Friday 20 January 2023 —

Saturday 25 March 2023

11am–7pm GMT

AA Gallery, 36 Bedford Square

Friday 20 January 2023 —

Saturday 25 March 2023

11am–7pm GMT

AA Gallery, 36 Bedford Square

Following its establishment in 1953 at the Architectural Association (AA) in London, the Department of Tropical Studies (DTS) exported climate-based methodologies of architectural design and development planning to countries in the Global South. These methodologies were subsequently developed as the DTS reshaped architectural institutions and their curricula, regulated planning practice and legislation, and trained leading architects in and from these regions. The bulk of the DTS’s archive within the AA Collections consists of the papers of its departmental directors, with more than 50 boxes containing piles of planning reports written from London for architecture in countries all over the Global South.

The DTS archive appears at first glance to be a coherent whole without much space for dissent. However, a truly complete DTS archive would need to comprise material from all the people across the globe whose hard work is hardly found in the current archive, including the artists, architects, typists, graphic designers, masons, surveyors and others who formed and participated in the DTS. These contributors are often unacknowledged or excluded from the archive; in some cases, this is by their own choice.

This exhibition explores the contrast between two archives, each of which reveals an opposing understanding of ecology – taken here to mean relations between living beings and the environment – in the context of architecture. One of these is the current DTS archive, which presents climate-based architectural design, representations of hostile tropical suns and Western abstract expressionism alongside careless abstractions and displacements of ecologically meaningful Adinkra symbols and African sculptures. The other, a potential DTS archive, presents entanglements between the human, the non-human and the environmental that respond to contemporary global architectural concerns.

Through critical strategies articulated within the Front Members’ Room and AA Gallery – As Hardly Found and Potential History, Critical Fabulations, Fabulography – the exhibition reveals stories that highlight the rich and diverse ecological approaches contributed by ‘peripherised’ figures within the DTS. An ensemble of archival documents sits alongside artworks by Magda Cordell, Avinash Chandra, Bruce Onobrakpeya and Susanne Wenger, among others, who worked with DTS architects. These are accompanied by archival reconstructions and commissioned works by artists Ato Jackson and Mariana Castillo Deball that explore marks in the DTS archive as potential histories for alternative futures.

What if the archive is classified through the labour involved in creating the documents it contains? How do we represent the hard work of those unnamed and underpaid friends, partners, students and assistants – often female – who typed and designed the archival documents?

The “as found”, where the art is in the picking up, turning over and putting with…

the “as [hardly] found” […, where] all those marks that constitute remembrances in a[n... archive] are to be read through finding out how the existing built fabric of the [… archive] had come to be as it was.’

Emphasis

‘the “found” where the art is in the process and the watchful eye…Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, ‘The “As Found” and the “Found”’, in The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty, edited by David Robbins (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990). and fictional edits in italics by Albert Brenchat-Aguilar.

Adinkra is a symbolic language created by the Akan peoples of Ghana. Unacknowledged Ghanaian masons built blocks of concrete designed by AA architect, councillor and future president Jane Drew for schools in the country; these blocks made use of Adinkra, often in the form of abstraction and disambiguation of this meaningful graphic language to fit modernist scientific standards.

The final appendix within the proceedings of the Conference of Tropical Architecture in 1953 – a precursor to the DTS – transcribes a talk by its secretary, architecture student Adedokun Adeyemi. This talk has often been summarised as a complaint that northern-climate-based models of architectural design were irrelevant to architects practicing in warmer regions. However, Adeyemi also expressed concerns related to class, privilege and cultural diversity, and advocated for a number of approaches, among them the incorporation of ‘allied arts’ in architectural practice; the coexistence of Beaux Arts and local architectural histories; the development of site-specific critical approaches; and the surveying of canonical and local architectures, crafts and materials. The names of many future architectural leaders from the Global South can be found in the question-and-answer sections of these conference proceedings, yet none of these individuals were among the main speakers at the event.

At the AA in 1964, DTS director Otto Koenigsberger gave a lecture about planning methods for the Global South titled ‘Action Planning’, accompanied by a drawing in the ‘action painting’ style by AA student Justin Desyllas. During this period, some DTS architects also decorated their homes and offices with Eduardo Paolozzi’s action painting-inspired designs.

