Page intentionally left blank.

Page intentionally left blank.

Abstract

Plants—due to their insentient and stationery nature—may not feel as 'alive' and, thus, not invite an emotional investment from some. In particular, Millennials—who, as a consequence of commonly not having a permanent residence and, hence, frequently moving—may find it difficult as plants are hard-to-move which, in turn, makes it unlikely for them to witness their gradual growth. Working under the umbrella of 'smart growing,' the study explores if Design for Attachment—an approach that helps foster emotional bonding with objects by turning them into something more meaningful—could help ensoul plants and, thus, turn them into heirlooms. In addition, with their temporary residential status in mind, it explores the impact of these heirlooms being inherited among tenants—and not family. By turning them into heirlooms, the study hopes to evoke an emotional connection, which will generate genuine interest in growing within the demographic.

While working with Millennial participants serving as caretakers, the study uses an iterative web-hosted experiential prototype to investigate the question ‘How might Millennials form a meaningful emotional connection with plants?’ This prototype establishes a co-designed online presence for plants; and by doing so, gives each a distinct identity and history indexed on the IoT. It then iterates a fictitious timeline of previous caretakers. Through this, the study investigates the following. First, the impact that investment of memories, anthropomorphization, rarity, and aficionado appeal have on forming an attachment with a plant. Second, the influence that the number of previous caretakers has on increasing the sense of responsibility.

Introduction

Plants tread a fine line between being inanimate and ‘alive.’ They, generally, do not move and are rooted to the ground. In addition, they grow gradually and have an average lifespan that easily outlasts domestic pets. On top of that, they’re insentient and, thus, incapable of real-time twoway communication. Consequently, for some, forming a lasting emotional connection with them can be challenging—especially if they have little time, capital, or space to spare. Case in point: Millennials, who—as a consequence of commonly being overworked, in debt, and renting their homes—have neither.

Disconcertingly, they also happen to be the generation most affected by the climate crisis, along with their physical and mental health declining at a faster rate than others (Hoffower, H., 2019). Well-being, interestingly, links back to plants, as it has a fundamental affinity with horticulture—be it, Environmental, Physical, or, curiously, Mental well-being. Apart from the obvious, a review of gardening-based interventions for people experiencing mental health difficulties, for instance, reported substantial improvements among the participants (Clatworthy, J., Hinds, J. & Camic, P.M., 2013). Reassuringly, the gardening market has seen steady growth, thus benefiting a larger populace. However, research suggests that 41 is the average age that people in the UK are getting into it (Heath, O., 2018)—making it an activity predominantly partaken in by the elderly.

Therefore, exploring how to encourage horticulture among Millennials would be the overall goal of this study. In particular, though, with the current constraints, circumventing the barriers

to forming a lasting emotional connection with plants will be explored. An emotional connection will lead to empathy, thus evoking interest. Additionally, It will make the interaction more meaningful, natural, and, therefore, recurring. Hence, through a Research-through-Design approach, this study will explore the research question, ‘how might Millennials form a meaningful emotional connection with plants?’

For this research, given that plants, like most tangible products, are insentient, motionless, and have enormous lifespans, we would be exploring Design for Attachment (henceforth DfA): an approach that helps foster emotional bonding with objects—by turning them into something more meaningful: ensouled. And in doing so, also explore the medium of storytelling. Via our physical-digital prototypes, we would be analyzing the impact of embedded lore, and the investment of irrecoverable memories, on forming an attachment with a plant—which we hope would be the most effective way of conducting this investigation.

was 41 (Heath, O., 2018). To gauge why younger demographics—and millennials, in particular— were not participating as actively, we created a persona followed by the Five Whys method used introspectively.

