Anthology + Catalogue

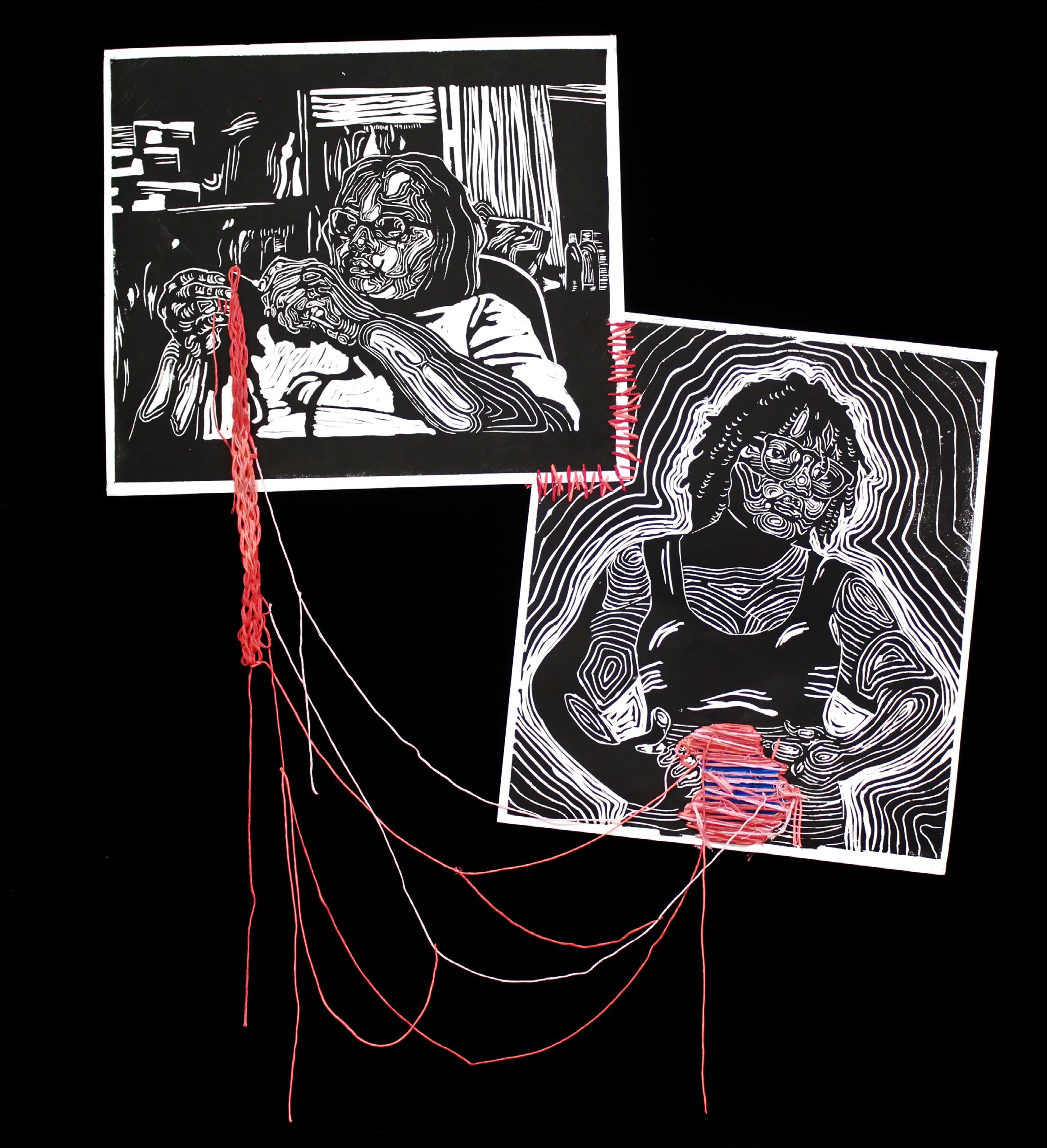

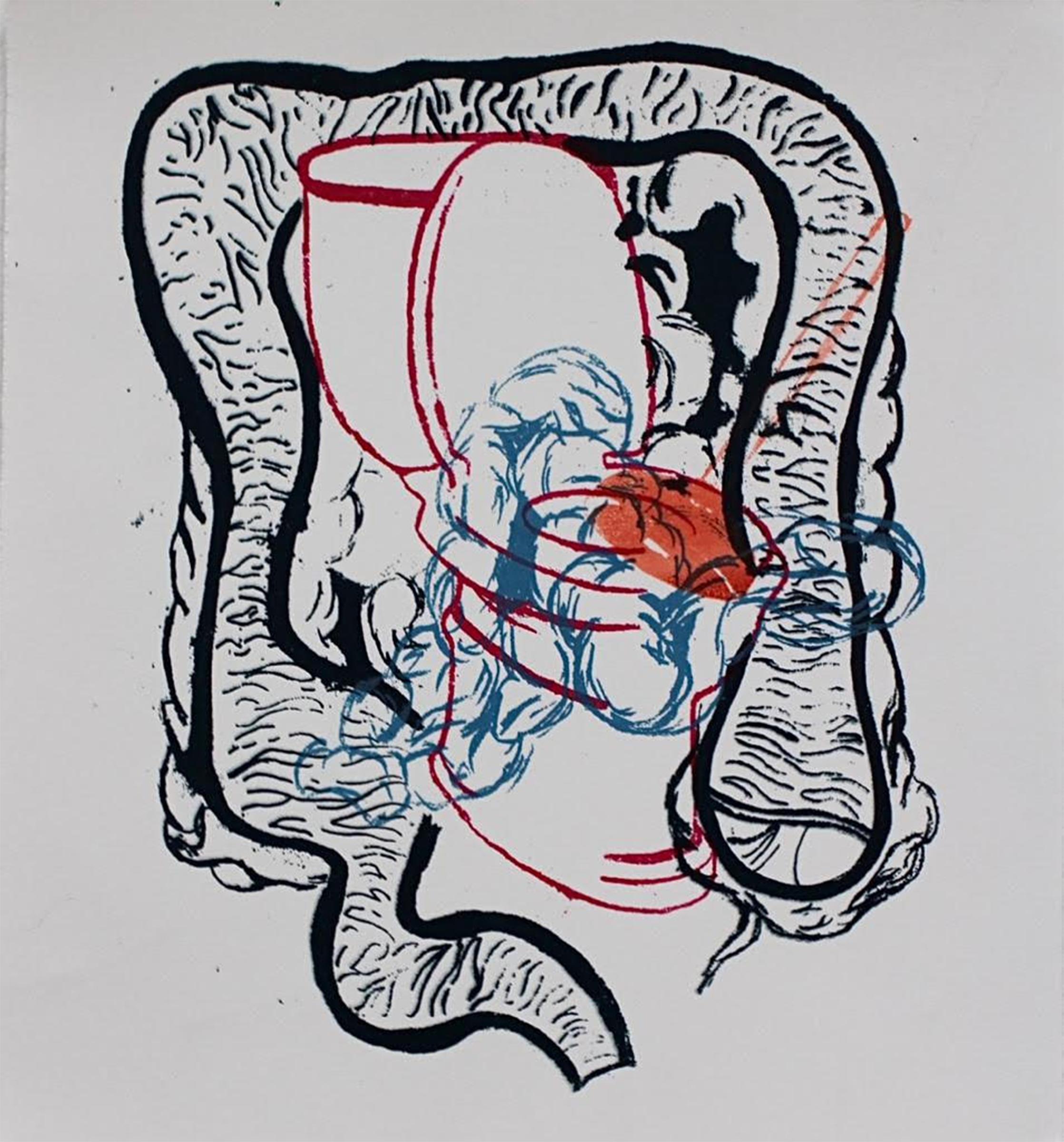

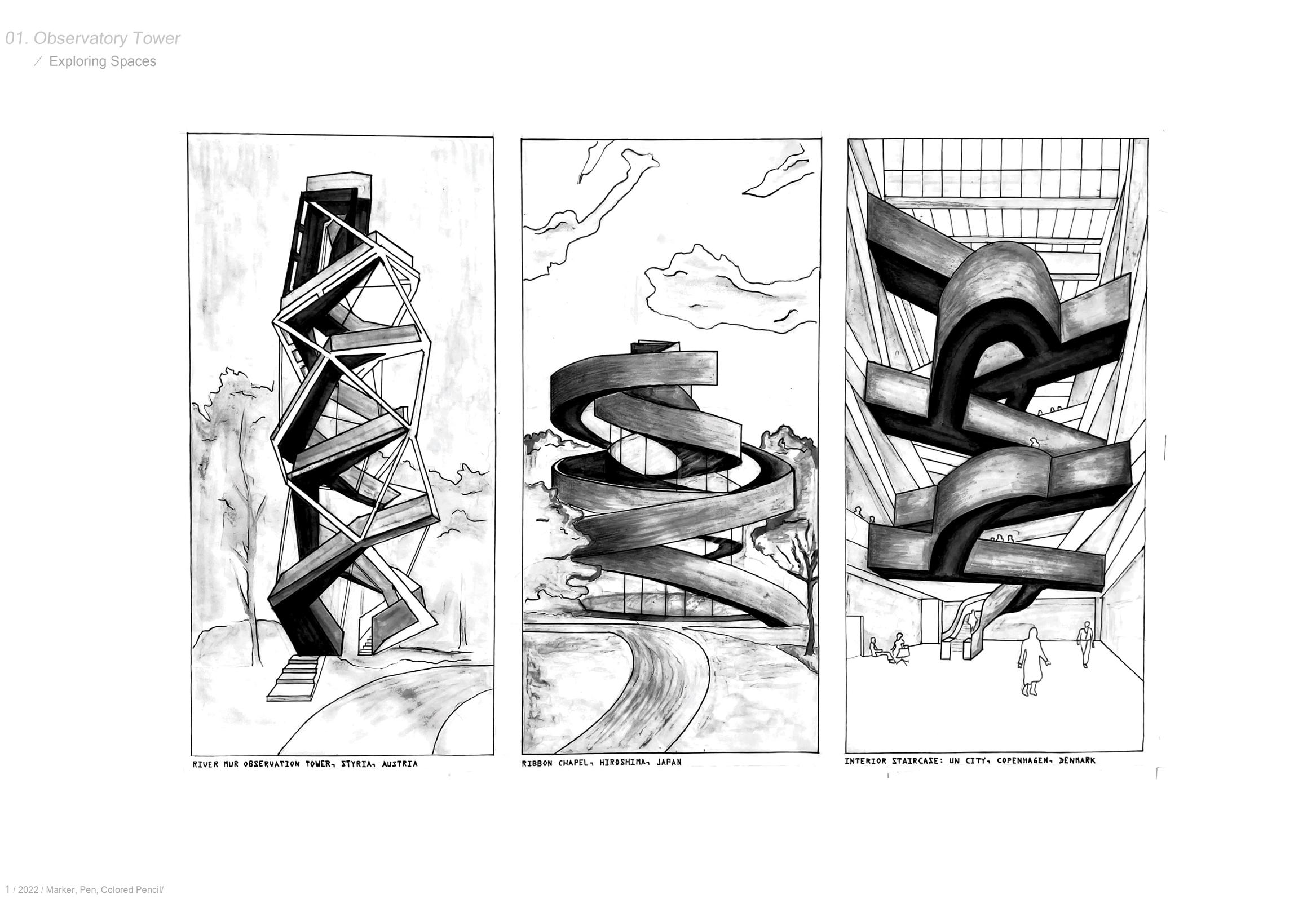

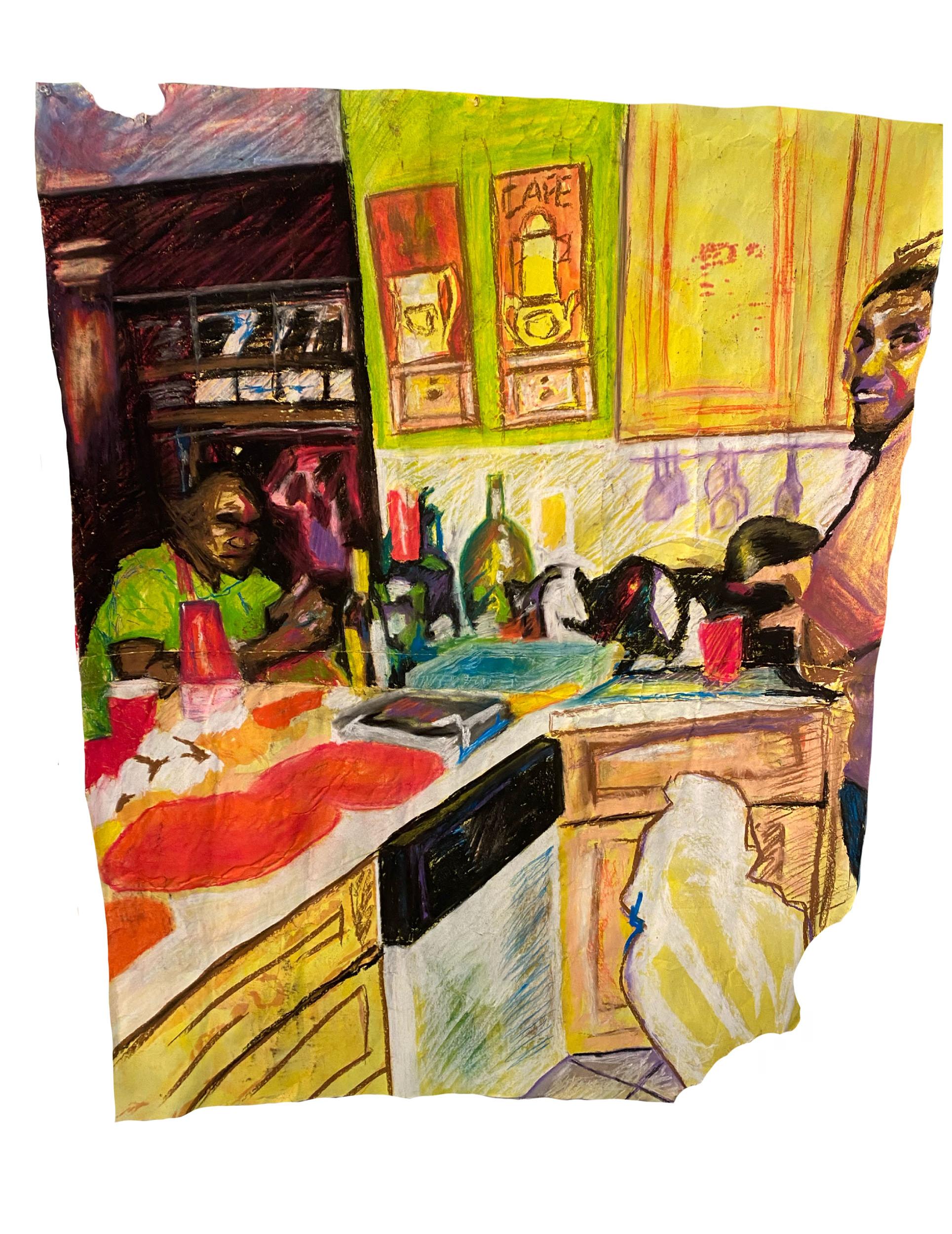

Select works by the 2023 YoungArts Honorable Mention and Merit award winners

Select works by the 2023 YoungArts Honorable Mention and Merit award winners

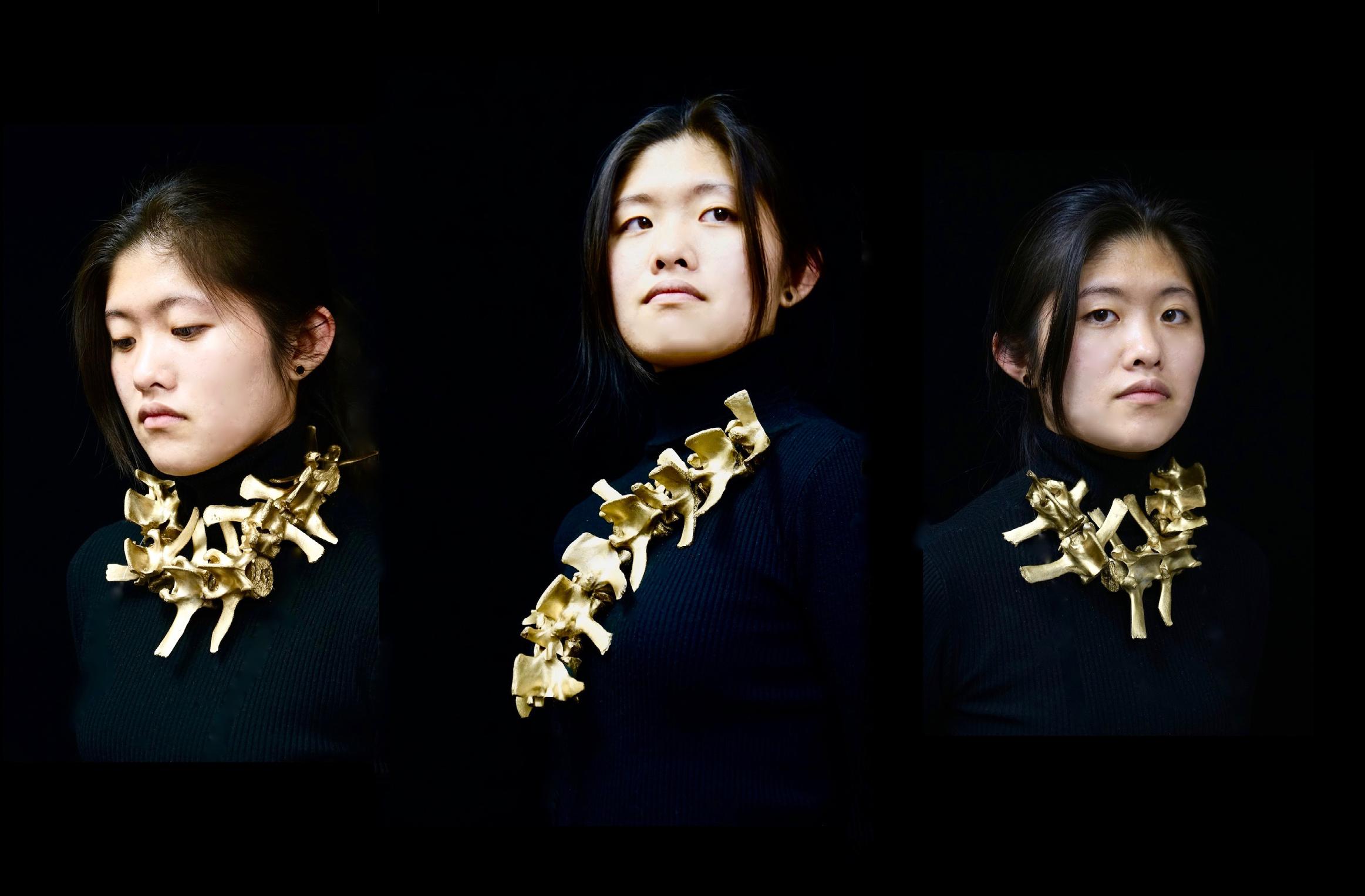

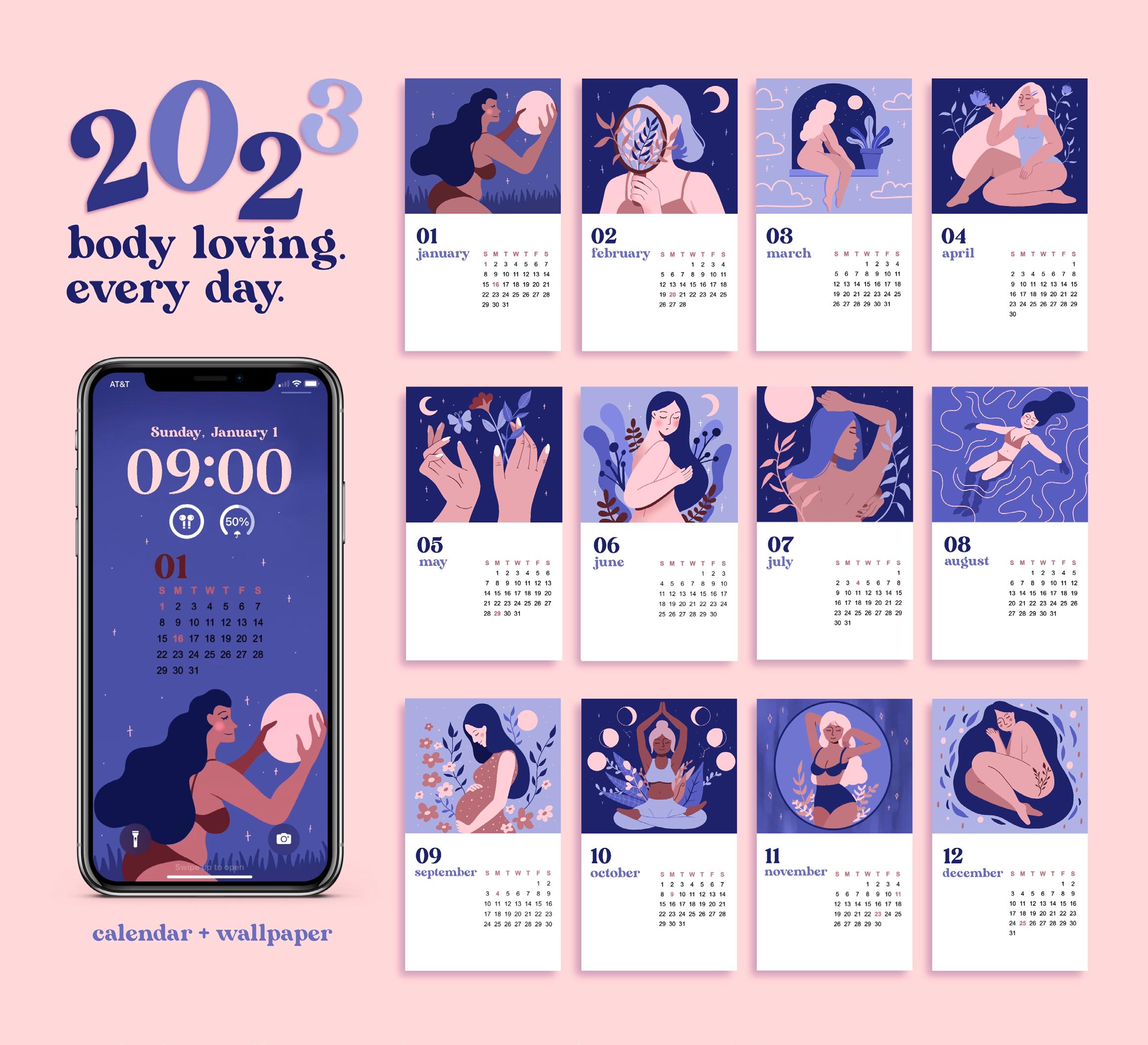

2023 National YoungArts Week T-Shirt

Designed by Kelley Lu (2021 Design Arts)

2023 National YoungArts Week T-Shirt

Designed by Kelley Lu (2021 Design Arts)

We are thrilled to welcome you to this Anthology + Catalogue, comprising works by the 2023 YoungArts Honorable Mention and Merit award winners in Design Arts, Photography, Visual Arts and Writing. An affirmation of the caliber of their expressions, these editions are often the first opportunity for young artists to see their work published and represent a bold step toward a professional future in the arts.

