Art, Artists, and the White House

the white house historical association

Board of Directors

chairman

John F. W. Rogers

vice chairperson

Teresa Carlson treasurer

Gregory W. Wendt secretary

Anita B. McBride president

Stewart D. McLaurin

matthew algeo is a writer and journalist. He is the author of seven books, including the forthcoming When Harry Met Pablo: Truman, Picasso, and the Cold War Politics of Modern Art.

Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African American Family.

Eula Adams, Michael Beschloss, Gahl Hodges Burt, Merlynn Jean Case, Ashley Dabbiere, Wayne A. I. Frederick, Deneen C. Howell, Tham Kannalikham, Metta Krach, Barbara A. Perry, Ben C. Sutton Jr., Tina Tchen

Eula Adams, John T. Behrendt, Michael Beschloss, Gahl

Hodges Burt, Merlynn Carson, Jean Case, Ashley Dabbiere, Wayne A. I. Frederick, Deneen C. Howell, Tham Kannalikham, Metta Krach, Martha Joynt Kumar, Barbara A. Perry, Frederick J. Ryan, Jr., Ben C. Sutton Jr., Tina Tchen

national park service liaison

national park service liaison

Charles F. Sams III

Charles F. Sams III

ex officio

ex officio

Lonnie G. Bunch III, Kaywin Feldman, Debra Steidel Wall (Acting Archivist of the United States), Carla Hayden, Katherine Malone-France

Lonnie G. Bunch III, Kaywin Feldman, Debra Steidel Wall (Acting Archivist of the United States), Carla Hayden, Katherine Malone-France directors emeriti

directors emeriti

John H. Dalton, Nancy M. Folger, Knight Kiplinger, Elise K. Kirk, James I. McDaniel, Robert M. McGee, Ann Stock, Harry G. Robinson III, Gail Berry West

John T. Behrendt, John H. Dalton, Nancy M. Folger, Knight Kiplinger, Elise K. Kirk, Martha Joynt Kumar, James I. McDaniel, Robert M. McGee, Ann Stock, Harry G. Robinson III, Gail Berry West

white house history quarterly

founding editor

William Seale (1939–2019)

editor

Marcia Mallet Anderson

editorial and production manager

Margaret Strolle

associate vice president of publishing

Lauren McGwin

senior editorial and production manager

Kristen Hunter Mason

editorial coordinator

Rebecca Durgin

consulting editor

Ann Hofstra Grogg

consulting design

Pentagram

editorial advisory

Bill Barker

Matthew Costello

Mac Keith Griswold

Scott Harris

Joel Kemelhor

Jessie Kratz

Rebecca Roberts

Lydia Barker Tederick

Bruce M. White

the editor wishes to thank The Office of the Curator, The White House

ken beckman is an actuary, a nonprofit executive, and the founder and developer of an educational website focused on the U.S. presidents, PresidentsUSA.net.

troy elkins has worked on the curatorial team at the Eisenhower Presidential Library for eleven years. A U.S. Marine veteran, he is a PhD candidate in history at Kansas State University.

sarah e. fling is a historian at the White House Historical Association.

lauren mcgwin is the Associate Vice President of Publishing at the White House Historical Association and a frequent contributor to White House History Quarterly.

james h. johnston is a lawyer and writer in Washington, D.C. His books include Murder, Inc., The CIA Under John F. Kennedy and From Slave Ship to Harvard:

Met Truman, Picasso, the Cold Art associate vice president of Publishing at the White Inc., The Under John Kennedy and From Slave to

jeff nelson has been with the Eisenhower Presidential Library for six years. He has a master’s degree in history from Kansas State University and specializes in military and diplomatic history.

estill curtis pennington is an art historian who focuses on the study of painting in the South. His most recent published work is Matthew Harris Jouett (1788-1827): His Life and Work.

nikki pisha is the associate curator of fine arts in the Office of the Curator, The White House.

william snyder is a curator at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum.

and the of African Family Work. Rembrandt A the Arts.

carol eaton soltis is project associate curator in the Department of American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She is the author of the first substantive catalog and exhibition on Rembrandt Peale, Rembrandt Peale: A Life in the Arts.

First Lady

Jacqueline Kennedy accepts a gift for the White House Collection from Sears, Roebuck and Company of five portraits of Native Americans painted by Charles Bird King. The gift is presented by Sears vice president, James T. Griffin, who holds up a portrait of Chief Shaumonekusse of the Oto tribe, December 6, 1962.

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PORTRAITS OF PRESIDENT AND MRS. BARACK OBAMA David Rubenstein’s Conversation with the Artists, Robert McCurdy and Sharon Sprung

THE PEALES IN THE WHITE HOUSE

WHEN HARRY MET PABLO The Strange True Story of the Day President Harry Truman Spent with Artist Pablo Picasso

PAINT-BY-NUMBERS : A Christmas Gift to President Dwight D. Eisenhower

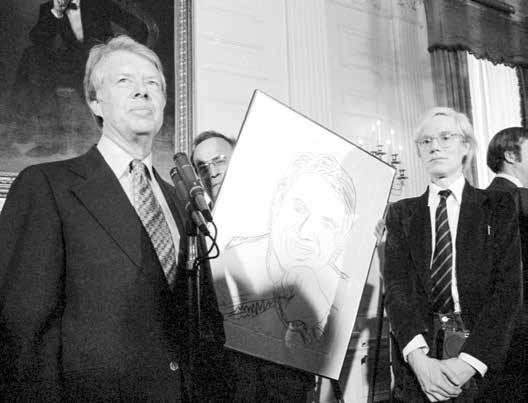

ANDY WARHOL VISITS THE WHITE HOUSE

PRESIDENTIAL SITES FEATURE

“A Changing Portrait of America”

a visit to the president’s house is a visit to an exceptional museum of America’s art. Many first-time guests may actually be surprised by the extent to which the paintings that line long corridors and fill stately rooms serve as an immersion into the American experience. Comprised of approximately five hundred paintings, drawings, and sculptures, the White House Collection of Fine Arts chronicles the nation’s founders, leaders, and heroes, its monuments, shores, and natural wonders, and its victories, struggles, and iconic moments. The late journalist Hugh Sidey perhaps explained this best when he observed, “The White House is its own canvas, never completed nor meant to be, but a changing portrait of America . . . a constant reminder to all who walk therein of where we have been and where we are going.”

Representing evolving aesthetics and a progression of styles from classical portraiture to abstract color-fields, this body of work of a nation is also the story of America’s artists. With this issue of White House History Quarterly, we look at the lives and work of the earliest and the latest artists in the collection, we meet one of the first artists of the President’s Neighborhood, we explore president’s relationships with the art and artists of their time, and we follow the journey of a controversial painting as it is shuttled in and out of the White House.

Every new White House acquisition captures the nation’s attention, especially when presidential portraits are unveiled. We open this issue with David M. Rubenstein’s recent conversation with Robert McCurdy and Sharon Sprung, which provides a special behind-thescenes glimpse of the personal experiences of the artists commissioned to paint the new portraits of President and Mrs. Barack Obama. Looking back to the earliest White House portraitists, art historian Carol Soltis introduces us to “America’s First Family of Artists,” the Charles Willson Peale clan, who captured from life the likenesses of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson as well as the early White House architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Not all presidents have embraced the avant-garde, as Matthew Algeo explains in his account of the day President Harry Truman spent with Pablo Picasso. Although modern art gave Truman nightmares, he was convinced to pay a visit to Picasso in France, and, while he might not

have changed his mind about the art he found in the artist’s studio, the encounter itself made history. Truman’s successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, a painter himself, was delighted when the 1950s craze for painting-by-numbers resulted in a unique Christmas gift from his staff, as Troy Elkins, Jeffrey Nelson, and William Snyder reveal. Lauren McGwin demonstrates that some presidents did embrace the avant-garde as she chronicles Pop artist Andy Warhol’s friendships with the Fords, Carters, and Reagans. Creating campaign posters and presidential portraits, Warhol was a frequent White House guest for nearly a decade.

