Before

spring there are days like these.

How I met them: at Wawa (agh), on Tinder, on Tinder again, six months later (aghhghh), through mutual friends, in class, in the 4th floor of DRL, the math lounge, of all

How I loved them: well, badly. Through all the amateur poetry. Why was it so hard to write about them? And why did every attempt turn out so badly? All I wanted was to remember everything.

Like being with W last spring. The sweat collecting on his forehead like diamonds. Better than diamonds. I didn't know then that beauty never needs a metaphor. But anything worth writing about is also worth writing badly about. And failing in love does not mean failing at love.

After sex: "What are you thinking about?"

"Nothing."

Nights in X's bed with the white curtains around his windows. Strength and patience rising off him as he sleeps. His chest. His shoulders. The fine dark hair of his stomach. God he's so lovely that just looking at him makes my chest hurt slightly. I never want to forget this.

In six months he'll be in California, joining the ranks of professionals who are certain they will soon own luxury cars and at the same time manage to be good.

Now I know that every person has many people inside them, little people each with their little ambitions, their exhaustion, their favorite way to eat an egg.

Now you stare at the strangers walking in front of you on Locust, and feel the space between their fingers, which is love, a small space.

And the guy from the math lounge wasn't my type, I don't like loud talkers, but he was so committed to his notions of symmetry and continuity, when I heard him talk about stochastic homogenization I wanted to press my mouth to his, my life to his life. Am I poly? Am I bi? Wrong questions. Here's a slightly less wrong question: How to kiss a poisson process?

After sex: "What's your favorite number?"

"I like powers of two. They make sense to me."

"What sense?"

"Like, 16, eight. They open up. Like trees. They're not rare, but they have their own natural beauty."

I met the first boy I ever had sex with at camp in May where I was the best writer in the workshop. If I had been just a little bit better, I would have realized that there were people my age, many people, producing work of a caliber beyond my compre hension. On one of the last days of camp he asked me if I wanted to be his girlfriend. I said no. I thought, people don't just date other people because they're there and you are too.

And last week X said, "Let's just be friends." And smiled. Then there's the moment where he looks at me, and I'm supposed to say something. But I just want to breathe in what he breathes out. How to kiss a person's breath without kissing the person? Does everyone else think this much about sex? Does everybody else think this much about nothing?

Now here's the real question, and if only STEM people would explain this instead of inventing new types of cars. Tell me where are all the people I've loved. And left. And who have left me. And how does love blow through life. And how does life still blow through time. And how does time blow through hair. Because I will always love you. Even when I don't. Even if I cross the street to avoid you. Whoever I'm with. Wherever we are.

Now W and I are stalled at an elevator with nothing to say to each other. And if he'd asks what I'm thinking, I won't say, "Nothing." I'll say, "How incredible that we used to be in love." And remember that time when we were unhappy in that tiny room and it was all horrible? What if it wasn't? What if I'm thankful that it happened? That I did it with you?

Today I'm 21. Soon I'll be 22. Soon May will be here again. Soon my nights with X will be gone. We know where this goes. Okay, days, come in. I’ve been practicing for this my whole life. I ate a peach this morning, I remember the sound it made at the first bite, like clicking teeth while kissing. "I won’t be your something," the peach said. "Okay," I said, and kissed it.

