Offering 60+ eateries, stores, and entertainment venues, Shop Penn has what you need to stay warm this season.

Winter calls for comfort food and cozy essentials, so get your cold weather cures at Shop Penn.

Shop Local. Shop Penn.

Wants Needs + Must-Haves

5 1 8

22 Why Women Yearn For Male Yearning

Women are loving Heated Rivalry—and it’s not just for the sex.

30 Love on Command

Penn students climb it, protest at it, and confess on it. But the LOVE statue was always asking what it means to love in a commodified world.

Ego of the Month: Briana Cantero

Briana Cantero gets candid about love and personal growth.

Weathering Forecasts: As Climate Shifts, a Neighborhood Braces

How Eastwick residents grapple with changing federal priorities, health consequences, and more in the face of frequent flooding.

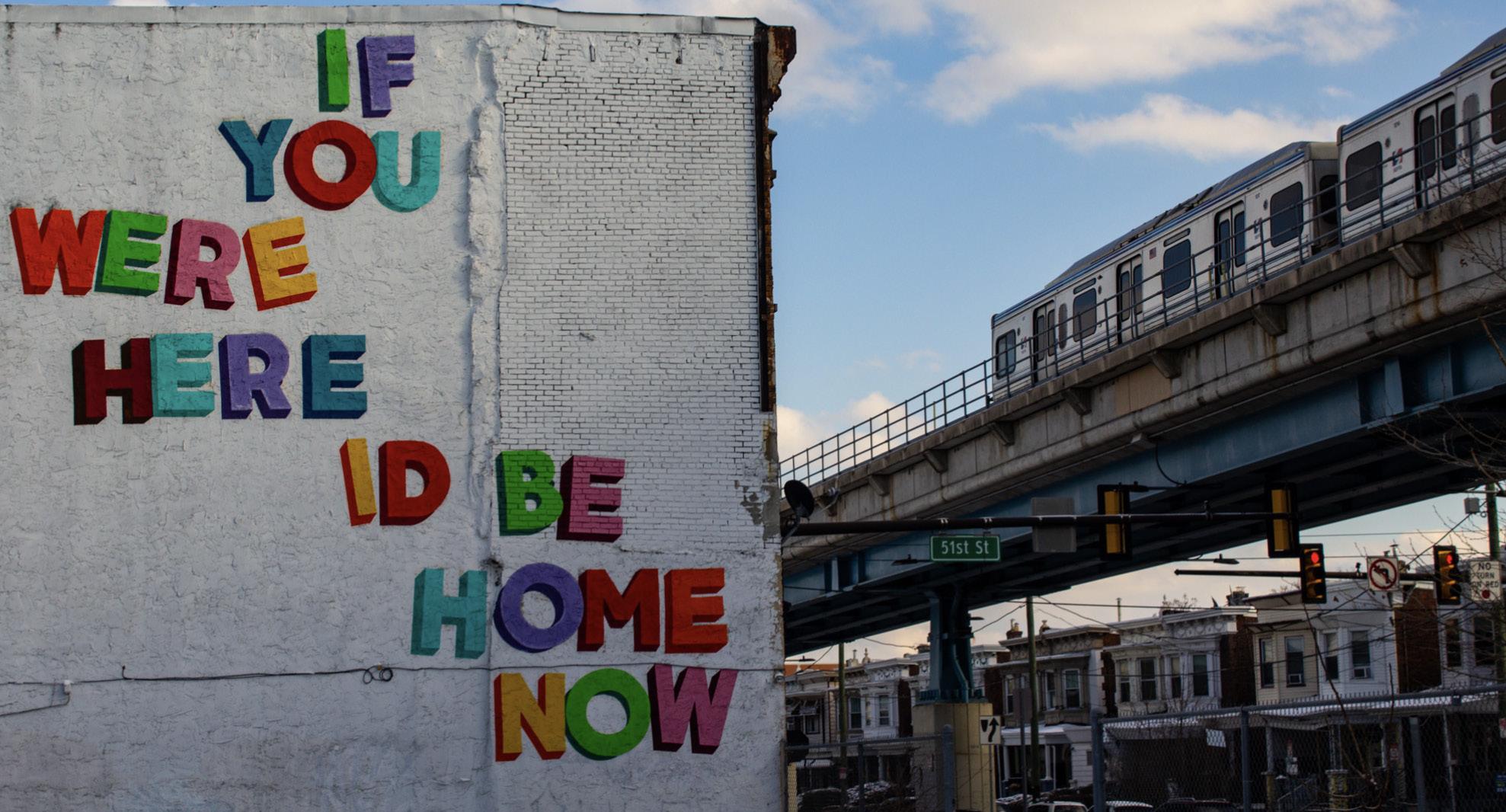

36 Love on the Walls Philly’s heart—and where to find it.

14 34 The ‘Office Siren’: Professionalism in Practice or Corporate Cosplay?

The viral social media fashion trend isn’t as bad as we may think.

Street Sensuous Bureau

Street’s new survey finds that Penn’s dating scene is decadent and depraved.

ON THE COVER I like to think meet–cutes are remembered through the heart, not the mind. You’ll forget about it, until you twist and tangle and run parallels along the strings of fate and meet again. Or not.

By Kate Ahn

I used to think that love would announce itself, that I would meet someone and know immediately whether it was love, that it would be so clear and unmistakable I couldn’t ignore it. In the poems I wrote, the books I read, and the films I watched, I looked for love, hoping that I might one day recognize myself in the people I was writing, reading, and watching.

But that expectation never aligned with my real life. At 20 years old, I am frankly unsure if I’ve experienced romantic love.

What I am sure of, though, is that the most important relationships in my life didn’t announce themselves when they began.

They entered as moments that I almost missed. A seat taken beside me in a lecture hall because there were no others left, and suddenly I had a friend who understood the loneliness of being so far from home. A conversation outside a party that stretched longer than it should have, past midnight and into the cold, neither of us willing to say goodbye first. A walk home where we got lost from too many detours through unfamiliar streets, until the aimless wandering itself became the memory I kept returning to.

This issue explores love through the lens of “meet–cutes”—not necessarily the promise of romance, but those strange, fleeting moments when someone enters your life without any explanation. Some grow into romantic love, while some become friendship. Others dissolve into nothing but a memory of what could’ve been. All of them, though, are beginnings. All of them change who we’re becoming, even if we don’t know it yet.

I frequently think about the beginnings I’ve never asked for that have unraveled into something more: the people I met at New Student Orientation, when I was still nervous and trying too hard; the faces I learned while wading through the cornfields of the Midwest, where everything was vast and infinite; my high school friends, whom I only became close with because we were struggling together in chemistry class; the wom -

an I befriended on the plane who offered to connect me with someone at Apple if I ever wanted to work in tech (I don’t); the acquaintance I made at a Kelly Writers House speakeasy.

Maybe that’s what makes meet–cutes so compelling—that they remind us of how little control we have over our lives. How love, in all its forms, often begins not with clarity or certainty, but with chance.

Whoever you are, whether we still know each other or have long since drifted into our separate lives, I hope our paths cross again someday.

And to you, the reader—maybe we’ll meet sometime soon, too.

SSSF,

EXECUTIVE BOARD

Nishanth Bhargava, Editor–in–Chief

Samantha Hsiung, Print Managing Editor

Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief green@34st.com

Sophia Mirabal, Digital Managing Editor

Jackson Zuercher, Assignments Editor

Kate Ahn, Design Editor

Arielle Stanger, Print Managing Editor stanger@34st.com

Alana Bess, Digital Managing Editor bess@34st.com

SECTION EDITORS

Sadie Daniel, Features

Collin Wang, Design Editor wangc@34st.com

Ethan Sun, Features

Sarah Leonard, Focus

EDITORS

Chloe Norman, Focus

Avalon Hinchman, Features Editor

Henry Metz, Film & TV

Jean Paik, Features Editor

Mira Agarwal, Music

Natalia Castillo, Assignments Editor

Laura Gao, Arts & Style

Kate Ratner, Assignments Editor

Insia Haque, Arts & Style

Anna O'Neill–Dietel, Focus Editor

Fiona Herzog, Ego

Naima Small, Style Editor

Norah Rami, Ego Editor

Hannah Sung, Music Editor

THIS ISSUE’S TEAM

Irma Kiss, Arts Editor

Executive Editor

Weike Li, Film & TV Editor

Jasmine Ni

Rachel Zhang, Multimedia Editor

Copy Editors

Kayla Cotter, Social Media Editor

Prashant Bhattarai, Jessica Huang

Street Photo Editor

THIS ISSUE

Connie Zhao

Deputy Design Editors

Julia Fischer, Copy Editor

Deputy Design Editors

Wei–An Jin, Ani Nguyen Le, Sophia Liu

Eunice Choi, Kiki Choi, Chenyao Liu, Amy Luo, Andy Mei, Julia Wang

Design Associates

Insia Haque, Alex Nagler

Insia Haque, Katrina Itona, Erin Ma, Janine Navalta

STAFF

STAFF

Features writers

Features Staff Writers

Katie Bartlett, Delaney Parks, Sejal Sangani

Focus Beat Writers

Maddy Brunson, Diemmy Dang, Kayley Kang beats

Leo Biehl, Dedeepya Guthikonda, Sara Heim, Sophia Rosser, Rahul Variar

Style Beat Writers

Melody Cao, Ana Laura Citalan Limon, Vasanna Persaud, Saanvi Ram, Jessica Tobes Film & TV beats

