WHITE HOUSE HISTORY Quarterly

Board of Directors

chairman

Frederick J. Ryan Jr.

vice chairman and treasurer

John F. W. Rogers

secretary

James I. McDaniel

president

Stewart D. McLaurin

John T. Behrendt, Michael Beschloss, Teresa Carlson, Jean Case, Janet A. Howard, Knight Kiplinger, Martha Joynt Kumar, Anita McBride, Robert M. McGee, Ann Stock, Ben C. Sutton Jr., Tina Tchen, Gregory W. Wendt

liaison

David Vela

ex officio

Lonnie G. Bunch III, Kaywin Feldman, David S. Ferriero, Katherine Malone France, Carla Hayden

directors emeriti

John H. Dalton, Nancy M. Folger, Elise K. Kirk, Harry G. Robinson III, Gail Berry West

white house history quarterly

founding editor

William Seale (1939–2019)

editor

Marcia Mallet Anderson

editorial and production director

Lauren McGwin

senior editorial and production manager

Kristen Hunter Mason

editorial and production manager

Elyse Werling

editorial assistant

Rebecca Durgin

consulting editor

Ann Hofstra Grogg

consulting design

Pentagram

editorial advisory

Bill Barker

Matthew Costello

Mac Keith Griswold

Scott Harris

Jessie Kratz

Joel Kelmerhor

Rebecca Roberts

Lydia Barker Tederick

Bruce White

the editor wishes to thank The Office of the Curator, The White House

susan ford bales is the youngest child of President and Mrs. Gerald R. Ford. She is the Ship’s Sponsor of the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), and serves as a trustee of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation, the President Gerald R. Ford Historical Legacy Trust, and the Elizabeth B. Ford Charitable Trust.

mary jo binker is consulting editor of the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. She is also the editor of two books: If You Ask Me: Essential Advice from Eleanor Roosevelt and What Are We For? The Words and Ideals of Eleanor Roosevelt. Her other publications include a book on military women in the Korean War era, an oral history guidebook, and articles on presidents, first ladies, African American history, and the Civil War. She is a regular contributor to White House History Quarterly.

richard s. hussey is a retired distinguished research professor in the College of Agriculture at the University of Georgia in Athens. the white house historical association

clifford krainik is an independent historian, dealer, and appraiser of nineteenth-century photography who has written extensively on the subject. He co-authored Union Cases: A Collector’s Guide to the Art of America’s First Plastics

jeffrey r. parsons is a retired professor of anthropology and emeritus curator of Latin American archaeology at the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, University of Michigan.

kenneth t. walsh is a former president of the White House Correspondents’ Association and a contributing writer to U.S. News & World Report, where he served as White House correspondent for three decades starting in 1986. He is an adjunct professorial lecturer at the American University School of Communication, and he has written nine books on the presidency, including Ultimate Insiders: White House Photographers and How They Shape History and Air Force One: A History of the Presidents and Their Planes. His most recent book is Presidential Leadership in Crisis.

Wind-blown spectators are ready to capture photographs and video of Marine One as it lands on the South Lawn returning President George W. Bush to the White House, April 22, 2004.

4 FOREWORD

marcia mallet anderson 6

PRIVILEGED ACCESS: The Earliest Photographs of White House Interiors

clifford krainik 18

“THE WHITE HOUSE IN 1889: The Discovery of Walter Hussey’s Glass-Plate Negatives

richard s. hussey

THE ULTIMATE INSIDERS: White House Chief Photographers

kenneth t. walsh 60

A PHOTOGRAPHER REMEMBERS : My Brief Career as a Washington, D.C. Street Photographer in the 1950s

jeffrey r. parso ns

68

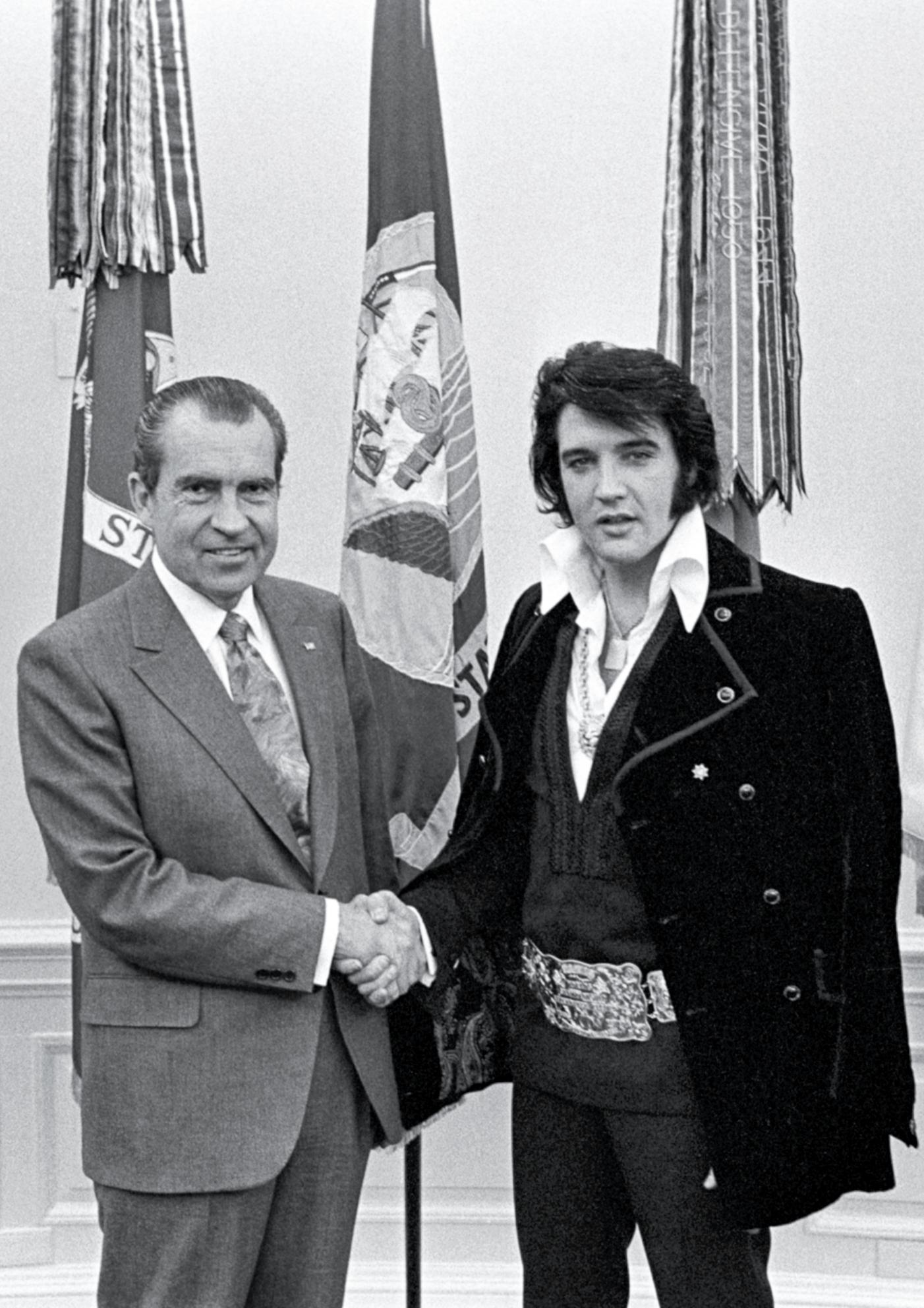

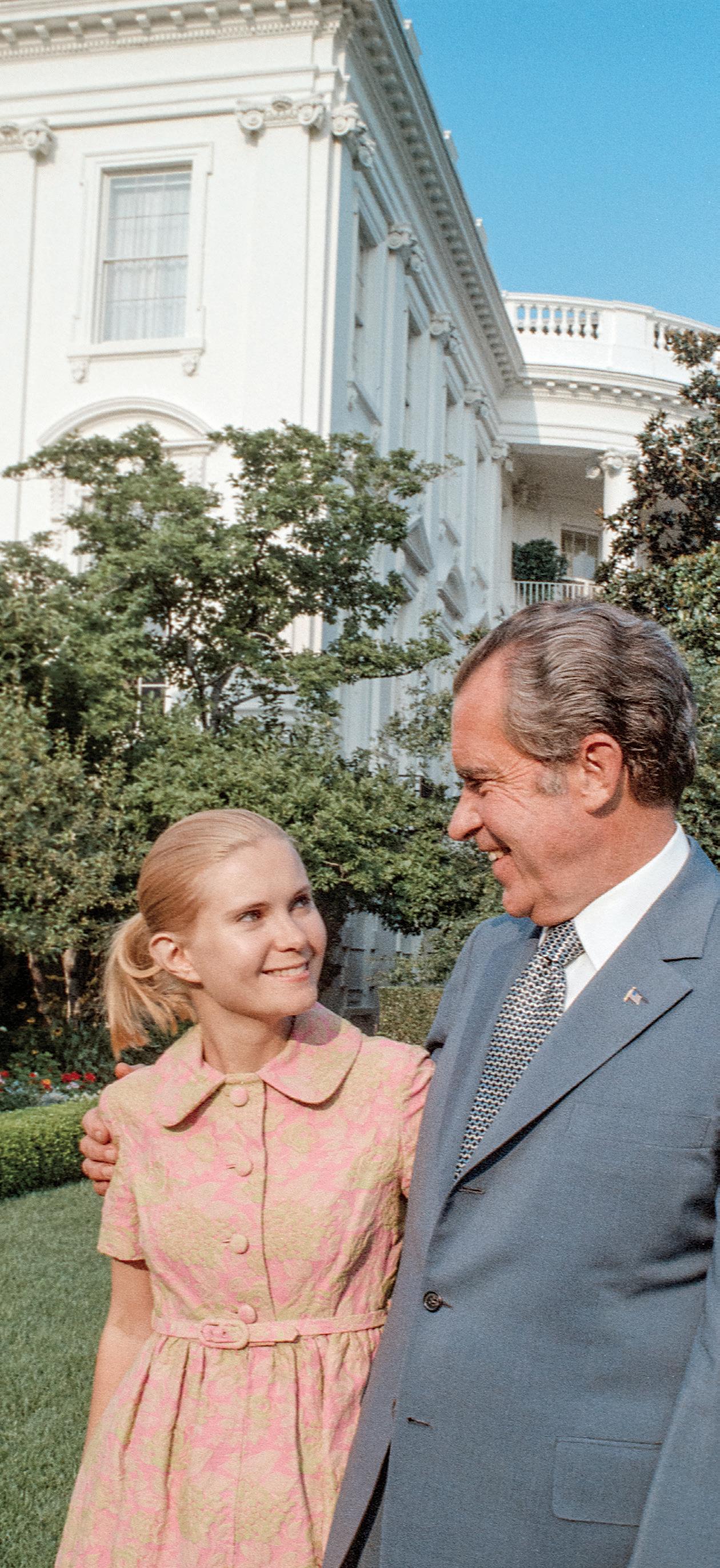

WRITING WITH PHOTOGRAPHS: Oliver Atkins Documents the Nixon Presidency mary jo binker 82

