Bold Action for Birds

American Bird Conservancy (ABC) takes bold action to conserve wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. Inspired by the wonder of birds, we achieve lasting results for the bird species most in need while also benefiting human communities, biodiversity, and the planet’s fragile climate. Our every action is underpinned by science, strengthened by partnerships, and rooted in the belief that diverse perspectives yield stronger results. Founded as a nonprofit organization in 1994, ABC remains committed to safeguarding birds for generations to come. Join us! Together, we can do more to ensure birds thrive.

Bird Conservation (ISSN: 3067-2228) is the member magazine of American Bird Conservancy and is published three times annually. Nonprofit postage paid at San Diego, California.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Bird Conservation, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198. Send undeliverable copies to American Bird Conservancy, 8255 E. Main St., Suite D & E, Marshall, VA 20115. Return postage guaranteed.

Copyright 2025 American Bird Conservancy

Join Us

If you’re not already an ABC member, we invite you to join us. Members at any of our five levels of commitment receive a one-year subscription to Bird Conservation, access to members-only events and webinars, a choice of premiums, and other offers. Give now at abcbirds.org/membership or see contact details below.

Connect

Magazine feedback: We welcome letters to the editor and other feedback. Contact us at: magazine@abcbirds.org.

Membership or other inquiries: Contact us at American Bird Conservancy, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198 | 540-253-5780 | info@abcbirds.org

Sign up to receive emails from ABC: abcbirds.org/email

Find and follow us on social media:

MAGAZINE STAFF

Vice President, Communications and Marketing Clare Nielsen

Director of Communications

Jordan E. Rutter

Managing Editor Matt Mendenhall

Graphic Designer Maria de Lourdes Muñoz

Writer/Editor Molly Toth

Director of Brand Strategy and Web Som Prasad

Science and Policy Consultants

Steve Holmer, Hardy Kern, Daniel Lebbin, George E. Wallace, David A. Wiedenfeld

Contributors Ben Catcho, Anna Deichmann, Chris Farmer, Annie Hawkinson, Hardy Kern, Bryan Lenz, Sea McKeon, John C. Mittermeier, Jack Morrison, Veronica Padula, Holly Robertson, Steve Roels, Christine Sheppard, Marcelo Tognelli, Liz Virgl, Amy Upgren

COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING TEAM

Director of Marketing Lara Long

Multimedia Producer Erica Sánchez Vázquez

Bird Library Specialist Gemma Radko

Media Relations Specialist Agatha Szczepaniak

Social Media Specialist Emily Williams

Digital Marketing Specialist Noah Kauffman

Digital Content Specialist Kathryn Stonich

ABC MANAGEMENT TEAM

President Michael J. Parr

Vice President of Advocacy and Threats

Programs Brian Brooks

Vice President of Development Erin Chen

Vice President of Finance Angela Modrick

Vice President of Operations Kacy Ray

Vice President of Policy Steve Holmer

Vice President of Threatened Species

Daniel Lebbin

Vice President of Together for Birds

Naamal De Silva

Vice President of U.S. and Canada

Shawn Graff

Vice President and General Counsel

William “Bishop” Sheehan

Senior Conservation Scientist David Wiedenfeld

Director of International Programs Amy Upgren

Director of Migratory Bird Habitats in Latin America and the Caribbean Andrés Anchondo

Oceans and Islands Director Brad Keitt

Central Regional Director Jim Giocomo

Southeast Regional Director Jeff Raasch

Western Regional Director Maria Dolores Wesson

MEMBERSHIP TEAM

Membership Director Kelly Wood

Membership Coordinator Jenna Chenoweth

Database Quality Coordinator Jamie Harrelson

Office Manager Cindy Elkins

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Larry Selzer, Chair

Michael J. Parr, President

David Hartwell, Treasurer

Mike Doss

Jonathan Franzen

Maribel Guevara

Josh Lerner

Annie Novak

Ravi Potharlanka

Carl Safina

Amy Tan

Stephen Tan

Shoaib Tareen

Walter Vergara

Jessica Wilson

In Every Issue

4 Chirps

Feedback about our redesign.

5 From the Perch Hope for a future free of extinctions.

6 In Focus

The endangered tanager of Bolivia’s High Andes.

8 Bird Calls

New bird reserves in Chile and Peru, how drones are helping Hawaiian honeycreepers, protecting the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and more news.

14 The Stopover Sandy beaches and dunes, and the birds that rely on them.

38 Together for Birds Seeking kinship with seabirds.

40 Bird Hero Dave Ewert’s lifelong commitment to birds.

42 Action & Advocacy Tips for gardening without harsh pesticides.

43 Field Notes

Summer 2025

Lasting Stewardship for Bird Reserves

How a 10-year-old initiative is helping bird reserves in more than a dozen countries remain sustainable — and focused on conserving rare birds. 18

Filling the Gaps

ABC research is shining new light on which Latin American birds are least protected — and how much habitat must be conserved to reduce their extinction risk. 26

Celebrating Andean Birds

The authors of Birds of the Tropical Andes share the story of how their stunning new book came to life. 32

To catch an oystercatcher.

44 The Science of Birds Concern and hope for common birds, a desertnesting seabird, and more.

46 The Art of Birds

Community bird art from Hawai‘i to Peru.

48 The Cache A film and books about bird conservation.

49 Flock Talk How to get our new hat, readers’ photos, and more.

50 Field of View

Remembering riches amid tireless hope.

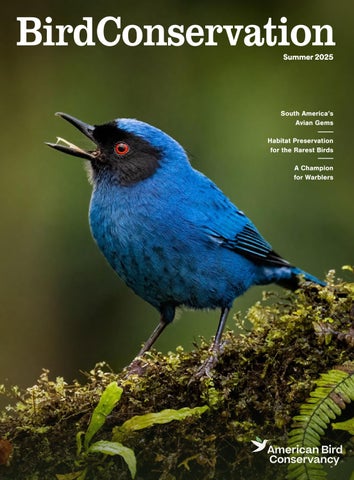

Cover photo

Masked Flowerpiercer at The Birdwatcher’s House-Santa Rosa Bird Lodge in Ecuador by Owen Deutsch/owendeutsch.com

Pintoʼs Spinetail

Ciro Albano

Chirps

What we’re hearing from ABC members and friends.

Following Our Paper Trail

We were thrilled to receive so many positive comments on our spring issue, the first edition published with a new look and feel. Our readers found a lot to love about the revamped Bird Conservation, and shared some valuable feedback and constructive ideas that we’ve already taken to heart — even in the issue you’re now holding! Make sure to tell us what you think about this issue at abcbirds.org/MagSurvey.

Did you know that the paper we use makes a difference for birds? We work closely with our printer, Neyenesch Printers, a women-owned business based in San Diego, to select the most sustainable paper products available. Why? As a Sustainable Forestry Initiative partner, achieving these standards is our way of sharing stories about ABC’s work throughout the Western Hemisphere with you while doing the most good for birds. We use the most sustainable paper products, inks, and production processes we can, and we hope with some adjustments to our magazine’s binding, you’ll have a publication that’s as easy to read as it is beneficial for birds.

Readers React to Our Spring Issue

I love that as an organization you have altered everything about your magazine to make it sustainable but especially because you found a woman-owned facility! Your magazine has always been a great read:

quick-reading articles that provide all you need to know in a format that is very enjoyable, has excellent photography, and introduces your readers to birds, places, and issues over the entire planet.

— Mary Alice K.

I am more impressed with every issue as to the action and advocacy you work so hard on to save birds and their habitats — especially when they leave us and head to their winter areas! I doubt most people think about that other part of their lives. Your organization is one I support as best I can because you are so involved and active!

— JoAnne L.

I love reading about all of ABC’s great work and accomplishments and hopes for the future. Reading your magazine is like a balm for the birder’s soul. In this age of environmental degradation, habitat loss, and all the other many threats to birds and other wildlife, it’s so heartening to be reminded of all the good work and hopeful “wins” on behalf of birds that are also happening. — Jennifer G.

