Cinematic Postmemory: Reproduction and Reclamation of Memory of the Cultural Revolution through Spaces in the Fifth Generation Chinese Cinema

Jingzhi Yang Fitzwilliam College

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Part II of the Architecture Tripos 2022

April 2022

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my great appreciation to my supervisor, Yufei Li for her patience, encouragement and intelligence in guiding me through the planning and development of this research work. I would also like to thank Dr Janina Schupp and Dr. Maximilian Sternberg for the most engaging lecture series on cinematic architecture and Berlin memory landscape that elicited my initial research interest.

I am particularly grateful for my family and friends for their unwavering support throughout my writing process and for sharing with each other our love for film and this world.

Word Count of Texts and Notes Combined: 8993 words

Word Count of Bibliography: 1255 words

Abstract

This research investigates how films provide cinematic localised memoirs that act as sites of memory, lieu de mémoire in aiding the trans-generational traumatic transfer that can be understood as postmemory. Using the Chinese Cultural Revolution as the historical framework and the films Blue Kite and Farewell My Concubine as the object of study, this research identifies three spatial layers of the memory landscape: transit space, public space and private space, as well as the mnemonic system they form. It demonstrates the reconstruction and reclamation of memory through the intersection of the hard and the soft, the material and non-material, the physical and the performative in cinematic spaces. The process is conceived as an ever-evolving self-aware knowledge production from both the directorial and spectatorial perspective that simultaneously allows the grounded search of roots in the past and the proliferation of meaning in the future, a recreation of memory that avoids and rejects the compilation of mainstream history.

List of Figures

Fig. 1 the Now Deserted Street Set in Beijing Film Studio and a Corresponding Scene in Farewell

Fig. 2 Yang’s Hand Rendering of the Street Set Design Across Time

Fig. 3 Dry Well Lane

Fig. 4 the Tracking Shot Following Dieyi's First Encounter With the Street

Fig. 5 Second Street Sequence

Fig. 6 Third Street Sequence

Fig. 7 the Last Street Sequence

Fig. 8 Starting Street Scene in Blue

Fig. 9 Public-Private Partnership Movement

Fig. 10 Public Meeting in Anti-Rightest Campaign

Fig. 11 Four-Pests Campaign

Fig. 12 Street Furnaces in the Great Leap Forward Movement

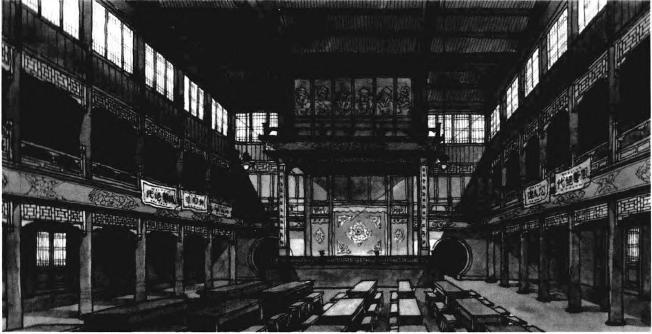

Fig. 13 the Design Rendering of the Opera House Interior

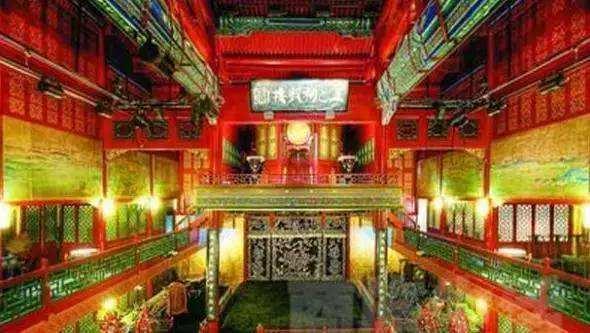

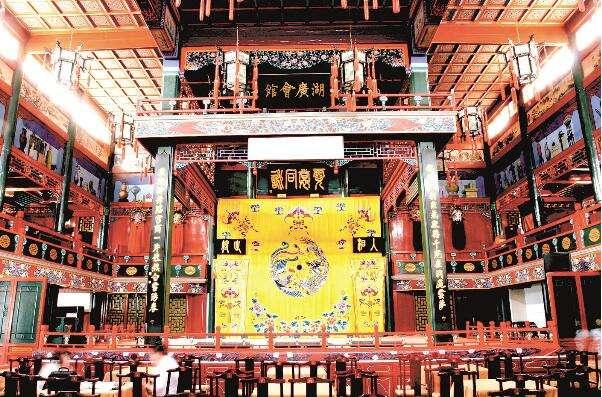

Fig. 14 Interior of Huguang Guild Hall(Left) and Yangping Guild Hall (Right)

Fig. 15 Initial Scene of the opera house

Fig. 16 During Japanese Occupation

Fig. 17 During the Rule of Nationalist Party

Fig. 18 After the Communist Party Took Over

Fig. 19 During Anti-Rightest Movement

Fig. 20 Cultural Revolution Stage

Fig. 21 Aftermath of the Denunciation Rally

Fig. 22 Full Shot of the Hall

Fig. 23 Library Scene

Fig. 24 School Scenes

Fig. 25 Moving in

Fig. 26 the Courtyard as the Kid’s Playground

Fig. 27 the Courtyard for Neighbourhood Interactions

Fig. 28 the Threshold Area

Fig. 29 the Deserted Room

Fig. 30 Peaking Into the Expropriated House

Fig. 31 Sketch Plan of the Room

Fig. 32 Contrasting Room Interior

Fig. 33 Changing Posters That Respond to Different Revolutionary Movement

Fig. 34 Dazibao in the Interior and Exterior

Fig. 35 Party Semiotics Placed Between People

Fig. 36 Dining Scenes in Grandma’s House

Fig. 37 Interior shots of Xiaolou’s Home: Wedding - Burning of Four Olds - Juxian’s Suicide

Fig. 34 Dazibao in the Interior and Exterior

Fig. 38 Close-Up Shots of Juxian’s Items

Fig. 39 Spatial Mnemonic System of Blue

Fig. 40 Spatial Mnemonic System of Farewell

Introduction

Memory is a slippery thing. It is abstract, subjective, sometimes imperceptibly transient while other times painfully ineffaceable. It informs our self-identity and sense of being in the world. While we more frequently conceive of memory on private levels, it would be limiting to dismiss the influence cast by the public sphere — memory is shaped by the collective consciousness as much as it is by the personal. This dissertation frames itself based on a special kind of collective memory -- postmemory. A concept articulated by Marianne Hirsch (2008), postmemory describes the transmission of powerful, often traumatic experiences to the second/third generation, so deeply that such traumatic occurrences preceded their births seem to constitute memories in their own right. Due to the inability to directly access the collective memories, these experiences are more often felt as distant historical phenomenons and mythical concepts despite their impact and significance. In this regard, postmemory is about the negotiation of memory and trauma from the generation that recalls to the generation that imagines. How can postmemory be established? While Hirsch (2008) examines the remembrance of the Holocaust through photography as the medium and family as the language, this dissertation explores how films as the medium and spaces in films as the language serve such intergenerational knowledge transfer in enabling the recovery and reclamation of memory.

The historical frame of reference this research engages with is the Cultural Revolution of China. Postmemory is particularly meaningful and relevant in this case, as the existing collective impression remains ambiguous, convoluted and conflicted while the personal memory is often unattainable through official frameworks. Building on the idea of 'sites of memory' and how spatial participation in history brings greater proximity to the past generation's experiences, the absent, diminished or altered nature of existing sites of memory justifies the necessity of finding such spaces through cinema. Such cinematic-localised memoirs complement the real landscape of utter voids and half-truths, where juxtaposition and discontinuity between the imagined and the real present both challenges and opportunities. The films studied are Farewell my Concubine(1992) directed by Chen Kaige (Farewell in short), and The Blue Kite (1993) by Tian Zhuangzhuang (Blue in short).

This research is first contextualised by the history of the Cultural Revolution, the background and outline of the two films in relation to it. It then establishes the key concept and theoretical framework, unpacking the foundational texts that explore the relationship between film, space and memory. It is about how film as a spatial-visual assemblage in motion offers an embodied (re)construction of a composite, metamorphosing

memory landscape and how spatial participation in film allows for memory recovery. Based on such relationships, the research methodology is built and and the research discussion follows.

