Finding Community down South Bermondsey

Architectural Association

HTS 3: The Local in Social Theory: Global Perspectives & Possibilities

Tutor: Nick Simcik Arese

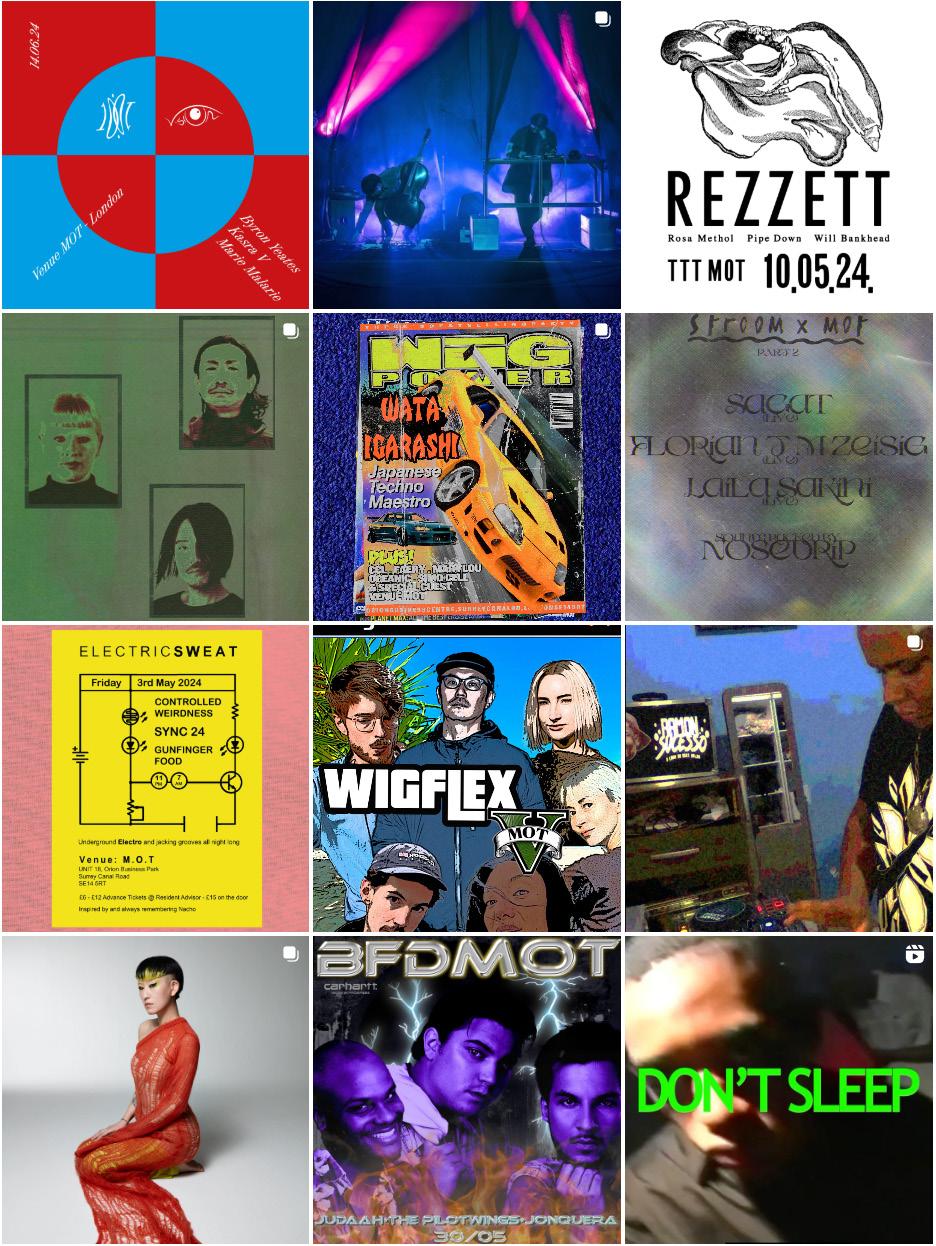

Extract from Venue MOT’s Instragram page

‘ STRAIGHT DOWN SURREY CANAL ROAD. YOU WILL FIND GROWTH, SOLUTIONS & CHEAP CANS. SEE YOU DOWN THE MOT ’. Eclectic visuals, cryptic descriptions, and an SE postcode might be the first gateway for much of the crowds gathering in the venues of South Bermondsey. Likewise, this essay will go “down” Bermo, to unravel the dynamics of community formation and individual identity within its post-industrial landscape. Georg Simmel’s study of the impact of the rapid transformations brought by modernity in The Metropolis and Mental Life will serve as a reference to understand a similarly fragmented and economically-driven contemporary city, an alienating and anonymous landscape ideal for the emergence of new forms of association. First, through raving, an anonymous place for the strongest eccentricities to thrive while building an identity through sound and space; second, the housing co-op Sanford embodying a voluntary, tight-knit community balancing collective responsibility with personal autonomy; and third, through two council estates which, despite their state-driven apparatus, are harnessing the changes around them to build resilience within. The essay is written in parallel to axonometric drawings highlighting the value of the belonging and collective care that is created by these spaces by placing them in the context of a broken apart urban fabric. Situating Simmel’s theory within these local responses, the text and illustrations seek to shine light upon often informal and overlooked happenings, especially at risk in upcoming regenerations. Ultimately, this essay offers an alternative reading to the ‘nothingness’ of South Bermondsey, where its neglected streets boast a rich ecology of community-driven cultures, where identity, autonomy, and social responsibility intersect in creative and subversive ways.

1 @venuemot. “SELF REFLECTING AND LOOKING FOR THE PATH FORWARD? LOOK NO FURTHER. YOUR CARDS HAVE LINED UP IN ONLY ONE WAY. STRAIGHT DOWN SURREY CANAL ROAD. YOU WILL FIND GROWTH, SOLUTIONS & CHEAP CANS. BE QUICK MIND, YOU KNOW WHERE TO FIND EM” Instagram, December 18, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/DDuj-dJgS-y/

