“Poetry advances the quality of life of citizenry when organized as a precious power tool.”

–

Semaj Brown

“Poetry advances the quality of life of citizenry when organized as a precious power tool.”

–

Semaj Brown

Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice™

On Panelist Papers

Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice™

On Teachers

Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice™

Media

“...

- Semaj Brown

...”

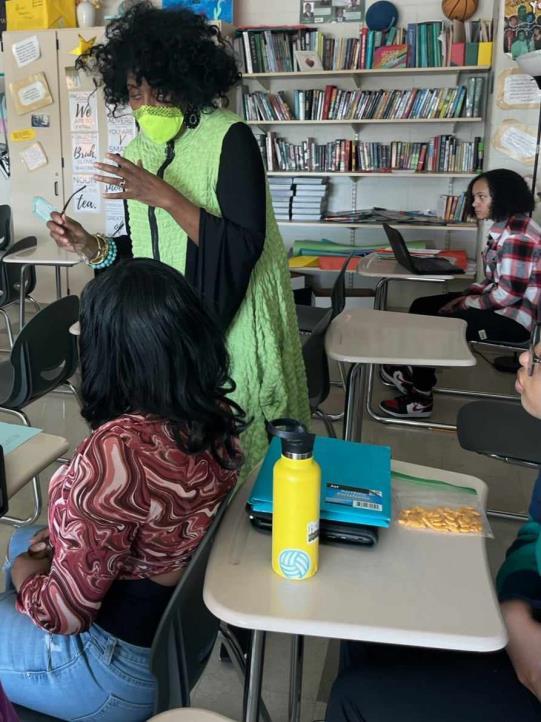

Featured photo: Panelists who spoke at the Community Wide Convergent Voice Workshop, held at the Flint Public Library

April is National Poetry Month, 30 days of celebrating joy, expressiveness and pure delight of poetry, according to ReadingRockets.org!

In celebration of National Poetry Month, the Courier is sharing “Black Dandelion,” the highly acclaimed poem by Semaj Brown, as well as papers written by panelists at a local event in response to the poem.

Edith Withey has served on numerous committees, including Board of Directors for the United Way of Greater Flint, executive committee of the Flint area United Negro College Fund, and on the executive board of her church; Kingdom of Heaven Ministries. She also served as art instructor under Ms. Brown’s project “The Vegetable Kingdom” at the Boys and Girls Club of Flint. Mrs. Withey holds the distinction of being the first African American Dean at a major University, Kettering University, in Genesee County. She presently serves as Vice President of the local chapter of the Pierians, a national non-profit organization that promotes and celebrates the fine arts in the Flint Area. She is always involved in art projects at the Flint Institute of Arts and other local art galleries. She has two children, six grandchildren and three great grands.

By Edith Withey

Introductory Comments

Black Dandelion made me think about my neighborhood, where I grew up. I grew up in the old St. John Street area. I know I'm dating myself, but I grew up in that area, and we had a lot of weeds in our lawn. My mother kept the lawn mowed. Dandelions were part of the landscape, the beautiful landscape, because who could afford weed killer at that time? I remember the dandelions in my youth. I remember the best part of the dandelion was when it went to seed, and we would take the dandelion, and blow. If my mom had known that we were just spreading the dandelions all over, she would have worn us out.

We used to play games with the dandelions. We would pick the petals and say, this means we're going to get married; this means we're going to do this or that. I used to pick a dandelion and say that I was going to do great things in my life. My friends and neighbors would laugh at me. They would say, “You're the poorest one here, look at where you live.” We lived in what many of you, most of you probably do not know. Have you ever seen a basement house? A basement house is a house where the basement floor is completed, but nothing else. In Flint back in the day, we were one of seven houses allowed to live in a basement house because my father died and left an insurance policy. My mother said, “We'll build our house,” but she ran out of money before the first floor was completed. So, the house basement was high enough to reach the dimensions where you just had a front door. When you entered, you would go down the steep staircase into the basement. There was no first floor, only a front entrance that would stick up/out above the ground. We lived in a basement house, always underground until I went to junior high.

Therefore, we were the laughingstock of the block. Kids were laughing at us all the time. We were the ones everybody laughed at because we lived in that type of home. And, I tell you this to say, all things are possible If you believe. If you believe the dandelion can really grow, develop, and flourish, then it can. It will. We were just like some of the kids here today. I said, I'm going to be somebody. Just watch. I'm going to go to school. Just watch me.

And you know who my hero was at the time? My heroes were books about a family who lived in a train box car, authored by Gertrude Chandler Warner. It was a large family, and they were all happy living in that train box car. I had a basement, and they had a train. I could be happy too, I thought. And they all believed that they were going to be someone. So, when I read those stories, I related those stories to myself, and knew that I too could be somebody. No matter if I wasn't a good spelling student in high school or junior high. I knew I could achieve beyond what I saw before me. That is the main thing about being a black dandelion, though I was a black dandelion, I knew I could achieve much. And I did. I achieved all my goals plus seven.

Darolyn Brown is a poet and novelist. She hails from Detroit, Michigan and holds a Master’s Degree in English from Wayne State University. She was a teacher of English and creative writing (Poetry) for almost 35 years in the Detroit Public Schools. She enjoys working with the Flint Reads Pod Poetry Project (P3) as a literary consultant because she will not pass up an opportunity to bring poetry to the people. In fact, it is her life’s work.

The way a poem is written helps to convey meaning because one can glean meaning from content. If there is an unfamiliar word in the stanza, the surrounding words will provide a clue to its meaning. This poem, “Black Dandelion”, is filled with very vivid clues.

As one reads, the mind tries to put ideas together, in order. When an unfamiliar word crops up, the mind is already associating it into the context. The words “twirling” and “return” help the reader suspect that the unfamiliar word perennial means continually recurring.

Looking up unfamiliar words will guarantee success in understanding the poem’s full intent. Instead of having to surmise meanings, one can pinpoint them and realize the poem’s full impact. For example, monochromatic, is used in the poem twice. It must be important. It is being stressed. Society favored a monochromatic landscape and the Johnson boy was shot by the police for growing in a monochromatic landscape. There is obvious something dangerous about a landscape that consists of only one color, as monochromatic is defined, or in a larger sense one way to be.