PHOTOGRAPHING THE WHITE HOUSE: A First Daughter’s Perspective susan ford bales 99

MEMORIES PRESERVED Through White House Photographs

marcia mallet anderson 108

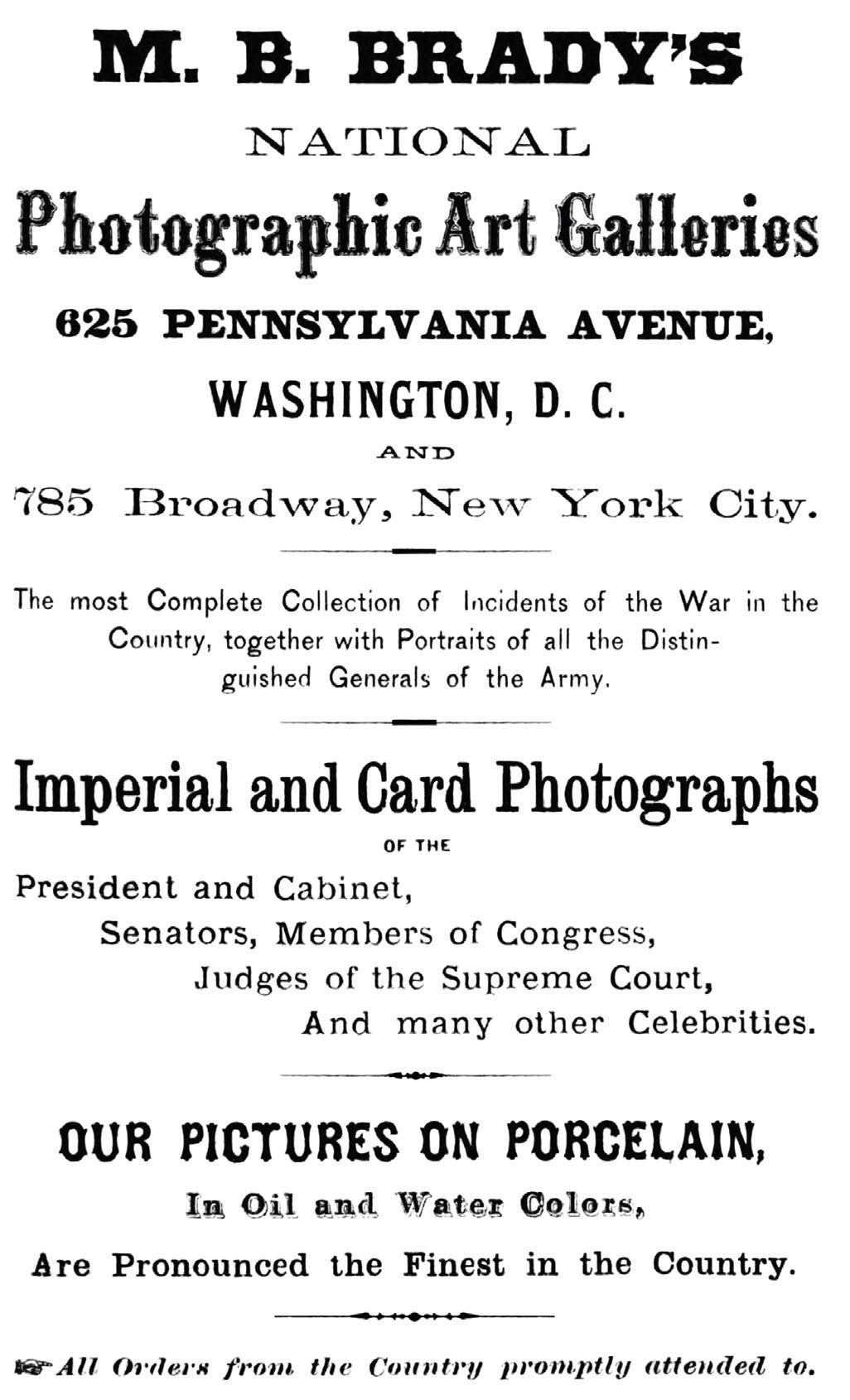

PRESIDENTIAL SITES QUARTERLY FEATURE Mathew Brady’s Photography Studio elyse werling 114

Reflections ON HISTORY OLD AND NEW stewart d. m c laurin

it is hard to imagine the Quarterly without photographs.

Ever since John Plumbe Jr. captured the first known photograph of the White House in 1846, professional and amateur photographers alike have focused their lenses on scenes from every chapter in the life and evolution of the house. As we create the layouts for each issue of the Quarterly, millions of architectural, landscape, fine art, portrait, and documentary photographs are available to us—from files of the Library of Congress, National Archives, presidential sites, museums, private and commercial collections, and the Association’s own digital library. With the assistance of the White House Office of the Curator, we are also able to commission new photography. With no shortage of pictures to choose from, our challenge in designing the Quarterly is often to find the perfect images among thousands that can bring an author’s words to life.

Our favorite photographs are the discoveries, the never-before-published images, which, like puzzle pieces, help complete the bigger picture of White House history. Many of these have been discovered and shared with the Quarterly by the historian Clifford Krainik. With this issue, he takes us back to the 1840s to see the first photographs known to have been made inside the White House, and to the early 1860s to see the earliest published stereoviews of State Rooms.

