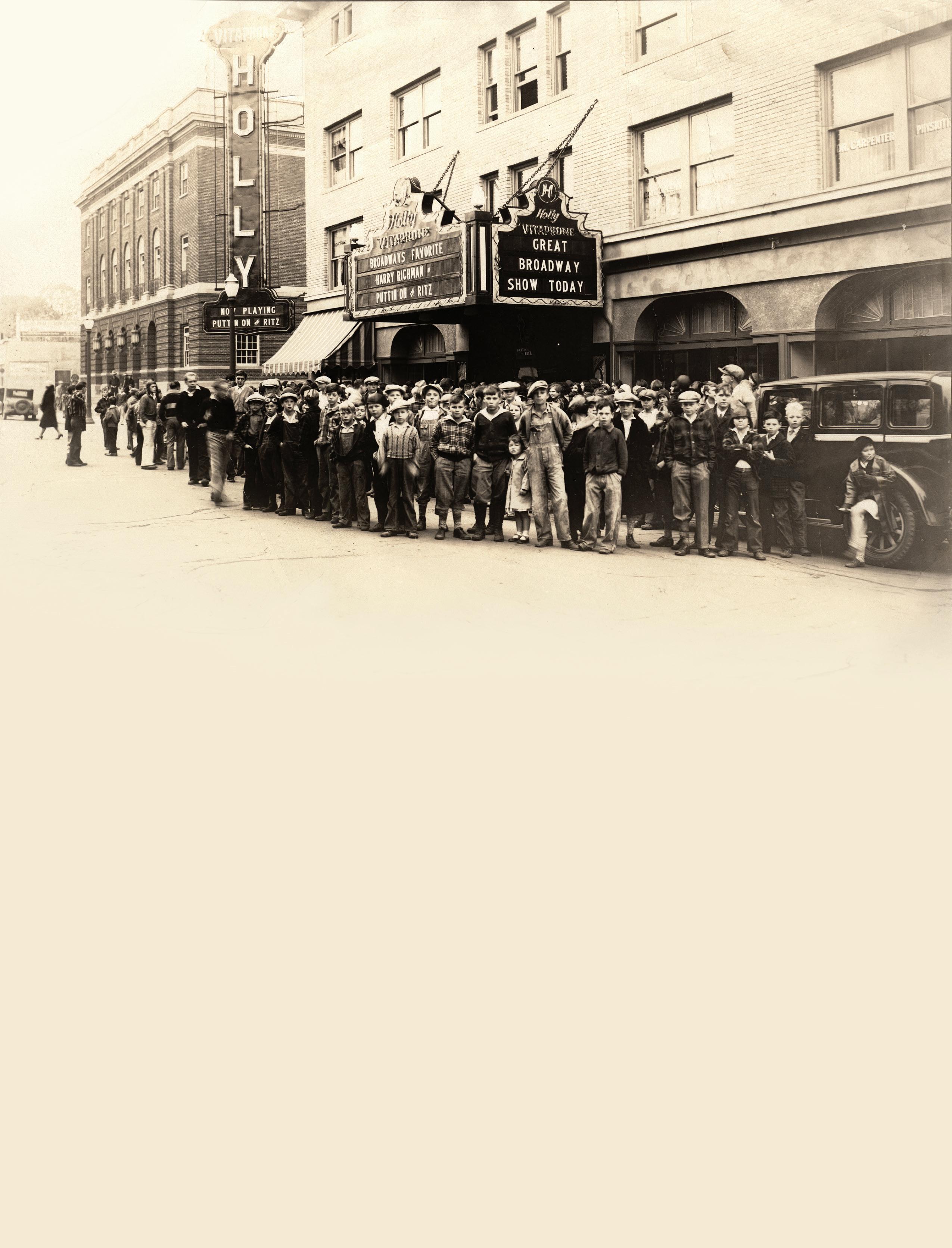

The Britt Music and Arts Festival has struck a deal with Jackson County to purchase a historic building in Jacksonville. Once the sale is finalized, the festival has plans to convert the building into an office and performance space.

The $1.45 million dollar purchase would further cement the Britt Festival’s role as a major economic driver in Jacksonville, where the festival grounds are located.

The 10,000-square-foot U.S. Hotel was constructed in the late 1880s, and is currently rented out to an antiques business.

This iconic building would be home to the Britt Festival offices, which are currently located in Medford.

Britt Festival President Abby McKee said they’ve been looking to move their offices to Jacksonville for 35 years.

“Britt is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and for us to amass support and funding to be able to purchase a new building, that’s a pretty major undertaking,” McKee said.

Jacksonville is also a tricky place to find a property like the one Britt staff were looking for, she said, because of the city’s many historic buildings and the lack of real estate to meet their needs.

McKee said the reason for their current Medford location is because many Britt patrons used to come from East Medford, and having the box office located closer made things easier before most tickets were sold online.

McKee said they’re planning on renovating the U.S. Hotel building to include a performance and education space upstairs.

“The ability to have a space that is our home, where we can welcome people in and have interactive opportunities, where people can be learning new skills or just experiencing the arts, that’s been a really exciting prospect for us,” McKee said.

