Communicating Gender

Ecumenical Journal , 2012/Gender

World Student Christian Federation Europe Region

29

Mozaik (established in 1992) is the ecumenical journal of the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF, 1895) Europe Region, published two to three times a year. It aims to reflect the wide variety of opinions and viewpoints present among the different Student Christian Movements (SCMs) in ecumenical dialogue. You can find us Online at www.wscf-europe.org.

This issue of Mozaik follows the WSCF Europe gender conference “Communicating Gender: Gender Identities in a Globalised Europe”, which was supported by the European Commission, the European Youth Foundation of the Council of Europe and our Danish partners (Studentermenighede i Aarhus, Vandborg Menighedsråd, Roskilde Mellemkirkelige Stiftsudvalg, Aarhus Mellemkirkelige Stiftsudvalg, Haderslev Mellemkirkelige Stiftsudvalg, and Dioceze). WSCF Europe also receives support from several other church related agencies and from the General Budget of the European Communities. The contents of this publication reflect the views only of the authors, and not the opinions or positions of WSCF as a whole, the editorial board, the Council of Europe, the European Commission, or the other donors and church-related agencies. Neither the European Commission, the Council or Europe, nor the other donors can be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Editor-in-Chief:

Paweł Pustelnik (Cardiff, UK)

Editor:

Jill Piebiak (Alberta, Canada)

Art Editor:

Maria Bradovkova (Slovakia)

Address:

Storkower Straße 158 #710 D-10407

Berlin, Germany

ISSN 1019–7389

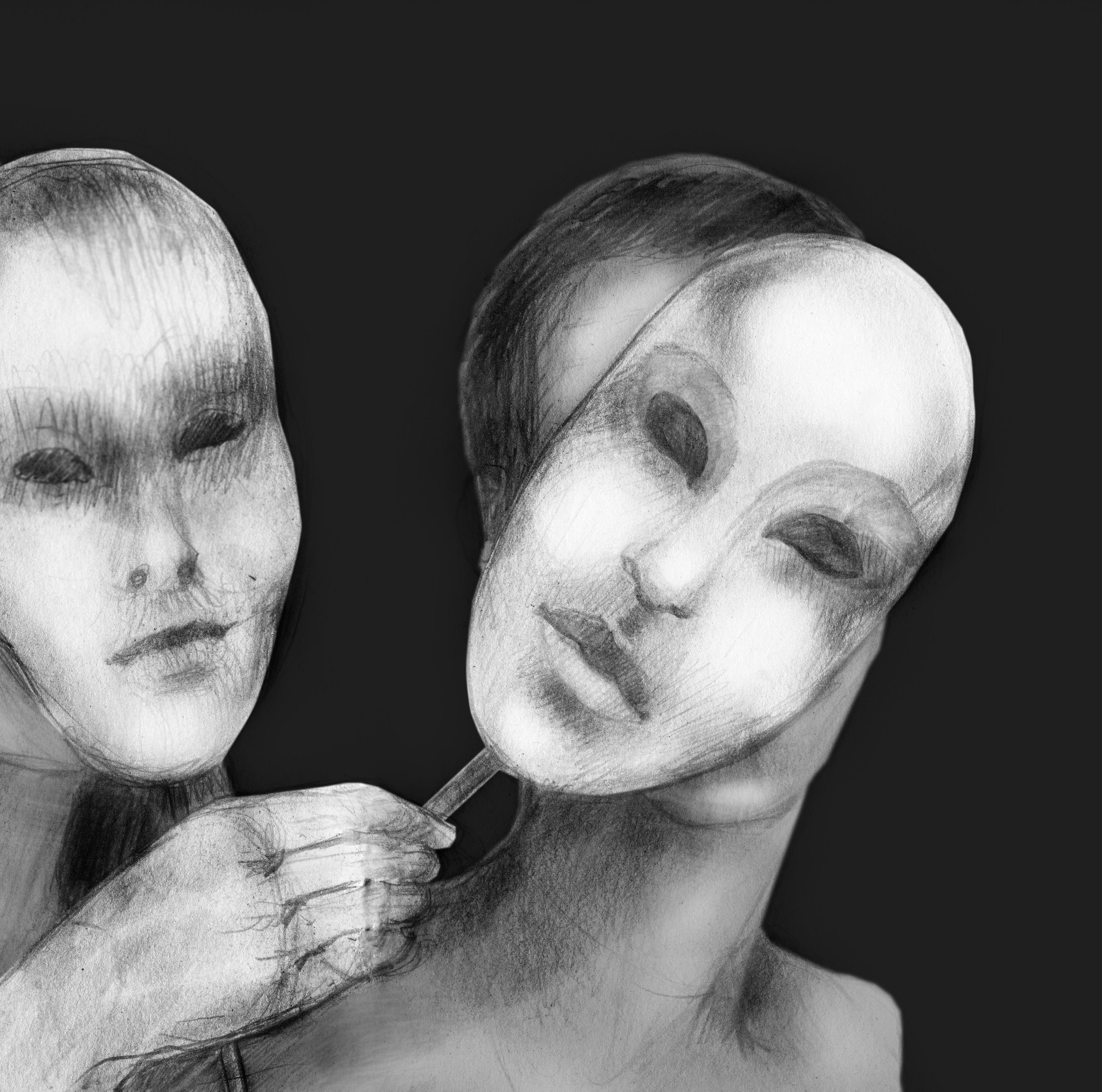

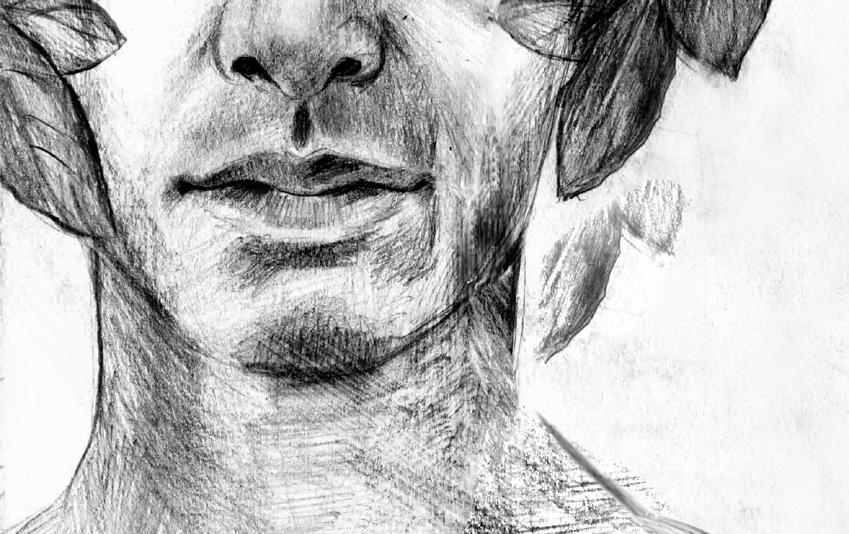

Illustrator:

Maria Bradovkova (Slovakia)

“I find it ridiculous to assign a gender to an inanimate object incapable of disrobing and making an occasional fool of itself.”

