SAVAGES AND PRINCESSES:

THE PERSISTENCE OF NATIVE AMERICAN STEREOTYPES

AUGUST 5 - SEPTEMBER 5, 2016

SAVAGES AND PRINCESSES:

THE PERSISTENCE OF NATIVE AMERICAN STEREOTYPES

AUGUST 5 - SEPTEMBER 25, 2016

THIS EXHIBITION WAS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY A GRANT FROM: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS:

MARCUS AMERMAN (Choctaw), Stites, Idaho, from Duncan

MATTHEW BEARDEN (Citizen Potawatomi-Kickapoo-Blackfeet-Lakota), Tulsa

HEIDI BIGKNIFE (Shawnee Tribe), Tulsa

MEL CORNSHUCKER (United Keetoowah Band), Tulsa

TOM FARRIS (Otoe-Missouria-Cherokee), Norman

ANITA FIELDS (Osage-Muscogee), Stillwater

KENNY GLASS (Wyandotte), Tahlequah

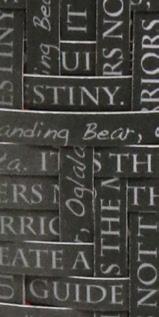

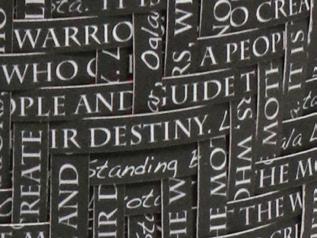

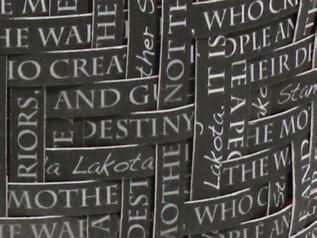

SHAN GOSHORN (Eastern Band Cherokee), Tulsa

BENJAMIN HARJO, JR. (Absentee Shawnee-Seminole), Oklahoma City

APRIL HOLDER (Sac & Fox-Wichita-Tonkawa), Shawnee

JUANITA PAHDOPONY (Comanche), Lawton

K.H. POOLE (Caddo-Delaware), Oklahoma City

ZACHARY PRESLEY (Chickasaw), Durant

HOKA SKENANDORE (Oneida-Oglala Lakota-Luiseño), Shawnee

KARIN WALKINGSTICK (Cherokee Nation), Claremore

MICAH WESLEY (Muscogee-Kiowa), Norman

KATHY MCRUIZ, Executive Director

108|Contemporary is honored to show the works of 16 contemporary Native Oklahoma artists in the exhibition Savages and Princesses: The Persistence of Native American Stereotypes. Oklahoma is rich with Native artists who create thoughtful works that draw upon a complex and intertwined history. Their expression speaks to their lived experiences and current events. Savages and Princesses brings this eclectic but powerful mix of artists together to deconstruct stereotypes of Native peoples and to forge a path beyond them.

Curator America Meredith (Cherokee Nation) has crafted an exhibition that is visually and thematically fluid, without being predictable. She allows us to walk seamlessly through the gallery, experiencing each piece individually—and, in the end, understanding how and why it fits within the whole.

108|Contemporary is a nonprofit community arts organization that supports Oklahoma’s contemporary fine craft artists by connecting them to audiences and opportunities though education, recognition, and exhibition programming. We hope you will find the exhibition challenging in a way that leads to better understanding of cultures that are the heart of Oklahoma.

Sincere thanks to our donors who generously support our exhibitions and programs, to our Board of Directors, which is made up of dedicated Tulsans passionate about sharing their love of fine craft with others. And to our staff who—as they have every exhibition and program, put in countless hours of good thought and hard work for this exhibition—thank you.

This exhibition was made possible in part by a grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. We are grateful for their support.

Finally, thank you to our visitors and for all your kind words about the work we do at 108|Contemporary.

AMERICA MEREDITH, Curator

Stereotypes of Native American peoples are ubiquitous and familiar. While all ethnic groups face stereotyping, usually members of the group are able to educate the public and many of these stereotypes are questioned or are falling out of acceptability in the public sphere. Stereotypes are not incidental but instead dominate public discourse about Indigenous peoples; they make their way not only into popular culture but also newspapers and textbooks.