T he topics discussed in Georg Simmel’s essay The Metropolis and Mental Life, can inform us on the dynamics at play within these scattered communities. Written at the start of the 20th century, Simmel attempts to unravel the consequences on the individual within the abrupt changes brought by the Industrial Revolution. The overwhelming stimuli of the modern city is described for its exhausting effect, toning down the individual to its characteristic blasé outlook. This new scale however, pushes one to being anonymous, granting a renewed ability to engage on one’s own terms. Indeed, the limited yet communal size of the village is shattered, to allow one to engage with others on a more voluntary level, albeit less personal. This condition sets the tone for the further connections and behaviours, as Simmel briefly discusses the struggle to maintain a personal autonomy while conforming to larger norms. This autonomy means that one can engage in relationships that are more functional in nature: joining a political group, a social club, an allotment, a co-op. As the quantitative increase of information reaches its limit in the city, individuals have no other choice than to pursue further qualitative distinctions, encouraging the strongest eccentricities, solely in the goal of standing out.

It is inconceivable to navigate its streets without a smartphone, unlocking navigation where flânerie is close to impossible, revealing the incredibly rich network of events, artists studios, workshops, raves, and happenings taking place in inconspicuous industrial buildings. Slightly under-served by TfL, attending such event often entails a light trek, a walk along the Google Maps blue line, down brightly-lit passageways, under brick arches of the former canal, nearby quiet estates and quieter new-builds, through ominous industrial parks. The seeming deprivation of the area is a symptom of its condition of periphery which permeates the area. The proliferation of waste treatment facilities, industrial parks and dark kitchens point out the wealth that is created elsewhere, accumulating the facilities necessary to run London. Conferring the area with an hauntological ecology of being leftover from capitalist expansion, this further drives an eerie feeling of being at the edge of something much bigger, shaping the identity of its streets. Looking at maps reveal industrial lineage stretches to the early 19th century, as the Grand Surrey Canal stretched well into Peckham.2 Remaining streets names such as Senegal Road3, and the nature of businesses in the area reveal the strategic importance of a site in-between the capital and colonies. This explains the destructive bombings targeting the area during WWII, followed by its successive decline towards a post-industrial Britain. Today, the rail lines cutting across any coherent fabric while failing to actually service the area perfectly describes its condition.

