It is with great pride that I introduce the 13th edition of the eMagazine (Future Research) of the University of the Western Cape (UWC), dedicated to showcasing transformative research that speaks to the urgent imperatives of our time. This edition is thematically anchored in three interlinked Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

At a time when global poverty, food insecurity, and unsustainable consumption and production patterns continue to exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities and environmental degradation, it has become increasingly clear that higher education institutions must play a transformative role in shaping more just and sustainable societies. The 13th edition of the eMagazine (Future Research) offers a compelling window into how UWC is rising to that challenge.

More than a collection of research outputs, the contributions featured reflect the university’s deep and enduring commitment to engaged scholarship that is grounded in scientific rigour, ethical responsibility, and a bold vision for inclusive development. UWC researchers are at the forefront of exploring innovative solutions to some of the most pressing issues facing communities locally, nationally, and globally. Whether working in the fields of food security, climate justice, public health, education, or land reform, their work consistently bridges disciplinary boundaries and places social impact at its core. What sets UWC apart is its historical and ongoing dedication to research that not only generates new knowledge but also challenges entrenched systems of inequality and marginalisation. The university’s research culture is underpinned by a strong ethos of community engagement and public responsiveness. This means prioritising the needs, voices, and agency of the communities that are most affected by systemic injustices, and working collaboratively to co-create sustainable and contextually relevant solutions.

In line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), UWC values research that is purpose-driven, transformative, and rooted in a commitment to social and environmental justice. The projects and perspectives captured in this edition are a testament to that vision. They demonstrate how UWC scholars are not only contributing to academic excellence but also actively shaping pathways toward a more equitable and liveable future.

Leading this edition is the work of Professor Julian May and his team at the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE), based at UWC. Through the Walking with Communities project in Worcester (Western Cape), they are showing how research can make a real difference in people’s lives. By working closely with local communities, the team helps to identify the root causes of hunger and malnutrition and finds practical, locally relevant solutions. Instead of applying a top-down approach, the project focuses on partnerships and participation, combining community knowledge with scientific tools. This helps ensure that the solutions are effective, sustainable, and truly meet the needs of those affected. The initiative is a strong example of how research can support SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) in ways that are meaningful and lasting for South African communities.

From the Faculty of Law, Dr Rochiné (Melandri) Steenkamp is helping to shape a new vision of water justice that supports efforts to end poverty, hunger, and promote sustainable living (SDGs 1, 2 and 12). Her research looks at how laws and policies can improve access to water; protect the environment, and involve communities in making decisions about natural resources. She highlights the need for fair and inclusive legal systems that put people and the planet first. Working in a similar space, Professor Angela van der Berg focuses on urban climate justice. Her research explores how laws and good governance can help cities respond to climate change while using resources more responsibly. She argues that legal systems must support fair and sustainable development in cities, especially for vulnerable communities. Together, their work shows how the law can be a powerful tool to build a more just, sustainable, and resilient society.

The Faculty of Natural Sciences is driving important research in biotechnology and biodiversity that supports sustainable development. Professor Takalani Mulaudzi explores how traditional African crops, combined with modern biotechnology, can help fight hunger and improve resilience to climate change. Her work not only offers new scientific solutions but also brings value to traditional knowledge and farming practices that have long supported local communities. This research supports both food security and more responsible ways of producing and consuming food (SDGs 2 and 12).

Working in close alignment, Professor Adriaan Engelbrecht from the Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology highlights the power of community-based research in achieving sustainable outcomes for both people and the environment. His work focuses on how conservation efforts, when driven by and for communities, can strengthen food security while protecting biodiversity. By building strong local partnerships, his research promotes inclusive development that empowers communities to manage natural resources in ways that benefit both their livelihoods and ecosystems. This aligns strongly with SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), showing that scientific research, when rooted in collaboration, can be a driver of meaningful and lasting change. Together, Professors Mulaudzi and Engelbrecht demonstrate how science can support resilient, sustainable, and locally driven solutions to some of the most pressing challenges facing South Africa and the wider continent.

In the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, two researchers explore important issues affecting development in South Africa and Africa as a whole. Professor Mulugeta Dinbabo studies how climate change and migration are connected, especially in communities that are most vulnerable to poverty and displacement. His work helps us understand how these challenges affect progress towards ending poverty (SDG 1) and achieving sustainable development across borders.

At the same time, Dr Farai Mtero examines land reform in South Africa since apartheid. He looks at whether current land policies have helped reduce poverty and inequality, focusing on how fair and effective these reforms have been. His research is key to understanding how land access supports food security and long-term poverty reduction, linking directly to SDG 1 and SDG 2. Together, their research shows how important fair policies and good governance are for building stronger, fairer communities in Africa.

The research profiled in this edition underscores UWC’s deep-seated commitment to conducting scholarship that is not only globally relevant but locally engaged and socially responsive. Our researchers are not working in silos; they are working with communities, across disciplines, and in the spirit of co-creation to shape a more just, food-secure, and ecologically sustainable future.

