Using art as a tool to develop G2 River Park project

ART AND CULTURE CONCENTRATION

Rueichen Tsai

Department of Urban Planning and Spatial Analysis, University of Southern California

PPD 629: Capstone in Urban Planning

Professor Deepak Bahl

March 2, 2023

Project Site (from capstone instruction)

Taylor Yard G2 opportunity site is located in the Northeast Los Angeles neighborhoods of Cypress Park and Glassell Park, and surrounded by the neighborhoods of Atwater Village, Elysian Valley, and Lincoln Heights. It is bounded by the LA River to the west, Rio de Los Angeles State Park to the east, the State-owned Taylor Yard G1 Bowtie parcel (G1 parcel) to the north, and the active Metrolink Central Maintenance Facility (CMF) to the south. See Exhibits 1 - 6 for project site and context.

The 42-acre G2 parcel was a part of the 244-acre former Taylor Yard rail complex, owned and operated by Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) and its predecessors for rail maintenance and fueling from early 1930s to 2006. Until 1973, the facility serviced nearly all freight rail transport in and out of downtown Los Angeles. Taylor Yard was divided into ten parcels and these parcels have been developed for transportation facilities, industrial buildings, and residential, institutional, and commercial uses. Parcel G, previously known as “Active Yard,” was subdivided into two parcels (G1 and G2), and closed for operations in 2006.

Due to its historic use as a rail yard, the project site is a designated brownfield and is under Department of Toxic Substances Control’s (DTSC) regulatory authority. The City plans to work with DTSC to develop appropriate remediation approaches for future site uses that may include Soil Removal and Disposal, Engineered Cap, and Soil Treatments. For the purpose of the capstone, please assume that the project site is ready for development.

Three rail stations are in close proximity of the project site. Heritage Square and Lincoln/Cypress stations along the Metro Gold Line, and the Glendale Station served by Metrolink (Antelope Valley and Ventura lines) and Amtrak Pacific Surfliner are within two miles and all of them located on the east side of the project site.

Previous effort to privately redevelop the project site into industrial uses in the late 1990s was unsuccessful. The plan comprised of having two large industrial warehouses with paved parking lots over the entire site.

The project site is located within Los Angeles City Council District 1, currently represented by Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez; and Los Angeles County Supervisor District 1, currently represented by Supervisor Hilda Solis.

Spatial Analysis

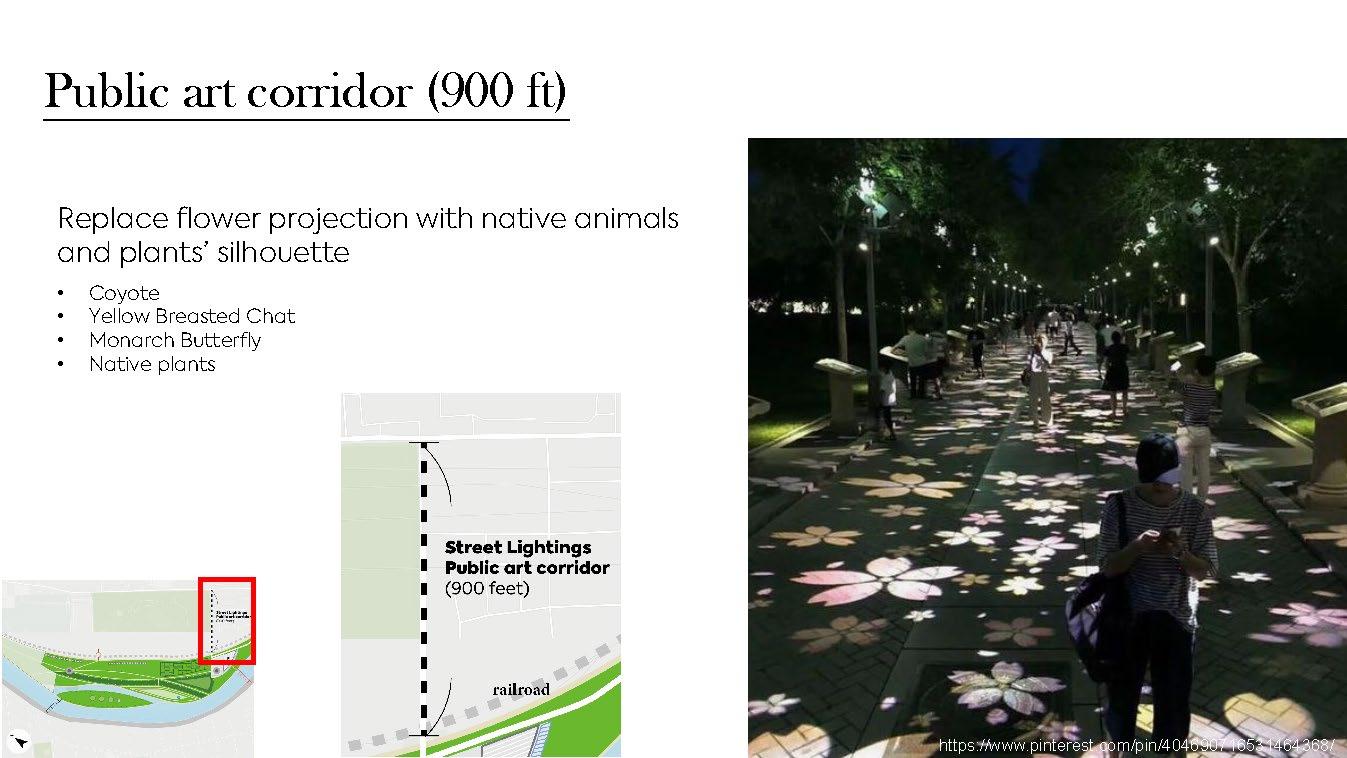

Street Lighting

The Taylor Yard G2 River Park Project site is geographically isolated, bounded by the Los Angeles River to the west and railway to the east (see Figure 1). One of the ingress/egress routes of the project is a private access roadway that one must enter through from San Fernando Road to the south end of Rio de Los Angeles State Park; another route is from the Taylor Yard Bikeway & Pedestrian Bridge. For Rio de Los Angeles State Park and future G2 park-users, the feeling of safety when accessing the parks during nighttime is important, given that 21% of park-goers go to the parks in the evenings, as shown in the G2 project community survey (Bureau of Engineering, 2018, p. 7). In addition, the closest police station is located on 3353 San Fernando Road, around two miles away from the ingress/egress point on San Fernando Road (not included in Figure 1). Although the pedestrian bridge is equipped with lighting, it does not adequately target the access route to the project site from San Fernando Road. As such, working with private property owners to install street lighting is important.