Why are these stereotypes so deeply entrenched? Why, when confronted with new information or meeting actual Native people instead of adjusting stereotypical perceptions to fit reality, does the public often challenge Native people for not conforming to its preconceived notions? These are the questions we explore in the group exhibition Savages and Princesses: The Persistence of Native American Stereotypes.

American society has great difficulty acknowledging its past with Native peoples or allowing them visibility in the present. Angie Debo’s history And Still the Waters Run is still highly controversial in its indictment of Oklahoma’s role in the theft of Indian land. Native Americans share the struggle with all Indigenous peoples for accurate portrayals of themselves in the mainstream media. What has changed in recent decades is the increased access to global communications—from Nativeowned media networks to something as mundane as Facebook. Now Indigenous voices are accessible to anyone willing to listen.

Children under the age of seven have high neural plasticity in their brains; young children are indeed impressible. Information received at this early stage leaves what neurolinguistic researchers call an imprint. Once these imprints are formed, the simple addition of factual information later in life is insufficient to alter an imprint. A strong emotional impact can alter an imprint in an adult; art is the perfect vehicle for this. It can be hard to let go of stereotypes; on their surface, they can be sexy, charming, nostalgic, funny—especially those images created by a multibillion-dollar advertising industry.

The sixteen artists in the show use the unexpected—humor, emotion, or shock— to encourage viewers to question and challenge stereotypes, even unspoken, unacknowledged ones. In the intertribal environment of Oklahoma, artists also challenge stereotypes members of one tribe might hold against another. This exhibition provides an intensive and intimate focus on the underpinnings behind and movement beyond stereotypes.

I am grateful to Kathy McRuiz and Krystle Brewer for affording me the opportunity to curate this exhibition. Thanks also, to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts for its support of this show. Thanks to 108|Contemporary for allowing Indigenous artists to direct our own dialogue about issues that face us.

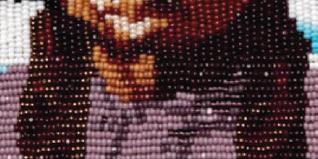

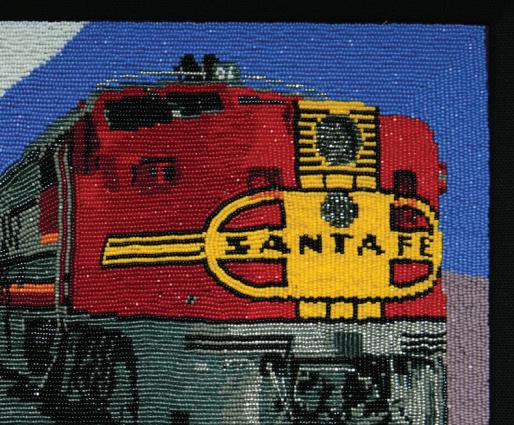

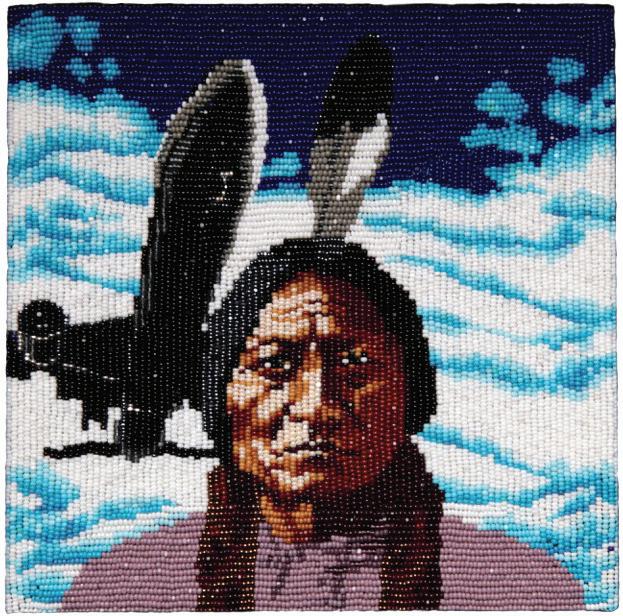

MARCUS AMERMAN, Choctaw

My own personal myth is based on the perspective that “Art is War” and that War (Art) is the proper occupation for one who is inclined towards the survival and betterment of his peoples. In my mind, I am a warrior who is answering a “call to duty,” as I see it offered to me.