It will take a few years to renovate the building, according to McKee. That includes things like seismic upgrades and installing an elevator.

Jackson County commissioners previously delayed a vote to sell the building to Somar Family Vineyards after the Britt Festival submitted a competing offer.

McKee said they’re currently in escrow while final inspections take place.

Roman Battaglia/JPR News

Ahousing affordability council with the state of Oregon approved an additional $12 million dollars to purchase new homes for a mobile home park that burned down in the 2020 Almeda Fire. The money will replace homes the state bought that were found to be defective.

Oregon Housing and Community Services originally purchased 140 modular homes from Nashua Builders in Boise, Idaho for $26 million. 118 of those were installed at Royal Oaks Mobil Manor in Phoenix.

But, after major construction defects were found a year ago, the state decided to entirely replace the homes.

On June 7, the state’s Housing Stability Council met to approve $12 million for the new homes, plus an additional $5 million in tax credits. That money will come from remaining state wildfire funds allocated after the 2020 Labor Day Fires.

OHCS Deputy Director Caleb Yant said they’re asking for this money before pursuing possible legal action against the Idaho manufacturer to keep the Royal Oaks redevelopment moving forward.

“It’s been noted that there aren’t court filings that have occurred and I want council members to know that that does not mean that we’re not actively pursuing accountability for not getting a product that we paid for,” he said.

Council Member Mary Li from the Multnomah Idea Lab said she had some concerns about the urgency with which the agency is moving forward with this funding request, especially when they haven’t addressed some of the other parts of the project, like the timeline for getting the units ready for move-in. The opening of Royal Oaks was originally slated for September 2023.

OHCS Executive Director Andrea Bell said that they’re working to push forward multiple pathways for this project at the same time.

“We are moving forward on the initial commitment made years ago to ensure that those homes are replaced and to ensure that the homes that are replaced are reflective of what people’s expectations are,” Bell said.

OHCS is also working with the Oregon Department of Justice to look into how the Idaho manufacturer of the defective homes can be held accountable.

The local housing authority in Jackson County is coordinating the purchase of the new homes and says they’ve found an

Oregon-based supplier, but they’re still in the procurement process and can’t yet reveal its name.

Roman Battaglia/JPR News

Should four state agencies enact new regulations on the use of jet boats on around 30 miles of river north of Medford? That’s the question being asked at a series of community meetings since mid May.

Some community members are hoping to ban the use of these boats, claiming they’re unsafe for other river users and disruptive to salmon populations.

Frances Oyung, the program manager at Rogue Riverkeeper said they’re concerned about the frequency of these high-speed jet boats, and how they’ll impact salmon populations (Oyung is a volunteer with JPR Music).

“The reason that Chinook and coho and the sea-running fish are threatened and having problems sustaining their populations is not because of one big event,” Oyung said. “It’s because of all the little events we do.”

A 1994 study on jet boat impacts in Alaskan streams suggest that high-level use in shallow streams can threaten the survival of salmon eggs.

Taylor Grimes is the owner of Rogue Jet Boat Adventures, which operates out of the TouVelle State Recreation Site in Central Point. Grimes said if people knew more about jet boats, they’d know they don’t pose a danger.

“I just think it’s a perception thing,” he said. “And then I think intertwined in there is some people that are just really uneducated.”

For example, Grimes said they record every boat trip in the event of any safety issues, and jet boats are highly maneuverable and can stop very quickly. He added that jet boats operate in shallower waters and don’t disrupt the underwater environment as much as boats with external propellers.

The four agencies that include the Oregon Department of State Lands, the Oregon State Marine Board, Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, are gathering public input through an organization called Oregon’s Kitchen Table.

After an online survey closes on July 5, the agencies will figure out if they need to enact new rules to restrict recreational usage on the Upper Rogue River. A report from Oregon’s Kitchen Table on the community meetings is expected in early August.

The opioid epidemic, boosted by the arrival of the drug fentanyl, has torn through communities in Southern Oregon. It’s also having a devastating impact on mothers struggling with addiction. An innovative facility in the Rogue Valley is helping those parents and their children.

When Karissa Camarillo became pregnant she was living in a tent behind a supermarket in Medford, addicted to the synthetic opioid fentanyl. She used up until the time she went into labor at a local hospital.

“I did not want my baby. I wanted to leave. I hated myself. I didn’t care. And then Kerri came in and gave me a little bit of hope,” says Camarillo.

She’s referring to the medical director for Oasis Center of the Rogue Valley, Dr. Kerri Hecox. Oasis specializes in treating parents and those who are pregnant for substance use disorders.

Hecox was at the end of Camarillo’s hospital bed when she woke up. She convinced Camarillo to enter Oasis’ program.

“I got support. I got counseling. I got forgiveness and respect, self-esteem. They helped me with everything because when I came here I was nothing,” Camarillo says. “And now I am who I am. And I’m so proud of it. And I’m so thankful for them.”

Camarillo has been clean for two and a half years now. She kept her baby.

