page

WINTER 2025-26

page

by Forrest White

harlie Peddycoart went to bed on the night of Oct 19, 2022, thinking ahead to work the next day. A retired US Army paratrooper and combat veteran, he’s a jack-of-all trades for the facilities department at First UMC, always quick to offer a kind word, an engaging smile and a helping hand.

He had spent some time with his only child, Charlie II, earlier that evening. They were planning a surprise marriage proposal for Charlie II’s girlfriend.

That same night, at the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute in Charlotte, N.C., Clemethy “Clem” Dixon watched “meaningless TV,” while hooked to monitors in need of a heart transplant. He’d been at Sanger for a couple of months, waiting and wondering.

ON PAGE 5 A Legacy of Giving Our Ministry Partner: One Blood and Bob Harter’s Lifetime of Giving Meet Our Beautiful Plant Ladies! IN THIS ISSUE page page

Rev. Charley Reeb Senior Pastor

Dear Church Family,

In a world often overshadowed by challenges and despair, the stories we share can give us hope and inspiration. This edition of First Connections will share such stories. You are about to be moved and inspired by courageous people who have made a profound impact on others. These stories of sacrifice resonate deeply, challenging us to reflect on our own lives and the legacies we wish to leave behind. In a society that often prioritizes personal gain, the pages ahead remind us that the greatest fulfillment comes from serving others. Join us as we celebrate these remarkable journeys which will motivate us to create a legacy that reflects the heart of Christ.

As we think about giving and serving as our legacy, I encourage you to turn in your estimate of giving for 2026. As we strive to move “Faithfully Forward” as a church, your generous support is vital in impacting countless lives for Christ and enabling us to serve our community more effectively. Thank you for your continued commitment to our shared mission of making disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world.

With Great Expectations,

Forrest White Director of Mission Ministries

On a September day in 2006, I sat beside Mary Elizabeth Brooks in her hospital room, my chair close to the left side of the bed. The blinds were pulled so she could rest. We were alone. We hadn't talked too much since I arrived to give her devoted parents a chance to grab lunch. She was tired and weak, her body ravaged by leukemia. There wasn't much of anything we needed to say. I knew she loved me. She knew I loved her.

oBut Mary Elizabeth broke the silence with a question.

"Do you think I'm going to die?"

She had asked me a couple times before and I refused to tell her the truth. This time, I looked at her and said what she already knew.

"Your body might die, but your spirit will live forever."

How empty those words must have seemed to a young woman, barely 24, faced with undeniable reality that her earthly life would be short, that all the dreams she dreamed weren't going to come true.

Six days later, shortly after daybreak, my phone rang. I didn't need to answer to know why the person on the other end was calling. Mary Elizabeth's body had died in the darkness of the overnight. That loving, kind, selfless spirit was free from all the pain.

As I look back now, I can surely say I told her the truth, alone in the hospital room that day.

Mary Elizabeth had given her life to Christ.

Her spirit is with God, but it is still here, with us, too.

Every time I led a mission team leader training or an early response team training – and I did more than five dozen – I told a bit about Mary Elizabeth's life and how she chose to live it.

Every time I share my testimony in a church – and there was a time when I did that often –I tell a bit about Mary Elizabeth's life and how she chose to live it.

And, every chance I get, I tell of how God spoke to me on Sept. 11, 2006.

I have no idea how many times God has spoken to me across my lifetime and I didn't hear.

That day, I heard.

The Brooks family spent every moment they could with Mary Elizabeth. When faced with telling a child and a sister farewell for now, things like taking care of your yard just don't matter.

So, I offered to cut their grass, perhaps the simplest act of service you can imagine. There is nothing profound about starting an engine and pushing a mower over the lawn. But in those moments, with all the world's noise and all of my racing thoughts lost in the sound of the engine, God spoke to my heart.

"Build a Habitat for Humanity House to honor Mary Elizabeth."

When God speaks, you don't keep it to yourself. I finished cutting the grass, went home to take a shower, and then returned to the hospital to share my experience with her parents, Herb and JoAnn. They thought it was a great idea.

In a private moment, late that night, they shared it with Mary Elizabeth. She thought it was a great idea, too.