Explaining that an ongoing goal in building the White House Collection is to ensure that the diversity of American artists is well represented, Nikki Pisha tells the story of the 2020 acquisition and installation of Isamu Noguchi’s Floor Frame, the first work by an Asian American in the collection.

The study of the White House Collection sometimes yields surprises. With his article “Matthew Harris Jouett and Gilbert Stuart: Pupil and Master,” art historian Estill Curtis Pennington makes a convincing case for the reattribution of a White House portrait of Thomas Jefferson, long believed to be by Jouett, to Stuart himself.

James H. Johnston presents the story of James Alexander Simpson, a prolific artist of the early President’s Neighborhood. Though few of his paintings survive today, Simpson’s extant works document the people and places of the nation’s capital that would have been known to the early nineteenth-century presidents.

The collection has not been without controversy, as Sarah E. Fling explains in her piece on Love and Life, a painting given to the American people by the wellmeaning English artist George Frederic Watts. Banished to the Corcoran Gallery of Art by first ladies who found it inappropriate for the White House, yet openly displayed by other first ladies who appreciated its quality, the work came and went from the President’s House for half a century.

For our quarterly presidential sites feature, Ken Beckman takes us to Omaha, Nebraska, the birthplace of Gerald R. Ford. Although the grand home in which the future president spent the first few days of his life was lost to a fire, a specially designed park now commemorates the site.

Pastoral Landscape, painted by Massachusetts artist Alvan Fisher in 1854, was acquired for the White House Collection by the White House Historical Association in 1973. The tranquil mid-nineteenth century landscape captures a shepherd and his dog watching over grazing sheep and cattle.

THE OFFICIAL White House

Portraits of President and Mrs. Barack Obama

David Rubenstein’s Conversation with the Artists, Robert McCurdy and Sharon Sprung

previous spread

President Barack Obama speaks to guests at an East Room ceremony held to unveil the new official portraits of himself and First Lady Michelle Obama. Following the ceremony, members of the Executive Residence operations crew hang the president’s portrait in the Entrance Hall, September 7, 2022.

throughout the white house, the walls of State Rooms, corridors, and both public and private spaces are hung with portraits of the nation’s presidents and first ladies. In recent years the collection has been built with the support of the White House Historical Association, which commissions portraits of each outgoing president and first lady to be given to the permanent collection of the White House. In keeping with tradition, the Association commissioned portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama in late 2016. On September 7, 2022, the two completed portraits were unveiled during an ceremony in the East Room.

Artist Robert McCurdy had painted the president, while artist Sharon Sprung had depicted the first lady. That evening, financier and philanthropist David M. Rubenstein moderated a lighthearted discussion with them following a dinner at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The namesake of the White House Historical Association’s David M. Rubenstein Center for White House History, Rubenstein is a generous supporter of the Association’s work and has, for nearly a decade, offered wise counsel and friendship to me.

The transcript of the conversation that follows is peppered with humor. As Rubenstein asked Sprung and McCurdy about their careers, their artistic processes, and their experiences painting the historic works of art, an unexpected banter filled the room with laughter.—Stewart D. McLaurin, President, White House Historical Association

David Rubenstein: Sharon why don’t we start with you; did you always want to be an artist when you were growing up?

Sharon: Yes, actually I did.

You didn’t want to be in private equity or anything?

Sharon: No. [laughter]

Okay. So you initially start out and you went to Cornell.

Sharon: I did.

And how many years did you last there?

Sharon: Not long. [laughter]

Not long. Okay, so you went to art schools to make sure you could be an artist?

Sharon: I actually contacted three artists whose work I loved: Aaron Shikler, Daniel Greene, and Harvey Dinnerstein, and asked them, “How do I become an artist?” I ended up at the Art Students League of New York and the National Academy.

And Aaron Shikler, whom you contacted, was the person who painted the famous Kennedy portraits that are in the White House now. I assume he inspired you to do this work.

Sharon: No. [laughter]

David

M.Rubenstein moderates a discussion with the two artists who painted the Obamas’ official White House portraits, September 7, 2022. Robert McCurdy, seated on the left, painted the president’s portrait, and Sharon Sprung, center, painted the first lady’s portait.

Let me ask you again, did he have nothing to do with your interest in doing this work?

Sharon: His paintings are very inspiring but, no, at the time I was 19 and I just couldn’t envision this, no.

But now you do portraits full time?

Sharon: No.

What do you do?

Sharon: I paint my own paintings and have shows in New York City in Chelsea at Gallery Henoch, and I teach two mornings a week at the Art Students League and then I do my portraits.

And your studio is in Brooklyn I know. And I came to visit you one time.

Sharon: You did.

When we were looking at commissioning a portrait and you rejected me as I recall.

Sharon: That’s not exactly how I recall it. [laughter]

So when did you get the White House portrait assignment?

Sharon: It must’ve been 2016.

And did you have a meeting with President Obama and Mrs. Obama?

Sharon: We had a meeting in the Oval Office.

Wow, and at the time were you thinking you were

going to do both of them or just one of them?

Sharon: Well I thought I was just there to do Michelle Obama, but when I walked into the Oval Office, President Obama said, “Well why can’t a woman do me?” I wasn’t prepared for that, but why not?

So, you went in and you had your talking points. Sharon: I did have my talking points, and they were called talking points.

I know, but you handed out the talking points to the other people?

Sharon: I did. I handed out five copies.

Of your talking points?

Sharon: Of my talking points. And then the president just went “shwoop,” he threw them off to the side. [laughter]

Did that make you nervous?

Sharon: It made me incredibly . . . I said, “Well, what if I forget everything I wanted to say?” He said, “You’ll be fine.”

So after you had that session, when did you hear you were going to get the assignment?

Sharon: Six long months.

It took six months? So, did you think you weren’t going to get it?

Sharon: No. [laughter]

Boy you’re an optimistic person. Wow, okay. So when they called, who called you to say you got it?

Sharon: That’s not exactly what happened. Every six weeks or so I’d call them.

And what did they say? “We’ll call you?”

Sharon: Yes.

You know what that usually means?

Sharon: No. [laughter]

Usually it means “probably no,” but it worked out, right?

Sharon: It did work out.

So, who actually called you in the end?

Sharon: Well they didn’t call me, I called them, and they said, “You’ve got it.”

Really? Wow.

So, Robert, in your case, did you always want to be an artist when you were growing up?

Robert: I did, I grew up in a very small suburb in Pennsylvania that had an extraordinary school, a public school, that had an art program so I could be an art major as a high schooler.

left

First Lady Lady Bird Johnson accepts a portrait of Eleanor Roosevelt by Douglas Chandor, February 4, 1966. The painting was purchased by the White House Historical Association from the artist’s widow. Since that time the Association has continued to acquire for the White House portraits of presidents and first ladies not yet represented in the collection, with recent presidents selecting the artists to be commissioned.

below

President and Mrs. Jimmy Carter welcome President and Mrs. Gerald Ford at a ceremony to unveil their official portraits, May 24, 1978. President Ford was painted by Everett Raymond Kinstler, and First Lady Betty Ford was depicted by Felix de Cossio.

right President and Mrs. Bill Clinton stand beside their official portraits by Simmie Knox during the unveiling ceremony hosted by President and Mrs. George W. Bush, June 12, 2004.

below President and Mrs. George W. Bush unveil their new official portraits by John Howard Sanden in a ceremony hosted by President and Mrs. Barack Obama, May 31, 2012.

And so, you basically knew what you wanted to do. What type of art? Any type of art, or did you know exactly what you wanted to do?

Robert: Well, when I was quite young, it was all just a matter of sorting it out. When it finally got to a point where I could think about these things in a cohesive way, I was entering a world where minimalism and conceptualism were at their height. They say you always react to the point that you entered the art world, so those subjects still fascinate me. It took decades for me to sort out what I wanted to do with them, but that’s where it all starts, it starts with this idea of minimalism.

Eventually, you got into a kind of art that we see here, which is a “minimalist,” you would say, type of portrait. Is that how you would characterize the portrait?

Robert: It would be a way to talk about it, yeah.

You have a unique technique, which is basically that you have an elaborate camera, which you can describe, and then you take lots of pictures. In how many days do you do it? And then do you see your subjects again?