In a transcript of this lecture, Koenigsberger juxtaposed the ‘Action Planning’ drawing with a photograph from the DTS’s ten-year anniversary celebration, which seems to show him explaining panels on the wall to DTS student Albert Kwetia Amartey – future cofounder of the Ghana Institute of Architects –and three unidentified women. The photograph is deceptive; Amartey required no explanation of the panels, as they were his own work and that of his colleagues. In a further manipulation of the image when it was published, Koenigsberger trimmed and rotated the photo to place himself at Amartey’s height.

The AA’s collection of projector slides presents looted sculptures from Africa, Oceania and Latin America, credited to their captors – usually the British Museum. Meanwhile, the work of Jackson Pollock and Eduardo Paolozzi –the Western artists whose work was most influential within the DTS – is so sought-after that many of their projector slides within the AA Collections have disappeared.

From 1954, Architectural Design was edited by DTS architects who published their work in the Global South within the journal. Each issue from 1956 onwards depicted drawings ‘by artists who have something to say to architects’, which were included so that ‘architects will be able to compile a list of artists whose work they might like to use in their buildings’ (Architectural Design, 1956, p 30). Eduardo Paolozzi, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and many other European artists contributed to this initiative, while artists such as Avinash Chandra, Demas Nwoko, Bruce Onobrakpeya and Susanne Wenger were ignored as provincial, despite their work reflecting the ecological and intellectual ambitions of architects of the time. These artists had all collaborated with DTS architects within different buildings and publications internationally.

The exhibits in this room conclude with two graphic expressions of the DTS’s vision of the Global South as a hostile space. The first example takes the form of emblematic, oversized suns that appear on reports, posters and manuals of architecture. The second is the expression of an attitude that projects the ‘North temperate zone, home of modern civilisation, into the centre, and illustrates its connections to the rest of the world’ (see note at the bottom of the Atlas drawing exhibited in the Front Members’ Room).

