CAse stuDy: CLusius GARDen

Delft Lectures on Architectural Design and Research Methods

Marten Kuijpers

Casper van Duuren

Peng Lee

Yasemin Parlar

Leticija Aleksandra Petrova

Diana Della Pietra

Oliwia Agata Tatara

ReSeARCh meThodS InTRoduCTIon

9 The CLuSIuS GARden: A LIneAR hISToRy

First layout of the garden 17th century's addition: The Ambulacrum

Acquisition of new plants and expansion of the garden

New classification system during the 18th century

The introduction of the glasshouses

Reconstruction and the naming issue in the 20th century 21st century

34 eCoLoGICAL enTAnGLemenTS: A non LIneAR hISToRy

Methodology: tulip as a tool

A definition of Ecology

The Broken Tulip's journey Humans as pollinators Garden as carpet, tulip as ornament

65 RefLeCTIonS

69 RefeRenCeS

72 ImAGe RefeRenCeS

The essay is an attempt to critically position ourselves towards the linear and non-linear temporalities behind man-made, domesticated nature, taking the Clusius Garden in Leiden as a case study.

The first section of the essay introduces the Clusius Garden changes throughout time, from its introduction in the University of Leiden's empty plot until its current form as an ex-situ ecological conservation garden as well as an educational and research facility in the wider context of the Botanical Garden.

Following what can be considered a "linear history", is the analysis of the other temporalities behind the garden, made of hidden links and entangled relationships between biological phenomena, economic processes and cutural developments, the latter finding their direct expression in the architectural evolution of the garden.

The conclusions will examine the results of the research, highlighting multiple links across events and disciplines that have emerged throughout the discussion, presenting a method to study and present Ecological entanglements to engage in multi-disciplinary debates.

Research methods

Field research and analysis of primary sources, the latter being mainly constituted by Clusius’s extensive body of letters and own publications, allowed us to compare the garden today with the original one dating back to the 16th century. It also revealed the opinions, knowledge and attitude of the people who were directly involved in the making of the garden. Finally, secondary sources such as books, leaflets, articles, and other types of literature allowed us to find how different parties viewed similar events, how the chronological history is currently told, and how different explanations can be given to the entanglements that appear in the Clusius Garden and beyond it.

Another valuable research tool has been the "Timelined Map", which has been a valid method of both chronologically and geographically ordering the history of the garden and discover subtle relationships between seemingly unrelated events.

Drawing from Elaine Gan's research and representation methods,1 the map is both a research tool and a means of communicating the methodology and its findings. In the West of the Netherlands, in the heart of one of the oldest Dutch cities,

1 Gan, E., Rice Assemblages and Time, Available at https://elainegan.com

[ mage 0.1.1]

(left) Timelined Map as a research tool revealing Ecological entanglements, see appendix for full sized map

Leiden, a small, mysterious garden is hidden behind the walls of the university. When our research group first went there on a visit, we found the garden much smaller than we envisioned. It didn’t take much longer to realize how misjudged our impression was. Each element of the garden revealed fragments of histories, none of its elements appeared accidentally. In the Hortus there is no such thing as one style, one ideology, one way of creating a garden and one function of the garden, you just keep wondering who designed each part of the space, who brought the plants and who uses them now. It was never intended to be just a herb garden behind the University building, and “oh” it is so much more...

"here in this garden, nature, art and science joined forces"

(Aben, R., de Wit, S., 1999)

The idea of the garden dates back to the 16th century. At that time it

[ mage 0.1.2]

(previous

was very popular for European Universities to develop different facilities such as libraries, anatomical theaters, and special medical gardens that could help students examine nature in different fields. The 16th century was also the period of first long voyages to America, South Africa, and the East. Plant lovers collected and examined species coming from different parts of the world to have a better understanding of the diversity of different regions.

In 1587 following universities of Padua, Florence, Bologna, and Leipzig, The University of Leiden consisting of four faculties at that time (Theology, Law, Medicine, and Liberal Arts), asked the city council to establish the garden in the empty land behind the university to create more possibilities for students to study morphology and structure of medicinal plants. The garden was first laid out in 1594. From copper engravings dated 16102 we can learn that the garden was not the only new facility in The University of Leiden. From now on students could also use the new library and the anatomical theatre. All of the new facilities were closely linked to each other; the anatomical theater was used to show human diseases which were further discussed in the garden in terms of the healing effects of plants. New facilities weren’t exclusively accessible to students though. The anatomical demonstrations, plants grown in the garden, and books stored in the library were all accessible to the general public and not just to the members of the university.

1. A chronological history of the Clusius Garden[ mage 1.1.1] (left) University library Leiden, 1610, Courtesy of Wikipedia [ mage 1.1.2] (right) Anatomical theatre Leiden, 1610, Courtesy of Wikipedia

1.1 first layout of the garden

When the land behind the University was ready to be cultivated, the biggest challenge was to find the Praefectus Horti (director of the garden). “The first concern was to find someone who knew a lot about plants, and who could also contribute a plant collection.”3 The position was offered to the most famous botanist of the time - Carolus Clusius - who arrived in Leiden in 1593, and whose sculptural tribute is still visible in the garden today (see Image 1.1.3). Before coming to Leiden, Clusius had sent to the university more than 268 plant seeds, bulbs and tubers that he had collected throughout the years. The first layout of the garden was made by Clusius and a pharmacist, Dirk Ougaertszoon Cluyt, coming from Delft who was appointed Hortulanus (the curator and the right hand of the director). Cluyt had a great knowledge of medicinal plants and he brought his own collection of crops to grow them in the newly established garden.

The first detailed drawing of the plan of the garden can be found in a manuscript titled Index Stirpium, still present in the archives of the university. This document presented not only the layout of the garden but a handwritten list of the plants that were grown in the garden. The first page of the catalogue shows a schematic rectangular plan of its layout. “The garden was rectangular: 39.90 m long and 30.90 m wide. The length : width ratio was thus 4 : 3, one of the classical harmonic ratios of the Italian Renaissance.”4 The garden layout was designed by two main axes. The north-south axis parallel to the canals and the east-west axis that is aimed at the center of the city. The garden was divided into four parts, so-called quadraes, that were represented four continents - Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. These four squares were surrounded by small stripes enclosing the whole garden. The division was then repeated within each of the quadraes onto another four parts creating smaller areaes. The small stripes made it easy to grow and classify the plants. These stripes contained the actual lands for the plants, the so-called areolae, each of them containing 18, 26, or 32 single garden beds.

The garden’s first spatial arrangements were developed by three scholars working in three different fields. Physician and anatomist Pieter Pauw (who also settled the anatomy theatre at University of Leiden), botanist Carolus Clusius and pharmacist Dirck Ougaertszoon Cluyt.

Clusius (see Image 1.1.6) first studied law and then continued with medicine, furthermore, this switch allowed him to discover his true passion: botany. He travelled throughout Europe and lived and worked in many different places, therefore, he managed to build up a large network of acquaintances, to exchange ideas, information as well as botanical materials. Through international contacts he is the root of many networks of flower enthusiasts and by starting collaboration between different groups of people such as artists, businessmen, and collectors he created an essential connection between systematic botanical inquiry, colonial exploration, and wealth accumulation. These links that combine social, scientific, and economic aspects developed the foundation of the early Dutch horticulture.

Cluyt, also known as Theodor Clutium, was the right-hand man of Clusius as well as the first Hortulanus of the Hortus and he had a large garden and an apothecary’s shop in Delft called ‘In de Granaetappel’ (In the Pomegranate). Cluyt was appointed as a hortulanus on one condition - that he would bring with him his plant collection. Cluyt and Clusius already had contact before and corresponded with each other as plantlovers. The work by Cluyt in 1597, Van de Bijen (About Bees), which was the first book about beekeeping written in Dutch, reveals the cooperation between the two; this book was written in the form of a dialogue between Cluyt and Clusius. (see Image 1.1.7).

