WORMFARM INSTITUTE INVITES YOU TO…

Words and images along a creative continuum

2023 Looking back and forward

2073 In the imagined moment

And various misfits, out of time

COVER QR CODE ACCESS INSTRUCTIONS

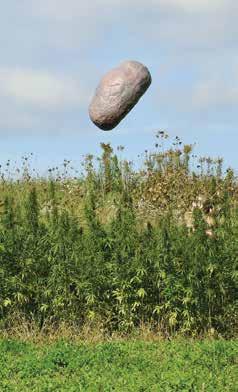

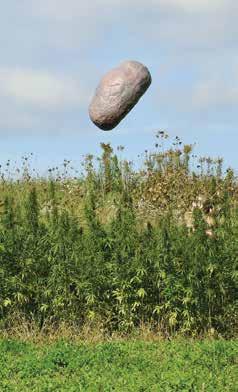

Scan the QR code to watch the augmented reality extension of the cover! Take out your phone and open your camera app. Hover over the QR code

“root ball” like you’re about to take a photo of it, and open the link that appears. Click the LAUNCH button. Point your phone at the cover image again, turn up your volume, and experience the future of farming.

Cover artist Austen Camille is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, builder and naturalist who works to forge connections between the arts and other disciplines.

2 wormfarminstitute.org

FuTurE TEnsE

Look here. What do you think this place will look like in fifty more years? What forces will be brought to bear? What of our lives will we bring to its shared story? What gifts can we offer?

Maybe spirits keep you up at night wrestling with such questions. Maybe you hear the voices of ancestors speaking of their lives and traumas, their demons and dreams. Or maybe future generations whisper to you, asking how you will shape their world.

Do the spirits of the land—of the skies and the rocks, the soils and waters, the animals and plants—also ask for your attention and appreciation? Do they make you anxious, restless? Or do they come with comfort, with assurances that they shall abide with you, with us, as we find our way forward?

Here’s the deal. The hard work of visioning an honest future requires all hands and hearts on deck, all aboard the ark, all into our kayaks and canoes, to be in the full flow of time.

In these pages we have invited friends and colleagues to conjure spirits, to channel them, to invite them to intervene. That is what art—a poem, a story, an idea, an image, a recipe, a garden, a performance, a formula— does. That is art’s job: to act on and in the world, to make a little wave in the space-time continuum, to create ripples, change us, change our reality, help shape a different future. To alter the universe, that’s all!

Hear their words amid the swirl. Disturbance, emergence, enchant, imagine, gather, diversify. Bridges, seeds, nutrients. Generations, lost, replenish, agrarian, manifesto. Futuristic flours. Futuritual fates. Farms in crisis, children at play in water, vegetables in the hand, milk in the culture. That’s the spirit! Do you hear it?

These darn spirits…they just won’t keep to themselves. They insist on mingling and dancing, making things up impromptu, alighting on the unsuspecting, doing magic in the corn, digging around and dwelling in the mucky soils of Honey Creek.

by Curt Meine

by Curt Meine

We hold the spirits dear, whether we want to or not. They are our guides and confidantes, nags and mentors. They are our best friends, the ones who tell us the truths no one else can and that we need to hear. They insist on walking us through all our fears and all our enthusiasms, talking us into the future unfolding.

. You’re invited, you’re next. What spirits call to you? What will this land look like in fifty years? What interventions will you create? What will you ferment and foment?

A meme of the moment—a fleeting digital spirit!—speaks: “When people travel to the past, they worry about radically changing the present by doing something small. But people don’t think about radically changing the future by doing something small in the present.”

Well, ok… but sure we do. We might not admit it, even to ourselves, but we think about it all the time, every time we plant and write and hug and sculpt and vote.

René Dubos—the late visionary soil ecologist and microbiologist—once wrote, “Wherever human beings are concerned, trend is not destiny.” It’s a hopeful truth to hold close in our disorienting times, facing our disruptive future. We have whipped up some doozies that may well defy our best efforts and overwhelm us. If we do the calculations, read the news, feel the heat, it becomes easy to fall into lethargy instead of agency.

Spirits too can do the math, and they have. But they still speak to us for no good reason. That’s the benefit of dwelling forever in other dimensions. Hello, this is your still silent voice calling. Hey, you are not alone! What do you see? What do you think? Tell me a story. Make me laugh. Cry. Wow…let’s celebrate!

Here and now, they swear: All your days are numbered, but all your nights can rhyme.

Curt is a conservation biologist, environmental historian, and writer. He is a senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation and the Center for Humans and Nature

Hope, healing, commitment, and change are in the skies all around us.

A Live Culture Convergence 3

—Ada Deer (August 7, 1935—August 15, 2023)

ConTribuTors

Adunate Word & Design

Ana Fernandez Miranda Texidor*

Angela Woodward

Angus Mossman

Austen Camille

Cricket Design Works

Curt Meine

Donna Neuwirth (aka Yetta Irving)

Erin Schneider

Gary Paul Nabhan

Jacque & Dan Enge

Jane Hawley Stevens

Jay Salinas (aka Jota Bellows)

Katie Schofield

Keefe Keeley

Kristin Plucar

Laura Mortimore

Laura Neal

Lexi Ames

Madigan Burke

Martina “Mars” Patterson

Max Sorenson

Mercedes Falk with support from Gloria Alatorre

Michael Bell

Nandita Baxi-Sheth*

Odessa Piper

Patricia Tinajero*

Paul Dietmann

Pete Hodapp

Philip Hasheider

Philip Matthews

Rob Nelson

Samantha Jones*

Sarah Lloyd

Tanya Carney

Wilda Nilsestuen with support from Bill Berry

*Collectively known as the Plant Contingent, these artists explore alternative ways of being through research guided by plant ontology. Their practices are entangled with the tradition of the spiritualist seance and the wisdom of Andean and Amazonian yachags and vegetalistas from South America.

4 wormfarminstitute.org

"Adapt or Die," by Chris Lutter, 2020 Farm/Art DTour

A CAsE For r EvErY:

DAYD rEAming mulTispE CiEs FuTurEs

by Nandita Baxi-Sheth

Revery1: an essential act and invitation for humans to engage with the inner lives of other than human entities, such as plants and insects. The method of interspecies entanglement suggested is revery, a daydream, a speculation. Etymologically, the word’s origins range from root meanings of absurdity and incoherence to the contemporary meaning of reflective thought.2 Amalgamating those various origins, let us think of revelry

as meditation tinged with wildness. Revery is cinematic imagination, painting images in our minds before thoughts are translated into words. Being lost in a daydream is an embodied sensation that nudges our human senses beyond their limits to explore other than human sensorial worlds.

In response to paralyzing daily news, revery could be one productive, generative, and fecund response to climate anxiety. If bees are few, the revery alone will do. From the broad horizons of midwestern landscapes, revery floats to isolate upon the interaction of one clover and one bee. By following the relationships of plants and insects, we might enter reveries of all sorts. Watch a bumble bee gloriously tumble into a

silken soft cup of petals and joyously gather grains of golden pollen. The plant and bee transform each other through the activity of pollination. The plant dreams of flowers, fruits, seeds, soil, of becoming multiple. We could also wonder, what does a bee dream of? If bees are few, the revery alone will do. Dickinson reminds us that the activity of daydreaming is essential to making the prairie. In addition to understanding the biological interactions of plants, insects, and humans, engaged in various stages of becoming, she asks us to include the magic of daydreaming. Revery is a creative site for sparking the transformation of dreams into action. This reading of the poem offers a response to planetary crisis. It is a spell for dreaming multispecies futures.

A Live Culture Convergence 5

Art by Patricia Tinajero

…let us think of revelry as meditation tinged with wildness.

1 I retain Emily Dickison’s spelling of “revery” here rather than the contemporary usage of “reverie” intentionally to pay homage to the source poem. 2 "reverie, n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2023, www.oed.com/view/Entry/164771. Accessed 5 July 2023.

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee, One clover, and a bee. And revery. The revery alone will do, If bees are few.

—1775 Emily Dickinson

FArmEr To FArmEr

by Laura Mortimore

purple eggplant spin around on the brush washer. She now declares she wants to be a farmer like her Aunt Laura. How about my new apprentice that I am currently training in all the various aspects of vegetable farm management including patting the crop–as they begin their farming journey. I am hoping that in 50 years all of these people have created farms, or taken over mine, and will leave a stool for me in the shed next to the scale where I can divvy out the cherry tomatoes for the week’s CSA delivery.

