Implications of lipids and modified lipoproteins in atherogenesis: From mechanisms towards novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets

Edited by Alexander Akhmedov, Chu-Huang Chen and Tatsuya Sawamura

Published in Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

The copyright in the text of individual articles in this ebook is the property of their respective authors or their respective institutions or funders. The copyright in graphics and images within each article may be subject to copyright of other parties. In both cases this is subject to a license granted to Frontiers.

The compilation of articles constituting this ebook is the property of Frontiers.

Each article within this ebook, and the ebook itself, are published under the most recent version of the Creative Commons CC-BY licence. The version current at the date of publication of this ebook is CC-BY 4.0. If the CC-BY licence is updated, the licence granted by Frontiers is automatically updated to the new version.

When exercising any right under the CC-BY licence, Frontiers must be attributed as the original publisher of the article or ebook, as applicable.

Authors have the responsibility of ensuring that any graphics or other materials which are the property of others may be included in the CC-BY licence, but this should be checked before relying on the CC-BY licence to reproduce those materials. Any copyright notices relating to those materials must be complied with.

Copyright and source acknowledgement notices may not be removed and must be displayed in any copy, derivative work or partial copy which includes the elements in question.

All copyright, and all rights therein, are protected by national and international copyright laws. The above represents a summary only. For further information please read Frontiers’ Conditions for Website Use and Copyright Statement, and the applicable CC-BY licence

ISSN 1664-8714

ISBN 978-2-8325-2973-7

DOI 10.3389/978-2-8325-2973-7

About Frontiers

Frontiers is more than just an open access publisher of scholarly articles: it is a pioneering approach to the world of academia, radically improving the way scholarly research is managed. The grand vision of Frontiers is a world where all people have an equal opportunity to seek, share and generate knowledge. Frontiers provides immediate and permanent online open access to all its publications, but this alone is not enough to realize our grand goals.

Frontiers journal series

The Frontiers journal series is a multi-tier and interdisciplinary set of openaccess, online journals, promising a paradigm shift from the current review, selection and dissemination processes in academic publishing. All Frontiers journals are driven by researchers for researchers; therefore, they constitute a service to the scholarly community. At the same time, the Frontiers journal series operates on a revolutionary invention, the tiered publishing system, initially addressing specific communities of scholars, and gradually climbing up to broader public understanding, thus serving the interests of the lay society, too.

Dedication to quality

Each Frontiers article is a landmark of the highest quality, thanks to genuinely collaborative interactions between authors and review editors, who include some of the world’s best academicians. Research must be certified by peers before entering a stream of knowledge that may eventually reach the public - and shape society; therefore, Frontiers only applies the most rigorous and unbiased reviews. Frontiers revolutionizes research publishing by freely delivering the most outstanding research, evaluated with no bias from both the academic and social point of view. By applying the most advanced information technologies, Frontiers is catapulting scholarly publishing into a new generation.

What are Frontiers Research Topics?

Frontiers Research Topics are very popular trademarks of the Frontiers journals series: they are collections of at least ten articles, all centered on a particular subject. With their unique mix of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Frontiers Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area.

Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author by contacting the Frontiers editorial office: frontiersin.org/about/contact

August 2023 1 frontiersin.org Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

FRONTIERS EBOOK COPYRIGHT STATEMENT

Implications of lipids and modified lipoproteins in atherogenesis: From mechanisms towards novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets

Topic editors

Alexander Akhmedov — University of Zurich, Switzerland

Chu-Huang Chen — Texas Heart Institute, United States

Tatsuya Sawamura — Shinshu University, Japan

Topic coordinator

Simon Kraler — University of Zurich, Switzerland

Citation

Akhmedov, A., Chen, C.-H., Sawamura, T., eds. (2023). Implications of lipids and modified lipoproteins in atherogenesis: From mechanisms towards novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA.

doi: 10.3389/978-2-8325-2973-7

August 2023 2 frontiersin.org Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Table of contents

05 Editorial: Implications of lipids and modified lipoproteins in atherogenesis: from mechanisms towards novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets

Simon Kraler, Tatsuya Sawamura, Grace Yen-Shin Harn, Chu-Huang Chen and Alexander Akhmedov

09 Differential Effects of Genetically Determined Cholesterol Efflux Capacity on Coronary Artery Disease and Ischemic Stroke

Aoming Jin, Mengxing Wang, Weiqi Chen, Hongyi Yan, Xianglong Xiang and Yuesong Pan

17 U-Shaped Relationship of Non-HDL Cholesterol With All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Men Without Statin Therapy

Rui-Xiang Zeng, Jun-Peng Xu, Yong-Jie Kong, Jia-Wei Tan, Li-Heng Guo and Min-Zhou Zhang

27 The accuracy of four formulas for LDL-C calculation at the fasting and postprandial states

Jin Xu, Xiao Du, Shilan Zhang, Qunyan Xiang, Liyuan Zhu and Ling Liu

36 Diabetic dyslipidemia impairs coronary collateral formation: An update

Ying Shen, Xiao Qun Wang, Yang Dai, Yi Xuan Wang, Rui Yan Zhang, Lin Lu, Feng Hua Ding and Wei Feng Shen

47 Physical activity to reduce PCSK9 levels

Amedeo Tirandi, Fabrizio Montecucco and Luca Liberale

54 Pinocytotic engulfment of lipoproteins by macrophages

Takuro Miyazaki

60 Association of remnant cholesterol and lipid parameters with new-onset carotid plaque in Chinese population

Bo Liu, Fangfang Fan, Bo Zheng, Ying Yang, Jia Jia, Pengfei Sun, Yimeng Jiang, Kaiyin Li, Jiahui Liu, Chuyun Chen, Jianping Li, Yan Zhang and Yong Huo

70 Spotlight on very-low-density lipoprotein as a driver of cardiometabolic disorders: Implications for disease

progression and mechanistic insights

Hsiang-Chun Lee, Alexander Akhmedov and Chu-Huang Chen

83 Crosstalk between high-density lipoproteins and endothelial cells in health and disease: Insights into sex-dependent modulation

Elisa Dietrich, Anne Jomard and Elena Osto

102

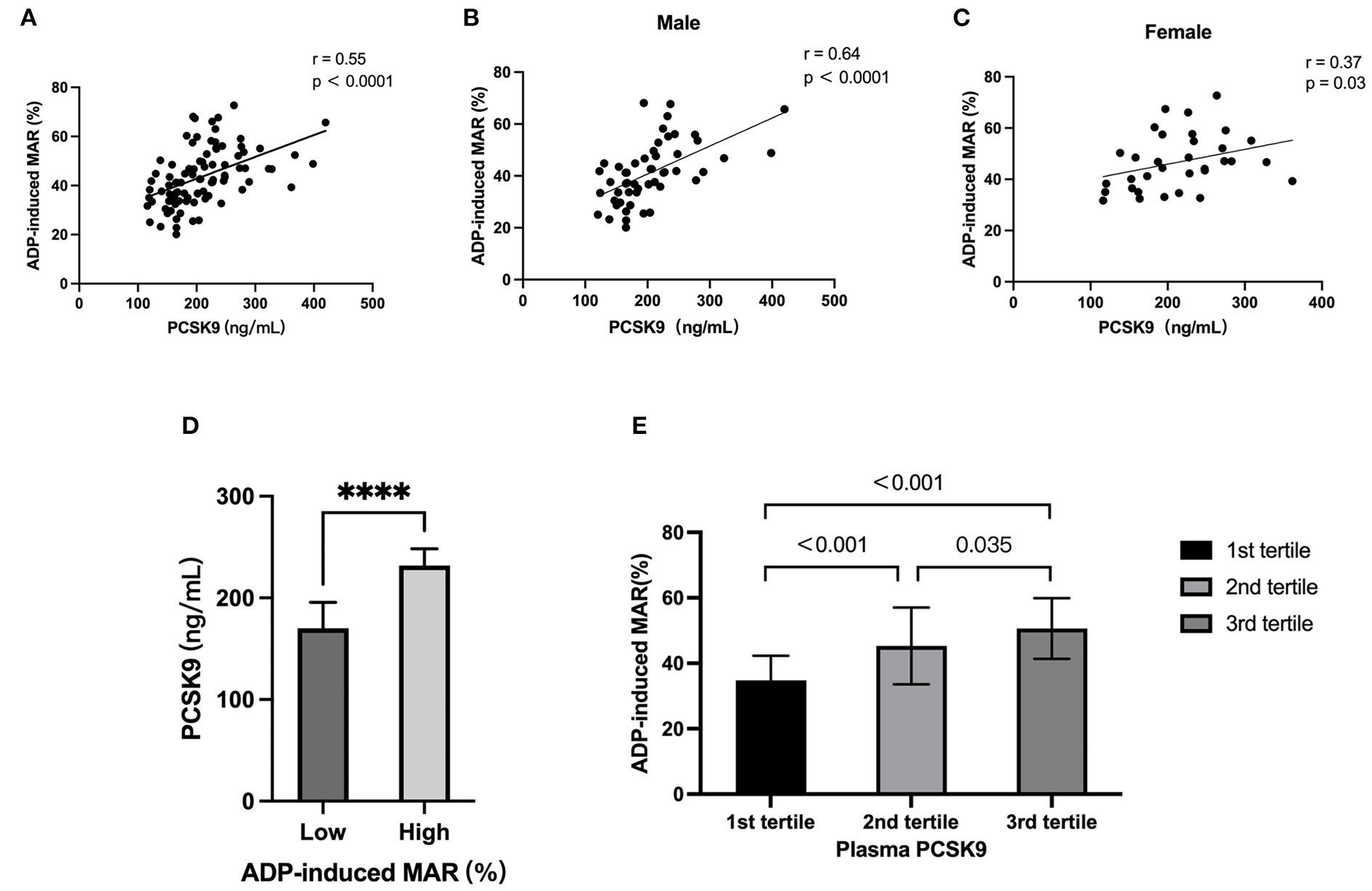

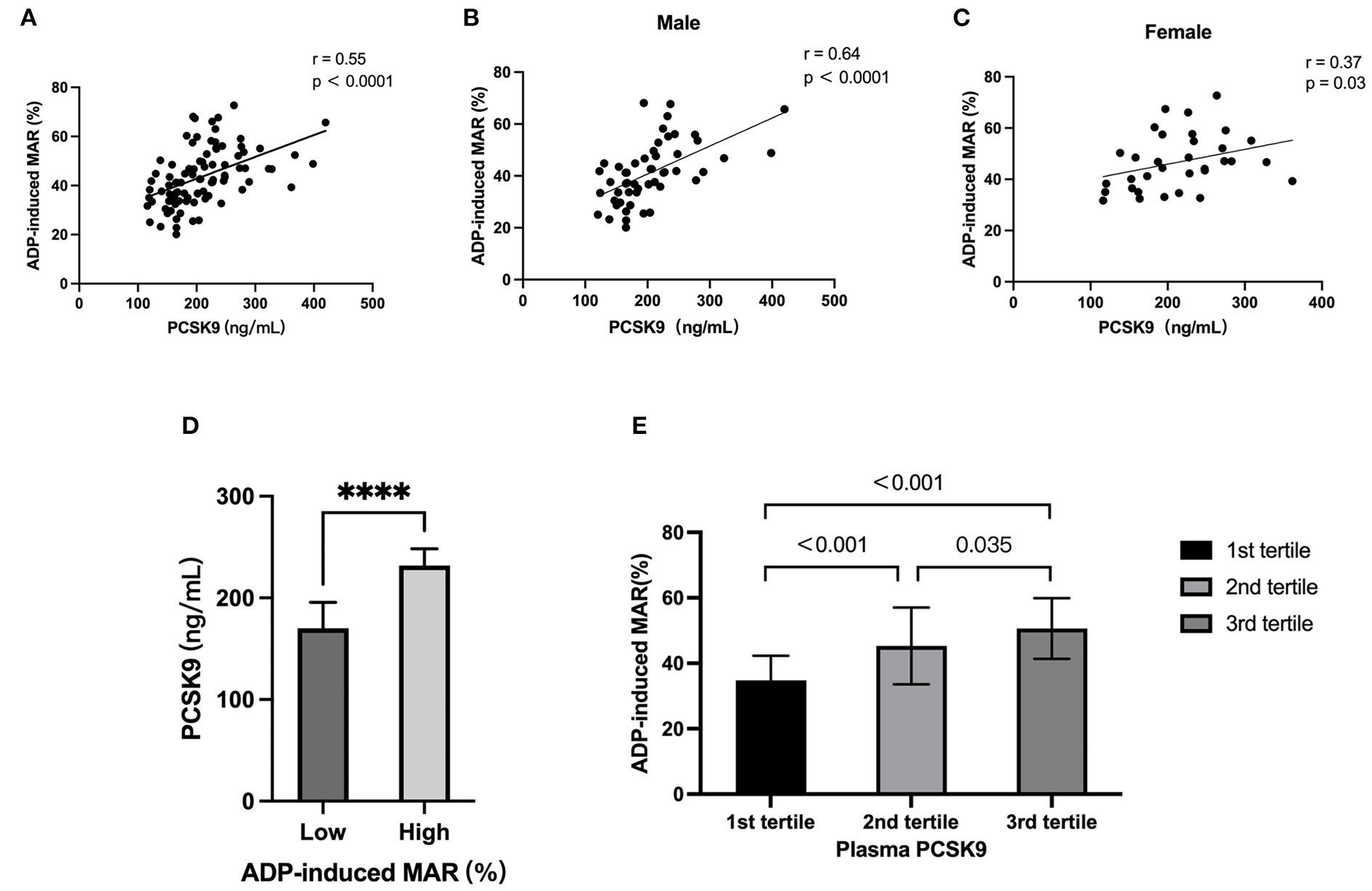

Independent association of PCSK9 with platelet reactivity in subjects without statin or antiplatelet agents

