SecondWave:

The Beginning of a Post-War Era

SecondWave artists Charles Stewart (second from left) and Ted Egri (third from left) in an early 1950s parade, carrying the broken wagon wheel that symbolizes and honors the first generation of artists that came before them in Taos, New Mexico.

SecondWave:

The Beginning of a Post-War Era

Opening Reception: Saturday, 13 September | 5 - 7 PM

Exhibition Dates: 13 September - 2 November, 2025

Image on opposite page courtesy of the Harwood Museum of Art

INTRODUCTION

203 Fine Art is pleased to present SecondWave:TheBeginningofaPost-WarEra , an exhibition exploring the enduring impact artists supported by the GI Bill had on the evolving artistic scene of Taos, New Mexico, in the years following World War II.

In the wake of the war, a wave of European modernist influence—shaped by artists such as Miró, Kandinsky, Albers, Mondrian, and Hofmann —merged distinctly with American energy and ambition. Veterans embraced the experimental ethos of the time, developing stylistic lineages that ranged from figuration and landscape to Cubism, Transcendentalism, Surrealism, Lyrical Abstraction, Hard-edge painting, and Abstract Expressionism.

The Second Wave artists not only advanced Modernism but also infused it with a distinctive spirit--reflective, radical, and deeply connected to place. Without The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 that provided these artists with national and international education and access to legendary teachers, such as Richard Diebenkorn, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, we may have lost this entire movement of art history altogether.

Artwork on opposite page:

Detail of Richard Diebenkorn (1922 - 1993), Untitled(Albuquerque), 1951

Earl Stroh (1924 - 2005)

Untitled, Ranchitos Road, Taos NM, c. 1950s, 20 x 24”, oil on masonite

Andrew Dasburg (1887 - 1979)

Adobes-TalpaRidge, 1966, 18 x 24”,pastel on paper

ART SCHOOLS OF THE VALLEY

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—better known as the GI Bill—provided returning veterans with unprecedented access to higher education, professional training, and resources for reintegration into civilian life. For artists, it opened doors to study at prestigious institutions across the country and abroad. Art schools flourished in the region during this period, including the Mandelman-Ribak Taos Valley Arts School the Bisttram School of Fine Art, and the University of New Mexico’s Summer Field School of Art.

Taos, already celebrated for its luminosity and dramatic landscapes, became a magnet for these post-war innovators. Drawn west by the allure of the unknown, the solitude conducive to work, and the conversations within a tight-knit creative community, here, the “Taos Moderns” rejected Regionalism, Social Realism, and commercial, illustrative tropes in favor of bold abstraction and a reimagined landscape genre.

Pictured on opposite page:

Louis Ribak (standing at center), Beatrice Mandelman (seated, wearing striped shirt) and Taos Valley Art School class in front of Ribak studio. Ca. 1952. Photographer: Regina Cooke. Courtesy of the Harwood Museum of Art.

Louis Ribak (1902 - 1979)

Canyon, c. 1950s, 48 x 60”, oil on masonite

Beatrice Mandelman (1912 - 1998)

Still Life with Fruit, 1943, 22 x 17”, oil on canvas

ExactChange#26, 1977, 34 7/8 x 34”, oil on linen

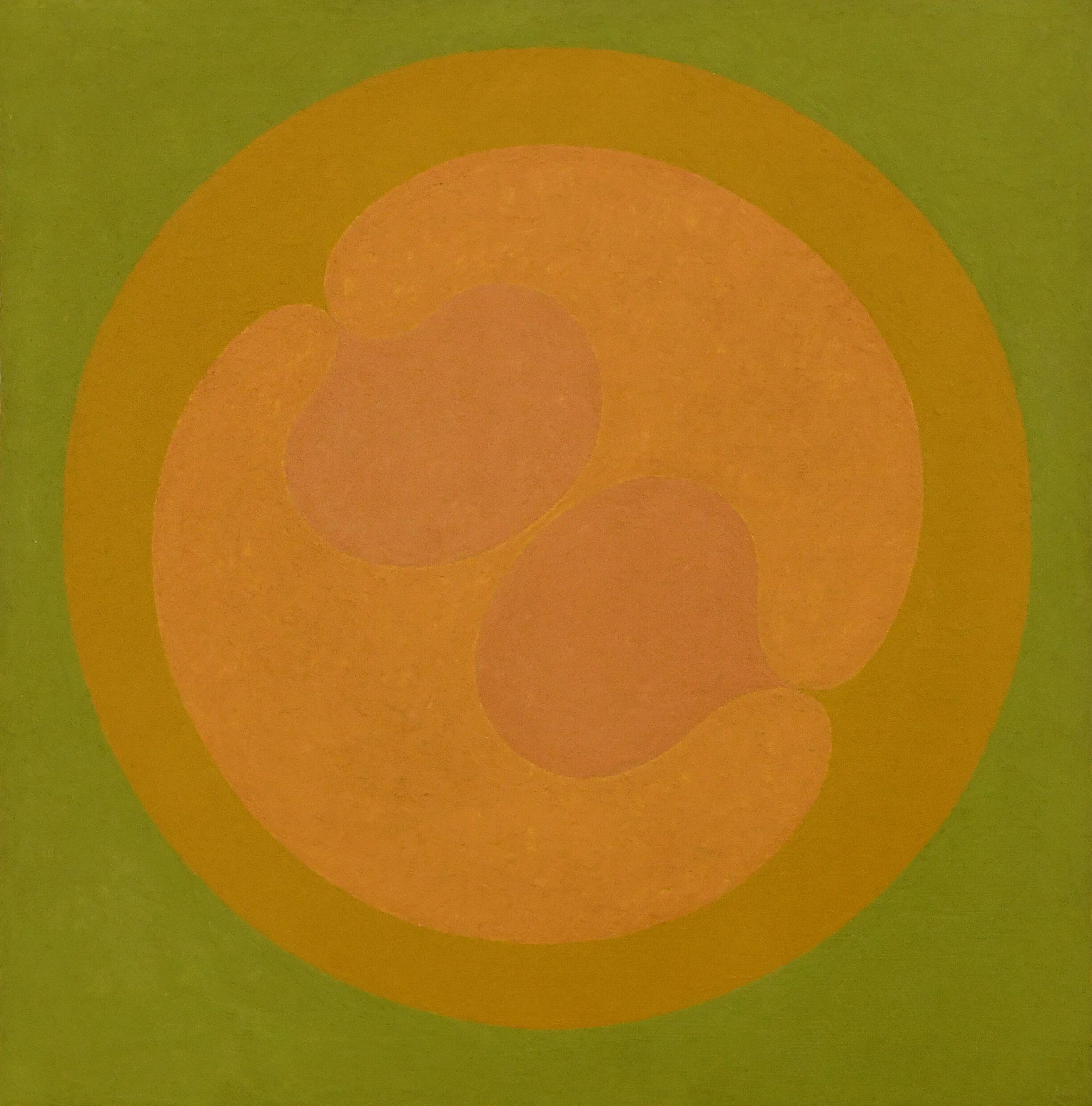

Frederick Hammersley (1919 - 2009)