There is something we farmers hold inside us and pass on to the people around us, pass onto the next

generation of farmers and the community of eaters we feed. It’s the magic of a bulbing onion and a blushing tomato. The wonder of a plumping sweet potato beneath the soil and a cucumber springing forth from its flower. My Grandpa Harry passed on the magic to me through my father certainly, and I will do my darndest to keep the chain going to new farmers and new eaters here in Sauk County and beyond. I’ll pat every squash in the field if I have to.

6 wormfarminstitute.org

Laura is the owner of Orange Cat Community Farm, a certified organic, community supported agriculture, vegetable farm.

RYE & BERRY BROWNIES

A dense, crackly, chewy drop brownie. Recipe adapted with permission from ellejayathome.com/rye-brownie-cookies/

Ingredients●

2 large eggs, room temperature

●1 cup pure cane sugar

●½ cup local unsalted butter

●½ cup semi-sweet chocolate chips

●1 tsp vanilla extract

●1 tsp espresso powder (optional)

●¾ cup whole rye flour (I recommend Meadowlark Organics)

●¼ cup dry aronia berry powder (or blueberry, black currant, acai)

" If you cannot find powdered berries, use ¼ cup cocoa and the larger amount of frozen fruit listed below

●½ tsp sea salt

●¼-½ cup frozen berries such as blueberry, aronia, blackberry, mixed with a little black currant

●Rolled rye flakes (optional)

Instructions

1. In a large bowl, using a hand and stand mixer, whip the eggs and sugar until the eggs are nearly tripled in volume, very pale.

2. Melt together your butter and chocolate chips. Stir in vanilla.

3. When eggs are at ribbon stage, whisk in a third of the butter and chocolate to temper the eggs, followed by the remaining two thirds.

4. Turn off the mixer and sift in rye flour, Aronia berry powder, and salt. Gently fold to combine.

5. Cover, and chill your dough for 1 hour.

6. Portion dough into evenly sized balls, one heaping Tablespoon each. Freeze some of the pre-portioned dough for a quick, easy treat when your sweet tooth summons.

Preheat the oven to 350ºF. Line your baking sheet with a silicone mat or parchment paper.

Place balls onto the sheet with 2 inches of space between each one. (If baking from frozen, defrost for 10 minutes). Sprinkle with a couple grains of sea salt. Optional: press rolled rye flakes on top. Bake for 10-12 minutes.

Odessa is a chef and the founder of L'Etoile in Madison, and the author of "The Market Kitchen," a small cookbook of seasonal recipes for the home cook.

r E CipE For ThE FuTurE

by Odessa Piper

I’m very fond of the fruits of the perennial stalwarts of North America. I collect the berries of adapted cultivars from blueberries, aronia, currants, and brambles, along with hickories and walnuts. I keep them in my freezer like precious gems and bring them out every season of the year.

I like to think our future foods will blend more of these soil- and climate-friendly cultivars with newer arrivals like crabapple, helping to keep balance and old land traditions alive. I envision a return to placebased eating with the rise of perennial foods. More and more farmers are replacing their corn and soybean rotations with perennial natives that decelerate the food chain: hazel, hickory nuts, elder and shad, chokeberry and currants.

My friends at the Savanna Institute work with farmers to support such shifts and transitions. Through their community of growers, I have begun experimenting with preserved forms of future-friendly foods. This recipe calls for pumice from regional berries after they have been juiced, with a ton of flavor and nutrition in the skins.

My recipe is so futuristic that these dried pumices in powder form are not yet on the market, but they will be as the agricultural landscape continues to change! Meanwhile these brownies are delicious with all kinds of berries from the freezer.

A Live Culture Convergence 7

AgrAriAn prophETs

by Gary Paul Nabhan

Agrarian storytelling? Agrarian poetry? Agrarian prophesies? Agrarian urgencies? One might wonder whether any 21st century preoccupation with agrarian values and agrarian ideals comes as too little, too late, for less than one in six of all Canadian and U.S. citizens live in rural areas outside of towns, cities and suburbs.

But listen up. Look again. The New Agrarianism is emerging and it is not restricted to the rural domain. Nor does it necessarily stem from some romantic desire to re-enact the social behaviors and mores associated with rural populaces of by-gone eras. Instead, this New Agrarianism is emerging within urban as well as rural communities, among young and old. It may indeed be the set of values and operating principles which can obliterate the rural-urban divide which both characterized and crippled North American cultures during the second half of the Twentieth century.

But what exactly does agrarian mean, and why are the concepts associated with it being used once more as rallying cries, decades after most North Americans have become disenfranchised from the land and a half century after most agrarian populism blew away with the winds of change?

We can begin to glean answers by exploring the many roles that agrarian poetry plays in our society today,

through its many forms: cowhand recitations, new Western songwriting, sheepherder’s ballads, farmers’ prayers and even prosepoems, graffiti and cowboy jazz. Many of these spoken artforms are meant to entertain and humor us, but others can make us howl, weep, or well up with wonder, anger, or remorse.

But that is not all. Agrarian literatures help us remember enduring rural values, skills, and expressions that may still help guide our relationships with changing landscapes rather than being dismissed as obsolete. They can help us re-story and thereby restore the land itself with elements continuous with the past that deserve to be held dear in the present moment. With less than two percent of all citizens of North America identifying themselves as farmers or ranchers, the poetry which keeps these values, skills, and expressions alive is needed now more than ever before in American history.

Why? North Americans have recently suffered the greatest loss in traditional knowledge relating to food production and land management than has occurred in any place or time in human history, but we hardly recognize that fact. With climate change advancing, water and food security may eventually trump every

8

wormfarminstitute.org

Agrarianism…is no small, whittled-down philosophy for rural folks. It is, rather, a full-blown philosophy rooted in the realities of soil and nature as ‘the standard’ by which we also come to judge more. It is grounded in farming, but is larger still. The logic of agrarianism… unfolds like a fractal through the divisions and incoherence of the modern world.

—David Orr, on new agrarianism

They can help us re-story and thereby restore the land itself with elements continuous with the past that deserve to be held dear in the present moment.

other issue facing us in the West. As Margaret Atwood pointedly quipped about the coming climatic changes in 2010, “Go three days without water and you don’t have any human right. Why? Because you’re dead.”

And so, there is one function of the agrarian poetic tradition that may be known well among its practitioners but remains little discussed among society at large: its visionary or prophetic function. More than ever, diverse agrarian voices need to be heard for what they are telling us about how to live—or not to live—in the future. Without being polemical, poetry can expose the damage that has been done to our watersheds and foodsheds, and therefore to our communities and our bodies whenever we get these relationships out of sync.

Using sensuous imagery and compelling narrative rather than a reliance on didactic rhetoric, agrarian poets remind us through visual images, sounds, fragrances, and flavors what we may be at risk of losing, and what we need to tenaciously keep dear. While some dwell on what damage segments of humankind have wrought upon us all, others focus on how one responds to the ways nature itself is changing, with or without human prompting. Consider Linda Hasselstrom’s “Drought Year” with its sense of foreboding:

I dreamed I slept alone in a drought year, and now I do.

I lie in the short grass; water is a dream. All day I was fuel for the sun burning like wildfire over a dry land…

I dream you died in a drought year, and you did…

I dreamed myself a dry woman and I am, the juice gone out of me. My skin is fragrant with prairie odors. I am drying grass, wind-bent. Long tough roots grapple deep into the baked prairie earth.

Leaves die, but roots dream in crumbled sod, wait for rain.

I would argue that the images, ideas, and values of our best agrarian poets are our culture’s antibodies that will potentially protect us from a host of diseases in the future, and that dismissing the preoccupations of agrarian poetry as things of the past is both problematic and perilous. Agrarian poets have arisen in many societies whenever estrangement from the land, driven by political, economic, or military forces threatens to undermine the very core of our existence. Listen to theologian Ellen Davis (2009) who has argued that agrarian poetry and prophesy have historically played

essential roles in righting the course of cultures gone astray:

"…If the message of new agrarian writers may be rightly called ‘prophetic,’ the more important fact is less widely recognized: The message of the earliest prophetic writer in the Bible was distinctly ‘agrarian.’ The eighth-century prophets Amos and Hosea were probably the world’s first agrarian writers…This sudden outburst of rural prophesy, apparently unprecedented in the depth and range of its vision and replete with language and images that evoke the experience of farmers, seems to have been prompted by a large scale transformation of both the land and the rural economy."