May you be inspired by the depth of inquiry; the passion for social justice; and the innovative spirit that defines research at UWC. Let this edition stand as a testament to the university’s enduring role in driving transformation through research that matters.

Empowering communities through equitable access to land, water, and livelihoods

Building food security through innovation and local knowledge

Promoting sustainable, climate-smart, and inclusive practices

Meet our Meet our Researchers Researchers

Water Security, Justice and Environmental Law for Societal Change: Turning the Tide on Sustainable Development Goals 1, 2 and 12 at the University of the Western Cape

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW CENTRE FACULTY OF LAW

UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE

Her academic work at the Global Environmental Law Centre (GELC) at the University of the Western Cape contributes to the Centre’s mission of advancing interdisciplinary, justiceoriented legal research that responds to the complex environmental challenges of our time.

My research focuses on law and governance responses to water security in South African cities, exploring how legal systems can advance just and sustainable access to water in contexts marked by socioeconomic inequality, infrastructure collapse, weak governance, and climate variability.

Her work engages multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but speaks specifically to SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). A key component of my work engages the waterenergy-food (WEF) nexus, and the role of circular economy thinking in addressing South Africa’s service delivery crisis. I examine how water, as a socioeconomic and ecological good, can be more equitably governed through legal and policy reforms that integrate reuse, conservation, and environmental restoration. These interventions secure water, strengthen urban aquatic biodiversity and create inclusive green-work opportunities simultaneously.

Since water security is inseparable from South Africa’s decarbonisation trajectory, my work intersects with ongoing research on the just energy transition (JET). I examine the legal and governance challenges facing municipalities in supporting a low-carbon shift while safeguarding social justice. This includes engaging with the alignment of climate, environmental, and local

government mandates to ensure that energy access, procedural fairness, and environmental restoration are pursued together.

In teaching, spanning Environmental Law and LLM modules, I equip students to navigate the intersection of environmental rights and socioeconomic justice. We engage with statutes like the Climate Change Act 22 of 2024, and transformative judgments, such as Groundwork Trust v Minister of Environmental Affairs (Deadly Air), SAHRC v Msunduzi Local Municipality , and African Climate Alliance v Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy (#CancelCoal). These judgments underscore how litigation is increasingly being used to assert constitutional rights in the context of pollution, climate inaction, and state accountability. I also introduce students to the work of organisations such as Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment (SAFCEI), groundWork, the Philippi Horticultural Association, the Centre for Environmental Rights, Natural Justice, and the African Climate Alliance to name a few. These partnerships help connect legal analysis

to grassroots environmental justice struggles and real-world governance challenges.

Although her own work is research-focused, her support student-led advocacy and policy engagement, and regularly use my involvement in professional networks, particularly the Environmental Law Association of South Africa (ELA), to connect students with events, learning opportunities, and conversations that enrich their engagement with environmental law in practice.

At GELC, we believe in scholarship that is critical, responsive and transformative. My research contributes to our broader commitment to legal frameworks that uphold human dignity, ecological integrity and participatory governance, and that helps build more resilient, inclusive and just urban futures.

At the University of the Western Cape (UWC), our research philosophy is rooted in community engagement and social relevance. As a researcher in evolutionary biology and conservation, my work is increasingly intersecting with the realworld challenges highlighted by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—notably SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

socioeconomic foundation for many rural and peri-urban communities across South Africa.

Growing up in a peri-urban area outside of Cape Town, where 30 years ago, agricultural land was converted into residential areas. In our newly-built neighbourhood, we often played in the streams that ran through the area. We regularly encountered wildlife; birds, snakes, and rodents and knew exactly where to find mole snakes. Beyond this regular contact with nature, our parents understood the local environment well. My mother often spoke fondly of seasonal natural harvests and the medicinal use of plants from our surroundings. One such example was “Blou blommetjie salie” (blue sage, Salvia africana), which was used to treat colds and coughs, among other ailments.

That intimate connection with our environment shaped my appreciation for biodiversity; not only as a natural heritage but as a resource with immense potential to uplift communities. Today, much of that natural environment is gone, and our connection to it has largely been lost. This is especially concerning given that we live in one of the most biodiverse regions in the world; an asset that, if sustainably managed, holds the potential to alleviate poverty across society.

A core focus of our current research has been the identification, conservation, and sustainable use of indigenous plant and insect species that contribute to local food systems. Traditional knowledge

around indigenous plants and parasite control holds untapped potential for improving nutrition and promoting climate-resilient agriculture. By working closely with community stakeholders, particularly subsistence farmers and youth, we aim to document this knowledge and develop sustainable livestock production systems. This work contributes to reducing food insecurity (SDG 2) and generating livelihood opportunities (SDG 1), while simultaneously protecting ecological resources.