Background

The Research through Design module run by the University of Dundee was interested in exploring the topic of 'Better Smart Growing.' Our first instinct was to explore how the expansion and ever-increasing integration of the Internet of Things (henceforth IoT) had affected horticulture. Naturally, given how some demographics are more techno-savvy than others, we explored how different generations compared. Preliminary desk research indicated that the average age that people in the UK were getting into Gardening

Sanskriti recently moved from India to Dundee to pursue her Masters. She had booked college accommodation for her one-year course. Her new rented room, she found, is relatively small, and she’d need to prioritize how she uses the space. The interior is also not to her liking, but being an indebted college student, she has chosen to compromise. Besides, she doesn’t get to spend much time at home—consequence of managing her academics, part-time job, and social life. Disconcertingly, this has started to take a toll on her mental health. To alleviate this, she considered buying a pet for emotional support; however—ignoring the fact that pets aren’t allowed as per her contract—she wouldn’t have the time, space, or capital to take care of it. She’s recently heard about Green Therapy, but is uncertain whether she’ll be motivated to grow a plant.

The persona (Figure 1) highlighted issues that Millennials generally face. Take, for instance, balancing their college, work, and social life. This

consequently leaves them with little time and takes a toll on their mental health. The persona also brought up how Green Therapy may be a possible alleviator. However, since making time is difficult, this leaves practicing horticulture in their personal spaces as an option. Disconcertingly, their commonly temporary residential status makes this challenging.

Why don’t I grow my food?

“I don’t know how to.”

Why don’t I teach myself?

“I’m not motivated to learn.”

Why am I not motivated to learn?

“I don’t feel the same emotional connection with a plant - as I would with a dog.”

Why don’t I have an emotional connection with a plant?

“They don’t feel as ‘alive’ to me.”

Why don’t they feel as ‘alive?’

“Plants tread a fine line between being inanimate and alive.”

Literature Review

The Five Whys method (Figure 2) indicated that a lack of emotional connection—a consequence of plants not feeling as ‘alive’—might be a predominant cause. Consequently, we arrived at our research question: ‘How might Millennials form a meaningful emotional connection with plants?’

Studies surrounding DfA indicate that stories and the investment of memories can help effectively foster an emotional attachment by increasing an object's perceived value in the eyes of the user. The project 'Tales of Things and Electronic Memories' (henceforth ToTEM) (Speed, C. & Macdonald, J., 2013) best demonstrates this. By offering a platform where users could attach stories to 'old' objects—objects that would have otherwise been discarded—the project explored if they can be encouraged to reuse and retain. They envisioned that, through the investment of users' memories, mundane objects might turn into heirlooms—elevating them in their emotional importance. Similarly, Significant Objects (Walker, R. & Glenn, J., 2009) also documented the impact of added lore on the increase in an object's perceived value. By adding clearly-stated fictional stories, the researchers were able to sell $128.74 worth of 'thrift store junk' for $3,612.51. Although monetary, the upsurge resulted from the lore's significance in the eyes of the buyer, therefore also making it emotional. These studies validate the effectiveness of DfA when it comes to ensouling objects; however, a plant is a living being. Given its qualities of being insentient, motionless, and especially its enormous lifespans, though, leveraging an emotional investment via turning it into an heirloom would be interesting.

A real-life instance of the ensoulment of plants via the investment of memories on the IoT is explored in the article ‘The Case for naming our Trees’ (Hallamaki, L., 2018). The piece documents how—to protest the cutting of almost 20,000 street trees—Sheffield residents named a few and even created a Twitter handle for two. As

a result, Vernon Oak (Figure 3) was saved from being chopped, while Duchess Lime got replanted. These identities made it easier to identify and discuss the trees in question, making conversations feel more personal and natural. They also made online indexing more straightforward. This new unique identity, combined with their new social media presence, also likely anthropomorphized them, as evidenced by the residents later physically engaging in decorating and dressing them. These acts also indicate a rise in empathy, the trees’ emotional importance, and elevation to ‘landmark status’ within the community.

generate, index, and share engagements online—and, therefore, elevated their importance in the eyes of the stakeholders. In parallel, these interactions also likely leveraged the ‘memory economy,’ a term evoked by the ToTEM lead Chris Speed in a blog post (Speed, C., 2010). It presents an alternate economy of value where— instead of focusing on novelty—importance is added through the attachment of history to artifacts on the IoT. Although this term refers to the cataloging of memories associated with objects, given that a likely barrier to forming an emotional connection with plants is their insentient nature, it would be interesting to envision them as the host for the ‘memory economy;’ and not the subject themselves.

