World Student Christian Federation Europe Region Ecumenical Journal, 2013/Solidarity

31

Who is my neighbour?

Mozaik (established in 1992) is the ecumenical journal of the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF, 1895) Europe Region, published two to three times a year. It aims to reflect the wide variety of opinions and viewpoints present among the different Student Christian Movements (SCMs) in ecumenical dialogue. You can find us Online at wscf-europe.org.

This issue of Mozaik follows the Solidarity conference “Who is my Neighbour?” which was jointly organized by WSCF Europe and Religions for Peace - European Inter-Faith Youth Network. The conference was supported by the European Youth Foundation of the Council of Europe. The contents of this publication reflects the views only of the authors and not the opinions or positions of WSCF as a whole, the editorial board, Religions for Peace – European Inter-Faith Youth Network, or the Council of Europe. Neither the Council or Europe, nor the other donors can be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Editor-in-Chief:

Paweł Pustelnik (Cardiff, UK)

Editor:

Miro Pastorek (Slovakia)

Art Editor:

Mária Bradovková (Slovakia)

Address:

Storkower Straße 158 #710 D-10407

Berlin, Germany

ISSN 1019–7389

Illustrator:

Rebecca Foster (Manchester, UK)

For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same?

I learned very quickly that when you emigrate, you lose the crutches that have been your support; you must begin from zero, because the past is erased with a single stroke and no one cares where you’re from or what you did before.

Don't forget to show hospitality to strangers, for some who have done this have entertained angels without realizing it!