Dataset retrieved from the City of Los Angeles

Transportation

Metro Bus

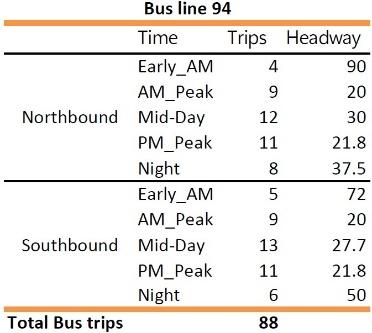

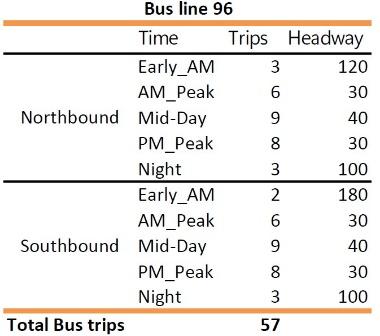

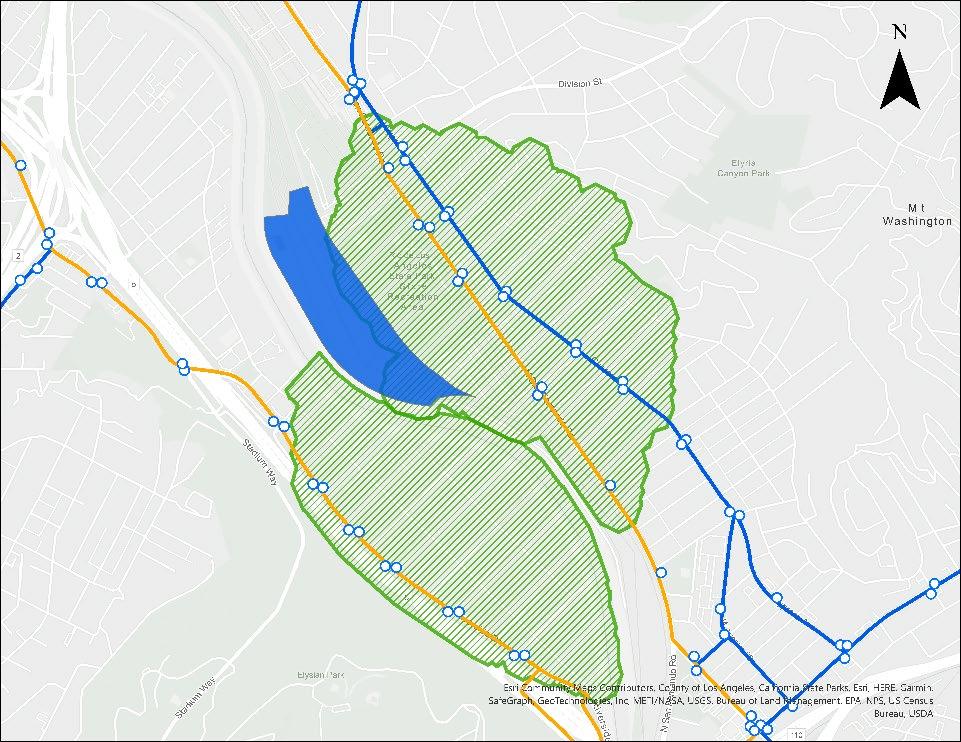

As mentioned above, the project site has limited access. That said, the project site is accessible and convenient by bus. There are 39 bus stops within a 15-minute walkshed of the project as shown in Figure 2. There are two bus lines that are the nearest to two ingress/egress routes of the project site. Metro bus routes 90 and 94 are located on San Fernando Road, on the Project’s east side; route 96 is located on Riverside Drive, on the Project’s west side. The 90, 94, and 96 bus’s average headway between morning and night peak rush hours on weekdays, are 20 minutes, 23 minutes and 33 minutes, respectively. On weekends, headways are 27 minutes, 20 minutes and 59 minutes, respectively (see Table 1). Considering that the bus 96 makes 57 daily trips alone, and the total combined daily trips for busses 90 and 94 are