Layla Brooks, Emma Halper, Alexandra Kanan, Claire Kim, Felicitas Tananibe

Music Beat Writers

Julia Girgenti, Susannah Hughes, Shannon Katzenberger, Sophia Leong, Chenyao Liu, Élan Martin–Prashad, Liana Seale

Music beats

Kelly Cho, Halla Elkhwad, Ryanne Mills, Olivia Reynolds, Mehreen Syed

Arts Beat Writers

Leo Huang, Remy Lipman, Drew Neiman, Amber Urena, Joshua Wangia, Brady Woodhouse

Jojo Buccini, Jessa Glassman, Eyana Lao

Style beats

Film & TV Beat Writers

Jordan Millar, Alex Nagler, Addison Saji, Adalia Vargas, Jason Zhao

Mollie Benn, Kayla Cotter, Emma Marks, Isaac Pollock, Catherine Sorrentino

Arts beats

Ego Beat Writers

Sophie Barkan, Noah Goldfischer, Ella Sohn, Vikki Xu

Anjali Kalanidhi, Jack Lamey, Aaron Tokay, Lynn Yi

Ego beats

Staff Writers

Rodin Bantawa, Sophie Barkan, Jackson Ford, Dedeepya Guthikonda, Jaya Parsa

Staff writers

Morgan Crawford, Heaven Cross, Angele Diamacoune, Rayan Jawa, Enne Kim, Jules Lingenfelter, Luiza Louback, Dianna Trujillo Magdalena, Yeeun Yoo

Audience Engagement Associates

Emma Katz, Jenny Le, Suhani Mittal, Irene Antón Piolanti, Henry Planet, Namya Raman, Alena Rhoades, Tanvi Shah, Sara Turney, Diamy Wang

Annie Bingle, Ivanna Dudych, Yamila Frej, Lauren Pantzer, Felicitas Tananibe, Liv Yun

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni–Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

CONTACTING 34 th STREET MAGAZINE

CONTACTING 34 th STREET MAGAZINE

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief, at green@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

If you have questions, comments, complaints, or letters to the editor, email Nishanth Bhargava, editor–in–chief, at streeteic@34st.com. You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

www.34st.com © 2023 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

www.34st.com © 2026 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

Philosophy, politics, and economics, minor in music

Cuban American Undergraduate Student Association, Penn Social Entrepreneurship Movement, Consult for America

Penn admits more than 2,000 of the most accomplished students across the world every year. Despite their varied skills and accolades, a majority of these students share the same, unifying struggle: finding true love. Much like her peers, Briana Cantero (C ’26) is an incredibly talented multi–hyphenate, juggling her obligations as the president of Penn CAUSA with the consulting grind—but those accomplishments weren’t the focus of our conversation. Briana instead confided in Street about perhaps her most coveted achievement—her six–year–long relationship—and the lessons that came with it.

How did you and your boyfriend first meet?

We met in high school. I was a sophomore, and he was a senior, but we only had a one–year age gap. I wanted to join the National Honor Society, and he was the vice president. He came into my AP World History class when I was a freshman, and I thought he was very goal–oriented. I really looked up to him, and I felt like that was something that a lot of the guys in my school lacked. So, I kind of made it a point to make myself noticeable to him, and I just straight up DMed him on Instagram. I was like, “Hey, do you like, do you watch anime or something?” He was like, “Yeah, I’m watching My Hero Academia, but I don’t really like it.” And then on top of that, we talked at school. He was very shy. I really liked that. I thought it was so cute. And then he asked me out Nov. 2, 2019. Our first date was at a movie

Briana Cantero gets candid about love and personal growth.

BY INSIA HAQUE

theater, and it was so cute. It just felt like innocent teenage love.

Tell me a little bit about your boyfriend. What do you admire most about him?

He noticed the little things. That’s something I really admire. Our first Christmas together, he remembered that I had mentioned finding a book at the library in second grade that made me cry when I had to give it back, though I couldn’t remember the name. I told him the book was about Mozart. I was a musician and played piano, so I had always been into Mozart. The book had such a cute, cartoony style, and the details about the melody of the birds reminded him of the song he was writing at the time. Eventually, he found the name of the book, and bought it for me.

I’ve had grand gestures before that, but they were very generic. This was very intentional— he wanted me to feel special. And that’s when I knew that he was the guy I was gonna marry. Basically, I was like, I have to keep this guy.

What would you say has been the hardest part of dating long–distance?

The hardest part was when we were both in different colleges and feeling like there’s a part of his life that I don’t know about, that I’m not present for. There are inside jokes I’m not gon-

na get. But honestly, he made me feel so wanted. His friends already knew so much about me and thought so highly of me when I visited him at Stanford, and that really reassured me.

How do you make time for your relationship, considering your workload?

You can always make time for things that are important to you. The average Penn student, their day is extremely packed, right? But they still find themselves at the end of the day, scrolling on Instagram reels or TikTok. So, during the 15 minutes before bed, when I could be on TikTok, I’ll just FaceTime him. Or, like, for example, right now he’s working in the immigration court in Miami, so he’s driving an hour and a half each way. But on the drive, he’ll call me, and then we talk while I’m making dinner or something like that. Those little moments really do add up. I spend so much time talking to my boyfriend despite us being long–distance.

How has growing individually impacted your relationship?

The silver lining of being long–distance is that you get to immerse yourself in your own hobbies. I’ve discovered things that I never knew I’d like just by spending some time on my own at Penn. At first, it was hard. I was extremely codependent, but making time for your own hobbies

and your own friends—those two things are very important. A lot of long–term couples always say, “Oh, our friends,” or “we like this movie,” or “we don’t like this movie.” As someone who’s been in a relationship for six years, I despise terms like “we this,” “our that,” because at the end of the day, he’s his own person. What I liked about him was who he was as a person before he met me. So why should we combine ourselves into this one thing? If we like each other for our individuality, it’s counterproductive.

How do you navigate differences in career paths and life aspirations?

My boyfriend is actually applying to law school right now. But, I don’t want to go to law school. We’ve been talking about how long I’m going to stay in Miami, because I do have a return offer at a job there, and I want to move back and stay with my family for a while. It takes a lot of compromise. I’m going to have to sacrifice being with my family for however many years. But I feel like it’s worth it, just because he’s so important to me. At the end of the day, it’s literally just because he’s so important to me.

That said, if you have a partner who you don’t think is worth compromising for, I don’t think you’re being selfish. If your priority is to be free and move wherever you want, that’s your prerogative. You shouldn’t feel guilty if you think

you have to end a relationship or put a pause on it just because you want your desires first. But I just happen to want to be where he’s at. It’s all about agency and always remembering that you have control—that in your life, there’s nothing tying you down.

What’s a controversial opinion of yours on dating?

I feel like when women make the first move, everything flows a lot better. In fact, I tell my friends to make the first move on a guy. It makes them feel safer—there’s no chance of that buffer of like, “Oh, does she like me? Do I approach her? Am I gonna be made fun of?” So, just approach the guy that you really like, but it has to be a guy that you really like. You approach him, and then you let him do the rest of the work.

According to the Street dating survey, two–thirds of Penn students have been in a situationship, but a majority have never been in a long–term relationship. What are your thoughts on dating culture at Penn?

I hear a lot of complaints from my friends in terms of situationships. Oftentimes it’s just people not being clear with each other and not setting boundaries and intentions from the beginning. Or one person will be very clear about what they want, and the other person assumes there’s a cryptic meaning behind their message.

I feel like ego also gets in the way of a lot of these things. Like, “Oh, because they didn’t text me back for like, three days, I’m not gonna text them back for like, three weeks.” If you think they’re playing games with you, you might as well just ask them straight up, just to stop yourself from wasting so much time. You’re already so busy, climbing your way to success at Penn in so many different ways. Why are you gonna let something so small hold you back? If people could just ask the questions, cut and dry, that’d be ideal.

From that same survey, most Penn students date to marry, or for a long–term relationship, but the majority of students struggle to do so. Do you have any advice for Penn students trying to find the one?

I think everyone should have a pretty

extensive list of things that they prioritize in someone and things that they won’t put up with. Oftentimes, I see girls talking to someone, and they notice a lot of red flags, but they’re already in so deep that it’s like, “Well, now I really like him, I’m catching feelings, and it’s really hard to get out.” So, if you’re already two weeks in, have agreed to be exclusive, and see him talking to another girl, instead of giving him another chance, just cut him off. Remember your list of priorities. Remember what you said when your head was clear, when you weren’t down bad. Remember what love–sober you would have said. You know yourself well enough not to accept things that you already know you don’t want. Obviously, there are caveats to this. Like, if your list is like, “he needs to be 6’5,” that’s not what I mean. Think about what really matters 30 years down the road, who you would see yourself with, helping you through the death of your parents or something as drastic as that. You don’t want to have to baby someone

when your mom is in the hospital, you know, because those things are going to happen in life.