Our work is a continuous process that depends upon the knowledge and commitment of a vast network of guest artists, teachers and educators. We are grateful for the many partnerships and artists who have helped inspire this next generation of artists. We extend our gratitude to Anthology Editor, Jordan Levin.

This volume and YoungArts programming are made possible with the generous support of many.

Please visit youngarts.org/donor-recognition for a complete list of donors.

Above all, we extend our sincerest gratitude to the artists featured. We dedicate this publication to you, your families, teachers and mentors.

INT. GARAGE - MORNING

TITLE CARD: AUSTIN, TEXAS.

CIRCUIT OF THE AMERICAS. ROUND 20.

It’s the twentieth race of the Formula 1 2022 season and the second of the three United States Grands Prix. Ferrari is toe to toe with Mercedes for the constructor’s championship and Ferrari’s Farris Lawrence is six points behind Mercedes’ Eero Heikkinen, the reigning world champion and top contender for the driver’s championship. Elias Becker, Farris’ teammate, follows closely behind at third.

Farris is the first American to race in Formula 1 in quite some time. After suffering a bout of appendicitis, he was unable to race during the Miami Grand Prix, and so today’s race will be his first American race.

The pit crew is rushing around Ferrari’s sector of the pit lane more so than usual, a flurry of red and yellow buzzing about the garage door opening. In the middle of it, ANTONIO (50, Ferrari Team Principal & former Formula 1 driver) has a pair of headphones around his constantly craning neck.

NEIL

I’m sorry sir, but I don’t think we have it.

NEIL (23, Ferrari engineer) has his headphones on his head and a clipboard in his hand. He’s been given the largely avoided job of being Antonio’s punching bag for the day.

ANTONIO

What do you mean? Where the hell is that tire? (stressed, hand on his forehead)

It’s an 18-inch rubber disk. How the hell do we lose that?

NEIL (to himself)

I’d argue it’s a lot more than that...

At the center of the garage is a bright red Ferrari F1-75 with a white fin, yellow overhead camera—and three tires.

The tires each have a yellow stripe on them, signifying they are MEDIUM COMPOUND tires, save for the left rear, which is noticeably bare. The car is lifted on a jack, making the naked axle stick out like a sore thumb.

LUCIA (32, Ferrari Principal Strategy Engineer & general voice of reason) intervenes, sick of Antonio’s complaints and ready to do her job. This is a common occurrence, unfortunately.

LUCIA

He’s just going to have to start on the hards.

ANTONIO

He can’t start on the hards.

LUCIA

Why not?

ANTONIO

This is COTA and he’s starting P3— if we want even a fighting chance against Heikkinen, his tires have to warm up quickly to overtake and last long enough to create a gap. Not to mention that everyone else is starting on the mediums too—our entire strategy will crumble.

LUCIA

No, it won’t. Let’s say Farris does fall behind, okay? By lap 12, most teams will be making their first stop and everyone else will be on the hard compound anyway—yes, tire deg is high, and qualifying proved that quickly enough, but he’s an aggressive enough driver to make up positions once the tire playing field is leveled.

Not to overstep, but he started on mediums in Zandvoort while everyone else was on softs and we did just fine—even got a podium.

(to Neil)

ANTONIO

He started and finished P3 in Zandvoort. That’s fifteen points. I don’t want fifteen points.

Antonio doesn’t want to admit that Lucia might be right—and so he avoids addressing her point at all.

LUCIA

I’m sorry Antonio, but what exactly are you hoping for here?

ANTONIO

A win.

LUCIA

Oh my God. You’re kidding, right?

ANTONIO

No, Lucia. I’m not. It’s his home race. He’s starting in the second row. He should win.

LUCIA

Look around, Antonio—it’s the hards or no race. If he finishes P2 and gets the eighteen points, that’s only seven points less than P1. He’s still going to be the second-place contender for the championship either way. Do you really want to risk all of this for seven points?

Neil can’t help but step in.

NEIL

Also...there are three US Grands Prix this year...even if he doesn’t win this one, he’ll still have Vegas.

To say that Neil’s words went in one ear and out the other would imply they even reached Antonio at all.

ANTONIO

Lucia, look at me and tell me you want to be the team that cost your driver a home race because you lost a tire.

Amid a crowd of people dressed in red and yellow, a single man stands out in an ordinary jean jacket and white t-shirt. He looks to be about fifty, hands in his pockets, looking around.

FARRIS LAWRENCE (24, American Ferrari driver) is kneeling on the ground with his flaming red suit unzipped and tied around his waist. There is a little boy in front of him wearing a red hat with a bold white ‘29’ on the bill—Farris leaves his autograph just below it.

FARRIS

Now don’t lose that, alright? If I play my cards right, you just might be able to sell it for a lot of money one day.

BOY

I’d never sell this. I started karting because of you!

FARRIS (laughing)

Really? Have you won any races yet?

BOY

No... but I will!

The boy’s father, just off to the side, laughs along with Farris. It’s a nice moment.

Farris looks up and waves at the crowd. Some cheered, others didn’t notice—it’s still early. As he is surveying the crowd, the sore thumb in the jean jacket catches his eye, just close enough to recognize his face. It can’t be—but it is.

Farris’ entire demeanor changes. He lowers his hat and chin, turning back to face the boy and his father. He puts on a show smile.

FATHER

Thanks, man. I really appreciate this. He really does look up to you.

FARRIS

Yeah, no worries. Keep an eye on him, he’s got the energy.

FATHER (laughing)

I will. Good luck today—bring it home.

FARRIS

I’ll try my best.

Waving off, Farris walks off the track and starts making his way to the pit lane.

INT. GARAGE - MORNING

After a slow walk to and through the pit lane with several stops and conversations along the way, Farris enters the garage with a refillable water bottle in his hand and a lot on his mind.

Already preoccupied, the sight of the car’s current tire-less state doesn’t take any weight off.

FARRIS

What’s going on? Why does the car only have three tires on? It should be ready by now.

Lucia sighs, rubbing her forehead.

LUCIA

I’m sorry Farris, but it seems the left rear has gone missing, and we can’t find a replacement.

FARRIS

What?

ANTONIO

—But we will. You’re starting on the mediums, and we’ll do two stops, like we discussed. Mediums, then two stints on the hard compound.

FARRIS

(not quite yelling, but angry)

How the hell do you lose a tire...a whole tire?

Farris sighs loudly, then runs his hand through his hair, taking his cap off in the process.

FARRIS (CONT’D)

(looking off)

I can’t lose this race.

LUCIA

You won’t. The hards are ready to go. Once Antonio stops arguing and lets me do my job, we’ll get those on and have the car on the grid in no time.

FARRIS

(still not quite present— to himself)

I can’t finish lower than second, either. (turning towards the trio)

Where’s Elias?

ANTONIO

You’re going to win. Don’t worry about Elias, he’s starting on the mediums too.

Lucia is not happy.

FARRIS

No, I mean I need to talk to him.

NEIL (timid)

I think he’s up in his room getting ready...

FARRIS

Okay..

(takes a moment to think, not meeting anyone’s gaze) Okay.

He heads off deeper into the garage and up a pair of stairs in the back.

INT. HALLWAY - CONTINUOUS

At the end of the hallway, there are two doors beside each other. One has a large ‘FL29’ decal and the one to its right bears an ‘EB87’. Farris stands in front of the latter and knocks.

ELIAS (O.S.) (from inside the room)

Come in!

Farris opens the door and walks in—

INT. ELIAS’S ROOM - CONTINUOUS

The room is well-lit and on the smaller side. There are various pieces of art and letters scattered about the walls in a haphazard manner—they’re going to be packed up soon anyway.

ELIAS BECKER (24, German Ferrari driver) is sitting on a couch with his race suit tied around his waist, similar to Farris. He’s tying his shoes and his cap sits beside him. Farris shuts the door and leans against the doorframe.

ELIAS

Hey man. You ready?

Yeah... yeah.

FARRIS

Elias picks up on his reserved tone and pauses to take a look at Farris.

ELIAS

Doesn’t sound like it. What’s up?

FARRIS

Have you been down to the garage recently?

ELIAS (back to tying his shoes) No, why?

A beat.

FARRIS

Well, as of right now, my car is down there with three mediums on.

ELIAS (stops)

..Three? You’re kidding.

FARRIS

Nope. They lost the left rear, apparently.

ELIAS

How do you lose a tire? Aren’t they heavily monitored?

FARRIS

That’s what I said. Antonio says it’ll be fine and that we’re both starting on the mediums, but I’m not sure how likely that is. I’m not entirely sure what I’m gonna do.

ELIAS

Yeah, I’m with you. But don’t let that get in your head, alright? If anything, they’ll take the mediums off mine and put them on yours.

You’re starting ahead anyway.

Elias is used to this—for the majority of the season, Ferrari’s general strategy has been to utilize and maximize Farris’ aggressive driving style and Elias’ defensive skills. Farris carves the way for Elias to get behind him and Elias helps create a gap between them and whoever is behind. In essence: Farris gets them to the front, Elias makes sure they stay there.

Unfortunately, this strategy largely means that Farris ends up scoring more points than Elias and thus becomes the team’s priority. Being the second driver isn’t always fun—but sometimes that’s the price you pay to be on a top team, or at least that’s what Elias tells himself.

FARRIS

It’s not the tires.

Elias finishes tying his left shoe and leans back. Farris continues standing where he is, one foot up and leaning against the doorframe.

A beat.

My dad’s here.

What?

FARRIS (CONT’D)

ELIAS

FARRIS

Yeah, I know...I’m not entirely sure how to feel about it.

ELIAS

Where is he? Did you talk to him?

FARRIS

(shaking his head)

Nah, I just saw him in the grandstands. (beat)

If he wanted to talk to me, he could’ve asked any of the marshals or... anyone, really. I’d rather not go where I’m not wanted.

ELIAS

Well, if he’s here today, maybe he wants to change that. When was the last time you talked to him?

Farris takes a moment to think. He opts to ignore the question.

FARRIS

I have to win this race, Elias. Elias doesn’t miss the question dodging. He switches tones.

ELIAS

(trying to lighten the mood)

You will. I’ll make sure I’m the only car in your rearview mirrors, alright? That’s my job.

Farris isn’t swayed.

FARRIS

I don’t think he’s ever seen me race before.

ELIAS

...Really? Not even karting?

FARRIS

No, he always dropped me off and left. His first race can’t be the one I lose.

The room is quiet, and Farris’ words settle into the open space—a beat.

FARRIS (CONT’D)

Sometimes I hear radio replays and I catch myself off guard by how much I sound like him.

Having finished getting ready, Elias puts his cap on, stands up, and meets Farris’ gaze.

ELIAS

Don’t make this about him, Farris. If anything, it’s about what you’ve been able to accomplish despite him. (beat)

ELIAS (CONT’D)

You’ll win the race today—on mediums or hards—and you’ll do it not because he’s watching or because he’s worth impressing. You’ll do it because you’re the best damn driver on the grid. Farris smiles. This is why they make such a great team.

