MONT FLEUR CONVERSATIONS ON CONSTITUTIONALISM

2 – 6 December 2022

Mont Fleur, Stellenbosch

Edited by Nico Steytler

2 – 6 December 2022

Mont Fleur, Stellenbosch

Edited by Nico Steytler

Published by Dullah Omar Institute of Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape

© 2024 Dullah Omar Institute of Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape Designers: Nado Graphics

The support of South African Research Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation, through the South African Research Chair in Multilevel Government: Law and Development is hereby acknowledged.

CHAPTER

Lead-In: Patricia Popelier

Comment: Johanne Poirier

Comment: Eva Maria Belser

Comment: Zemelak Ayele

CHAPTER

Lead-In: Assefa Feseha

Comment: Yonatan Fessha

Comment: Curtly Stevens

CHAPTER

Lead-In: Nico Steytler & Jaap De Visser

Comment: Tinashe Chigwata

Comment: Zemelak Ayele

Comment: Thabile Chocho-Spambo

CHAPTER

Assefa Fiseha is the Director of the Centre of Excellence at Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

Eva Maria Belser is the Chair in Constitutional and Administrative Law, UNESCO Chair in Human Rights and Democracy, co-director of the Institute for Federalism, and Vice Dean of the Faculty of Law, Fribourg University, Switzerland.

Tinashe Chigwata is an associate professor and Head of the Multilevel Government Project at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Thabile Choncho-Spambo, a lecturer, is a doctoral researcher at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Jaap de Visser is the South African Research Chair in Multilevel Government, Law and Development. He was formerly the Director of the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Octávio Ferraz is a professor of law at King’s College London, United Kingdom.

Charles M Fombad is a professor of law and the Director of the Institute of International and Comparative Law in Africa, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Jeff King is a professor of law at University College London, United Kingdom.

Henk Kummeling is a professor of comparative constitutional law, and the Rector Magnificus Utrecht University, the Netherlands. He is also an extraordinary professor at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

John Mutakha Kangu is a senior lecturer at the School of Law, Moi University, Kenya.

Xavier Philippe is a professor of public law at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University, France, and an extraordinary professor at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Johanne Poirier is the Peter MacKell Chair in Federalism at the Faculty of Law, McGill University, Canada.

Patricia Popelier is a professor of law and Director of the Research Group of Government and Law, Faculty of Law, University of Antwerp, Belgium, and Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Federal Studies, University of Kent, United Kingdom.

Theunis Roux is a professor of law and Head of the School of Global and Public Law, University of New South Wales, Australia.

Curtly Stevens is a doctoral researcher at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Nico Steytler is a professor emeritus and former South African Chair in Multilevel Government, Law and Development at the Dullah Omar Institute for Constitutional Law, Governance and Human Rights, University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Asanga Welikala is a senior lecturer, Head of Public Law, and Director of the Edinburgh Centre for Constitutional Law at the School of Law, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Yonatan Fessha is a professor of law and the Research Chair in Constitutional Design for Divided Societies at the Faculty of Law, University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

Zemelak Ayele is an associate professor of the Centre of Federal and Governance Studies at Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, and an extraordinary associate professor at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa.

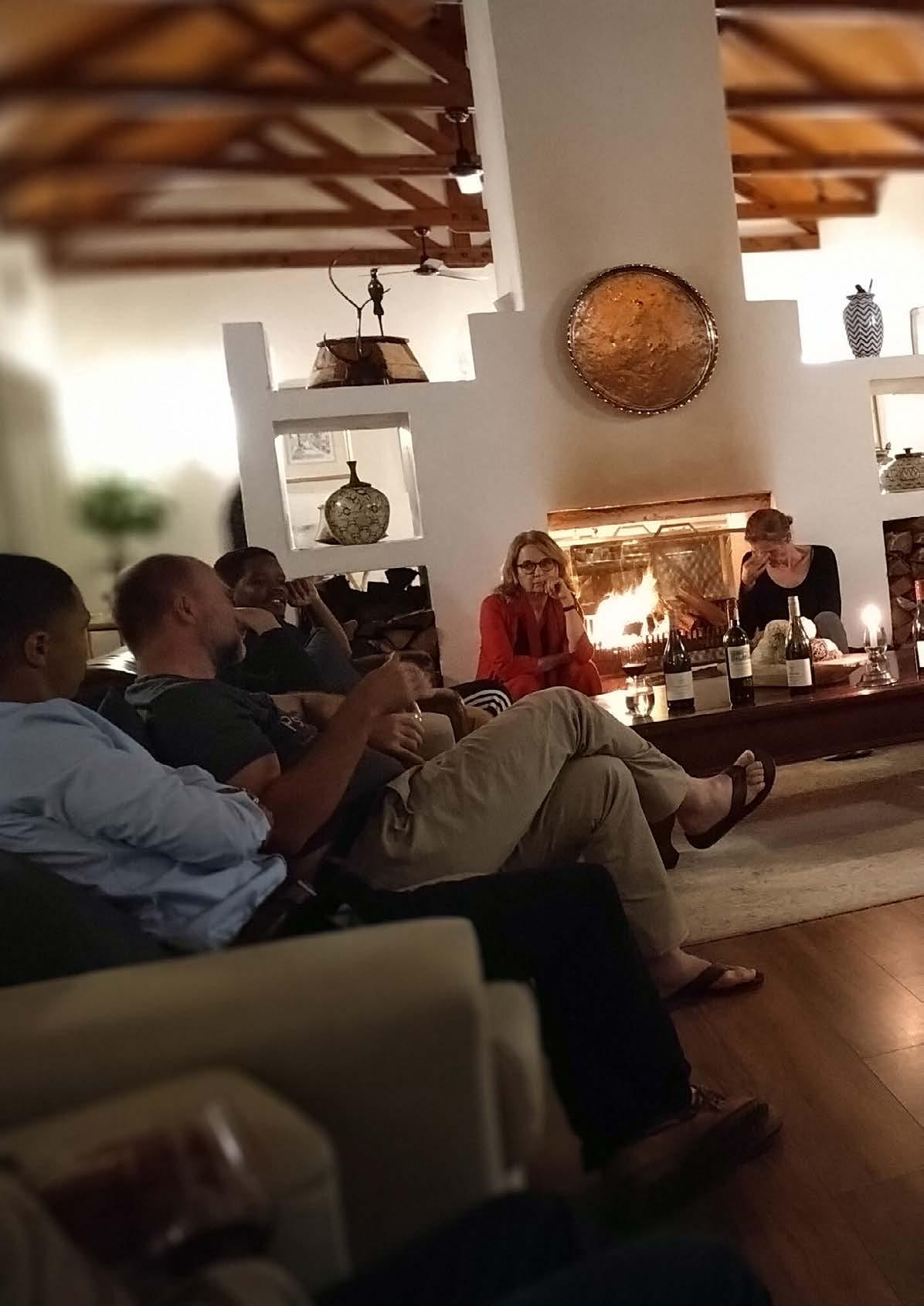

In December 2022, 19 constitutional law scholars gathered at Mont Fleur, a secluded conference venue nestled high against the Stellenbosch mountains, to discuss matters pertinent to constitutionalism and federalism. Unlike most conferences, the aim was not to follow the usual format of presenting papers followed by a Q&A, but to engage in conversations and ‘blue-sky’ thinking on the fundamentals of constitutionalism.

The participants all have a deep interest in the liberal concept of constitutionalism and its cousins – federalism and decentralisation. The aim of the conversations was to reflect on whether the orthodoxy in these fields is still (or has ever been) fit for purpose. In theory and practice, the concepts above have come under pressure and their validity, questioned. The conversations were an opportunity to do some blue-sky thinking on key issues that affect our work, as well as reflect on our concerns as political actors and individuals.