Pauw (see Image 1.1.8) was responsible for the construction and planting the first seeds before Clusius arrived in Leiden. Clusius wasn’t really involved in the work of the garden himself, but he had a great network and knowledge about plants and classification methods. Cluyt had a lot of experience and practical knowledge in how to take care of the plants, especially herbs. “These three men put plants in different parts of the garden, and with these plants, they also left their personal traces.”5

[Image 1.1.6] (from top to bottom)

Engraving of Carolus Clusius, courtesy of clusiusstichting.nl

[

mage 1.1.7]

Scan from the manuscript by Cluyt and Clusius, Van De Byen, courtesy of catawiki.nl

[

mage 1.1.8]

Pieter Pauw, courtesy of Wikipedia.org

The inventory with a spatial plan featuring all plants that were originally planted in the garden juxtaposed with numerous letter correspondences can give us a better understanding of what were the intentions behind each of the authors’ ideas of plant distribution. The first seeds that Clusius sent to Leiden before his arrival were planted by Pauw and are all catalogued in area 12 of quadra tertia with appendix cretica (originating from Crete). Pauw probably didn’t have enough knowledge of how the plants will look after they bloom so he simply decided that he will classify them alphabetically by name. This method was quite popular at that time in Europe as many of exotic species were not yet well recognized.

Clusius was most probably in charge of quadra prima, which features plants from his private collections. He introduced a new method - same genus per one stripe. Second principle was to plant beautiful flowering plants on the longer side of each bed. “...[The] catalogue shows that three different flowers were planted on the small edge of the garden bed in a rhythm similar to A-B-C-B-A. They bloomed in March, April and May, and therefore showed blossoms during a quarter of the year. Similar patterns can also be found in adjoining stripes so that this colourful arrangement was repeated alongside the pathways.”6 Clusius linked different stripes together, thinking of the whole quadra as rhythmic changes of different appearances in flowering. Quadra secunda and quadra quarta were most probably assembled by Cluyt, again with systematic order of one genus per stripe. The script reveals names of popular, practical plants that were used by pharmacists at that time.

[image 1.1.9]

6 Gregory Grämiger (2016), Reconstructing Order: The Spatial Arrangements of Plants in the Hortus Botanicus of Leiden University in Its First Years, from book : Knowledge and the Sciences in the Early Modern Period, 243

[image 1.1.10] Hortus Botanicus in Leiden, 1610, Available at https://www.sutori.com/story/ hortus-botanicus-leiden-vHS2N9Qhudh4Jx4d6Q1821BR

In 1601 the first catalogue7 including a drawing of the garden and current inventory of the plants was published. The catalogue was edited by Pieter Pauw, who became a prefect at that time after the death of Cluyt. The new drawing presented in the catalogue shows that some simplification was made (Quadra A (1) and D (4) featured 4 by 4 stripes with 16 beds each, Quadra B (2) and C (3) 4 by 3 stripes with 24 plots each). The simplification was reasoned by Pauw’s methodology of teaching. In the catalogue, he mentioned that during the lecture students should examine one bed or stripe, therefore some of the beds were dedicated only to poisonous plants or sets of plants with similar healing powers. For example, those that would be able to dissolve kidney and bladder stones. Same stones that Pauw could present during his necropsy classes in the theatre of anatomy.

[image 1.1.11]

(top) own drawing, diagram of the layout of the garden from 1601, showing changes of the beds arrangment

1.2 17th century's addition: The ambulacrum

In the beginning of 17th century classifications changed multiple times, additional pages in catalogues introduced plants that were never found there before. New plants arrived in the garden day by day, filling free spots. New categories and classifications appeared, for example “[edible] plants and vegetables, which can be mashed,”8 plants with similar morphological aspects, leaves, smells, or taste. No longer were the plants only a source for remedies or food. The plants themselves became interesting and an individual topic of research. With this new approach, the field of botany was slowly established. New species from all around the world arrived in the garden and new categories and classifications were introduced, overtaking systematic orders established by Pauw, Cluyt, and Clusius, changing the arrangement of quadras and beds to an extent.

In 1600 on the south side of the garden an Ambulacrum was built to protect plants during the winter. The gallery was also used by professors for botany lectures and it housed a large collection of medical and physical objects, some of which was a turtle shell, the jaw of a polar bear from Nova Zembla, two small crocodiles (most likely Indonesian monitor lizards), a globefish, a piece of coral, a bay tree, a large crocodile, a swordfish, and a flying fox or Kalong from the East Indies. The garden as well as the ‘gallery of nature’, became places where art and science were brought together. Sculptures and objects were exhibited for the public's learning.

8 Gregory Grämiger (2016), Reconstructing Order: The Spatial Arrangements of Plants in the Hortus Botanicus of Leiden University in Its First Years, from book : Knowledge and the Sciences in the Early Modern Period, 247

[image 1.2.1]

(left) own drawing, diagram of the timeline, 17th century

[image 1.2.2]

(right) own drawing, isometric showing new additions in 17th century - Ambulacurum and the fence for tulips

Fence for tulips

Agave americana

Semper Augustus

1.3 Acquisition of new plants and expansion of the garden

During the 18th and 19th century the plant collection grew enormously, in the 18th century 3000 species were listed in the catalogue “Florae Leydensis Prodromus” written by Adriaan van Royen (prefect of the Hortus between 1730-1754) and further in the 1851 catalogue 5100 species can be found, as well as the Royal Dutch society for the promotion of horticulture founded by Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold enabled the import of as many exotic plants as possible into the Netherlands, especially from Japan. Due to this massive growth of the number of the plants an expansion of the garden was necessary.

Adriaan van Royen (prefect 17301754), had major success when it came to expansion: firstly, the grounds were extended over the canal to the west in 1736, and, secondly, a new stone-built Orangery was constructed. Thirdly, in this period a semicircular pond was also dug, a widening of the canal that transects the Hortus.

1744

statues from the Van Papenbroek collection

[ mage 1.3.1]

own drawing, legend of the timeline of Hortus Botanicus

Leiden : 17th century

[ mage 1.3.2]

(right) own drawing, isometric showing addition of an ambulacrum due to half-hardy plants

1600

1.4 New classification system during the 18th century

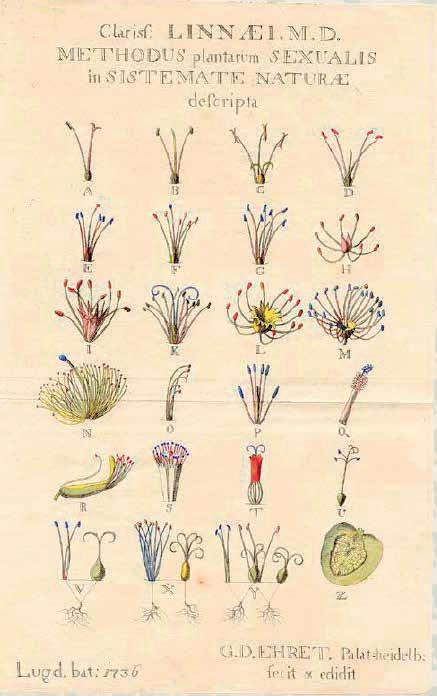

In 1735 Carl Linnaeus visited Leiden to meet the doctor Herman Boerhaave, but he also spoke to Adriaan van Royen. Carl Linnaeus became famous for classifying the plant kingdom on the basis of the number and position of their stamens and pistils, in other words, characteristics of their flowers. While he was staying in the Netherlands, from 1735 to 1738, he published his Systema Naturae, which was expanded further in 1753 in the Species Plantarum, the basis for plant nomenclature. Within this system each species was given just two names: a genus name and a species name. In the past, species of a certain genus were described with the whole sentence, for example Chaerophyllum temulum perenne cicutae folio. This can be translated as: "the perennial rough chervil with leaves similar to rowan". Chaerophyllum means the genus, and the rest of the phrase describes the species within that genus.

When designing the Clusius Garden and while writing his catalogue Florae Leydensis Prodromus, Adriaan Van Royen (prefect of the Hortus 1730-1754) made partial use of Linnaeus’ system, but also presented his own ideas.

The original 'empty plaetse' behind the Academy Building had been changed beyond "recognition by hundreds of years of construction activity and the presence of a gigantic brown beech from 1819."9 It is unknown what were the specific reasons for certain changes in the garden during the 18th and 19th centuries, however, the driving force to expand, build a series of glasshouses, and change the land of the garden was the massive addition of the new plant species.

[image 1.4.1]

Linnaeus’ System, drawn by Ehret in 1736, Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Stockholm, courtesy of Wikipedia

1.5 The introduction of the glasshouses

During the second part of the 19th century a lot of plants that were not hardy were brought to the Hortus, therefore a series of glasshouses were added: in 1856 a large cast-iron glasshouse, in 1861 an orchid house, in 1871 the new Victoria glasshouse, in 1877 a tree fern house, in 1878 a palm-house, in 1883 a series of nursery glasshouses, and in 1887 a smaller glasshouse for the cactus collection.