The Vernon Oak—along with ToTEM and Significant Objects—also likely benefited from two common attachment patterns discussed in the paper ‘How Deep Is Your Love’ (Jung, H. et al., 2011) effective in achieving ensoulment: rarity and aficionado-appeal. Rarity, the piece asserts, needs to invite users to engage and learn more about the object; instead of just being a ‘readymade unique thing.’ And in doing so, tap into the ‘aficionado-appeal,’ which is the investment caused by expertise arising from time spent learning about the object. The unique identities of the trees in Sheffield, for instance, not only gave them a sense of rarity, but they also helped

One principle distinction between most objects cataloged in the DfA projects and plants is that most plants are hard to move, if not immovable—making them both difficult and expensive to relocate if their planter moves. Take, for instance, the Vernon Oak in Sheffield. Disconcertingly, one-in-two millennials in the UK are projected to be renting their homes until their forties (Savage, M., 2018). Consequently—given their relatively temporary residential status—plants may not always work as heirlooms passed down within a family and instead call for a community effort. Thus, through our prototype, we would be conceiving them as heirlooms passed down among tenants or shared within communities.

When it comes to developing an emotional attachment with an object, research (VanMeter, R.A., Grisaffe, D.B. & Chonko, L.B., 2014) suggests that behavioral changes within certain factors are prominent indicators. These, the

research asserts, are distress upon separation, seeking a safe haven, and proximity maintenance. Therefore, these indicators would be

used to measure the formation of emotional investment within this study.

Insights from the literature review were mapped on an Affinity Diagram (Figure 4) to supplement the ideation process. These, combined with the Persona (Figure 1) previously created, were used to produce a Long-Range Forecast (Figure 5) for how, in our opinion, future technologies may enhance interactions with plants. The forecast brought up concepts like:

• Anthropomorphization via interacting with AI and being able to access its vital stats.

• The excitement to learn more about the plant. Which may later lead to the 'aficionado

appeal.'

• Being able to visualize the life of a plant via a timeline.

• Turning it into an heirloom inherited from the previous tenant via the investment of memories.

• The participatory nature of the memories invested in the plant.

• An increased sense of responsibility—a consequence of being able to picture the number of previous caretakers.

7th September 2091

I reached Scotland today to begin my college life at the University of Dundee. I couldn’t wait to know more about the place and create new memories. I was pleasantly surprised when my phone connected to a plant I was apparently inheriting from the previous tenant, and my curiosity grew. While on my way, I messaged, “Hey! I’m Azad. The new tenant. What’s your name? How old are you?” The plant replied, “It’s bad manners to ask someone their age.” Confused, I quickly pulled up its stats, and the app said it was content. It had even been watered just the day before. “Well, it has some personality,” I thought while laughing. When I entered my room, I was greeted by a money tree, half the room’s height. It said cheerily, “I’m Milan. I’ve been living here since 2077. Now you do the math.” “Woah! That’s 14 tenants you’ve lived through,” I remarked as I accessed its memories. And there they were, all the tips and tricks, places to eat, socialize and visit—all based on the memories of the previous tenants. And, in the end, a blank chapter with my name on it—Milan’s 15th caretaker.

Figure 5: Long-Range Forecast

Using these concepts—and taking inspiration from the social media presence created for the trees in Sheffield (Hallamaki, L., 2018)—an idea for an iterative experimental prototype was conceived. Furthermore, it was decided that—at the beginning and end of each iteration—a self-re-

ported questionnaire gauging the indicators for attachment with an object would be shared. These indicators would be Proximity Maintenance, Safe Haven, and Separation Distress, which were previously discussed in the literature review.