Dr. Hecox says a clinic like this for mothers is unique. First, it doesn’t just treat someone for addiction. It also helps with the myriad of other issues they may be facing like legal trouble and food insecurity. There’s even a preschool here.

“We are coordinating all of these different pieces for families because if one of these isn’t there the family isn’t successful,” says Hecox.

Oasis is located in a one-story building by a busy freeway in downtown Medford. Inside, it lives up to its name. In its lobby is a fridge with fresh produce. There’s an area with bright carpet and toys for children. Through a gate around the back of the building is a shaded row of apartments for those that need housing.

“We’ve had probably at this point 60 people who’ve come through emergency lodging and 85% of them have gone on to residential treatment. So really, actually very good success rates,” says Hecox.

Another unique aspect of Oasis is that it offers long-term assistance. Hecox says that’s important, after all, because addiction is a long-term struggle. The center has been open for five and a half years. But Hecox says she’s seen some patients for a

decade, beginning before Oasis opened, allowing her to watch their children grow up.

Rebecca Stone, with the non-profit Justice System Partners based in Massachusetts, says the intersection of substance use and parenting has only recently started gaining widespread attention.

Opioid-related overdoses are now a leading cause of death for those who are pregnant or those that have recently given birth.

Stone says one problem faced by that population is access to care.

“We don’t have enough treatment options for the population in need as is. There are even fewer that will take a pregnant person or allow someone to stay there with their children,” says Stone.

Continued from previous page

Another barrier, she says, is the stigma of fighting addiction while pregnant.

“This sense of shame and the sense that you might be discriminated against, the sense that you are going to get into trouble for seeking help is huge,” she says.

Many fear if they enter treatment they will have their child taken away. But Dr. Hecox at Oasis says her clinic works with child protective services and no parent that has wanted to keep their child and who has entered treatment has lost parental rights.

Some might find it incredible that individuals would use drugs while pregnant. But, according to those struggling with addiction, that’s underestimating how powerful these drugs are — especially fentanyl. Hecox says it’s changed everything.

Daphne, a patient at Oasis who wants to just use her first name, used fentanyl while she was pregnant. She’s sober now and her healthy, five-month old son is sitting on her lap.

“You want so desperately to quit. You want your baby to come out healthy and not have to go through the withdrawals and the detox. But addiction is so cunning and it wraps ahold of you,” says Daphne. “No matter how bad you want to quit, it just won’t let you.”

Karissa Camarillo, who met Dr. Hecox after giving birth, is wearing scrubs today, sitting in an office at Oasis. After becoming sober, she was hired by the center to work with other mothers.

“I love being able to see somebody come in who is like a spitting image of me. Somebody that had no hope and no love for themselves just bloom into this wonderful, beautiful person,” says Camarillo.

Having a parent using drugs greatly increases the risk their child will also struggle with addiction. Camarillo’s whole family joined the effort to save her child.

“My dad got sober for me. Same with my mother. They’re all clean and sober now. We all did it as a whole family,” she says.

That means the staff at Oasis aren’t only helping those that walk through their doors — they’re helping their children. Their victories can’t be counted by individual cases but by generations.

Justin Higginbottom is a regional reporter for Jefferson Public Radio. He’s worked in print and radio journalism in Utah as well as abroad with stints in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. He spent a year reporting on the Myanmar civil war and has contributed to NPR, CNBC and Deutsche Welle (Germany’s public media organization).

Justin Higginbottom is a regional reporter for Jefferson Public Radio. He’s worked in print and radio journalism in Utah as well as abroad with stints in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. He spent a year reporting on the Myanmar civil war and has contributed to NPR, CNBC and Deutsche Welle (Germany’s public media organization).

MARISA KENDALL

Doctors on the front lines of California’s homelessness and mental health crises are using monthly injections to treat psychosis in their most vulnerable patients.

As Dr. Rishi Patel’s street medicine van bounces over dirt roads and empty fields in rural Kern County, he’s looking for a particular patient he knows is overdue for her shot.

The woman, who has schizophrenia and has been living outside for five years, has several goals for herself: Start thinking more clearly, stop using meth and get an ID so she can visit her son in jail. Patel hopes the shot — a long-acting antipsychotic — will help her meet all of them.

Patel, medical director of Akido Street Medicine, is one of many street doctors throughout California using these injections as an increasingly common tool to help combat the state’s intertwined homelessness and mental health crises. Typically administered into a patient’s shoulder muscle, the medication

slowly releases into the bloodstream over time, providing relief from symptoms of psychosis for a month or longer. The shots replace a patient’s oral medication — no more taking a pill every day. For people who are homeless and routinely have their pills stolen, can’t make it to a pharmacy for a refill or simply forget to take them, the shots can mean the difference between staying on their medication, or not.

“They’ve been an absolute game-changer,” Patel said. Street medicine teams bring the shots directly to their patients wherever they are — whether it’s in a tent along Skid Row in Los Angeles, in a dugout in the middle of a field in the Central Valley, or along the bank of a stream in Shasta County. Doctors can diagnose someone, prescribe the medication, get their