13 minute read

Chapter Five Focusing on Construction

CHAPTER

Five

Advertisement

The mission statement for Weeks Marine is to be our clients’ premier choice in marine construction, dredging, and now tunneling with McNally.

Rick MacDonald

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT AND CONSTRUCTION DIVISION MANAGER WEEKS MARINE, RETIRED

Focusing on Construction

Ever since Weeks Marine first launched its expansion into the construction field, the size and scope of the jobs it handled continued to grow. As the team acquired equipment and hired additional staff members, it was able to tackle more complex projects, both domestically and abroad. Structures that we see every day—from bridges to oil fields to docks and beyond—were constructed under the watchful eye of Weeks’ expert team. As the company strengthened its reputation in the industry, Weeks grew to become one of the premier construction firms, handling both marine and land-based projects. It has amassed a wide range of equipment so that every type of job is expertly handled, and that has allowed Weeks to solidify its standing in the field.

In addition to its growing strength in the construction industry, Weeks would spend the late 1990s with a changing of the guard in terms of its executive leadership team. In October 1999, Richard S. Weeks was named

One of the most visible construction projects Weeks participated in was the replacement of New York’s Tappan Zee Bridge . The original bridge is pictured .

president of Weeks Marine, carrying on a tradition of leading the firm that went back to his great-grandfather, Francis Weeks. Richard S. set out to grow the business while still maintaining the atmosphere and environment that had been so important to his predecessors. The Weeks business would still remain in the family as it had been for decades, and would continue to flourish.

Tappan Zee Bridge

The Tappan Zee fendering system in progress . New York’s Tappan Zee Bridge, which allows cars to cross the Hudson River at its widest point, is a workhorse of infrastructure. More than 130,000 cars drive across the bridge every day, and safety is and has always been of paramount concern. In the 1990s, the bridge was badly in need of repairs, so Weeks embarked on a project to help increase the structure’s stability. Gene Kelley, who is the retired head of Weeks’ construction division, recalls how allencompassing the project was:

The scuttlebutt in the industry—and more than scuttlebutt—everybody knew that Tappan Zee Bridge had to be replaced sooner or later. The initial project was the fendering system for the main piers—the fendering system is for ship impact to avoid a disaster. And that’s a major commercial shipping route with oceangoing vessels going all the way to Albany. So the fendering system was important. Kiewit approached us in the early ’90s in anticipation of ultimately bidding together on the bridge replacement, which hadn’t come out. But there

1996

Weeks completes a project for the Ministry of Health in Barbados, West Indies.

1998

Weeks Marine acquires T.L. James, a dredging firm much larger than Weeks.

1998

Weeks undertakes a $50 million job repairing the Tappan Zee Bridge, which allows cars to cross the Hudson River at its widest point.

1999

Richard S. Weeks is named president of Weeks Marine.

was this major fender repair job. So we bid it with Kiewit, and that was around 1998 or 1999, and it was about a $50 million job. It was quite an elaborate fender system, and it was successful. And what we did is, because of Weeks’ equipment strength, we redesigned the fender construction method to use large, precast elements as opposed to conventional cast-in-place concrete. So we were able to cast these big segments off-site, bring them on-site, set them, and then post-tension them together as opposed to forming rebar and pouring concrete on-site, which, logistically, is tough when you’re at the river.

Because these types of repairs happen all year-round, Weeks did not have the luxury of operating only in warm weather, and had to deal with ice and below-freezing temperatures on the water during the project. Through the course of the job, Weeks developed a close working relationship with Kiewit, which continues to this day.

The project was also key for the team to get a firsthand look at the synergy between Richard S. and Richard N. Weeks as they helped lead the project together in their own ways. “I call Rich S. the rainmaker,” Kelley said. “He had the personality, the savior faire, and knew how to make this happen. And you had Dick there [Richard N.]; he’s a legend in the industry. He was always in the background watching everything, and nothing got by him. So Rich was out there in front, but Dick was back there watching.”