As no formal papers were to be delivered, the usual format of a volume of peer-reviewed conference papers was not envisaged. The written text prepared before and after the conference – the concept note, lead-in pieces, comments, and fireside stories – should not, however, be left unpublished. They contain analyses of complex issues conducted with clarity and erudition, some blue sky-thinking, and illuminating stories linking the scholar with constitutionalism. Unfortunately, the discussions - the nub of the event – could not be included

in this publication due to technical difficulties in transcribing the discussions.

This is hence an informal publication intended to document the event, with the focus both on conversations as a mode of academic discourse and on the key inputs that were made in regard to constitutionalism and federalism. Amply illustrated by photographs, the book seeks to do no more than capture an engaging, intellectually invigorating experience – and hopefully give rise to further conversations beyond its pages.

The conversations brought together primarily constitutional lawyers, who are not averse to dabbling in political science, and a sprinkling of political scientists with a foot firmly in constitutional law. They were persons with whom I have worked over the years in the fields of constitutional law, federalism, and decentralisation and local government. Many of them were also acquainted with other participants through common networks.

The participants ply their trade at universities, but also have a penchant for getting their hands dirty in the real world of governance and constitution-building through policy advice. A few young researchers also joined the group to enrich the discussions. Hailing from an array of countries and continents, the participants each have an enormous depth of knowledge and experience. What binds the group together is an interest in, and concern with, constitutionalism – in theory and practice – as a better way of governance than its alternatives.

The conversations were structured in two parts. First, given the challenges emerging from both the theory and practice of constitutionalism and federalism, what new thinking does this prompt? Is there an orthodoxy that needs to be challenged? How could we look innovatively at constitutionalism, democracy, separation of powers, human rights, the rule of law, federalism and decentralisation? Could we engage in some blue-sky thinking? This involves a group of people looking at problems and opportunities with fresh eyes; more ambitiously, blue-sky thinking is the activity of trying to find completely new ideas regardless of practical constraints. It is the proverbial thinking ‘outside of the box’. It may entail radical, visionary thinking that questions the very premises of orthodoxy.

Secondly, blue-sky ideas should also meet brown-earth realities. Indeed, the opposite of blue-sky thinking is down-to-earth, hardheaded, practical, pragmatic and realistic thinking. How may new ideas speak to current harsh realities? Are ideas for the future contextspecific to the different global regions of Asia, the Americas, Europe, and Africa? What avenues of research open up for pursuit when blue-sky ideas and brown-earth practice meet each other?

Debates about these issues are not new, but there has been a surge of interest in them across the world as the dominance of liberal constitutionalism has come under challenge in theory and practice. Our conversations sought to contribute to these debates.

The Mont Fleur Conversations and this publication would not have been possible without the support and engagements of a number of institutions and persons. The

National Research Foundation, through the South African Research Chair in Multi-level Government: Law and Development (SARChI Chair), provided the resources and space for such a gathering to take place.

The Mont Fleur Conference Venue was ideal for this venture. The management and staff excelled in providing an environment that was conducive for ‘blue sky’ thinking; they accommodated any request – whether a sundowner in the mountain or on Kogel Bay beach with its marauding baboon, discussions under an umbrella or two – with a smile and warmth.

The staff of the Dullah Omar Institute was at their usual best in the organization of the event and the production of this publication: Laura Wellen, Keathélia Davids, Kirsty Wakefield, and Sadieka Najaar. Particular mentioned should be made of Curtly Stevens, Johanne Poirier and I for all his organisational work.

The current SARChI Chair, Jaap de Visser, encouraged and supported this publication. I would also gratefully acknowledge the (volunteer) photographers who captured the spirit of the event admirably (and with whose permission the pictures are published): Keathélia Davids, Eva Maria Belser, Curtly Stevens. Thanks also goes to Andre Wiesner for his incisive editorial eye.

Finally, the success of the gathering (and this publication) must be attributed to the participants. Their enthusiasm, energy, and embracing a new format of academic engagement and willingness to share a fireside story, made it happen. Thank you!

Cape Town 2024

Nico Steytler

In the concept note to the conference the following background information was given on the substantive issues and the mode of engaging in conversations.

Liberal constitutionalism, with its elements of democracy, limited government and rule of law, has been the dominant governance discourse of the West, as well as of international organisations such as the United Nations (UN). Numerous organisations like these, including regional bodies and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), have, in a variety of ways, promoted constitutionalism as the better form of governance and one that leads to greater peace, stability and prosperity. Yet although many international organisations proclaim the universal desirablility of liberal constitutionalism, there are other modes of government, ones which, while not always articulated in coherent frameworks, challenge key notions of constitutionalism. The contention is that the centrality given to democracy, the limitations placed on government in societies of great inequality, and the shackles imposed by the rule of law, are standing in the way of stability, prosperity and more egalitarian societies.

The classic liberal democratic notion of constitutionalism is essentially one of limited government where at least three basic elements are enshrined in a constitution which is not readily amendable. The first is democracy – the establishment of accountable government in terms of both representative and participatory mechanisms. The second is limited government –entailing a separation of powers that provides checks and balances between the three branches of government – and an enforceable bill of rights. The third element is the rule of law – governance under rules and not by arbitrary discretion – which includes the supremacy of the constitution and its justiciability by an independent judiciary. The universalisation of this notion of constitutionalism as a normative framework for governance is evidenced by the many UN and regional instruments that exist, among them, for example, the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance of 2007.

Some scholars use the term ‘constitutionalism’ loosely as a descriptive device denoting any system of constitutional law and practice at all, no matter what base or ideology underpins it. In the literature, there are references to ‘Islamic constitutionalism’ and ‘authoritarian constitutionalism’. Some scholars have even added a fourth element to constitutionalism, ‘transformative constitutionalism’ – a commitment to achieving social justice by transforming society through constitutional means. Others criticise the concept as a relic of 19th century Diceyan thinking, one no longer fit for purpose in the 21st century and serving merely to legitimise a market economy.

For many in the West, the end of the Cold War signified the ultimate victory of constitutional democracy and the market economy. The impact was greatly felt in Africa and elsewhere in the Global South, where democratisation, with all the bells and whistles of constitutionalism, ended decades of dictators, military regimes, and imperial presidencies. Thirty years later, constitutionalism is in retreat, not only in the Global South but in many parts of the North.

Globally, many have commented on the regression in democratic governance and the resurgence of authoritarian rule with only partial regard for liberal constitutionalism. Alternative approaches to government are gaining voice. Authoritarian regimes are more confident in propounding a model of economic growth outside democratic governance and unrestrained by

the separation of powers or the rule of law. The ‘developmental state’ is idealised as the champion of the poor and campaigner for equality, with its legitimacy hinging on the economic prosperity it delivers. Populism and authoritarian rule are also on the rise in the West, including within East European countries which three decades ago opted for constitutionalism.

In Africa, the end of the Cold War saw the collapse of the non-democratic regimes that had been propped up by the two erstwhile superpowers; at the same time, it saw constitutionalism extolled as the hallmark of good governance and the free market as the road to prosperity. This second wave of democratisation came and went; now, 30 years later, the pockets of adherence are dwindling or precarious. Populist and authoritarian regimes are on the rise; alternative modes of governance have become attractive. In the face of the market’s failure to lead to prosperity (and, rather, to greater inequality), the developmental state as driver of the economy is becoming the preferred option, one that requires an unshackling from constitutionalism – which, of course, provides ideological cover for the new imperial presidencies.

The winds of change have also reached the southern tip of Africa. In post-apartheid South Africa, constitutionalism was presented as the glue that would hold the new nation together as it underwent transformation from a society based on racial oppression to one based on substantive equality. However, after nearly three decades, the constitutional glue is under close scrutiny because some argue that it keeps social and economic apartheid intact; what is advocated is that government play a greater role in undoing inequality in social and economic fields. The rule of law thus is fraying at the edges. Even the Constitutional Court, as the last bastion of constitutionalism, is under attack.