And any advice for the lucky few Penn students in committed relationships?

I feel like a big thing is to never let a day end without saying “I love you” to each other, or comforting each other, even when you’re angry at each other. Don’t use any adjectives to insult each other. Don’t say things like “Oh, you’re being rude, you’re being annoying, you’re being manipulative.” Separate the situation from the person, because many of the things they do are behaviors they learned growing up—things you can identify without applying an overarching term during an argument. Also, never bring up stuff from the past that has already been resolved, just to get “points” in an argument. That’s a big thing that happens a lot, even in friendships, where you’ll bring up something that happened a long time ago just to win an argument. k

What’s the secret to a healthy relationship? Being unconditional with each other. Don’t breach the social contract of respect you share.

Worst romance cliché?

The belief that “Oh, he cheated on his last girl, but he won’t cheat on me.” Cheaters are cheaters.

What’s the soundtrack of your relationship?

The La La Land soundtrack—we really like La La Land. The ending made both of us cry.

Best date spot in Philly?

Giuseppe & Sons, and then a walk around the block and through Rittenhouse Square.

Fuck, marry, kill: philosophy, politics, and economics?

Marry politics, definitely. Fuck economics, honestly. Kill philosophy.

There are two types of people at Penn… Butterflies and moths

And you are?

A moth. I would say moths can be a little more introverted. But they’re still very beautiful and decorative, you know? They like hanging out at night.

By Insia Haque

Design by Insia Haque

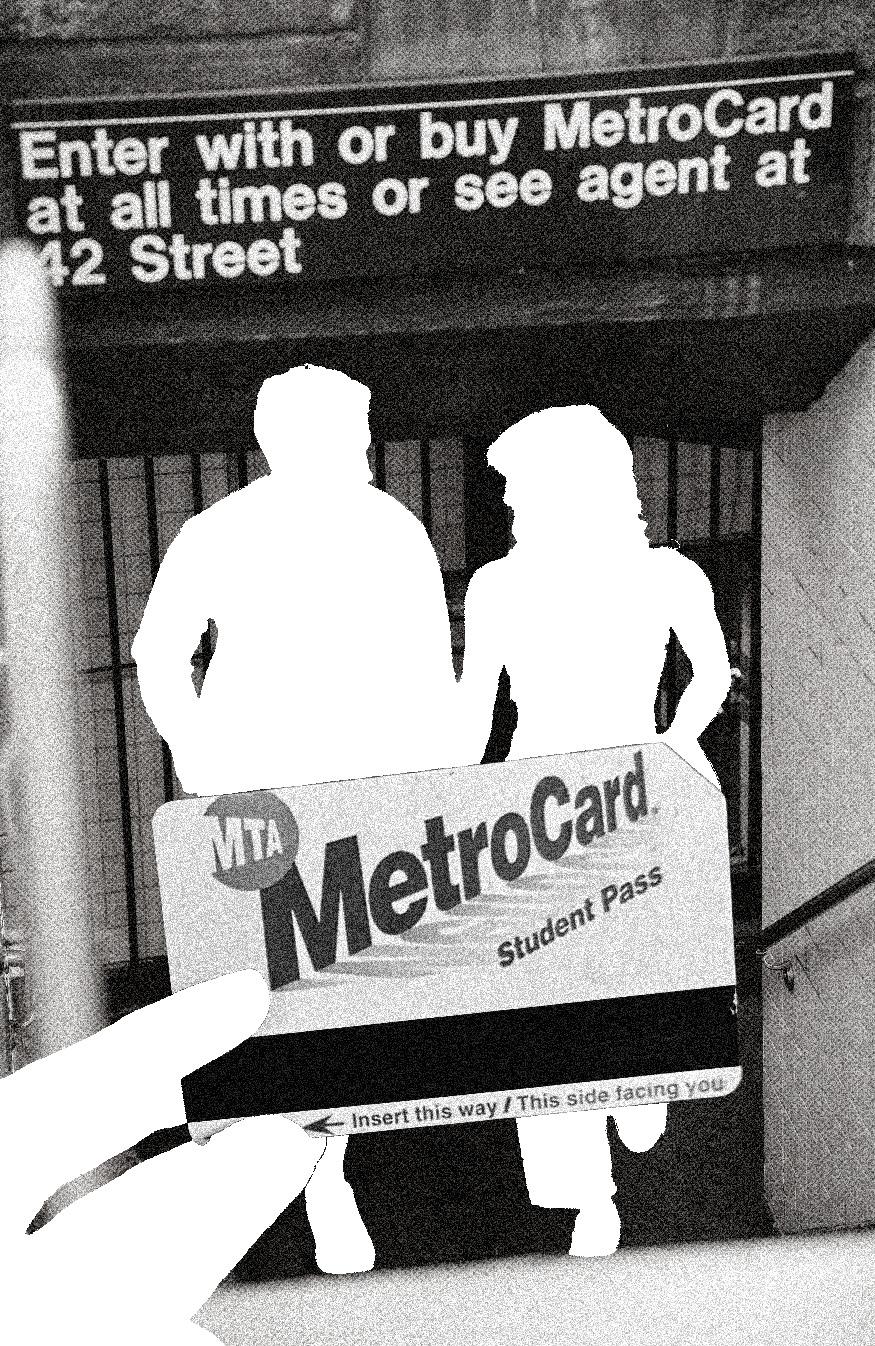

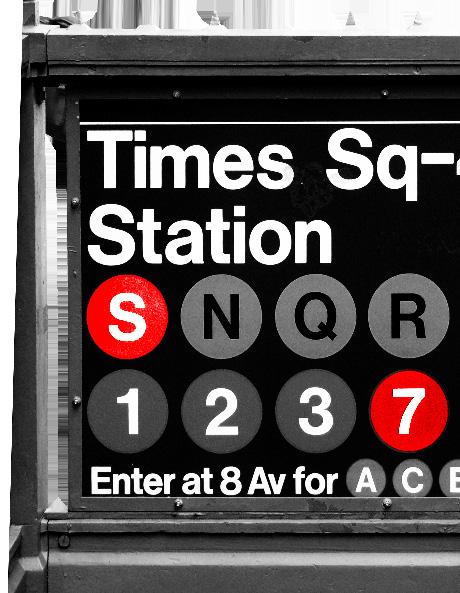

The S train on 42nd Street runs on the shortest subway line, connecting only two stops. On any given day, 100,000 people take the S, and on Dec. 26, 2018, I was one of them.

There is something inherently romantic about a packed subway car. We both reach for the pole, my fingers accidentally wrapping around yours. I jerk my hand away and stare at my boots, avoiding your gaze, but you see me fight back a smile. As the shuttle suddenly stops, I lose my balance and launch into your arms. You laugh it off, we scuffle out at Grand Central Terminal, running up and down the stairs to catch the S back to Times Square.

Your nose is practically touching mine once we cram ourselves into the sea of holiday tourists. Not a free pole in sight, I’m stuck holding onto your arm. I’m a nervous wreck, desperate to find the right words to say to you. I don’t know you yet. We’re two strangers, surrounded by 99,998 other strangers, which isn’t very different from every other day, where I’m surrounded by 99,999 strangers. But today, for some reason, I want nothing more than to make you smile.

After half an hour shuttling back and forth, I must’ve finally strung the right words together. I’d just turned fourteen, and here I am, holding your hand, strolling through Morningside Heights. I’m so excited—maybe today I’ll have my first kiss. We sit on a bench, finishing up the oiliest $2 slices Koronet has to offer. The sun’s setting, turning the city my favorite shade of dusky blue. You humor me with your plans to travel out of state and the kindest compliments I’d ever received and my laughter steams up the freezing air. My face hurts so much from smiling. Our hands are almost frostbitten, but you are the warmest person in the world.

The 7 train is the only other train that connects Grand Central and Times Square, but it takes you a little further, with twenty additional stops. I’ve always loved the 7 train. As the train leaves Manhattan and enters Queens, it finally rises above ground. The sun’s setting, filling the car with blinding, orange light.

Seven years later and seven stops away, I see you again. We share a hug. You’re so much taller than I remember. We squeeze into an N train, and once again I am forced to hold onto you for stability. It’s obvious to you that I’m just as nervous as I was all those years ago. I’m so, so afraid that this time you’ll recognize me for the fraud that I am. Maybe you’d realize all this time later that I’m still crass and unusual. Seven years later, seven stops away, and the apprehension’s all the same.

The S train on 42nd Street runs completely underground, completing its journey in just ninety seconds.

I never got that first kiss. I’ve always been so, so ashamed of myself, and so, so scared of love. Maybe it’s because of the dogma drilled into my head that loving was no less sinful than adultery. Or the knowledge of my grating, off–putting, blunt personality. Regardless, I bury my desires deep. I hide it where no one can see it, where no one can point and laugh at me for dreaming of love. Underground, perhaps. I feel a screaming, suffocating urge to lean in and bridge the remaining distance between us, but I was so, so afraid. Without the anonymity of the subway and its screeches softening my abrasiveness, how could anyone tolerate me? I bite my tongue, swallow my love; it leaves a lump in my throat.