Our lab also collaborates with local schools and community organisations to promote responsible production practices. Through education and citizen science projects, we raise awareness about ecological footprints and parasite prevalence, addressing SDG 12. Community workshops and field-based learning have proven especially effective in linking scientific research to everyday practices, and in making the SDGs tangible and locally relevant.

At UWC, the emphasis on research for societal impact goes beyond publication outputs. It is about embedding scholarship within the lived realities of

our communities and co-producing knowledge that can inform both policy and grassroots action. In doing so, our work demonstrates that biodiversity conservation is not a luxury, but a necessity for social equity and sustainable development.

South Africa faces complex and interlinked challenges, from food insecurity to environmental degradation. It is through partnerships between academia, communities, and policymakers that we can truly make progress towards the global goals. It is with hope that, through our efforts, we will ensure a prosperous and equitable future for all in our country.

PROF ANGELA VAN DER BERG DIRECTOR: GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW CENTRE FACULTY OF LAW UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE

The interlinked crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, food insecurity, and persistent poverty demand new thinking on how law can shape just, sustainable, and resilient urban futures. Her research at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), conducted under the auspices of the Global Environmental Law Centre (GELC), engages critically with these intersections, examining how legal frameworks and governance processes can be reoriented to advance environmental and climate justice and sustainable development, particularly in the Global South.

Anchored in SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), my current work focuses on legal and institutional frameworks that enable more just and ecologically sustainable urban planning. A key strand of this research is the IMPACT Funded BiodiverCities project, which investigates how cities in South Africa can integrate urban green infrastructure (UGI) and nature-based solutions (NBS) into planning and development processes (Van der Berg, 2025). UGI and NBS, such as restored wetlands, community gardens, and green corridors, not only mitigate climate risks like flooding and heat but also contribute to biodiversity conservation, improved public health, and more equitable access to green space (Kabisch et al., 2016; Herath & Bai, 2024). Critically, these systems offer a more sustainable alternative to conventional, consumption-heavy infrastructure, which often depletes natural resources and reinforces spatial and socioeconomic inequalities (UN Habitat, 2022).

Her research also contributes to SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) by exploring the role of law in facilitating urban and periurban agriculture (UPA) as a means of enhancing food sovereignty, economic resilience, and local livelihoods. In an Africa-Europe partnership

with colleagues in Ghana and the Netherlands, I examined legal and governance barriers to UPA and identified enabling pathways for integrating food systems into land use and climate planning (Van der Berg et al., 2025). Our findings suggest that food security and climate adaptation are not separate challenges, but converging priorities that require coherent and inclusive regulatory responses (FAO, 2022; Fantini, 2023).

Across these initiatives, my scholarship is framed by a climate justice lens, which interrogates how climate harms and policy responses are distributed, whose voices are included in decisionmaking, and how law can redress historical and structural inequality. This involves unpacking the dimensions of distributive, procedural, recognition, and intergenerational justice as applied to urban climate adaptation (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Okereke & Coventry, 2016). Her recent work on South Africa’s Climate Change Act 22 of 2024, for example, critically assesses whether the Act advances these justice principles or risks replicating exclusionary governance models (Van der Berg, 2024).

At the GELC, we are committed to producing socially responsive research that supports local governments, civil society, and regional networks in building more equitable and sustainable cities. In doing so, UWC continues to play a leading role in driving research that is not only policy-relevant but normatively transformative supporting the realisation of the SDGs from a justice-based, African perspective.

References

FAO (2022). Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture: Emerging Trends in Food Security and Climate Adaptation. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

Fantini, E. (2023). “Governing Food and Water in Cities: The Role of Urban Agriculture in Africa.” Global Food Security, 36, 100676. Herath, S. & Bai, X. (2024). “Nature-based Solutions for Urban Resilience: Integrating Green Infrastructure into Planning.” Urban Climate, 44, 101300.

Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., & Bonn, A. (Eds.). (2016). Nature-based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas. Springer. Okereke, C. & Coventry, P. (2016). “Climate Justice and the International Regime: Before, During and After Paris.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(6), 834–851.

Schlosberg, D. & Collins, L. B. (2014). “From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(3), 359–374.

UN Habitat (2022). World Cities Report: Envisioning the Future of Cities. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Van der Berg, A. (2024). “A Justice Reading of South Africa’s Climate Change Act 22 of 2024.” (Forthcoming).

Van der Berg, A. et al. (2025). “Legal Frameworks for Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture: A Comparative Study of Ghana, South Africa and the Netherlands.” Concept Note, LEAWEF Programme.

DR FARAI MTERO SENIOR RESEARCHER

His research broadly focuses on the nature and character of redistributive land reform in South Africa, specifically the extent to which postapartheid land reform has been equitable and pro-poor. At the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), I have worked on land reform action-research projects, namely the Elite Capture in Land Redistribution in South Africa (2018-2019), and Equitable Access to Land for Social Justice in South Africa (2020-2022). The Elite Capture in Land Redistribution project was co-funded by the Millennium Trust and the Claude Leon Foundation, while the Equitable Access to Land for Social Justice project was co-funded by the Open Society Foundation in South Africa and the Claude Leon Foundation.