2 National Library of Scotland. Georeferenced Maps. “Ordnance Survey 6 inch, 1888-1913.” https://maps.nls.uk/os/ 3 Along with Zampa rd, Stockholm Rd

Hidden away in an industrial estate in South Bermondsey, Venue MOT/Unit 18 has championed young artists and promoters based in and around South East London, providing a local music destination that will take you through into the early hours.4 Such self-describes the iconic Venue MOT, tucked away in two unremarkable prefab units among the messy Orion Business Centre. Behind, the glooming, constantly smoking chimney of the South East London Combined Heat and Power (SELCHP) grounds the venue in an industrial landscape of the periphery, of the cheap and discarded areas of the city. The stillness of such landscape, out of office hours, disturbed only by a few groups of ravers, provides a rare degree of anonymity, stretching to the small, dark and disorienting dance floor created in the unit.

Enigmatic descriptions, eclectic DJ names, and playful graphics form the exterior identity of the club opened in 2018. It appeals to the eternal need for the alternative to dominant, mainstream culture, but in a Britain that has long destroyed the decadent rave culture of the 80s. The contemporary club walks along the fine lines of licensings to provide a renewed, formalised expression of the movement, providing a grassroot space especially for local artists. There is no more paradoxical journey than through the ominous landscape of South Bermondsey, to the secure gates of MOT, complete with pat-downs, ID checks and even facial recognition. Inside, in accordance with the hectic visuals of club nights, the sweaty dance floor provides a space for the strongest eccentricities to thrive, as described by Simmel as the only way to stand out in the quantitative-heavy metropolis.

The weekly conglommeration of ravers in a space of strange, deafening sounds may often be viewed as a form of escapism from the exhaust of daily life. Beyond this reading however, attending such event is for many a search for community, and even care. Despite the duality of the club, the founder Jan Mohammed mantains a non-profit approach, seeking to provide spaces for young people to self-reflect. He was actually encouraged to apply for a license by the police, who saw his ability to care for young people, and the responsibilities it entails.5 Jamie Abraham-Brett’s dissertation6, Bass Bounds: Folk Rave & Diasporic Soudscape in South London’s ‘Bermondsey Triangle’ contextualises the club’s identity within the colonial routes of the former Grand Surrey Canal, creating a hauntological ecology for “future-looking and mostly queer” sounds. Through the prism of folklore, the dissertation unveils the migratory routes of diasporic sounds, situating MOT in an “authentic sonic lineages through the vestiges of a colonial past”. As such, the multiplicity of cultures and their actualisation within the sonic space make a widely opened environment, the dancefloor offering a “cradle of acceptance for whatever you are feeling”.

4 “Venue MOT.” Resident Advisor, ra.co/clubs/156290. Accessed 4 Jan. 2025.

5 Bradshaw, Mitchell, and Dan Loane. “Venue MOT - Jan.” South Side, Cautionary Tales, no. 3, Oct. 2024.

6 Abraham-Brett, Jamie. “Bass Bounds: Folk-Rave & Diasporic Soundscape in South London’s ‘Bermondsey Triangle’.” University of Hertfordshire, 2023.

The neighbouring venue, Ormside Projects further supports this idea of a new contemporary clubbing scene. It also occupies a small unit, number 36, within a larger industrial space, the Penarth centre, a direct neighbour to the Southwark Recycling Centre. The club has chosen to prioritise an extensive array of artists that use the space not just as fun rave, but a space for performance. It strays away from the hedonistic idea of raving, but rather is grounded within a deeply urban culture of celebrating diversity in the expression and enjoyment of art. Indeed, Ormside hosts club nights as well as workshops, and even a residency program supported by Arts Council England.7 It would be simplistic to reduce attendance as mere escapism, as the space and performances is permeated by current events, as illustrated by a fundraising night in October 2024, collecting £7,465 for Medical Aid for Palestinians7. Such enterprises culminate during the yearly South Bermondsey Art Trail, which opens up more than 40 artist studios to the public, in which MOT, Ormside, and Avalon play crucial role in entertaining the festival.

Venue MOT and Ormside Projects are pioneering a response to the dreaded nightlife crisis affecting Britain and its economy. It feeds into a seemingly decades old need for young people not just to gather, but to find a place of the alternative. A 1970 study of an Inslington high-rise neighbourhood8 stipulates on the need for teenagers to find territory, as a way to retrieve the informal control originally performed by the street. Past the eerie journey through South Bermondsey, placing one in upmost anynomity, the venues provides the conditions for this belonging to emerge. The smallness of the space reflects the thightnes of its organisation, one focusing on local artists and promoters. An attempt to generate an identity out of the seeming deprivation and unspecificity of the area, claiming a South-East London culture, opening up to relationships that are both informal and voluntary.