186. As a result, future visitors to the future G2 park should expect traffic congestion to some extent.

90 & 94 & 96

Note. Dataset retrieved from LA Metro Rueichen Tsai, 2023

90 94 96

Note: Dataset retrieved from the City of Los Angeles

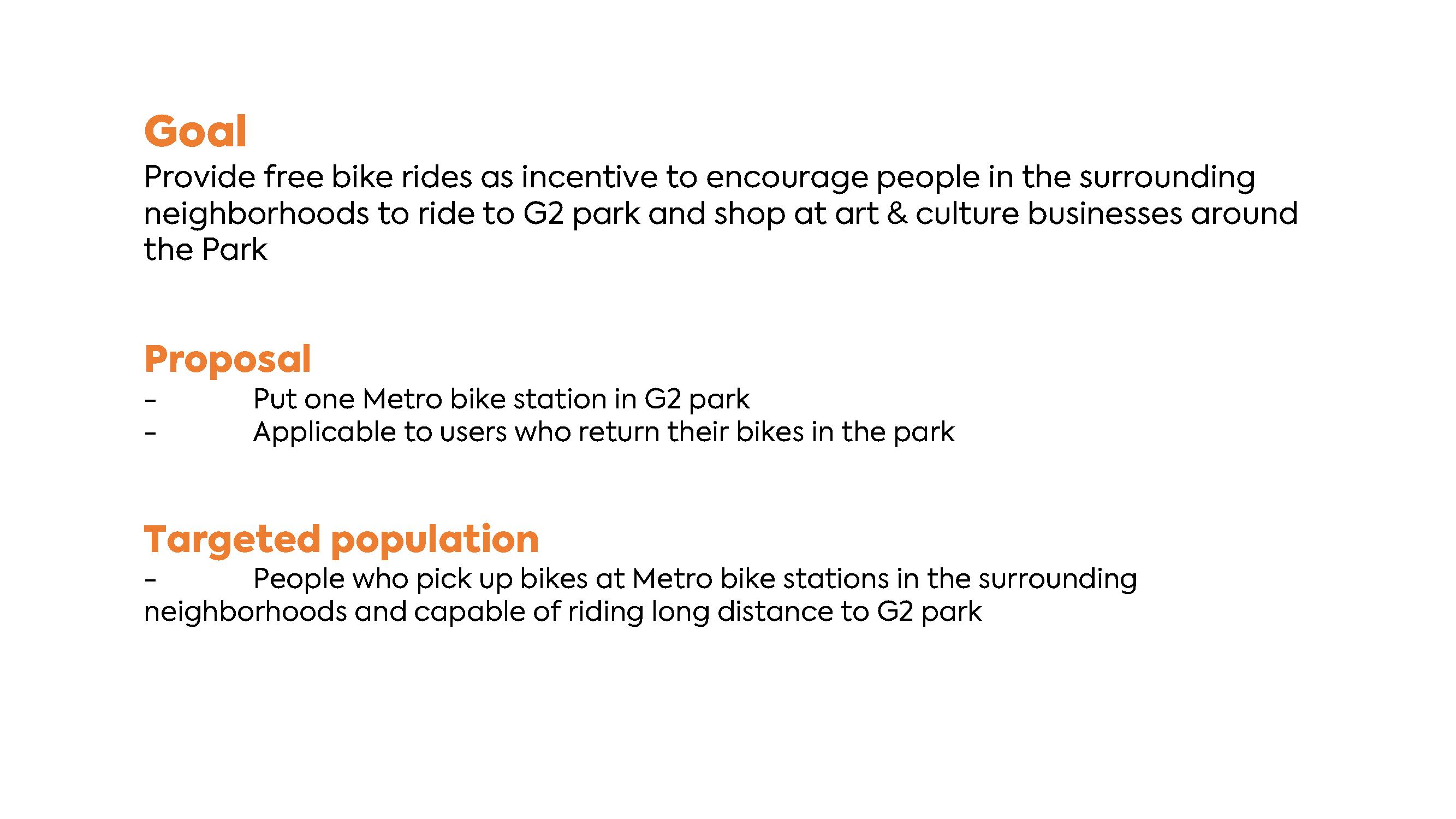

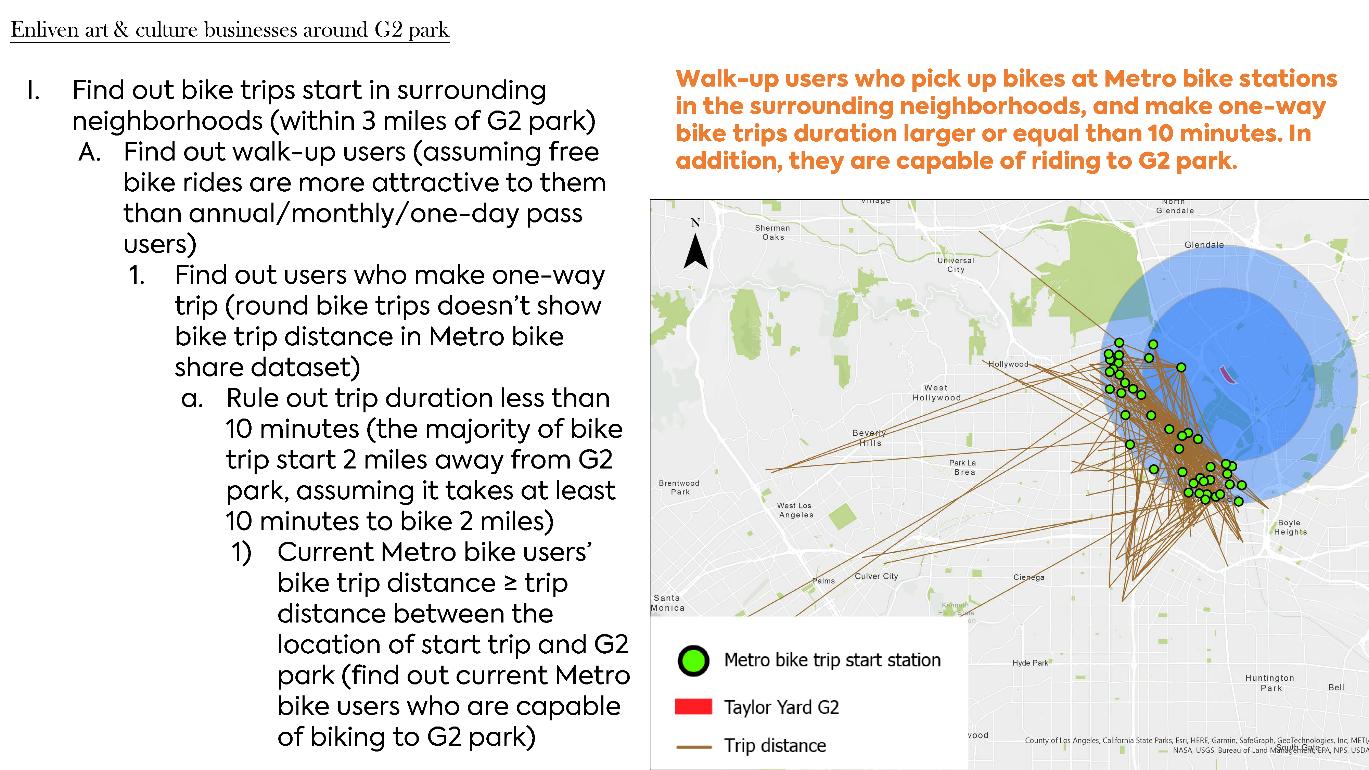

Metro Bike share analysis

Please see the “Metro bike share analysis” in appendix for a detailed analysis.

Demographics and Social Equity

The G2 land parcel is surrounded by the three Hispanic-majority neighborhoods of Elysian Valley, Glassell Park and Cypress Park (see Table 2). Among these three neighborhoods, Cypress Park experienced the largest population drop in Los Angeles between 2010 and 2020, with a decrease of 1,258, about 13% (Zahniser, 2021). Additionally, Cypress Park has the second lowest minimum median household income, which indicates that residents in Cypress Park are more susceptible to economic impacts such as high inflation rates (see Figure 3).

Note: Dataset retrieved from U.S. Census Bureau

Note: Dataset retrieved from U.S. Census Bureau

Note: in U.S. dollars

Unemployment rate and Education attainment

Rueichen Tsai, 2023

Rueichen Tsai, 2023

Education attainment in the surrounding neighborhoods of the G2 park location is considered high, generally speaking, in comparison to the city of Los Angeles and Los Angeles county as a whole.