Research on elite capture in land redistribution revealed that policy biases in favour of the largescale commercial farming model, elite capture, and corruption resulted in well-off beneficiaries accessing land and production support at the expense of the landless and land-poor. Broadening access to land requires a more inclusive land reform that also supports multiple livelihoods and the social reproduction needs of the poor. In addition, land reform should not be confined to rural and agricultural issues, more so in the light of pervasive urbanisation which occurs against the backdrop of enduring spatial injustices.

Accordingly, in 2023, PLAAS initiated a two-year research project on Inclusive Urban Land Reform in South

Africa. This project was funded by the Claude Leon Foundation. In this research project, I worked with PLAAS researcher, Mr Nkanyiso Gumede. The overarching objective was to understand the key drivers of land and spatial inequalities in urban areas as well as the potential impact of urban land reform on equitable socioeconomic change and democratic citizenship in contemporary South Africa. In South Africa, land reform has traditionally been closely associated with rural and agricultural issues. While land demand for agricultural purposes remains significant, society has rapidly urbanised and urban land questions can no longer be peripheralised. Within urban areas, intense struggles for land, housing and economic opportunity are manifest in the rising evictions, and the proliferation of informal settlements.

Widespread land occupations are evidence of the failure of both the state and market to produce pro-poor land reform outcomes.

The failure of legislation and policy has seen the prevalence of land occupations by marginalised urban populations. Through collaborative partnerships with organisations working in the land sector, the Inclusive Urban Land Reform actionresearch project has sought to amplify marginal voices and promote alternatives to entrenched and exclusionary mainstream land reform and urban development policies. The research documented urban land struggles in selected research sites in the Eastern Cape province. The selected case studies offer an in-depth, contextual understanding of urban land access, its prospects and challenges, and the wider implications for land reform policy in contemporary South Africa.

In addition to intensive fieldwork, the Inclusive Urban Land Reform project prioritised collaborative partnerships with key actors in the land sector. These collaborative partnerships included discussions with civil society organisations grappling with spatial injustices in urban areas, namely the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI), Ndifuna Ukwazi, Reclaim the City, and Intlungu Yase Matyotyomebini. The critical conversations with civil society partners culminated in the hosting of an Urban Land Justice Gathering held from 21-23 September, 2023 at the Homecoming Centre in Cape Town. This gathering focused on urban land struggles for land and housing and brought together different social actors, namely communities, grassroots activists, civil society organisations, policy makers, political actors and researchers.

In 2024, the research team continued with public engagement so as to create space for critical conversations on urban land injustices. As part of the public engagement efforts, the research team collaborated with the Politics and Urban Governance Research Group (PUG) at the University of Western Cape, Ndifuna Ukwazi and the SARChI Chair in Land and Agrarian Studies at PLAAS to co-host the screening of the acclaimed Mother City Documentary on 5 November, 2024. Subsequently, on 29 November, 2024, the research team presented its research to partners—Ndifuna Ukwazi, Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI), and Reclaim the City.

The research team is finalising academic outputs on land occupations and self-provisioning by the urban poor. These bottom-up land occupations

are seen, by the land occupiers and grassroots organisations, as a form of ‘land reform from below’ meant to navigate spatial injustices in the urban peripheries. The Inclusive Urban Land Reform research situates these land occupations in the growing social reproduction pressures experienced by the poor in similar contexts in the Global South. Finally, this project will contribute to wider policy debates on how urban land reform can contribute to equitable socioeconomic change and democratic citizenship in contemporary South Africa.

SENIOR LECTURER

Prof Takalani Mulaudzi-Masuku is a plant scientist, who studies the mechanisms of plant stress tolerance, with the goal to improve agricultural crop productivity under the climate change-induced abiotic stresses to develop staple food crops to eradicate global food insecurity, towards achieving a zero-hunger target. The increasing world population together with the negative impacts of climate change on agriculture, intensified the need to identify high-yielding crops for sustainable food security. Thus, the research group has embarked on studying underutilised indigenous crops because of their inherent stress tolerance traits and high nutritional content. We employ biotechnology approaches coupled with omics and spectroscopy techniques to identify the

highly stress resilient cultivars and advocate for the consumption of these crops. Furthermore, the novel insights discovered in this regard, will be used to breed stress tolerant crops, such as maize and wheat. Thus, my research provides solutions to combatting malnutrition, poverty, and hunger, contributing to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1, 2, and 3.