7 “Collective Freedom: A Night Raising Funds for Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP).” Ormside Projects, 27 Oct. 2023

8 Street Aid. Covent Garden Proposed Redevelopment: Case Presented by Street Aid, with New Horizons, the Soho Project, and Space Ltd/ At the Public Enquiry before Mr Charles Hilton, Held between 6 and 16 September 1971. 1971.

Every September, the Sanford block party turns Britain’s first purpose-built housing co-op into a bustling open-air festival. Nestled between splitting Overgound branches and an estate, this self-contained community opens its door and hospitality to host a most diverse program. Gigs and performances set the pace for the night, complete with cheap pints, a warm fire pit to sit around, and eclectic decors. The stepped wooden planks of the bike shed turn into an open-air auditorium to chat and mingle. After midnight, the party invites itself in the interiors of the 14 houses forming the co-op, as crowds gather around DJ sets directly in the shared domestic space, stretching the party well into the night. Uniquely in London, yearly meeting is not policed, gated nor monetised, rather relying on a feeling of shared responsibility.

Following the seven principles of the Rochdale experiment, its founding members sought to break the isolation created by the big city, seeing a brownfield site in Lewisham as a cheap opportunity to create “More than a place to live”.9 The coop has only become increasingly relevant in 21st century London, detaching itself from private, speculative markets, offering a viable alternative. As a room in a shared house goes for £310/month10, the waiting list is consequentially enormous. As such, the coop operates a rigorous application process, requiring two references, that would lead to an interview to join the coop, followed by another to be placed in the right house. This describes Simmel’s take on the formation of political and kinship groups, as a closely coherent circle, somewhat limiting personal autonomy to the aversion from other circles. As the co-op expands however, this multi-step process opens the opportunity of voluntary association to a greater number.

T hese criterias leave little to no room for random and unwanted associations, based on income for example, but carefully select members to craft a diverse community of like-minded people. Members are expected to contribute to the life of the co-op, also performing tasks such as gardening, planning, administration and maintenance. An expression of mutual aid, artificially created within its circle, enabling sharing resources and exchanging skills, and even conflict mitigation where a member could step in to resolve or attenuate conflict between others. Robin’s explicative videos12 on SanfordcoopTV demonstrate a duty of care from tenants for the built environment, their peers, and the organisation, where his knowledge and study may contribute to collective decisions around maintenance and expansion. This model is supported spatially by the rather traditional typology of houses, providing thresholds from public to private spheres. The garden and street, Sanford Walk, serves as an intermediary between the houses and the public, welcoming outsiders and enabling the domestic to spill outwards. Houses themselves sub-divide the coop in smaller groups, where generous kitchens and living rooms on the ground floor allow for a smaller scale shared everyday life. Rooms upstairs are 10 sqm and single-occupancy, providing an intimate cell for a member to grasp upon their own private life. These thresholds could explain that Sanford remains a thriving community decades later,

9 More Than a Place to Live, BBC, 1974

10 “About Sanford.” About Sanford | Sanford Housing Co-Operative, sanford.coop/about 11 Simmel, Georg, “The Metropolis and Social Life”. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited by Kurt H. Wolff. Free Press, 1950. 188

12 SanfordCoopTV. “Robin’s Overall Maintenance Summary.” YouTube, 9 Jan. 2015

allowing one to retain autonomy and intimacy, but conferring informal responsibility based on mutual aid between members, and finally, periodically opening up outside of this circle.

Sanford also works closely with the neighbouring Avalon cafe, a space opened in 2021, responding to a need for flexible yet open-ended spaces to gather. From cafe serving breakfast to local workers to gig space for art performances at night, the cafe has also hosted workshops and talks regarding establishing and managing co-operative living. Adjacent to a car-heavy roundabout and the SELCHP incinerator, the cafe manages to build on the ideological proximity with similar neighbouring venues, fed by a stream of alternative-savy Goldsmith students. In this pattern devoid of markets, high streets and even pedestrian footfall, places become neighbours through association, inhabiting similar conditions, and thus promoting similar agendas.