Editing is an A+, well written and organized, great thorough descriptions, but casual, interesting and understandable for the neophyte bird lover. — Don H. There’s a nice balance of beautiful pictures, information on birds and their tribulations, and some positive trends, and science that points out the importance of protecting bird habitats and populations, and ways to help in making that happen. It’s critical, I think that people see how

they can make a positive impact, and this magazine does a great job with giving that information. — Norm J.

I love the look (and feel) of the magazine. The design is very clean and easy to read, and the magazine feels like it is made of a high-quality stock of paper. I am a photography enthusiast who enjoys taking photos of birds, and overall I think the photos of birds in the magazine are outstanding. Great job to the team that worked on the redesign! — Richard A.

I was so impressed with Killian Sullivan’s article about adding five rare lifers, with the help and support of his parents. I especially liked his phrase “I looked toward my mom and could see my full smile reflected in her sunglasses.” Excellent writing considering that he was only 13! — Cynthia P.

Let’s hear from you!

Share your thoughts about our magazine, emails, or online content at magazine@abcbirds.org. Please include your full name and location. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. (Note: Opinions expressed are those of the authors.)

Sparkling Violetear

Owen Deutsch

Hope for a Future Free of Extinctions

Anyone with even a passing interest in birds probably knows the names of at least a few extinct species: Passenger Pigeon. Carolina Parakeet. Poʻouli. Atitlan Grebe. For those of us whose job is to conserve birds, the names of extinct species are haunting reminders of why we work in this field — to make sure no other species join those that have been lost.

Since ABC’s founding three decades ago, we have worked with local partners and national and regional governments to protect habitat for the rarest species in the Western Hemisphere. In that time, 18 likely bird extinctions have been averted in the Americas, and ABC and our partners contributed significantly to preventing six of these (including the Yellow-eared Parrot, pictured below).

In 2005, we helped establish the Alliance for Zero Extinction, a worldwide effort to identify the sites where species classified as Critically Endangered and Endangered on the IUCN Red List were restricted to just one location and to protect these sites. Now, a team of our researchers has published a study that identifies Critically Endangered, Endangered, and some Vulnerable birds in Latin America that have small populations and not enough protected habitat.

The study pinpoints the species that need the most help and the locations needed to avoid their extinctions — areas that amount to less than 0.1 percent of the overall Latin American landscape. We’re excited about the research because it offers hope for preventing further bird extinctions. (Learn more in an article explaining the study on page 26.)

Of course, another critical aspect of our work is helping to establish bird reserves. Since the late 1990s, we’ve partnered with dozens of other groups to create or expand more than 120 reserves in Latin America and the Caribbean (plus 11 more in the United States). Altogether, we’ve helped protect more than 1.1 million acres in 15 countries. Birds aren’t the only beneficiaries, obviously; these places also conserve mammals, insects, fish, plants, and other wildlife, as well as forest carbon.

The conservation gains from these reserves are at risk, however, if a particular site isn’t managed and maintained to help its wild residents thrive. That’s why, for the last decade, ABC and our friends at March Conservation Fund have operated the Latin American Reserve Stewardship Initiative (LARSI). It provides technical support and resources for partner groups throughout Latin America and is the subject of an important article on page 18. In addition, many ABC-supported reserves also benefit from bird tourism revenue, which has become a mainstay of bird reserve sustainability across the region.

Lastly, while we’re on the subject of Latin America’s birds, photographer Owen Deutsch and I recently produced a new book, Birds of the Tropical Andes. It celebrates the tremendous diversity and beauty of the birds across a vast swath of South America. You can read more about it on page 32.

Thank you for all your support for birds through American Bird Conservancy!

Michael J. Parr President

ABC helped the recovery of Colombia’s Yellow-eared Parrot after the species was rediscovered in 1999.

The Endangered Tanager of Bolivia’s High Andes

Shrubby mountain slopes in the Andes of central Bolivia are home to several endemic bird species, including the distinctive Cochabamba Mountain Finch.

The striking orange-rufous and gray bird, which has recently been shown to be part of the tanager family, measures about 7 inches long — about the same as North America’s Western Tanager. A nonmigratory species feeding mainly on seeds and insects, the mountain finch is found at elevations from about 10,000 to 12,500 feet. While it prefers dry forests on mountain slopes with Polylepis and alder trees and dense shrubs, it can also be found in mixed agricultural and forested areas.

Breeding takes place during the rainy season (December to March), and adult birds care for their offspring for many months after they leave the nest. Shrubs, bunchgrass, and ground bromeliads are often chosen for nesting, and while few nests have been studied, it appears that the bird typically lays only one or two eggs and produces one or two young per nest.

The Cochabamba Mountain Finch is named for the region where it lives — Bolivia’s Cochabamba department — and its population stronghold is Tunari National Park’s southern slope. The park encompasses the Tunari mountain range and remarkable biodiversity (including Geoffroy’s

Population: 270-2,700

IUCN Status: Near Threatened

Trend: Decreasing

Habitat: Valleys with shrubby woodlands and mixed agricultural and forested areas

Other Names: Monterita de Cochabamba (Spanish), Qoypita puka-q'ellitu (Quechua)

cat and vicuñas), and it is home to numerous Quechua communities. Asociación Armonía, one of ABC’s longtime partners in Bolivia, has been implementing a native forest restoration program for more than a decade with the participation of 37 local communities to protect and restore the ecosystems in which the mountain finch and other endemic species occur.

“These local stakeholders are the custodians of the watersheds and, therefore, key to ecosystem protection,” said Rodrigo W. Soria Auza, Executive Director of Armonía.

BirdLife International classifies the Cochabamba Mountain Finch as Near Threatened, while the Bolivian government considers it Endangered. BirdLife and the IUCN Red List estimate its population at 270–2,700. Soria Auza said no recent formal population count has been undertaken and that the true number is likely “closer to the lower end” of BirdLife’s estimate.

The new book Birds of the Tropical Andes, by ABC President Michael J. Parr and photographer Owen Deutsch, notes that the mountain finch can be found close to roads in the region. Parr suggests traveling birders search the Puente San Miguel area on the road from the city of Cochabamba to Tunari. Other species of interest in the area include the Giant Conebill, Tawny Tit-Spinetail, and Rufous-sided Warbling Finch.

Cochabamba Mountain Finch Poospiza garleppi

The Cochabamba Mountain Finch of western Bolivia displays a stunning mix of two colors: gray on most of its head and upperparts and orange-rufous on its forehead, eyebrow, crescents below the eyes, chin, and underparts.

John C. Mittermeier

Drones Deliver a Lifeline to Forest Birds in Hawai‘i

Drones equipped with specially designed biodegradable mosquito pods are helping to protect honeycreepers from extinction in Hawai‘i — and reduce the presence of harmful mosquitoes in the forests.

Non-native southern house mosquitoes spread avian malaria among the state’s native honeycreepers with incredible efficiency. The birds have little to no immunity to the illness, and the mortality rate is as high as 90 percent for species like the ‘I‘iwi.

Since 2023, the multi-agency partnership Birds, Not Mosquitoes (BNM), which includes ABC, has been using helicopters to release beneficial, non-biting male mosquitoes in the remote forests of Maui, following

years of rigorous study and regulatory approvals, and just started releases on Kaua‘i this February. These lab-reared males have a bacteria that occurs in nature, which results in infertile eggs when the males mate with wild females.

Over time, the mosquito population will decline, giving the embattled honeycreepers a reprieve.

Recently, BNM partnered with Drone Amplified and IS4S Orlando to develop an innovative pod system for the drones, which maintains a controlled temperature to ensure the survival of mosquitoes on the ground.

To maximize their efficiency, each drone is equipped with multiple pods. Like the helicopters, the drones must contend with challenging conditions and be able to

manage significant elevation changes, strong wind, and frequent rain across thousands of acres of remote, mountainous forest habitat.

This new step for BNM’s mosquito-control capacity comes at a critical time: Many of the 17 remaining honeycreeper species, including the Kiwikiu and ‘Ākohekohe on Maui and ‘Akeke‘e on Kaua‘i, are highly endangered. Reducing mosquito populations is paramount to safeguard their future.

