At the Threshold of Study and Observation: Instrumentalising Architecture for the Containment of the Hysterical Woman

Laure Ségur

Laure Ségur

At the Threshold of Study and Observation: Instrumentalising Architecture for the Containment of the Hysterical Woman

In contemporary society, the word “hysteria” is symptomatic1, relating to a “crazy” or “frantic” state subsequent to stressful events. People experiencing signs of hysteria can seek support through associations like the Hearing Voice Network2, and yet, they still remain ignored by society This misunderstood “state” lost its significance, coincidentally with the progressive rise of the First World War. This essay intends to revisit a period of time in history when hysteria was an object of segregation and debate in the medical field. The investigation begins by diving back into hysteria’s original apparition during the end of the 19th century, therefore becoming a necessity to comprehend its widespread medical and social impact

At that time, hysteria was believed to infect strictly women, and the research carried out in a medical environment, served as justification for incarcerating women and pursuing intrusive experiments on their body. At the hospital of the Salpêtrière in Paris, France, Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot pioneered the study of hysteria, carrying out treatments that were supposed to heal the infected women

The architectural typology of the Salpêtrière embodied the scalpel - the instrument - that dissected the disease, searching limitlessly for the archetype of the mad woman. As bodies and spatial interactions were controlled, the voice - an expression of the mind - was then tamed The theatrical qualities burgeoning from Charcot’s Leçons du Mardi3, Bal des Folles4, and the documentation amassed from consultations and photography, entailed a mystification of hysterical women, resulting in attempts to contain their voices, perpetuating an everlasting madness The architecture thus engendered a duality between a studied specimen and spectacle for observation as the boundaries separating medical strategies from morbid fascination progressively blended, restraining women’s bodily and physical speech.

The ambiguous hospital typology

On the plan of the hospital (Fig 1), annotated by Charcot, a church, an amphitheatre, a casting workshop, and a photography cabinet can be discerned as part of the structure. In 1870, Jules Ferry, who was in favour of secularism, proclaimed that “women should belong to Science or otherwise they will belong to the church’’5, which linked the building to these words In the context of this speech, women did not have much choice and were constrained to these two establishments, Ferry implying that one is better than the other. The Church already believed hysterics were possessed by demons, whereas Science was just beginning to investigate the rising hysteria6 The Salpêtrière became the ‘church’ of medicine, a place for progress and study of ‘invisible forces’ that were mental

1 Defined by symptoms

2 Network supporting and providing resources for people who can hear voices

3 In English: Tuesday Lessons, carried out to demonstrate hysteria to a crowd of doctors

4 In English: The Bal of Madwomen, organised every year at the Salpêtrière, reunited the high Parisian society and the hysterics for a night

5 Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad : A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present (London: Virago, 2010), 142.