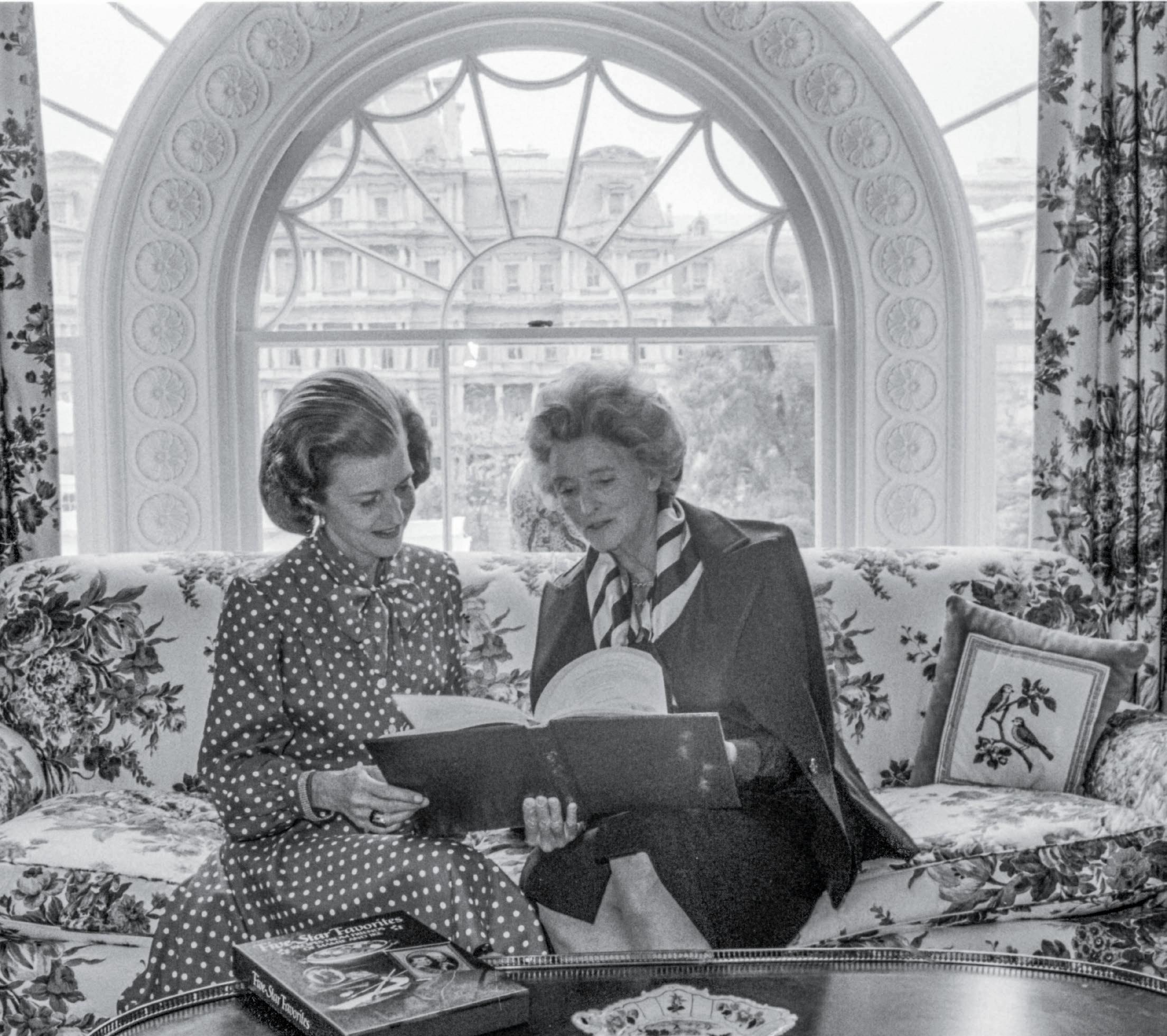

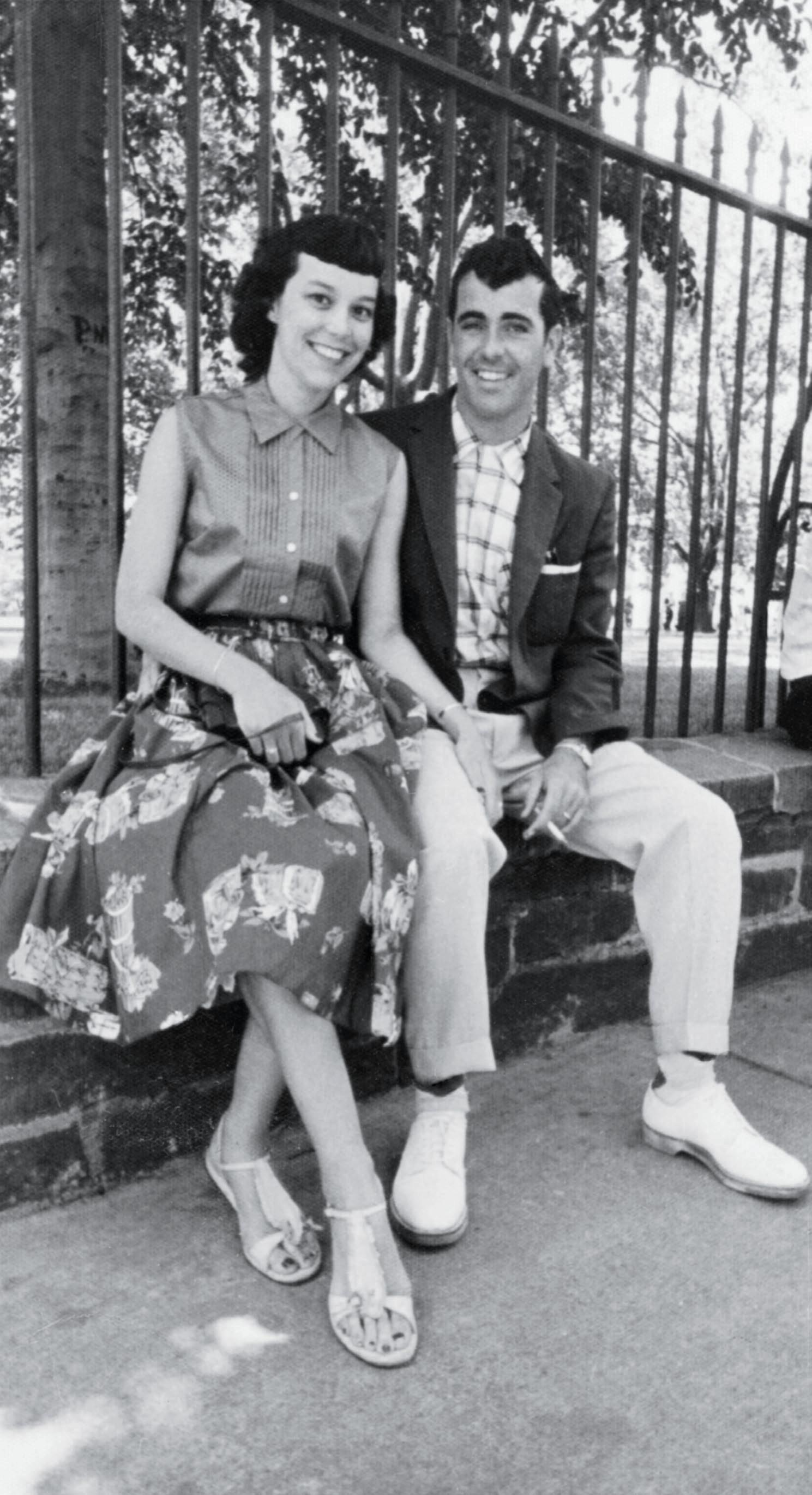

Occasionally a chance encounter leads us to an unpublished collection, and this issue includes two such examples. I happened to meet Jeffrey Parsons when he visited our White House History Shop in 2017. Our conversation led to an article about his experience exploring Washington, D.C., with his Rolleiflex in 1959, a time when the public could simply appear at posted hours to visit the White House. His candid shots of a dramatically evolving cityscape provide context for two moments in time on the tour line. Also in 2017, I learned of a collection of late-nineteenthcentury glass-plate negatives through a telephone call from Richard Hussey. Found in a bushel basket on his family’s Ohio farm, the collection includes two breathtaking views of the White House that he kindly shared

with us for publication. In 1889 Dr. Hussey’s grandfather rode the newly installed lift up to the observation deck of the Washington Monument with his heavy wooden view camera and, from there, captured an expansive view of the White House and its surroundings before the West Wing replaced a sprawling complex of greenhouses and while President Ulysses S. Grant’s brick horse stable still stood south of the newly completed State, War and Navy Building.

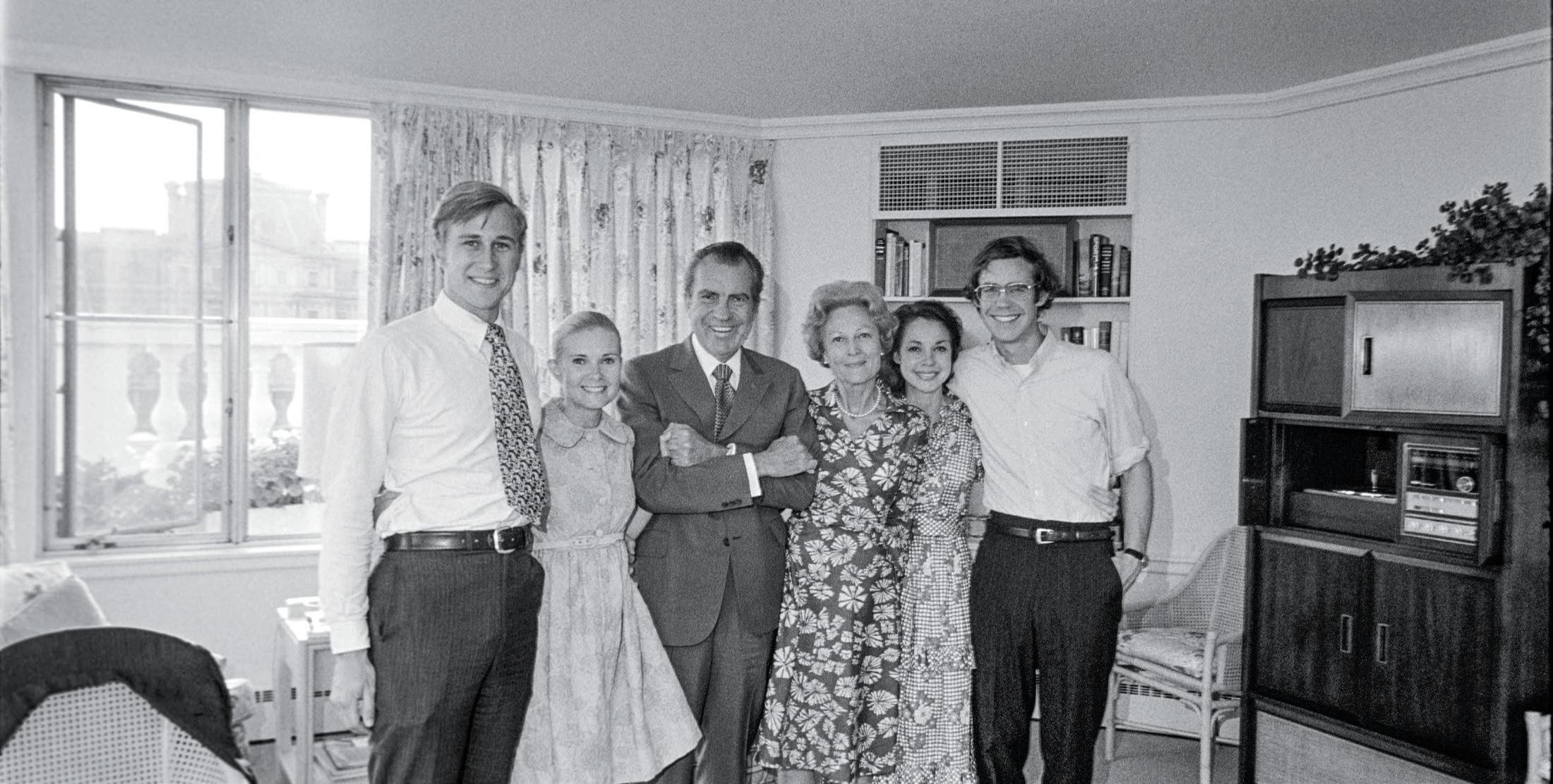

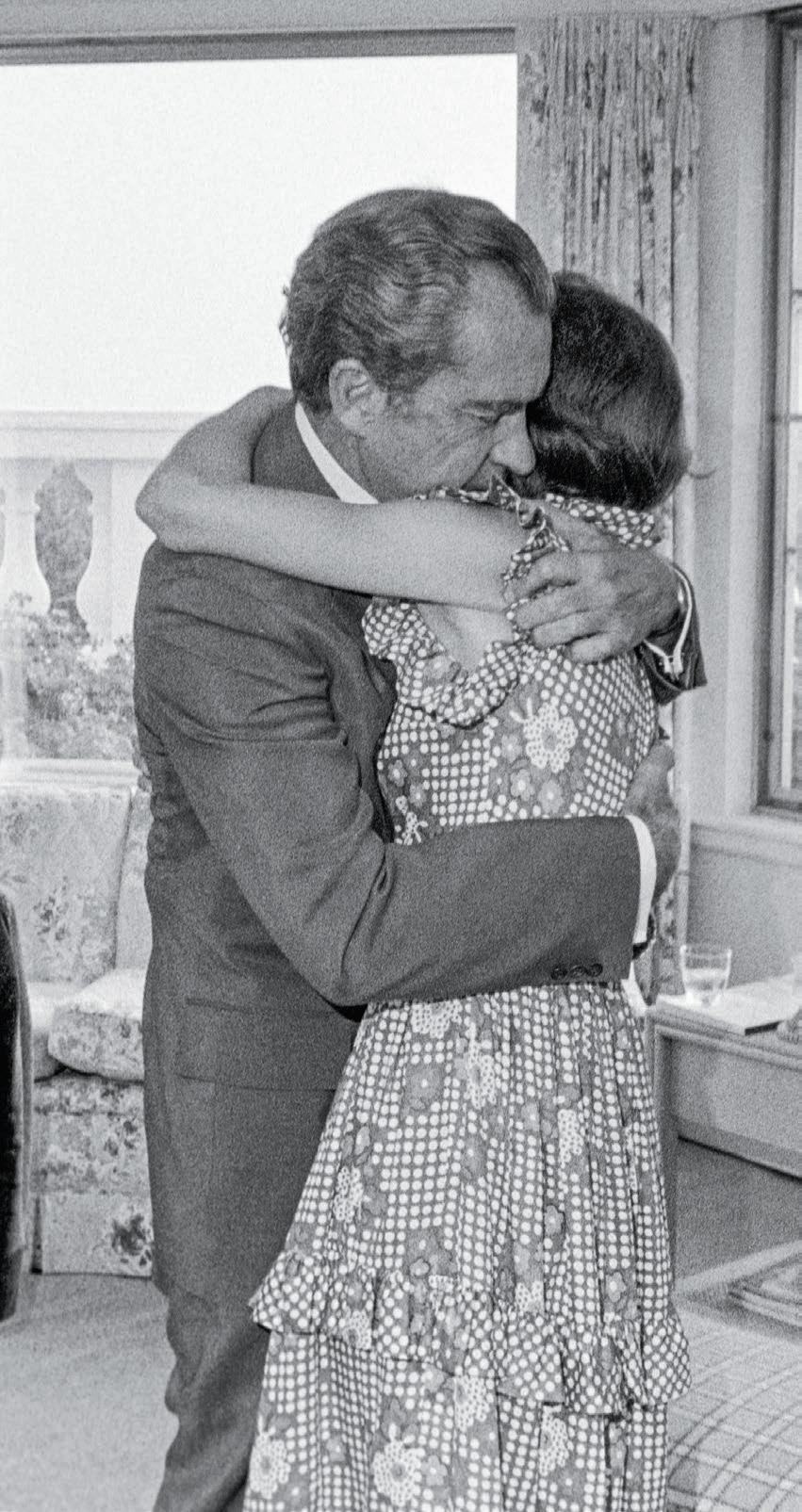

With this issue we also go behind the camera to learn more about the inspiration, access, and even constraints on the photographers who have covered the president at work. Susan Ford Bales provides the moving backstory that led her to use photography to “ignore the frustrations and embrace” all of her unique experiences as the president’s daughter living in the White House. The stories of the “ultimate insiders” are revealed by Kenneth T. Walsh, who profiles the work of all those who have held the title Official White House Photographer. Mary Jo Binker profiles of one of them—Ollie Atkins, who dutifully followed Richard M. Nixon’s “six and out rule” yet had the foresight to capture the president’s spontaneous embrace with his daughter during his final days in office.