Acknowledgement

ABC is grateful to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, BAND Foundation, Hawai'i Community Foundation, Animal Welfare Institute, Lemmon Foundation, Kay Hale, and other federal and private donors for their support of this program.

BirdsPlus Index Honored with Incubator Grant

ABC’s BirdsPlus team was selected to join the 2025 cohort of the Conservation Finance Alliance (CFA) Incubator program to help advance the BirdsPlus Index, which was the subject of an in-depth article in our Spring 2025 issue (page 18). ABC also received a $25,000 grant from the CFA to support the team throughout the incubation period. The program supports “conservation finance ventures that can generate a financial return and conservation finance concepts that lead to policy, regulatory, or nonprofit finance solutions,” according to the alliance.

The BirdsPlus team will benefit from mentorship, technical assistance, and global exposure through the alliance’s network. “Understanding, measuring, and reporting on biodiversity and nature impact is such an important part of conservation finance. We’re excited to demonstrate just how much birds can tell us about our impact on ecosystems and biodiversity in a quantitative, scalable, and accessible way with the BirdsPlus Index,” said Corey Martignetti, ABC’s Senior Director of Impact Investing.

Adam Knox (left), Robby Kohley (right)

Left A drone releases a pod containing beneficial mosquitoes over Maui.

Below The ‘I‘iwi is one of the native bird species that mosquito releases are intended to help.

Black-capped Petrel

Rare Seabird Sighting Offers Hope

Tiny Alto Velo Island, off the southern coast of the Dominican Republic, already boasts the largest breeding colony of Sooty Terns in the Caribbean. Now, it offers hope for one of the region’s most poorly known seabirds.

In late March, Brad Keitt, ABC’s Oceans and Islands Di-

rector, and colleagues from SOH Conservación spotted at least six Black-capped Petrels not far from shore. The Endangered species has a population estimated at little more than 1,000 breeding pairs. The petrels spend most of their life at sea, coming to land only to nest and returning each breeding season to just one island: Hispaniola.

On Alto Velo, which measures 0.39 square miles (1.02 square km), ABC and several

A New Pinyon Jay Plight?

The Pinyon Jay is found only in the woodlands of the western United States, specifically in pinyonjuniper, chaparral, and scrub-oak forests. In years when food from pinyon pine seeds is lacking, the birds may venture outside of their range. An unfortunate and emerging new threat is taking the songbird much farther afield: to pet markets in the European Union.

A recent paper published in the European Journal of Wildlife Research documents observations

of several Pinyon Jays in pet markets in Europe. The sightings were incidental, and more research is needed into the extent of the pet trade in the jay.

The species previously experienced severe population declines from habitat loss as pinyon-juniper forests were converted for grazing, and today these same forests are thinned in an effort to prevent fires. The paper’s authors call for increased protections for the smart and social jay, including listing it under the Convention on

partners are restoring habitat and removing invasive predators for the benefit of endemic lizards and seabirds.

The team’s sighting of the petrels is notable because observations are rare away from Hispaniola and because the birds were close to land — a virtually unprecedented encounter in the last 50 years. Their presence suggests that

a restored Alto Velo, one free from the introduced, non-native cats and rats that plague the petrels’ nests on Hispaniola, might soon serve as a safe space for the species to breed.

Acknowledgement

ABC thanks the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund for supporting work on Alto Velo.

International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in order to monitor potential trade of the species. In addition, Defenders of

Wildlife last year sued the Department of the Interior over delays to protect the jay under the Endangered Species Act.

Known Black-capped Petrel breeding range

Haiti

Puerto Rico

Jamaica

Cuba

Dominican Republic

Alto Velo Island

The Pinyon Jay is a muted blue corvid of the western U.S.

Brian Patteson (top), Tim Zurowski/Shutterstock (right)

Puerto Rico’s Plain Pigeon in Jeopardy

The once widespread Puerto Rico Plain Pigeon faces an uncertain future. Laid low by habitat destruction and hunting, and more recently, hurricanes, its population now hovers at an estimated 1,000 birds. A new study published in Bird Conservation International showed that the pigeon’s population has yet to recover from devastating losses following Hurricanes Irma and María, which ravaged the island in rapid succession in September 2017.

The study concludes that the chance of the population rebounding to its benchmark 30,000 individuals is highly unlikely, but a return to a population of 5,000 is within striking distance and would ensure population self-sustainability. The pigeon has recovered from hurricanes in the past, but without urgent conservation action, the fate of this genetically distinct subspecies remains unclear.

Three Wins for Bird-friendly Buildings

On a single night in October 2023, nearly 1,000 birds — mostly warblers, sparrows, thrushes, and others moving south after the breeding season — perished after colliding with the reflective glass facade of McCormick Place Lakeside Center in Chicago. The incident put McCormick Place in the national spotlight. ABC put a fullpage ad demanding action in the Chicago Tribune, and many others joined the outcry, prompting the building, long known for its outsized impact on birds by those monitoring collisions in the area, to finally take action.

Ahead of fall migration in 2024 and working with Toronto-based Feather Friendly, a company that makes scientifically tested collision deterrent products deemed “bird friendly” by ABC’s collisions testing program, McCormick Place installed markers along much of the building’s 120,000 square feet of exterior glass. Thousands of small, white dots spaced 2 inches apart break up the reflective surface, making the glass “visible” to birds. The $1.2 million project has paid off: Once the city’s most notorious bird-killing building,

bird deaths are down by 95 percent following the project’s completion.

Nearby Lake County, Illinois, made history as the county passed a firstof-its-kind bird-friendly building ordinance for residential construction, including new single-family homes. After working with ABC to identify county-owned properties prone to bird collisions and plan retrofits of problem buildings, the county set its sights on widening its impact for birds. Under the new policy, homeowners and building owners can select any type of glass they want, but any windows lacking full, external window screens must be treated with ABC-approved window retrofit products.

And we’re happy to report that bird-friendly design is in vogue: In May, the Michael C. Rockefeller

Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York reopened following a major renovation that replaced windows that were notoriously bad for birds. ABC worked closely with the glass designers to ensure a bird-friendly design. Under a 2020 New York City ordinance shaped by ABC input, all new buildings and major glass replacements must incorporate bird-friendly materials on glass. The reimagined wing is earning praise not only for the artwork it houses but for its construction. Featuring a massive window overlooking Central Park, the new design’s fritted glass helps birds avoid the building.

Acknowledgement

ABC is grateful to the Leon Levy Foundation, Dudley T. Dougherty Foundation, and to David Walsh for their support of our Glass Collisions Program.

The glass surfaces of Chicago's McCormick Place now feature Feather Friendly collision deterrent dots, making the building more visible to birds.

Plain Pigeon

Daniel J. Lebbin (top), Kaitlyn Parkins (bottom)

Tell Congress that Birds Matter

Despite bipartisan support for the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), the current administration is attempting to end the requirement that industries take available steps to avoid incidental killing of migratory birds, opening the door for millions of preventable bird deaths. Urge your senators and representatives to support legislation that restores MBTA protections for migratory birds: abcbirds.org/MBTA

Endangered Species Act at Risk

For more than 50 years, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) has provided the roadmap and resources that have been instrumental in bringing beloved species like the Bald Eagle and California Condor back from the brink of extinction. The power of the ESA pivots on the word “harm.” For decades, “harm” has included not just direct killing, capturing, and harassment of protected species, but also disruptions to their habitats, food sources, behavior, and other elements intrinsic to a species’ survival.

This spring, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) announced its intention to redefine “harm” under the ESA. The proposed change would narrow the definition of “harm” and remove habitat from the

conversation, protecting species only from those actions that would directly kill individuals (also known as “take”).

ABC opposes the proposed change and has submitted comments to FWS. For many of the 89 North American bird species currently protected under the ESA, the greatest threats to their survival are not direct harm but the downstream effects of habitat degradation or destruction, or changes to resource availability.

Currently, under the ESA, conservationists and resource managers are obligated to take the necessary steps to ensure species can rebound and prevent other species from sliding toward scarcity. The ESA has proven incredibly successful in its mandate to protect

species, due in large part to the protections it extends to the habitats species depend on for survival.