Note: Dataset retrieved from the U.S. Census Bureau

Rueichen Tsai, 2023

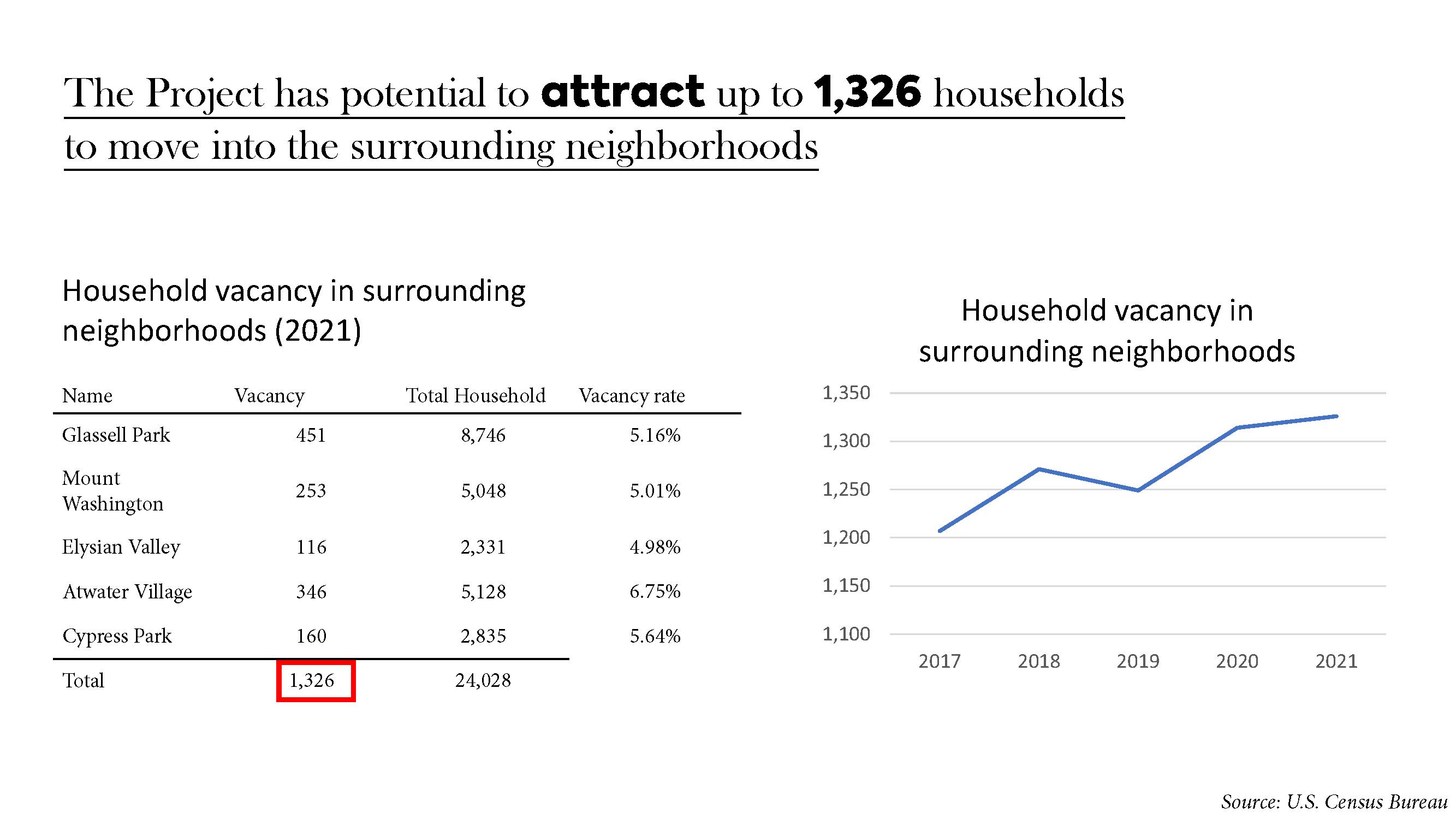

Renters in the surrounding neighborhoods and household vacancy

The Taylor Yard feasibility report (2021) points out that parks can increase property values in the surrounding communities. The report also indicates that 95 condominiums (41 of which are within 500 feet of the project site) in the surrounding communities can expect a 5 percent increase in property value after the project is completed. The increase in property values would bring addition property tax revenue to the city of Los Angeles. Moreover, 5 percent increase is only a conservative estimate, the effect could extend beyond 500 feet away from the Project site (p. 9.212) Although the city can benefit from the additional property tax revenue, the increase in property values is a doubled-edge sword. More than half of residents in the surrounding neighborhoods are renters (see Table 4). Renters are the most vulnerable population to environmental gentrification When buildings are sold, rent increases and people are evicted, tenants are pushed out. Please see the “Household vacancy” in appendix for a detailed analysis.

Mount

Rueichen Tsai, 2023

Furthermore, the existing renters who are rent-burdened are the most vulnerable population who will be impacted by the increase in property values (see Table 5) as their rents are typically based on home value. They could be driven out of the community any minute after the project is built because of green gentrification. Some landlords stick to the 1% rule, where they charge rent based on 1% of the total home value; some charge 0.7% to 0.9%. As home values increase over time, renters need to pay more for rent to live in the community. Home values in the project site’s surrounding have been steadily increasing as indicated in Figure 4. Renters in the area might experience a larger increase in rent after the project’s completion, due to increases in property values brought by the project.

Note: Dataset retrieved from the U.S. Census Bureau

Rueichen Tsai, 2023

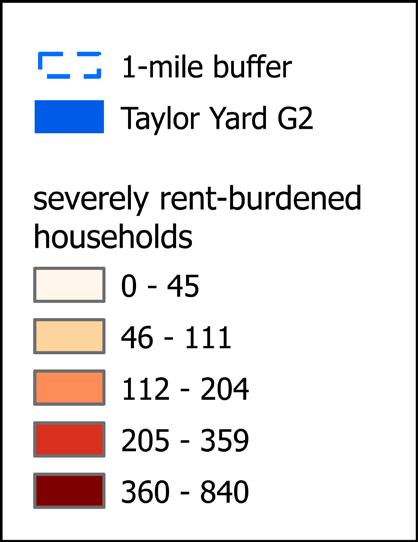

There are 2,306 severely rent-burdened households located within one mile of the project site, 923 of which are within 15-minute walkshed of the project (see Figure 5).

Note: Dataset retrieved from Zillow Housing

Rueichen

Note:” ZHIV is a measure of the typical home value and market changes across a given region and housing type. It reflects the typical value for homes in the 35th to 65th percentile range. Available as a smoothed, seasonally adjusted measure and as a raw measure.”

Cultural asset mapping

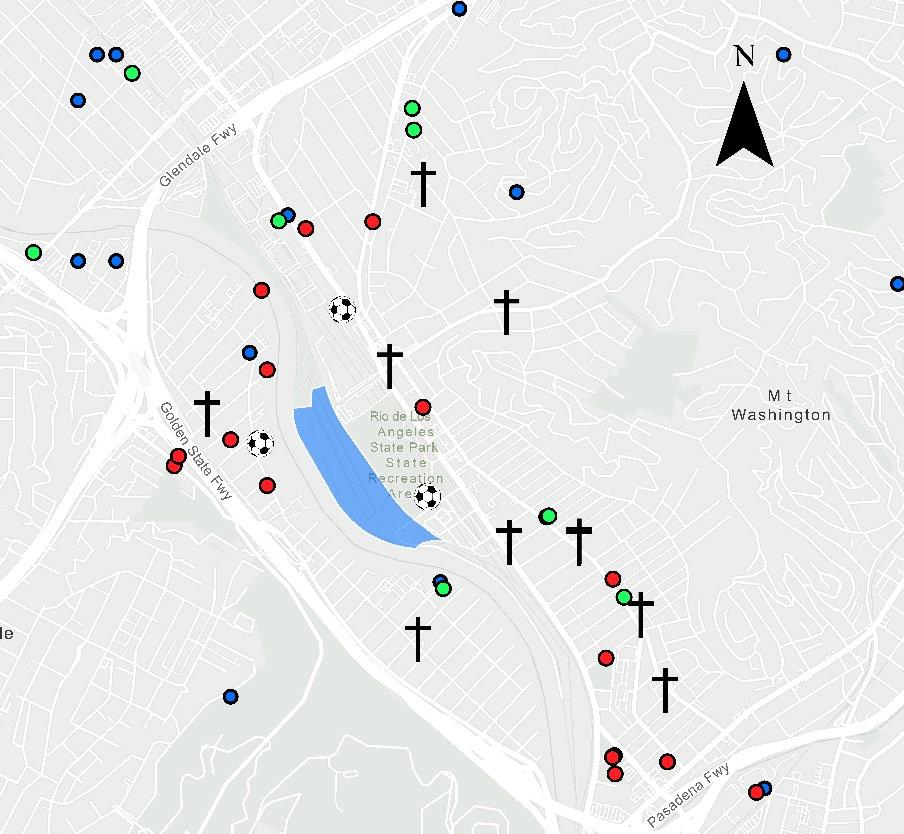

A Community Capital Framework (CCF) (Emery & Flora, 2006) examination shows that the communities have abundant art and cultural amenities that contribute to fostering energetic social life. There are 9 art galleries/artist studios near the Project, allowing the communities to have great opportunities to be exposed to art. In addition, as shown in the client brief presentation and other community meetings, the surrounding communities have expressed an ardent passion for soccer activities. The following cultural asset map shows three soccer fields concentrated in the Rio de Los Angeles State Park addressing the communities’ interest in soccer. Please see the “Cultural asset mapping” in appendix for the list of cultural asset and artists based in the local community Figure 7

Although the surrounding communities have easy access to art and cultural institutions, there are very few public art installations around. There are only two public art installations along the Los Angeles River created through the LA River Public Art Project (Western States Arts Federation). However, The 4th Tree and Sticks are barely recognizable to the public.

and programs

Art and phytoremediation intervention

According to the community survey in the Implementation Feasibility Report, the local community are mostly interested in having access to nature and doing nature-related recreational activities, such as biking and hiking, followed by cultural events and art. According to the presentation given by an engineer from Bureau of Engineering, City of Los Angeles, the local community had been expressing concerns regarding soil remediation, given that the G2 parcel was part of an active railyard and had accumulated harmful chemicals over the years. Additionally, the Client Brief presentations of Taylor Yard G2 park project we’ve watched in class also showed that almost all of the community attendees voiced their concerns regarding soil contamination and the transparency and effectiveness of the site remediation process Those concerned advocated for a complete and thorough chemical removal, even though the environmental laws in Los Angeles require sites only should be cleaned up to a certain acceptable level where residual chemicals won’t do harm to human health.