Shuai Wang, Di Fu, Huixing Liu and Daoquan Peng

August 2023 3 frontiersin.org Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

111 Correlation of cardiovascular risk predictors with overweight and obesity in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia

Yaodong Wang and Jinchun He

123 Bayesian network analysis of panomic biological big data identifies the importance of triglyceride-rich LDL in atherosclerosis development

Szilard Voros, Aruna T. Bansal, Michael R. Barnes, Jagat Narula, Pal Maurovich-Horvat, Gustavo Vazquez, Idean B. Marvasty, Bradley O. Brown, Isaac D. Voros, William Harris, Viktor Voros, Thomas Dayspring, David Neff, Alex Greenfield, Leon Furchtgott, Bruce Church, Karl Runge, Iya Khalil, Boris Hayete, Diego Lucero, Alan T. Remaley and Roger S. Newton

139 Oxidized low-density lipoprotein associates with cardiovascular disease by a vicious cycle of atherosclerosis and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Christin G. Hong, Elizabeth Florida, Haiou Li, Philip M. Parel, Nehal N. Mehta and Alexander V. Sorokin

150 Prognostic value of remnant cholesterol in patients with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Yun Tian, Wenli Wu, Li Qin, Xiuqiong Yu, Lin Cai, Han Wang and Zhen Zhang

160 Paraoxonase 1 and atherosclerosis

Paul N. Durrington, Bilal Bashir and Handrean Soran

August 2023 4 frontiersin.org Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

EDITEDANDREVIEWEDBY

ElenaOsto, MedicalUniversityofGraz,Austria

*CORRESPONDENCE

Chu-HuangChen cchen@texasheart.org AlexanderAkhmedov alexander.akhmedov@uzh.ch

RECEIVED 23June2023

ACCEPTED 14July2023

PUBLISHED 24July2023

CITATION

KralerS,SawamuraT,HarnGY-S,ChenC-H andAkhmedovA(2023)Editorial:Implications oflipidsandmodifiedlipoproteinsin atherogenesis:frommechanismstowardsnovel diagnosticandtherapeutictargets. Front.Cardiovasc.Med.10:1245716. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1245716

COPYRIGHT

©2023Kraler,Sawamura,Harn,Chenand Akhmedov.Thisisanopen-accessarticle distributedunderthetermsofthe Creative CommonsAttributionLicense(CCBY).Theuse, distributionorreproductioninotherforumsis permitted,providedtheoriginalauthor(s)and thecopyrightowner(s)arecreditedandthatthe originalpublicationinthisjournaliscited,in accordancewithacceptedacademicpractice. Nouse,distributionorreproductionis permittedwhichdoesnotcomplywiththese terms.

SimonKraler1,TatsuyaSawamura2,GraceYen-ShinHarn3, Chu-HuangChen3,4* andAlexanderAkhmedov1*

1CenterforMolecularCardiology,UniversityofZurich,Schlieren,Switzerland, 2DepartmentofMolecular Pathophysiology,ShinshuUniversitySchoolofMedicine,ShinshuUniversity,Matsumoto,Japan, 3HEART, HealthResourceTechnology,LLC,Houston,TX,UnitedStates, 4VascularandMedicalResearch,TheTexas HeartInstitute,Houston,TX,UnitedStates

KEYWORDS

low-densitylipoprotein,inflammation,biomarkers,riskstratification,residual cardiovascularrisks,high-densitylipoproteins,triglycerides

EditorialontheResearchTopic

Implicationsoflipidsandmodifiedlipoproteinsinatherogenesis:from mechanismstowardsnoveldiagnosticandtherapeutictargets

1.Introduction

Atherosclerosisistheleadingcauseofmorbidityandmortalityworldwide.Despitethe unprecedentedgainsoverthepastdecades,patientswithestablishedatherosclerotic cardiovasculardisease(ASCVD)remainathighriskofrecurrentischemiceventsdespite optimalmanagement(1–3).Deepeninginsightsintotheunderlyingmechanismsprovide uniqueopportunitiestorefinepreviousconceptsofatherosclerosispathobiologywiththe ultimategoaltoimproveitspreventionandtreatmentandeventuallypatientoutcomes (4).Theatherogenicityofapolipoprotein-Bcontaininglipoproteinsiswellestablished,but recentstudieshaveshednewlightontheimportanceoflipidqualityinthedevelopment ofatherosclerosisanditsclinicalcomplications(5, 6).

WiththisResearchTopic,wehaveassembledanissueofcompellingarticles,comprising originalresearch,casereports,editorials,andstate-of-the-artreviews,withtheaimtogivethe readersof FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine acomprehensiveoverviewoftheroleof modifiedlipoproteinsinthedifferentphasesofatherogenesis.Indeed,thisResearchTopic notonlydeepensourunderstandingoflipid-drivenmechanismsunderpinningASCVDbut alsoprovidesinsightsintonovelconceptstoaddressthehighburdenofASCVD.

2.Low-densitylipoproteins,high-density lipoproteins,andtriglycerides

Withtheaccumulationofevidenceonsex-specificdifferencesinatherosclerosis pathobiology,clinicaltoolstoguidesex-specificpatientcarearegainingincreasing

Editorial:Implicationsoflipidsand modifiedlipoproteinsin atherogenesis:frommechanisms towardsnoveldiagnosticand therapeutictargets

TYPE Editorial PUBLISHED 24July2023 | DOI 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1245716 Frontiersin CardiovascularMedicine 01 frontiersin.org 5

attentioninrecentyears(7).Thenarrativereviewarticleby Wang andHe highlightsspecificdifferencesinlipoproteinmetabolism andassociatedriskfactorsinwomenandmen.Forexample, womentendtohavehigherhigh-densitylipoproteincholesterol (HDL-C)levels,whichareobservationallylinkedtolower ASCVDrisk;however,atthesametime,womentendtohave highertriglyceridelevels,whichareassociatedwithhigher cardiovascularrisk.Furthermore,sexhormonesandreproductive factorsmayaffectlipoproteinmetabolismand,thus,theriskof majoradversecardiovascularevents(MACE).Gainingabetter understandingofsex-specificdifferencesmayopennovelavenues forclinicalinterventionsthatcouldimprovethepreventionand treatmentofASCVD.

Takingthisconceptastepfurther, Dietrichetal. have emphasizedtheimportanceofsexhormonesandsex-specificeffects ofHDLanditsinteractionwithendothelialcells.Inadditiontotheir immunomodulatory,anti-inflammatory,andanti-oxidative properties,HDLparticlesarethoughttoprovidevasculoprotective effectsbypromotingvasorelaxationandregulatingvascularlipid metabolism.Animprovedunderstandingofhowsex-specificfactors affecttheseinteractionsmaybeusefulindevelopingpersonalized approachesforpreventingandtreatingASCVD.

Inthereviewarticleby Tirandietal. thepotentialroleof physicalactivityinregulatingtheexpressionofproprotein convertasesubtilisin/kexintype9(PCSK9),akeyregulatorof LDL-Clevels,isdiscussed.Inarelatedstudy, Wangetal. investigatedpotentialassociationsbetweenPCSK9levelsand plateletreactivityinindividualsnotreceivingstatinor antiplatelettherapy.Theauthorsreportedasignificantpositive correlationbetweenPCSK9andplateletreactivity,suggestingthat inhibitingPCSK9mayattenuateplateletreactivityandthus MACEriskinpatientsathighASCVDrisk.Thisdiscovery encouragesfurtherresearchonthepleiotropiceffectsofPCSK9 inhibitionincaringforpatientswithestablishedASCVD.

Theretrospectivestudyby WangandHe assessedthe correlationbetweencardiometabolicriskfactorsandobesityin 103patientswithfamilialhypercholesterolemia.Their findings demonstratethepotentialofusingnovelbiomarkersforrisk stratificationandpersonalizedmanagementofmoderatetohighriskpatients,suchasthosewithfamilialhypercholesterolemia. Similarly,thestudyby Zengetal. emphasizestheimportanceof consideringnon-HDL-Casariskfactorinmennotreceiving statintherapy.TheauthorsdescribeaU-shapedrelationship betweennon-HDL-Clevelsandall-causeandcardiovascular mortality,suggestingthatbothlowandhighlevelsofnon-HDLCareassociatedwithincreasedmortalityrisk,a findingthatwas similarlyreportedforLDL-C(8).

Xuetal.’sstudyfocusedoncomparingestablishedformulas usedforcalculatingLDL-Clevelsinfastingandpostprandial statesintheChinesepopulation.Notably,theFriedewald formulaprovidedthehighestaccuracyfordeterminingfasting LDL-Clevels,whereastheSampsonformulaperformedbetterfor measuringpostprandialLDL-Clevels.These findingsmay stimulatefurtherresearchinthisdirectiontoaccuratelyassess cardiovascularriskandeventuallyrefineinterventionsinthe Chinesepopulation.

Inanimportantreviewonmacrophage-mediatedpinocytotic engulfmentoflipoproteins, Miyazaki highlightsareceptorindependentendocyticpathwayforfoamcellformation.This processappearstooccurwhenlipoproteinsaccumulatearound inflammatorycellsandinvolvesplasmamembraneruffling, small GTPases,andcytoskeletalrearrangement.AlthoughnativeLDL maynotbethemaindriveroffoamcellformation,further experimentalstudiesarenecessarytoidentifythemaster regulatoroflipoproteinengulfmentbymacrophagestoimprove ourunderstandingofitsroleinASCVDpathogenesis.

3.Qualityoflipoproteins

Oneareaofresearchthathasgainedincreasingattentioninrecent yearsistheroleofmodifiedlipoproteinsinthelifecycleof atheroscleroticplaque.Modifiedlipidsincludeoxidizedlow-density lipoprotein(oxLDL),small-denseLDL,triglyceride-richLDL, electronegativeLDL,andverylow-densitylipoprotein(VLDL)(5, 9–11).

Leeetal.’sreviewfocusesonVLDL,apotentialdriverof cardiometabolicdiseases.ThemostelectronegativeVLDL subclassexertscytotoxiceffectsontheendotheliumandhasbeen linkedtochroniccoronarysyndromesandatrialremodelingin patientswithmetabolicsyndrome.Thereviewarticlehighlights thesignificanceofpostprandialVLDLmodificationandtheneed forfurtherinvestigationintotheroleofVLDLsubclassesinthe pathobiologyofcardiometabolicdiseases.

InaBayesiannetworkanalysisfocusedonbiomarkersofcoronary atherosclerosis, Vorosetal. havehighlightedtheimportanceof triglyceride-richLDLparticlesinASCVDdevelopment.Inthe665 patientsincludedintheanalysis,LDL-triglyceridesweredirectly linkedtocarotidatherosclerosisinover95%ofthemodels. Interestingly,geneticvariantsintheLIPCgene(encodinghepatic lipase)wereassociatedwithLDL-triglyceridelevelsandthepresence ofatheroscleroticplaque.These findingssuggestthattriglyceriderichLDLparticlesmayplayacrucialroleinatherosclerosis development,thusprovidingapotentialtargetforfuturestudies.