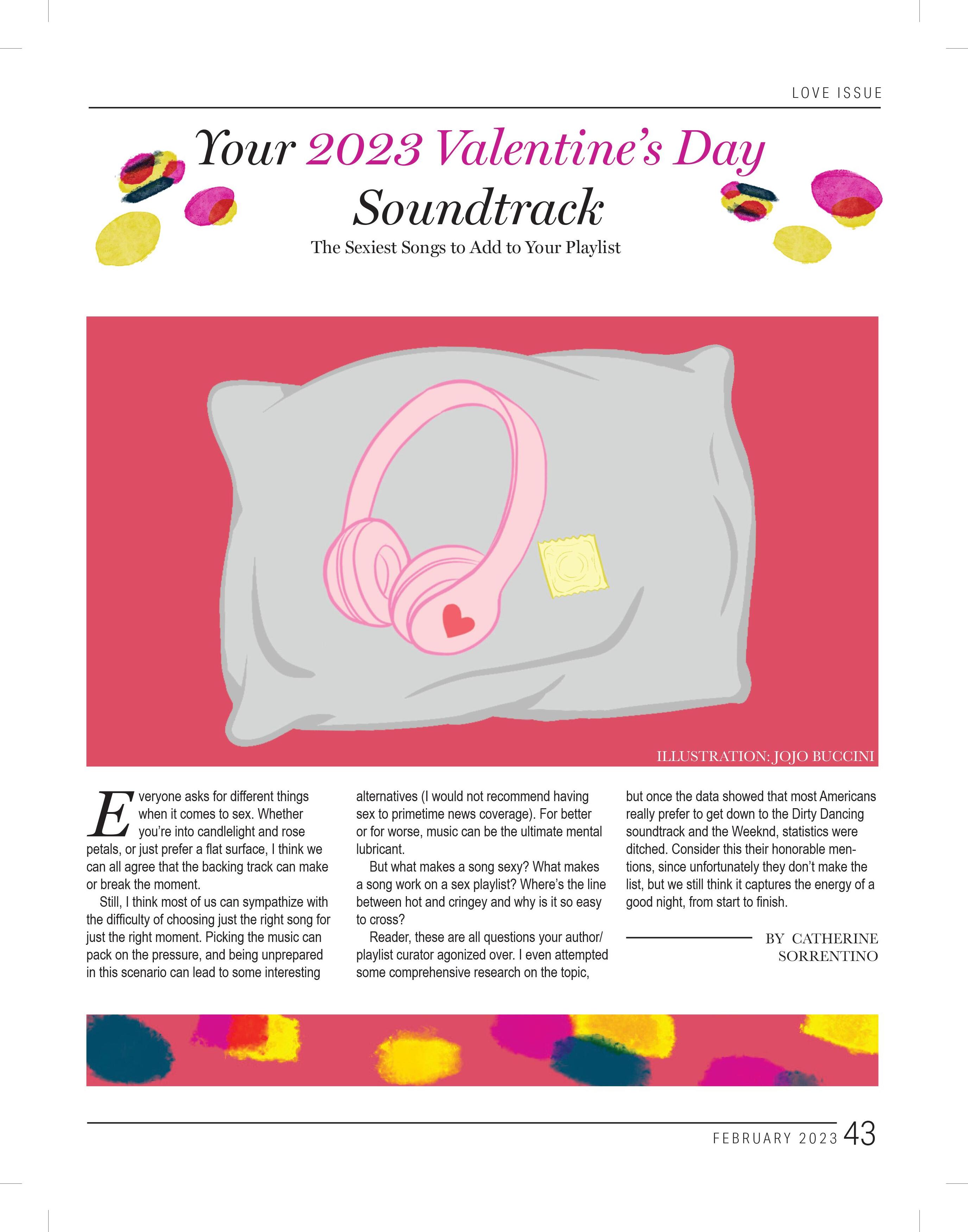

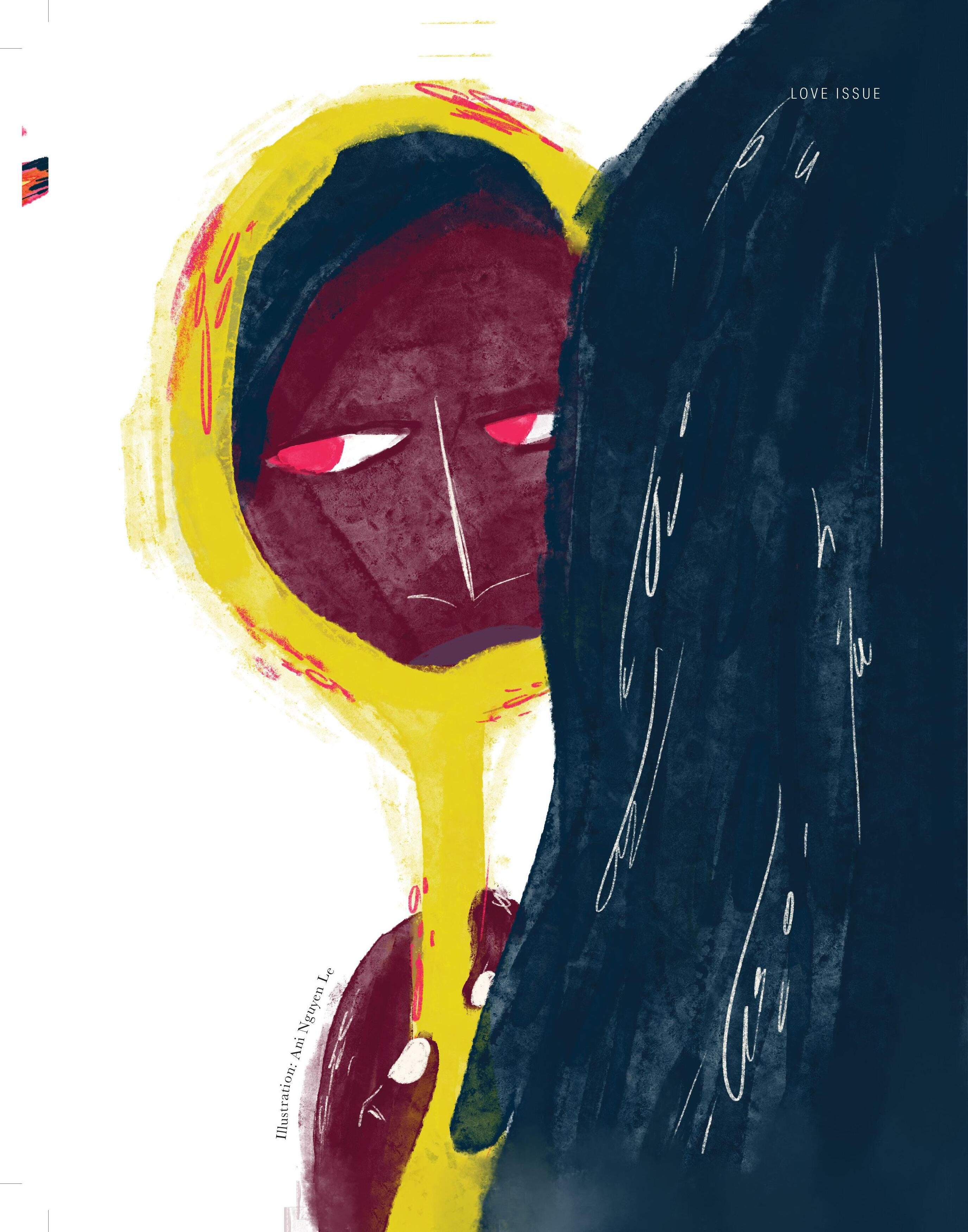

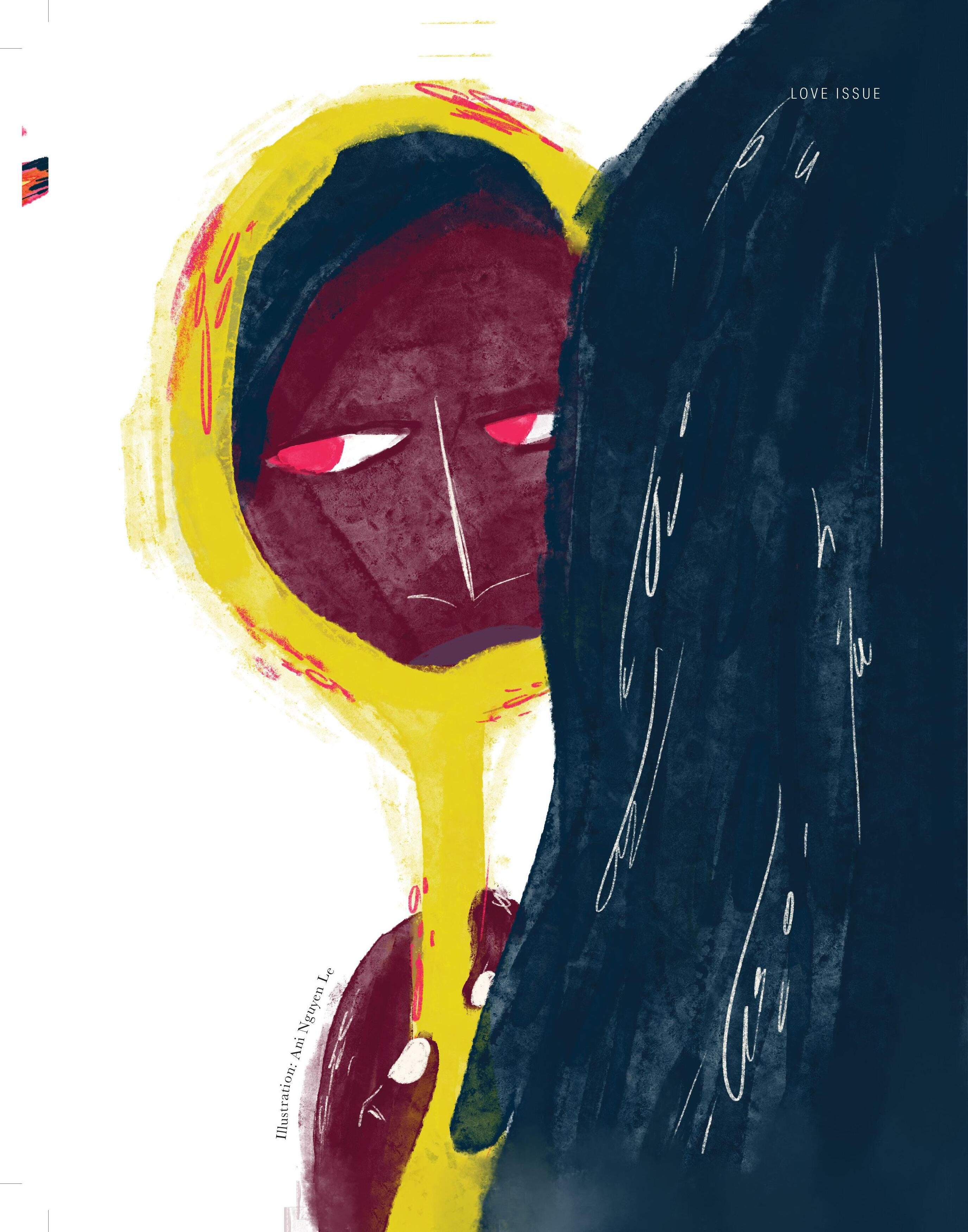

Illustrations: Collin Wang

Then you realize that yeah sex is good, but perhaps intimacy is even better.

Okay yeah sex is good but have you ever had the creamy crab and shrimp risotto from Quaker Kitchen after your first day of classes and followed it with the creamy tiramisu for dessert and your body literally shook—well, in the case of this strategically named dining hall, quaked—with pleasure?

William Penn establishing Pennsylvania as the Quaker province in the 1680s directly caused that line to be written—nay, happened only for that line to be written, I’m convinced. Best domino effect in history.

And yeah sex is cool but have you ever argued your case to your organic chemistry teaching assistant the day after the scores for the final were released, because he was, quite literally, edging you to an A, and then winning the argument (by a sweet, sweet technicality) to receive the singular point needed to take you over the edge?

In hindsight, perhaps I wouldn’t have needed such a saving grace if I had spent more time studying organic chemistry instead of the anatomy of my boyfriend. But unfortunately I was too distracted having my guts rearranged to care more about rearranging carbocations. A sweet victory was achieved in the end, though. One arguably sweeter than the other.

Because yeah sure sex is great but have you ever had a scaldingly hot shower after days of cold showers (because the dormitory you pay a disturbingly large amount of money for, in the Ivy League institution that gets a disturbingly large endowment every year, had decided to stop running hot water for a few days in the middle of the winter cold) and felt all of your worries and cares melt away with your skin?

Yeah sex is nice but have you ever had your dad jokingly hold up three fingers, your mom question why he’s holding up the symbol for the Mockingjay from The Hunger Games, only for your dad to tell your mom to read between the lines? And she innocently asks if it means “I love you” but what he really meant was to literally look between the lines to see that he’s holding up his middle finger to jokingly flip someone off. But you can tell he really loves her because he chuckles adoringly and nods. And he tells her what it actually means but that he prefers her interpretation. And she laughs, and he laughs, and you laugh with them both.

And you think to yourself how easy love must be. How wonderfully easy, to just laugh.

And yeah sex is good but have you ever binge watched all of the Spider–man movies, from Tobey Maguire to Andrew Garfield to Tom Holland, in the span of winter break because he’s your boyfriend’s childhood hero and it’s the closest thing you’ll get to watching your boyfriend growing up? And your eyes are getting tired, but his eyes are lighting up, and all of it’s worth it just to see that little–kid smile on his face.

Then you realize just precisely what you’d given him: the power to break your heart, and the responsibility to take care of it. Because you’ve fallen hard (though hopefully not as hard as Gwen Stacy), but he’s there to catch your fall.

And of course sex is good but have you ever opened your door to your best friend holding up a cup of thai tea, with less ice and 75% sugar, because she remembered that’s how you like it, without ever asking for it? And you thank William Penn, or Ben Franklin, or whoever built that TeaDo on Chestnut Street, for what’s actually the best domino effect in history.

But if we’re talking about domino effects, I should raise the contender of tracing my history on the palms of my grandmother. How her existence has led to mine, how her embrace means more than just a hug from a person, because it’s past and present colliding, it’s future being made.

Then you realize that yeah sex is good, but perhaps intimacy is even better.

To know yourself—love yourself—so well that you take care of your body with a creamy crab and shrimp risotto, that you rejoice in your own accomplishments, no matter how small—because size doesn’t matter here.

To find love in the smallest moments, in silly jokes and Marvel movies, in knowing your best friend’s boba order by heart, in cooking food with your grandmother, in living so fully, so brightly, so vividly your heart might burst.

So yeah sex is good but have you ever written about things that are better than sex and poured so much of yourself into it, put too many self–incriminating anecdotes to be truly anonymous, and felt more bare and more naked than you do during the physical act?

Ah, well, never mind. Nothing beats an orgasm.

She’s holding the trash can open and I’m thinking: this is it. This is it.

Something changed. I heard her name on the TV in November and I sat on the toilet and cried so hard I couldn’t breathe. I saw her in town walking with her mom and I had to turn around and go straight home. You were heartbreak the way a flower

I didn’t care if she would hate or fear me. It didn’t matter. I used to think I would’ve kept it (my sexuality, her homophobia) a secret forever if it had meant a different

I don’t entertain daydreams about changing her mind any longer, but here’s an old one. Some future version of me says to her: "Will you be my maid of honor?" By the way, I'm marrying a woman. That’s irrelevant. Everyone at this dream wedding is irrelevant. They’re all blurry faces except for me and her. Some future version of her

Sometimes I entertained a different kind of notion. There’s a possibility that she knew about me. Maybe she wanted the same thing—maybe she didn’t care, either.

I wonder sometimes, even now, when I’m sick to my stomach, if I’ve been in love without knowing it. But let’s look at the facts one last time, with the cold certainty of a heart sliced cleanly in half. We were best friends, past tense. The pen’s been set down, and even if I ever did love her in that way, it’s been lost to the years between us. If I did have a chance to pick the pen up again—if I bumped into her in my too–small town, me in my older and newer self, Mary in her white robe and blue veil—I wouldn’t.

The Mary in my head, the one that held the flap of the trash can open, the one that sat on the sand in the morning sun with me, the one that will speak at my wedding in some grand, alternate universe—I get to keep her, but that’s because I don’t get to keep all of her. If we had maintained the façade that our friendship inevitably would’ve decayed into, it wouldn’t have been honest. You can’t be friends with pieces of a person. She couldn’t have loved the part of me divorced from my sexuality, and I couldn’t have

It was never a matter of forgiveness because I don’t feel that she wronged me. But for whatever my—let’s call it what it is—higher moral standing, is worth, I would’ve forgiven her in a heartbeat. Mary, to you I say: I hope you remember me as I was. If I see you again I will tell you about myself. I owe that to both of us. I had fun writing together, and the story was worth it, every comma and apostrophe and period. This is

stigmatized for its focus on romance and erotica. Yet these criticized tenets can also provide unique representation for female and queer sexuality. Fanfiction is mostly written by women and often centers queer characters, so women’s sexuality and queer identities are articulated louder in fanfiction spaces than in mainstream media.