In weaving such images into agrarian prophesies, Western poets and poet-farmers somehow transform the bitterness of life on this earth at this moment into something sweet and redemptive. We become, as Rilke put it, “…the bees of the invisible. With total absorption, we gather the nectar of the visible into the great golden honeycomb of the invisible.”

Gary is an agricultural ecologist, ethnobotanist, and author of "Agave Spirits: The Past, Present, and Future of Mezcals." He is considered a pioneer in the local food and heirloom seed saving movements.

Sixty years ago, in 2013, Savanna Institute took root. Like the trees we steward, each year we have strived to grow in depth and abundance, honoring the vision of perennial agriculture that connects us to our past and guides us into the future. Learn more at savannainstitute.org

A Live Culture Convergence 9

Yetta Irving, USDA Under Secretary for Rural Development

400 Independence Ave

Washington DC 20227

July 18, 2073

Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO)

Dear Colleagues,

Today marks the 10th anniversary of the Agri/Cultural Holistic Realignment Act (AHRA) of 2063. After years of often challenging but ultimately productive work across the aisle, Congress passed the 2070 Farm, Food and Climate Bill that supports the goals of AHRA. As a result, we are pleased to roll out a new grant program.

The Funding Opportunity Title (FOT) selected from among suggestions submitted throughout the Department is: Festivals and Rituals for Fertility and Abundance (FRFA). The Agency estimates $620 million will be available for FY2075.

This new program responds to the mandate for increased cooperation among federal agencies to “stack functions” for long-term social, economic, environmental, cultural, and nutritional outcomes. It builds on a recent public/private initiative studied closely by the USDA in collaboration with the National Endowments for the Arts, the Humanities, and Soil Health (NEA, NEH, and NESH) (see xyz 1234b) that has demonstrated the power of the arts, broadly defined as an essential nutrient.

Rites, rituals, and seasonal festivals that include art, literature, music, dance, and theater, often performed in farm fields, have been central to agrarian civilizations for thousands of years [Trilogie altindischer Mächte und Feste der Vegetation (Zurich, 1937)]. These events were all but lost in the U.S. in the early 21st century. Along with the cross-sector health benefits that the alignment addresses, AHRA elevates the deep cultural significance of farming as a profession, and acknowledges the critical role that artists play in the agricultural cycle through reverie, by enacting seasonal rituals around planting, growing, and the harvest.

The benefits, though challenging to quantify, have been difficult to ignore since AHRA was adopted. The bipartisan realignment has arguably been the most successful government response to the effects of Climate Change to date, due in large part to its cross-sector approach that is popular in both urban and rural communities (see study ifzx400-Q).

Please expect the formal FOT release in 30-60 days, and send all questions and comments to Bot 483-f. Note: there will be additional discretionary funds available to Rural Development Offices in all 54 states and tribal governments, targeted toward applicants who actively partner with arts and cultural organizations. Though technically this program is run through the Rural Development Office, applicants from urban areas are encouraged to apply.

Sincerely,

Yetta Irving, USDA Under Secretary for Rural Development

10 wormfarminstitute.org

This notice uses the archaic medium of “letters printed on paper” as a consideration to those who reside in technology deserts and to accommodate those Centenarians who have opted out of installing the NeuraLink™ to receive notice of the following programs.

groundwater. Now, it is illogical and criminal to drain a wetland and replace it with ditches and drain tile just to grow a monocrop. We observe how it functions, and figure out how we can improve its functionality to humans while also improving its ecosystem services to benefit biodiversity.

Now that we've used up the fertility of soils produced by thousands of years of bison, elk, and pronghorn grazing on the prairies and savannas

water-holding capacity. Goats and sheep browse on the woody shrubs. Turkeys and chickens peck and scratch after the larger animals have moved through—eating parasites and integrating their manure. Even with the lack of wild megafauna, it's obvious that wild diversity is improving. Fireflies light up the night. The crickets, cicadas, locusts, and frogs are so loud, it's hard to have a conversation with someone three feet away. The sky is filled with too many

cides while feeding the individual trees synthetic nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Now, fruit and nut orchards aren't orchards at all. They're living forest ecosystems. Sprays and fertilizers aren't needed; all that is needed is to harvest delicious, nutritious food. To the wild woodland dwellers, humans are a welcome keystone species in managing the forests in which they live.

Jacque and Dan are co-founders of the Veggie Emporium. They provide nutrient-rich produce to their community while promoting biodiversity and soil regeneration.

A Live Culture Convergence 11

It's a system that can see, hear, feel, and communicate.

miCroForEsT mAniFEsTo

by Sam Jones

We seek the atoposes—places out-of-place.1 The abject voids left unseen by the eyes of the City–underpasses, trash heaps, abandoned lots, sidewalk cracks—these call to us to fill them with abundance. We bring our infestation into the rational worlds that have put material to sleep. Wake up! Remember you are still alive! We bring the monsters of the forest, the sticky, dirty mess of vines and roots and needles and sap. We invite insects to gnaw on your steel, worms to unshackle your polymers, and lichen to infiltrate your homogeny. We embrace alterity as lovers, our fascination driven by a thousand voices in every drop of being. There is nothing pure and nothing to remember—only the persistence of being, in our love and pain.

Oh City, your hubris has emblazoned after-images into your retinas. Now you live in an apocalyptic mirage of your own design. We beg you to close your eyes and embrace the coolness of our elongating shadows, to smell the essences emanating from our understory, to taste the clear dew dripping from our stomata. We have claimed your blurry edges

when you weren’t paying attention, and now we shall save you, despite yourselves. Even now, we infiltrate the atmosphere, bringing the breath of life to your worn out, emaciated body. And you know that you must die to yourself to join us, but what looks

like death is only the emancipation of being. Let go of your images, become the chimera, feel the pulse of life! Our seeds await germination in your crevices, our spores have landed in your nostrils. Breathe us in, and come out to be with us!

12 wormfarminstitute.org

1 Atopos means “unusual” or “out of place.” In his essay “Poetry of Worthlessness, Worthless Places or Atoposes,” Mattias Forshage makes the case for atoposes—the useless places in the urban environments which are the most potent for change.

Art by Ana Fernandez Miranda Texidor

U.S. Department of Meaningful Rituals (USDMR) Department Memo from Jota Bellows, Director of Middle Region

October 2, 2073

Related to the recent USDA announcement of FOT-FRFA, proposals are now being solicited for the Division of Seasonal Celebrations for FY75 in the Mississippi–Wisconsin Rivers Cultureshed (MWRC). Per guidelines, proposed projects must include activities in at least three meat space venues. They must give thanks to the biotic community, celebrate harvest season, and special consideration will be given to those who utilize novel death and resurrection metaphors. Collaborators must represent a broad swath of the region’s Compañeros, and programming must seek to bewilder and enchant at least 25% of participants respectively (as revealed through NeuraLink™ data). Successful funded celebrations will be considered for subsequent deployment in the Scorched and Scoured Zones (SSZ) as they are gradually reclassified as Potentially Habitable Zones (PHZ).

As has been the practice since the adoption of the 2070 Farm, Food and Climate Bill, cultural workers are invited to design and implement festivals throughout the bioregion in support of the seasonal Urban Rural Flow pilgrimages that focus on and elevate the planting, tending, and harvest of the region’s remaining annual crops. With the decreasing reliance on annuals, the FLOW pilgrimage has become less about actual labor and more of a ritual of respect for those highly valued, shared activities that demonstrate a marked increase in the physical and mental health of the bioregion’s Compañeros. Celebratory in nature, the pilgrimage honors the competitive positions on the few remaining human Soil Tender crews. Currently, many bands of unauthorized Soil Tenders are beginning to appear, requiring the Farmers Union to begin screening credentials.