Robert: That’s right, normally the sitting lasts only an hour to two hours. But before we start shooting, I always talk to the people who are going to sit for me about what we are trying to achieve. And it’s a pretty simple story, we’re looking for a moment where there’s no time. If you were to take a string of images and lay them all on top of each other, it would virtually be the same. I didn’t want a “before” or an “after,” so nobody gestures, nobody smiles, there are no backgrounds, there are no props, we are not telling the story of the person in the painting, we’re setting up an encounter between viewer and the subject. Everybody [the subjects I paint] has to sign off on that.

You have an elaborate camera, a very expensive camera that you use.

Robert: Yes, we rent it, because it’s way too expensive to own.

And then, when the subject comes in, do you take the pictures, or does the photographer take the pictures?

Robert: I drive the camera, in the sense that the camera is in front of me, the monitors are in front of me, my fingers are on the trigger. But cameras at this

stage and at this level are far too complicated for one person to operate, so there is a digital technician who runs the other side of it.

So, with President Obama, when did you first meet him about this?

Robert: It would’ve been about the same time as Sharon’s meeting. It’s been so long ago I can barely remember.

Did you keep calling him every couple weeks saying, “What about me?” Or how did it happen?

Robert: No, we met at the Oval Office. We had this speech about what we were trying to achieve, and then eventually somebody called and said, “Okay you should go ahead with this.” And we did.

Now some of the other prominent people that you have painted are Toni Morrison and the Dali Lama. Who were some of the other very wellknown people? Did you do Warren Buffett as well?

Robert: I did do Warren Buffett. And Neil Armstrong, Gabriel Garcia Márquez, Nelson Mandela, a lot of wonderful people.

So, you take the pictures, and someone has to give you an hour, two hours of their time.

Robert: They do, yeah.

So, where did you do the photos of President Obama?

Robert: We did them in a hotel across from his office, we rented a ballroom. When we shoot it is a rather elaborate setup, so we’re flying 8 × 8 butterflies and these giant lights, and we need a pretty significant setup.

Then you have all the photos, then you figure out which one you want and you destroy all the rest?

Robert: That’s right.

Why not save them for an archive or something or another?

Robert: I never wanted the photographs to compete with the painting. The photographs are disposable construct, they serve the painting. Once that’s done, we try and eliminate everything that’s not essential to what we’re doing.

The most recent official presidential portraits are traditionally hung in the Entrance Hall on the State Floor, where President Barack Obama’s portrait hangs today.

And when you get the photograph you want, you begin painting. It takes you how long to actually do something like that?

Robert: Usually about eighteen months.

And you do nothing else, professionally, during that period of time?

Robert: That’s right. [laughter]

You don’t want to be distracted by painting somebody else, a private equity person or anything?

Robert: No private equity assignments, private equity persons are a whole other thing. No, I only make these paintings. I don’t do drawings. I don’t do photographs or other support material.

So, for eighteen months, every morning, you get up and you look at what you’re painting, and you say, “I don’t like it,” or “I like it,” or how does that work?

Robert: Yes, that’s about it. I’ll get up every morning and I’ll go to work. Usually I have an area that I’ll target for the day, and I’ll concentrate on that, and then I kind of move around the painting a bit as it builds. It’s kind of a combination of really small gestures and really big gestures.

Normally if you’re painting something you might say, “I’d like your opinion,” to somebody, maybe a friend of yours. But here, you had a contract that says you can’t talk about it, so how could you show anybody what you were doing? Or were you still able to do that?

Robert: I never show anybody. Anyways, I know what I want so I just go for it. [laughter]

Your daughter is here, where is your daughter?

Robert: She’s over there.

She’s an artist as well. Did you show it to her?

Robert: [to his daughter in the audience] Did you see it?

She snuck in and looked at it from time to time. [laughter]

So, Sharon, how long did it take you to paint this picture?

Sharon: I’d say eight months.

Eight months, so you work quicker than Robert?

Sharon: It doesn’t feel that way, but yes.

So, let me ask you, the off-the-shoulder look, it’s a little risqué for a first lady, wouldn’t you say?

Sharon: No. [laughter]

You told me earlier that you’ve seen other first ladies act something like that.

Sharon: Yes. They are a little risqué, all of them, the first ladies.

Okay. So at what point did you finish this and show it to Mrs. Obama?

Sharon: Probably six or seven months after it was finished.

After it was finished?

Sharon: After it was finished.

So, for six or seven months you didn’t show it to anybody?

Sharon: No.

So why not? You didn’t want to show anybody what you’d just done?

Sharon: Well, I did show my husband.

And what did he say?

Sharon: He’s a big supporter.

So, when you showed it to Mrs. Obama, the first time, what did she say?

Sharon: She didn’t say anything, and that’s when I knew that she liked it.

Really? Okay. Well, that’s good.

Robert, when you showed the portrait to President Obama, what did he say?

Robert: I wasn’t there.

You weren’t there?

Robert: I wasn’t there. I wasn’t there when he saw it.

Did he e-mail you and say “I like it”?

Robert: No. Actually, I never [got feedback] one way or another through the whole process.

Following

But when you saw him today, did he say, you know, “I didn’t tell you this, but I really do like it.” He didn’t say that?

Robert: He said, “It’s okay.”

Now it’s very stark in the sense that as you mentioned, you don’t have any books, you don’t have any props, you have nothing there, and you just have him—and that’s your standard way of doing this?

Robert: Yes, all the paintings look the same.

And when you’re finished, what do you do with that one photograph that you have? Do you destroy it?

Robert: I destroy that as well.

So, you have no photographs, you have no archives, or anything like that?

Robert: Mmhmm, nothing.

Okay, and you couldn’t tell anybody, right? So didn’t you want to tell your best friend, “Guess what? I got this great assignment!” You can’t tell

anybody.

Robert: No, I couldn’t tell anybody, that was part of the deal.

For either or both of you: Presumably when we talk about an author who’s written a book on somebody, and they’ve spent three or four years of their life on that person, usually they like the person. Usually. Because they had to spend three or four years of their life on it and usually you don’t want to do that with someone you don’t like. Could you have painted this if you didn’t like the person?

Sharon: Not as well.

Not as well. You could paint a little bit but not as well. And what about you, Robert?

Robert: Oh sure. I wouldn’t want to, but I certainly could.

So, when you, both of you, when you finish these works you have to get them down to the White House. So, do you bring them in your car?

Sharon: Well, there’s a little more to it than that.

What do you do?

Sharon: Well, I have to know when it’s done, which is a hard decision to make. So you’re with this painting all the way, and I work very much like you do Robert, you go around the painting, you see what you want to do in the morning, what’s wrong, what the painting is saying needs work and then eventually you go in and it breathes. When you walk in the studio and the painting is breathing, you know it’s done. Then you call the shippers, and then you’re out of it.

Call the insurers as well. [laughter]

Okay, so Robert, you don’t paint anyone else when you’re doing this, for eighteen months this is what you do?

Robert: Yes.

Sharon, do you paint anybody else during the same period?

Sharon: I try to work on two paintings at a time, because otherwise I get so obsessive about one I don’t really see where the mistakes are. So it’s good to create a little distance. That’s what I’ve learned over the years. If I keep working on it I can’t see it anymore.

So, every couple weeks do you show it to your husband and you say, “What do you think today?”

Sharon: Well, our bedroom is next door, so, you know, he has occasion.

All right, so today you must’ve had a great time at the White House, meeting with the first lady and the president. Was it one of the highlights of your career?

Sharon: I think the highlight of my career was meeting them, working with Michelle Obama, and getting to know her the little that I did.

So how are you going to top that?

Sharon: I got plans. [laughter]

So, Robert, do you have something else you’re working on now that you can’t talk about?

Robert: The veil of secrecy. Yes. We just finished a piece on James Hansen who’s a climatologist and we’re working with Isabel Allende.

What do you do when you’ve finished a work, either of you, and the person who’s the subject of the work says, “Well I really don’t like it that

much.” Or “Can you touch this up?” Or “Can you change that?” Do they ever ask for changes?