With this narrowed definition of “harm,” many of the ESA’s greatest conservation achievements would have been impossible. The Kirtland’s Warbler, once reduced to a population of only a few hundred birds, was removed from the endangered species list in 2019, its population rebounding thanks to

concerted, ongoing habitat restoration. The species was never seriously threatened by direct take, and if the proposed definition of “harm” had been in place, the Kirtland’s Warbler very well could have been lost.

The official comment period on the proposed definition change has closed, and FWS is required to review all comments before making a final determination, which is expected this summer.

Bald Eagle

American Redstart

Joshua Galicki (top), Larry Master (middle)

States Rein in Neonics, Help Horseshoe Crabs

Despite current challenges at the federal level, states across the U.S. are taking meaningful action for birds and habitats.

Maine’s legislature recently directed its state Board of Pesticide Control to formally study the impact of neonicotinoid-coated seeds on the environ-

ment. Supported by ABC, this action is an important first step toward regulating the use of the widespread insecticides, which have long-lasting, deleterious effects on birds and their ecosystems. And in Vermont, a ban on neonic use on ornamental plants and lawns took effect in July

More Bird Habitat Protected in Peru and Chile

ABC partners in Peru and Chile are celebrating two new protected areas.

In Peru, Nature and Culture International created a conservation corridor covering more than 45,000 acres of the unique Marañón inter-Andean dry forest ecosystem.

Known as the Cutervo Regional Conservation Area, it conserves important habitat while supporting local communities, improving ecosystem services, and contributing

thanks to a bill ABC helped become law last year.

ABC was proud to be part of the team that helped draft Connecticut’s Senate Bill 9. Recently signed into law and set to take effect in 2027, the measure bans neonics from being used on 300,000 acres of golf courses, turf fields, and yards, and it immediately limits a particularly harmful type of rodenticide, which is toxic to raptors and scavengers, to professional use only.

In New York and Massachusetts, ABC has been directly involved in moving legislation aimed at conserving horseshoe crabs — ancient sea arthropods whose eggs are a vital food source for migratory Red Knots. The overharvesting of horseshoe crabs for biomedical

testing is a leading factor in the knot’s decline.

New York’s legislature passed a bill empowering the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation to regulate horseshoe crab management through 2028 and prohibiting the harvesting of horseshoe crabs for commercial and biomedical purposes. In Massachusetts, legislators are advancing a bill that would temporarily pause horseshoe crab harvests, with an exception for the use of horseshoe crabs as bait in certain fishing operations.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to the Raines Family Fund, David Kozak, One Hive Foundation, and other supporters of our Policy and Advocacy Division.

to climate change mitigation. ABC will be supporting management of the area, which conserves a portion of the extremely small range occupied by the Marañón Spinetail, a Critically Endangered member of the Neotropical ovenbird family.

In Chile, Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile (ROC), with support from the International Hummingbird Society and ABC, began managing a microreserve

for Chilean Woodstar, a hummingbird numbering fewer than 400 birds. This is the third microreserve ROC is managing in the Chaca Valley, the last holdout of this Critically Endangered species. So far, ROC is managing 40 acres and restoring the area with natural vegetation to provide much-needed habitat for the tiny woodstar. With additional support from March Conservation Fund through the Latin American Reserve Stewardship Initiative, ROC is developing a management plan to

guide future actions in the reserve network.

On page 26 of this issue, we describe a new study about rare Latin American birds and their habitat needs; the spinetail and woodstar are among the 64 species that this research prioritizes for conservation action.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to the MarshallReynolds Foundation, Kathleen Burger, and Glen Gerada for supporting Marañón Spinetail conservation.

Gavin Shire

Horseshoe crabs move across an Atlantic coast beach.

Rare Hummingbird Prefers Streamsides

The Santa Marta Sabrewing, one of the rarest and least studied hummingbird species in the world, was so seldom spotted that it was lost to science for more than seven decades. The little jewel-toned hummingbird once held a spot in the top 10 “most wanted” list of the Search for Lost Birds, a collaboration between ABC, Re:wild, and BirdLife International. Now, three years after its rediscovery, the species is the subject of a study that sheds light on its life history and conservation status.

The Critically Endangered bird lives only in northern Colombia’s isolated Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains, where it may number fewer than 50 individuals. Many months of monitoring by researchers from Universidad Nacional de Colombia, SELVA, ProCAT Colombia, and World Parrot Trust

to form a small resident population along a single stream, and, the researchers write, “this raises hope for the survival of the species.”

the Indigenous landowners and collaboration in developing conservation measures,” they write.

with support from ABC — and in close collaboration with the Indigenous communities whose land is also sabrewing habitat — found that the bird is highly associated with streams, where males hold year-round territories and form leks. They also observed males in mid-elevation habitats (3,700–6,000 feet) for 16 consecutive months, “suggesting that the species might not be an elevational migrant, as previously speculated.”

The team’s only potential observation of the bird’s breeding behavior was a sighting of a female gathering a spiderweb, which could have been used for nest building. Researchers observed sabrewings consuming nectar from plants in five families — information that can help conservationists protect and restore habitat.

The birds studied seem

Still, the team is concerned about fires and forest clearing in the area, and they ask for patience from the public and the birding tourism industry for the development of a sustainable ecotourism strategy because the area isn’t ready for an influx of visitors. “Any further study and observation require the active participation of

The journal Bird Conservation International published the study online in April.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Kathleen Burger and Glen Gerada, Carole Turek, the Constable Foundation, Ornis Birding Expeditions, and Shelby Robinson for their support of Lost Birds and the sabrewing study.

Concern for Osprey in Chesapeake Bay

The rebound of the Osprey after the banning of DDT in the 1970s was a major conservation success. But recently in certain parts of Chesapeake Bay, Ospreys are reproducing at a rate even lower than before the ban. The culprit this time is the harvest of Atlantic menhaden, a small, oily fish that serves as the base of the food chain for seabirds, larger fish, and marine mammals. This cornerstone of the Osprey diet is growing scarcer, causing young Ospreys to starve.

One company, Omega Protein, harvests millions of pounds of menhaden from the bay. The fish are “reduced” into fish meal and oil for pet food and salmon feed. Through

its lobbying, the company has blocked efforts by advocates, including ABC, to curb Omega Protein’s activities in Chesapeake Bay within Virginia, the only East Coast state that still allows menhaden reduction fishing practices. ABC is working with stakeholders to ensure a sustainable harvest.

John C. Mittermeier (top), Michael Stubblefield (right)

The male Santa Marta Sabrewing is an iridescent blue and green hummingbird. Females are grayish-white below with shining green upperparts. The Critically Endangered species may number fewer than 50 individuals.

Osprey

The Stopover

Where Sand Meets Sky

On the edges of oceans and seas, the sandy beaches and wind-carved dunes of the Americas breathe with a quiet, ancient rhythm. Here, sun and saltwater shape a shifting world, never the same from one tide to the next. Grains of quartz and shell mingle on the shore, sculpted into ridges and hollows by the wind’s unseen hand. Amid this austere beauty, life stirs — fragile, resilient, and wild.

The dunes rise like waves, cradling sea oats, beachgrass, and the soft-footed tracks of travelers. These hills of sand are not barren; they are sanctuary. In the early light,

the Piping Plover tiptoes across the beach, pale as foam and just as fleeting. Least Terns wheel above, their cries sharp as salt spray, while Black Skimmers trace the surf with knifepoint grace, slicing air and water alike.

Each spring, the dunes welcome Snowy Plovers to nest in shallow scrapes, in which their eggs are camouflaged in speckles and subtle hope. Wilson’s Plovers patrol the tide line, wary but determined. Ghost crabs dart, shells glinting, and the breeze carries the wild music of gulls and Sanderlings.

On many coasts, sea turtles clamber ashore, carving paths through moonlit dunes where shorebirds rest. These beaches are more than places of leisure — they are living, breathing margins between two worlds.