― David Sedaris, Me Talk Pretty One Day

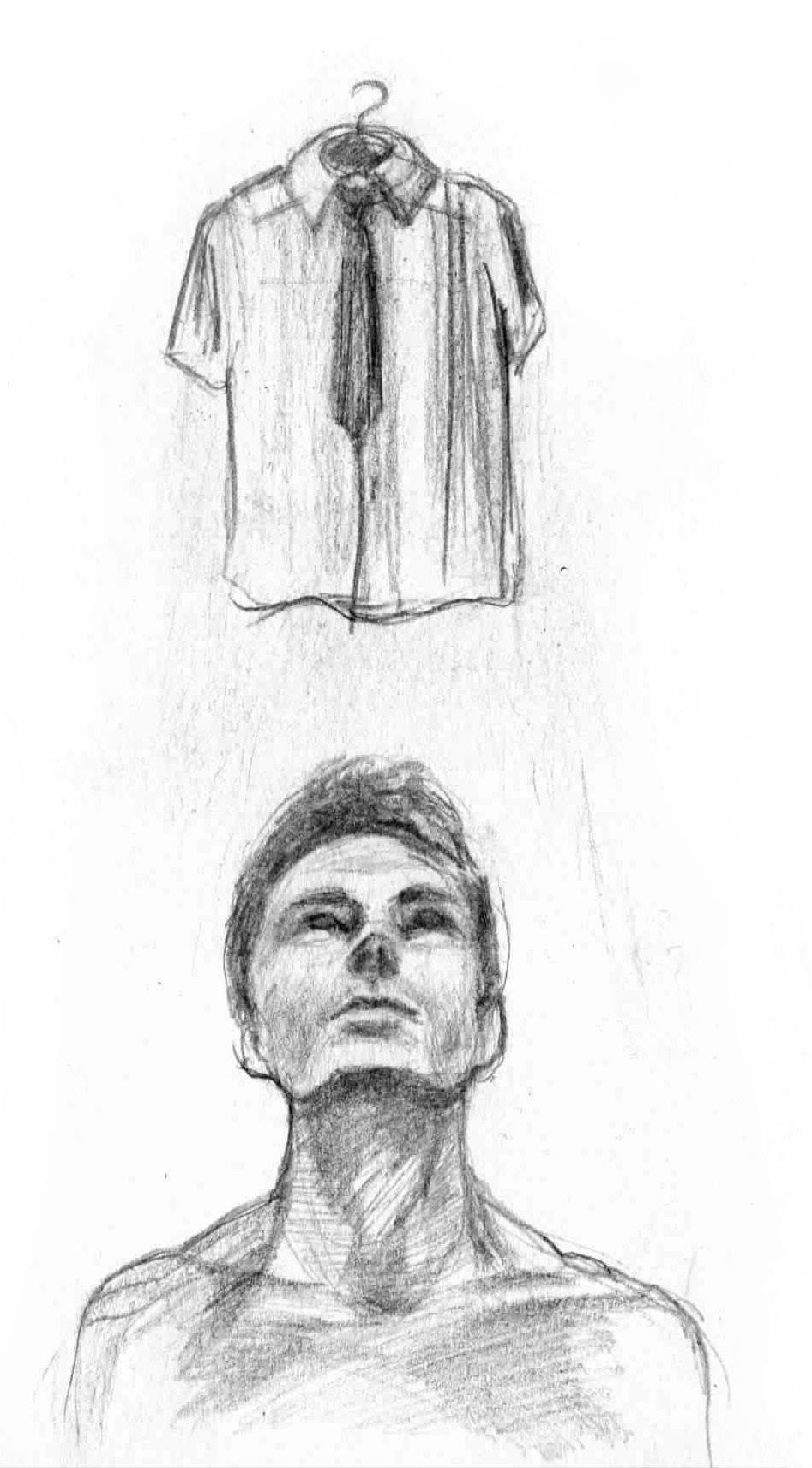

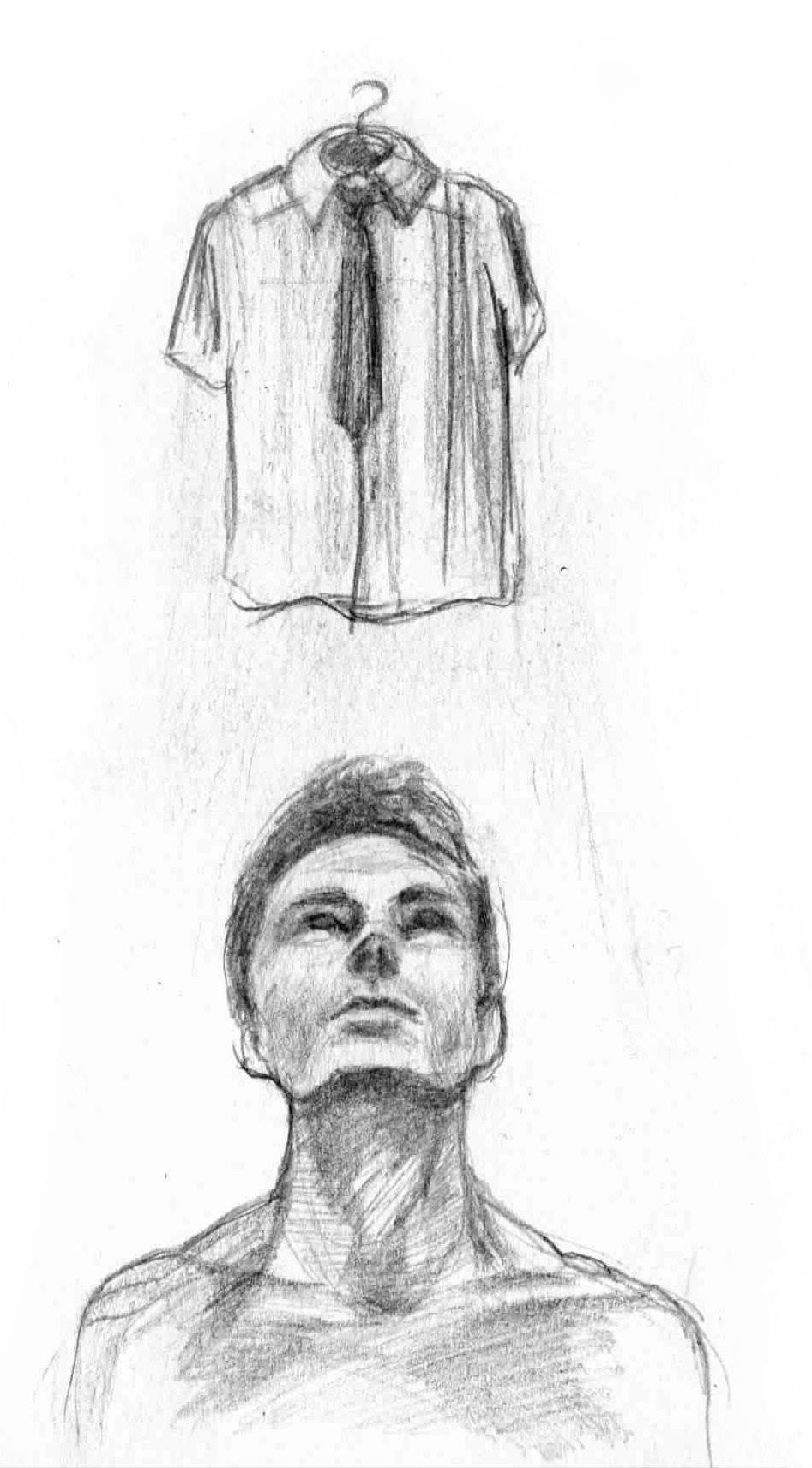

“... that gender is a choice, or that gender is a role, or that gender is a construction that one puts on, as one puts on clothes in the morning, that there is a ‘one’ who is prior to this gender, a one who goes to the wardrobe of gender and decides with deliberation which gender it will be today.”

― Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

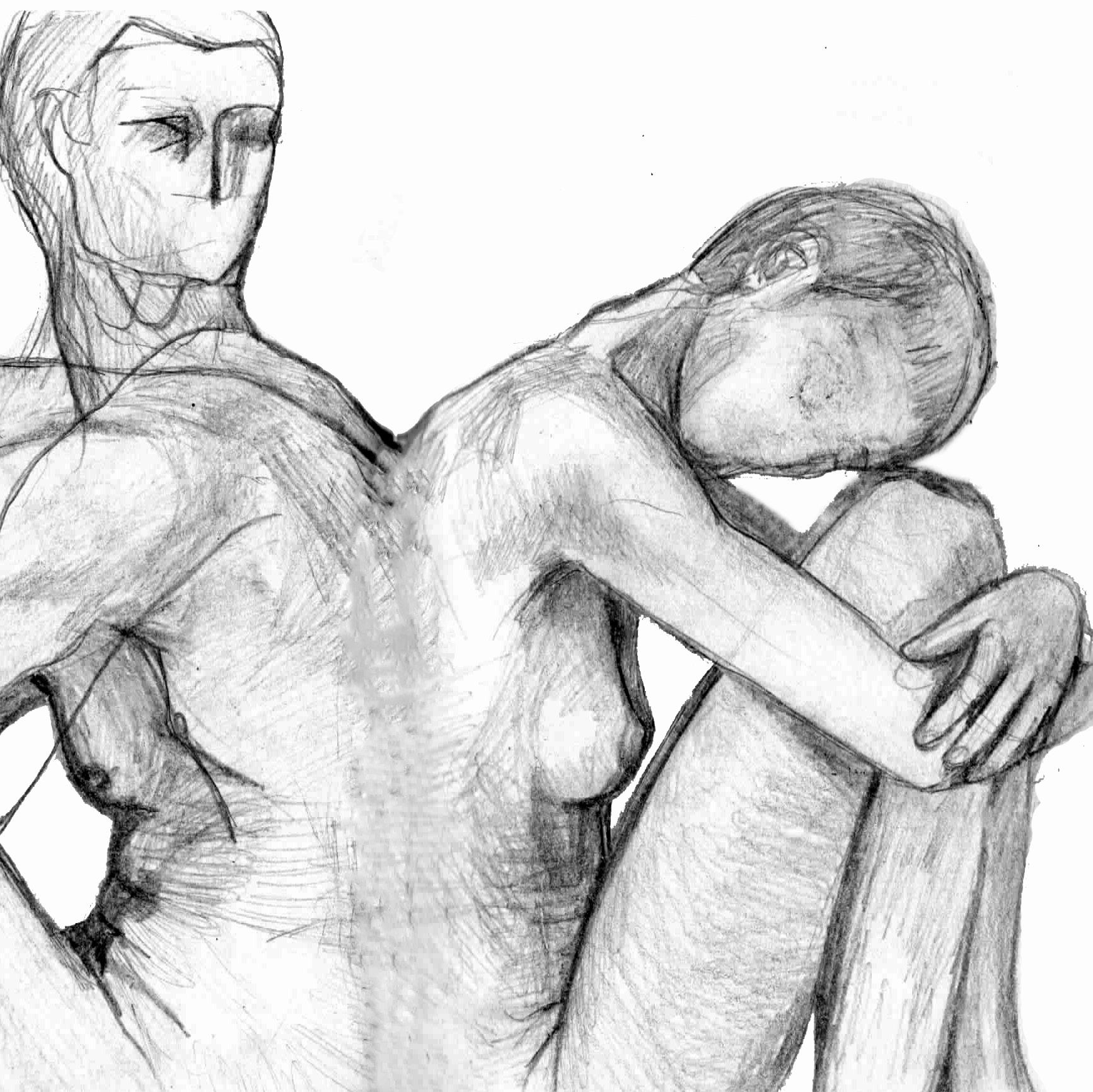

“Life for both sexes—and I look at them, shouldering their way along the pavement—is arduous, difficult, a perpetual struggle. It calls for gigantic courage and strength. More than anything, perhaps, creatures of illusion that we are, it calls for confidence in oneself.”

― Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

“War is what happens when language fails.”

― Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride

1

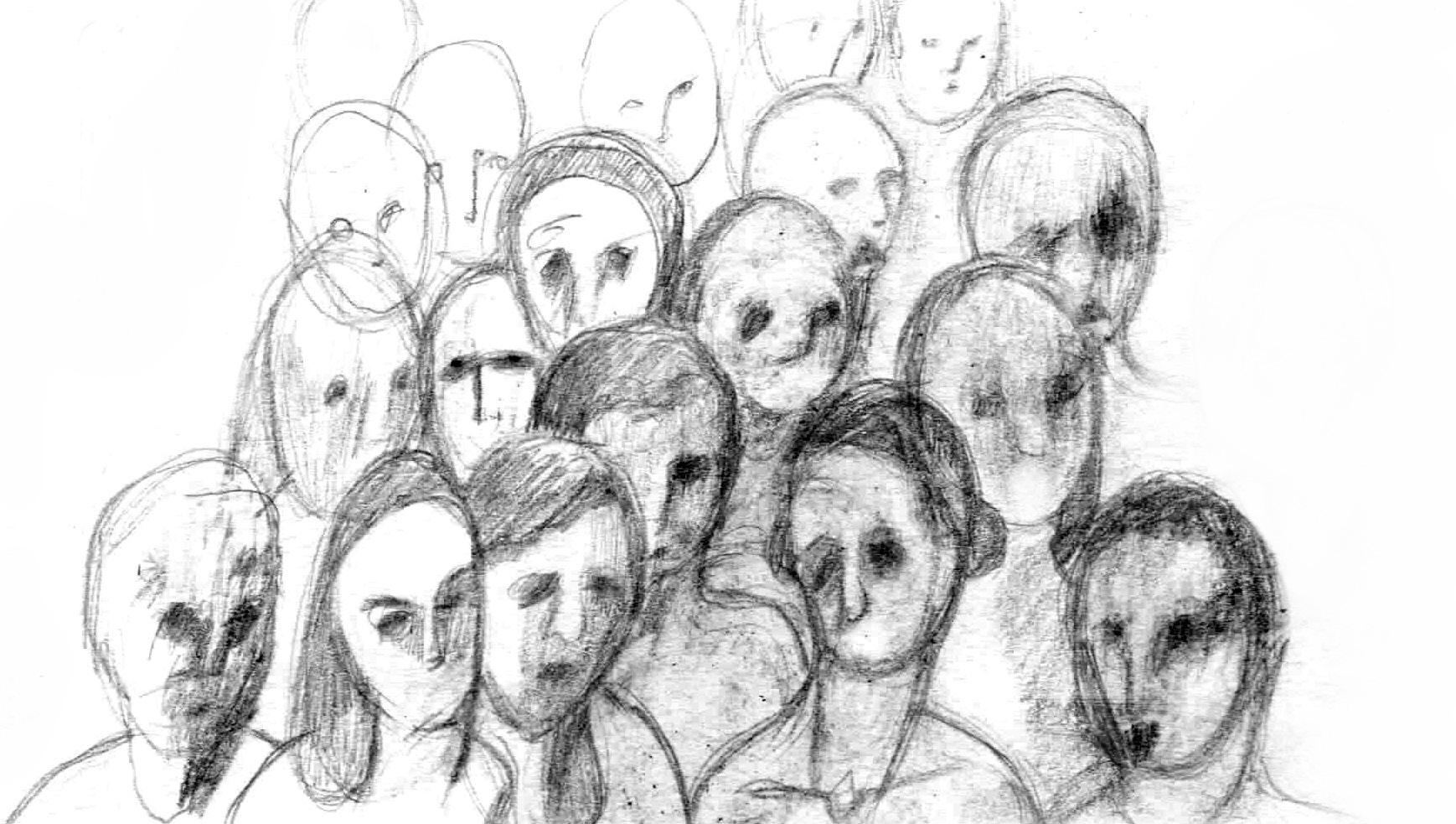

OFTEN words do not come easy and gestures are more natural. However, usually we communicate through language and it is the measure to express our thoughts.

In this issue of Mozaik, we have been trying to show the diversity that every language offers to its users. The possibilities but also the traps that we experience in a gender sensitive reality can be found everywhere. When you try to add a religious component to that uneasy setting, language becomes a powerful tool. That is why we wanted to share more reflexive pieces and wonderful poetry by Steven Canning and Marta Gustavsson. Sometimes it is just easier to turn towards creativity to convey a message that a multitude of words would blur.

Sadly enough, language is often used as tool of manipulation or violence. The ‘hatred pollution’ in language reaches unprecedented levels and often the only opposition is political correctness or silence. As young Christians, witnesses and agents of change, we are the ones who need to oppose those tendencies. This resistance is a universal principle that can be implemented with a spirit of solidarity in each and every place. The empowerment that language gives is an instrument that is to be used for affirmative defence against the death of positive communication.

I am privileged to express my gratitude to Miklós Szalay who has been Mozaik’s Art Editor for the last eight years. His creativity and patience have been always impressive. I am happy to say welcome to Maria Bradovkova who has been selected as the new Art Editor. As you can see, we decided to freshen up the layout. Yes, spring is just around the corner! Last, but not least, from now on, you can read and comment the articles that are published on paper also Online at www.wscf-europe.org. Make sure that you share those you like the most!

|29 2

EDITORIAL

THE ESCHATOLOGICAL CLOSET

Marta Gustavsson

SHE, ALPHA MALE

Stephen Canning FROM THE ARCHIVES

Eva Danneholm

A BABY NAMED STORM AND THE CASE FOR A NORMATIVE PATTERN FOR GENDER

Nick Schuurman

IS GOD A ‘HE’ OR A ‘SHE’?

JoAnne Lam

MY FAITH, MY GENDER

Kathy Galloway

HOMOEROTICISM AND THE BIBLE: TIME FOR A FRESH APPROACH

Kjeld Renato Lings

WOMEN AND THE 16TH CENTURY

Jens Christian Kirk

AN UNCONVENTIONAL BIBLE STUDY

Martin Bonde Christensen

MY FAITH, MY GENDER: A CONVERSATION

Kathy Galloway

A BIBLE STUDY ON GENDER

Dzmitry Bartalevich

WOMEN’S ROLE PATTERNS IN FAIRY TALES:

“HOW DOES CINDERELLA FIND HER BOOTS TODAY?”

Márta Várnagyi

WORSHIP FROM THE “COMMUNICATING GENDER” CONFERENCE

BUDAPEST TO BERLIN

WSCF Europe Office

GOING DEEPER IN UNITY

Gabriela Bradovkova

SEMINAR ON ECUMENICAL STUDENT

WORK IN EUROPE

Gaute Brækken

CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS

6 7 8 9 12 16 22 27 34 37 39 44 46 50 52 54 56 1 | Think 2 | Know 3 | Resources 4 | Federation

3 Mozaik 29

1 | Think 6 THE ESCHATOLOGICAL CLOSET Marta Gustavsson 7 SHE , ALPHA MALE Stephen Canning 8 FROM THE ARCHIVES Eva Danneholm 9 A BABY NAMED STORM AND THE CASE FOR A NORMATIVE PATTERN FOR GENDER Nick Schuurman 12 IS GOD A ‘SHE’ OR A ‘HE’? JoAnne Lam

Marta Gustavsson is active in the Swedish SCM, KRISS, and holds a Master of Arts in Theology from the University of Gothenburg. In her theological studies, politics and bodies have been the most important focuses. Now she is preparing for ministry as a pastor in Church of Sweden. Email: martagustavsson@ gmail.com.

Marta Gustavsson the eschatological closet

Marta Gustavsson the eschatological closet

enter the closet and escape the world where your gender your experience your longings your secrets are demanded as official acts

escape the standards according to which you have to testify about it all to be convicted free and judged true escape and come in, to celebrate your ambiguities, refuse to pronounce yourself with as little complexity as they’d have

as when you tried to come out of your shell and break free of your secrets first time; you traded a hardship for another exchanging the suffocating silence for the full story, no more options were there so is there no life with ugly pants on? no-one watching

is there a grace with which you may move through the gardens of your inner life and watch the flowers of pain you have planted and express your pride? a swift mercy

can there be a crossroads where your body is secretly facing the crucified the demanded shame? everything laid bare the penetration of his side, the way you know it happened maybe the promised land is without the kind of questions that will accuse you of all at the gates of the heavenly closet you may lay down all your burden, garments, bras and make-up-layers lay them down and cry

and enter, then and be redressed beyond the masks of truth and take your voice in the unity of praise and of what used to mark your position

a silence will be kept

6

Stephen Canning is simple yet profound, or so he is told. He likes hugs, smiles and playing guitar. He thinks too much and drinks in moderation. Email: normalstevetwodogs@ gmail.com.

Stephen Canning

She

She must have been good looking as she had many admirers

She cleaned men’s feet like a dutiful wife She looked after the children when the men were too busy

She fed hungry mouths when the men had failed to prepare She went out and found the men who had forgotten something important She talked a lot, to a lot of people She cared and healed like a good nurse

She was loved by many She stayed up talking to her mother while the men slept

She was abused, stripped naked and murdered by mans violence

Like many mothers the extent of her love was not appreciated until she had died

She never stopped loving her children

Mother Jesus

I never stopped loving you

Alpha male

I am an alpha male

No really I am

My friends often laugh

At such a notion

But it’s true

I am man enough

To stand up and fight

Against injustice

By peaceful protest

Or direct action

I am man enough

To carry heavy things

By being there to listen

I can carry a friend

In times of trouble

I am man enough

To control my feelings

When I cry

Or show public signs

Of affection

It’s because I meant to

7

Mozaik 29

Eva Danneholme

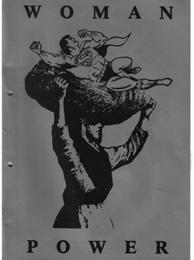

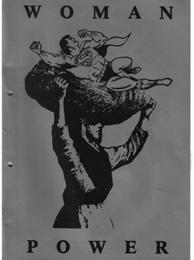

Taken from the 1981 publications “Woman Power”, a thematic handbook put together by the WSCF Europe women’s project. It explored women’s perceptions of power, not only the fear and distaste of it, but how women can be liberating in faith in a free and freeing God.