InaChinesepopulation, Liuetal. exploredpotential associationsbetweenremnantcholesterol(RC)andnew-onset carotidplaques.TheauthorsconcludedthatelevatedRClevels arestronglyassociatedwiththepresenceofnew-onsetcarotid plaquesrelativetootherlipidparameters,particularlyinthose withlowLDL-Clevels.Thisstudyhighlightstheimportanceof consideringRCinpredictingresidualcardiovascularrisk,suchas inthosewithlowlevelsofLDL-C.Ameta-analysisby Tianetal. furtherevaluatedtheprognosticvalueofRCinpatientswith chroniccoronarysyndromes.Theyreportedanincreasingriskof MACEwithhigherRClevels,althoughnosignificantassociation withall-causemortalitywasidentified.

Thereviewarticleby Shenetal. providesinsightsintotheimpact ofdyslipidemiaoncoronarycollateralformationduringdiabetic states.Theauthorsnotethatbothalteredserumlipidprofilesand glycoxidativemodificationoflipoproteinscontributetoendothelial dysfunctionandbluntendothelialprogenitorcellresponsesand interferewiththegrowthandmaturationofcollateralvesselsin diabeticpatientswithchroniccoronarysyndromes.

Kraleretal. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1245716 Frontiersin CardiovascularMedicine 02 frontiersin.org 6

Theabovereviewarticleandtheaforementionedworkdemonstrate thesignificanceoflipidsinatherosclerosisanditsacuteandchronic clinicalsequelae(Miyazaki, Vorosetal.Shenetal.).Furtherresearch inthisareamayleadtoinnovativestrategiesforpreventingand treatingASCVDandultimatelyimprovingpatientoutcomes.

Hongetal. conductedasystematicreviewandmeta-analysisto evaluatetherelationshipbetweenoxLDLandcardiovascular diseaseinpatientswithchronicinflammatoryconditions.The analysisofthreeobservationalstudiescomprisingatotalof1,060 participantsshowedthatcirculatingoxLDLlevelsareincreased inparticipantswithASCVDduringchronicinflammatory conditions.Indeed,theirstudysuggeststhatoxLDLmaybea usefulbiomarkerforriskstratificationofpatientswith establishedcardiovasculardiseasedrivenbychronicinflammation.

Sincetheintroductionofthetraditionalriskfactorconceptin theFraminghamStudy(12),cholesterol-richlipoproteinshave beenextensivelyexamined,withinstrumentalvariableapproaches nowallowingforcausalinferenceusingobservationaldata.Inthe innovativestudyby Jinetal.,thecausalroleofcholesterolefflux capacityinchroniccoronarysyndromes,acutemyocardial infarction,andischemicstrokewasexaminedusingMendelian randomization.Consideringthepotentiallimitationsoftheir approach,these findingssuggestthatincreasedcholesterolefflux capacityreducestheriskofchroniccoronarysyndromesand myocardialinfarctionbuthasaweakercausaleffectonischemic stroke,likelybecauseofitsmoreheterogeneouspathobiology.

Collectively,thestudiesby Wangetal.Zengetal.Xuetal.Liu etal.Tianetal. and Jinetal. highlighttheimportanceof consideringmultiplefactorsinassessingcardiovascularriskwith

potentialfuturetherapeuticimplications.Inadditionto traditionalriskfactors,non-HDL-CandRCconcentrationsmay providevaluableinsightsintoapatient’soverallcardiovascularrisk.

Thesestudiesalsohighlighttheinterplayoflipoproteins,physical activity,sex-specificdeterminants,andemergingbiomarkersin cardiovascularhealthanddisease(WangandHe).Althoughthe traditionalriskfactorconcepthaslongprevailed,itmighthave resultedinanoversimplifiedunderstandingofASCVD.Animproved understandingofASCVDpathobiologyoffersuniqueopportunitiesto furtherimprovepatientcareandtomitigateresidualcardiovascularrisk.

Intheirreviewarticle, Durringtonetal. highlightacriticalrole ofHDL-containedserumparaoxonase-1(PON1)inprotecting againstharmfulLDLoxidation,amechanismthatdrivesearly phasesofASCVD.Accordingly,reducedserumPON1activityis associatedwithdyslipidemic,diabetic,andinflammatorystates. LowPON1levelsarefurtherlinkedtoadversecardiovascular events,particularlyinpatientswithdiabetesandestablished ASCVD,providingaconceptualframeworktostudyfunctional determinantsofHDLtoreduceresidualcardiovascularrisk.

Thearticlesby WangandHe, Dietrichetal., Tirandietal., Lee etal., Hongetal.,and Durrington et al. underscorethesignificance ofbiomarkersincardiovasculardiseasepreventionand personalizedpatientcare.Theidentificationofnovelbiomarkers canaidinpersonalizedriskassessmentandprovideabasisfor targetedinterventionsinhigh-riskpatients.Moreover,these studiessuggestthatnovelbiomarkers,includingoxLDL,PON1, andelectronegativeVLDL,mayserveascomplementarytoolsfor theidentificationofpatientsatparticularlyhighASCVDrisk whomaybenefitfromintensivesecondarypreventionmeasures.

Lipidsandtheirmodificationscontributeimportantlytothepathogenesisofatheroscleroticcardiovasculardisease(ASCVD).High-throughput technologies,includinglipidomics,nowallowthein-depthcharacterizationoflipoproteinstructureandfunction.Bothphysicalandchemical characteristicsmodulatetheatherogeniceffectsofbloodlipids,butgeneticsusceptibility,sexandgender,physicalactivity,andreceptor(in-) dependentmechanismscandeterminetheir(cardio-)vasculareffects.AbetterunderstandingofhowthesebiomarkerscontributetoASCVD pathogenesismayallowforpersonalizedriskassessmentandtheidentificationofnoveltherapeutictargets,aimedatreducingresidualcardiovascular riskandthusimprovingoutcomesofpatientsatparticularlyhighcardiovascularrisk.

FIGURE1

FIGURE1

Kraleretal. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1245716 Frontiersin CardiovascularMedicine 03 frontiersin.org 7

However,itisessentialtorecognizethatthesebiomarkersshould notbeusedinisolationbutshouldbeconsideredalongsideother clinicaltools,includingriskscores.Moreover,theclinicalutilityof novelbiomarkersforriskassessmentmustundergorigorous validationindifferentpopulationsandsettings,takingintoaccount potentiallimitationsinherentinthedesignofthestudiesnotedabove.

Together,thestudiespresentedinthisResearchTopichighlight theimportanceofbiomarkersinthepreventionandmanagement ofASCVDanditscomplications(Figure1).Theidentificationand rigorousvalidationofnovelbiomarkerscouldassistinpersonalized riskassessmenttoguidetargetedinterventionsinhigh-risk populations.Tothatend,high-throughputassaysareneededfor qualitativelyassessingchangesinthestructureandfunctionof lipoproteinstoworktowardtheclinicalimplementationof multidimensionallipidprofiling.Thehereinproposedresearch pursuitiscrucialfordevelopingeffectivepreventionand managementstrategiesforpatientsatriskfororwithestablished ASCVDwiththeultimategoalofreducingtheburdenof residualcardiovascularrisk.

Authorcontributions

Allauthorslistedhavemadeasubstantial,direct,andintellectual contributiontotheworkandapproveditforpublication.

References

1.KralerS,WenzlFA,LuscherTF.Repurposingcolchicinetocombatresidual cardiovascularrisk:theLoDoCo2trial. EurJClinInvest.(2020)50:e13424.doi:10. 1111/eci.13424

2.SabatineMS,GiuglianoRP,KeechAC,HonarpourN,WiviottSD,MurphySA, etal.Evolocumabandclinicaloutcomesinpatientswithcardiovasculardisease. NEnglJMed.(2017)376:1713–22.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615664

3.SchwartzGG,StegPG,SzarekM,BhattDL,BittnerVA,DiazR,etal.Alirocumab andcardiovascularoutcomesafteracutecoronarysyndrome. NEnglJMed.(2018) 379:2097–107.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801174

4.KralerS,LibbyP,EvansPC,AkhmedovA,SchmiadyMO,ReinehrM,etal. Resilienceoftheinternalmammaryarterytoatherogenesis:shiftingfromriskto resistancetoaddressunmetneeds. ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol.(2021) 41:2237–51.doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.316256

5.KralerS,WenzlFA,VykoukalJ,FahrmannJF,ShenM-Y,ChenD-Y,etal.Lowdensitylipoproteinelectronegativityandriskofdeathafteracutecoronarysyndromes: acase-cohortanalysis. Atherosclerosis.(2023)376:43–52.doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis. 2023.05.014

6.RuuthM,NguyenSD,VihervaaraT,HilvoM,LaajalaTD,KondadiPK,etal. Susceptibilityoflow-densitylipoproteinparticlestoaggregatedependsonparticle lipidome,ismodifiable,andassociateswithfuturecardiovasculardeaths. EurHeart J.(2018)39:2562

73.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy319

Acknowledgments

TheauthorsthankRebeccaBartow,ofTheTexasHeart InstituteinHouston,TX,foreditorialassistance.

Conflictofinterest

GHandCH-HwereemployedbyHEART,HealthResource Technology,LLC.

Theremainingauthorsdeclarethattheresearchwasconducted intheabsenceofanycommercialor financialrelationshipsthat couldbeconstruedasapotentialconflictofinterest.

ThehandlingeditorEOdeclaredapastcollaborationwiththe authorAA.

Publisher’snote

Allclaimsexpressedinthisarticlearesolelythoseofthe authorsanddonotnecessarilyrepresentthoseoftheiraffiliated organizations,orthoseofthepublisher,theeditorsandthe reviewers.Anyproductthatmaybeevaluatedinthisarticle,or claimthatmaybemadebyitsmanufacturer,isnotguaranteed orendorsedbythepublisher.

7.WenzlFA,KralerS,AmblerG,WestonC,HerzogSA,RaberL,etal.Sex-specific evaluationandredevelopmentoftheGRACEscoreinnon-ST-segmentelevationacute coronarysyndromesinpopulationsfromtheUKandSwitzerland:amultinational analysiswithexternalcohortvalidation. Lancet.(2022)400:744–56.doi:10.1016/ S0140-6736(22)01483-0

8.JohannesenCDL,LangstedA,MortensenMB,NordestgaardBG.Association betweenlowdensitylipoproteinandallcauseandcausespecificmortalityinDenmark: prospectivecohortstudy. BrMedJ.(2020)371:m4266.doi:10.1136/bmj.m4266

9.ChanHC,KeLY,ChuCS,LeeAS,ShenMY,CruzMA,etal.Highlyelectronegative LDLfrompatientswithST-elevationmyocardialinfarctiontriggersplateletactivation andaggregation. Blood.(2013)122:3632–41.doi:10.1182/blood-2013-05-504639

10.KralerS,WenzlFA,GeorgiopoulosG,ObeidS,LiberaleL,vonEckardsteinA, etal.Solublelectin-likeoxidizedlow-densitylipoproteinreceptor-1predicts prematuredeathinacutecoronarysyndromes. EurHeartJ.(2022)43:1849–60. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac143

11.ShenMY,ChenFY,HsuJF,FuRH,ChangCM,ChangCT,etal.PlasmaL5 levelsareelevatedinischemicstrokepatientsandenhanceplateletaggregation. Blood.(2016)127:1336–45.doi:10.1182/blood-2015-05-646117

12.KannelWB,DawberTR,KaganA,RevotskieN,StokesJ3rd.Factorsofriskin thedevelopmentofcoronaryheartdisease–sixyearfollow-upexperience.The framinghamstudy. AnnInternMed.(1961)55:33–50.doi:10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33

–

Kraleretal. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1245716 Frontiersin CardiovascularMedicine 04 frontiersin.org 8

Editedby: Chu-HuangChen, TexasHeartInstitute,UnitedStates

Reviewedby: C.M.Schooling, CityUniversityofNewYork, UnitedStates AdriaArboix, SacredHeartUniversity Hospital,Spain

*Correspondence: YuesongPan yuesongpan@ncrcnd.org.cn

†Theseauthorshavecontributed equallytothisworkandsharefirst authorship

Specialtysection: Thisarticlewassubmittedto LipidsinCardiovascularDisease, asectionofthejournal FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine

Received: 07March2022

Accepted: 14June2022

Published: 04July2022

Citation:

JinA,WangM,ChenW,YanH, XiangXandPanY(2022)Differential EffectsofGeneticallyDetermined CholesterolEffluxCapacityon CoronaryArteryDiseaseandIschemic Stroke. Front.Cardiovasc.Med.9:891148. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.891148

DifferentialEffectsofGenetically DeterminedCholesterolEfflux CapacityonCoronaryArteryDisease andIschemicStroke

Background: Observationalstudiesindicatedthatcholesteroleffluxcapacity(CEC) ofhigh-densitylipoprotein(HDL)isinverselyassociatedwithcardiovascularevents, independentlyoftheHDLcholesterolconcentration.Theaimofthestudyistoexamine thecasualrelevanceofCECforcoronaryarterydisease(CAD)andmyocardialinfarction (MI),andcompareitwiththatforischemicstrokeanditssubtypesusingaMendelian randomizationapproach.