After almost 30 years, constitutionalism is at a crossroads. At the ANC’s five-yearly national conference in 16–20 December 2022, what was to be decided was not only the party’s leadership but the future of constitutionalism as a policy directive for government. The expectation was that Cyril Ramaphosa’s presidency would be challenged by a faction in the ANC that coalesced around anticonstitutionalism rhetoric. In the end, Ramaphosa was successful, but in the wake of the May 2024 national and provincial elections, the replacement of constitutional supremacy by parliamentary supremacy became the official policy of what is

now the country’s official opposition in Parliament.

Questioning constitutionalism’s orthodox components

A frequently raised question is whether the turn against constitutionalism globally is also a valid critique of the core elements of constitutionalism. Even in established liberal democracies, the efficacy of these element is under scrutiny.

Although democratic governance is a cornerstone of constitutionalism, we see a disenchantment with the practice of democracy. Ordinary people experience alienation from the political class, a class which appears to be there for no other reason than gaining economic advantage in increasingly unequal societies. Trust in the ability of parliaments (traditionally the great democratic institution) to hold the executive to account is low; instead, populism is seen as an effective response. In the Global South, an individualistic view of political engagement competes with a more communitarian worldview, with liberal assumptions about rational choice and one-person-one-vote being undercut by assertions of group identity. In the process, the slowness, the deliberateness, of democratic decision-making is forfeited in exchange for the quick decisiveness of powerful presidencies acting without restraint.

The separation of the three branches of government – legislature, executive and judiciary – has been a hallmark of limited government in that it entails a system of checks and balances between the three. This Montesquieuan view of government is premised on a balancing of powers in which no single branch dominates the others. The standard critique concerns the dominance by the executive of the legislature in terms of rules, but, equally importantly, due to single political party hegemony in both.

The poor account-holding performance of parliaments has been augmented by the ‘fourth branch’ of government – independent institutions protecting constitutional democracy, such as ombuds, human rights commissions, auditorsgeneral, and the like. The disdain for populist economics sees the emergence of constitutionally protected independent central banks mandated

to guard the health of their currencies. Questions about the democratic accountability of the fourth branch abound. More generally, the separateness of the four branches has become fuzzy; in populist and authoritarian regimes, power by definition has shifted to the executive, which in turn has decreased the powers of those institutions to whom it should account – parliament, the courts, and the ‘fourth branch’.

The expansion of constitutions in the 20th century to regulate the relationship between the state and its citizens through bills of rights is now a standard component of constitutionalism. The range of rights has increased, affording protection to groups such as women and gender, social, cultural and religious minorities. However, not only has there been backsliding on human rights commitments across the globe, but basic concepts in regard to rights have come under scrutiny.

The central constitutional commitment to equality has not prevented the growth of inequality in wealth distribution, where a minute proportion of the population owns an excessively disproportionate stake in the economy. The very notion of the rights of the individual – the pursuit by each of his or her own happiness – minimises social solidarity and the common good. In response, then, to the market’s failure to provide an effective distribution of a basic income and amenities, socio-economic rights have been earmarked to fill the gap. Some scholars argue that a fourth element should be added to constitutionalism: a transformative or developmental one, in which the goal is equal citizenship and it is pursued through, among other legal measures, enforceable socio-economic rights and substantive equality.

The question has also been raised of whether the rights discourse is the appropriate or most effective vehicle for addressing new global and national challenges such as global warming, automation and joblessness, and transnational market regulation.

Rule of law: Constitutional supremacy and judicial review

Constitutional supremacy and judicial review are seen as the final bastions of constitutionalism – as the place where theory meets practice. Judicial review is, however, varied in the West and challenged in the Global South. Where constitutions

are ambitious and aspirational (and where judicial review is indeed practised), the judiciary tends to wind up engaging with policy matters. The openendedness of socio-economic rights and judicial activism on this score has led to accusations that the courts are acting in breach of the separationof-powers doctrine. ‘Judicial adventurism’ has thus further strained the relationship between the courts and the other two branches of government, with the courts being accused of going beyond the constitutional interpretation of ambiguous text and instead ‘informally amending’ them by either ignoring the text or rewriting it.

The more independent the stance of the courts, the greater the populist claims that are made about their unaccountability to the people and contribution to the democratic deficit. Making the judiciary subservient to the executive becomes the inevitable goal; through various devices (including the appointment and dismissal of judges), judicial independence and impartiality are undermined.

Federalism brings all three elements of constitutionalism to the fore. Federal orthodoxy holds that each order of government is responsible to its respective electorate, something which, in the case of subnational governments, deepens democracy. Because the constitutional division of powers lies at the heart of a federal system, such division – in which each order is given final decision-making powers over range of policy fields – is itself a limitation on centralised governance and potential abuse of executive power. Moreover, since the division of powers and finances is complex and requires a rule-based system, functioning federations depend on the usual measures and methods characteristic of the rule of law.

Yet despite the longevity of various federations, federalism as a system of governance is in some cases under strain. In established federations, trends towards centralisation, particularly in populist and authoritarian contexts, are a common source of complaint. Here, the notion of shared rule becomes threadbare when the second house of parliament, designed to represent subnational governments or communities, does not function as intended but is yet another locus of power struggle between national political parties. Federalism is a system in which negotiation and compromise are the dominant method of making

decisions, but it is a method which is becoming the exception rather than the rule. How, then, is this system of governance able to deal with new international social and economic crises, such as global pandemics and climate change?

Despite such questions about the functionality of federal systems, federalism has become the last-resort solution for deeply divided countries, one in which, in multinational countries, the ethos is meant to trump the demos. However, in new federations formed to hold countries together and end conflict and civil war, the very basics of constitutionalism are, almost axiomatically, absent. There have thus been precious few countries where federalism has played its intended role: new federal attempts follow past failures with regularity. It is an inherently futile exercise, or are there different bases on which federal elements could be used to secure peace?

Decentralisation in the form of local governments is formally the outer edge of constitutionalism. Often, such governments are neither shielded by a modicum of constitutional protection, nor regarded as partners in intergovernmental relations, and operate instead in terms of rules

set by the central or higher-order subnational government, or both. Yet they are crucial to the vitality of constitutionalism, providing, as they do, the space for bottom-up democracy and serving to meet the basic needs of communities.

With mass urbanisation already completed in the North and now in progress in the Global South, cities are left to face major social and economic challenges. How do city governments integrate large sectors of inhabitants that feel alienated from mainstream politics? How can cities manage to be both the locus of economic development, on the one hand, and the site of poverty and stark inequality, on the other? How do cities cope with major environmental issues such as climate change?

With these tasks on the table, the call is for major cities to be constitutionally recognised players because they house the majority of the population, a population which also contributes the most to economic production. They want to be part of the intergovernmental structures that make decisions which affect them as well as the country as a whole.

The mode of interaction among participants was ‘conversation’ or dialogue. It was not the usual format in which individual papers are delivered and followed by Q&A and comments. Nor were the conversations free-for-all talking: they were loosely structured and guided by a moderator, with the lead-in speaker of a session being followed by a panel of commentators and, finally, open discussion.

Lead-in speakers each prepared a short text (of approximately 3,000 words) setting out the challenges and then the ideas that would ignite debate. Footnoting was optional. These texts were circulated among the participants two weeks before the conference.

A panel of commentators was allocated to each session topic. Each panelist prepared a one-pager (of 500 words) commenting on the lead-in piece of the session. The focus was on points of agreement, points of disagreement (matters of nuance), and issues that had been missed. The panelists gave their responses one week before the conference, thus formally beginning the conversations even prior to the gathering.