Because I am an Indian, I was born a political entity. To not acknowledge this in my life and art would be for me to miss a vital aspect of my origin. I believe that for my art not to become increasingly more political and socially conscious as I live, learn, and create would be an insult to the Native ancestors who lived, fought, and died so that I could be afforded this opportunity of unfettered artistic expression. A failure on my part to not eventually evolve, expand, and extrapolate this perspective to include championing the survival and growth of this planet Earth and all of its inhabitants would be to neglect an essential part of being human in this historic time of great change.

I am aware that this is a war that I wage on myself, within myself, and in solitude. Through my art, I manifest this war as a spectacle for any and all that have the stomach for this type of psychological bloodbath. My theme is that what I “become” is what I contribute to the world “becoming.” The world and I have a relationship. We are catalysts for each other’s evolution.

MATTHEW BEARDEN, Citizen Potawatomi-KickapooBlackfeet-Lakota

What is this obsessive mistress called art that steals one’s heart and harkens back to the Ancient Ones, their call to us, the Un-Ancient Ones, and our struggle to bridge our worlds into this world or some world out there in the great circle of life in this world of worlds...

I’m constantly trying to break out of the molded idea that people have shelved as to what is contemporary Native artwork. The problem with that is that it is often not commercialized enough to get the popular cool gig.

Maybe I should wear a cowboy hat.