1887

1 1856 - a large cast-iron glasshouse

2 1861 - an orchid house

3 1871 - the new Victoria Glasshouse

[ mage 1.5.1]

(left) own drawing, legend of the Timeline of Hortus Botanicus Leiden : 18th and 19th century

[ mage 1.5.2]

(right) own drawing, isometric showing addition of glasshouses and English landscape style garden

1744

Orangery

4 1877 - a tree fern house

5 1878 - a palm-house

6 1887 - cactus house

statues from the Van Papenbroek collection

1.6 Reconstruction and the naming issue in the 20th century

In 1931 Prof. L.G.M. Baas Becking (prefect), together with H. Veendorp (hortulanus), dug into the history and made the first attempt to reconstruct the Clusius Garden using the Index Stirpium of 1594. They wrote a book: Hortus Academicus Lugduno Batavus 1587 – 1937. Research shows that a few details in this book are untrue, such as that the Hortus was not actually founded until 1590, however, it was beautifully published in facsimile in 1990 to mark the 400th anniversary of the Hortus.

The biggest challenge to reconstruct the garden was that Index Stripium covered “pre-Linnaean” names of plants, so it took much longer then expected to match the original names with the ones used at that time. After a long period of investigations the garden in its one third original size was reconstructed with an incomplete list of plants next to the old Collegium Theologicum. Not only the plants, but also some of the elements didn’t correspond with the ideas of first authors such as shell paths. After 55 years of its existence, the reconstructed garden lost some of its species that were overtaken by their stronger neighbours.

Baas Becking is the best known after his hypothesis: “Everything is everywhere, but the environment selects... [the] application of this hypothesis to microorganisms, specifically to the dependence of their geographic distribution over the earth on their metabolic properties, formed the basis of Baas Becking's research program at the Hortus Botanicus Leiden.”10

10 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lourens_

20th century

Reconstruction

[image 1.6.1]

(left) own drawing, diagram of the timeline, 20th century [image 1.6.2]

(right) own drawing, isometric showing addition of one tropical house, systematic garden, The Von Siebold Memorial garden, Clusius garden relocation

1 1938 - one single complex of tropical glasshouses

2 - Rosarium, a Herb Garden and a Systematic Garden

1990 - The Von Siebold Memorial Garden

1993 - Fern garden

Clusius garden located outside of Hortus

1887

1 1856 - a large cast-iron glasshouse

2 1861 - an orchid house

3 1871 - the new Victoria Glasshouse

4 1877 - a tree fern house

5 1878 - a palm-house

6 1887 - cactus house

The subject of recreating the Clusius garden was tackled again 1990, when two new sources of ‘evidence’ were rediscovered in the Jagiellon library of the University of Krakow in Poland (see Image 1.6.4). One of them was the collection of watercolors of plants, commissioned by Clusius' close friend Charles of Saint Omer. After his death, the collection travelled along Europe. Via Brandenburg it ended up in a library in Berlin, as a form of fifteen bound books (Libri Picturati). To protect against war violence, the collection was housed in a monastery in Grüssau (Krzeszów). After the Second World War it was located on Polish territory and the collection was placed in the university library of Krakow, the Biblioteka Jagiellonska.

Index Scriptum was a starting point again, only this time apart from written word also watercolors could be examined. The beautiful images revealed not only details and colors of the plants but also names of that time. Second source was the herbarium of the Leiden pharmacist Antoni Gaymans. “The dried material could be identified so that the old names could be linked to real plants.” 11

It was not until 2009 when the garden was brought back to its original location. Several decades before, a venerable beech tree, which had occupied the original garden that fronted the Academy building, died and thereby made accessible for restoration the plot of ground where Clusius, Cluyt and Pauw planted their first plant collections. The date was also the commemoration of the quatercentenary of the death of Clusius. Only about 70% of species were still available, since the 16th century some of them have already disappeared and had to be resembled by newer forms. A number of wild species were difficult to come by, e.g. the plants from Crete such as, primroses, columbines, peonies, roses, and bulbs. Not only the plants, but also other elements of the garden that we can admire today were reconstructed - its original layout, the fence for the tulips, and the symbolic pavilion representing the center of the world

A question arises why the garden was reconstructed ? Why is there a need of bringing its atmosphere back to life?

The history of Clusius Garden may be understood as one of the elements of the medical curriculum introduced in the 16th century as a practical tool to examine nature. It can also be seen as a way of understanding different methodologies and how botany was approached by different authors and their ideas of ordering the flora. We may also see it as an image of human desires, fascinations and sociocultural changes. The garden disappeared and was brought back behind the walls of the University. Will this living picture of history ever be finished ?

To give it even a better understanding it is important to mention that not only the garden but also the anatomical theatre was reconstructed in Museum Boerhaave in Leiden. The reconstruction at Rijksmuseum Boerhaave is based on manuscripts and prints from the Leiden anatomical theatre from 1610.

11 http://www.clusiusstichting.nl/index.php/clusiustuin/

1.7 21st century

To celebrate the turn of the millennium, a new glasshouse was opened called the Winter Garden, to facilitate half-hardy plants and introduce a new entrance, the Hortus shop, the Grand Café Clusius and a meeting room, called the Garden Room. A renovation of the Orangery and the tropical glasshouses was sustainably led. Furthermore in 2005 a new Systematic Garden was opened, in order to display the plants according to the newest scientific classification. In 2009 the reconstruction of the 1594 Clusius Garden took place and it was laid back in the original site. In 2011 the area around the Observatory was returned to the original location in the Hortus. Finally, the newest addition is the Chinese Herb Garden, strengthening the connection and focus on Asian plants.

Overall, even though everything seems to be digitised and available through different databases during the last decade, living collections are still of high importance not only for the visitors and their experience, but also for taxonomic research, research into plant composition, and for DNA research. However, the digitalisation and several technical aids are becoming increasingly important in taking care of the garden, therefore, fewer people are necessary.

21st century

1 2000 - Winter Garden; (the Hortus shop, the Grand Café Clusius and a Garden Room)

2 2009 - the reconstruction of the 1594 Clusius Garden

3 2011 - Observatory,

[image 1.7.1]

(left) own drawing, legend of the Timeline of Hortus Botanicus Leiden : 21st century

[image 1.7.2]

(right) own drawing, isometric showing addition of of Winter garden, reconstruction of Clusius garden, observatory, and Chinese Herb Garden

4 Chinese Herb Garden 1

20th century

Reconstruction

1 1938 - one single complex of tropical glasshouses

2 - Rosarium, a Herb Garden and a Systematic Garden

3 1990 - The Von Siebold Memorial Garden

4 1993 - Fern garden

5 Clusius garden located outside of Hortus

The catalogue of the plants by Pauw from 1601 reveals one plant, which significantly contributed to the imbalance of a simple, rather restrictive layout of the hortus. Due to this one plant, perception of the garden as one species per bed or rhythms of flowering plants was no longer essential. Clusius was the one responsible for that inconvenience. Of all the species that he brought with him to Leiden, he was very proud of the exotic, rare and very expensive plant that he introduced in Europe to later became one of the most admired species in the seventeenth century: the tulip.

Clusius wanted each of the visitors to admire it as a first sight entering the garden. The catalogue shows that tulips were planted all along the main axis, in the center of attraction. It is not documented that any species had received that much space or recognition from any of the garden's authors before. Introducing tulip as a dominant element of the garden appeared to be so successful that it resulted in theft of tulips. Bringing this new, exotic rare plant into the garden resulted in the creation of a new architectural element - a fence that protected the tulips from stealing.

[ mage 1.7.3]

(left) own drawing, legend of the Timeline of Hortus Botanicus Leiden : 16th century

[ mage 1.7.4]

Garden

" The hortus conclusus is a veritable stage where "the immeasurable wealth of relationships between things" is enacted."

Gerrit Komrij, 1991

" I have applied my mind to the observation of exotic plants and other things that are brought from foreign parts. Now I have taken on the task of writing the history of all the exotic things that I have acquired in recent years, and that through great efforts I have been able to obtain ".

(Clusius, Exoticorum libri (Antwerp, 1605), quoted by Ogilvie (2006, p. 257).

2. The entangled temporalities behind the Clusius Garden

2.1 Methodology: Tulip as a tool

In the attempt to map the multiplicity of agents behind the Clusius Garden, changing the scale of the observation from the Garden as a whole to only one of its flowers, was a method to depart from an Ego-centric in favour of an Eco-centric approach, and distill its Ecological value.

