3 minute read

3.4 Emotions Response in Psychology

Emotions are a feeling state that involves thoughts, physiological reactions and outward behaviours. However psychologists have continued to debate about how exactly the mind and body relate to each other and a unified theory of emotions remains elusive. According to Levenson, emotions are a survival instinct preserved from natural selection “due to the need for an efficient mechanism able to mobilise and organise the selection of quick responses from highly differentiate and disparate systems when environmental stimuli pose a threat to survival” (Bota et al., 2019, p. 140992). The seeming common ground among researchers is that emotion is particularly difficult to define (Fortkamp, 2005). Scientific discussion of emotions can be traced to 1872 when Charles Darwin published The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (Keltner, Oatley, Jenkins, 2013). Darwin investigated the physiological and behavioural components of emotions but ultimately regarded them as ‘expressions’ of feelings felt by animals and humans. Emotions were taken for granted as subjective states of experience until the early twentieth century (Griffiths, 2003). In the 1980s psychologists began to recognize the importance of affect in human experience, prompting much research related to emotionality and mood (Watson & Clark, 1997). However, several lines of thinking emerged defining affect as it relates to emotions in different ways. Most definitions of emotions are relative to a larger theoretical explanation of why we experience emotion or what causes emotions. Fig 38 is a diagram of just some of the different theoretical frameworks addressing the origins of emotions. Seeking to clear up the confusion, a seminal study Core Affect, Prototypical Emotional Episodes, and Other Things Called Emotion: Dissecting the Elephant was published in 1999 introducing the Circumplex model of emotions. Episodes of emotion vary along different dimensions like intensity, pleasure or degree of activation. The disparate experiences of riding a roller coaster or being chased by a bear can both have a high level of activation, though the former would be a more pleasurable experience. Factor analysis and multidimensional scaling are used for analyses of self-reported emotions, facial expression and vocal expressions often yield two broad dimensions

that can be interpreted as a level of pleasure or arousal. However categories of emotions do not cluster at the axis which is what creates the circumplex as a multi dimensional structure (Russell & Barrett, 1999).

Advertisement

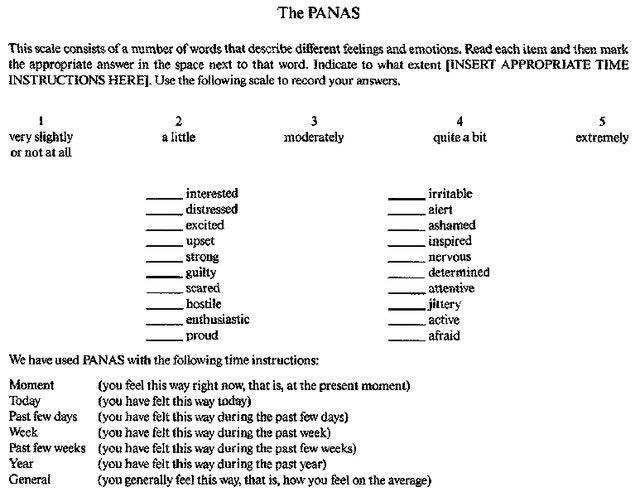

It can be summarized that two points of view encapsulate the way that scientists model emotions. The first, such as the circumplex model, consider emotions “as a continuous function and models them across multiple dimensions, such as the affect polarity, or valence, associated with the pleasantness or unpleasantness of the emotional stimuli, and the arousal that is the level of activation, ranging from calm to excited” (Novielli & Serebrenik, 2019). Other theories reflect a more discrete viewpoint that seeks to identify a smaller set of basic emotions (Novielli & Serebrenik, 2019). The attention to measuring emotion was developed by psychologist David Watson who created the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale measure prior to the circumplex model in 1988. Watson examined such factors as which emotion words and terminology best measured the positive and negative dimensions, how time frames impacted participant responses as well as different

Fig 38.Theoretical Constructs of Emotoin (Fortkamp, 2005)

formats for the scale. However many studies since that time have shown that participants experience more than one concurrent affect responses which requires that researchers use a “battery of affect items to accurately differentiate emotional responses” (Marcus et al., 2017) The slider method utilized in the prototype for this thesis is modeled from one developed by psychologists George Marcus and W. Russell Neuman. In a relatively new study from 2017, they present an updated format, stemming from the original PANAS scale. This format is digital and utilizes sliders instead of radio buttons. They found that the slider format produces a cleaner and more “discriminating array of results than does the radio button format” as it captures continuous data (Marcus et al., 2017, p. 14). They also noted the optimal placement of the slider value starting position was at the midpoint as it had the least influence on participant responses.

Fig. 40 Different Circular Models of Emotions (Russell & Barrett 1999)

Fig.41 The PANAS Scale (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen, 1988)

Fig. 42 Digital, Slider Based Self Report User Interface (Marcus, 2017)