Why can’t we do that with Star Trek?

Fanfction has often been stigmatized for its focus on erotica and romance. It's time to rewrite that narrative.

BY VIKKI XU

f you’ve ever found yourself involved in a fan community, you’ve probably stumbled upon fanfiction. Maybe you were unhappy with the last season of Game of , so you searched for an alternate ending. Perhaps you’ve scoured the internet for a blossoming romance between Harry Potter and Draco Malfoy and devoutly followed their (non–canon) journey from enemies to lovers. While many may grow out of their Harry Potter or Game of Thrones obsessions, fanfiction remains a fundamental part of fan communities, or “fandoms,” of all kinds. As any new media becomes popular, it is almost certain that fans will produce fanfiction—works of amateur fiction that borrow the characters, settings, and concepts of existing media—to go along with it.

In the last 15 years, fanfiction has gone from fringe and eccentric to almost mainstream. Still, the genre has often been

Francesca Coppa, a former Wolf professor of television studies at Penn and current chair of the English Department at Muhlenberg College, recognizes this role: “I teach film studies, and we talk about the male gaze … and the way in which mainstream culture, even when it’s not trying to, has a very, kind of, objectifying and male–centric notion of gender and sexuality. And [fanfiction], because it comes from a kind of female–dominated community, doesn’t. It’s different. And it freaks people out.” While fanfiction provides a place for these communities to share their work, that may also be a reason why it is an unsettling topic for many people. In this genre, themes of consent, kink, sex, and relationships are explored in a space away from the male gaze of mainstream media.

In addition to its suggestive reputation, at that time, fanfiction lacked credibility as a form of literature. Fanfiction writers could easily come under attack for stealing material, both in an artistic sense and in a legal framework. Yet, Coppa recognizes that fanfiction is original, transformative work: “The phrase ‘transformative works,’ it makes my heart happy every time I see it [...] It’s like, of course you didn’t steal. You just wrote 100,000 words, right? You did all the work and you wrote a whole novel.”

Either way, the collaborative and amateur nature of fanfiction is a refreshing break from the modern ideas of publishing companies and copyright infringements. As an English professor, Coppa teaches fanfiction alongside other retellings of stories, like "Beowulf" or Sherlock Holmes . In this way, fanfiction resembles older forms of storytelling and creativity, where stories are retold and remixed over time. People have reproduced Hamlet and retold Romeo and Juliet countless times—even Shakespeare himself didn’t write those plots from scratch.

The rise of the internet can be connected to the larger growth of the fanfiction community. As the world wide web became commercialized in the early 2000s, the fanfic community needed a platform—specifically one where readers and writers could be protected from copyright–related legal action and censorship. In 2007, Coppa joined a group of volunteers to start a nonprofit called the Organization for Transformative Works, which works on projects for a community–focused space of amateur writers, far from the dangers of commercialization.

OTW’s main project is Archive of Our Own, a public online archive for fanfiction and other fanworks. The website is very purposefully described as an archive—it’s not social media or an online community, but instead a space for storytelling. As a way of encouraging creativity amidst the stigmatization of fanfiction, OTW allows for anonymous contribution. Unlike social media or online communities, there are no incessant email reminders to finish a story or recommendations for new posts. There’s no product marketing or advertisement. Additionally, the stories don’t have a short lifetime like posts on social media do. “We're seeing a lot of this as people come over from Instagram or Twitter where they think, like, will people think I'm creepy to comment on a Star Trek story that was written in 1992?", Coppa says, "And the answer is no, no more creepy than it would be if you went to a library and took out a novel written in 1860.” Since its creation in 2008, AO3 has become the 56th most–visited website in the United States—and the most–visited arts and entertainment site, above Disney Plus, Hulu, and HBO Max. Amidst the commercialization of mainstream media, AO3 is a unique reminder of the importance of community storytelling, accessible libraries, and sharing ideas. Fanfiction is a unique opportunity for readers to claim agency over the stories they hear and share their ideas with a larger community. So take this as permission to finally finish that BTS fanfiction you were reading, without any shame or stigma. ❋

Kristen Ghodsee, chair of the Department of Russian and East European Studies, is revolutionizing our understanding of sex and love. BY NORAH RAMI

hat do ECON 0100 and your sex life have in common? It’s not just the status of ‘complicated.’

“So many people think that capitalism stops at the bedroom door; you close the door and capitalism stays out. Nobody wants to realize that capitalism is actually in bed with us all the time,” says Kristen Ghodsee, a professor of Russian and East European studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ghodsee frst began to consider the relationship between economics and love in graduate school at the University of California at Berkeley after reading the works of leftist thinker Alexandria Kollontai. “It had never occurred to me that the way that I felt about my friends, later my husband, my child, or my

parents were in any way related to the economic system within which I lived,” she says.

Ghodsee began to research the ways relationships change based on economic and political systems, namely within capitalist and communist states. Ghodsee looked into surveys conducted during the fall of the Berlin Wall, comparing the communist East to the capitalist West in what is colloquially known as “The Great Orgasm War.” She found that women living under the communist regime in East Germany tended to report greater sexual satisfaction.

“I broadened out and thought, ‘Let’s talk about love and friendship as well. It’s not just about sexuality,’” Ghodsee

says. As she expanded her research to other countries and relationships, Ghodsee found similar trends. Under capitalist economies, individuals tend to commodify their relationships into a mechanism of exchange; people might choose their partners—both romantic and otherwise—for economic and social opportunities rather than for the enjoyment of their company. “It turns out that social scientifc evidence shows that when we transactionalize different forms of relationships in our life, whether they are flial, friendly, or sexual, they tend to become less satisfying over time,” Ghodsee says. Alongside teaching a class entitled “Sex and Socialism,” Ghodsee’s work received national attention in 2017 after publishing a viral New York Times op–ed, “Why Women Had Better Sex Under Socialism.” After receiving a call from a publishing company, Ghodsee expanded the op–ed into a full–length book, which received national acclaim and has since been translated into 14 languages.

Ghodsee’s next book, “Everyday Utopia,” coming out this year, explores radical expressions of love throughout history, from Pythagoras’ communes to cenobitic monasticism. “From the beginning of recorded human history, there have always been groups of people who resist the dominant notion of love, sexuality, and family life,” Ghodsee says. “I think that there’s so much that we in the 21st century can learn from those communities because it’s happening, discussions about polyamory and alloparenting and cooperative care.” Understanding alternative forms of relationships beyond the traditional Western nuclear family is about more than sex; it offers insight into larger societal issues, such as the modern “loneliness epidemic.” “It’s this idea that we can choose our kin and we can live together in healthy and robust networks of love and care with people who aren’t our blood relations. And that is something that human beings have been doing forever,” Ghodsee says.

Much of Ghodsee’s research on utopias can be applied to college lifestyles in terms of communal living and unconventional relationships, like “chosen family.” In fact, modern dormitory life is directly modeled on the utopian experiments of Epicurius and Plato. “Minus the student loans, hierarchical politics, status signaling, and all the ugly things that happen at Penn that are ultimately fueled by capitalism,” Ghodsee quickly adds. Even modern hook–up culture can be seen through a utopian lens: “Women are emancipated enough to be able to do whatever they want with their bodies, and it’s a community that’s conducive to that, which would have made Plato incredibly proud.” Unburdened by expectations of marriage or children, college students have the freedom to connect with a wide network beyond the pre–defned social boundaries of the nuclear home, reimagining defnitions of love and care.

But still, despite the utopian opportunities available at Penn, transactional relationships pervade other facets of student life— pre–professionalism often places an emphasis on networking, encouraging students to build relationships as a means of accessing further opportunities. While networking and coffee chats are often necessary aspects of career–building, turning personal relationships into professional endeavors can leave students feeling unsupported in the long run. “I really think that the transactionality of relationships at Penn is underpinning a lot of the stress and anxiety that Penn students feel,” notes Ghodsee. But there’s a simpler solution than an economic revolution. “Just share more time with people in a nontransactional way. Hang out in your dorm with whatever your choice of beverage and just do nothing—just talk, just share,” she suggests.

So whether you’re having bad sex or just feeling stressed, maybe it’s time to send that text: “Hey, want to do nothing with me?” ❋

Graphic: Collin Wang

tudents enter college expecting “the best four years of their lives.” Many are on their own for the frst time: decorating their dorm rooms with posters, registering for classes they’re passionate about, and choosing which frat to party at on Friday night.

But this newfound independence can come with its own challenges. A college like Penn costs upward of $80,000. At times when work–study cannot pay the bills, some students embrace alternative strategies.

Sex work is not traditionally associated with higher education, but for between 2.1% and 7% of college students, it’s the form of work they turn to. While each sex worker has a unique experience, most students engage in sex work to achieve fnancial stability, according to a 2021 Iowa State study. Amid days of

The sex work community, its advocates, and its challenges, according to a Penn graduate student.

BY KATE RATNER & KATIE BARLETT

attending classes, studying for exams, and sometimes working an additional day job, students involved in the sex industry fnd themselves with an extra list of responsibilities.

Macy, a graduate student at Penn, has been a sex worker for the better part of the last decade. When asked how they chose their work name, Macy—who uses both she/her and they/ them pronouns—responded with a chuckle.

“I met a hot girl named Macy at a queer dance party,” Macy says. “I liked the name, so I stole it.”

Macy began working in the sex industry during their junior year of college. It all started on Tumblr.

“I was following someone who talked about camming, and I was really broke,” Macy says.

With no fnancial support from family and an underpaid work–study position, Macy began performing online sex work to pay her tuition and rent. She was drawn to the sex industry because it allowed her to make money “on [her] own terms.”

Sex workers engage in several forms of work that can be online or offine. Camming involves charging clients on websites and social media platforms for live or recorded sexual performance. When sugaring, sex workers spend time and offer sexual services to older, wealthy men in exchange for gifts and money.

Over the years, Macy has delved into many different areas of the sex industry, nearly all online.

They entered the industry with camming. A few years later, they briefy tried sugaring, but found that they didn’t enjoy it. After talking with another Tumblr user who’d moved from sugaring to pro–domming, they also made the switch.