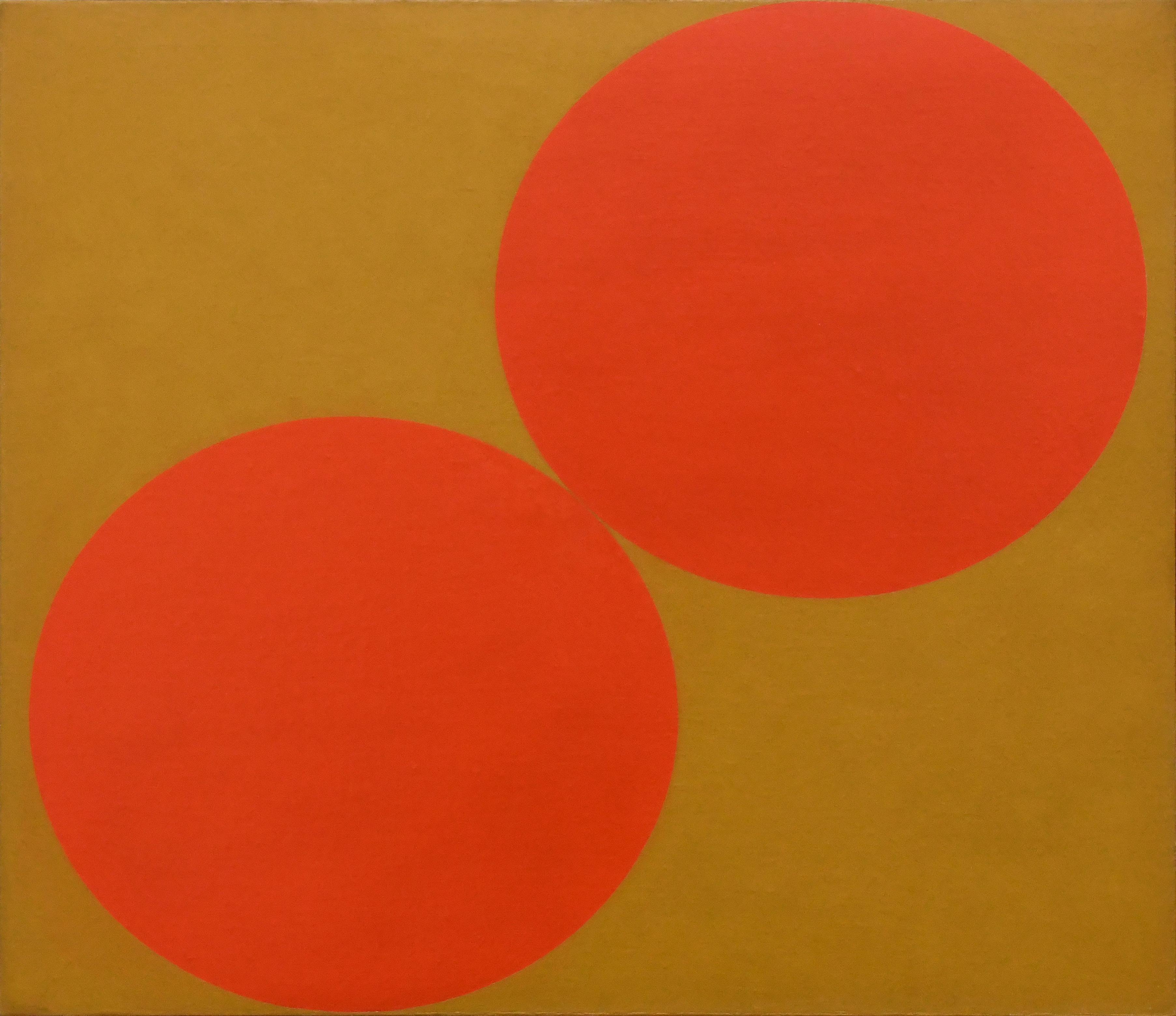

Oli Sihvonen (1921 - 1991)

Duo, Red & Ochre,1962, 34 1/2 x 40”, oil on canvas

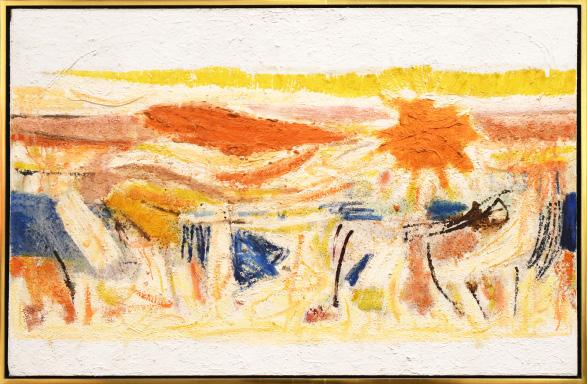

Lawrence Calcagno (1913 - 1993)

Untitled, 1956, 37 1/4 x 57”, oil on canvas

For many, New Mexico signaled a retreat from the urban—an escape from the shadows of fascism and war toward something more enlightened and spiritualized. Taos itself became a haven. In an era of expanding galleries, art schools, and prosperity, artists sought renewal and inspiration from diverse sources, both academic and cultural. The post-war art boom radiated from coast to coast and beyond, bringing in artists from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; Black Mountain College, North Carolina; California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco, and more. Here, they would begin a new art movement that would lead to New Mexico becoming one of the largest art centers in the United States.