I hope this study becomes a vicarious voyage of memory reclamation that bridge the alliance and irreconcilability with the National past is so influential yet distant. With such re-elaboration of history through memory, a more rooted definition of our cultural identity can be developed to enable a more informed and grounded mourning, reconciliation and edification. This embodied and reflexive re-engagement with filmic space becomes a gathering process that reconstructs memory, in establishing a more authentic contemporary relationship with the past and not to be caught only in the competing instincts of grand historical narrative.

2.1. Historical Context : Cultural Revolution, Scar Cinema and 'the Fifth Generation’

The Cultural revolution is a decade of chaos and political upheaval that lasted from 1966 to 1976 that is rooted in a factional dispute over the future of Chinese socialism.('Cultural Revolution', 2015) With deStalinization in the Soviet bloc and the political fallout from the disastrous Great Leap Forward, oblique criticisms of Mao in the early 1960s prompted him to retaliate against this threat from more pragmatic and bureaucratic modernizers with ideas closer to the Soviet Union. (Walder, 2017) Discontented young students and workers are mobilized as Red Guards to attack officials labelled as 'bourgeois' infiltrators. They soon splintered into zealous rival groups and many intellectuals were purged, verbally attacked, physically abused, and subsequently died. The resulting anarchy, terror and paralysis thrust China into 10 years of turmoil, bloodshed, hunger and stagnation.

The Cultural Revolution left a deep mark on those who experienced and witnessed it. Deng Xiaoping, the formal Party general secretary who was a purge victim was brought back to power after its end. He led the 'eliminating chaos and returning to normal (拨乱反正)' programme aiming to correct the mistakes of the Cultural Revolution. (Vogel, 2011) Amongst reinstating the wrongfully prosecuted cadres and intellectuals, initiating various socio-political reforms, it also encouraged greater autonomy in arts. Scar Literature first emerged in this context, portraying the trauma and oppression of citizens during the Cultural Revolution. This reflection on the harsh realities of the cultural campaign also extended to the Chinese cinema and initiated a film genre that became known as 'Scar Cinema'.

The immediate objects of this study, Farewell and Blue, both fall into this genre of Scar Cinema. Both directors, Chen and Tian, belong to the 'Fifth Generation' filmmakers who defined their status as the first group of graduates from the Beijing Film Academy where they studied from 1978 to 1982. They came of age during the Cultural Revolution - Chen joined the Red Guards as a teenage member and denounced his father while Tian became a ' sent-down youth (zhiqing 知⻘)' working in the countryside of Jilin whereas both of his parents were persecuted. Such formative experiences render the memory of the Cultural Revolution to be the dispensable framework, both psychic and historical, that is crucial to understanding their works.

2.2. Filmic Context - Synopsis of Farewell and Blue

Blue employs a young boy, Tietou's perspective and the site of the family as the microcosm of historical crisis to reveal how political history disrupts and damages private family life. Major historical events of the 1950s and 1960s such as the Hundred Flowers Movement and Anti-Rightest Campaigns, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution are portrayed alongside the Tietou's maturation story and the sequential deaths of his three fathers.

In contrast to Blue which focuses on historical events directly associated with the Cultural Revolution, Farewell is more extensive in its meticulous depiction of the events preceding and following it. Charting the tumultuous course of the country from 1924 to 1977, it chronicles the troubled relationships between two Peking opera actors Cheng Dieyi and Duan Xiaolou, and Xiaolou's wife Juxian. It is not only an epic spanning a half-century of modern Chinese history but also a melodrama about life backstage at the famed Peking Opera House.

2.3. Literary Context - Study on Film, Space and Memory

i. Film and Memory

Amongst other impacts, the Cultural Revolution left a severe generation gap especially when the atrocity and trauma seemed too harsh to be conceivable. In this regard, with a widespread domestic and international claim that lasted for decades, Blue and Farewell has far exceeded a personal retrospection by the directors and become a gateway for the establishment of postmemory.

The framework of discussion lies in memory rather than history. French historian Pierre Nora (1989) has argued that while history is often a "reconstruction" of the natural process of memory under the auspices of an intellectualized and rationalized regime, memory is borne naturally in societies to preserve identity and transmit value from one generation to the next. Memory is employed as a means for individuals and the societies they constitute to understand themselves.(Ibid) Unlike history, memory is not subjected to the

official framework of a necessary rectification. It constitutes a polyvocal and eclectic culture as experienced at the street level, rather than only as seen from within the party hierarchy with a single source of authority.

As one's contemporary relationship with the past is caught between these two competing instincts of history and memory, alternative referencing frameworks are crucial in protecting the autonomy of memory from the internal coercion by the collective historical narrative. The knowledge transfer through film hence becomes the intellectual operation that renders such memory intelligible - as Nora (1989, p13) writes, 'Modern memory is, above all, archival. It relies entirely on the materiality of the trace, the immediacy of the recording, the visibility of the image'. Whether or not the filmmakers are using their films as a direct commentary on the historical event, creating films can be seen as a self-conscious appropriation of their own memory, while for audiences watching films is often about a temporal, reflexive and embodied engagement with particular ways of being. It is a gathering process occurring from both sides that naturally enables an open-ended ramification of meanings.

Many film reviews and interviews on Blue and Farewell have reflected on the creation and reading of film through the lens of memory. Blue can be conceived of as a testimony of memory fragments called forth by the first-person narrator (Wang, 1999) The script by Xiao Mao is based on Tian's own family history (Sight and Sound, 1994) and the impressions of 'witnessing' and the sense of indefinable loss and yearning in the film are moulded by Tian's childhood experience of bewilderment and searching. (Wu, 1994) In turn, the unsettling quality of memory portrayed offers a more critical way of understanding our relation to the past as it 'encourages a scepticism that has the potential to keep historical knowledge unstable and uncertain'(Wang, 1999, p19) Similarly, Chen talked about pouring his personal emotion into Farewell and that it has been 'eternally merged into' his feeling for his family.(Public Class in Beijing Film Academy: Everything about Farewell, 2018) The melodramatic reversals and twists, the refusal of distinguishing the good and the evil are about rejecting notions of continuity, objectivity and closure in traditional historical discourses and affirming knowledge as perspective. (Ma, 2003) Both films seek to deconstruct the 'grandnarrative' of social revolution by providing a counter-narrative of traumatized individual life (Zhang, 2003)

ii. Space and memory

Regarding the medium of transgenerational transmission of memory, Nora has also raised the notion of 'sites of memory', lieu de mémoire, which gives prominent attention to the various ways in which memory is spatially constituted. Just as how anthropologist Nathan Wachtel notes, 'the preservation of recollections rests on their anchorage in space'(Hoelscher & Alderman, 2004), Nora (1989) elucidates that memory is attached to sites that are concrete and physical that embody tangible traces of the past; as well as to sites that are non-material that provide an aura of the past. Traversing through the existing memory landscape allows one to experience the memory from the inside, rather than existing only through the exterior scaffolding of words and outward signs of photographic images.

iii. Film, space, and memory

With the repudiation of the whole of the Cultural Revolution as a 'decade of chaos', survived sites are often found as landscapes of doubts, lies and absence. In this context, films have the qualities to become such sites of memory where spatial participation can occur. Films are a spatially located, volumetric presence and film practice occurs from and through particular sites (Koeck & Flintham, 2017; Hay, 1997 ) As Tschumi (1994,p7) writes, reading of dynamic architectural space 'does not depend merely on a single frame, but on a succession of frames or spaces' while Eisenstein (1989,p117) argues that film creates 'a montage sequence for an architectural ensemble… shot by shot', there is an inherent connection between how we read spaces and experience films. Spaces are to be viewed and appreciated in motion while the film is a spatial-visual assemblage in motion -- Architecture is filmic and film is architectural. (Bruno, 2007)

In addition, through the incorporation of the movement, films interrogate the flows and rhythms of spaces and provide the audience with the sense of moving through, of being in the city (Penz, Reid & Thomas, 2017). Films are simultaneously socially located and participate in the constitution, maintenance, and transformation of society and culture (Berry, 2004). Being both a spatial and temporal medium, they chart the physical transformation, social and cultural mutations. Therefore, as the plural framing of reality parallel to our world, films build up cinematically localised memories and accelerate the process of identification by allowing one to feel similarly emplaced (Cinquegrani, 2017).