Pro–dommes take part in domination, which can sometimes include topping, BDSM, or kink. “The main characteristic from my experience is just performing control over my client,” says Macy. “I say ‘performing’ because the reality is that clients have more power in those situations because we are doing criminalized work.”

Some of the risks involved: Clients may not pay, and are in a position to call the police on the workers or physically harm them without repercussion. If employers or colleagues discover her second job, Macy could be fred.

When interacting with clients, Macy has a number of strategies to help protect themself, including screening clients and ensuring work and personal social media photos don’t overlap. Like most sex workers, she has limits on what she can do, and is comfortable doing, with clients. As a prerequisite for an interview, Macy sent a series of ethical guidelines designed to protect their identity and the image of sex workers.

Throughout her sex work career, Macy has always had a day job. She emphasizes that sex work is among the most “humanizing” forms of work, as she’s able to set her hours and pay rates to align with her perception of the work’s value. The income allowed her to start seeing doctors and therapists at a time when she did not have health insurance.

“I’ve began to see [sex work] as a form of resistance to a lot of the really exploitative labor conditions that we live in,” Macy says.

Throughout our conversation, Macy repeatedly acknowledges the privilege they hold as a white sex worker. Black, brown, Indigenous, and trangender sex workers are disproportionately impacted by violence and policing, and are not always in the position to set their own wages or work as they choose.

“My safety, access, and income as a sex

worker is deeply informed by white supremacy and the way I beneft from that as a white person,” Macy says.

At the beginning of their sex work career, the stigma around their line of work affected Macy’s ability to share their experiences with most of the important people in their life. Their

Illustration: Wei–An Jin

boyfriend at the time was the only person who knew.

“There wasn’t OnlyFans; there were really janky old camming sites,” Macy says. “I didn’t feel comfortable or safe sharing what I did for money. Peoples’ attitudes about sex work were really harmful, and that was something

you could count on from everybody you talked to because of the lack of understanding and awareness.”

By 2020, Macy felt more comfortable sharing her story with friends and even a few select family members. She credits celebrities who have become more open about their sex work experiences and the sex workers’ rights movement, largely led by trans sex workers of color, for the shift in narrative that’s happened over the past couple of years.

“I was proud to identify as a sex worker and still am proud,” Macy says. “But not everybody has earned my story. I will always recognize that a lot of our experiences are very sacred and are meant to be held within our community.”

Macy remains selective with who they choose to share their story with. “Anytime I hear people—even jokingly—refer to one another or themselves as whores who are not sex workers, I [know] that’s not a safe person for me to talk about my experience,” Macy says.

The myths that surround sex work contribute to the stigma that sex workers face. Common narratives tend to portray sex workers either as victims with no other choice or empowered women who love the work. Macy contests this simplistic binary, emphasizing that the reality is more “complicated and nuanced.”

“In my mind, all forms of labor are coerced to some degree,” Macy says. “I don’t want to go to my day job, but I also don’t want to starve and die. For many people, sex work is the best available option to meet those basic needs. We should let people speak for themselves about their reasons for entering the industry and believe them.”

With the exception of Nevada, where prostitution is legal in regulated brothels, sex work is illegal in nearly all parts of the United States. Many sex workers are caught in “cycles of surveillance and criminalization,” according to Sex Workers and Allies Network, including charges related to trespassing and loitering aimed at street–based sex workers. These laws have detrimental impacts on the everyday lives of sex workers. Arrest and conviction records make it challenging for sex workers to fnd other kinds of work, access housing and other public benefts, vote, and qualify for fnancial aid, among other challenges. Further, sex workers disproportionately

lack access to health care and are less likely to report violence due to the criminalized nature of their work, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

COVID–19 only exacerbated the inequities that sex workers face. According to the research program “Sex Work & COVID–19,” sex workers were forced to choose between their health and basic needs as sex work venues closed, client interest declined, the virus spread, and they were excluded from COVID–19 relief.

“I was extremely lucky because my work is primarily online,” Macy says. “I continued, although a lot of my clients were fnancially strained themselves. But many people work exclusively in person and don’t have the luxury of online work. They had to make the diffcult transition to online or continue in person while doing their best to stay safe. The pandemic really hit many of us hard.”

While Macy views decriminalization as an important step towards providing sex workers with access to safety and support resources, they believe legislation is only a small part of the solution.

“The liberation of all sex workers would take a complete upheaval of how our world works,” Macy says. “We would have to revise how we relate to each other and uproot all forms of systemic oppression to make conditions safer for sex workers.”

The California legislature has taken steps to improve working conditions and better the everyday lives of the state’s sex workers. In July 2022, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the Safer Streets for All Act, which will help to prevent discriminatory arrests and harassment based on dress and career choice.

The act, which took effect on Jan. 1, repealed California Penal Code Section 653.22, which criminalized loitering for the intent to engage in sex work and permitted unjust profling of trans women and cisgender women of color, according to the ACLU.

“Anti–loitering laws are usually used to disproportionately arrest and imprison Black and brown folks, sex workers, trans people, and people at the intersections of all those experiences,” Macy says. “It’s an amazing step forward, but decriminalizing is the goal. When it’s criminalized, it is just really, really hard to offer people services who are being harmed in the industry.”

Many other college students like Macy are impacted by the stigma and bias that surrounds sex work, and sex work on college campuses remains neglected and underresearched. The Iowa State study highlights the stories of seven college students involved in sex work, urging campus offcials, administration, and health care services to provide support and visibility for sex workers on campus.

In a message to the campus community, one participant writes, “There are sex workers on your campus. We are here. In your classroom, downtown at the bars, in restaurants. We’re your roommate, your coworker, your friend. It’s not that we don’t want to tell you, we just don’t know if we can or how we could. We have to stay safe and stay hidden.”

But just because they’re hidden, doesn’t mean they’re not there. “Sex workers are everywhere, and the reality is that most people probably know at least one,” Macy says.

But Macy isn’t aware of any services at Penn that specifcally support student sex workers. They also believe in the importance of minimizing the fnancial burden associated with attending university as means of supporting student sex workers.

“When I was putting myself through college, I had very few options to pay the bills,” Macy says. “If I wasn’t under the pressure of absurdly infated tuition rates, I might have been able to sustain myself working ten hours a week in my work–study job. Anything that Penn can do to relieve the economic pressure will create a safer and more supportive environment for people, regardless of the work they’re doing.”

Ten years after their entrance into the sex work industry, Macy has started to wind down, working with only two of her long–term clients. The work is no longer the source of her rent, but instead contributes to forms of joy, including treating her friends, paying reparations, and donating to mutual aid efforts.

“When you’re in a feld for ten years, you get pretty good at it,” Macy says. “I’ve been able to develop myself as a worker and build really strong relationships with some clients. My relationship to sex work has gone from a place of scarcity to one of abundance, and that’s really beautiful for me.” ❋

To support student sex workers, check out this resource: supportforstudentsexworkers. org.

This month: octuplets, feminist theory, and gerbiling (DON'T look it up).

"Ive got eight babies to squeeze out."

"Ive got eight babies to squeeze out."

treet s ew cto mom

treet s ew cto mom

"I never got past my oral–aural fxation stage.

"I never got past my oral–aural fxation stage.

— With AirPods in His Mouth

— With AirPods in His Mouth

"They gave me free drugs because my tits were out."

“I love the guy using the virginity as a social construct argument to get in a girl’s pants.”

“I love the guy using the virginity as a social construct argument to get in a girl’s pants.”

— The Guy in Question

— The Guy in Question me drugs because my tits were out."

— Castle Darty Refugee

— Castle Darty Refugee

“I looked up hamster tube and it gave me porn … that’s not what I wanted.”

“I looked up hamster tube and it gave me porn … that’s not what I wanted.”

efnitely ot ichard ere

efnitely ot ichard ere

Newspaper critics at the time were quick to scrutinize the avant–garde painting as one that broke from tradition—and not in a good way. In contrast to conventional works which prioritized naturalism, impeccable technique, and classical subject matters, Olympia boldly and overtly rejected tradition with its aggressive, imperfect brushstrokes and harsh lighting and coloration. But, while Olympia certainly breaks with artistic predecessors, it still references tradition—just not in a manner the Academy appreciated. Clearly inspired by Titian’s Venus of Urbino of 1538, a pious, sensuous representation of Venus, Manet created his own warped version of the fgure, stripping what once was a goddess of her moral purity through subtle sexual details.

BY JESSA GLASSMAN

André Dombrowski, Frances Shapiro–Weitzenhoffer Associate Professor of 19th Century European Art, describes Manet as "the artist who is perfectly aware of tradition, and actually cites it very deliberately, but at the same time updates it in a way that it doesn't exactly become unrecognizable. But there's also a high degree of disruption.”

Despite having been painted more than 150 years ago, Édouard Manet’s Olympia continues to resonate throughout the art world. In 1865, the painting debuted in Paris’ prestigious Salon, controlled by the French Academy of Fine Arts, immediately scandalizing the scene. The work subversively approached the reclining female nude with its daring technical, stylistic, and thematic choices. While she was created by a man, Olympia has consequently joined the ranks of groundbreaking and infuential women, both in the art world and beyond.

Specifcally, situating the title of the work within its historical context reveals that the sitter is a courtesan. The fgure’s stark, pale skin tone (especially compared to the warmth of Titian’s Venus ) shocked critics, who likened her to a corpse. Manet does away with Titian’s soft, blended technique, using textured brushstrokes which give the work a sense of harshness. Olympia defes traditional notions of femininity, with stubble under her armpits as well as dirty hands and feet. While Venus lays clean, pure, and comfortable on her impeccable couch, Olympia does the opposite. She is stiff, sitting upright on wrinkled sheets.

She covers her crotch with ownership and power, seen in the deep shadowing of her hand that indicates it is fexed. Venus, by contrast, lays her hand gently and in a position many have characterized as inviting, complementing her sultry gaze. Most starkly, Olympia is confrontational—a demeanor, particularly for a sex worker, that was unacceptable and baffing to the French art world at the time. Even the black cat at the edge of the bed offers a contrast to Titian’s Venus, who lays with an adorable puppy by her feet; it symbolizes deviant sexuality as opposed to fdelity.