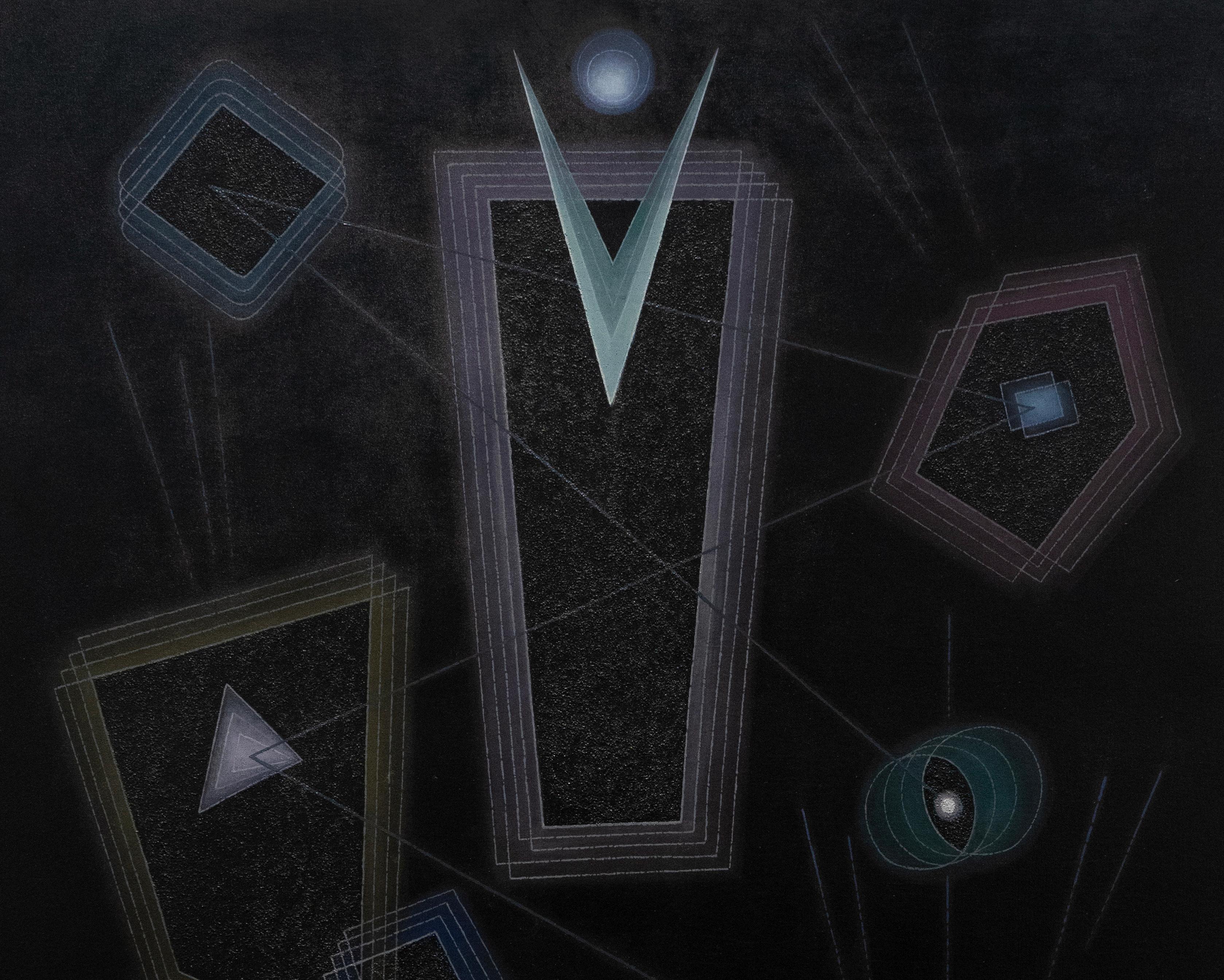

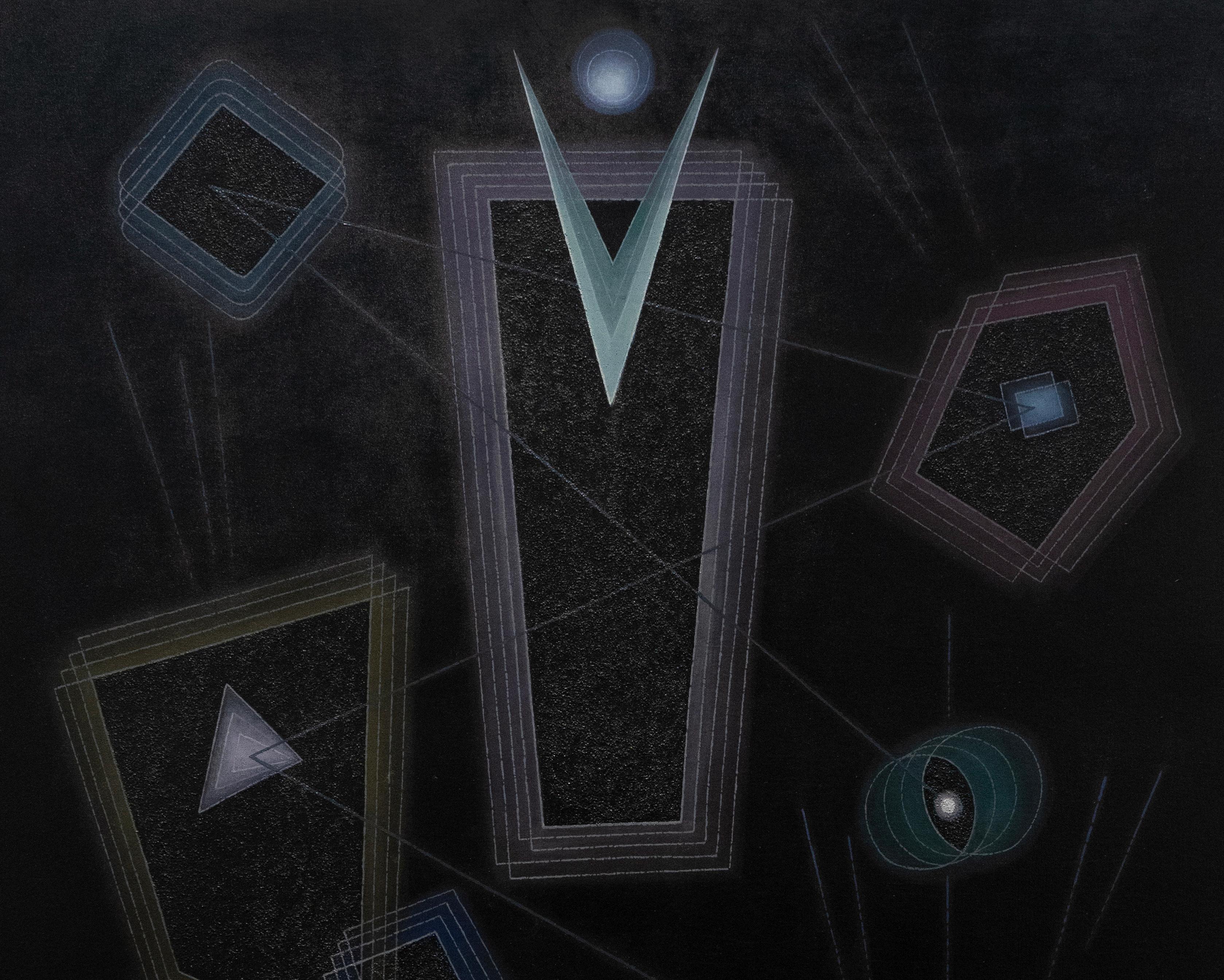

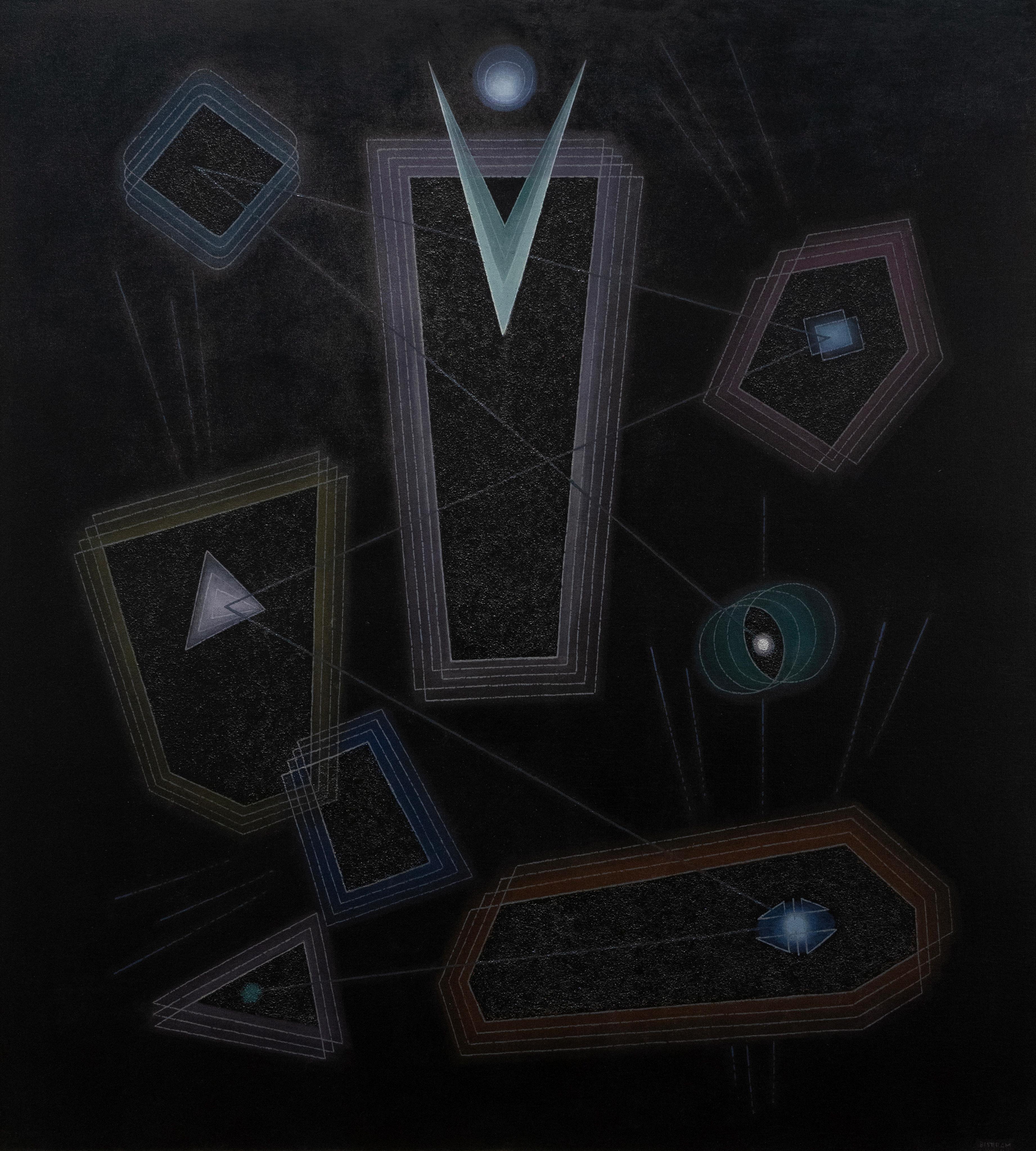

Emil Bisttram (1895 - 1976)