Each of the participants has vast experience in constitutional law, governance, and

constitutionalism. What the conference sought to explore through the conversations was how our work and intellectual engagement in governance and constitutionalism is grounded in our lived experience. The formal sessions thus flowed into fireside storytelling. After dinner each evening, participants were invited to join the relaxed, informal atmosphere of a fireside and share personal stories on the following: Why has our intellectual curiosity been captured by constitutionalism, federalism and decentralisation? How have our personal engagements with matters related to governance and constitutionalism influenced our thinking and actions? What lessons have we learnt from our experiences? Have such engagements influenced our intellectual pursuits? Overall, can a personal narrative form part of our intellectual inquiries?

Participants were later asked to squeeze their stories into a short essay (of at least 500 words), a request that most of them generously complied with.

Constitutionalism – of the liberal (and arguably,1 the only) sort – has seen better days. In the 30 years since its seeming triumph at the end of the Cold War, its stocks have fallen sharply. In the more multipolar world in which we find ourselves today, the idea that societies are best governed by written constitutions enforced by an independent judiciary is subject to at least four lines of critique.

First, there is the view that liberal constitutionalism’s juriscentrism has undermined the role of democratic legislatures and caused a host of other governance problems. This line of critique has a long history, dating back to debates in the United States from the 1960s over the so-called ‘counter-majoritarian difficulty’.2 But it is being pressed again now with renewed vigour, especially in the light of the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, 3 which constitutional-review sceptics have seized on as a vindication of their long-held views.

Secondly, there is the left critique of liberal constitutionalism, and especially its role in facilitating – or at least failing to prevent – the post-1980 rise in inequality. One key thinker here is Samuel Moyn,4 who has charged liberal constitutionalists with settling for a minimum floor of welfare provision rather than the rough equality of material wealth that their professed commitment to social justice requires. Another is Wendy Brown, whose reworking of Michel Foucault’s ideas on neoliberalism sweeps up liberal constitutionalism in its wake. Like the political constitutionalists’ complaint, this line of critique also has a long pedigree, going back at least as far as Karl Marx’s essay ‘On the Jewish Question’.

Thirdly, there is the ‘critique in action’ of populist governments around the world, but especially in Eastern Europe, as they have variously replaced or emasculated the liberal constitutions that were adopted after 1989. This line of critique has few scholarly defenders, in the English-speaking world at least, but erstwhile fans of liberal constitutionalism, like Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes, have decried what they now regard as the hubris of the post-1989 attempt to extend liberal constitutionalism to societies that lacked the political culture required to support it.

Finally, there is the emerging decolonial critique of liberal constitutionalism. This is particularly strong in countries like India and South Africa, whose constitutions were once thought to exemplify a new, progressive, style of ‘post-liberal’ or ‘transformative’ constitutionalism, but which are now being charged with adopting Western-style constitutions that prolonged the colonial past into the postcolonial present.

There are some overlaps between these critiques, and one might also question how novel and/or truly devastating they are. But my brief here is not to launch a defence of constitutionalism, but rather to lay out the critiques as fairly as I can and then to suggest some points for discussion. To that end, I start with a brief account of constitutionalism, so that it is clear what we are talking about, before moving to the four critiques and the issues arising from them.

To understand the critiques, we need to have some baseline understanding of what is being critiqued. That in itself presents an interesting challenge because there is no clear agreement on what constitutionalism means and whether there is just one or many varieties of it. The two poles on a continuum of views are occupied at the one end by Martin Loughlin, whose most recent book argues for a precise understanding of constitutionalism, and at the other end by scholars like Günter Frankenberg, Rosalind Dixon and David Landau, who accept the existence of many varieties of constitutionalism and even the phenomenon of ‘adjectival constitutionalism’.

Loughlin, for his part, is adamant that ‘constitutionalism’ must be understood in a very particular way, that is, as an ‘ideology’ about the nature and purposes of constitutional government that first started forming in the Philadelphia State House 250 years ago and has since gone on to conquer the world – with what he regards as malign consequences.5 The precondition for the emergence of this ideology, Loughlin contends, is the substitution of the original idea of constitutional government as being about the evolving political traditions of a people with the idea of constitutional government as requiring the adoption of a written constitution. With that, the ideology of constitutionalism was unleashed – a cluster of legitimating ideas which has progressively spread around the world to justify the central role played by the judiciary in enforcing the observance of fundamental political values. For Loughlin, as more fully elaborated in 3.1 below, this shift is deeply destructive of the original idea of ‘constitutional democracy’. He is insistent at the same time that there is only one hegemonic ideology of constitutionalism – the one that began in the US in 1787. All the other constitutionalisms, Loughlin argues – such as ‘popular’ or ‘authoritarian constitutionalism’ – are ‘misnomers … antithetical to the actual meaning of constitutionalism’.6

In stark contrast to this, Frankenberg prefers a much more open definition of constitutionalism as ‘a set of constitutional ideas and institutions mediating the establishment and exercise of power’.7 Frankenberg’s stated purpose in proposing this broad definition is to ‘prevent introducing the Western notion of constitutionalism in the guise of a universal understanding’.8 Having made that move, he proceeds to classify the various ‘varieties of constitutionalism’, from ‘political’ to ‘transformative’. Dixon and Landau in their

paper on ‘Adjectival Constitutionalism’ pursue a somewhat similar approach, although their purpose is different.9 For Dixon and Landau, the intriguing thing about the proliferation of different alleged types of constitutionalism is how they overlap and interact with each other. The authors are also interested in examining the ‘potential gap between constitutionalism as model and constitutionalism as discourse’.

I myself am inclined to think that Loughlin is right about there being a central idea of constitutionalism, but wrong in his depiction of it as a totalising ideology. To my mind, constitutionalism is intimately bound up with the liberal tradition of political thought in so far as all of its fundamental precepts – such as the rule of law and the separation of powers – are precepts that emanate from that tradition. The terms ‘liberal constitutionalism’ and ‘constitutionalism’ are thus synonymous in my view. But at the same time constitutionalism is a broad church capable of accommodating a wide variety of political ideologies, from US-style political conservatism on the right to German-style social democracy on the left. Liberal constitutions likewise come in different shapes and sizes, from the opentextured American variant to the highly detailed Indian variant.

What connects all these constitutions and justifies classifying them as belonging to a single tradition is that they are all organised around the same core concepts, including democracy, the rule of law, judicial independence, and the separation of powers. The reason, in turn, that constitutionalism is capable of accommodating such a wide variety of political ideologies is that the meaning of these core concepts is underspecified and ‘essentially contested’.10 This is true both internally within a single constitutionalist tradition (think of the contrasting liberal and conservative takes on the US Constitution’s founding ideals) and within the global tradition of constitutionalism as a whole (the characteristically American versus German versus Indian way of thinking about the relationship between these core concepts).

This is the feature of constitutionalism that is crucially lacking in Loughlin’s account. While constitutionalism may fairly be described as an ideology in so far as its core concepts function as a cluster of legitimating ideas, Loughlin’s depiction of it as a hegemonic discourse with fixed parameters ignores the contested nature of constitutionalism’s core concepts and the internal disagreement and regional variation that this produces. The essence of constitutionalism, which it gets from liberalism more generally, is

an aversion to dogmatic truths and an insistence that all knowledge is provisional and subject to revision in the light of experience.

This is true as much of constitutionalism’s core concepts as it is of its institutional prescriptions. To give one brief example, even so fundamental a doctrine as the separation of powers has over the last 20 years undergone considerable revision as constitutionalism has accommodated the idea of a fourth accountability branch of government. Far from being dogmatic truths (as this example illustrates), constitutionalism’s institutional prescriptions are revisable conjectures about what forms of governance are most apt to promote human flourishing in particular places at particular times.