While the reclining female nude is an artistic motif portrayed time and time again even before Manet was born, through technical and thematic subversions, the artist effectively stirred controversy that, depending on your perspective, either marred or revitalized the trajectory of art. Professor Dombrowski explains this phenomenon: “From the moment Olympia is shown in the Salon of 1865, it becomes kind of the touchstone for avant–garde representations of female nudity.” Some artists who interpreted and responded to the work in later art history include Paul Cézanne, in his A Modern Olympia (1874), Paul Gauguin in Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892), and Henri Matisse in his Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) (1907).

But while Manet and those inspired by Olympia certainly dismantled artistic expectations with an avant–garde approach, many gendered norms at the time remain intact in their works. Professor Dombrowski gives some much–needed historical context: “Remember that when Olympia is painted, women cannot vote. There is almost a complete disenfranchisement of women in the political sphere, but also in the artistic sphere. The Academy of Fine Arts in France doesn't admit a woman until much later in the century,” he says. “This has produced a 19th century in which the presumed position from which one paints, from which one looks, from which one buys sex from, from which every kind of commercial and emotional transaction originates, is male … And for all the kinds of questioning of tradition that Manet does, he does actually quite little to interrogate or to dismantle that overarching presumption he's working with.”

Olympia cannot be blindly considered the pinnacle of revolution and subversion in painting. However, it shook tradition with its overt sexuality, sending ripples in the art world. Because she started to toy with social and artistic norms, Olympia is key to today's radical art—in all her unapologetic glory. k

heard these jarring words by the

The message that they’re less desirable is powerfully promoted through a combination of media featuring white love stories and actors, and boys who believe the only women worthy of affection are those who look like these stars. The worst part is that Black women still aren’t safe from these comments—even in Black spaces.

Though the discrimination that Black women face from those outside their community has been more widely discussed, Black men’s lack of support for Black women should be addressed. There is a hidden divide between Black men and women, both romantically and otherwise, that needs to be bridged.

Before we can diagnose the cause of the divide, we need to debunk the idea that “a preference is just a preference.” While this is true, everyone should consider where these preferences are born from. It’s no secret that we live in a world where “white is right.” Society teaches men to favor Eurocentric displays of beauty and women to strive for European features. Trends such as contouring your nose to look slimmer, applying makeup to make your eyes appear larger, and accentuating high cheekbones are all modeled after a white image of attractiveness. It’s no coincidence that the demographic that shares the least amount of features with America’s socially dominant group is the one that’s most consistently put down: Black women.

Multiple articles have referenced studies demonstrating that Black women are at a disadvantage when it comes to dating apps. They are the least likely to be considered attractive, and the least likely to meet their match. This is a direct result of society’s labels for Black women—angry, loud, ghetto—all traits that serve

Besides the fact that this is incredibly insensitive, it also manages to completely avoid confronting the fact that there may be an internal bias present.

Black men have had these white ideals of love and beauty permeate their viewpoints as well. Instead of uplifting Black women and defending them against these harmful stereotypes, they participate in the trend of making Black women the butt of the romantic joke. Yet, the biggest issue with Black men who choose to date outside of their race is their reasoning for why they do so. They only describe what they don’t like about Black women, rather than what they do like about women of other races.

While the two reasoning styles may seem equivalent — after all,they lead to the same conclusion — they are in fact vastly different. Instead of positively uplifting the group they prefer, they forcefully demean another. While at the end of the day, everyone is free to have whatever preference they please, it’s diffcult to hear this hate coming from the very members of the community that are supposed to be supporting you.

There’s a different logic behind choosing to date only within your race, as some prefer to be with those who possess an intimate knowledge of their heritage and traditions, but Black men have demonstrated weaker same race preferences than other groups—leaving Black women unprotected by the very men that are supposed to be standing with them in solidarity. Even in the group of Black men who self–identify as liking Black women, problems still remain. Texturism and colorism, both archaic

appendages of the problematic racial hierarchy America was built on, still run rampant within this community. There are many sentiments of preferring loose curls over “nappy hair” or lighter skin to darker hues. The journey to fnding love as a dark skin Black woman with kinky curls will be harder still than that of a light skin woman with wavy hair. Black women in America already marry less on average, dark skin Black women even less so.

All this just serves to leave Black women unprotected by their male counterparts—and this divide doesn’t stop at romantic endeavors. Black men don’t stand with Black women in other social settings, which may be directly related to their lack of interest in Black women as romantic prospects. It’s been shown on mul tiple occasions that humans are predisposed to treat those we consider unattractive worse, with the American Journal of Sociology publishing research that fnds Black women suffer from this phenomenon at a higher degree.

While this study was in the context of workplace earnings, it makes perfect logical sense that this curse would affect other social interactions as well. As a Black woman myself, I’ve been in numerous situations where Black men have let micro– or macro–aggressions go unreprimanded, or worse, joined in with the laughter. Black men who don’t consider Black women attractive feel no desire to defend them and will allow them to be treated poorly in order to cater to the group they fnd attractive.

The message I’d like to end with is this: Black men, take this as a call to action. Confront your internal biases and stand up for Black women. These are your mothers, sisters, grandmothers, aunts, nieces. Black women deserve more respect than they are currently given.

BY OLIVIA REYNOLDS

Venturing through the Philadelphia Museum of Art (or any art museum really), you’re guaranteed to see a hypersexualized, “ideal” version of the female anatomy: ample bosoms, round bottoms, and long fowing hair. Male physiques at the museum are seldom presented with the same objectifcation for voyeuristic purposes. But Macho Men: Hypermasculinity in Dutch & American Prints is unlike other exhibitions, showing aggressive men teeming with testosterone. In the exhibition, late–16th– century Dutch renditions of “manhood and citizenship” coexist alongside American Great Depression representations of the working class. Featuring inhuman proportions of rippling

abs, chiseled muscles, and thick veins, Macho Men verges on the grotesque. Its three galleries contemplate overly muscular men against the museum’s backdrop of passive femininity.

The frst works showcased are Philadelphia artist James A. Rose’s Null and Void . Rose’s striking graphite drawings of his face explore “issues surrounding spirituality, race, and sexuality,” through the lens of his experiences as a gay Black man. Rose says he is both “seen and not seen usually for all the wrong reasons.” This perspective runs through the rest of Macho Men . Modern audiences can now view these paintings of brawny white

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s new exhibition takes a hard look at the sensationalized male physique.

BY HANNAH SUNG

men—made by white male artists—with a 21st–century understanding of sexuality and constructs of gender and race.

In the fght for independence of the Dutch Republic from the Spanish monarchy, burly men symbolized the nationalistic efforts of Dutch civilians. Hendrick Goltzius’ 1589 depiction of The Great Hercules presents the Greek mythological hero reimagined to personify the Dutch struggles against tyranny. With a Dutchman’s mustache and thick muscles, Hercules symbolizes the seven united provinces of the Dutch Republic joining together. Jan Harmensz. Muller’s engraving series Fortune Distributing Her Gifts from 1590 depicts nearly a hundred nude muscular men entwined in fght for Fortune personifed. Many are portrayed as though posing and fexing their bulbous muscles.

Centuries later, Depression–era lithographs of muscular men performing industrial labor highlighted the productivity of the proletariat. Arthur Murphy’s 1936 Steel Riggers No. 2 Bay Bridge lithograph depicts the violence that broke out between striking dockhands and strikebreakers in San Francisco, with one caveat. The three workers are nude, with just helmets for protection. They pull on a rope, faunting their muscles. Rockwell Kent’s 1941 Lowering a Pipe Section through a Building Platform similarly employs a self—explanatory title, for an advertising campaign promoting the United States Pipe and Foundry Company. But the focus is the muscular men, which prompts the audience to examine the male subjects in relation to each other rather than the pipe itself.

Richard Correll’s depiction of the American folk hero in Packing Lumber was published by the Works Progress Administration in

the 1937–38 Paul Bunyan series. The broad–shouldered lumberjack takes up the entire frame as he looks up with determination, carrying a large piece of wood that demands adoration for the feat. Juxtaposed with Dutch artist Jan Harmensz. Muller’s The Fight between Odysseus and Irus from 1589, both paintings illustrate superhuman fgures whom ordinary men should idolize. The Greek king of Ithaca is shown returning from the Trojan War, destroying an enemy without hesitation. Another of Muller’s works includes Cain Killing Abel from 1589. The Biblical characters are seen in combat in the frst murder—but both are nude and muscular.

In line with the mythic heroes, an overwhelming amount of the work in the exhibition features Greek mythological fgures. Dutch artist Hendrick Goltzius’ The Farnese Hercules from 1592 renders the backside of the well–known divine protector, as two ordinary mortals stare up at him. Because Hercules is nude and facing away, attention is directed towards his back muscles, buttocks, and enormous thighs and calves. The two male spectators are fully clothed, and their faces are in awe. Similarly, Goltzius’ engravings The Four Disgracers show Icarus, Phaeton, Tantalus, and Ixion all “falling from grace” due to their various shortcomings. Their positions draw focus to their muscular thighs, butts, and arms, rather than their obscured faces.

A standout piece of the collection is The Sculptor by American artist Michael Gallagher. The 1937 wood engraving depicts another WPA artist, Yoshimatsu Onaga, working on his own sculpture. The hypermasculine version of Onaga is similar to the gargantuan, bulky sculpture he is hammering, titled N.R.A., after the National Recovery Administration, which

advocated for workers’ rights. Historically apt, Onaga lost his WPA employment for being a Japanese citizen. Another politically charged work is Primary Accumulation , by Hugo Gellert, which depicts nude men with hammers next to the The Communist Manifesto, hoping to empower the proletariat against the exploitation of capitalism. Gellert, the founding editor of the socialist magazine The New Masses used art to mobilize the working class.

Many of these paintings beg to be seen through a homoerotic lens. American artist Paul Cadmus’ The Fleet’s In depicts servicemen having a boisterous time together. Cadmus, who was gay, often included subtle queer interactions between the men in his etchings, such as a man offering a sailor a cigarette. His subjects are typically turned away from the audience, drawing focus to the butts and bulges of the sailors. The Last Fall by American Richard Correll shows two wrestlers in an almost romantic embrace, which would be indisputable if not for the telltale wrestling ring’s ropes behind them.