FARRIS

Thanks man, I needed that.

ELIAS

All I did was help clear up some of the fog. (clapping Farris’ shoulder)

Now go down there and tell Antonio to take his head out of the clouds and get that car into starting position.

FARRIS (chuckles)

I will.

INT. GARAGE - MORNING

Farris enters the garage with a mission. Operating under pressure is nothing new to him, and he’s handling it the best and only way he knows how— just get in the car and drive.

The car is still up in the air and Antonio, Lucia, and Neil are crowded around a wall of screens along with several other engineers and the pit crew. They’re whispering furiously— Farris comes up from behind and interrupts them.

FARRIS

Does Elias have a full medium set?

Lucia and Antonio look at each other.

LUCIA

Yes, his car is all set and ready to go.

FARRIS

Alright. Take these mediums off and put on the full set of hards.

ANTONIO

Son—

LUCIA (to crew) You heard him.

ANTONIO (to Lucia & crew)

Now just you wait! (to Farris)

There’s still time.

FARRIS

No, there isn’t. And you know it. That car needed to be on the grid ten minutes ago. Now get those tires on my car.

Antonio is hesitant but would rather not get in Farris’ head. He really needs him to win this race.

EXT. TRACK - AFTERNOON

Classic rock echoes over the speakers as the crowds chatter in the distance.

All twenty cars are present on the grid in starting positions with each driver waiting at the wheel. Each car’s tires are individually enveloped in a protective, heated blanket.

EXT. GRANDSTANDS - CONTINUOUS

The aforementioned sore thumb—Farris’ father—is still sitting awkwardly in the grandstands. He’s never been to or even watched a Grand Prix before and he’s not exactly sure how this all works. Looking around, he can’t help but notice all the people around him in red and yellow Ferrari shirts and caps, most of which are clad with ‘29’ or ‘87’.

A voice is echoing across the grandstands as all eyes shift to the drivers on the grid—DAVID JOHNSON (52, British sports commentator) is speaking to his co-commentator and analyst, BRUCE HERRINGTON (37, British) and announcing all of the starting positions.

DAVID (V.O.)

—and that leaves both Ferraris on the second row with Lawrence starting at third and Becker at fourth. Just ahead of them are Jefferson and Heikkinen—the two Mercedes’—at second and first, respectively.

Now correct me if I’m wrong, Bruce, but this is the first time since 2015 that the United States has had one of their own on the grid— Alexander Rossi, right?

Farris is sitting in his car with his visor up. The operator ZOOMS IN on him as Bruce and David discuss his predecessor. Farris is focused, his eyes narrow and set ahead.

A graphic span the top of the screen: FORMATION LAP. In a procession led by two silver Mercedes cars, the grid of cars slowly breaks into a roll through the track.

BRUCE (V.O.)

You are not mistaken! Rossi finished P12 out of twelve—there were eight retirements during that race! Another interesting thing to note is that while there are technically three home races for Lawrence this season, this is the closest to his actual home. The Ferrari driver was born and raised in Webster, Texas—just three hours away.

EXT. DIRT TRACK - FLASHBACK

A YOUNG MAN (early 20s, race car driver) is in a go-kart driving in a figure eight around a dirt track.

It’s Farris’ father—years before Farris was ever born. Although the majority of his face is obstructed by his helmet, there’s an unmistakable Lawrence glow in his eyes. The dirt sprays beneath his wheels as he snakes around each turn with grace and agility, and the sun beams down on him in a golden haze.

EXT. GRANDSTANDS - PRESENT

The crowd CHEERS at the mention of Farris, their homestate hero—the grandstands are PACKED. Hoards of people in red and yellow merchandise fill the gaps, with many raising flags and wearing cowboy hats.

DAVID (V.O.)

2015 was one for the books, I’m sure.

To your hometown point, I’ll admit the crowd did seem a little put off on Saturday when Lawrence qualified third, but I think it’s safe to say that the sullen feeling is long gone!

BRUCE (V.O.)

Yes! I’m not sure if the viewers at home can hear it, but there has been music playing throughout the stadium all morning.

A lawn lined with foldable chairs and people in cowboy hats stands idly and excitedly chattering about, itching for the race to begin. The crowds cover every square inch.

BRUCE (V.O.) (CONT’D)

Springsteen, Journey, Guns ‘N Roses-all-American rock! Spirits are high in Austin, Texas as the crowd cheers on their red, white, and blue maverick: Farris Lawrence.

EXT. TRACK/GRID - CONTINUOUS

Farris’ blue helmet stands out among the abundance of red of the car. The forehead and crown of the helmet are adorned with the white outline of a longhorn’s horns design—an ode to the Texas state animal and his aforementioned nickname.

ANTONIO (V.O.)

(on team radio)

Alright Farris, I just spoke to Elias and he’s good to go. Ready to race?

FARRIS (V.O.)

(team radio)

As I’ll ever be.

Having made it back to the start/finish straight, each car takes its place on the staggard painted grid. The Circuit of the Americas is a counterclockwise track—left turns all around. Heikkinen’s P1 position leads with his teammate in P2 diagonally behind him. This means his spot on the grid is going to lead him to the outside of Turn 1, and thus allows for it to be easily overtaken.

One final car parks into position, and then a row of lights above the track turns on one by one, then all turn off at once—it has begun.

DAVID (V.O.)

In comes the last Williams in P20— and it’s lights out and away we go!

Each car reacts in time, all rushing and crowding to make up positions. Heikkinen, Jefferson, Farris, and Elias all get a good start with Jefferson covering Heikkinen on the inside of Turn 1 to prevent Farris from overtaking early on.

INT. F1-75 CAR - CONTINUOUS

Silence.

Farris’ eyes are steady and focused, unblinking through his visor. His steering wheel flashes with various colors and buttons, illuminating his face through his helmet. He’s trying to be gentle with his tires—he has to make them last as long as he can.

A sight in his rearview mirror—Elias. Making a decision, Farris allows Elias the chance to overtake him. He knows Elias will give the position back.

EXT. TRACK - CONTINUOUS

Return to sound.

DAVID (V.O.)

—It’s a ferocious start for Jefferson, having to defend against one angry Lawrence just into Turn 1. He clearly wants to overtake, but he knows he can’t run his tires this early on. Why is it that P1 directly leads into the outside of the turn and not the inside? That’s something I never understood about this track—

Interrupting him is the slight brushing of Jefferson’s rear right tire with Becker’s front left, causing both drivers to run off track. Jefferson continues to spin to the right, eventually crashing into the barriers. Elias spins twice but doesn’t crash—he’s still in this race.

BRUCE (V.O.)

OH! Not even into Turn 2 and it’s looking like we’re going to have a Safety Car! Jefferson and Becker collide, causing the Merc to DNF— but it seems Becker’s just fine!

Farris knows what to do. Speeding up just the slightest bit cements his spot in P2.

FARRIS (V.O.)

(radio)

Is Elias okay?

LUCIA (V.O.) (radio)

He’s alright—just some front wing damage.

TRANSITION TO END OF RACE — LAP 53/56.

Farris is currently leading the race at P1, but he’s been wheel to wheel with Heikkinen on several occasions: the Mercedes driver forcing him into cutting a corner, issues with the Drag Reduction System, and each of them receiving a five second time penalty—one for forcing another driver off the track and one for speeding in the pit lane, respectively. Farris is now on the hard compound tires that he’s been working with for roughly thirteen laps.

INT. F1-75 CAR - MID-RACE

Farris is sitting in his car, hands on the wheel, going roughly 200 kmh. He’s maneuvering through the turns quickly and masterfully, a flurry of red, black, yellow, and white.

FARRIS (V.O.) (radio)

How do the tires look?

LUCIA (V.O.) (radio)

They’re good. Three laps to go—keep pushing.

EXT. GRANDSTANDS - CONTINUOUS

Farris’s father stands, watching his son dominate the track like it’s the easiest thing in the world. The fatherson resemblance is uncanny.

EXT. DIRT TRACK - FLASHBACK

A sign at the entrance reveals the name of the track: the CAVERIN MOTOR SPEEDWAY. The sign is weathered and rusted, but the words are still legible.

The blue go-kart is still making its way through the figure eight with a dusty black ‘57’ painted on the side at the center of a white circle. The tires of the young man’s kart dig into the dirt, spraying it around and CUTTING TO—

EXT. COTA - PRESENT

Farris’ rear tires sparking after swinging out of Turn 17.

DAVID (V.O.)

Lawrence continues to lead the race away from Heikkinen, and let me tell you Bruce, that man is driving like his life depends on it.

BRUCE (V.O.)

Well David, in a way, it does. The championship gap between them is tight, and Lawrence needs every point he can get to win it. The same can be said for Heikkinen— these are two men who cannot help but want the same thing. It’s just a matter of who’s good enough to get it.

Tension builds underneath the sound of the crowds cheering. Then, a voice echoes above all the noise, drowning it all out.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Icarus fell on the first morning of autumn.

EXT. CAVERIN MOTOR SPEEDWAY - FLASHBACK

Just out of the intersection of the figure eight, Farris’ father speeds through the turn. There’s no one else on the track but him—he’s just having some fun.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Back then, the sun was a friend. Its beams caressed the orange leaves, the brown and rich earth like a fingertip to the chin.

Then, through the dust and the summer sun, the wheels beneath the kart LOCK UP. Farris’ father drags through the dirt, spinning in circles.

Tension continues to build, the violins melting into the sun of the crash.

EXT. COTA - PRESENT

Farris and Heikkinen are wheel to wheel, the flaring red Ferrari just inches ahead of the silver Mercedes. Everything seems to have slowed down.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

That morning, a new light emerged from beneath the November harvest— a sharp laser piercing through the air from inside the barn.

Out of Turn 19, Farris is forced to take the outside of the turn and Heikkinen takes the inside—he’s going to pass Farris once they make it past the apex of the turn. With just a lap to go, Farris cannot lose like this.

Shoving Heikkinen into the turn, Heikkinen FIGHTS BACK and stands his ground, forcing their tires to make contact.

Farris is airborne—his tires hit the edge of Heikkinen’s and rolled above them.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

In the quiet of the trees, the sound of the wind billowing ruffles across the hills, creeping out into the world—unnoticed and insignificant.

It’s not about the race anymore.

EXT. CAVERIN MOTOR SPEEDWAY - FLASHBACK

Farris’ father SPINS out of the end of the end of the track, a blur of golden dirt and sun—

EXT. COTA - PRESENT

Farris’ car FLIPS and begins to scrape across the track upside down, only to hit the edge of the track and take one final flip out right ahead of the grandstands.

EXT. CAVERIN MOTOR SPEEDWAY - FLASHBACK

His car is upside down.

CLOSE UP OF: Farris’ father’s eyes, glowing in fear and adrenaline.

CUT TO—

EXT. COTA - PRESENT

CLOSE UP OF: Farris’ closed eyes. It’s dark and his head is tucked firmly between his shoulders. The halo—a wishbone- shaped carbon fiber rod doming above the cockpit—saved his life.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

The very beams that once brushed his skin now sizzled his wings to a crisp, and Icarus was left a mess of wax and scabs harrowing through the sky.

EXT. CAVERIN MOTOR SPEEDWAY - FLASHBACK

Farris’ father’s eyes close.

NARRATOR (V.O.)

Over the hills and trees, a faint and far splash echoes across the landscape, unheard.

EXT. GRANDSTANDS - PRESENT

Farris’ car lays in the grass, upside down. It has crashed directly in front of the grandstands his father stands in.

CLOSE UP OF: his father’s face, pale and afraid.