An issue on White House photography would not be complete without visiting a few dusty attics and family albums. We are pleased to share ten of the most compelling of the hundreds of images submitted by our readers to the Quarterly’s call for photographs. Family vacations, holidays, and even a marriage proposal are among those treasured mementos published here. They represent not only souvenirs but a tangible connection between each contributor and the White House. In telling the story of her submission, Meredith Johnson expressed it beautifully, writing, “I love that my own history is now tied to White House history as well.”

marcia mallet anderson editor, white house history quarterly

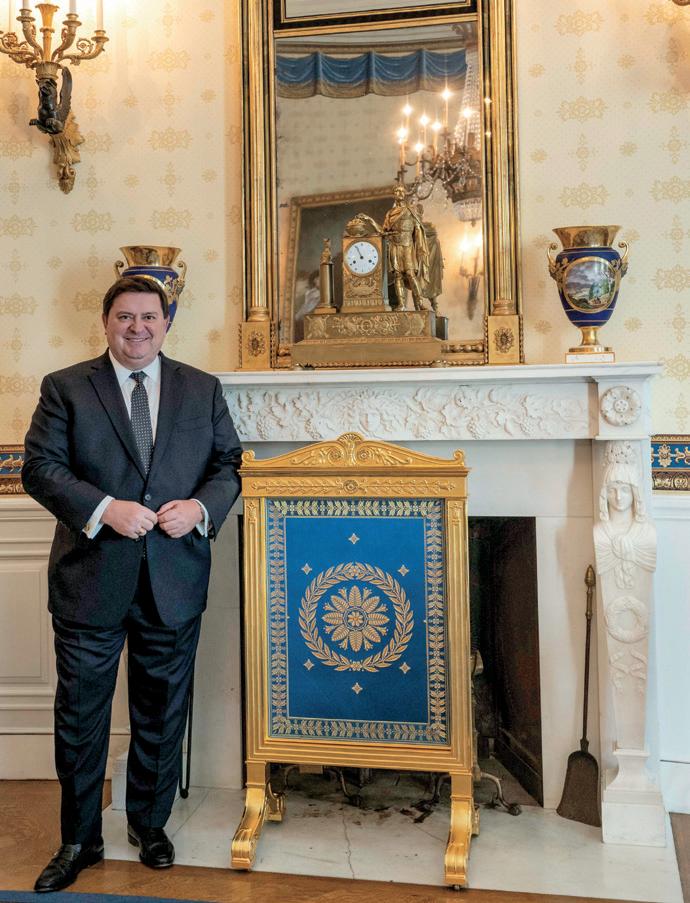

arts photographer

reviews his photographs on his laptop during a photo shoot to capture the newly refurbished Bellangé suite in the Blue Room for the cover of White House History Quarterly 56, which focused on the decorative arts collection, January 2020.

heading to the u.s. capitol on Constitution Avenue one sunny afternoon during the height of the tourist season, a friend wistfully remarked to me, “Boy, I wish I had a nickel for every photograph taken of the Washington Monument.” I replied, “You’d be far richer if you had a penny for every photo snapped of the White House.” Our thoughts were obviously focused on the compelling appeal of the two historic landmarks and taking for granted the now-universal ability to make instant photographs. But it was not always so. The earliest photographs of the White House were difficult and time consuming to make, and only a few photographers gained access to its rooms. Nevertheless, their photographs preserve views of White House interiors that would otherwise be known to us only through written descriptions by first families and their guests. GEORGE EASTMAN

clifford krainikPhotography, the process of recording images from nature, began during the mid-nineteenth century in France with the introduction of the daguerreotype. An amazingly beautiful image was made possible through a complicated process best suited for the scientifically trained. The procedure required that a silvered copper photographic plate become light sensitive through the action of fumed iodine and bromine. The plate was then exposed in a large, cumbersome wooden camera, much larger than a bread box. The photograph was made visible and permanent when exposed to the vapors of toxic mercury. The procedure was complex and fraught with variables that spelled failure, and of course it was dangerous.

The first photographs taken inside the White House were daguerreotypes. On February 27, 1846, President James K. Polk recorded in his diary, “At the request of Mr. Shank of Ohio, who was taking Deguerreotype [sic] likenesses of the ladies of the family in one of the parlours below stairs, [and] requested to take mine for his own use, and I gave him a sitting. He took several good likenesses.”1 Abel Shank was employed as a camera operator by the nationally renowned daguerreotypist John Plumbe Jr. It was probably Shank’s White House portraits of President Polk and First Lady Sarah Childress Polk that Plumbe made available for publication by the New York printmaker Nathaniel Currier in 1846, as these lithographs are clearly marked “from a daguerreotype by PLUMBE.”

Later in 1846 another daguerreotype photograph was taken inside the White House, but that sitting met with far less success. The prolific, self-taught portrait painter George Healy had prevailed on President Polk to sit for his likeness. Although war with Mexico had erupted and the demands of office

were overwhelming, the president graciously posed for the artist for thirteen hours in the White House. Then came Healy’s request to take a daguerreotype portrait, which the president dutifully recorded in his diary on June 16, 1846: “Mr. Healey [sic], the artist, requested the cabinet & myself to go into the parlour and suffer him to take a degguerryotype [sic] likeness of the whole of us in a group. We gratified him. We found Mrs. Madison in the parlour with the ladies.” Polk concludes his account of the episode with the terse remark: “Three attempts were made to take the likeness of myself, the Cabinet, & the ladies in a group, all of which failed.”2 Undaunted, Healy reassembled the presidential entourage on the South Portico and recorded an informal yet eminently important first portrait photograph taken outside the White House.

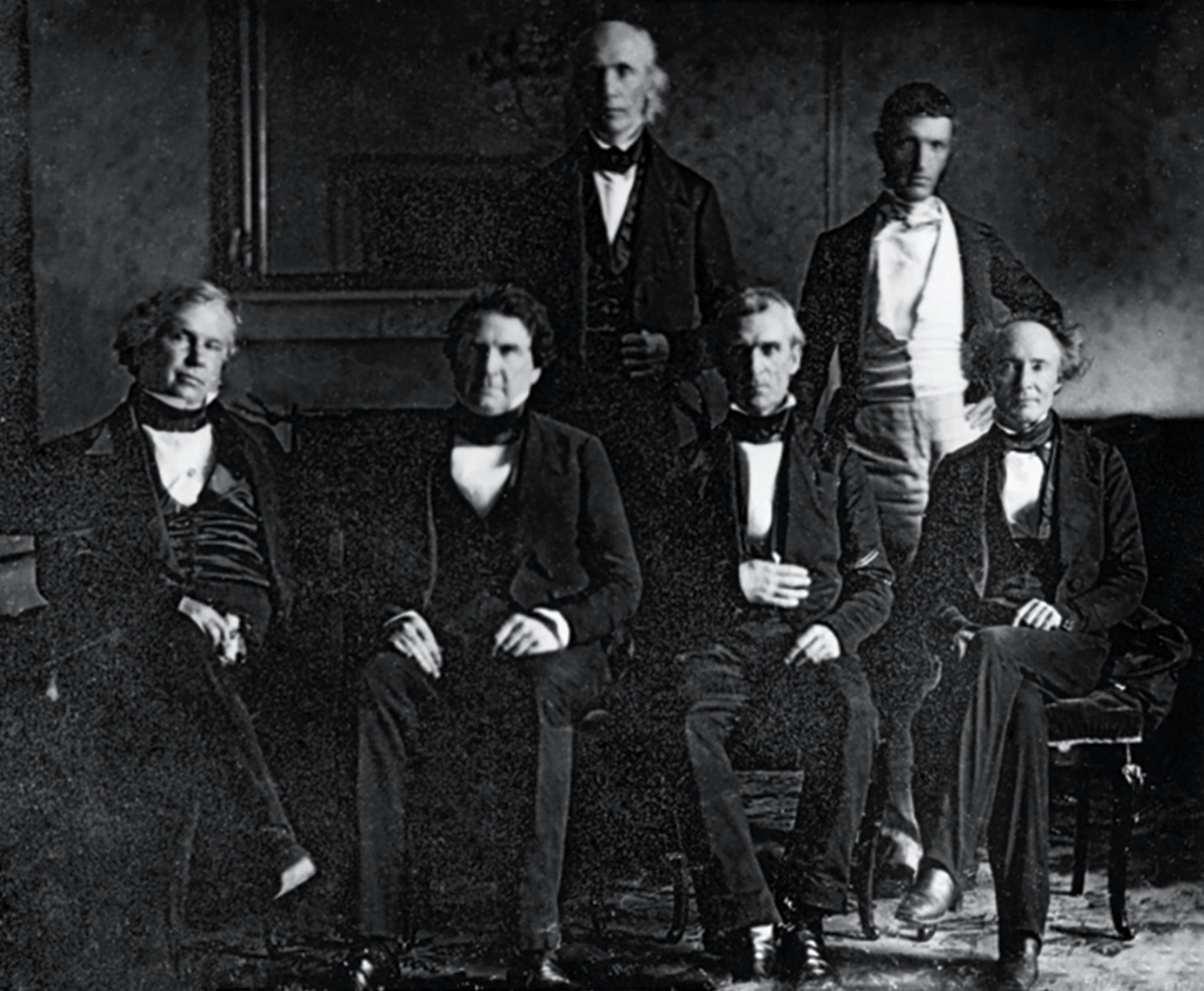

The first interior photograph of the White House that shows any decorative details is a remarkable group portrait taken by Plumbe that same year, 1846. President Polk and five members of his cabinet gathered in the State Dining Room for their formal portrait. The photograph has dual historic importance.

previous spread

A detail of a stereoview of the East Room taken in about 1867 by the prolific photographer George D. Wakely.

below

President James K. and Sarah Childress Polk posed with a group of their friends on the South Portico for George P. A. Healey in what would be the first presidential portrait ever taken with the White House exterior as a backdrop, c. 1846. Left to right: Secretary of State James Buchanan and his niece Harriet Lane, probably Mrs. Polk’s niece Joanna Rucker, Postmaster General Cave Johnson, Mrs. Polk, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, President Polk, Dolley Madison, and Matilda Childress Catron, who was Mrs. Polk’s cousin and the wife of Supreme Court Justice John Catron.