Eva Danneholm From the Archives

Eva Danneholm From the Archives

A group of men came, and they interrupted our talk. I think they had been to town to get him something to eat. After the men had come, there was no way to continue our conversation, so I went.

I just couldn’t stand there waiting. The talk we had begun had got so much moving inside me. He had told me everything I’ve done; “You’ve been married to five men, and the man you live with now is not really your husband”, said he. I heard his words, felt his judgement and waited for him to reject me. But he just looked at me. He looked at me – and I completely lost my thread. What suddenly struck me was the thing I’d been thinking over without having anyone to discuss it with.

I didn’t think about who I was or who he was. I just said to him, “My Samaritan ancestors worshipped on this mountain, but you Jews say that Jerusalem is the place where we should worship God”. And he answered me. I said something about the Messiah, and he said: “I am he, I who am talking with you”.

Yes, maybe he is the Messiah... Come and see!

I believe in Jesus, who discussed theology with a woman by a well and who confided first to her that he was the Messiah and who made her go back to town,

and tell the people there about her new experience.

8

Email: schuurman. nick@gmail.com.

Nick Schuurman

A Baby Named Storm and the Case for a Normative Pattern of Gender

EARLIER this year, a Toronto newspaper ran what would have otherwise been a minor story, were it not for the amount of attention and reactions it would eventually end up eliciting. No natural disaster, no inner city murder, no major law amended, no stock plummeted. The journalist had simply visited, and written a profile of an otherwise unassuming local family of five. The controversy and its resulting reactions were sparked by, of all things, a member of the family’s most innocuous ddemographic: a four-monthold infant named Storm.1

What made this story something of an international sensation was the decision made by Storm’s parents, Kathy Witterick and David Stocker, to keep the infant’s gender a secret. The only people who know whether Storm has a Y chromosome are or a pair of Xs are the parents, the siblings, a family friend and the two midwives who helped with the delivery. Storm’s siblings actually turned into a bit of a news story themselves. Brothers Jazz, five, and Kio, two, have, since they were each 18 months old, been choosing their own outfits and

Nick Schuurman lives in Cambridge, Ontario, Canada, where he works as a pastor.

9

Mozaik 29

1 Poisson, Jayme, “Parents keep child’s gender secret”, The Star, 21 May 2011, http://www.thestar.com/article/995112.

hairstyles. Jazz, who often is mistaken for a girl, appears photographed with fingernails painted and hair in three long braids.

While their story may have received more attention, they are not the first to have raised a child without gender. A few years back, a Swedish newspaper reported a couple doing the same thing, with their two-year-old, nicknamed Pop. The parents are quoted as having made the decision because they – like the Toronto couple –wanted to “avoid [him or her] being forced into a specific gender mould from the outset”.2

Here is the underlying irony that has already been pointed out. If it is true that social norms regarding gender are simply constructs that have evolved over time, and that “forcing a child”, as it were, to fit into those categories (of what it means to be male and female) is a form of cultural imperialism, or, as some have suggested, oppression outright, what do we do with this new set of constructs, and this new set of values that is being imposed?

Interviewed in the course of the article, Stocker explains, “What we noticed is that parents make so many choices for their children. It’s obnoxious...” What he is referring to, of course, is the likes of pink dresses for little girls, and toy trucks for their counterparts. But supporters and critics of their decision alike have been quick to point out that they also are making a decision on behalf of Storm, in allowing (and here, the lack of pronoun becomes noticeable: “him” and “her” are immediately out, and “it” is a rather undignified and dehumanizing replacement) their child to choose.

ought to accompany male and female genitalia that are social constructs and products of particular periods and places of cultural formation, is there a normative (true and authoritative regardless of cultural context) pattern for gender and sexuality that we can turn to in the context of discussions such as these? This question lies at the heart of no few debates regarding gender, sexual orientation, marriage, and the role of men and women in society and religious orders. Currently, in the West, the suggestion that there may be a universal intended order for such things has been intensely scrutinized. And yet, without it, we are left with a peculiar metaphysical anxiety, and no apparent end to the debate.

What I am going to suggest is that there is indeed a normative pattern for gender. The credibility of this of course requires a few presuppositions, the most basic being that, regardless of the specifics of how the universe came into being, there is a Creator, who pieced things together with an intended order for how things ought to be, and that the texts describing these accounts are authoritative and true. While it may be true that “boys are, by nature, hunters” is less of a normative pattern for maleness and more of a gender stereotype, as a people informed by this text, we should, as theologian Mary Van Leeuwan writes, “look to Scripture for a framework of control beliefs about sex and gender”.3

In the beginning of the ancient Hebrew Scriptures, we read a complex and beautiful poem, describing God’s initial creative work. Culminating six days of forming and filling, we are told that God creates humanity “in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them”.4 10 Nick Schuurman: A

While it is no doubt true that there are many elements of our modern understanding of the type of life that

Baby Named Storm and the Case for a Normative Pattern of Gender

2 “Baby raised without gender sets off debate”, CTV News, 26 May 2011, http:// www.ctv.ca/CTVNews/TopStories/20110526/genderless-baby- storm-110526/.

3 Van Leeuwen, Mary, “Gender & Grace: Love, Work & Parenting in a Changing World”Gender and Grace, (InterVarsity Press: Illinois, 1990), 39. 4 Genesis 1: 27 (ESV).

From the very first mention of humanity, then, before any complex form of society as we would define it existed, we have the categories of male and female. And this is not exclusively a sexual distinction (there is more going on here than God simply saying, “XX and XY, and all resulting hormonal and physical differences, I created them”); there is a normative pattern for what it means to be man and woman. This is seen more clearly in the verses preceding and following. Part of what it means to be male and female, the account explains prior to this, is the shared task of caring for creation (“let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens...”).5 They are also, man and woman, told to give birth, fill the earth, and have dominion over the earth.6 In the second creation account, written following the first chapter, we are further told that male and female were categories intended to compliment each other in intimacy and fellowship of community: “It is not good for man to be alone”.7

As Van Leeuwan in her book argues, the distinction that is made between gender and sexuality is often not as simple or clean-cut as it is made out to be. “A sense of gender identity”, and not only the biological categories of male and female, she argues, “[is an] important aspect of the image of God in all persons”.8 There is a mess of cultural assumptions and constructed values that need to be sorted through here, and a need for wisdom in discerning what is culturally informed, and what is normative and part of God’s good created order.

I also realize that this discussion, like many of the current debates regarding gender and sexuality, really ought to be understood on two levels. After all, if I am talking to someone who doesn’t believe in any sort of higher power, who thinks that the Hebrew and Christian scriptures are, like our modern concepts of gender, antiquated cultural constructs, I am going to have to take a few steps back and start at a completely different point than the first chapter of Genesis. If I wanted to

argue, for example, that adultery is wrong, on the basis of my faith and the text that informs it, with someone who believes that the Bible is a human text, full of flaws, describing interactions with a mythical deity, we might as well be talking in different languages.

And so for me to approach Witterick and Stocker and tell them, “my Bible says you are wrong to do this” would not at all be helpful, because they do not see it as in any way authoritative. And so, when it comes to public debates regarding homosexuality, polygamy, pornography, and adultery, the first step Christians need to do is to take a step back, while affirming the truth that informs our faith, and find a different starting point. █

5 Genesis 1: 26 (ESV).

6 Genesis 1: 28 (ESV).

7 Genesis 2: 18 (ESV).

8 Van Leeuwen, Mary, “Gender & Grace: Love, Work & Parenting in a Changing World”, (InterVarsity Press: Illinois, 1990), Van Leeuwen, 54.

11 Mozaik 29

is a Master of Divinity student at the Waterloo Lutheran Seminary in Canada. She has served as an intern at the WSCF Inter-Regional Office in Geneva in 2002-2003. She is a graduate from the Toronto School of Theology, Master of Theological Studies and the Ecumenical Institute of Bossey, Master of Advanced Ecumenical Studies programs. Her latest project was a thesis on the Lutheran-Orthodox dialogue on Eucharist. Her intercultural identity includes being born in Hong Kong, immigrated to Canada, and now residing in Switzerland. Email: ijklam@gmail.com.

We are happy to welcome JoAnne Lam, who will offer Mozaik a column related to the ongoing themes we are exploring. JoAnne has been engaged in the WSCF previously and now she is researching issues concerning the Eucharist. She is also blogging, raising two kids and engaging in ecumenism.

JoAnne Lam

JoAnne Lam

Is God a ‘He’ or a ‘She’?

“CERTAINLY, God is a man! We call HIM the Father Almighty! I don’t know why is the minister saying ‘Mother and Father’ when she was referring to God?” Has there been a moment in your life that you either shared a similar thought or simply questioned the validity of challenging the ‘maleness’ of God in the Christian churches? It is a constant struggle to decipher how gender impacts our perceptions of God. The human tendency is to superimpose our frames of reference onto the One who ultimately created us. Is that not ironic? That is theology – humanity’s attempt to understand God.

To address the nature of God in the context of gender, a differentiation between ‘gender’ and ‘sex’ is necessary. Gender and sex are two different concepts that become mixed into one or used interchangeably. Sex identifies the biological assignment as male and female, while gender deals with social and cultural roles associated with the respective sex. Traditionally, masculinity embodies strength, protection, and trustworthiness. On the other

JoAnne Chung Yan Lam

JoAnne Chung Yan Lam

12

hand, femininity portrays fragility, gentleness, beauty. The issue becomes prominent when these traits become assigned to the male and female sex respectively. To exclusively assign masculinity as a male characteristic and femininity as a female one limits the capacity to embody the fullness of each sex. Furthermore, these gender perceptions limit men as the providers and the authority figures within the patriarchal society, while the women become dependents and only significant in the matters of fertility and rearing children. Having a masculine God points to the human desire for a presence of protection and strength. Especially within a patriarchal society, power and authority rests with the men and how could God be a frail and powerless being when God possesses great authority over life and death? Although this explains one reason to label God to be male, it cannot justify the rejection that God is also female. To identify God with one gender significantly restricts God’s dynamic presence as all things to all peoples. Contrastingly, in matriarchal societies, this same argument can be applied and it would be interesting to survey if the language of God remains similar to patriarchal systems.

presence should not be ignored. The creation story cannot be understood without the appreciation of the birthing process. The world’s lack of respect for the environment can be attributed to the entitlement to govern and dominate creation. However, to understand God as a mother to have given birth to creation, greater care and empathy may be inspired before corporations depose toxic wastes and governments reject such agreements as the Kyoto Protocol.