6 Ibid, 143

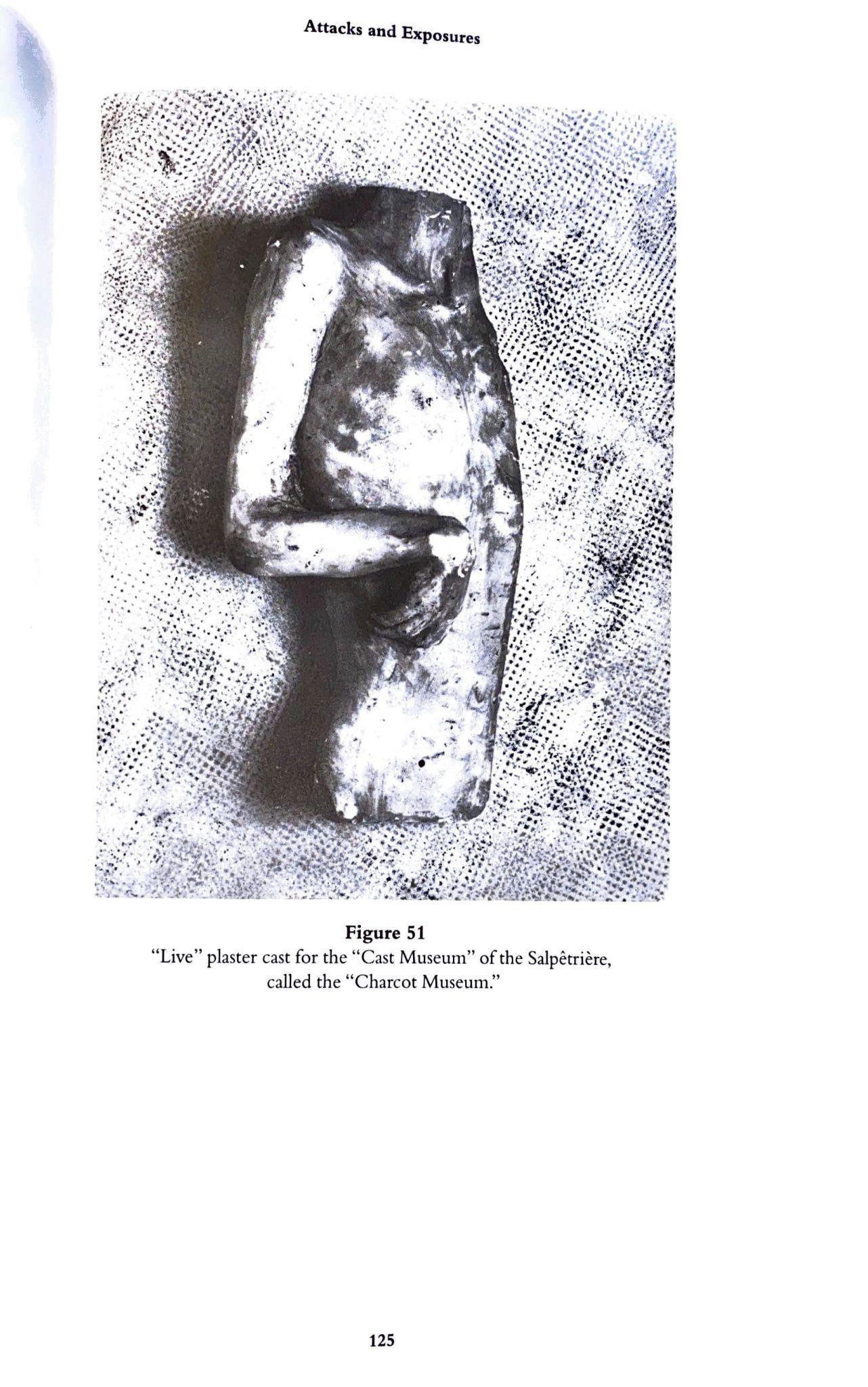

illnesses, associating the hospital typology to a tool of analysis The doctors even developed feelings of fascination for hysteria7, creating a tangent between the study and obsession. Therefore, the architectural typology of the hospital creates a duality between fixation and pure clinical research, which lead to a sort of containment Hysterical women could only “belong’’, connecting them to properties, objects of study, and not people The plan thus displays this idea of containment, by the presence of both institutions on grounds that were already at the times considered as radically opposed and fractured Women’s roles were contained, and hysterical women’s conditions were fixed in society A casting workshop and a photography atelier were also established in the Salpêtrière (Fig 2), linking the plan to art, the art of hysteria, the mental illness made visual, tangible, external to one’s head Doctor Jean-Martin Charcot did so too by instrumentalising the amphitheatre of the hospital Every Tuesday, he would carry out sessions called “Leçons du Mardi’’ during which he would show other doctors, and even artists, and writers the ease in which hysterics could be hypnotised8. Photographer Paul Regnard captured one of these classes, where Blanche Wittman, one of Charcot’s most famous patients, fell in the arms of Dr Joseph Babinski, French-Polish neurologist, while being hypnotised by Dr Charcot (Fig 3) The spatial segregation contradicts the gendered boundaries in this image: Blanche’s arched position, her bared body, the touch of a man who is not her husband, are moments which, in regards to society’s standards, were to remain intimate, and hidden, but were exposed in a room reaching its near full capacity9 Charcot described the men in the room as “captivated by the experiment’’10; this captivation indicates that there are no limits to these experiments, and reinforces the parallelism between a study and an subjectified observation. The hysterics were put on display, in a sexualised manner, which was considered outrageous and completely improper at the end of the 19th century had it been for a “normal” woman It could be argued that a certain joy or accomplishment arises when one finalises a discovery, but in this case, the “captivation” of the doctors is prompted by a body. It became a sensorial experience, highlighting an attraction for the subject The architecture was transformed into a place of pleasure, hosting spectacles, and ceased to function as a space for research and medical analysis Consequently, the space of the Leçons du Mardi, the space and the events of the amphitheatre triggered a sentiment of enjoyment, thus blurring the boundaries between example and production Charcot became the conductor of this public representation, turning the space of the amphitheatre, and thus hysteria, into an instrument for fixing the conditions of these women in the eyes of society, making them unable to evolve from it, containing their voices and their will.