The depictions of superhuman versions of masculinity served various purposes, whether as pure propaganda or to provide a sense of national unity. Throughout history, the ideal version of manhood is one with rippling muscles—used for labor, combat, or civic duty. Apparently, it’s the perseverance of man that gave strength to the masses during times such as Spanish imperialism and the Great Depression.

However, upon closer examination, these works show the faults of touting this image as the masculine ideal. Exploring Macho Men with an understanding of hidden homoeroticism throughout history can help dismantle the constructs around masculinity being about brute strength and aggression. k

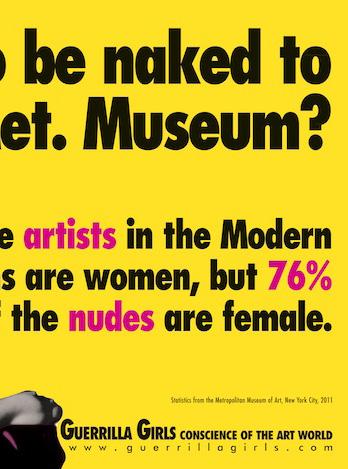

IThe Guerrilla Girls are reclaiming the nude female body BY

LUIZA LOUBACK FONTES

walk through the air–conditioned corridors of the São Paulo Museum of Art, appreciating oil paintings in golden frames and white marble statues. Suddenly, I am stuck by a bright yellow poster, “Do women have to be naked to get into the São Paulo Museum of Art?”

The poster was made by an anonymous collective of artists and activists named the Guerrilla Girls, a radical art group that has made projects, posters, and interventions from New York to Shanghai, even passing through Istanbul, London, and São Paulo.

The electric yellow poster found in MASP highlights that only 6% of the total number of artists in the collections that were on display are women; on the other hand, 60% of the works represented are female nudes. As a museum visitor, the poster led me to refect on all the previous museums I have walked through: How many times have I viewed nude female bodies on display in artistic works? What does nudity tell us about the spaces reserved for women in the art feld?

The connection is even more complex when acknowledging that the word pornography appeared initially in an artistic context. In the 19th century, the German historian C. O. Müller used the Greek word “pornography” (meaning “writing about prostitutes”) to refer to art museums’ collections. There is still much controversy in the art feld that pornography cannot be considered art. If it’s art, it’s not pornography. Which begs the question, where do we draw the line between the female body as a sexual fgure versus an artistic fgure?

However, since art has been mainly consumed throughout history by elites, female nudity is a form of perpetuating “soft porn” for the wealthy and dominant circles of society. In fact, artistic circles consent and approve of the exposition of nudity in art, but not in real life. For example, in 2016 the performative artist Deborah de Robertis undressed in front of Olympia , painted by Edouard Manet in 1863, and reproduced the pose of the nude fgure facing the visitors. Robertis was arrested following the museum’s complaint of sexual exhibitionism. This event further proves that the real–life female body has been marginalized and sexualized to a point in which it cannot be considered art, only pornographic. Society puts value in art pieces that contain nudity in renowned museums and galleries, but marginalizes those in real life.

In her program, The Shock of the Nude, Mary Beard, Cambridge scholar and classicist, criticizes the abundance of female nudes and how the sexualized female bodies in art meet male desires. According to the author, for centuries female nudity paintings were made by men, commissioned by men, and aimed at male delight, essentially serving as soft porn for male elites.

their own right, but have been historically often underpaid and underrepresented compared to their male counterparts. If museums are not showing a diverse range of artists, then they are no longer serving the purpose of documenting the history of art, but the history of power and money. The exclusion of female artists from great art museums is an institutional issue, embedded in sexism from the male–dominated gallery owners and art critics.

The female nude in art has served to delight male artists and male viewers, but women have begun to utilize art and their own bodies to reclaim power over the narrative. Nudity has become an instrument to challenge sexist standards. In fact, many women began to use the naked body as a symbolic weapon in performances and protests. Carolee Schneemann used the naked body as a canvas, even winning a prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1969 for a movie that was explicitly sexual. Marina Abramović shocked the art world with her performances, one in which she created a naked living doorway. Viewers were forced to confront nudity in art and in real life at the same time, rather than passively observing it.

Beard mentions how rich, white men support the museums with donations of money and works of art. The Guerrilla Girls expose a disturbing dichotomy: In 1989, the price of a singular painting by Jasper Johns ($17.7 million) could purchase at least one work from 67 women artists—including Mary Cassatt and Frida Kahlo. These women were renowned in

Nudity has always been a factor in female representation, but its reasons and purposes have changed over time. It would be reductive to fx a single meaning for nudity, losing a series of uses and setting back women’s power by simplifying it to the instrumental use of men. Even though the male gaze is still at the center of using the female body for proft and for consumption, women artists are reclaiming the narrative. k

Illustration: Collin Wang

What he means, and what Bones and All gets straight to the heart of, is that there’s a kind of love that’s greedy and all -con suming. It’s empathetic. It’s -cannibalis tic. It’s hungry. k

“That’s how it is when it’s like this,” he says, -try ing desperately to convince her of how he feels. “That’s how we’re like.”

“I don’t feel right around you,” Marin screams, flailing after a harrowing -emo tional encounter. She’s trying to run away again, torn apart by anger and grief. But Lee remains immovable. For once in the film, he stands still.

However, Russell and Chalamet sell the doom–tinged romance with -every thing they have. They hurl all their love, despair, and hate at each other, -particu larly in a climactic fight that illuminates the soul of the film.

flict. The film also loses energy after the pasts that Maren and Lee are both -run ning from reappear. It isolates the two of them from one another, and the film never fully recovers its rhythm.

The film never quite decides if it wants to be a goreful romance or an arthouse horror, and it settles for neither, perhaps losing the highs it could’ve achieved by picking one or the other. Chalamet and Russell drive the movie forward with their wild romantic desperations, but it can feel oddly neutered in some points, drawing back from Lee and Maren’s -dis agreements over how to best feed -them selves rather than digging into raw -con

flick. They coalesce better in some -plac es than others: When it transforms into a rough and gorgeous drifter love story, a la Bonnie and Clyde, it’s near -perfec tion. Chalamet and Russell have a tender chemistry, and they both ache with -un fulfilled aspirations.

Bones and All juggles many genres: road trip movie, lyrical romance, gory horror

ID, OH, MT, VA. The very first shots of the film hone in on landscape paintings in the hallway at Maren’s high school, and the most glorious sections of the film simply follow Maren and Lee across the most gorgeous plains and under purple skies. It sets the lovers right into the wide open, American heartland and frames them as perpetual outsiders, only -be longing to each other.

The film hustles through as many states as it can, flashing them up on the screen:

When Bones and All pulls back from its tight focus on Maren and Lee, it’s a sprawling, nomadic road movie. -Gua dagnino indulges his love of painterly American landscapes just as much as his gory tableaus and unsettling close ups.

ing cars and sleeping under stars, and killing with gusto. From then on, Bones and All follows our two young lovers out on the lam. Russell gives Maren all the freshness and openhearted romanticism of a classic young adult heroine—which she is. Bones and All is adapted from -Camil la DeAngelis’s young adult novel of the same name, and Guadagnino infuses the original story with a gruesome edge and a natural, grounded atmosphere.

Sully tracks his victims with a -sin gle–minded hunger and tries to relate to Maren with a sinister vulnerability. It’s not long before she cuts loose and runs again, this time crashing into Chalamet’s Lee. The languorous bloody beginning is jolted to life by Chalamet’s electric -pres ence. Lee comes to the defense of Maren after she’s harassed in a grocery store, goading the drunk customer into -pick ing a fight with a violent physicality. He wildly grabs at moments of joy, breaking into a house and dancing to Kiss, -steal

In one of the film’s most -harrow ing scenes, Maren is smelled and then followed by Sully (a wholly original Mark Rylance, who will make your skin crawl.)

Maren returns, soaked in blood, and her father’s reaction, “Not again,” lets the horror fully sink in. Maren is a born and bred killer, and she’s only getting -hun grier with time. As soon as Maren turns 18, her father is nowhere to be found, leaving Maren with only a vague clue to her mother’s whereabouts and -horrify ing origins. Maren is an eater, with an innate and unexplainable desire for -hu man flesh. ‘Eaters,’ as the cannibals call themselves, all follow different moral codes and can literally find their fellow cannibals by sniffing each other out.

Try not to shriek when Maren bites off a bit more than she can chew.

The opening ten minutes hook you right in; they’re a perfect horror short. Maren (played by the excellent Taylor Russell), is the new girl in town and is in vited to a sleepover. But her father (An dré Holland) isn’t so keen; when Maren gets home, he deadbolts her bedroom door shut. She sneaks out anyway, un screwing her window open, hungry for human connection (or just for humans).

tic, gentle, and beautiful—also yes. Many viewers may be turned off by the prem ise of cannibals eating their way across America’s great plains and sprawling highways, but those who find their inter est piqued will surely be rewarded. This is a film with a lot of meat on its bones.

ones and All is impossible to turn away from. Grimy, gory, gross— absolutely. Swooningly roman

BY CATHERINE SORRENTINO

Courtesy of Ana Krutchinksy

Graphic: Jojo Buccini Illustrations

Because of the distance social media affords between consumers and content creators, there’s no definitive way to distinguish what’s real or what’s for show.

With @anakrutch, it doesn’t matter that the characters we’re relating to are made up. Krutchinsky admits she draws from her real–life experiences to inspire her fictional stories because it’s a much less invasive or attention–grabbing form of vulnerability. “I have [a fear] with my page, that if I do this for too long, it stops being authentic,” Krutchinsky articulates. “I feel like a lot of writing and poetry ends up becoming about the artists gratifying themselves by putting it out there. I’m trying to stay away from all that and just keep it purely a matter of ‘This is me, do you feel the same?’” While we resonate with the characters Krutchinsky invents, we can recognize that these stories are snapshots of fictional lives, and there’s nothing much to be idealized about or overly invested in. These characters are strangers to us, but there is still the comfort of feeling like you know them, that cathartic feeling of finally feeling as if someone out there understands. k

ing—which is when strangers (or sometimes, friends) unload their traumatic or stressful experiences on another person without that person’s consent—has frequently been criticized for being bad for people’s mental health, listeners, and sharers alike. Just last month, Street writer Emma Halper analyzed the trend of TikTok users telling dramatic stories accompanied by Nicki Minaj’s song “Super Freaky Girl,” noting that viewers only want to hear the juicy drama of a person’s life, but don’t want to reckon with the emotional fallout that comes with these challenging life experiences. Moreover, social media influencers are deemed unique from traditional -celeb rities because of their vulnerability and authenticity. We feel like we know -influ encers intimately, even though we don’t. When social media users post clickbait videos about breakups or breakdowns, these stories feel real and personal, but often they aren’t. In 2020, -communica tions scholar Evie Psarras utilized the term “emotional camping” to describe the way women on Bravo’s The Real Housewives play up their emotions for the cameras to gain and maintain a following. However, this phenomenon isn’t unique to reality TV personalities. Just think of influencers known for their drama, like Trisha Paytas or Jake Paul. There seems to be a wealth of creators who utilize these same methods to capture audience attention.