As Jacques Derrida (1996) argues that the form of archived material is crucial to the kind of memory forged within it, this research builds on the aforementioned framework exploring how film and space carry memory respectively and bridges the gap by demonstrating that spaces in films are nevertheless powerful sites of memory. Reading of space through film provides the physical anchor to film for memory to 'crystallise and secrets itself' (Nora, 1998, p7) while adding a performative dimension to spaces for memory to emerge and develop. 'The very heart of geography - the search for our sense of place and self in the world - is constituted by the practice of looking and is, in effect, a study of image' (Aitken & Zonn, 1994, p7). As spaces in films become sites of memory that transfer the knowledge of past generations, it mediates our relationship with the world as well as our conscious perception of it. In establishing such a postmemory we decipher what we are in the light of what we are no longer.

Methodology

This dissertation is very much a personal gathering process whose methodology integrates the foundational theoretical framework on space and film. The spaces in the two films are treated not as discrete pieces but rather memory fragments that connect as layers to form the cinematic-localised memory landscape this research retrieves and reconstructs. Space is treated not only as a concrete existence but also all that is hidden beneath it and emerges from it. The attention is on the space itself as much as what is in between, the material and the non-material, the hard and soft, the performative and the physical, the sight and the site.

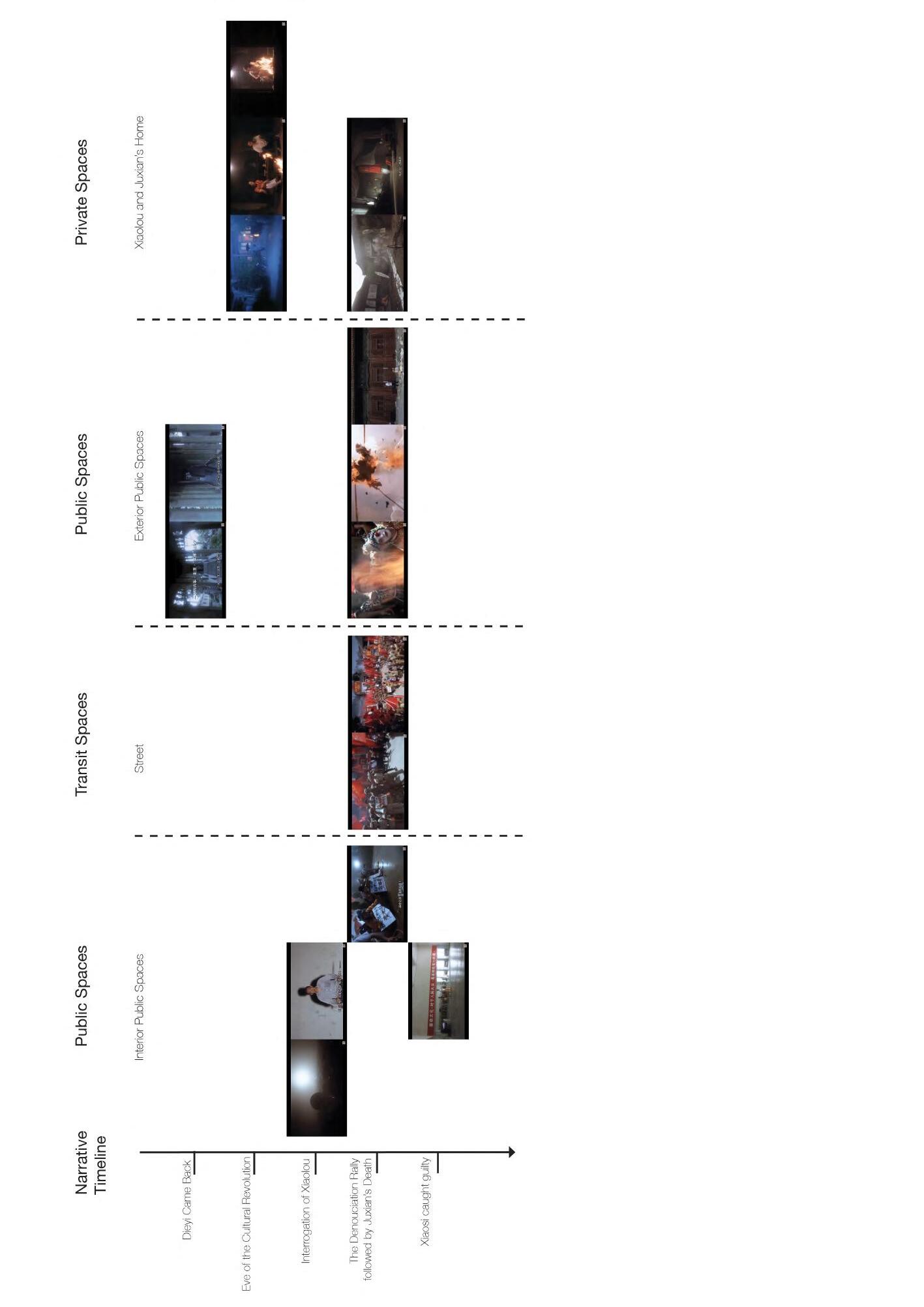

The overall structure of discussion hence builds upon such a progressing relationship: spatial fragmentsspatial layers - spatial system/landscape. It progresses through different categories of spaces: from the transit spaces which establish the generic and the universal, to the collective/public spaces of the new normal/abnormal, and finally the private spaces of submission and resistance. Each category of space is a layer in the memory landscape - the often anonymous road that sets the background generic city, with distinctive places that root the film spatially and temporally; the everyday, the non-iconic intertwining with the iconic. (Penz, Reid & Thomas, 2017) The spatial relationships explored within and in between the layers are very much correlated with the nature of memory of cultural revolution: long-lasting, infiltrating, escalating trauma interwoven into the filmic everydayness, with significant historical moments marking the crossing of the collective narrative and personal memory.

For each spatial layer, the discussion zooms in to look at the intertwining portrayal of 'hard' sides and the 'soft' sides of the spaces. The 'hard' side - the material, spatial aspect is studied through the mise-enscene, the semiotics and topology, as well as the film-making techniques such as photography, movement and editing that reveal the logic of the spatial relationships. The 'soft' side - the non-material, performative aspect is read from the multitude of narratives and activities surrounding the space. These two sides are interwoven through elements of time - both film as the repertoire of urban archaeology where not only the space but meaning associated with the space constantly evolves, as is memory. Both the hard and the soft are examined through the lens of its filmic social and historical context, while memory will be discussed with architectural discourse such as the public/private sphere, theatricality and everydayness etc. The complementary relationship between the two films is also explored.

Simultaneously, the discussion zooms out to look at the site - how the imagined reality is linked to the real reality and how the site-specificity/non-site-specificity can add additional layers of reading into memory.

Building on this and the previously studied spatial layers, an overall analysis of the spatial mnemonic system is carried out. The underlying logic sustaining the spatial sequencing is studied as the flow of movement between the memory landscape. Through the spatial relations memory is nurtured and maintained in the cognitive mosaics of the human brain.

The issue of spectatorship also comes into play here - the meaning of any text is intermediate - this dissertation lies upon a self-awareness - that of the filmmaker that reappropriated the memory, and that of me as an interpreter that attempts to retrieve this memory. As 'memory is forged always within the contingencies of the moment rather than as a verifiable truth'(Pratt, 2014), I am not arguing for the possibility of production of a universal knowledge immanent to the film but what such interpretative framework made possible. As Nora (1989) argues, sites of memory exist for their capacity for metamorphosis and the endless recycling of meanings - spaces in the film become sites of memory for it instils varied and evolving interpretation as a realm of ambiguity and imagination. It is not suppression but rather an exploration of the myriad possibilities, dense complexity, and unspeakable moments of sorrow in memory.

4.

4.1. Transit Spaces of Urban Archaeology

Transit spaces – streets form the first layer of the memory landscape. They are sites of urban archaeology that link temporal experiences to spatial experiences, personal memory to collective narratives, and everydayness to key historical moments. Both films start with scenes of a street that was presented repeatedly as backdrops of the trials and upheaval of the era. They function as a metamorphosing syntactical system and mark out how meanings associated with the same location change over time.