"To expose the layered condition of the landscape, we need only take one layer, the landscape as it is today, and distill it from a fragment. This allows us to visualize the process of change in the landscape as a whole."12

The "fragment" in the garden is found in the Semper Augustus tulip, which becomes a lens through which multiple Ecological entanglements start to emerge. If the history of the garden until the 21st century has been told linearly and objectively, the following section dwells on the non-chronological events that have directly or indirectly shaped the garden, or have in turn been a result of its transformations.

The physical scale of the tulip allows us to simultaneously expand and narrow down the focus of the study. One the one hand it extends the boundary of the geographical area under consideration all the way to the Ottoman Empire, following its origins before coming to the Netherlands. On the other hand, it allows to focus "at the most minuscule level,"13 to use Guattari's words, thus finding out agents of change which a mere architectural analysis would exclude.

The choice to focus on such a small scale is also related to the fact Carolus Clusius's main research interest was placed on the individual plants and their aesthetic qualities as well as their growing conditions, rather than on the garden as a whole, as a close analysis of his correspondance with Matteo Caccini reveals.14 This tendency, coupled with the study of plants for their own sake and not in association to their medicinal value to human advantage, is what determines the start of botany, which finds in the cultivation and dissemination of the tulip its most widely recognised reference. We therefore chose to employ the tulip to reveal the untold; however, the plant is seen only as a tool and any plant can be chosen, with the awareness that the chosen plant has an influence on the perspective of the story that is told.

[Image

More specifically, we chose a tulip that cannot be seen anymore in the garden - the Byzantine tulip “Semper Augustus” that comes from the Ottoman Empire and was one of the most expensive and rare tulips during Clusius time and throughout the first half of the 17th century. This tulip is all the more relevant to a discussion around temporalities as it is now extinct due to its biological weakness, therefore highlighting the transformative and constantly changing nature of the Garden alongside the plant species it hosts.

As this tulip does not exist anymore, chronological history would end its story, however, our story unravels what an extinct species that cost more than a person's salary15 can reveal to us about its journey and entanglements. Therefore, whenever the word “Tulip ” is used throughout the essay we refer to the forever lost Semper Augustus.

2.2 A definition of Ecology

In an attempt to define the ecological value of the Clusius Garden and Botanical Gardens in general, one may refer to these words written by Clusius 400 years ago, and gifted to us through his extensive correspondence.

[The Tulips were very dry, therefore I don’t think they will manage to survive, nonetheless I have put them in the ground, in the hope that if the smallest spark of life is left with them, it may preserve.]16

fragment 435, my trans)

This extract (see Image 2.2.1), taken from Clusius' writing to his Italian friend Matteo Caccini, supports a definition of Ecology as found in Guattari's The Three Ecologies.17 Within this framework, the purpose of this chapter is to reveal the multiplicity of Ecological influences and implications manifested in the architecture of the enclosed space of the Garden and the global sensibility which extends beyond its walls. Therefore, whenever the word Ecology is used, it entails the multiple layers of biological, social, and cultural processes and most importantly the relationship between them.

After a brief illustration of the Tulip's journey from the Ottoman Empire all the way to Leiden, the focus is placed on the mutual influence between biological and economic processes behind the renown Tulipmania, which followed the Tulip's arrival to the Netherlands.

Lastly, the third section will describe the cultural influences that the Tulip has brought with its journey from the Eastern to the Western world, that are manifested in the architectural arrangement of the garden.

The conclusion of the essay suggests a new method to enquire Ecological entanglements of man-made nature, as a way to show, in Guattari’s words, that “Now more than ever, nature can not be separated from culture.”18

16 Clusius, C., Letter from Clusius to Caccini, M., (1607), Available at https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/1589510

15

17 Guattari, F., (2000), The three Ecologies,

18 Guattari, F., (2000), pg. 42

2.3 The Broken Tulip's journey

“Among other sundry seeds, Clusius arrived in Leiden with a suitcase full of Tulip bulbs, which at that point represented one of the most extensive European collections of this flower of rapidly rising popularity.”19

Tulip entered the Netherlands through the humanist, physician, and botanist Carolus Clusius, who is therefore often referred to as the "father of the Tulip."20 However, its most widely accepted journey to the Clusius Garden starts in the East, and more specifically in Istanbul, at the time Constantinople,21 amongst flourishing intersecting water courses and secret gardens. Here, the son of a Flemish lord, Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq, was sent as an ambassador of the Holy Roman Emperor in November 1554.22

Reading his diaries, we are able to understand that through his position at court of Sulieman the Magnificent he was able to send Tulips to Europe as early as 157323 and receive bulbs and seeds from Constantinople even after his return to Vienna.24 It is precisely in Vienna that his life intersects with that of the other protagonist of the Tulip's journey, Carolus Clusius, present at court of Maximilian II as the Emperor's advisor for the court's botanical garden.25 Through his connection with de Busbecq and other influencial representatives of the Austrian-Viennese elite, including women such as Anna Maria von Heusenstain, Anna Aicholtz and Eva Ungnadin,26 Carolus Clusius was able to obtain the rare Byzantine bulbs that he would bring with him in 1594, in his journey to Leiden.27

Not only is he credited for physically bringing the Tulip bulbs from Austria to The Netherlands, but also for having the required expertise to systematically catalogue its multiple type variations into a rationally ordered system.28 Inspired by the Tulip, Clusius attributed to the their aesthetic appeal an important value independent of, or in addition to, its already understood medicinal purposes.

“This man established a link between science and aesthetics in the new field of botany”29

Although Clusius wasn’t the first person to give such high value to Tulips in the United Provinces—“from the sixteenth century, especially in the south, people had begun to cultivate Tulips— he was the best qualified to describe and catalogue them through careful attention, systematic reflection, and scientific reasoning.”30

19 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014). The making of Dutch flower culture: Auctions, networks, and aesthetics., p.69

20 Dash, M. (2010) Tulipomania: The Story of the World's Most Coveted Flower & the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused

21 Dash, M. (2010)

22 T. Forster, C., Blackburne, D., (2007) The Life and Letters of Ogier Ghiselin De Busbecq

23 Dash, M. (2010)

24 T. Forster, C., Blackburne, D. (2007)

25,25 Egmond, F. (2010), The world of Carolus Clusius: natural history in the making, 1550-1610

27 Clusius, C., Rariorum Plantarum Historia (published by Bot. Garden in 1893)

28 Dash, M. (2010)

29,29 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014)., pg 69

2.4 Humans as pollinators

Whilst the flowers themselves are obviously not accessible to us anymore, and some of them are actually extinct, for reasons that this research will unveil, thanks to the “testament” of Clusius’ letters, collected in the digital archive by the University of Leiden,31 we are able to dissect their journey and their relations with the Clusius Garden and understand how the actors behind the gardens have acted as “pollinators” just like the wind or other organisms would do, displacing seeds from one place to another.

"[I have already written to have sent the drawings of your Green Tulips with their bulbs in the small box, but of the third I took out of my small garden did not do a portrait, because I thought the bulb would be enough, and it can give proof that it has made a very beautiful flower, but it did not make seeds, so since only have this one of this colour I have wanted to send it to you and leave it as a testament]"32

(Fragment 446, own trans.)

Like this fragment, many others suggest the extensive network of people behind Renaissance gardens, of which Clusius Garden is definitely a pivotal example, that played an important role in shaping their own respective "hortus botanicus", but also, indirectly, their correspondent's ones, through the act of exchanging seeds and bulbs. Behind this occupation, was a scientific - and certainly economic - interest and it is possible to argue that the Garden acted as a live experiment for Clusius, a place to physically store the seeds but also as a research tool, whose findings he would afterwards share in his letters and publications. In fact, many fragments from his letters refer to a “trial and error” mechanism to find out about the Tulips and other flowers specific planting and blooming time, like it is shown in this fragment to Matteo Caccini (See Image 2.4.1):

"[I have experimented many times that even if [the plants] are dry, they will nonetheless bloom, even though they have been off the ground for 12 months]"33

(Fragment 437, own trans.)

[image 2.4.1] (left) Screenshot from Clusius letters’ digital Archive, courtesy of Universiteitleiden.nl

31 Clusius Correspondence, Letters from and to Carolus Clusius (1526-1609), Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/collection/ublclusius

32 Clusius Correspondence, Letters from and to Carolus Clusius (1526-1609), Retrieved from https://clusiuscorrespondence.huygens.knaw.nl/edition/entry/446

33 Clusius Correspondence, Letters from and to Carolus Clusius (1526-1609), Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/1589503

[image 2.4.2] (above) Tulipae Byzantinae genus alterum as represented in Rariorum Plantarum Historia

Like any other experiment, the task is paved with uncertainty, as we can read from his own words.