It is also worth noting that hysterics were described as “theatrical’’ and doctors were warned against their tendency to “exaggerate”, “act”, and “lie”11, but by exhibiting the illness and the patients in this way, Charcot actually encouraged the performative aspect of hysteria, contradicting the advice given to his colleagues Charcot even wrote: “The theatrical quality of the fits should arouse suspicion and caution The helpless ecstasies of the fit could turn around into demonstration of power, acts of

7 Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad : A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present (London: Virago, 2010), 144

8 Ibid, 146

9 Louise J Kaplan, “Fits and Misfits: The Body of a Woman,” American Imago 50, no 4 (1993): 457

10 Ibid, 458.

11 Ibid, 459

rebellion, and a rampant sexuality ’’12 , suggesting that hysteria would serve as justification to contain signs of independence, even though they emerged from it. Hysteria became instrumental to deem these desires abnormal, as they came from a mental illness, and acquits the containment The word “demonstration” conveys a spatial aspect to the disease, suggesting that hysteria was perceived by the patient and the people surrounding her Space became the place where everyone could grasp hysteria: the patient felt it through her body and projected it inside a space where others were able to interact with it The ‘power ’ , ‘acts of rebellion’, and ‘rampant sexuality’ communicated by the body through space were then muted by the doctors, as they exercised a control over the environment where the fits occurred. The architecture served a double purpose: releasing the voice of the women's body, and serving as a dependent variable that the medical body seized in order to filter the communication, enacting the containment of that voice

In opposition to this photography, Dr Charcot organised a ball every year, inviting Le Tout Paris13 to mingle with the hysterics at the Salpêtrière. During this one night, all the guests were masked and danced together in an eerie and peaceful atmosphere, leaving their mental and social differences apart14 Firstly, merging the asylum and ballroom typologies is unexpected from the medical faculty, and questions its relationship with scientific impartiality and objectivity How can science be associated with art and such “frivolous” events? The ballroom thus embodied the merging between specimen and spectacle, serving the double purpose of giving relief to the ill for a night, granting them a space to observe too, but also to be seen by others Only in the ballroom was the specimen allowed to contemplate, at the same time as forming part of the spectacle Secondly, gathering hysterics, who were considered as outcasts with the high society could be qualified as dangerous To what end was Charcot organising this event? Was he satisfying a morbid curiosity expressed by the powerful gentlemen of the Parisian society or was it a treatment for his patients? The device of the mask worn by the guests15 protected the individuals’ identity from judgement. An act was performed, the guests were pretending to be different, not hysterical. Even though the Parisian gratin16 was conscious of the patients it was interacting with, the mask contained the women’s hysterical condition, it veiled it for one night, making it impossible to distinguish who was actually hysterical. The hospital environment was hence instrumentalised to organise this event and enabled the merge of the subject and the observant The social status these women were branded with was still fixed, but contained behind the mask, the space became an illusion of freedom, containing their voice in the sense of their identity

The Bal des Folles conveyed again a theatrical and artistic aspect to hysteria, morphing into a tool for display, art, and perhaps seduction as that was the primary function of balls Charcot contained the voices by giving them access to a typical social activity that his patients enjoyed but without ever leaving the grounds of the hospital, meaning they were never actually part of the society that came to observe them In this sense, there is no physical segregation in the ballroom of the Salpêtrière, but a containment in the social ranks The architecture therefore permitted the dual existence of these two elements in the same space at the same time, forcing the hysterics to remain

12 Louise J Kaplan, “Fits and Misfits: The Body of a Woman,” American Imago 50, no 4 (1993): 459

13 Expression qualifying the High Parisian Society of the 19th century

14 Choses à Savoir Podcast, “Podcast Choses à Savoir Qu’est-Ce Que Le ‘Bal Des Folles’ ?,” Choses à Savoir, April 20, 2020, https://www chosesasavoir com/quest-ce-que-le-bal-des-folles/

15 Ibid.

16 Expression qualifying the High Parisian Society of the 19th century

chained to their condition The space of the ballroom, the art, and the disease became a tool for that containment.