In Farewell, key street scenes are filmed from a constructed streetscape by the art director Zhanjia Yang. Yang in his interview mentioned that sufficient budgets permitted the construction of a real street (Fig. 1). Creating an immediately recognizable and relatable Beijing character that felt authentic was the key direction of the set design(Yang, 2010). From Yang's perspective design renderings (Fig. 2) one can notice many typical 'Old Beijing' street features such as the archway, the traditional pitched-roof timber-skeletonon-masonry-platform Chinese houses, as well as colonial-influenced concrete structures, and signs of early modernisation like the utility pole. These concrete architectural features immediately root the film geographically, socially and historically, while the changing fabric and settings mark the time. Almost an archaeological site where the holistic perception of the space brings us immediately back in time, it heightens the very space of transit as transition. (Bruno, 2007)

Fig.1 the Now Deserted Street Set in Beijing Film Studio and a Corresponding Scene in Farewell

Similarly, such ambience of familiarity and deja-vu is also created in the streets of Blue, which employed location shooting rather than studio sets. A street in the bustling residential corner of Beijing constitutes the first few scenes of the film(Fig. 3) The voice-over of an adolescent narrator speaks in a nasal tone, introducing Dry Well Lane (Ganjing Hutong), the stage on which intricate personal, social and political relations are about to converge. There indeed exists a Dry Well Lane in Beijing yet it is not clear from the film itself whether associations can be made to the real site – the director might have just borrowed the name as the photography has omitted any traces of site-specific information. Often shot from a bird's eye view, everything seen in the setting - chimney and smoke in the coal-burning winter of Beijing, a cart pulled by a donkey and children playing on the street – gives rise to a sense of the timelessness, eternal, ordinary folk's Beijing.

Fig. 2 Yang’s Hand Rendering of the Street Set Design Across Time

As such, the streets in both films are not site-specific that they cannot be pinpointed exactly on the map, yet site-specific that one can immediately associate them with the Old Beijing. As memory sites, they can be anywhere but are to be found nowhere. Such in-between states of distancing and immersion simultaneously offer a sense of historical embeddedness that empowers a more empathetic transfer of knowledge; while retaining the 'self-awareness' of a space bonded to a very particular social and historical context - an everlasting irreconcilability that marks the backdrop of memory reclamation.

Besides setting up the relationship with the real, streets in both films also perform as powerful memory devices – sites of cinematic urban archaeology, fixed backdrops that register and record over time the changes in the fabric of a location (Penz, Reid & Thomas, 2017) The streets become a signpost as the narrative propels forward with key historical stages. The physical transformation of the street recognises social and cultural mutations and is made more prominent with repeating spatial sequences created by similar shots.

Fig. 3 Dry Well Lane

The street in Farewell initially represents an outside world of hopes and dreams for Dieyi and his fellow trainees in the opera house, as they run to follow the carriage of famous opera singers. The street here is a bustling marketplace with busy pedestrians in traditional Manchu long robes (⻓衫, Changshan), food vendors, stalls and booths selling hand-crafted items. The long take follows the main characters through the journey and their walking/running through the street literally unfolds the drama step by step(Fig. 4)

Similar sequences of roads are shot three more times in the film. The second time is the night before the Marco Polo Bridge accident (1937) when both Xiaolou and Dieyi had become established Opera Singers. As the camera follows their rickshaw, it shows that although the market still exists, the mise-en-scene of patrolling soldiers, Japanese flags, and citizens holding banners shouting revolutionary slogans signifies the forthcoming upheavals. (Fig. 5) The third time is when Dieyi's adopted child Xiaosi runs through the street as the communist party army marched into the city(1949). The old market has almost been fully engulfed by the crowd that gathered to welcome the soldiers. The shop signages were submerged by the national flag and party emblems. (Fig. 6) The street last appeared at the climax of the film during the Cultural Revolution(1966) when Dieyi and Xiaolou were pushed across the street for a public denunciation rally. At this point, the overwhelming amount of red flags, portraits of Mao and lunatic crowds and red guards have fully swamped the street scene. The intensification of the red color that appeared on the street across time also reaches its climax. (Fig. 7)

Fig. 4 the Tracking Shot Following Dieyi's First Encounter With the Street

In addition to the metamorphosis of the mise-en-scene, the camera as the imaginary eye of the director also reflects much about the directorial narrative, and in its positioning and movement conveys how they have engaged with their memory. Like a theatrical voyage whose hustle and bustle only reveals itself gradually, the street in Farewell can not be comprehended in one shot. In all the sequences, the street is conceived as a site to be viewed and appreciated in motion. In turn, the kinesthesis, the ability of bodies to sense their own movement in space, becomes the agent in the formation of space. As Eisenstein writes, 'Space…exists in a social sense only for activity – for (and by virtue of walking)' (Bruno, 2007) Each time we ride the vehicles of the camera in these scenes, a communicative sense of spatiality and mobility was constructed as the space and the activity converge to form the bodily memory. The strong sense of personal engagement with the space works in accord with the very emotionally tainted nature of the memory.

Fig. 5 Second Street Sequence

Fig. 6 Third Street Sequence

Fig. 7 the Last Street Sequence

Similarly to the Farewell, Blue also covers a substantial period of history through three episodes, entitled 'father' 'uncle' and 'step-father' that each corresponds to a particular moment of national history: The antirightest campaign (1957), the three years of Natural Disaster (1958-1961, code-word for the massive famine resulting from the Great Leap Forward Movement) and the Cultural revolution. The first episode starts with the family moving into their new house in Hutong. At this point, the street is where kids play and where social interactions between neighbours occur. (Fig. 8) However, this calm and peaceful ambience was breached by the pre-Cultural revolution movement as neighbourhood community leaders enforce the public-private partnership scheme. (Fig. 9) It then becomes a place of propaganda and mass meeting and kickstarts a process where the public power increasingly erodes into the private sphere (Fig. 10) A threshold between the private and public, the street becomes the stage where this corrosion is registered. Set in great contrast with the initial scene where individuals are left alone minding their own business, in the following scenes individuals become crowds, the crowds become increasingly franzier(Fig. 11) In the early stage the marching crowds are still restricted to the streetscape, only invading the airspace with the beating gong.

But as the film progresses they are no longer confined - door sills are crossed, roofs are climbed - the physical boundary dissolves, as is the autonomy of the private realm. Personal rights are to be sacrificed for the greater common good, as streets become sites of steelmaking during the Great Leap Forward, private properties are brought into the street to be thrown into the communal steel furnace. (Figure. 12)

Fig. 8 Starting Street Scene in Blue

Fig. 9 Public-Private Partnership Movement

In contrast to the dynamic eye-level long take in the photography of Farewell, Blue favours more static camera movement with high angle and panoramic shots. It is never allied with the viewpoint of a character to any significant degree. The visual-audio combination – the omniscient perspective of the camera and the dispassionate voiceover – create a sense of detachment. Unlike Farewell where the main characters stand out from the background crowd, it is hard to mark out the main character who are all subsumed into the rhythms and flows of their life. Although simple and modest, Dry Well Lane is a reminder of a swamp of mundane life-world. The unchanging architectural features of the street serve as a tranquil and passive ground on which the catastrophe amass its narrative energy. And it is through such constant beneath the whirlwind of change, the timelessness that underscores the eventfulness of political revolution, memory is preserved.

Fig. 10 Public Meeting in Anti-Rightest Campaign

Fig. 11 Four-Pests Campaign

Fig. 12 Street Furnaces in the Great Leap Forward Movement

4.2. Public Spaces of Inescapable Collective Destiny

While Streets in both films perform as sites of urban archaeology where memories of key historical moments reenact and unfold, it is at the key public spaces where the inescapable thrust of the historical forces on the destiny of groups and individuals are most felt. The portrayal of such spaces in the two films continues to register a complimentary style of captivating theatricality and immersive everydayness.

The Peking Opera House is the most significant public space featured in Farewell. Similarly to the street, it quite literally becomes the 'theatrical backdrop' of the frontstage panorama. The interior of the opera house is a set (Fig. 13) which has referenced Huguang Guild Hall and Yangpin Guild Hall (Fig. 14) (Yang, 2010).

Unlike the typical contemporary theatre with a sloped ground, the traditional opera house has a flat plaza that is flanked by collonaded corridors and viewing boxes. The stage is a two-level elevated pavilion attached to the backstage and the tables are arranged vertically rather than facing the stage (People 'listen to' rather than watch the opera).

Fig. 13 Yang’s Design Rendering of the Opera House Interior

Fig. 14 Interior of Huguang Guild Hall(Left) and Yangping Guild Hall (Right)

While the architectural skeleton of the opera house remains largely similar, the Mise-en-scène makes the historical changes readily visually comprehensible. In comparably more peaceful times while the film first started - 1925, a time of warlords' rule and the heyday of the Peking Opera, the flags hanging from the second-floor wooden railings often imprint names and praises of the opera performers. As China swirls into the later historical turmoil from the Japanese invasion, the takeover by the Nationalist party and the inexorable rise of the Communist Party(Fig. 15, 16, 17), the worship of individuals certainly had to give way to that of the collective power struggle. Regardless of the group in control, hanging of the national/party flag seemed to be a common way of exerting dominance in the space which itself embodied a dual function of public gathering and power display, with the opera art having both royalist and bourgeois origin and grassroots popularity. The resurgence of similar scenes also elevates the notion of the past as a vicious cycle or a wanton process under the mercy of the supervising regime(Ma, 2003).