StudyforSailsintheNight, c. 1965, 11 7/8 x 13 1/4”, gouache on board

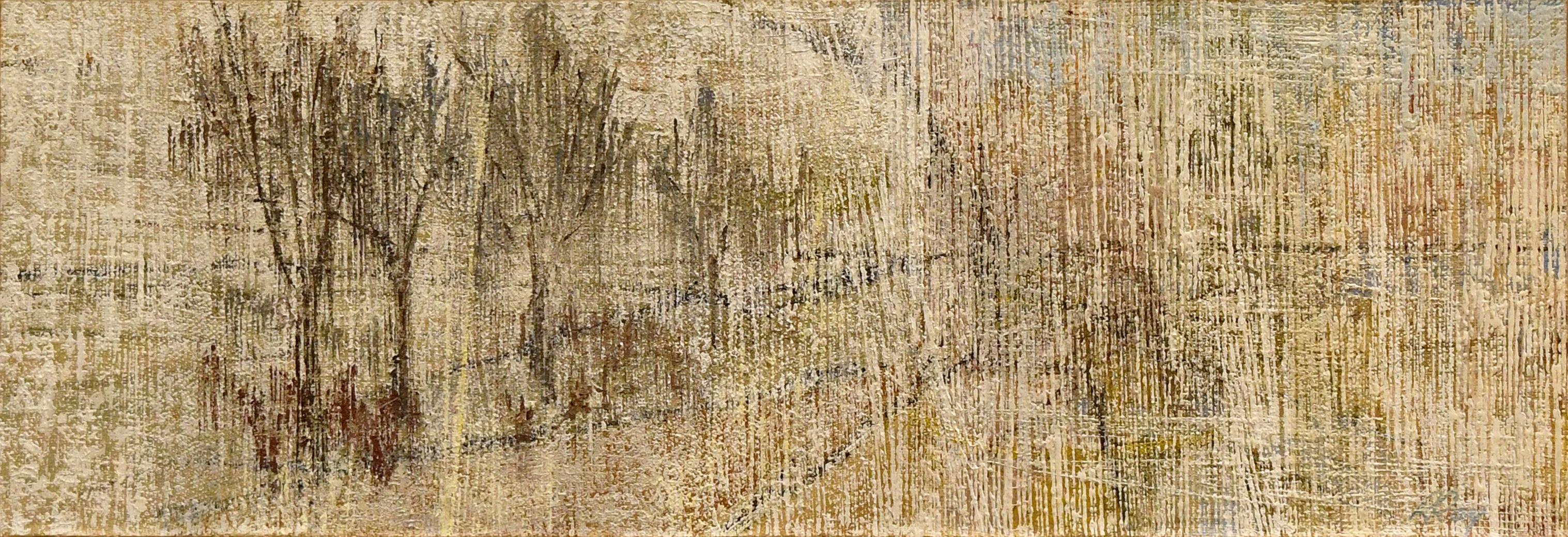

Robert Ray (2024 - 2002)

Untitled Winter Orchard, c. 1958, 7 x 20”, oil on canvas mounted on board

The exhibition includes works by artists not previously exhibited at 203 Fine Art, including legendary individualists Richard Diebenkorn and Norman Bluhm.

Diebenkorn, a U.S. Marine, was one of the first veterans to enroll at the California School of Fine Arts in 1946. He was quickly hired the following year to teach his fellow veterans Lilly Fenichel and Lawrence Calcagno, while he worked alongside Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Edward Corbett, and Clay Spohn. In 1950, he enrolled in the graduate fine arts department at the University of New Mexico. Away from both coasts, Diebenkorn embraced both figuration and abstraction, and during the early 1950s, his work reflected the light, sands, and winds of New Mexico.

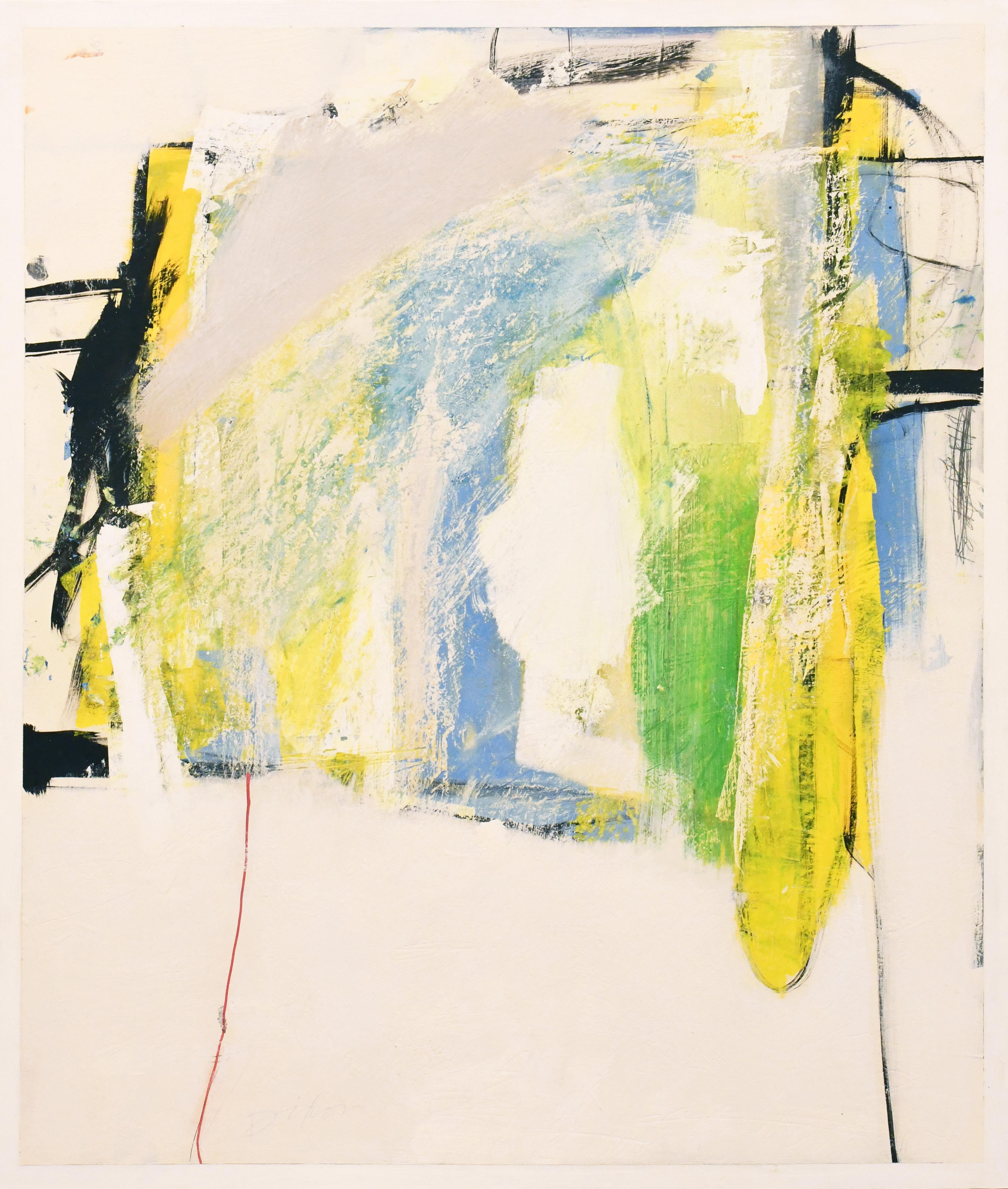

A newly acquired 1960 painting by Norman Bluhm is also a work of note. Bluhm, who studied with Calcagno in Paris and later exhibited with him at the illustrious Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, resisted the formalist orthodoxies that shaped the New York art scene for decades, a mindset common amongst the artists who came to work in New Mexico. Bluhm’s heterodox sensibility—evident in his embrace of sources outside the canonical framework of Abstract Expressionism—distinguished his practice from that of his contemporaries. Bluhm’s experience as a bomber pilot in World War II, during which he flew more than fifty missions, offered him a singular perspective on vast skyscapes: the atmospheric vistas of his wartime flights, inflected by his engagement with the celestial drama of the Renaissance and Baroque paintings.