Besides being climate smart crops, their growth and yield are affected by severe and prolonged stresses. One of the sustainable solutions to this problem is the use of environment friendly agrochemicals at low concentrations. Using sorghum as a model indigenous crop, we previously showed the effectiveness of some biological compounds, including calcium, chitosan, methyl jasmonate (MJ), carbon monoxide (CO), and green-synthesised nanoparticles, among others, to enhance seed germination and growth under severe abiotic stress. This led us to developing seed priming products, where the first prototype was a “chitosan nanoparticle encapsulated with CO” compound, which successfully eliminated Fusarium verticillioides that infects maize (Khameli, 2023). Due to this success, we aim to develop more products, and use them to prime seeds of commonly grown crops, for example, maize, followed by testing, commercialisation, and communication with farmers and seed stores, such as Agricol and Seed Co., among others.

The knowledge created from this research can be more impactful, if the data is not only published in scientific journals, but also made available to local communities. To achieve this goal, we

work as a team: [Mr Puza and Prof Ngece-Ajayi (founders of Ukhanyo NGO and Amaqwawe nge’ Mfundo NPO, respectively); selected schools; local farmers (Ms Akhona Gxuluwe, from the Handpicked City Farm in Kenilworth Centre); Dr Mulidzi (Agricultural Research Council); Vukani News; local radio stations (Radio Zibonele and Bush Radio)] to host community engagement workshops in the townships particularly in Khayelitsha. Last year at Lukanyo library hall, we shared knowledge about the nutritional value and cultivation guidelines of Amaranthus, an underutilised indigenous crop, and provided different food types produced from this crop. We received positive feedback via questionnaires and Vukani News, and generated four reports approved by our funders, the Water Research Commission (WRC). Our next goal is to conduct school gardening initiatives in townships to promote healthy eating, and provide hands-on agricultural education on biological seed priming products; sustainable irrigation practices; and cultivation of indigenous crops, thereby addressing SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

References

Khameli, K. (2023) The development of carbon monoxide-releasing chitosan nanoparticles composite for the elimination of Fusarium verticilliodes, MSc thesis. University of the Western Cape.

https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13060782

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241210368 (registering DOI)

https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12071425

doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12101544

doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12050597

doi :10.3390/plants9060730

https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14040662

https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14040662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ molecules220609263

UNIVERSITY

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by the United Nations as a universal call to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people will enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030. The goals are integrated and they recognise that action in one area will affect outcomes in others. The SDGs are designed to end poverty, hunger, and discrimination against women and girls. It is also believed that creativity, knowhow, technology and financial resources from all of society are necessary to achieve the SDGs in every context. Globally countries have committed

to prioritising progress for those who are furthest behind. In this regard, Goal 1 calls for No Poverty, Goal 2 calls for Zero Hunger, Goal 12 insists on Responsible Consumption and Production, and Goal 13 calls for urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Prof Mulugeta F. Dinbabo is an established researcher at the Institute for Social Development, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape. Currently, Professor Dinbabo and his team are conducting an important study assessing the existing body of knowledge on the SDGs, climate change, and migration within the African context. This initiative offers valuable insights for both scholars and practitioners who are working on sustainable development challenges on the continent.

In the past few months, his research team has carried out a comprehensive review of relevant literature, reports, and policy documents concerning SDGs, climate change, and migration in Africa. This extensive analysis helped to understand continental-level challenges and

key knowledge gaps that need to be addressed. In addition, the team performed an in-depth data analysis to explore how environmental transformations are influencing migration flows and affecting socioeconomic conditions across African regions.

The findings from this research assisted in publishing scholarly articles about these interconnected issues. These contributions aim to advance current understanding and inform policy decisions on the impacts of climate change on sustainable development in Africa. By highlighting the importance of integrated approaches and evidence-based strategies, the project supports the broader goal of achieving the SDGs.

Over the next two years, the project will actively engage researchers, as well as PhD

and MA students, in a collaborative effort to develop an annotated bibliography focused on the SDGs, climate change, and migration in Africa. This will serve as a critical resource for further academic inquiry. The team remains dedicated to publishing in accredited journals and contributing to book chapters. They also engage in exchange programmes and attend conferences to disseminate their findings and promote collaboration. As the research team continues to advance research at UWC, they look forward to working with incoming postgraduate students at the Institute for Social Development.

DIRECTOR

NATIONAL

At the University of the Western Cape, the DSTINRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE-FS) is committed to research that not only explains the world but changes it. In our pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), we have focused on place-based, participatory work that builds relationships, deepens understanding, and supports action. In the Breede Valley Municipality (BVM), and particularly in the secondary city of Worcester, this has taken the form of a multi-year collaboration with all spheres of government, civil

Our approach is grounded in a commitment to knowledge co-production. We do not consult with communities; we walk with them: through their food environments, through their stories of precarity and innovation, and through their struggles for recognition and support. Learning journeys, facilitated by the CoE-FS, alongside partners such as the Western Cape Economic Development Partnership, have brought together stakeholders from all corners of the local food system. These engagements have shaped collective understanding and catalysed tangible changes, namely land access for food gardens; new partnerships to support unregistered Early Childhood Development (ECD) centres; and local government commitments to improve service delivery in underserved neighbourhoods.