While this essay argues the broken up urban fabric of the area enables communities to set up and thrive, it has brought little consideration for the many estates, the most dominant form of housing in the area. Its fundamental organisation reverts to a much larger scale, that of the council or state, often far removed from the realities on the ground. However, the lack of traditional streets organising community is no hinderance for the two larger estates, Tustin and Winslade, building upon the deeply-anchored ties between residents to strengthen the wider community.

The Tustin estate, a postwar complex of 3 tower blocks and sprawling low to mid-density homes is currently undergoing the first phase of its regeneration. Southwark council, as the Borough with the highest share of social housing, is a leader in estate regeneration in London. Its early 2000s approach, particularly for Elephant and castle and Aylesbury estate, has been under fiery criticism for the destruction and displacement caused by merged public and private interests. Perhaps attempting to move away from this polarising process, in turn hindering the project altogether, the Tustin estate regeneration may become an example of resident-driven planning. Started in 2019, the Resident’s Manifesto13 outlines the points discusses and agreed on by residents, to which the council is held liable. In gathering the residents and in coming up with this document, the exchange and discussions built consensus for the project, leading to the residents ballot gathering 87% approval, for a 63% voter turnout.

Appointed two years after the start of the regeneration, the architects are expected to continue working with residents, retaining transparency, and customising the design process. Drop-ins, free breakfast, and consultation events organised by a third-party engagement team, Urban Symbiotics, rhythm the design process. The momentum created over the past 5 years has turned the quieter estate into a thriving community, invited to meet frequently and keeping an eye on another. These seemingly abstract relationships remain however enshrined in the residents manifesto, especially points about phased rehousing, and social events upon moving-in, preventing “us versus them” relationships. As the years go by however, community involvement may stretch further than only the design, but could become less specific and more long-term.

8. Tustin Estate Resdients Manifesto. Credits: footnote 13

13 Tustin Community Association, and Southwark Council. “Tustin Estate Residents Manifesto - Southwark Council Response.” 2020.

9.Credits: Bridgehouse Gardens on Instagram. Jan 1, 2025

A much more informal, and grassroot expression of association is pioneered at the nearby Winslade estate. Grow Lewisham is a network of volunteers seeking to co-create spaces for communities along the Old Kent Road regeneration, focusing on themes of community infrastructure and land. One of its three sites, Bridgehouse Gardens14, activates the existing pavement as a public space, where food growing, education, and recreation serves as catalysts for cohesion. The name comes from the nearby meadows, an untouched hill with views on the City and Canary Wharf, reminding us of the area’s position among financial centres.

The informal network of volunteers allow for flexible and open participation in its goals. It allows complete outsiders to drop-by, on the basis of their motivations or political engagement, enabling one to associate freely, in relationships more functional in nature. As a result of the informality of its network, having an anchored and consistent space to meet and discuss is central to the perpetuation of such community. Summertime gathering allows for long planks to be easily set up on trestles, a collaborative and interactive table. Climatic conditions however generated the need for an enclosed gathering space to be shaped quickly, becoming a self-build project for the community. The small wooden pavilion was just completed after months of running a weekly carpentry session, open to all levels. Sharing skills becomes a tool in order to spread out the work among participants, empowering them but also materialising the community needs.

The group also runs a gardening session on Saturdays, building upon commitments around land and growth. Grow Lewisham was set up to map out spaces owned by the council, which could be used for growing foods. A form of guerilla cartography is used to categorise patches of land that can be observed from walking around the sub-divided map of Lewisham, which will serve to establish which of these are owned by the council, and thus lobbying it accordingly. A similar initiative was started in Hull15, the Right to Grow motion having passed unanimously, setting up the legal framework and assistance to make such enterprise possible. These experiments illustrate the attempts to repair the alienating relationships that have created city modern life. Their focus reverts back to the essential act of human civilisation of growing food, using ownership and control over land as means of empowerment. The bridgehouse garden’s more long-term goal is to provide growing spaces all around the council-owned estate, a way for tenants to settle in and ground themselves.

14 “Bridgehouse Gardens.” GROW LEWISHAM, www.growlewisham.com/bridgehouse-gardens. Accessed 4 Jan. 2025. 15 “Right to Grow: Progress in Hull.” Incredible Edible, 1 May 2024, www.incredibleedible.org.uk/news/right-to-growprogress-in-hull/.