It is the earliest known portrait of a United States president with his advisers, and it is the earliest visual record of furnishings inside the White House. William Seale, the preeminent White House historian, examined the Plumbe daguerreotype group portrait and made some amazing observations. He noted:

The photograph shows whitepainted woodwork, which was customary throughout the house, and a highly figured, though not strongly contrasting wallpaper. The State Dining Room chairs appear in this group portrait. These

were made in the mode popularly known as “French antique” or Louis Quatorze. The carpeting is decorated with a flower pattern. In the background can be seen one of the marble mantels that President James Monroe ordered from Italy. Reflected in the huge mirror is the impression of a basketlike chandelier made of glass beads.3

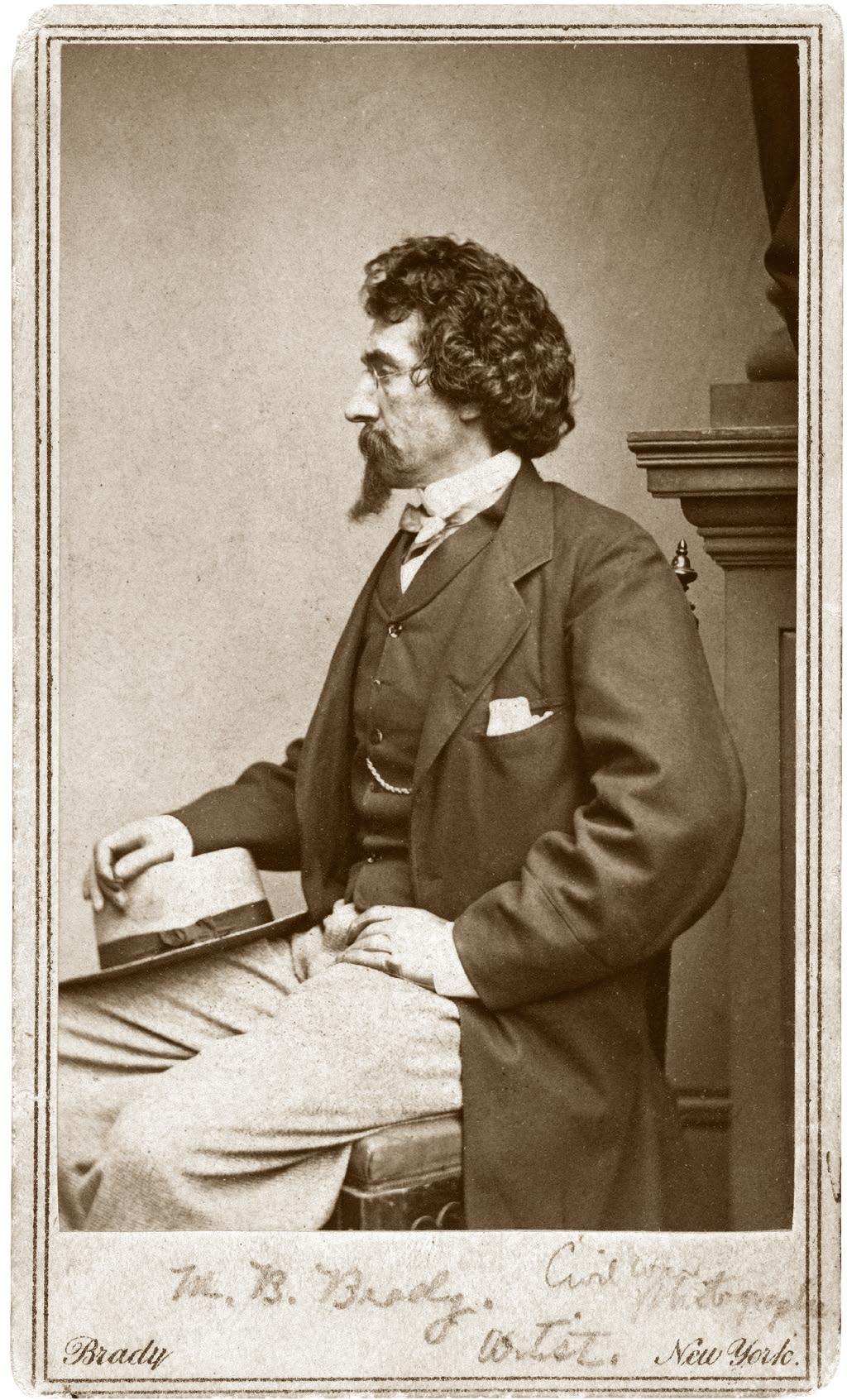

In February 1849, Mathew Brady, the future Civil War photographer, went to the White House and secured a handsome half-length daguerreotype portrait of President Polk and a second group portrait of a frail and exhausted

president with members of his cabinet. Unfortunately, both images display stark backdrops and are devoid of any details in the rooms of the White House.4

Fourteen years later, Mathew Brady returned to the White House to record the portraits of the Southern Plains Indian Peace Delegation that came to meet with President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. In the ensuing years between his visits, the daguerreotype had become obsolete and was replaced by the glass negative paper print process. Invented in 1850 by Louis D. BlanquartEvrard, the glass negative paper print process was quicker and cheaper and offered the ability to make multiple copies of an image as opposed to the single unique daguerreotype. These paper photographs are referred to as albumen prints, as the paper was sized with a solution containing egg whites. For several decades, 1860 to the late 1870s, the photographic industry was the largest consumer of eggs in America. By 1860 small-size albumen photographic prints, called cartes de visite, were used as calling cards, embracing the fad that had originated in Paris.

Another vastly popular application of the albumen photographic print was the production of stereoviews. Stereoscopic views were produced with specially designed twin lens cameras capable of taking two pictures simultaneously from a standpoint corresponding to the space between the human eyes, on average 2½ inches. Stereoscopic paper prints were mounted on cardboard and viewed in a device known as a stereoscope, so that the two images blended, imparting a sensation of depth and dimension. Stereoviews are sometimes referred to as the original virtual reality.

The stereoscope actually preceded the birth of photography. As early as 1838 the Englishman Charles

Wheatstone had invented a device for viewing drawings in three dimensions. Stereoscopic portrait daguerreotypes were produced on a limited basis, but with the introduction of paper photography there was an immediate, overwhelming, and vast application of the process. During the apogee of the stereoview, 1860–90, it would be difficult to imagine any human endeavor that was not photographed with the stereo camera—spanning the globe, depicting fine art, demonstrating scientific investigation, recording travel and exploration, providing a vehicle for comedy and risqué voyeurism, and showing views of the moon, the stars, and the very heavens above.

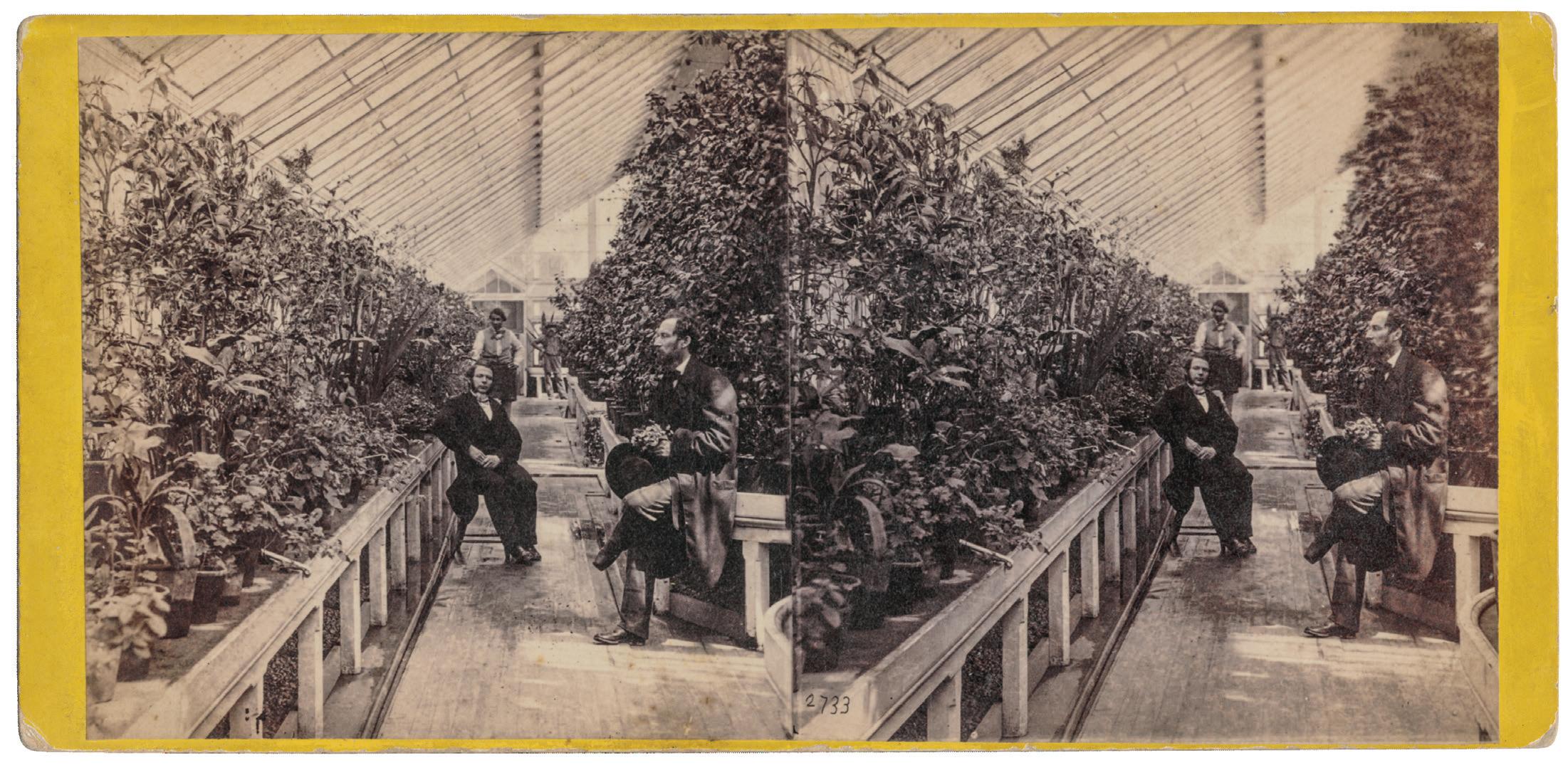

So it is not at all surprising that the celebrated photographer Mathew Brady would bring his stereo camera to the White House to take portraits of the Indian delegation in 1863. Members of the Cheyenne and Kiowa tribes with their interpreter, John Simpson Smith, and agent, Samuel G. Colley, were gathered in the White House Conservatory to have a group portrait made. They were joined by other diplomatic visitors to the White House. Three distinct stereoscopic group portraits were taken. In each view the foliage, potted plants, framing for the glass panes, and wide

The popular handheld stereoscope was a nineteenth-century optical device used to view two images as one. Specially designed stereo cameras took two photographs of the same scene from slightly different angles, and, when seen through the stereoscope, they gave the illusion of a three-dimensional image. Most of the commercially produced photographs taken inside the White House from 1860 to 1890 were made and viewed in 3-D.