And just like that, the train has already left the station.

Grand Central and Times Square are the two busiest stations in the city. The shuttle we so briefly shared had 15 or so transfer lines through the two stations. We part ways. I ride

more lines, I make more transfers, and I meet more people. I shared a few months with my then best friend, immediately blowing up our friend group when he dumped me the next Valentine’s Day. I finally caught the eye of the upperclassman in my debate club, but that too exploded, even more quickly and horribly. I found a longer–term love, finally, that lasted through half of college, but that too had come to an end.

I’d like to think that during these years filled with rides and transfers I’ve unlearned that shame, but maybe it’s just evolved. That first kiss has come and gone, along with many other milestones, but that sinking feeling persists: The unshakeable conviction that no matter the accolades I acquire or successful attempts at self–improvement, I will be alone in the end. That there is some invisible, intrinsic defect I’ll never overcome, and that once those kind to me notice it, they’ll flee from me. That the friendships and love are fleeting and finite, and every former friend or lover is a sign of failure. I’m still so, so ashamed of myself and so, so scared of rejection. So I keep hiding.

It’s cold in Astoria. I mess up our orders and I laugh it off, but you can tell I’m beating myself up about it. But, eventually, the jitters go away, and it’s hard to believe any time has passed. You aren’t ashamed of me. Between stories about my exes, your girlfriend, and our graduate school plans, you recall our first date in such vivid detail. I’m elated— and it hits me, after all those years, that maybe I’m not doomed. That despite my failed pursuits of love, or perhaps because of them, the world isn’t as lonely as it once was.

The New York Subway sees four million people everyday. As you wave me goodbye, smiling ear to ear behind the windows of the closing doors, I can’t help but smile back, knowing that there’s one fewer stranger in the subway. S

By Anonymous

Design by Amy Luo and Andy Mei

Ihave terrible luck with the date Dec. 31. Six years apart and somehow uncoordinated, two of my hometown best friends proclaimed love confessions to me on this day.

The second time, the gesture is incredibly sweet. My heart sighs a little—how could it not?—but my head gently chides, “You can’t have this. You know you go back to Philly in two days.” I force myself to smile politely.

In my creative writing seminar, we joke that dating a writer must be hard, not knowing whether your next move will be immortalized in writing like an ugly hair-

cut. You might become the bad guy without knowing. Hell, I want to protest, it’s not like that. All any artist wants is to be someone else’s muse instead of just a creator all the time.

When it finally happens, I want to let myself say yes so badly. I want to surrender my big city dream and choose the small town because it means being with him. The concept of us was born from suburban daydreams anyway, our backs melded with my baked driveway while plucking teardrop stars from the Milky Way, Andromeda, Orion. I chose his best friend the first time

around, but that never mattered. We laugh through six years of shared pickup truck rides and unannounced “are–you–home” drivebys, all our wanting long collapsed into blissful pretend. So yes, choosing him is a mantra I recognize with my eyes closed, even if home is a moving target in a state small enough to be forgotten.

I tell him I fear abandonment like an inheritance carved into my psyche, that the aching, low–pitched drone in my lungs will never go away. “Let me try,” he begs.

Everything is possible in the earth–song of my imagination. For 48 hours, our me-

tropolis future sprawls out like a blueprint sketched on my palm. Mixed–race New Year’s Eve parties, holding each other when we think no one is looking, a gentle secret silvery and formless passing between us. Time chases, but we stay the same. Our brownstone in suburban Vermont, a five–minute drive from our families in Montpelier, Vt., but distant enough to call something our own. Years of Friday evenings where our fathers clink wine glasses, laughing that I finally chose him back. Saffron sunset in hues without language, our quiet joy dangling out of windowsills and into hyacinth beds, and I never want for anything more.

This man writes fanfiction about me, and I so badly want to want him back. I know I’m the bad guy, but let me protest that I tried. I tried to choose the high school sweetheart who mapped my acne scars and gnawed reticence into constellations. Loved every version of me when I didn’t, when I shrank myself smaller than statehood, a blip of teenage oblivion. Before we were “us,” we were still only me, 12, and him, 13, but one of us was always lagging behind the other, barely out of sync. One of us always searching for something bigger.

He leaves home first, but I choose not to return. As our calendars fill with everything but each other, sleet pierces my bloodstream, runs down my sides cold. So

I cleave myself from fantasy, lurch back to this festering reality. I tell him the truth: I have always wanted something greater than home. In this life, my soul sledgehammers city sidewalks and heaves down skyscraper ambition despite my asthma. The yawning maw of urban possibility is an infection I can’t relinquish, drunk on the chase of something more temporal than Main Street and Montpelier Church and the illusion where we got married at 22 and never looked back.

In response, he snorts. “Don’t worry. I won’t wait around for you anymore.” Or something like that. The phone line glitches in and out while he drives back to Vermont suburbia, which wraps its familiar arms around him. “But I’ll always love you.” I try to formulate a response of equal emotional caliber, but really, I know that “always” is too big a promise to make, especially to someone more than friend but less than lover. I want to tell him I’m sorry. You were always too close to home, always more fiction than material.

My present is much less forgiving. My body in its first urban snowfall, sprawled out like the vast city I lose myself in, night spurting out jagged and red. A different boy asks if this is my first time; I lie and say no because I want him to want me. He still

doesn’t. “I never loved her,” he tells his new girlfriend, young with sprightly eyes, full moon dew and willing to give him everything I wasn’t.

Whether another six years later or now, this becoming is the only truth I know about myself: a cigarette clasped between my fingers instead of a ring, a backless dress framing the windowsill with frigid evening, the stench of absence rendering my lips green. All the times I begged for love, just to flee when it arrived shaped like my best friend. In this life, I’d finally been chosen, but walked away. What

“I want to tell him I’m sorry. You were always too close to home, always more fiction than material.”

then? What do I tell myself to keep loving? What if all my choices lead me back to this loneliness? What if I’d just settled for the simple life, surrendered small freedoms now, if it meant that I could hold this future with both hands and know that, finally, it is more real than imagination? S

“Fiona, I’ll leave now— I don’t want to take up too much of your time.”

Whether I’m waiting between classes or sitting at home waiting for dinner to be ready, my grandmother ends every phone call the same way. These calls last barely three minutes. No matter how often I insist that she could never take up my time, she hurries to hang up, as if her love must be given in small, unobtrusive doses. And yet, in spite of previous worries of taking my time, like clockwork, she calls again the next day.

Dementia and the unyielding passage of time have reshaped the dynamics of my family in ways I am still struggling to find my place in. Not only has dementia taken pieces of my grandmother’s memory, it has altered her sense of self. Once defined by fearless in-

dependence and nonstop action, she now organizes her days with caution and repetition, haunted by the belief that her presence is a burden—even to the people who want nothing more than to spend time with her.

My grandmother was once unable to be restrained as she freely jetted around the world. One week she mailed me Olympics merchandise from South Africa. Another week it was a cat sweater from a boutique in France, tucked alongside a pencil topped with a miniature Eiffel Tower. Even when I visited her in her house in Syracuse, N.Y., she allowed no time for lethargy. Jet lag was irrelevant. My grandmother woke me at 7 a.m. to make breakfast, get our nails done, shop for clothes, run errands. Every hour was filled. I didn’t yet understand how empty Syracuse would feel without her momentum propelling it forward.

I once defined her life by motion and agency. Now, the only remnant of that motion reveals itself in how she walks.

At The Nottingham, the senior living community where she has resided for just a year,

the only remnant of her former independence reveals itself in her pace. As she grips my arm to guide me to her daily 4:30 p.m. dinner, she marches swiftly through the halls, pulling me forward, impatient with the measured pace of assisted living. Even as her world narrowed, there is a trace of the urgency she once carried, as if her body remembers a tempo her surroundings no longer require.

I once knew my grandmother loved me because she used every tool at her disposal to engage me. Sometimes it was through interests she believed I should have, such as encouraging me to practice French by sending storybooks across the country to Los Angeles. Other times it was by nurturing the passions I discovered myself. When I became preoccupied with environmentalism in middle school, she mailed me books, forwarded articles daily, and recommended educational programs. I mistook these actions as spontaneous expressions of love, never considering the time and effort required behind them. Now, that expression of love has dimmed. The energy that once lived behind the scenes

of listening, researching, and planning has faded. My grandmother spends her days playing solitaire alone in her room, calling only the people she already trusts. When we talk, she repeatedly asks what I study, where I go to school, what day of the week it is, carefully affirming the answers as though anchoring herself to information that dementia has claimed. After the routine 4:30 p.m. dinner, she prepares for bed, ending her days early. Her world has shrunk—and with it, her willingness to claim time from others.