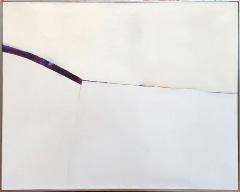

Artwork on opposite page:

Detail of Norman Bluhm (1921 - 1999), Untitled, 1960

Richard Diebenkorn (1922 - 1993)

Untitled(Albuquerque), 1951, 11 x 14”, watercolor on paper

Clay Spohn (1898 - 1977)

Ballet of the Elements, 1952, 19 3/4 x 27 3/4”, oil on masonite

Emil Bisttram (1895 - 1976)

SpaceAbstraction, 1951, 88 1/4 x 78 1/4”, oil on canvas

Louis Catusco (1927 - 1995)

DaphaneCalled, 1973, 24 x 24”, acrylic on board

WashingtonD.C.,March,1965, 1965, 40 x 50”, oil on canvas

Edward Corbett (1919 - 1971)

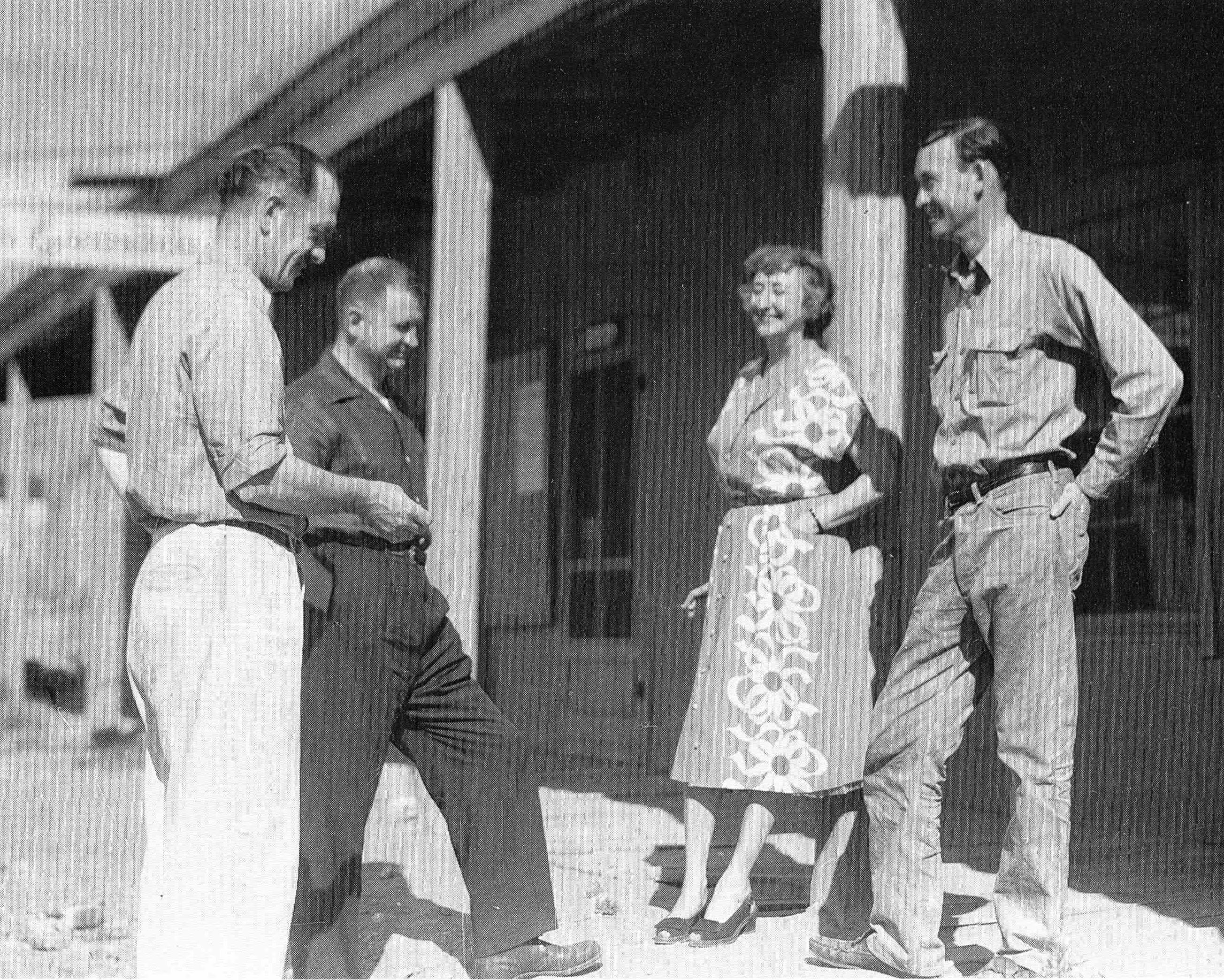

Pictured opposite page: Edward Corbett (far right) standing with La Galeria Escondida owner Eulalia Emetaz

Lawrence Calcagno (1913 - 1993)

Red Season II, 1962, 30 x 25”, oil on canvas

Lilly Fenichel (1927 - 2016)

Untitled, c. 1990s, 36 1/2 x 36 1/2”, oil & wax on waferboard

Janet Lippincott fled the Nazis with her family in 1939, and an early immersion in Freudian psychology left a lasting imprint on her artistic outlook. An artistic prodigy, she enrolled at the Art Students League in New York at the age of thirteen. During World War II she enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps and worked in General Dwight Eisenhower’s European office with the press corps. Lippincott delighted in recalling how she once told General George Patton to sit down and be quiet after he burst into Eisenhower’s office demanding attention.

During a German blitzkrieg of London, she broke her back when a building collapsed. Back in the States, she recovered and boldly embarked on her next adventure. Using the GI Bill, she traveled to Taos to study under Emil Bisttram.

Lippincott first attended secretarial school on the GI Bill, before using it in 1949 to study with the Taos School of Art with Bisttram. She then went on to attend the California School of Fine Arts and became associated with the Los Angeles ‘Cool School. ’ In this context, she moved in the orbit of the so-called ‘BoysClub,’ which included Ed Moses, Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell, and Billy Al Bengston. Later, Lippincott established herself as an important figure in the artistic communities of both Taos and Albuquerque, helping to expand the reach of modernism in the Southwest.

Janet Lippincott (1918 - 2007)

HomagetoRembrandt, 1961, 38 x 58”, oil on canvas

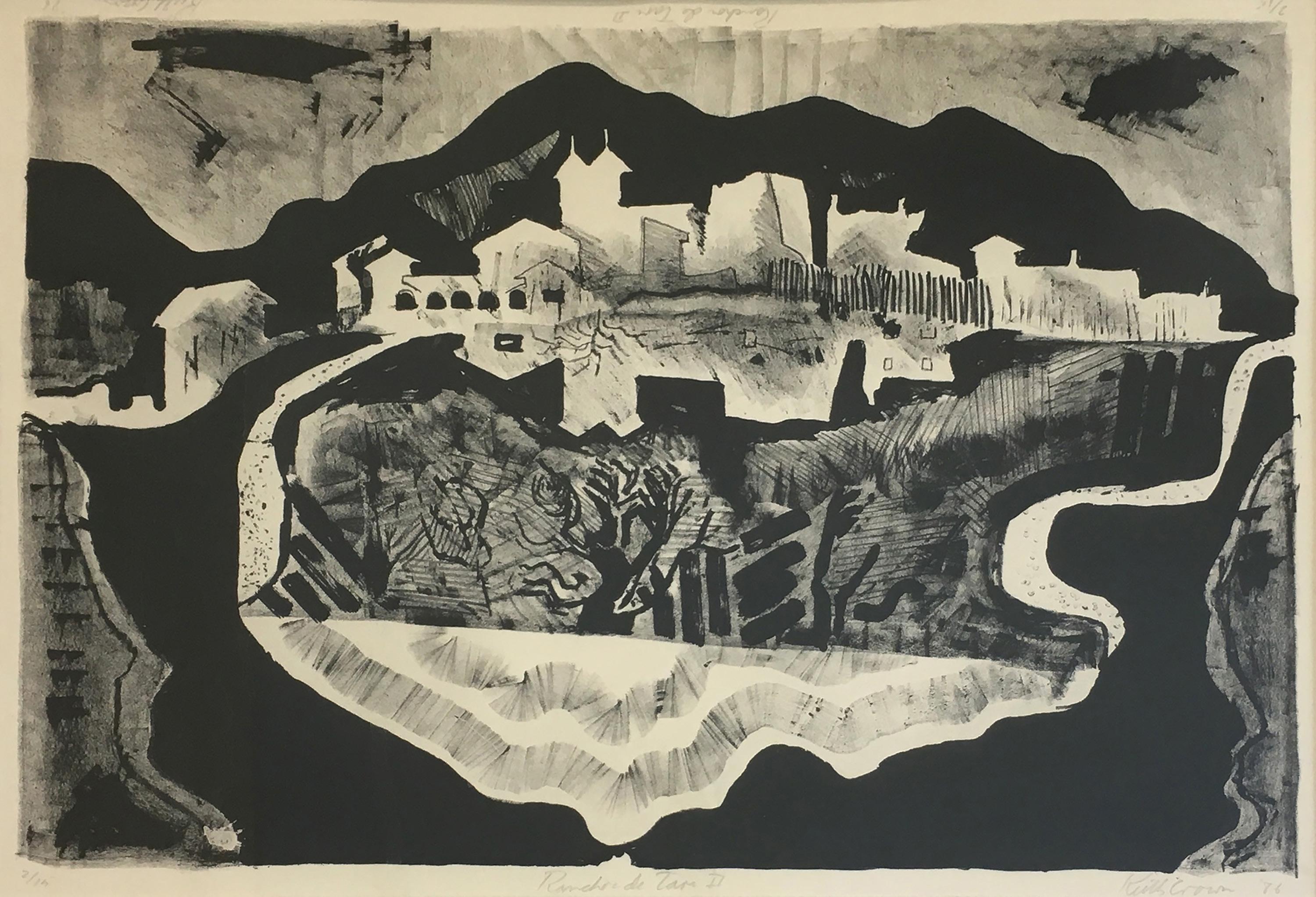

Keith Crown (1918 - 2010)