― Hebrews 13: 2

1 Mozaik 31

― Matthew 5:46-47

― Isabel Allende, Paula

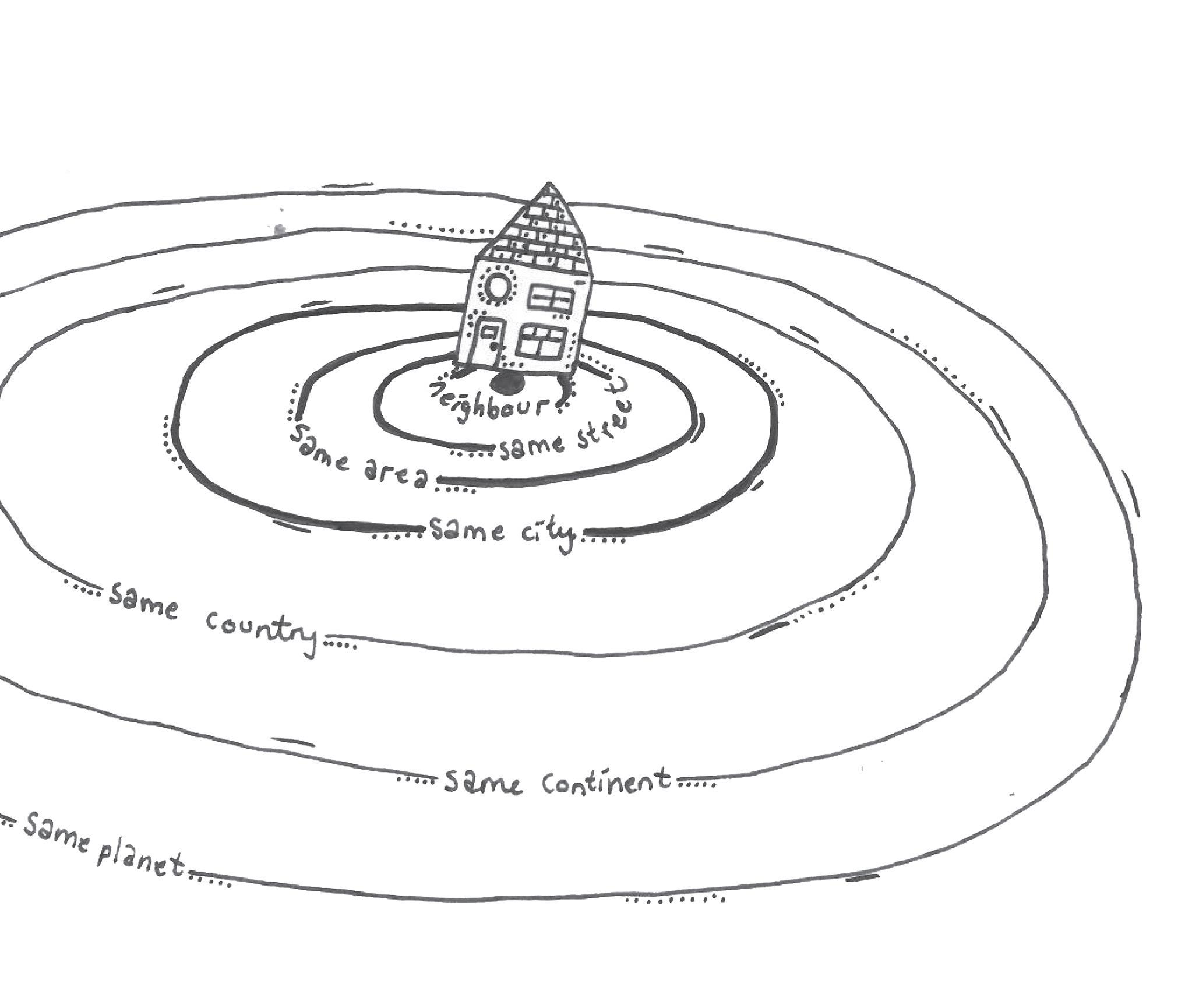

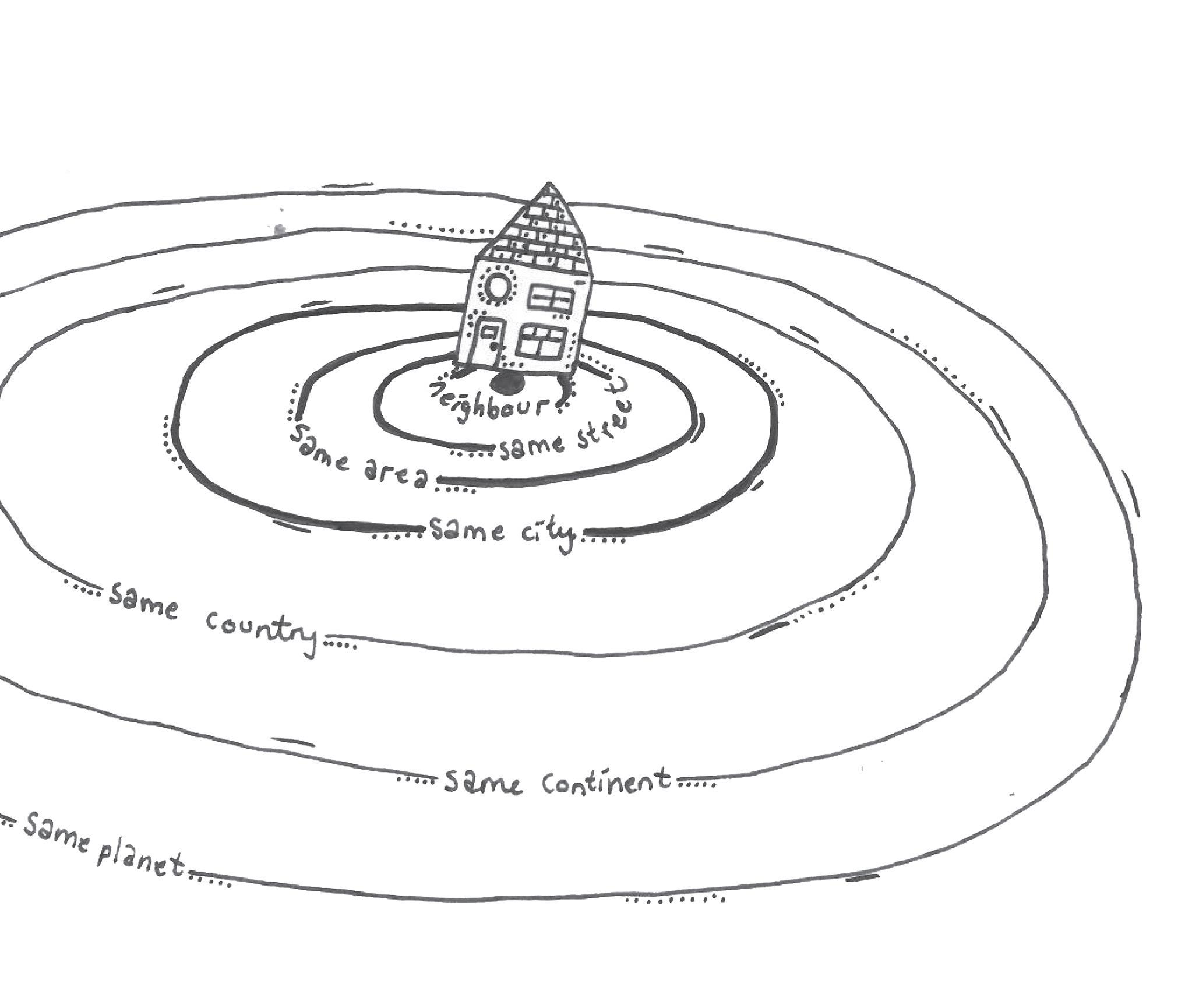

Sometimes the context we live in is taken for granted. A reflection about the people who surround you is crucial and probably the first step to overcome prejudices.