Now, to apply these identifiers of gender to the nature of God creates difficulties because the assumption has been that God would only embody one gender or the fact that God requires a gender. In the Trinitarian formula of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” as well as the constant reference of God the Father throughout the Gospels reinforce the male gender of God as well as the nature of the relationship between God to creation. Though I celebrate the naming of God as the fatherly presence in the world, the feminine and motherly

God is the source of humanity and in God is both female and male. Out of a formless void, God created and in ‘our’ image, God created the first human, Adam. From Adam materialized Eve and if we use simple mathematics to understand this, only with Adam and Eve together would the two become the full image of God. This understanding does not solve the issue of “so do we refer to God as ‘he’ or ‘she’?” To be honest, I do not believe there is an answer. Perhaps the issue is not to decide whether God is to be called a ‘he’ or a ‘she’, but rather to understand the implications of assigning a gender to God. Our languages have limitations when they are used to describe God. Even though in some languages, such as the Chinese language, the word God does not hold a gender, the usages of ‘Father’ as the divine personified continue to repress the necessary presence of ‘Mother’ language, especially in liturgy. God does not and cannot fit into a box that is shaped by human understandings. Instead, the mysteries of the Creator continue to engage us in discovering our relationship with the divine, the One whose image created the one humanity. Is it more important to understand the communion that God seeks to have with creation or to decipher if God is a ‘he’ or ‘she’? God is neither he nor she. God is love. God is grace. God is hospitality. God is all things to all people but one thing remains: God is GOD. █

13

Mozaik 29

“God is the source of humanity and in God is both female and male”.

2 | Know 16 MY FAITH, MY GENDER Kathy Galloway 22 HOMOEROTICISM AND THE BIBLE: TIME FOR A FRESH APPROACH Kjeld Renato Lings 27 WOMEN AND THE 16TH CENTURY Jens Christian Kirk

Kathy Galloway is an ordained Church of Scotland minister and was, in 2002 the first woman to be elected leader of the Iona Community. Kathy is currently based in Glasgow where she leads the team and represents Christian Aid at a national level.

The following is an excerpt from the lecture and workshop lead by Kathy Galloway at the “Communicating Gender: Gender Identities in a Globalised Europe” WSCF Europe conference in October 2012 held in Løgumkloster, Denmark

Kathy Galloway

MY GENDER, MY FAITH

The gendered experience

IDON’T think that gender per se shapes faith or our experience of God. We are all a complex constellation of voluntary and involuntary identities, and are also strongly shaped by geography, landscape, history, culture, class, ethnicity, education and personal temperament. I don’t think my experience of God is the same as all women; I think my faith has more in common with many men in Scotland than with many women in Indonesia or Brazil. I was reflecting on all this once, and I wrote poem – it is about my family – two brothers, two sisters, two parents. It’s called Gender: stubborn kind vivid determined gentle passionate disciplined analytical assertive

perceptive

attentive logical aesthetic active intuitive daring

16

domestic reflective astute muscular creative decisive athletic conflictual

wise responsive encouraging humorous enthusiastic receptive contained spontaneous organised

gregarious sensitive serious miutic nurturing co-operative caring resourceful vulgar

here are six people three of them are men three of them are women but which are the men and which are the women?

I’m not even sure how fixed a thing gender is, and how much is culturally conditioned or performative. Here’s another little poem:

I have hairs growing on my chin My shoulders are rather broad Though I am not thin, I have never been on a diet I am uninterested in shoes, except to keep my feet dry. Wounded, I am a Martian I must be a man!

But I am pretty sure that the experience of patriarchal systems and language shapes our experience of God, of power, of identity, differently by gender, and not in a good way for either women, or ultimately for men.

A member of the Iona Community served as an Ecumenical Accompanier1 in the West Bank village of Jayyous a couple of years ago. While there, she wrote me an email, describing a visit she had made to a family on the wrong side of the Wall or separation barrier (which there takes the form of a triple fence), which has cut several miles into the West Bank, and separated the townspeople, mostly farmers, from 75% of their land. Some of them can still pass through a check-point to work on the land, as long as they have permits. When the Wall was built, it cut off the farmlands and one home – the smallholding of a Bedouin family who had settled

a little way out of town. So now their children have to go through the checkpoint during the brief openings in the morning and at midday, to get to and from school. Visiting the family, Jan was taken to visit two of its members:

He led me along to the kitchen door. I looked into its smoky darkness, and saw two young women. These were his older sisters. In the town we had heard about them – how they had been badly treated by the soldiers, when they had to pass through the checkpoint: made to remove their headscarves, searched. And so their father had withdrawn them from school. They are normal lively teenagers, living in an isolation incredible to us. As I stood in the kitchen doorway, I could turn and see the nearest houses of Jayyous, on the other side of the barrier –a few minutes’ walk away. But these girls were not allowed to go there, cut off by politics on one side and culture on the other. They smiled and welcomed me in low voices,

17

Mozaik 29

1 The Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel of the World Council of Churches . The role of participants in the programme includes: Monitoring and reporting violations of human rights and international humanitarian law; supporting acts of non-violent resistance alongside local Christian and Muslim Palestinians and Israeli peace activists; offering protection through non violent presence; engaging in public advocacy policy; standing in solidarity with the churches and all those struggling against the occupation.

and practised a few words of English. Then one asked me in sign-language – Do you have a mobile phone? May we borrow it? Quickly?

So they did, and while their little brother kept watch, and I looked across the wall at the town, the jeeps passing on the intervening road, they rang and spoke (like any teenagers) to the school-friends from who they are now separated, certainly until they reach school-leaving age, probably for

longer. Their only chance of escape from this situation, this isolation, the leaky roof, the smoky kitchen, is for their parents to arrange a marriage. But their education has hit the wall.

Jan also sent me an email with a photograph attachment. But when I opened the picture file, I discovered that a Trojan had gained access to it, and the West Bank photos were accompanied by dozens of pornographic images. Though I didn’t trawl through the whole file, I saw enough to realise that these could in no way be described as ‘glamour’ shots. They were of ordinary young women, most of them very young, in what looked like suburban bedrooms, mostly shot in extremely graphic poses. Some of the faces were expressionless, some wary, some looked terrified. This curious juxtaposition of women’s stories – the peace activist, the Muslim school girls in a war zone, the sexually commodified teenagers – struck me forcibly as a paradigm of the gendered experience.

They exemplify some stark realities – that women are the primary victims of violence. But there are other forms of violence of which women are disproportionately victims:

⦁ 70% of the world’s 1,3 billion poor are women;2

⦁ 66% of the world’s illiterate people are women;2

⦁ 80% of the world’s refugees are women and children;3

Racism and xenephobia render all of these conditions more acute. And all of this does not include the women who suffer direct violence, injury and death in war. Statistics are dry: two Muslim schoolgirls caught on the wrong side of the line in a military occupation are the human faces of the victims of violence, the sexually commodified teenagers are also the human faces of the victims of violence.

2

18

Kathy Galloway: My Gender, My Faith

United Nations Department of Public Information, Women at a Glance, DPI/1862/Rev.2, (New York: 1997), http://www.un.org/ecosocdev/geninfo/ women/women96.htm.

3 Julie Mertus, Mallika Dutt and Nancy Flowers. “Human Rights of Refugee, Displaced and Migrant Women”, Local Action/Global Change: Learning about the Human Rights of Women and Girls, (Centre for Women’s Global Leadership and UNIFEM, New York: 1997).

I think it’s important to stress what might seem obvious, because a second reality exemplified by my story of women is that what sometimes seem to be strategies in the interest of women turn out to be actually in someone else’s interest. One of the broad goals of the 20th century women’s movement in the West was that women should enjoy not just the political and civil rights that men had, but that they should also be able to avail themselves of the same freedoms enjoyed by men, such as agency, self-determination, sexual autonomy and bodily integrity – the right to control their own bodies, to be not possessed. And indeed, for many millions, this has been a goal attained, has

allowed women to leave abusive relationships, to own and enjoy their sexual desire, to dissent from practices that harmed them, to desist from the relentless childbearing that killed so many women in the past. But for many, perhaps the majority of women in the world, that freedom has actually been turned against them, because in practice it is only available to women who have economic freedom also. A cultural climate of increased sexual license has hugely increased the extent to which it is acceptable to commodify sexuality – in such a climate, all that is needed to exploit this market is a ready supply of buyers and sellers…

I am often asked why feminist activists, including Christian ones, seem to organise in all-female groupings. Is it because we are anti-men, or because we don’t realise that men suffer too?

It’s perhaps a necessary protecting of a free space; women are by and large socialised to please, to defer to, and to serve men. Here, I must confess to a degree of ambivalence, not about service itself, but about the Church’s use of the language of servanthood. In the gospels, servanthood was commended by Jesus to his male followers, and as such was a subversive, even offensive notion. Ever since, servanthood has been commended by men in the Church to women, and as such has been a reinforcement of the status quo, and all too often a strategy for keeping women firmly in their place. This has often gone hand in hand with men in positions of great power and influence proclaiming that they are humble servants, while behind the scenes, women have cleaned up, picked up and kept their mouths shut. So you see, as a feminist theologian, I have a strong hermeneutic of suspicion about the term.