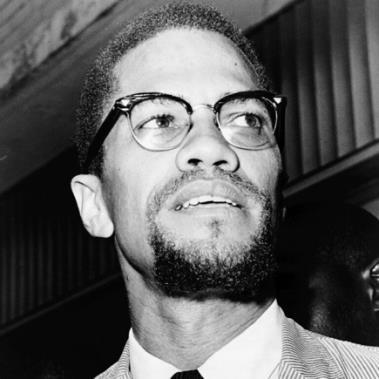

In continuing to glean meaning from the poem, one can notice that first the dandelions were mowed down and later prosecuted. Then we see that Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr were assassinated – which means- the act of

murdering a famous person in a surprise attack- as the poem says a big word for a pre-kindergartner, but in looking it up, we see it is exactly the right word. So, again looking up unfamiliar words helps the reader embrace all the significance of what is going on in the poem.

Being familiar with the meanings of unfamiliar words also adds to the mood or tone of the poem. The meanings of the words solidarity and endurance put together creates a mood of strength. And they are seamlessly joined by the word ephemeral which says that they are only meant to last a very short time.

But, understanding what solidarity and endurance means, one knows that the ephemeral is just an illusion and the dandelions will overcome and succeed through the spirit of the weed.

The poem, “Black Dandelion”, is a beautiful poem that packs a whole lot of meaning. One can understand the poem through sensing the context of the words, phrases, and ideas. But, one can fully realize and interact with the subject of the poem by looking up unfamiliar words. They have all been chosen for their exact meanings and connotations and placed specifically where they will give one the true meaning of the poem.

Sonya Pouncy is a Callaloo Fellow with a Master of Arts from Central Michigan University. Her poetry has appeared in journals including Callaloo, Temenos, Aunt Chloe: A Journal of Artful Color, Drum Voices Revue, and in the anthologies Respect, Poet in the House, and Abandon Automobile.

Sonya is also an engineer with 20+ years of experience in the HVAC industry. Her firm, Building Vitals, helps facility managers identify, understand and bridge the gap between where their building performance is and where they want it to be.

Equality, Empathy and Energy in Semaj Brown’s Black Dandelion

Poetry is a special kind of lens that allows us to see and understand things differently than we would otherwise. It bends the light emanating from things so we can see their component colors and nuances. It also concentrates and focuses that same light so that we see things more clearly, more wholly. To do this work, poetry uses several devices. Chief among them is the metaphor.

Metaphor is a type of figurative language that makes comparisons between things. We make comparisons to understand things more fully. With metaphors, the comparisons are often between things that, on the surface, appear very dissimilar. But metaphors show us how the things—usually two, but it could be three or more—are more alike than we originally thought.

Similes make comparisons, too. But they use helper words, such as “like” or “as” to let you know they’re making a comparison. For example, in Line 3: “I fell, curled like a snail in grief” and in Line 10:

“Warning signs hovered like low hanging clouds.” Metaphors, however, make their comparisons differently. On one hand, they are more subtle because they do not use helper words and on the other hand, they are more forceful because they don’t say one thing is like another, instead they assert that it is the other. Metaphors set up an equality. Metaphors make things equal.

For example, in the “Flowering bouffant” of Line 6, without even using the word dandelion, the flower is described in such a way that we see how it is like an afro, even before we are told that it mirrors the narrator’s afro. (Technically speaking, this is metaphor mixed with metonymy, but we’ll save that discussion for another time).

Or, in Line 15, when referring to Malcolm X, the narrator says: “he must have been a dandelion” inviting the reader that’s us to think about not only how Malcolm X was like a dandelion, but also how the dandelion is like Malcolm X. And, how dandelions are also like Martin Luther King, Jr. This comparison is particularly interesting because—if we remember the transitive law from math class—if Malcom is equal to a dandelion and Martin is equal to a dandelion, then Malcom is also equal to Martin. In the media, these two men, who only met once and only for about 60 seconds, are often depicted as polar opposites. But with this ever so subtle metaphor, Semaj asks the reader to ponder their similarities, what they had in common, how they were, in fact, the same. And if your mind wasn’t blown by that, it must surely be blown when she also asks you to consider how Malcolm and Martin are like the “Johnson boy,” since he’s a dandelion, too.

Semaj also invites us to explore how we are like the narrator. She does this with another poetic device, the persona. The narrator is speaking in first person. We often assume this means the narrator is also the author, but this is not necessarily so. Regardless, use of the words “I,” “my,” and “me,” places the reader in the poem because when we read

the poem, we don’t replace those first-person pronouns with third-person pronouns. We say “I”, too. We say, “me” and “my.” By saying those words, a switch is flipped in our brains that allows us to imagine ourselves as the person in the poem. We get to walk in the narrator’s metaphorical shoes. And Semaj makes that easy for us, because even if we hadn’t thought much about dandelions before encountering the poem, she introduces typical childhood events with which we very likely can identify. The narrator speaks of being “snag-a-tooth” (17), riding a bike for the first time without training wheels (18), and giving a speech on Youth Day at your house of worship (29-32). When I was a child, my church didn’t have a Youth Day, but I vividly remember dressing up and going to my great-grandmother’s church to give my Easter Speech every year.

By allowing us to walk in her or his shoes for a while, the narrator invites us to identify and empathize with her- or himself: to understand his or her feelings from the inside. We feel them, too. We feel the narrator’s pain at witnessing that “first mow down” (1) and we, too, want to curl up “like a snail in grief” (3). We may not struggle with saying “assassinated,” but we can feel how that is a “big word for a kindergartner” (14). It’s a heavy word, even for an adult (note, that heavy was a metaphor).

Not only do we share the feelings of the narrator, we share the energy, too. We also get to frolic (8), we also get to pedal, ride our bikes, and wave to the dandelion’s “surviving, sunburst noggins” (18-20). And, triumphantly, we also get to stand firmly, resolute with shoulders back—even though the poem doesn’t say this, this is how I imagine myself to stand when I declare with the narrator that “I [too] am a proud weed”, that I, too, am among the “Black Dandelions who will NEVER be destroyed” (34).

One final point about the narrator’s energy. If we recall from physics or science class, energy is defined as the ability to do work. So, because this poem has energy, has “intention,” this poem works. Some poems are whimsical, just for play and that’s fine. But this poem is not and it tells us so using yet another poetic device, personification the giving of human attributes to something not human. The poem tells us that:

“Dandelions bare art of endurance and escape

transforming into pearl puffs

floating with ephemeral intention carrying the spirit of the weed.” (23-27)

Notice the almost imperceptible sleight of hand here that might, at first glance, be mistaken as a malapropism. The dandelions “bare [the] art of endurance and escape,” but it’s not B-E-A-R, as if they were carrying the weight of endurance and escape. It’s B-A-R-E, as in they are laying something bare for us. They are uncovering, the “art of / endurance and escape.” They are making known something that was unknown because there is something the poem wants us to understand. That is that enduring a thing and escaping a thing are intrinsically connected. That together they are an art—an activity that stimulates thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and ideas. And, that their art is exemplified in the cunning and persistence of the dandelion, and is similar to the way David prevailed over Goliath.