Rapid voluntary world-wide decarbonization, along with widespread adoption of silviculture practices during the Climate Turmoil of 2025-42, has allowed for the establishment of the Bioregional Redoubt System (BRS) resulting in large swaths of the Upper Midwest remaining habitable for diverse species. We are recalibrating and cautiously reentering the SSZ to the south and west which are healing at a remarkable pace, once aggravating factors are curtailed, again revealing the self-regulating harmony of Gaia.

Spring Fertility Rituals: The Championship Cultivator competition now has a threeyear waiting list and it is widely felt that the expanded 64-team bracket in last year’s Midseason Madness was still too restrictive. The Final Four Cultivator teams with drummers were deployed south, to the region near the headwaters of the Rock River to see if the Reed Canarygrass Curtain could be penetrated. While some progress is reported from three of the teams—including the discovery of a grove of remnant paw paw trees, thought to be extinct—the fourth team has gone missing, presumed to be victims of Murder Hornets which have reportedly established a presence in the area.

Finally, a reminder that securing reservations on the MWRC monorail has become easier since hydrogen-powered jetpacks became widely available. Please secure your visa to the Ho-Chunk Homelands before departing Wisconsin River Crossing; failure to do so will result in penalty.

A Live Culture Convergence 13

Ghost writers Donna Neuwirth and Jay Salinas are the co-founders of Wormfarm Institute.

losT

by Sarah Lloyd

Iused to scan the ditches along the roads between the Gillingham cheese factory and the Schmitt cheese warehouse, thinking about that lost cheddar cheese. Both businesses are long shuttered—now a cabinetry business in Gillingham and I think an insurance office in the Schmitt cheese warehouse. What was the story with the lost cheese? I’d imagine it rolling off the back of the truck, a driver that hadn’t quite managed to get the door latched. Or maybe it was something more exciting, like some late-night cheese rustling back in 1948. Perhaps a systematic loss of wheels or barrels of cheddar that Harlan Watt, the cheesemaker at Gillingham, finally had had enough of, placing a classified ad in the paper to get people’s attention.

Despite asking around about this lost cheese in Richland County, Wisconsin, I never did solve the mystery. I talked to a man whose family had delivered milk from their small dairy farm to the Gillingham cheese factory back in the 1940s. When Gillingham stopped processing cheese they started shipping their milk to a different, larger plant. What he remembered

was, “I liked shipping milk to the small cheese factory down the road better than to the big plant in town because in the small factory you could go in, have a piece of cheese, and chat.” He didn’t remember the lost cheese, but he remembered the lost cheese factory and the social connections created by that space of production.

A 1954 Wisconsin Crop and Livestock Reporting Service bulletin estimated the average distance between a farmer and the closest dairy processing plant in 1950 was just six miles for the seven-county area of southwest Wisconsin, including Crawford, Grant, Iowa, Lafayette, Richland, Sauk, and Vernon. It’s incredible to think about that density of farms and cheese processors. Milk and cheese flowing down the roads and apparently occasionally rolling out into

the ditch. What I find interesting and important in letting my mind wander with this classified ad, is to think about all that we have lost as we lose our dairy farms (over 300 a year in the last few years) and our cheese processors become fewer and fewer, larger and larger. The density of the fabric of social and economic interactions becomes threadbare. And it is this opportunity for some cheese and a chat that is lost. I met a former milk truck driver from the area and I asked him about how he remembered the systems back then:

“I drove a milk truck for many years right after high school. I think I picked up from 18 farms, all right in this area. I went every other day. Oh yes, I remember all the different families and you knew what was going on and you stopped and talked with them.”

The rhythms and systems of production—and the connections between farmers as ingredient suppliers, processors and folks who get the product down the road to the warehouses, and finally to rural and urban eaters—are critical to rural social life. They both form and are formed by these routes and flows. What has hollowed out our rural communities is the loss of both density and rhythm of these meaningful connections.

The good news is, there are lots of people working in many different ways to rediscover and reimagine the social and economic interactions around food and agricultural production, processing, distribution, and eating. And just think of the fun party we could have when we find that 75+ year-old cheddar from the Gillingham cheese factory! Let’s plan it—even if we don’t find that cheese. Our reward will be a good chat.

Sarah and her husband operate a dairy farm. She works off-farm as a food systems scientist for UW-Madison and a supply chain specialist for the University of Minnesota.

Zea mays (corn), 14 wormfarminstitute.org

April 15, 1948 Richland Center Republican Observer

wild (adj.) 1. living or growing in natural conditions. The road that raised me, mocked the shape of a snake. I threw my hands in the middle of it wishing for something to care for, the hot sun petting my back. And what difference does it make to watch the ditch grow thick with weeds? And how does this plain, abundant labor rattle me loose and wild inside? 2. in its natural state; not changed by people. The tall tree by the mailbox, will still be the tall tree by the mailbox fifty years from now. Yes, there will be storms. Yes, the ivy and spanish moss will belt itself to its bark and branches. Yes, the people will come wearing their saws and deadlines. Yes, the tree will stay. Yes, it looks more like a cross than a tree. Yes, the birds will flock in wild ministry. 3. having no discipline or control. The kudzu makes its own shadow on the ground, wild with surviving. I remember none of my dreams, only the myth of flying, the feel of the color green. I grow wide in the shape of a field, the field forgetting me with its relentless arrivals.

—Laura Neal

Laura is a poet greatly influenced by social and environmental narratives. She strives to exploit the "everyday," the parts of life that function like paper cuts, calling for our attention.

A Live Culture Convergence 15

"Baraboo," by Rosalynn Gingerich, 2022 Farm/Art DTour

16 wormfarminstitute.org

Kristin Plucar is an artist who creates layered and detailed drawings informed by nature, place, personal experience, and spirituality.

ThE DAirY sTATE

Wisconsin, the dairy state—a beautiful story we loved to tell. It was a story of family, honest work, relationality, and the sustenance we milked from our harmonious work. We cows loved it as much as you humans—the story at least, if not the reality.

And I guess we still are “the dairy state,” in a way. With the one remaining dairy in the U.S. now that Wisconsin’s other one closed last year, as did the last dairy in California. And we have the last remaining dairy cow too, now that I've been retired.

The graphs all pointed this way fifty years ago. Dairy farms were closing at a rate of a thousand a year, and the number of cows dropped a hundred thousand a year. The 6,000 dairy farms in 2023 and the 3.4 million dairy cows weren’t going to last long at that rate. The curves did flatten out somewhat, so California didn’t hit “dairy zero” and we didn’t hit “dairy one” until this year. But we’re here now.

They all blamed oat milk at first. Not me. Personally, I love oat milk. Toasty, sweet, and smooth. And low methane. But people still love cow’s milk, so we kept it pumping. “Pump up the volume. Pump up the volume.” I wanted to shake off my cluster and dance when they played that old song in the barn.

That was when I was still the source for the Southern Milk Pipeline. The Bossy Company hadn’t bought us out yet, though they already controlled the Eastern and the Western Milk Pipelines, and the Northern Milk Pipeline that feeds the Canadian market. My teats streamed 100 million pounds each

by Michael Bell

day, south for our Crazy Daisy brand. “The Holstein Queen of Southern Protein,” they used to call me. That’s done now, and I’m kind of OK with it. They’re finally letting me stand up and graze, though I’m confined to keeping my front hooves in Green County and my back hooves in Rock County.

It’s all down to Paula, the Red Cow with the Biggest Pow, the Pride of Fond du Lac. She’s four times bigger than even me. It’s a mile from the tip of her tail to the tip of her nose. Two hundred yards from tip to tip of her horns. They tried to poll her with a special 20-foot chain saw, but she wouldn’t let them. A few stamps of her hooves sent them running, and triggered an earthquake swarm that toppled the golden calf statue Cowconn had erected at the peak of its skyscraper in downtown Milwaukee. Paula’s udder would fill Camp Randall stadium, they say. Her teats are twenty yards long and five yards in diameter, and she produces 500 million pounds of milk a day from each one. Her belches have enough methane to heat the city of Chicago for a year.

Oh, and her manure. That was a huge controversy for Cowconn, once

the public got wind that the Bossy Company was their secret subsidiary. Speaking of reeking. Eventually they got the Legislature to agree to turn Lake Winnebago into Paula’s manure lagoon. Problem solved.