Space precludes going into further detail on this point, so let me just list what I think are constitutionalism’s five main attributes: (1) its organisation around a series of deliberately underspecified and contestable political principles; (2) its experimentalism; (3) its capacity to be used to drive a particular kind of social change (i.e., one that presses down on its core principles to suggest the need for their reconceptualisation in the light of experience); (4) its inherently comparative nature; and (5) its claim to universalism.

political constitutionalist critique

The first line of critique, represented by Loughlin’s work (even though he himself rejects the label)11 is from the side of ‘political constitutionalism’. The term was coined by Richard Bellamy as a way of distinguishing the traditional British understanding of constitutionalism from the judge-led American variant.12 In so far as it questions the de-democratising effects of a constitutional system that gives judges the power to enforce fundamental political values, this line of critique also connects to the older American debate on the ‘counter-majoritarian difficulty’.13 Other contemporary scholars espousing variants of this critique are Mark Tushnet14 and Jeremy Waldron.15

This line of critique is, I am certain, very familiar to everyone, and thus I won’t elaborate on it here.16 The interesting contemporary phenomenon in any event is the way that proponents of the original American version of the critique, such as Tushnet, are today making common cause with

proponents of the British version, such as Loughlin. In the wake of the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, 17 Tushnet has written an adulatory review of Loughlin’s Against Constitutionalism18 in which he agrees with the central claim made in that book that judge-centred constitutionalism has had de-democratising effects.

In this way, in a curious bending-back arc of history, British scholars who can be read as arguing that constitutional democracy took a wrong turning in 1787 are making common cause with American scholars dismayed at the implosion of their country’s system of judicial review. I am no defender of the American system myself. My only complaint is that the triumphalism of these critics ignores the very different post-World War II conception of constitutionalism that emerged in Germany, India, and, more recently, South Africa. There is a tendency in this line of criticism to impute all the problems of the American system of judicial review to the tradition of constitutionalism as a whole. That, I think, is a serious error.

For the left, constitutionalism has from its very inception had an economic inequality problem – a vulnerability to the charge that its preference for stable, constitutionally limited government masks the unjust distribution of material resources. In his famous essay ‘On the Jewish Question’, Marx laid out the initial (and still, to some, attractive) basis for this critique.19 Rather than reconnecting man to his ‘species being’, Marx argued, the constitutions adopted in the United States and France at the end of the 18th century had merely effected a division between the ‘egoistic individual’ of civil society and the emancipated ‘citizen of the state’.20 Because the latter was subordinated to the former, the emancipation that these constitutions offered was not true ‘human emancipation’ but merely ‘political emancipation’. It was ‘man as bourgeois’, the economic actor in civil society, who was the real possessor of human rights.21 All that these constitutions had achieved, therefore, was to licence and legitimate the exploitation of the economically weak by the economically powerful, while simultaneously depriving the realm of politics of any effective means to do anything about it.

As the story is conventionally told, the rise of the welfare state over the course of the 20th century blunted this critique, with both Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Keynesian policies adopted in Europe after 1945 demonstrating that liberal

democracies were capable of mitigating the worst effects of free-market capitalism. As Thomas Piketty has shown,22 the period 1950–1980 was indeed associated with a reduction in economic inequality, as governments in Europe and North America used progressive taxation policies to redistribute the benefits of economic growth and fund expanded public health-care and education programmes. At least for a time then, liberal democracies appeared to be capable of reconciling their emphasis on political freedom with the demand for a just distribution of material resources.

From the 1980s, however, things began to change. For a range of reasons, both the Reagan administration in the United States and the conservative government of Margaret Thatcher in Britain began adopting policies that emphasised the value of GDP growth over economic equality. In part this had to do with the adoption of a more confrontational stance towards the Soviet Union, a stance that relied, inter alia, on these countries’ ability to outspend the latter militarily. Partly, also, the new approach had to do with the perceived exhaustion of the welfare-state model following a long period of economic stagnation in Britain and the natural, cyclical end of the New Deal regime in the US.

Whatever the exact precipitating factors, the new approach to governance drew on ideas that had been circulating in the US and Europe since the 1930s, but which, until then, had only been implemented in the Global South.23 Writing in 1978–79,24 on the cusp of the new era, Foucault identified two strands of thinking as being particularly influential: the ordo-liberalism of the Freiburg School in Germany and the neoliberalism of the Chicago School in the US (with the émigré Austrian economist, FA Hayek, the figure linking the two). Departing from Marx, Foucault saw these strands not as epiphenomenal to changes in the capitalist mode of production but as theoretical frames through which ‘the art of government’ was being deliberately re-thought. As they filtered into public policy debates in the 1970s, he argued, the two strands had coalesced into a distinct ‘governmental rationality’ – a new approach to governance based, inter alia, on challenging the traditional idea of labour as a factor of production.25 According to the new approach, individuals were no longer seen as ‘partner[s] of exchange’ but as ‘entrepreneurs’ of their own ‘human capital’.26 In consequence, neoliberal governance systems were capable of encompassing aspects of social life that

had hitherto been thought to be impervious to economic incentives.27 Indeed, entire policy sectors, like education and health, were now seen as governable according to market principles.28

Delivered as they were in 1978–79, Foucault’s lectures were ahead of their time, anticipating rather than examining the neoliberal policies that have since proliferated around the globe. In the contemporary literature, Wendy Brown is the scholar who has most explicitly built on Foucault’s ideas, extending his analysis to examine neoliberalism’s protean modern forms. In her first intervention on this topic,29 Brown focused on the impact of neoliberalism on democracy, and particularly the way that its technocratic prescriptions have infiltrated modern governance systems to displace traditional forms of democratic participation. In her second book,30 she developed this idea into a claim about the way that neoliberalism has not just undermined democracy but destroyed the social and political foundations that democratic societies require to function properly, at least on a liberal conception. Neoliberalism has achieved this, Brown argues, by collapsing the distinction between economy and society, on the one hand, and homo politicus and homo oeconomicus, on the other.31 Rather than subordinating the former to the latter, as Marx had said of the 18th -century liberal constitutions, neoliberalism has transformed the democratic citizens of liberal constitutionalism into market competitors in every aspect of their lives.32

The latter argument, in particular, is one that proponents of constitutionalism cannot afford to ignore. If Brown is correct, the fact that some liberal democracies are today waking up to the destructive impact of neoliberalism will make little difference. The assumption on which any proposed solution would need to be premised – the existence of informed, politically active citizens capable of controlling and limiting a distinct economic market – simply does not hold any more. With the destruction of the idea of a society independent of market relations and the supplanting of homo politicus by homo oeconomicus, the preconditions for the proper functioning of liberal constitutions are no longer (and never will again be) satisfied.33

A slightly different version of the contemporary left critique of liberal constitutionalism is associated with the work of Samuel Moyn. In his account of the human rights movement’s responsibility for the post-1980 rise in economic inequality, Moyn rejects the radical view, propounded by Susan Marks and others, that the movement provided

crucial legitimating cover for neoliberalism.34 But at the same time he does not think that it was entirely without blame. The correspondence between the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s and the ascendance of human rights as the most important political idiom through which to express moral outrage is too close, Moyn thinks, not to raise questions about the relationship between the two.35

The answer, however, needs to be nuanced. In particular, it needs to take account of the different ways the dynamics of this relationship were evolving in different regions of the world. When the communist states of Eastern Europe collapsed, Moyn notes, the human rights movement focused on the civil and political rights that had been central to the Western critique of state socialism, and on issues of transitional justice. While Eastern European countries did not delete the social rights that had been a feature of their communist constitutions, these rights were associated with that discredited ideology.[36] Thus, when neoliberal policies were introduced, there was no obvious moral vocabulary available to condemn their consequences.37 In Latin America, on the other hand, the reason for the human rights movement’s failure to respond to the economic effects of neoliberalism was somewhat different. There, the most significant factor was that neoliberalism had been introduced relatively early, in the 1970s, at the beginning of Augusto Pinochet’s authoritarian rule in Chile. The glaring violations of civil and political rights perpetrated by the Pinochet regime tended to distract attention away from the economic effects of its neoliberal policies.38