When comparing across time, the increasing degree of interior changes of the opera house echoes an expanding degree of disruption. During the earlier war times, the stage is still kept the same despite the changing ruling power. When the Communist Party first takes over the city, the early cult of personality started to surface as the plaque which once writes 'best voice of the age' (盛世元⾳) is replaced by the portrait of Mao and Zhou (Chairman and Premier of PRC)(Fig. 18). As the Cultural Revolution hits, even its original function as an opera house no longer holds - a mere backdrop for denunciation rallies, the portrait of Mao and the class struggle slogans dominate the space(Fig. 19). In its last appearance, the opera house becomes barely recognizable. The stage curtain is replaced by the drawing of the Tiananmen square as it now serves the new function of the discussion of Revolutionary Opera (yangban xi, 样板戏)(Fig. 20) New orders continuously replace the old ones and the voice of the coming era eventually overwhelms that of the past.

Fig. 15 Initial Scene of the Opera House

Fig. 16 During Japanese Occupation

Fig. 17 During the Rule of Nationalist Party

Fig. 18 After the Communist Party Took Over

Fig. 19 During Anti-Rightest Movement

Fig. 20 Cultural Revolution Stage

At each of its appearances, the Peking Opera house is frequently established with a long shot from a high angle to encompass a fuller vision of the interior, allowing it to be recognised and compared easily across time. Despite the film's ambition in covering such an extensive period of history, the events are not felt with a sudden rupture but rather a sort of embeddedness and continuity. With the Opera House as one of the prominent example, audiences are thus able to reimagine how the once familiar fabric in daily life gradually changes - the meticulous inclusion of what comes before and after the Cultural Revolution portrays it to be the climax of an escalating drama rooted with historical origins instead of a standing-alone event. The damage is not done in a single day - the individual gives way at first, then the space and eventually the art and the culture it represents. The typology of the theatre is particularly powerful here. It is as if there are two levels of plays going on in front of the stage - one is that of the Peking opera and the other is that of the history itself - the interior changes are about the irresistible corrosion from the latter to the former. The playwithin-play highlighted the sense of illusion that it is impossible to seek condolence through art and culture in the constant calamity of reality.

While the Opera House remains to be a set design, other public spaces featured have made use of real sites for their symbolic dimension and enriching narrative. For example, the emotional climax of the film is the public denunciation rally where the two characters are forced into publicly humiliating each other. Chen shot this in front of the Hall of Great Accomplishment (⼤成殿, Dachengdian) of Beijing Temple of Confucious, the temple where imperial officials of the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties hosted ceremonies to pay formal respects to Confucius. The aftermath of the scene features Dieyi kneeling in the ashes, his curling body only seems more insignificant in contrast with the grandeur of the hall(Fig. 21). The following scene zooms out and features the entirety of the hall with the staircase leading up to it. (Fig. 22) The wideangle static scene is almost slightly perspectively distorted to heighten the innate order, rhythm and symmetry of the hall. Under such a backdrop either the mess of the rally slogans or the human figure seems trivial and superficial, hence portraying a sense of the irresistible authoritarian history dominating individual destiny. The narrative provided by the connotation of the building itself gives the already emotionallycharged scene a magnifying degree of irony and tragedy. The plaque that writes 'master of all ages' (万世师 表, Wanshishibiao) reminds one of the traditional ethical systems of Confucianism that values virtues such as loyalty, honesty and truth. Under the violent and intrusive forces of such trauma where one survives off attacking the other, what is right and wrong no longer holds and traditional virtues are dusted and forgotten.

Although not directly included in the film, there is a tradition in the Cultural Revolution to destroy the four olds - things related to 'Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Customs' - the Confucius Temple in Beijing was indeed vandalised and used as a ground for public humiliation in the Cultural Revolution. Therefore, setting this significant climactic scene here imbues the film with multiple narrative layers.

Historically it is a reenactment of the many denunciation rallies that have happened in similar spaces where the destruction of such meaning-ridden places itself represents the barrenness of existential meaning and the ruins of value in the massive catastrophe. For the filmic characters, it hints that perhaps to a certain extent, the traditional ideologies have not only shaped their lives but also contribute to their suffering(Ma, 2003). Cultural Revolution is a blow that destroys one's relation to the cultural fabric of meaning and value. (Wang, 2009). It also alludes to the conflict between the expectation of an ethical system (Confucianism) and the demands of a political system (Socialism), a condition that typifies the Chinese dilemma of modernisation. (Ma, 2003)

Fig. 21 Aftermath of the Denunciation Rally

Fig. 22 Full Shot of the Hall

If Farewell still to a certain extent places an aesthetic distance between the audience and the traumatic memory in its highly stylised and symbolic portrayal. Blue has utilised a more relatable site of the family as the microcosm of historical crisis and is imbued with a sober, critical and reflexive historical consciousness. In depicting how the family, everyday pleasure, marriage, and mundane daily living are steadily ravaged by historical events, it features how normal spaces become abnormal and how abnormal spaces are created.

For example, The condemnation of Shaolong, Tietou's father, as a rightist in the library is one of the most absurd episodes of the film. Tian shot the scene with a tension-ridden mise-en-scene with psychic depth and through unusual shooting angles. During the meeting which has to select one more rightist to fulfil the quota, as Shaolong comes back from the men's room, the door's narrow opening reveals rows of heads at both sides of the long table with all eyes staring at him, the toilet still flushing in an unnerving sound(Fig. 23) The meeting room, previously shot from the perspective of the head librarian is now seen from the narrative position of Lin. The opposite shooting angle presents the previously familiar space as something now beyond one's immediate comprehension as the situation remains a poignant mystery for both the viewer and Shaolong - He has indeed been condemned as a rightist. In the film, Tian constantly utilises such familiar, everyday space to amplify the haphazard and random nature of history. The absurdity of history consists in the futility of asking why me (Wang, 2009) - beneath the blinding, unending political storms, the desire for survival and decent mundane existence is only constantly disrupted, truncated and aborted.

While the public space for the adults is often portrayed with coldness and solemnity, that of the younger generation seemed far more fanatic and chaotic. Remaining in a sort of political naivete, they express their control of power through the occupation and destruction of spaces - swamping the campus with bigcharacter posters, climbing up to higher grounds and breaking the classroom windows. (Fig. 24) Through

Fig. 23 Library Scene

the inclusion of such spaces, the film refrains from locating the source of political victimisation as the teens portrayed are often simultaneously victims, witnesses and prosecutors of the event. In the close-up shots of the crowd where one does not have a superior perception, there is not only a sense of sustained bewilderment at the incomprehensible, mysterious happenings but also indifference and spontaneity in giving in to the omnipresence of the political power. It is perhaps pointing to the deeper origin of the event where neither the collective nor the individual is spared from the weight and responsibility of the trauma.

The public spaces in Blue and Farewell - whether ordinary or aestheticised, flamboyant or modest - emerge as memory structures for more specific audience involvement and positioning beyond the generic fabric of the street. While ordinary and modest everyday spaces in Blue provide a critical lens on the arbitrary and absurd stupidities of political dogma, the aestheticised, theatrical and symbolic spaces offer an emotional catharsis in portraying how the psyche is damaged and the culture's sense of continuity damaged. The full range of their possible significations, both particular and universal, referential and introspective, make them sites of memory that emerge to fill the vacuum of a past marked by contingency and senselessness.

Fig. 24 School Scenes

4.3. Private Space of Submission and Resistance

The Cultural Revolution is collective national trauma, but individuals are the ultimate bearer of the memory. It is not that collective experience does not count, but rather that the collective experience at its traumatic core takes the form of individual memory (Wang, 1999) Private spaces are often the ones that attend to the unhealed wounds, unsolved mysteries and unresolved tensions in the individual's relationship to history. As private memory remains obstinately testimonial which can hardly be reduced to a formula, the portrayal of private spaces in the film provides rich interpretative potential in reading such private, unsettled, unabsorbed experiences.

