In every fragment of our lives, whether in shadow or in light, storytelling stands as a beacon, illuminating our paths as the world rotates on its axis.

These pages represent our labyrinthine walls covered in hieroglyphics and messags - each work defies the relentlessly confining bonds of interlocking cogs. Instead, we seek a freedom that can be realized among the sun and beneath the stars, in darkness and light, and all the liminal spaces in between. With illustrations as delicate as the waxing hues of dawn and poetry as profound as the waning shades of twilight, we chart our course along the shores that lead us to new temporal horizons.

In this way, we delve into the paradoxical nature of time.

Time is the only constant in our world, yet it fosters and changes the variations of what we see. Subject to our whims, we squander it, save it, borrow it, waste it — it’s a currency that we shape or succumb to. It is irreversible, and yet cyclical, existing to help us curate the recollections of our past and anticipate our future.

Thus, as sundial casts its solemn shadow upon the shifting sands of day and night, it stands as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit when confronted with the uncertainty of each blurry sunset and every mellowing second that passes by. Here, time is not merely a measure,

but a muse, one that captures each fleeting thought and echoing truth. Each etch upon the sundial marks the passage of not only hours, but also of the changing forms of the world between every numeral - and by association, the changing forms of each human experience.

Perhaps you resonate the most with the Dawn — the purity, the quiet mornings, the singing birds. The simplicity, the creation that blooms from your fingertips.

Or maybe you prefer the High Noon, the hustle and bustle, the world rotating on its axis. The heads held, the lines crossed. You’ve never felt more alone, yet alive.

Rather then the newness of the Dawn or the cycles of the High Noon, maybe you’ll sit with the Dusk, the solace, and the quiet. A time for contemplation, or no thought at all. You can leave it up to the evening breeze.

But alas, there may be nothing that strikes quite like Midnight, when time begins to blur and you find yourself wandering. The manic, the mundane. The elation and reflection. The night seems endless, and so do the streets outside.

And yet, the Sundial sits, marking the hours of the day in its solitude. And, dear reader, it is up to you to decipher them — to unveil the hidden details of the quotidian that come with every shifting shadow. To observe how — as time changes — so do we.

Thank you for picking up Issue #2 of the Fine Print, the official literary magazine of East RIdge High School. We could not be more elated to share our second volume with our community - to provide a platform for students to express themselves in the most tangible forms of storytelling and visual arts.

With this issue, we bring our first year as a publication to a close - and we couldn’t be more proud of the dedication, care, and excitement we’ve seen throughout our journey so far. As we continue to share work from our community, we are in awe of the talent, artistry, and creativity that our student body has shared with us and their peers. The stories between these pages are candid and unyielding - yet it is only by connecting these fragments of human experience that we may create a tapestry of perspectives and change.

Throug h this shared community, we hope to continue amplifying these ideas and experiences with whomever will read and listen. If you have a story or artwork to share, head to our Instagram @thefineprint833 for more information on submissions or to join our team.

The goal of The Fine Print will always be to continue sharing stories as brightly and boldly as possible. Until we meet again, keep creating, writing, speaking, feeling. The human experience is an art - and we are proud that we can share a glimpse of it with the world, one page at a time.

We are proud to present - The Fine Print, Issue #2: SUNDIAL.

Every sunrise begins with emerging light. The day begins, unmarred and palpable. Shadows pool across corners, paint for the world’s canvas.

Every day, a blank slate; every moment, a new beginning. For the sun has just risen, and there are seconds before the sundial’s shadow begins to shift.

poetry, Braden Greenberger

The anticipation before the storm. The maestro makes his final adjustments. Though this is no broadway show, His band maust be pitch perfect. The maestro’s needle springs to action; The symphony begins.

A horn that could belong to Gabriel himself starts to bellow its hymn. Soon, the thunder of drums joins the fray, And the soft thumping of the bass creeps in. One by one, the tributaries annunciate themselves, Echoing their previous performances. Flowing together, they join. Each member contributes its part, Coagulating into solid form. The river calmly swirls, Needle meets vinyl, And a symphony is born.

Born without anything, to parents who fought so hard. Born in the Namyao camp, running away from the blood shed.

Father was a knife and Mother, a needle.

Not sure of what’s ahead, will we have to tread?

Young and forgotten like a piece of thread

She played outside till she’d shiver

1975, the first Hmong people came to America

Where are the Ancestors? Will they deliver?

1991, arriving in America

Leaving Thailand, a home they had fled.

Modern America was agriculture and industry

How about me? What is my stead?

With kind teachers, she listened and learned

She opened up her ears and grasped the English language

She married my father in her high school years

Is it just me? Who else has the baggage?

Finishing high school with 1 child in her hand

Obtaining a college degree and building her home

Grown and matured, she had created it all

Have I finally escaped the gloam?

Being Hmong and learning to be American,

My mother is a testament.

Born with the old, learned the new

Have I found my element?

Her blood carries our history

And she will be the first to realize

Connecting the past to the present

This is freedom, this is being alive

This is freedom, This is being alive.

CHATTERBOX

Nina Krejci

CHATTERBOX

Nina Krejci

Bree has a sudden and unsettling urge to continue the conversation, and she finds herself pausing. She is unused to this impulse. Where is it coming from?

excerpt from The Buddy Bench, Emilyn Troup, pg. 50

In the cathedral off of 51, where the houses are ten minutes apart from each other and all you can hear is the passing of cars through the road as they kick up dust, someone is playing the piano on a Tuesday.

I can hear their fingers tap against the ivories, and I can hear the desperate way every note clings to the latter half of the one that came before it. My bones ache with every step, and yet my feet drift closer to the entrance of the church, stained glass windows blinding me against rays of light reflecting off stained glass windows. I lift my hand to shield my eyes, but it falls back down.

The dr y heat of Tuesday sinks into my shoes, and I have a creeping feeling that it’s been too long since a car has passed through here. Hot, burning sand surrounds my ankles, like a hand reaching up to grab me and pull me down. With no cars passing through, the only audible sound is the piano.

The stone stairs up to the entrance of the church both have a layer of dust on them and seem well trodden. I try to search for the tracks of the pianist, but I can’t find them. My hands waver in front of my face; I must have forgotten to bring my water bottle.

I reach for the ornate metal handle on the door. When I enter the church, the music grows

exponentially louder. The crashing notes, much lighter in tone and mood when I first heard them, clash and fight against each other. A deeply out of tune instrument, by the sound of it. It should make me turn away; it should make me disinterested, but there is beauty in how hard it tries and fails. By the reverberation, the pianist is pushing the keys with force. It does not fix what is broken: the strings inside, thinning to a thread.

It hurts, how loud it is. I begin to walk closer, past the gathering room, following it. Desperately trying to find the source of the sound, it leads me down a hallway first, then several. A set of stairs I waste no time climbing, exhaustion present but ignored. Sometimes, I look at the other rooms as I follow the noise. The first time, it was an office, with the papers all on the floor and scattered every which way. The second time, it was a child’s playplace, with faded toys and blocks across the carpeted floor.

After that, I stopped looking at the other rooms.

My feet ache with every step, and my muscles tremble like they’ll give out any second, and yet I know they won’t. When I reach the hall, and the music plays so loud it’s like it’s ringing through my eardrums, down my spine, I begin to sprint. Towards the end of the hall, towards the piano, towards what will save me. The sweat-wicked cloth of my clothes flutters above my skin as I run, dashing wildly as if I’m going to run through the doors, but they burst open of their own accord.

It’s a miniature chapel. There are three, four rows of pew seats that must only be a few feet in length. The carpet that divides them stretches to a diamond-shaped platform, encircled by stained glass. A piano sits in the center of the room.

It falls silent, the last note ringing. And even when it should’ve stopped, it stays reverberating.

I sit down in the nearest pew, and I listen.