The White House Conservatory is seen in this albumen stereoview taken by Mathew Brady, in March 1863. The occasion for Brady’s visit to the White House was to secure the portraits of the Southern Plains Indian Peace Delegation. In addition to three group portraits of the Cheyenne and Kiowa chiefs, Brady took a more expansive view of the greenhouse that includes Lincoln’s private secretary, John Nicolay (seated on the right), along with a visiting Indian agent from Oregon. Two unidentified attendants also appear incidentally in the image, probably the very first photographic record of members of the White House staff.

plank wooden floorboards are visible. A fourth stereoview of the Conservatory was made by Brady, this one showing a much larger, expanded view of the greenhouse, giving the viewer a better understanding of the enormity of the room. Posed seated in this image is President Lincoln’s personal secretary, 31-year-old John George Nicolay, joined by a man sometimes identified as Senator James Willis Nesmith, formerly superintendent of Indian affairs for Washington and Oregon. Two African American White House staff members are also present. The four stereoviews of Lincoln’s White House Conservatory photographed by Mathew Brady in the spring of 1863 share one thing in common: they are portrait photographs not room portraits, yet they reveal room details.5

There are several references to amateur photographers who made stereoviews of the interior of the White House during the early to mid-1860s, among them Montgomery Meigs, Titian Peale, and B. B. French. However, no examples of their work are extant. These photographs seem to have been made

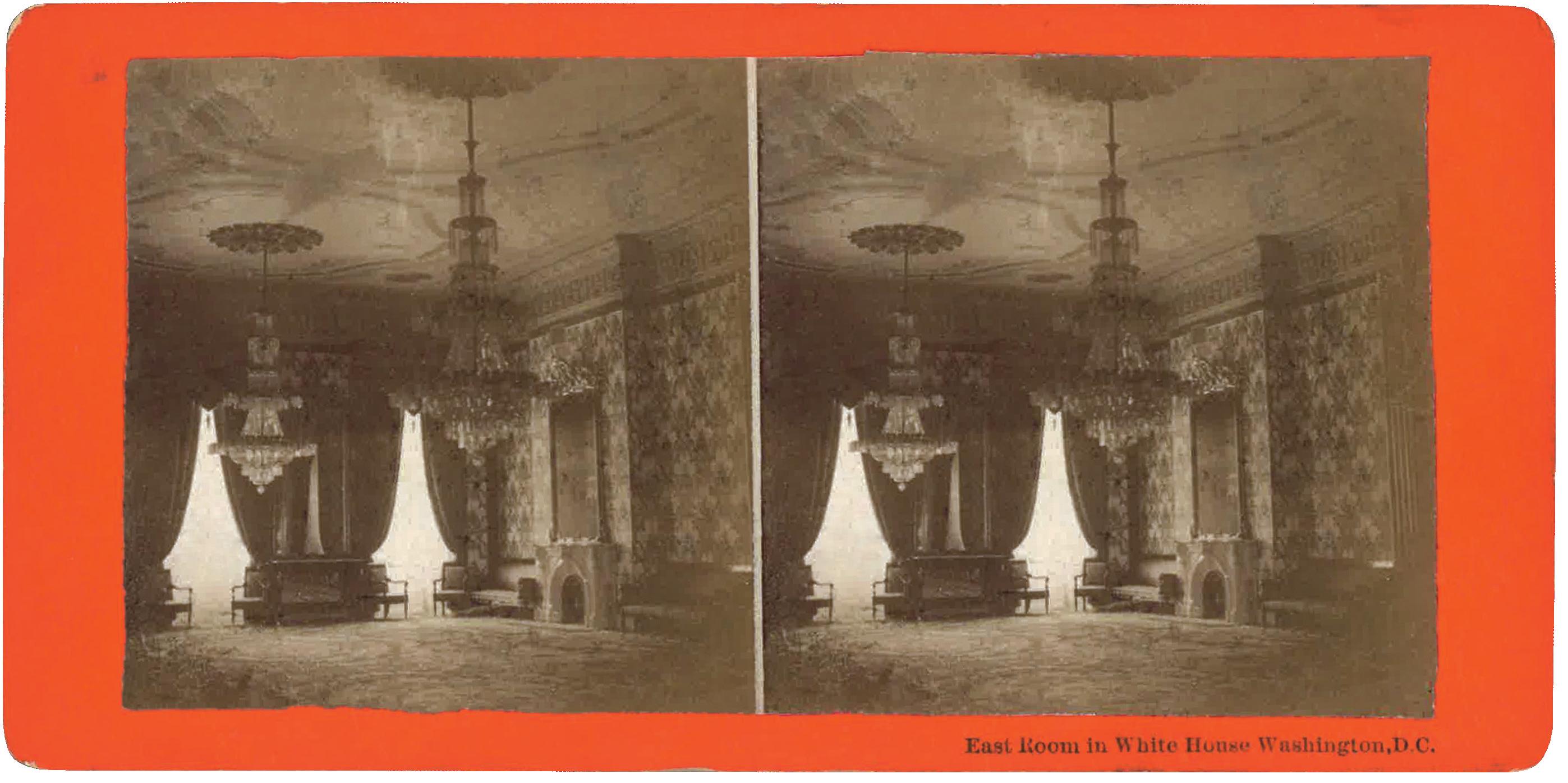

only for their private use. The earliest known surviving interior architectural view of the White House is a stereoview taken by an unidentified photographer with the brief printed title “East Room in White House, Washington, D.C.” According to William Seale, the view shows “the East Room in the time of President Lincoln, from a stereopticon view [a stereoview], the only known photograph of this interior as Lincoln knew it. Rich floral carpeting, shimmering with the reds and blues of the new aniline dyes, complemented the wallpaper, with its heavy gilt highlights. The regal effect, so odd in a republic, was always given free rein in this room.”6

An examination of this stereoview revealed that the photographic prints were not cut separately and mounted on the cardboard support, the procedure for originally issued stereo-photographs. The orange color of the mount is also at variance with the standard yellow color mounts of commercially issued stereoviews from the early to mid1860s. So although the content of this exceedingly rare stereoview photograph depicts the East Room during Lincoln’s

administration, it was probably printed and issued during the mid-1870s.7

The earliest attributed photographs of rooms within the White House were taken by the prolific Western photographer George D. Wakely. Wakely began his photographic career in Chicago in 1856 before moving to Colorado, where he quickly established himself as one of Denver’s leading photographers. Late in 1864 Wakely came east and located his gallery at 524 Pennsylvania Avenue below Third Street NW. In mid-December 1865 he advertised a photograph of the Capitol for sale, “the best and only picture taken that embraces the whole of this magnificent building. Those wishing to make Christmas Presents cannot do better, than to procure one.”8 By March 1869, just in time for President Ulysses S. Grant’s Inauguration, Wakely touted that he had for sale the “largest assortment of views for the stereoscope of the Capitol, White House and all the Public Buildings in Washington.”9 During his five-year stay in Washington, from late 1864 to the spring of 1869, Wakely photographed and published more than eighty known photographs

of the Federal City in at least two sets of stereoviews, National Capitol of U.S. and Smithsonian Series . 10 Although Wakely issued a considerable number of stereoviews of Washington, D.C., today far fewer of these images are extant than are his photographs of Colorado and the West. Wakely photographed the U.S. Capitol and the exterior of the White House extensively, but his interior views of the Executive Mansion are rare, with only two known separate views—“Interior White House, Great East Room” and “The Blue Room.” They were probably taken around 1867 during President Andrew Johnson’s tumultuous administration.11

Wakely identified his stereoview of the East Room with a printed label pasted to the back of the photograph that reads, “Interior White House, Great East Room.” This is an apt title, as the East Room is the largest designated area in the Executive Mansion, extending from the North Front to the south rear of the house, approximately 80 × 37 feet. The room was designed by the architect James Hoban with the idea that the expansive area would be used

The East Room was captured by an unidentified photographer, c. 1861–65, during President Abraham Lincoln’s administration. It is the earliest published stereoview of the interior of the White House.

for receptions and events. It was generally sparsely furnished to accommodate large gatherings. Just a few years before this photograph was taken, the earthly remains of the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln lay in state in this room, and his funeral was held here on April 19, 1865. Patrick Phillips-Schrock writes, “At the time of Lincoln’s death the East Room contained twenty-four chairs, four sofas, four tables, eight sets of drapes, eight sets of lace curtains, eight mirrors, and one carpet,”12 and an inventory of the room confirmed that all of the furniture was in poor condition.13

During Andrew Johnson’s stay in the White House the East Room underwent a major transformation that included the removal of most of the Lincoln furnishings. Johnson’s daughter, Martha Patterson, directed the decorative makeover with the addition of yellow wallpaper with a black and gold border, lace curtains, and reupholstered furniture. The ceiling was repainted, frescoes were added, and the ceiling centerpieces and cornices were regilded. The East Room was finished in early 1867.14 This was about the time George Wakely

took the stereo-photograph.