For Blue, the chronicles of the withering family and social life, and failed attempts to sustain a family are reflected in the treatment of the private homes. The film started with the scene of the newly-wed couple moving into their courtyard house (siheyuan,四合院) - recalling the blue and grey Mao suits worn by Chinese people at the time, the spaces are also dominated by hues of dark blue and grey(Fig. 25). As the act of moving in often carries a great sense of hope, of embarking on a new life, this courtyard house has indeed registered many moments of tenderness and joy. The special courtyard structure provides a communal space where kids in the neighbourhood play games such as throwing small beanbags, hopscotch, spinning gyro and lighting up fireworks (Fig. 26). The inward-facing arrangement of the households surrounding the courtyard forges a warm communal togetherness in these semi-private spaces where people hang their clothes, brush their teeth, took wedding pictures and go around to share dumplings on New Year's Eve. (Fig. 27) The threshold alleyway between the street and the courtyard is the favourable spot where the elderly and adults carry out their daily chores besides the staircase while keeping an eye on the kids(Fig. 28).

Fig. 25 Moving in

However, such modest structures of pleasures and happiness are only too transient and fragile as the family vicissitudes unfold. The house is ultimately abandoned after 'uncle', Shujuan's second husband dies. As landlord lady Lan walks into the deserted room, the photography moves from a close-up shot of the chaotic ground to a high angle full shot of the room. (Fig. 29) The frozen frame here recapitulates an empty, barren upper half of the room that finishes the narrative circle by returning to its original state, as well as a dirty and messy bottom half with the waste as a reminder of all the senseless suffering. Lady Lan stands in the middle as she picks up the red cloth Shujuan used for her marriage. Not only did the scene foreshadow the upcoming misfortune for Lady Lan, it also symbolises the state of the group of characters: they are neither those that exist beyond the political sphere (elderly and kids) nor those who exist as organs of a nebulous power machine, they are the ones caught in between - who live in a dangerous world yet fail to find a way out of it. Towards the end of the film, Tietou comes back to the courtyard house only to discover that Lady 31

Fig. 26 the Courtyard as the Kid’s Playground

Fig. 27 the Courtyard for Neighbourhood Interactions

Fig. 28 the Threshold Area

Lan's house has been expropriated by the neighbourhood committee while his own home is taken up by a new family; Lady Lan, condemned as the landlord class, has been banished to her hometown (Fig. 30) The loss of previously established connections to the space reflects the collapse of the family and communal structure. What lasts is only the continual sense of disorientation and uprootedness in confrontation with the traumatic shocks.

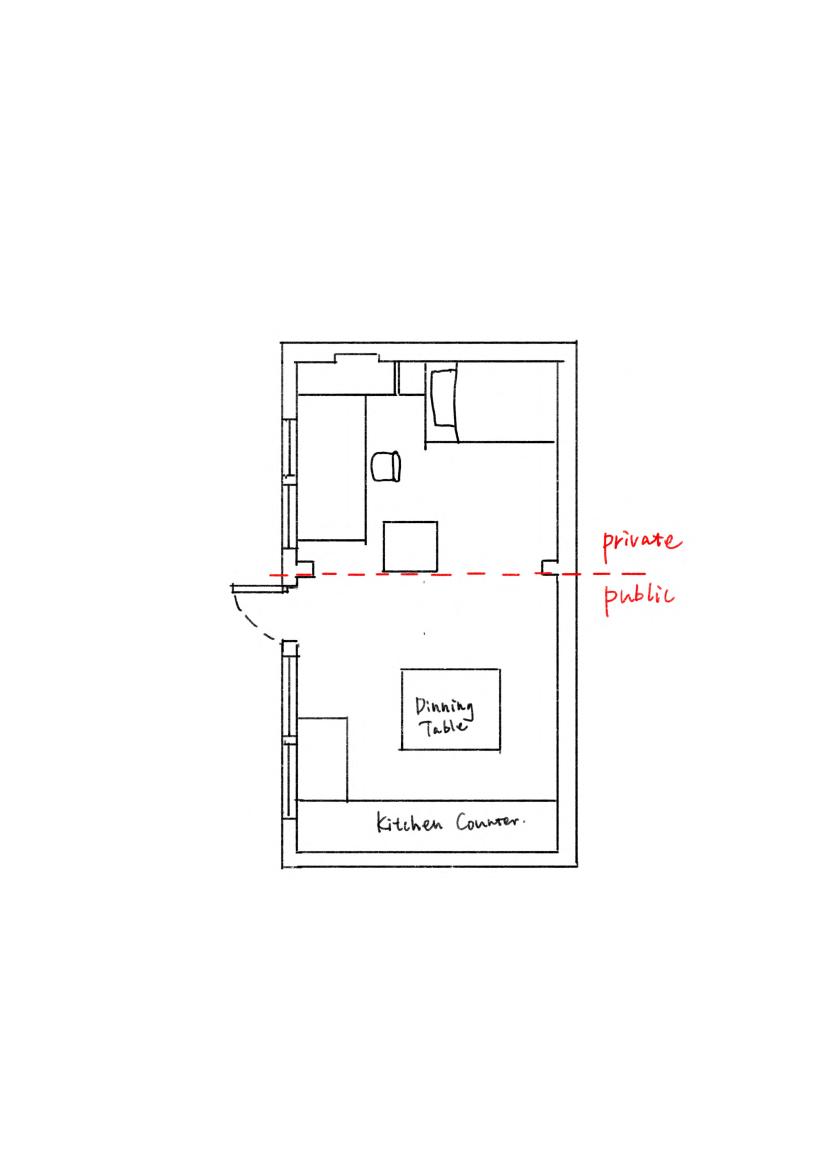

In the film, erosion of political agenda into the private personal life is also read through the spatial semiotics of interior decorations. The two-bay room is divided into a more public part where they dine and receive guests, more private part where the family rest (Fig. 31) There is an increasing degree of erosion by the party semiotics moving from the former to the later, such as the personal items in the niche being replaced by the sculpture of Mao(Fig. 32). Not only is this recalls the reality at the time when the exhibition of such semiotic items becomes almost a prerequisite in demonstrating one's political synchrony with the party ideology; it also symbolises the gradual corrosion of the public into the private. State propaganda and rhetoric of class struggle permeate the domestic space, demanding to be internalised by the individual.

Fig. 29 the Deserted Room

Fig. 30 Peaking Into the Expropriated House

Interpreting party policy and political message is a constant necessity for survival (Wang, 1999), as posters in the family are changed in accord with the ideology of different party movements(Figure 33). As the film reaches its climax where Tietou's stepfather was carried out of the house by the red guards for a denunciation rally, big-character posters (dazibao, ⼤字报) have completely carpeted both the interior and exterior of the once peaceful and tranquil home(Figure 34). While evoking the common experiences of many homes being completely vandalised during the Great Leap Forward period, the overwhelming spatial semiotics in the scene also represent the sweeping and relentless force of the Cultural Revolution that has completely acquired the private into the public sphere, thus reenacting the memory on both symbolic and physical level.

Fig. 32 Contrasting Room Interior

Beyond representing the space as the inscribed surface of sociohistorical processes, an allegory of the human body that is torn between family demands and social obligation moulded by different regimes, the film also unveils that the split goes beyond the personal to the interpersonal. There are repeated scenes of character interactions with the propaganda poster, banner or the Mao sculpture placed in between(Fig. 35). Such mise-en-scene hints that the invasion of totalising discourse often creates estrangement and distance among people, either separated by unpredictable destinies or different political inclinations. Alienation can arise within the closest family - in the film grandma's house was represented mostly as a remaining refuge for the young, a transcendental home to return to (Zhang, 2003). However, as the family gets together for family dinner after each blow it endures, there are decreasing family members and increasing fear(Fig. 36).

While the practice of dining together in the eastern culture often signifies family bonds, dinner around the table is gradually more poisoned by news of victimisation and campaigns. The photography and the spatial relation of the characters also moves from one that emphasise on the constellation to one that reveals the interrelation disconnection.

Fig. 33 Changing Posters That Respond to Different Revolutionary Movement

Fig. 34 Dazibao in the Interior and Exterior

In terms of camera language, the long shots and long takes add to the film's visual slowness which elevates the sense of everydayness to a level of great immersion and relatability. The slowness of the film lies not in its narrative tempo but its photographic suspension and expansion of temporality. (Zhang, 2003) This stillness allows it to become 'the uncanny tomb of our memory' (Sturken, 1997) that awaits metaphysical contemplation. The space under such cinematic language becomes a residue that preserves the very complexity, tension and contradiction of memory that politics is threatening to iron out and gives rise to a grainier, more truthful picture of the past at a standstill.