When my hand is moving the pencil A mere thought becomes lead on paper

The lead gets shorter and shorter While my thoughts are only growing

A line, a word, a curve, a squiggle

The pencil is a delivery truck For thoughts that are not good at just being a thought

Soft sound of the pencil soothes the most frantic person With a soft scratch of the lead on paper

My thoughts are flying free While grounded, still am I.

poetry, Samantha Pedersen

poetry, Samantha Pedersen

creative

nonfiction, Nina Krejci

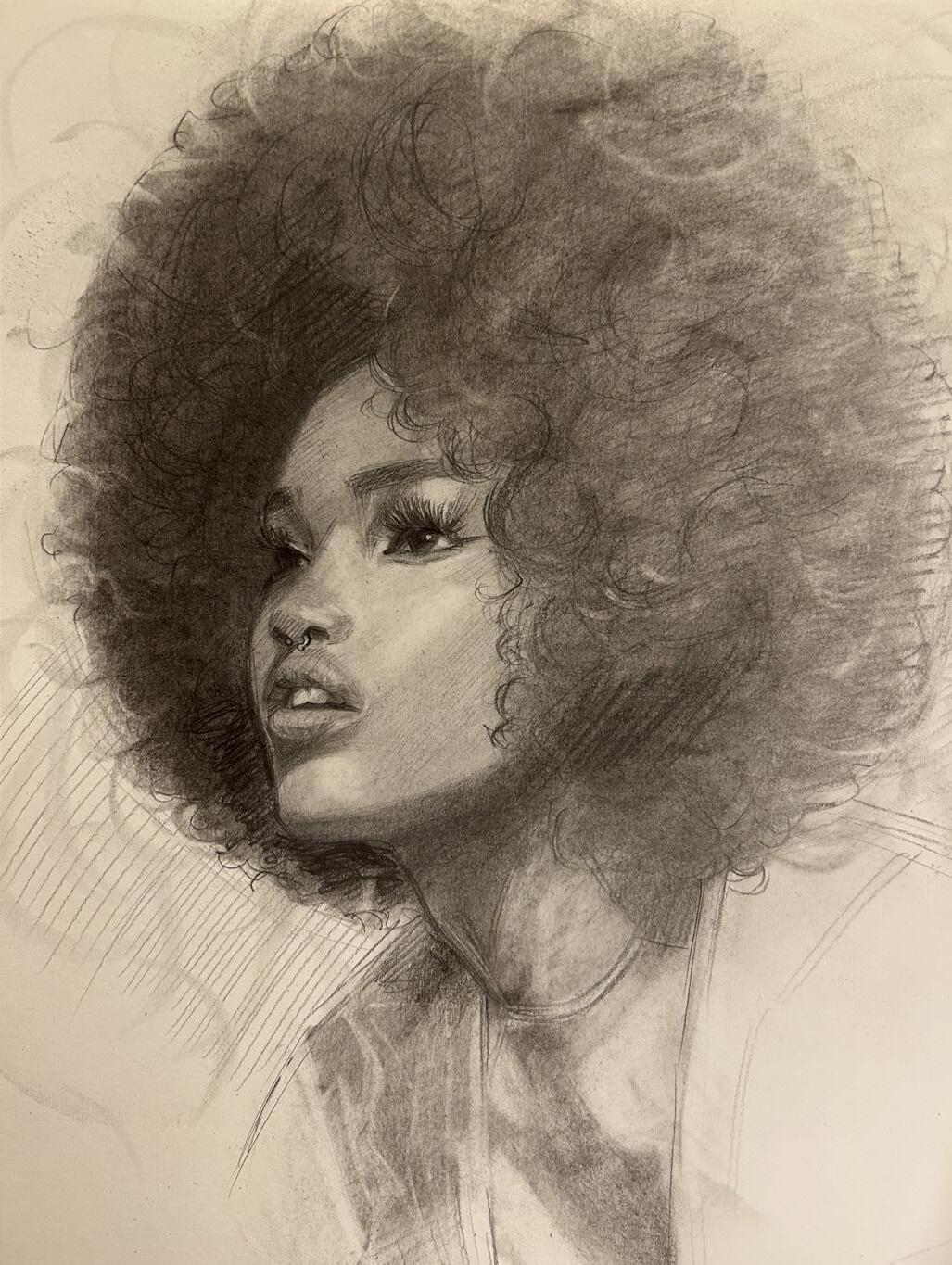

It is twisting, and violent, and tense; it’s the noose that hangs my condemned hairbrush, splintering, subjected to the same fate as its predecessors. Its roots slither all the way to the ends like a knot of boomslang serpents, hanging and blending with the vines that fall in their indecisive pattern. Oh, how those lithe and heavy strands rest in the most ferocious and feral of curls.

It is a vast jungle deemed the wild of my ancestors. And it will be conquered like them too.

As I grew up, it became more and more of an insurmountable task each morning to make myself presentable. I would stare at the mirror and see a little girl with curls that went in all the wrong directions, curls that would never match the straight streams of my tears. My hair was “affectionately” called my rat’s nest, my tornado, my crazy, but the words of my family members and teachers never seemed to ease the embers being stoked in the pit of my stomach. Soon those embers would ignite. As I begged my mother to confine my chaos into neat, simple braids, she would sigh, and soon, she would tell me it was time.

It is a vast jungle deemed the wild of my ancestors. And it will be conquered like them too.

It was time for my ritual, just like the ritual of every single woman in my family who had been cursed with their own jungle for as many generations back as I can fathom. To do anything to fix the broken, before asking why I couldn’t have just been enough from the beginning. They didn’t need to drag me up the steps; the higher I climbed, the closer to the gods I felt. The ritual took place at the very peak of a pyramid, right at the center of Tenochtitlan, where the crowds were packed and

CROWN Evie Wang

CROWN Evie Wang

their shouts, praise, and prayers were bestowed upon me.

My mother had finally taken me to get my hair relaxed, or chemically straightened, at her salon. I was in the third grade, and from that moment on, it was all I knew. Two times a year for the next five years of my life.

No longer was I sneered at, insulted, or berated, and so, I held my breath and met my fate with melancholy eyes and a smile. Even though the blade was sharp, it was also beautifully straight.

The guns and the disease began to discover my jungle, but of course, they did more than just explore. They razed, and pillaged, and burned my jungle to the ground. They aligned the crooked and curly how they aligned their rows of bayonets aimed towards the priming. Once a place of life, from the gentlest frogs to the roaming jaguars, now bound and brought to its knees in a worthless silence, staring down its own death. They didn’t hesitate to shoot.

But a soul is not so easily killed, and ancestors are not so easily silenced. I remember the day I took a pair of scissors to my head, and cut close to the root. And I remember the first time I looked at the mirror, with my curls freshly regrown, and I smiled.

Slicked-back ponytails. Faded laughter. A swing set, a cloud of exhaust. A memory, crisp and light, stamped into stone as the seconds pass.

The day melts like paraffin, dripping and slick. The world skates in circles, blurring, busy, bustling. Upon the sundial, time pools between each shifting shadow. It’s hot to the touch, but it’s never been more alive.

INTO THE UNKNOWN Dwayne

Abella*this is a contrapuntal poem, which means it can be read 1) down each column or 2) straight across the page.

poetry, Ariana Li

today, freedom sheds its skin. runs valleys, inside my mouth until my cheeks swell. marrow shrinks in and i’ve never felt heavier, oil bubbles, a lake steaming, saltless blue skies, ripples in the palm of my hand. today, i close my fist. i pull streams through my fingers, leeches and mud, woven between folding water. summer bulges, becomes a lion’s mouth, mawing, hot, and still opens to the touch. sweat watching me leave the dock.

bite-sized fingertips, my heels become concrete the lake swims under the bridge of my nose. hope is the color of wounds that won’t close. look at my veins, tracing, bone and finger, churning. skin, it’s sharp as it strains. hands, the polyester straps. i fill myself with gold, it scrubs away, a jaw that gums itself into the water. today, i cannot swim.

AARTIST STATEMENT

n animated short film about a day in a high schooler’s life in 2023, with the world slowly melting outside the window and notifications bursting from the computer screen. We are constantly reminded of our unavoidable responsibility to remedy our current circumstances, because previous generations have failed to do so.

poetry, Anonymous

On day of moon, as minds linger awake

Consciousness searches the farthest of corners

The grip of nothingness they cannot shake

In the land of dreams, they are foreigners

Eyes are opened in time, at sights they’ve seen

Never again will they come in between.

GOODBYE SMELLS LIKE TOLL STOPS AND CROSSING TIME

ZONES, but right now, the air of the fourth-floor lounge is chilly in the building of a college I don’t actually attend. Cross-legged on the floor, laptop balanced on your knees, you rattle speeches into the bricked plaster wall in front of you. In the silk of the summer, I watch your voice empty itself clean.

Debate camp is stuffy and wonderful. The kids in my cohort have the wisdom of fathers and the mouths of rowdy sons. The plastic fan in my dorm clatters and shakes bits of TOPICALITY! PRAGMATISM! UTILITARIANISM: AND WHAT IT MEANS! all over the carpet. During lecture, I run my fingers across the balconies of every window, watching a brightly colored flag dance across the street.