To strengthen these participatory engagements, we have paired them with an innovative spatial modelling approach. Using a Bayesian network model built on local dietary and vendor data, our team simulated the likely impacts of proposed interventions, from school feeding and soup kitchens to improved public transport and safer streets. The model revealed the differing needs of neighbourhoods, such as Avian Park and Zwelethemba and showed how combinations of localised policies could shift diet quality and food access across the city.

This modelling was not a backroom exercise as it was participatory and iterative. Community leaders, municipal planners, and civil society organisations worked alongside researchers

to interpret the findings, refine interventions, and co-design a food system policy package for Worcester. This integration of experiential knowledge and technical evidence reflects our broader approach: democratising expertise and ensuring that research speaks to the lived realities of those it aims to serve. The process is well described in our documentary produced with a local partner, Lucentlands, for which we have been nominated for a National Science and Technology Forum (NSTF) award, the “Oscar” of the South African scientific community.

While our focus has been on SDG 2, our work also contributes to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and

Communities), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Together, they reflect our belief that food systems transformation requires more than policy reform. It needs place-based solidarity, grounded science, and shared responsibility. Through our work in Worcester and beyond, UWC continues to shape a model of engaged scholarship for a more just and food-secure South Africa.

References

The documentary can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jy49iIxV0o8 Academic papers can be viewed at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2025.102878 and https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-024-01502-8

WRITER: MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

DVC: RESEARCH AND INNOVATION OFFICE

UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE

Leveraging Research Innovation for Zero Poverty, Zero Hunger, and Sustainable Consumption

Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1 (No Poverty), 2 (Zero Hunger), and 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) requires a bold reimagining of

how research can be harnessed to tackle complex, interconnected global challenges. At the heart of this transformative agenda lies the necessity to advance food security, improve livelihoods, and build sustainable, resilient agricultural systems that serve both people and the planet.

Addressing SDG 1 (No Poverty) requires that research outputs directly benefit vulnerable populations, especially smallholder farmers and marginalised communities who are most affected by poverty and food insecurity. Research that identifies climate-smart, cost-effective, and scalable agricultural solutions contributes significantly to improving household incomes and food access. For example, empowering local farmers with knowledge on drought-tolerant crops and resource-efficient farming techniques enables them to diversify their livelihoods and withstand climate-induced shocks, breaking the cycle of poverty.

Aligned with SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), research on crop resilience, food security, and sustainable agriculture is fundamental. The development of stress-tolerant staple crops through biotechnology and the promotion of underutilised indigenous crops can improve both the quality and quantity of food production. These crops not only offer resilience in the face of climate change but also deliver vital nutritional benefits, contributing to healthier populations and more stable food systems.

Furthermore, SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) calls for more sustainable practices throughout the agricultural value chain. Research initiatives that promote environmentally friendly agrochemicals, sustainable irrigation

practices, and waste reduction strategies contribute to more sustainable food systems. Knowledgesharing partnerships with NGOs, schools, and farming communities foster responsible consumption habits and encourage local food production through initiatives like school gardens and community workshops on indigenous crops and nutrition.

In summary, integrating these SDGs within research frameworks strengthens the role of science in delivering tangible societal impact. By promoting climate-resilient agriculture, reducing poverty, and encouraging sustainable consumption, future-facing research contributes directly to building more equitable, food-secure, and environmentally conscious societies.