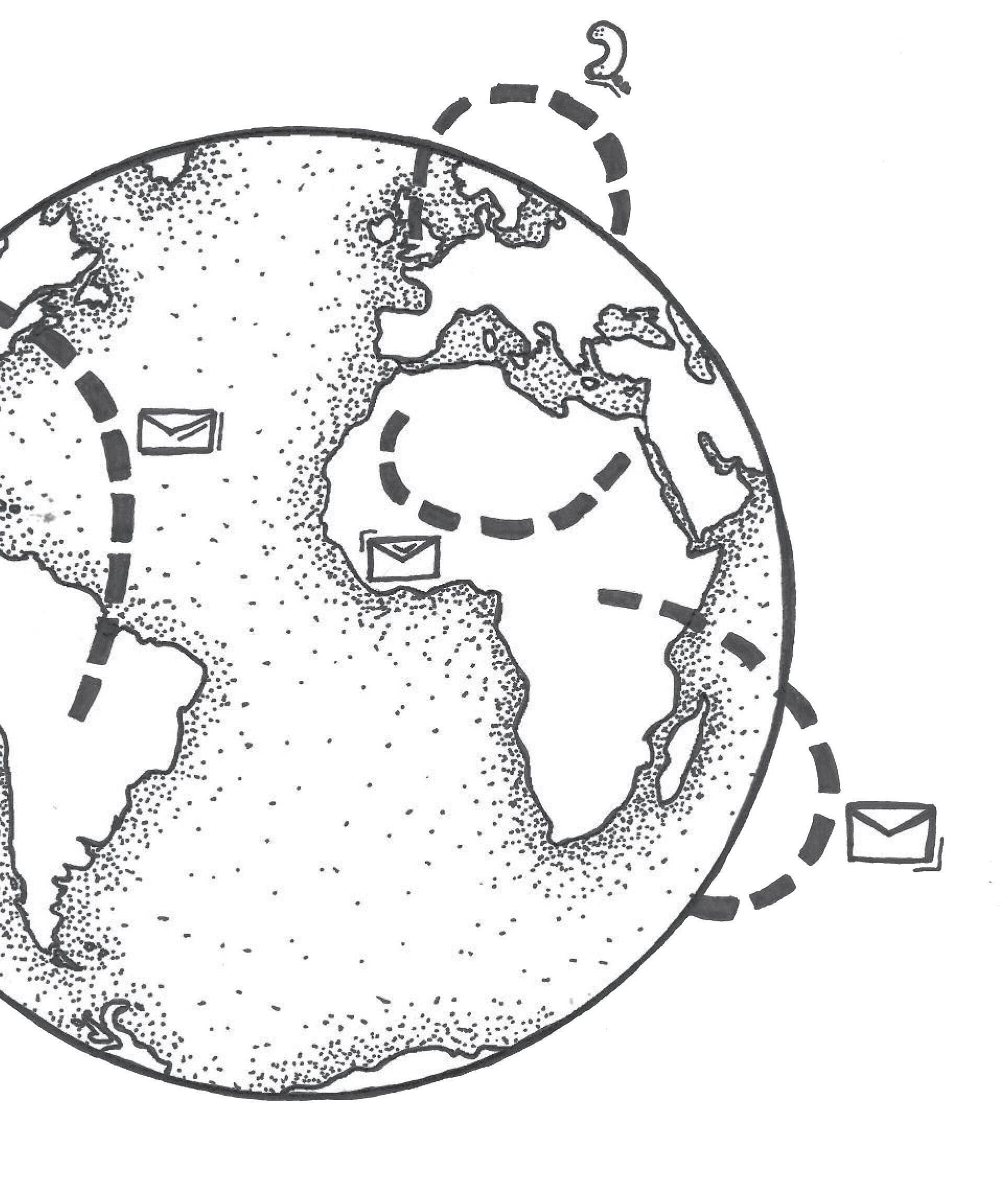

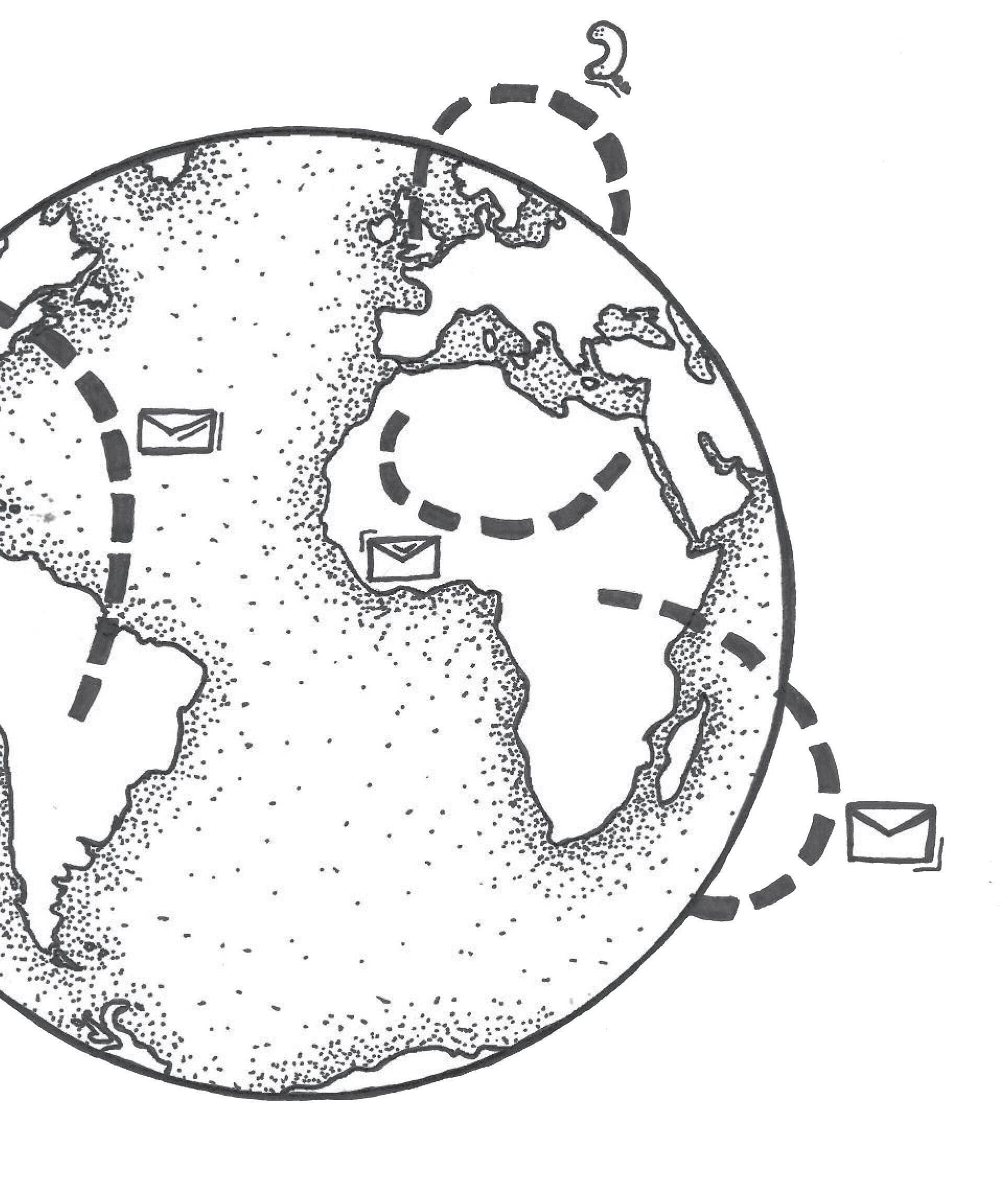

The world is becoming hypermobile. Some years ago migration was associated mostly with people’s mass movement related to wars or with a little number of experts moving from one country to another. Today, migration has many new facets. At many WSCF events at the ice-breakers session we ask people to raise their hands if they came from the country where they live, if they used to live abroad or if they live in the same place where they parents or grandparents used to live. The picture, perhaps a bit blurred, that we are getting usually shows a highly mobile group with one or more international experiences, showing that almost nobody lives in the place where their parents (not to mention grandparents!) live. Paradoxically, in the reality where cultures intersect and mingle people can still experience xenophobic behaviours of diverse characters.

In this issue we are trying to look closer at the European perspectives. The conference, which covered the issues related to xenophobia was organized in Italy – a country known for its rich history full of migrations and new neighbours. Recently, the Italian coasts have become an area of conflict between dreams and reality. The African compasses calibrated for the promised land point towards North, which means that more and more people of all ages head to Italy hoping for a better life. This trend and the links we had in Rome made WSCF think of Italy as a perfect venue for the conference “Who is my neighbour?” An intense week is vividly described by Annika Foltin, who was co-organizing the event. Hattie Hodgson and Jo Musker offer compelling contributions related to their experiences with human trafficking and xenophobia in Great Britain. Márta Várnagyi, who was also present in Velletri as WSCF Events Coordinator, had an opportunity to talk with her Hungarian friends about xenophobia in their country. Shannon Philip asks “Why do we call ourselves Christians, men or women, gay or straight, black or white?” and tries to understand the roots of fear of the other.

There were many conclusions that we came to in Velletri. It has been an eyeopening week, for some overwhelming, but for sure worth travelling many kilometers. We are trying to give you a taste of the issues and encourage discussions in your environments. Who are YOUR neighbours?

2

EDITORIAL |31

Motion of acceptance

– Marta Gustavsson, Jonathan Wiksten

No Country for Roma People

– Márta Várnagyi

Stories of experiences of community and solidarity across lines of culture and religion

– Bashy Quraishy

Xenophobic…me?

– JoAnne Lam

The New Asylum Model in Britain and the rise of Xenophobia

– Jo Musker

Loving our neighbour? It might be more difficult than you think…

– Hattie Hodgson

Islam and immigration are no strangers to one another

– Ibrahim Mogra

Free-time activities as tools of intercultural integration

– Csaba Szikra

Am I a xenophobe?

Being a progressive Christian student today

– Shannon Philip

The New Italians

– Marta Maffia

3 | Federation

Central & Eastern European SCM Training

– Viliam Latta

How is it to be in a Preparatory Committee?

– Annika Foltin

Like a Paddington bear

– Nino Kurtanidze

Refugees and the Future of Europe

– Jos Kofijberg

Green Toolbox is available NOW!

3 Mozaik 31

6 8 12 18 20 26 30 36 40 44 50 52 56 58 62 1 | Know 2 | Act

No fiction, no myths, no lies, no tangled webs – this is how Irie imagined her homeland. Because homeland is one of the magical fantasy words like unicorn and soul and infinity that have now passed into language.

― Zadie Smith, White Teeth 6

Islam and immigration are no strangers to one another

4

1 | Know

Motion of acceptance – Marta Gustavsson, Jonathan Wiksten 8 No Country for Roma People – Márta Várnagyi 12 Stories of experiences of community and solidarity across lines of culture and religion – Bashy Quraishy 18 Xenophobic…me? – JoAnne Lam

New Asylum Model in Britain and the

– Jo Musker

20 The

rise of Xenophobia

26

– Hattie Hodgson

Loving our neighbour? It might be more difficult than you think…

30

–

Ibrahim Mogra

Paulius Sakalauskas

All together in Velletri.

Marta Gustavsson Jonathan Wiksten

All together in Velletri.

Marta Gustavsson Jonathan Wiksten

Motion of acceptance

Blonde hair is surrounding the wounded, bleeding face on the sticker. Mass immigration. Not only pizza. I have to read a second time before I get the message. The message proposes the beating is a consequence of "mass immigration", a phrase that is heard with increasing frequency since the Sweden Democrats1, a populist right wing party took place in parliament. I prepare to cross the road, as I'm struck by the thought: Why should I let the message reach anyone at all?

If you tolerate this is one of the songs I like the most by the Manic Street Preachers. It's about the Spanish civil war, and about the victims of fascism, then as well as today, but there is one line that disturbs me. ”If I can shoot rabbits, then I can shoot fascists”. One night I have some friends over for dinner and one of them makes a joke about thieving immigrants. I am reminded that racism is part of our culture, not something that only some scary uneducated fascists are doing.

After work on All Saints' Day I am walking home from the graveyard where I had met with some people paying their traditional visits to their families' and friends graves. I pass by the small river, when I see the stickers again. Mass immigration, a ticking bomb, says one. Mosques in Sweden? No thanks! Proclaims the other. On every trashcan in the area, I can read the racist messages

6

1 Sverigedemokraterna, best translated as the “Sweden Democrats” is a populist right wing party with a social conservative agenda. They have roots within the far right and remain heavily sceptical towards immigration and have an ambigous attitude towards other minorities. Some analysist have compared their agenda with fascism, but towards the public they maintain a sober appearance.

of different far-right networks. As well as I can I tear them all down. Some people pass me as I stand with my clergy shirt. I hope they understand why I scratch so eagerly.

”How much immigration can Sweden take?” This is the theme for a debate on national television. Immigration is a problem, the statement is posed as an axiom, an unquestionable truth with two sides or answers: more or less immigration. How much can we all adjust to racist questions like that? Why isn't another perspective heard, the voice declaring all the things diversity means to us, the priceless value of an open society?

My peers at University have a unanimous contempt for the right wing populists. Their answers to the problems of political life are ridiculed. Who takes these people serious, who votes for them? Another scandal among many surfaces, this will surely mean that they disappear. Three leading radical right wing politicians belonging to the Sweden Democrats have filmed themselves in a quarrel with a migrant comedian, calling him names and denying his right to a Swedish citizenship. A woman interferes and now they turn on her. The film is released now, two years later, and several leading figures are forced to resign.

In the coffee room we are talking about the way people adapt to society's views of them, how the heritage or culture is not a problem as big as the way an immigrant is faced in our society. We discuss the risks of our prejudices. At least, I think that is what we discuss, when the discourse suddenly turns. “But sometimes, they have themselves to blame” a colleague says and portrays some Roma man (that means, not necessarily an immigrant) who “destroys it for all the others” by behaving bad. Failing to communicate the logical gap in her argument, I do my dishes and leave the room.