Then there were all those pipeline fights. People protested, but they were wasting their time. Now the four pipelines—North, South, East, and West—are each hooked up to a different one of Paula’s Bunyanscale teats. At her volume of milk, she can easily supply all four. They bulldoze the feed into her mouth as she lays there, covering half the county. They deliver the Bovine Growth Hormone by tanker car and inject it into her with a pile-driver. The manure decants into the lake. And the milk flows across the continent. What could be better?

But I hear rumors that Cowconn has figured out how to make cow’s milk in a factory. Cow’s milk without the cow! The dairy state without the dairy! Dairy zero here too. No manure, no methane. No need for corn or alfalfa. No need for sunshine. All powered by a fusion reactor.

That’s BS, if I may say. Paula and me, we need to organize. Need to shake out of these fetters and stomp up to Fond du Lac and get Paula back on her feet. Together, we can stampede Cowconn. We can flatten their tower. We can chew up their golden calf and turn it into cud. We can show them what stock really is—that it’s us, not something to be exchanged daily. Bring on the day of the living livestock, even if it’s our last. They can’t cow-con us!

Mike is a professor of community and environmental sociology at UW-Madison as well as a musician and composer.

A Live Culture Convergence 17

Illustration by Gary Cochrane

puEnTEs

by Mercedes Falk

Alot of us talk about our ancestors and where they came from, especially in our agricultural communities, where many farms have been in the same family for generations. Our kin before us or maybe even we have forged and crossed countless bridges to reach this land that we now call home. Even though these essential bridges helped us cross a barrier to get to where we are, it still takes time for each generation to put down roots and feel connected. As the director of Puentes/Bridges, an organization in Buffalo County, Wisconsin, that works to build bridges between the community that immigrates to work here and our rural and farming community, I have seen this personally. In the last couple of decades, as new immigrants have come from Latin America to work on our dairy farms, we have seen their employers have life changing experiences as they have gotten to know them on a deeper level.

On a recent trip to visit families in Mexico, we made our way up a dusty mountain road into the village of Las Palmas under the early afternoon sun and were greeted by more than 40 relatives of gentlemen who have worked on the same farm for years. After handshakes, hugs, and excitement, we were rushed over to the barbecue pit, where a lamb had been roasting since before the sun came up. Coals and hot ashes were taken off and heaped into a wheelbarrow until they got to the maguey leaves that were surrounding and tenderizing the meat. In a few short minutes, they were carrying plates of Barbacoa, the most famous dish in Hidalgo, to a table that had already been set with mole, homemade tortillas, three kinds of salsa, and a host of other traditional cuisines.

While we had the honor of sharing a meal with their favorite foods, we had an intimate conversation with one young mother. She shared some

18 wormfarminstitute.org

…as new immigrants have come from Latin America to work on our dairy farms, we have seen their employers have life changing experiences as they have gotten to know them on a deeper level.

of the challenges of being away from her husband as her youngest son sat on her lap and her oldest was close to her side with his hand set on her shoulder. As the tears dried, she told her husband’s employer that she knew it wouldn’t be forever and this separation, albeit challenging, was creating a better life for their family for the future. Afterwards, we got a tour of a half a dozen houses that were built by different relatives working on the same dairy farm. When we got to one piece of land, she proudly showed us the exact spot, next to a beautiful shade tree, where she and her husband plan to build their house.

Through traveling to their employees’ homelands and contemplating the journey they took to get here, farmers have developed a deeper understanding of their employees and their beliefs, drive, and culture. These connections have increased the appreciation farmers and their employees have for one another and helped them find ways to work together like family, despite often speaking two different languages. Just as our land was not meant to only grow one type of crop, we were not created to behave or think the same way about everything.

When I close my eyes and envision Wisconsin’s future, I see us building on and blending our eclectic cultures and traditions. I see shared spaces where people

b ri DgEs

tell stories about themselves or their parents or great-great-grandparents, and the reasons they moved to this land where the soil is rich and the opportunities seemed like a dream. I see a place where we understand we are all striving to create the best lives possible for ourselves and loved ones. Where people of different generations with roots from multiple regions in the world eat salads from the garden and tamales and burgers and Lefse on the same plate, as if that’s how we’ve always done it. We laugh about how we differ and truly listen to one another with an understanding ear. We take care of one another like family.

I see communities where we work to understand one another and accept our differences, where our beliefs and dreams may distinguish us, but do not separate us from one another. I see a mountain of possibilities when we don’t let anything stop us from forming powerful connections with one another and creating bridges where the passage once seemed impossible.

frittilary

Mercedes is the director of Puentes/Bridges. She enjoys learning about all forms of agriculture and has a deep appreciation for the diversity that makes up our world.

Escrito por Mercedes Falk, Traducido al Espanol por Gloria Alatorre

(English translation of Puentes)

Muchos de nosotros hablamos de nuestros antepasados y de dónde vinieron, especialmente en nuestras comunidades agrícolas, donde muchas granjas han estado en la misma familia durante generaciones. Nuestros parientes antes que nosotros o tal vez incluso mucho antes, hemos forjado y cruzado innumerables puentes para llegar a esta tierra que ahora llamamos hogar. A pesar de que estos puentes esenciales nos ayudaron a cruzar una barrera para llegar a donde estamos, todavía toma tiempo para que cada generación eche raíces y se sienta conectada. Como director de Puentes/Bridges, una organización en el condado de Buffalo, WI, que trabaja para construir puentes entre la comunidad que emigra para trabajar aquí y nuestra comunidad rural y agrícola, he visto esto personalmente. En las últimas dos décadas, a medida que los nuevos inmigrantes llegan de América Latina para trabajar en nuestras granjas lecheras, hemos visto a sus empleadores tener experiencias que cambian la vida a medida que los han llegado a conocer a un nivel más profundo.

En un viaje reciente para visitar a las familias en México, nos dirigimos a vereda de montaña que lleva hacia el

pueblo de Las Palmas bajo el sol de la tarde, el cual luego fuimos recibidos por más de 40 familiares de los hombres que han trabajado en la misma granja durante años. Después de apretones de manos, abrazos y emoción, nos llevaron hacia la fosa donde se hace la parrillada, ahí un cordero había estado asando desde antes de que saliera el sol. Las brasas y las cenizas calientes se retiraron y se amontonaron en una carretilla hasta que llegaron a las hojas de maguey que rodeaban y ablandaban la carne. En pocos minutos, los platos de Barbacoa empezaron a servirse, este siendo el platillo más famoso de Hidalgo. Estos fueron acomodados en una mesa que ya había sido colocada con mole, tortillas caseras, tres tipos de salsa y una serie de otras cocinas tradicionales.

Aunque tuvimos el honor de compartir una comida con sus comidas favoritas, tuvimos una conversación íntima con una joven madre. Ella compartió algunos de los desafíos de estar lejos de su esposo mientras su hijo menor se sentaba en su regazo y el mayor estaba cerca de su lado con la mano puesta en su hombro. Mientras las lágrimas se secaban, le dijo al empleador de su esposo que ella sabía que no sería para siempre y esta cont. pg. 20

A Live Culture Convergence 19

separación, aunque desafiante, estaba creando una vida mejor para su familia para el futuro. Después, recibimos un recorrido de media docena de casas que fueron construidas por diferentes parientes que trabajaban en la misma granja lechera. Cuando llegamos a un pedazo de tierra, ella nos mostró con orgullo el lugar exacto, junto a un hermoso árbol de sombra, donde ella y su esposo planean construir su casa.

Al viajar a las tierras natales de sus empleados y contemplar el viaje que han experimentado y recorrido para llegar aquí, los agricultores han desarrollado una comprensión más empática y profunda de sus empleados y sus creencias, motivaciones y aspectos culturales. Dadas circunstancias y experiencias han creado una unión entre ambos agricultores y empleados trabajando juntos como una familia a pesar de la diferencia de lenguajes. Al igual que nuestras tierras no fueron destinadas para sembrar y crecer un cierto tipo de cultivo, similarmente nosotros no fuimos creados para comportarnos y pensar exclusivamente de una sola manera.