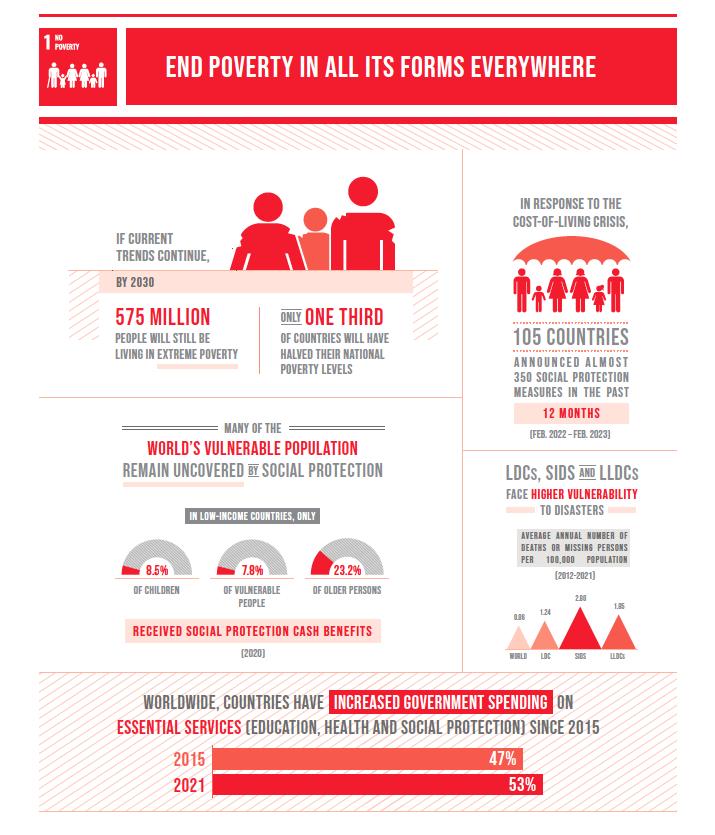

Eradicating extreme poverty for all people everywhere by 2030 is a pivotal goal of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Extreme poverty, defined as surviving on less than $2.15 per person per day at 2017 purchasing power parity, has witnessed remarkable declines over recent decades. However, the emergence of COVID-19 marked a turning point, reversing these gains as the number of individuals living in extreme poverty increased for the first time in a generation by almost 90 million over previous predictions.

Even prior to the pandemic, the momentum of poverty reduction was slowing down. By the end of 2022, nowcasting suggested that 8.4 per cent of the world’s population, or as many as 670 million people, could still be living in extreme poverty. This setback effectively erased approximately three years of progress in poverty alleviation.

If current patterns persist, an estimated 7% of the global population – around 575 million people – could still find themselves trapped in extreme poverty by 2030, with a significant concentration in sub-Saharan Africa.

A shocking revelation is the resurgence of hunger levels to those last observed in 2005. Equally concerning is the persistent increase

in food prices across a larger number of countries compared to the period from 2015 to 2019. This dual challenge of poverty and food security poses a critical global concern.

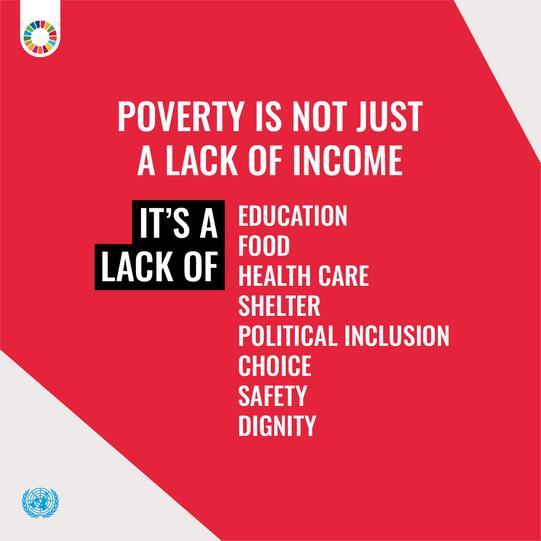

Poverty has many dimensions, but its causes include unemployment, social exclusion, and high vulnerability of certain populations to disasters, diseases and other phenomena which prevent them from being productive.

There are many reasons, but in short, because as human beings, our well- being is linked to each other. Growing inequality is detrimental to economic growth and undermines social cohesion, increas- ing political and social tensions and, in some circumstances, driving instability and conflicts.