19

29

“...what sometimes seem to be strategies in the interest of women turn out to be actually in someone else’s interest”. Mozaik

The truth is women would love for more men to be more involved. But the one thing that would make the most difference – that is, for men to confront and challenge male violence and the structures of masculinities –the majority seem curiously reluctant to do. Women consistently find that their most reliable partners and allies are other women.

It is sometimes suggested that feminist theology is a preoccupation of privileged white western women, and is of no interest or relevance to women in the global South. But there are feminist and women-centred theologies in every part of the globe, engaging with just these issues, and talking to each other; and as the Hispanic mujerista theologian Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz comments ruefully:

If we are women theologians in the 1st World, we are told we are out of touch with the women in the pews. If we are 3rd World theologians, we are told ‘these women’ from the 1st World are unduly influencing us – as if we were not capable of thinking for ourselves.

By defining women through and for men, secondary, derivative and sometimes completely invisible, hugely important aspects of God, faith and the Church also become secondary, derivative and sometimes completely invisible.

We need to find language and images for bearing witness in worship and theology which allow us to relate in a fuller way to God, so that we may name our experience of the immanence of God, God-with-us, God embodied, as well as of the transcendence of God, of the vulnerability and weakness of God as well as the power of God, of the wounded and suffering God as well as of the God of Armies. And of a language of the family that suggests intimacy, mutuality and a wider vision of being family rather than the property, posterity, purity and power model that is the bottom line of patriarchy.

This will require us to be creative, observant, open, and most of all, it will require us to get the censors off our religious imagination. Vulnerability and weakness, intimacy and mutuality, God-with-us, are seen in places and among people who are ignored and overlooked by the Church, except as objects of piety and patronage – the very poorest people, children, the frail and old, street-sleepers, beaten and wounded armies, those who are excluded, messy families, and so on. But we don’t look among them for our models of God - which is curious, really, because Jesus, almost alone among historical liturgists, did exactly that!

Language reflects the dominant patterns of a culture. But it also reinforces them. That’s why totalitarian states silence the artists and poets and journalists first, to avoid the patterns of power being subverted. If we leave the naming of our relationship with God so onesided, so distorted, then we are complicit with a context in which abuse, concealment and disregard for the vulnerable flourish. The Japanese-American theologian Kosuke Koyama has written:

Grace cannot function in a world of invisibility. Yet in our world, the rulers try to make invisible the alien, the orphan, the hungry and thirsty, the sick and imprisoned. This is violence. Their bodies must remain visible. There is a connection between invisibility and violence. People, because of the image of God they embody, must remain seen. Faith, hope and love are not vital except in what is seen. Religion seems to raise up the invisible and despise what is visible. But it is the ‘see, hear, touch’ gospel that can nurture the hope which is free from deception.

The one God embraces the one world which speaks more than 7000 dialects and languages. God is open to all cultures and nations. How many languages does God speak? All of them! No people can speak in an isolated language and have an exclusive self-identity. … The church is in the world and the world is in the church. God’s word

20 Kathy Galloway: My Gender, My Faith

to the church is God’s word to the world. There are not two words of God, one for the church and another for the world...4

I will probably continue to be a faithful worshipper. I will do this because I love the little struggling local community of faith I belong to and because I have a minister who takes these questions, and others, seriously and respectfully. I will do it because I still find in so much of the Bible, liturgy, hymns, ‘the room for hope to enter, the space where we are freed’. I will do it in solidarity with those in churches everywhere who make great sacrifices to remain in community in worship. I will do it because I have a passionate Reformed conviction of the priesthood of all believers, and long for the day when ‘all’ actually means all. I will do it along with the women who believe, with Musimbi Kanyoro, a Kenyan woman theologian writes,

during his life here on earth, Jesus visited the towns and villages and saw with his own eyes the problems facing the people. He saw poverty, the inequality, the religious and economic oppression, the unemployment, the depression, the physically ill and the socially unclean. His heart was filled with pity. He pronounced what his mission was all about: he came to preach the good news to the poor and to release those who are captives and give health to those who are ill.5

I will do it for the moments in worship when I glimpse the life that is held and encompassed in the divine mystery and love from which nothing can separate us. I will do it because ultimately this struggle is who I am and all I have to offer.

But I will do it always with brokenness, because I know that at the deepest level of my being, I do not trust the institutional church to care enough about the wellbeing of women to give up the power of patriarchy, even

though Jesus did. I do not believe that God is male, however God is named. This is not a statement inconsistent with orthodox Christian theology. But it is certainly inconsistent with conventional Christian practice. █

4 Kosuke Koyama, from an address given at the 8th WCC Assembly, Harare, Zimbabwe, 1998.

5 Musimbi Kanyoro, from an address given at the closing conference, WCC Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women, Harare, Zimbabwe, 1998.

21

29

Mozaik

Kjeld Renato Lings

Homoeroticism and the Bible: Time for a Fresh Approach

Kjeld Renato Lings

is a Danish Christian Quaker. He holds an MA in Spanish, a diploma in Translation Studies and a PhD in Theology. In 2011, he published Biblia y homosexualidad Renato’s latest book project is entitled The Bible & Homosexuality: What Mistakes Do Translators Make? Email: biblioglot@ googlemail.com.

MANY

Christians think that the Bible forms the basis of our moral universe. However, the historical evidence points in a different direction. As stated by Joseph Monti,1 classical Christian sexual morality is a product of the patristic age, not the Bible. Two thousand years of theological reflection have placed an ideological filter between the Bible and its modern readers. What today’s Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Protestant theologians say on sexuality is largely based on the medieval writings of celibate male clergy some of whom were misogynous and of advanced age. In addition, most Church Fathers took inspiration from anti-erotic strands of Greek philosophy.2 The hierarchical gender views of antiquity placed masculinity at the top of the scale and femininity at the bottom.3 All such extra-biblical elements have influenced Christian thinking on sexuality.

To take a fresh look at the issue of homoeroticism in the Bible, we need to discuss the terms involved. Are the

In recent decades, most Christian communities have experienced heated debates on homoerotic relationships. Very often the Bible is quoted. This article seeks to clarify the concepts involved and recommends a fresh, gospel-based approach to the issue.

22

well-known words ‘homosexuality’ and ‘Bible’ compatible? They came about at very different times in history.

‘Bible’ has ancient Greek origins while ‘homosexual’ was coined in 1869. Furthermore, no word in the Bible translates as the modern term ‘homosexuality’. Hence it is an achronistic to speak of homosexuality in biblical contexts. A flexible terminology with little or no cultural bias is preferable. Personally I tend to use the more neutral term ‘homoerotic’.4

Despite this terminological confusion, a fierce controversy over the Bible and homoeroticsm has rocked the entire Christian world for several decades. Interestingly, most scholars agree on exegesis, for example in the case of Leviticus 18: 22 (‘With a male you shall not lie down...’). However, discrepancies arise in the conclusions drawn from the texts. Simply put, three theological schools exist. Some argue that the Bible condemns any expression of a homoerotic nature.5 Others suggest that the scriptural prohibitions echo specific social and cultural contexts of the ancient world, which are irrelevant for people today.6 A third trend argues that the very idea of biblical condemnation of homoeroticism belongs to the post-biblical age.7

Scripture and Sexuality

Most Old Testament texts were written in Hebrew prior to the Christian era. The Greek Old Testament translation known as Septuagint (LXX) appeared in Alexandria around the year 200 BCE. The influence of the Septuagint on Christian attitudes to sexuality was immense. In the early Church the LXX completely replaced the original Hebrew Bible.8 All New Testament writers quoted the Septuagint.9 Today’s Orthodox churches still venerate the Septuagint as their official version of the Old Testament.10 With the Roman conquest, Latin joined the languages of ancient Palestine, which already included Classical Hebrew, Late Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. The

Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible appeared towards the year 400 CE and eventually became the official Catholic Bible.

The Church Fathers, particularly Augustine of Hippo who wrote in Latin (354–430 CE), elaborated on Paul’s ideas on original sin in Romans 5: 12.11 This concept holds a central place in Christian theology in relation to sex. By contrast, Jewish theology completely lacks the notion of human sinfulness. According to rabbinic tradition, Genesis 3 describes the natural development of human consciousness between puberty and adulthood.12 The difference between Christianity and Judaism in this regard is largely based on interpretations of the Greek Septuagint and the Hebrew Bible, respectively.

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century launched the motto sola scriptura (‘scripture only’). The Reformers proposed to return to the biblical sources in the original languages in order to distance themselves from Catholic tradition.13 However, except for celibacy, in most Protestant circles the restrictive medieval approaches to sex have remained stable into the twenty-first century, especially in regard to homoerotic relationships.

Christianity and Homoeroticism

A recent survey in the United States showed the personal views on Christians held by young non-believers.14 The majority said that modern Christians were anti-gay, intolerant, and hypocritical. This is understandable given that many churches regard the rejection of homoerotic relationships as fundamental doctrine.15 According to this view, a homosexual person cannot be a Christian

23

Mozaik 29

“A fierce controversy over the Bible and homoeroticsm has rocked the entire Christian world for several decades”

(= no Christian can be gay). In practice, the churches have introduced an imaginary Eleventh Commandment saying, ‘You shall not have homoerotic relationships’.

