20/03/2025

Kristy Farhat

From Discipline to Duality

Tracing the Life and Afterlife of the Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais de Beyrouth

Introduction

There is a strange familiarity in walking through a place where thousands have walked before you, but few have questioned why it looks and functions the way it does. The Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais de Beyrouth (GLFL) is one of those places. As someone who studied there, and now as an architecture student returning with new eyes, I see the school differently. Not just as a backdrop to childhood memories, but as an architectural artefact a carefully designed space of care, discipline, and ideology.

When I was younger, the school seemed neutral just a place I had to be. I never questioned the logic behind its layout, the uniformity of the hallways, or why we moved the way we did within its walls. But now, I find myself revisiting the site with a critical gaze, asking not only how it was built, but why. Who was it built for? What values are embedded in its architecture? These questions have shifted my understanding of the school from a static memory into a living archive of colonial, modernist, and postwar ambitions.

GLFL, like many educational institutions in Lebanon, has been shaped by waves of historical upheaval. It has been influenced by French colonial policies, endured the trauma of civil war, and adapted to contemporary demands of bilingual and global education. Yet its architecture has consistently carried the marks of authority and control, even in moments of transition. This essay tries to unpack these layers to explore how architecture participates in shaping identity, enforcing discipline, and enabling care.

This is not just an architectural analysis. It’s a return to a place that shaped me, but one that I now see as a complex, contradictory artefact. It begins with the work of Michel Écochard, the French architect behind its mid-century transformation. It moves through the layers of its colonial founding, its survival during Lebanon’s civil war, and into its current, hybrid state. Along the way, I ask: what parts of the original school are still visible? Which memories were erased, and which ones were kept alive? Most importantly, what does this building this institution still teach us about power, identity, and care?

The Architect at the Edge

Concept Structure. (n.d.). Table Rocket. Concept Structure. Retrieved March 20, 2025, from http://www.conceptstructure.com/portfolio/table -rocket/

Michel Écochard’s design for GLFL, completed in the 1960s, carries the marks of his modernist ideals and his colonial experience. Known for his work in Casablanca and Damascus, Écochard approached architecture as a tool of rational planning and social control (Châtelet, 2017). He believed that good design could shape behavior, order cities, and, implicitly, populations. When he was commissioned to design the new campus of GLFL in Achrafieh, Beirut, he had already absorbed the language of modernism and the strategic goals of colonial urbanism.

The school was positioned on a hillside, organized with a clear grid system, open courtyards, and modular classroom buildings. His layout followed principles similar to those used in other places France had colonized, like Morocco and Tunisia spaces where movement was clearly directed,

classrooms were arranged along long corridors, and areas were zoned with specific uses in mind. Everything from how students entered the site to how they moved between buildings was part of an architectural system designed to make circulation feel smooth, but also to manage behavior and flow (Châtelet, 2008). From an architectural standpoint, these features responded to the educational aspirations of the time: to raise the ideal, modern student through controlled but caring spaces.

As a student walking through those spaces, decades later, I remember how the school always felt orderly. Even when we weren't being directly watched, we behaved. There was something about the straight lines of the hallways, the regular rhythm of the classroom blocks, and the separation of different functions that subtly enforced structure. It wasn’t until I read Foucault that I understood why. As he describes in Discipline and Punish (1975), institutional spaces schools, hospitals, prisons are structured to observe, normalize, and train bodies. The grid, the bench, the corridor: these are not passive architectural elements. They are instruments of discipline.

GLFL, in that sense, wasn’t just a school. It was a well-oiled machine for shaping behavior. And while it may have looked clean and open with its modernist courtyards and long sightlines, that openness was also a form of control. Écochard’s vision, though rooted in care and hygiene, made GLFL a model of pedagogical order. What begins at the architectural edge the walls, the gates, the layout extends inward into the behavioral core.