Everyone one of us, no matter how young or old, has something that we’ve had to endure or escape, something we’ve had to grow “in spite of.” It may be weighty, like knowing someone like “the Johnson boy who lived one turn down the street, that way” who “was shot by the police” (16-17). Or, it could be as light and airy as the “amused and mortified” stares of “hat-framed faces” (36-37) on a Sunday afternoon. What have you endured and escaped? How have you or how has someone you know “transformed into pearl puffs. […] carrying the spirit of the weed (25-27)? In what ways are you, too, a dandelion?

I am Dr. Sunanda Samaddar Corrado and I have been a close friend, a collaborating artist and a consultant for Mrs. Semaj Brown for over 20 years. My doctorate in Comparative International Education (CIE) has made me familiar with different educational policies, spaces and practices around the globe, from elite education environments to the needs of displaced communities of war and poverty. I have extensive experience in organizing platforms that address diversity and change in educational policy. I have organized a congressional debate for the historical 13th district, as well as a panel to address the unique possibilities of Parochiaide to address the recent decisions of the US Supreme Court in allowing public funds to be used for parochial education. I have been a researcher for the Detroit Equity Action Lab (DEAL) authoring the most extensive timeline of education for the city of Detroit, which will be published online in an interactive format. I co-host a show called the Sisterhood on a subscription based platform, the Urban Information Network (UIN). I have been a board member for various organizations including the Highland Park Chamber of Commerce, as the chair of their education committee and Refuge for Nations, a non-profit dedicated to creating entrepreneurial spaces for immigrant women from their homes. As adjunct professor of anthropology, I continue to chair the Bangladeshi Cultural Club at Wayne County Community College District. I have consulted for various educational projects including Flint’s Poet Laureate, Semaj Brown’s literacy advocacy program based on her Semajian Method.

In celebration of Women’s History month, I chose to explore the allegory of the Black Dandelion. Specifically, I wanted to reflect together about how a flower can also exist as a weed.

Immediately, my mind begins to circle: What is women’s history? What does it

look like? If you were to ask the same question in school, the idea splinters further: there is feminist history, theories of performativity, queer theory etc. If you go to seminary or take an African American lit class, you may finally stumble across Womanism. So let’s drop what we think is familiar, and I ask the question, at a much later stage in my own life, Is womanist history not a Black Dandelion?

The term ‘womanist’ was first introduced by author and activist, Alice Walker, in her 1982 publication In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: Womanist Prose. Since then, literary scholars have begun to conjure a voice from the past, between the shores of memory and amnesia, humiliation and triumph, a truth in the form of ghosts and goblins. Womanism is rooted in the history and everyday experiences of Black women. Womanism seeks to explore the imbalance between people and nature, reconciling human conflict with the spiritual dimension of our collective immortality.

Afterall, Black women experience more violence, for lower pay. Sisters who are fetishized objects of repressed desires who find little reflection of their own realities in the media and political representations. Because mainstream feminism does not address racism or desire, a parallel, womanist movement formed to acknowledge black women’s struggle for humanity - for themselves, their children, their lovers and their brothers. Just as Christ’s body was shared and consumed, is the Black woman’s blood not wine? Is the wafer offered not an issue of her own flesh?

Semaj Brown’s Black Dandelion is very much reminiscent of - and harnessed tothe same mutilation, pain and disembodiment of the Black Woman’s body even as she celebrates the triumph of the Black Dandelion’s beauty and her rich botanical treasures.

What is in a name? White or Black? What if a flower were to be referred to as a weed? And why is this flower sentenced to such derision? Is it because of the Black Dandelion’s unrelenting spirit or is it because of her unconscious intrusion into our collective Conscience? How does her longing, to return to where she had once and will always belong, infect me with such melancholy?

Even as Alice Walker describes her mother’s gardens as the blossoming sieve through which she experienced an impoverished childhood: she continues to describe every Black woman’s experience in viscerally straggled terms. A double consciousness of sorts, like a square circle, even as Ms. Walker’s mother struggled, she created without force of effort. Ms. Walker declares that her mother was not a saint, but in fact an artist with intuit beauty made manifest in bleakness. Alice Walker’s mother gave life to gardens in the gallows, even as she birthed, harvested, scrubbed and swept, quilted, sewn, or cooked, she created. Alice Walker’s mother was never a saint, she was always the Creator.

Similarly, Semaj Brown writes:

Dandelions bare art of Endurance and escape

Transforming into pearl puffs

Floating with ephemeral intention

Carrying the spirit of the weed (lines 23-27).

And how do we mean the spirit of the weed? Is the dandelion not a flower? What

is this transformation? What is the “spirit of the weed”? At the beginning, did the poet not liken the flower to her four year old narrator?

Flowering bouffant mirrored my spikey little afro

Jagged edged “lion’s tooth” leaves paid tribute to my snag-a-tooth smile (lines 67)

Sweet, innocent, gawky and mischievous, how did this child-flower come to carry the spirit of the weed? Towards the end of the poem the little girl says:

…”I am a weed!”

Yes. I declared that shocking proclamation standing

In the pulpit of Youth Sunday Vernon Chapel A.M.E. (lines 28 - 31)

I yet remember the hat framed faces of the pious, amused and mortified (lines 36 - 37)

Notice Mrs. Brown’s own use of contradiction: “amused and mortified”. For the girl child spoke to a congregation of weeds. Yet, how does a flower come to perceive herself as a weed, even as the congregation sits before her in bewilderment? Could it be because of what happened to:

… the Johnson boy who lived one turn down the street. that way. The Johnson boy was shot by the police for growing in a monochromatic landscape.

(lines 16 - 17)

Perhaps, in WEB DuBois words, she was: “born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight.” Not able to live her own, self-conscious life, the girl child with her “training wheels off (line 18)” must “ride across insecure cement (line 18).” She pedals “the bumpy path waving solidarity (lines 19 - 20)” to her dandelions in existential torment for Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and the Johnson boy.

In Langston Hughes’ The Ways of White Folks, he skillfully weaves womanist prose into each of his short stories. These are intimate stories of asymmetric love and perpetual loss. How does one convey such pain from just a pile of words? How does Womanist prose conjure a parallel spirit world reality? He writes from the voice of Oceola:

“This is mine… Listen! How sad and gay it is. Blue and happy - laughing and crying … ho white like you and black like me …How much like a man … And how much like a woman … These are the blues I’m playing.