Robert: Most of the people who have sat for me I don’t think have seen the paintings, because they’re not part of the . . . We don’t, I don’t actually do commissions, per se. We usually invite somebody to sit for the painting. So, we’ll contact them and ask them if they’re willing to do this. They come, we do the sitting and then eighteen months later it’s done, but we don’t have them in the studio to see it, usually it has a destiny. Many of them are over at the National Portrait Gallery now.

Let’s suppose somebody calls you and says “I’m not the Dali Lama, I’m not Warren Buffett, I have not been on the moon, I’m not president of the United States, but I can afford to pay a very large fee for a really good portrait.” Do you do those kinds of commissions?

Robert: I haven’t yet. It doesn’t mean it will never happen.

Well, you might have some people here, you never know. So just leave your number and I’m sure a lot of people would be happy to call. And what about you, Sharon, do people call you from time to time? And will you take commissions from people that aren’t famous?

Sharon: I work for fees, yes.

And your studio is where, Robert?

Robert: Chelsea, in New York City.

And, Sharon, yours is in Brooklyn, I know. Sharon: Yes, Brooklyn.

And if you had to do your career all over again, would you do anything different from what you’ve done?

Sharon: I think I would’ve stayed in school longer.

Really?

Sharon: I would’ve studied longer. You know, I was very challenged financially, so I had to work and show the paintings and get moving in that way. So, I would’ve stayed in school longer, art school.

What did your family say when you dropped out of Cornell?

Sharon: Take the car, pack up all your bags, and bring the car back when you’re done. [laughter]

Okay, well, it worked out for you.

Sharon: Worked out for me.

And what about you Robert? In your case, do you have any regrets about the career you’ve chosen, and if you could do something different, would you, do something different with your career?

Robert: No. Everything sort of had to happen in the order it did in order for me to get where I am now, and where I am now is exactly where I wanted to be. I don’t mean that to say like as a career, but the work itself is performing the way I want it to perform.

So, when you’re painting, and I’m not a painter obviously, but you’re painting, how do you avoid getting paint on your clothes and everything?

Robert: Really small brushes.

Small brushes. And do you ever paint and run out of the color you need? You have to ask somebody to go down to the drugstore or get it? Where do you get your paints?

Robert: There used to be this fabulous store in New York called New York Central, that was run by a guy named Steve. Steve knew everybody everywhere in the world, of course, and there was a point where he was starting to close and one of the things that happens in the world of course is that in the old days they used to make twenty different versions of one small brush and then the factory goes down through the hands and somebody says we don’t need to make twenty versions of this we only need to make three. So, they started discontinuing things that I used a lot, and Steve would chase around the world and buy every brush that looked like that for me in the world. So, we would buy them by the hundreds, thinking, “Okay, I’m 50 years old, I got twenty more years of this, I’m burning these up at this rate, let’s get as many as we can.” So sometimes this is not as easy as it seems. We have people make brushes, I’ll send them a brush and say, “Can you make this?”

You can’t go into some store and say, “I’m painting a picture of a president of the United States. Can I get a discount on a brush or something?” Doesn’t happen? Doesn’t work that way?

Robert: Ehh No.

And where do you get your paints? Same place he gets his?

Sharon: No, I doubt it. I use a private paint maker who makes their own paint and I’ve been using them for years.

And where do you get the canvases?

Sharon: I don’t work on canvases, I work on panel.

Panel?

Sharon: I work on wood panels. And while you, Robert, seem that you’re really neat and precise with your painting, my house is covered with paint.

At the end of the day, I mean, how do you keep paint from getting on your clothes and everything?

Sharon: I don’t. [laughter]

You don’t try to do that?

Sharon: No. I got it all out of my hair.

All right, we have about two or three minutes, anybody have a question? A burning question about this, and if you want to hire any of these artists, I guess they’re available, perhaps, I don’t know.

Audience: My question is whether you looked at the other portraits in the White House. The new portraits are so entirely different from what has gone before and that really moves that whole collection forward in some startling ways. . . . So, I just wondered whether the two of you ever walked around the White House ahead of time and thought about that context in which the portraits would be hanging.

Sharon: Yes. Aaron Shikler was a model for me. I had seen his paintings and I had been to the White House, and of course there’s books of all of them. But yes, I think I try and incorporate traditional painting values but with abstraction in the color-field and the approach. So, it does move it forward I think.

Robert: I didn’t actually, because all my paintings look the same. We’ve got a goal, and we were aiming for that.

Two portraitists are seen at work on paintings that would become a part of the White House Collection: Douglas Chandor (left) is seen in his New York studio as he captures the likeness of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, 1949. Everett Raymond Kinstler (below) turns toward the camera as he stands before his easel during a sitting with President Gerald R. Ford in Vail, Colorado, c. 1977.

President and Mrs. Barack Obama are joined by the artists of the portraits made of them for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery at an unveiling ceremony, February 12, 2018.

Kehinde Wiley (far left) painted the president’s portrait; Amy Sherald (far right) painted the first lady.

Audience: We all had to wait five years to see these extraordinary paintings but in the interim we had the experience of the great reveal of Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley a year and a half ago [at the National Portrait Gallery], and the enormous response they generated because of who was being represented but also as a consequence of having two exceptional African American artists tell that story, and I wonder, as that moment occurred, how you experienced that and if you felt as if somehow your pieces would be in conversation with or in contrast to the Kehinde and Sherald narratives.

Sharon: Amy and I never saw each other’s work when it was being done, and hers was released I think after I had already finished mine; but I think they are remarkably similar. Other than being of the same person, they are similar in the pose and the way we saw Michelle. So, I think they really complement each other in that way.

Robert: I was very excited about those paintings; it was really fun to see them. I thought they were great addition to the Portrait Gallery. Again, we’re sort of working toward a plan, so I felt a little apart from everybody else’s projects, but it was fun to be in that context.

Audience: First Lady Michelle Obama is absolutely fabulous and . . . I don’t think anything is wrong with, you know, the sleeve-drop. I have just a bit of a question with the color. It’s awesome, but how did you come to just choose the whole color of the landscape?

Sharon: Well, one of the strengths of my paintings is color. I think it’s quite remarkable that so little color is done with portraits today or in the past. I mean color is who we are, how we live, how we breathe. Color tells its own story. So, when I took a tour of the White House, I loved the Red Room, but the light was terrible. So, I started to move the couch, the red couch, into the Blue Room, and she had already picked out the dress, and they work together. It’s intuitive. That’s how I came to it. She looked great.

Well, I want to say thank you both for contributing to our country in this way by giving us these magnificent portraits, which will hang, as we’ve heard, for hundreds of years, no doubt, in the White House. And I hope you’re pleased with the reception you had today. I thought it was an incredible reception not just for President Obama and Mrs. Obama and President Biden and Mrs. Biden but also for you. The works are great, and thank you for your contribution to our country.

THE

PEALES in the White House

America’s First Family of Artists

charles willson peale (1741–1827) is a patriarchal figure in the history of American art. Distinguished for recording the likenesses of individuals instrumental in the nation’s founding and development, he also instructed several of his children and his younger brother James (1749–1831) in the art of painting. The story of the Peale family is a remarkable narrative of artistic sharing in which influence and instruction radiated in all directions over many decades. Parents, siblings, children, cousins, aunts, uncles, and spouses actively taught, influenced, and assisted one another.1 The walls of the White House now display impressive portraits by Charles and his son Rembrandt (1788–1860)

as well as lush still-life pictures by James and by another of Charles’s sons, Rubens (1784–1865). All are the generous gifts of individual Americans, who sought to enrich the presidential mansion with paintings by this artistic family. Works by the Peales first entered the collection in 1962, the year after First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy launched the White House Historical Association and an initiative to showcase, protect, and preserve notable examples of American fine and decorative arts in the White House. In February 1962 she opened the mansion for a televised tour. Watched by millions of Americans, the tour stimulated great interest in collecting and celebrating America’s artistic heritage.2

previous spread

The Peale Family Portrait painted from 1773 to 1809 by Charles Willson Peale, captures ten members of the large artistic family, plus Argus, the family’s dog. Included are two of the artists whose work is now a part of the White House Collection: Charles Willson Peale standing at far left with his pallet and James Peale, seated second from left.

left and opposite Paintings by the Peales are prominently displayed throughout the White House today. Rembrandt Peale’s portrait of George Washington hangs in the Diplomatic Reception Room (left) and his portrait of Thomas Jefferson hangs in the Blue Room (opposite).