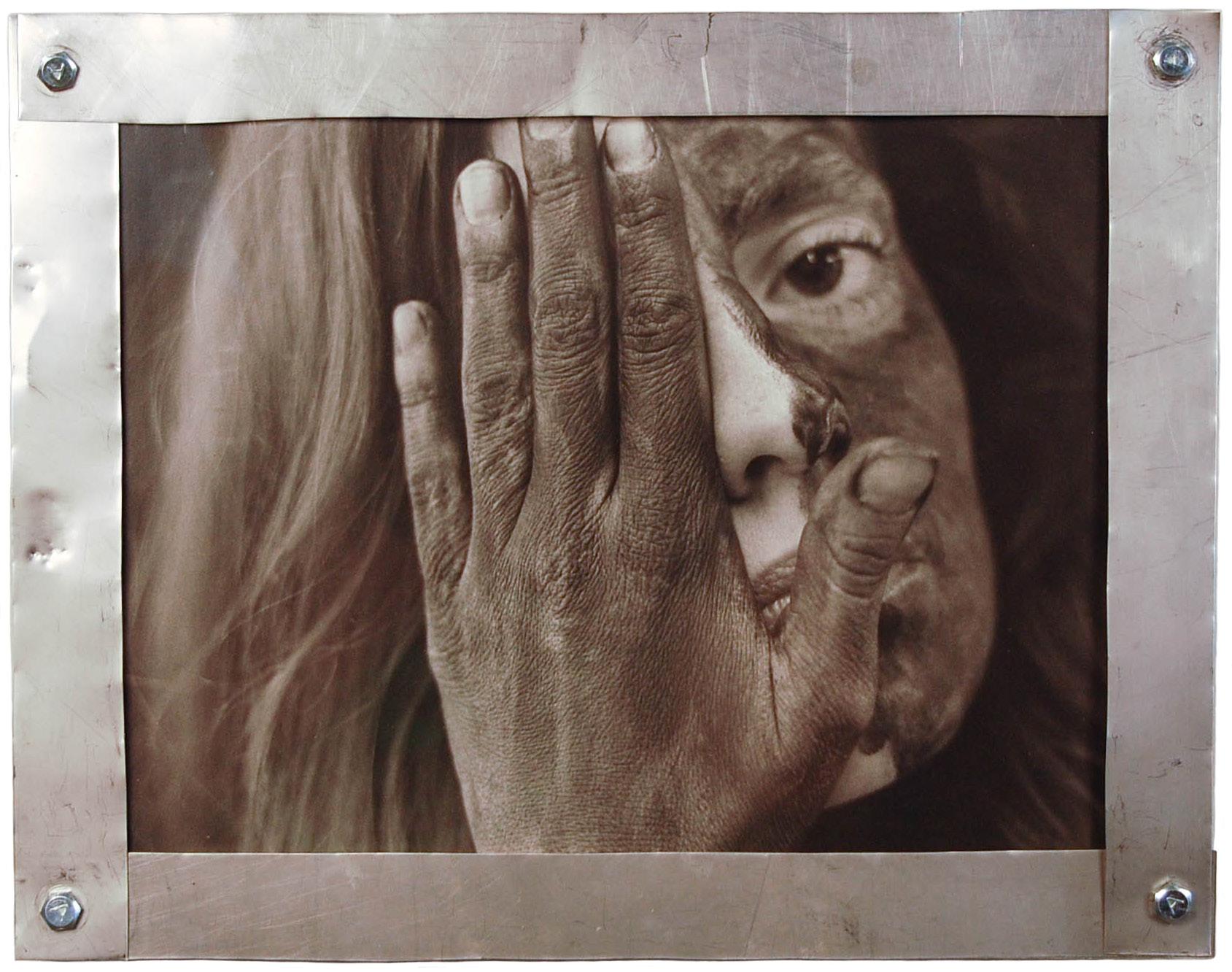

HEIDI BIGKNIFE, Shawnee Tribe

In 2016, when I look out into the meadow that is our ceremonial ground, I see the hair colors of brown, black, blonde, and red, and I know I am with my tribe. In 1990, when I made these portraits, I was a student at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, just coming to know myself as a mixed-race person. Largely raised in EuropeanAmerican culture and with very little tribal contact, I felt both indignant and ignorant, and I was angry. I knew I had my heritage but did not yet understand that I needed to earn recognition of my identity: from my tribe, other Native people, and most of all, from myself.

Native American literature fueled my photography and inspired the series Bloodlines or Belief Systems was born. Previously, I experimented with self-portraiture and painting my own face. While at IAIA, seeking the approval of others and angry that I felt forced to earn it, I coated myself in an expression of mixed-race and wore a dress I had created in Native Fashion class. Through my photos, I insisted that being mixed did not mean I was not Indian.

With maturity and the distance of years, I can now see in these portraits the hurt and sadness behind my rage, the complex bind of descending from persecutor and persecuted, the frustration at the pressure to deny a part of myself in order to be Indian, and the immense pain of insecurity. Today, I have a better understanding of stereotyping within and outside Native communities. Forced for so long to identify ourselves to the outside world, we sometimes assume the stereotypes and patronizing judgments that these stereotypes propagate. At times, I still battle with these false notions, but mostly I stand firm and take heart in my work, both artistic and personal, that has gotten me to a place of Shawnee, a place I know that I belong.

Bloodiness of Belief Systems Quartet, 1 of 4 shown

Black and white photo on Agfa paper, aluminum, plexiglass, acid-free matte board, steel bolts, nuts 11” x 14”

MEL CORNSHUCKER, United Keetoowah Band

The name of this show, Savages and Princesses , brought to mind a comment I’ve heard quite often, “My grandmother was a __(insert tribal name here)__ Princess.” So, for all those folks who want to have an Indian Princess in their bloodline, here is my wooden Indian Princess waving her hand to them as the wind comes sweeping down the plains.