However, Alice Walker beckons for us to surf the waves of binary bifurcations. For all such contradictions are folded into a paradox of existence where “Blossoms will be prosecuted!” (line 11). A world filled with Death and fertility, childhood innocence and “Dandelion Dogma.” You see, these shorn petals disguise the existence of the whole flower, for 12 full moons later: “Perennial promises prevailed” and the “Bees celebrated return of dandelions in a skirt of twirling bliss” (lines 4 - 5).

Alice Walker mused that such a schizophrenic existence between life and death cultivates a certain brilliance in a Black woman’s creativity. Stunted perhaps at first, but then unknowingly, unceasingly, unconsciously evolving within an environment where being perceived as a weed is the norm, is expected. What else

could you be as a Black American? Like Moon Flowers, the Casablanca Lilies or the Nottingham Catchfly or the Evening Primrose, throughout history, Black women have learned to bloom only at night, sometimes without one ray of hope or transcendent light beam to caress her soft and delicate petals.

Similarly, reference to a Black Dandelion only blooms at the end of the poem. Whereas the journey through the poem aligns the beauty of the dandelion’s deep golds and myriad shades of yellow with brightness, light and vulnerability - conspicuous to our conscience, mowed down by murderous blade; Each individuated dandelion is either mourned or saluted by the girl child who continues to develop into consciousness in the midst of violence of 1965 to 1966. However, by the end the child reclaims the principle of being a flower as her Dandelion Dogma. Standing before her church, she declares:

“WE are Black Dandelions who will NEVER be destroyed. We grow the power of goodness for generations into the future!” (lines 34 - 35)

This simple and strange declaration rearranges and resignifies the images of the dandelion, seeping into the previous stanzas of the poem in three brilliant ways: Firstly. The Black Dandelion is about the girl child actively transforming her own reality, seeing connections between the violence against her people as parallel to the violence she witnesses against Nature. Secondly, the lives of these lone dandelions targets are resurrected in the pronouncement of “We.” For the line “we shall never be destroyed” conveys the resilience of the indestructible soul,

perhaps a cruel revelation, how her ancestry is the ancestry to ALL is in the ironic iteration of Blackness as conveying a conscious mind to the Dandelion, and its collective reality. Thirdly, the child inverts the social meaning and value of the dandelion, declaring herself not only to be a weed but that in fact a Black weed, a double negative, one might think, at once internalizing larger social standards in triumphant subversion.

For even as flowers are mowed down, banished from the garden of men and power, they survive, and most impudently thrive, perforating neighborhood lawns with scrawny stems and snag-a-tooth smiles. Mrs. Brown at once transforms the survival of the dandelion with the lynchpin of earthly existence. This child, divided from within, torn from her women’s ancestry, bamboozled by beauty standards that aim to control her body’s reproductive and hard labor; This child - makes visible through imagination, a rapacious and ugly system that envies what they have for so long leered as Blackness. Scraping men and women of their memory, of their right to divine rule, decapitating crowns of autonomy and self-expression: demanding that these petals be straightened or covered - even as they speak against covered heads of other women from other worlds, Black Dandelion is at once at odds and in sync with human destiny.

The reality is that there exists no such thing as a weed, there exists no such thing as Black and White. Blackness is the seed from which all reality is made manifest. These weed ideas are transformed and transcendent “pearl puffs”, not by Nature directly, but by the shared circuitry of possessive guilt and demonic denial of what is obvious to the little girl: that unruly nature cannot be ruled. These ideas of rule and order bear no seed of life. Yet, these diseased perception only seem to entangle and evolve through Nature’s own will to be free.

“On

behalf of All the Black Dandelions who turned their Power into Seed, to Live, to Grow again, THANK YOU!

- Semaj Brown

”

Administrator/Educator

“Black Dandelion means a great deal to our students here at Peckham Career Academy. When the poem was introduced to our students, it was exactly at the same time when our entire student body and staff lost one of our bright lights. We lost a student to gun violence. Willie Smith was the student that we lost, and he is our Black Dandelion the poem is about a four year old little girl and her experiences during the Civil Rights movement and how dandelions are mowed down and how that correlates to the people that were lost to violence during the Civil Rights movement. And it transcends into what we experience here collectively as a family at Peckham Career Academy. So our students use that, use their sadness. It was channeled through their artwork, their expressions of love and admiration and sadness as a result of what they experienced. They used all that to create again, they created artwork. And it was therapeutic, and we are grateful for it. So that is what Black Dandelion meant to us. Again, it was therapeutic and it was a labor of love for all of us.”

Davina Whitaker

Educator – 6th Grade

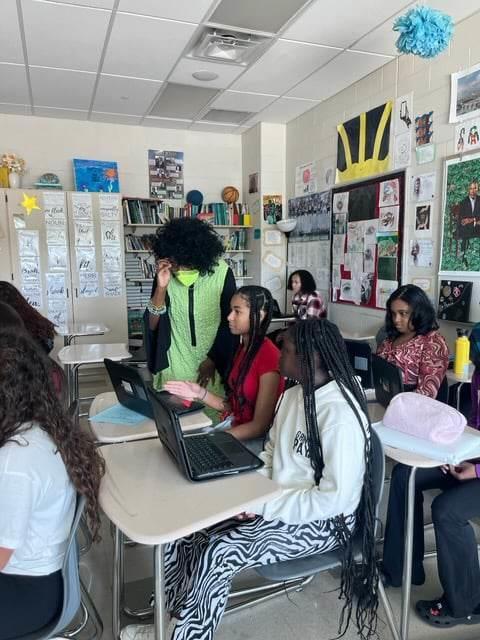

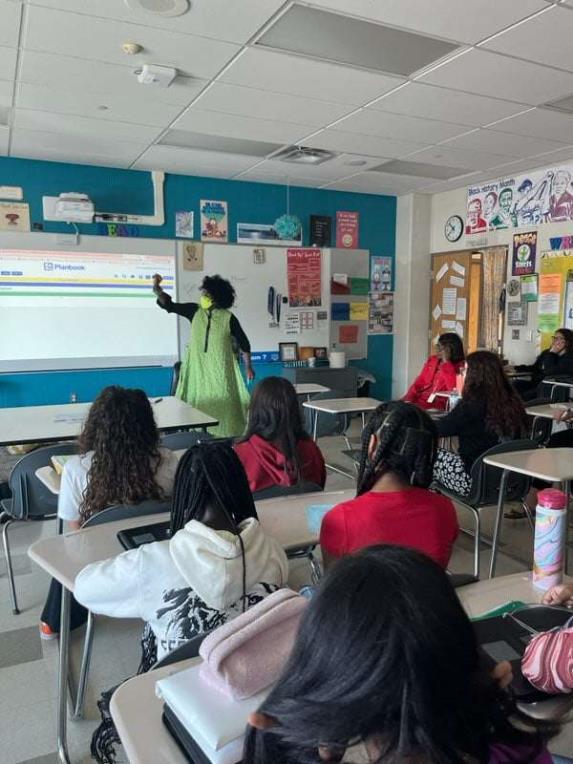

“I just want to say how impressed That I was with the Black Dandelion presentation, I felt like my students were really engaged when Ms. Brown presented the poem to them. We were able to talk about what metaphors are and