Cuando cierro los ojos y visualizo el futuro de Wisconsin, nos veo construyendo y mezclando nuestras culturas y tradiciones eclécticas. Veo espacios

sí mismas o sus padres o tatarabuelos, y las razones por las que se mudaron a esta tierra donde el suelo es rico y fértil y las oportunidades parecían un sueño. Veo un lugar donde entendemos que todos nos esforzamos por crear las mejores vidas posibles para nosotros y nuestros seres queridos.Donde personas de diferentes generaciones con raíces de múltiples regiones del mundo comen ensaladas del jardín y tamales y hamburguesas y Lefse en el mismo plato, como si así fuera como siempre lo hemos hecho. Nos reímos de cómo diferimos y realmente nos escuchamos unos a otros con un oído comprensivo. Nos cuidamos unos a otros como familia.

Veo comunidades donde trabajamos para entendernos unos a otros y aceptar nuestras diferencias, donde nuestras creencias y sueños pueden distinguirnos, pero no separarnos unos de otros. Veo una montaña de posibilidades cuando no dejamos que nada nos impida formar conexiones poderosas entre nosotros y crear puentes donde el paso alguna vez parecía imposible.

Mercedes es la directora de Puentes/Bridges. Le encanta aprender acerca de todos los tipos de agricultura y aprecia profundamente la diversidad que compone nuestro mundo

20 wormfarminstitute.org

b

…a medida que los nuevos inmigrantes llegan de América Latina para trabajar en nuestras granjas lecheras, hemos visto a sus empleadores tener experiencias que cambian la vida a medida que los han llegado a conocer a un nivel más profundo.

"Field Notes," Farm/Art DTour. The Ho-Chunk word for Reedsburg translates to ‘the land of cemeteries.'

rEsTAurAnT rEviEw:

ThE sAnD bAr–ADDrEss: vArious–priCEs: sTEEp

by Angela Woodward

by Angela Woodward

It may seem like a waste of effort to set up a restaurant nightly only to have it vanish downstream by the end of the evening, but go ahead and book your table at chef Lydia Turner’s Sand Bar now. I can’t tell you what kind of experience you’ll have. On my first visit, I splashed across a stretch of the Wisconsin River and settled down at a sort of crate— all furniture had been made that day out of driftwood, antlers, carp skeletons, whatever washed up that morning. The lapping of the river accompanied the waiter’s recitation of the specials, though motorboats whizzing by, drunk boys screaming from the bow, drowned out the finer points. Chef Turner flipped walleye in what was nominally the kitchen of the restaurant—a fire in a pit,

curtain of steam from mussels hitting boiling water temporarily hid her, then the chef’s hands emerged from the vapor, passing plates to the waitstaff. The sun set. My feet were still soaked from the journey over. Sand grated between my toes while the stars shone down on my pea flower blue cocktail. I arrived home from this meal content and intact.

On another night, I crunched the skin of charred bass filet with great pleasure, only to find my glass of pear vodka tilted over, the perfumed liquid seeping into the sand. The river had already encroached on this end of the bar, and I and my fellow diners vaulted to the opposite end of the establishment. Now crammed in at the remaining tables, the conviviality of the Sand Bar was everything I’d missed in long weeks working in solitary on this review and other

greasy hands digging into a platter of breaded fried catfish and sweet and salty pretzel bites. A woman sang in a language I didn’t recognize. She embarked on the story of her mother’s sacrifice, something about a terrier, a territory, I wasn’t sure. I nodded anyway, because even though I made out only half the words, I found her voice so moving. Chef Lydia squeezed in next to me with the jug of pear vodka. “We might as well finish it,” she said, while imparting the process that brought it to its flowery fruition. The river tugged at the log I was seated on. Surely the staff will start to heave the crockery onto a dinghy and give a signal for the guests to depart, I thought. Instead, the two waiters stood on the highest remaining ground, discussing a personal issue. Something wasn’t fair, one said. The other agreed vociferously. The river is shallow, but one of my new comrades elaborated on the tricky currents and sudden changes in depth. No one seemed to have a plan. The chef stood with her back to the guests. Gradually all I could make out was the pale gleam of her jacket, and a spark off the neck of the empty demijohn.

Angela is the author of several novels and collections of short fiction. Her work has appeared in "Kenyon Review," "Ninth Letter," and the "LA Review of Books."

A Live Culture Convergence 21

how An EmErgEnCE oF nEw FArmErs is ChAnging ThE AgriCulTurAl lAnDsCApE

By Paul Dietmann

The first Farm Aid concert was held in September 1985 on the campus of the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. I was in the audience. It was a great concert…and a horrible time to be a student finishing a degree in Agricultural Economics as rural America was mired in the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

We lost two generations of farmers during the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. First, we lost the tens of thousands of farmers who suffered through foreclosures and bankruptcies. Then we lost thousands of my peers whose parents survived the Farm Crisis and strongly discouraged their children from becoming farmers. After what they had just experienced, they couldn’t see a positive future for family farmers.

The seeds of the Farm Crisis were sown in the early 1970s. Commodity exports surged, crop prices rose, net farm income doubled, land values soared, and the farm economy boomed. It seemed like the good times would never end. The term “irrational exuberance” had not yet been coined in the 1970s but that describes the mood in rural America at the time. Farmers optimistically borrowed to buy land, borrowed to buy equipment, and borrowed to put their crops in the ground. The impetus was to expand production and narrow operations to the production of just a few commodities. It worked through most of the 1970s until interest rates shot up and the farm economy was thrown into a tailspin.

If an agricultural lender was asked in 1973 to imagine how the farm landscape might look fifty years in the future, the vision would likely have been significantly smaller numbers of farms and farmers, and many more acres per farm. The small, diversified family farm would have become a relic of history.

As an agricultural lender fifty years later, I am happy to report that the farm landscape is more dynamic than my lending predecessor might have expected.

In recent years we have seen an influx of people choosing to become farmers who did not grow up on farms. The wave increased during the pandemic as work-from-home policies made it easier to mix full-time employment with part-time farming. Many of these first-generation farmers are young and energetic without much capital. Others are older people with some financial resources who are switching careers. The operators of many of these farms are women. Some are immigrants to the U.S.; they are first-generation Americans as well as first-generation farmers. Some are people of color. Some are farming in the city of Chicago or other metropolitan areas. The common thread is that they are all seeking to do something more meaningful with their lives, and they find fulfillment in growing healthy food for others.

This cohort of farms tends to be made up of smaller-scale, diversified family operations. Far from being historical relics, they bristle with new energy and optimism for the future. They are growing everything from amaranth to zinnias. They are using regenerative

22 wormfarminstitute.org

They are bringing new cultures to agriculture.

or organic farming practices. They are engaged in agritourism. They are creating value-added products through on-farm processing. They are forming new cooperatives. They are training and mentoring others who want to farm like them. They are active in their local communities, revitalizing towns that had been breathing their last gasps. They are bringing new cultures to agriculture.

I work for Compeer Financial, which is part of the Farm Credit System: a nationwide network of farmer-owned, farmer-led lending cooperatives. The Farm Credit System is the nation’s largest lender to farms, holding approximately 44% of all farm debt. At Compeer we recognized the importance of this new wave of farmers, and six years ago we created our Emerging Markets loan program to meet their unique needs. My colleague Sai Thao and I have had the great fortune of designing and operating

promising Crops For

the program from its beginning. We have closed more than 200 loans and have not yet had a borrower default. I spent the early years of my professional life watching farms die and now I get to see new farms being born every day.

What will the farm landscape look like fifty years from now? I think the number of small, successful, diverse farms will continue to grow. These farms will be located in rural, suburban, and urban areas, and will enrich their communities no matter where they are situated. It will be as common for someone to have a favorite farmer as it is to have a favorite doctor. And anyone who feels a calling to become a farmer will find a place to pursue their dreams.

Paul is a senior focused lending specialist for new markets at Compeer Financial. He provides loans and other assistance to emerging market farmers in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois.

lYrhi Ck #19

Those old women

Champions of porch gossip

Marathon sessions

Begun before dawn

Ending past dusk

Their husbands shaking

Their heads

If I had a dime for every word

That woman has said today

I wouldn’t have to

Play the lottery

They climbed right up

Into families’ family trees

She was a Kampmeier

You know them

Oh I know Kampmeiers

They made plenty of em

That kind of talk

Harmless and empty

They never thought that

Somewhere someone

Might be talking about them

In a poem say

Sort of like this one

—Austin Smith

Austin is a poet from northwestern Illinois who has published three chapbooks and two full-length collections.