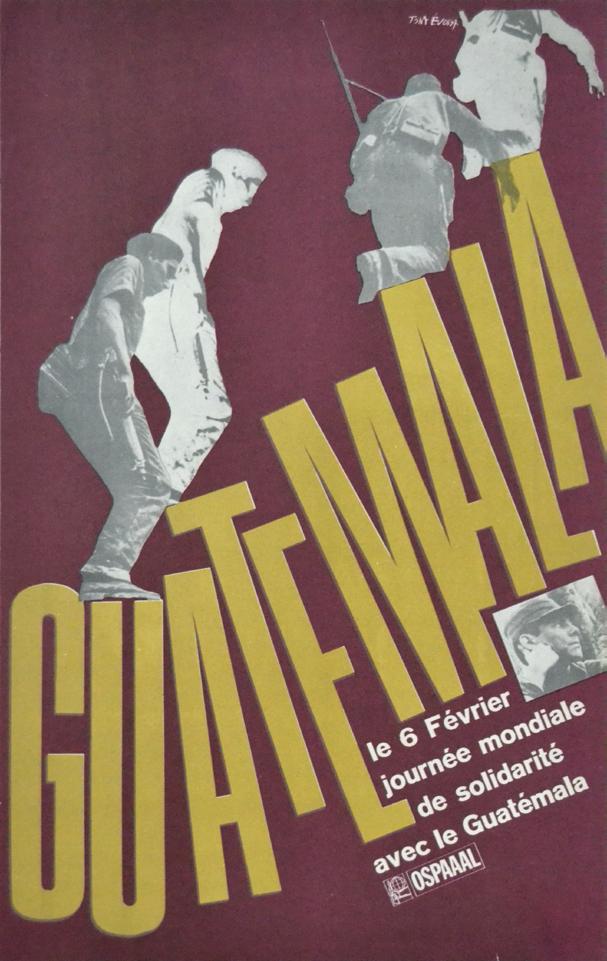

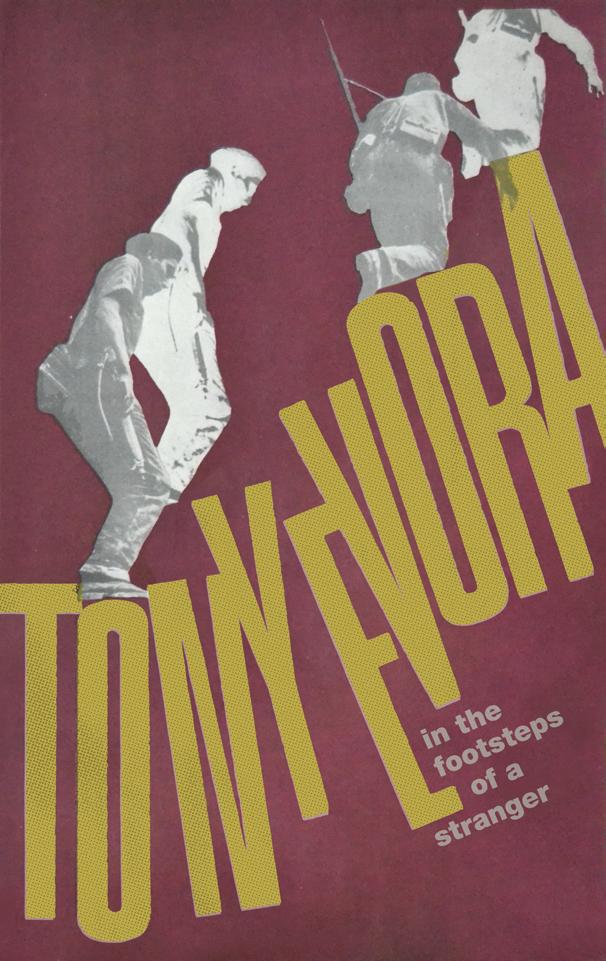

In response, a poster for the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAL) by activist Tony Évora, graphic designer of the DTS’s Manual of Tropical Architecture, is presented and reinterpreted by graphic designer Pepe Menéndez. This intervention draws attention to the hardly found archive of Tony Évora: a significant figure in both Cuban and British graphic arts, and a defender of other forms of international relations.

Can we reimagine the archive through the diversity of the hardly found ecological approaches that exist within it?

How can these coexist in the present and how might they be projected into the future?

‘ POTENTIAL HISTORY is a form of being with others, both living and dead, across time, against the separation of the past from the present, colonised peoples from their worlds and possessions, and history from politics.’

– Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2019), p 43.

CRITICAL FABULATIONS aim ‘to displace the received or authorised account … to imagine what might have happened or might have been said or might have been done.’

– Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, in Small Axe , no 12 (2), 2008, p 11.

FABULOGRAPHY is ‘a practice of projecting freely, associatively into the gaps of the past to retrieve in any form –song, dance, film, text, drawing, recipe –something of what has been lost.’

– Priya Basil, ‘Writing to Life’, in Dan Hicks, ‘Necrography: Death-Writing in the Colonial Museum’, British Art Studies , Issue 19, 2021.

In a 2022 interview, Bruce Onobrakpeya said “I use art to develop the environment”. Sixty years earlier, in 1961, he was commissioned to create a mural for the University of Lagos’s Temporary Accommodation Building at Idi Araba, designed by Alan Vaughan-Richards of the Architects Co-Partnership (ACP) – a collective involved in both lecturing and leading the AA at that time. Within the mural, Onobrakpeya reflected upon Lagos’s ‘industry and trade, transport, education, art, dancing and recreation’ (West African Builder and Architect, 1963, p 5). Since the early 1960s, his experiments with printmaking, reliefs and textile designs have constructed collective scenes of humans and non-humans shaping the environment, and vice versa.