Methods: Weperformeda2-sampleMendelianrandomizationtoestimatethecasual relationshipofCECwiththeriskofCAD,MI,andischemicstroke.ACEC-related geneticvariant(rs141622900)andotherfivegeneticvariantswereusedasthe instrumentalvariables.AssociationofgeneticvariantswithCADwereestimatedina GWASinvolving60,801CADcasesand123,504controls.Theywerethencompared withtheassociationsofthesevariantswithischemicstrokeanditssubtypes(large vessel,smallvessel,andcardioembolic)involving40,585ischemicstrokecasesand 406,111controls.

Results: UsingtheSNPofrs141622900astheinstrument,a1-SDincreaseinCEC wasassociatedwith45%lowerriskforCAD(oddsratio[OR]0.55,95%confidence interval[CI]0.44–0.69, p < 0.001)and33%lowerriskforMI(oddsratio[OR]0.67,95% CI0.52–0.87, p = 0.002).Bycontrast,thecausaleffectofCECwasmuchweakerfor ischemicstroke(oddsratio[OR]0.79,95%CI0.64–0.97, p = 0.02; p forheterogeneity = 0.03)and,inparticular,forcardioembolicstroke(p forheterogeneity = 0.006)when comparedwiththatforCAD.Resultsusingfivegeneticvariantsastheinstrumentalso indicatedconsistentlyweakereffectsonischemicstrokethanonCAD.

Conclusion: GeneticpredictedhigherCECmaybeassociatedwithdecreasedriskof CAD.However,thecasualassociationofCECwithischemicstrokeandspecificsubtypes wouldneedtobevalidatedinfurtherMendelianrandomizationstudies.

Keywords:cholesteroleffluxcapacity,Mendelianrandomization,coronaryarterydisease,stroke,genetics

ORIGINALRESEARCH published:04July 2022

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 1 July2022 | Volume9|Article891148

doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.891148

AomingJin 1,2†,MengxingWang 1,2†,WeiqiChen 1,2,HongyiYan 1,2,XianglongXiang 1,2 and YuesongPan 1,2*

1 DepartmentofNeurology,BeijingTiantanHospital,CapitalMedicalUniversity,Beijing,China, 2 ChinaNationalClinical ResearchCenterforNeurologicalDiseases,BeijingTiantanHospital,CapitalMedicalUniversity,Beijing,China

9

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiologicstudieshaveshownaninverserelationship betweenhigh-densitylipoprotein(HDL)cholesterollevelsand cardiovasculardisease(1);however,recentclinicaltrials(2, 3) andMendelianrandomization(MR) studies(4, 5)failedto established aclearcausalassociationbetweenHDLcholesterol andcardiovasculardisease.Thisledtothehypothesisthatthe atheroprotectiveroleofHDLliesinitsfunctionratherthanin itsconcentrations(6).

Themostimportant measureofHDLfunctionischolesterol effluxcapacity(CEC),theabilityofHDLtoreversecholesterol transportfromperipheralcells(7).PreviouscohortandcasecontrolstudiesshowedthatCECwasinverselyassociatedwith atherosclerosisandtheincidenceofcardiovasculareventsin thegeneralpopulation,independentlyoftheHDLcholesterol concentration(8–11).However,observationalepidemiological studiesmaysuffer fromconfoundingandselectionbiasthat representobstaclestovalidcausalinference(12, 13).Thecausal associationbetweenCEC andcardiovasculardiseasesisstill controversial.Furthermore,ischemicstrokehadaheterogeneous mechanismandmayhavedifferentcauseandriskfactorsfrom coronaryarterydisease(CAD)(14).PreviousMRstudieshave showedaweaker effectonischemicstrokethanonCADfor somelipidmetabolicfactors,suchaslow-densitylipoprotein cholesterolandproproteinconvertasesubtilisin/kexintype9 (PCSK9)variants(15, 16).Therefore,therelativeeffectsofCEC onCADandischemicstrokeneedsfurtherinvestigation.

MRstudy,usinggeneticvariantsasinstrumentalvariables, isamethodthatcancontrolpotentialconfoundersandreverse causationthatmaybiasobservationalstudies,andmakestronger causalinferencesbetweenanexposureandriskofdiseases(12). Inthepresentstudy,weaimedtouseMRanalysistoexaminethe causalrelevanceofCECforCADandmyocardialinfarction(MI), andcomparesitwiththatforischemicstrokeanditssubtypes.

MATERIALSANDMETHODS StudyDesign

Atwo-sampleMRanalysisusingCEC-relatedgeneticvariants asinstrumentalvariablewasdesignedtoevaluatethecausal effectbetweenCECandriskofCADandischemicstroke (SupplementaryFigure1).Summary-leveldataontheexposure (CEC)werederivedfromarecentpublishedgenome-wide associationstudy(GWAS)ofupto5,293Europeanindividuals (17)anddataontheoutcome(CADandischemicstroke) wereobtainedfrom GWASsofupto446,696European individuals(18, 19). Table1 and SupplementaryTable1 shows thecharacteristicsoftheseGWASs.Approvalofethicscommittee andwritteninformedconsentwereobtainedbeforedata collectionintheoriginalGWASs.

GeneticInstrumentalVariables

Weused6singlenucleotidepolymorphisms(SNPs)associated withCECidentifiedthroughGWASbyLow-Kametal.(17) asthe instrumentalvariables.Low-Kametal.(17)testedthe geneticassociation between4CECmeasuresandgenotypesat

>9millioncommonautosomalDNAsequencevariantsin5,293 FrenchCanadians.Theyidentified10genome-widesignificant signals(P < 6.25 × 10 9)representing7loci.Amongthe7loci, 2loci(nearthe PPP1CB/PLB1 and RBFOX3/ENPP7 genes)only reachedgenome-widesignificanceinthemodelfurtheradjusted forHDL-Candtriglyceridelevelswhichmayleadtofalsepositive associationsintheGWAScontext(i.e.,colliderbias).Other5 loci(CETP, LIPC, LPL, APOA1/C3/A4/A5,and APOE/C1/C2/C4) harboredgeneswithimportantrolesinlipidbiologyandreached genome-widesignificanceinthemodeladjustedforsex,age squared,coronaryarterydiseasestatus,experimentalbatches, statintreatment,andthefirst10principalcomponents.Except forthe APOE/C1/C2/C4 variant,associationofother4loci disappearedwhencorrectingforHDL-Candtriglyceridelevels. OnlytheSNPofrs141622900in APOE/C1/C2/C4 locusreached genome-widesignificanceinbothtwomodelsandwasusedasthe instrument.Insensitivityanalysis,weusedthemostsignificant SNPineachofthe5loci(rs77069344,rs2070895,rs247616, rs964184,andrs445925)astheinstrument.These5SNPswere indifferentgenomicregionsandnotinlinkagedisequilibrium (r2 < 0.1).The1SNP(rs141622900)instrumentexplained0.9% andthe5SNPsinstrumentexplained5.3%ofthevarianceinCEC (F statistic = 59.2and45.9,respectively,indicatingsufficient strengthoftheinstruments). Table2 showsthecharacteristics andassociationsoftheseincludedSNPswithCEC.

Outcomes

SummarystatisticsfortheassociationofeachCEC-relatedSNP withtheCADandMIwereextractedfromtheCoronaryARtery DIseaseGenome-wideReplicationAndMeta-AnalysisPlus CoronaryArteryDiseaseGenetics(CARDIoGRAMplusC4D) 1000Genomes-basedGWAS(17).TheCARDIoGRAMplusC4D 1000Genomes-basedGWASinterrogated9.4millionvariantsin upto60,801CADcasesand123,504controlsfrom48studies ofpredominantlyEuropeanancestry.Summarystatisticsfor theassociationoftheincludedSNPswithischemicstrokeand the3mainsubtypesofischemicstroke(largearterystroke [LAS],smallvesselstroke[SVS],cardioembolicstroke[CES]) wereextractedfromtheGWASofMultiancestryGenome-wide AssociationStudyofStroke(MEGASTROKE)consortium(19). TheMEGASTROKE consortiumtested ∼8millionSNPsand indelswithminor-allelefrequency ≥0.01inupto67,162stroke casesand454,450controlsfrom29studies,predominantly Europeanancestry(40,585cases;406,111controls).ThisGWAS involved34,217caseswithLAS,5,386caseswithSVSand7,193 caseswithCESofEuropeanancestry.Theassociationsofthe6 individualSNPsforCECwithCADandMI,andischemicstroke anditssubtypesarepresentedin Tables3, 4,respectively.

StatisticalAnalysis

Per-alleleeffectsoftheselectedSNPsonCECanddisease outcomeswereextractedfromtheGWASsandusedtoestimate thecausaleffectofCEConoutcomesusingtwo-sampleMR analyses.UsingtheSNPofrs141622900astheinstrument,Wald ratiomethodwereusedtoobtaineffectestimatebydividing theSNP-outcomeestimatebytheSNP-CECestimate.Standard errorwereestimatedusingtheDeltamethodbydividing

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 2 July2022| Volume9|Article891148 10

TABLE1| CharacteristicsoftheGWASstudiesusedinthisstudy.

TABLE2| Characteristicsoftheincluded SNPlociassociatedwithcholesteroleffluxcapacity.

theSNP-outcomestandarderrorbytheSNP-CECestimate (20).Whenusingthe5SNPsastheinstruments,weuseda conventionalinverse-variance weighted(IVW)MRanalysiswith multiplicativerandomeffectsassumingallgeneticvariantsare validinstruments.InIVWmethod,theSNP-outcomeestimate isregressedontheSNP-CECestimate,weightedbytheinversevarianceofSNP-outcomeestimateandwiththey-axisinterceptis fixedtozero(21).Wefurtherconductedmethodologicsensitivity analysesusingMR-Egger,simplemedian,weightedmedian methodsusingthe5SNPsastheinstruments,whicharemore robusttotheinclusionofpleiotropicorinvalidinstruments.MREggermethodcanassessandcontrolfordirectionalpleiotropic biasandprovideanpleiotropy-correctedeffectestimatein whichgeneticvariantsarepermittedtobeinvalidinstrumental variables(22).Themedianmethodscanprovideaconsistent effectestimate usingthemedianoftheempiricaldistribution functionofindividualSNPratioestimatesinwhichupto50%of thegeneticvariantsarepermittedtobeinvalidinstruments(23).

Presencesof heterogeneitybetweencausaleffectsofindividual variantsandcomparisonsbetweenthecausaleffectsofCECon CADvs.ischemicstrokeweretestedusingtheCochranQstatistic and I2 indexintheIVWanalysis(23).Evidenceofpleiotropic effectswereassessedusinginterceptsoftheMR-Eggerregression (22).Moreover,multivariabletwo-sampleMRwereperformed toadjustfor majorcausesofsurvival(smoking,bodymass index,andbloodpressure)usingthe5SNPsastheinstruments (24).MultivariableMRanalysiswasusedtoassesswhetherthe associationsbetweengenetic predispositiontoCECandischemic strokemaybeaffectedbyselectionbias(25).Theaboveanalysis

TABLE3| Geneticassociationofcholesteroleffluxcapacityrelatedgenetic variantswithcoronaryarterydiseaseandmyocardialinfarctioninthe CARDIoGRAMplusC4Dconsortium.

SNPsEA/OACoronaryarterydiseaseMyocardialinfarction

EA,effectallele;OA,otherallele;SE,standarderror;SNP,singlenucleotidepolymorphism. Theunitofbetacoefficientsislog-oddsperallele.Theoddsratio = exp(Beta),upper boundofoddsratio = exp(Beta+1.96 * SE),andlowerboundofoddsratio = exp(Beta1.96 * SE).

wereconductedintheUKBiobankGWASandFinnGenGWAS assensitivityanalyses.