Because Mary Elizabeth and her family touched so many lives, raising the $65,000 was easy. We went on to build a Habitat house in Richmond, Va. and sent money for a house to be built overseas.

In so many ways, Mary Elizabeth showed us how to live, but she also showed us how to face our last days with dignity and courage and grace. I remember standing in the corner of her hospital room one day as her mother sat on

the edge of her bed, weeping. I remember Mary Elizabeth reaching out with her left hand, touching her mother's hand, assuring her that everything was going to be OK.

I was a pallbearer at her funeral. I remember moving toward the open grave with her body inside the casket. I remember the overwhelming feeling of sadness, even though I knew only her body had died ...

Looking back to the first half of September 2006, it seems both long ago and, at times, still fresh.

Earlier this year, I caught a glimpse of a woman, likely in her forties. I looked at her again and thought, “That’s how Mary Elizabeth would look now.”

It seems sad as I type it.

But somehow it made me smile that day, perhaps because I remembered that long ago promise …

Yes, Mary Elizabeth's spirit is with God and has been for a while now, but it remains here with us, in our thoughts and in our stories, in passing glimpses of strangers and in a house we built because she lived, just as I promised her it would, all those years ago.

All the best,

Doctors caught Mary Elizabeth’s leukemia only five months before her death. She never reached a point of being well enough to be added to the registry for a potential lifesaving bone marrow transplant through what is known now as National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP).

Even though I am a huge chicken when it comes to needles, I joined the registry in 2011 during a drive we had at Mary Elizabeth’s home church. Only once did I surface as a potential match as a donor, but more testing eliminated me.

These days they look for donors ages 18-35. If you or someone you love

owould like to find out more about becoming an NMDP donor visit www. nmdp.org. They especially need Hispanic, African American and Asian donors.

While marrow, organ and blood donations save lives, Mary Elizabeth’s life story reminds us that we have a chance to change lives daily through our choices.

■ She was an elementary school teacher. You can change the life of a child by volunteering at Philip O’Brien Elementary, our partner school. Simply reach out to O’Brien passion team leaders Ann Skellenger (abraham409@aol.com) or Joleen

Golden (joleengolden@yahoo.com) for ways to help.

■ Both as a student and as an adult leader, Mary Elizabeth was a faithful participant in short-term missions. We’ll be sending multiple teams to help with disaster recovery in 2026 and one to serve in the Dominican Republic in May. Shoot me an email for more information (fwhite@firstumc.org)

■ If you’d like to help a qualified family build a house to make their home, Habitat for Humanity takes volunteers of all skill levels. I have been blessed to serve with multiple affiliates around Florida. Explore affiliates around the state at www.habitatflorida.org

“You lay in bed every day, wondering if it’s the day the Lord’s going to call you home,” Dixon said, recently. “The mental stress of it all far exceeds what happens to your body, just lying there needing a heart, knowing every day you don’t get one could be your last ...”

Meanwhile, Lacopbra “Coco” Holloway hadn’t even spent her first night at the University of Alabama Birmingham Hospital, having been admitted earlier that Wednesday. Her body was swelling, her eyes jaundiced.

“Everything was shutting down on me when I got to Birmingham,” said Holloway, who lives in rural Piedmont, Ala. “They said I was lucky to be alive.”

Doctors at once put her on the list for a liver transplant.

Before sunrise on the 20th, life would take a drastic turn for the three of them, complete strangers who would soon be bound by a young man’s gift.

Peddycoart was sound asleep when his phone rang about 4am.

Something was wrong with Charlie II.

But he knew what it all meant.

“I knew we were in trouble.”

Within two days, doctors told Peddycoart there was no hope for his son.

He opted to watch the tests to confirm his son was brain dead.

“I wanted to have no doubt.”

But he wasn’t prepared.

“ FOR ME TO LIVE, SOMEONE ELSE HAD TO DIE... SO I’LL BE HONEST, THERE WAS A LITTLE BIT OF GUILT THERE.”

“Clem” Dixon

“For the second time in my life, the second time in just a few days, I had to witness something I can’t unsee,” Peddycoart said, trying hard to hold back tears as the memory returns to his mind.

He stopped to gather himself.

“They poured cold water in his ear,” Peddycoart said, barely able to speak the words. “They thumped his eyes …”

There was no reaction.