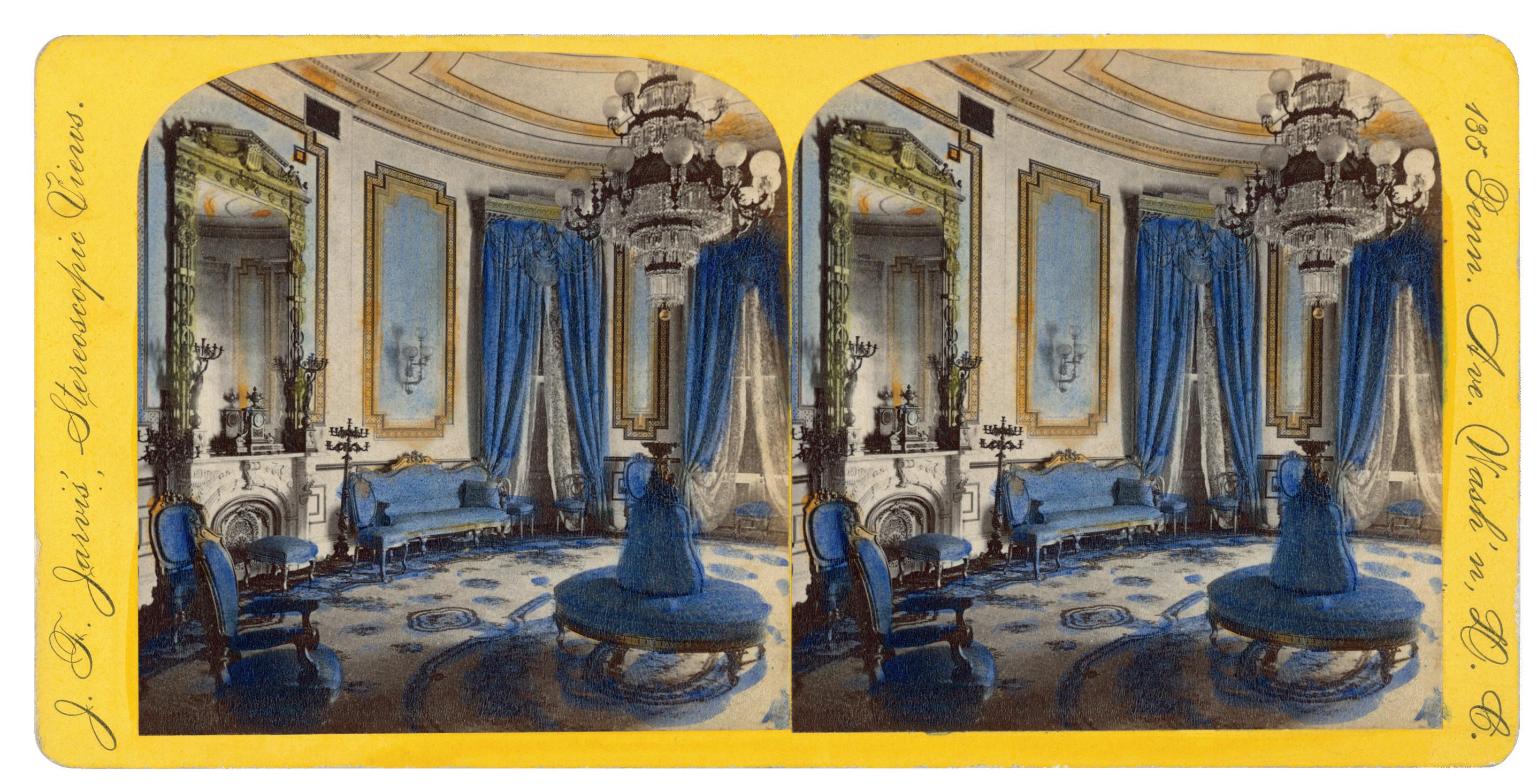

The other interior stereoview of the White House taken by Wakely in the late 1860s may qualify as the earliest known identified photograph of the Blue Room. The elliptical parlor is used for receptions and has traditionally maintained a blue color scheme for drapes and furniture fabrics. The decorative influences of Harriet Lane, President James Buchanan’s niece and acting first lady, are apparent in the Wakely photograph. The parlor is outfitted with Rococo Revival furniture purchased by Miss Lane with proceeds from the sale of earlier White House furnishings. The room is dominated by a large circular settee positioned under a complex globe-clustered chandelier. The geometric patterns on the walls were stylistic elements introduced by President Andrew Johnson’s daughter about 1867.

Following in George Wakely’s pioneering footsteps, several local and outof-town photographers gained access to the White House during the Ulysses Grant and the Rutherford B. Hayes administrations. F. H. Bell, a Pennsylvania

Avenue photographer, published a stereoview in 1867 titled “Blue Room in the President’s House,” and in the mid-1870s the firms of C. M. Bell and James J. Jarvis issued several interior White House views. The most prominent and prolific among these early photographers, however, was the firm of Edward & Henry T. Anthony.

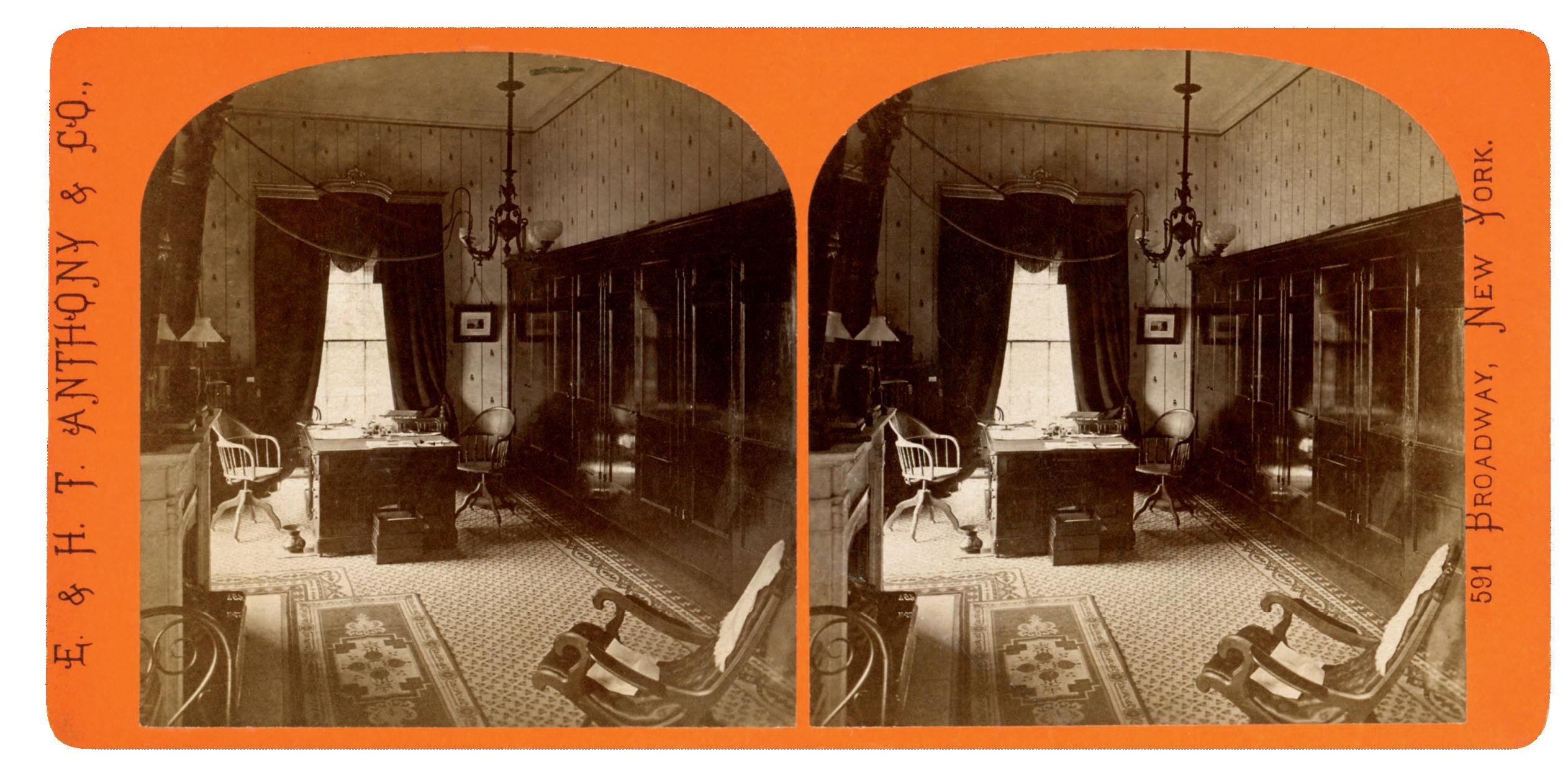

It was this New York City–based company that published Mathew Brady’s stereoviews of the Southern Plains Indian Peace Delegation in the White House Conservatory in 1863. In February 1871, E. & H. T. Anthony issued a series of stereoviews called Views in Washington City, D.C., which included over a dozen interior views of the White House. Among them are “Red Room” (no. 8400), “Green Room” (no. 8401), “Blue Room” (no. 8402), “Blue Room No. 2 ” (no. 8403), “State Dining Room” (no. 8405), “The President’s Private Secretary’s Room” (no. 8406), “Private Room of the Cabinet” (no. 8407), and eight other views of the Conservatory (nos. 8408–16).15

Other local Washington, D.C. photographers took stereo-photographs of

the White House including D. Barnum, the Kilburn Brothers, William M. Chase, J. W. and J. S. Moulton, and John Soule. By the time William McKinley assumed the office of president in 1897, every major publisher offered views of the White House. The Keystone View Company of Meadville, Pennsylvania, was still adding negatives to its collection as late 1952, with a selection of views of every public room in the White House.16

For stereoscopic photographers, the White House was a continuously fascinating subject, as they documented changing styles and fashions of interior decor. The early stereoviews of the White House not only record the evolution of room designs and furnishings; they do so with the magnificent added feature of dimension. The stereoscope enables the viewer to “step into the room” and understand the spacial relationships among objects. Stereoscopic photography, the nineteenth-century version of virtual reality, is a vital source of information for historians and an enduring interest of the American public.

Sometimes publishers of stereoviews applied hand-coloring to their photographs. James J. Jarvis obviously considered his photograph of the Blue Room worthy of color. He applied tinting to the drapes, furniture, and carpeting of the lush room.

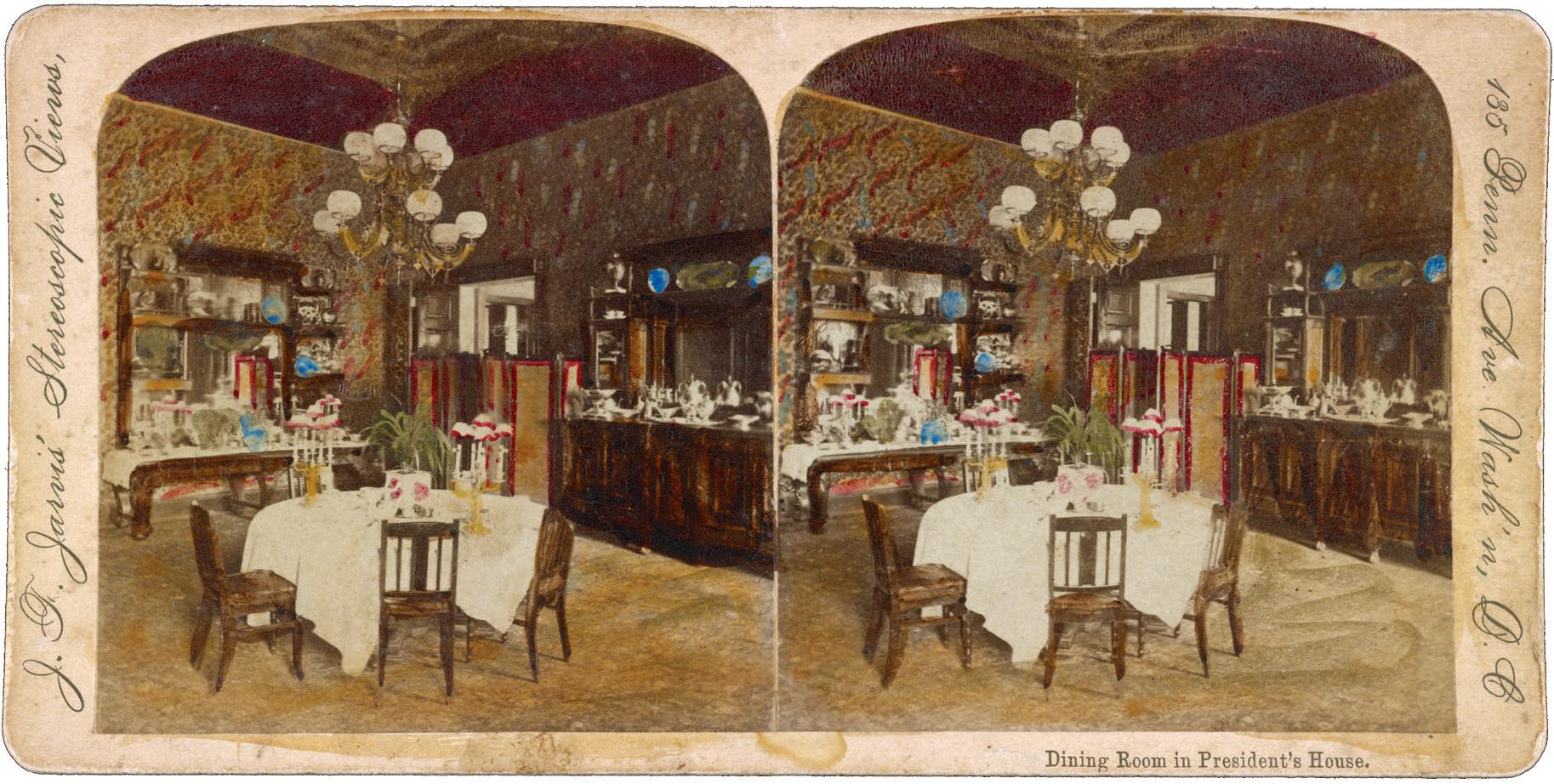

By the late 1870s photographers were occasionally asked to record special events at the White House. First Lady Lucy Webb Hayes invited James J. Jarvis to photograph the table set in the State Dining Room for her luncheon for more than fifty young ladies.