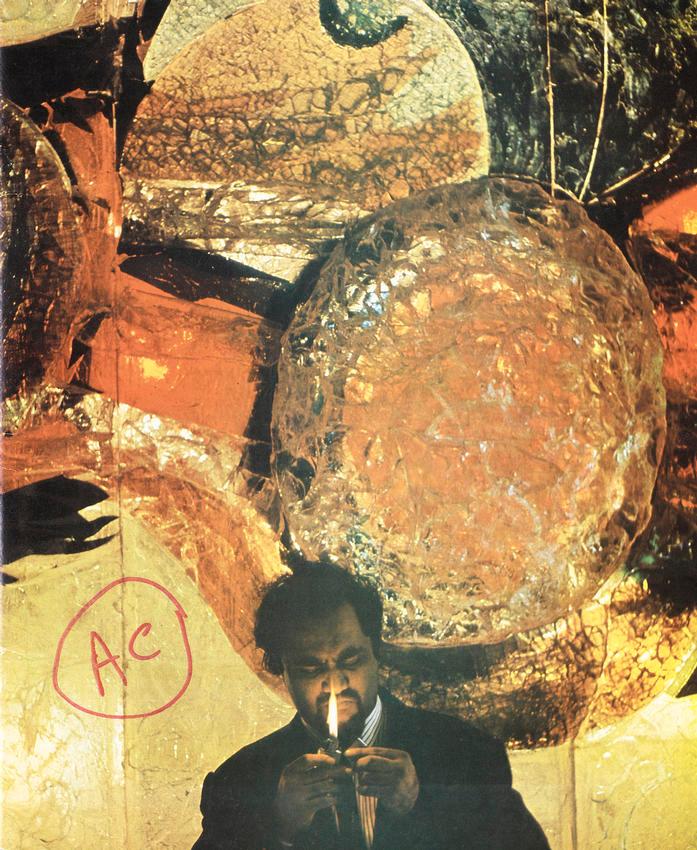

In 1964, Avinash Chandra posed in front of his mural Fire, commissioned by DTS lecturer Jane Drew for the Pilkington Glass Factory in St Helens, UK. Chandra had been painting compositions of moons, architectures and human figures to escape London’s hostile environment:

‘I went into what I call a head-situation. I disappeared into my attic room for a long time, where I would spend a lot of time just thinking … I put my head into another head, which was the attic, and some time later I began to paint heads; and I painted a lot of heads. I was trying to clarify what all this thing was about.’

– Avinash Chandra, in Rasheed Araeen, ‘Conversation with Avinash Chandra’, Third Text, no 2.3–4, 1988, p 71.

Chandra is captured here resting on the mural, lighting a cigar; his eyes looking at the flame, he is pretending to ignore the camera and his environment. The image presents one of Chandra’s aforementioned ‘head-situations’: it depicts an ecology of the self, of the home and of those who ignored London’s hostile environment and instead created one for themselves.

In 1958, the AA hosted Chandra’s second solo exhibition, although records of this show are lacking. In response to this absence, AA students have reimagined posters, invitation cards and the space of the exhibition, constructing new archival apparatuses to reactivate this event.

The Bristol Hotel was designed by ACP and completed in Lagos Island, Nigeria, in 1961. It was conceived as Lagos’s ‘first class hotel’ and was built on Oniru land occupied at the turn of the 20th century. Susanne Wenger was commissioned to create a three-metre-square mosaic on the modernist exterior façade of the ground-floor restaurant. In it she depicts a human-nonhuman ecology, covering and confronting the advertisement that appears on the restaurant’s ‘Bristol Fashion’ menu. ACP and its affiliated architects also commissioned other artists for the project such as Festus Idehen, Yusuf Grillo and Demas Nwoko.