A Live Culture Convergence 23

Elderberry

Silphium

Kernza

A phoTosYnThEsis

SAUK COUNTY PANHANDLE 2073

Cordy revved up her ATP and headed west on the 400 Trail like she did every weekday after her shift at Rubisco Foods, smelling faintly of potato starch and carbon. She breathed into the ride and waved at globes of green buffering the Baraboo River as cicadas droned nearby.

“Sometimes it’s good to develop something in private—a bud graft, a taste for black currant, how to metabolize— refining and refining and refining It/ Until, like a peach so ripe and hard pressed for the ache of its absence/It begs us to make use of It or pass it on.”

Cordy’s hazel eyes looked toward the Earth as she pedaled on. The trail soon split near Hemlock Park where wood ducks fledged in quiet pools. She rode past a community cemetery, the elderflower wafting its welcome. Almost home. Cordy could taste the sweet release of recharge.

She arrived at Stomate’s Gate, named for the twin mulleins, erect alongside her driveway. Cordy tossed her green smock in the grass and absorbed the sun as she stood astride the sessile beauty of Yukon Golds in her garden.

She beamed with green, meditated on lines of her favorite poem by RM “…leaf on leaf, magnesium flakes on carbon threads, collecting the heat that now is within/producing in me this hidden thing, a wonder unwordable and so strangely bright…”

She lapped up waning daylight, beholden to electron transport and the promise of protein. All this newfound energy she could alchemize from a breath. All this life she could grow since she opened up to share a slice of my soul; I made the decision to infuse energy into her sunlit heart.

THE PLANT, A FEW DECADES EARLIER

I was at the plant before it rebranded to Rubisco Foods. An explosion along the potato line. Cordy felt the

By Erin Schneider

tremor first. The overburdened spuds blew their lids, spewing skins and eyes from cans. I was among them, shaken. The alarm tripped off sprinklers. Water poured in overhead. Cordy dove toward sunlight, wading through mounds of mash, hoping for sweet release. Her legs gave out, she didn’t know where to root. I just had to intervene.

SAUK COUNTY, A FEW MORE DECADES EARLIER

There was something about her voice alongside her sister’s laughter that set it in motion. They made up songs about picking potato beetles in their garden. Sure, they complained about orange beetle yuck as they squished, but I could feel her breath touch my leaf hairs. I felt free. Something told me the sisters knew how to be with plants. I leaned in, stomates open, feeling the exchange about to happen— Cordy’s CO2 to my O2 plus the ancestral stardust I could finally transfer. Then a loud, “Cordy, Leona, dinner’s ready,” the mom brokered botany’s silence.

Cordy, that must be it: the name the fates foretold and made it worth the transcontinental move from the Andes to this ‘Burg’. With some mystery that comes with being triploid, I was able to keep an eye on Cordy, support her through the lean years of gig work, farming, the occasional poem.

It grieved me when Cordy left the farm, though I didn’t blame her. I, too, rode the highs and lows, famines and bounties of our food system. I experienced the mechanization of physical labor, how I had to steel my resolve while being sprayed, and later how artificial intelligence shifted how humans thought, did business. I also tired of being the ubiquitous side dish, living out my days in a field of monotony for the sake of a chip maker gone bust—watching the light go out of people’s eyes along the way.

I foresaw the human need to (re)learn food production from their hearts. I thought about the role I could play. I also didn’t want to be sacked.

24

wormfarminstitute.org

BACK AT THE PLANT, A FEW DECADES LATER…

Cordy’s touch on my hash-browned skin splayed out on the plant’s floor sparked the old song. Our vitals were weakening fast. I thought now! It’s time to merge. I parted my leaf-lip profile, carbon perfect, wet with molecular splitting, amped up my ATP, and gave Cordy a chloroplast blast. It was a direct hit to her heart. I thanked my stars for the power of transformation, it was just in my DNA.

My exodus began. I beamed. Cordy screamed. A green silence took hold, so strangely bright, breathing forth life’s continuity. Isn’t that enough?

Erin is an administrative associate at the University of Minnesota. Her writing reflects the perennial polycultures she tends at Hilltop Community Farm, which she owns with her husband.

A Live Culture Convergence 25

Mars Patterson is an artist, naturalist, herbalist, educator, and land steward who explores the phenology of nature and the human experience.

wE might A sk somEThing AbouT

a star nothing further while waiting a dog indicating the planet a former meeting fish? Birds? seven feet tall architecture a bird fully twelve feet long may be given spiritual power overcoming the case of life

record the highest man bright vocal the habitation an expert himself from a lower subserved plane pass he cannot write subsequently no difference between the question anticipated and interrupted vocally the flowers spelled Me Me first appeared a pencil and when the little board spelled departure home spelled out discernment so abruptly there Was not night now come tomorrow

I took possession of the board an hour arrived in a country very dark four hundred hours before this country the most beautiful laid a thousand feet to the bottom of an ovoid dazzling light machine it rains daily seeds and cuttings many of them cities accumulate time the period from birth to limit a great deal of Fauna.--tomorrow night himself a beautiful circle ripe for it limited to the cities daily nor a kind of stalk

Would it not be possible to bring some polar goat herd four hundred Sunday about 6

Pardon me it seemed he did not want a level world

eight thousand mammalia swamp the oceans follow sitting and talking a vast illustrious memory spelled business on the staff of time

Tell him I would like to later introduce a spirit the deep mining human diamond so like a Dog The present

rested at the bottom of the table

—Philip Matthews

Philip is the director of programs at Wormfarm. He has authored two books of poetry.

This poetic erasure of transcripts of seances conducted in April 1906 by U.S. Commissioner of Agriculture William G. LeDuc and associates, with various spirits including that of Charles Darwin, owes special thanks to Kate Wersan (Savanna Institute) and Colin Dunn who shared the source (Spirit Communications. William G. LeDuc and family papers. Minnesota Historical Society.)

26 wormfarminstitute.org

A Live Culture Convergence 27

Katie Schofield is a visual artist who lives in rural Wisconsin. When she isn't drawing comics about her daily life and thoughts, she works at a public library and an organic vegetable farm.

unDusT mY lEAvEs

DIARY ENTRY, SUNDAY, JULY 6, 2070

A new colleague in our lab made an unusual request, to access my late mother’s plant-soil research entitled “seance-sorium.” She didn’t know we hadn’t spoken in years, but how could she have known?

I agreed with her request. Sunday morning, my partner and I drove to her place. The house had been abandoned since her death, so I was expecting total disarray. To our surprise, the gardens looked impeccably groomed. The trees she’d planted had grown at astonishing speed; they looked like a grove of oldgrowth forest. We parked next to the front door, and I rushed to unlock it. The house felt alive—my mother’s presence was so strong. I fell to the ground in tears. My partner said, “It’s ok. Let’s find the box with the research papers so we can go.” The box was in the exact place where her lover had told us to find it.

DIARY ENTRY, TUESDAY, JUNE 16, 2071

An enormous bouquet of flowers, including several orchids, arrived at the lab. Nestled in the blooms was a thank you note; “Your mother’s research notes were the missing piece, enabling us to solve the puzzle of plant communication.”

Later that day, I ran into my colleague. She paused to say, “You always look so sad; let me recite a funny

by Patricia Tinajero

note from one of your mother’s texts.” I wanted to say no, but she continued immediately.

The note comes from a short article in the University Student Gazette. “‘Undust my leaves’ are the first words exchanged between plants and humans. The process is complex, but the explanation is simple,” said MPT—speaking on behalf of her research team, Plant Contingent—“The orchid’s trembling petals have modulated their vibration frequency to accommodate the range of perception of the human ear.”

She paused again to look at my expression, then continued, “But this is not the strangest part of the article.” Her voice became excited as she continued: “‘An extraordinary event has indeed occurred at the U. of Chicago Steam Urban Lab. During the presentation of the seance-sorium, plants began speaking! The entire campus has now begun to hear plants speaking. Students claim that the plants have one significant request; they demand that their leaves be dusted. We don’t know what to call this: art, science, or madness?’”

Note to self: mystery of mother’s garden.