The next opinion polls arrive. Is it just the winter cold or did the climate in society actually grow colder? I pull my collar up to cover my ears and duck away from the icy winds blowing trough the streets. The Sweden Democrats have gained increased support and now have the support from twelve percent of the people. Are we so disillusioned that we allow violent drunkards in parliament or did the party even look cleaner when the perpetrators were rooted out from the party line? Did some people like what they see: a demonstration of the majorities power over the minorities? Were politicians finally saying what everyone was thinking? �

Jonathan Wiksten is a Swedish student of European Studies at the University of Gothenburg. He is also involved in fair trade issues and particularly the possible future of fair electronics. In the future Jonathan would like to work as a writer, an independent researcher or a community organizer. Mozaik 31

7 Mozaik 31

Marta Gustavsson is an ordained pastor in Church of Sweden.

Márta Várnagyi

No Country for Roma People

Caution! A discussion below is charged with subjective experiences and views on the situation and conflicts related to the Roma minority in Hungary. Your critical eyes might be needed there to read and rethink! The conversation could be used as a resource material for discussions as well.

Normally you can hardly embarrass a Hungarian by asking questions. Even complaining about wages or about your illnesses, after or even before getting to know the others names, those topics are not belonging to the taboo zones for a Hungarian person in general. But if you ask: What do you think about the Roma people –you are risking getting into a very passionate discussion. Somehow, you avoid the question even at home if you want to finish the Sunday supper without a conflict.

I asked three young Hungarians how they see that issue. Is that a matter at all? I was looking for answers together with Andrea (28) a student of English literature, Katalin (32) a journalist, and Balázs (29) an IT support person. Once seated in one of the typical cozy cafés in the inner city of Budapest, my interviewees, who I know from the university asked me to use fake names for them. My first question to them was almost given:

8

Last week I was named “a dirty Jew” by couple of young men. It was during the day, on a crowded street, probably because of an unusual colorful outfit I was wearing.

9 Mozaik 31

Márta: What are you afraid of?

Balázs: There is a real danger. I am sometimes really afraid in my everyday life, although I am not belonging to any ethnic minority. Probably just to a political one, as I am rather thinking in a liberal way. Many people would immediately consider me as anti-Hungarian for this approach. I was threatened on Facebook as well.

Andrea: I know what Balázs is talking about. I have been there too. Exclusion and intolerance is not only in Nógrád (county in the north of Hungary where the Roma population is the highest comparing to the other areas of the country) but here in the capital it is present as well. Last week I was named “a dirty Jew” by couple of young men. It was during the day, on a crowded street, probably because of an unusual colorful outfit I was wearing. I was leaving the library with some books in my hand. I pretended I could not hear them. Now I can imagine that everyday life must be very tough for people who look different than most of the Hungarians.

Katalin: Indeed, there are sometimes very difficult situations. My father is African, and some people who never seen Africans think that I am gipsy1. One old woman in a supermarket accused me without any reason that I was standing near hear at the cash because I wanted to steal the products from her basket. It was very humiliating.

Andrea: There are these stereotypes about the gipsies that they just do not want to work, therefore it is very difficult to overcome this image for the ones who would really like to change. I had a gipsy roommate in the dormitory and a family friend, a musician, but I never came to the idea to connect the gipsy stereotypes with them. They wanted to study and to work.

1 In Hungarian, according to the political correctness the word Roma is used, but gipsy is not necessarily a pejorative or negative expression like in English, but rather charged by a colloquial, everyday sense of the term.

Márta: What could be the reasons for the stereotypes you mentioned?

Katalin: You did not prepare easy questions, did you? Well, I think most of the Roma people, even that they are not a homogenous group, are living according to very different traditions and social realities than most of the Hungarians do. Just to name an example, in many communities girls are only counting as “somebody” if they marry until 16 and give birth to a child. This pattern is not easy to fit in the system of education and work. Even after the socialist era the traditional skills disappeared for Roma people and they had to survive by other businesses, living out of illegal activities. The generation growing up now brings these patterns as examples.

Andrea: Obviously, everyone seems to know that the key is education.

Balázs: Yes, but somehow there are very few successful programs. My mother was a nurse in a kindergarten. She told me about an education program that failed during the socialist regime. In the 80’s gipsy children of very poor background were getting placements in a dormitory, close to the school. The problems started as the children did not want to go back to the poverty. Their families were afraid of loosing contact with their children. Consequently, the families would not not let them go back to school. Obviously, if one does not want to change, then she or he can not be changed, neither by an individual NGO nor by a group of politicians.

Andrea: I don’t agree, it is not only a question of a decision. This is a vicious circle. Roma children who are already in schools are facing lots of difficulties such as circumstances at home, or simply the fact that they have to work at home and that they do not have energy for the rest of the day. Even if these students graduate, they will be hardly hired by anyone. OK, there are exceptions, of

10

Márta Várnagyi: No Country for Roma People

course. In one of my previous jobs there was a Roma guy, very intelligent and a good worker, but at the company party he could not avoid to listen the colleagues’ stories and jokes on gipsies.

Márta: What else could be done?

Balázs: Maybe we have to rely more on the law? I wish to see more actions to strengthen the social inclusion. Try more education programs. And forbid and punish the violence and crime, no matter who committed it.

Katalin: I think that the churches are not speaking up loud enough to reduce the intolerance and underline the teachings of Christ, that everybody is your sister and brother, nobody is an exception, neither the ones we like or we are afraid of. I do not really understand, and I feel ashamed of that, that certain denominational communities are not separating themselves from right extremist groups and they mix up national values with social exclusion.

Andrea: Yes, there is much to do from the side of the state, or the church. I agree. But we are all responsible to establish a discourse and express sympathy or disagreement.

Thank you for your thoughts and shared experiences!

When Márta Várnagyi is not reading, hiking or planting, she is studying an International Relations Masters in a German language University in Budapest, writing articles and taking a slow speed PhD in literature theory in contemporary feminist literature criticism. Márta serves as well as the gender programme coordinator on WSCF European Regional Committee. Email: eventscoord2@wscf-europe.org.

11 Mozaik 31

�

Bashy

Quraishy

Bashy Quraishy was a speaker at the conference in Velletri. He delivered also a workshop related to xenophobia and situation of Muslim communities in Europe. Below you can find a script from a Q&A session with him.

Stories of experiences of community and solidarity across lines of culture and religion

What such experiences can you think of and (how) did they transform the general relationships between broader society and Muslim communities?

I would like to share with the delegates a very personal and emotional as well as practical experience in building co-operation between Jewish and Muslim communities. Jewish and Muslim communities in Europe have been part of the diverse societies for generations. They both have shared ups and downs in the history of this continent.

I had a great personal experience in Israel, which changed my life and was the reason the Jewish organization CEJI and I took the initiative in 2005 to launch the Jewish Muslim Co-operation Platform in Europe. A sort of people-to-people contact.

12

It became clear that partners in this dialogue should come from the whole spectrum of European Jews and Muslims, the main requirement being that they be willing to collaborate.

13 Mozaik 31

Which were the specific barriers that existed and that were overcome in these situations?

In order to move forward, we looked at the common prejudices and ignorance both communities have.

Since a true understanding between people cannot happen or function in a vacuum, there was a need to fulfil some basic requirements, if the wish to have a longterm friendship and enjoying each other’s cultures had to materialize. Then there was also the question of how could accept and respect be developed between two communities in a cohesive manner?