CHARLES WILLSON PEALE AS WHITE HOUSE GUEST

Charles Willson Peale was a man of wide-ranging interests, talents, and enormous energy who was ambitious for himself, his family, and the new nation. In Philadelphia in 1784, in the aftermath of the Revolution, he initiated a portrait gallery designed to honor its participants. By 1786, his gallery became part of a museum founded to present an everexpanding and internationally important collection representing the natural sciences, ethnography, and the nation’s ongoing continental explorations. This was also a family endeavor, and the Peales’ communal energy, enthusiasm, and curiosity ultimately shaped the museum into a significant educational resource and place of public recreation, complete with lectures and concerts.3

It is not surprising, therefore, that Charles Peale’s activities led to friendships with many of the most influential and distinguished individuals of his day and that he was entertained at the White House during both the Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe administrations. In June 1804 he facilitated a meeting between Jefferson and the brilliant, world-renowned explorer Alexander von Humboldt. Having just completed the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson was eager to hear about Humboldt’s recent explorations in Central and South America. Peale recalled in his diary, “We had

a very elegant dinner at the Presidents, and what pleased me much, not a single toast was given or called for, or Politiks touched on, but subjects of Natural History, and improvements of the conveniences of Life. Manners of the different nations described, or other agreable conversation animated the whole company.”4 Peale’s second and third visits took place several years later, during the winter of 1818–19 when he traveled from Philadelphia to Washington to update his museum gallery with portraits of individuals he considered “influential characters,” among them President James Monroe. Charles was initially invited by the president for a quiet dinner with “one or two other gentlemen.”5 But an invitation to attend a reception in the handsomely decorated “levee-room” of the White House, hosted by First Lady Elizabeth Monroe a few days later, was remembered as a more impressive affair. The invitation included Charles’s wife, Hannah Moore Peale (1755–1821), and his niece, the miniature painter, Anna Claypoole Peale (1791–1878), who was also painting the president.6 The mansion, burned by the British during the War of 1812, was now rebuilt and newly decorated. Charles recorded the glittering scene in his diary, describing the space as

an Oval richly furnished. The Carpit cost 2000$ the Chairs & settee’s of Crimson silk with Gilt frames—Chandelier & Gerandoles of a splendid finish and all the other furniture of appropriate elegance. . . . Mrs. Monroes desired Mrs. Peale to sett by her, and during the whole of the evening paid marked attention to her—We were desired to come early that is at 7 O’clock—therefore we had the pleasure of [seeing] the company enter. . . . Amongst them I meet several of Old acquaintance some that I had known full 40 years. Coffee, tea and a variety of Cakes passed round to the Company, after wards, Punch Wine & Scrub or lemonade, Cakes &c.7

Although Peale’s portrait of Monroe does not hang in the White House today,8 one of the artist’s earliest portraits of the nation’s first president does.

PORTRAITS BY THE PEALES

George Washington never lived in the White House, but he is represented on its walls with portraits by both Charles and his son, Rembrandt. Two significantly different works, separated by more

Peale presents Washington as commander in chief of the Continental Army in 1776, early in the Revolutionary War. He is seen against a smokefilled background following his successful siege of the city of Boston.

than seventy years, Charles’s portrait represents Washington shortly after his first military victory of the Revolution, while Rembrandt’s work is a posthumous, mid-nineteenth-century memorial to Washington’s place in American history.

Few artists had an opportunity to paint the first president directly from life, but Charles’s early acquaintance with Washington and their ongoing cordial relationship resulted in seven distinct portraits painted in 1772, 1776, 1777, 1779, 1783, 1787, and 1795. Although the first of these was a private commission from Martha Washington prior to the Revolution, the others represent Washington at distinct moments in his career as military leader and statesman.9 Charles’s portrait, now in the White House, is his own close replica of the portrait he painted in Philadelphia in late May 1776, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.10 Representing Washington in his role as commander in chief of the Continental Army, he is seen against a smoldering landscape of war that documents his first great military success of the Revolution at Dorchester Heights, after the siege of Boston and the evacuation of British forces. Washington had been requested to travel to Philadelphia for a conference on military operations with the Continental Congress in advance of an impending attack on the

city. But Peale’s portrait was a private commission that came from the president of the Congress, John Hancock, who hoped to gain Washington’s favor. The portrait is indebted to the traditions of British and European portraiture of triumphant military leaders that Charles knew through imported prints, as well as through his direct experience of such pictures during his two years of study in the London studio of the American-born artist, Benjamin West (1738–1820).11 As a picture documenting an exceptionally newsworthy event in the ongoing American Revolution, Peale’s image captured not just American but also international interest. By 1777 the portrait was engraved and distributed along with its companion portrait of Martha Washington, also commissioned by Hancock but now lost.12 Although Peale made multiple replicas of some of his other Washington life portraits, the White House portrait appears to be his only fullscale replica of his 1776 portrait. Documenting its completion in his diary on November 25, 1776, Charles noted that he painted it for “a French gentleman.”13

Immediately after the Revolution, Charles, his brother James, and his nephew Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822) would benefit from ongoing requests for replicas or variations of Charles’s original life

Rembrandt Peale’s “porthole” portrait of George Washington hangs above the fireplace in the Oval Office during the presidency of Barack Obama.

portraits of the new nation’s hero. But, over time, the popularity of the Peales’ Washington portraits was replaced by Gilbert Stuart’s 1796 likeness of the first president, now enshrined on the dollar bill.14

However, in February 1824, Charles’s son, Rembrandt Peale, who was known for his dramatic portraiture and ambitious exhibition pictures, asserted his claim to powerfully reconnect the Peale name with Washington by arranging for the display of his recently completed monumentally scaled Washington portrait in the U.S. Capitol. An impressive work, it was formally acquired for the Senate’s collection in 1832, on the centennial of Washington’s birth, and today hangs in the Old Senate Chamber.15 Unlike Rembrandt’s more naturalistic early portraiture, this portrait displays the sculptural neoclassical style he adopted after his visits to Paris between 1808 and 1810. It was a style well suited for creating a posthumous, idealized portrait designed to project Washington’s celebrated heroic strength of character and resolve. Painted long after Washington’s death, Rembrandt recalled that he created the portrait by studying the life portrait he had painted in 1795, at age 17, seated next to his father, as well as his father’s final life portrait of Washington, painted at the same time, and the portrait bust of Washington created

by the French neoclassical sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828).16 More than a mere likeness, Rembrandt’s Washington was an icon enshrined for the ages in an honorific oval with the words, “Patriae Pater” (Father of His Country) seemingly chiseled into the stonework below him. Peale made two large replicas of this work, successfully displaying one in Europe. His public displays of the picture were typically accompanied by pamphlets explaining and promoting the image.17

In the mid-1840s Rembrandt Peale began to paint smaller-scale versions for the homes or offices of patriotic citizens. While his original Senate portrait measures 71 × 53 inches, the smaller versions, like the one in the White House Collection, measure only 36 × 29 inches. Rembrandt referred to this portrait type as the “Standard National Likeness,” a term suggesting his Washington image replaced all others. But over time these portraits came to be referred to differently, as evidenced in the letter written by its donor, Katherine F. Howells, to First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1962.

My family and I watched with great interest your tour of the White House on television a week ago. . . . It occurred to me that you might be interested in having another portrait of Washington. This one is called the “Porthole

Washington” and has belonged to my family for many years. . . . Of course, I do not know whether there is any space available in the White House for another portrait, but I thought I would write on the chance. If you and your Committee are interested, I would be very happy and honored to have the portrait become a permanent part of the White House Collection.18

The portrait was readily accepted and was seen in 1970 on the Sixty Minutes program, “Upstairs at the White House” with Tricia Nixon, who described it as a family favorite.19 Her family was not alone in their appreciation of the portrait, since it continued to hang in the Oval Office for decades and is currently in the Diplomatic Reception Room.