Despite these differences, Moyn argues, one central theme can be lifted out. As neoliberalism spread across the globe, the human rights movement chose to emphasise the value of sufficiency over material equality.39 Provided that basic needs were being met, growing disparities in economic wealth were tolerated. For neoliberals themselves, such disparities were the price that had to be paid for lifting people out of poverty. That, after all, had been the lesson of the Chinese economic miracle.40 For the human rights movement, this example was less compelling, but the end result was the same: neoliberal economic growth strategies escaped censure as long as they met basic needs.41 This was not just a moral mistake, Moyn thinks, but a strategic one as well.42 If there is a single cause of the resurgence of populism over the last 10 years, it is that gross economic disparities have cast doubt on the

credibility of the liberal political establishment’s claim to be concerned about human welfare.43 In failing to challenge the skewed distributional consequences of neoliberalism, the humans rights movement contributed to this cynicism, and thus to the declining prestige of the moral sensibility on which their work depends.

While the focus of Moyn’s account falls on the role of the human rights movement rather than national constitutional systems, his argument has obvious implications for proponents of liberal constitutionalism. If Moyn is correct that human rights, and social and economic rights in particular,44 have done little to challenge the distributional consequences of neoliberalism, liberal constitutionalists need to consider whether the suite of institutional mechanisms they have been proposing is sufficient, not just in absolute moral terms but also in pragmatic terms. All around the globe, liberal constitutions that coexist with stark disparities in wealth are losing public support. It matters not whether these constitutions are in fact responsible for economic inequality when populist leaders of both the left and right have proven themselves to be adept at damning liberal constitutionalism by association. If liberal constitutionalism is to survive this threat, its proponents need to devise ways in which it can be re-oriented to combat the problem of economic inequality. Of course, this problem may not be something that any one country acting on its own can resolve. If so, it may be beyond the reach of any single national constitution, liberal or otherwise. But that simply widens the frame of analysis rather than absolving liberal constitutionalists of the need to respond.

The right-wing populist critique

The third main line of critique is a ‘critique in action’ in the sense that it takes the form of the right-wing populist revolt against liberal constitutionalism that has been sweeping the globe since the second decade of this century. The countries and political leaders or parties typically associated with this critique are Turkey (Recep Tayyip Erdoğan), Brazil (Jair Bolsonaro), India (Narendra Modi), the United States (Donald Trump), and Poland (PiS). While there is now a huge liberal constitutionalist literature on the phenomenon of right-wing populism,45 there are few scholarly elaborations of the populist critique from the perspective of that critique, that is, most treatments of the phenomenon, in English at least, are by liberal constitutionalists decrying the emergence of populism and proposing ways to combat it.46

One of the rare exceptions to this rule is the work of Adam Czarnota, who has started to develop an account of the populist reaction against liberal constitutionalism from a non-liberal (as opposed to illiberal) perspective. With the case of his native Poland particularly in mind, Czarnota contests the reduction of constitutionalism to liberal constitutionalism, which he regards as a postWorld War II phenomenon.47 Constitutionalism, Czarnota argues, should rather be understood as operating on three levels: ‘as a legal principle of the internal superiority of the constitution’, as an ‘ideology’ that ‘stresses the function of the constitution as a normative and institutional safeguard against arbitrary use of power’, and as a ‘focus of systematic empirical and theoretical investigation’.48 When approaching constitutionalism in that way, Czarnota argues, it is ‘difficult not to see some merit in populist arguments that indeed democracy has been restricted, and constitutional narratives reduced or rather transformed by and into the legalformalistic language of legal constitutionalism’.49 In addition to the de-democratising effects of judge-centred constitutionalism, the two other main drivers of populism, Czarnota argues, are a reaction to globalisation’s impact on national identity and a frustration with liberal constitutionalism’s seeming lack of attention to inequality, not just economic but also inequality of political participation.50 In this way, Czarnota’s work joins up aspects of the first and second lines of critique as an explanation for, and partial justification of, the populist reaction against liberal constitutionalism.

A second recent publication worth noting is Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes’s searing critique of the folly of post-1989 liberal-constitutionalist expansion in Eastern Europe.51 Writing as disillusioned (chastened?) constitutionalists, Krastev and Holmes point particularly to the rapidity with which liberal constitutions were adopted across Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The main driver of this process, they argue, was not the upsurgence of a suppressed, autochthonous tradition of constitutionalism, but a desire to ‘imitate’ the political traditions of the West in the hope that this would secure rapid accession to the EU and the consequent transformation of these societies into normal liberal democracies. The folly of this line of thinking was to expect that mere imitation of the constitutional form of liberal democracy could stand in for the absence of a supportive political tradition. In most countries in Eastern Europe, they remind us, communism was

superimposed on exclusionary, illiberal political traditions. The mere stripping away of socialist legality, therefore, was insufficient to ground the new constitutions adopted.

The decolonial critique

The decolonial critique of liberal constitutionalism, while entangled in various ways with the left critique of economic inequality,52 pays particular attention to the cultural contingency of liberal constitutionalism’s core concepts, institutions, and values. At its simplest, the critique may be seen as an extrapolation of Marx’s argument about the false universalism of liberal human rights into a more general claim about liberal constitutionalism’s parochial origins in the European Enlightenment. Rather than a transcultural tradition of thinking about the conditions for human flourishing, the critique goes, liberal constitutionalism is simply the unilateral projection of a Western conception of good governance onto societies for whom that conception has little resonance or intrinsic significance.53 Worse, the unthinking promotion around the globe of this mode of governance perpetuates and legitimates the still unfinished project of Western cultural and economic imperialism.54

The beginnings of this critique can be traced to the post-World War II decolonisation process in Africa and Asia and the efforts at the time to establish a counter-hegemonic, Third World perspective on the liberal international order.55 While this initiative ran out of steam in the 1980s, the underlying ideas have flourished in academia, first in the form of postcolonial studies and latterly under the rubric of the Global South research agenda in the humanities and social sciences.56 Among legal academics, this agenda is now firmly established in the Third World Approach to International Law (TWAIL).57 Although a similar approach is taking a little longer to find a foothold in comparative constitutional law, there have been several important publications over the last few years, indicating that the decolonial critique is gaining momentum there, too.58

In its contemporary form, the decolonial critique of liberal constitutionalism is particularly prominent in India and South Africa. The simultaneous emergence of the critique in those two countries is not an arbitrary coincidence, but a function of the fact that their constitutions were long regarded as icons of a certain style of Southern democratic constitutionalism. The 1950 Indian Constitution was thus the first postcolonial constitution to emerge from a prolonged meditation, in the

Constituent Assembly process from 1946–1949, on how best to adapt liberal constitutionalism to the circumstances of the Global South.59 After the 1975–1977 Emergency, the Supreme Court’s legitimacy was restored on the back of its public interest litigation jurisprudence, which many saw as a vindication of constitutionalism’s ability to deliver meaningful remedies to the poor and the marginalised. The 1996 South African Constitution, drawing on this legacy, included a range of justiciable socio-economic rights, and in this instance, too, the Constitutional Court was initially praised for its sensitive handling of its mandate.60 Until about 2010 or so, it would have been hard for even the most determined opponents of these two constitutions to deny that they represented thoughtful, locally driven attempts to develop a meaningful form of democratic constitutionalism adapted to the challenges of the Global South.61

Just more than 10 years later, the situation has changed completely. In the more multipolar world of the 2020s, two constitutions that were once celebrated as triumphs of indigenous creativity are being portrayed as prime examples of epistemic silencing.62 Far from being authentic expressions of their respective people’s democratic will (so the decolonial critique goes), the Indian and South African Constitutions reflect the hegemonic hold of Western governance models at the time they were adopted. In India’s case, that was at the end of the Second World War, when the victory of the Allied forces had seemingly vindicated the superiority of liberal democracy. In South Africa, the Constitution was drafted at the zenith of Western geopolitical power following the collapse of the Soviet Union. In both instances, decolonial critics say, pro-Western political elites seized on this temporary shift to press for the adoption of what were essentially liberal constitutions. In so doing, they pulled off a confidence trick for the ages – successfully giving the appearance of creating homegrown constitutions while in fact entrenching the social and economic structures, and more importantly, the conceptual landscape, of colonialism.63 While arising in very different contexts, the Indian and South African versions of this decolonial critique have certain common features.