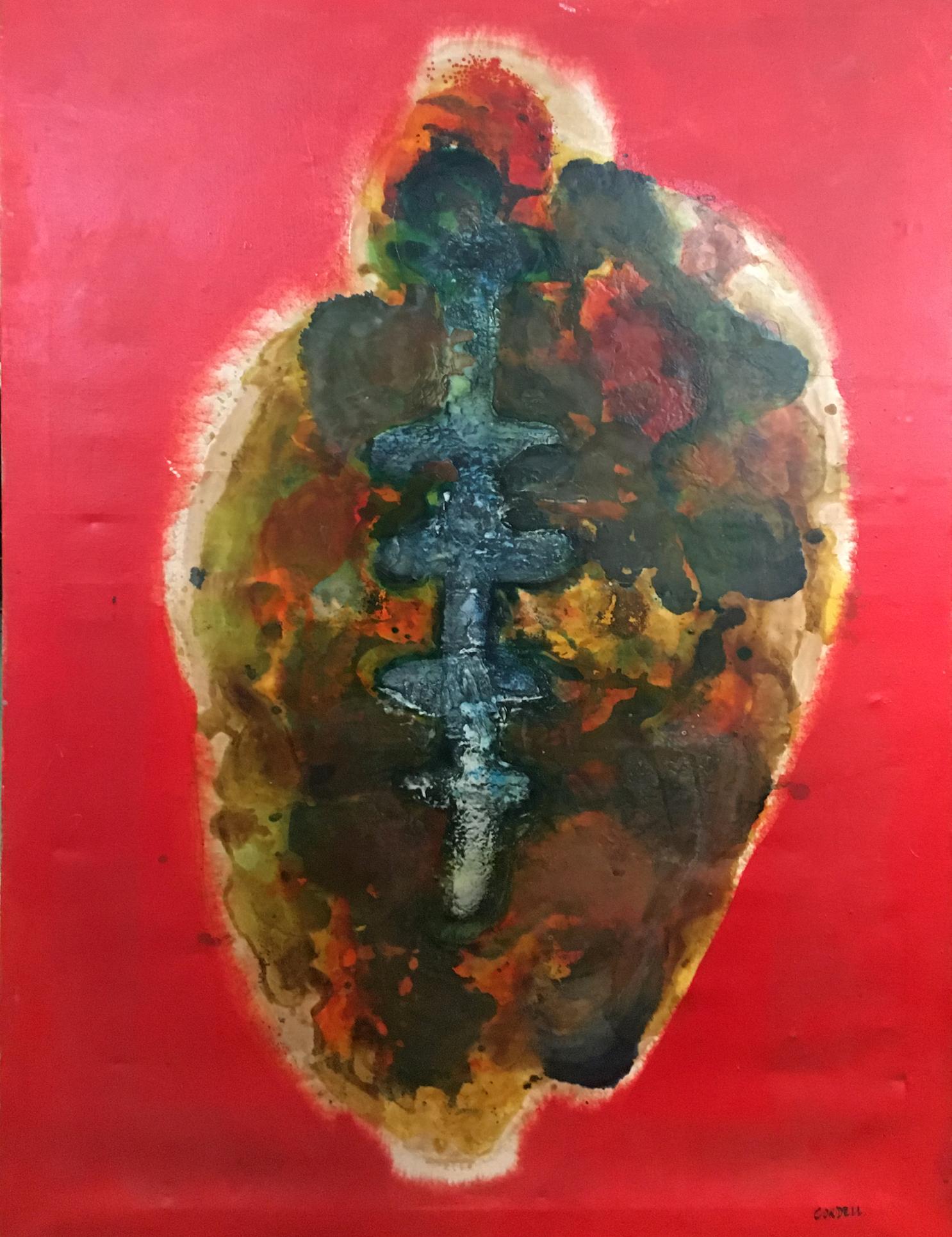

In the AA Archive, a painting by Magda Cordell lies uncatalogued with a sticker on the back which misspells her name. Titled Presences n. tbd, the painting speaks of the past as much as the future, presenting a forward-looking image of technology-induced biological resilience and reparation; it is part of a series by Cordell in which a skeletal female figure displays the scars of wartime trauma. Cordell would later become an international planner herself, publishing on topics such as the rights of children and women and the provision of basic needs.