The body as an intermediary

Symptoms of hysteria are expressed through the mind, externalised through the body, and communicated through space, making the body the intermediary between the internal (psyche) and the external (space). The word hysteria comes from the Latin hystericus signifying “of the womb”17, because the disease was thought to be caused by a dysfunction of the uterus Charcot and Freud, however, acknowledged men could also suffer from it, and were silenced by other practitioners, containing the “fact” that this disease was not only female18. Hysteria was, in this sense, characterised by a gender rather than an organ, and became a sort of social tool to contain the role of women in society Deviant women who unconsciously rejected the norms of the nineteenth century were to be controlled and contained, and labelled hysterical; only after abiding by the social expectations could they be released. On one hand, hysteria and space developed into devices for controlling women’s roles in society: by associating them with a “failing” gender and not a “failing” organ, the body became the social norm and intervened as a specific parameter to determine and control their placethe space they were allowed to occupy - in society. On the other hand, the body was objectified and hence could not claim a right in society, which was examplified in the case of Blanche Wittman and the treatments administered to the other patients

On Régnard’s photograph (Fig. 3), Blanche was unconscious in the arm of Babinski, she was not aware of her surroundings which blurred the frontiers defining an inanimate body, or an inanimate object of experimentation When she was unconscious, and what the camera fails to capture here, Jean-Martin Charcot would, by passing his hands in different areas of her body, make her paralysed limbs move or make her reproduce the traumatic scenes which had caused her to be ill - both considered as prominent symptoms of hysteria19 Beyond the voyeurism of the scene, it is as if Blanche lost control of her own body and Charcot was the director of it He was able to make some of her limbs move when even she could not, Blanche was not master of herself anymore, and in some way lost ownership of her own body Her mind was unable to communicate spatially as her body, the threshold, was not responding to her orders Charcot blocked her interactions with space, and therefore the expression of her voice by taking control over her body Charcot interfered with Blanche’s mind, locking it in an unconscious state, and thus instrumentalising architecture to harness her voice

The poem Une Charogne by Baudelaire20 sublimates a corpse, giving this impression of a beautiful cadaver, which is what Blanche embodies for an instant. Similarly, as he glamorises a decomposing body, turning it into an entity that sparks desire; Blanche changed from existing solely as a case study to symbolising an object of desire Her body is also partly exposed, in the arms of a man who by holding her, takes charge of her as she cannot stand on her own, suggesting that the control shifted Blanche was not a person anymore, she became an object for experimenting, a

17 Definition from the Oxford Dictionary

18 Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad : A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present (London: Virago, 2010), 146

19 Ibid.

20 See appendix

Fig 3 - Blanche Wittman fainting in the arms of Joseph Babinski, in-between specimen and spectacle

Fig 3 - Blanche Wittman fainting in the arms of Joseph Babinski, in-between specimen and spectacle

specimen, who could be touched in whatever way was the easiest to achieve results, disregarding the connotation. The ailment of hysteria and the process of hypnosis became instrumental in controlling a woman’s body, and by extension herself This induced loss of consciousness shifted the authority over one’s body and controlled the ill women, containing their symptoms, their own vocal and bodily expressions forming part of their voices The physical and spatial interactions with the body were justified by the type of space they were taking place in. The medical environment legitimised the doctor ’s behaviour, giving him unlimited access to women’s bodies Consequently, the hospital, the architecture, materialised a mechanism that sustained these methods of exploration, blurring the notions defining a person and a specimen, instilled this containment. By extension, Ferry, viewed as a potent politician, indirectly authorised these methods as he was convinced that Science was better than Church In his opinion, as long as medicine was encouraged, secularism won over religion despite the conditions in which women were chained to Hysterical women thus “belonged” to the hospital and the people in charge, they could only exist in this architecture, which served as an instrument for their study and observation leading to the restriction of their voice