First, the premise of the decolonial critique in both countries is that the constitution in question is a liberal constitution.64 This point is significant since, on the orthodox view of what happened, it is not at all obvious that the Indian and South African Constitution should be classified in this way. For example, Karl Klare, whose reading of the 1996

South African Constitution has proven influential, is adamant that it should be understood as a ‘postliberal’ document.65 Likewise, commentators on the Indian Constitution differ about its status as a liberal constitution, with some coming down in favour of that view and others categorising it differently.66 This disagreement, of course, is partly about differing conceptions of the scope of the liberal-constitutionalist tradition. The more capacious your definition, the more likely you are to classify both constitutions as liberal. But it is still noteworthy that, for the Indian and South African constitutions’ decolonial critics, there is no room for doubt on this score: both are clearly classifiable as liberal constitutions, and that is in part why they are liable to decolonial critique.

The definitional move is in this sense essential to the critique but also a question-beginning aspect of the critique. ‘Essential’ because tarring the Indian and South African constitutions with the brush of liberal constitutionalism enables decolonial critics to channel a lot of the international dissatisfaction with that tradition, in both the Global South and Global North, into their critique. But ‘question-begging’ because, according to the orthodox narrative, the Indian and South African constitutions extended the liberal constitutionalist tradition beyond the West, decolonising it and addressing many of the traditional criticisms made of it. On this alternative view, merely labelling these constitutions as liberal does not settle the question of their coloniality.

The second point worth noting is that the decolonial critique is both an active feature of political discourse in India and South Africa and the subject of scholarly writing. These two versions of the critique are not unrelated, but this does not mean that they should be tendentiously equated with each other. As it figures in political discourse in India and South Africa, the decolonial critique is relatively easy to dismiss because it is being used in ways that critical left commentators would likely agree are troublesome. In India, the decolonial critique has thus been deployed to invoke the idea of an authentic indigenous people whose political preferences (about religious accommodation in particular) are being stifled by a Constitution made under the pernicious influence of Western ideas. In this form, the critique is part of an unapologetically illiberal political discourse aimed at the construction of a Hindu rashtra. It would be a simple enough matter to condemn the entire decolonial critique in India by association with this exclusionary political project. In South Africa, similarly, the critique is

being wielded in the hands of politicians deeply implicated in that country’s recent history of corruption and misgovernance. It is therefore easy to dismiss as populist political posturing. But that would again be simplistic and fail to grapple with the seriousness of the critique in its scholarly form.

The third and last point worth briefly emphasising is that the decolonial critique in both India and South Africa draws on the idea of ‘decoloniality’ as elaborated in the work of Aníbal Quijano,67 Boaventura de Sousa Santos,68 Walter Mignolo, and Catherine E Walsh.69 Spreading over the last two decades from its origins in Latin America, this idea, with its emphasis on the longue durée – the long-term impact of colonialism, not just in material but epistemic terms – has provided a renewed focus for postcolonial studies in the Global South, and the decolonial critique of the Indian and South African Constitutions in particular. That is likely because both of those countries went through what were meant to be transformative constitution-making moments, only to find themselves not as transformed as many would have hoped. In South Africa, the notion of ‘decoloniality’ has struck a particular chord with critical left scholars. In India, it has been explicitly drawn on in a major popular account written from an ethno-religious perspective.70 That difference is interesting and worth interrogating in its own right. But for now, the point is that the decolonial critique in both countries takes inspiration from this common source.

The fact that there are these shared features does not mean, of course, that the context for the critique inside the two countries is the same. The shared features just mentioned are interacting in complex ways with various domestic developments that are specific to each country. In India, the critique is associated with the rise of Hindu nationalism and the electoral success of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The BJP’s pathway to success has been founded in part on the dethroning of the previously dominant Congress Party, which is identified in the public mind with the religiously inclusive 1946–1949 constitutional settlement. But there is still a fair degree of public support for the Constitution as a symbol of Indian nationhood, along with various other reasons why a frontal assault on the Constitution is not currently in the BJP’s interests. There are also structural reasons why the critique in its specifically decolonial form (as opposed to postcolonial theory more generally) is not being pursued within academia. In that setting, the

decolonial critique is being driven mostly at the level of popular culture, by one very influential public commentator in particular.71

In South Africa, the domestic factors in play are somewhat different. They have less to do with the rise of ethno-nationalist populism and more to do with the implosion of the ANC’s credibility as the custodian of the national liberation project. Delegitimated by its association with rampant corruption and blamed for the underperformance of the South African economy, the ANC is starting to cede ground to a political party – the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) – that claims to be the intellectual heir to the Africanist strain in black liberation thought.72 As is the case in India, the 1996 Constitution is associated in this critique with the ANC’s long history of assimilationism – its origins as a movement for demanding the inclusion of black South Africans as full citizens in a postcolonial South African state. As that process of inclusion has foundered, the 1996 Constitution has become vulnerable to the charge that it has allowed for the co-optation of a small proportion of black South Africans into an essentially untransformed and still white-dominated society. Accordingly, what is required is a second transition –a ‘post-conquest’ constitution that will finally throw off the yoke of settler colonialism.73 In academia, this critique is being driven by a cadre of young, left-wing scholars who draw on a mix of Latin American decolonial theory, US critical race theory, and indigenous black consciousness writings.74 In its popular political version, the critique is mounted not only by the EFF, but also by ANC politicians keen to outflank the incumbent President, Cyril Ramaphosa, who has publicly identified himself as a constitutionalist.75

Arising from the above summary of the four lines of critique (in addition, of course, to any views on whether the fourfold classification makes sense and whether the discussion is fair to each), some questions are left for discussion.

• What are common features of the four critiques?

There are obviously some overlaps between the critiques. In all four, constitutionalism is identified with liberal constitutionalism, which is characterised as centralising the role of the judiciary in enforcing fundamental political values. All four find this to be de-democratising, with slightly different emphases in each case.

Does the confluence of the four critiques on this issue strengthen them?

• Do any of the critiques contradict each other?

While not necessarily contradictory, there are some tensions between the critiques. The political constitutionalist critique, for example, in criticising liberal/legal constitutionalism’s de-democratising effects, doesn’t really clarify how its own proposed alternative (political constitutionalism or ‘constitutional democracy’ in Loughlin’s vocabulary) would address the problems that the left critique and the decolonial critique identify. The political constitutionalist critique appears to be an immanent critique in that sense, i.e., it is internal to the tradition of Western constitutionalism.

• How novel are the critiques?

As noted in the discussion, there are earlier antecedents for all four lines of critique. We might want to discuss what is unchanged and what is new about each of the critiques. What are the contemporary phenomena that in some cases are giving a new inflection to old lines of critique?

• Are there any obvious problems with the critiques?