"[Regarding the green Tulips {..} to plant it in the ground is a very uncertain task, because its offsets very rarely produce flowers of the same colours as their ‘mother’.]"34 (Fragment 436, own trans.)

Not only the inclement weather conditions and the specific blooming and planting time affected his garden, as he often declares in his letters, but also other apparently inexplicable factors that years later would be solved by molecular plant virology. In fact, unlike other flower enthusiasts, whom Clusius himself criticises because they are “only interested in beautiful flowers,”35 with his research on Tulips, Clusius was also trying to find the solution to a mysterious phenomenon, that of "tulip breaking", which a few decades after his death would have led to the Tulipmania.

Praised as a rare aesthetic trait by conoisseurs and enthusiasts, the agent that determined flowers to display the colourful patterns, actually caused the Tulips affected by it to be smaller and less resilient to the weather in comparison to their monochromatic types.36 This discoloration was actually the result of a virus, now known as the Tulip breaking virus (TBV)37 which Clusius had already understood as an anomaly.

We have proof of his awareness from an analysis of some of his letters38 and his manuscript Rariorum Plantarum Historia, “History of rare plants,”39 which both address this specific unusual discoloration, referred to as a genus alterum meaning "different gene". (See Image 2.4.2)

Thanks to one of his letters in which he mentions these specific strands,40 we are able to locate Clusius’ own descriptions of this different Byzantine Tulip amongst the 732 page manuscript, which would otherwise be inaccessible for its extents. In the section dedicated to the Tulip, the differently coloured flower appears in its full name: Tulipae Byzantinae genus alterum (see Image 2.4.2). This reference, in which Clusius declares to have seen such a Tulip finally bloom in April in his garden in 1588 (MDXXCVIII),41 attests that the Semper Augustus's bulb was brought to The Netherlands already in its multi-patterned version. (See Image 2.4.3)

The conclusion of this study leads us to confirm that when the garden was founded in 1594, it is very likely that Tulips were already there and the adjective “Byzantinae”, from Byzantium, further validates the earlier illustrated version according to which Tulips came to Clusius’ hands through Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq.42 In this light, de Busbecq can therefore be considered the earliest “pollinator” of our story.

After their arrival to the Netherlands, the aesthetic appeal of the variegated Tulips made them the most valuable,43 compensating for their biological weakness and reduced resilience,44 and this would cause their “unnatural” spread by traders and enthusiasts during and after Clusius' life. Between 1634 and 1637 the demand for Tulip flowers made them a valuable commodity and their uncontrolled value rise45 caused one of the earliest historical financial bubbles, known as Tulipmania.

(See Image 2.4.4-5)

[image 2.4.3] (right) Screenshot from Clusius's text annotations in Rariorum Plantarum Historia, in which Clusius describes the origin of the Byzantine Tulip and refers to the year in which it was brought to him (1588). Available at https://www.rct.uk/collection/1057452/

rariorum-plantarum-historia-carolusclusius

34 Clusius Correspondence, Letters from and to Carolus Clusius (1526-1609), Retrieved from https://clusiuscorrespondence.huygens.knaw.nl/edition/entry/436

35 Clusius, C., Letter from Clusius to Caccini, M., (1608), Available at https://clusiuscorrespondence.huygens.knaw.nl/edition/entry/437

36 van Dijk, W., trans., (1951) A treatise on tulips by Carolus Clusius of Arras p. 18

37 A. Lesnaw, J., A. Ghabrial, S. Tulip Breaking: Past, Present, and Future available at https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.10.1052

37,38 Clusius, C., Rariorum Plantarum Historia, published by the Bot. Garden in 1893

40 Clusius, C., Letter from Clusius to Caccini, M., (1608), Available at https://clusiuscorrespondence.huygens.knaw.nl/edition/entry/437

41 Clusius, C., Rariorum Plantarum Historia, published by the Bot. Garden in 1893

41,43 Dash, M. (2010)

44 van Slogteren, E., and De Bruyn Oubter, M. P. 1941. Onderzoekingen over viruszieken in bloembolgewassen. II. Tulpen I. Meded. Landbouwhogesch. Wageningen 45:1-54.

45 Blunt, W. (1950) Tulipomania. Penguin Books LImited, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

[image 2.4.4] (above) Value of goods equal to the price of the rare tulip Semper Augustus, as recorded in a pamphlet written in 1636 Available at https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1094/ PDIS.2000.84.10.1052

[image 2.4.5] (left) Graph of the Tulip price rising over time between the years 1634-1637, until its economic crash. Available at https://amsterdamtulipmuseumonline.com/pages/part-4-tulip-mania

Jan Brueghel the Younger gives us a satiric impression of Tulipmania in his painting (See Image 2.4.6) and by looking closely, one can recognise the Tulip under discussion which went extinct soon after, precisely because of its biological weakness. Interestingly, in this painting humans become monkeys, who are actually natural pollinators, thus reinforcing the point we are making that humans inevitably act as agents of change in the natural environment and are so entangled with it that it becomes impossible to discuss biological events without relating it to human economic activity and vice-versa.

Through the Tulipmania we have a written record of the entanglements between economic and natural temporalities: Tulip bulbs take a year to bloom into flowers, whilst seeds can take up to seven years; however, we have records of traders exchanging and signing contracts up until 10 times in a day.46 This means that in January, whilst bulbs were still growing in the ground, speculation was being made over their size and weight, which would affect their price, much before they would bloom in April. Flowers were bought and sold way before they came into being at a speed which would eventually prove dangerous for the traders themselves, like the economic crash proved soon after, between January and February 1637. (See Image 2.4.7

With a closer analysis, this historical event can be further explained through what can be defined as a de-coupling of two temporalities; that of the Tulip growing and sprouting times throughout a calendar year and that of the human act of trading. Records have in fact attested that if originally only physical bulbs were traded, following their price increase a "promissory note" was introduced in their place, allowing for the bulbs to be bought and sold when they were still in the ground.47 If before the advent of promissory notes contracts could only be signed off in the trading season, between June and September, when bulbs could be dried off and preserved above the ground, afterwards the physical bulbs became unnecessary to complete transactions and therefore the trading season was extended to the whole year, independently from the natural Tulips growing and sprouting time.48

This last reflection can be instrumental to problematise the phenomenon of the Tulipmania in relation to Clusius Garden, to which it is often associated. Although the work of Clusius in the Garden has certainly contributed to the initial dissemination of an aesthetic value of Tulips through his enthusiastic literary production and active experimentation in the garden, the decoupling of the economic and the biological temporality distances Tulipmania from the very essence of the Clusius Garden as well as from Clusius's Ecological sensibility. As his letters demonstrate, the temporality of the Tulip and its bulbs growing, sprouting and blooming across the calendar year, is clearly understood by Clusius, whose awareness of the Tulip temporality is immediately reflected in his classification method and the architecture of his quadra of the garden, whose beds are arranged according to the plant blooming time. (See Image 2.4.9 next page)

46 Dowd, B., 2016 Tulipmania: when tulips cost as much as houses 47,47 E. McClure, J., C. Thomas, D., (2017) Explaining the timing of tulipmania's boom and bust: historical context, sequestred capital and market signals, Retrieved from https:// www-cambridge-org.tudelft.idm.oclc.org/core/journals/financial-history-review/article/ explaining-the-timing-of-tulipmanias-boom-and-bust-historical-context-sequestered-capital-and-market-signals/20BEB345A7BB4BF2E84C07F9077361A1/core-reader

"All these fools want is tulip bulbs Heads and hearts have but one wish Let’s try and eat them; it will make us laugh

To taste how bitter is that dish."