Blanche and other patients underwent a variety of treatments directed towards their female attributes To cure their hysteria, they inhaled valerian, or amyl nitrate, or ether, or ingested highly addictive chloral, which actually triggered more fits than they seemed to produce at first21 They also had hot metals put inside of them, went through ovarian compressors, took cold baths, had electricity passed through them, and doctors pressed on “hysterogenic” zones to produce symptoms of their hysteria, which included intimate body parts22 The approach to treatment could be qualified as ‘violent’ and ‘harmful’ as it enhanced the malady rather than curing it, questioning its naming The treatments were intrusive, painful, and restrictive as the primary aim was to purge the female attributes. They were acts of containment, restriction and punishment, which contradicted the notion of liberating and curing the patients of their mental illness Could these processes still be qualified as a treatment or do they correspond to spectacles? These methods of treatment solidified the illness by containing it even more, and in so doing, connected the disease to an instrument for control. Containing the symptoms, the fits, in this violent approach, constituted a way to restrict the hysterics’ expression The treatments became mechanisms that supervised the voice, commanding its bodily and spatial articulation. The apparatus used to deliver the treatments were essential in constituting the medical space, and making the hospital recognisable. Architecture was, thence, connected to their employment and linked to the duality between treating and harming the specimen that were the women The specimen became the centre of treatments without clear limits; a spectacle within the medical space controlling the body and the female figure.

Theorisation of the unconscious

Jean-Martin Charcot’s experimentations on hysterics led to first recordings of the unconscious23 This theorisation developed in different ways that contained two women’s voices: Hersilie Rouy and Augustine Gleizes. Hersilie Rouy was the illegitimate daughter of the astronomer Henri Rouy, with whom she lived in Paris24. She was part of the Parisian gratin, famous for her

21 Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad : A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present (London: Virago, 2010), 155

22 Ibid, 156

23 Ibid, 160.

24 Ibid, 101

accomplished skills as a pianist25 In 1854, a few years after her father ’s death, her half brother conspired against her and had her thrown in the Salpêtrière26. After being examined for two minutes, she wrote, she was “sentenced” to stay to be treated as one of the patients, and she was refused her birth name after entering the facility27 The verb “sentenced” indirectly describes the Salpêtrière as a prison, where she lost a part of her identity, a part of her voice that was her name and kept her safe knowing that she was an illegitimate child. In her memoirs Mémoires d’une Aliénée, Hersilie kept writings conveying the abuse she suffered at the Salpêtrière, as police officers came to test her to assess the possibility of her being released, she recounts: “They came to test my thinking, my beliefs, to see if there were grounds for keeping me in perpetuity … How can you destroy the future of a woman and allow her liberty to be assaulted simply because she carries her head high and has the audacity to want to live from her own talent and her own writing? I have been buried alive ’’28 Hersilie proved that she was fully aware of her environment and the events taking place, she was not insane but the victim of her brother ’s schemes. In addition, the medical staff found letters she wrote incriminating police officers in her belongings as she entered the facility, which they used as evidence for her hysteria29 This constitutes an act of containment, using her voice as a tool to identify her as a hysterical person. She theorised her abuse, and through her writing, gave an understanding of what the doctors would qualify as hysteria. She exemplified the way in which these doctors attempted to physically contain her in order to imprison her mind The Salpêtrière aimed to extinguish her “rebellious” voice by containing her in a smaller specialised space The role of architecture was, consequently, to mute her, which created a duality as her writings liberated her voice to theorise her abuse; she was contained only temporarily.

The Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, images and texts recording patients serving as an important guide to identify symptoms and behaviours of hysteria30, captured a tangent between study and fetishisation of hysteria that immobilised women’s voices Doctor Bourneville’s notes, photographic research, and hypnotic sessions, are proof of his attempt at uncovering the archetype of the hysterical woman31; meaning that he was de facto restricting his patients. They were considered as experiments until his goal was achieved, confirming that the clinical objectivity of medicine dissipated

Augustine Gleizes, captured multiple times by Régnard, exhibited her contracture (Fig 4) during which all her members went rigid; her fore-arm twisted, her fingers suddenly curved in the palm of her hand, while her right leg pained her as it contracted32 The title acts as the only indication of hysterical signs as the photography itself dissimulates the symptoms evoked33. Similarly to Blanche, Augustine’s skin is laid bare to the camera, with only a drape covering it Her extended leg occupies the lower quarter of the frame, taunting the eye instantly The symbols distort the clinical documentation of the specimen in the photograph, giving space otherwise to a spectacle. This

25 Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad : A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present (London: Virago, 2010), 101.