The project required Weeks to drive 96 pipe piles that were 4 feet in diameter and up to 140 feet in length so the piles could handle a final capacity

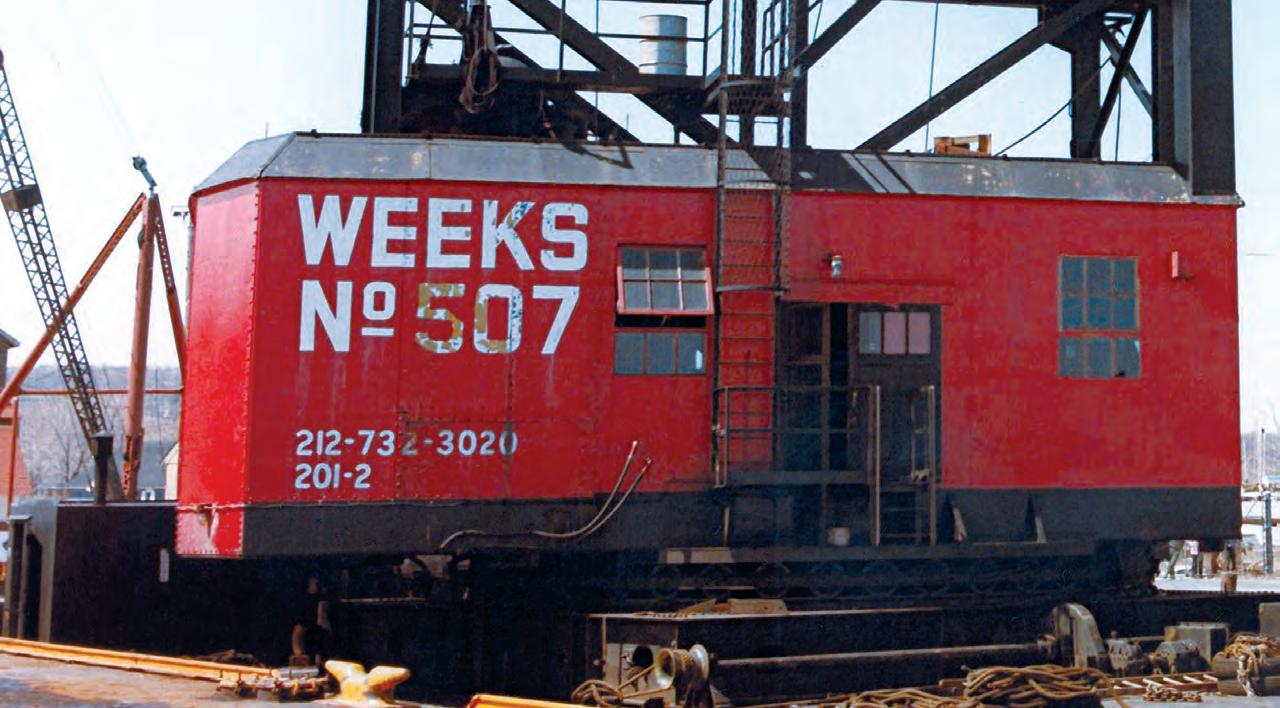

Weeks 533 placing precast concrete for the Tappan Zee fendering system .

1999

The United States Army Corps of Engineers creates a list of historically significant vessels to potentially salvage from New York Harbor.

1999

Weeks completes a construction job in Peñuelas, Puerto Rico, requiring the company to handle the civil marine portion of creating a liquid natural gas import facility.

2000

Weeks completes its project on the Tappan Zee Bridge.

2000

After years of being plagued by contamination, New York Harbor is cleaned up and a resurgence of wildlife appears.

of 500 to 750 tons. The company outfitted its Weeks 533 barge-mounted floating crane with a short boom so it could set the precast units below the bridge’s envelope. Closures were poured after the precast was in place, and then Weeks installed watertight cofferdams surrounding the post-tensioning ducts. The firm had to install a miniature batch plant on the barge to grout the tendons. After all of the tension work was completed, the firm put in ladders, handrails, and stairs on the outside of the fenders, completing the project in early January 2000.