In contrast to the almost deliberate blandness of domestic spaces in Blue, such spaces in Farewell continue to be shot with a stylistic mannerism. One of the most heart-wrenching scenes in Farewell was the suicide of Juxian at her home after the denunciation rally. The room was shot from the same angle in two scenes previously - one is on their wedding night and another is on the eve of the Cultural Revolution (Fig. 37). Ash from the burning of the 'four olds' scattered the ground, the wine and food on the table were left untidied, and the candles in front of the bedside mirror were lit again like they were on the wedding night. Only this time Juxian's body was hanging on the beam, wearing her red wedding gown. The camera then quickly cut into the close-up shots of the candle, her embroidered wedding shoe, and the wedding photo. (Fig. 38) The candlelight reflected through the glass of the photo frame symbolises the volatility of human connection and the collapse of their marriage. The first two scenes of the home are shot at night, and are

Fig. 35 Party Semiotics Placed Between People

Fig. 36 Dining Scenes in Grandma’s House

filled up with a warm, red tone. The former coming from that of the celebratory items of the wedding nightthe red here represents good fortune, auspiciousness and prosperous family life as Juxian has hoped for. The latter is lit by the burning of the four olds - the red has with it an ominous character and foreshadows the upcoming doom and bloodshed. In contrast to these two warm-tone scenes, the suicide scene is shot during the day and has a dark, cold and grey tone. Amidst such background what stands out are the red candlelight, red wedding shoe and the red wedding gown. The fragments of red here are a powerful irony that while recalling the faith Juxian had for the family makes the eventual sacrifice and bloodshed more agonizing.

For both Farewell and Blue, personal spaces are the site for latent content of grand narrative to come into being. Through the destiny of the space and the individual occupying it, the exhausted capitals of past generations' collective memory anchor and condense. The spaces embody not only the innocent, the constant and the irreducible of personal life, but also the overcoded world of ideology and irrational excess of the collective madness. They are a womb of nature where the grand and the heroic leads are to be resisted by the truths of ordinary life, and through this resistance to be remembered.

Fig. 37 Interior shots of Xiaolou’s Home: Wedding - Burning of Four Olds - Juxian’s Suicide

Fig. 38 Close-Up Shots of Juxian’s Items

4.4 the Holistic Mnemonic System and Memory Landscape

Previous parts of this research examine spaces as spatial fragments through which memory is reproduced and reclaimed. However, these spatial fragments are not self-contained discrete pieces but rather part of a holistic mnemonic system embedded in the phantasmagorical memory landscape. Memory emerged from both the sites and the flow of movement between them.

The immersive everydayness that marked the memory landscape in Blue is registered in its spatial mnemonic system. For example, Figure 39 covers the period when Shaolong was first condemned as the rightest to his death after being sent to the countryside for Reform through Labour. Blue offers a sweeping epic with many leaps and blanks yet gives the impression of a slow tempo, which can be attributed to the 'syntax' of cinema - editing of space and time in the film. Tian favoured long takes and was very reserved in terms of changing shots within each scene. The continuity of time is usually maintained within each space which gives the film almost an impression of a stage play. The change of space is the main signal of jumps in the timeline, which can easily oscillate into ruptures in the evolving memory landscape if the time-space continuity is lost - an issue that is dealt with sensitively in the spatial mnemonic system of Blue

Firstly, there are strong cause-effect associations between spaces. Scenes of public spaces are often followed by a private one that illustrates the blow on the family and another in the public featuring the consequence. For example, the departure of Shaolong is explained through the sequence of the library(cause) – Tietou's home(progression) – train station and faraway mountains(consequence). The repetition of spaces across the timeline establishes a contrast– for example, the scene of a distant indistinguishable wilderness first appears to signal that Shaolong has gone somewhere afar; and the next time a similar scene appeared after his death is informed. As the environment stays unchanged while the destiny of the characters has spiralled into uncertainty, the film heightens the sense of defenceless individuals in the confrontation of the irresistible historical catastrophe. Also notable is that Tian often edit scenes of street or threshold spaces before featuring the interior of the home. This helps to ground the scene by indicating temporal changes or proving the cue of starting sequence which ensures the embeddedness of the memory system throughout. Despite only fragments of clue to what happened is offered, the well-crafted balance in the succession of spatial fragments create an even, homogenous landscape that makes the memory voyage easily readable.

Fig.

Spatial Mnemonic System of Blue

Fig. 40

Spatial Mnemonic System of Farewell

Similarly, the dramatic intensities of memory are also reflected in the spatial-temporal assemblage of Farewell. Figure 4.2 covers the period from the start of the Cultural Revolution to the end of the film. Most spaces in Farewell contain one stand-alone event and hence are less associated with each other. This allows Chen to make use more of symbolic spaces unlike that of the everyday spaces in Blue, such as the movie theatre with a strong spotlight where Xiaolou was interrogated, and the dance practice room full of mirrors where Xiaosi was caught guilty by other red guards. These spaces are usually sufficiently visually and symbolically simulating themselves and additional association with other spaces might only release the tension contained. Even when spaces are indeed associated, it is by less of a cause-effect relationship but more in terms of a temporal relationship based on character movement. For example, the first scene of Dieyi returning on the eve of the Cultural Revolution is followed by the scene of his arrival at Xiaolou's house – the two spaces, although disparate, are linked through an inferred continuous journey.

A more prominent example of such continuous geography is that of the climax sequence of the film that portrays the before - during - after phases of the denunciation rally of Dieyi and Xiaolou. Here the camera follows the two defamed opera stars across four spaces: the congregational hall, the street of public humiliation crusade, the Confucious Temple for the rally, and eventually Xiaolou's home where Juxian's committed suicide. The first two scenes feature an escalatingly dynamic camera movement in portraying the overall erratic atmosphere of the rally crowds while the latter two are largely static to give contemplation space over the climax events. The spaces in this sequence are connected through such a journey where their changing manifestation in the memory landscape works in accord with the rise and fall of the narrative.

Films are spectatorial means of transportation where the configuration of these sequences allow viewers to construct their own spatial ensemble in this voyage. The spatial mnemonic system of Blue and Farewell is composite geography where memory sites are connected through their associative power and in its creation of alchemy of inner senses form a consolidated and continuous memory landscape.

5. Conclusion

Blue and Farewell present a composite memory landscape: transit spaces of streets that through their capacity for metamorphosis demonstrate particular ways of being in touch with the environment and how that evolves with time and spatial coordinates; public spaces that provide a critical consciousness on the absurdities of various totalizing discourses and act as a constant reminder of the truth content under the excess of the grand and the heroic leads; as well as private spaces that register small people's innocence, unconscious resistance and inevitable misfortune and reveals the truth of ordinary life as it is. These spaces are interwoven into the mnemonic system of the film whose flow of movement constructs a continuous memory landscape.

Whether it is valorizing the intimate and the ordinary like the Blue, or portraying the psychoanalytical and the aesthetic like the Farewell, the spaces in the films directly confront the wounds as a sobering way of remembering the Cultural Revolutions. This research grounds itself in the awareness of the multiplicity of people, perspectives and processes that reconstruct the spatial representation of memory, as well as the subjectivity of myself as the interpreter with inherent idiosyncrasies and irreducible biases in reclaiming the memory. The limitation of this research also points to its possibilities. Spaces cannot be reduced to their essential traits as memory cannot arrive at their final meanings. As the films have established insert themselves into the public consciousness as a common point of reference of the Cultural Revolution, the memory sites within open themselves up for a mobile knowledge production of what is associated, what is possible and what is beyond. While this research proposes to use the Cultural Revolution as its historical frame of reference, its analysis is relevant to other contexts of traumatic knowledge transfer that can be understood as postmemory.

In the words of Edward Said(2000,p179), 'people now look to this refashioned memory… to give themselves a coherent identity, a national narrative, a place in the world'. Memory sites in films offer a form of ever-evolving postmemory that does not hasten to weal the wounds or prescribe a quick therapy. It revokes the self-congratulatory assumption that we are done with the trauma of the past and regard the search for roots as an ongoing practice of the present in an age of time-space compression.

Bibliography

Astrid Erll author (2011) Memory in culture / Astrid Erll ; translated by Sara B. Young. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. (Palgrave Macmillan memory studies).

Berry, C. (2004) Postsocialist Cinema in Post-Mao China: The Cultural Revolution after the Cultural Revolution. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203502471.