CUT TO—

INT. F1-75 CAR - CONTINUOUS

Farris’ eyes open. He’s alive.

when i was a crow -

i drink your blood like rum shots when you’re spilling out on the side of the road & we’re naked & you’re lost— you pushed back my skin & ate me from the bottom up the sky’s the limit but there’s fingerprints in my core, there’s bite marks up my thighs.

i hit you with my car because i’d rather you dead than without me. i’ll carve you like a pumpkin— let me get my outline / let me get my knife.

sinew tangling, looping between my teeth, your veins my floss. i sucked until my lips were tender with exhaustion, until every thick tendon was doused in red, had grazed the inside of my cheek, been explored with the bumps on my tongue.

We are in MR. TEVIN’S pizza shop. It is a small shop with only a few tables to eat at. We see IMANI, 17, wiping down the tables in the front of the shop. We see SOULCHILD, 16, on his phone behind the counter. They are wearing all black clothes and white aprons. Soulchild’s boyfriend, JJ, 16, is walking up to the shop. Imani can see him through the front windows.

IMANI

(to Soulchild)

Your boyfriend’s here, Soulchild.

Soulchild looks up from his phone and smiles at his JJ as he walks through the door. Soulchild leans on the counter.

SOULCHILD (to JJ, soft)

JJ does the same.

Hey.

JJ (to Soulchild, soft)

Hi.

They kiss. Imani turns around and sees them.

IMANI

You guys are disgusting. My favorite part of summer is not having to see school couples making out everywhere, and now I can’t even have that.

JJ walks to Imani and bows.

JJ

Soulchild and JJ services, ruining single’s summers since 2020.

JJ comes up from his bow and smiles. Imani rolls her eyes.

SOULCHILD

Imani, we need to get you a boyfriend.

IMANI

Have you seen the guys around here? I’m good.

JJ and Soulchild look at each other.

JJ

What about you and Ryan? We’ve seen you guys— Imani cuts JJ off and scrunches up her face.

IMANI

We’re not talking about this.

JJ

He obviously likes you, and you like him so what’s the—

IMANI

I’m going to the kitchen.

Soulchild laughs.

JJ waves at her as she turns away.

Happy 4th of July!

JJ

Imani stops, turns around slowly, and makes a confused face at Soulchild, and Soulchild nods his head in response. JJ notices and is confused.

JJ (CONT’D)

What? What is that?

SOULCHILD

She’s asking me if you’re seriously saying, “Happy 4th of July!”

IMANI

I’m not trying to be mean; I just didn’t take you as that kind of guy.

JJ crosses his arms.

JJ

What kind of guy am I, exactly? Because I thought I was the nice guy who was just wishing you a happy holiday.

Soulchild takes a deep breath, realizing JJ’s wording mistake. Imani points at JJ.

IMANI

That. That. You’re the type of guy that would see today as a holiday, and me and Soul aren’t.

JJ faces Soulchild; his arms are still crossed. His face has no expression, but Soulchild knows that isn’t good.

SOULCHILD

(trying to be nice)

It doesn’t really make any sense for Black people to celebrate the 4th of July...or to go around wishing people a happy one. Like what does that even mean when you’re Black?

JJ

I’m also American, and it’s just one day to get together with family. You guys wish people a Happy Thanksgiving, even though that has bad origins.

(to Soulchild)

You came to my house and were happy eating turkey and watching football.

IMANI

Okay, but that’s different.

JJ

How?

IMANI

Thanksgiving became about doing stuff with your family, but today is about freedom.

JJ

Today is about family, too. I was at his grandmother’s cookout today with our families, and it felt nice getting to be around everyone. (to Soulchild) But you wouldn’t know because you refused to go.

SOULCHILD

I’m working.

JJ

You took this shift to get out of going.

IMANI

JJ, either way you put it, 4th of July isn’t a holiday for us. Sure, you can have your cookout, but don’t walk around saying “Happy 4th of July” like...like we weren’t enslaved when they made this holiday and like we still aren’t hurting.

JJ

I’m not hurting anyone, though.

IMANI

But people are still hurting. Police brutality, racial bias in the medical field, the pay gap. The list goes on.

JJ

But I didn’t do those things. I’m not a cop. I’m not a doctor or someone’s boss. Me saying, “Happy 4th of July” isn’t hurting them.

IMANI

Maybe it is. Maybe not knowing enough about it to care, a sort of blissful ignorance hurts them.

JJ

Blissful ignorance? Are you serious? Over four words? Now, I’m ignorant.

JJ looks to Soul. Soul is staring out the window and doesn’t say anything.

JJ (CONT’D) Soul?

SOULCHILD

JJ, you know how I feel about this.

JJ

Yeah, I do. I’ve heard you rant about it for hours, but you’ve never said anything like this before.

JJ waits for Soul’s response. Mr. Tevin walks to the front, wiping flour off his hands. Mr. Tevin is a short man in his 40s. He’s wearing all black and a white apron. He has a gold Africa necklace on.

MR. TEVIN

Imani, can you get started on the dishes?

Imani nods and heads to the back.

MR. TEVIN (CONT’D) (to JJ) JJ! How you been?

Mr. Tevin pats JJ on the back. JJ looks at Soulchild as he speaks.

JJ

Hey, Mr. Tevin. Happy 4th of July!

SOULCHILD (to JJ, annoyed) He doesn’t care about the 4th of July.

JJ (to Soulchild) I’m just being nice.

JJ looks at Mr. Tevin.

JJ (CONT’D) (to Mr. Tevin)

I can’t complain. I’ve been eating at his grandma’s cookout all day.

MR. TEVIN

Don’t tell me you didn’t save room for my pizza of the day.

Mr. Tevin proudly references the board with a pizza drawn on it.

MR. TEVIN (CONT’D) (New York accent)

The four chedda bout it pizza. (normal accent)

It has four types of cheddar on it.

JJ

I always got room for your pizza. I’ll take one pizza of the day and one Hawaiian.

Soulchild gets the slices. Mr. Tevin leans on the counter trying to look cool.

MR. TEVIN (rambly)

So, your aunt was at the cook–? Your aunt she’s—? How’s your aunt doing?

JJ and Soulchild look at each other. Soulchild holds back laughter.

JJ

She’s good.

MR. TEVIN

She hasn’t come through in a minute.

JJ

Yeah, she’s been really busy so…

MR. TEVIN

That’s wassup. That’s wassup. Well, tell her if she needa break for some...food to stop by.

JJ

Alright, Mr. Tevin.

Mr. Tevin walks out, and Soulchild busts out laughing.

SOULCHILD

You gon be calling him Uncle Tevin soon.

JJ mocks Soulchild’s laughing and stops abruptly.

JJ

You’re not funny.

JJ pays Soulchild for the pizza.

SOULCHILD

I’m a little funny. Just a little.

JJ

Can we go? It’s already past 7:30.

SOULCHILD

Hang on.

Soulchild goes to the back and comes back quickly.

SOULCHILD (CONT’D)

Let’s go.

SCENE TWO EXT. STREET - LATE DAY

JJ and Soulchild walk out of the shop and head down French Street. The street is lined with restaurants and different shops. They are walking on the sidewalk. JJ is holding slices of pizza. The sun is setting.

Is Musiq hanging out with us tonight?

SOULCHILD

Nah, he’s with some girl. Asia? I don’t know.

JJ

You’re not going to hang out with them?

SOULCHILD

Why would I?

JJ

To serenade her like y’all used to do in elementary school for all the girls Musiq liked.

SOULCHILD

So, you think you got jokes? I haven’t done that in years, JJ.

JJ

If I do remember correctly...the last time y’all, did it was four years ago when we were in seventh grade. For..um... what was her name? Tasha...something?

Soulchild sucks his teeth.

Whatever.

SOULCHILD

JJ stops walking and hands the pizza to Soulchild. JJ starts snapping, poorly dancing, and singing “Just Friends (Sunny)” by Musiq Soulchild.

JJ (singing dramatically)

I’m not trying to pressure you Just can’t stop thinkin’ bout you You ain’t even really gotta be my girlfriend.

Soulchild pushes JJ, making him stop dancing.

SOULCHILD (playful) Shut up, JJ.

JJ starts laughing.

JJ

I thought I sounded good. I got the steps going after a minute. You wouldn’t go out with me if I sang that to you?

Soulchild thinks for a minute, stroking his chin.

SOULCHILD

Mmmmmm..no.

No?

JJ leans slightly toward Soulchild.

No.

Soulchild leans slightly toward JJ.

Uh uh?

JJ leans slightly more toward Soulchild.

JJ

SOULCHILD

JJ

Soulchild leans slightly more toward JJ.

JJ (soft)

Consider it?

JJ leans even more toward Soulchild, their faces practically touching.

SOULCHILD (soft)

They kiss.

I might.

SOULCHILD (CONT’D)

I would, actually. If you never bring up me and Musiq “serenading” girls ever again.

They start walking again.

JJ

Ever? I don’t know if I could do that. I gotta remind you of your roots from time to time.

SOULCHILD

That is not my roots.

JJ

Soul, it’s how you got your name. Those are your roots.

SOULCHILD

I don’t know my roots? Says the guy who learned about Juneteenth from an ABC sitcom, but tells everyone he comes across (mocking)

Happy July 4th!

JJ

Blackish has been Emmy nominated for Outstanding Comedy many times, so I feel no shame watching the Johnson family.

SOULCHILD

But did they ever win?

JJ takes the pizza plate back and takes a bite out of one of the slices.

SCENE THREE

EXT. STREET - LATE DAY

Soulchild and JJ are still walking. The stores and restaurants are behind them. They’ve made it to their neighborhood now. Most houses are varying new two-story homes. It’s getting dark, and streetlights are on. Soulchild grabs a piece of pizza from JJ’s plate, takes a big bite, and sets it back on the plate.

JJ

That’s my pizza!

SOULCHILD (mouth full of pizza)

It’s good.

It’s mine. I’m hungry.

JJ

JJ takes a few long strides to cross the street. Soulchild follows after him, but a car cuts him off.

SOULCHILD

What happened to pedestrians first?

JJ (mocking jokingly)

What happened to not eating my pizza?

Soulchild rolls his eyes and looks upset. JJ takes notice.

JJ (CONT’D)

I was just kidding. I didn’t mean to–.

SOULCHILD

How was Grandma’s cookout?

JJ Soul, I’m–.

SOULCHILD (persistent)

How was it?

JJ

It was super boring without you there, but I had some hot dogs, so it was alright. Rickey said he was gonna go out and get some fireworks, so if we hurry back, we can probably still see them.

SOULCHILD

How many hot dogs did you eat? Twelve?

JJ

It wasn’t twelve. I had one.

SOULCHILD One?

JJ

Okay, two.

Two?

SOULCHILD

JJ

Fine, three. I had three.

Three?

SOULCHILD

JJ

I ate four hot dogs! Is that what you wanna hear? Who goes to a cookout and doesn’t eat?

SOULCHILD

If you already ate, then I should eat one of your slices.

Soulchild takes a slice of pizza. JJ continues to eat the other.

JJ

Your mom was having a good time bragging about you. (high pitched voice)

My son got a job over with Tevin, and he volunteers at the soup kitchen. Oh, he also gives swimming lessons at the pool…

SOULCHILD

What can I say? I am very impressive.

JJ

You are, but you could take one day off from work to celebrate with your amazing super cool super-hot boyfriend.

Soulchild stops because he notices his shoes have come untied. He bends down to tie them.

SOULCHILD

Like I’ve said before, celebrating a holiday for white people isn’t my thing.

JJ

Okay, whatever, but you could at least hurry up so we can watch the fireworks.