Building upon the findings of the community survey and attempting to address community concerns around soil remediation, I propose a knowledge and engagement-based art phytoremediation workshop that could help the local community gain a better understanding of phytoremediation and help ease the tension between the stakeholders – the local community and people who represents the City of Los Angeles working on G2 project. This

proposed program will invite two artist who have experience integrating soil remediation into their artistic praxis. The artists, Lauren Bon and Frances Whitehead will remake their site remediation practices in the surrounding neighborhoods of G2 park. Lauren Bon integrated soil remediation into one of her art programs titled Not A Cornfield. This program lasted about one year, from March 2005 to May 2006. She cleaned up the former railyard (today Los Angeles State Park) by replacing the soil on site with 1,500 truckloads of clean soil, planting 30 thousand pounds of corn seeds and harvesting said corn after an agricultural year (Bon, 2005). Throughout the course of this project, Bon partnered with local community stakeholders and organizations to hold community workshops, meetings, and live music event related to the project. This project attracted more than 33,000 visitors between 2005 and 2007. After the cleanup, Bon returned the cleanup site to the City of Los Angeles. The project funding of 3 million dollars came from the Annenberg Foundation. The second site remediation art program, SLOW Clean-up, was originally launched by artist Frances Whitehead to clean up 8 abandoned gas stations in Chicago, Illinois. This project lasted for 4 years, from 2008 to 2012, and identified 12 new native plants as petroleum remediators in Chicago (Whitehead, 2008). SLOW Clean-up was a program that encouraged people to be actively engaged in the process of site remediation and held community workshops to provide educational opportunities for community members and students to learn about the role of native plants in soil remediation.

Although the Taylor Yard G2 project team from the City of Los Angeles has held meetings to inform the ways in which the Bureau of Engineering partners with environmental specialists to dealing with the G2 parcel brownfield issue, the concerns still hold the community back. In my view, the community meetings about site assessment and soil remediation held by the city are a one-way form of civic engagement, in that the Bureau of Engineering did a good job in providing informative analysis and suggestions to the local community, but the community is only a receiver rather than actively involved in the remediation process. My proposed phytoremediation art program for G2 project will focus on civic engagement that provides educational opportunities for the community through being actively involved in the site remediation. The program has five primary goals:

- Teach community about potential native plants in G2 parcel or Los Angeles that can served as soil remediator (considering that G2 parcel is contaminated with multiple chemicals)

- Identify local environmental issues led by poor soil remediation

- Engage in critical thinking about using other methods for site remediation

- Working with two artists in participatory art projects

- Develop ways to better communicate with public agency and other stakeholders at large

Heritage tourism

In the Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration of G2 project, the Bureau of Engineering (2014) points out that there are no historical and archaeological sites on the project site and within 0.5-mile radius of the project site according to the cultural surveys they conducted (p. 38). They further indicate that:

Given the location of Taylor Yard Parcel G2 in the Los Angeles River flood-plain, it would not have been a primary location for an aboriginal village or a camp.

Therefore, historic resources from these villages are unlikely to occur on the project site (Bureau of Engineering, 2014, p. 38)

However, the project site has a rich historical background of Native American It was part of the areas that the Tongva people resided in over 200 years ago. The area was used by the Tongva people to search for food, water, and spiritual sustenance. Furthermore, the land was subdivided into multiple parcels in the 1800s, of which a 247-acre lot (today Taylor Yard) was purchased by J. Hartley Taylor and was used for growing oats, barley and served as a hog farm (Guild, 2022). In addition, an online interactive mapping project about Tonga villages Mapping the Tongva villages of L.A.’s past, states that the closest Tongva village to G2 parcel was called Yannga village (Sean Greene & Thomas Curwen, 2019)

As a result, I propose an on-site cultural tour which takes place in the park for local communities and visitors to understand the rich historical background of the project regarding the original people of Los Angeles, Tovaangar. The cultural tour will accommodate 30 people at a time and take visitors walking along the Tongva Boulevard (see site plan for the location). Two types of cultural tours will be provided. The first type of cultural tour will introduce the historical context of the Tovaangar who lived and thrived in the area hundreds of years ago, and will include their living habits, how they search for food, etc. The first type of cultural tour aims to give an overview of Tovaangar and will last 30 minutes led by a tour guide who completes cultural tour guide training offered by the museum I propose for the G2 project The first type of cultural tour will specifically focus on Yannga village, the closest Tonga village to the project site. The second type of cultural tour will last an hour to take a more in-depth look at the Tongva villages in Los Angeles, which includes highlighting the differences between each Tongva village and the reasons that make Tovaangar reside in different locations in Los Angeles. Most importantly, tour guides in the type II cultural tour will provide their insights on Tongva tribal cultural from the perspective of cultural researchers. The second type of cultural tour will be led by people who have background in history or expertise in Tongva tribal culture. They should be able to answer more challenging and detailed questions brought up by the visitors.

Partnering with nonprofit arts organizations

It should be noted that there are seven nonprofit art and cultural organizations within 1 mile of the project, include performing arts, education, and civic engagement organizations. I propose a partnership program that takes advantage of the project site’s proximity to these organizations and work closely with them to develop diverse festivals and events in the G2 park seasonally. the program will focus on developing a long-term partnership with these organizations, including the Elysian Valley Arts Collective, Adam’s Forge (blacksmith community), MashUp Contemporary Dance Company (performing arts company), Artes Vocales (chorus community), Women's Center for Creative Work (feminist community), and Clockshop (public programming studio). These organizations work to cultivate community in the area, such as the The Elysian Valley Arts Collective (EVAC) which aims to create a sense of place for the local community and revitalize the Los Angeles River. My proposed program is to invite EVAC to conduct educational tours walking along LA River with visitors and the local community and teach them about LA River history. The proposed program also includes inviting MashUp Contemporary Dance Center and Artes Vocales to the park to do the performance. The proposed program not only creates a win-win collaboration between local

nonprofit art organizations and the G2 park authority, but also brings pleasure and increases in quality of life to the community and visitors.

Enlivening arts and cultural businesses around G2 park

The role of art and culture in the city can be divided into three categories: boosting local and regional economic development, enhancing aesthetic value of the built environment in the city (public art installation), and leisure activities/amenities (festival/event/concert). Art and culture raises economic development in the city through job creation, increases in government tax revenues, and promoting tourism. For example, job creation can be achieved through hiring workers for museums, non-profit art organizations or art galleries/artist studios. Arts and culture make the city a more desirable place, thus attracting people to move into the city to work and live, as well as attracting businesses to the community. Consequently, the state government can increase its tax base by collecting additional personal income tax from those people who move into the state, and employment taxes from businesses. In order to attract more arts and cultural related businesses and organizations to move into the community around G2 project, I propose a program that uses the G2 project as a tool to develop a cultural cluster. To incentivize art and cultural-related businesses such as art galleries, or nonprofit art organizations move into the community around the project, my proposed program provides a property tax return if they locate their physical operations sites within 1 mile of the project. The property tax return rate they can receive is dependent on the distance between their physical operations site and the G2 project. The return rate 0.5 percent, 0.4 percent, 0.3 percent and 0.2 percent corresponding to 0.25 mile, 0.5 mile, 0.75 mile and 1 mile away from the project site.