When I stayed with her in The Nottingham, she insisted I return from the gym by 7 p.m., afraid of the dangers in the secure halls occupied by senior living residents. The building that now contains her life feels dangerous to her in ways the world never did. When something goes awry—the heater breaking, the television remote becoming misplaced—her anxiety takes over as

she retreats inward, becoming less willing to see family. This fear feels foreign against someone who once thrived on the necessity of navigating things beyond her control. Independence once meant movement, exposure, and risk. Now, independence is found in repetition, predictability, and early nights alone. What used to be confidence in the unknown has hardened into anxiety around the smallest disruptions.

I am afraid of the time we have left in this new reality. I can feel panic ripple through my family as we try to maximize every remaining moment. This winter, we flew from Syracuse to Los Angeles, then within 24 hours, boarded another plane to Taiwan to spend a precious few days with my aging grandmother on my mother’s side. Time has become something to chase as it slips away.

nurturing my interests has come to an end. Now, it is my responsibility to spend precious time simply sitting with her, waiting, and sometimes just breathing alongside her. We watch the news together in the afternoon, eat simple meals of bread and cheese (accompanied with a glass of wine), letting the quiet between us stretch without urgency. When we are physically apart, I am the one to constantly send information on what I am learning, books I think she’ll find interesting, and photos and videos on all the exciting adventures I embark on.

The time my grandmother once spent

Loving someone whose identity has changed so drastically requires learning a new language of love. It also asks me to change, to release who my grandmother once was and who I once was with her. Love and time, even as they grow quieter, still ask to be honored—in patience, presence, and three uninterrupted minutes at a time. S

The viral social media fashion trend isn’t as bad as we may think.

BY JORDAN MILLAR

Illustration by Katrina Itona

They say to dress for the job you want, not the job you have, right? For what feels like an eternity, the corporate world has been recycling the same, age–old saying as golden career advice. It assures us that by putting enough effort into our appearance and exuding professionalism at all times—no matter where we stand on the corporate ladder—we move one step closer to obtaining our career goals. Through the rise of the “office siren” aesthetic,

young women in corporate spaces are putting their own creative spin on the classic idea of “dressing for success.”

Like many of today’s microtrends and aesthetics, the “office siren” grew out of TikTok in fall 2023. The trend quickly gained popularity for turning basic corporate style on its head, reimagining traditional workwear pieces through a highly sophisticated, feminine, and alluring lens. The “office” portion of the trend’s name

comes from its grounding in typical corporate workwear pieces for women: blazers, tailored trousers, button–downs, pencil skirts, and heels. However, it is the “siren” portion that adds depth to it, bringing in a sense of bold femininity and subtle yet powerful sensuality.

The trend was inspired by a nostalgic longing for ’90s and Y2K corporate–inspired fashion carried out by designers like Calvin Klein, Donna Karan, and Dolce & Gabbana. TikTok

aesthetic pages even created mood boards and image slideshows of those they deemed pioneers of the “office siren” trend in the media, from supermodel Gisele Bündchen’s character Serena in The Devil Wears Prada to Jo Frost in Supernanny With their pulled–back low buns, narrow glasses, and sleek corporate style, these figures embodied a proto–“office siren” aesthetic.

Over the years, we’ve seen several microtrends attempting to reshape professional style emerge and dissipate from online consciousness: It’s the circle of life. Long before the “office siren”, there was the “girlboss,” a phenomenon that developed during the mid–2010s that exalted the figure of the bright–eyed, ambitious, career–oriented woman working her way towards securing a seat at the male–dominated table. “Girlbosses” were driven leaders, thinkers, employees, and entrepreneurs, epitomizing female empowerment and success. With the “girlboss,” corporate power–dressing became saturated in “millenial pink,” a term coined by Veronique Hyland. From Elle Woods (Reese Witherspoon) in Legally Blonde to beauty company Glossier’s signature pink brand color, “millennial pink” went hand–in–hand with the girlboss, signifying that pink (not just any shade of pink), which often represented femininity, could be reclaimed and coexist with “boss” energy.

But the “office siren” remains unique among its predecessors and microtrend peers. Terms such as “corporate core” and “corporate chic” have been thrown around social media fashion spaces recently, all of which reimagine women’s professional wear to some extent. But the “office siren” is distinct in its emphasis on subdued yet alluring sensuality, something that is especially powerful given the constant policing, surveillance, and hypersexualization that women have historically faced within corporate settings.

Throughout 2024, popular videos started to surface of women showing off their “office siren”–inspired Outfits of the Day, characterized by neutral color palettes and pinstripe patterns. Form–fitting trousers, tailored mini and pencil skirts, fitted blouses, corset tops, snatched blazers, pumps, kitten heels, and thin rectangular–framed rectangular–framed Bayonetta glasses were among the essential clothing items and accessories that composed the aesthetic. Soon, “office siren” took over: Celebrities such as Bella Hadid and Hailey Bieber were captured in Bay-

icons of the aesthetic by fashion headlines. Prominent publications from Cosmopolitan to Refinery29 have created stylized lookbooks on how to adopt the “office siren” look. Fashion campaigns have even been classified as giving off “office siren” vibes.

Naturally, as more women began dressing in the “office siren” aesthetic, blurring the boundaries between rigid dichotomies such as the professional versus the playful and the sensual versus the modest, the trend quickly became a breeding ground for extensive public debate. This debate was particularly strong among female employees themselves. The office siren quickly went from a simple trend taking over TikTok For You pages to a catalyst for widespread conversations surrounding what women should (or should not) wear in the office.

The biggest point of contention was that “office siren” outfits were simply inappropriate for any real workplace environment. Critics

blazers over them were practically rolling out the red carpet for human resources violations and, ultimately, unemployment altogether. Some who tried to dress like “office sirens” at their actual jobs reported back to TikTok that they had been fired (whether these stories are true or not remains unknown).

Anxieties that fixate on what women wear in the workplace are nothing new. While we as a society have been conditioned to believe that corporate “professionalism” is a universal dress code, it often disproportionately targets women of color and perpetuates outdated ideals.

coming increasingly prominent. Younger employees are eager to finally enter physical office spaces and participate in the corporate American lives that they were promised, and dressing the part is important.

cut corset tops, and strapless tube tops without

Above all, those against the “office siren” trend claim that its adherents—primarily Gen Z women—are promoting a glamorized, even fetishized notion of workplace attire. They argue that adherents have likely never truly worked in a corporate setting—that professionalism seemed to be becoming lost in the shuffle of theatricality and office cosplay. This “romanticization” of the 9–to–5 comes at a time when fatigue from remote, isolated work caused by the pandemic and fears of mass layoffs are be-

Discourse surrounding the “office siren” trend often revolves around the idealization of workplace culture and whether or not it is contributing to the exact female objectification that we ought to reject. But maybe we are looking at the office siren trend in the wrong way. After all, if we truly mean it when we say “Dress for the job you want, not the job you have,” then isn’t the “office siren” trend doing exactly that? Perhaps, at its core, the “office siren” trend is simply about Gen Z women trying to find their place as the newest, most eager members of the workforce. The office siren trend allows for young, excited professional women to channel self–expression, individuality, and above all, self–empowerment, both in and out of the cubicle.

Over the course of many decades, women’s workplace attire has undergone a series of ebbs and flows. But although guidelines surrounding what is appropriate for women to wear in professional settings have shifted, women have always used officewear as a means to both resist gender–based oppression in the workplace and express their own identities.

In the early 20th century, the majority of women in the United States did not work outside of their homes, and those who did were mainly young and unmarried. Between the 1930s and ’70s, there was an increase in women—particularly married women—entering the workforce, boosting women’s contributions to the economy. As the number of working women began to shift, so too did women’s workplace attire. The 1970s marked a particularly critical turning point in fashion: In a decade grounded in feminism, women were not only leading movements to promote equal rights in the workplace but also demanding more control over their office wardrobes. While dress codes and consequences for breaking them remained strict during the early half the ’70s, feminist women strayed away from wearing super feminine attire to reject gender norms; in the latter half, they prioritized self–expression and individuality through fashion, wearing what they wanted.

The 1980s ushered in an era of power dressing: Women often donned power suits to the

office, typically consisting of vibrantly colored boxy blazers with sharp shoulder pads, blouses and matching tailored trousers, and midi skirts that symbolized female empowerment, drive, and ambition within the workplace. In the ’90s and 2000s, although shoulder pads went out of style and dramatic power suits were swapped out for more subdued, chic corporate wear (which would go on to influence the “office siren” trend), the same principles of empowerment and authority in the workplace applied. Needless to say, dress codes surrounding men’s work wardrobe choices remained relatively stagnant: For men, the rules are simply different, and double standards run rampant.

So, for decades, women have been taking the slogan of “dressing for the job you want” and making it their own, experimenting with corporate fashion as a way of defying strict gendered fashion norms and expressing themselves. The “office siren” trend is merely the latest iteration of this phenomenon. Those in Gen Z are the newest members of the workforce,

and many of them are still relatively inexperienced and struggling when it comes to navigating corporate spaces. By extension, office attire becomes a point of difficulty as Gen Z workers feel caught between a rock and a hard place: They have to choose between conforming their wardrobes to the whims of their older employers or maintaining a sense of authenticity, individuality, and personal style. Gen Z is known to reject strict gender norms and uniformity and is focused on re–imagining their lives—both in their professions and otherwise.