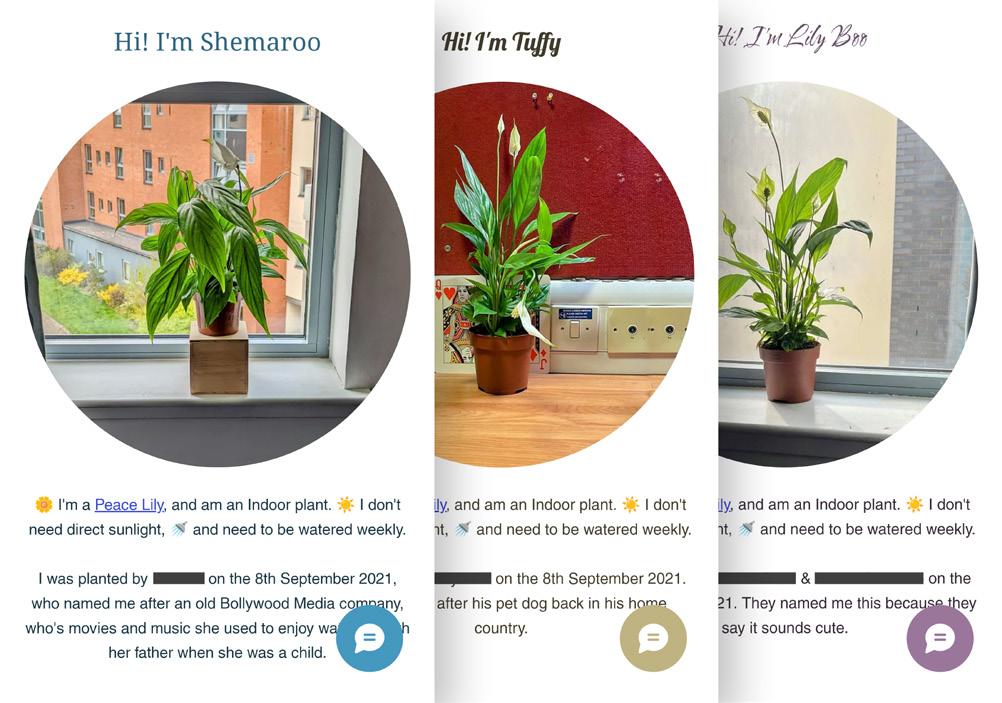

Experience Prototyping - Ensoulment

The prototyping stage began by exploring whether DfA can ensoul and thus lead to an emotional connection with plants. To begin, participants were given seven potted Peace Lilies (Figure 6) to take home. Participants selected were Millennial expatriates who were either pursuing education or working. Furthermore, these plants were distributed per room, meaning if two participants were sharing a space, they got one plant. This added up to a total of 10 participants. Then, an identity was codesigned (Figure 7) for each plant. This meant that the participants decided on their plant's name, shared why they named it that and made choices regarding aesthetics.

Based on this—and positioning the participants as the original planters—seven web-hosted Experiential Prototypes were developed, which contained the following. First, the plant’s name with a greeting in the selected color and font. Second, its profile picture. Third, care instruction coupled with a link to a more detailed web resource. Fourth, a short bio containing when and who it was planted by and the meaning behind the plant’s name. And fifth, a chat box with the researcher posing as the plant AI. Finally, a nametag with the QR code to this online presence was printed (Figure 8) and placed on the pots.

The pots chosen were purposely generic. In addition, the printed name tags were bland by design. This was done because the study did not want to have aesthetics elevate the ‘value’ of the plants—and instead, wanted to focus solely on ensoulment. Therefore, for all plants’ tags, a black san serif font and a square QR code were used. Furthermore, to consume less time of the participants, Peace Lilies were chosen because they’re indoor plants that require relatively less care. Additionally, their smaller size allowed them to be easier to move and consumed less space. On the digital side, the presence was hosted privately online and wasn’t indexed on search engines, meaning it was only accessible via the QR code or the URL. This was done to make it easier to understand analytics by restricting traffic. Also, when it came to aesthetics, unlike the nametag, the online presence was given more personality via incorporating the design choices of the users. Additionally, the profile picture was framed in a circle and the text was centered, which was more akin to a person’s social profile.