G2 River Park Biennale

See appendix for further details.

Controversy around placemaking

Placemaking as a concept of revitalizing the community has been widely adopted by policy makers, planners, real estate developers, and artists in different context. By definition, “[p]lacemaking is the process of creating quality places that people want to live, work, play and learn in” (Wyckoff, 2014, p. 2). Placemaking can be realized as a physical environment improvement related to beautification, thus bringing pleasure to people who live in the community. It is a context-specific intervention used for building the sense of belonging through various activities and events. However, with the various types of placemaking strategies, there are a variety of relevant controversies.

Placemaking & Gentrification

Three types of placemaking are identified by urban scholar Wyckoff. Strategic placemaking, creative placemaking, and tactical placemaking. First, strategic placemaking focuses on creating quality places that attract talented workers to move in and live in the community through consumption amenities, thus contributing to job creation and income growth by attracting businesses whose targeted customers are primarily talented workers (Wyckoff, 2014, p. 5). This type of placemaking focuses on creating green spaces, animating public space through physical improvement, and integrating human-centered design into the built environment. Enhancing accessibility to recreational activities such as museums, live music events and pedestrian-friendly environments is common practice in this type of placemaking strategy. Adding green spaces, creating bike paths, and pedestrian-friendly built environments are instrumental to developing a quality of place. However, one of the ramifications of strategic placemaking is green gentrification which increases nearby property value due to their proximity to recreational activities and pedestrian-oriented environments. In a study on green urban development and affordability, Dale and Newman (2009) point out that urban sustainable development related to environmental improvement without taking equity goals into consideration leads to gentrification, shifting the neighborhood towards higher-income residents, while forcing out lower-middle and lower income residents (p. 679) The ramification of environmental improvement results in community displacement. The most representative case of the gentrification is the High Line Park in New York City. The High Line Park was once an abandoned rail way, meant to be torn down, located in the Chelsea neighborhood in 1980. In 1999, nonprofit conservancy Friends of the High Line, founded by Joshua David and Robert Hammond, advocated for the preservation and repurpose of the abandoned rail yard, transforming it into a public space from an eyesore (The High Line, 2000). When the High Line Park opened in 2009, the values of properties rose, more restaurants and services came into the neighborhood, and the number of real-estate developments in the surrounding area increased (Barbanel, 2016). However, the High Line displaced the existing residents, as it raised adjacent property values by 35% and attracted a wealthier population to the neighborhood. The High Line Park not only had changed the spatial structure of the nearby neighborhoods, but the dynamic of local commercial and residential activities. Urban tree canopies are another potential factor leading to green gentrification. Donovan, Landry, and Winter (2019) found that trees contribute to higher housing sales price in Tampa, Florida (p. 330). The study shows that “1-percentage point increase in tree-canopy cover was associated with a total increase in sales price of $9,271 to $9,836” (Donovan et al., 2019) when measuring the trees’ impact on house price within 500 feet of the house’s lot. Another study on green gentrification in Barcelona, Spain explored the

relationship between newly created parks in distressed communities and sociodemographic characteristics Anguelovski, Connolly, Masip, and Pearsall (2018) point out that gentrification occurred in parks located in old industrial and waterfront areas (pp. 485-486). Environmental improvements not only have the potential to do harm to the community by driving them out, but also make them question peoples’ positions when facing the environmental improvements. Checker (2011) points out that when it comes to environmental improvements, low-income residents face challenges that she calls the “pernicious paradox must they reject environmental amenities in their neighborhoods in order resist the gentrification that tends to follow such amenities?” (p. 211). The improvements put them in a dilemma; residents are able to enjoy the benefits of such improvements in the short term, but need to suffer the consequences in the long term

Placemaking & Authentication

The second type of placemaking is creative placemaking. In a National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) White paper, creative placemaking is defined as:

In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, non-profit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. Creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structures and streetscapes, improves local business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired (Markusen & Gadwa, 2010, p. 3)

The definition of creative placemaking created by NEA is the most cited definition. The principle of creative placemaking lies between livability, economic development, and arts and cultural activities. This type of placemaking focuses on integrating art and culture into placemaking practice. Community art as art-based creative placemaking is one of the most common practices used for promoting and revealing the culture and history in and of the community. Community art promotes civic engagement through artistic and cultural activities and brings people into the public space, thus contributing to community cohesion. Under this framework, art and cultural organizations, such as museums and art galleries, partner with community artists to work on community-scale project. This type of art project connects community artists to designated communities to develop art projects in the service of promoting and discovering the local history in the community, thus revealing the untold narratives of different ethnicities and peoples in the community. However, controversy regarding community art range from displacing of lower-income residents (Grodach, Foster, & Murdoch III, 2014; Zukin, 1989) to community artists’ identity in the context of community art project. Art historian Miwon Kwon (2004) points out that community artist are basically “outsider[s] who ha[ve] the institutionally sanctioned authority to engage the locals in the production of their (self-) representation” (p. 138). In addition, art historian Grant Kester (1995) indicates that community artist as the delegated person is the “signifier for a referential community, constituency, or party” (p. 6). The sanctioned authority of community artists somewhat shape the relationship between the community artist and the community hierarchically. Kwon (2004) explains that “artist as delegated person “derives his/her identity and legitimacy from the community. This community also comes into existence politically and symbolically through the expressive medium of the delegate” (p.

139). To further elaborate, when the artist comes into the community to develop a community art project, oftentimes, he or she leverages their role as the person who has the power to create a voice for the minority community. This might misrepresent the community’s attitude on social issues. As a result, the community artist as the delegated representative of the community art project needs to carefully examine the ways in which he or she positions themselves throughout and within the project.

The role of art and culture in urban economic development

Art and economic development

The arts and cultural sector contribute to urban economic development b y enhancing the local culture or through providing cultural amenities, making a place attractive to talented workers to live in. Placemaking practices include creative placemaking (Markusen & Gadwa, 2010), placekeeping (Dempsey & Burton, 2012), place guarding (Pritchard, 2018), place branding (Van Ham, 2008), and place marketing (Rainisto, 2003). The role of art and culture in urban economic development constantly changes throughout the different stages of urban development, and has been considered one of the important factors catalyzing urban economic development. Its roles include creating jobs, generating commerce, and driving tourism through arts business incubators and artists’ cooperatives (Phillips, 2004, p. 114)

Arts and cultural industries consists of the collection of occupations that produce and disseminate cultural productions in the city, as known as creative industries. That being said, the role of arts and culture has evolved from the actor that provides aesthetic value and enlivens the social atmosphere to the actor that contributes to economic development. The various roles of arts and culture can be examined through the lens of economy theory supplemented by evidence. As for household location choices, several factors are taken into consideration, include accessible to green space, safety in the neighborhood, quality of life, shorter commute, and low property taxes. Arts and culture in urban areas are another factor that attracts people to move in to the city. The study shows that 90 percent of Americans believe arts and cultural facilities improve quality of life, and 86 percent believe these facilities are important to local economy and businesses (Americans for the Arts, 2018, p. 5). Artistic and urban economist Halkett (2020) points out that culture is treated as an amenity therefore luring professional workers from different industries to live in a culturally-enriched place (p. 46)