Alchetron. (n.d.). Michel Écochard Alchetron. Retrieved March 20, 2025, from https://alchetron.com/Michel -Ecochard

Colonial Foundations (1920–1943)

Although the Grand Lycée was initially founded in 1909, its institutional identity was solidified during the French Mandate period (1920–1943). At that time, Lebanon was under French control, and education became one of the main tools of cultural assimilation. The Mission Laïque Française (MLF), a secular French educational organization, was responsible for exporting French language, values, and civic instruction throughout colonial territories, including Lebanon (Uduku, 2018).

GLFL was never just a place to learn math and grammar. It was a place where students; Lebanese students like me were taught to become culturally French. Like similar schools in Algeria, Senegal, and Indochina, GLFL served as a colonial institution intended to cultivate a Francophone elite. The goal was not only to educate but to "civilize" a term used to mask the political function of embedding loyalty to the French Republic. The curriculum was French, the holidays were French, and the ideals taught were those of the métropole, not the local reality (Pinto, 2019).

Architecturally, the school during this early period was modest, using existing structures in Sodeco. But even then, the spatial arrangement of classrooms, desks, and blackboards adhered to imported French standards. In Burke and Grosvenor’s (2008) terms, the school functioned as a "beacon of civilization," replicating the same norms and values used in metropolitan France to define order, hierarchy, and progress.

From the beginning, GLFL embodied the contradictions of care and control. Children were grouped by age, subjected to strict timetables, and instructed in a language that was not their own. These practices mirrored the disciplinary model described by Foucault (1975), where institutions create docile bodies not by force, but by repetition, surveillance, and normalization.

Looking back now, I realize how much this duality shaped my experience. On one hand, I received a world-class education. On the other, I was immersed in a system that privileged French identity over my own. The architecture, curriculum, and rituals reinforced a system of belonging that aligned with France’s colonial mission, not Lebanon’s pluralistic society.

The Civil War and the Green Line (1975–1990)

Alchetron. (n.d.). Michel Écochard. Alchetron.

Retrieved March 20, 2025, from https://alchetron.com/Michel -Ecochard

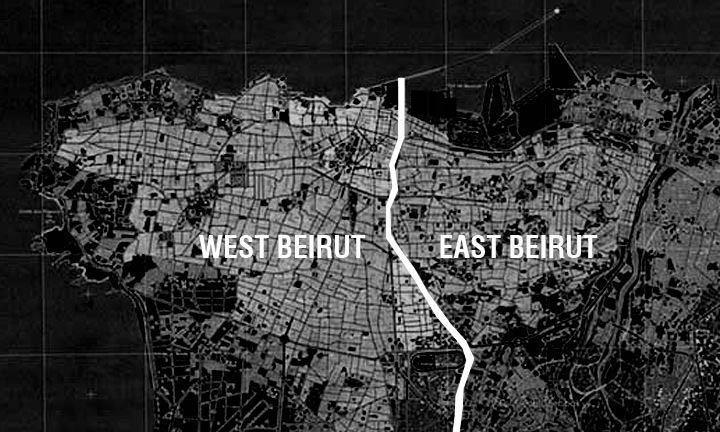

When the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975, GLFL found itself caught between the fault lines of a divided city. Located in Achrafieh, close to the Green Line that separated Christian East Beirut from Muslim West Beirut, the school was dangerously positioned. While I wasn’t born yet, I’ve heard stories from older alumni stories of sudden closures, interrupted exams, and even students diving under desks during nearby shelling. In these years, GLFL's usual routines crumbled.

The war didn’t just damage the buildings; it disrupted the entire spatial and psychological fabric of the school. Windows shattered, walls bore the scars of stray bullets, and rooms once filled with structured timetables now held silence and uncertainty. Entire portions of the school became inaccessible. Families who could afford to leave Beirut or Lebanon altogether pulled their children out. Teachers either left or adapted as best they could, sometimes teaching in basements or private homes when security allowed.

Some students reportedly crossed checkpoints just to attend class a decision not just rooted in academic commitment, but in identity. For many, GLFL represented a sense of normalcy, a way to hang on to cultural continuity amid chaos. And yet, the school could no longer fully perform its role as a stable institution of care. It became something closer to a shelter or sometimes, a relic.