ALL ARE WELCOME HERE! It shouts, but it takes me longer to believe it.

Work. Check-in. Work. Lecture. Lights out, but no one really listens. The air buzzes with male academia and boba runs. I am told about archaeology, I am told about the Anthropocene. I stare into the sticky keys of my laptop, and I write all of my arguments in my head. To practice my enunciation, my mentor tells me to give speeches to a wall. She says it’ll be like someone is listening to me, but without the crushing weight of

WIN! LOSE!

ACADEMIA-FANFARE! on my shoulders.

So, during our lunch break, we plant our feet in front of the plaster between the bathrooms and the bulletin boards, and read our speeches like we’re really doing something, like the too-cold air conditioning believes we have something to say.

The day is slow and syrupy and WE PROVIDE THOUGHT LEADERSHIP

I chew through my thoughts, AND EXPLAIN KEY ISSUES THAT DEFINE Palms pressed into carpet, OUR CHANGING WORLD.

I watch the lines on your laptop dissolve into twined strings of dots and letters. Keywords poke holes in my vision. A cloud of ARREST! STORMS! MISDEMEANOR! and I spit out an entanglement of threads. I sound too nice, you grumble. I laugh when reading long statistics I stumble over civilian casualties I can’t pronounce half these names like are we sure they’re supposed to be world leaders?

I laug h loud, with my head thrown back. I don’t miss the way you glance over at me, startled at the sound (but one day, I will.)

During lectures, I know too much and too little to join the conversations. I put my feet up on a chair, and the smarter kids argue about whether or not putting military troops in Antarctica will lead us to a slow and grinding death.

Someone yells, we are going to DESTROY THE WORLD, and someone else yells back, not if the OIL SPILLS do it first. They wonder aloud which one of the two is more dire, more probable. As if lives can be measured by the weights in the palms of their hands.

We talk about relativity, we talk about the HEAT DEATH OF THE UNIVERSE. I revel in the snark that can only be found between the teeth of sixteen year old girls. Tension rises above the wooden tables and we wait for the classroom to go nuclear, and I chew on whispers and feminism and the sticky grooves of my lanyard. A boy with a silver earring explains to us why SOLIPSISM IS THE ROOT OF OUR FAILED DEMOCRACIES, and throws down his pencil when someone asks for his sources.

I eat packets of fruit jelly as I am told that Russia will be cutting our undersea cables, that I should be ready in case I am cut, too. I am told that for as long as these cables are alive, so am I, twisted into ropes of DATA AND BLOOD. I am told that my voice can only echo the noise of the world.

That nig ht, a girl from a preparatory school ships boxes of four-dollar energy drinks to our dorm. The reader flickers as you swipe your key card, and I am no longer begging to be let inside. We trade hands of imitation poker. You tell me to HIT ME! and I slide over a playing card, then two more. Sometime in between passing and folding, the group begins to argue about the arguments they wrote yesterday morning, a tangle of scoffs and clattering teeth. I ignore the glances PASSED between diet cokes and phone chargers. I ignore the MISERY folded between notepads and G-2 Pilot pens. I ignore the powdered sugar, FALLING to the floor.

THIS JUST IN: IT HAS BEEN 13 DAYS, and I have forgotten how to read the news.

On the last day, we eat cold pizza with our backs to the plaster wall. It is almost midnight, so I trade strands of cheese for promises, drawing them out between my teeth. The smell of oil and fossil fuels hangs around us, coating the

hallway in plastic film. I beg this time to stay monochrome. I stretch every second of this bottomless summer.

Pictured above: one who writes the world and one who creates it. Pen ink tracing hopeful papers. In an empty room, our notepads sit, left behind, listening to the whispering ends of snack runs and bottle spins. Scrawled with bits of arguments and rebuttals and poetry. The night before, we decided that nothing we’d written was in line to save the world. We will linger only in scraps of yellow paper, dissolving into shelves. In dried out G-2 pens and our use of renewable energy. In the way hydropower illuminated us, white and silent, in front of cracking plaster walls.

VOICE Amelia Swarts

BREAKING NEWS: KROENIG 15 (Matthew Kroeing, Associate Professor and International Relations Field Chair at Georgetown University) TELLS US that the spread of nuclear weapons poses at least six severe threats to international peace and security. Including but not limited to: INSTABILITY! CONSTRAINED FREEDOM! and, PROLIFERATION!

Of what, the article never says.

But it is July now, and you complain to me over the phone that Kroenig’s theory had nothing on what going home was like, missiles and fuel rods be damned. That I might as well prepare myself for the world to sink into itself and shatter. In each lasting huff of the summer, the world scrolls by around my bed. It never seems to pause.

Instead, I spend my days drowning my mouth in listerine and plastic water bottles. I wade my way between red solo cups and tarps, sticky upon the beach. Somewhere, in a small college seminar room, a group of sophomores tell me that I am perpetuating the use of microplastics, that

EXPOSURE = OXIDATIVE STRESS! DNA! DYSFUNCTIONDISORDER!

In my head, I thank them for confirming what I already know: that the future of the planet rests impossibly in my hands. Bottle caps fall off my desk and onto the floor.

BREAKING NEWS: THE WI-FI AT YOUR SUMMER HOUSE IS BEST USED AFTER 9PM

On a road trip, you FaceTime me and tell me about how your parents got lost in the suburbs on the way to the city. How the GPS broke down but not to worry, CHINA IS INNOVATING new technologies as we speak. You tell me that in fifty years, (thanks to NEWLY-DEVELOPING-TRILATERATION-TECHNOLOGIES), it will be impossible to lose your way.

We talk about the boy you saw on the subway, who had a Keith Haring tote bag with a bottle-cap pin on its strap. We talk about a copy of The Economist you found shoved in your backpack, about the senior who probably put it there. We do not talk about goodbyes, or the way I cried into the cracks of an airport bench. We do not talk about the months since then, or the

THOUSAND-YEAR-EVOLUTION! of the world, or the THIRTEEN-DAY-EVOLUTION! of us.

Pictured above: how I joke about us meeting someday in a crowded banquet hall. Fat with the sway of music and businessmen. You worry for the FUTURE OF THE STOCK MARKET, if the parties and galas will ever stop waxing themselves into the floor. If boys with silver earrings will tear academia from limb to limb. In the back of my head, I convince myself: I am entitled to this dream. That our fingers will always smooth the kinks between cold pizza and the WILDFIRE CRISIS. See, I can make

everything seem brighter than it is. And for the first time, I want someone to believe me.

Pictured above: blueish pin points suspended above a vast green terrain. One hundred and thirty three games of Word Hunt. Discussing our silver lives with loose tongues. You call me on the phone. Subway boy, turns out, is a real piece of work. You tell me about how he pressed a shrug between his lips and left you next to the bus station on 96th street. He left at 6:04pm, you say, and I imagine him, really, striding away into the street with his perpetual subway-boy slouch, all pecking-crow between trash-can. Minneapolis is an hour behind. Does that mean in Minnesota, he hasn’t left yet?

But the plane ride to Minneapolis is 3 hours long, and I tell you that it is a gap we will never be able to overcome. The difference, I think, is called waiting.

Down the street from my house, a flag droops in the wind. Every afternoon has become an overpainted sidewalk: melting yellow cradled by the curb. I practice with the rest of my team now, where nobody wants to speak and everyone wants to win. My coach tells me about my fatal flaw: my LACK OF CONFIDENCE,

My CASUALTIES, my DESTRUCTIVE NATURE.

That day, I am read like a HEADLINE: THROUGH A GLANCE. I can’t say I hate her for it.

But, I have learned to feel fantastic, about these things. I understand what you meant back then, with our wet words pressed into plaster walls. The way ARREST! STORMS! MISDEMEANOR! sounded soft-swirled between strong voices and city hearts. I shrug at my teammates. You wanna get lunch after practice?

We start school two weeks apart and I stare at the backs of neon hoodies, latched onto metal rungs of desks and post-summer slump. You will laugh when I tell you that there is not a single silver earring in sight. You will ask me for more files of Kroenig and pedaology, and you will act surprised when I tell you: I’ve left them all behind.

We have stepped forward, but cautiously. We collect our paper trails in plastic binders.

We will speak to plaster walls again and never feel alone, and We will buy newspapers without knowing what they say, and We will tell ourselves to join battles we never started, and The world continues to rotate with outstretched arms.