Conservationists work to ensure that beach-combing birds and other wildlife have the habitat they need. In Texas, for example, ABC and four partners work together to monitor plovers, terns, and skimmers. Along with land managers, we protect certain beaches and dunes, especially in summer, when the birds raise their young. We also reach out

Sarah Belles (sand dune), Greg Homel/Natural Elements Productions (tern), Paul Rossi (plover)

to local communities about keeping beaches safe for wildlife, and the SPLASh program removes plastic and other litter from shorelines.

In places where sand meets sky, the birds and their wild kin remind us to care.

abcbirds.org/BeachVisit

Beaches and sand dunes, such as the San Luis Pass Galveston Beach on Galveston Island, Texas, provide important habitat for birds such as the Least Tern (above) and Piping Plover (below).

Lulu’s Tody-Flycatcher

Owen Deutsch

For Birds — Forever

Our unstoppable drive for bird conservation results, even in the face of adversity, is the essential element that motivates American Bird Conservancy. We know it motivates you, too.

Our shared determination to act on behalf of birds is inspired by wonder: Birds surprise us and delight us; they motivate us to learn, to explore, and to connect with others. We believe wonder is best when shared, and we are committed to helping others experience the same excitement that buoys our commitment to conservation.

Science guides our work, pointing the way to the species and habitats most in need — and to the best ways to achieve lasting bird conservation results. We turn theory into action, defining best practices and working with a diverse network of partners to adopt and adapt those practices — wherever and however research tells us we can most effectively help birds across the Americas.

Because at ABC, we believe that conservation is a human responsibility. Beyond the wonder birds inspire in us — and beyond any value birds provide to people — we believe that birds and their habitats have inherent value, independent of their benefit to humanity. Our obligation is to reduce and reverse the damage done to birdlife and bird habitats, focusing on those most at risk of disappearing forever. It is the only decent thing to do.

Birds are not only our business; they’re the beating heart of our organization. And so are you.

Just as a diversity of species and natural processes makes nature resilient, ABC recognizes that our organization — and birds — thrive when we embrace diverse perspectives. When we work in partnership with people and communities across the Americas. When we welcome everyone who cares about birds.

Because we accomplish more for birds and their habitats — together.

Please give generously today so that together, we can continue to take bold action for birds across the Americas. Thank you for caring about birds.

Help conserve birds and their habitats by using the enclosed envelope, scanning the code, or visiting abcbirds.org/ForBirds

The Kaempfer's Woodpecker, a Vulnerable species found only in central Brazil, has benefited from recent firefighting efforts supported by the Latin American Reserve Stewardship Initiative.

Caio Brito

Lasting Stewardship for Bird Reserves

How a 10-year-old initiative is helping bird reserves in more than a dozen countries remain sustainable — and focused on conserving rare birds

by George E. Wallace

Anyone who owns a home knows that upkeep is required — from routine cleaning tasks to occasional calls to an electrician, plumber, or other pro for more involved jobs. The same principle holds true for nature reserves. Once land is established as a reserve, it needs stewardship support for staffing, habitat management, infrastructure, and the like.

The alternative is neglect. After all, insufficient planning and shortages of capacity and resources available to the organization managing a protected area can cause it to fail.

ABC and our partners have been in the reserve business for more than a quarter century: Reserves are the first line of defense against bird extinctions, and they provide crucial refuges for both migratory and resident bird species, as well as scores of insects, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and plants. Before my retirement, I was involved with many land protection actions at ABC, and it’s one of the truly energizing parts of conservation work. With each piece of land conserved, it’s tempting to pump your fist and exclaim, “we did it!” And I assure you, we did — many times.

In fact, we celebrated “victory” with our partners on more than 600 tracts of land at 120 protected areas spanning over 1,140,000 acres in 14 Latin American countries. We accomplished this by working with 55 partners to buy land, secure easements and concessions, create community reserves and regional protected areas, and more. The majority of the reserves are owned and managed by in-country nongovernmental conservation organizations (NGOs), though some are community or publicly owned.

Then came the work to manage the reserves — to ensure that the lands we helped to protect actually work to prevent bird extinctions and maintain healthy populations. ABC has long believed that building capacity in the conservation movement is the foundation on which successful conservation is built, and we knew that new reserves would need ongoing management support.

So, as our land protection work gained steam starting in 2004, we looked for support to increase reserve sustainability in tandem with fundraising for land purchase. We found en-

lightened donors who understood the need for longer-term support for our partners. However, it was a constant struggle to keep this funding flowing, as many awards were one-year grants or from foundations that directed limited funding to new applicants, changed their priorities, or disappeared altogether.

A deeper problem also arose: While protecting land is easy to understand and attractive for donors, many of the activities needed to sustain reserves and their NGO stewards often are not. The pool of funders interested in supporting basic needs, like computer backup systems, training in fundraising, or support for websites or vehicles, is exceedingly small.

And sometimes the needs may be ones that partner organizations are reluctant to admit they have — such as financial and human resource training to prepare financial reports, budgets, forecasts and cashflow projections, job descriptions, and performance reviews. Even stickier, an organization may be facing issues that they fear could scare off donors, including governance challenges, budget deficits, and delegating roles and distributing responsibility from founding leaders to new staff as organiza-

This map shows the 13 countries where bird reserves are benefiting from ongoing investment to ensure they fulfill their purpose: preventing bird extinctions.

tions grow and mature. Yet, meeting all of these needs is essential for organizations — and their work — to succeed. Leaving these obligations unmet means putting our reserves at risk.

By 2014, we knew we required a program that would deliver more consistent technical support and resources to ABC partners. Thankfully, that need aligned with the goals of March Conservation Fund (MCF), a San Francisco-based foundation that supports land conservation and stewardship, research, and education. A year later, ABC and MCF launched the Latin American Reserve Stewardship Initiative (LARSI). Now, a decade later, LARSI has provided grants totaling more than $3.8 million in support of 29 conservation NGOs working to protect more than 70 reserves in 13 countries (see sidebar, page 23). The following case studies illustrate the wide variety of activities supported by LARSI as well as its reach and impact.

A Turning Point in Peru

In 2005, Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos (ECOAN) and ABC embarked on an ambitious plan to protect pristine forests bordering the 450,000-acre Bosque de Protección Alto Mayo in northern Peru. This effort would provide a barrier to agricultural expansion from the west in the already-threatened protected area and conserve habitat for the amazing Longwhiskered Owlet (listed as Endangered at the time, since downlisted to Vulnerable to extinction) and over 560 additional bird species.

It was a huge leap for ECOAN, whose activities at the time were concentrated in the Vilcanota range of the Andes near Cusco in southern Peru. Ultimately, with ABC support, the group purchased 42 properties to create the Área de Conservación Privada Abra Patricia-Alto Nieva (Abra Patricia) spanning 8,226 acres and securing a conservation concession (akin to a longterm lease) from the Peruvian government for another 16,557 acres. In addition, ECOAN and ABC secured a 95-acre easement on an important tract of land (Huembo) for the spectacular Marvelous Spatuletail hummingbird in the nearby town of Pomacochas.

At both sites, ECOAN constructed ecotourism lodges for visiting birders and other naturalists to generate income at the reserves. While ABC

secured grants to buy land, build lodges, and hire staff, LARSI provided support over eight years, from 2015 to 2022, for an array of activities that put the reserves and ECOAN on firmer footing. LARSI contributed to lodge and kitchen upgrades, installation of solar panels and a septic system, and needed maintenance.

Importantly, LARSI supported salaries for staff at Abra Patricia and Huembo during the COVID-19 pandemic. LARSI provided similar support during the pandemic to other conservation NGOs.

“LARSI’s support marked a turning point in ECOAN’s history,” said Adrian Torres, ECOAN’s Director of Conservation and Development, whose position was also launched with LARSI support. “It wasn’t just a series of grants — it was a lifeline that arrived at a moment of immense challenge and transformation. From 2015 to 2022, LARSI accompanied us through critical stages of growth, helping us strengthen our flagship reserves — Abra Patricia and Huembo — and elevate them to internationally recognized birding destinations. With LARSI support, we improved infrastructure and services, promoted these sites at international birding fairs, and increased our visibility in the global ecotourism community.”

“The systems, capacity, and resilience we developed thanks to LARSI have shaped the organization we are today,” added Constantino Aucca Chutas, ECOAN’s President. “It was more than financial support — it was trust, vision, and partnership. We carry that legacy forward in every step we take to protect Andean forests and empower local communities.”