(Hondius, 1621)

[image 2.4.8] (left), own drawing showing coupled and decoupled temporalities compared to the

[image 2.4.9] (above), own drawing showing Clusius quadra, in which plants are arranged according to their blooming time

2.5 The Tulip Breaking virus: a lesson on interdependencies

One may still wonder what happened to the Semper Augustus tulip after Tulipmania's burst. After February 1637, the price of the Tulip eventually came back to normal49 and Dutch economy was not substantially affected.50 However, the drastic reduction of human dissemination combined with its biological weakness eventually lead the Semper Augustus tulip to its extinction.51

Its mystery nevertheless, continued to remain unresolved until well into the twentieth century, when the experiments of Cayley and of McKay52 demonstrated that the transmissibility was caused by a virus, more specifically identified by Dekker et al as the Tulip Breaking Virus (TBV),53 a filamentous potyvirus whose natural hosts have found to be Tulipa and Lilium. Furthermore, the staff at the John Innes Horticultural Institution in London was able to show that the virus responsible for the discoloration was transmitted by aphids. By allowing aphids to feed alternatively on broken bulbs and non affected breeders, they noticed that the bulbs aphids were able to feed on broke twice as often as the control sample, thereby demonstrating that aphids were responsible for the transmission of the virus from a tulip to another.54

They also found that the potyvirus could affect a planted flower as well as a bulb that was stored off the ground prior to planting.55 from which we can derive that not only Clusius with his activity, but also the exhange of bulbs in the early stage of Tulipmania has in fact intensified the spread of the virus. This discovery once again reinforces the idea that at the time, not only aphids, but also humans, have acted as pollinators, contributing to complete the triangle of interdependencies. (See Image 2.4.10)

This conclusion is all the more valuable for Ecological approaches, when taking into account the fact that such a system of relationships does not exist in a vacuum, but rather in a constantly changing environment. This is shaped by parameters, such humidity and temperature, which have in turn an effect on the system, an example of which is the fact that the rising of temperatures causes aphids to proliferate much faster, thus determining a greater spread of the infected plants.56 The Ecological value of Clusius Garden, embedded in its original arrangement and in the "testament" of its early agents, is therefore still present today, as it enables the study and in the most fortunate cases the understanding of these complex and entangled relationships.

18, 19 E.

51,51 A. Lesnaw, J., A.

54,54 Dash, M. (1999)

56 Hulle, M. et al, (2010) Aphids in the face of global changes

[image 2.6.1] (right) Painting referred to in below quote. Painting of Battle of Chaldiran at the central audience hall of Chehel Sotoun palace, Courtesy of Wikipedia

" On the folding doors of one of these palaces I saw a picture of the famous battle between Selim and Ismael, King of the Persians, executed in masterly style, in tesselated work. I saw also a great many pleasure-grounds belonging to the Sultan, situated in the most charming valleys. Their loveliness was almost entirely the work of nature; to art they owed little to nothing. What a fairyland! What a landscape for waking a poet's fancy!"

(Forster, T., Blackburne, D., (2007) The Life and Letters of Ogier Ghiselin De Busbecq.)

2.6 Garden as Carpet, Tulip as Ornament

In an effort to unravel the Ecological values that shaped Clusius Garden, within and beyond its enclosed walls, we have thus far focused on the human activities that have changed the natural environment, but also shown how these in turn, shape society. As mentioned before, the entanglements between human activity and biological events are intertwined and cannot be discussed without the other. In this section, we flip the lens in order to understand how nature influences human perception, and in turn how human perception manifests itself as man-made nature. In order to understand these multiple layers of influences, we will go back in time to take a journey with the Tulip as it travels from one place to the next carrying with it values from the former. These Ecological values that the Tulip carries then illustrate themselves in man-made nature such as the Garden.

The garden, as Foucault describes it, “is the smallest parcel of the world [and it is] the totality of the world,”57 therefore we can determine that Clusius Garden is a Heterotopia that contains a world within a world, a “real space meant to be a microcosm of different environments.”58 Within its enclosed walls, Clusius Garden contains information about Ecological values that spread globally, and as a result can be used to understand its international influences. The heterotopic nature of the Garden will be used to reveal values that have informed the transformation of garden typologies over time and the entanglement of these values reflected in visual and literary forms of representation. With this new focus of man-made nature, we will assume “the garden is a [carpet] onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection,”59 and the Tulip is an “ornament” that carries the changing values with it as it travels from one place to another.

57 Foucault, M., & Miskowiec, J. (1986). Of other spaces. diacritics, 16(1), 22-27, p.26

58 Sudradjat, I. (2012). Foucault, the other spaces, and human behaviour. ProcediaSocial and Behavioral Sciences, 36, 28-34, p.31

59 Foucault, M., & Miskowiec, J. (1986), p.26

Below, an extract from a letter from De Busbecq to Clusius describes the journey of the Tulip from its origins in Turkey and the ornamental and aesthetic values it carried along with it into Europe.

"As we passed through this district [on the road from Adrianople to Constantinople] we everywhere came across quantities of flowers—narcissi, hyacinths, and tulipans, as the Turks call them. We were surprised to find them flowering in mid-winter, scarcely a favourable season....The tulip has little or no scent, but it is admired for its beauty and the variety of its colours. The Turks are very fond of flowers, and, though they are otherwise anything but extravagant, they do not hesitate to pay several aspres for a fine blossom. These flowers, although they were gifts, cost me a good deal; for had always to pay several aspres in return for them." (Fifty such Turkish coins, says Busbecq, were equal to a crown.)

Busbecq, Turkish Letters (I, pp.24-25)60

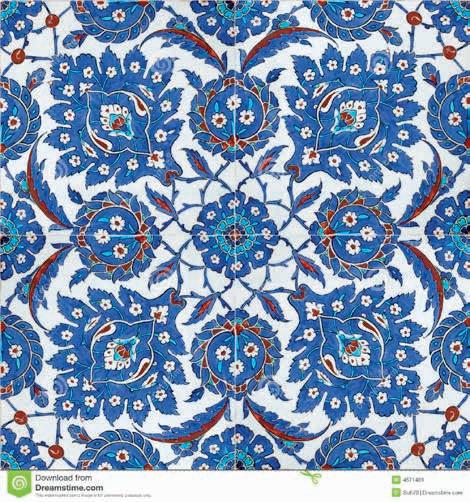

Foucault’s definition of heterotopia comes from medicine “where it refers to the displacement of an organ or part of the body from its normal position.”61 In this sense, as a travelling seed, the Tulip itself is a heterotopia, a displaced organ that contains a world within its world. In his letter, De Busbecq refers to the flower as tulipan which is actually the Persian term for turban in which the Turks would often place tulips as ornament.62 The Turkish name for the flower is however lale, which can be seen in the names of Turkish places such as Laleli and Laleli Geçidi (Place of the Tulips and Tulip Pass),63 the historical time period of Lale Devri (The Tulip Era in the Ottoman Empire), and is also referenced in Clusius’ classification, when he refers to the Byzantine Tulip as “Lalẻ di duoi fiori” (see Image 2.6.3).

Referred to as the Flower of God, Tulips were an important religious and ornamental motif in Ottoman culture. Tulip motifs and symbolism can be seen in numerous forms of art, pottery, architecture, fashion and other forms of visual, and also literary, expression. The Tulip was a symbol of the divine, or devotion and modesty before God, because “[when] in full bloom, it bows its head.”64 We can see (see Image 2.6.4) that the Ottoman depictions show long slender Tulips with pointed petals that reach towards the sky, or heavens, and are often bent at the top of the stem with the crown bowing out of respect.

The name lale, entering into the Turkish language from Persian origins, actually comes from the same roots as the Arabic word Allah, meaning God.65

“Of all the blooms in a Muslim garden, the tulip was regarded as the holiest,”66 and thus, the divine, heavenly symbol of the Tulip surpassed the Turks’ aesthetic appreciation of it. For this reason, the Tulip was not modified for domestic cultivation until after it arrived in the Netherlands.67 The mistranslation of the word lale as tulip, a word based on the aesthetic value of the flower rather than the heavenly appreciation of it, can perhaps be used as a clue to understand the change in perception of the flower in Europe, specifically the Netherlands, and how this shift manifested in man-made nature.

Along its journey from Iran to Turkey to Europe, the Tulip carried with it this heavenly value and symbolism of the divine. Although botany was still regarded as an educational or medicinal field in the Netherlands at the time, one of the earliest representations of the Tulip in the genre of emblem books - an emblem contains three elements: the motto, the illustration, and the poem which explains the motto and illustration68 - depicts the Tulip as a divine figure (see Image 2.6.4). The emblem illustrates three Tulips, two of which are reaching for the sky and one with its bloom bowing towards the ground. A strong shadow below the Tulips suggests sun shining down on them, perhaps a heavenly light. “The title reads: ‘Languesco sole latente’ or ‘I wilt (or fade) when the sun is hidden,’”69 but here the ‘sun’ can be interpreted as God, and alludes to the flower’s devotion to the heavens. This first representation of the Tulip with the symbolism of divine rather than aesthetic value is quite interesting when we look at the original placement of the Tulips in Clusius Garden. Adopting the organization of the Persian gardens, the Tulips were placed along the central main axis, giving them more importance and dominance over all other plants in the garden (see Image 2.6.4).