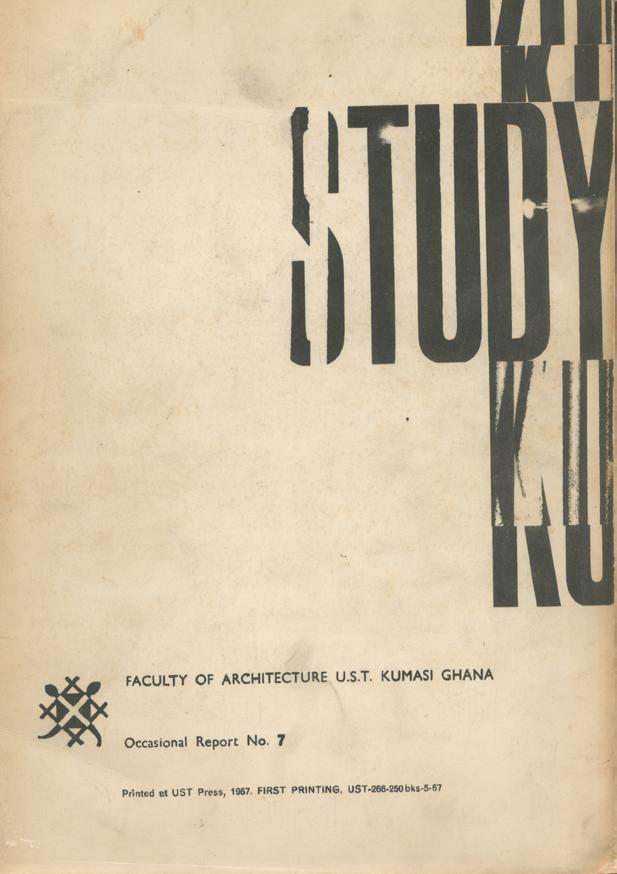

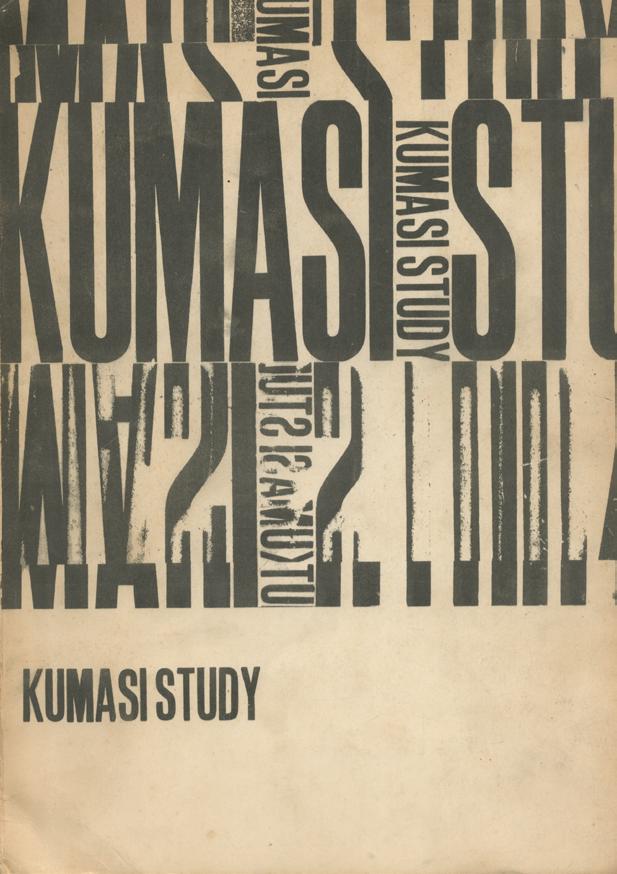

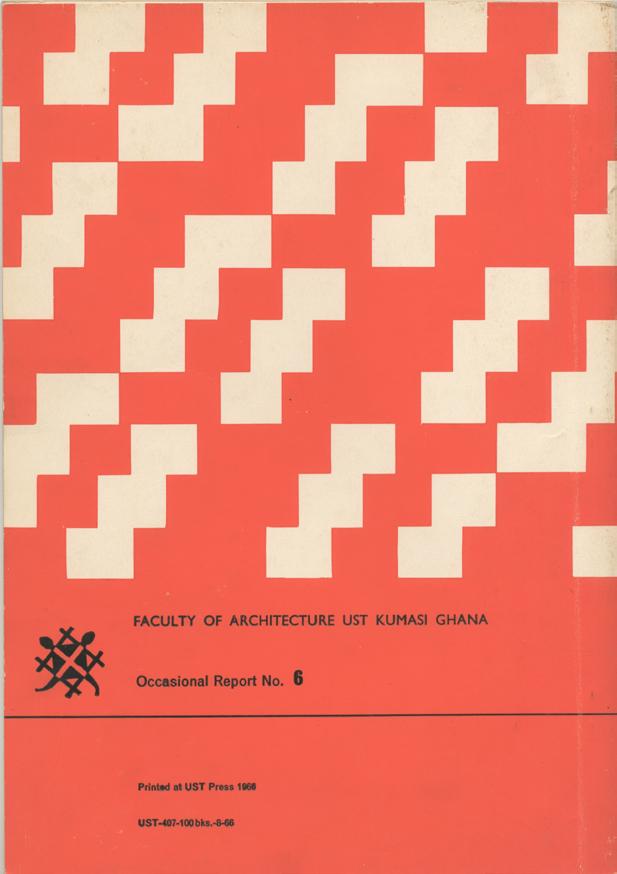

At least thirteen Occasional Reports were written in the 1960s at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi (KNUST) by the international community of its Faculty of Architecture. Copies of nine of these reports are held in the AA Archive, whereas only two of these can be found in Ghanaian archives. Their graphic design presents the perspective of lesserknown actors that shape the reader’s encounter with the document.

A red and white silkscreen print spreads like computational code on the cover of the fifth report, devoted to Community Building in the Upper Region of Ghana. Designed by Shelagh Wakely in her teachers’ bungalows at KNUST, this cover reflects Wakely’s practice with Ghanaian textiles and the interiors and clothing she designed in Ghana in the 1960s.

The seventh report focuses on the city of Kum-asi: ‘the soil under the Kum tree, the tree of life’ (Kwafo K Adarkwa and John Post, The Fate of the Tree, Purdue University Press, 2003). Capitalised, the word ‘KUMASI’ grows from the trunk that forms the letter ‘I’. The phrase ‘KUMASI STUDY’ can be read forward and backward, implying both that Kumasi is studied and that Kumasi, as the uncountable soil under a tree of life, studies itself. John Bunch, John K Abban, Anno Okae and T Okyere designed the cover, typed its contents and took photographs of social events in Kumasi’s markets for the report.

Through his surface-based work, contemporary artist Ato Jackson conjures the architectural and artistic premise of blaxTARLINES – a transgenerational community of artists, curators and writers at KNUST that seeks to create silent revolutions, by facilitating a stealthy exchange of knowledge within oppressed areas of the city. Jackson reconstructs the KNUST reports that are missing from collections in the UK and Ghana, taking blaxTARLINES’ revolutionary approach to the archive itself. Here, he inserts himself in ‘revolutionary time’: acts for revolution that replay, redress and destabilise historical narratives.