LAKESIDE

Sarah Yu

LAKESIDE

Sarah Yu

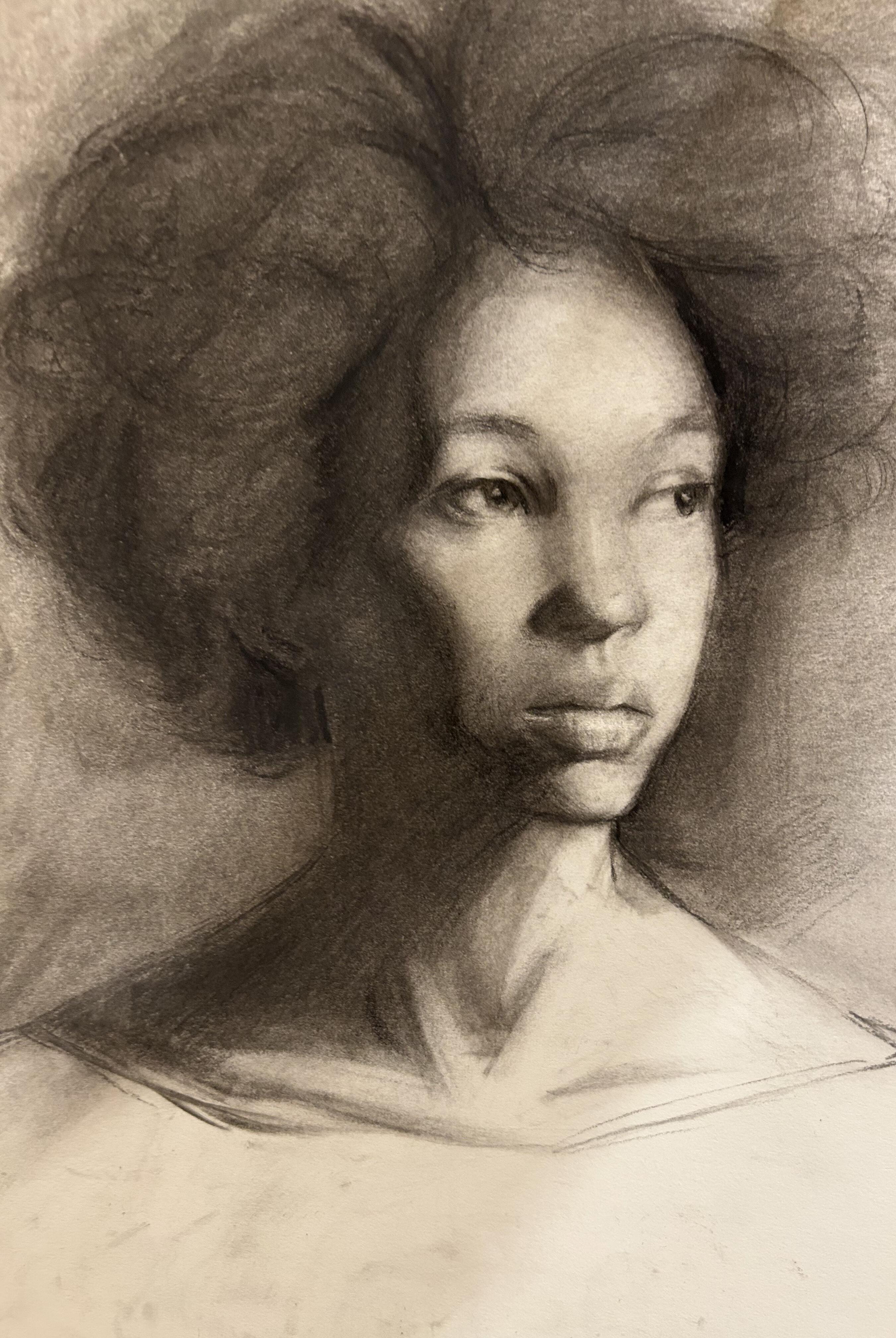

GIRL

Evie Wang

GIRL

Evie Wang

short story, EmilynTroup

While Bree concerns herself with Pete the Cat and The Magic School Bus, the struggles of the world outside her fifth grade classroom go unnoticed by her watchful eyes. All that Bree claims knowledge of lies within the wired fence of the Southview Elementary playground, where rowdy kids throw snowballs and kickballs at each other in amusement. Bree knows the Southview Elementary schoolyard like the back of her hand. She knows the sensation of dirt underneath her fingernails and snow down her back. She thrives for adventure, making mud ponds and saving worms whenever the ground is wet.

Alas, her knowle the environment that she had grown to love was disrupted in favor of an ugly red bench.

Bree joins the crowd of her growing classmates, watching as a group of elderly men in neon yellow vests and hats measure out the length of metal bars. The bench—not fully built—is obvious in its shape and design. It’s longer than Bree is, but so is almost everything.

The men ignore their gr confusion or leaving to amuse themselves elsewhere. Bree finds herself planted in place, her head cocked to the side as she waits for the men to finish.

An outburst to her left causes her to turn, where she meets the eyes of another kid. The other kid has unruly blonde hair and dirt covered cheeks. She seems as amused by the other kid’s comments as Bree is.

The girl smiles, and she is missing three teeth.

She thrives for adventure, making mud ponds and saving worms whenever the ground is wet.

Bree learns that the bench installed last Friday is a “Buddy Bench”. Her teacher tells the class before read aloud. He shares with the class that the Buddy Bench is a place for students who do not have a friend during recess. Immediately, the rest of the class thinks that this is a stupid idea. Her classmates express their displeasure in a loud outburst of chatter. Bree decides that she hates the Buddy Bench as well—if nobody else in her class needs friends, she doesn’t either.

Bree listens as her teacher tries to quiet the class. They are reading the last few chapters of The Bridge to Terabithia. Bree wants to know what happened to Leslie. Unfortunately, Bree’s table partner, John, does not understand that they have moved on from the Buddy Bench discussion. John wishes they would spend money on gym equipment instead of benches. Bree does not see a fault in his argument, but she wishes he would shut up.

She spends the remainder of read aloud glaring at John. She never learns what happens to Leslie.

She is back outside. The men have left the Buddy Bench. It is built—in all of its ugly red glory.

No student dares to go close enough to touch it. There is an invisible fiveyard radius to the bench. Any kid venturing closer than Bree stands now would be deemed lonely and sad. Bree is neither of those two things, so she stays five yards away.

At the end of recess, a dirt-covered girl slowly makes her way towards the bench. Bree recognizes her. This time, her hair is held back with two butterfly clips. When she smiles, the nub of a front tooth is broadcasted in a previously empty hole.

“It’s a dumb bench,” the girl breaks the silence. Bree nods mournfully. “I don’t even know why they would spend money on such a dumb bench. Like, nobody’s even gonna use it.”

She spends the remainder of read aloud glaring at John. She never learns what happens to Leslie.

“I know.” Bree responds. She does know.“I’m Lynn,” the girl—Lynn—presses. She is eager to talk. Bree is not used to it. “What’s your name?”

“Bree. Nice to meet you.”

Lynn smiles. She appears to be proud of herself. There is a certain level of appeal to the way that Lynn acts, with the way that she bites her tongue in confusion when she is not speaking and moves with the wind.

The whistle interrupts Bree’s train of thought, and Lynn looks disappointed. Bree cannot do anything but wave goodbye as they go to their separate teachers.

ree’s eyes linger on the Buddy Bench on the horizon. She knows that the Buddy Bench is stupid. It looks weird and it does not please Bree’s eyes. Nonetheless, she is excited to see it again tomorrow.

y she is excited, but the feeling in her stomach gnaws at her, and it is akin to something like excitement. Perhaps she’ll see Lynn again.

Bree only has to wait a few minutes until Lynn finds her at the Buddy Bench. ting at the curb, carving cartoons into a nearby snow mound with a long stick she had found when she cleaned out her locker. Bree will leave the stick outside when her teacher calls her in. She respects the schoolyard too much to steal

Lynn meets her with another lopsided smile, sitting down next to her on the curb. She talks quickly, and has already asked Bree a question before Bree could even

ou think it’s stupid as well?” Lynn asks, taking the stick from Bree’s hands.

“The Buddy Bench?” Bree says, looking over at the red bench. It is still as appealing as the day that she first saw it—which is to say, not a lot.

Lynn hums in response. Bree does not think about her answer. “Yeah, it is kind of dumb.”