The most common stereotypical categories of Muslims

• Religions fanatic and militant

• Hard-headed and ill-tempered, uneducated and unsophisticated

• Wear headscarves and keep long beards

• Practice patriarchal family system, oppress women and children

• Culturally traditionalists

• Want to live in ghettos and do not want integration

• Support Jihad and are involved in terrorism

• Hate all non-Muslims and regard their women as prostitutes

• Reject modernity and hate progress

• Want to establish a Muslim empire (Khalifat) instead of democracy

The most common categories of stereotypes of Jews

It was also important to assess, as to what kind of concrete actions would enable both communities to become better acquainted with each other and to discover and communicate their cultures, their customs, their history and their present situation? For that to take place, a coordinated effort was required, as well as certain steps were to be taken, to not only accept and respect the co-existence between Jewish and Muslim people, but also enhance understanding and knowledge about each other. That also required a direct dealing with one’s own prejudices and obtaining a clearer sense of identity and cultural awareness. Examining of self makes it easy to confront the societal prejudices, lay framework for social action and open the doors of respect.

• Intelligent and arrogant

• Efficient traders and artists

• Greedy and love money

• Hold on to customs & separate identity

• Consider themselves the Chosen Ones

• Look different

• Priggish and scheming

• Are anti-Islam and want to destroy it

• Control the media, banks and the politics in many countries

• Zionists have planted Israel to control oil and built a greater Israel

Bashy Quraishy: Stories of experiences of community and solidarity across lines of culture and religion

14

For a fruitful and lasting dialogue and to create a progressive interaction between Jewish and Muslim people, two vital and controversial factors were looked at closely and agreed upon:

• De-linking of the Middle East conflict from European issues of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia

• Practice of neutrality by intellectuals and academics among Jewish and Muslim communities in Europe, when European societies discuss Islam, terrorism or Middle Eastern cultures and Israel

How was that possible and what did it take?

An initial steering group of Jewish and Muslim individuals with experience in dialogue was started in 2005. To find out about developments in the field, CEJI established local contacts. These used a network of activists on the ground to create Mapping Reports, which were completed in 2006 for 5 European countries. It should be noted here that while some mapping exercises and surveys of antiSemitism and Islamophobia have been carried out, for example by EUMC, now the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, there was essentially no information on dialogue initiatives between the Muslim and Jewish communities.

The Mapping Reports, while not exhaustive, were therefore an important first step towards discovering grassroots activism. We were pleasantly surprised to find that there are many positive activities. This demonstrated that many Jews and Muslims are eager to meet and discuss issues that concern them.

These examples of practice on the ground were published in the Mapping Reports, to empower and encourage

other people, and also to raise attention for them in the European institutions. These reports are intended to be a source of inspiration for what is possible elsewhere, as they can pave the way to the creation of new projects, based on experiences by other activists.

In April 2007, the first-ever European-level Conference on Jewish Muslim Dialogue was held. 70 grassroots dialogue practitioners from the 5 countries participated, coming together in Brussels to network, exchange ideas and conduct dialogue. Good and bad experiences were shared so that existing work can inspire and motivate other initiatives and to help prevent mistakes from being repeated.

Moreover, the conference was a chance to showcase grassroots initiatives to the European institutions, an especially relevant aspect in the run-up to the European Year 2008 on Intercultural Dialogue. Based on the Commission’s interest in the conference, and on the attendance at the November launch of the Platform, we think we have taken a real step towards the goal of raising awareness among European-level officials that local activities are key to promote dialogue and interaction.

Besides the political aims of the platform, we also struck a chord with the delegates, based on their own feedback, leading us to think that the conference should not be

15 Mozaik 31

Building alliances with other faiths, supporting of inter-faith work and standing up for discriminated and disadvantaged individuals and groups, no matter who they are, whom they worship and how they look like.

a one-off event. Thus, one of the outcomes of the conference was the creation of a Steering Group, which brings together people from all the countries involved, hoping to lead the way to more and deeper collaboration. We have already established partnerships with Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, and we have identified partners in Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. Building and enlarging the Platform is a slow but necessary process based on consensus. As the saying goes: Rome was not built in one day.

It requires continuous interaction, openness and mutual exchanges between these two groups not only on religious level but on all levels – exchanges between schools, youth clubs, religious leaders, NGOs, literary personalities etc

How can people be empowered to achieve this? And what does that mean for the home contexts of our participants?

While there are many local dialogue initiatives throughout the European Union between Jews and Muslims, these generally remain grassroots projects with little visibility at the European level. But there has been a lack of sustainability and there was no overview of the activities or exchange of good practices. Keeping in mind the anti-Semitism and Islamophobia in Europe today, this situation required mending. The logical next step was for Muslims and Jews to join forces, for the good of their people and also to create harmony in society.

• A mutual enrichment based on equality between 2 religions and communities

• Fundamental changes in institutional thinking, schools books texts, and individual/ group language terminology

• Correct and objective media portrayal of each other

• Redefinition of social norms, thought processes and actions, which encourage or reinforce arrogance, domination and intolerance

• Provision of necessary conditions, which will allow these 2 communities to practice their civil rights in peace

• Legal protection against discrimination and injustice of all types and forms for both Integration instead of marginalization

To fill that gap, CEJI – A Jewish Contribution to an Inclusive Europe brought together Jewish and Muslim NGOs and resourceful individuals.

They met and discussed the needs of the two communities and how the communities could support each other, in the meanwhile fighting prejudices and replacing them with respect and acceptance. Since a dialogue was crucial, the suggestion to establish a European Jewish Muslim

Dialogue Project was enthusiastically taken on board. During the discussions, it became clear that partners in this dialogue should come from the whole spectrum of European Jews and Muslims, the main requirement

Bashy Quraishy: Stories of experiences of community and solidarity across lines of culture and religion

16

being that they be willing to collaborate. Since it was not intended to be a matter of comparing notes on theology, we had to start with a meeting of hearts to win over the minds.

• Building the foundation for a dialogue with face to face meeting

• A clear concept of one’s identity

• Cultural/religious awareness through mutual respect

• Examining prejudices – self and societal

• Confronting prejudices - self and societal

• Social action and responsibility through a transforming dialogue. This can only be done by creating a space where use of a respectful language is essential

In short, building alliances with other faiths, supporting of inter-faith work and standing up for discriminated and disadvantaged individuals and groups, no matter who they are, whom they worship and how they look like. This is the need of the time, this is what humanity is calling for and this will surely make our creator – man or woman – happy. �

Bashy Quraishy was born in India, but grew up in Pakistan and today he lives in Denmark. He studied Engineering in Germany and USA, and later studied International Marketing in London. He is a member of a number of Commissions and Working Groups involved with human rights, ethnic equality issues and anti-discrimination work, both in Denmark

and abroad. He is the Secretary General of EMISCO -European Muslim Initiative for Social Cohesion. Bashy is also the author of seven books on Ethnic Minorities in EU, Racism, ethnic equality, Pakistani community in Denmark and Western media’s coverage of Islam.

17 Mozaik 31

JoAnne Lam

Xenophobic....me?

From an early age, we develop the concept of "best friends." These are the people with whom we are vulnerable and accepting. These are the people that we care about and love. This is a part of our "in-group." When there is an "in," there is an "out." Little do we know that as soon as there are lines drawn, boundaries set, we are isolating ourselves. You are correct. I wrote isolating ourselves. Wars and political conflicts are the most obvious xenophobic behaviours and attitudes. During the Second World War, girls and women from Korea, China, Japan, Philippines, and other Southeast Asian countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army were kidnapped or ripped from their families and placed into forced prostitution. Xenophobia is the fear of the "Other," the foreigner, the stranger.

To see another person firstly as human and second as a skin colour, foreign accent, scents and smells etc. would possibly be the up-turning approach to our ways of behaving with one another.

