2 minute read

THE ENDURING MEANING OF memorial days

by Anastasia Minkovska

The concept of memorialization is as old as human culture. While it varies significantly from country to country, the central ideas remain the same. Memorialization is an essential step in a grieving process that satisfies the desire to honor those who suffered or died during a conflict. Its practice serves as a means to examine the past and address contemporary issues. Acknowledging those who suffered or died is an essential way for communities to make sense of the human cost of war.

Advertisement

“To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

—Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor, writer, Nobel Peace Prize winner

In most countries, public gatherings incorporate memorial services and marches of former soldiers and military officers, which are accompanied by an orchestra and follow the minute of silence. However, January 27th, which we recently observed at WINS, is different. This is the International Holocaust Remembrance Day in which the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz – Birkenau is observed. On this day, people all around the world honor the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust and 11 million other victims of Nazism. More than 75 years after the end of WW2, this memorial is more important than ever.

In November 1938, antisemitism took a violent turn in Germany. Organized groups of Nazis burned hundreds of synagogues, killed almost 2,000 people, and arrested another 30,000 who were later sent to concentration camps. Police had been ordered not to intervene. This was called the Kristallnacht (night of broken glass) and it marked the beginning of the Holocaust, where many citizens became spectators of violence. Several intervened and tried to withstand the atrocity; however, the majority preferred to stay silent and not hinder the mass murder of innocent people.

The Holocaust is central to Germany’s culture of remembrance. Acknowledging the country’s historical guilt for the crimes committed during World War 2 is a fact of life. 50 years after Kristallnacht, on the site of Berlin’s first synagogue, a memorial was built. The Nazis had used the synagogue as a place to round up Jews for deportation. From here, they were loaded into trucks or forced to walk to the freight train station.

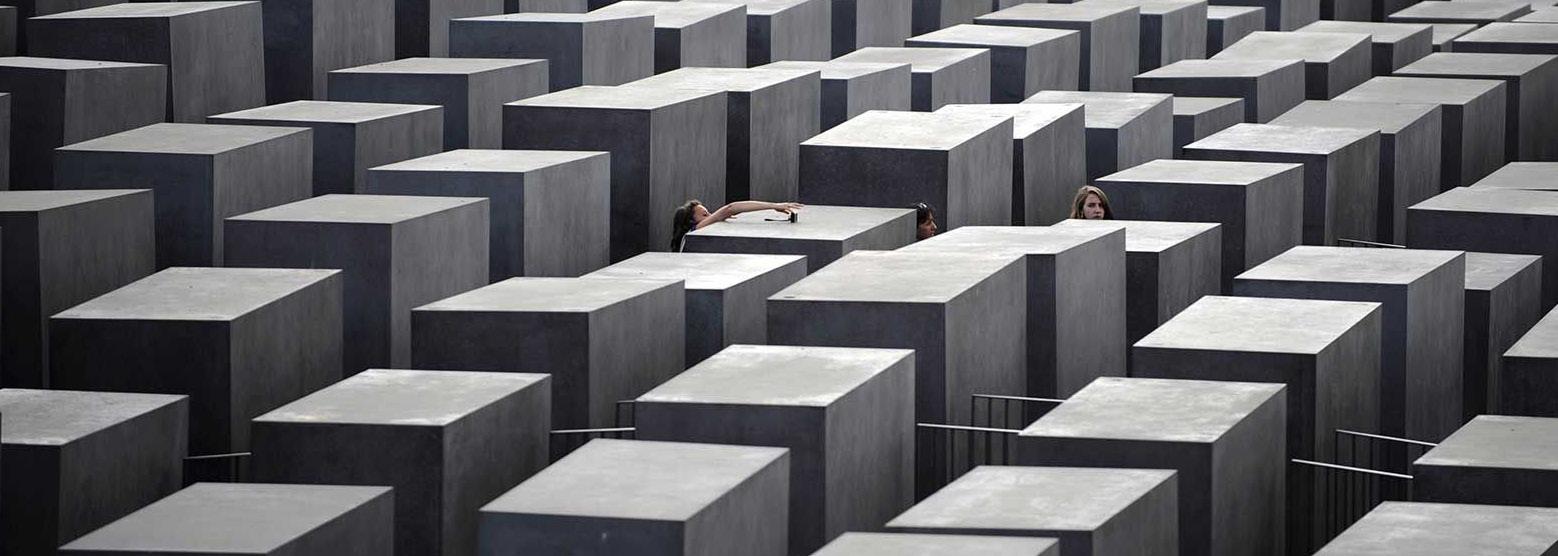

After the war, only 37,000 Jews were left in Germany. Many years later, the push to create a national Holocaust memorial came largely from “within German society” (non-Jewish communities). The country then oversaw one of the most profound memorials in the world: the memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe, by architect Peter Eisenman. In all, 2,711 concrete stelae of different heights were composed to awe visitors into silence and contemplation. “The space resembles a graveyard, a vast cascade of stone markers with no names or engravings on their facade. The ground beneath them dips and rises like waves,” write Clint Smith of The Atlantic. Nevertheless, the way Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial is treated is tricky. Some choose to engage with the sacred space irreverently. Today, it could be argued that “it’s lost its purpose and meaning. Or maybe it never had it.”

Sooner or later, the commemoration of the victims of wars, in particular, victims of Nazi crimes, will have to continue without the people who witnessed the atrocities first-hand. This raises the question: for how long can we meaningfully preserve the memory of past tragic events? Can we keep that memory alive like a flame for future generations or not?