“I don’t even wanna know why they made it red,” Lynn repeats, leaning forward. She cannot stop moving.

“I’m not sure,” Bree says. For lack of a better word, she wants to call it dumb again. She knows that the repetition of her response is not helpful to the flow of the conversation though.

Bree has a sudden and unsettling urge to continue the conversation, and she finds herself pausing. Her mouth is open, and she is staring at the Buddy Bench with an agape expression. She is unused to this impulse.

She almost doesn’t f watch Lynn walk away, a disappointed expression on her face as she watches a game of kickball in silence. It should not be possible for Lynn to be silent.

Bree almost has to go to recess the next day, returning to the Buddy Bench and the sight of a group of kids, who are mocking and teasing a recipient of the bench. Bree almost has to watch as Lynn sits on the red metal. Lynn will be the first and only person to sit on that bench. Bree should know, she never breaks the habit of watching the bench during recess.

Thankfully, there is a clear distinction between almost and actually.

Bree actually chases the excitement in her chest. It is strange and unusual, and Bree is nothing if not curious. She stands up, the cuffs of her snow pants brushing against each other. “Do you want to help me change the color? There’s a muddy spot on the edge of the hill that we can get dirt from.”

Lynn smiles. “We could make it brown! We’d be heroes—everyone hates that bench.”

“Then we should act fast,” Bree continues. She feels brave. She thinks that this feeling in her chest is good. She thinks that she can get used to it. “Before somebody else steals the idea.”

Especially Bree.

Maybe everybody needs at least one friend.

Trees fall into the dusk. Clouds cradle a sleepy sky. A car rumbles down the street, gasping. It seems to be running out of breath.

The sundial is faded now, its shadow fluttering against stone. The grass around it slouches against the wind. The day is not over, but the sundial sits in solitude, suspended in a moment in time.

SUNSET

Sophia Soo poetry, Bella Lasker

poetry, Bella Lasker

2:39 AM on a misty Saturday, you’ve been working all day, and you will work again Tomorrow.

The dashboard thrums with the sound of Nationalist comfort, Your cracked, sore hands clutching the worn-in leather of the truck you’ve been driving for fifteen years.

There is cold coffee in your cup-holder, courtesy of an early morning union meeting

After the fifth man in two weeks called out sick, complaining of longer hours and worse conditions. Concerns shoved aside amongst men with no other choice, you took your food and left.

Your child is asleep, but in the morning, they will wake up And be able to eat eggs and cereal, instead of their words. And above the particles in your lungs, That will be enough.

A blur of life crashes into your car, a deer—

The loud thump of impact reminds you of the time when your father hit you for talking back. The car stops, and for a gifted second, the only feeling you have is of weightlessness. Cool summer air hangs like a strange solution of sorrow: The buck weeps under your futuristic machine. It asks for mercy, and it asks for water.

Drowning eyes meet dead.

The door slams like a fist, And your frayed nerves run against your skin, Turning back was never your choice.

The guilt hangs like your arms from your limp body.

A gentle hum of the engine, and you’re home for supper.

2:45 AM on a misty Saturday, You’ve been working all day, and you will work again Tomorrow.

critical essay, Nina Krejci

David Bowie sings, “Andy Warhol looks like a scream / hang him on my wall,” but looks can be deceiving and it’s a challenge to determine if even the best forged pieces also deserve a place in the gallery. In the tapestry of the art world, Barry Avrich pulls on the thread of deception to unravel the knot of art forgery that serves as a horrid inkstain on this Rothkolike masterpiece. Barry Avrich is the filmmaker and producer of this documentary, but the real stars are Ann Freedman, Jack Falm, and M.H Miller in one of the greatest cases of art forgery in American history. A team of criminals sold more than $80 million worth of forged art, bringing into question the innocence of proclaimed victim, Ann Freedman, an art dealer involved in buying these forged pieces and selling them to clients. They each share their side of the story, trying to unveil the messy, contradicting truth. Their views are spoken almost directly to the audience of art enthusiasts, true crime enjoyers, and potential future forgers, demanding both their attention and verdict in a documentary that takes place a decade after the decades-long crime had been exposed and ended. The documentary rushes to expose the storied past of some of the most infamous art galleries in the nation and inform the public about the criminal element pervading in some of the most trusted institutions. In filmmaker Barry Avrich’s “Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art” (2020), he employs several rhetorical strategies, such as repetition and rhetorical questions, to encourage the audience in making their own judgements about art forgery and question it’s impacts on the art world.

In this case, Avrich employs the strategy of repetition, thus emphasizing statements made by Ann Freedman. The first of these instances of repetition is conduplicatio, used as Ann illustrates further important context, “No one wants to be fooled. People are fooled by art, much more than we know.” The key word is ‘fooled,’ a theme consistent with the documentary. It demonstrates, from a prominent figure of the art world, just how much fiction and lies are involved within it. By identifying a want found in all people of not wanting to be fooled, Ann connects with the audience, explaining her side of the story, and her shared desire with the audience to remain untricked. Furthermore, Freedman emphasizes her claim through her use of epistrophe, “I did not knowingly sell fakes. I was convinced. That… they were right, and real, and believable. I was convinced,” This use of epistrophe reinforces the complexities that exist in this career. In this industry, every art piece is different from the other, even if made from the same artist. Therefore, even with all of Freedmen’s knowledge, she repeats that not only was it possible to make a mistake, but that she made one too. Additionally, it also serves as an effective tool for the audience to base their perceptions on; by understanding the most pivotal aspect of Freedman’s claim—that she was completely unaware—the audience will have enough to go off for the rest of the investigation that will be led against her and her potential co-conspirators. Through this repetition, Barry Avrich sets a precedent for the audience to understand Freedman’s perspective and methodology to further help them in their determinations of guilt.

Next, through the use of strategic questions, Avrich introduces new thoughtprovoking perspectives and contrarian inquiries to challenge ideas made by the defense while allowing the audience to make their conclusions. When discussing the story told about where these mysterious paintings came from, Jack Falm criticizes the tale, and uses hypophora to make his point, “his son now wants to sell them [the paintings] at cheap prices because his son doesn’t care about money. As if rich people don’t care about money? … My experience is that rich people care about money even more than poor people.” This disrupts the story told by Galfira to Ann Freedman, by highlighting its lack of credibility through its distinct lack of logic. The idea that Freedman, an expert businesswoman, was fooled by a nonsensical and contradictory lie, makes her insistence of innocence all the more unreasonable. This prompts the audience to consider if Freedman was truly convinced with such little logical basis for the tale. In addition, Freedman uses her own hypophora when talking about how such events and situations could happen to anyone and the likelihood of being convinced by such a seemingly illogical tale: “The Director at the Metropolitan Museum was once asked, ‘How many fakes do you think could possibly be on those walls?’ - To which he responded, ‘I have no idea.’” This concept raises the fundamental doubts of these art institutions and their ability to determine reality from fiction. It also supports Freedman’s own argument by supplying another source to support her, while also adding a layer of skepticism within the audience’s understanding.

Moreover, Freedman deploys rhetorical questions when discussing the buyer’s mindset and the very specific mentality one has, impacting not only the people Freedman is selling the forgery to, but also the instances in which she herself purchased them from Glafira, “Well are you going to ask too many questions, or are you going to buy it?’ By framing the decision as a binary choice between asking too many questions and making a purchase, Freedman highlights the implicit understanding within the art community that excessive questioning may be detrimental to the sale and relationship. The use of the word “too many” implies that there is a threshold where such inquiries become futile in determining what is authentic versus aesthetically pleasing. Additionally, the question prompts the audience to reflect on their own perspectives and values. Freedman subtly urges individuals to consider the ethical implications of their actions when there are heightened amounts of unverifiable responsibility placed upon the buyer. This creates a moral dilemma, prompting the audience to understand needing to deal with the balance between curiosity and the desire to acquire a piece of art, even if its provenance is questionable. The rhetorical question challenges the audience to evaluate the extent to which they are willing to compromise on ethical considerations for the sake of possessing a potentially coveted work of art.

In conclusion, Avrich’s claim is successful through demanding the audience’s attention and engagement by repeating core ideas and posing questions that they must answer. In a situation where the truth is just as jumbled as a Pollock painting, perceptive determinations must be made by each individual. Through rhetorical strategies of conduplicatio, epiphora, hypophora, and rhetorical question, Avrich not only guides the narrative but also exemplifies the very ideals he is upholding by presenting his unique look at the criminal case and how important it is for each person to do the same. Through presenting key evidence and ideas in an educational format, Avarich implores the viewer to think critically and make their own deductions, even when nobody knows the correct answer for certain.