Some may suggest that war has an effect on the humanity of individuals. Instead, I would say fear impacts our humanity and the recognition of humanity in others. In times of war and political conflicts, women and children receive the most traumatic impact of such xenophobic behaviours and during WWII, it has become one of the

18

most horrific expressions of it. These "Comfort Women" were stolen from their families, often they were young girls and then placed into camps where they serve anywhere from 6 or 7 up to 60 men daily. Such vulgar and inhumane treatment of another human being, foreign or familiar, male or female, young or old, is simply unacceptable and incomprehensible. On the one hand, the Japanese military was taking captives, but more importantly, the intention was to insult and violate the occupied peoples whereby from that moment forward, the Japanese "seed" has eternally infiltrated into the people of Korea, China, and so on. The fact was that most of these young women died from disease and inhumane treatments rendered this possibility slim, but women are the source of life in any community. To slaughter or violate them in such a way is to perform a genocide that is eventual and certain. The reasons for war are complex and greed and fear are two of the major components in that equation. We fear the "Other" will attack us and steal from us. We fear the "Other" will disrupt our sense of security and peace. Selfcenteredness and egocentrism create a constant state of fear that inevitably end in conflicts because in our limited human capacity, only in the elimination of the "Other" will there be peace. Unfortunately, that is neither true nor reasonable. When our "in" circle becomes smaller and smaller, the level of external threat increases and fear continues to constrict our ability to be open and hospitable to the surprising experiences waiting for us outside of our prisons of self-protection.

My most recent xenophobic experience was in Turkey or in the preparation of going to Turkey. As always, I would research about the country, the cuisines, and tourist attractions. As this was a study tour with the seminary, the itinerary was set and not much worried me. However, through an Internet search, there were numerous items stating the political turmoil Turkey was experiencing as well as the Islamic influence in this country. All of a sudden, sirens rang in my head and anxieties rose to alarming levels. What should I do to

protect myself? Would "they" be discriminatory because I am an "outsider?" After weeks of concern, the reality of a welcoming and hospitable Turkey called me to critique my xenophobic tendencies. Despite not knowing anything concrete or factual about the country, I had created a fantastical version of a country that would also exhibit xenophobic attitudes. Perhaps a psychoanalysis of my emotional state would explain my sources of insecurity and fear, or maybe not. This aspect of human limitation brings greater awareness to my biases and prejudices. On a positive note, one of the Muslim guides from our study tour has become one of my close friends since our study tour around Turkish historical sites.

Stereotypes and assumptions act as steel walls that separate us as one humanity. The unity in our humanness may be the antidote to our creation of "in-groups" and "out-groups." To see another person firstly as human and second as a skin colour, foreign accent, scents and smells etc. would possibly be the up-turning approach to our ways of behaving with one another. To be human is to recognize our brokenness, our frailty, and our ability to be cruel and excluding. In changing our current world paradigm and being witnesses to the God who created all creation, maybe we should start greeting the "Other" in a hospitable embrace of grace. �

JoAnne Chung Yan Lam is a Master of Divinity student at the Waterloo Lutheran Seminary in Canada. Her internship year will begin at St. Peter's Lutheran Church in Ottawa as of September 2013. She has served as an intern at the WSCF-Geneva office in 20022003. She received a MTS from the Toronto School of Theology and MAS from the Ecumenical Institute of Bossey. Her latest project is researching the historical developments of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem as a part of her Study Tour to the Israel and Palestine with her seminary. Her intercultural identity includes experiences in Hong Kong, Canada, and Switzerland. Email: ijklam@gmail.com.

19 Mozaik 31

Jo Musker

The New Asylum Model in Britain and the rise of Xenophobia

Over the last few months as one of Student Christian Movement (SCM) Britain’s Faith in Action interns, I have been working alongside asylum seekers and refugees to deliver awareness-raising sessions to organisations and services in my local community. We are working to equip others to challenge some of the xenophobic attitudes that have influenced Britain’s treatment of those fleeing their home countries to seek asylum in recent years.

The United Nations 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as any person whose life or freedom is under serious threat due to ‘race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion’.1 For those who have been forced to flee their homeland due to persecution, war or violence, the convention grants the right to protection in any of the 148 countries that have signed up to it, including Britain. The convention, originally established to protect European refugees after World War II, was extended worldwide in a 1967 Protocol and protects refugees from being forcibly returned to territory where their life or freedom will be under threat. For many years Britain has had a good reputation for providing protection to those fleeing torture and violence, but sadly this tradition is being threatened by the introduction of the New Asylum Model (NAM) in 2007.

1 www.unhcr.org.uk/about-us/the-uk-and-asylum.html

20

Asylum seekers do not have the right to work and are reliant on a small amount of government support whilst their case is being heard, but within 21 days of receiving a negative decision this support is withdrawn.

21 Mozaik 31

The main purpose of introducing the NAM was to fast track asylum applications to live in the UK due to the enormous backlog of unresolved cases and a general call to tighten immigration laws. The NAM’s aim to have asylum applications processed within six months is to be celebrated, yet unfortunately this push for more efficiency is costing many, many asylum seekers dearly. Asylum seekers arrive in the UK, often after very long and difficult journeys, and are required to almost

Last year there were over 11,000 refused asylum seekers who found themselves in this position and had to decide whether to return home, or to stay on in the UK to submit fresh evidence for a new appeal, in the hope of receiving a positive decision on their case.2 The forced destitution of failed asylum seekers is intended to encourage them to return home. However, each year thousands choose to

immediately give a full account of their situation to the government. With little time for recuperation, many struggle to feel safe enough to give full details of certain traumatic experiences, like rape and torture. Language and translation barriers can also make it difficult to obtain an accurate understanding of the asylum seekers’ situation, which can be detrimental to their case, especially as they are not guaranteed any legal aid in the interview. Language and translation barriers can also make it difficult to obtain an accurate understanding of the asylum seekers’ situation. This can be detrimental to their case, especially as they are not guaranteed any legal aid in the interview. As a result, many legitimate asylum claims are failed on the basis that the information given is not consistent. Asylum seekers do not have the right to work and are reliant on a small amount of government support whilst their case is being heard, but within 21 days of receiving a negative decision this support is withdrawn. Failed asylum seekers will find themselves destitute unless they choose to voluntarily return home with government assistance.

remain in the country simply because it is too dangerous for them to do so. In contrast to the quick initial decision on their case, failed asylum seekers will wait many years (up to fifteen) after submitting fresh evidence, to receive a new verdict on their claim. According to a recent report by Britain’s chief inspector of immigration, John Vine, there was at one point 100,000 items of unopened post sent to the UK Border Agency who handle the asylum claims!3 During this time of waiting for the Border Agency to respond, asylum seekers have to find a means

2

http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/science-research-statistics/ research-statistics/immigration-asylum-research/immigration-brief-q4-2011/ asylum

3 The Guardian, Friday 23rd November

22

With little time for recuperation, many struggle to feel safe enough to give full details of certain traumatic experiences, like rape and torture.

Jo Musker: The New Asylum Model in Britain and the rise of Xenophobia

to survive, often by living with a friend or working on the illegal market where they are vulnerable to exploitation. At any point they may experience dawn raids, detention in prison- like conditions for indefinite periods of time and forced deportation to their country of origin.

According to a recent report by Britain’s chief inspector of immigration, John Vine, there was at one point 100,000 items of unopened post sent to the UK Border Agency who handle the asylum claim.

It is deeply distressing to hear the stories of those who have fled trauma in their home countries, only to arrive in Britain to have to continue to fight for their lives. One story that particularly shocked me when I started my internship was of a man who volunteers with me who is originally from Afghanistan. He worked for the British Embassy there for nine years helping to protect Britons passing through the country, but he eventually fled to England with his family when the Taliban made two attempts on his life because of his work for the British. Despite this, he had his first claim rejected, and it then took over three years for this man and his family to finally receive their right to remain in the UK.