being able to understand how the dandelions in the poem were a metaphor for African Americans. And then as a follow up with my class, what we did was we talked about how we've had some African Americans in our present day who have been mowed down, people like George Floyd and Brianna Taylor. And it kind of brought it real world to them because they could relate to those incidents that have happened in their current time compared to the young lady who was seeing African Americans being treated unfairly during the poem. So I was just really happy that we were able to be a part of this project and that the students were able to experience this poem.”

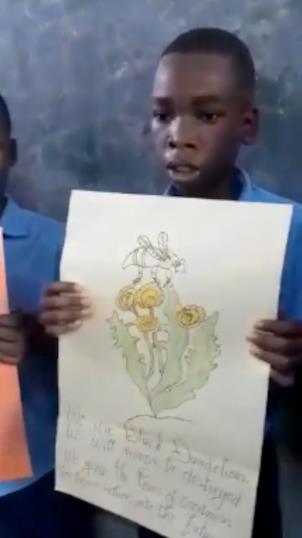

Amevi Ahocou Founder/Director of Ecole Konoura Togo

“Good evening, Black Dandelion. What a project! We love it here at the Konoura. Thank you, Mrs. Semaj Brown so much for including us in your project, what an honor. We have studied Black Dandelion here in Konoura; we enjoyed this project. We looked at it from so many different perspectives.

The staff, we discussed how you cannot kill Black Dandelion. That Dandelion is so strong, so strong, it cannot be killed, generation after generation, it will keep reproducing. We talked about how the seeds fall from the black dandelion to reproduce. We decided to take that approach, introducing it to our children in the form of science. The wind was between the seasons here. Our season is now for the black seed. This is the season between, um uh between the rainy season and

the dry season. It is bee season! Therefore, we decided to explore bees and flowers.

As you will see in the video, the Dandelion is the flower the bees are feeding off from so the bees might go and reproduce the honey. This was our introduction to our students. All aspects of science we covered. The children came up with their own skit. Everything that you see in the video. The children did it themselves. They planned how they would dress. Did you see the yellow Book bag? I love the book bag. That's the seeds flying all over from the dandelions.

You cannot kill Dandelions you cannot kill, especially black Dandelion, cannot be killed. It can only be reproduced. Our Children loved it. I love it myself. I love what the The children came up with; and, it was a perfect match to incorporate what is going on in their natural lives, bee season! I love those children. Thank you again, for inviting us and including us in your project. Thank you so much.”

Carrie Mattern

Carmen Ainsworth High School

English Language Arts Educator President-Elect Michigan Council Teachers of English MCTE

“Semaj Brown continues to create programs for students and adults alike, for educators and writers, and for everyday artists who are deeply moved by words. She serves the future of Flint, as well as those overseas and in different states working through her Black Dandelion programming. I know my students loved her Afrofuturism take on the poem, as they too, studied it earlier

this year. Semaj is impactful, creative, inspiring, and such a beacon of creativity for our state.”

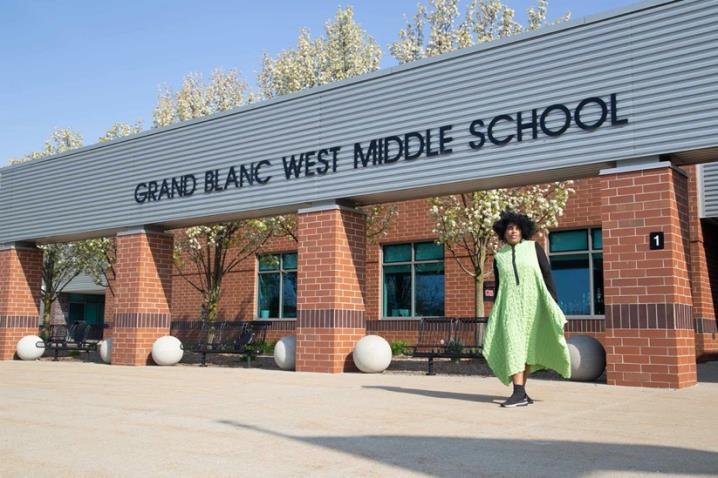

1.How did find out about Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice BDCV?

I walk my dog regularly in my Southside neighborhood in Flint. One of the good things to come out of Covid was I met so many wonderful neighbors. Mrs. Janet Cameron, a retired, English teacher is one of the kind souls I connected with during Covid. Being an ELA teacher myself, she always inquires about my classroom and students. Further, she knew that I was teaching the first Black History class K-8 in Grand Blanc Schools. In the Fall, she introduced me to your Black Dandelion Convergent Voice program. And provided me with all of your resources. She is the sweetest of people and her desire to keep teaching/informing folk is a character trait I hope to carry beyond my classroom.

2.What were the memorable points of engagement from the students?

My students like myself were unaware that there was First Female Black Poet Laurette in Flint. So it felt great to share this history-making moment with them. We have a segment in the class called Little Known Black History Facts and it is empowering to share a local and recent history as well as the past. After we engaged in reading and breaking down the poem I offered a choice to participate in the convergent voice part. We took several days to allow kids to find an authentic voice to share. A memorable moment that I recall was when another teacher reached out saying Miracle shared her poem with her. She was so moved by the writing she emailed me to express her awe of Miracle's thought-provoking and moving writing.

3.What were your thoughts about the poem, and how a singular poem generates lessons across the curriculum?

The poem resonated with me. According to the text, the protagonist is a year older than me, so my first thought was how I lived part of this history and although I was three at the time of MLK's assassination I now can see how some of my early years were informed by this time period although I did not make all these connections until I was older, more informed and through texts like the Black Dandelion poem. Second, in addition to my own learning, I find this type of text is a great way to connect with American history. In our Black History 365 class, we have had much learning on the joys, struggles, accomplishments,

growth, and setbacks regarding Black history in the United States. I think my students are able to connect to poetry on another level and it offers a less intimidating way to share history.