A child’s spirit is like a cat: if you chase after it, it will only run away faster.

Mankind breeds the strongest relation with their intuition, as an adolescent.

A child’s spirit is like a cat- if you wait in one place, you can trust it will come to you, out of love.

Cats don’t like to be held, they like to walk on their own, children always come to an age where they desire to take their own steps toward something secret.

At what age do we start to lie? In order to lie, must we know what happens if we tell the truth?

A child’s spirit is like a cat, they are both indeed liars.

A cat will squeeze its ribs into a crack it does not belong in,

A cat will hiss at a man in a mask mounting a camera,

A child will cry at the sound of a footstep too heavy,

A child’s spirit is skittish, a cat will run if you walk too fast, So approach with leisure, the felines and children will come to you.

WINTER

Matt Spaulding

WINTER

Matt Spaulding

I WANT TO TELL HER I WILL SEE HER

flash fiction, Caroline Zhang

ut she lives in New York now, where the nights blend with the moon and the moon glimmers on the road. Google Maps says she’s a twenty hour drive away, but she’s at a bus stop right now, she texts me, brushing flakes of snow off the bench. She sends me a picture of herself, squinting into the split-lip chill of the air. Wisps of her hair plaster wetly to her forehead. Her mouth crinkles against the aluminum sky.

It’s cold, colder than Pinecrest ever was, but I’ve never seen her so happy.

Her bus is due in five minutes. It’ll take her from the Upper West Side to East Harlem, her home. She’d screenshotted her apartment when she first saw it on Zillow, she sends it to me when I’m walking home from school. I squint at the brick-packed peanuts of the building in the picture. It’s nothing like our house, the one that I stand in. It’s cracked, stilted. It’s perfect for her.

East Harlem, I reply. Isn’t that dangerous?

Maybe, she says, But it’s cheap, and it’s beautiful, isn’t it?

She goes to the bank the next day to take out a loan. Her ID says she is eighteen and from Pinecrest but she tells them that she’s from New York, and they seem to believe it. Her heart beats like a child’s as the teller scrapes up her paperwork.

Her bus is due in four minutes. She’s supposed to come home for Thanksgiving break, but she has finals. An internship. A holiday concert with her friends.

She promises me, then, that we will never go inside.

I think back to last year’s Thanksgiving, when I’d barely coaxed her down from her bedroom to eat dinner. She’d been drowning, strangled with the spineheavy weight of college and scholarships and leaving on her shoulders. She sat at her desk with her door shut for most of that winter. I knew she was in there, breathing or crying, never both at the same time.

This year, her door is open wide. I can see the inside of her room. I haven’t seen it in years.

Her bus is due in three minutes. She has a job now, at the university bookstore, but she was fifteen when she got her first job waitressing. She sits in the booth after school, textbooks on the counter, manning the register with her pencil between her teeth. She says she wants spending money, that she is fine, not tired. She comes home long after the evening melts away, dropping her tips onto the kitchen table. Coins rattle into the carpet below. She never picks them up. My mother finds them, ribbed and jingling, every time she vacuums.

Once, she brings me to work when the day is slow and syrupy and our parents are stuck in it. She presses a paper bill into my hand, one of her tips. “Three of these are enough for a coffee,” she chides. “A hundred, maybe a prom dress. Isn’t that cool?”

I nod, running my nail across the paper. I wonder how many would be enough for her to come home like she used to, before the evening melted into darkness, when the sky was just fading to dusk.

Her bus is due in two minutes. She takes chemistry notes on her tablet at the bus stop. In middle school, we’d do our homework on the front porch when the weather was nice. We lived smack-dab in a ring of tiles, with cars that spin

in circles past our driveway. They roll by, one after another. They never seem to leave.

She walks our neighbor’s dog every Saturday, the mornings crisp with the tear of suburbia, and her skin becomes a mine of goosebumps against the air. Once, I ask her why she does it, and she shrugs. “He says he’s got work meetings in the mornings. And I like their dog.”

One Saturday, she opens the door to find a newspaper and an obituary, slapped across the last page. He’d left the dog to his grandchildren. There is no funeral. There is talk that he didn’t have the savings.

She wonders if he ever walked his own dog, if he stepped outside long enough to feel the goosebumps up his arms. She thinks of our parents alongside him, drenched in the slow ache of money and time, toiling away at their desks while we sit on the porch and watch the days roll by. She promises me, then, that we will never go inside.

Her bus is due in one minute. Her bus pass takes her anywhere in the city, but when I was in first grade and time melted like a popsicle over my hands, our parents told us not to leave our neighborhood when we went out to play. It’s dangerous, the real world, they scolded. You wouldn’t understand.

But we are there anyway, running valleys through the aisles of a sunsopped parking lot. The road is endless and so is the summer, and our sneakers ripple on the sidewalk in front of the Dollar General. She’s in fifth grade and she’s my older sister, so we count our change on the threaded rivers of the store’s carpet. It’s barely enough for a tube of dollar lip gloss, but it’s enough for her to leave the store brimming holy under the sun.

“Mom says dollar store makeup is bad for you,” I tell her, even though she’s ten years old and knows better than me. “You’ll get an infection.”

She swipes a wand of gloss across her lips. It glitters, clumping over her teeth.

“Maybe,” she says, “But it’s cheap, and it’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

Her bus is due to come any minute now. I’m still waiting, she texts me. I am too, but I’m not going to tell her that, not when she’s already left.

UNEXPECTED

THE OCEAN is roaring, The waves are soaring. Blue like sapphires, Where you can only admire. Beautiful inside, With places to hide. Above the water, You will not falter. Danger and beauty, And sometimes a bit moody. You cannot survive without it, But if you submit. To the pull, Your lungs will be full. With the water you admired, That looked like sapphires.

frog•ging verb

the act of undoing or reversing incorrect work, in crochet and other fiber crafts

Ihad an idea for a poem about love, and then I forgot about it

So I watered my plants instead.

Better read academics teared at her leaves, the stem, “This is life,” they said, and I said “No, this is a fern.”

And they all fell silent.

You told me to write about love but my metre was off and I couldn’t spell the words write,

In the sunlight, commas hang off the sides

So I knit you a scarf instead.

Pulling at the thread like drawling sentences

And one-star reviews

Because I don’t know how to knit, and I didn’t do it well.

I wrote a poem about love

And it was perfect, It was perfect, It was perfect, But when I draped it over your shoulders, you shivered and the snow came up to our elbows

And I couldn’t feel your hand anymore.

BORROWED TIME

Spooky things have always held a special place in your heart- the art, the music, the stories. I’ve put together some of these things about you through the noise of the world, patching them into a frankensteined tapestry. Stories of your path to discovering and expressing yourself, navigating the pitfalls and the precipices of your

How you fell in love with all things dark and gothic and macabre long before crisp February air or your words that sent a chill down my spine, but I didn’t quite

would love to have a date in a cemetery.

nobody was listening. As you stared at me with anticipation, the only thing I couldable, but creepy.” I’m not sure if you believed me when I said it, because you just laughed.

I’ll always wonder how exactly you can find impassion in the impermissible.

The morning crept by as you talked about what exactly a cemetery date would be like. Apparently, the rolling, morning fog would perfectly mirror the gray, cloudy sky; a picnic would accompany the date nicely, and we would spend our time researching the lives of those no longer living. And maybe it’s my salt-scrubbed

The sundial sits, blank under a starry moon. Without daylight, there is no shadow. Without a shadow, there is no time.

Swallowed by the hidden sun, the quotidian begins to fade. The moments blur together in the dark. The seconds merge and stick together.

As time dissipates, the mind starts to turn. Left in the night, left to wander.

poetry, Braden Greenberger

There’s something so familiar about that sting.

It’s the kind of stinging that begins at your nostrils, And progresses its way up behind your eyeballs. Calling it a sting is hyperbole.

It’s more akin to a mild buzzing, like a mosquito trapped in your nose.

It’s the smell of a time isolated to my memories.

It’s the funk of a hotel pool, The kind that plasters itself everywhere.

In the carpets, the wallpapers, the bedsheets. Days of travel and adventure

All tied together by that familiar smell.

It’s the smell of my daily life.

Every night, I feel the nostalgia return, As I fill a bucket with sweet bleach,

And begin my nightly waltz.