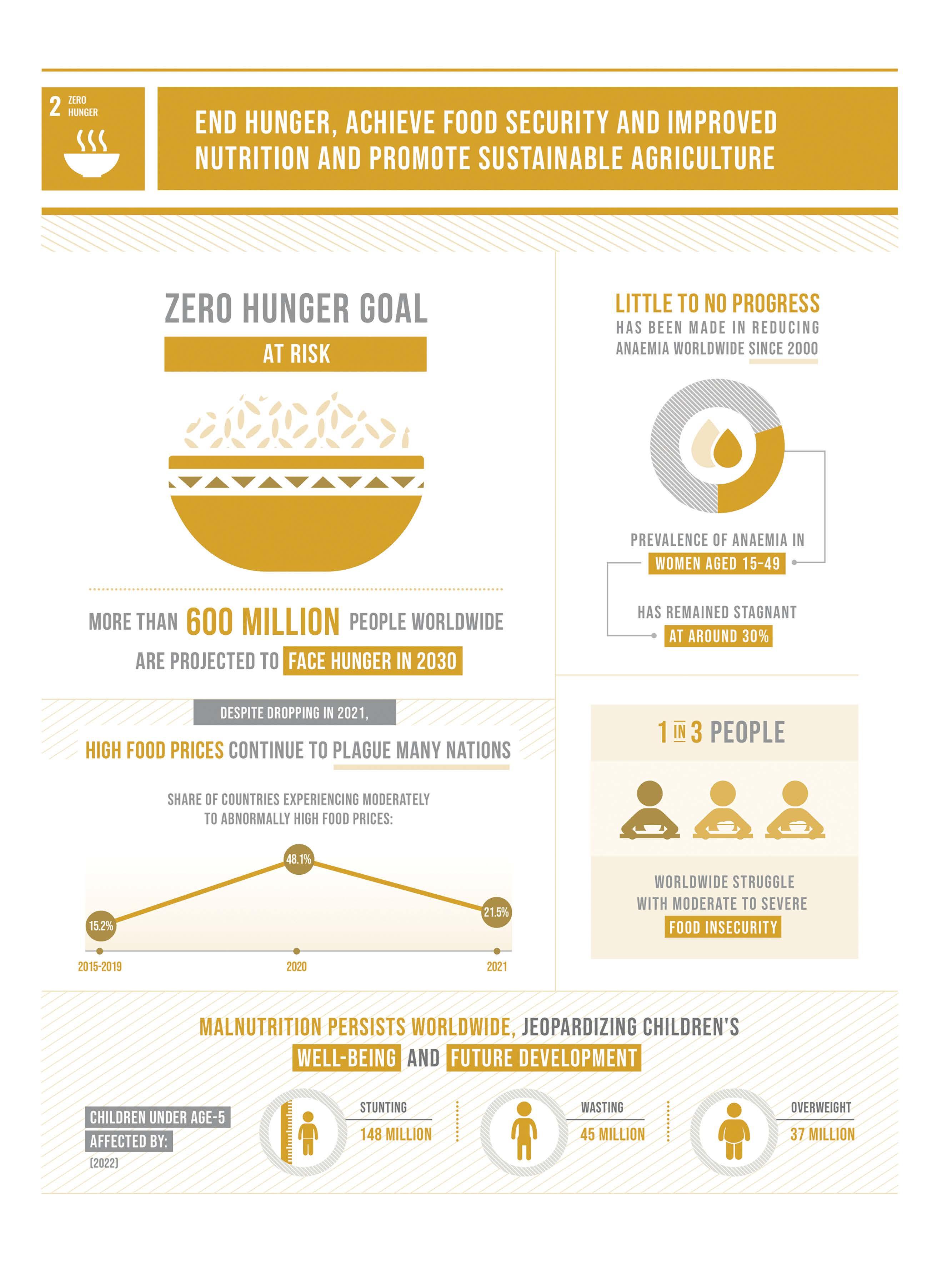

Goal 2 is about creating a world free of hunger by 2030.The global issue of hunger and food insecurity has shown an alarming increase since 2015, a trend exacerbated by a combination of factors including the pandemic, conflict, climate change, and deepening inequalities.

By 2022, approximately 735 million people –or 9.2% of the world's population – found themselves in a state of chronic hunger – a staggering rise compared to 2019. This data underscores the severity of the situation, revealing a growing crisis.

In addition, an estimated 2.4 billion people faced moderate to severe food insecurity in 2022. This classification signifies their lack of access to sufficient nourishment. This number escalated by an alarming 391 million people compared to 2019.

The persistent surge in hunger and food insecurity, fueled by a complex interplay of factors, demands immediate attention and coordinated global efforts to alleviate this critical humanitarian challenge.

Extreme hunger and malnutrition remains a barrier to sustainable development and creates a trap from which people cannot easily escape. Hunger and malnutrition mean

less productive individuals, who are more prone to disease and thus often unable to earn more and improve their livelihoods. 2 billion people in the world do not have regular access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food. In 2022, 148 million children had stunted growth and 45 million children under the age of 5 were affected by wasting.

It is projected that more than 600 million people worldwide will be facing hunger in 2030, highlighting the immense challenge of achieving the zero hunger target.

People experiencing moderate food insecurity are typically unable to eat a healthy, balanced diet on a regular basis because of income or other resource constraints.

Goal 12 is about ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, which is key to sustain the livelihoods of current and future generations.

Our planet is running out of resources, but populations are continuing to grow. If the global population reaches 9.8 billion by 2050, the equivalent of almost three planets will be required to provide the natural resources needed to sustain current lifestyles.

We need to change our consumption habits, and shifting our energy supplies to more sustainable ones are one of the main changes we must make if we are going to reduce our consumption levels. However, global crises triggered a resurgence in fossil fuel subsidies, nearly doubling from 2020 to 2021.

We are seeing promising changes in industries, including the trend towards sustainability reporting being on the rise, almost tripling the amount of published sustainability over just a few years, showing increased levels of commitment and awareness that sustainability should be at the core of business practices.

Food waste is another sign of over consumption, and tackling food loss is urgent and requires dedicated policies, informed by

data, as well as investments in technologies, infrastructure, education and monitoring. A staggering 931 million tons of food is wasted a year, despite a huge number of the global population going hungry.

Economic and social progress over the last century has been accompanied by environmental degradation that is endangering the very systems on which our future development and very survival depend.

A successful transition will mean improvements in resource efficiency, consideration of the entire life cycle of economic activities, and active engagement in multilateral environmental agreements.

Share your postgraduate journey with us, to share with others.

Contact: Tamara Goliath (tgoliath@uwc.ac.za) Writer, DVC: Research & Innovation Office

Join us on the DVC: Research & Innovation Social Media platform pages for the latest information on upcoming webinars and more. #MakingResearchCount #FutureResearch #eMag13th