Soulchild begins to tie his shoes very slowly.

SOULCHILD

Mmhm.

JJ rolls his eyes. JJ folds up the plate and shoves it in his back pocket. Soulchild gets up.

JJ

It’s summer, Soul. We don’t have to work all of the time. I wanna have fun. I wanna hang out with you. Who cares if it’s July 4th or August 27th?

SOULCHILD

You never work, JJ.

I work. I worked at...

JJ

SOULCHILD

You’ve never had a job!

JJ

That’s not the point, Soul! There’s nothing wrong with having fun.

SOULCHILD

Whatever.

JJ

No. Not “whatever”. Why are you being like this today? You ditch hanging out with me to work all day. Then, I come to walk home with you, and you let Imani call me ignorant. I ask you for something so simple, watching fireworks with me, and you don’t want to.

SOULCHILD (harsh)

I don’t want to keep talking about this.

JJ

Why not?

SOULCHILD

Because I don’t want to, JJ. Okay? Leave it alone.

JJ

But why? Is it me? Did I do something? This can’t be over a stupid day.

SOULCHILD

You’re right. Today is stupid. This holiday is such a stupid thing, and you look stupid celebrating it.

JJ

So, you think I’m ignorant, too?

SOULCHILD

JJ, you’re not even listening to me.

JJ

Yes, I am. (mocking Soulchild)

4th of July is stupid. If you’re Black, you can’t celebrate! I’d rather work instead of just ignoring what day it is and spend time with JJ because he doesn’t know or care about anything.

SOULCHILD

I’m trying to have a real conversation with you.

JJ

So am I. I’m telling you; I don’t care about the 4th of July. Is it hypocritical? Yes. But is it also a day to get together and have fun? Yes! I don’t wanna argue with you anymore, Soul. It’s just one day.

SOULCHILD (soft)

It’s not. You’re not listening to me.

JJ (stern)

I wanna see the fireworks.

Soulchild sits on the curb of the sidewalk. JJ stands over Soulchild about to go off, but Soulchild speaks first.

SOULCHILD

You’re not listening to me, JJ. It’s more than family. It’s more than cookouts. It’s more than just a fun day. It’s more than stupid fireworks! Just listen to me!

Soulchild looks up at JJ. We can see and hear red and yellow fireworks going off in the distance. END.

inspired

by Tara Ballard “Animum Adverte”1. The person, of Nigerian immigrant heritage, is entirely disposable.

1.1 The person, of Nigerian immigrant heritage, is raised to further and protect the system which subjugates them.

1.2 The person, of Nigerian immigrant heritage, is raised to hate themselves.

1.2.1 They are told there is no such thing as a they, only he or she.

1.2.1.1 They are told that, loving who they love, is a sin.

1.3 The person, of Nigerian immigrant heritage, is raised to believe the Catholic Church and all its teachings are undeniably true.

1.4 The person, of Nigerian immigrant heritage, is raised to be conservative.

2. The person goes to Catholic School.

2.1 The person learns that their name is funny to white people.

2.2 The person learns about God and believes in it.

2.2.1 Well not really, but they don’t know religion is a choice, yet.

2.3 The person is accused of something they didn’t do, and learns a lesson for life, they will never be believed over white people.

2.4 The person doesn’t get that they are too different, too dark, too much to deal with.

2.5 The person wears a dress to school for opposite day, and all their classmates ask if they’re gay, but the person doesn’t know what gay means.

2.5.1 They’re ignorant by design. Their parents have been keeping that kind of content away from them, fearing it’d make them gay.

3. The person has a crush on a boy anyway, and doesn’t tell their parents.

4. They grow up, get over their old crush, and start high school.

4.1 They’re introduced to so many new ideas all at once, terms like transgender, non-binary, pansexual, and bisexual, become a part of their vocabulary.

4.1.1 They find the language to express themselves.

5. As they continue growing, they start to realize they don’t believe in anything their parents taught them.

5.1 They question why their parents thought it was wrong to be gay.

5.2 They question what it means to live in a body, if their gender can really be decided by one piece of flesh.

5.3 They start going by new pronouns on the internet, testing out how they feel.

6. Soon, they’re sure they aren’t a boy, at least not entirely.

6.1 They don’t tell anyone out of fear.

6.1.1 They learn to live through the internet.

7. They graduate from high school, and come to realize, they will eventually have to tell their parents something, about their identity, about their life.

7.1 At a barber shop, a man assumes they like women, saying they need a fresh cut to attract girls.

7.1.1 It bothers them, but they know it’s easier to say nothing.

7.2 They’ve said nothing for most of their life anyways.

7.3 They said nothing when their mother asked who they were taking to prom.

7.4 They said nothing when their mother tried to get them to date some random Nigerian girl they’d never met, but was a friend of a friend’s daughter.

7.5 They said nothing, and now they say nothing.

8. Sometimes they have dreams where they have different parents.

8.1 Parents who would accept them no matter what.

8.1.1 In their dreams, they tell their parents about every boy they’ve loved.

8.2 In their dreams, all their parents have to say is we love you.

9. Their dreams don’t last long enough.

9.1 And none of their dreams are coming true.

10. I am a first generation American of Nigerian heritage.

10.1 My dreams of acceptance, of love, of freedom, none of them are coming true.

When the common application asks you to write an all encompassing essay, you begin to question how well writing knows you.

How well you know writing.

How do you condense yourself into a word count, stuff your lungs, fold your chest, both your feet into the openings within each letter, how do you convince the invisible looming force that is the college board, the faceless adjudicator that is the admissions officer, that your brain deserves to be placed in a glass jar suspended in all the juices of learning, preserved like marble statue on their banner?

How do you explain your intelligence should be hand fed dining hall buffets and the sugar cookies of liberal art English classes, professor’s attention like vintage wines, like a seed begging to be quenched by a tenured man’s lecture, an egg warmed under the feathered belly of chalkboards and dissertations, place my head on a podium in front of a mic, kiss my mind but not pet it like the nose of a lap dog or maybe lap dogs, my cerebrum could be your lap dog

it would run circles for a bone, I’d roll over and bury myself within my learning, let me pay for my learning, let me unlearn the mud and dirt of uneducation, bathe me in caffeine addiction, let me prove to you I deserve to be trained, to be taught, let me demonstrate interest, like demonstrated need. Oh to glue my nose to the stained glass windows of your library or the floor of your mediocre dorm rooms my dad would even pay you, I would break open my own mouth and take out a loan just to pay you, satiate the zeros, the commas, the decimal points, one for each freckle on my mothers right arm. If money isn’t enough I will give you my body, every torn cuticle and back tooth, every song that has been stuck in this head, every word I have ever thought about stuffing in my personal statement.

This is my personal statement.

What happens when I have no more to give? How do I prove myself then?

What happens to the children that were never given anything to give in the first place. Must we beg for our rebirth? What price must we produce to label ourselves scholars?

Must we auction off our organs?

What if I was never taught this teaching was an option? What if my mind was never preened to begin with, never shown it deserves a jar or the prospect of suspension within liquid, what if we were taught out of that, what if we were pushed to hold tight to our own heads, to feed ourselves and keep our own bodies, shed our fur and shake the hands of the men who should beg for our intellect

Let the bleached colleges that preach diversity ask the rainbow kids to bless their floors, to paint their ceilings

give us shovels to dig up all the jars, all the stolen wit, pick axes to reshape the marble, allow our parents to rein habit their own sweat instead of drowning in it, paying both for nests and incubations as they relinquish their own birds.

This is my personal statement.

Let it stay suspended within your college campus, let it decorate your banners, let it blow like fall wind against the doors of your fine institution, let it sooth you but let it chill you too.

& when I open my eyes we are leaving. Fleeing east to greet the bleeding dusk, gone as its tendrils crawl forth. You are lucky & we move in blankets of bees how can one mass hold a million jolts? Two million breaths but not my mother’s & not the sister’s whose name I wear & still we ripple into the outskirts. Bodies— I guess that’s what we became when they forced pork down my mother’s closed throat. Your brothers & sisters weren’t lucky like you & we are leaving again, so I try to close my eyes but end up pressing the wind into lotus petals. I seal boxes of books that can never be read because you need to hurry & I wonder how that soldier aimed so slick his bullet danced through my uncle’s one cheek & clean out the other & somehow I know we are not going back. I untwist the waves from my hair. Miss the days I won’t remember. Wish my aunt would take me but no, no paper can buy back a revolution. This time when the harvest moon rises I know we really are leaving. I have a ticket past the shore as if the bodies aren’t dangling underside the train & off the rails & there now we are leaving fast skimming toward sea away from a sun so red I close my eyes.

INT. MYSTERIOUS ROOM - NIGHT

An OFF PITCHED WHISTLE can be heard in a dark room. The only things illuminated are a pair of LEATHER GLOVED HANDS, electric hair clippers, and the DECAPITATED HEAD of a woman with LONG DARK HAIR and an expressionless face.

The gloved hands mold the woman’s face, opening her eyelids to reveal her DARK EYES, relaxing her cheeks, and dragging down the corners of her mouth.

The whistling stops. The hands turn on the hair clippers. The buzzing sound is deafening.

Long strands of hair fall to the ground. LAST CREDIT APPEARS THEN FADES.

INT. FLOWER SHOP - DAY

MELLI - aged eight - opens the purple store front door. Her hair sits at her waist, and her white skirt drags on the green floor.

Above her, a series of chimes go off as the door hits a string of bells and hanging plastic insects.

Melli rocks from her heels to her toes while the bugs swing back and forth.

Everything is too bright.

Further inside, shelves of disembodied brown and grey HUMAN HEADS line the walls.

The heads are hollowed out, bald, and filled with various VIBRANT flowers- red, yellow, green, purple, blue.

Labels below the heads detail the flower species they contain and a small card describing their meaning. The shop is long and expands far down one large aisle.

Light on her feet, Melli wanders around the shop humming a soft tune beneath her breath.

She is the only one there except for the SHOP OWNER who lurks behind the cash register watching her. He is a lengthy man with small features reminiscent of a millipede. He wears a long orange apron.

Melli’s hum meets an abrupt stop when out of the corner of her eye, she spots a WOMAN’S HEAD exploding with yellow flowers on the bottom shelf.

The woman’s face holds an aloof expression. Her BLUE eyes gaze up as if she is trying to see the flowers within her. Her cheeks are pinched in at the sides making her lips wrinkled and puckered yet slightly agape.

Staring at the head transfixed, Melli kneels to its level as if she is about to pray, but instead, she runs her fingers along the concaves of the face then down the bridge of the crooked long nose.

For a moment, the head’s eyes seem to roll back into its skull.

Melli traces circles around the eyes and one large circle around the lips. Then, she mirrors the same actions on her own face.

There is a SIGN beneath the head reading: CHRYSANTHEMUMS - For friendship and good wishes.

A smile, lemon-rind-bright, spreads across Melli’s face. She gives herself a satisfactory nod and picks a singular flower from the head.

BLACKOUT.

The sun weathered muted yellow school bus drops off kids in a dirt patch right outside of a small neighborhood. Melli is already off the bus waiting. She holds something behind her back.

A scrawny LITTLE BOY hops down the steps and bolts past her.

MELLI

Hold on, wait for me!

The boy looks behind him and slows down, but he does not stop.

LITTLE BOY

Better catch up!

Melli starts sprinting with the chrysanthemum still in hand. A few petals fall on the dusty path leaving a bright trail behind her. She catches up to the boy, and they double over panting.

LITTLE BOY (CONT’D)

What’s with the flower?