T his essay demonstrates that the multiplicity of association emanating from the urban landscape of South Bermondsey can be understood from Simmel’s reading of the shock brought by the Industrial Revolution. As such, in applying this theory to the current dynamics of a city deeply rooted within neoliberal discourse, the protagonists of this essay become the product of the similar cutthroat attributes. The spaces of South Bermondsey, leftover and integral to the expansion of London, become a haven for people undergoing a similar condition, enabling communities to thrive in an otherwise prohibitively expensive city. From the ravers seeking an inclusive place, perhaps only to the duration of night, to those choosing an alternative to private housing as a way of life, but also through council estate tenants, deprived of a similar choice but associating nonetheless. Shining a light on the existence of those places helps counter the seeming ‘nothingness’ of an area prone to regeneration, granting its eerie and gloomy streets with an expiry date. It is left to see what will happen to these established groups, as some may embrace their temporal nature, while others may put their resilience to the test.

10. Render showing the proposed skyscapers on top of Orion Business centre, part of developer Renewal’s £1.9bn regeneration. Credits: Factory Fifteen

“Here’s What South Bermondsey Could Look like after Its £1.9 Billion Redevelopment.” Southwark News, 4 Sept. 2024

Bibliography

Disclaimer:

Much of the information gathered in this essay also comes from first hand accounts from attending the previously mentioned places. Additional understanding of the Tustin estate comes from my work as engagement collaborator for Urban Symbiotics, which allowed me to gather resident’s thoughts, but I did not transcribe here.

“About Sanford.” About Sanford | Sanford Housing Co-Operative, sanford.coop/about. Accessed 4 Jan. 2025.

Abraham-Brett, Jamie. “Bass Bounds: Folk-Rave & Diasporic Soundscape in South London’s ‘Bermondsey Triangle’.” University of Hertfordshire, 2023.

Bradshaw, Mitchell, and Dan Loane. “Venue MOT - Jan.” South Side, Cautionary Tales, no. 3, Oct. 2024.

“Bridgehouse Gardens.” GROW LEWISHAM, www.growlewisham.com/bridgehouse-gardens. Accessed 4 Jan. 2025.

“Collective Freedom: A Night Raising Funds for Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP).” Ormside Projects, 27 Oct. 2023, www.ormside.co.uk/collective-freedom.

“Here’s What South Bermondsey Could Look like after Its £1.9 Billion Redevelopment.” Southwark News, 4 Sept. 2024, southwarknews.co.uk/area/bermondsey/heres-what-south-bermondsey-couldlook-like-after-its-1-9-billion-redevelopment/.

National Library of Scotland. Georeferenced Maps. “Ordnance Survey 6 inch, 1888-1913.” https:// maps.nls.uk/os/

More Than a Place to Live, BBC, 1974, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iKBKBbbmups. Accessed 2024.

“Ormside Residency Program.” Ormside Projects, 2024, www.ormside.co.uk/collective-freedom.

“Right to Grow: Progress in Hull.” Incredible Edible, 1 May 2024, www.incredibleedible.org.uk/ news/right-to-grow-progress-in-hull/.

SanfordCoopTV. “Robin’s Overall Maintenance Summary.” YouTube, 9 Jan. 2015, www.youtube. com/watch?v=wlnk3D_Umeg&t=67s.

Sid Motion Gallery, and Charlie Billingham. South Bermondsey Art Trail. 2022. Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

Simmel, Georg, “The Metropolis and Social Life”. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited by Kurt H. Wolff. Free Press, 1950. 188

Street Aid. Covent Garden Proposed Redevelopment: Case Presented by Street Aid, with New Horizons, the Soho Project, and Space Ltd/ At the Public Enquiry before Mr Charles Hilton, Held between 6 and 16 September 1971. 1971.

Tustin Community Association, and Southwark Council. “Tustin Estate Residents ManifestoSouth-wark Council Response.” 2020.

@venuemot. “SELF REFLECTING AND LOOKING FOR THE PATH FORWARD? LOOK NO FURTHER. YOUR CARDS HAVE LINED UP IN ONLY ONE WAY STRAIGHT DOWN SURREY CANAL ROAD. YOU WILL FIND GROWTH, SOLUTIONS & CHEAP CANS. BE QUICK MIND, YOU KNOW WHERE TO FIND EM” Instagram, December 18, 2024.