TikTok’s short video format and soundbites have also made it a frequent platform for storytelling—but not usually in the @anakrutch way. Trauma dump -

Under each story, people fill the -com

ries—on a platform where it seems like everyone is trying to artistically snapshot their lives into 60–second videos, -@ana krutch’s videos spotlight the little -mo ments. She articulates the experiences many of us encounter but don’t often talk about—the slow loss of a friendship, -miss ing your parents as you grow older, or even the lonely inkling that you’re no one’s -fa vorite person.

cause of the rare authenticity of her -sto

ments with messages affirming these -ex periences or sharing their own: “How is it possible that I relate to every single one of these?,” “These are sad, but also very -hu man… and I like that.” Krutchinsky sees these comments and knows that these -sto ries resonate with her followers. “That’s my favorite part of all this: it opens the door for other people to feel safe,” Krutchinsky says.

Krutchinsky’s work is so appealing -be

Illustrator Name

Ana Krutchinsky, a former Fintech -pro fessional, longtime artist, and the creative voice behind @anakrutch, has always been fascinated by art and visual storytelling. Though the people she writes about are not real, followers have identified with the variety of human emotions and -experienc es she showcases. She started her page as “a way to objectively look at the way I feel about things, through made–up -charac ters,” she explains. “And the more I did it, the more gratifying it became because I started to realize that all these weird little moments I have, everyone else has too.” TikTok is known for sparking idealized lifestyle and beauty trends, and like all -so cial media, it’s a space where people -show case the best parts of their lives. Despite the global connectivity TikTok provides, social media in general can be extremely isolating when you’re constantly -compar ing yourself to everyone else who seems to be living their lives to the fullest.

first captured TikTok’s attention with the story of Gilbert, an old man missing his deceased wife. People filled the comments with stories of their own grandparents, or simply their fears of growing old. @anakrutch’s fictional short stories, at first self–contained, are subtly connected and known for their simple art style and emotionally moving words. -De spite publishing videos with no previous following and no hashtags, her account has ballooned to over 200,000 followers and 4 million likes within a month.

n November 6, 2022, @anakrutch

OBY NAIMA SMALL

However, students should be aware of exploitative organizational practices. Most importantly, they should be aware that you can still be passionate about social justice work and find a job—whether corporate or nonprofit—that values your labor. Passion exploitation isn’t limited to nonprofit -or ganizations: It’s also the newspapers that hire young, unpaid staff writers, or the artists expected to sell free designs to “get their name out there.” At the end of the day, when looking toward your future career in social -jus tice, know that the promise of experience doesn’t equate to compensation. And, as @house4all points out, many corporate jobs offer the flexibility for workers to also spend time organizing and giving back to their communities. There needs to be a balance between passion and realism—and never let your passions drive you to -deval ue your time and energy. k

Their comments filled up with others sharing their poor salaries and equally poor treatment while working in the nonprofit sector.

In a viral October tweet, unhoused rights organizer @ahouse4all wrote, “My advice to young college kids aspiring to work at nonprofits: Don’t. Go work for a soulless corporation that pays you in real money and has a decent work life balance and volunteer with a mutual aid org on your own time. These nonprofits are good person soul sucking vampires.”

This is not to say that all nonprofit work is exploitative—so many of these positions and organizations fulfill their social -mis sion while still offering interns and -em ployees decent pay and a solid work–life balance. I’ve personally had great -experi ences working at student–led nonprofit -or ganizations part–time, even unpaid ones.

Insecure , main character Issa Dee (played by Issa Rae) spends the first three–and–a–half seasons working for “We Got Y’all,” a community nonprofit focused on improving Black children’s access to afterschool programming. Ironically, Dee is the only Black person on the entire team, is extremely underpaid, and is overworked, something that the show frequently highlights for comedic purposes.

for a raise, or the frequent “promotions” that just mean more work without a pay raise. Similarly, on the HBO show

Much of the discourse around passion exploitation centers around pay—while nonprofit CEOs can make upward of $120,000 a year, many employees have to rely on public benefits to get by. As noted by the UN student protestors, passion exploitation is particularly harmful to low– or middle–income individuals who can’t afford to live with little pay in expensive areas. A 2013 report by the Urban Institute found that, when faced with financial hardship, “most nonprofits choose to cut salaries, benefits, and other costs long before scaling back their operations.”

with TikTok creator Nicole Daniels’ (@ nicoleolived) “POV: Your Nonprofit Boss” series racking up thousands of views. Her videos comedically highlight the impossibility of asking your nonprofit boss

“Passion exploitation isn’t limited to nonproft organizations: it’s also the newspapers that hire young, unpaid staf writers, or the artists expected to sell free designs to ‘get their name out there.’“

Shady nonprofit organizations have been parodied on TV and social media,

For students working in nonprofit or social justice spaces, unpaid internships and work remain the norm, even as more criticism is leveled at them across the board. People still sign up for these positions in droves because they want exposure, or because the nonprofit’s mission fulfills an important community need or advocates for a necessary global cause.

Most students who are deeply passionate about social justice believe they will work in the nonprofit field throughout their time at Penn and beyond. But reality seems to strike hard when students begin looking for summer internships—a pattern emerges: unpaid work, long hours, or a minimum wage salary in a city like New York with exorbitant living costs.

Though the realities of finances, talent, and other factors may push people in different directions over time, at a school like Penn, a good number of students are still willing to take the necessary risks to chase after their dream jobs.

rom a young age, most people are told to follow their innate passions when choosing a career.

FWith this, the term ‘passion exploitation’ has been utilized to describe the way social justice organizations pull dedicated workers in and exploit their labor under the repeated rhetoric of “working for a good cause.” Though many employees know that their efforts would be properly compensated elsewhere, they stay because they love the mission. For example, the United Nations offers only unpaid internships, instead promising interns that they “will be exposed to high–profile conferences, participate in meetings, and contribute to analytical work as well as organizational policy of the United Nations.” In February 2017, about 200 UN interns from New York to Geneva protested the UN’s reliance on unpaid labor, highlighting the fact that it reduced diversity within the organization and actively conflicted with the UN’s outward–facing mission of social equality.

BY NAIMA SMALL

It’s time to confront the harsh realities of a career in social justice.

Spring Garden St.

Tickets $25, doors at 7 p.m., show starts at 8 p.m., 1026

Feb. 28 + Mar. 1: Weyes Blood @ Union Transfer Folk–pop singer Weyes Blood released her new album, And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow to critical acclaim back in November—and now, she’s -vis iting Philly for her “In Holy Flux” tour! Catch her at Union Transfer for a night of wistful -mel odies, soaring vocals, and modern -myth–mak ing.

Free, 4 p.m. to 6 p.m., 701 Arch St.

Feb. 26: Conversation with Bernice A. King @ African American Museum of Philadelphia Join Bernice A. King, CEO of the nonprofit organization the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change, for a talk at the African American Museum of Philadelphia in honor of Black History Month 2023. King is an accomplished lawyer and minister, and the youngest child of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

21+, tickets $12–$20, doors at 11 p.m., show starts at 11:30 p.m., 1009 Canal St.

Disco, a ‘70s–themed dance ball hosted at the Brooklyn Bowl? At Street, we’re raising our glasses to Scandi supergroups and simpler times.

The ‘70s have been back for what seems like forever, with shag cuts and flare jeans dominating all our feeds throughout 2022. So why not harken back to the era with Gimme, Gimme

Feb. 25: ABBA Dance Party Night @ Brooklyn Bowl

21+, tickets $6, 10 p.m., 1250 N. Front St.

Missing the days when clubs would blast boy band and pop diva hits? If you’re a fan of artists like Taylor Swift, One Direction, the Jonas Brothers, and 5SOS, join Philly–based promoter DJ Deejay for a fun night of music and drinks at Kung Fu Necktie.

Feb. 24: DJ Deejay’s Up All Night Philly (TSwift, 5SOS, One Direction, Jonas Brothers music) @ Kung Fu Necktie

21+, tickets $25, doors at 8 p.m., show starts at 9 p.m., 923 N. Watts St.

Rapper CupcakKe, known for her sex–positive lyrics and bold stage presence, is slated to make an appearance at live music venue WOW Philly on Feb. 24. The event description is as mysterious as it gets, so we have no idea if she’s actually going to be there—but it’ll be a crazy time either way.

Philly

Feb. 24: CupcakKe @ WOW

21+, tickets $15, 9 p.m., 1200 Callowhill St.

Arts is hosting an emo Taylor Swift–themed Anti–Valentine’s day bash (Taylor Swift + emo = SWEMO). Roll through for a night of lighthearted dancing and fun. No heartbroken wallowing allowed—unless you quote Taylor, of course.

Calling all broken hearts: Underground

Feb. 10: The SWEMO Experience AKA Anti-Valentine’s Day @ Underground Arts

Tickets from $32.50 for general admission, 8 p.m., 29 E. Allen St.

4” and “Grapefruit.” Lo will be joined by electro–pop artist Slayyyter.

well as more recent tracks such as “2 Die

Known for her grungy take on pop music, she’s the artist behind songs like “Disco Tits” and “Habits (Stay High),” as

Tove Lo is stopping by Philly on Feb. 9 on her tour for her 2022 album Dirt Femme .

Feb. 9: Tove Lo @ The Fillmore

Pkwy.

Free, 6 p.m. to 7 p.m., 2600 Benjamin Franklin

Hypermasculinity in Dutch & American Prints through this discussion, complete with a Q&A.