TOM FARRIS, Otoe-Missouria-Cherokee

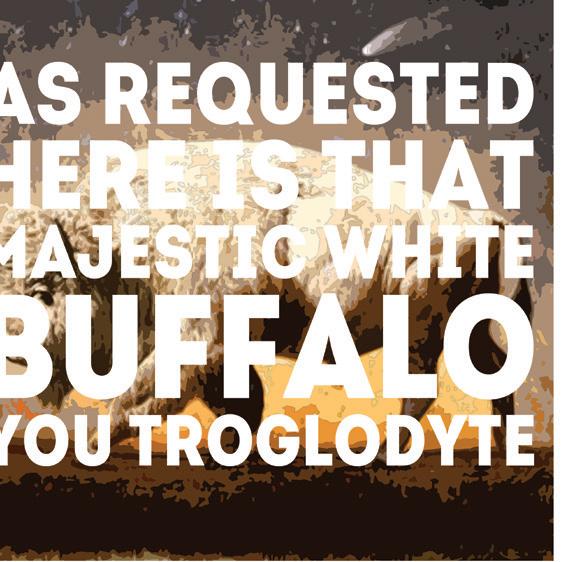

My artwork takes iconography from pop culture and applies a Native perspective to it. In our increasingly globalized society, pop imagery provides a window into the work for audiences that might not be familiar with Otoe, Missouria, or Cherokee issues or worldviews. Through color, humor, and familiar tropes, my artwork can create a cross-cultural dialogue.

Considering Native American stereotypes, I took this opportunity to explore how the outside world mischaracterizes Indians as well as the stereotypes we Native people place on ourselves. One of the pieces I have submitted includes a readymade object—a mass-produced Pontiac hood ornament. Pontiac cars were manufactured by General Motors, headquartered in Detroit, Michigan. The cars were named for a man: Pontiac (ca. 1720–1769), a war chief of the Odawa people whose homelands included parts of Michigan. By adding his image to a ballheaded war club, I am reclaiming his humanity, Indigenous identity, and history that included leading a 1763 siege against Fort Detroit.

All too often, our complex histories as Native people are reduced to advertising logos. I ask viewers to dig a little deeper the next time they see a Native image in pop culture.

ANITA FIELDS, Osage-Muscogee

Sometime during the 1940s my Wah Zha Zhi (Osage) eko (Grandmother), whose first language was Osage, and my aunt Margaret were traveling in Colorado. They were shopping in a store in Colorado Springs when my eko spotted a piece of enamelware, an item frequently used during feasts and ceremonies in our culture then and now. Eko asked my aunt in Osage, “Ha non tze?” (How much is it?) Before my aunt could reply, a salesman says very loudly and close to her face, “It’s a bucket with a lid on it.” Not one to shrug things off, Eko slowly responded in English with deliberate sarcasm, “I know it’s a bucket with a lid on it!”

My eko and aunt achieved great pleasure in the retelling of their experience. We heard this story many times growing up and never failed to laugh—all of us imagining the bizarre scenario, knowing in our hearts it was dismissive and dehumanizing. To some, this story may seem meaningless and inconsequential, but I have always thought of it for what it was: an assault on the integrity and intelligence of my precious eko and aunt. Sadly, and all too often, this incident and others like it, represent experiences that continue to be commonplace and a definitive reality for Native people.

“It’s a Bucket with a Lid on It” Clay, underglaze

KENNY GLASS, Wyandotte-Cherokee

Growing up in a small Cherokee community, it was uncommon to encounter Native people other than Cherokees. Not until my senior year at an all-Indian school was I exposed to other tribes and their cultures. After high school, I was involved in Native American programs on my college campus. I began to hear jokes about Cherokee people and the stereotype that everyone claims their great-grandmother was a Cherokee princess. This was new to me, because where I grew up most people are Cherokee. It was an adjustment I had to make. I could let it offend me, or I could take it as a compliment that other people want to be Cherokee. Everyone wants to belong or feel connected to a group of people.

This dress is my perception of the stereotype. If we actually were to have Cherokee princesses—historically, Cherokee people didn’t have royalty—this is how I envision one dressing. They would look something like you would see in children’s movies but with a touch of Cherokee designs. The dress’s bodice features fabric designed by Joseph Erb (Cherokee Nation), with Cherokee basket designs. On the skirt and sleeves, I used diamonds similar to the rattlesnake patterns found on tear dresses and stomp dance skirts worn by many Cherokee women in Oklahoma.

My Great Grandmother’s Cherokee Princess Dress

Hoop skirt, Cherokee basket print fabric, combined cotton/polyester, organza, bias tape, sequins, corn beads, glass beads, pearl beads, satin ribbon

56” x 45” x 45”

Credit: Joseph Erb, Cherokee basket fabric