I am writing about my experience of the asylum process in Britain, but I am also aware that in other countries, life as an asylum seeker is even harder. Despite this harsh reality of life as an asylum seeker in Europe, however, media headlines about asylum seekers that feature in some of Britain’s most popular tabloid newspapers reflect hostility, rather than welcome, and suspicion rather than empathy; ‘Kick out this scum’,4 ‘halt this crooked tide’5 and, ‘asylum seekers are lured into this country by its enormous benefits’6. Over the last few months as a Faith

in Action intern, it has been tempting to become bitter and angry when I have encountered examples of this kind of hostility to the foreign Other, whilst working alongside the people who it directly affects. However, I am beginning to recognise that behind the media headlines that label outsiders as killers, cheats and benefit fraudsters, is a fear and vulnerability which is expressed in this language of lashing out.

Marshall Rosenberg, creator of a methodology of conflict resolution called Nonviolent Communication, writes about this kind of labelling of others as one of the most powerful barriers to peaceful and compassionate communication. Rosenberg argues that whilst human beings are naturally compassionate, conflict arises when we are vulnerable and have unmet needs, which can sometimes be unhelpfully expressed in the negative labelling and condemnation of others;

‘At the root of much, if not all, violence- whether verbal, psychological, or physical, whether among family members, tribes, or nations- is a kind of thinking that

23 Mozaik 31 4 The Daily Star, 2 March 2003 5 The News of the World, 30 January 2005 6 The Daily Mail, 21 April 2009

attributes the cause of conflict to wrongness in one’s adversities, and a corresponding inability to think of oneself or others in terms of vulnerability – that is, what one might be feeling, fearing, yearning for, missing’.7

Asylum seekers and refugees who travel to Europe participate in their own kind of exodus, yet for many their journey ends not in liberation, but in more struggle.

Behind the negative labelling of asylum seekers and refugees, one can often hear a fear for Europe’s own socioeconomic security. There is a deep sense of vulnerability, projected onto the outsider, behind objections such as ‘they’re taking all our jobs’ and ‘they’re stealing our tax payer’s money’. It can be difficult to hear the needs of another when many are themselves struggling for jobs and have an unmet need for the social and economic security we all desire for ourselves and our families.

This coming March, SCM will be marking the 40th anniversary of the SCM’s 1973 Seeds of Liberation Conference, by once again inviting students from all over the world to come together and explore what justice, particularly in the context of liberation theology, means for our world today. The story of the Israelite’s release from slavery in Egypt has been one of the key Biblical texts for the Liberation Theology movement, as a story of God delivering an oppressed nation into freedom in a new land. Interestingly, behind Pharaoh’s oppression of the Israelites and his labelling of them as outsiders, lay a fear also; 'Look, the Israelite people are more numerous and powerful than we. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them,

or they will increase and, in the event of war, join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land’ (Exodus 1:8).

Asylum seekers and refugees who travel to Europe participate in their own kind of exodus, yet for many their journey ends not in liberation, but in more struggle. What might liberation look like in this context today? For those seeking sanctuary, this may mean liberation from the years of living in limbo, waiting for a decision on their case, and from their experiences of suspicion of the outsider as reflected in the media. For those of us who already have our residence in Europe, liberation might mean a release from the fear that asylum seekers are here to take advantage of the system. If we know why the majority have come, what they have suffered, and how much they have had to give up to come here, then maybe this would elicit a more compassionate response to their pain. �

Jo Musker is an undergraduate student of English Literature and Biblical Studies at the University of Sheffield, and one of SCM Britain's Faith in Action interns. She has been working with asylum seekers and refugees since last September, raising awareness of the difficulties of life as an asylum seeker in Britain. Jo has a particular interest in international development issues, and has spent time volunteering with Church projects in Peru and South Africa.

24

Jo Musker: The New Asylum Model in Britain and the rise of Xenophobia

7 Marshall Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication, a language of life, chapter 1.

Testing of genuine Hungarian mustaches.

25 Mozaik 31

Paulius Sakalauskas

Hattie Hodgson

Loving our neighbour? It might be more difficult than you think…

Love your neighbour as yourself. (Matthew 22:39). It’s Christ’s second Greatest Commandment, and probably one of the most well-known sentences in the Bible. If you are anything like me, you have undoubtedly been considering it for years. You might even think that you have it all worked out — that, compared to some of Jesus’ other more metaphorical teachings, this instruction is fairly self-explanatory. My current work has indicated that, for me at least, this was anything but the case.

Through my work with Student Christian Movement (SCM) Britain, putting my faith into action, I am working with a professional network of organisations in the West Midlands area of England. These agencies are all working in different ways to bring human trafficking to an end. It is through this work that I have been pushed, once again, to consider what it means to ‘love my neighbour’.

Human Trafficking: the fastest growing international crime

Human trafficking is modern day slavery. It is believed to be the fastest growing international crime, second only in magnitude to the international drugs trade.1

1 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime as cited by Stop the Traffik, The Scale of Human Trafficking (2012), http://www.stopthetraffik.org/the-scaleof-human-traffiking [Accessed 28th Nov 2012]

26

A conservative estimate by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime indicates that 2.5 million individuals are victims of trafficking at any one time.

27 Mozaik 31

A conservative estimate by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime indicates that 2.5 million individuals are victims of trafficking at any one time.2

Trafficking can be thought of as possessing 3 elements: movement, control and exploitation. Trafficked victims are moved into situations of exploitation where they are controlled through force, coercion or deception.3

Trafficking occurs in nearly every nation on earth.4 It is not just a problem that happens elsewhere: there is substantial evidence of trafficking taking place into, within and out of European countries.5 In 2011 over 900 victims of trafficking were identified within the UK alone.6

How does this present itself?

It is hard to conceive how trafficking materialises itself. Consequently, a lot of commonly held perceptions are actually inaccurate. The following description, based on the anecdotal evidence I have gleaned from my work, and the international research, is an attempt to dispel some of these myths and explore how individuals are really moved, controlled and exploited in trafficking situations. For the sake of brevity and clarity, the circumstances described below usually pertain to victims of trafficking that are either older minorsi or adults—often the situation involving younger children is far more complex.

MOVEMENT

It is rare that the act of trafficking will commence with an act of ‘kidnapping’ with it being more likely that trafficked people are seduced into travel by job offers, gifts or the promise of a ‘better life’.7 Often individuals targeted by traffickers are facing poverty, discrimination or homelessness. It is only when they arrive in their new destination, or they are too embroiled to escape, that they realise that the promised outcome of their travel doesn’t exist. Once they are in the hands of the traffickers, trafficked individuals are often moved a lot, frequently being sold to other traffickers.8

CONTROL

Mechanisms of coercion often operate around money, with traffickers offering to pay for individuals’ travel and then treating this money as a ‘debt’ which the trafficked individuals must work to repay. In other cases, individuals are stripped of their passports so that, even if they did approach the authorities for help, they could not prove who they were. In the most extreme, but all too common cases, trafficked individuals are subject to violent threats, intimidation and abuse to ensure that they do not try and break away from their situations.

EXPLOITATION

The stories of trafficking that reach the press are often examples of young women or girls trafficked to undergo sexual exploitation. While a large proportion of trafficking does pertain to this particular type of exploitation, it is by

2 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Human Trafficking FAQs: How Widespread is human trafficking? (2012), https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/ human-trafficking/faqs.html#How_widespread_is_human_trafficking [Accessed 28th Nov 2012]

3 Steve Chalke, STOP THE TRAFFIK: People Shouldn’t be Bought and Sold, (Oxford: Lion Hudson plc, 2009), p. 10, UK Serious Organised Crime Agency, An Overview of Human Trafficking (2012), http://www.soca.gov.uk/about-soca/ about-the-ukhtc/an-overview-of-human-trafficking [Accessed 29th Nov 2012]

4 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report of Trafficking in Persons (2009), http://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Global_ Report_on_TIP.pdf [Accessed 28th Nov 2012].

5 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report of Trafficking in Persons (2009)

6 UK Serious Organised Crime Agency, Baseline assessment of human trafficking in 2011 (2012), Accessed from: http://www.soca.gov.uk/about-soca/about-theukhtc/national-referral-mechanism/statistics [Accessed 30th Nov 2012].