ThepercentageofvarianceexplainedinCECwasestimated by2× (effectonCEC)2 × minorallelefrequency × (1-minor allelefrequency)(16).Apoweranalysiswasperformedusing aweb-based application(https://sb452.shinyapps.io/power/). EffectestimatesofCEC-outcome(CAD,MI,ischemicstrokeand itssubtypes)arepresentedasoddsratios(ORs)withtheir95% confidenceintervals(CIs)ofoutcomeper1-SDgeneticallyhigher CEC.Toaccountformultipletesting,aBonferroni-corrected significancelevelof p < 0.0083(i.e.,0.05/6for6outcomes)

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

Phenotype Consortium N EthnicityGenotypedata PMID Exposure Cholesterolefflux capacity(CEC) Upto5,293individualsEuropean GWASarray 30369316 Outcomes Coronaryarterydisease(CAD) CARDIoGRAMplusC4DUpto184,305individualsEuropean GWASarray 26343387 Myocardialinfarction(MI) CARDIoGRAMplusC4DUpto171,876individualsEuropean GWASarray 26343387 Ischemicstroke(IS) MEGASTROKE Upto446,696individualsEuropean GWASarray 29531354 Largearterystroke(LAS) MEGASTROKE Upto440,328individualsEuropean GWASarray 29531354 Smallvesselstroke(SVS) MEGASTROKE Upto411,497individualsEuropean GWASarray 29531354 Cardioembolicstroke(CES) MEGASTROKE Upto413,304individualsEuropean GWASarray 29531354

SNP LocusChromosome(Position)(hg19)EA/OAEAF CEC BetaSE p rs77069344 LPL 8(19821782) G/T 0.099J774basal0.20080.03277.96 × 10 10 rs2070895 LIPC 15(58723939) A/G0.230J774basal0.14240.02328.49 × 10 10 rs247616 CETP 16(56989590) T/C0.314J774basal0.14660.02114.08 × 10 12 rs964184 APOA1/C3/A4/A5 11(116648917) C/G0.857J774ABCA1dependent0.20190.02816.78 × 10 13 rs445925 APOE/C1/C2/C4 19(45415640) A/G0.114J774ABCA1dependent0.21550.03031.20 × 10 12 rs141622900 APOE/C1/C2/C4 19(45426792) A/G0.058BHKstimulated0.28330.04171.03 × 10 11

SNP,singlenucleotidepolymorphism;EA,effectallele;OA,otherallele;EAF,effectallelefrequency;CEC,cholesteroleffluxcapacity;SE,standarderror.Theunitofbetacoefficientsis SDincreaseofCECperallele.

BetaSE p BetaSE p rs77069344G/T 0.05140.0158 0.001 0.06510.01760.000 rs2070895A/G0.03720.01080.0010.04140.01210.001 rs247616T/C 0.03120.01030.002 0.02800.01140.014 rs964184C/G 0.05000.01240.000 0.04880.01390.000 rs445925A/G 0.08580.01870.000 0.06640.02140.002 rs141622900A/G 0.14210.02780.000 0.09630.03150.002

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 3 July2022| Volume9|Article891148 11

EA,effectallele;OA,otherallele;LAS,largearterystroke;SVS,small vesselstroke;CES,cardioembolicstroke;SE,standarderror;SNP,singlenucleotidepolymorphism.Theunitof betacoefficientsislog-oddsperallele.Theoddsratio = exp(Beta),upperboundofoddsratio = exp(Beta+1.96 * SE),andlowerboundofoddsratio = exp(Beta-1.96* SE).

waspredefinedasstatisticallysignificantevidenceforacausal association.AllanalyseswereconductedwithR3.5.1(R DevelopmentCoreTeam).

RESULTS

Geneticallydetermined1-SDincreaseinCECwascasually associatedwithasubstantialdecreaseinriskofCAD(OR = 0.55, 95%CI:0.44–0.69, p < 0.001)andMI(OR = 0.67,95%CI:0.52–0.87, p = 0.002);but,bycontrast,wasnotcausallyassociated withischemicstroke(OR = 0.79,95%CI:0.64–0.97, p = 0.02) oranyseparatesubtypeofischemicstroke(LAS:OR = 0.67, 95%CI:0.39–1.17, p = 0.16;SVS:OR = 1.08,95%CI:0.71–1.63, p = 0.73;CES:OR = 0.72,95%CI:0.44–1.17, p = 0.18)at theBonferroni-adjustedlevelofsignificance(p < 0.0083)using theSNPofrs141622900astheinstrument(Figure1).Theeffect ofCEConischemicstrokewasweakerthanthatonCAD(p forheterogeneity = 0.03, I2 = 80%),andinparticularonCES (p forheterogeneity = 0.006, I2 = 87%),whereastheeffectsof CEConLASandSVSwerecompatiblewiththemagnitudeof theeffectobservedforCAD(p forheterogeneity = 0.53and 0.34,respectively).TheeffectsofCEConischemicstrokeandits subtypeswerecompatiblewiththemagnitudeoftheeffectforMI (p forheterogeneity = 0.34,1.00,0.80,and0.06,respectively). Theseanalyseshada >99, >99,70,and82%powertodetect a30%decreaseinriskofischemicstroke,LAS,SVS,andCES (equivalenttotheupperlimitoftheCIforCAD),respectively; thiscanexcludeacausaleffectofCEConischemicstrokeand CESofthesamemagnitudeasonCAD,andindicatecomparable effectsofCEConLAS,SVS,andCAD.Whereas,thepowerto detecta13%decreaseinriskofischemicstroke,LAS,SVS,and CES(equivalenttotheupperlimitoftheCIforMI)was72,65,16, and20%,respectively;thisindicatedcomparativelylittlepower forcomparableeffectsofCEConischemicstroke,particular strokesubtypesandMI.

SimilardisparateassociationsofCECwereobservedwiththe riskofCAD(OR = 0.85,95%CI:0.79–0.90, p < 0.001)andMI (OR = 0.86,95%CI:0.80–0.92, p < 0.001),comparedtoischemic stroke(OR = 1.02,95%CI:0.95–1.09, p = 0.58)anditssubtypes (LAS:OR = 0.90,95%CI:0.76–1.07, p = 0.25;SVS:OR = 1.00, 95%CI:0.85–1.17, p = 0.95;CES:OR = 1.04,95%CI:0.91–1.19, p = 0.60),usingtheIVWmethodswiththe5-SNPsinstrument

(Figure1).TheeffectofCEConischemicstrokewasweakerthan thatonCAD(p forheterogeneity <0.001, I2 = 93%)andMI(p forheterogeneity <0.001, I2 = 91%),andinparticularonCES (p forheterogeneity = 0.008, I2 = 86%;pforheterogeneity = 0.01, I2 = 83%),whereastheeffectsofCEConLASandSVSwere compatiblewiththemagnitudeoftheeffectobservedforCAD (p forheterogeneity = 0.49and0.07,respectively)andMI(p for heterogeneity = 0.58and0.10,respectively).Theseanalyseshad a >99,99,42,and53%powertodetecta10%decreaseinrisk ofischemicstroke,LAS,SVS,andCES(equivalenttotheupper limitoftheCIforCADandMI),respectively;thiscanexcludea causaleffectofCEConischemicstrokeofthesamemagnitudeas onCADandMI,andindicatecomparableeffectsofCEConLAS, CAD,andMI.

SignificantassociationforCADandMIandinsignificant associationforischemicstrokeanditssubtypeswerealso observedinsensitivityanalysesusingtheMR-Egger,simple medianandweightedmedianmethodsusingthe5-SNPs instrument(Table5).Evidenceofheterogeneitywasobservedfor theoutcomeofCADandMI(Q = 42.5, p < 0.001; Q = 35.4, p < 0.001)butnotfortheoutcomeofischemicstrokeoritssubtypes (Q = 5.3, p = 0.26; Q = 6.6, p = 0.16; Q = 2.8, p = 0.59; Q = 2.0, p = 0.74)intheIVWanalysis.MR-Eggerregressionshowedno evidenceofdirectionalpleiotropyfortheassociationofCECwith alldiseaseoutcomes(all p valueforintercept >0.05)(Table5). InsensitivityanalysesusingFinnGenGWASdata,significant associationsforischemicheartdiseaseandMIandinsignificant associationforischemicstrokeandCESwereobservedusingthe SNPofrs141622900astheinstrument.However,nosignificant associationsfortheoutcomeswasobservedintheIVWanalysis usingthe5-SNPsinstrument(SupplementaryTable2).Inthe multivariableMRadjustingformajorcausesofsurvivalusingthe 5-SNPsinstrument,theassociationsofCECwithischemicstroke anditssubtypesremainedinsignificant,whichweresimilarto theestimatesbytheIVWmethod(SupplementaryTable3). Similarresultsofinsignificantassociationsforischemicstroke wereobservedintheUKBiobankdata(SupplementaryTable4).

DISCUSSION

Thepresentstudyisthefirstlarge-scaleassessmentand comparisonofcausalrelevanceofCECandtheriskofvascular

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

SNPs EA/OAIschemicstroke LAS SVS CES BetaSE p BetaSE p BetaSE P BetaSE p rs77069344G/T0.01530.01600.3390.04500.03960.2560.00620.03710.868 0.02070.03160.514 rs2070895A/G 0.00330.01210.783 0.05870.03040.0540.03670.02780.1870.01360.02350.563 rs247616T/C0.00820.01100.455 0.01680.02760.542 0.01190.02580.6450.01080.02120.609 rs964184C/G0.01810.01520.2330.00600.03730.872 0.00710.03490.8380.01220.02970.681 rs445925A/G 0.02980.01840.106 0.07230.04610.117 0.03650.04130.378 0.03620.03500.301 rs141622900A/G 0.05790.02540.023 0.09630.06790.156 0.07930.05980.1850.01780.05090.727

TABLE4| GeneticassociationofcholesteroleffluxcapacityrelatedgeneticvariantswithischemicstrokeanditssubtypesintheMEGASTROKEconsortium.

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 4 July2022| Volume9|Article891148 12

diseaseusingMendelianrandomizationapproach.Theresults showedthat geneticpredictedhigherCECmaybeassociated withdecreasedriskofCAD.However,thecasualassociationof CECwithischemicstrokeandspecificsubtypeswouldneedtobe validatedinfurtherMendelianrandomizationstudies.

OurfindingsofinverserelationshipbetweenCECandCAD andMIareconsistentwithseveralmeta-analysissummarizing previousobservationalstudies(10, 26, 27).Althoughresults fromthemajorityofstudieswereinlinewiththehypothesis thathigherCECisassociatedwithlowerriskofCAD(9, 11, 28–31),astudybyLishowedthatincreasedHDLmediatedCECwas paradoxicallyassociatedwithincreased riskforincidentmyocardialinfarctionorstroke,whichbased onthestudypopulationundergoingcoronaryangiography (32).Moreover,theGermanDiabetesDialysisStudy(4D Study)failedto observeansignificantassociationofCEC withthecompositeoutcome(cardiacdeath,nonfatalMI,and stroke)inpatientswithend-stagerenaldisease(33).The CECwasquantified usinghumanTHP-1-derivedmacrophage foamcellsloadedwithcholesterol,whichwasdifferent fromcAMP(cyclicadenosinemonophosphate)-stimulated murineJ774macrophagesemployedbyotherstudiesinthe generalpopulation(8, 11).Thereasonsfortheapparent discrepanciesamong previousstudiesintherelationship betweenCECandCADareunclearbutcouldbeascribedto differenceinsamplesize,studypopulation,studydesign,and

methodsforCECmeasurementsacrossstudies.Considering theheterogeneitybetweenobservationalstudiesandpotential confoundersthatwarrantcaution,MRstudiesusinggenetic variantsasinstrumentalvariablescouldprovidemorerobust evidenceforthecausalrelationshipofCECandthehealth outcomeofinterest.Thepresentstudyshowedgeneticpredicted higherCECwasassociatedwithlowerCADrisk,whichsupports thedirectcausalassociationbetweenCECandCAD.