High-Level Projects

Weeks installing a jacket, piles, and deck as the substructure for a future production platform and well casing in the Gulf of Mexico . As word grew throughout the industry of Weeks’ capabilities and its reputation for stellar, on-time work, the calls came rolling in with requests for bids on large projects. During the early part of the 1990s, Weeks was contracted to work on several major undertakings that spanned from its New York metropolitan area home base to new geographic areas. In one such venture, the company was tasked with installing a 200-ton jacket and 225-ton deck in 58 feet of water in the Gulf of Mexico, which reinjected seawater into the reservoir to restimulate the field for oil production.

The project, completed in early 1993, required Weeks to use its Weeks 532, which was a 350-ton-capacity derrick crane, as well as the Weeks 297, a deck barge. The company installed piles that spanned 30 inches in diameter and an impressive 250 feet in length. The 45-man crew lived on the Weeks 532 during the length of the project, which was mounted on a 300-foot by 90-foot by 19-foot hull.

A CHANGE IN LEADERSHIP

When Richard S . Weeks was named president of Weeks Marine in 1999, it was a natural progression of a long career in the company and was supported by the many employees that Weeks had at the time . “I think what I saw, and I still see, is Rich understood the advantages of leveraging the company’s assets toward future growth,” said Dave Vosseller, area manager for Weeks Marine, who started at the company in 1986 . “Now, he has the assets, the equipment, and so forth—and he asks, ‘What do we need to do to put those assets out to work to generate revenue so that we can go and acquire more assets and grow the business?’ That was what he was all about . ”

As Richard S . proceeded in his leadership as CEO, his belief in good stewardship by using all of the resources available to get the jobs done successfully— and then build on those successes through acquisitions—became central to the company’s vision in terms of how it would best achieve healthy growth .

International Expansion

The 1990s didn’t just mark a change in Weeks’ domestic construction operations, it was also a time of expansion internationally. As the advent of the Internet made the world increasingly more connected, Weeks began procuring more contracts that were further afield from its New York home base. In one such project, Weeks transported and installed a 900-ton gas compression platform in Trinidad’s Gulf of Paria in 1993, marking one of its first major international projects. “It was an offshore revitalization of an existing oil field, so we built two offshore platforms, and this wasn’t in deep water,” said Mike Stufflebeme, senior estimator, who started at Weeks in 1991. “It was 30, 40 feet of water in the Gulf of Paria, so we put in a platform that reinjected seawater back down into the reservoir and another one that compressed gas and injected it back into the

Weeks built a bulk materials facility to export petroleum, coke, and sulfur for Petrozuata VEHOP in Venezuela.

WEATHER’S IMPACT ON WEEKS’ WORK

When a company’s work involves so much time in the outdoors, it is absolutely imperative to prepare for all types of weather, as Tim Weckwerth, vice president of Weeks’ dredging division, explained:

There are two things you can’t control: the weather and how the project goes. Anytime you’re working in the marine environment, you run the risk of anything related to having a marine catastrophe, whether that be a sinking equipment failure that puts you up on the beach, ingesting some type of unexploded ordnance, or having an explosion in the pump system. There’s a lot of inherent risk, particularly when you’re working out on the water.

The best way to mitigate weather-related issues is to “plan for them and ensure that equipment is maintained properly and is always ready for all conditions,” Weckwerth said . “In addition, doing as much pre-work as possible indoors before heading out into the bad weather is vital .

The B.E. Lindholm coming into Cape Fear dock.

reservoir. And it was to re-stimulate the field for oil production.” The $55 million project was completed in 1993 for Weeks’ client, Trinmar Limited.