7 STOP THE TRAFFIK and United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Trafficking (UN.GIFT), DO YOU WANT TO SEE THE WORLD AND EARN GOOD MONEY? (2012), http://www.stopthetraffik.org/campaign/giftbox [Accessed 2nd Dec 2012]

8 Steve Chalke, ‘Noi’s Story’ in STOP THE TRAFFIK: People Shouldn’t be Bought and Sold (2009)

Hattie Hodgson: Loving our neighbour? It might be more difficult then you think…

28

no means the only way trafficked people are exploited. Trafficked individuals are also subjected to forced labour, forced street theft or begging, domestic servitude and even organ harvesting.

Loving our neighbour?

It is likely that there will be trafficked individuals being exploited within your city, town or community. I would argue that they are our neighbours as much as any other person. I am rapidly becoming aware, however, that ‘loving my neighbour’ in this context is fraught with difficulties. Extending love to trafficked individuals involves facing the very worst of human existence, and the very extremes of human frailty. It involves increasing the level of personal danger you face, in order that others may be safer. Through this work I am realising more than ever that Christ’s command to ‘love our neighbours’ is a call for us to stand with the marginalised, speak out for the oppressed, and do our best to protect the exploited. Are we ready to accept this call? �

i Minors are considered to be individuals under the age of 18, as per legislation from the United Nations.

Hattie Hodgson is a Faith in Action intern with SCM Britain and a recent graduate from the University of Leeds in the north of England. She is currently spending a year exploring what it means to truly put faith into action to work for justice.

29 Mozaik 31

Ibrahim Mugra

Islam and immigration are no strangers to one another

Ilivein the UK. I am an immigrant. My father also was an immigrant and my mother's parents were immigrants as well. Immigration is very much part of my personal story. I would like to share with you how we find migration and immigration at the very roots of Islam.

As you would know, Muhammad, peace be upon Him, God's messenger, began His preaching in Makkah, which is Saudi Arabia. His community and his society were idol worshippers. The idea of worshiping just one God seemed very strange and totally unacceptable to his people. As a result, they felt that this person should not be allowed to live with them; otherwise he will begin to move people from the worship of idols to the worship of the one true God. However, with every passing day, Muhammad was able to convince a growing number of people that there is only one being that is worthy of worship and that is God and all these idols are man made objects that cannot be God. As a result of a growing number of his community the Makkan people decided that enough was enough and Muhammad had to be stopped from what he was preaching. So they tried to limit and stop his activities. They carried out a social boycott of Muhammad and his family and followers; intimidation, discrimination and even physical attacks on his community.

When the pressure became unbearable, Muhammad decided that he would send a selected core group of

30

Islam and immigration are no strangers to one another. It goes to the very heart of Muslim presence in the world today.

31 Mozaik 31

Muslims to a distant country where they would become immigrants and (in modern term) asylum seekers. He was aware of a Christian country, Abyssinia, modern day Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa. There was a very kind and just Christian king, who was always helpful to the persecuted people, people who needed refuge and safety. In that knowledge, the first group of Muslims left Arabia and migrated to Abyssinia. This was one of the turning points in the history of Islam when a small number of Muslims was now safe from persecution and from certain death. However, not everyone was able to go. Once this delegation arrived to Abyssinia, they were warmly received, welcomed and were given a home.

an immigrant, a refugee; left Makkah and went to Madinah. This is what we the Hijrah. It is a very significant event in the history of Islam. So significant that we mark our year and our calendar from this event! Not from the birth of Muhammad, as Christians do with Jesus, but from this migration from Makkah to Madinah. It was the turning point in the history of Islam, because from that day onwards Islam simply grew in strength.

I find a wonderful connection here in the story of migration of the first Muslim immigrants and that of Christians in a Christian country of being hosts to these immigrants. And that clearly demonstrates to me that every single religion believes and teaches the offering of refuge and safety to the oppressed and the troubled people. I can say with every confidence that every single religion in this world believes that people who are oppressed must be cared for, must be supported.

This Christian king demonstrated the beautiful teachings of Jesus, peace be upon him, of caring for the homeless, caring for the poor and the oppressed and loving your neighbours.

Subsequently, those who were left behind began to suffer more, until the time came when Muhammad himself, peace be upon him, had to flee from Makkah. He became

Over a very short period of time (within 10 years)

Muhammad was able to return to Makkah and liberate it. But His story about becoming an immigrant and reaching what was then known as Yathrib, today known as Madinah, was an incredible experience. In Yathrib He was welcomed with open arms by the people who were living there. They were willing to be hospitable and give him refuge and sanctity. In fact, there is a beautiful song that the little children sang to welcome him into Madinah. When they saw him come over the horizon, the children ran out and sang this beautiful song.

Islam and immigration are no strangers to one another. It goes to the very heart of Muslim presence in the world today. Not only that. Even as early as the last century,

32

My personal history of being an immigrant comes from that background where Britain had colonised Eastern and Central Africa where I was born.

Ibrahim Mogra: Islam and immigration are no strangers to one another

before the industrialisation of the world, desert lifestyles revolved around migrating and immigration. At least seasonal immigration was very much a part of their lives. The Quran describes the travelling of the Arab tribes, looking for pasture for their herds, referring it to the journeys of the summer and of the winter. They were moving from one part of the Arabian peninsula to another looking for greener pastures for their flock. But then things changed dramatically. After the industrial revolution it was no longer about migrating patterns being on the back of agriculture or rearing of cattle. It became more to do with economic and financial well- being, with the more developed countries of the world began to attract people from less developed parts of the world. Indeed, the history of colonisation of many parts of the world by European powers created a relationship between Europe and the poorer part of the world, which did not cease even after those countries gained independence, because then there was a flow of populations from those colonised countries into the colonising countries themselves.

where they become one society and community, strengthening each other, making advancements both in terms of industry, education, culture and other aspects of life, including religious.

Where there is the true spirit of religious teaching, which is practised and implemented, societies flourish. Immigrants there also flourish along with the hostssometimes as well as the hosts. But when religion and the teachings of religion are not implemented and the spirit of those teachings is ignored, then we find that immigrants can have a very tough time. This is one of the sad eras within Christendom where Christian communities in some parts of Europe failed to be hospitable, particularly to Jewish communities. But all our religions have got these "dark spots".

My personal history of being an immigrant comes from that background where Britain had colonised Eastern and Central Africa where I was born. And so it happened that I then decided to move to the UK and settle in the UK. There have also been immigration and migration because of religious reasons, where a particular religious community was not allowed to practise its religion and so they had to leave and move elsewhere. Perhaps a glimpse of that we saw in Makkah with Muhammad and the early Muslims. We also saw a huge movement of Jewish populations from parts of Europe where they were not welcomed, moving into Muslim populated countries

From time to time religious people have failed to practise the teachings of their religions and because of that have created boundaries, especially for outsiders, newcomers, people who are different. Either different in religion, or culture, or skin colour. When we are unable to respect people of different religions, we create barriers and boundaries. When we are prejudiced, we want to deny others what we want for ourselves because of the different colour or religion. There is a deep rooted hatred for anything and anyone who is different. When religious people fail to embrace the teachings of religion that all humans are equal, then we find racism taking root. �

Shaykh Ibrahim Mogra serves as an imam and scholar in Leicester. He is a senior member of the Muslim Council of Britain. Ibrahim was born in Malawi into a family of Indian origin and emigrated to the UK at the age of 18 to study and settle. He has been trained in classical theology and the traditional sciences of Islam and has undertaken a postgraduate degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

33 Mozaik 31

Where there is the true spirit of religious teaching, which is practised and implemented, societies flourish.

All together in Velletri.

Marta Gustavsson Jonathan Wiksten

All together in Velletri.

Marta Gustavsson Jonathan Wiksten