Ranchos de Taos II, 1986, 13 3/4 x 19 1/2”, lithograph on paper

Ely (1923 - 2004)

Wolcott

CagnesSurMer, 1953, 10 x 12 1/2”, tempera on paper

Robert C. Ellis (1923 - 1979)

We Find Solace, 1957, 21 1/2 x 14”, casein on paper

Oli Sihvonen (1921 - 1991)

Gemini,1956, 23 1/2 x 23 1/2”, oil on masonite

John de Puy (1927 - 2023)

Soul Catcher, 1956, 24 x 30”, oil on canvas

Abstract

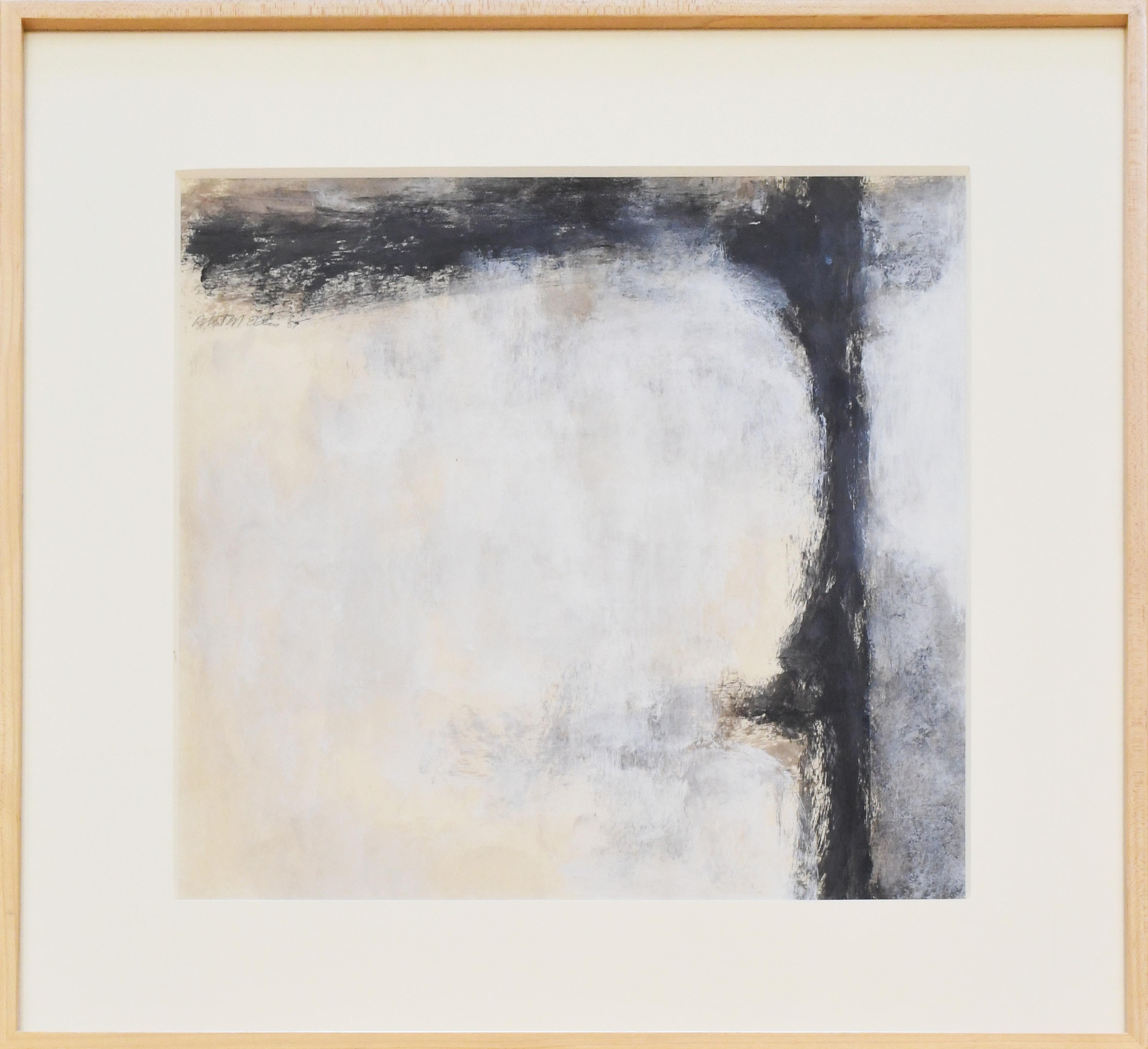

Charles Stewart (1922 - 2011)

Untitled

Portrait, 9 3/4 x 8”, oil on canvas mounted on board

Robert M. Ellis (1922 - 2014)

Bridging#1, 1957, 17 x 17”, vinyl crystals with pigment

Robert Ray (1924 - 2002)

Untitled,CliffDwellings, 1957, 38 x 36”, oil on canvas

Beatrice Mandelman (1912 - 1998)