He dressed quickly and raced to his son’s apartment. Police stopped him in the parking lot. Moments later, he would see a sight he wonders if he’ll ever be able to unsee.

Paramedics rushed Charlie II toward the waiting ambulance.

They had placed him in a Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assist System (LUCAS), a mechanical chest compression device designed for automated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

“It’s the most horrific thing you could ever imagine,” Peddycoart said. “They have to raise your arms to (attach) you to the chest compressor. He was shirtless. It almost looked like it was crushing his chest. It was so disturbing to see.”

The little boy who rushed to his daddy’s arms … The teen who often butted heads with his dad but came to better understand the expectations and the tough love when he had three children of his own … The grown man making his father proud …

Gone. At age 27.

Even as one family was brought to its knees by soul-crushing grief, two other families would soon fall on their knees as well, but to rejoice.

Less than 72 hours after Peddycoart awoke to a phone call, transplant teams in Charlotte and Birmingham got phone calls, as well.

There was a heart for Dixon, a liver for Holloway.

They were from Charlie II, who registered to be an organ donor when he got his driver’s license.

Three years removed from their transplants, Dixon and Holloway still can’t imagine the

sorrow Peddycoart endured in the time between that early morning call and the moment he gripped his son’s arm and whispered goodbye.

“For me to live someone else had to die,” Dixon said. “That was playing in my head every single day. Somebody’s going to lose a father or a husband or a son. So, I’ll be honest, there was a little bit of guilt there.”

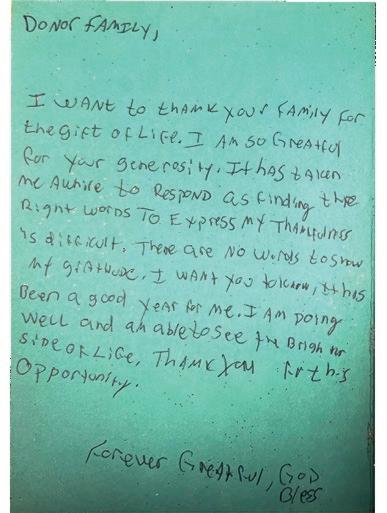

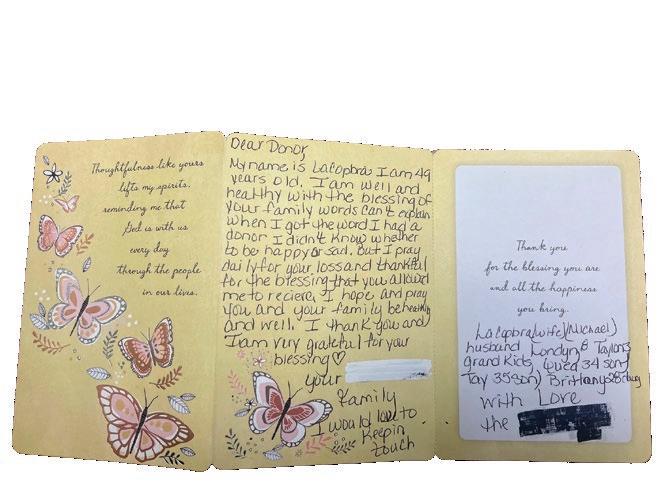

“When I got the word I had a donor, I didn’t know whether to be happy or sad,” Holloway wrote in a card to Peddycoart’s family, a year after her transplant. “I pray daily for your loss and (I’m) thankful for the blessing you allowed me to receive.”

Peddycoart can’t remember the precise moment he heard from a representative of LifeLink of Florida, the non-profit organ procurement organization (OPO) for 15 counties in west and southwest Florida.

But he offers nothing but high praise for the compassion of LifeLink staff and how they walked him through honoring Charlie II’s desire to be an organ donor.

LifeLink of Florida facilitates the recovery of organs for transplantation within all hospitals in its service area including Lakeland Regional.

There are 57 organ procurement organizations in the United States, and they all must overcome myths about

being an organ donor. The most prevalent among every segment of the population is this … Medical personnel won’t try as hard to save your life if you’re an organ donor.

Dixon, who turns 54 in December, said he would love to devote the rest of his life to debunking myths like this one, to travel the country as an advocate for organ donation.