4.How did BDCV enhance the historic happening of being the first teacher to teach the first Black History class in the Grand Blanc school system?

This lesson blended well with the topics we were already learning. Although I had the information for BDCV in the Fall I waited until we hit this specific time frame in history to engage in this project. It was helpful to have the students have prior knowledge before as well the poem was able to reinforce our learning. Further, having our student work showcased on a bigger scale ( The Flint Courier) also informs our administrators as well as parents about our learning. Last, just like our class is making history in Grand Blanc our BDCV experience is highlighting/documenting our journey in a positive way.

5.Please write freely about the process, and possibilities you might imagine.

I would definitely continue to use the Black Dandelion poem in the future. In fact, perhaps next year I would use it in all of my ELA classes. And if you continue to host workshops at FPL I would encourage my writers to join me. I was moved by your panel of speakers at my first workshop. I have many creative writers that would benefit from that type of one-to-one exposure. Now that we have connected I can see all the possibilities for publication of my student's work to having important guest speakers such as yourself come in and speak to my students. Your historical journey fits right in line with what I want all of my students to understand and that is that history is alive and we are all making it together.

Richard Thompson

Greater Heights Academy

1- How did find out about Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice BDCV?

I found out about the amazing opportunity to work with Mrs. Samaj Brown and the Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice™ BDCV through Flint City Council Person, Dr. Ladel Lewis who is an advocate for our school, Greater Heights Academy. With this introduction, Mrs. Brown and I connected on a deep level of purpose and mission and implemented a program with our 6th-grade scholars here at our school.

2- What were the memorable points of engagement from the students?

Memorable points of engagement from our scholars were a plethora. One of the highlights was the journey our scholars went on from studying the "Black Dandelion" to connecting it with their own lives, challenges, and hopes and then creating a poem to exemplify these thoughts.

3- What were your thoughts about the poem, and how a singular poem generates lessons across the curriculum?

My thoughts about the Black Dandelion are that is a masterpiece of timeless advocacy, introspection, challenge, brilliance, and empowerment of all races, creeds, and identifications. This gift of poetry then invites, empowers, and

encourages everyone to speak their voice and use this platform for self-expression and justice.

4- How did BDCV enhance historic happenings?

The BDCV enhanced the historic by first and foremost identifying this most important event as an ethos in history and an opportunity to educate our youth in more than the streamlined curriculum that may not respect all aspects of history and voices.

5- Please write freely about the process and possibilities you might imagine.

The possibilities of the BDCV in our school Greater Heights Academy here in innercity Flint Michigan bring hope and empowerment of having our scholars identify and advocate for themselves and those in their families. The implementation of the BDCV is a worthy and needed cause not just for our scholars yet all scholars in every school in America and the World. It is a poem of HOPE and TRUTH that literally gives "A VOICE" through literacy.

In the words of Martin Luther King

“The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character – that is the goal of true education.”

It is an honor to partner with Mrs. Samaj Brown in the BDCV for the trajectory of scholar formation and education. (Virtus et Scientia - Character and Knowledge)

- Semaj Brown

There is no doubt that the world will be looking for Black dandelions now that the corporation AT&T, in a search, found the video of Flint, Mich. Poet Laureate, Semaj Brown reading her Black Dandelion poem on her website.

An excerpt of the audio recording of the poem highlights a one-minute commercial of the acclaimed Dream In Black, Black Future Makers Afrofuturistic Lifestyle platform, and is to be aired nationally on television and on social media platforms.

The Academy of American Poets distributed a video of poet laureate fellow, Semaj Brown reading her poem, Black Dandelion to middle and high school students. The poet laureate received letters from youth from across the United States and world via the Dear Poet project. The letters represented a range of ethnicities, Asian, Armenian, Black, white, and more. Exchanges can be read on the Dear Semaj Brown page.

DEEPLY MOVED, SEMAJ BROWN STATES, “THE BLACK DANDELION POEM SERVES AS A GLOBAL HOT AIR BALLOON. IT RISES LIKE HELIUM ABOVE THE TERROR OF SOCIAL INJUSTICES, HOLDING A SAFE SPACE FOR YOUTH TO INTERPRET, AND ADDRESS HISTORICAL, TRAUMATIC REALITIES.”

“The students’ thoughts and feelings expressed in the letters formed a “convergent voice” with the Black Dandelion. They were deeply disturbed by inflicted injustices yet enthusiastically embraced hopeful resilience, the spirit of the weed.”

It was the Fall of 2022, and organizers of the Michigan Council of Teachers of English were anxiously awaiting their Centennial Conference in Lansing, Michigan. Their keynote speaker, Semaj Brown, Poet Laureate of Flint, Michigan and Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellow, 2021, informed them of her special presentation, “PSL, Poetry as a Second Language: The Semajian Method”, and that she would be launching her multimedia youth platform, BLACK

DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE™(BDCV), something that they had not experienced before in education. It is an intergenerational, futuristic platform that utilizes “applied poetry” as an integrative tool. The platform amplifies literacy capacity, improves skillbased learning, and heightens critical thinking, emotional intelligence, and cognitive expansion across disparate disciplines of science and art.

According to research, the pandemic deepened inequities in literacy rates. Students at lower-achieving schools fell further behind, potentially widening the pre-existing achievement gap between rich and poor. The COVID pandemic with its isolation and virtual teaching, exacerbated the problem of children not reading on grade level. The problem of young people reading well below their grade level increases exponentially when they attend high-poverty schools.

Semaj Brown’s presentation did not disappoint. After receiving a rousing standing ovation, news about her new platform quickly spread across the state of Michigan, with multiple teachers asking to initiate BLACK DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE™ in their classrooms. Within a week, Brown was peppered with additional requests from Colorado, California, and Togo West Africa. It is official, the multimedia platform based upon a singular poem is now international.

“Semaj Brown’s keynote address was a vision. It was one of what education could be-and should be-in a just world that is equitable, diverse, and inclusive. She fused science, art, storytelling, and language into a tapestry for everyone in that room to discover. I think this is what led to her standing ovation: the perfectly articulated, intentional way that Semaj connected with every educator in the space in such a small-time frame.” Carrie Mattern, President-Elect of MCTE, Michigan Council of Teachers of English, Flint Courier News

When asked how she developed the multimedia platform, the award-winning educator and Poet Laureate explained, “Words are the building blocks of language, just as cells are the building blocks of the living. Each word is a world, teaming with synonyms, antonyms, histories, and mysteries, a universe of narratives to be explored. The BLACK DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE™ platform establishes a new way of thinking in education,” states Brown.