60 De Busbecq, O. (n.d.). Manuscript, Turkish Letters (I, pp.24-25), University of Chicago. Retrieved from http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_Romana/ aconite/busbecq.html

61 Sudradjat, I. (2012), p.29

62 De Busbecq, O. (n.d.).

63 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014). The making of Dutch flower culture: Auctions, networks, and aesthetics.

64 Dash, M. (2011). Tulipomania: The story of the world's most coveted flower and the extraordinary passions it aroused. Hachette UK, p.10

65 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014)

66 Dash, M. (2011), p.10

67 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014)

68 Alciati, A. (2004). A book of emblems: the Emblematum liber in Latin and English. McFarland.

69 Campbell, E. A. (2019). Tulip symbolism in the seventeenth-century Dutch emblem book (Master's thesis), p.42

Despite this idiosyncratic hierarchy of the Tulip in the first arrangement of the flower, as a botanical garden, Clusius Garden was firstly established as an educational archive for botany and not a place to showcase the beauty of plants. As mentioned in earlier sections of this essay, in the 16th century, gardens served more practical needs such as medicinal or educational purposes,70 therefore they were typically small and surrounded by architecture, hedges, or other types of framing enclosures, ensuring that the line of vision always remained within the walls of the garden. There were no clear hierarchies and main axes, but rather geometric meandering paths that slowed down the movement of the visitor. This slow paced movement allowed for the visitor to focus on each individual plant rather than the garden itself.

These gardens were not places where plants were to be marveled at from afar, but instead learn from the plants and study their details. As Janick describes it, the botanical and the Renaissance gardens (see Image 2.6.5) were formal gardens where the systematic organization of plants created an “artificial environment using plants as structural material… [representing] human dominance over nature.”71 These formal gardens were organized with practical sensibilities of nature and therefore the study of the plants were emphasized over the aesthetic qualities of them. This practical conception of plants is visible in the various botanical prints by Georg Dionysius Ehret, and many others, (see Image 2.6.5) where the plants are represented in great detail and carefully annotated.

As natural history and botany became a leading trend in the academic field of science, there was an emergence of scientific accuracy in the representation of plants and nature.72 The early classifications and arrangements of Clusius Garden described at the start of this essay, and shown in Image 2.6.5, proves how the value of knowledge and systematic categorization of botany in the late 16th and early 17th centuries manifested in man-made nature in the form of the Garden.

70 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014)

71 Janick, J. (2014). Chapter 36 Horticulture and Art. In G. R. Dixon & D. E. Aldous (Authors), Horticulture: Plants for People and Places, Volume 3 Social Horticulture (pp. 1197-1223). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, p.1199

72 Pavord, A. (2019). The Tulip: The Story of a Flower That Has Made Men Mad. Bloomsbury Publishing.

[image

For image references see Table of Figures section

Although, a closer look at the Garden with the special care given to the Tulip, first placed along the central axis (atypical for formal gardens at the time), and then later placed in their own beds surrounded by a fence to protect them from theft, can reveal the heterotopic tendencies within the small enclosed space. While appearing to be a simple rectilinear garden used for educational purposes, Clusius Garden contains an entanglement of social and economical values within the fences of the Tulip beds. Clusius’ deep knowledge of the nature of the flower and his arrangement of the Garden according to rhythmic blooming of flowers during different seasons was a catalyst for the appreciation of the beauty of the flower rather than the practicalities.

The Tulip was the first flower in the Netherlands to be cultivated for its aesthetics, and the scientific knowledge acquired by Clusius and his network was used to manipulate the flower to obtain certain aesthetic qualities such as variances in colour, shape, and size.73 This new aesthetic value of the flower led to rapid trading and collecting of bulbs, which in turn led to the exponential rise of the price and ultimately what is known as Tulipmania described in the previous sections of this essay. The Tulip, therefore, holds many intertwined values of culture, beauty, and economy, while reinforcing distinctions of class and taste. In this sense, we can confirm that the Tulip is a heterotopia of its own, containing scientific ideas about the cultivation of the flower, but also values of “aesthetics, class sensibility, and monetary worth.”74

This new appreciation of the beauty of the flower initiated a new form of Dutch painting called still life, coming from the Italian Natura Morta, that used mainly the flower as its subject.75 During this time, in the mid-17th century, the economical and social implications of Tulipmania, and also the black plague, led to “an increased skepticism towards earthly existence and this skepticism is present in the symbolic vanitas still lifes of the time,”76 and, thus, Tulips become a symbol of temporality. While we can clearly see the ephemeral symbolism of flowers in still life paintings such as A Vanitas Still Life with a Skull, a Book, and Roses by Jan Davidsz de Heem (1629) (see Image 2.6.6), we can also see these values reflected in the transforming architecture of the Garden.

With the acceptance of Tulip as ornament and a new appreciation for the flower’s aesthetic value, the formal garden typology of the botanical and Renaissance gardens started to change. The skepticism towards earthly existence, along with the new found beauty of the flower, brought back symbols of the divine and translated in garden architecture as a heavenly place for pleasure and reflecting on one-self. In the 17th century when Pleasure Gardens emerged, there was a desire to create “a sort of paradise on earth” where liefhebbers “referred to the garden as a paradisus oculorum, a paradise for the eyes.”77

73 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014)

74 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014), p.62

75 Janick, J. (2014)

76 Pavord, A. (2019), p. 145

77 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014), p. 19

For image references see Table of Figures section

[image 2.6.6] (next spread) Own collage showing "Tulip as Ornament"

For image references see Table of Figures section

Using the Tulip as a lens here we can determine that this idea of the garden as paradise also originates from Iran where “paradise is a synonym for the Garden of Eden [and the etymology] leads back to the Persian, where paradise was a walled-in compound with a garden (from ‘pairi’, around, and ‘daeza’ or ‘diz’, meaning wall, brick, or shape).”

its symbolism from its origins, but adapts to its environment and in turn influences it. The value of the Tulip affects the human relation to the flower, the human interactions modify the value of the flower, and these values are all reflected in the architectural transformation of the enclosed space of the Garden. Clusius Garden was no longer just a space for education, but rather a Pleasure Garden that showcased the beautiful and vast collection of plants that were acquired by its curators and allowed visitors to marvel at their beauty (see

The diagram in the previous spread reveals the early values brought into Europe from the Middle East along with the Tulip. With its beauty the Tulip, symbol of the divine, also carried the idea of paradise on earth. As we saw in the first arrangement of Tulips in Clusius Garden, Early Italian, and then the Dutch Classical gardens, adopted the qualities of the Persian Bagh gardens which had an emphasis on a main axis of vision that was framed by a line of flower beds, typically the Tulip. Water, a naturally cold and wet element, was seen as existing between earth and atmosphere,79 and so a fountain of some sorts would always be centrally located to clean and cool the air that blew over it towards the palace.80 These winds would cleanse the garden and its architecture to transform the space into a paradise. The Italian garden, which strongly influenced the Classical Dutch Garden, is characterized by strong symmetry, proportion, and harmony.81 The extensions to Clusius Garden in the 18th century show strong influences of the Pleasure Garden typology (see Image 2.6.6), especially with the use of the transecting canal and semi-circular pond that divides the sections of the Garden. With paradise being defined as a garden with a walled-in enclosure, the Garden is still enclosed by tree-lined canals, therefore the lines of vision remain contained within the garden boundaries.

Img.2 Still-Life with a Skull, a Book and Roses

Influenced by Italian Natura Morta Dutch still-life paintings, or Vanitas often depict flowers. This painting shows empherality by picturing flowers (alive), bones (dead), and a book (eternal) together.

Fig.2 Renaissance Italian Garden with central water fountain, use of symmetry and proportion, views directed inward

78 Gebhardt, A. C. (2014), p.19

79 Bauman, J. (2002). Tradition and transformation: the pleasure garden in Piero de Crescenzi’s: Liber ruralium commodorum. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 22(2).

80 Atasoy, N. (2020). Introduction to the Catalogue of Ottoman Gardens.

81 Oldenburger-Ebbers, CS, Backer, AM, & Blok, E. (1996). Guide to Dutch garden and landscape architecture. East and Central part: Gelderland and Utrecht The Hef.

