4 minute read

Age Limits versus Ageism

ate last month just after announcing her run for President, former South Carolina Governor and UN Ambassador Nikki Haley opened a can of worms when she proposed that politicians over the age of 75 be required to undergo a competency test. Under the proposal, Haley, who is just 51, would not have to prove her competence, even though she once excoriated Trump for not disavowing White supremacists, then willingly accepted a position in his administration. Seems like an opportunistic, brown-nosing hypocrite with poor judgment should be required to take a competency test despite her age. But I digress.

Haley’s proposal came on the heels of President Biden reporting for his annual physical. Uncle Joe is now 80 years old, and if he wins a second term, he’d be 82 at his inauguration and 86 when his successor is sworn in. Biden passed the physical with flying colors, but his increasingly slurred speech, forgetfulness, and slow gate are becoming more and more of a concern for Democratic strategists who worry that their leader might not be up to the rigors of another campaign.

Advertisement

Surprisingly, one thing Ms. Haley has not yet suggested is an Amendment to the Constitution that would establish maximum age limits for anyone serving in an elected federal office. Such an Amendment would be consistent with existing law. After all, the Constitution already requires a minimum age for serving in Congress (25), Senate (30), and President (35), so why not establish a maximum age for each? Moreover, unlike subjective competency tests, which could be open to interpretation, maximum age limits would be clear-cut with no shades of gray hair. Still, this kind of Amendment would, no doubt, be vigorously opposed by the same folks who oppose term limits. Their belief is that voters should have the right to re-elect whoever they choose and that any sort of limit on terms or age would circumvent that right.

LSuch a libertarian view of politics is all well and good in theory, but not when it adversely impacts the rights of others. For example, because there were no term limits or age limits in Congress, South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, an avowed White Supremacist, was allowed to serve until his death, at the age of 100. On the flip side, despite advancing age and serious health problems, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg refused to retire at a time when President Obama could have appointed a like-minded civil rights champion to succeed her. Instead, she died in office at 87 and gave Trump a clear path to pack the Court with right-wing, activist judges. Roe v. Wade advocates are probably wishing that term and age limits had been in place years ago.

Of course, any discussion of age limits invokes fears of ageism. That’s why in 1967, Congress passed the “Discrimination in Employment Act,” which prohibited companies from forcing someone to retire who still wanted to work past 65. The Act did, however, allow for exceptions to the rule, such as mandating retirement if an employee could no longer effectively perform his or her job. And that brings us back to Nikki Haley’s proposed competency tests for politicians over the age of 75. If those tests could be administered fairly and objectively, and if an elderly candidate couldn’t make the grade, then that’s something the public needs to know before they go vote. Whether or not the results of such a test should automatically disqualify a candidate, however, is another matter altogether. That’s why, in the end, establishing term limits or maximum age limits (or both) for federal office holders would be preferable to Haley’s flawed testing scheme. !

JIM LONGWORTH is the host of Triad Today, airing on Saturdays at 7:30 a.m. on ABC45 (cable channel 7) and Sundays at 11 a.m. on WMYV (cable channel 15) and streaming on WFMY+.

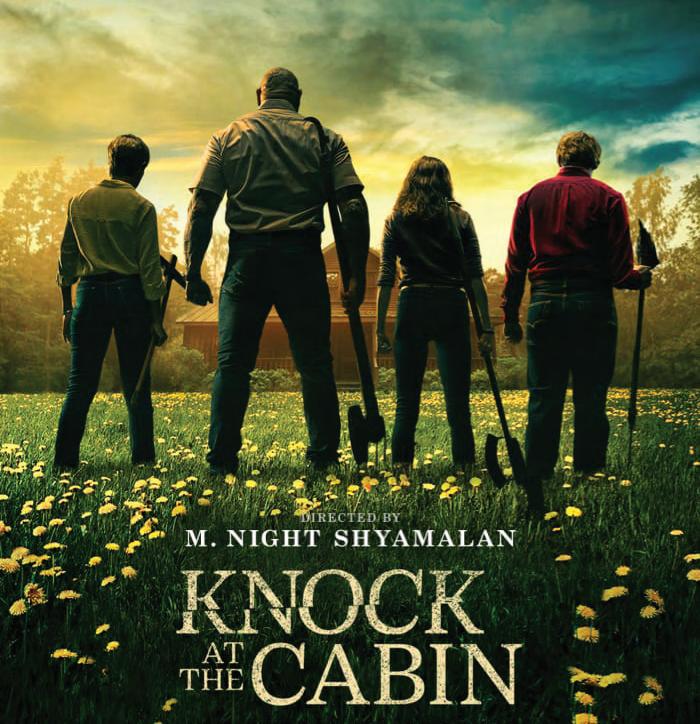

he curious case of filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan continues in Knock at the Cabin, the screen adaptation of Eric Tremblay’s best-selling novel, which Shyamalan produced, directed, and shares screenplay credit with Steve Desmond and Michael Sherman. Deemed by some as Shyamalan’s “comeback” — although he’s never been away — it is neither the best nor worst of his frequently, maddeningly uneven output.

Most are confined to the titular enclave situated in the woods of Pennsylvania, where little Wen (delightful newcomer Kristen Cui) is collecting grasshoppers when she is approached by Leonard (Dave Bautista), an enormous but unfailingly polite man who informs her that he and his friends need to speak with her parents. He also tells her that they won’t like what he has to say.

Indeed, Andrew (Ben Aldridge) and Eric (Jonathan Gro ) are thoroughly displeased, to say the least, when Leonard and his cohorts (Nikki Amuka-Bird, Abby Quinn, and a jittery Rupert Grint) break into their cabin and hold them hostage. Andrew and Eric are initially convinced that they have been targeted because they’re a same-sex couple, but Leonard assures them this is not the case.

The intruders have each experienced horrific visions of an impending apocalypse and are convinced that Andrew and Eric must willingly sacrifice one or the other — or Wei — lest the world comes to a catastrophic end. To prove their “theory,” they simply switch on the television and watch as a series of natural — and seemingly supernatural — disasters rock the world. The allusions to the COVID-19 pandemic are inescapable, especially since calamity facing humanity is an airborne virus. Another is an enormous tsunami caused by underground earthquakes o the Pacific coast.

Still (understandably) skeptical, Andrew and Eric are faced with the ultimate existential dilemma. If that weren’t enough, Leonard and the others are compelled to sacrifice themselves

Tat periodic intervals. They are meant, of course, to represent the Four Horseman of the Apocalypse, which the viewer realizes long before the onscreen characters do. Therefore, one can surmise, that Andrew, Eric, and Wei are meant to represent some kind of holy trinity.

Whatever higher — or lower — power is responsible for the apocalyptic goingson is never made clear, nor need it be. In essence, Knock at the Cabin is a gimmick movie, which makes it supremely suitable for Shyamalan, who specializes in gimmick movies. It’s not as self-indulgent or overlong as some of his earlier films, which is certainly in its favor, and his obligatory cameo appearance is just that — a brief (and amusing) walk-on. And, as his “end-of-the-world” movies go, Knock at the Cabin is at least superior to Shyamalan’s The Happening (2008) and After Earth (2013).

The ensemble cast performs competently, with each actor having a Big Moment (usually it’s their last moment). There are flashbacks designed to flesh out Andrew and Eric’s relationship, but they are awkwardly inserted and tend to interrupt the story’s momentum. The film is understandably talky, even theatrical, and at times plays like a warped version of group therapy. It’s suspenseful but not particularly scary, and although Knock at the Cabin is R-rated it’s not especially or excessively gory. !