Rift #7, 1986, 24 x 20”, acrylic on canvas

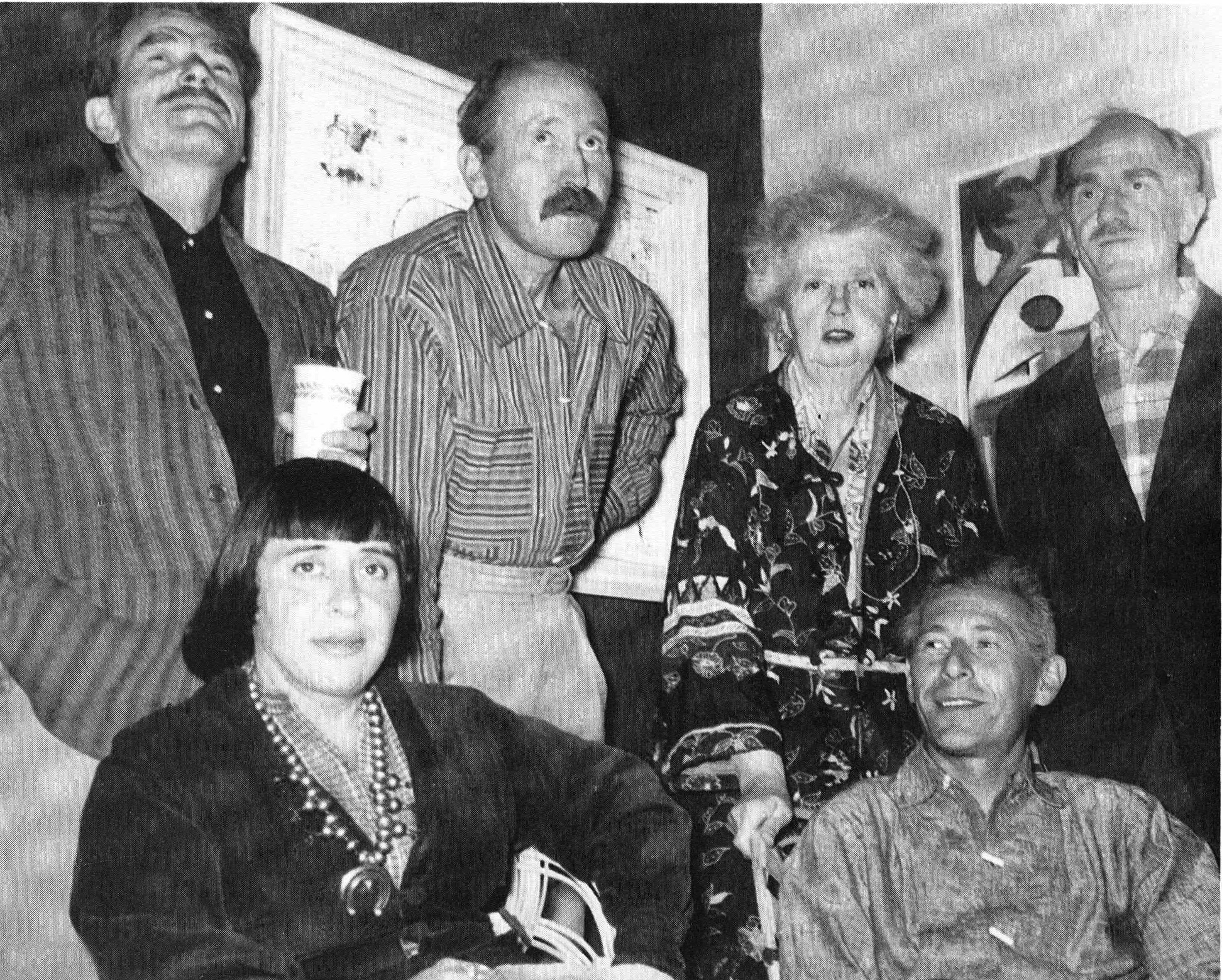

Image on opposite page left to right: Louis Ribak, Beatrice Mandelman, Alfred Rogoway, Dorothy Brett, Ted Egri, and Clay Spohn.

Photographer: Regina Cooke

Tom Dixon (b. 1946)

red line, 2025, 42 x 36”, oil & acrylic on masonite

Keith Crown (1918 - 2010)

RanchosdeTaosinSangredeCristoMtns, 1986, 22 1/4 x 20 3/4”, watercolor on paper

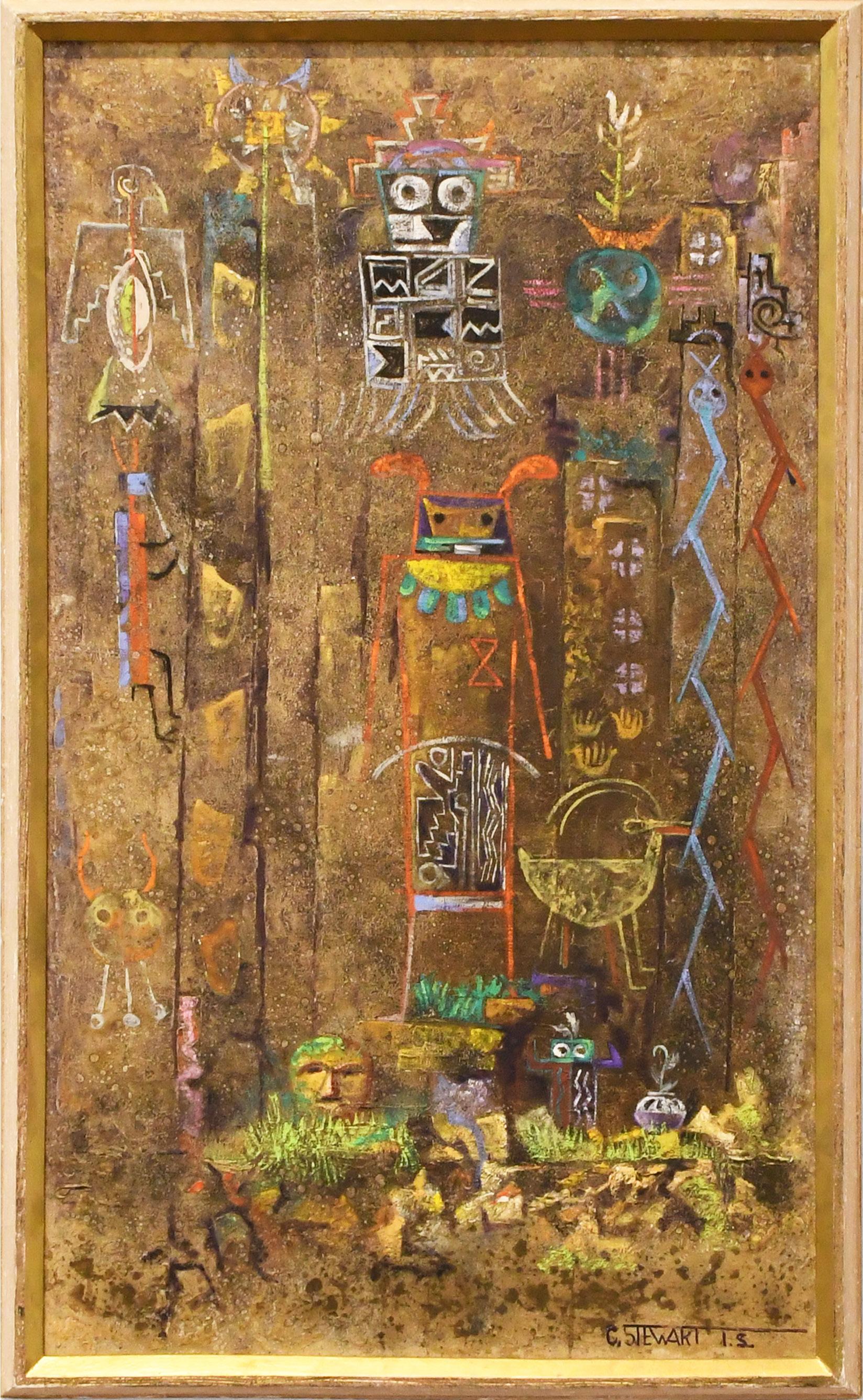

Stewart (1922 - 2011)

AttheSpringofToloac, 1995, 40 x 24”, oil on canvas

Charles

Leo Garel (1917 - 1999)