Mop in hand, I feel the familiar sting, Of chlorine

poetry, Zachary Schuler

poetry, Zachary Schuler

It’s impossible to stop wanting to repeat ourselves

Our lives are all in a constant state of return

Returning back to the same daily cycles

Cycles that keep us trapped

Trapping our free will in a bind of false hope

Hoping for change but never breaking out

Until you run out Of time

short story, Amara Huang

It’s ornate. It shines of milky glaze and gold clasps that click together like shoes on a floor. It’s cold to the touch, and I run my fingers into its golden grooves and it shudders open like a lion’s mouth. Two girls stand inside, cold and waiting. When I touch them, they tremble only slightly on their springs. I think they’re made of porcelain, the way their joints split in two by the glint of my desktop lamp.

I am porcelain, too, but I don’t know it yet. When Mama hands me the box, she tells me it’s from her father, her Ba. A birthday gift, from years long passed. She tells me how she loved the box when she was a child- the cranking handle, the tinkling music, the delicate golden clasp. She holds me in her hands as if I’m breakable, points to the ballerinas inside the box like they’re the most beautiful thing in the world. Mama wants me to be like them and her words hollow my porcelain skin as she tells me this, as if her wishes are her commands. She breathes hot, sour air onto my shoulder while she teaches me the five positions of dance, and I point my feet and try to shake myself awake.

I am a gazelle, long-limbed and heavy-boned, but I land like a winded hawk.

It’s not two weeks after my seventh birthday when Mama signs me up for dance lessons for the first time. She shows me videos of ballerinas on YouTube, points out the way their skirts flow around their waists while their hands point gently. I look at the girls and their effortless hands and I look at Mama, clasping her own palms with the hope that I could pirouette my way into a world just as pale and shiny as the dancers in the box. She smells of warmth and summer rain, and I can’t help but want to see her eyes widen with joy, just once. I vow that for her, I will dance- I will try.

I cling to Mama’s leg on the first day of dance and she coats my bun in so much hairspray that I might be more plastic than porcelain, and tucks herself into a corner with the other parents. It’s only then that I look around and see the other mothers and their children, wearing Sunday blouses and straw-woven tote bags, blonde and golden even in the paling studio. Suddenly, I’m aware of the way my shoulders square like barrels in my leotard, the way my fingers are bleak, yellowing, under the fluorescent lights. I wonder, fleetingly, how I can become as golden as the other girls.

Our first exercise is a sort of low, mid-air jumping split, because the entire class wants to practice grand jetés that they’re not actually ready for. One by one, each dancer takes a running start, flailing into the air, landing densely on their feet. They jump like girls and land like baby sparrows, peckish and fluttering.

When it’s my turn, I take a running head start and leap into the air brazenly, like I’m the type of animal that men wail about when their bullets miss. I am a gazelle, long-limbed and heavy-boned, but I land like a winded hawk. My feet plant hard, and I crumple forward and barely catch myself on the floor as my knees hit the ground.

That day, I learn an important lesson: that gazelles, while graceful, cannot dance.

At home, I watch as Mama calls the dance studio, asking for a refund. My porcelain box sits open, mawed, on the countertop. The girls inside it stand still in front of a little plastic mirror, and I realize their springs are screwed to the stage of the box. They are stock-straight, and they cannot move or fall. I can’t tell if I pity them or envy them.

Mama and I are flipped sides of the same coin, sewn together from either end of the universe, shared blood flowing into different rivers. I always thought that one day, when I was older, our rivers would join together and rage as one, down mountains and fields and open-mouth valleys. Mama seems to think the same, so one day, when I’m still young enough to listen to her, she introduces me to her God. She buys pocket scriptures and plastic hair clips off of Taobao and her words skin my scalp as she presses fish-bone barrettes into my hair. He, she said, was Confucius, Kongzi, a God born out of love. He, she said, loved his ancestors to the last thread of His life, that He’d dug through His roots, through time and space, to find those who’d come before, just so He could pay them his deepest respects. I cling on to her arm, silent, and she grabs me by the teeth and sinks my soul into the marrow of His lessons. Humaneness. Lawful behavior. Filial piety. She takes a highlighter to one of the pages of the scripture. ‘The parent’s age must be remembered, both for joy and anxiety’ soon roams in yellow marker, and the paper is as wrinkled as her breath when she finally nods and steps back,

and slip among the measuring cups and tablespoons of water and oil, but Mama knows each ingredient by heart. It’s my father’s favorite recipe.

When we serve dinner later that evening, I collapse into a chair, my knees aching and raw. I imagine this, like clockwork, every night until my bones

SOFT SILK Evie Wang

As she is speaking, Mama twines at the box on my desk. Cranks its handle in a spiral coil. The porcelain girls inside begin to spin, etch by etch. Music creaks out of the side and I watch it, unblinking, long after the handle stops winding and silence bounces off the walls.

It’s not even a week into my junior year when a shuddering dam splinters, rattles, and breaks. A girl I’ve known since fourth grade but never really spoke to sits next to me in history and draws stars on the corners of my papers. She’s got braces- I first notice them when I hear Her laugh. I haven’t seen them before, not in the years I’d known Her or the minutes we spoke. Everything is therethe metal brackets, the little hooks, the rubber bands clinging onto them like miniscule lifelines, threatening Her to silence, and she still speaks as freely as if no one is listening.

Quickly, selfishly, I wish that those bands would keep Her mouth closed, if only so I could turn away from Her gaze.

Our hands intertwine and race into the ground.

When I tell Mama, she snorts. She tells me she’s proud that I made a friend. I’m happy, almost relieved, when Mama says that. I cup Mama’s compliments to my ears the next time I see Her, to stop the starry limbo of my heart against my ribcage. My fingers have begun to dance lately, fiddling with my backpack straps, my pencils, the handle of the box still perched on my desk. I crank it so many times that the little ballerinas spin and spin and spin and I can soon recite their melodies by heart, like a broken, splintering record.

She comes over to my house one day, to watch a documentary for class, and we collapse into a beanbag chair under a blank, starry moon. The movie is long-gone and the night is waning, and Her arms stretch towards my ceiling like a willow, luminescent against my side. Everything is stifling in the dark- the heat in my face, the blankets on my bed, the wind batting against my windows. I feel a tug on my sleeve, the pads of Her fingers in my palm. I wilt, I open.

Our hands intertwine and race into the ground.

We lie there, curled together like fingers in a fist, and that’s how Mama finds us, with my palm in the quicksand of her grasp. Mama doesn’t hit me. But she splits my lip open with her gaze, shoves my hands onto the kitchen counter, guts my being like fish bones from flesh and shuts the door. Desperately, she screams that I was not meant for this. She cooks dinner that night and doesn’t skin anything, as if the splinters of her cutting board had finally caught up with her fingers. She tells me, desperately, that I am just like her, caught in the confines of a country that does not love me for who I am, a vessel that hinders me from who I was meant to be.

I think she is right.

In my bedroom, I stare at my pitted eyes in the little mirror of the music box. The ballerinas spin in front of it, but I never really paid it much attention. It glares at me now, in the sunlight, reflecting a gaze it has seen a million times before.

Quietly, I press down on the porcelain lid, the painted flowers that spread like china ink over parchment. The clasp tries to click in upon itself, but the ends don’t fit together, and they collide into each other as I try to push it closed. The ballerinas stand inside, upright and unyielding. I let go of the lid and the box springs open, once again.

Translations:

Grand jetés- a type of advanced ballet leap

Taobao- a popular Asian shopping website

Baobei- honey, dearest

Tongzhi- queer

Kongzi- Mandarin phonetics for Confucius

In one year, if I’m still around, I’ll show you the way. We’ll hold hands and fly together, and we’ll fly into outer space because we both know better than anyone else that there is no more ‘happiest place on Earth.’ Mama keeps telling me that you’re in a better place now, that you’re up there in the sky playing Mario Kart and Go-Fish like we used to do together on my couch. Maybe you’re having fun. Maybe you’re floating around eating freeze-dried ice creams, like the astronaut program we used to watch, back when the only space we needed was my living room.

But I’ve got a better idea. Go on a journey, with me. Our space odyssey will take place at the local neighborhood pool- I swear if you squint hard enough, the little bubbling reflections at the bottom of the pool that rivulet the sunlight look just like blazing galaxies. We’ll play that game where you hold your breath underwater for as long as you can until you’re seeing stars and your head starts to swim. And our heads breaking the surface of the water, gasping for air, will be all we have to do to breathe again. We’ll bob there for a minute and dive right back in, because I know you’ll want to keep going. I’ll let you win this time around, even though I know I can hold my breath for longer. I’d press time into your palms like glue, anything to keep us infinite.