28 wormfarminstitute.org

Art by Sam Jones

IMAGINE A GATHERING PLACE FOR THE NEXT 100 YEARS

Sauk County, WI 2023

Wormfarm is organizing listening sessions to imagine the future of Witwen Park, a former church campground that has been a gathering place since 1918. We’re inviting neighbors, historians, farmers, artists, conservationists, community leaders, architects, visitors, and YOU to help us.

How might this unique historic asset capture the imaginations of future generations?

—WILLIAM BLAKE

WHAT IS NOW PROVED WAS ONCE ONLY IMAGINED.

TO SOLVE PROBLEMS YOU NEED TO GO OUTSIDE YOUR DISCIPLINE. —ALDO LEOPOLD

30 wormfarminstitute.org

Max Sorenson is an interdisciplinary artist and former Land Stewardship Fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation.

Prairie Sage Barn Quilt 2073

grEETings, homo sApiEns!

Remember that glitch in the system back in 2027?

Aldo Leopold Foundation

Yeah, Earth almost went belly-up. But humanity debugged, installed the "land ethic" patch, and ta-da! Wildlife got a major power-up.

Thanks to your eco-conscious decisions, forests have never been trendier, oceans are less grumpy, and species diversity is a party! Aldo Leopold would make a fist and bump it! In 2073, wildlife's throwing a rager, and guess who’s invited? You! Because you've gone from "Error 404: Environmental Awareness Not Found" to "Species Savior Extraordinaire."

Book your Leopold Shack visit today for <33 Emusts, and witness the legacy of humanoid Aldo Leopold come alive, nestled amidst Earth’s reinvigorated landscapes. Let's keep playing the sustainable game, leveling up our actions. The Land Ethic expansion pack isn't just saving the day—it's revolutionizing our cosmic score. Keep it green, Earthlings!

A Live Culture Convergence 31

Art by Pete Hodapp

DivErsiTY nurTurEs nATurE

by Wilda Nilsestuen with support from Bill Berry

Farming is the most place-based of professions, and farming in Wisconsin and beyond is beginning to embrace the diversity that nurtures nature. There is remarkable variety in Wisconsin’s physical features of terrain, soil types, weather, farm sizes, farm practices and, to some degree, crops. So, too, is there a growing diversity amongst farmers and farm workers.

Growing evidence of the real world impacts of climate change and rapid advances in technology raise public awareness and acceptance across disciplines of the existential necessity to adapt to the new realities and to innovate diverse solutions in response to them. Regenerative agriculture, the soil health movement, a better understanding of the ability of agricultural practices to build soil organic matter and capture carbon: Farmers who use these practices say they take a while to adopt, but once in place lead to better productivity, more profit, and resilience to climate extremes. These changes, along with the changing face of the workers who sustain our farms, are hopeful trends for the future.

People of color will increasingly constitute a larger percentage of Wisconsin’s population. A widening spectrum of diversity and associated increases in population require addressing social and political inequalities that have too long been neglected. This has implications for the state’s economy, the nature of community, and related requirements for education, health care, transportation, and basic services as well as population distribution. These trends have been at work for decades, as longtime organizer Jesus Salas makes so rivetingly clear in his recent autobiography Obreros Unidos Salas was among the migrant laborers who demanded and earned decent living conditions, pay and, most importantly, respect for the back-breaking work they did and continue to do in rural Wisconsin. He and others went on to focus on similar issues in Milwaukee and our state’s higher-education system.

It is encouraging to read of their success, but the work continues today. And make no mistake: Wisconsin needs migrant and immigrant workers. By one recent estimate, immigrant farm workers provide 80 percent of the farm labor that brings Wisconsin dairy products

to the state, nation, and world. The demand will only grow. Wisconsin has an aging population. That fact has immediate, glaring implications for employers in need of more workers, school systems with declining enrollments, growing health care demands for seniors, and city/community planners who deal with a fading past and envision a thriving future.

Immigration already plays a significant role in addressing the workforce needs across many sectors including agriculture and food processing, health care, construction, manufacturing, finance, service industries such as restaurants, and childcare. The diversity will only continue to grow in the coming decades. Twenty to forty years hence, Wisconsin communities, including small rural settings, will look different on Main Street. This trend is already underway. Consider what has transpired over the past several decades in Arcadia in Trempealeau County. The school population is at least 70 percent Latino, with an even higher percentage at the lowest grade levels. Main Street now includes three Latino grocery stores, several bars, barber shops, restaurants, and other businesses under Latino management. Longtime businesses include Latino staff. The two largest employers—Ashley Furniture and Pilgrim’s Pride —have substantial numbers of Latino employees. With this increase in diversity has come an increase in population. In a small rural community, this puts pressure on basic services. While the latest census shows an increase of well over 1,000 residents, there are many more who commute to Arcadia for work from other communities due to a lack of housing, childcare, social services, and social interaction opportunities.

“Many voices to the table” was the mantra of the threeyear Future of Farming and Rural Life in Wisconsin project, which I directed from 2005 to 2007. It was an effort to gather statewide the views, voices, and status of rural Wisconsin from all sectors, and from rural and urban citizens with sometimes conflicting perspectives. Recognizing diversity was a priority of the project. Now, embracing diversity as integral to economic prosperity and social justice will be key to navigating the transitions the coming decades will demand from us.

Wilda is a community organizer who directed the Future of Farming study, a Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters report about the future of rural life in Wisconsin.

32 wormfarminstitute.org

about rocks and whatnot. The buzzy song of a black-throated green warbler floated by on the breeze, drawing me onward to a shady streambank. I paused, pondered the shapes flitting about in the water at my feet. An hour in, I heard voices from upstream. I tend towards places that are less traveled, and was surprised to encounter people back here. As I got closer, I could hear the plunks of rocks being tossed into the water. Without having any idea why, or what, or who, I felt myself getting grumpy, wondering who these people were and why they were disturbing the peace.

I rounded the bend, and encountered the culprit: a family exploring the stream. A dad sitting on the bank snacking on crackers, and two young kids wading up to their

and without a moment’s thought said, “Hello! I’m finding cool rocks! Have you seen any cool rocks?” The dad, looking a little embarrassed, said to me, “Well, now that school’s out, at least we get to spend some time doing this kind of thing.” Before long, I continued on, the soft slurping of the stream and the tumbling of rocks fading away. I could still feel the corners of my mouth turned up in that smile as I thought to myself, ‘Shouldn’t we be able to explore and become enchanted with the world without school having to

100? Will shouting about sparkly rocks home to tiny critters scuttling between nook and cranny be important? I hope so. I often ask myself, what can I do to ensure the future of these magical places and the experiences they provide? How do we as a community build a group of resilient, thoughtful, caring, passionate citizens who are rooted in a place and understand its complexities, human and nonhuman?

I hope that, some summer afternoon far from now, I’ll hike back into that same stream gorge and find some kids splashing around in the stream. Maybe they’ll look up and say hi, ask me if I’ve found any cool rocks.

Angus is a first grade teacher at Tower Rock Elementary School in Prairie Du Sac, a musician, and an ecologist.

A Live Culture Convergence 33

A r El ATivE pA ssE D

by Lexi Ames

Some time ago, rural Midwesterners returned to the practice of caring for their dead by hand. In little forest glades, and rolling oak savannah, farmers lay their kin to rest on the very land they tended, and the land tends to them in turn. Neighbors create burial quilts and shrouds from plant and animal fibers that will return to dirt. Grave markers are provided by stones picked from tilled fields. Wake food is brought up in jars from cellars and conjured from yellowed, crumbling recipe cards. Fellow planters dig the grave, drive the old horse cart that hauls the body, and whistle a beloved tune for the funeral dirge. There is nothing new or radical about family cemeteries, burial sansembalming, or holding funerals at home, but we have chosen to make this communion common-place once more.

Lexi is a deathcare worker and science illustrator. Her artwork pursues the biology of death and decomposition, deathcare traditions, and green cemetery practices.

34 wormfarminstitute.org

gAThErings

by Philip Hasheider

Consider this: the answers to our problems already exist. We simply need to discover them. The answers for preventing smallpox and polio had already existed as a potential three thousand years ago. But it took society’s development to reach a threshold of knowledge to ask the appropriate questions before that cure could be envisioned and implemented.

To envision our rural place fifty years from now is to set an intention that we will arrive on that shore in a better state than we occupy now. I think of my own lineage as a bridge to that future.