Melli looks over at the boy who is now distracted by an ant carrying a dead moth over a rock. An ant hill waits on the other side of the rock, but the ant keeps having to stop because the moth is too heavy in its mouth.

When the ant begins to move again, the moth’s body is dragged against the rough stone making a microscopic scraping sound.

MELLI

(Hushed tone)

Um, it’s for you.

The boy makes eye contact with Melli.

Oh... cool.

LITTLE BOY

Melli hands the flower to the boy who tosses it back and forth in his sweaty hands.

MELLI

Do you like it?

LITTLE BOY

Did you pick it yourself?

MELLI

No, flowers like that don’t grow around here.

The boy holds the flower up to the cloud covered sky. His hands are small, sweaty, and stained with brown marker. Dirt hides beneath his bitten nails.

LITTLE BOY

It looks like the sun.

The flower droops slightly against its dreary background.

MELLI

Yeah, I guess it does.

They pass small old houses, old cars, and old creaking swing sets. The boy begins plucking slender petals off the flower. With each pluck, he dramatically tosses the petals to the ground.

LITTLE BOY

(Mockingly high pitched)

Love me, love me not, love me, love me not.

As the boy plucks the last few petals, Melli tries to catch them before they fall, but a sudden gust of dirt and wind blows them out of her hand. She turns away from the wind as the boy attempts to shield himself from it.

Melli’s long hair covers her face, and the two kids become drenched in dirt. Finally, the wind passes. Melli and the boy try unsuccessfully to dust the dirt off themselves.

The boy lifts his head to see his house across the street. A perfect full teeth smile gleams across his face.

The house is just as run down as the rest of them, chipping paint, a crooked roof, a fence with missing posts, and dead rosebushes that line the crumbling flagstone footpath.

Melli looks at the boy who has already begun to walk across the street.

MELLI

Where did the stem go?

The boy doesn’t turn around.

What?

LITTLE BOY

Melli pauses for a moment preparing herself to say something.

MELLI

Can I come over?

The boy unlatches the lock to his fence.

LITTLE BOY

I think your flower blew away.

Beside the rock, the poor ant is now curled up into a little black ball. Its mouth is gone.

The boy walks up the creaky wooden steps to his front door and waves goodbye to Melli. She droops like the chrysanthemum against the sky.

The boy steps inside his house with his back towards Melli, then abruptly shuts the door. She walks the rest of the way to her house alone.

INT. MOM’S HOUSE - DAY

When Melli walks through the door, her MOM is sitting down on a cracked brown leather couch with her feet propped up on the glass coffee table as she flips through channels on the television. Most of them are static. Melli crouches down by the welcome mat to untie her shoes.

MOM

How was school honey?

MELLI

One shoe is off.

It was fine.

MELLI’S MOM

Learn anything?

Both shoes are off. She places them beside the door.

MELLI

Yeah.

MOM

Well, that’s nice honey. I had a great day. Some lady won some money on that show. What’s it called again?

The T.V screen goes completely black, but a small message floats around the screen reading, NO SIGNAL.

MELLI

The Wheel of Fortune?

Melli’s mom flips over the remote, takes out the batteries, and clicks them back in. To her disappointment, there is still no signal.

What was that baby?

Nothing important.

INT. MELLI’S BEDROOM - NIGHT

MELLI

Everything in the room is dark except for the faint outline of Melli asleep on her back illuminated in a reddishorange glow coming from the blood red moon outside her window.

She sits up with her eyes slightly open. In slow small movements, she pushes away her covers and gets out of bed. For a moment, she fixes her hair and adjusts her pajamas as if she were looking into a mirror then cracks her neck in every direction.

Melli walks over to her closet and opens the door.

MELLI (Getting louder each time)

Mom... mom... mom

The slight purr of a heater and the sound of crickets can be heard. Silence.

MELLI (CONT’D)

(Yelling)

Mom!

Melli walks into her closet and shuts the door before pressing herself into the tight corner holding her knees to her chest for dear life.

She bangs her head against her knees.

The reddish-orange glow fades. Everything is dark.

INT. MOM’S BATHROOM - DAY

Melli’s mom stands by her vanity applying a BRIGHT RED LIPSTICK while staring at herself in the mirror.

A bright florescent light beams down on her making the highlights and shadows of her face extreme and artificial. After one coat of lipstick, she presses her chapped lips together, then puckers them to apply another layer. After four or so layers, the lipstick begins to clump becoming a red mess of lipstick, dried skin, and saliva.

Melli enters the bathroom and watches her mom watch herself in the mirror.

MOM

How did you sleep baby?

MELLI

Okay.

Melli’s mom smiles into the mirror, her teeth are caked with lipstick. She turns on her faucet, cups water in her hands, and brings it up to her lips.

She takes a mouth-full of water and swishes it around. When she spits it out, the water looks like blood.

MOM

Oh good, I had nightmares.

BLACKOUT.

INT. FLOWER SHOP - DAY

Melli - aged 45- Drags the balls of her feet on the green floor as she slugs around the shop. The hem of her long tunic style brown dress covers her heels.

Her gaze is down, but every so often, she glances behind her only to find the perky flowers staring back at her from all directions.

SHOP OWNER

Do you need any help?

Melli turns around and straightens out. The shop owner’s small, crooked smile makes her take a step back.

MELLI

I’m just looking around.

SHOP OWNER

No, you’re looking for something specific.

MELLI

I Well -

SHOP OWNER

You look like a little girl who used to come around here. Same face, but you’re a little thin.

MELLI

Well, this is my first time here. It just looked so... colorful.

SHOP OWNER

I’ll let you look around.

When the shop owner moves, Melli is immediately drawn towards the head behind him.

The head is plastered with dirt so thick, Melli can barely make out that it’s the head of a LITTLE BOY. His eyes are wide and joyful. He has a big yellow teeth smile.

The flowers that spill over the top look almost as if they are growing out of soil. The flowers themselves are little white caps; multiple hanging down each stem.

The SIGN beneath them reads:

LILLY OF THE VALLEY - Return to happiness.

Melli attempts to wipe the dirt off the boy’s face. She first tries with the sleeve of her shirt and then with her hands, but regardless of how much she wipes away, there are just more layers underneath. The boy’s smile seems to grow wider.

Melli collects the dirt that piled on the ground and presses it into her face. Then, she picks one stem of Lilly’s out of the head.

BLACKOUT.

INT. MOM’S KITCHEN - DAY

Holding her stem of valley lilies, Melli walks into her kitchen to see her mom repeatedly hitting her head against the wooden table covered in a GINGHAM TABLECLOTH.

Her mother’s clothes are mismatched, random, and wrinkled. Her shoulder length hair is soaked in grease.

Dirty napkins, rotting food, and ripped-open food wrappers litter every surface.

Melli gets a garbage bag from under the sink and begins to throw the trash away. Her movements are gentle and quiet. When she is done, she ties the trash bag shut and places it to the side.

She then wipes her hands on her dress and opens a wooden cabinet full of dusty glass plates. She takes one down and brushes it off with the sleeve of her shirt.

Over to the side of the counter, she opens a bread box. Out scurries a small cockroach from its tin cave. Melli takes out two slices of white bread and puts them on the plate.

Finally, she rinses off a butterknife in the sink and cuts two pads of butter from the dish on the counter. There is a faint scraping as she spreads the butter on the bread.

Plate in hand, she walks over the table and sits in the chair beside her mom. When her mom raises her head, Melli puts her hand on her forehead before she slams it back down on the table.

Melli’s mom lifts her head, looks at Melli, and attempts to form her lips into a slight smile. It doesn’t work. Melli pushes the plate of bread closer to her mother.

MELLI (CONT’D)

Please try to eat with me. Her mom stares at the plate without moving a muscle.

Melli takes a deep breath and picks up a piece of bread holding it to her mom’s lips. Her mother takes a bite. Melli then takes a bite of her own bread.

She continues to feed her mom then herself until both pieces of bread are gone.

Melli gets up from the table, fills a mason jar with water, puts the valley lilies in the makeshift vase, and places it on the table.

The cockroach has found a new place to rest in the shadow beneath the cabinet.

Her mother rests her head on the table taking long drawn-out breaths.

Melli’s WIFE waits in her tan car as Melli walks out of her mom’s house.

The dirt driveway is full of dead bushes and tumbleweeds. Goat-heads stick to the bottom of Melli’s black shoes.

She gets in the car.

Melli’s wife turns down the radio. The music is now a constant low hum.

MELLI

It’s hot in here.

WIFE Is it?

MELLI (softly)

Yeah.

WIFE

I could turn on the air conditioner.

MELLI (Shaking voice)

It’s broken.

Melli rests her head in her hands.

WIFE (whispers)

I’m sorry.

MELLI For what.

WIFE

I know you’re not okay.

Melli turns red, begins to shake then breaks into sobs.

Her wife unclicks her seat belt and awkwardly leans across the center console to wrap her arms around Melli. Melli relaxes into her chest.

Melli and her wife sit together on a dingy wooden porch swing that creak while slightly rocking.

Melli’s wife traces circles into the back of Melli’s hand while she looks up at the sky.

Her bright blue eyes gleam against the brownish grey clouds. Melli watches the ground.

WIFE

You don’t have to feel bad.

Melli fixates on a praying mantis as it slowly roams around a bush.

WIFE (CONT’D)

Hello?

The praying mantis stands still.

Above it, a bee looks for something to pollinate.

With its claws waiting in the air, the mantis begins to delicately rock as the bee buzzes closer.

WIFE (CONT’D)

It’s okay you cried.

MELLI

Love, I don’t want to talk about it.

WIFE

So, are we just going to ignore it?

Melli squeezes her wife’s hand and tries on a fake smile.

MELLI

I’m not ignoring anything.

WIFE

Don’t lie to me. (beat)

Melli’s fake smile fades.

How is your mom?

WIFE (CONT’D)

Melli takes her hand away, stands up, and begins to walk away without even looking at her.

MELLI

I’m not lying.

In one swift motion, the praying mantis catches the bee. It brings the helpless creature to its mouth and slowly consumes it.

The wife drops her head.

BLACKOUT.

INT. FLOWER SHOP - DAY

Melli -aged 75- enters shop. Her face has sunken into itself, and the skin around her cheeks droop down like melted wax. The dark purple circles around her eyes make her look eternally tired.

With careful steps, she takes long breaths holding each one at the top until she becomes lightheaded and is forced to exhale.

The lights in the store are white and glaring. Melli repetitively closes and opens her eyes as if she is trying to squeeze a headache out of her head.

She stops walking as florescent colors flash around her like the edge of a slashing blade.

Something, or someone is whispering. The sound surrounds her, but the words are inaudible.

Melli frantically tries to look around, but the noise comes to a halt.

She begins to walk again, but there are footsteps trailing behind her. She turns around, sees the shop owner, and screams.

The shop owner stands still and smiles so wide, his mouth barely fits on his face.

SHOP OWNER

Are you okay ma’am?

Melli can hardly hear him over the sound of her own quick struggling breaths.

MELLI

I was just, uh, looking around.

SHOP OWNER

Sure, you are.

Melli looks past the shop owner’s shoulder.

MELLI

I’m looking for a funeral.

SHOP OWNER

Do you know what their favorite flower was?

Melli squints.

MELLI

Is this shop new? It seems... bright.

SHOP OWNER

Did they have a favorite color?

Melli concentrates on the head of an OLD WOMAN with a long-wrinkled face and red flowers.

MELLI

She could never pick one, but I think she liked red.

SHOP OWNER

Well, there is plenty of that here. I’ll just let you have a look.