He coded on the operating table after a massive stroke in 2019 and the medical team worked for 15 minutes to bring him back, he said.

“I’m an organ donor so obviously they don’t let you die,” Dixon said.

Organizations like LifeLink are contacted only after tests determine brain death.

“If you are sick or hurt and go to the hospital, the doctors and nurses will do everything they can to save you,” said Jennifer L. Krouse, Foundation Director for Public Affairs for LifeLink Foundation. “Hospital staff do not check if you are a registered organ, eye and tissue donor – only recovery organizations can do that. Donation is considered only after all efforts to save your life have been made.”

Currently, Krouse said, in the 15 county LifeLink of Florida donation service area, about 41 percent of people getting a driver’s license register as donors. Statewide in Florida, the average is 36%, she said. (If you didn’t register as part of the driver’s license process, you may register online at any time by visiting www.MyStoryContinues.com.)

More than 5300 people in Florida are waiting for an organ transplant, according to LifeLink’s data.

Peddycoart desperately wants to see more people register as organ donors, and he urges everyone registered to discuss wishes with all organ donors in their family.

He and Charlie II did not have that conversation. He seemed fine when Peddycoart hugged him goodbye on the evening of Oct 19. But there were underlying, unknown health issues, Peddycoart said.

He opted for his son’s internal organs to be donated.

Organs and tissues that can be recovered for transplant include the kidneys, liver, heart, pancreas, lungs, small intestine, bone, tendons, heart valves, skin and corneas. One organ and tissue donor can potentially benefit more than 75 individuals.

“I wish I would have done more, but for some reason we chose just his internal organs,” Peddycoart said. “They asked about his eyes. For some reason I don’t know … It felt like it was taking something away from his soul. I’m not ashamed of that decision. I’m just not sure why I made it.”

Krouse, too, encourages families to discuss specifics of organ donation so intentions are clearly understood.

“The last thing we want to do is create a more difficult situation for families,” she said. “My passion is for donor families. I am in awe of their strength and generosity, that they can make decisions to take care of others when they’re in the midst of loss.”

ORGAN DONOR MYTH: MEDICAL PERSONNEL WON’T TRY AS HARD TO SAVE YOUR LIFE IF YOU’RE AN ORGAN DONOR.

Doctors, nurses and staff lined the hallways at Lakeland Regional for an honor walk as they moved Charlie II’s body to an operating room for organ recovery.

“It was super emotional,” Peddycoart said.

“We got down there and it’s basically the last time I’m going to touch his hand. They had a trauma come in. So, the team that was going to recover the organs had to switch to that. I am literally at the door of the OR saying my goodbyes and they had to take him back out. I chose to let him go back up with his mother. I felt like I had some closure.”

He went straight to his grandson, Charlie III, who was with a relative.

“I picked him up and he had a severe ear infection,” Peddycoart said. “I didn’t know what to do. I went back to (Lakeland Regional) with him while my son was down there in the operating room …”

They asked for Charlie III’s date of birth in the emergency room.

“I said 9/13/95,” Peddycoart said, again fighting back tears. “I said, ‘Nope, I am sorry.’”

He had given them Charlie II’s date of birth.

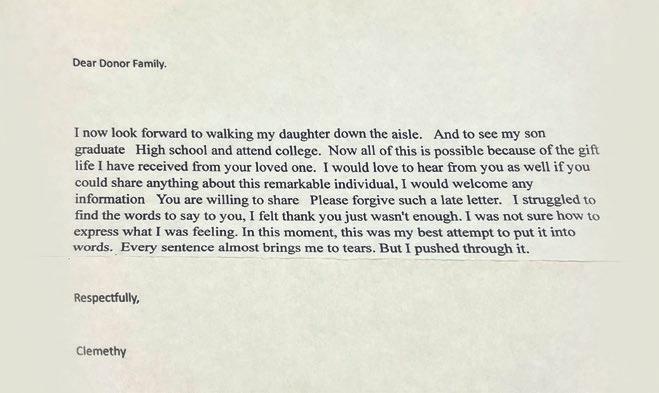

In his letter to Peddycoart’s family a year after receiving Charlie II’s heart, Dixon wrote of how he looked forward to walking his daughter down the aisle some day and to seeing his son graduate from high school and attend college.

Three years removed from the transplant, he calls himself a “very, very different” man.