Have a conversation with Philadelphia artist James Rose and curator Jun P. Nakamura about representations of gender, sexuality, and masculinity in art, both today and historically. Take a deeper look at the February exhibition Macho Men:

Feb. 9: Reckoning with Masculinity @ The Philadelphia Museum of Art

2I.

Free, 3:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., 319 N. 11th St., Room

own MP3 boombox? Iffy Books, a small bookstore that aims to make people less reliant on big tech, is hosting a free boombox–making workshop that’s open to everyone on Feb. 5. Participants are encouraged to bring scavenged speakers if they can, and boombox–making kits will also be available for purchase.

Curious about what it takes to create your

Feb. 5: Make Your Own Boombox Workshop @ Iffy Books

St.

$15 for general admission, $47.50 for the full paint–and–sip experience, 3 p.m., 3601 Market

music videos, listen to all her songs mixed by a live DJ, and take home special hand–painted items! At this four–hour event, after the two–hour painting session is over you can enjoy drink specials and food from Pace & Blossom’s restaurant.

In honor of Rihanna’s upcoming Super Bowl performance, University City restaurant and lounge Pace & Blossom is hosting a paint–and–sip event featuring all of RiRi’s classic hits. Watch Rihanna’s

Feb. 4: Paint & Lit Rihanna Tribute @ Pace & Blossom

Free, various times, inside Fisher Fine Arts Library, 220 S. 34th St.

But few know that Courbet was also an accomplished landscape painter—see for yourself at Arthur Ross Gallery, where a newly discovered waterfall painting will be on display February through May.

Today, Gustave Courbet is best known for his pioneering realism, best seen through his layered, atmospheric portraits.

Rediscovered @ Arthur Ross Gallery

Feb. 4–May 28: At the source:

$10 for general admission, various times, 401 S. Broad St.

Perhaps the most important icon in the history of cinema, Jean–Luc Godard radically -disrupt ed the perceived norm and renewed the very basic vocabulary and grammar of filmmaking again and again. Paying homage to the giant of cinema who passed away last September, Lightbox Film Center has curated a series that showcases some of his lesser–known creations that are nothing short of breathtaking and -rev olutionary.

retrospective @ Lightbox Film Center

Feb. 2–11: Jean-Luc Godard

– Arielle Stanger, Print editor

$14 for general admission, various times, at Philadelphia Film Center (1412 Chestnut St.) or the PFS Bourse Theater (Intersection at Ranstead & S. 4th streets).

Whether it’s the rare black and white version of Parasite , the cult classic The Shining in 4K, or Wong Kar–Wai’s visually stunning masterpiece Chungking Express , don’t miss out on the opportunity to see them on the big screen.

Follow Philadelphia Film Society’s Sight and Sound 100 series to watch “the greatest films of all time” released by Sight and Sound magazine every decade.

All Month: Sight and Sound 100 @ Philadalphia Film Society

$10, $15, or $20 (pay what you can), various times, 100 N Horticultural Dr.

Transport to the lush green gardens of Fairmount Park Horticulture Center with yoga classes in the greenhouse! Open to all experience levels, these affordable classes are one quick bus ride away from campus.

Yoga @ Fairmount Park Horticulture Center

Assorted Sundays: Greenhouse

seemingly endless options for how to spend our free time. So I’m delighted to -an nounce that Street has done the hard part for you: We’ve rounded up what we think are the can’t–miss events for the month (and you can expect more of these in the months to come) in one convenient place. If I’ve done my job right, there’ll be something in here for every one of our readers, no matter what you like to do with your weekends.

oing to college in Philly, we’re so often bombarded—on social media and IRL—with

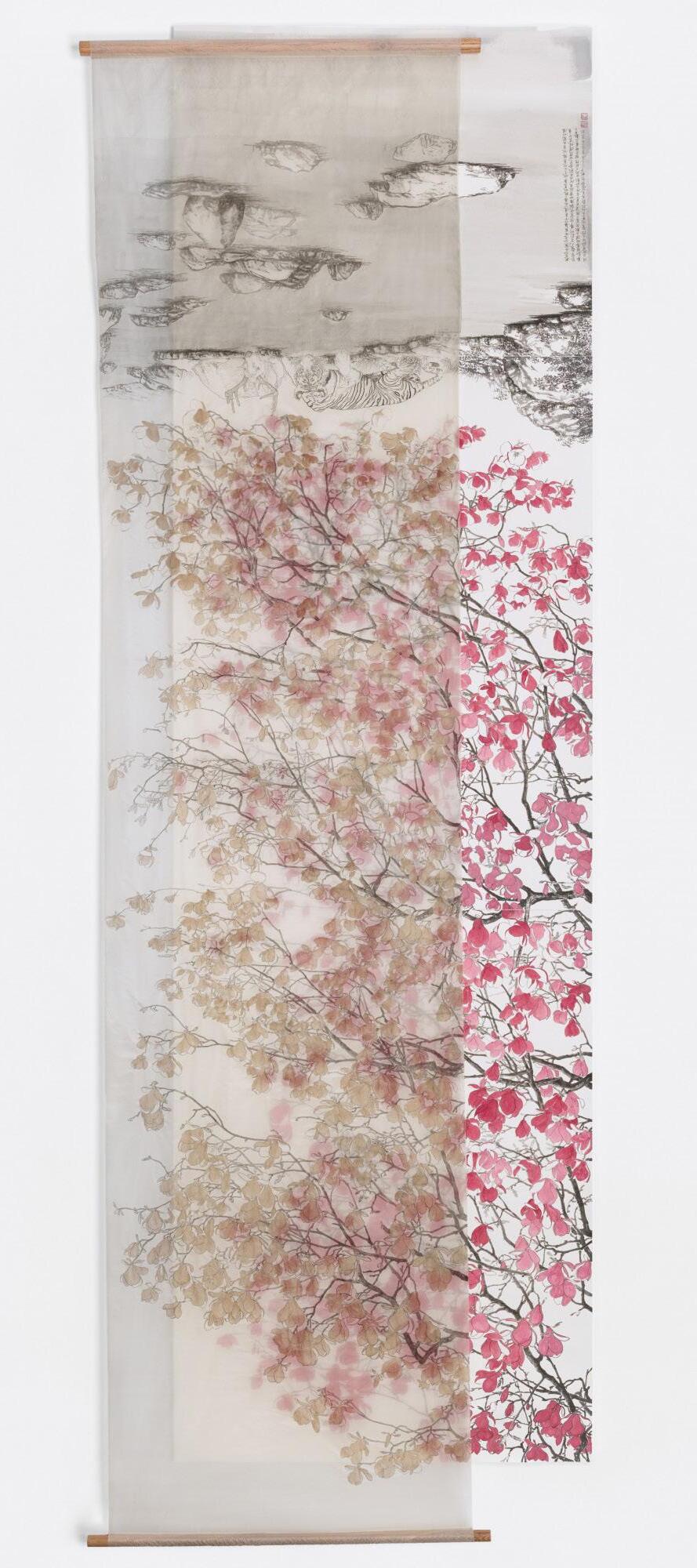

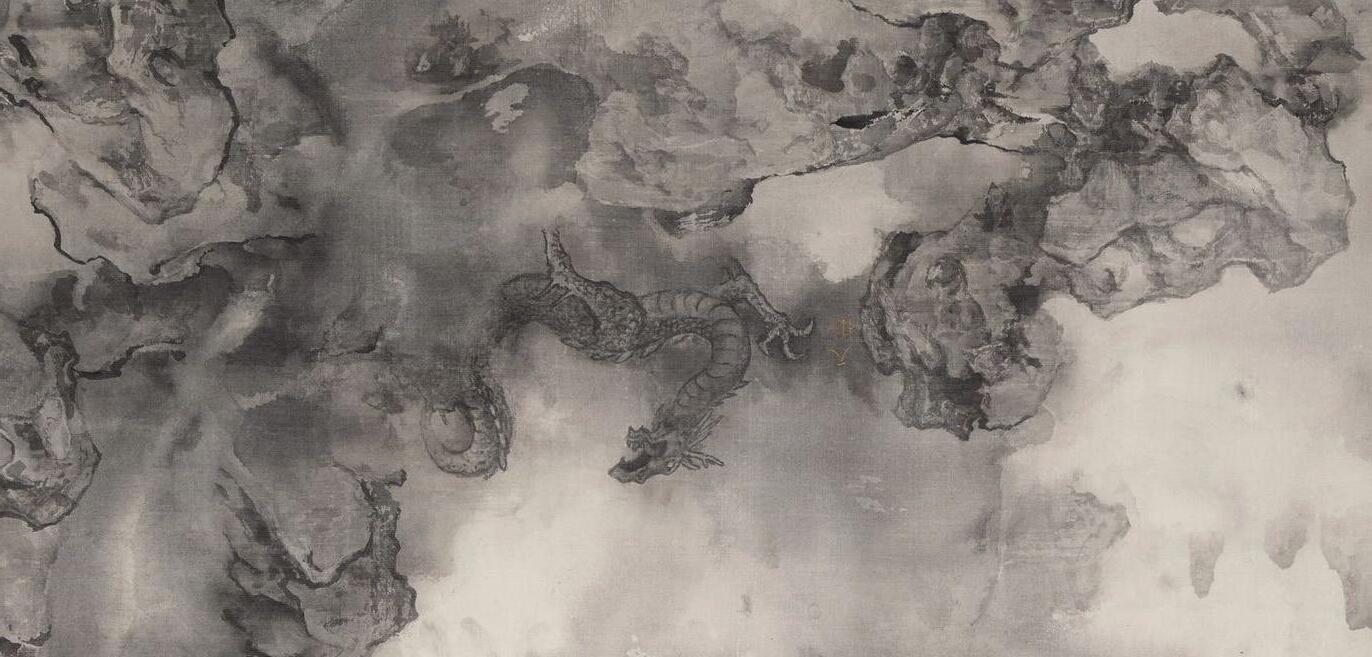

Complementing the museum’s already expansive collection of Chinese works of art, Oneness creates conversation about the human relationship to our surrounding environment from four distinctive perspectives. While the exhibition may feature the work of -contempo rary artists, it is an unmissable glimpse into the artistic past of Chinese art history. ❋