But for Gen Z women in particular, the workplace remains an especially challenging space. While already grappling with gender biases, youngism, a type of age bias that stereotypes and discriminates against younger people, adds fuel to the fire. Because of youngism’s prominence in work environments, Gen Z women within the corporate world are often dismissed as immature.

Despite all of this, at the end of the day, research shows that young women are eager and

ambitious when it comes to their careers. In a working world that still struggles to properly accommodate women, let alone Gen Z women, turning to corporate fashion to exercise creativity and autonomy makes sense.

Sure, there is a time and place for everything. Dress codes still exist, and professionalism is not an unreasonable expectation for a workplace setting. But, whether corporate or not, fashion is meant to be expressive. If women have always been reinventing corporate fashion over the decades, then is the “office siren” trend not simply Gen Z’s version of a storied phenomenon? Those who try to embody the “office siren” aesthetic are, like the women that came before them, trying to find self–empowerment in a corporate world that strictly polices what women can and cannot do or can and cannot be. So if the “office siren” is a form of “corporate cosplay” or “adult dress–up,” then it is perhaps creating a world where young women can (finally) freely express themselves and their individuality in the workplace. k

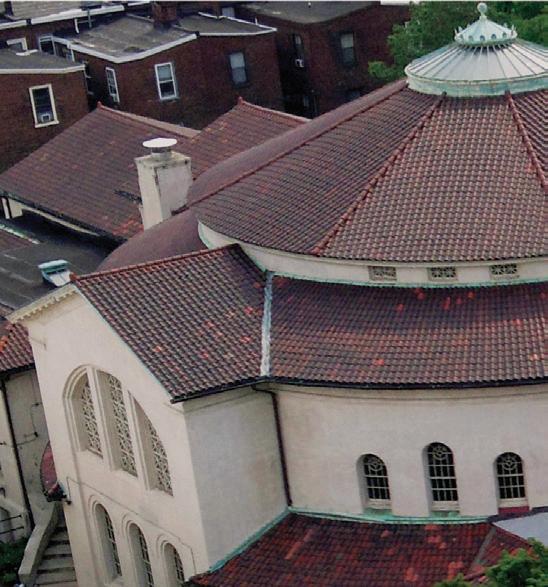

BY KAYLEY KANG

Photo by Marija Westfall

Located in Southwest Philadelphia, the neighborhood of Eastwick rests on marshland 11 feet below the Delaware River. Residents face a unique predicament when the first drops of an approaching storm paint the sidewalk: As water swells from Darby and Cobbs Creeks and combines with rushes from the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, Eastwick is flooded with up to five and a half feet of water. Just miles from the bustling streets of Center City, the neighborhood sits at the crossroads of an intense flooding crisis that will only worsen amidst a shifting global climate and insufficient governmental action.

In April 2025, a million–dollar grant from the Environmental Protection Agency to Philadelphia was terminated with little warning, an action that stands in stark contrast to the environmental justice initiatives undertaken during the Biden–Harris administration. The funding, which aimed at addressing the flooding in Eastwick and a variety of other environmental concerns, was long overdue. After the grant was canceled, funding for temporary flood barriers was halted and placed under review, and Delaware County grants for a levee project to mitigate flooding in similar regions were also cut. In response to such actions, local residents, led by Pennsylvania State Sen. Anthony Williams (D–8), took to Washington and their representatives in Congress in an attempt to fight back against the actions of the Trump administration. Neighbors deal with feelings of abandonment

and lingering questions about what the future holds, which become more pressing every time the forecast predicts rain. Community organizations like Eastwick United CDC and Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition are dedicated to raising awareness and tackling the issue. Additionally, research involving the Army Corps of Engineers is looking into practical solutions for the neighborhood‘s chronic flooding—but much work remains to be done.

From uncontrolled mold to contaminated water, the health implications of the flooding have had many adverse effects on Eastwick’s residents. “When water comes into your home [and] stays for more than 48 to 72 hours, you can reasonably expect that there will be mold occurring on surfaces like walls and floors, but also behind the walls,” says Marilyn Howarth, director of the Community Outreach and Engagement Core at the Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology. Porous materials such as wood have to be replaced. As flooring, walls, furniture, and utilities like furnaces and water heaters all get damaged, the material costs that come with flooding are immense.

“For people who live in Eastwick, which is really a working–class to middle–class neighborhood, some people cannot afford the $5,000 to $10,000 a year that flood insurance costs. And although that may not sound like an exorbitant amount of money, it’s all relative,” Howarth says. “Financial devastation really does have health implications.” With choices about which med-

ications to purchase, which treatments to undergo, and whether to pay a visit to emergency departments or clinics, working–class residents face an array of serious healthcare decisions that are made more difficult by their financial situations.

“Another thing is the mental health implications,” adds Adrian Wood, CEET’s program coordinator. “Community members have said to us before … every time it rains, [they] feel very anxious and worried that it’s going to be this devastating flood even though it might just be, you know, a small rainstorm.” The struggles caused by Eastwick’s flooding are multidimensional and difficult to alleviate with a single proposal or policy.

Eastwick is also surrounded by hazardous landfills containing high levels of heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. When residents are exposed to these chemicals during floods or post–flood cleanups, they risk a wide array of health problems, from neurological and reproductive damage to an increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and even developmental impairment in infants. In addition, prolonged exposure to mold in living spaces can exacerbate respiratory conditions such as asthma and predispose vulnerable populations to further disease and illness. “People who are on chemotherapy or have immune deficiencies for other reasons are actually at risk of becoming infected with some of the fungi that can find their way

into moldy premises,” Howarth says. The ramifications of Eastwick’s environmental conditions extend well beyond the visible signs of water damage.

The fate of neighborhoods like Eastwick remains uncertain in light of recent developments in federal policy. The Trump administration has continually dismantled climate and environmental justice initiatives, such as the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program established in 2018. Citing reservations about the program’s overwhelming concern with climate change, the Trump administration has continually tried to destroy programs created by the Biden–Harris administration to equitably allocate government resources and spotlight underrepresented communities. Such action also highlights the difficulty of striking an effective balance between local and national interests.

One example of this challenge arose when residents urged the development of a functional warning system to send out alerts specifically to Eastwick. Because flooding often occurs several hours after the rain has stopped through a chain of other circumstances, the citywide warning system usually falls short. Evacuation plans, cleanup protocols, damage repair and control, financial literacy on insurance, and even advice or safety measures for the disabled are all imperative assets to community members who may find their lives upturned with a single shift in weather conditions.

While the trials and tribulations of Eastwick residents may last well into the future, it is comforting to know that some resources are in place to help those forced to navigate uncertainty. The Flood Preparation and Management Guild for Philadelphia, created by the Philadelphia Regional Center for Children’s Environmental Health as a collaborative effort with the University of Pennsylvania and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is one project attempting to relieve the burden on residents to fend for themselves in such life–altering situations.

Whether it is through the establishment of a task force of multiple agencies or a simple volunteer organization dedicated to highlighting community voices, true recovery must begin with collective action and resilient will. And as long as residents continue to fight for the future of Eastwick, their legacy will stand strong against the waves that may threaten to drown them out. k

34th Street presents

By Sadie Daniel

Design by Kate Ahn

Women are loving Heated Rivalry—and it’s not just for the sex.

Male yearning isn’t new. Men are capable of romance–driven longing like the rest of us, but their stereotypical macho, no–feelings demeanor isn’t always broken through on the screen like we want it to be. So many of these fictional men hold back their feelings, shy away from communication, yell at their partners, and offer a half–assed love none of us deserve. However, in romances of the last decade, stories centered on male yearning dominate, and their most emotional moments are endlessly cycled online. From Theodore “Laurie” Laurence’s (Timothée Cha-

lamet) heartbreaking confession to Jo March (Saoirse Ronan) in Little Women to Peeta Mellark’s (Josh Hutcherson) painful devotion to Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) in The Hunger Games saga, women eat male yearning up. Seeing men obsessed with someone—so much that it hurts—reminds us that men too are capable of emotional vulnerability and expressing love.

That’s the appeal Heated Rivalry—the viral gay hockey show—so perfectly taps into, and why women love it so much. As Hudson Williams—who plays Shane Hollander in Jacob Tierney’s TV remake of Rachel Reid’s 2019 novel—put it on BuzzFeed Celeb: “It’s like I’m a Jeff

Buckley song in my eyeballs, except I’m gay,” he says in a nod to the world famous yearner. Shane Hollander and Ilya Rozanov—played by Williams and Connor Storrie—embody this aching kind of yearning. The show isn’t all about sex—or Storrie’s ass—no matter how many edits flood your Instagram feed. Viewers, especially longtime readers, connect with the show most through the emotional journey Shane and Ilya take, from forbidden lust to love. Storrie makes this especially clear in his guest appearance on the LGBTQ+ podcast SHUT UP EVAN, explaining that original fans of the book look not just for the sex but for how the show allows Shane and Ilya’s relationship

to progress.