“What I’ve been through has made me so appreciative of every little thing,” Dixon said. “It gives me purpose. My kids say I’m a better father since the transplant. It is amazing to have your children say you’re a better person. I am here for a reason. Every day I get up I believe that there are really big things ahead of me.”

Holloway, too, speaks of being changed.

“I had a rough time in my life before. This really has changed me, made me be a bigger, better person,” she said. “I’ve always loved hard and now I don’t try to take anything for granted. I live day by day, trying to do the right things.”

She keeps the youngest of her three grandchildren so her daughter can work and loves to cheer at another granddaughter’s softball games. She got to see her son graduate from Alabama State University.

“I thank God I’m still alive and thankful to the family for what they’ve done for me and my family,” Holloway said. “I think about it every day. I could have been gone.”

Neither Dixon nor Holloway had close calls with organ rejection. Both said recently that they are healthy and well. Dixon had some minor inflammation in the heart after the transplant, but treatment cleared it up “in a day or two.”

“That was the only hiccup,” he said. “I serve an amazing God.”

In the aftermath of great loss, Peddycoart gained family in Dixon and Holloway.

He met them within a week of each other in the fall of 2024. He had his grandson – Charlie III – at both meetings. Charlie III is autistic. He lives with Peddycoart now. It’s just the two of them.

In the days leading up to the meetings, Peddycoart was a nervous wreck. “I hadn’t had butterflies in my stomach over anything in a long time. I don’t get scared. I don’t get nervous.”

He describes both meetings as “super easy.”

“Immediately, it was just like family.”

ONE ORGAN AND TISSUE DONOR CAN POTENTIALLY BENEFIT MORE THAN 75 INDIVIDUALS.

Dixon also served in Operation Desert Storm. He is retired from the US Air Force. He’s a huge Georgia Bulldog fan, while Peddycoart is a Florida Gator fan. Dixon skipped attending the annual football game between the rivals to meet Peddycoart last year.

The connection Peddycoart has with both Dixon and Holloway is genuine. (He does not know the names of those who received Charlie II’s kidneys but did receive an anonymous note from one of them. Meeting donor families is up to the organ recipients.)

“Clem, I’m here to tell you I am just as grateful for you as you are for us because my son’s gift to you gave me a sense of pride,” Peddycoart said, at the end of a chat over speaker phone. “You’ll always be a part of our life and family.”

“Thank you, sir. That means a lot,” Dixon said. “Little Charlie (III) is a bonus for me.”

“He’s thriving,” Peddycoart said, proudly. “So many little things every day. The difference between last year and now is almost night and day.”

“I love you, Big Guy,” he told Dixon before hanging up. “I think about y’all all the time,” Dixon said.

When it came time to end his call with Holloway, he offered similar sentiments.

“I am very grateful to have you in my life and for you to be a part of my son’s gift,” Peddycoart said. “It brings

great pride that he was able to do this for you and your family.”

“We are very grateful for you all as well, most definitely,” Holloway, 51, said.

“I love you, Coco,” Peddycoart said.

“I love you, too.”

In a world where urgent phone calls shake you from sleep into a nightmare, in a world where hundreds of people wait for lifesaving organ donations and wonder if today might be their last, those are three words never to be left unsaid.

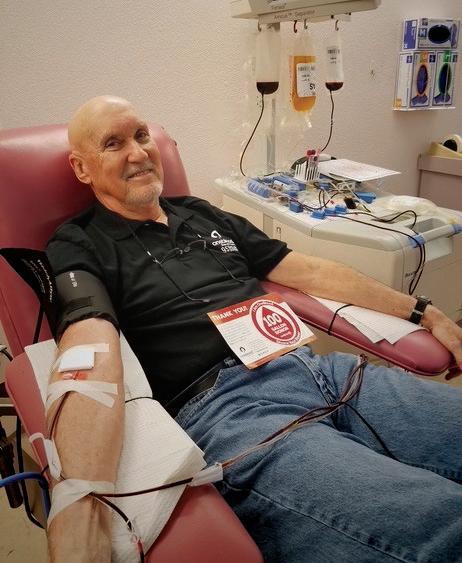

It’s safe to say Bob Harter has done more than his share of sweating across 80 years of life.