Like his larger picture, Rembrandt Peale’s smaller versions of his Washington portrait exhibit a luminous, cloud-filled background, although the elaborate stonework is reduced to a simple oval. Washington is typically shown in military uniform, although a small number of these portraits represent him in a formal black coat and white neckpiece.20 Despite their smaller size, these domestically scaled versions project a strong sense of Washington’s presence. His glowing face, intense blue eyes, and silver gray hair create a stunningly illusionistic effect that is balanced by the bold design and vivid color of his uniform.

Before his death in 1860 Rembrandt

documented painting seventy-nine such portraits. However, the demand for them continued late into the century, providing commissions for copies of this portrait type by three accomplished women artists of the Peale family, Rembrandt’s second wife Harriet Cany Peale (1800–1869) and his nieces and students, Mary Jane Peale (1827–1902) and Anna Sellers (1824–1905).21

It is hard to envision a starker contrast in Rembrandt Peale’s extensive body of portraiture than that presented by his conceptualized “Standard National Likeness” of Washington and his considerably earlier, naturalistic life portrait of Thomas Jefferson. Peale was just 22 years old when he painted the 57-year-old Jefferson between late December 1799 and mid-May 1800, in Philadelphia. This small, vibrant portrait became Jefferson’s campaign image in the presidential election of 1800. Direct, dignified, and unpretentious, this genial likeness seemed to project. Jefferson’s campaign

slogan, “The People’s Friend.” As Albert Bush Brown noted, it is “among the earliest and most penetrating likenesses of Jefferson” and “unrivaled in having played a more significant iconographic role during Jefferson’s lifetime than any other portrait. Shortly after its completion it became the prototype of a widely distributed series of American and European engravings” and “Peale’s arresting portrait thus served as an important and convincing item of political propaganda.”22

slogan, “The People’s Friend.” As Albert Bush Brown noted, it is “among the earliest and most penetrating likenesses of Jefferson” and “unrivaled in having played a more significant iconographic role during Jefferson’s lifetime than any other portrait. Shortly after its completion it became the prototype of a widely distributed series of American and European engravings” and “Peale’s arresting portrait thus served as an important and convincing item of political propaganda.”22

Jefferson had the strongest links to the Peales of any president. He and Charles shared an interest in scientific research and the study of natural science, especially as it related to the growth and identity of the new nation.23 Both were members of the American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin, and, while serving in the Washington administration, Jefferson was head of the board of Peale’s Museum. Jefferson found

Jefferson had the strongest links to the Peales of any president. He and Charles shared an interest in scientific research and the study of natural science, especially as it related to the growth and identity of the new nation.23 Both were members of the American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin, and, while serving in the Washington administration, Jefferson was head of the board of Peale’s Museum. Jefferson found

these affiliations a valuable distraction and wrote his daughter that “Politics are such a torment that I would advise everyone I love not to mix with them. I have changed my circle . . . associating entirely with the class of science, of whom there is a valuable society here.”24 Apparently pleased with Rembrandt’s portrait, Jefferson requested a copy for a friend.25

these affiliations a valuable distraction and wrote his daughter that “Politics are such a torment that I would advise everyone I love not to mix with them. I have changed my circle . . . associating entirely with the class of science, of whom there is a valuable society here.”24 Apparently pleased with Rembrandt’s portrait, Jefferson requested a copy for a friend.25

Rembrandt Peale’s lively portrait of Jefferson did not go unnoticed by his father, who admired its style and execution and sought to emulate it in portraits he painted a few years later. His portrait of his friend Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the talented architect and engineer who shared Charles’s interest in new technologies to improve life, is one such example. Appointed surveyor of public buildings by Jefferson in 1803, Latrobe made many contributions to the new capital, including his work on the Capitol Building, St. John’s Church, the Decatur House on Lafayette Square, the East and West Terraces of the White House, and the furnishings of James Madison’s State Rooms. Also the architect of the Baltimore Cathedral, Latrobe was appointed chief engineer for the U.S. Navy and created a design for Peale’s Philadelphia Museum that, unfortunately, was never executed. Charles Peale’s portrait conveys Latrobe’s energetic and inquisitive personality through the slight inclination of his head and his intense, direct gaze that meets the viewer. The portrait’s provenance establishes its inclusion in the gallery of Peale’s Philadelphia

Rembrandt Peale’s lively portrait of Jefferson did not go unnoticed by his father, who admired its style and execution and sought to emulate it in portraits he painted a few years later. His portrait of his friend Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the talented architect and engineer who shared Charles’s interest in new technologies to improve life, is one such example. Appointed surveyor of public buildings by Jefferson in 1803, Latrobe made many contributions to the new capital, including his work on the Capitol Building, St. John’s Church, the Decatur House on Lafayette Square, the East and West Terraces of the White House, and the furnishings of James Madison’s State Rooms. Also the architect of the Baltimore Cathedral, Latrobe was appointed chief engineer for the U.S. Navy and created a design for Peale’s Philadelphia Museum that, unfortunately, was never executed. Charles Peale’s portrait conveys Latrobe’s energetic and inquisitive personality through the slight inclination of his head and his intense, direct gaze that meets the viewer. The portrait’s provenance establishes its inclusion in the gallery of Peale’s Philadelphia

Museum, and its simple oval format is typical of many of the portraits painted specifically for the museum’s collection. In a letter to a friend in 1804, Charles noted his successful reengagement with portrait painting after several years of focusing only on museum business.26 Charles would continue to look to his son Rembrandt for artistic inspiration and guidance, and he wrote to Latrobe in 1805 that “Rembrandt has opened my Eyes to some important methods of producing fine pictures.”27

THE AMERICAN STILL-LIFE TRADITION

James Peale and his nephew Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), who were also instructed in the art of painting by Charles Willson Peale, are the acknowledged founders of the American tradition of still-life painting. But unlike Raphaelle’s spare, carefully calibrated,

and often smaller and mysterious works, James’s pictures are straightforward presentations of the celebrated bounty of American nature.28 After Charles returned from studying art in London, James became his pupil and then his studio assistant before launching an independent career. Initially dedicating himself to watercolor on ivory miniatures, oil portraiture, and small historical compositions, in the early 1820s he further distinguished himself by turning to still-life subjects, a genre of painting his brother rarely practiced.29

James’s still-life pictures may, in part, reflect Charles’s experiment in farming and gardening between 1810 and 1820 on his Germantown farm, Belfield.30 It was an endeavor detailed in his correspondence with Jefferson, then retired to Monticello, and they continually shared information and “best practices” for yielding

better crops and taking care of the land.

The two examples of James’s still-life pictures now in the White House Collection present his typical motifs and methods of composition. Both contain pieces of fine porcelain surrounded by an abundance of fruit horizontally displayed across a simple neutral tabletop and background. The reticulated bowl seen in his Fruit in a Chinese Export Basket appears in several of his compositions, as well as in those by other family members who copied James’s works, including Rubens, Mary Jane, and Harriet Cany Peale and Anna Sellers. Here, however, it is inscribed with James’s signature and a date, perhaps a genteel form of advertising. The motif of a peach or apple tentatively balancing on a narrow rim is one James often employed and also frequently copied by other Peale artists. It not only defines the shape and volume of the

individual fruit; it also suggests the possibility of motion. In both this picture and in his Grapes and Apples James includes his typical diagonal branch with leaves that sweep across the background and draw the viewer’s gaze through the picture. Not all the fruits are perfect, a fact reflecting his assimilation of the European tradition of still-life painting in which the passage of time, or transience of life, is conveyed through a fruit’s varied imperfections or potential decay. In both works the grapes are characteristically luminous, but it is James’s precision of execution, the delicacy and elegance of his outline, and the ease with which he establishes a fluid serpentine movement throughout his compositions that characterize his most exceptional work.