TaosatNight, 1948, 30 x 36”, oil on board

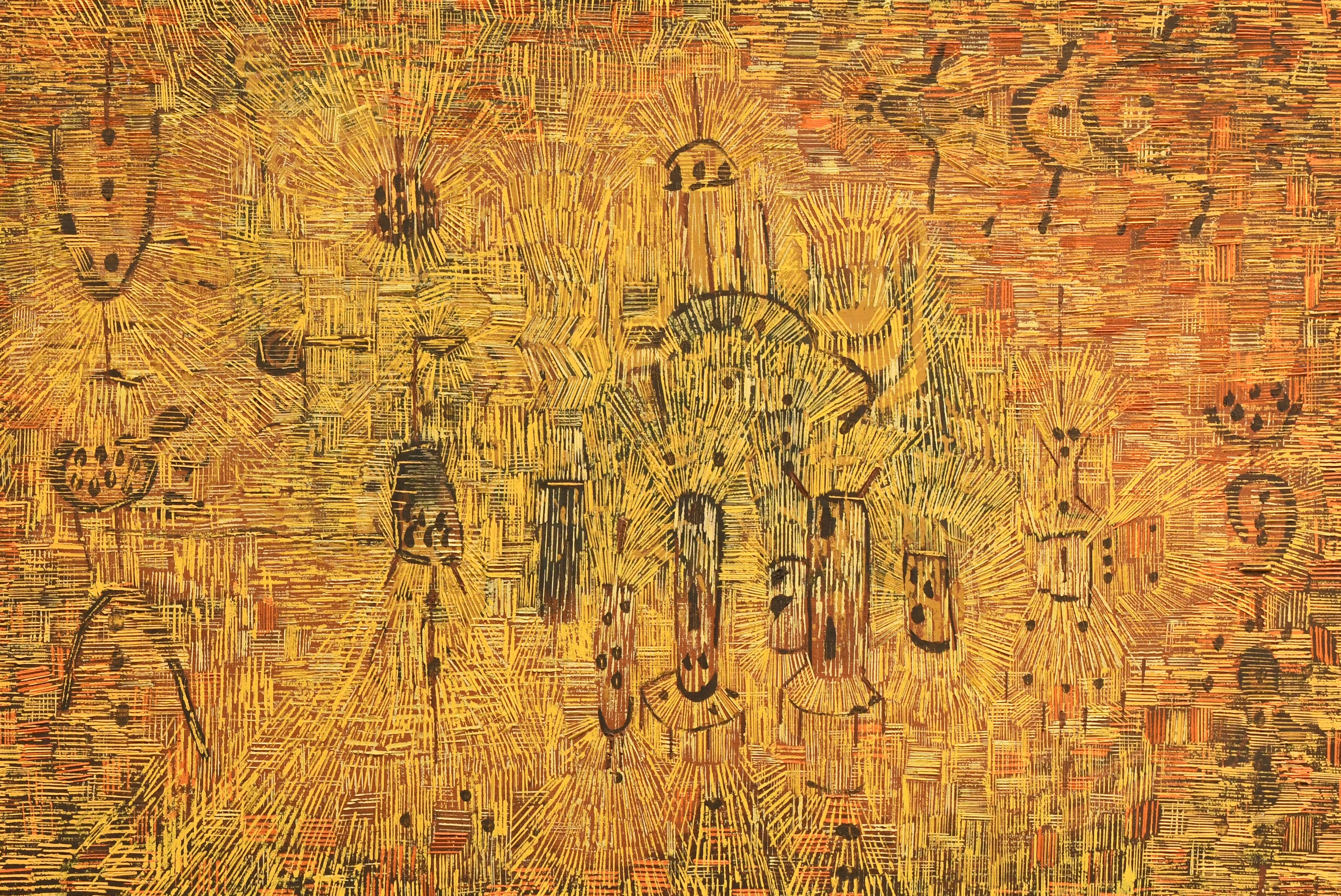

Lee Mullican (1919 - 1998)

UniversalBarque(LM.431) , 1969, 35 x 75”, oil on canvas

Ted Egri (1913 - 2010)

Intertwined , c. 1950s, 23 x 12 1/2 x 6”, metal and plaster with patina

Lee Mullican (1919 - 1998)

PremiereMirage(LM540) , 1949, 20 x 30”, oil on canvas

Earl Stroh (1924 - 2005)

Requiem, c. 1954, 21 1/2 x 18”, oil on canvas

M Ellis (1922 - 2014)

PostAegeanSeriesNo.34, 2009, 24 1/4 x 32 1/4”, oil on canvas

Robert

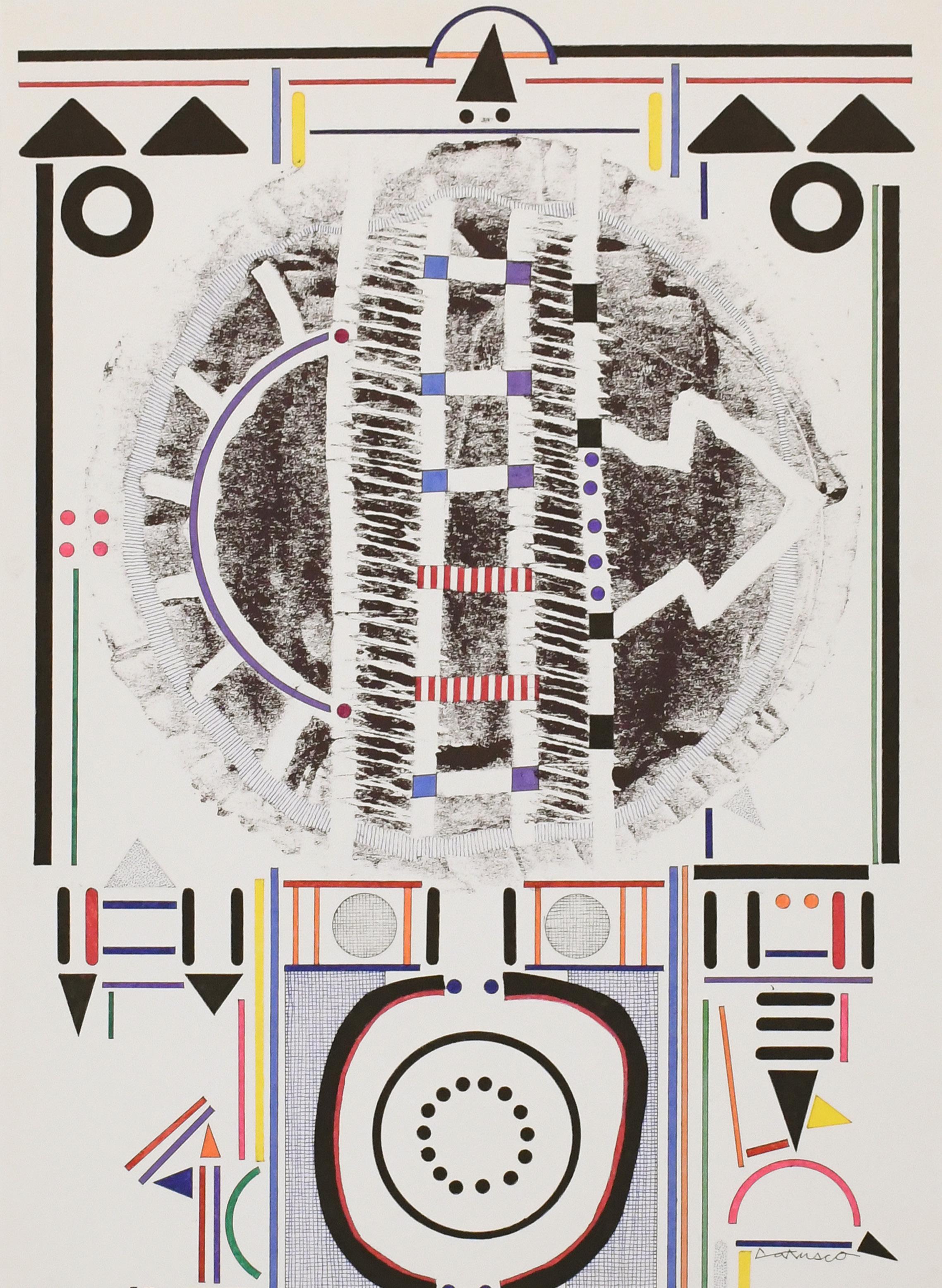

Louis Catusco (1927 - 1995)

Untitled 5, c. 1980s, 22 x 15”, ink on paper

Peter Chinni (1928 - 2019)

Birth, 1988, 15 x 14 1/2 x 6”, bronze with black patina

Leo Garel (1917 - 1999)

UntitledMaine2(OuterIslandMaine) , 1948, 20 x 24”, gouache on paper

Ely (1923 - 2004)

ForAdeine(UntitledFiesta), c. 1960s, 17 x 23 1/4”, acrylic on paper

Wolcott

Cliff Harmon (1923 - 2018)

Earth Forms No. 77, ca. 1970s, 40 x 58”, acrylic on canvas

CONCLUSION

The lore and legacies of the “first wave” artists and patrons in New Mexico—Ernest Blumenschein, Mabel Dodge Luhan, D.H. Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Andrew Dasburg—are well documented. Their migration west and the formation of an artist colony in Taos have long shaped the region’s cultural mythology. Less examined, however, is the post-war “second wave” and its search for identity in the aftermath of World War II—a time marked by political, intellectual, philosophical, and artistic reckoning. In an era of existential crises and deep European modernist influence, post-war art in New Mexico resisted cohesion into a single style. Instead, it reflected a moment of extraordinary multiplicity.

Thanks to the G.I. Bill, a new generation of artists pursued advanced studies and found their way to New Mexico. The import of the educators is undeniable: Andrew Dasburg at UNM Summer Field School, was the state’s leading modernist teacher for more than six decades, by Emil Bisttram’s School of Fine Art, and by Beatrice Mandelman and Louis Ribak’s Taos Valley Art School. The Helene Wurlitzer Foundation further distinguished the region as a hub for creative development, its vision and generosity attracting artists eager for new directions and opportunities. This flourishing of artistic education, exchange, and experimentation added significantly to the new era, the rich cultural vitality of New Mexico, and especially of Taos.

As historian David L. Witt observed, “outside of New York and San Francisco in theearly1950s,therewasprobablymoreinterestingModernartgoingoninTaosthan anywhereelseinthecountry...”

Edward Corbett (1919 - 1971)

Provincetown,No.6 , 1960, 25 x 30”, oil on canvas