Film & media production is one of the important industries in the arts and culture sector, given that it disseminates different cultural values worldwide. The film industry plays a crucial role in both the Los Angeles and New York cultural economies. The cities’ cultural symbolic value crowned by art and culture lend themselves to attracting investment, thus establishing themselves as internationally recognized and contributing to job creation. Job creation is an important factor in urban economic development. For example, people who come to Los Angeles to hunt for a job in the arts and cultural sector, such as film industry, need a place to stay. Both living in rental housing or buying a house contribute to the local housing market. Job creation created by the arts and culture sector is significant, Halkett (2020) points out that “[a]rt and culture combined form the fourth largest employer in New York City” between 1940 and 2000 (p. 49). More recently in California, there were 1.8 million creative economy jobs in 2021. 60% of the creative economy jobs were in the entertainment industry; 314,300 were in fine & performing arts; 62,700 were in the fashion

industry; 42,300 were in creative goods & products, and 284,800 were in architecture & related services (CVL Economics, 2023)

Arts and culture doesn’t only boost economic development through adding symbolic value to the city. For instance, the well-known international cultural exhibition the Venice Biennale in Venice, Italy, attracts massive art galleries, artists and visitors. This event attracts hundreds of thousands of people every year, thus boosting the local economy. That being said, local hotels benefit from the huge demand for accommodation driven by visitors. Drivers from transportation network companies such as Lyft and Uber also benefit from the rising demand of driving people between the event and the hotels where they stay. Local restaurants and vendors also benefit from the event. The economic benefits related to art and culture ripple through local businesses, ground transportation, and overnight lodging. In addition, holding the annual international art fair contributes to the local arts and cultural industry. We can examine the international art fairs through the three mechanisms pointed out by Puga (Puga, 2010, p. 210), in which he explains the existence of urban agglomeration economies from the perspective of sharing, matching and learning. First, emerging artists who attend international art fairs get to interact with other experienced artists and curators. The art fairs serve as the platform for them to exchange ideas about art-making and keep up with the trends of the artworld. Second, art fairs provide an opportunity for artists, curators and connoisseurs of art to network with low search and operational costs. Third, art fairs provide an avenue that allows art agent to share facilities, which saves significant time and transportation cost for people who want to appreciate art without travelling around the globe Which is to say, a multiplier effect in economic development can be achieved by concentrating both physical density and human capital through locating cultural facilities, firms, artists, and cultural together (Dwyer, Beavers, & Hodgson, 2011) In addition, cultural clusters have been gaining prominence over the years (Thomasian, 2015, p. 8; Waits, 2014).

The nonprofit arts and culture industry in the United States has been adding value to national economic growth over the years. In 2001, the nonprofit arts industry was a $36.8 billion business, which supported 1.3 million full-time equivalent jobs. Governments from the local, State to Federal level reaped the tremendous economic benefit of nonprofit art and culture industry: $790 million, $1.2 billion, and $3.4 billion, respectively (Gautier, 2006, p. 2). In 2015, $166.3 billion in economic activity was related to non-profit arts and culture, in which $63.8 billion was related to spending by nonprofit arts and cultural organization, $102.5 billion was related to event spending by their audiences. The nonprofit arts and culture industry supported 4.6 million full-time equivalent jobs, and contributed to $27.5 billion in government revenue (Americans for the Arts, 2015, p. 4). The nonprofit arts and culture industry has grown nearly 73% over the years. The economic activity and job creation by nonprofit arts and culture industry is noticeable. The total economic impact of art and culture industry ripples through other industries. For example, when a city is building a museum, the direct positive economic impact would be the construction cost required for building, hiring museum’s staff, curators, and purchasing hardware and software for operating the museum.

Nonprofit art organization in the City of Los Angeles: Los Angeles Philharmonic Association

The City of Los Angeles is fertile ground for the arts and culture industry, it not only nourishes for-profit cultural organizations due to the fame brought by the Hollywood film industry, but it also provides a place for nonprofit arts organizations to thrive. It would be

insufficient to understand nonprofit arts and culture organizations in the city of Los Angeles without mentioning the Cultural Data Profile (CDP). The CDP is collected by the National Center for Arts Research (NCAR), which includes nationwide nonprofit arts and cultural organizations’ financial and programmatic data. According to the data retrieved from NCAR, nonprofit arts organizations have provided almost 3,000 permanent full and part-time jobs every year between 2017 and 2021.

As for job creations in nonprofit art and culture sector, it should be noted that the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association hired 23% and 31% of total permanent full-time and part-time employees in the nonprofit arts and culture sector in 2020 and 2021 (see Los Angeles Philharmonic Association in appendix). As defined by NCAR, people who work more than 30 hours a week and fewer than 30 hours a week for the entire year are permanent full-time and permanent part-time employees, respectively. In total there was an increase of 841 permanent employees between September 2019 and 2020 and 606 permanent part-time employees were hired by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association. There are explanations for the sharp increase in permanent part-time employees at the Los Angeles Philharmonic during the COVID-19 pandemic (see appendix for explanations)

References

Americans for the Arts. (2015). Arts & Economic Prosperity 5. Retrieved from https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/aep5/PDF_Files/NationalFindi ngs_StatisticalReport.pdf

Americans for the Arts. (2018). Americans speak out about the arts in 2018: An in-depth look at perceptions and attitudes about the arts in America. In: Americans for the Arts Washington, DC.

Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J., Masip, L., & Pearsall, H. (2018). Assessing green gentrification in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods: a longitudinal and spatial analysis of Barcelona. Urban geography, 39(3), 458-491.

Barbanel, J. (2016, 08/07/

2016 Aug 07). The High Line's 'Halo Effect' on Property; Residential values along the park appreciate faster than those farther away. Wall Street Journal (Online). Retrieved from http://libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/high-lineshalo-effect-on-property-residential/docview/1809530445/se-2?accountid=14749 https://libkey.io/libraries/149/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-

2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&genre=article&sid=ProQ:ProQ%3A pq1busgeneral&atitle=The+High+Line%27s+%27Halo+Effect%27+on+Property%3 B+Residential+values+along+the+park+appreciate+faster+than+those+farther+away &title=Wall+Street+Journal+%28Online%29&issn=&date=2016-0807&volume=&issue=&spage=&au=Barbanel%2C+Josh&isbn=&jtitle=Wall+Street+J ournal+%28Online%29&btitle=&rft_id=info:eric/&rft_id=info:doi/ http://libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://usc.illiad.oclc.org/illiad/illiad.dll/OpenURL??ctx_ve r=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-

8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQ%3Apq1busgeneral&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journa l&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Wall+Street+Journal+%28Online%29&rft.atitle=The+H igh+Line%27s+%27Halo+Effect%27+on+Property%3B+Residential+values+along+t he+park+appreciate+faster+than+those+farther+away&rft.au=Barbanel%2C+Josh&rf t.aulast=Barbanel&rft.aufirst=Josh&rft.date=2016-0807&rft.volume=&rft.issue=&rft.spage=&rft.title=Wall+Street+Journal+%28Online% 29&rft.issn=

Bon, L. (2005). Not A Cornfield. Retrieved from https://www.metabolicstudio.org/tags/not-acornfield

Bureau of Engineering, C. o. L. A. (2014). Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration for Taylor Yard River Parcel G2 Project Retrieved from Bureau of Engineering, C. o. L. A. (2018). Taylor Yard G2 River Park Project Community Survey Summary Report. Retrieved from https://eng2.lacity.org/projects/tayloryard/survey_summary_report_taylor_yardG2_81 8.pdf

Bureau of Engineering, C. o. L. A. (2021). Taylor Yard G2 River Park Project Implementation Feasibility Report. Retrieved from Checker, M. (2011). Wiped out by the “greenwave”: Environmental gentrification and the paradoxical politics of urban sustainability. City & Society, 23(2), 210-229. Currid-Halkett, E. (2020). The warhol economy. In The Warhol Economy: Princeton University Press. CVL Economics. (2023). Otis College Report on the Creative Economy. Retrieved from https://www.otis.edu/creative-economy

Dale, A., & Newman, L. L. (2009). Sustainable development for some: green urban development and affordability. Local environment, 14(7), 669-681.