A critical reserve for Peru's Marvelous Spatuletail is protected and well managed thanks to conservation group ECOAN and the Latin American Reserve Stewardship Initiative.

Conservation and Cattle in Bolivia

In 2008, ABC began working with Asociación Armonía to develop the Reserva Barba Azul to protect an important nonbreeding area for the Critically Endangered Blue-throated Macaw in the Beni Savanna of northern Bolivia. Known also as the Llanos de Moxos, the area was extensively farmed in pre-Columbian times with raised fields, causeways, canals, and thousands of forested mounds. While nearly all signs of this occupation are gone, the “tree islands” remain, and their motacú palms provide important macaw roosting and feeding areas.

ABC and other organizations supported the purchase of more than 26,000 acres of a former cattle ranch to create the reserve and construct a manager’s house and a basic field station for visiting researchers. Bolivian law sets a minimum required level of agriculture that must be conducted on private reserves, which forced Armonía to develop a plan for cattle ranching that would fulfill the legal requirement while not undermining the original conservation objectives. This turned out to be fortuitous in a way: If the group could master a low-impact method of cattle grazing that was less reliant on destructive burning on a portion of the reserve, it could potentially pay for reserve operations.

To fulfill this plan, LARSI supported Armonía for seven years, concluding in 2021 (before the organization returned to LARSI in 2025 for other needs). LARSI helped Armonía lay the groundwork for the cattle program with the development of an organizational strategic

plan, a communications strategy, and a conservation plan for Barba Azul with an integrated “Eco-friendly Cattle Business Model.”

Armonía staff received training in cattle management, and a ranch manager and assistant were hired. A workshop was held with the regional cattle ranchers’ federation to attract support from local ranchers. LARSI funded the repair of many existing facilities, including corrals and fencing around paddocks and the perimeter of the reserve. LARSI also supported the creation and maintenance of fire breaks, narrow strips of land cleared of all vegetation to prevent fires from spreading, to protect the reserve from fires spreading from neighboring ranches.

“LARSI then provided crucial funding to purchase the first 100 cattle — support that is typically very difficult to secure,” said Tjalle Boorsma, Armonía’s Conservation Program Director. “The herd has since grown to over 1,000, managed to maintain a diverse and heterogeneous landscape that benefits a wide variety of grassland-specialist birds and threatened wildlife.”

In addition to helping launch the cattle program, LARSI also funded the hiring of a tourism and marketing coordinator to increase visitation to Armonía’s Barba Azul Reserve, along with its Laney Rickman Reserve for Blue-throated Macaws and the Red-fronted Macaw Reserve. “LARSI has played an important role in Armonía’s institutional strengthening, particularly in areas like fundraising capacity and conservation strategy development,” said Rodrigo W. Soria Auza, Executive Director. “Armonía has nearly tripled its annual operating budget since joining the LARSI program in 2015, and LARSI increased our capacity to generate funding.”

LARSI by the Numbers

Battling Blazes in Brazil

The Cantão ecoregion in east-central Brazil is where Instituto Araguaia, ABC, and others have worked to protect Araguaia’s 1,482-acre Cantão-Cerrado Corridor, which lies in the eastern buffer zone of Parque Estadual do Cantão. The corridor encompasses the last remaining intact lowland cerrado forests in the region, preventing them from being converted to soybean agriculture. The reserves within the corridor, known as Guaíra, Lago do Campo, and Canto do Obrieni, are the only strictly protected areas in the entire, vast lowland cerrado, but their protection requires constant vigilance by Araguaia in the face of recreational hunters, armed gangs of fish poachers, and, above all, the constant threat of fire. This is the land of the Vulnerable Kaempfer’s Woodpecker, which is declining throughout its small, fragmented range.

LARSI’s support of Araguaia began in 2021 and is now in its fifth year. Araguaia has used most of its funding for basic reserve needs (including guard salaries, patrols, and vehicle and other facilities maintenance), construction of a visitor center in the town of Caseara, an exchange trip during which Araguaia personnel visited other ABC-partner reserves, and development of ecotourism. However, LARSI support for fire management and prevention has arguably been the most dramatically impactful in

terms of protecting the reserves.

All fires that occur in this region are set by people, either accidentally or intentionally. During 2021 and 2022, Araguaia personnel created miles of fire breaks and conducted controlled burns, work that is a year-round commitment in the face of ever-worsening fire seasons. Also in 2022, PrevFogo, the firefighting agency for Brazil’s federal protected areas, prepared fire management plans for each of Araguaia’s reserves — work that LARSI funded.

In June 2022, Araguaia’s LARSI-supported fire preparation was put to the test with a fire that threatened the Canto do Obrieni Reserve and took the team three days to put out. On August 28, a fire started at a ranch bordering the Guaíra Reserve, and two days later, another fire moved into the area between Guaíra and Canto do Obrieni. Araguaia fought these fires continuously day and night for the next 12

Bolivia's Blue-throated Macaw is one of the Critically Endangered bird species that benefits from LARSI support.

days, until, with help from local ranchers, the Caseara municipal fire brigade, and PrevFogo, they were finally extinguished.

Following firefighting training from PrevFogo in 2023, Araguaia was again challenged in 2024, the worst year for fires in Brazil’s history. In August, Araguaia staff courageously fought and contained fires that repeatedly threatened the Guaíra Reserve, and again in September they confronted a large fire that came perilously close to the Lago de Campo Reserve.

Araguaia has not lost any reserve land to fire, thanks to support from LARSI for fire prevention and control. This is vitally important for Kaempfer’s Woodpecker, a bird that depends on tall dead nesting trees that would certainly be eliminated by fire in the cerrado forest. Doubly bad would be the loss of bamboo thickets upon which the woodpecker relies almost exclusively to forage for ant larvae.

As Araguaia’s leaders, Silvana Campello and George Georgiadis, explained: “With repeated uncontrolled fires sweeping through the entire cerrado region, such species will only survive in refuges where fires are kept out. This requires not large projects with an expiration date but moderate and reliable support, year after year, that enables an experienced and committed team to be built and maintained, fighting fires year after year for as long as there is no one else to do it. This is exactly the kind of support that LARSI has given Instituto Araguaia.”

Finding a Partner

A driving force behind LARSI is Ivan Samuels, MCF’s Executive Director. In 2014, Samuels had been on the board of Fundación de Con-

servación Jocotoco, one of ABC’s long-time partners in Ecuador, for six years. MCF had supported a range of needs at Jocotoco, from land purchases to core operations, and he noticed that many donors would support key land acquisitions but then move on, as if the work was done, when in fact it had just begun.

Knowing from his Jocotoco board experience what was involved in stewarding the land once acquired, Samuels worried that many NGOs in Latin America did not have the tools and resources to ensure long-term protection for their reserve networks. “We were already donors to ABC,” said Samuels. “I had a publication from ABC called the Latin American Bird Reserve Network, profiling the conservation investments ABC had made with many organizations across the region. That was the spark. I realized the network was a platform from which we could deploy resources across the NGO landscape to help partners in Latin America become more sustainable, adopt better financial controls and governance practices, and ultimately better manage their growing reserve networks. ABC was the ideal organization to implement such a

Workers with Instituto Araguaia in Brazil train to extinguish fires in 2023. A year later, they defended two nature reserves from large fires.

A Guide for Reserve Managers

In 2022, LARSI supported the publication of Sustainable Nature Reserves: Guidelines to create privately protected areas authored by Alberto Campos, Lucia Guaita, Bennett Hennessey, and Marc Hoogeslag and published by IUCN-National Committee of The Netherlands and ABC. Drawing on case histories and testimonials by experienced

in-country conservation practitioners, the 108-page document addresses key challenges to reserve management, such as cost control, engaging communities and other stakeholders, and many others. The publication is available for download at abcbirds.org/SNRGuide

program because they already had established relationships with these partners.”

The LARSI program follows a re-granting model: MCF provides funding to ABC. ABC requests proposals from partner organizations in which the partners identify strategies and actions to make their organizations and reserves more secure. ABC then enters into direct agreements with 10 or more partners each year to help partners address their needs.