The school’s experience mirrors what architectural theorists like Eyal Weizman (2007) or Stephen Graham (2010) describe: in times of war, buildings become both targets and shields. Schools, especially, are loaded with symbolic value. At GLFL, its French identity, its location, and its visibility made it both a place to preserve and a place at risk.

Reconstruction and Reprogramming (1996–2005)

Adnym. (n.d.). West Beirut, East Beirut Map – The Green Line. Retrieved March 20, 2025, from https://www.adnym.com/the -green-line/west-beirut-eastbeirut-map/

By the time I enrolled at GLFL, the war was over, but the echoes were still there. Between 1996 and 2003, the school underwent massive reconstruction. What stood out to me then but only made sense later was how some buildings felt "newer," while others still had the same heavy doors, tile patterns, or 1960s window proportions. Écochard’s architecture hadn’t been erased. It had been layered over, upgraded, and in some cases, quietly replaced.

The most visible addition was the Stade du Chayla, built in 2005 and later renovated in 2018. To us students, it was just the sports center. But now I see it as part of a broader strategy to modernize the school's identity without completely rewriting its past. New buildings were added with smoother cladding and brighter interiors, but they still respected Écochard’s master plan the grid was maintained, courtyards re-used, even if their functions had shifted.

The reconstruction phase also marked a shift in tone. From the outside, GLFL looked like a place of continuity. But inside, the spatial memory was more fragmented. Some classrooms still carried

traces of war-doors that didn't quite fit their frames, tiles that had been patched up. Others felt completely international, fitted with smartboards, new furniture, and wall-to-wall insulation.

There were no commemorative plaques, no formal acknowledgments of the war damage. This absence stuck with me. Was it a form of moving on? Or was it, as some theorists suggest, a kind of strategic forgetting an effort to rewrite the narrative through architecture, to emphasize progress rather than trauma?

That silence, architectural and institutional, said a lot. It’s where I began to question how schools shape not only students, but also histories.

GLFL Today: Hybrid Continuities and Unfinished Conversations

Snap Engineering. (n.d.).

Schools. Retrieved March 20, 2025, from http://snapeng.com/singleservice/schools

Walking through the campus today, there are parts that still feel like Écochard’s original vision the clean grid, the open-air walkways, the shaded courtyards but the function of these spaces has shifted. The same corridor where students once marched between subjects now feels like a liminal zone still orderly, but less rigid. There are new layers now: smartboards where chalkboards used to be, LED-lit corridors with modern surveillance cameras, and furniture designed for flexibility rather than discipline.

Some of Écochard’s buildings remain intact, while others have been refurbished beyond recognition. The additions have tried to speak a contemporary architectural language, but not always fluently. For instance, the new facades sometimes feel like a smooth mask over the scars

of history. You can still find a few classrooms with original flooring or vintage ventilation grilles traces that quietly whisper the past. But overall, the architecture today doesn’t scream about its history; it mutters it.

The school has expanded both spatially and academically. It now offers more bilingual and even trilingual education, accommodating international students alongside Lebanese elites. But the barriers, though less visible, are still there. Access is gated, both literally and socially. Not everyone can enter this world of polished hallways and hybrid curricula. In some ways, GLFL remains a bubble separate from the city that surrounds it.

And yet, this bubble is evolving. I’ve seen firsthand how teachers now encourage more critical thinking, how students are more vocal, and how classrooms are less about memorization and more about discussion. Maybe the walls haven’t moved much, but what happens inside them has changed. Still, the question lingers: can a space built for order truly host freedom?