It was hoped that the plant’s name and the name’s meaning would act as the participants’ invested memories. These invested memories, and the lore they created, would elevate the plant’s value in the ‘memory economy’ (Speed, C., 2010). This identity, coupled with the profile picture and chat, would also help anthropomorphize it and, thus, make it rare—and rarity was discussed to be effective for ensoulment (Jung, H. et al., 2011). Finally, the care instructions leading to another resource would be the first step towards the aficionado appeal.

In the middle of this project, two participants trav-

eled elsewhere for their holidays. While one had a roommate who could take care of the plant, the other did not. The participant without a roommate decided to return her named plant (Figure 9) to the researcher for the duration. Interestingly, she was the only one who independently initiated conversation through the chatbox. This conversation was regarding the well-being of the plant. Consequently, this indicated a substantial increase in the need for proximity maintenance when the responsibility of the plant’s care went to someone comparatively unfamiliar.

Furthermore, as a result of the researcher being returned a plant, the study got more personal insights through self-testing. For instance, it was noticed that the researcher invested more time and effort in the well-being of the plant. Take, for instance, adding support to keep it from slouching (Figure 9). In addition, compared to other plants, a more prominent place was given to it within the room. Interestingly, this had happened irrespective of the following factors: the pot cho-

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Disagree

sen to be generic in both shape and color, and the name tag being purposely made to be aesthetically bland. This suggested that importance was being generated not from aesthetics but ensoulment.

Disconcertingly, It was also felt during self-testing that the online presence felt static and, therefore, didn’t elicit the desire to spend time on the page or revisit. Analytics from the website also echoed this. They indicated that—apart from the one who had been using the chat function—the participants spent little time and rarely revisited.

I like being close to this plant. (Proximity Maintenance)

Strongly Agree

When I’m down, this plant can help me feel better. (Safe Haven)

Strongly Agree

Strongly Disagree

I would miss this plant if I didn’t have it. (Separation Distress)

Strongly Agree

Strongly Disagree

This plant feels alive to me. ‘Feels’ being the key word.

*Result average on a likert scale from 1-5. Before After Figure 10: Results of Self Reported Surveys

Strongly Agree

The results from the questionnaire (Figure 10) shared before and after the inception of the plant’s online presence presented us with two key insights. First, there was an increase in emotional attachment after the placement of the name tag. And second, the plant felt more ‘alive.’ Unnamed plants elicited a largely indifferent attitude. They did, however, score slightly high on Proximity Maintenance and Safe Haven. Since research had shown earlier that plants naturally have a positive impact on peoples’ mental health (Clatworthy, J., Hinds, J. & Camic, P.M., 2013), this increase was attributed to that. Afterward, having ensouled the plants via the application of name tags and inception of their online presence, the participants’ attitude decisively moved towards being emotionally attached.

The participants were also asked if the page had prompted them to research more about the plant. This was done to gauge whether they had taken the time to click on the link to the more detailed source to learn more—thus, taking the first step towards the aficionado appeal. Disconcertingly, only thirty percent responded positively. This— combined with how participants spent little time on the page—suggested that the next iteration of the prototype needed to be more engaging.

exploration of solely inheriting an ensouled plant became an interest. Consequently, the following was decided. First, the participants would create an avatar of themselves via an online resource. These would be added to their respective plant's online presence. Second, building on these original planter avatars, and using others in a random order, a fictitious timeline (Figure 11) of previous caretakers would be created. Third, based on this timeline—and with the researcher posing as the previous link in the chain—the plant would be taken from the original planter and given to the new inheritor.

Experience Prototyping - Timeline of Caretakers

In the previous iteration, the plants had been ensouled by their respective caretakers, and they had also been positioned as its original planter. It was felt that these factors may have been a predominant factor in forming an attachment. Therefore, for the second iteration, the

The timeline—which was added at the bottom of the existing page—was conceived to make this iteration more engaging by building on the Social IoT interest of this study. It, therefore, contained participants’ avatars connected via a dotted line resembling a social network. Underneath their avatars followed their names and the duration of ownership. It was felt that the design decisions used to create the avatars would lead to more thought and effort being invested by the participant—when compared to simply submitting their

existing pictures. This greater investment would lead to more engagement.