26 Ibid, 102

27 Ibid

28 Ibid, 103.

29 Ibid, 104

30 Ibid, 148

31 Ibid, 149

32 Georges Didi-Huberman and J M Charcot, Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge, Mass.: Mit Press, 2003), 246.

33 Ibid

photograph represents hysteria in a sexualised, and “sinful” perspective, fetishising the body of a sick woman34. A fictionalised, imaginative light is cast onto the specimen who becomes an extravaganza. The lack of background or context make it seem like the picture is staged, resembling a performance manipulating the audience Augustine therefore acquires the status of an icon, an object of desire and not a simple clinical case study; she and the other women posing for Régnard’s lens are mystified, hysteria - ironically - is hypnotising. In that regard, the perpetuated fascination created around hysteria “keep[s] madwomen mad”35, chaining them to their condition The composition of the photography, its lack of a context, of an existing recognisable architecture, emphasised the metamorphosis of the specimen to a spectacle enticing an audience.

In conclusion, the Salpêtrière's architecture, spatial elements, and documentation became instruments to justify a duality between the study of a specimen and the spectacle that derived from it The hospital, symbolising an unholy ‘church’ for science, harnessed women’s voices by forcing them to ‘belong’. Hysteria, originally a mental health disease to be studied, morphed into a fascination, as the medical context of the architecture regulated and justified this transformation. As a specific case cannot represent the generality, architecture was instrumentalised and voices were being manipulated to solve an impossible equation, which in itself established an act of containment The hysterics were epitomised both as subjects of study and phenomenons of lust which they could not evolve from. By fetishising bodies, attitudes, and expressions via the architecture, a duality between demonstrating and performing emerged, ensuring an everlasting madness, and pursuing the untrue archetype of the hysterical woman The voices and experiences of the patients, as well as the Hippocratic oath gradually cross the threshold separating science from fiction, constituting a form of containment.

35 Ibid, 247

34 Georges Didi-Huberman and J M Charcot, Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge, Mass.: Mit Press, 2003), 246.Une Charogne

Rappelez-vous l'objet que nous vîmes, mon âme,

Ce beau matin d'été si doux:

Au détour d'un sentier une charogne infâme

Sur un lit semé de cailloux,

Les jambes en l'air, comme une femme lubrique, Brûlante et suant les poisons,

Ouvrait d'une façon nonchalante et cynique

Son ventre plein d'exhalaisons

Le soleil rayonnait sur cette pourriture, Comme afin de la cuire à point,

Et de rendre au centuple à la grande Nature

Tout ce qu'ensemble elle avait joint;

Et le ciel regardait la carcasse superbe

Comme une fleur s'épanouir

La puanteur était si forte, que sur l'herbe

Vous crûtes vous évanouir.

Les mouches bourdonnaient sur ce ventre putride,

D'où sortaient de noirs bataillons

De larves, qui coulaient comme un épais liquide

Le long de ces vivants haillons.

Tout cela descendait, montait comme une vague

Ou s'élançait en pétillant;

On eût dit que le corps, enflé d'un souffle vague, Vivait en se multipliant.

Et ce monde rendait une étrange musique, Comme l'eau courante et le vent,

Ou le grain qu'un vanneur d'un mouvement rythmique

Agite et tourne dans son van.

Les formes s'effaçaient et n'étaient plus qu'un rêve, Une ébauche lente à venir

Sur la toile oubliée, et que l'artiste achève Seulement par le souvenir.

Derrière les rochers une chienne inquiète

Nous regardait d'un oeil fâché, Epiant le moment de reprendre au squelette

Le morceau qu'elle avait lâché.

Et pourtant vous serez semblable à cette ordure, À cette horrible infection,

Etoile de mes yeux, soleil de ma nature,

Vous, mon ange et ma passion!

Oui! telle vous serez, ô la reine des grâces, Après les derniers sacrements,

Quand vous irez, sous l'herbe et les floraisons grasses, Moisir parmi les ossements

Alors, ô ma beauté! dites à la vermine

Qui vous mangera de baisers, Que j'ai gardé la forme et l'essence divine

De mes amours décomposés!