After all, we have so much left to explore.

SIGNS OF LIFE

Caleb Hirschuber

The fire kills me, but the warmth keeps me alive. The fire stings my skin numb, leaving behind a perfect bruising, but the warmth heals the inner child who begs to come in from the cold. The child who spends so many long nig hts, bent against a locked door wondering what they did wrong The flames release something inside, letting forth screams and cries of bitter anguish while the warmth unleashes dopamine. There is an infinite cycle found only within fire too often overlooked by the comfort sent to

my heart

Yet, the flames yell back, burning away more skin and losing more life, And now, I’m not screaming, but I’m surrounded by it. I’m surrounded by the physical pain, but also the liberating mental relief.

The pull-and-push method or The tug-of-war rope

A ceaseless battle of internal conflict, Why does pain dangle peace right in front of our eyes? How does peace bloom in a place of such pain?

Staring into the mirror, Hoping for inward reflection, Yet only hitting the surface

“Go to bed,” you hear a distant voice call

Is that real? Or perhaps my just own?

“How can that be?” you ponder,

“I like it here” “I don’t want to leave”

The minutes pass as you watch yourself, Waiting, Hoping for a slight fracture in the copied movements

Waiting for the reflection to tell you the truth

When all you can tell yourself is lies

Does it want something?

Does it need something?

You don’t know

So you don’t ask

Because if you do, you won’t know how to answer yourself

It’s hard to be alone you decide

When the silence takes over, How can you ever hear again?

When the room gets dark, How will you ever find the light?

*this is a contrapuntal poem, which means it can be read 1) down each column or 2) straight across the page.

Evie Wang

Evie Wang

FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL

Megan Smith

FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL

Megan Smith

short story, Thea Oberg

Kimberly wants nothing more than to just close her eyes, and let the gray space wash over her. And as she sits in her car, in the parking lot of her high school, she lets herself close her eyes for a moment. A car pulls in across from her space, and she opens her eyes. When she sees the driver is her best friend, she gets her bag and drink and walks toward it. “Oh hey, sleepy head!” the best friend says when Kimberly gets to her.

“I’m actually so tired,” Kimberly says. “I was up so late, doing stats homework. I wish I hadn’t taken any of these annoying smart classes.”

“You’re fine.” her best friend says, pushing her forward to walk into school.

“You’ll see when you’re a senior. I want to go to college so bad. I don’t know how much more of this I can take.”

Kimberly drags her feet, walking to her favorite teacher’s office. The teacher isn’t there so she sits down in the chair by her desk. She picks at the fabric until the teacher arrives. “What did you want to talk about, Kimberly?” The teacher asks.

She spends her nights behind windshield wipers or with her head on a pillow. It doesn’t feel lke any time passes between those things.

“My college applications, can you just read this?” Kimberly hands some documents to her, then puts her head down. Her teacher reads them slowly, making critiques in the margins. “Thank you,” Kimberly says after they’re done. She drags her feet as she walks back to class.

After a couple of weeks, Kimberly has sent out every

application. She’s constantly restless and doesn’t sleep through the night anymore. When she wakes up in the night, she does homework. The notes are endless, and she cries while she does them.

The applications weigh on her for weeks, she spends her nights behind windshield wipers or with her head on a pillow. It doesn’t feel like any time passes between those things.

She feels like her body is enclosed in a box, her ribs tight, and her elbows locked at her sides. She doesn’t know what there is to do. She feels stuck in time, in a place she cannot yet leave, but she can’t stay either.

On an evening in early March, she receives a letter from a college. We regret to inform you... She throws it in the trash and gets her coat and keys. She looks at her house as she pulls out of the driveway, the only light on is her parent’s. She knows it’s her dad awake, he is always up late. Kimberly stops the car and contemplates going and telling him everything, curling up in his bed and telling him how small she feels, how she feels claustrophobic in this dumb town. He would understand. But she instead drives down the road.

She pulls out of her neig hborhood and onto a main road. No one is out driving on a late tuesday night. The roads are still icy from the last snow, but she continues to speed up as she gets on the freeway. All she thinks about is the act of driving, not where she’s going.

By the time she is in the city, it is past midnight. Now other cars are around her, city people. She rolls a window down and lets the city air in. She turns her music up, and lets the city mix itself into her. She parks in an old empty lot and gets out of the car. She doesn’t feel scared like she usually would in a city at night. She carelessly walks around in a city she wished she lived in, and the bubble that she usually feels trapped in melts. She watches the apartments as lights turn off, and imagines herself in one of the little lit-up boxes on a building.

She turns the music up, and lets the city mix itself into her.

But every perfect moment is only followed by something less. Around 2am, Kimberly gets back in her car, and gets back on the freeway. The drive back is harder, she really feels the ice threatening her beneath her wheels. At one point, back in her little town, she loses control of the car and almost swerves off the road, but she doesn’t. She pulls back into her driveway, and feels a quiver in her chin. Every light in the house is off.

The heaviness is back, and the bubble too.

She stands on the welcome mat, looking upon her house, and she knows that her bed is upstairs awaiting her.

After all, we have so many galaxies left to explore.

- Odyssey, Noelle Madden, pg. 94

SUNDIAL was printed by Smartpress Printers in Chanhassen, Minnesota, using digital printing technologies. The book is perfect bound.

Titles, headings, and and artistic credits were created primarily using the Brittany Signature, Darks Calibri Remix, and Binary ITC font families. Body texts and quotes were designed using the Lora and Montserratt font families.

75 copies of the magazine were printed and distributed to educators, administrators, and students of East Ridge High School. A digital release was published on FLIPHTML5. Additional copies of the magazine may be purchased for $16, subject to availability. 100% of profits made from magazine sales will be contributed to the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, aiding scholarship funds for underserved youth participating in their summer K-6 Art Programs.

Staff members of The Fine Print volunteered over 50 combined hours at Concessions Stand Shifts in collaboration with the East Ridge High School Athletics Department, raising funds to support the publication.

The mission of the Fine Print is to highlight the artistic voices of our vibrant school community. We encourage submissions of prose, poetry, visual art, ceramics, sculpture, and photography from the student body. Submissions are also nominated via teacher recommendation.

Works are selected for publication by the editorial staff. Pieces are evaluated based on their originality and emergence of personal voice. To ensure a fair representation of every submission, student names are removed from all works during the editing and selection process.

The Fine Print 2023-24 Staff

Editors-in-Chief

Caroline Zhang, Nina Krejci

Illustrators

Evie Wang, Sophia Soo, Addison Truckenmiller, Sarah Yu

Visual Art Editors

Evie Wang, Sophia Soo

Writing Editors

Bella Lasker, Braden Greenberger, Caroline Zhang, Duajong Chang, Idman Loyan, Maia Nguyen, Matt Spaulding, Nina Krejci

Layout & Design Managers

Caroline Zhang, Matt Spaulding

Advisor

Adam Hayes

The Fine Print was established just last year in October 2023. Since then, we have released two complete issues of the magazine, featuring over 100 works of student art and writing - something we could not have done without the incredible support of our school and local community. We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to…

Ms. Kennedy, Administrative Assistant; and Ms. Helmbrecht, Dean of Student Support; for supporting us in every fundraising endeavor and providing us opportunities to grow and fund our publication. Thank you for answering every email we sent about concessions and letting us run down to ask questions during passing times.

Mr. Nagahashi and Ms. Rascher, for guiding us in the printing and magazine layout process. Thank you for teaching us how margins work and making sure we didn’t cut out half the artworks in print.

Mr. Hayes, who has supported us, guided us, and encouraged our muses and endeavors since day one. Thank you for believing in us and our ideas, and being the voice of reason we needed along the way.

Jim and Joe McDonough of Carbone’s Pizzeria in Woodbury, for their generous sponsorship of our publication.

Students Bella Lasker, Evie Wang, Idman Loyan, and Maia Nguyen for their invaluable time and efforts they have dedicated to working concessions.

To the incredibly talented students who sent in their art or writing for this issue of The Fine Print - thank you for trusting us with your work, with a glimpse of your remarkable ideas and experiences.

And finally, you, the reader, for your unyielding support of our publication. We will continue to share student work for as long as there is an audience, and we couldn’t be more grateful for the support we’ve received.