OurstudydoesnotsupportacausalroleofCECinischemic stroke.Fewstudieshaveinvestigatedtheassociationbetween CECandischemicstrokeanditssubtypesexpecttwocohort studieswithinconsistentresults(9, 29).Resultsfromthe MESA(Multi-EthnicStudy ofAtherosclerosis)cohortshowed norelationshipofcholesterolmasseffluxcapacitywithstroke orwithnon-hemorrhagicstroke.However,asmallsubgroup(n = 37)oftheDallasHeartstudyreportedaninverseassociation betweenCECandstroke.UsinggeneticvariantsrelatedtoCEC astheinstrument,theassociationbetweenCECandischemic strokewasexamineddirectlyinourstudy.However,wefound noevidenceofsignificantcausalrelationshipsbetweenCEC andischemicstrokeanditssubtypes.InthepresentMendelian randomizationstudy,theestimatesofCECwithischemicstroke mightbebiasedbysampleselectiononsurvivingexposureof interestandonsurvivingcompetingriskoftheoutcome(24). However,theresultsofmultivariableMRanalysesconducted byadjustingforpotentialcausesofsurvivalwereconsistent

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

FIGURE1| Causaleffectestimatesofgeneticallypredictedcholesteroleffluxcapacityoncoronaryarterydiseaseandstroke.Estimatesrepresentedoddsratio(95% CI)perSDgeneticallyhighercholesteroleffluxcapacityderivedfromWaldratiomethodusingrs141622900astheinstrumentandinverse-varianceweightedmethod using5-SNPs(rs77069344,rs2070895,rs247616,rs964184,andrs445925)astheinstrument.CI,confidenceinterval;SNP,singlenucleotidepolymorphism;CAD, coronaryarterydisease;MI,myocardialinfarction;IS,ischemicstroke;LAS,largearterystroke;SVS,smallvesselstroke;CES,cardioembolicstroke.

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 5 July2022| Volume9|Article891148 13

nucleotidepolymorphism;CAD,coronaryarterydisease;MI,myocardialinfarction;IS,ischemicstroke; LAS,largearterystroke;SVS,smallvesselstroke;CES,cardioembolicstroke.

withthemainresults.Aswithanyselectionbiascorrectionby multivariableadjustment,itmaynotbefeasibletorecoverthe validestimate.WerepeatedtheanalysesintheUKBiobank dataandFinnGendata,respectively.Bothresultsweresimilar tothemainresultsinthepresentstudy.LargerscaleMendelian randomizationstudiesarestillneededtoclarifythegenetic effectsofCEConischemicstrokeandassessanyheterogeneity betweenischemicstrokesubtypes,whichmayshedlightonthe relationshipofCEConischemicstrokefurther.Furthermore, inthesefuturestudies,theeffectsofgeneticallydetermined CEConischemicstrokecouldbecomparedbetweenpatients withvascularcognitiveimpairmentvs.patientswithnoncognitiveimpairment.

TheHDL-mediatedCECistheabilitytoremoveexcess cholesterolfromlipid-ladenmacrophagesrepresentingthefirst crucialstepwithintheprocessofreversecholesteroltransport (7).Reversecholesteroltransportplaysanimportantrole inatheroprotective mechanismbyfacilitatingtheremovalof cholesterolinthearterialwallandthesubsequentdecreasein theproinflammatoryresponse(34, 35).Ourstudyfoundthatthe effectofCEC wasweakeronischemicstrokethanCAD,which wereconsistentlyobservedinsuchcomparisonsintheeffects ofotherbloodlipidonvasculardiseaseinrecentMendelian studies.AMendelianstudysuggestedthattheeffectsofLDL cholesterolonischemicstrokewasweakerthanthatoncoronary heartdisease(16).Moreover,anotherMendelianstudyshowed PCSK9geneticvariants hadsmallerassociationswithriskof ischemicstrokethanwithriskofcoronaryheartdisease(15).

Thepotentialexplanation forthedifferencebetweentheeffects ofCEConCADandischemicstrokeisthebiologicaldifferences inthesediseaseprocess.Ischemicstrokeinvolvesphenotypic heterogeneity,withdifferentbiologicalpathwaysforLAS,SVS, andCES,comparedtothemorehomogenousCADphenotype (36).Moreover,areviewreportedthathematologicaldisorders werethemost frequentetiologyofcerebralinfarctsofunusual cause(37).Exceptfortheusualcerebrovascularriskfactors suchas hypertension,diabetesmellitus,anddyslipidemia,other newlyfactorscouldbeconsideredofthecausalrelevancefor ischemicstroke.Furthermore,differencesinthedistribution ofriskfactorsaswellaspatientcharacteristicsbetween CARDIoGRAMPlusC4DandMETASTROKEconsortiummay partlyexplainthedifferenteffectsforCADandISobservedin

thestudy.Additionally,insufficientstatisticalpowerduetosmall samplesize,especiallyforstrokesubtypes,maybeconsidered asanotherreason.Anacetrapib,anCETP(cholesterylester transferprotein)inhibitorthatwasdevelopedforincreasing HDLcholesterollevelsandpromotingCECtoagreaterdegree, wasshownasignificantreductioninCADintheREVEAL trial(38).Althoughitmetitsprimaryendpoint,thesmall improvementagainst themaingoalandthesafetyofCETP inhibitorhadbecomeapointofcontentionconsistently.Finally, AnacetrapibwasnotfiledforapprovalwiththeUSFoodand DrugAdministration.Ourstudyprovidedsupportingevidence forthecausalrelationshipbetweenCECandriskofCAD, indicatingpotentialinterventiontargetstotheincreaseofCEC forimprovingcardiovascularoutcomes.

ThepresentMendelianrandomizationanalysesreliesonthree underlyingassumptions.First,weidentified6CEC-relatedSNPs (P < 6.25 × 10 9)servedasinstrumentsintheMRanalysis thatsatisfiedthefirstassumption.Second,wedidnotfindthat the5-SNPsinthestudywereassociatedwithotherkeylipids includinglow-densitylipoprotein,triglycerides,totalcholesterol, andapolipoproteinBbasedonGWASdatasets.Andtheresultsof multivariableMRanalysesandsensitivityanalysesusingtheUK BiobankdataandFinnGendatawereconsistentwiththemain results.Thus,theseresultsincreaseconfidenceinthevalidityof thesecondassumptionthatthereisnoconfounding(measured orunmeasured)ofthegeneticvariantswiththeoutcome.Third, allthegeneticvariantswerenotdirectlyassociatedwiththe outcomes(all P > 5 × 10 8),whichsuggestedthatthethird assumptionwasnotviolated.

Ourstudyhasseverallimitations.First,thestudywas conductedbasedondatasetsofpredominantlyEuropean ancestryandgeneralizationoftheresultstootherpopulations ofnon-Europeanancestrywaslimited.However,theuniformity oftheincludedsubjectsmayminimizetheriskofbiasby populationadmixture.Second,thesamplesizesofischemic strokesubtypeswerestillrelativelysmall,specificallyforSVS andCES.InsignificantassociationbetweenCECandischemic strokesubtypescouldbeattributedtoinsufficientstatistical power.However,mostestimateswereconsistentusingdifferent MRapproaches,whichsuggeststhattheobservedassociations arenotbychance.Third,althoughtheGWASthatweused toidentifyallCEC-relatedSNPsrepresentsthefirstandlargest

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

Outcome MR-Egger Simplemedian Weightedmedian OR(95%CI) P Intercept (95%CI) p valueforinterceptOR(95%CI) P OR(95%CI) p CAD(60,801/123,504)0.35(0.14–0.89)0.030.156( 0.007,0.319) 0.06 0.78(0.71–0.86) <0.0010.79(0.71–0.87) <0.001 MI(43,677/128,199)0.34(0.13–0.89)0.030.161( 0.004,0.326) 0.056 0.79(0.70–0.88) <0.0010.79(0.71–0.88) <0.001 IS(40,585/406,111)0.97(0.57–1.65)0.920.008( 0.083,0.100) 0.86 1.06(0.96–1.17)0.261.06(0.97–1.16)0.21 LAS(34,217/406,111)1.60(0.43–6.00)0.49 0.101( 0.330,0.128) 0.39 0.89(0.69–1.16)0.390.92(0.72–1.17)0.49 SVS(5,386/406,111)0.66(0.26–1.64)0.370.074( 0.086,0.233) 0.37 0.97(0.78–1.19)0.740.96(0.78–1.19)0.72 CES(7,193/406,111)0.79(0.36–1.71)0.550.048( 0.086,0.182) 0.48 1.08(0.90–1.28)0.411.08(0.91–1.28)0.41 MR,mendelianrandomization;OR,oddsratio;CI,confidenceinterval;SNP,single

*FiveSNPsintheinstrumentincludedrs77069344,rs2070895,rs247616,rs964184,andrs445925.

TABLE5| MRstatisticalsensitivityanalyses using5SNPsastheinstrumentalvariables*

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 6 July2022| Volume9|Article891148 14

efforttoidentifygenome-widesignificantlociassociatedwith CEC,samplesize remainsmodest(N = 5,293participants), andthereforethereisalimitationofpowertofindweakeffect variants.Inthemainanalysis,onlyoneSNP(rs141622900)was usedastheinstrument.TheSNPisstronglyassociatedwith manykeylipidsrelevanttocardiovasculardisease,suchaslowdensitylipoproteinandapolipoproteinB.Thepleiotropiceffects oftheCEC-relatedSNPsonotherkeylipidswasunabletobe assessedbytwo-samplemultivariableMRinthepresentstudy becauseofthelackofdata.However,wehaveconductedMREggerregressionusing5CEC-relatedSNPsastheinstrumental variablestoassessevidenceofpleiotropiceffectsinthestudy. Thoughtheresultsshowednoevidenceofdirectionalpleiotropy, furtherstudiesareneededtovalidatetheassociationsofCEC withdiseaseoutcomes.Forth,weperformedmultivariableMR andsensitivityanalysestocorrectselectionbias.However, recoveringthevalidestimatesofCECforischemicstrokehas notbeenfullyaddressed.Finally,Mendelianrandomizationhas beenconsideredasanalternativeapproachforcausalinferences withalotofadvantagescomparedtorandomizedcontrolled trials.However,itcannotreplacerandomizedcontrolledtrials inestablishingaclaimofcausality(39).Futureclinicaltrialsare stillneededwith sufficientstatisticalpowertovalidatethecausal relationshipofCEC.

ThestudyexaminedcausalrelationshipsbetweenCECand riskofvasculardiseaseusingMRanalysis,andsuggeststhat geneticpredictedhigherCECmaybeassociatedwithdecreased riskofCAD.However,thecasualassociationofCECwith ischemicstrokeandspecificsubtypeswouldneedtobevalidated infurtherMendelianrandomizationstudies.

DATAAVAILABILITYSTATEMENT

Theoriginalcontributionspresentedinthestudyareincluded inthearticle/SupplementaryMaterial,furtherinquiriescanbe directedtothecorrespondingauthors.

ETHICSSTATEMENT

Ethicalreviewandapprovalwasnotrequiredforthestudy onhumanparticipantsinaccordancewiththelocallegislation andinstitutionalrequirements.Writteninformedconsentfor

REFERENCES

1.HuxleyRR,BarziF,LamTH,CzernichowS,FangX,WelbornT,etal. Isolatedlowlevelsofhigh-densitylipoproteincholesterolareassociatedwith anincreasedriskofcoronaryheartdisease:anindividualparticipantdata meta-analysisof23studiesintheAsia-Pacificregion. Circulation. (2011) 124:2056–64.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028373

2.KeeneD,PriceC,Shun-ShinMJ,FrancisDP.Effectoncardiovascularriskof highdensitylipoproteintargeteddrugtreatmentsniacin,fibrates,andCETP inhibitors:meta-analysisofrandomisedcontrolledtrialsincluding117,411 patients. BMJ. (2014)349:g4379.doi:10.1136/bmj.g4379

3.BoekholdtSM,ArsenaultBJ,HovinghGK,MoraS,Pedersen TR,LarosaJC,etal.LevelsandchangesofHDLcholesteroland

participationwasnotrequiredforthisstudyinaccordancewith thenationallegislationandtheinstitutionalrequirements.

AUTHORCONTRIBUTIONS

AJandMWperformedthestudy,analyzedthedata,wrotethe paper,andrevieweddraftsofthepaper.WCandXXwrotethe paperandrevieweddraftsofthepaper.HYanalyzedthedata, preparedfiguresandtables,andrevieweddraftsofthepaper. YPconceivedanddesignedthestudy,performedthestudy, analyzedthedata,wrotethepaper,andrevieweddraftsofthe paper.Allauthorscontributedtothearticleandapprovedthe submittedversion.