It was believed that inheriting a plant with a timeline of previous caretakers would help with the following. One, the participants would be able to visualize the plant’s life in the context of past caretakers and thus feel that it’s ‘alive.’ Two, its unfamiliar history of invested memories in the form of avatars will enhance the sense of rarity, leading to intrigue. The intrigue will also make the prototype more engaging and, eventually, the aficionado-appeal. Three, as the number of caretakers in the timeline would increase, so will the feeling of responsibility among the inheritors. To further analyze these theories, it was decided that two separate timelines (Figure 12) would be created for each plant. The first, where there would only be the researcher before the inheritor(s). And the second, where there would be the researcher and three other previous links before the inheritor(s).

Timeline 1

Timeline 2

Inheritor Researcher Participant

Figure 12: Two Timelines

Resistance was felt from caretakers when asked to return the plants that they had ensouled. Take, for instance, a participant who said, “Although I knew this was coming, I feel bad. I’ll just say that don’t change its name. Also, can I know who it’s going to?” In addition, through the analytics, another participant was noticed returning to their original plant via the direct URL. These instances—coming despite knowing that their plants were merely being exchanged with an almost identical plant of the same species—not only supported the formation of an emotional attachment, but also suggested that the irrecoverable nature of the memories invested may have culminated in the desire to not relinquish.

Strongly Disagree

I like being close to this plant. (Proximity Maintenance)

Strongly Agree

Strongly Disagree

When I’m down, this plant can help me feel better. (Safe Haven)

Strongly Agree

Strongly Disagree

I would miss this plant if I didn’t have it. (Separation Distress)

Strongly Agree

Strongly Disagree

This plant feels alive to me. ‘Feels’ being the key word.

*Result average on a likert scale from 1-5. Before After Figure 13: Final Results of Self Reported Surveys

Strongly Agree

The results of the self-reported survey (Figure 13), when compared to the previous iteration, showed negligible change. Thus indicating that either participants’ positioning had a low bearing on the formation of the emotional attachment or, if it didn’t, then possibly the sense of responsibility created via the timeline was an equally viable substitute.

In furtherance, when asked which plant evoked more sense of responsibility, the participants unanimously chose the ones that had a comparatively longer chain of previous caretakers. This strongly suggested that as the chain increased, so did the feeling of responsibility and, consequently, its value. This likely happened because, as the attachment of history increased through the addition of previous caretaker avatars, so did the plant’s perceived value in the eyes of its caretakers—thereby leveraging the concept of the ‘memory economy’ (Speed, C., 2010).

This iteration also saw a rise in participants researching more about the plant. When asked: the percentage jumped from thirty for the earlier iteration to sixty. Although, this may have been the result of now having prolonged access to the same species of the plant and a variation of the prototype. Nevertheless, the retention time of the page had increased noticeably, which supported the notion that an increase in engagement may have been a contributing factor.

Although the rate of return, in contrast to retention, remained low, it was felt that this was comparatively unimportant. This was because the primary goal of the online presence was to transfer value, which could happen with limit-

ed visits as long as the caretakers took time to engage—which the analytics suggested was happening. Their value elevating was further evidenced by all seven plants continuing to flourish—as a result of being taken care of—within the three weeks that the study ran.

Recommendations

The study explored the question 'How might Millennials form a meaningful emotional connection with plants?' It set out to do so by applying principles of DfA—an approach that helps create an emotional connection with objects by turning them into heirlooms—to plants. In addition, given the demographics commonly have a temporary residential status, the study positioned plants as heirlooms inherited among tenants—and not family. It found that Millennials are more likely to feel that plants are 'alive' if—through the investment of irrecoverable memories—plants are ensouled. It also found that this stands true whether or not these invested memories are of the caretakers, given that they're engaging. The study saw that the irrecoverable nature of these invested memories may lead to the desire not to lose the plant. Finally, the study found that the feeling of responsibility increases within the inheritor if previous caretakers are illustrated via a timeline—with the increase directly correlating with the number of past caretakers.