With the immediate success of BLACK DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE™, Brown is seeking corporate support, and funding for this innovative platform. To learn more about this new transformative educational tool, BLACK DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE™click this link: https://issuu.com/1plflint/docs/colored_final_booklet_blackdandelion_mcte_color

Featured photo: Director Amevi Ahoucou with students of a school in Togo, West Africa. Students from the school will participate by video in an upcoming local poetry workshop and forum. Photos provided by Semaj Brown

Written

by Tanya

Terry

Semaj Brown, Flint’s inaugural poet laureate, recently talked to the Courier about how her “Black Dandelion” poem and the multimedia platform Black Dandelion: Covergent Voice continue to bring people together while celebrating uniqueness.

Brown, who is also an Academy of American Poets Laureate fellow, is currently engaging with four school classrooms.

“Black Dandelion Convergent Voice originated from PSL / POETRY AS A SECOND LANGUAGE: THE SEMAJIAN METHOD ™, explained Brown. “That is a pedagogy, a method of teaching, that I developed through three decades of being engaged in education.”

Brown has educated in classrooms, in organizations and in institutions. It seems to be in her blood.

“I have always been in some kind of education, and I’ve always used what we call now PSL / Poetry as a Second Language,” Brown stated.

Brown looks at the characteristics of poetry and applies them so one can enhance the experience of reading and writing and amplifying literacy.

All of the work Brown does is integrative. When Brown teaches, no subject is taught by itself. There is instead a melting of science, art, emotional intelligence and cognitive expansion across disparate genres. PSL / POETRY AS A SECOND LANGUAGE: THE SEMAJIAN METHOD ™ is designed to help ensure students understand literacy and words on both a personal and a communal/social level.

One way Brown does this is by creating synonym streams and synonym trees. When exploring words of interest, students also explore other words associated closely with each word’s meaning. This is done intentionally, according to Brown, so a student’s vocabulary starts to expand.

“We’re learning about water at the same time, and we’re learning how trees grow and expand,” said Brown. “If you look at the morphology of a tree, with its branches, you start to associate that with the shape of the lungs.”

There are five different frameworks Brown teaches to educators: topographic viewing, TI SI WI DI BI (think it, see it, say it, write it, do it, be it), morphology of thought, sequential disruption and pattern identification & relation.

Brown talked to the Courier about how one of the frameworks, topographic viewing, can be used to help students better understand the school-to-prison pipeline. The school-to-prison pipeline is the disproportionate tendency of minors and young adults from disadvantaged backgrounds to become incarcerated because of increasingly harsh school and municipal policies.

In topographic viewing, students can better see where they are placed in society so they will be motivated to strive to not become part of an inequitable system.

Brown noted the article “Dandelion Nation” was originally published in the Flint Courier News, which inspired “Black Dandelion.”

“Black Dandelion” was a poem that was sent all over the world to educators, written through the eyes of a young girl living in an inequitable world. Students from diverse backgrounds and different races wrote letters to Brown, telling her they identified with the Black Dandelion.

“That’s why I call it the Covergent Voice….It actually brings people together through the lens of this little Black girl during the Civil Rights Movement.”

Some of the letters written to Brown are published on the Academy of American Poets website, with an explanation of Brown’s program. Brown posted a link to the published letters on social media. This led to requests from California, Colorado and Togo, West Africa from teachers asking to initiate Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice in their classrooms.

Students and educators from Peckham Career Academy, Holmes 3-6 STEM Academy, Greater Heights Academy and Ecole Konoura in Togo, West Africa will soon participate in the Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice Poetry Workshop and Community Forum.

During the Community Wide Convergent Voice workshop, the community can expect to experience three panelists: Dean Withey, Sunanda Samaddar Carrado, PhD and Sonya Pouncy. Withey is the first African American dean in Flint to be dean of a major university. Pouncy is an engineer and will be looking at the engineering aspect of bees, dandelions and structures in society. Carrado, an anthropologist, will look at how women are dandelions.

There will also be table discussion at the event.

It all takes place from 2-4:30 p.m. Saturday, March 18 at the Flint Public Library.

Taking part in the action is Karen Utsey, Growth Opportunity program coordinator with Peckham Career Academy. Utsey explained the poem “Black Dandelion” really hit a chord close to the heart of Peckham students, who had recently lost a classmate due to gun violence. The little girl in the poem talks about how dandelions are her favorite flower, but they are constantly mowed down and viewed as an eyesore. The girl in the poem compares

Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and the boy around the corner who was “mowed down” to dandelions. Utsey said the Peckham students choose to express their interpretation of the poem through painting, which they will share at the upcoming event.

“I always hope for transformation,” said Brown.

Brown is seeking funding for do additional work with students. Currently much of Brown’s work is being funded by Dr. James Brown, MD, Semaj Brown’s husband.

To read more about Black Dandelion: Convergent Voice, click here: https://issuu.com/1plflint/docs/colored_final_booklet_blackdandelion_mcte_color

Poetry Confessions: Teatime with the Poet Laureate

Featured photo: Semaj Brown-photo by Emily O’Boyle

BLACK DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE. BDCV is an international, intergenerational, futuristic platform that utilizes “applied poetry” as an

integrative tool. The platform amplifies literacy capacity, improves skillbased learning and heightens critical thinking, emotional intelligence and cognitive expansion across disparate disciplines of science and art.

BDCV derives from the pedagogy of Poet Laureate Brown, PSL / POETRY AS A SECOND LANGUAGE: THE SEMAJIAN METHOD.

A recent event held at the Flint Public Library, The Community-Wide Convergent Voice Workshop, was inspired by “Black Dandelion.”

The following poems were written by students who participated in the event and/or utilized the BLACK DANDELION: CONVERGENT VOICE platform.

Flint is a Dandelion

Poem by Christian Blake – 6th Grade Greater Heights Academy, Flint

Flint can be a good place

But it can have some people who act really bad

I believe if we work together

We can fix this place up

I don’t like all the destroyed houses and buildings

I want to stop all the killings and fightings

Together we can make it a metropolitan

Flint is a dandelion

We destroy dandelions by cutting them down

But they’re not gone It regrows and rebuilds itself

The seeds work together

The seeds are us

So if we work together

We can do this

Earth’s Dandelions

Poem by Johnice Taylor – 6th Grade Greater Heights Academy, Flint

Nurturing the Earth

Helps us take care of our nature

The more we disregard our actions

The more dandelions, trees, and grass

Grow no more

Miracle Welch, 7th grade, Grand Blanc West Middle School

¨We are Black Dandelions, we Grow the Power of Goodness for Generations into the Future!¨

Black is beautiful.