He completed 15 marathons, 30 half marathons and shorter races of “all the distances,” even though he didn’t start running until age 45.

But in his younger days, nothing made him sweat like the fear of needles.

“I used to break out in a sweat something terrible,” Harter said. “If I had to go in for a blood draw, it was like I stepped out of a shower. I was soaking wet.”

All that changed late in 1969 when he joined the Army Reserves and reported for basic training at Fort Bragg.

“They hit you in both arms with shots,” he said.

But that wasn’t all.

“At some point early in 1970, they said, ‘OK, we’re going to donate blood for the guys in Vietnam.’”

In his group of about 100, more than half opted out of the blood donation.

But Harter gave and …

He lost it, but not in the way he feared all those years before.

“I lost my fear of needles.”

Over the next 50+ years, Harter never stopped giving.

He donated blood every eight weeks from 1970-1987 before shifting exclusively to platelet donations, which can be done much more often. Both types of donations are critical.

From the United States Department of Health and Human Services:

■ Whole blood donation yields blood that can either be used as a whole blood transfusion or separated into its

by Forrest White

different parts (red cells, white cells, platelets, and plasma) to benefit multiple people. It is the most common type of donation. Shelf life: up to 42 days

■ Platelet donation (the tiny cells that help blood clot) separates the blood to collect platelets along with some plasma, then returns the red cells and most of that plasma back to your body. Shelf life: 5–7 days

Donating blood usually takes between 20-60 minutes, while platelet donations take about 2.5 hours. You must wait 56 days between blood donations. But you can donate platelets once every seven days up to 24 times each year.

When Harter stopped platelet donations a couple of years ago, he had not only reached a rarely heard of milestone – 100 gallons of blood donated – but blown past it.

He donated 114 gallons of blood across those 50+ years of giving.

(For a standard whole blood donation, it takes eight single donations to reach one gallon. One unit of platelets is equivalent to one pint of blood, which means eight platelet donations are equivalent to one gallon of blood.)

Some blood centers estimate only about 12 of 1,000,000 donors will reach the 100 gallon total.

Harter is, quite simply, a lifesaver, countless times over.

While he deflects praise for his dedication to donating blood and platelets, the facts are undeniable …

■ Someone in the U.S. needs blood every two seconds

■ A single blood donation can save up to three lives

■ Only three percent of age-eligible individuals in the U.S. give blood annually

■ A single platelet donation can save the lives of up to three adults and 12 children

Most blood types fall into one of the four major groups: A, B, AB, O.

But some people have rare blood types, and there’s a critical need for donors with rare types.

Harter’s blood type is A positive (A+), which makes up about a third of all requests for blood. So, donors like Harter are in high

demand. (He actually had two friends request he donate blood for their upcoming surgeries, and he obliged.)

First United Methodist Church partners with OneBlood, a not-for-profit 501(c) (3) which provides lifesaving products to more than 250 hospitals in Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas.

OneBlood’s Big Red Bus is on campus for blood donations on the second Sunday of every other month from 8:30am12:30pm.

They make it easy by coming here to you.

Harter worked for 45 years at Florida Tile, which was committed to bringing blood drives to the workplace. He kept track of his donations and gave every eight weeks before the switch to platelet donations. Most years he gave platelets 24 times, the maximum allowed.

But Harter has never been one just to roll up his sleeve for blood donations.

He’s equally as generous with his time.

He has been delivering food for Volunteers in Service to the Elderly (VISTE) for 10 years. He served with First UMC’s Tuesday Tigers ramp building and small repair ministry. You’ll find him packing meals at kidsPACK each month. He delivers food collected on First Sundays to the church’s migrant ministry partners and leads tours at the Circle B Bar Reserve once or twice each week. He has served on short-term mission teams, as well as disaster response teams.

One thing he won’t do?

Try to guilt or coerce people into giving blood. Some can’t and some just don’t, perhaps because of the fear that plagued Harter in his young, sweaty days.

Pastor Charley trying to catch up with Bob!

“I would tell people, ‘If you’re healthy you should do it,’” he said. “The stick? You feel it for a couple of seconds. That’s it.”

Harter smiles his familiar, engaging smile.

“Now did I watch it? No, never.”

Turns out, the needles were no sweat for him after all.