It’s also worth noting the subtle shifts in student culture what once felt like a top-down flow of knowledge now sometimes reverses. Students organize events, start debates, question teachers. These micro-resistances are architectural too. They reshape how space is used: hallways become forums, the stairs near the library a social stage. The building hasn’t changed, but the meanings attached to it have.

architectural site plan

GLFL and the City

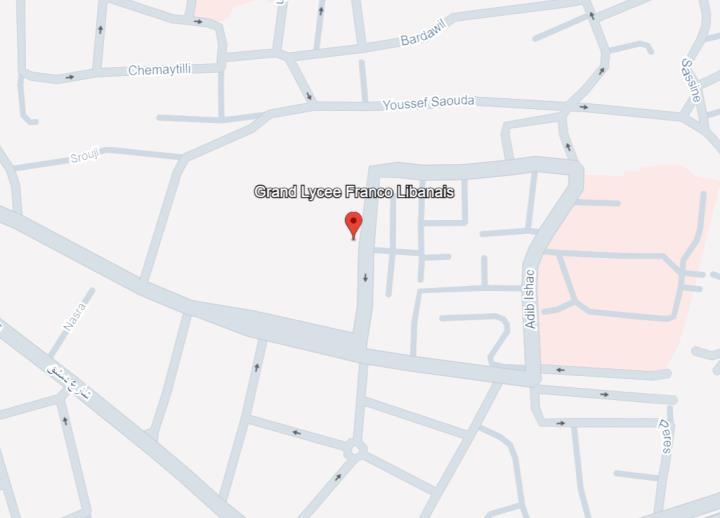

GLFL’s presence in Achrafieh is not incidental. The school is positioned between Charles Helou Bridge and the dense urban fabric of East Beirut a district marked by both historical prestige and postwar fragmentation. Unlike some other elite schools tucked away in the hills or suburbs, GLFL is embedded in the city. Yet, ironically, it also seems to float above it.

On one hand, its centrality gives it symbolic weight: it’s a visible, walkable monument to secular, Francophone education. On the other hand, its design and access protocols keep it distinctly separate. When I was a student, the contrast between the chaos of the surrounding traffic and the calm once inside the gate was sharp. It felt like entering a parallel city a quieter, cleaner one, with its own codes and rhythms.

This separation is architectural but also social. The school has always catered to a specific demographic Francophone Lebanese, dual nationals, children of diplomats or professionals. Its high walls and tight entrance protocols mirror not just security concerns, but a kind of cultural insulation. It participates in the city without fully being of it.

Yet, the city leaks in. The noise of Achrafieh, the smells of manouche stands nearby, the constant tension between tradition and modernity all of it presses against the campus edges. And that pressure matters. As Beirut transforms politically, economically, even seismically GLFL cannot remain untouched. Whether through increased diversity in its student body or subtle changes to its spatial openness, the relationship between school and city is shifting.

Google. (n.d.). [Satellite image of Grand Lycée FrancoLibanais de Beyrouth, Achrafieh, Beirut]. Google Earth. Retrieved March 20, 2025, from https://earth.google.com

Theoretical Reflections: Architecture, Discipline, and the Politics of Memory

Foucault’s theory of the Panopticon is especially useful here. At GLFL, even when there’s no one watching, the architecture suggests that someone could be. Surveillance is embedded not just in cameras, but in the way space is structured how doors open, how stairs lead to staff-only zones, how you can be seen from across a courtyard. This kind of visibility creates self-discipline (Foucault, 1975).

But care and control are not opposites they coexist. According to Gutman and De Coninck-Smith (2008), schools are built to care for children, but they do so by regulating them. The architecture the desks, the wall displays, the placement of windows is all part of a material culture that creates childhood as a specific, governed experience. GLFL, with its blend of old and new, continues to create that experience.

Meanwhile, the idea of “selective remembrance” plays out in the school’s treatment of its own past. There are no visual acknowledgements of the civil war or the school’s colonial history.

Unlike Canada’s residential schools, which have become sites of national reckoning (Valadares, 2016), or Algeria’s French lycées, many of which were closed post-independence, GLFL chooses a quiet path. It survives by adapting not denying its history, but not making it central either. This is what Ann Laura Stoler (2008) might describe as the “politics of deferral” acknowledging just enough to move on, without ever fully confronting the implications.