Charles would have been surprised to learn that twenty-five years after his death his son Rubens joined the family’s artistic enterprise. Rubens Peale

did not begin to paint until the last decade of his life, at age 71. He had dedicated his earlier years to working in and then managing the Peale museums in Philadelphia, Baltimore and, finally, New York City. When his New York museum, founded in 1825, failed following the financial Panic of 1837, he retired to his wife’s family farm in Schuylkill Haven, Pennsylvania, where he put his expertise in gardening and farming to good use. Here, in 1855, under the instruction and, sometimes, with the assistance of his daughter, Mary Jane, who had studied with his brother, Rembrandt, Rubens began to paint. Creating a small but interesting group of pictures, he chose to depict fruits and flowers, subjects that intersected with his love of gardening and farming. Focused and diligent, he recorded the dates of his pictures, their subjects, and the individuals for whom they were painted. Of his 147 recorded works, 34 were documented as gifts for family and friends. These included “copies” and variations of pictures by Raphaelle, James, and Mary Jane, as well as a few exuberant original compositions.31 Rubens’s Still Life with Fruit presents a selection of items from the compositions of both James and Raphaelle but it also represents his own distinct, less illusionistic style. Clearly enjoying his colorful selection of grapes, white watermelon, and peaches stacked in a metallic serving dish, Rubens unites their curves and angles to create a bold and active composition, well attuned to contemporary taste. The intricate compositions, high finish, and detail of James’s still-life pictures are clearly different from the less polished and less technically sophisticated style of Rubens. Yet together they perfectly represent two vital artistic traditions alive in nineteenth-century America—the academic and the vernacular.

Although the Peales learned from one another, their essential bodies of work were distinct and personal, and the works of Charles, Rembrandt, James, and Rubens are clearly stylistically diverse. I hope that more of the art of this gifted American family will be donated to the White House to further diversify its remarkable collection. A precise and brilliant still-life picture by Raphaelle Peale, a bold oil portrait by Sarah Miriam Peale (1800–1885), or a delicate miniature on ivory portrait by Anna Claypoole Peale all would be perfect additions.

notes

1. Charles married three times and had children by his first two wives, Rachel Brewer Peale (1744–1790) and Elizabeth DePeyster Peale (1765–1804). He had no children by his third wife, Hannah Moore Peale (1755–1821).

2. Mary Jo Binker, “Jacqueline Kennedy’s Televised Tour of the White House,” White House History Quarterly, no. 67 (2022): 70–83.

3. Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art (New York: W. W. Norton, 1980). This publication remains the best overview of the institution’s history. Although many of the portraits have been dispersed, there is a representative collection of them on permanent display in the historic Second Bank in Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia. For a catalog of that collection, see Doris Devine Fanelli, History of the Portraits Collection, Independence National Historical Park and Catalogue of the Collection, ed. Karie Diethorne, introd. John C. Milley (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2001). The painting collection of Peale’s Philadelphia Museum was sold at auction in 1854. The other contents had been auctioned earlier in 1848. For the paintings, see Peale’s Museum Gallery of Oil Paintings: Catalogue of the National Portrait and Historical Gallery, Illustrative of American History, Formerly Belonging to Peale’s Museum, Philadelphia (Philadelphia: M. Thomas and Sons Auctioneers, 1854).

4. Charles Willson Peale, diary, first week of July 1804, in The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, ed. Lillian B. Miller et al., 5 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), 2, pt. 2: 693. Charles Peale painted a portrait of Humboldt in 1804 for the Peale Museum collection, now in the collection of the College of Physicians, Philadelphia. Charles’s son Rembrandt painted Humboldt again in Paris in 1810. “Original Letter from Paris, Addressed by Rembrandt Peale to Charles Willson Peale and Rubens Peale,” PortFolio 4, no. 3 (September 1810): 278–79. This portrait is in a private collection but also was once in the collection of the Peale Museum, Philadelphia.

5. Charles Willson Peale, diary, November 12, 1818, in Selected Papers of Peale, ed. Miller et al., 3:616, 620, fig. 53.

6. Anna Claypoole Peale was the daughter of James Peale. She and her sister, Sarah Miriam Peale (1800–1885) were two of the earliest successful professional American women artists. Sarah painted oil portraits and still lifes.

7. Charles Willson Peale, diary, November 24, 1818, Selected Papers of Peale, ed. Miller et al., 3:623.

8. Peale’s portrait of President James Monroe (1818, oil on canvas, 29 × 23 inches), is in the Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site, managed by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

9. The portrait of 1772 was commissioned as a pendant to Martha Washington’s earlier portrait by John Wollaston Jr. (1705–after 1775). Washington wears his uniform from the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War. These portraits are now in the collection of the Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia. Peale painted several Washington family portrait miniatures at this time and would continue to paint miniatures of Washington throughout the Revolution. See Carol Eaton Soltis, The Art of the Peales in the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Adaptations and Innovations (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2017), 102–03. The White House Collection includes copies of the Peale and Wollaston portraits painted by Ernst Fisher, c. 1850–52 for Robert E. Lee and his wife; they were carried with them to military quarters and displayed and Arlington House.

10. Charles Coleman Sellers, “Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 42, pt. 1 (1952): 220–21. See also the catalog entry for Peale’s portrait of George Washington on the Brooklyn Museum’s website, www.brooklynmuseum.org.

11. Peale returned from London well versed in the traditions of European portraiture. For Peale’s experience in London, see Soltis, Art of the Peales, 13–33.

12. Sellers, “Portraits and Miniatures,” 242, no. 953. For updated information on the prints of Peale’s 1776 portraits, see Wendy C. Wick, George Washington, An American Icon: The EighteenthCentury Graphic Portraits (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service for the National Portrait Gallery, 1982), 8, 9; Soltis, Art of the Peales, 103 (ill.). An engraving of Lady Washington by Joseph Hiller after a painting by Charles Willson Peale is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art; see the museum’s website, https://philamuseum.org.

13. For his progress on the oil portrait for “a French gentleman,” see Charles Willson Peale, diary, November 9–25, 1776, in Selected Papers of Peale, ed. Miller et al., 1:203–06. The portrait was completed on November 25, 1776. A portrait miniature taken from the 1776 portrait is now at Mount Vernon.

14. Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington (Athenaeum Portrait), 1796, is jointly owned by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. See the catalog entry at the National Portrait Gallery website, https://npg.si.edu.

15. The United States Senate website provides a detailed history of the picture: www.senate.gov/artandhistory. See also Lillian B. Miller and Carol Eaton Hevner, In Pursuit of Fame: Rembrandt Peale, 1778–1860 (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1992), 142–47, 279–82.

16. Rembrandt Peale’s 1795 portrait of George Washington is in the collection of the Philadelphia History Museum, Drexel University, Philadelphia. Charles Willson Peale’s portrait is in the New-York Historical Society. For Houdon’s bust, see “JeanAntoine Houdon,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon website, www.mountvernon.org.

17. Two well documented copies of the large portrait exist. One is in a private collection and the other in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. In 1805 Peale was a founding member of the academy, which remains a notable art school and museum of American historic and contemporary art.

18. Katherine F. Howells to Mrs. John F. Kennedy, April 1, 1962, Office of the Curator, The White House.

19. See Leslie F. Calderone, “Upstairs at the White House with Tricia Nixon: The Making of the 60 Minutes Televised Tour,” White House History Quarterly no. 67 (2022): 84–95. The “Upstairs at the White House” segment of Sixty Minutes is available on YouTube, www.youtube.com.

20. Carol Eaton Hevner, “The Washington Copies,” in Rembrandt Peale: A Life in the Arts (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1985), 88–89, see also 66, 86, 90–91.

21. Rembrandt Peale married Harriet Cany in 1840. Mary Jane was the daughter of Rembrandt’s brother Rubens and Anna a daughter of his sister Sophonisba Peale Sellers (1786–1859).

22. Alfred Bush Brown, “The Life Portrait of Thomas Jefferson,” Jefferson and the Arts: An Extended View, ed. William Howard Adams (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 57. The earliest engraved copies of the portrait are by David Edwin and Cornelius Tiebout. Advertisements appeared in the Philadelphia Aurora, September 8. 1800, and February 20 and 26, 1801. The portrait appears to have remained with Rembrandt Peale as part of the collection of his Baltimore Museum, which opened to the public in 1814. In 1854 the painting was sold to Charles Getz from the remains of that museum. It was then purchased by Charles J. M. Eaton, with whom it remained until his death in 1893, when it was presented it to Baltimore’s Peabody Institute. Unlocated for many years, it was identified in 1959 as the portrait in the collection of the Peabody Institute and purchased by Paul Mellon (c. 1961), who presented to the White House in 1962.