The anti-gay position in current Christian thought is supported by a large number of Bible versions, commentaries and dictionaries. All make it very clear that the Old and New Testaments prohibit homoeroticism. Generally speaking, today’s gay and lesbian believers are given the following choices:

1. pray continually;

2. deny their erotic impulses by marrying an oppositesex partner;

3. relinquish sexual intimacy by becoming celibate; or

4. undergo lengthy ‘Christian’ psychotherapies for the purpose of changing their sexual orientation.16

The problem with these options is that none has proved convincing. Many lesbian and gay Christians have tried, but no matter how sincere or fervent their daily prayers for change may be, their erotic impulses do not change. Those who marry an opposite-sex partner do not find happiness. Instead, they and their spouses suffer. The divorce rate in this group is high. Moreover, forced celibacy is a heavy burden. Some sign up for psychotherapy, but years go by without any noticeable change occurring. A state of depression is often the result. Tragically some of these lives end in suicide.i In recent decades, psychologists and psychiatrists have realized that homoerotic inclinations are not a mental disorder requiring treatment. Today sexologists classify homosexuality as a natural variant of the human sexual spectrum along with heterosexuality and bisexuality.ii

‘By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them’

Another interpretation of this situation is suggested by the gospel of Jesus Christ. In Matthew 22: 37–40 Jesus draws attention to the supreme commandments of the Old Testament: Love God with all your soul

(Deuteronomy 6: 5) and your neighbour as yourself (Leviticus 19: 18). This road leads to life (Luke 10: 28). In other words, the Christian way of life is to practise love (John 13: 35). At other times Jesus invites his listeners to examine what religious teachers preach: ‘By their fruits ye shall know them’ (Matthew 7: 16). If this hermeneutical principle is applied, it becomes clear that the fruits produced by Church persecution of lesbian, gay and bisexual people have been bitter and stale. Traditional biblical interpretation has not delivered. It has ruined the lives of thousands of women and men by coercing them into a constant state of fear, introspection and brainwashing.iii

Moreover, the churches ignore a very important fact: lesbian, gay and bisexual people do not identify with the alleged anti-gay texts in the Bible. LGBT people feel unduly attacked and unfairly accused. Thomas Bohache17 compares the current Christian approach to homoeroticism with the issues discussed by Paul in his letter to the Galatians. The apostle rejects the idea that Gentiles should convert to Judaism before joining the Christian community. According to Paul, what matters is faith in Christ. No circumcision is required because it would contradict the inclusiveness of the gospel message (cf. John 3:16). Similarly, Bohache argues that those who want to place special burdens on LGBT people are opposing the fundamental doctrines of Christianity.18 Christians should not submit to pressures from their social environment.19 Paul says, ‘Am I now seeking... God’s approval? Or am I trying to please people? If I were still pleasing people, I would not be a servant of Christ’ (Galatians 1: 10).

Unfortunately a very large part of Church discourse on human sexuality ignores the solid academic research

i In Canada the rate of attempted suicide for all youth is seven percent. For lesbian and gay teenagers the rate is approximately 32 percent.

ii www.truthtree.com (2010).

iii www.truthwinsout.org/uncategorized/2007/09/264.

24 Kjeld Renato Lings: Homoeroticism and the Bible: Time for a Fresh Approach

published in recent decades.20 An empirical factor of great importance should be noted: homo- and bisexual relationships exist all over the animal kingdom. Among hundreds of species of mammals, birds, and insects, zoologists are documenting widespread bisexual activity as well as the existence of long-term couples formed by two females or two males.21 The statistical frequency of homo- and bisexuality among animals corresponds roughly to the proportions found among human beings.22

Relevant Bible Texts

In order to find a way out of the current theological deadlock, it will help to take a fresh look at the relevant texts in the Bible. The key texts are found in both Testaments: the opening chapters of Genesis, the story of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 18–19), Leviticus 18: 22 (+ 20: 13), Deuteronomy 23: 17–19, the drama of Judges

19–20, and some Pauline letters in the New Testament (Romans 1: 26–27; 1 Corinthians 6: 9; 1 Timothy 1: 10). The role of Bible translation is crucial whenever the issue of homoeroticism in the Bible is discussed. Unfortunately many serious mistakes are being committed. For example, in Genesis 2: 21–22 the word ‘side’ has become a ‘rib’; in Genesis 4: 1 and 19: 5 ‘know’ has been replaced by ‘have sex’, and in 1 Corinthians 6: 9 translators inexplicably suggest that Paul speaks of ‘homosexuals’—despite the fact that the unusual Greek words used by Paul ( arsenokoitai and malakoi ) do not appear in Greek homoerotic literature. Clearly a large number of English Bible translations are biased whenever they are dealing with perceived homoeroticism.23

At the same time, the Bible includes a number of optimistic texts of great importance to discussions on homoeroticism. While these biblical passages have been ignored by Christian tradition, their literary, historical, cultural and social aspects are well worth scrutinizing. Such texts include: The book of Ruth (two women called Ruth and Naomi); Samuel 1 and 2 (two men called David and Jonathan); Psalm 118: 22 (the cornerstone); Isaiah 56 (a prophetic invitation to outsiders); Micah 6: 8 (what God requires); Matthew 8: 5–13 (two men blessed by Jesus); Matthew 19: 12 (eunuchs); Luke 8: 19–21 (the family of Jesus); Luke 17: 34 (two males in one bed); John 3: 16 (all believers); John 11 (the Beloved Disciple); Acts 8: 26–39 (the African eunuch); Acts 10 (what God has purified); Galatians 1 & 5 (Christians should not be circumcised); 1 Corinthians 13 (the greatest thing is love).

25

Mozaik 29

"Today sexologists classify homosexuality as a natural variant of the human sexual spectrum along with heterosexuality and bisexuality".ii

Conclusion

Ever since the days of antiquity a number of cultural, literary, historical and theological factors have influenced the way in which Christians read scripture. When it comes to human sexuality, a considerable proportion of today’s biblical interpretation is indebted to the theological currents of the patristic era and the Middle Ages. This situation is particularly poignant for lesbian, gay and bisexual people who in many countries are subjected to fierce discrimination in Christian churches.

Several key factors should be considered:

1. The Christian majority has relegated believers who identify as lesbian, gay, and bisexual to a theological void;

2. Some exegetical problems in the original texts have never been sufficiently solved;

3. Translations of such passages are often incomplete or misleading;

4. The literary, theological and human richness contained in the Bible has not been duly appreciated;

5. A fresh approach to the Bible is needed for heterosexual, bisexual, lesbian and gay readers to engage with the biblical texts in an attitude of curiosity, dialogue and respect. █

Endnotes:

1 Joseph Monti, Arguing about Sex: The Rhetoric of Christian Sexual Morality, (State University of New York Press, Albany: 1995), 27.

2 Kathy Gaca, The Making of Fornication: Eros, Ethics, and Political Reform in Greek Philosophy and Early Christianity, (University of California Press, Berkeley – Los Angeles – London, 2003), 1-2.

3 Anthony Heacock, Jonathan Loved David: Manly Love in the Bible and the Hermeneutics of Sex, (Sheffield Phoenix Press, Sheffield: 2011), 4.

4 cf. Bernadette J. Brooten, “Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism, (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

& London: 1996), 8.

Martti Nissinen, Homosexuality in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective, (Fortress Press, Minneapolis: 1998), 17 (Translated by Kirsi Stjerna).

Anthony Heacock, Jonathan Loved David: Manly Love in the Bible and the Hermeneutics of Sex, (Sheffield Phoenix Press, Sheffield: 2011), 3.

5 Robert Gagnon, The Bible and Homosexual Practice: Texts and Hermeneutics, (Abingdon Press, Nashville: 2001), 28–29.

6 Elizabeth Stuart, Gay and Lesbian Theologies: Repetitions with Critical Difference, (Ashgate Publishing Limited, Aldershot: 2003), 105.

7 Renato Lings, Biblia y homosexualidad: ¿Se equivocaron los traductores?, (Universidad Bíblica Latinoamericana, San José: 2011), 19–42, 342–347.

8 Bruce Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions, (Baker Academics, Grand Rapids: 2001), 18.

9 William Loader, The Septuagint, Sexuality, and the New Testament: Case Studies of the Impact of the LXX in Philo and the New Testament , (William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids: 2004), 127. (William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids: 2004), 127.

10 Bruce Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions, (Baker Academics, Grand Rapids: 2001), 20.

11 Elizabeth Stuart and Adrian Thatcher, People of Passion: What the churches teach about sex, (Mowbray, London: 1997), 18-19.

Alister McGrath, Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought, (Blackwell Publishing, Oxford: 1998), 82.

12 Lyn Bechtel, “Rethinking the Interpretation of Genesis 2.4b-3.24”, Brenner (ed.), 1993, 78–80.

Jonahon Magone, A Rabbi Reads the Bible, 2nd Edition (SCM, London: 2004), 124–125.

13 Bruce Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions, (Baker Academics, Grand Rapids: 2001), 9.

14 David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons, UnChristian: What a New Generation Really Thinks about Christianity, (Baker Books, Grand Rapids: 2007).

15 Bernadette J. Brooten, “Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism, (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London: 1996), 194.

16 Tony Green, Brenda Harrison, and Jeremy Innes, Not for Turning: An enquiry into the ex-gay movement, (Published by authors, UK: 1996) 89–90. Besen, Wayne, Anything But Straight: Unmasking the Scandals and Lies Behinf the Ex-Gay Myth, (Harrington Press, New York: 2003).

17 Thomas Bohache, “To Cut or Not to Cut: Is contemporary heterosexuality a prerequisite for Christianity?” in Goss and West Editors, 2000, 229.

18 Cf. William Countryman (2006: 752): ‘We should be intent on making sure that we work with the help of the trust we have already experienced as a gift from God and refuse to accept the idea that there are additional requirements if we want to stand in God’s presence. There are no additional requirements. We already stand there’.

19 Thomas Bohache, “To Cut or Not to Cut: Is contemporary heterosexuality a prerequisite for Christianity?” in Goss and West Editors, 2000, 232.

20 Mark Jordan, The Silence of Sodom: Homosexuality in Modern Catholicism, (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago: 2000), 56, 76.