What’s especially interesting is how GLFL compares to other post-conflict schools in Beirut. Some, like Lycée Abdel Kader in Ras Beirut, closed or relocated. Others reinvented themselves entirely. Yet GLFL stayed adapted, yes, but stayed. This stability gives it power, but also responsibility. Its choice to avoid public memory work places it in a quiet category of institutions that carry history silently. Perhaps this is survival strategy. Or perhaps, as Graham (2010) might argue, it’s a form of spatial amnesia a way of keeping things running by keeping them unspoken.

Conclusion: What Survives in a School?

Atelier Jad & Sami Tabet. (n.d.). Grand Lycée FrancoLibanais – Beyrouth Retrieved March 20, 2025, from http://atelierjstabet.com/equ ipement/grand-lycee-francolibanais-beyrouth/

GLFL is still here. It still educates, disciplines, and protects. Its buildings are still mostly Écochard’s, though layered and re-skinned. Its ideals are still partly French, though increasingly hybrid. And its students past and present still carry the weight of its spatial and cultural structure.

As an architecture student revisiting the school, I realize that its strength lies in its ability to carry contradictions. It is both colonial and postcolonial, both rigid and evolving, both elite and plural. Its architecture teaches just as much as its curriculum.

What survives in a school is more than walls. It’s memory. It’s silence. It’s adaptation. GLFL may not display its past on plaques, but it’s there in the awkward junctions between old tiles and new wiring, in the fading classroom corners, and in the minds of students like me, who once sat in orderly rows and now ask: what was this space really trying to teach us?

Learning to See Differently

The image represents the enduring legacy of the school's educational mission and its impact on successive generations.

Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais. (n.d.). Official website Retrieved March 20, 2025, from https://glfl.edu.lb/

Writing this essay made me walk through GLFL again not just physically, but emotionally and intellectually. I began by asking what was left of the school’s past, but I’ve realized it’s not about the bricks and corridors alone. It’s about how those spaces made us feel, how they guided us, limited us, sometimes protected us. It’s about how architecture can teach even when no one is speaking.

As someone who grew up in these spaces and now studies how they are made, I carry both privilege and responsibility. Schools like GLFL shape identity not just through books and tests, but through thresholds, windows, and seating plans. They are institutions of care, yes but care shaped by politics, by design, by legacy.

Maybe the most important thing GLFL taught me wasn’t written on any blackboard. Maybe it was the ability to notice what isn’t said. To read the walls, not just the books.

Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais. (n.d.). Présentation Retrieved March 20, 2025, from https://www.glfl.edu.lb/prese ntation/

References

Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais de Beyrouth. (n.d.). Présentation de l’établissement. Mission Laïque Française. https://www.mlfmonde.org/etablissement/grand-lycee-franco-libanais-de-beyrouth/

Burke, C., & Grosvenor, I. (2008). School: Beacons of civilization. Reaktion Books.

Châtelet, A.-M. (2008). A breath of fresh air: Open-air schools in Europe. In M. Gutman & N. De Coninck-Smith (Eds.), Designing modern childhoods: History, space, and the material culture of children (pp. 27–42). Rutgers University Press.

Châtelet, A.-M. (2017). Architectures scolaires: 1900–1939. Éditions du Patrimoine.

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Vintage Books.

Graham, S. (2010). Cities under siege: The new military urbanism. Verso.

Gutman, M., & De Coninck-Smith, N. (Eds.). (2008). Designing modern childhoods: History, space, and the material culture of children. Rutgers University Press.

Pinto, M. (2019). Colonial education and the Mission Laïque Française. Journal of Middle East History, 54(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743819000107

Stoler, A. L. (2008). Imperial debris: Reflections on ruins and ruination. Cultural Anthropology, 23(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2008.23.2.191

Uduku, O. (2018). Learning spaces in Africa: Critical histories to 21st-century challenges and change. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315266276

Valadares, D. (2016). Indian residential schools: Carceral classrooms in Canada. The Funambulist, (4). https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/the-police/indian-residential-schools-carceralclassrooms-in-canada

Weizman, E. (2007). Hollow land: Israel’s architecture of occupation. Verso. https://www.versobooks.com/products/2659-hollow-land