FUNDING

ThisworkwassupportedbygrantsfromtheNationalNatural ScienceFoundationofChina(81971091and81901177), BeijingHospitalsAuthorityYouthProgramme(QML20190501 andQML20200501),YoungEliteScientistSponsorship ProgramfromChinaAssociationforScienceandTechnology (2019QNRC001),BeijingTiantanHospital,CapitalMedical University(2018-YQN-1and2020MP01)andOutstanding YoungTalentsProjectofCapitalMedicalUniversity(A2105).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dataoncholesteroleffluxcapacitywerederivedfromthe GWASperformedbyLow-Kametal.Dataoncoronary arterydisease/myocardialinfarctionhavebeencontributed byCARDIoGRAMplusC4Dinvestigatorsandobtainedfrom www.CARDIOGRAMPLUSC4D.ORG.Dataonstrokehave beencontributedbyMEGASTROKEinvestigatorsandobtained fromhttp://megastroke.org.TheMEGASTROKEproject receivedfundingfromsourcesspecifiedathttp://megastroke. org/acknowledgements.html.

SUPPLEMENTARYMATERIAL

TheSupplementaryMaterialforthisarticlecanbefound onlineat:https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm. 2022.891148/full#supplementary-material

apolipoproteinA-Iinrelationtoriskofcardiovascularevents amongstatin-treatedpatients:ameta-analysis. Circulation. (2013) 128:1504–12.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002670

4.VoightBF,PelosoGM,Orho-MelanderM,Frikke-SchmidtR,Barbalic M,JensenMK,etal.PlasmaHDLcholesterolandriskofmyocardial infarction:amendelianrandomisationstudy. Lancet. (2012)380:572–80.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2

5.HolmesMV,AsselbergsFW,PalmerTM,DrenosF,LanktreeMB,NelsonCP, etal.Mendelianrandomizationofbloodlipidsforcoronaryheartdisease. Eur HeartJ. (2015)36:539–50.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht571

6.AnastasiusM,KockxM,JessupW,SullivanD,RyeKA,KritharidesL. Cholesteroleffluxcapacity:anintroductionforclinicians. AmHeartJ. (2016) 180:54–63.doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2016.07.005

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 7 July2022 | Volume9|Article891148 15

7.RosensonRS,BrewerHBJr,DavidsonWS,FayadZA,FusterV, GoldsteinJ,etal.Cholesteroleffluxandatheroprotection:advancingthe conceptofreversecholesteroltransport. Circulation. (2012)125:1905–19.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066589

8.KheraAV,CuchelM,delaLlera-MoyaM,RodriguesA,Burke MF,JafriK,etal.Cholesteroleffluxcapacity,high-density lipoproteinfunction,andatherosclerosis. NEnglJMed. (2011) 364:127–35.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001689

9.RohatgiA,KheraA,BerryJD,GivensEG,AyersCR,WedinKE,etal.HDL cholesteroleffluxcapacityandincidentcardiovascularevents. NEnglJMed. (2014)371:2383–93.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409065

10.YeH,XuG,RenL,PengJ.Cholesteroleffluxcapacityin coronaryarterydisease:ameta-analysis. CoronArteryDis. (2020) 31:642–9.doi:10.1097/MCA.0000000000000886

11.SaleheenD,ScottR,JavadS,ZhaoW,RodriguesA,PicataggiA,etal. AssociationofHDLcholesteroleffluxcapacitywithincidentcoronaryheart diseaseevents:aprospectivecase-controlstudy. LancetDiabetesEndocrinol. (2015)3:507–13.doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00126-6

12.LawlorDA,HarbordRM,SterneJA,TimpsonN,DaveySmithG.Mendelian randomization:usinggenesasinstrumentsformakingcausalinferencesin epidemiology. StatMed. (2008)27:1133–63.doi:10.1002/sim.3034

13.BareinboimE,PearlJ.Causalinferenceandthedata-fusionproblem. Proc NatlAcadSciUSA. (2016)113:7345–52.doi:10.1073/pnas.1510507113

14.BoehmeAK,EsenwaC,ElkindMS.Strokeriskfactors, genetics,andprevention. CircRes. (2017)120:472–95.doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308398

15.HopewellJC,MalikR,Valdés-MárquezE,WorrallBB,CollinsR; METASTROKECollaborationoftheISGC.DifferentialeffectsofPCSK9 variantsonriskofcoronarydiseaseandischaemicstroke. EurHeartJ. (2018) 39:354–9.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx373

16.Valdes-MarquezE,ParishS,ClarkeR,StariT,WorrallBB;METASTROKE ConsortiumoftheISGC,etal.RelativeeffectsofLDL-Conischemicstroke andcoronarydisease:aMendelianrandomizationstudy. Neurology. (2019) 92:e1176–87.doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007091

17.Low-KamC,RhaindsD,LoKS,BarhdadiA,BouléM,AlemS,etal. VariantsattheAPOE/C1/C2/C4locusmodulatecholesteroleffluxcapacity independentlyofhigh-densitylipoproteincholesterol. JAmHeartAssoc. (2018)7:e009545.doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.009545

18.NikpayM,GoelA,WonHH,HallLM,WillenborgC,KanoniS,etal.A comprehensive1,000Genomes-basedgenome-wideassociationmeta-analysis ofcoronaryarterydisease. NatGenet. (2015)47:1121–30.doi:10.1038/ng.3396

19.MalikR,ChauhanG,TraylorM,SargurupremrajM,OkadaY,MishraA,et al.Multiancestrygenome-wideassociationstudyof520,000subjectsidentifies 32lociassociatedwithstrokeandstrokesubtypes. NatGenet. (2018)50:524–37.doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0058-3

20.ThomasDC,LawlorDA,ThompsonJR.Re:estimationofbiasinnongenetic observationalstudiesusing“Mendeliantriangulation”byBautistaetal. Ann Epidemiol. (2007)17:511–3.doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.12.005

21.BurgessS,ButterworthA,ThompsonSG.Mendelianrandomizationanalysis withmultiplegeneticvariantsusingsummarizeddata. GenetEpidemiol. (2013)37:658–65.doi:10.1002/gepi.21758

22.BowdenJ,DaveySmithG,BurgessS.Mendelianrandomizationwithinvalid instruments:effectestimationandbiasdetectionthroughEggerregression. IntJEpidemiol. (2015)44:512–25.doi:10.1093/ije/dyv080

23.BowdenJ,DaveySmithG,HaycockPC,BurgessS.Consistent estimationinmendelianrandomizationwithsomeinvalidinstruments usingaweightedmedianestimator. GenetEpidemiol. (2016) 40:304–14.doi:10.1002/gepi.21965

24.SchoolingCM,LopezPM,YangZ,ZhaoJV,AuYeungSL,Huang JV.Useofmultivariablemendelianrandomizationtoaddressbiases duetocompetingriskbeforerecruitment. FrontGenet. (2020) 11:610852.doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.610852

25.SmitRAJ,TrompetS,DekkersOM,JukemaJW,leCessieS.Survivalbiasin mendelianrandomizationstudies:athreattocausalinference. Epidemiology. (2019)30:813–6.doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000001072

26.QiuC,ZhaoX,ZhouQ,ZhangZ.High-densitylipoproteincholesterol effluxcapacityisinverselyassociatedwithcardiovascularrisk:

asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis. LipidsHealthDis. (2017) 16:212.doi:10.1186/s12944-017-0604-5

27.Soria-FloridoMT,SchroderH,GrauM,FitoM,LassaleC.High densitylipoproteinfunctionalityandcardiovasculareventsandmortality: asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2020)302:36–42.doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.04.015

28.Soria-FloridoMT,CastanerO,LassaleC,EstruchR,Salas-SalvadoJ,MartinezGonzalezMA,etal.Dysfunctionalhigh-densitylipoproteinsareassociated withagreaterincidenceofacutecoronarysyndromeinapopulationat highcardiovascularrisk:anestedcase-controlstudy. Circulation. (2020) 141:444–53.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041658

29.SheaS,SteinJH,JorgensenNW,McClellandRL,TascauL,ShragerS,et al.Cholesterolmasseffluxcapacity,incidentcardiovasculardisease,and progressionofcarotidplaque. ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol. (2019)39:89–96.doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311366

30.EbtehajS,GruppenEG,BakkerSJL,DullaartRPF,TietgeUJF.HDL(HighDensityLipoprotein)cholesteroleffluxcapacityisassociatedwithincident cardiovasculardiseaseinthegeneralpopulation. ArteriosclerThrombVasc Biol. (2019)39:1874–83.doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312645

31.ZhangJ,XuJ,WangJ,WuC,XuY,WangY,etal.Prognosticusefulnessof serumcholesteroleffluxcapacityinpatientswithcoronaryarterydisease. Am JCardiol. (2016)117:508–14.doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.11.033

32.LiXM,TangWH,MosiorMK,HuangY,WuY,MatterW,etal. Paradoxicalassociationofenhancedcholesteroleffluxwithincreased incidentcardiovascularrisks. ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol. (2013)33:1696–705.doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301373

33.KopeckyC,EbtehajS,GenserB,DrechslerC,KraneV,AntlangerM,etal. HDLcholesteroleffluxdoesnotpredictcardiovascularriskinhemodialysis patients. JAmSocNephrol. (2017)28:769–75.doi:10.1681/ASN.2016030262

34.Vallejo-VazAJ,RayKK.Cholesteroleffluxcapacityasanovel biomarkerforincidentcardiovascularevents:hashigh-density lipoproteinbeenresuscitated? CircRes. (2015)116:1646–8.doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305938

35.FeigJE,HewingB,SmithJD,HazenSL,FisherEA.High-densitylipoprotein andatherosclerosisregression:evidencefrompreclinicalandclinicalstudies. CircRes. (2014)114:205–13.doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300760

36.MendelsonSJ,PrabhakaranS.Diagnosisandmanagementoftransient ischemicattackandacuteischemicstroke:areview. JAMA. (2021)325:1088–98.doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26867

37.ArboixA,JiménezC,MassonsJ,ParraO,BessesC.Hematologicaldisorders: acommonlyunrecognizedcauseofacutestroke. ExpertRevHematol. (2016) 9:891–901.doi:10.1080/17474086.2016.1208555

38.BowmanL,HopewellJC,ChenF,WallendszusK,StevensW,CollinsR,etal. Effectsofanacetrapibinpatientswithatheroscleroticvasculardisease. NEngl JMed. (2017)377:1217–27.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1706444

39.PlotnikovD,GuggenheimJA.Mendelianrandomisationandthegoal ofinferringcausationfromobservationalstudiesinthevisionsciences. OphthalmicPhysiolOpt.(2019)39:11–25.doi:10.1111/opo.12596

ConflictofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarethattheresearchwasconductedinthe absenceofanycommercialorfinancialrelationshipsthatcouldbeconstruedasa potentialconflictofinterest.

Publisher’sNote: Allclaimsexpressedinthisarticlearesolelythoseoftheauthors anddonotnecessarilyrepresentthoseoftheiraffiliatedorganizations,orthoseof thepublisher,theeditorsandthereviewers.Anyproductthatmaybeevaluatedin thisarticle,orclaimthatmaybemadebyitsmanufacturer,isnotguaranteedor endorsedbythepublisher.

Copyright©2022Jin,Wang,Chen,Yan,XiangandPan.Thisisanopen-access articledistributedunderthetermsoftheCreativeCommonsAttributionLicense(CC BY).Theuse,distributionorreproductioninotherforumsispermitted,provided theoriginalauthor(s)andthecopyrightowner(s)arecreditedandthattheoriginal publicationinthisjournaliscited,inaccordancewithacceptedacademicpractice. Nouse,distributionorreproductionispermittedwhichdoesnotcomplywiththese terms.