Black is dark.

Black is scary.

Black is the color you see everyday.

But black can’t be seen.

BLACK IS THE FUTURE!

We know that color of skin doesn’t define us. But it defined those people who were killed. The people who suffered the burn of the bus in May 20, 1961.

The people that made the Future for me AND YOU!

They say that police are supposed to protect and be brave. But were they scared of a Black man walking? Or just shot him down cause the police felt empowered ?

Or told Black women that they can´t be allowed in restaurants, after taking care of white people´s children, and leaving her kids that haven’t eaten in days.

Black is taking for granted.

Black is defined as adsorption of light.

Black can be nice.

Black can be funny.

BLACK CAN BE THE SOLUTION TO EVERYTHING!

But still black is let down into the dark.

The dark is that what you see? Or is it a whole Black family?

Black is being beat and being strung by the neck.

BUT BLACK IS STILL HERE!

¨We are Black Dandelions, we grow the power of Goodness for generations into the Future!¨

Jada Timms, 7th grade. Grand Blanc West middle School

“Perennial Promises Prevailed”

Everyone has a past. But we grow back. We all want to go to BLACK!

But why don’t we go to the past? Do we hope it’s forgotten?

Everyone has had a broken promise. Do we believe in second chances?

Words are more than they seem. People want to put us in our places but… WE RISE.

This short writing means something

more than what it seems.

Poem from Ecole Konoura school

Director /Founder Amevi Ahocou

TOGO, WEST AFRICA

Title: BLACK DANDELION COME HOME TO ME

Black Dandelion come home to me.

Black Dandelion is time Around the conner return to me.

Black Dandelion we shall BE me soon.

Black Dandelion healed my soul in spring.

Black Dandelion catch me.

Black Dandelion I remember you.

BLACK Dandelion I shall love you forever.

Written

A recent local event was inspired by “Black Dandelion,” a poem by Semaj Brown that was sent all over the world to educators and was written through the eyes of

a young girl living in an inequitable world. Community members were so engaged with the workshop they didn’t seem to want to leave!

During the recent CommunityWide Convergent Voice Workshop, girls from Konoura school in Togo, West Africa responded to the poem by acting out the food chain by becoming bees and flowers. In a video presented on the workshop date, the “bees” danced around the flowers, fertilizing them. The students and onlookers, therefore, became more familiar with the ecology of the “Black Dandelion” poem.

“The poem covers not just social problems, but it covers science and art and resilience,” stated Semaj Brown, who wrote “Black Dandelion.”

Boys from the same school performed art, as well as poetry. The poem they recited is titled “Black Dandelion Come Home To Me.” Through the poem, which seemed to have multiple meanings, the students, whose native language is Ewe, were also learning to speak English.

Students from Peckham were grieving the death of a classmate who died because of gun violence in 2023. Peckham students related to the poem “Black Dandelion.” They choose to express themselves through visual art with words from “Black Dandelion” next to the artwork.

Christian Blake, a student Greater Height Academy, recited an amazing poem responding to the “Black Dandelion” poem called “Flint is a Black Dandelion.”

Essays presented by workshop panelists included “On Becoming a Black Dandelion” by Edith Withey, “Equality, Empathy, and Energy in Semaj Brown’s Black Dandelion” by Sonya Marie Pouncy, “Dandelion Garden: A Walk

through Convergent Consciousness” by Sunanda Samaddar, PhD and “Meaning: A Key to a Poem’s Heart.” by Darolyn Williams Brown.

“The power of panelists represented fertile ground where root fibers pierce the heart of imagination,” said Brown, Flint’s poet laureate.

Davina Whitaker spoke about Life Stage One: seed germination, rooting exploration and education.

Whitaker’s words were the perfect way to introduce Brown, who talked about Life Stage Two: Development and Growth. In talking about the evolution and progression of the “Black Dandelion” poem, Brown said it all progressed from an article called “Dandelion Revolution” in the Flint Courier News.

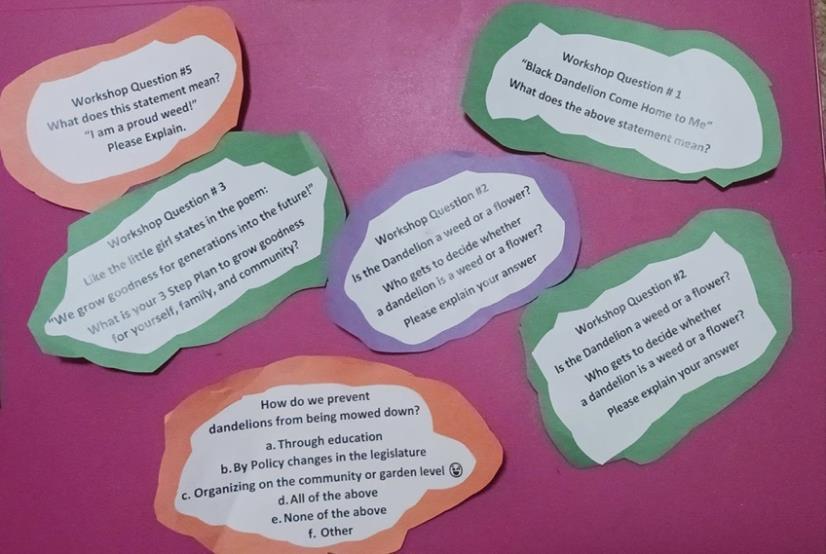

Intimate discussions were held when workshop participants were asked to answer five questions. They were asked what the statement “Black Dandelion Come Home to Me” meant, as well as if the dandelion was a flower or a weed and who gets to decide. They were asked what their three-step plan is to grow goodness in themselves, their families and their communities. Lastly, they were asked how we can prevent dandelions from getting mowed down and what the statement “I am a proud weed” means.

Elner Taylor said because of the impact she felt occurred due to the event “her heart was on fire.”

Flint resident Janet Cameron said she had no words or perhaps not the right ones to describe the “powerful” and “beautiful” event, which took place March 18 at the Flint Public Library. Cameron referred to Brown as a “force” that “is radiated to, used by and inspires others to ‘rise up.’”

-Semaj Brown

BROWN Flint, Michigan's Inaugural Poet Laureate Academy of American Poets Poets Laureate Fellow, 2021 CONTACT AND CONNECT

EMAIL: submit@blackdandelion.org

WEBSITE: www.semajbrown.com

BLACK DANDELION PAGE : www.semajbrown.com/ black-dandelion/ poets.org/poet/semaj-brown