The show, produced by CraveTV, spans the first ten years of Shane and Ilya’s relationship. It starts out in 2008 at the International Prospect Cup in Saskatchewan, Canada and ends in July of 2017 at Shane’s cottage, where the pair are well into their hockey careers. On the surface, the show is gay hockey smut, but when one actually takes the time to explore the progression of their relationship, it’s clear that the rival captains of Montreal and Boston’s fictional hockey teams are in it for far more than hot shower sex.

The pair meet in secret for years, hooking up in hotel rooms and secret apartments, hidden from the hyper–masculine and homophobic world of hockey. The nature of their relationship traps them in a constant state of longing—each wanting and loving the other so intensely it feels almost fatal. However, NHL backlash and potential firing aren’t their only fears. If they were to come out, Ilya, a Russian native, would be deported back to Russia, where he would likely meet a far worse fate than losing his career.

Ilya is forced to act standoffish, pretending that it’s only sex and nothing more, flinching away from forehead kisses and gentle touches as if tenderness itself will expose him. Shane, still unsure of his identity, expresses this fear differently—running from Ilya the moment things feel too domestic, too real, too close to love.

This produces a painful stretch of longing, as the pair reach closer and pull away from each other over and over again. Williams is particularly good at conveying this yearning through his eyes, a constant mention in online compliments of his craft. The pure sadness, love, and devotion shown through his eyes allows women to witness a softer side of male desire. Additionally, Heated Rivalry portrays men interested primarily in their partner’s pleasure, not just their own, something often missing from mainstream heterosexual romance where men finish first and last.

Male desire, both onscreen and in the real world, is often a source of fear for women. The sexual violence that frequently comes with it puts a painful tension of control onto heterosexual relationships. However, when women are removed from the situation altogether,

female viewers aren’t forced to relate with the female character, and can witness two individuals fall in love without confronting the risks often associated with male desire.

According to Rachel Reid in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, a lot of her female readers “prefer to not have a woman in the

“ It’s the moments in between where you see desire and this pull towards vulnerability and connection.”

book because of their own, usually dark pasts with sex with men … they prefer to get lost in a fantasy where there’s nobody there that they can relate to directly. They don’t want to insert themselves into these sex scenes. It just feels safer.” Women are drawn to the safer, softer masculinity of queer relationships like Shane and Ilya’s, which stands in stark contrast to the macho—often dangerous—masculinity many are used to.

In an interview with Them own perspective. Quoting a conversation he

had with their costume designer Hanna Puley, Storrie shares: “I think that there’s something about this type of story and this type of love and this type of sex that has a lot to do with this almost like prolonged foreplay and yearning, which kind of differs from this pornographic idea of sex.” In this way, he argues, the show is more geared toward the feminine gaze. “That’s why we like romance, you know? It’s not just the sex or whatever, it’s the moments in between where you see desire and this pull towards vulnerability and connection,” he says. Ultimately, Heated Rivalry works not just because it’s explicit, but because of the soft moments in between. Male yearning, when rendered correctly, is not about domination but emotional vulnerability—a key facet of the female gaze. In Heated Rivalry, their desire patiently aches, and their devotion to one another provides women with a form of masculinity that “feels accessible and interesting to them,” Storrie says on Them. It presents a form of masculinity that is safe and unthreatening. In a world where male desire so often objectifies women, male yearning is proof that not all male desire is dangerous.

At its best, male yearning feels like a Buckley song. It’s restrained, tender, and devastating. It’s desire that aches rather than demands. In Heated Rivalry, Shane and Ilya don’t just want

By Diemmy Dang and Ethan Sun

Design by Eunice Choi and Insia Haque

Young people are facing a loneliness epidemic. At this point, it’s a modern–day truism that feels both unshakeable and all–encompassing. Research shows that Gen Z is the loneliest generation thus far, facing rates of isolation that are higher than both those of millennials and Gen X. We don’t get out of the house enough; we don’t meet enough people; we spend too much time on that damn phone; and, as we have all for some reason been told ad nauseum, we don’t have enough sex!

This generation’s increased reliance on technology, coupled with their need for more human connections, would appear to make them most susceptible to the promise of dating apps. From Hinge to Bumble to Tinder, there are countless options to search for love digitally, and, according to a Forbes Health Survey, nearly half of Americans believe dating apps are the top spot to meet a match.

Despite this, recent years have found Gen Z flocking away from traditional dating apps, reporting fatigue and frustration towards mindless swiping and the inauthenticity fostered

by platforms that once promised to make love simpler. College students report feeling the greatest disillusionment with dating apps compared to any group, a shift in opinion that raises questions about the future of what is currently a multi–billion dollar industry.

There’s one potential answer to this question: college–specific matchmaking platforms. Services such as Penn Date Drop and Penn Marriage Pact, which have gained traction on campus in recent years, offer an alternative to the swipe–based structures of traditional dating apps. In fact, they take swiping out of the

“The pitch for matchmaking services over traditional dating apps has serious merit, and college campuses seem to be the perfect grounds to test this new model out.”

equation entirely, using algorithms to directly pair university students. Although these platforms are still relatively new, they seem to have found a burgeoning niche within the college market. In the past several years, similar platforms have proliferated across college campuses, betting that students will prefer having fewer matches and some technologically savvy way to guarantee they are paired with a compatible partner. As dating apps slowly fall out of fashion with younger users, these alternative matchmaking platforms want to be the next big thing that helps Gen Z find love.

Marriage Pact was one of the first players on the scene. The company was founded at Stanford University in 2017 and reached Penn’s campus in 2020, where it has since thrived. This past fall, over 3,500 students signed up for

the service—a third of the student body.

Marriage Pact is meant to be “your most optimal marriage backup plan,” says Manasi Gajjalapurna (E ’27), the launch project manager for this year’s Penn Marriage Pact. The platform—which boasts a presence at 109 schools and has garnered almost 630,000 signups nationwide—claims to pair college students with their “optimal match” through a modified version of the Nobel Prize–winning Gale–Shapley algorithm. Students fill out a lengthy questionnaire and, several days later, are given a name, email, and percentile number for their match, which seldom drops below 99.9—evidence that the algorithm has found that one–in–a–million (or at least a thousand) person for you. From there, you are free to reach out to your match and get to know them. “Do you really want to look up from your cubicle when you’re forty to find yourself alone?” the Marriage Pact website asks. “There’s no time to lose.”

The pitch for matchmaking services over traditional dating apps has serious merit, and college campuses seem to be the perfect grounds to test this new model out. According to Pinar Yildirim, associate professor of Marketing and Economics at the Wharton School, college campuses are “a good candidate” for matchmaking and dating platforms. “Dating is a much more youth–oriented activity,” she

explains. And on dense, interconnected campuses like Penn, “You can get together fairly quickly” with your match.

These matchmakers offer less matches than would be possible on traditional dating apps like Hinge or Tinder—but that’s precisely what users want. When dating apps were still novel, and especially after COVID–19 froze in–person modes of connection, many were willing to forego the more intimate pre–screenings of traditional dating for convenience and novelty. It is undeniably fun to treat people like doomscrollable content—swiping left or right, choosing yes or no ad infinitum.

However, while dating apps can increase the size and diversity of our dating pools, they also make it wildly difficult to find and commit to a single individual. When a user has ten matches, and each of those matches have ten matches, it is almost impossible to give each match— or any match—enough attention to create a real connection. As Yildirim explains, users eventually develop a sense of “exhaustion” on traditional dating platforms, with younger people in particular leaving the apps in droves. “The Match Group, they need to come up with their next big thing,” Yildirim says, referring to the stagnating revenues of the dating app juggernaut behind Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge. By contrast, college matchmaking platforms only give users one match at a time over

daily, weekly, or even yearly timescales. This restriction of choice forces users to focus on one person with whom they are supposedly compatible, foreclosing what would otherwise be an “exponential number of explorations,” says Yildirim.

Investors seem to be taking this paradigm shift seriously. In 2022, Bain Capital Ventures tied the knot with Marriage Pact, leading the matchmaker’s $5 million seed round. The cash has helped Marriage Pact’s parent company, Matchbox, expand its operations beyond college campuses. Matchbox uses the same questionnaire and matching algorithm format of Marriage Pact to power events in major cities across America, pairing guests with one another following an extended mingling period. The website explains that, with Matchbox, you can match at events ranging from your next “cocktail hour, séance, book club, networking sesh,” or “sunday soirée.” This model could represent the final goal of matchmaking platforms—adoption by paying, post–graduate users that offer a larger market and a path towards monetization.

Students, however, might not be ready for a paradigm shift in online love. Devon Yau (C ’28), who participated in both Marriage Pact and Date Drop, did not reach out to any of the people he was matched with. To begin with, his choice to use the platforms stemmed from

their campus virality, reflecting the way that school–specific matchmaking platforms can fuel a kind of campus buzz that traditional dating apps do not.

Devon explains, however, that these matchmakers only support an artificial and fast–paced form of dating. Students who match do so not because they choose the other person out of their own volition, but because an algorithm made that choice for them. In this model, the stakes are low—even lower than on traditional dating apps characterized by gamified swiping.