21 Bruce Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, (Profile Books, London: 1999), 12.

22 Bruce Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, (Profile Books, London: 1999), 45.

cf. Greenberg, Steven, Wrestling with God and Men: Homosexuality in the Jewish Tradition. (The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison: 2004), 159.

23 Mark Jordan, The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology, (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago: 1997), 37.

26 Kjeld Renato Lings: Homoeroticism and the Bible: Time for a Fresh Approach

Jens Christian Kirk

Women and the 16th Century

An introduction to the possibilities for women to express themselves in the age of Reformation in Western Europe.

ITis disputed whether or not Christianity contains an emancipatory core regarding women. Throughout the history of the Church the distribution of the sacraments and the privilege of preaching the word have been restricted to men. However, in times of religious or political unrest or turmoil women have played a vital part in the fight for religious freedom and the Christian faith. No century contained as much religious disorder in Western Europe as the 16th century. Following Martin Luther’s ideas for reforming the church, the Evangelical Lutheran Churches, the Reformed Churches and the Anglican Church broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and created a whole new religious map of Western Europe. The intention of this article is to introduce you to the role and position of the women in this time of religious change.

It is, however, not an opinion piece on whether or not women should be able to become pastors or priests. Though in my opinion they should, as they are in the Evangelical Lutheran Churches in Scandinavia. It is not a critique of the present state of the Roman Catholic Church either, though it should be noted that I am a Lutheran theologian for a reason.

27 Mozaik 29

Jens Christian Kirk (1983), is a Masters of Theology, member of the Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church. General Secretary in Ecumenical YouthThe Danish SCM, married to Mette Helene and Father to Selma Sofie.

The Lutheran Reformation

Before getting to the main topic, I think a few notes on the Reformation as such would be helpful. The starting point for the Reformation was Martin Luther’s protest against the industry of discharge letters in 1517. In the following years, Luther and other Reformers such as Philip Melanchthon and the Swiss Huldrych Zwingli intensified their critique of the Pope and Praxis within the medieval Catholic Church. Schisms in the western Church seemed inevitable. The final schism, supported by a number of primarily German noblemen, followed the negotiations in Augsburg in 1530. The Lutheran confession – Confessio Augustana – was made in an attempt to clarify the belief as the genuine faith to the German Emperor. Upon his refusal, the Lutheran Churches were born.

To cover the basic principles in the Lutheran churches, it is highly focused on principles of sola gratia, sola fide and sola scriptura. Justification by God’s grace and by faith alone and the Bible as the primary source of the divine will. Following the latter, the number of sacraments was reduced to two – Baptism and Communion – and Bibles were made accessible to all through translation into German. The monasteries were closed and celibacy for priests was abolished as well, as Luther regarded the matrimony as ordained at the genesis.

Katherina von Bora Luther

Luther’s wife, a former nun, is in many ways the core example for women following the Lutheran Reformation. She ruled her home, controlled the family’s economy, raised and educated the children in the Christian faith.

The latter was a quite important task and a task that required literacy. Because of this, Luther and his fellow Reformers intended that everyone, even girls, should receive some sort of education that included the ability to read and write. Even today it is evident how much

emancipatory power is provided through literacy. The Lutheran Reformation, in many ways, required that the major part of the population were literate; also the women. And if for nothing else the Lutheran Reformation should be acknowledged for this.

Katharina von Bora Luther was the backbone in the Lutheran family, but suffered a life in poverty after Luther’s dead. That did not, however, reduce her role as an example for women in the areas that became Lutheran. A woman’s calling was to be married, to be a good wife and to raise her children as Christians.

28 Jens Christian Kirk: Woman and the 16th Century

The noble women

An interesting question regarding the Reformation is whether or not the kings and nobility that became Lutheran did so due to political or religious reasons. Both explanations might be given to some extent; however a distinct group within the nobility cannot be accused to let politics govern their religious beliefs – the noble women.

In Germany, Denmark and in France influential women such as Elisabeth von Brandenburg, Elisabeth von Braunschweig, Marguerite de Navarre, Jeanne d’Albret and Reneé de France influenced their ruling husbands, sons and brothers in order to accept or acknowledge the Reformers and people believing their reform.

The two former accepted Luther’s teaching by receiving both bread and wine in the communion, even though their husbands were Catholic. Later, they both somewhat ensured the possibility to exercise Lutheran Christianity in the areas governed by their husbands and later sons.

Marguerite de Navarre and her daughter Jeanne d’Albret were both highly influenced by the Lutheran teachings and later on the teachings of John Calvin. Marguerite was a sister of the French king, and as such closely connected to the court, and she did use that influence to hold back persecution of the Huguenots. Her daughter was married to another friend of the Huguenots, and as such she became a Huguenot leader during the civil wars, even though her son chose to become Catholic in order to become the King of France.

Reneé de France lived after her marriage in Italy. This was a much more hostile environment for the Lutheran teachings due to the close distance to Rome, and the close relations between the Italian nobility, the Pope and the most influential cardinals in the Vatican. In her position, she sought to provide some sort of safe harbour for Huguenots, which eventually became impossible.

Of course the noble women and their actions were made possible due to their status in society. Their lives were seldom if ever threatened; they were all literate and already had the possibility to express themselves on religion. That does not mean that their efforts were not of great value for the Reformers.

The writing women

But also “ordinary” women took action in defending the Reformation for example, in writing. Argula von Grumbach wrote a series of letters in the early 1520s in Ingolstadt, defending a young student accused of heretics, subscribing to the teachings of Luther and the other Reformers from Wittenberg. The writings were widely published and she earned Luther’s respect for her defence of the faith. It is possible that her writings were motivated by the fact that no men came to the defence of the student and that in this particular situation a woman had to step up. Nevertheless she spoke up, she defended the faith and the Reformers accepted and valued her contribution, while her opponents regarded her as a troublemaker.

Katharina Schütz Zell called herself a church mother, largely derived from her role as a pastor’s wife. The marriage to the pastor Matthias Zell was in itself controversial and even more so was the fact that she defended the marriage in published writings. She had received a lot of theological schooling in her childhood, and she continued to educate herself after the marriage both by reading, corresponding and talking to the Reformers. After Matthias Zells death and as the Reformed Church became more established in Strasbourg, where she lived, she became an even more controversial figure; even to the Reformed pastors in the city. She continued to write, and conducted a funeral as no male pastors in the city were willing to perform the burial; an outrageous act for a woman.

29 Mozaik 29

Both of the former examples envision the emancipatory potential in literacy and forebode a much more empowered laity and to some extent shows what could have been regarded as the empowering of women in a religious context. The Reformation opened a window of opportunity for women to express themselves publicly on religious matters. However the window closed again as the new churches became more organized. Regardless, the cornerstone for later emancipation and empowerment had been laid, due to women’s required literacy to raise and teach the children.

Just to mention two other women who used the window of opportunity to express themselves on religion, and to interpret the faith for others, I’ll point to Marié Dentière; who lived most of her life in Geneva fighting for John Calvin’s reform, and later quite controversially for womens’ right to preach, and Olimpia Fulvia Morata; daughter of an Italian scholar, and highly educated in languages and religious matters, who, had she not died 28 years old, had the potential to become a beacon for women’s possibilities in society and empowerment on religious matters.

Teresa de Avila - The empowered nun

Within the Catholic Church the convents were options primarily for noble women to escape marriage, and a possibility to study as well as express themselves. Before the Reformation the closure of the convents was not as strict as after the Catholic Reformation following the Council of Trent. In some convents, women were allowed to walk the streets, and in most the nuns were able to receive and talk to visitors.

This changed after the Council of Trent, and the Closure became very strict. The nuns were not to be seen or see the outside world. They were only allowed to talk the other nuns and to a priest during confession.

After the Council, Teresa de Avila founded the Discalced Carmelite convents. She envisioned a convent physically enclosed but with the possibility for the enlightenment of the nuns. She adhered to a strict poverty shared equal by all in the convent and the prioress. The prioress received an enhanced role, as spiritual teachers, healers and guardians for the nuns. In other words, the position of prioress provided a possibility for women to become religious leaders. Admittedly a possibility for a very few women, to be a leader of women, but in the early years of the Discalced order, it was a very powerful position that granted a lot of autonomy, that later on was obtained.

30 Jens Christian Kirk: Woman and the 16th century

Conclusion

In the 16th century, a window of opportunity opened for women to express themselves, teach and interpret Christianity, both in the areas where Luther’s and Calvin’s reform caught on, and in the areas that remained strictly Catholic. This window was closed again as the Protestant churches became more organized and the Catholic Church reacted theologically on the new situation at the Council of Trent. In some ways, the possibilities in the late 16th century for women to express themselves were poorer than before the Reformation due to the abolishment of the monasteries in the Protestant areas, and the more strict closure in the Catholic areas. As literacy spread among the laity, also among women, the cornerstone for a later movement for women’s emancipation were laid. █

Further Readings:

Stjerna, Kirsi, “Women and the Reformation”, (Blackwell Publishing: Malden, 2009).

Evangelisti, Silvia, “Nuns: A History of Convent Life”, (Oxford: 2007).

Parker, Holt (ed.), “Olympia Morata: The complete writings of an Italian heretic”, (2003).

McKee, Elsie Anne,“Katharina Schütz Zell, Vol. 2: The Writings, a critical edition”, (Leiden: Boston, 1999).

Weber, Alison, Spiritual Administration: Gender and discernment in the Carmelite Reform, “The Sixteenth Century Journal”, v. 34/3, (2000) pages 123-146.

31

29

Mozaik

Marta Gustavsson the eschatological closet

Marta Gustavsson the eschatological closet

Eva Danneholm From the Archives

Eva Danneholm From the Archives

JoAnne Lam

JoAnne Lam

JoAnne Chung Yan Lam

JoAnne Chung Yan Lam