It’s a powerful multiplier for MCF, allowing it to support more organizations than it could on its own while taking advantage of ABC’s ability to work one-on-one with each grantee, often matching with additional funds raised from other sources for specific projects. For ABC, it provides a steady stream of support for a wide variety of partners, and partners often stay in the program for multiple years, giving them the ability to address complex problems or develop programs in phases until they reach fruition.

Partners that leave the program after one or more years of support can return to LARSI to address new challenges. Said Amy Upgren, ABC’s Director of International Programs and LARSI program coordinator, “We’ve had partners receive LARSI funding for up to 10 consecutive years, and, at any given time, we have up to 14 partners working on their own specific projects in support of reserves that we have invested in. Working with so many partners on many different issues at once is amazingly powerful and rewarding.”

Upgren added, “Another important role that ABC fills in the LARSI program is that of facilitating connections between partners, especially those facing similar challenges. We have funded partner visits to other LARSI-supported reserves, which have led to idea exchanges across partners and countries,” noting that ABC hosted a partner summit in 2019 in Virginia and is planning another in August in Colombia.

Looking Ahead

The wide variety of projects, personnel, and challenges that have been addressed with LARSI support is a testament to the complexity of protecting land for threatened bird species and other wildlife. “We fund things that are hard to fundraise for,” said MCF’s Samuels, “things that other donors may not find exciting. But through critical thinking with our partners, these investments can jumpstart whole new opportunities in fundraising, ecotourism, or communications. It’s rewarding when we help fund a new position and that person becomes a critical part of their team, leveraging new sources of support, bringing in new partners, and effectively making their organizations more sustainable. Sometimes it takes years for the full impact to be realized, but we’ve paved the way for success.”

Daniel Lebbin, ABC’s Vice President for Threatened Species, added: “LARSI represents the best kind of collaboration in fundraising and conservation. We are more confident in creating new reserves, knowing we have the potential of LARSI support for those areas in their early years and for local conservation groups to lead this global effort in their countries. We are grateful to March Conservation Fund for the partnership, and we look forward to continuing to foster lasting conservation results together.”

George E. Wallace recently retired after 18 years with ABC. In that time, he served as Vice President for International Programs, Vice President for Oceans and Islands, Chief Conservation Officer, and Director of International Programs and Partnerships. He is now an ABC Ambassador.

The spectacular Seven-colored Tanager of eastern Brazil is a focus of conservation work by SAVE Brasil, a group supported by LARSI.

Instituto Araguaia (left), Ciro Albano (above)

Filling the Gaps

ABC research shows which Latin American birds lack protected habitat — and how much must be conserved to prevent their extinction

by Molly Bergen

Atop a windswept island in the sky in southwestern Ecuador, a bird with a startlingly blue throat and teal cap flits among the bright orange blossoms of chuquiragua shrubs. The bird nests under rocky outcrops and in caves, its alpine habitat isolated from the rest of the Andes by deep arid valleys. Only described to science in 2017, the species was named the Blue-throated Hillstar, and at the time, its entire home was outside any kind of nature reserve. Conservationists were concerned that various threats — fires set to encourage cattle grazing, planting non-native pine trees for

timber, and other practices — might inadvertently cause the bird’s extinction.

The hillstar was assessed as Critically Endangered due to these habitat risks, combined with a small population estimated at only 80–110 mature individuals. Since then, Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco (with support from American Bird Conservancy) has acquired and protected 1,520 acres of the species’ habitat in the Cerro de Arcos Reserve (home to about 32 hillstars) and engaged local communities in conserving an additional 2,686 acres of adjacent land for the bird.

A Blue-throated Hillstar feeds on a chuquiragua flower. The Ecuadorian endemic hummingbird will benefit from a new study about rare birds and their habitats.

Within Jocotoco’s Cerro de Arcos Reserve, managers are working to improve habitat by planting chuquiraguas — one of the bird’s main sources of food. By conserving the hillstar’s habitat, Jocotoco and neighboring communities are giving the bird its best chance at long-term survival. But how much habitat is needed for the hillstar, and what about other species in similar peril?

Habitat is Key

Birds need habitat to thrive, and the loss and degradation of habitat is the main driver endangering bird species with extinction today. Habitat loss is particularly acute in the American tropics, where lots of bird species (many of which have small ranges) face severe pressure as natural vegetation is converted to farms, pastures, or other uses. For decades, ABC has worked with local conservation organizations to establish, expand, and steward bird reserves, with a goal of preventing bird extinctions. (Read more about reserve management, page 18.)

“Most of the threatened birds of Latin America are facing habitat loss,” said Daniel Lebbin, ABC’s Vice President of Threatened Species. “Protecting habitat is the most important thing we can do to help ensure their survival.”

To prevent the extinction of Latin America’s most threatened birds, ABC aims to ensure that each of the species most at risk has at least one well-managed protected area that safeguards a minimal amount of habitat sufficient for survival. Accomplishing this requires asking (and answering) questions like the ones asked about the Blue-throated Hillstar: How much is enough? Which bird species continue to lack sufficient levels of protected habitat, how much additional habitat protection do these species need, and where could new reserves be located to most efficiently fill these needs?

The answers came in the form of ABC’s “gap analysis,” a new study by ABC scientists (available at biorxiv.org and abcbirds.org/GapAnalysis), that mapped the habitat of 149 of the most threatened species in Latin America and overlaid those maps with existing reserves — providing an estimate of how much habitat was protected. Remarkably, the majority of species met their minimal protection goals. For the species that are under-protected, less than 0.1 percent of the overall Latin American landscape would need to be protected to achieve the targets. The fact that we can prevent many extinctions by protecting a small, strategically selected amount of land is encouraging to conservationists.

The Blue-throated Hillstar’s range in Ecuador’s Cerro de Arcos is a windswept habitat known as páramo, an Andean ecosystem of boggy grass and shrublands studded with evergreen plants, mosses, and cacti.

Michael Moens

Mapping Goals

Most field guides to bird identification have range maps for each species, and the world’s protected areas are mapped online at the World Database of Protected Areas, so it would seem easy to overlay these maps of birds and reserves to see which species fall outside the existing reserve network. In fact, it was not so simple!

One problem was that existing maps were not precise enough, and taking them at face value could mean falsely predicting that birds were protected in reserves that did not actually support their habitat. So, ABC researchers looked at the most threatened species from Mexico through South America (excluding the Caribbean) ranked by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable (for the latter category, using the most stringent criteria of having populations less than 1,000 individuals or small ranges under 20 square kilometers). This resulted in the set of 149 species (after excluding a few species that had not been observed in at least a decade and a seed-finch with unclear taxonomy).

They then re-mapped the habitat for each of these species. The 149 birds identified in the study were nonmigratory, which isn’t surprising. “Resident species tend to have more restricted distributions than migratory species and, therefore, are more prone to be impacted by threats,” said Marcelo Tognelli, an International Project Officer for ABC and the lead author of the study. To create the most accurate

maps possible of each species’ habitat, the ABC team started with existing range maps, added information on occurrences from eBird, and trimmed the maps to the appropriate habitat and elevation range of the bird. The resulting maps (called Areas of Habitat) were much more precise and suitable for further analysis.

Equipped with improved maps, the team overlaid the boundaries of existing protected areas to assess how much habitat (if any) of each species is currently inside reserves. “This gave us a more accurate picture of how much protected habitat each species currently had, but we still needed to understand if that protected area was sufficient to support the species,” Tognelli said.

To determine if the amount of habitat inside existing reserves was “enough,” the researchers set minimum conservation targets for each species using two methods:

First, they set a population-based goal to protect enough habitat to support 1,000 mature individuals (or the bird’s total population if less than 1,000) by multiplying the population number by an estimate of their average territory size. This minimal target, designed to safe-

guard against the highest risk of extinction, relies on the assumption that the birds actually are present within the mapped habitat.