Bruno, G. (2007) Atlas of emotion: journeys in art, architecture, and film / Giuliana Bruno. New York: Verso. Caruth, C. (1995) Trauma: explorations in memory / edited with introductions by Cathy Caruth. Baltimore, MD. ; London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chen, K (2018) Public Class in Beijing Film Academy: Everything about Farewell my Concubine, 陈凯歌导演 北影公开课:关于《霸王别姬》的⼀切 含Q&A. Available at: https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show? id=2309404310694697795548 (Accessed: 17 March 2022).

Clark, P. (1989) ‘Reinventing China: The Fifth-Generation Filmmakers’, Modern Chinese Literature, 5(1), pp. 121–136.

CLEMENTS, M. (1994) ‘“The Blue Kite” Sails Beyond the Censors: “The Blue Kite” Sails Far Beyond the Chinese Censors’, New York Times, p. 42.

Cousins, M. (2009) ‘An interview with Tian Zhuangzhuang’, Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 3(3), pp. 249–258. doi:10.1386/jcc.3.3.249/7

‘Cultural Revolution’ (2015) in A Dictionary of World History. Oxford University Press. Available at: https:// www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199685691.001.0001/acref-9780199685691-e-979 (Accessed: 23 January 2022).

Ebert, R. (no date) Farewell My Concubine movie review (1993) | Roger Ebert, https://www.rogerebert.com/. Available at: https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/farewell-my-concubine-1993 (Accessed: 7 April 2022).

Farewell My Concubine (no date) Empire. Available at: https://www.empireonline.com/movies/reviews/ farewell-concubine-review/ (Accessed: 7 February 2022).

Feng, J. (2011a) ‘Teaching China’s Cultural Revolution through Film: Blue Kite as a Case Study’, ASIANetwork exchange, 18(2), pp. 46–61. doi:10.16995/ane.185.

Feng, J. (2011b) ‘Teaching China’s Cultural Revolution through Film: Blue Kite as a Case Study’, ASIANetwork exchange, 18(2), pp. 46–61. doi:10.16995/ane.185

François Penz editor and Richard Koeck editor (2017) Cinematic urban geographies / François Penz, Richard Koeck, editors. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan (Screening spaces). Available at: https:// cam.ldls.org.uk/vdc_100071135149.0x000001 (Accessed: 31 March 2022).

Geraldine Pratt and Rose Marie San Juan (2014) ‘Remembering to Forget to Remember: the Persistence of Memory and the Cinematic City’, in Film and Urban Space. Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.3366/ j.ctt1g0b5sc.8.

Giannetti, L.D. (2011) Understanding movies / Louis Giannetti. 12th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Hay, J. (2005) ‘Piecing together what remains of the cinematic city’, in The Cinematic City, pp. 211–231.

Hinson, H. (1994) ‘Movies: “Blue Kite”: Taking Mao Personally’, The Washington Post (1974-), 5 August, p. C2.

Hirsch, M. (2008) ‘The Generation of Postmemory’, Poetics Today, 29(1), pp. 103–128. doi:10.1215/03335372-2007-019

Hirsch, Marianne (2008) ‘The Generation of Postmemory’, Poetics today, 29(1), pp. 103–128. doi:10.1215/03335372-2007-019

Hoelscher, S. and Alderman, D.H. (2004) ‘Memory and place: geographies of a critical relationship’, Social & Cultural Geography, 5(3), pp. 347–355. doi:10.1080/1464936042000252769

Jacques Derrida author (1998) Archive fever: a Freudian impression / Jacques Derrida ; translated by Eric Prenowitz. Pbk. ed. 1998. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Religion and postmodernism).

Kracauer, S. (1997a) Theory of film: the redemption of physical reality / Siegfried Kracauer ; with an introduction by Miriam Bratu Hansen. Princeton: University Press.

Kracauer, S. (1997b) Theory of film: the redemption of physical reality / Siegfried Kracauer ; with an introduction by Miriam Bratu Hansen. Princeton: University Press.

Kraus, R. (2010) ‘14. Let A Hundred Flowers Blossom, Let A Hundred Schools Of Thought Contend’, Words and Their Stories, pp. 249–262.

Langer, L.L. (1991) Holocaust testimonies: the ruins of memory / Lawrence L. Langer. New Haven ; London: Yale University Press.

Lau, J.K.W. (1995) ‘“Farewell My Concubine”: History, Melodrama, and Ideology in Contemporary PanChinese Cinema’, Film Quarterly, 49(1), pp. 16–27. doi:10.2307/1213489

Lefebvre, H. (2001) The production of space / Henri Lefebvre ; translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lens: Lieux de Memoire · Lieux de Memoire Across the World · The Urban Imagination (no date). Available at: https://hum54-15.omeka.fas.harvard.edu/exhibits/show/lieux-de-memoire-across-the-wo/intro (Accessed: 23 January 2022).

Ma, N. (1990) ‘NEW CHINESE CINEMA: A CRITICAL ACCOUNT OF THE FIFTH GENERATION’, Cinéaste (New York, N.Y.), 17(3), pp. 32–35.

Ma, N. (2003) ‘Signs of angst and hope: history and melodrama in Chinese fifth-generation cinema’, Screen, 44(2), pp. 183–199. doi:10.1093/screen/44.2.183

Nora, P. (1989) ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, (26), pp. 7–24. doi:10.2307/2928520

Penz, F. (2012) ‘Towards an Urban Narrative Layers Approach to Decipher the Language of City Films’, CLCWeb : Comparative literature and culture, 14(3), pp. 13-. doi:10.7771/1481-4374.2041

Penz, F. (2017) Cinematic Aided Design: An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315722993.

Pratt, G. (2014) Film and Urban Space Critical Possibilities. Edinburgh: University Press.

Said, E.W. (2000) ‘Invention, Memory, and Place’, Critical inquiry, 26(2), pp. 175–192. doi:10.1086/448963

Sergei M Eisenstein, Yve-Alain Bois, and Michael Glenny (1989) ‘Montage and Architecture’, Assemblage, (10), pp. 111–131.

Sight and Sound (1994) ‘Lan Fengzheng/The Blue Kite’, 1 February, p. 55.

Sornoza, G. et al. (2018) ‘The case of China’s Economic Reform: The Xi Jinping Era, a comparative analysis with Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping’, Polo del Conocimiento, 3, p. 38. doi:10.23857/pc.v3i7.528

Stuart C Aitken, editor and Leo Zonn, editor (1994) Place, power, situation, and spectacle: a geography of film / edited by Stuart C. Aitken and Leo E. Zonn. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1994, ©1994.

Sturken, M. (1997) Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering.

Tschumi, B. (1994) The Manhattan transcripts / Bernard Tschumi. New ed. / prepared by Robert Young. London: Academy Editions.

Vogel, E.F. (2011) Deng Xiaoping and the transformation of China Ezra F. Vogel. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Walder, A.G. (2017) ‘The Chinese Cultural Revolution’, in Naimark, N., Pons, S., and Quinn-Judge, S. (eds) The Cambridge History of Communism: Volume 2: The Socialist Camp and World Power 1941–1960s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (The Cambridge History of Communism), pp. 220–242. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-history-of-communism/chinese-cultural-revolution/ 59E89C99F3890E1C85E5B0FCFD5E025B (Accessed: 23 February 2022).

Wang, B. (1999) ‘Trauma and History in Chinese Film: Reading “The Blue Kite” against Melodrama’, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 11(1), pp. 125–155.

Wong, S.M. (2012) The Cultural Revolution Narrative in Chinese Cinema: through Blue Kite(1993), Farewell my Concubine (1993) and To Live (1994)中国电影中的“⽂⾰”叙事 ——以《蓝⻛筝》(1993)、《霸王别 姬》(1993)、《活着》(1994)为视镜. other. Institute of Chinese Studies. Available at: http:// eprints.utar.edu.my/656/ (Accessed: 31 March 2022).

Wu. W. (1994) Geming xianchang: 1966 ⾰命现场:1966 (Revolutionary scenes: 1966). Taibei: Shibao wenhia

Yang, Ke, Y. and Zhang, D. (2010). 电影美术师杨占家作品集 / Dian ying mei shu shi Yang Zhanjia zuo pin ji. (The Art Director, portfolio of Yang Zhan Jia) 中国电影出版社, Beijing: China Filom Press

Zhang, X. (2003) ‘National trauma, global allegory: reconstruction of collective memory in Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Blue Kite’, Journal of Contemporary China, 12(37), pp. 623–638. doi:10.1080/1067056032000117678

Blue Kite, Directed by Tian Zhuangzhuang. China, Hong Kong, 1993

Farewell My Concubine, Directed by Chen Kaige, China, Hong Kong, 1993