[image 2.6.7] (next spread) Own collage showing "Tulip Brings Back Nature"

For image references see Table of Figures section

The enclosed walls of the garden were finally broken in the Baroque gardens, influenced by the French Jardin á la Française (see Image 2.6.7). Just as the Tulip became associated with class due to the economical implications of Tulipmania, the Pleasure Garden was also for the upper class and were often in the yards of wealthy regents82 or in palaces. The garden’s architecture reflected this monetary power, and so the enclosing boundary was removed to extend the vision beyond its perimeter. As a formal garden, there is still a strong central main axis, and highly ornamented subdivisions. This garden typology is about vistas and is meant to be experienced from one point looking out at nature, which now finally becomes something to be marveled at.83

As the garden expanded and the enclosures were removed, formal gardens of the past were left behind to adopt more naturalist ideas in “an attempt to live with rather than dominate nature.”84 Instead of systematically arranging plants for practical or aesthetic purposes as in past garden typologies, naturalism emphasized the free form and embraced nature as it is.85 The influences of Ottoman palace gardens on Dutch garden typology can be seen in the late 18th century when early landscape gardening started in The Netherlands. Ottoman palace gardens, unlike Persian palace gardens, are not orderly and symmetrical following certain rules. The Ottomans conception of gardens was that they were part of nature, therefore they only embraced and emphasized what was already there. For example, these gardens would be built near natural running water rather than constructing a fountain.86 Nature was dominant over man-made nature.

This may be another reason why the Tulip was never manipulated for its aesthetics in Turkey, but always left natural. Influenced by the Ottoman garden, early Dutch landscape gardening broke free of the strict rules and artificiality of the Baroque garden, which we can clearly see in the 19 Hortus Botanicus and also in the appreciation of nature represented in 17 landscape paintings (see extended views without enclosing boundaries, architecture dispersed throughout the landscape rather than used as a framing structure, and the use of the canal as a natural boundary to the Garden are all naturalistic values that we can see in Ottoman gardens. With extensive global commercial trade happening at the time, the Garden was now housing plants from other parts of the world such as Asia and tropical regions. New plants from around the globe were introduced to the Garden along with values that they would bring with them. New Tulip cultivars were introduced through cross-breeding, a carpet that allowed for multiple cultures and values to take play in one space.

Garden walls are finally broken to step away from formalism - gardens are now about vistas

The study of the transformation of these garden typologies through the lens of the Tulip as an ornament that changed human perception of botany as is moved in space, begins to unravel and make sense of some of the Ecological entanglements that helped shape Clusius Garden and Hortus Botanicus Leiden. With its entry into the Netherlands, the ornamental Tulip shakes up the accepted values of botany, igniting a series of transformations to the man-made natures that take both the architecture of the garden, but also the representation in the arts from formalism to naturalism. Here we can go back to the notion of garden as “carpet” and assume Hortus Botanicus as a patchwork of heterotopic carpets that contain symbols of Ecological values from around the world. It is clear to see that over time the additions to the Garden transformed from a formal enclosed garden to a more naturalistic garden that promoted vistas and emphasized nature over the people.

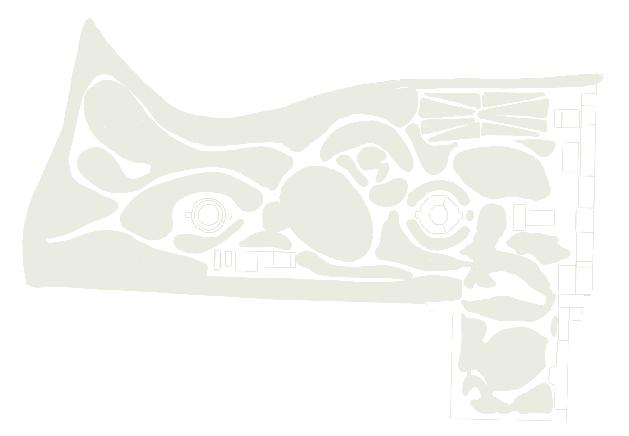

[image 3.1.1] (above) Own diagram Extract from Timelined Map showing links between the people in Clusius' network, the architectural organization of the Garden, and the mutual exchange of knowledge with the Tulip as a starting point.

Reflections

Following the Semper Augustus Tulip on its journey to the Clusius Garden has enabled us to witness the variety of processes and interdependencies it has directly or indirectly generated. Not one but multiple temporalities have been found and overlayed, to discover relationships between a Garden and its agents of change throughout time.

These agents of change did not follow one another linearly, as the Entangled representations have attempted to illustrate, rather they established mutual influences in which in most cases it becomes difficult to distiguish between cause and consequence. With insight, this was reflected in the collective research process and in the structure of the essay; rather than analysing the history of the Garden in a merely chronological order, assigning each researcher to a specific period of time, we decided to focus on its "layers" instead, and on the links between them. The former can be referred to, with a certain degree of reductionism, as the categories of people, plants, and culture.

These, and more importantly, the relationships between them become bearers of new and multiple histories that are influenced by the lens of the research, which for the purpose of this essay has been the Semper Augustus Tulip. Despite illustrating different aspects, the different sections all converge in showing the multiple agents of change behind the Garden and - if analysed collectively - new entanglements start to arise.

For this reason, during the research process and throughout the production of the essay, a "Timelined Map" was used to both inform the research and to notice different links between the layers that have been laid out against a temporal and spatial context. Far from attempting to exhaust all possible relationships in a permanent framework, the map has to be taken as a constantly evolving tool and as a plea to problematize Ecological phenomena and their temporalities through a multi-disciplinary approach.

The Timelined Map, which was used as an research tool throughout our research for this essay, attempts to organize all of the Ecological entanglements Clusius Garden hides behind its enclosed walls. Here in our reflections, we have decided to include a few extracts from the Timelined Map that highlight the key entanglements that have guided our research. The map in its entirety can be seen in the appendix section of this essay. The Map is organized into columns that contain information from the four layers of analysis we have done, Culture, The People, The Garden, and finally, The Tulip. As mentioned before, The final column of the Tulip can be substituted for another flower, or another lens, which would in turn change the story the entanglements reveal.

" I hope that this history, which have written with great faith and the greatest diligence, will stimulate young men to take up this study in the same way that my earlier observations led them to the study of other plants. "88

(Carolus Clusius, Exoticorum libri)

(Carolus Clusius, Exoticorum libri)

[image 3.1.2] Own diagram

Extract from Timelined Map showing economical links as a result of Tulipmania, blooming and trading seasons, and thus the Garden arrangement

[image 3.1.3] Own diagram

Extract from Timelined Map showing links between the East and West world, the Tulip's journey, and the symbolizm of Divine carried from one place to the next.

References

Aben, R., de Wit, S. (1999). The Enclosed Garden. History and Development of the Hortus Conclusus and its Reintroduction into the the Present-day Urban Landscape. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers

Alciati, A. (2004). A book of emblems: the Emblematum liber in Latin and English. McFarland.

Atasoy, N. (2020). Introduction to the Catalogue of Ottoman Gardens.

Bauman, J. (2002). Tradition and transformation: the pleasure garden in Piero de'Crescenzi's: Liber ruralium commodorum. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 22(2), 99-99.

Blunt, W. (1950) Tulipomania. Penguin Books LImited, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Burnett, C., Kraye, J., & van Miert, D. (2013). Communicating Observations in Early Modern Letters (15001675). London: The Warburg Institute.

Butter, H. “Hortus Botanicus Leiden, The oldest botanical garden in Western Europe “ Retrieved from: https:// www.sutori.com/story/hortus-botanicus-leiden--vHS2N9Qhudh4Jx4d6Q1821BR

Campbell, E. A. (2019). Tulip symbolism in the seventeenth-century Dutch emblem book (Master's thesis)

Clusius correspondence. Available at: https://clusiuscorrespondence.huygens.knaw.nl/

Clusius C., Rarorium plantarum historia (1588). Retrieved from https://www.rct.uk/collection/1057452/ rariorum-plantarum-historia-carolus-clusius

Dash, M. (2011). Tulipomania: The story of the world's most coveted flower and the extraordinary passions it aroused. Hachette UK

De Busbecq, O. (n.d.). Manuscript, Turkish Letters (I, pp.24-25), University of Chicago. Retrieved from http:// penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_Romana/aconite/busbecq.html

Dekker, E. L., Derks, A. F. L. M., Asjes, C. J., Lemmers, M. E. C., Bol, J. F., and Langefeld, S. A. (1993). Characterization of potyviruses from tulip and lily which cause flower- breaking. J. Gen. Virol. 74:881-887.

Dowd, B., 2016 Tulipmania: when tulips cost as much as houses, Retrieved from https://www.focuseconomics.com/blog/tulip-mania-dutch-market-bubble

Egmond, F. (2015) The World of Caorlus Clusius, Natural History in the Making, 1550-1610