Charles Baudelaire

A Carcass

Recall to mind the sight we saw, my soul, That soft, sweet summer day:

Upon a bed of flints a carrion foul,

Just as we turn'd the way, Its legs erected, wanton-like, in air, Burning and sweating pest, In unconcern'd and cynic sort laid bare

To view its noisome breast.

The sun lit up the rottenness with gold, To bake it well inclined, And give great Nature back a hundredfold

All she together join'd.

The sky regarded as the carcass proud

Oped flower-like to the day;

So strong the odour, on the grass you vow'd

You thought to faint away.

The flies the putrid belly buzz'd about, Whence black battalions throng

Of maggots, like thick liquid flowing out

The living rags along.

And as a wave they mounted and went down, Or darted sparkling wide;

As if the body, by a wild breath blown, Lived as it multiplied

From all this life a music strange there ran, Like wind and running burns;

Or like the wheat a winnower in his fan

With rhythmic movement turns

The forms wore off, and as a dream grew faint, An outline dimly shown, And which the artist finishes to paint

From memory alone

Behind the rocks watch'd us with angry eye

A bitch disturb'd in theft, Waiting to take, till we had pass'd her by, The morsel she had left.

Yet you will be like that corruption too, Like that infection prove

Star of my eyes, sun of my nature, you, My angel and my love!

Queen of the graces, you will even be so,

When, the last ritual said,

Beneath the grass and the fat flowers you go, To mould among the dead.

Then, O my beauty, tell the insatiate worm

Who wastes you with his kiss,

I have kept the godlike essence and the form Of perishable bliss!

Richard Herne Shepherd, Translations from Charles Baudelaire (London: John Camden Hotten, 1869)

Bibliography

Adams, Parveen “Symptoms and Hysteria ” Oxford Literary Review 8, no ½, 1986, 178–83

Akaviaa, Naamah “Hysteria, Identification, and the Family: A Rereading of Freud’s Dora Case.” American Imago 62, no. 2, 2005, 193–216.

Appignanesi, Lisa Mad, Bad and Sad : A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present. London: Virago, 2010, 97-166.

“Bethlem Royal Hospital Its Approaching Removal ” The British Medical Journal 1, no 3465, 1927, 1017–18

“Charcot and the Salpêtrière ” The British Medical Journal 2, no 3387, 1925, 1016–16

Choses à Savoir. “Podcast Choses à Savoir Qu’est-Ce Que Le ‘Bal Des Folles’ ?” Choses à Savoir, April 20, 2020. https://www.chosesasavoir.com/quest-ce-que-le-bal-des-folles/.

fleursdumal org “Une Charogne (a Carcass) by Charles Baudelaire,” n d https://fleursdumal.org/poem/126.

Didi-Huberman, Georges, Charcot, Jean-Martin Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière Cambridge, Mass : Mit Press, 2003, 157-295

Kaplan, Louise J “Fits and Misfits: The Body of a Woman ” American Imago 50, no 4, 1993, 457–80

Micale, Mark S. “The Salpetriere in the Age of Charcot: An Institutional Perspective on Medical History in the Late Nineteenth Century ” Journal of Contemporary History 20, no 4, 1985, 703–31

Morrison-Valfre, Michelle Foundations of Mental Health Care St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, 2017, 5-9

Rykwert, Joseph. “Ritual and Hysteria.” Ekistics 44, no. 265, 1977, 296–300.

Sedgwick, David “Hysteria’s Notorious History Mark Micale Approaching Hysteria: Disease and Its Interpretations. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1995. Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen .Remembering Anna O.: A Century of Mystification. New York and London, Routledge, 1996 ” The San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal 16, no 3, September 1997, 39–46

Image References

Figure 0, cover page : Charcot, Jean Martin. Nouvelle Iconographie de La Salpêtrière, Clinique Des Maladies Du Système Nerveux Paris, France: Lecrosnier et Babè, 1888, 14

Figure 1, page 13: Didi-Huberman, Georges, Charcot, Jean-Martin. Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière Cambridge, Mass : Mit Press, 2003, 14

Figure 2, page 14: Ibid, 125.

Figure 3, page 15: Brouillet, Pierre-André A Clinical Lesson with Doctor Charcot at the Salpetriere 1887 Photography

Figure 4, page 16: Didi-Huberman, Georges, Charcot, Jean-Martin. Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière Cambridge, Mass : Mit Press, 2003, 248

Figure 5, page 17 : Ibid, 249.