Melli continues to stare at the head, but when she refocuses to respond to the shop owner, he is already across the shop dragging his feet as he walks.

She looks back to the head of flowers she was fixated on and walks closer.

The head’s mouth hangs open as water puddles on it’s grey tongue. The head’s teeth, lips, and entire bottom half of face are bright red.

The glowing red flowers inside have pitch black centers. The sign beneath it reads:

POPPIES: ETERNAL SLEEP

Melli reaches out to the head and drags her bitten nails across its red chin. The red gets beneath her nails. White streaks of skin are exposed where the red was scraped off.

She continues to scratch the face until all of the red is gone, but the skin beneath becomes irritated, and red all over again.

She then drags her nails across her own face in one long motion.

Her nails are too short to break skin, but eight bright red lines run down her face.

She picks one poppy out of the head. Then she picks another, and another, and another. All of the poppies begin to look like fire within her hands, and she treats them as such.

She drops the flowers, and all of the poppies fall to her feet but one.

The petals look like little dying flames on the ground. She begins to cry hysterically. BLACKOUT.

The church is long and dark. From the entrance, Melli and the casket she stands next to look small and insignificant at the front of the church.

Closer up, almost everything is black including Melli’s dress, the lighting, and the empty church pews. Inside the casket, Melli’s wife lays dead with her grey hands at her sides. A white sheet covers her body, and a black scarf obscures her face.

There is no priest.

Poppy in hand, Melli looks down at her wife. Or rather, the covered body where her wife should be.

BEGIN FLASHBACK:

INT. MORGUE- DAY

A STRANGER’S hand gently closes Melli’s wife’s eyes as she lays on a sterile white sheet atop a hard bed.

Melli’s deep breathing from the flower shop scene can be heard.

END FLASHBACK.

INT. CHURCH- DAY

Melli tucks the poppy beneath the corner of the black scarf covering her wife’s head.

MELLI (Crying) Where did you go? Where did you go? Where did you go?

Silence.

MELLI (CONT’D) (Getting quieter each time) I’m not okay, I’m not okay, I’m not-

Melli falls to her knees.

MELLI (CONT’D) (Whisper) Okay.

Silence.

The green poppy stem peaks out from under the scarf. Melli kneels at the side of the casket. The church is empty.

Inaudible whispering begins. Melli attempts to cover her ears, but the sound fills her mind as the whispering becomes increasingly louder.

Melli walks over to one of the church pews leaving the casket open.

She sits down, the whispering stops, and the church pew creaks. Melli looks over to the casket.

MELLI (CONT’D)

Do you know where you are?

MELLI (CONT’D)

Do you know what was whispering?

MELLI (CONT’D) Was it you?

MELLI (CONT’D)

The same thing happened in a dream. Maybe-

MELLI (CONT’D) it wasn’t a dream.

MELLI (CONT’D)

I don’t know where I was.

MELLI (CONT’D)

I think I’m becoming paranoid.

MELLI (CONT’D) Love?

MELLI (CONT’D)

I don’t know where everyone is.

The whispering starts again. Melli hits her hands against her ears.

MELLI (CONT’D) (Yelling)

Where are you? Where are you? Where are you?

Melli attempts to drown out the whispering with a scream, but everything only gets louder.

EXT. PORCH SWING - DAY

Crows caw on a white tree as Melli sits alone. Her long-sleeved black shirt flows onto her long black skirt which hangs down the swing and puddles on the ground.

She cries but does not cover her face. Instead, she wraps her arms around herself and slowly rocks. Back and forth, back and forth.

The tears stream down her face and slowly drip down her neck.

Her breath trembles, and she occasionally chokes on the air. She sounds like another crow.

The crows fly onto a new tree. Their wings are loud against the wind; the sky is still grey.

Melli holds herself tighter and rubs her shoulders as if she were cold.

The crows settle in another tree, and finally, still holding herself, she calms her breath to a steady slow inhale and exhale.

Tomás got her name from her grandmother’s dream. Or it was from the nice man who helped her father reach the hospital when her mother gave birth, or it was because of her aunt’s dear dead friend. Anytime she’d tried to ascertain where her name might’ve come from—from anyone in her family— a different answer seemed to arise. Most often, the agreed upon truth was that she had arrived in the world, and the name had bestowed itself upon her, without warning or cohesive explanation. It was an adopted name of a doubtful apostle and an ancient gospel writer, an old Catholic name, one derived from Spanish scripture translation: Tomás, a name that meant twin.

Where her extended family was full of cousins and multiple siblings, Tomás was born the first and only child to her mother and father. She was born quiet, her mother would tell her, born with open eyes and refusing to scream or cry.

“Your father’s mother,” her mother insisted wryly for years, on the topic of the same grandmother that had dreamt her name, “wanted to take you down to the Rio Grande for baptism, said the pushing waters would wake you right up to yell.”

Her father denied this, with something of a grin, as if it was a larger joke, set up long before Tomás was even named, and her grandmother staunchly refused to comment on the matter. Tomás, despite her birth, was not a quiet child, as all would attest; she shrieked and chattered and was obsessed for several years with a variety of old movie monologues, reciting lines when she saw fit. There was always something a little odd about her, cataloged in report card notes and the testaments of her parents, friends’ parents, the cashier at the local grocer. She was always a little off kilter, smiled a little crooked, always seemed a step out of tune with the world around her. And though she lost her fervor for speaking in her teens, the oddness never faded. A gleam, a worry—a twin, alone without any other.

Tomás spent most of her young years in the garden with her grandmother, particularly during the weekends and summers when her parents were working and she had little else to do. Sometimes her grandmother would demand they both rise before dawn so that they’d beat the sun to the garden. Whenever Tomás tried to complain about the hours, her grandmother would shush her, insisting it was necessary to avoid the weight of the hotter Julys. But Tomás always suspected it was also a forced sort of bonding, just the two of them outdoors to watch as the sky turned pink in silence. Her grandmother had helped with the work initially, but as soon as she had deemed Tomás fully capable, she began to direct Tomás from her seat on the porch, speaking to her loudly about very little and everything else.

Tomás knew that garden better than she knew anything else—knew the smell of the dirt and how it always wedged up beneath her fingernails, knew the family of frogs that lived in the half-upturned brick by the stairs. Knew where the sweet potatoes would inevitably reappear, splitting the earth in the yard’s eastern corner to disrupt whatever else had been planted that season. This garden was where she grew best, nestled between the summer rains and the crape myrtle her father refused to have trimmed, as he claimed it would never return if cut.

One late summer month when Tomás was twelve, her grandmother woke up past noon, and they did not go out into the garden until the sun was heavy in the sky, taking on an almost hazy orange. That day, her sweat stung hotly on the nape of her neck, and the residual taste of lime from her recent lunch sat heavy on the back of her tongue. Her grandmother didn’t speak much once they were out in the garden, just watched the sky. No

directions were shouted out, and she didn’t even yell when Tomás stopped working and came to sit by her. Her eyes were focused far off, studying something Tomás searched for but couldn’t find. Instead, Tomás watched as a ladybug began to travel up her grandmother’s hand, the slow red dot skittering higher and higher, her grandmother unmoving all the while.

“Tomás…”

“Hm?”

The sentence wasn’t continued. A few yards over, Tomás heard a door open, then slam shut, a holler about the heat just barely audible. Her parents were at work, and the house felt too quiet, even from out on the back porch. She pushed back in her chair, tipping it carefully until her head knocked against the siding with a dull thud, toes barely keeping contact with the ground.

“I didn’t want your name to be Tomás. I dreamed it—” a small, shuddery shrug “—maybe. But I didn’t want it to be your name, at least your first. I always thought you’d be named Messiah.”

“Messiah?” Tomás didn’t say it sounded ridiculous, though her grandmother must’ve known she thought so from her tone. Still, she didn’t raise her arm to slap Tomás’s head. There was not even a reprimanding look thrown her way. The ladybug continued its path upwards, undisturbed.

“Yes. It was your grandfather’s middle name, an important one. He always...”

Her grandmother trailed off. Tomás hadn’t ever known her grandfather. She tilted forward until her feet pressed flat against the deck, and the wood groaned at the change in weight. Tomás didn’t prompt her grandmother to remember, just surveyed the pot of angelonia near her feet, still in full bloom. Really, she should move it off the porch soon so it would get more direct sun.

“It would’ve been a good name for you. Would’ve fit,” her grandmother then added after a stretch of silence.

“Really?”

Tomás let her head fall to the side. The ladybug had reached her grandmother’s face, and it crossed slowly over her cheek into the curve of her eye socket, slowing down just at the corner of her lashes. Her grandmother nodded slightly, then sighed, closing her eyes; at the movement of her eyelid, the ladybug finally took flight, fluttering out from the porch and towards a high horizon. A harsh beam of sun interrupted Tomás’ tracking of it, and she shielded her eyes with irritation. From next door, the sound of a lawnmower roared to life, and Tomás grimaced. That was enough for her.

“Well, you’ll have to tell me some other time,” she said. Then she stood, patted her grandmother’s hand, and returned inside to the solemn quiet.

For the first two years of high school, Tomás walked home from the bus stop with the same kind-of-friend, who lived about half a mile east of her. They never walked together in the morning—Tomás guessed that he carpooled with his older brother, who attended the same school—but they always ended up together in the afternoons, sometimes making small talk, sometimes in amicable silence. He was shorter than her by maybe an inch or two, and they both tended to wear the same pair of shoes, black Converses beaten to hell and stained with mud. He’d sewn a small patch onto the heel of his left sneaker, a pale denim star probably cut from old jeans. His name was Mitch. That, in total, was about all Tomás knew about him, despite the months and months they had walked home together every school day afternoon, careless beneath the always boiling sun.

“Do you have plans for after senior year?”

Tomás tripped slightly over her feet. They were five minutes into their fifteen-minute walk, nearing the Shell gas station. She had been considering asking if he wanted to stop to pick up drinks; it was truly a hellish May day. Maybe a Gatorade, maybe an iced tea—sweet.

“Not really.” Maybe. Sort of. “Maybe go off to college. Maybe go to work, I’m not sure. It’d be nice to travel a bit, even just in state.” A moment. “Why?”

“Well, my brother’s leaving for college soon. Made me think about it. I just have short term plans.”

“What kind?”

They’d accidentally fallen into the same rhythm of step, right feet hitting the pavement, left ones moving forward in symphony.

“I want to go down farther south to near the border, work in a park or conservatory maybe. My brother and I used to go with our aunts down to Rio Gran’ on trips, camping or just day wandering. I always just liked the area.”

“Can’t wait to get out of Amarillo?”

“Shit, of course.”

They stopped at a corner, waiting for the light to change. A shiny sedan screeched by, making a hard turn to the right, and they both flinched back from the curb. The green Corolla turned half-way from the parking lot into the same lane and laid on the horn. Mitch pressed the crosswalk button, though they both knew it never worked.

“It’s funny, my grandmother always wanted to go down to the Rio Grande with me. Allegedly for a baptism to make me speak. I was a quiet baby.”

“Did she ever follow through with that threat?”

“Never had the right time. But maybe it’s a good idea.”

“A second baptism?”

She smiled a bit. The light turned, and Tomás set out first, Mitch matching her stride again without effort. They were now about two minutes from the gas station. Tomás didn’t think she’d have the courage to ask to go get drinks.

“No? I don’t know? I’m not all that sure. It just feels like the place to go, to honor her memory, figure something out.”

“It sounds like a good trip.” Thirty more feet. Around the next corner was the gas station. “Do you want to stop to get a snack at the Shell? My treat.” This was unfamiliar. She blinked at him. But not unwelcome.