Dempsey, N., & Burton, M. (2012). Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban forestry & urban greening, 11(1), 11-20.

Donovan, G. H., Landry, S., & Winter, C. (2019). Urban trees, house price, and redevelopment pressure in Tampa, Florida. Urban forestry & urban greening, 38, 330336.

Dwyer, M. C., Beavers, K. A., & Hodgson, K. (2011). How the arts and culture sector catalyzes economic vitality. American Planning Association.

Emery, M., & Flora, C. (2006). Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community development, 37(1), 19-35.

Gautier, D. (2006). The Role of the Arts in Economic Development. Australian Chief Executive: Official Journal of the Committee for Economic Development of Australia(Aug 2006), 54-55.

Grodach, C., Foster, N., & Murdoch III, J. (2014). Gentrification and the artistic dividend: The role of the arts in neighborhood change. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(1), 21-35.

Guild, L. A. E. (2022). Taylor Yard Interpretive Project. Retrieved from https://losangelesexplorersguild.com/2022/01/04/taylor- yard-interpretive-project/

Johanson, K., Coate, B., Vincent, C., & Glow, H. (2022). Is there a ‘Venice Effect’? Participation in the Venice Biennale and the implications for artists’ careers. Poetics, 92, 101619.

Kester, G. H. (1995). Afterimage 22 (January 1995) Aesthetic Evangelists: Conversion and Empowerment in Contemporary Community Art1. Afterimage. Kwon, M. (2004). One place after another: Site-specific art and locational identity: MIT press.

Markusen, A., & Gadwa, A. (2010). Creative placemaking. Washington, DC . Metro, L. (2022). Metro Bike Share Data. Retrieved from https://bikeshare.metro.net/about/data/

Niraula, D. (2021a). Census Block Groups 2020. Retrieved from https://geohub.lacity.org/datasets/lacounty::census-block-groups2020/explore?location=33.869009%2C-118.309786%2C8.81

Niraula, D. (2021b). Census Blocks 2020. Retrieved from https://geohub.lacity.org/datasets/lacounty::census-blocks2020/explore?location=33.869009%2C-118.309786%2C8.81

Niraula, D. (2021c). Census Tracts 2020. Retrieved from https://geohub.lacity.org/datasets/lacounty::census-tracts2020/explore?location=33.869009%2C-118.309786%2C8.81

Phillips, R. (2004). Artful business: Using the arts for community economic development. Community Development Journal, 39(2), 112-122.

Pritchard, S. (2018). Place guarding: Activist art against gentrification. In Creative Placemaking (pp. 140-155): Routledge.

Puga, D. (2010). The magnitude and causes of agglomeration economies. Journal of regional science, 50(1), 203-219.

Rainisto, S. K. (2003). Success factors of place marketing: A study of place marketing practices in Northern Europe and the United States: Helsinki University of Technology.

Sean Greene, & Thomas Curwen. (2019). Mapping the Tongva villages of L.A.’s past. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/projects/la-me-tongva-map/ The High Line. (2000). History. Retrieved from https://www.thehighline.org/history/ Thomasian, J. (2015). Using arts and culture to stimulate state economic development. Arts council, UK.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). DP03 Selected economic charateristics, 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table?q=dp03&g=0500000US06037$1400000&tid=ACSDP5 Y2021.DP03

Van Ham, P. (2008). Place branding: The state of the art. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 126-149.

Velthuis, O. (2011). The venice effect. The Art Newspaper, 20(225), 21-24.

Waits, M. J. (2014). Five roles for arts, culture, and design in economic development. Community Development Innovation Review(02), 017-023. Western States Arts Federation. Public Art Archive. Retrieved from https://publicartarchive.org/

Whitehead, F. (2008). SLOW Clean-up. Retrieved from https://franceswhitehead.com/whatwe-do/slow-clean-up-civicexperiments#:~:text=SLOW%20Clean%2Dup%20is%20a,prevalent%20throughout% 20the%20urban%20landscape.

Wyckoff, M. A. (2014). Definition of placemaking: Four different types. Planning & Zoning News, 32(3), 1.

Zahniser, D. (2021). Census reports declining population on L.A.’s Eastside, fueling undercount fears. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-0830/los-angeles-redistricting-population-drop-census-undercount-fears

Zukin, S. (1989). Loft living: Culture and capital in urban change: Rutgers University Press.

Metro Bike share analysis

There are no Metro Bike stations within 1.3 mile of the Project site. The following analysis examines the potential economic benefits that can be brought by Metro bike users to G2 park.

Cultural asset mapping

The list of cultural assets in the surrounding community of G2 project.

There are four artists based in the surrounding communities of G2 park, include Angie Jones, Karen Kimmel, Matt Gagnon, and Sam Clayberger.

Angie Jones:

“Stix and Jones, also known as Angie Jones, is an artist who is known for creating visually striking pieces featuring bold colors and shapes that evoke emotion and movement incorporating a mix of traditional and digital mediums. She has exhibited her work in galleries around the world and her pieces are highly sought after by collectors”

Karen Kimmel:

Karen Kimmel creates “a multimedia installation for the window of her Melrose atelier, incorporating quilted canvas, hooked rugs and sculptural textiles. She also created a series of merchandising trays inspired by her drawings, as well as a suite of drawings to compliment the designer’s colorful ‘All for Love’ jewelry collection.”

Los Angeles Philharmonic Association

One explanation is that Los Angeles Philharmonic received a Paycheck Protection Loan of $10M approved by City National Bank, which enabled them to hire more part-time employees. However, if one looks at the Los Angeles Philharmonics total personnel expense (W-2 employee salaries and benefits, independent contractors, and professional fees) between 2019 and 2020, the expenses experienced a sharp decline. The most reasonable explanation is that LA Phil didn’t report back the number of part-time workers they hired before. That said, the LA Phil’s contribution to urban economic development through job creation should not be underestimated.

G2 River Park Biennale

Informed by the various art fairs such as Frieze Los Angeles, LA Art Show, and Felix Art Fair take place in Los Angeles. I propose the “G2 River Park Biennale” art fair attempts to draw people’s attention to local artists and art businesses based in the community. This event will take place in two avenues in G2 park, including the ground floor of placemaking research institute and the ground floor of the museum near G2 park’s ingress/egress route from San Fernando Rd. Art fairs have a positive impact on artists, opening up opportunities to work with museums and galleries and increasing artists’ visibility to art collectors. A study about “Venice Effect” shows that “more established artists appear in a greater proportion of international and solo exhibitions after their appearance at the Biennale” (Johanson, Coate, Vincent, & Glow, 2022). In addition to the biennale’s positive impact on artists, its impact on the art market is also notable as well (Velthuis, 2011)