For further research, given the intimate nature of emotional connections, vast lifespans and hardto-move nature of plants, the study recommends the investigation being more longitudinal. Having it be so would allow a deeper understanding and further exploration of the aficionado appeal,

which requires time to cultivate. Furthermore, our study required the participants to imagine inheriting the plant, however, if the research ran longer, it would have been more interesting to witness the act in reality. Finally, a longer study would also indicate whether or not the emotional connection leads to the demographic gravitating towards gardening.

Further research can also go into exploring means of gauging an emotional investment other than the self-reported surveys employed in this research. Employing a variety of approaches would reduce any biases that may have been present and, therefore, give more credibility to the findings.

Another avenue for research could be to ensoul plants not via an online presence—which is only accessible when searched for—but more physical, and, therefore, ever-present means. Thereby also tackling the low rate of return that the prototype faced. Take, for instance, via the use of materials, textures, audio and lights.

To increase the rate of return, the study recommends that—apart from being engaging—further studies need to be more interactive. Although our study had the plant AI chat box, it was felt that the participants largely avoided using it. Therefore, these interactive integrations need to be more inviting.

Other projects may also consider ensouling trees—which have a more shared ownership than potted plants. It would be interesting to explore how division of responsibility develops. Furthermore, because they have a compara-

tively longer life, having them be a window into the past via documenting their surroundings and stories throughout the years would allow for a richer lore.

Finally, in our study the participants were unaware of the average age of the plant. Therefore, it would be interesting to explore how they interact with the plant, if via the timeline they find that it has reached the end of its average lifespan. Would this increase the sense of responsibility, or would it lead them to reducing their effort?

Bibliography

• Clatworthy, J., Hinds, J. & Camic, P.M., 2013. Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review.

• Hallamaki, L., 2018. The case for naming our trees. Trees for Cities. Available at: www. treesforcities.org/stories/the-case-for-namingour-trees [Accessed April 11, 2022].

• Heath, O., 2018. This is the age Brits officially get into gardening. House Beautiful. Available at: www.housebeautiful.com/uk/garden/news/ a1713/age-brits-officially-get-into-gardening/ [Accessed April 17, 2022].

• Hoffower, H., 2019. American millennials' mental and physical health is on the declineand they're on track to die faster than gen X, a new report says. Business Insider. Available at: www.businessinsider.com/millennials-gen-x-mortality-rate-mental-health-depression-2019-11 [Accessed March 25, 2022].

• Jung, H. et al., 2011. How Deep Is Your Love: Deep Narratives of Ensoulment and Heirloom Status. International Journal of Design, Volume 5(1), pp. 68

• Savage, M., 2018. One in three UK millennials will never own A home – report. The Guardian. Available at: www.theguardian. com/money/2018/apr/17/one-in-three-uk-millennials-will-never-own-a-home-report [Accessed April 23, 2022].

• Speed, C., 2010. Grave to Cradle: An Internet of Old Things. Chris Speed. Available at: chrisspeed.net/?p=261 [Accessed April 11, 2022].

• Speed, C. & Macdonald, J., 2013. TOTeM (Tales of Things and Electronic Memory). The Omnimuseum Project. Available at: omnimuseum.org/totem-tales-of-things-and-electronic-memory.html [Accessed April 11, 2022].

• VanMeter, R.A., Grisaffe, D.B. & Chonko, L.B., 2014. Of “likes” and “pins”: The effects of consumers' attachment to social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 32, pp.70–88. Available at: rc.library.uta.edu/uta-ir/handle/10106/26665 [Accessed May 1, 2022].

• Walker, R. & Glenn, J., 2009. About the Significant Objects Project. Significant objects. Available at: significantobjects.com/about/ [Accessed April 12, 2022].