Jinetal. CholesterolEffluxCapacityandVascularDiseases

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 8 July2022| Volume9|Article891148 16

Editedby: AlexanderAkhmedov, UniversityofZurich,Switzerland

Reviewedby: YangPeng, TheUniversityof Queensland,Australia DongfengZhang, QingdaoUniversity,China

*Correspondence: Min-ZhouZhang minzhouzhang@gzucm.edu.cn

Specialtysection:

Thisarticlewassubmittedto LipidsinCardiovascularDisease, asectionofthejournal FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine

Received: 24March2022

Accepted: 06June2022

Published: 07July2022

Citation:

ZengR-X,XuJ-P,KongY-J,TanJ-W, GuoL-HandZhangM-Z(2022)

U-ShapedRelationshipofNon-HDL CholesterolWithAll-Causeand CardiovascularMortalityinMen WithoutStatinTherapy. Front.Cardiovasc.Med.9:903481. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.903481

U-ShapedRelationshipofNon-HDL CholesterolWithAll-Causeand CardiovascularMortalityinMen WithoutStatinTherapy

Rui-XiangZeng 1,2,Jun-PengXu 1,2,Yong-JieKong 1,2,Jia-WeiTan 1,2,Li-HengGuo 1,2 and Min-ZhouZhang 1,2*

1 TheSecondClinicalCollegeofGuangzhouUniversityofChineseMedicine,Guangzhou,China, 2 DepartmentofCriticalCare Medicine,GuangdongProvincialHospitalofChineseMedicine,Guangzhou,China

Background: Non-HDL-Ciswellestablishedcausalriskfactorfortheprogressionof atheroscleroticcardiovasculardisease.However,thereremainsacontroversialpatternof hownon-HDL-Crelatestoall-causeandcardiovascularmortality,andtheconcentration ofnon-HDL-Cwheretheriskofmortalityislowestisnotdefined.

Methods: Apopulation-basedcohortstudyusingdatafromtheNationalHealthand NutritionExaminationSurvey(NHANES)from1999to2014.Maleparticipantswithout statintherapyweredividedintothesixgroupsaccordingtonon-HDL-Clevels(<100, 100–129,130–159,160–189,190–219, ≥220mg/dl).MultivariableCoxproportional hazardsmodelswereconductedwithahazardratio(HR)andcorresponding95% confidenceinterval(CI).Tofurtherexploretherelationshipbetweennon-HDL-Cand mortality,Kaplan–Meiersurvivalcurves,restrictedcubicsplinecurves,andsubgroup analysiswereperformed.

Results: Among12,574individuals(averageage44.29 ± 16.37years),1,174(9.34%) deathsduringamedianfollow-up98.38months.Bothlowandhighnon-HDL-Clevels weresignificantlyassociatedwithincreasedriskofall-causeandcardiovascularmortality, indicatingaU-shapedassociation.Thresholdvaluesweredetectedat144mg/dlforallcausemortalityand142mg/dlforcardiovascularmortality.Belowthethreshold,per 30mg/dlincreaseinnon-HDL-Creduceda28and40%increasedriskofall-cause (p < 0.0001)andcardiovascularmortality(p = 0.0037),respectively.Inversely,above thethreshold,per30mg/dlincreaseinnon-HDL-Cacceleratedriskofbothall-cause mortality(HR1.11,95%CI1.03–1.20, p = 0.0057)andcardiovascularmortality(HR 1.30,95%CI1.09–1.54, p = 0.0028).

Conclusions: Non-HDL-CwasU-shapedrelatedtoall-causeandcardiovascular mortalityamongmenwithoutstatintherapy.

Keywords:non-HDLcholesterol,all-causemortality,cardiovascularmortality,U-shapedrelationship,men

ORIGINALRESEARCH published:07July 2022

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 1 July2022 | Volume9|Article903481

doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.903481

17

INTRODUCTION

Non-high-densitylipoproteincholesterol(non-HDL-C),which representsthetotalcholesterolcontentofapolipoprotein B-containinglipoproteins,includesverylow-densitylipoproteins (VLDL)andtheirmetabolicremnants,intermediate-density lipoproteins(IDL),lipoprotein(a),andlow-densitylipoproteins (LDL)(1, 2).Non-HDL-Ciswellestablishedcausalriskfactor forthedevelopmentofatheroscleroticcardiovasculardisease (1, 3, 4).Twodecadesago,non-HDL-Cwashighlightedasan importantsecondarylipidtherapeuticgoalintheUnitedStates NationalCholesterolEducationProgram’sAdultTreatment Panel(5).Furthermore,theNationalLipidAssociationand InternationalAtherosclerosis Societyrecentlyrecommendedthat non-HDL-CshouldbeanequaltargettoLDL-cholesterol(LDLC)inpatientswithatheroscleroticcardiovasculardisease(6). Preponderantly,non-HDL-Ctrajectoriesremainfairlyflat,and non-HDL-Cbetweenage25and40yearsissufficientto confidentlycategoriseindividualsashighorlownon-HDL-C forthenext25to30years(3).Moreover,non-HDL-Ccan beaccurately calculatedinanon-fastingspecimen,without incurringadditionalexpense(7).

Asystematicreviewand meta-analysisbyourteampreviously demonstratedthattheincreasedlevelsofnon-HDL-Cwere significantlyassociatedwithanincreasedriskofmortalityin patientswithcoronaryheartdisease(CHD)(8),whichwas similartoprevious researchfindingsinpopulationwithout cardiovasculardiseases(9)orpatientswithdiabetes(10). Interestingly,aU-shapedrelationshipwasalsorecentlyidentified indifferentpopulations(11, 12).StudiesdetectedtheU-shaped associationofnon-HDL-Cwithall-causeandcardiovascular mortalityamongpatientswithhypertensionorchronickidney disease(CKD)stages3–5(11, 12),non-HDL-CwasU-shaped associatedwith mortalityamongmalehypertensioninsubgroup analysis,butnotinfemale(12).Differently,onestudyfocused onthemen population,fromtheIsraeliNationalDeathRegistry demonstratedapositiveassociationthatnon-HDL-Casauseful predictorofcardiovasculardiseasemortalityin22yearsfollowup(13).Hence,formoreclearlyunderstandhownon-HDLCrelatestoall-causeandcardiovascularmortalityinmen,the aimofthepresentstudyuseddatafromthelargepopulation representativesurveystodeterminetherelationshipofnonHDL-Cwithall-causeandcardiovascularmortality,andthe concentrationofnon-HDL-Cassociatedwiththelowestriskof mortalityinmenwithoutstatintherapy.

MATERIALSANDMETHODS StudyPopulation

Weperformedapopulation-basedcohortstudyusingdata fromtheNationalHealthandNutritionExaminationSurvey (NHANES),anddatawerecombinedacross8continuous NHANEScycles:1999–2000,2001–2002,2003–2004,2005–2006, 2007–2008,2009–2010,2011–2012,and2013–2014.NHANES isaseriesofnationalsurveystoevaluatethehealthstatus oftheUnitedStatespopulationwithacomplex,stratified, multistage,probabilitysamplingmethod.TheCentresfor

DiseaseControlandPreventionratifiedthestudyprotocols,and alltheparticipantsprovidedwritteninformedconsent.Detailed abouttheNHANEShasbeenpublishedelsewhere(14, 15).

Thetotalnumber ofparticipantsinprimarysurveywas 82,091.Afterexcludingparticipantsforage <18(n = 34,735), female(n = 24,534)orwithoutfollow-updata(n = 1,085), andthoseinbaselinewithcancerormissingdata(n = 3,534), acutemyocardialinfarction(AMI)ormissingdata(n = 952), heartfailure(HF)ormissdata(n = 331)andexcluding becausecovariateswereunavailable(n = 2,455),finallyexcluding forbaselinewithstatintherapy(n = 1,891).Hence,12,574 individualswereincludedinourfinalanalysis(Figure1).

Covariates

Fastingsamplesobtainedfromperipheralvenousbloodwere storedat 20◦Candshippedweeklyforlaboratoryanalyses. Non-HDL-Clevelswerecalculatedfromtotalcholesterol (TC)minusHDLcholesterol(HDL-C).Themeasurementof TCusedwithanenzymaticassaymethod,andHDL-Cwas usedwithaheparin-manganeseprecipitationmethodora directimmunoassaytechnique.Furtherdetailedinformation aboutthecollectionofbloodsamplesandlipidconcentration measurementisavailableinanotherstudy(16).Inaddition, creatinine,haemoglobin,andglycatedhaemoglobinA1c (HbA1c)measurementswerebasedonstandardisedprocedures. Demographicvariablessuchasage,gender,bodyweight, height,race/ethnicity(MexicanAmerican,otherHispanic, non-HispanicWhite,non-HispanicBlack,otherrace),education (Lowerthanhighschool,highschool,morethanhighschool), wereacquiredaccordingtothehouseholdinterview.Information onsmokingstatus(currentsmoker,formersmoker,andnever smoked),andhistoryofdiseasehadbeenassessedatbaselineby standardexaminations,andquestionnaireswereadministered bytrainedhealthtechnicians,interviewers,andphysicians.The meanbloodpressurewascalculatedastheaverageofthreevalid measurements.Nutritionalstatus(e.g.,energyintake,protein intake,carbohydrateintake,totalfatintake)wasacquired accordingtothedietaryinterview.A“multiplepass”24-hdietary interviewformatwasusedtocollectdetailedinformationabout allfoodsandbeverages,whichwereusedtoestimatethetotal intakeofenergy,nutrients,andnon-nutrientfoodcomponents. Moreinformationisavailableatwww.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

Outcomes

Theprimarydeterminationofmortalityforeligibleparticipants isbaseduponmatchingsurveyrecordstotherecordsfromthe NationalDeathIndex(NDI),andothersourcesincludingthe SocialSecurityAdministration,theCentresforMedicareand MedicaidServices,datacollection,andforthefollow-upsurveys oftheNationalCentreforHealthStatistics,ascertainment ofdeathcertificatesarealsoincorporated.Participantswere eligibleformortalityfollow-upbasedonmatchingidentifying informationduringtheirNHANESinterviews,suchasthelast 4digitsofsocialsecuritynumber,fullname,dateofbirth,state ofbirth,stateofresidence,maritalstatus,race,andsex(17).Allcausemortality and cardiovascularmortalityweretheendpoints ofthepresentstudy.Themortalitystatusofindividualswas

Zengetal. Non-HDL-CandMortalityinMen

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 2 July2022| Volume9|Article903481 18

obtainedfromdatafromtheNDIthroughDecember31,2015. Thisstudyclassifiedcausesofmortalityreferredtothecodesof theinternationalstatisticalclassificationofdiseases,10threvision (ICD-10).CardiovascularmortalitywasdefinedbytheICD10codesforasI00-I09,I11,I13,andI20-I51.Whentreating cardiovascularmortalityasanoutcome,thedeathsduetoother causeswerecensored.

StatisticalAnalysis

Thedatawerepresentedasmeanvalueswithstandarddeviation (SD),themedianwithinterquartileranges,orfrequencieswith percentages,asappropriate.Comparisonsofthedifferences betweengroupsweremadewithone-wayANOVA,chi-square tests,orKruskal–WallisH-testsbytheclassificationofnon-HDLClevels(<100,100–129,130–159,160–189,190–219, ≥220 mg/dl).Survivalanalysisaccordingtonon-HDL-Cstratification wasperformedusingstandardisedKaplan–Meiercurves.The proportionalhazardassumptionwasexaminedandmetby plottingthelogminuslogsurvivalcurvesandsurvivaltimes. ThemultivariableCoxproportionalhazardsmodelswereused

forexploringtheassociationofnon-HDL-Cwithall-causeand cardiovascularmortality.Inmodel1,therewasnoadjustment. Inmodel2,weadjustedforageandrace.Inmodel3,we adjustedforage,race,education,bodymassindex(BMI),systolic bloodpressure,diastolicbloodpressure,smoking,diabetes, hypertension,CHD,stroke,creatinine,haemoglobin,HbA1c, triglycerides,energyintake,proteinintake,carbohydrateintake, andtotalfatintake.Restrictedcubicsplinemodelswereused fornonlinearrelationshipswithknotsat5,35,65,and95 percentilesofnon-HDL-C.Iftherelationshipswerenon-linear, thedifferenceofrelationshipsatthethresholdwasdetected bytwopiecewiselinearregressionmodels.Thepointwiththe highestlikelihoodamongallthepossiblevalueswaschosento definethethresholdvalue.Thedifferencesintheresultswhen applyingone-lineortwopiecewiselinearregressionmodelswere comparedbyalogarithmiclikelihoodratiotest.Furthermore, thesubgroupanalysisincludesage(<65or ≥65years),race (White,Black,orotherrace),education(lowerthanhighschool, highschool,morethanhighschool),BMI(<25or ≥25kg/m2), smoking(yesorno),diabetes(yesorno),hypertension(yesor

Zengetal. Non-HDL-CandMortalityinMen

FIGURE1| Studyflowchart.NHANES,Nationalhealthandnutritionexaminationsurvey;AMI,acutemyocardialinfarction;HF,heartfailure.

FrontiersinCardiovascularMedicine|www.frontiersin.org 3 July2022| Volume9|Article903481 19