One of the issues worthy of pursuit is the way in which the seemingly progressive decolonial critique has been flipped in India in service of an exclusionary, ethno-nationalist agenda. In South Africa, too, at the political level at least, decolonial rhetoric is used in sometimes dubious ways to shore up an anti-poor agenda (if you think that keeping corrupt politicians in power is invariably anti-poor). What is it about the decolonial critique that renders it vulnerable to abuse in this way?

• Are the critiques theoretically rather than empirically driven?

Another question we might want to pursue is the extent to which all of the critiques are theoretically rather than empirically driven. Is liberal constitutionalism really causing the problems that are identified, or are there other confounding variables?

The concept of constitutionalism derives from the concept of a constitution or constitutional law, which is partly defined as the law that seeks to organise and manage the state and/or state power, or organise and manage state governance and/or state government. Constitutionalism thus comprises the qualities and values that go into organising and managing the state and/or state power, as well as state governance and/or state governments, in a manner which ensures that state power and state governments are organised, managed and/or used to achieve the objectives for which they were introduced.

From this perspective, the state and state power – and state governance and state governments –are viewed as institutions which were introduced by human beings as they sought to organise themselves into political societies that aimed to enable them to survive and preserve themselves, since this is the ultimate objective of human life. Survival and self-preservation are what Theunis refers to in his presentation as ‘human flourishing’.

Given that human survival and preservation are highly dependent upon access to resources, these institutions must be seen as having been introduced partly as means of economic management and development of resources to generate more and equitable distribution to ensure the survival and preservation of all. From this perspective, some of the criticisms of constitutionalism discussed by Theunis must be seen as lamentations about the failure of constitutionalism to deliver on the objectives of these political institutions and the ultimate objective of human survival and self-preservation.

The objective/purposes of constitutionalism

Recognising the selfish nature of human beings and the corruptive nature of power that tends towards its abuse or misuse for personal benefit of those in power, the objective of constitutionalism is to institute mechanisms for the organisation and management of state power and state government to ensure adequate control and limitation of state power and/or state governments to achieve the aims of these institutions. Democracy, separation of powers,

checks and balances, the rule of law, and judicial review as elements of constitutionalism must thus be perceived as organisational and management mechanisms for control and limitation of state power.

The distinction and nexus between the theory of constitutionalism and its architecture and design

In seeking to understand the critics of constitutionalism, one needs to recognise that there is both a distinction and nexus between the theory of constitutionalism and the architecture and design of constitutionalism. This therefore calls for not only a proper understanding and conceptualisation of the theory of constitutionalism and all its elements, but also for proper understanding and choice of the best architecture and design mechanisms to be able to deliver on the objectives, including of devolution.

The limitations in the architecture and design of constitutionalism

One of the limitations in the architecture and design of constitutionalism that illustrates how poor conceptualisation of constitutionalism and its elements can lead to the inability of constitutionalism to deliver is the limited way in which orthodox constitutional scholarship conceptualises state power.

Often state power is conceptualised from a narrow institutional perspective that identifies only three aspects of state power – the legislative, executive, and judicial powers of the state. This normally fails to identify and recognise the two most important aspects of state power – the control of public finances or public expenditure, and the control of the state apparatus of force.

Constitution-making based on this narrow conceptualisation fails to create adequate checks and balances. Too much focus is placed on the separation of the legislative, executive, and judicial powers of the state, while very little is done about the control and limitation of the financial power of the state as well as the state apparatus of force.

These two often slide into the ambit of control by the executive power of the state, thus compromising checks and balances. Sometimes

the legislature becomes subservient to the executive due the fact that the executive controls the allocation of funds to it. Similarly, the judiciary may become subservient to the executive which controls the allocation of funds to it. In addition, the judiciary may render judgments and issue orders against the executive that end up not being enforced because the executive controls the state apparatus of force (such as the military, the police, and the intelligence services), elements of which may be required to enforce court orders.

Even federal or devolved systems of government sometimes fail to deliver on their promises on constitutionalism due to the fact that the financial system is designed in a manner that enables the executive of the national sphere of government to control the financial power of the state.

The challenges that constitutionalism faces

As we reflect on constitutionalism and its critics as discussed by Theunis, we need to start thinking critically about constitutionalism in the light of emerging challenges to it. I will single out two such challenges for discussion.

First, there is the challenge arising out of the inability of constitutionalism to midwife itself. Many of the critics of constitutionalism seem to complain that constitutionalism has been unable to transform society. For example, the decolonial critic of constitutionalism, the critic of transformative constitutionalism, the critic of constitutionalism in Eastern European countries, and the critic of constitutionalism in India and South Africa all seem to be lamenting the failure of constitutionalism to transform their respective societies. This raises the question of whether constitutionalism as a concept has failed, or whether it is the architecture and design of

the constitution which failed to provide for constitutionalism to be midwifed into meaningful operation.

Constitutions and constitutionalism might not be able to propel themselves. Constitution-makers must thus provide for the management of the transition of autocratic systems into systems that respect constitutionalism. Constitutions must provide for how the old order will be deconstructed and the new one enabled to take root. In many places, a lot of effort is put into the making of the new constitution, often with people from outside the old order taking control. However, once the new constitution is made, it is left to the old order and people from it, or people who have vested interests in the old order, to implement the new constitution. The old order is allowed a very critical role in midwifing the new order. Often the old order becomes reluctant to deconstruct itself and facilitate the construction of the new order. The old order resorts to business as usual or constructs the new order in its own image.

Secondly, there is the challenge that arises out of the nature of global life. Constitutionalism seems to have been conceptualised as a mechanism of control and limitation of state power confined in national states. However, modern life is now subject to very many factors and decisions that fall, and are made, outside the state. Many decisions that affect citizens of national states in fundamental ways are today made by multinationals that might not fall under the governance and control of national states and governments. This then poses serious challenges to constitutionalism as originally conceived. In an era of free markets, international markets wield far more power than national states are able to control and limit through constitutionalism.

I have always seen constitutionalism as a fairly neutral term. It organises limited government in terms of preconditions, such as separation of powers, checks and balances, and fundamental rights. All of this is laid down in a written or unwritten constitution. Constitutionalism has no agenda and sets no agenda except a very limited negative one, namely the prevention of tyranny and arbitrary exercise of power.

Theunis Roux’s lead-in has raised serious questions for me (in my perception of constitutionalism). All the criticisms he describes suggest that in fact there is an agenda. But is it really the case that constitutionalism inherently promotes a juristocracy, affirms inequality, and maintains colonial relations, let alone that it actively strives for this? For the time being, I think it is mainly political ideology and politicians that enable and

promote desirable and undesirable developments within the framework of constitutionalism. The fact that there are undesirable developments seems to have little to do with the concept of constitutionalism as such.

And then we come to a fundamental question: Could and should constitutionalism be put at the service of ‘progress thinking’? For example, could and should it make a more active contribution to eliminating social inequality and combating the consequences of climate change? In short, should constitutionalism be given an agenda? Some kind of ‘new constitutionalism’? Assuming this to be so, it would require much stricter socioeconomic and cultural norms and an even firmer enforceability of these norms.

But two things are certain. First of all (constitutional) lawyers cannot do this alone. The substantive criteria for these new constitutional norms would have to come largely from economists, climatologists, social scientists, etc. Secondly, such a development would not be possible without the help of politicians – those same politicians who, according to the critics in Theunis’s input, have not helped us particularly under the regime of ‘old constitutionalism’.

And that leads to my last question: Are constitutionalists willing to become activists, in the sense of entering or at least influencing the political arena in order to bring about the desired changes?

As a preliminary remark, I would like to stress how controversial these issues have been among scholars – rather than the constitution-maker community – who look at constitutionalism as a topic in itself (rather than an object!) and tear apart constitutional lawyers. It is seldom a quiet debate!