Second, to be a bit more cautious and to help ensure longer-term conservation success, the researchers estimated another target based on the percentage of habitat protected. It uses a sliding scale aimed at protecting 100 percent of habitat for species with the least habitat remaining (under 50 square km), and then decreased it to a minimum of 4 percent for the species with the largest amounts of habitat (20,000 square km and up). This approach

Jaqueira Silvia Linhares (top), Ciro Albano (middle)

A Few Species Most in Need

— conserving a small amount of a species’ large range — is not uncommon for conservation biologists and amounts to a lot of acres as a protection goal.

Finally, ABC scientists identified priority areas for conservation by looking at where suitable habitat exists for the target species outside of protected areas. Using a “prioritization analysis” method, the researchers determined which areas, if protected, would conserve the habitats of multiple threatened bird species to most efficiently meet the goals of all species.

Of the 149 species assessed, 93 percent met their population-based target needed to prevent their imminent extinction. Only 10 species fell short (see list, page 30). Five are hummingbirds, including the Blue-throated Hillstar that Jocotoco and ABC are working to protect.

“Hummingbirds are extreme when it comes to being a bird, in every way,” said Lebbin. “They’re some of the smallest birds. They have the fastest metabolisms. They have lots of extreme aspects of their biology, but part of this is that they also have a lot of endemism, a lot of smallrange species.”

Such small ranges can make species especially vulnerable to habitat

Future Studies Planned

While the new study described in this article is a significant step forward for conservation in Latin America, the authors note that additional research is needed to paint the full picture of threatened birds in Latin America and how best to protect them. Next steps include feasibility studies to develop projects to

loss due to human activities. Take the Chilean Woodstar, a hummingbird native to northern Chile in one of the world’s driest deserts. “The region looks like a moonscape,” Lebbin said, “but then you have these stream valleys that bisect this arid desert, and in the ephemeral streams, there is vegetation. That’s where this hummingbird lives, at the most extreme end of where a hummingbird can survive. And of the four main valleys in Chile where the species was once found, the northern two have been almost completely converted to enclosed greenhouse agriculture. So now the Chilean Woodstar survives only in the two southernmost valleys. We’ve worked with local partners to protect some small refuges there, but it’s very challenging because the areas along the streams are the only arable lands for miles around. So

establish and expand new reserves to cover species not meeting their targets in Latin America. They also want to extend this study to the Caribbean, where they will need to use different kinds of targets and habitat mapping methods due to regional differences from the mainland.

Rare birds from Brazil that stand to gain from the study include Pernambuco Foliagegleaner (lower left), Orange-bellied Antwren (upper left), White-collared Kite (above), and Alagoas Tyrannulet (upper right).

Ciro Albano (left), Gabriel Caram (right)

Situation Critical

An ABC analysis found that these 10 Latin American bird species fall short of targets for their population and protected habitat to prevent extinction. A further 54 species do not meet habitat targets, resulting in a total of 64 top priority bird species. See the full list at abcbirds.org/GapBirds

the land prices are very expensive.”

(Read more about the woodstar in “Bird Calls,” page 12.)

For the area-based targets, 64 species — including the 10 that don’t meet the population-based target — did not meet habitat protection goals. Most of these species are found in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil, and smaller numbers are in Panama, Venezuela, and Chile.

As for priority conservation areas, the researchers identified about 6,300 square miles (16,360 square km) as most critical to conserve these 64 species — an area that collectively is only 0.1 percent of the overall Latin American landscape, nearly the same size as the land area of Hawai‘i.

Many of the priority areas for protection are quite small. For example, the research found that Ecuador’s Blue-throated Hillstar could likely avoid extinction if an additional 157 acres of its habitat were protected. (More is better, of course!) Another priority conservation area can be found in northeastern Brazil — an unprotected 13,000-acre forest near the town of Murici in the state of Alagoas. Protecting this forest would help conserve nine bird species that do not meet their minimum conservation targets by adding an average of 11.1 percent to their collective Area of

Mexico: Short-crested Coquette, Oaxaca Hummingbird

Ecuador: Blue-throated Hillstar, Lilacine Amazon, El Oro Parakeet, Pale-headed Brushfinch

Peru: Gray-bellied Comet, Marañón

Antshrike, Little Inca Finch

Chile: Chilean Woodstar

Habitat. (The nine species are Forbes’s Blackbird, Pernambuco Foliage-gleaner, White-collared Kite, Scalloped Antbird, Alagoas Antwren, Alagoas Tyrannulet, Pinto’s Spinetail, Orangebellied Antwren, and Long-tailed Woodnymph, which are all classified on the Red List as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered.)

Protecting the prioritized habitats required to conserve the 64 species would do much more than benefit birds: The sites overlap significantly with habitat for other threatened species. For example, the priority areas overlap with 108 Key Biodiversity Areas and 29 Alliance for Zero Extinction sites, which highlight the importance of

these areas for threatened amphibians, reptiles, mammals, freshwater fish, and other species found nowhere else.

Progress is Achievable

While the study highlights remaining conservation needs, it also highlights progress already made. As mentioned, of the 149 species assessed, 93 percent met the population-based target to prevent their imminent extinction. But even when the more cautious, area-based target is applied, more than half (57 percent, or 85 of the 149 species) already have sufficient protected habitat to meet the goal. Conservation of these exist-

Stephen Jones

The Long-tailed Woodnymph of eastern Brazil may gain more habitat thanks to the recent study.

ing reserves must be maintained, but “it might be surprising that the news is so positive,” Lebbin said.

Conservationists have made great progress to bring some birds back from the brink, and those efforts continue. ABC has already supported 55 Latin American partners to establish or expand 120 protected areas spanning over 1,140,000 acres in 14 Latin American countries — benefiting many of the Americas’ most endangered birds.

In one heartening highlight, ABC has worked with Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco in southern Ecuador to expand the Yunguilla Reserve for the Pale-headed Brushfinch. With a global population of about 240 birds, the reserve protects 204 individuals. Thanks to these effective efforts, the species was downlisted in 2011 from Critically Endangered to Endangered. “When this brushfinch was first rediscovered in 1998, after 29 years of no documented observations, there were thought to be only 5–15 pairs in the Yunguilla Valley,” Lebbin said. “Now,

through land purchases, managing reserves, Jocotoco's efforts to control other threats, that small population initially protected by the reserve is growing and expanding beyond its boundaries — prompting a need to conserve more land.”

“The gap analysis study confirms that ABC and our partners are already working to conserve habitat for many of the species that need it most. For these species, we just need to keep protecting a bit more habitat,” Lebbin added. “We can begin to provide protective coverage for all the species prioritized if we maintain our current efforts and add three more species per year for the next 10 years. This is a lot, but it’s very doable if sufficient funding becomes available.”

ABC is already stepping up to meet this need and will launch new habitat protection projects this year to conserve habitat for underprotected species. For example, in a new project launching this year, ABC and partner CONBIODES will work with Indigenous communities to establish voluntary reserves for the Oaxaca Hummingbird — a species new to ABC ’s conservation efforts and one that is almost entirely absent from existing reserves.

Similarly, in Peru, ABC will soon work with Nature and Culture International-Peru to manage and establish protected areas for birds endemic to the Marañón River valley, including the Little Inca Finch and Marañón Antshrike.

With dedication and sufficient resources, minimum habitat targets can yet be met for the 64 species most in need of conservation. That’s the good news. “We know what the species are, and we know where to find them.

We know what habitat to protect to ensure their future,” said Tognelli. “That’s the power of this research. All that’s left is to secure the funding and political will to do the work.”

Molly Bergen is a freelance writer and editor with more than 16 years of experience writing about climate, wildlife, and community-based conservation. Learn more about her work at molly-bergen.com.

If you (or someone you know) wants to support the work to secure and expand ABC’s network of reserves, please contribute to our Bird Habitat Protection Fund. abcbirds.org/BHPF

Species that currently fall short of targets for population and protected habitat include Chilean Woodstar (left) and Pale-headed Brushfinch (right).

Rich Lindie/Shutterstock (left), Ramiro Mendoza (middle)

Celebrating Andean Gems

New book immerses readers in spectacular hummingbirds, flamingos, and more feathered showstoppers by Matt Mendenhall bird photos by Owen Deutsch