The international contracts kept coming, and in 1995, Weeks started working on a project in Barbados that required the firm to fabricate and install a 1,400-meter, 26-inch-diameter ocean outfall pipeline that had an end diffuser section. The pipeline was to be cement lined and concrete weight coated to ensure

durability in the ocean setting. To complete the near shore part of the pipeline, Weeks had to install a sheet pile cofferdam and an access causeway from the shore to allow for excavation of a trench and installation of the pipeline in the surf area.

Making the project even more challenging, Weeks also had to excavate through limestone rock that ran 10 feet deep to create the trench. The company used an extra heavy-duty clamshell bucket and a barge-mounted Manitowoc 4600 excavator to handle that portion of the project. Weeks laid the pipeline in 160-foot sections using the Weeks 540, and then divers went underwater to join together the flanged connections and diffusers, despite depths of 120 feet. Finished in just 12 months, Weeks created a stellar pipeline for its client, the Barbados Ministry of Health.

In 1999, Weeks completed a construction job in Peñuelas, Puerto Rico. The project required the company to handle the civil marine portion of creating a liquid natural gas import facility to supply a plant and berth station to LNG ships. Weeks completed the first 600 feet of a 1,750-foot-long by 30-foot-wide access trestle using an over-the-top technique due to the area’s environmentally sensitive nature. To create the trestle and dock superstructure, the company utilized as many precast concrete elements as possible, all of which were fabricated on the East Coast and brought by barge to the jobsite using Week’s fleet of ocean-ready barges and tugboats. The Weeks 526 handled much of the heavy lifting, since that particular derrick barge had a 350-ton capability.

By the late 1990s, Weeks was performing 20 percent of its work outside of the continental United States.

Above: Weeks employees setting up the framework for a bridge project in 1990 .

Below: Weeks at work at the LNG facility in Peñuelas, Puerto Rico .

GROWTH OF WEEKS’ TUGBOAT FLEET

Weeks Marine may have started out in the stevedoring business, but as the company expanded to include such equipment as barges and dump scows, it was obvious that the firm would need a way to get heavy equipment from one spot to another . Enter a fleet of tugboats that could not only tow Weeks’ equipment but could also be in service to other businesses that required items to be towed across waterways .

After purchasing its first tug, Weeks slowly built out its fleet, which now includes 14 vessels . Today, the company’s tugs are capable of international journeys, with towing capacity ranging up to 4,000 horsepower . Weeks’ tugs can tow everything from dead ships to tunnels to transformers and beyond, and they are all staffed with captains licensed by the United States Coast Guard . The crews also include skilled deckhands, engineers, and other seamen who can keep the tugs operating for months at a time, which is sometimes how long it takes to get a job done, said Towing Division Manager Ben Peterson .

Not only does Weeks purchase new tugs when necessary, but the firm is also dedicated to upgrading and maintaining its existing equipment whenever possible . In the mid-2000s, Weeks launched a repowering initiative during which about 80 percent of its tugboats were repowered to make them more powerful and efficient . “When it came to yanking the engines, removing the engines, and installing new engines, we did some of that in the yard with our yard personnel, physically, the removal and the installation,” said Joe Patella, general manager of yards and equipment . Thereafter, fine-tuning was performed and the tugs were put back into the rotation for the company’s needs .

The repowering initiative resulted in a state-of-theart fleet that is always busy on waterways all over the world . With tugs ranging in length from 56 feet to 126 feet, Weeks can handle both small and large jobs . “The work that we do is very eclectic, and there’s something new all the time,” Peterson said .

Moving Into the New Millennium

Weeks moved into the new millennium with the strength of fresh equipment and experienced employees. These key factors bolstered the firm as it forged additional contracts worldwide. As the company was enjoying its growth internationally, Weeks’ attention was about to shift dramatically. No one could have predicted what would be waiting for the company right near its home base in New York—a tragedy that would reshape the firm, and its employees, for decades, for life.

Above: The Shelby, one of the many vessels in Weeks’ tugboat fleet .

Opposite: Repairs to Weeks equipment can take place in the shipyard or out on the water—wherever maintenance is needed, Weeks employees will do it .