In fact, while matchmakers market themselves as an answer to Gen Z’s desire for greater authenticity, the pressure to commit to matches on such platforms might be even lower than on a traditional dating app. Matchmaking platforms “have the appeal that you don’t have to commit to them,” Devon explains. “With Hinge and Tinder, it feels like you have to own up to it more, because you’re putting all your information into it. There’s an expectation that you’ll reach out or connect. But with these sites, there isn’t even a face associated with the name.” Of the students that choose to use these matchmaking platforms, many seem to approach the experience with low expectations and no intention of genuinely finding love.

Manasi also describes the experience of participating in Marriage Pact as “lighthearted.”

Most people aren’t actually banking on Marriage Pact to save them from a life of loneliness. “It’s not meant to be like, ‘Oh, you should go date that person now,’” Manasi says. Instead, she views it as a bonding opportunity. In previous years, Manasi and her friends would fill out the questionnaire together, and discuss where they agreed or disagreed. “You get to feel a little bit closer to other people on campus through it,” she says. Indeed, with its casual framing and once–per–year schedule, Marriage Pact seems impractical as a serious option to find dates. Still, matchmaking platforms are betting that a stagnation of the dating app market, combined with a burgeoning

“Across the board, these companies place a certain amount of faith in today’s technology to arrive at real insight about people, using those findings to pair them up with compatible partners.”

will turn students on to their model. In recent years, a motley crew of companies have seized on the college matchmaking space, their services spanning the technological range. Several of these come from Penn, including Pairfect, a more analog option which relies on a team of human matchmakers and began with a pilot program exclusive to Penn graduate students. Veil was another zany and short–lived platform that asked users to complete a personality profile and rate AI–generated faces based on their attractiveness.

Across the board, these companies place a certain amount of faith in today’s technology to arrive at real insights about people, using those findings to pair them up with compatible partners. After all, we have AIs for everything these days—why not a robot that can find you love?

Drop, alleging that its founder, recent Stanford graduate Henry Weng, had stolen Marriage Pact’s intellectual property. McGregor did not respond to requests for comment.

“After all, we have an AI for everything these days—why not a robot that can find you love?”

A third Penn dating startup, Quickmeets, claims to understand users’ ideal type by analyzing an image of their celebrity crush with AI. Louis Chung, founder of Quickmeets, says that his team’s mission is to “solve the loneliness epidemic among Gen Z.” Chung believes that AI can provide a powerful solution that encourages human connection, providing both the convenience we are accustomed to and the compatibility we

To Chung, Quickmeets’ AI software is “a means to hyperpersonalize your matches.” After a user uploads a single picture, Chung claims that Quickmeets’ AI can understand not just their physical type, but personal features like their extrovertedness or their sense of adventure. Upload a photo of your celebrity crush at a rave, for example, and you might get paired with an outgoing, party–animal type. Choose that same person reading a novel by the fireplace, and you might get a more wholesome, bookish personality.

At the very least, this new industry seems hot enough to fight over. Beginning this past fall, Date Drop launched in colleges across the nation. Like Marriage Pact, the platform originated at Stanford—and if you ask Marriage Pact founder Liam McGregor, that’s not the only thing the two matchmakers have in common.

This past November, McGregor filed a cease and desist order against Date

Date Drop operates on a near–identical model to Marriage Pact, asking users to fill out a deep, values–based questionnaire before feeding it through an algorithm to find the person’s ideal match. But unlike Marriage Pact, the platform delivers matches weekly, with users opting in or out before the deadline for that “drop”. In one of Date Drop’s introductory emails to the Penn student body, the subject line reads “like marriage pact but weekly.”

In the list of exhibits they put together, Marriage Pact notes that Weng opened his emails from the platform several times and that several of the marketing materials and several questionnaire elements were similar. Undeterred by the threat of legal action, Date Drop returned this semester to continue offering weekly pairings.

“Everyone in the college matchmaking space is aware of everyone else,” says Weng. “But I’d say Marriage Pact serves a different need [than Date Drop]: It’s a campus tradition, something fun you do once a year. We’re trying to build a more consistent way for people to meet others.”

Regardless of which matchmaking company has the best strategy, it’s clear they’re all abuzz about the budding market of campus romance. Their founders see in college matchmaking an opportunity to supplant traditional dating apps, and are betting that their way is best—whether that means changing the frequency of matches or using AI to find the most compatible pairs. Still, despite the rapid emergence of matchmaking sites within Penn’s dating scene, many students are skeptical of whether these platforms will provide the kinds of connections they promise, if any at all.

Devon believes that the high usage of matchmaking sites at Penn is an indicator of the “impersonal” culture that shapes many students’ approach to relationships. He specifically cites Penn Face—the masks of effortlessness and success that Penn students often curate for themselves—as a driver of this.

Penn Face makes the introduction of matchmaking sites to Penn double–edged. Although these platforms promise students more opportunities to forge human connection, their success also reflects a social trend towards detachment and feigned nonchalance. In a culture where many young people fear vulnerability, faceless matchmaking platforms offer high rewards at low stakes, allowing users to skirt around

the openness that is often a prerequisite for pursuing romantic connection.

To Devon, matchmaking platforms are a vehicle for “trying to optimize the process of self selection that happens naturally” when dating. As technology, particularly the rise of AI, demands that we constantly make our lives more “efficient,” one has to wonder whether romantic relationships, so often marked by rawness and messiness, can be optimized as well. This question is made more pressing within Penn’s social scene, where ultra–competency is rewarded and vulnerability is largely shunned.

Given the plethora of research studies detailing Gen Z’s declining ability to connect, it’s uncertain whether matchmaking sites will truly satisfy college students’ cravings for romance, or if they will only exacerbate the loneliness epidemic they hope to fix. The venture capital firms and participants that have already invested in these sites show that matchmaking platforms are likely poised to continue integrating themselves into the Gen Z dating scene. But to students who are already tired of online dating, joining Marriage Pact, Date Drop, or Quickmeets is like trying to put out a fire by switching out the kindling. These platforms, on which you meet the technology first and the

“In a culture where many young people fear vulnerability, faceless matchmaking platforms offer high rewards at low stakes, allowing users to skirt around the openness that is often a prerequisite for pursuing romantic connection.”

people second, hardly guarantee a love match—or even a good first date.

It’s more likely that our level of success in love will continue to depend on our own inclination to search for it. With the always–online, never–connected state of our generation and the average Penn student’s mortal fear of embarrassment, finding love at Penn seems bound to be a difficult process. For his part, Devon had a tough time figuring out how he could actually connect with the faceless names that these platforms fed him. “What are you supposed to do with a Date Drop?” he asks. “Go on a coffee chat?” S

By Laura Gao

Design by Alex Nagler

Penn students climb it, protest at it, and confess on it. But the LOVE statue was always asking what it means to love in a commodified world.

When the LOVE statue was unveiled on College Green in summer 1999, the student body hated it. “It’s a copy of what’s downtown, and I think it’s disgusting,” Josh Croll (C ’00) told The Daily Pennsylvanian at the time. Jon Sell (C ’01) echoed the frustration: “I think they should set it on fire and put it on top of the high rises.” Pop art had always had its share of dissidents, with many art critics (or non–art critics, like Josh and Jon) finding it a crass, tasteless, bottom–of–the–barrel, watered–down version of fine arts. “I can imagine they might’ve been thinking, it’s embarrassing taste in some ways,” says History of Art professor Michael Leja. “It’s like, the campus is too classy to have a tacky sculpture like that on it.”

But times have changed. Today, whether it’s a place of protest when Russia invaded Ukraine, or a go–to climbing spot for Hey Day photos, the statue has evolved into a central, and dare I say, beloved, part of campus life. “One of my favorite things is seeing the line of people who are there waiting to have their pictures taken during commencement,” says Lynn Smith Dolby, director of the Penn Art Collection. “And not just with their friends, but when their families come to celebrate with them. I think it just becomes part of what they remember about being at Penn, and that is so special for me.”

Despite the image’s popular use as a commodified, corporate symbol of love, Penn

students have reimagined it into a place of genuine connection and political action. “It's just wild to see how much that has changed over 25 years,” Lynn says.

The LOVE statue has seen many creative uses from Penn students throughout the years. In fall 2023, the Signal Society launched a campaign titled Confessions on Locust. Penn students handwrote anonymous, at times deeply personal reflections about their time at Penn and taped them to the front surface of the statue on sticky notes. For a few weeks, walking down Locust Walk meant seeing neon squares in highlighter colors dotting the familiar red of the four letters. Confessions detailed the ups and downs of Penn life, including struggles with queer identity, course selections that parents didn’t approve of, and even a student’s release of a rap song.

When ten people died in a 2022 fire in Ürümqi, China, over 100 Penn students gathered around the LOVE statue, bringing candlelights, flowers, and hand–painted protest signs in Chinese. After the start of the war in Gaza, Penn community members held a vigil at the statue to commemorate the Palestinian lives lost in the armed conflict.