Mariana Castillo Deball has developed her own fabulographic practice following theories on object biography (the life of the object) and necrography (the violence that an object has been involved in). She investigates and engages with archives of all kinds, from Roman ruins to Spanish colonial codices and British archaeological explorations. In this exhibition, Castillo Deball reflects upon the disposition of papers in archival boxes, reducing them to fragments and remaking them from pieces of the documents they contained. Her work engages with those who make the archive, bringing them to the forefront of the visitor’s encounter with its contents.

This exhibition is the result of the work of a large team of contributors within and beyond the AA whose input has shaped its final form.. They have created display cases that resemble vibrant archival objects; brought forth the polyphony of voices in this catalogue, making its stories accessible; challenged hegemonic discourses and explored new forms of archival making; and developed a graphic identity that compliments the artworks on display. This work is further supported by the people who will take care of the exhibition and its contents throughout its duration.

This exhibition has been made possible thanks to the kind support of the Architectural Association (AA), the Bartlett School of Architecture’s Architecture Research Fund, the Henry Moore Foundation, the Graham Foundation, the Chase Doctoral Partnership at the Birkbeck School of Arts and the Architecture Space and Society Centre, the Elephant Trust, Fringe UCL, the Goethe-Institut London and Conservation by Design.

Curator and Curatorial Text: Albert Brenchat-Aguilar

Commissioned Artists: Mariana Castillo Deball, Ato Jackson

Assistant Curator and Assistant Designer: Ella Mahalia Adu

Advisors: Mark Crinson, Sally Stott, Pat Wakely

AA Archives: Ed Bottoms, Amy Finn

AA Public Programme and Exhibitions: Harriet Jennings, Manijeh Verghese

Exhibition Build: AA Facilities

Graphic Design: AA Communications Studio