23. Charles Peale also painted Jefferson. Fanelli, History of the Portraits Collection: Independence National Historical Park and Catalogue of the Collection, ed. Diethorne, introd. Milley, 186.

24. Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, February 11, 1800, quoted in Edward Dumbauld, “Thomas Jefferson and Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania History 5, no. 3 (1938): 161.

25. Thomas Jefferson to Charles Willson Peale, February 21, 1801, in Selected Papers of Peale, ed. Miller et al., 2, pt. 1: 297–98; Rembrandt Peale to Thomas Jefferson, March 24, 1801,

ibid., 305. The location of this copy has never been determined. In 1805, Rembrandt painted Jefferson for the Philadelphia Museum’s portrait gallery. The painting shows the president significantly aged. It was purchased by Thomas Bryan in the 1854 sale of the painting collection of Peale’s Philadelphia Museum. He later donated it to the New-York Historical Society, where it remains.

26. Charles Willson Peale to Mrs. Nathaniel Ramsay, Museum, September 7, 1804, in ibid., 2, pt. 2: 752; Sellers, “Portraits and Miniatures,” 122.

27. Charles Willson Peale to Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Philadelphia, July 21, 1805, in Selected Papers of Peale, ed. Miller et al., 2, pt. 2: 869. See also Carol Eaton Hevner, “Lessons from a Dutiful Son, Rembrandt Peale’s Artistic Influence on His Father, Charles Willson Peale,” in New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale: A 250th Anniversary Celebration, ed. Lillian B. Miller and David C. Ward (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press for the Smithsonian Institution, 1991), 103–17. Rembrandt Peale would paint Latrobe a decade later. For this portrait, see the catalog entry on the Maryland Center for History and Culture website, www.mdhistory. org.

28. For bibliography for Raphaelle, as well as a comparison of works by Raphaelle and James, see Soltis, Art of the Peales, 224–32, 321. For numerous illustrations of Raphaelle’s still-life pictures, see Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. et al., Raphaelle Peale Still Lifes (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1988).

29. See Linda Crocker Simmons, “James Peale: Out of the Shadows,” in The Peale Family: Creation of a Legacy, 1770–1870, ed. Lillian B. Miller (New York: Abbeville Press in association with the Trust for Museum Exhibitions and the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1996), 203–19; Soltis, Art of the Peales, 107–112, 219–222, 232–37.

30. For Peale and Belfield, see Therese O’Malley, “Charles Willson Peale’s Belfield: Its Place in Garden History,” in New Perspectives on Charles Willson Peale, ed. Miller and Ward, 267–82; Julia Sienkewicz, “Citizenship by Design: Art and Identity in the Early Republic” (PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2009), 184–256; Soltis, Art of the Peales, 212–19.

31. For Rubens and his list of pictures, see Charles Coleman Sellers, “A Painter’s Decade,” Art Quarterly 23, no. 2 (Summer 1960): 139–52. See also Paul D. Schweizer, “The Art of Rubens Peale, 1855–1865,” in Peale Family: Creation of a Legacy, ed. Miller, 168–85.

When HARRY MET Pablo

The Strange True Story of the Day President Harry Truman Spent with Artist Pablo Picasso

MATTHEW ALGEO

when art historian alfred barr learned that Harry and Bess Truman would be going on a Mediterranean cruise in the summer of 1958, he saw a rare chance to get the former haberdasher from Independence, Missouri, interested in modern art. As the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Barr was one of the movement’s most enthusiastic evangelists in the United States. But Truman had proved an especially tough nut to crack. In May 1947, Barr sent the then-president a book about modern art. The title has been lost to history—perhaps it was the latest edition of Barr’s What Is Modern Painting?—but Truman responded with a letter that was characteristically blunt.

I appreciated very much your note of the second enclosing me a book on modern painting. It is exceedingly interesting. I still get in almost the same frame of mind as after I have a nightmare when I look at these paintings.

Some of them are all right—at least you can tell what the painter had in mind. Some of them are really the “ham and egg” style.

I do appreciate highly your interest in trying to convert me to the modern viewpoint in art but I just can’t appreciate it, much to my regret.1

Truman preferred the Old Masters to the avantgarde. “I am very much interested in beautiful things,” he wrote in 1953. “Pictures, Mona Lisa, the Merchant, the Laughing Cavalier, Turner’s landscapes, Remington’s Westerns and dozens of others like them. I dislike Picasso, and all the moderns— they are lousy. Any kid can take an egg and a piece of ham and make more understandable pictures.”2

But Alfred Barr never stopped trying to convert Truman, even after he left the White House, and when Barr found out the Trumans would be stopping in Cannes on their cruise, he decided to take another shot. Cannes just happened to be where Pablo Picasso lived. Who better to win Truman over to the wonders of modern art than the man who practically invented it? Barr also believed a meeting between the man who painted Guernica and the man who authorized the use of nuclear weapons against civilians would be of symbolic importance. Conservative Republicans in Congress had been attacking modern art for nearly a decade.

previous spread and left President

hand outside of the artist’s ceramic studio at Vallauris, France, 1958. The unlikely meeting had been arranged by art historian Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art (left with Picasso’s Guernica), in the hope that the former president, who had written that modern art gave him nightmares, would actually come to appreciate the style.

right

Representative George Dondero of Michigan, an acolyte of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, claimed modern art was “Communist-inspired and Communist-connected” and had “one common, boasted goal—the destruction of our cultural tradition and priceless heritage.” Dondero reserved special contempt for Picasso, whom he described as “the hero of all the crackpots in so-called modern art” and “the ‘gage’ by which American modernists may measure their own radical worth.”3

Alfred Barr hoped that, by shaking Picasso’s hand, Harry Truman would send a message, not just to reactionary Republicans like George Dondero but to the whole world: modern art was not evil. And although Truman hated modern art, Barr knew he hated the people who wanted to censor it even more. Harry Truman may have been a philistine but he was certainly no fascist. “We are not going to try to control what our people read and say and think,” he declared in a 1950 speech. “We are not going to turn the United States into a right-wing totalitarian country in order to deal with a left-wing totalitarian threat.”4

Barr just had to figure out a way to bring together the straight-talking politician from Missouri and the Cubist painter from Málaga, two men whose tastes in politics, art, and life were diametrically opposed and whose personalities were nearly as big as their influence on the twentieth century.

By early 1958, the Trumans had been out of the White House for five years and, for the first time in their twenty-seven years of marriage, were

enjoying some financial security. A book deal had netted Harry about $200,000 (nearly $2 million today), and a presidential pension bill that Congress was considering offered the prospect of permanent income.5 So the Trumans decided to splurge a little, and, with their friends Samuel and Dorothy Rosenman, they booked a cruise to Europe. Sam Rosenman was a lawyer and former New York Supreme Court justice who had been one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s most trusted advisers and his principal speechwriter. It was Rosenman, in fact, who coined the phrase “New Deal.”6 When Truman became president, he asked Rosenman to stay on as White House counsel, and the two men formed a friendship that fully flowered after they were freed from the constraining protocols of the Oval Office. In retirement, Harry and Sam and their wives, Bess and Dorothy, formed a convivial quartet who enjoyed spending time together.

Sailing from New York in late May on the appropriately named American Export Lines cruise ship Independence, the two couples would spend three weeks touring the Mediterranean coasts of Italy and France. Unlike a trip to Europe that the Trumans had taken two years earlier, which was filled with official engagements and speeches, this one would be a strictly private affair—just two older couples (Harry and Bess were 74 and 73, Sam and Dorothy 62 and 58) enjoying a leisurely vacation.

Shortly before the couples set sail, Alfred Barr made arrangements for the Truman-Picasso summit. The go-between was probably Ralph Colin,