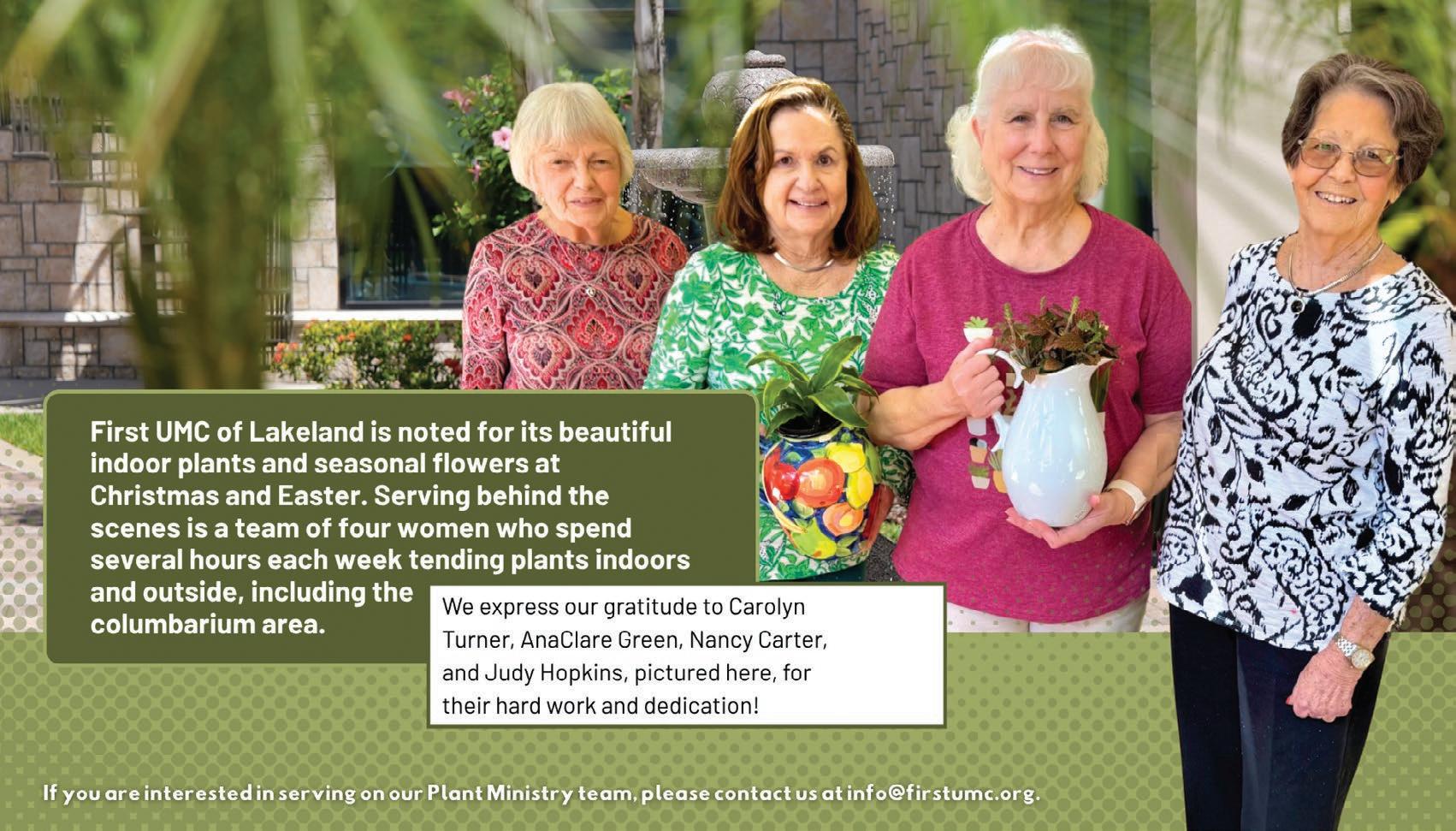

Thank you Plant Ministry Team!

CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICES

(New times this year)

All services are candlelight services

4pm Family service

5:30pm Contemporary service

7pm Traditional service

11pm Communion service

72 Lake Morton Drive Lakeland, FL 33801

863-686-3163 firstumc.org

Written by Forrest White

Charley Reeb