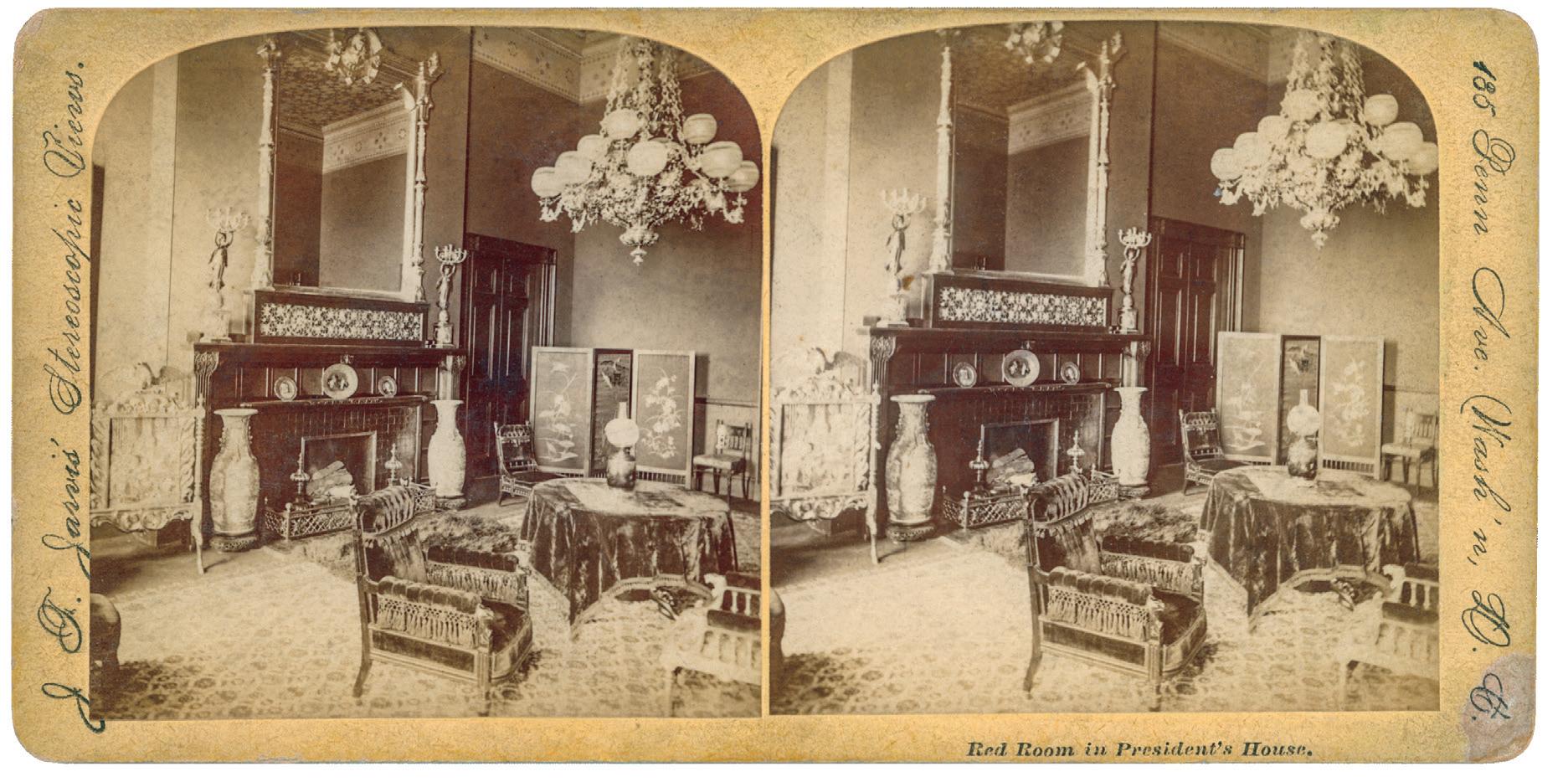

Jarvis’s stereoview of the Red Room, c. late 1890s.

Entitled “President’s Private Dining Room,” this hand-colored albumen stereoview by Jarvis shows the small dining room, known today as the Family Dining Room, in the early 1880s during the Hayes administration. It was First Lady Lucy Hayes who introduced the large mahogany table and sideboard into the room.

This image of the Green Room is one of a dozen stereoviews of White House interiors included in a series of views of Washington, D.C., made by E. & H. T. Anthony, in February 1871.

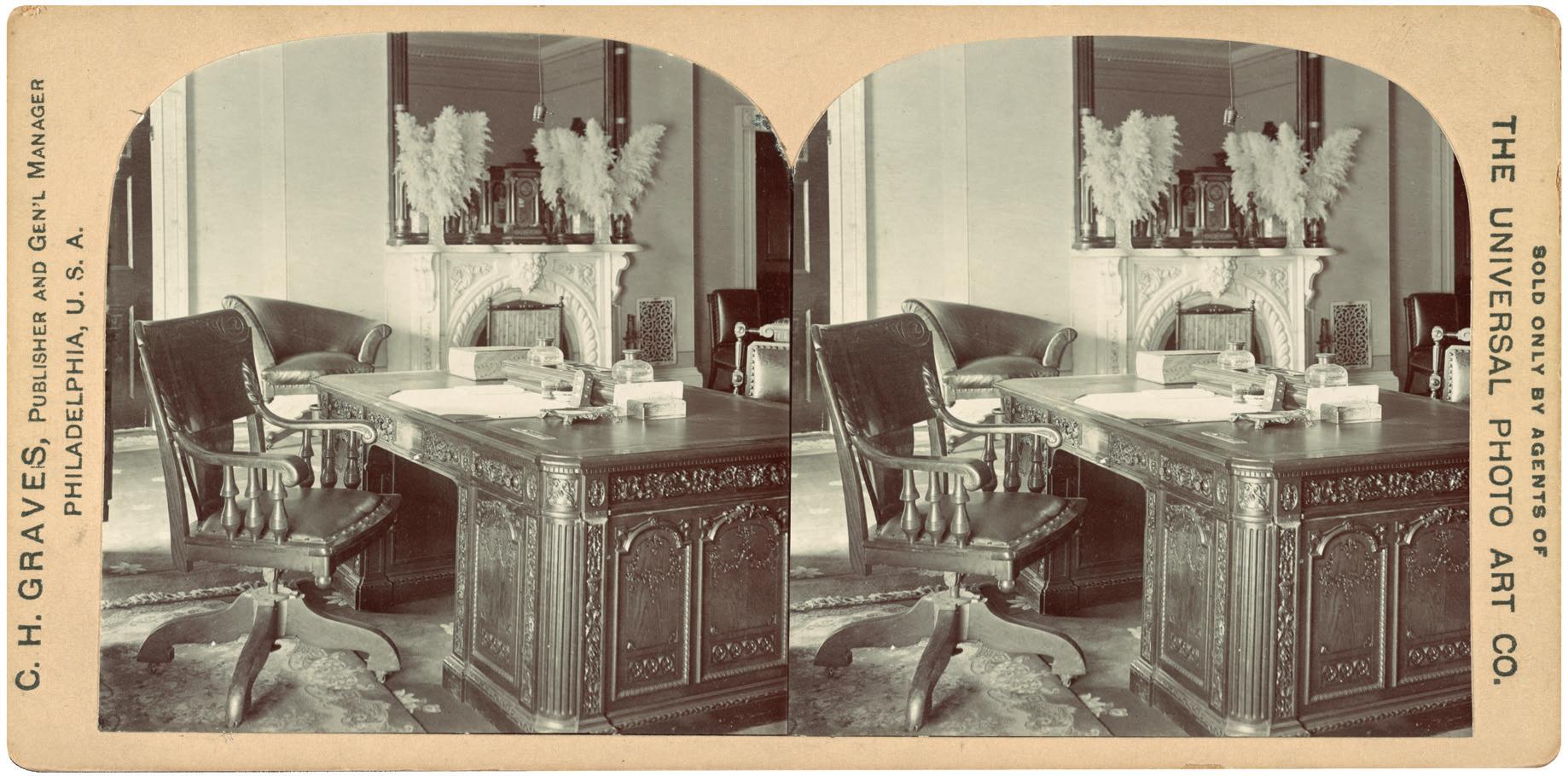

Entitled “The President’s Private Office, Washington, D.C.,” this albumen stereoview by C. H. Graves, 1900, focuses on the Resolute desk, which was given by Queen Victoria to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880 and has since been used by many presidents.

This stereoview of “The President’s Private Secretary’s Room,” taken during Ulysses S. Grant’s administration in February 1871 by E. & H. T. Anthony, is the earliest known view of the room that is today the Lincoln Sitting Room.

Photographed in the early 1870s, this stereoview of the White House Library by C. M. Bell is probably the earliest photograph of the oval room on the Second Floor. The space today is known as the Yellow Oval Room. The Library was moved to the Ground Floor in 1935.

notes

1. James K. Polk, diary, February 27, 1846, The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, ed. Milo Milton Quaife (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1910), 1:255.

2. Polk, diary, June 16, 1846, in ibid., 1:473–74.

3. Quoted in Clifford Krainik, “The Earliest Photographs of the White House,” in The White House: Actors and Observers, ed. William Seale (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002), 42–43.

4. Clifford Krainik, “Discovered: An Unknown Brady Portrait of President James K. Polk and Members of His Cabinet,” White House History, no. 21 (Fall 2007): 78–81.

5. Clifford Krainik and Michele Krainik, “Photographs of Indian Delegates in the President’s ‘Summer House,’” White House History, no. 25 (Spring 2009): 64–69.

6. William Seale, The White House: The History of an American Idea (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2019), 105.

7. These observations are based on my examination of the original stereoview in the collection of the White House on July 7, 2019, made possible by the assistance of Lydia Tederick, curator of the White House.

8. Advertisement in Washington Star, December 19, 1865, 3.

9. Advertisement in [Washington] Daily Critic, March 6, 1869, 1.

10. Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2000), 575–76.

11. Some idea of the rarity of Wakely’s interior views of the White House from the mid-1860s can be gained through a review of their presence in public photographic archives. The Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress lists only one stereoview by Wakely, a view of the “Bronze Door of the United States Capitol,” but no interior view of White House. The Getty Photographic Archives has a large selection of Wakely’s extraordinary Western stereoviews, but only a few Washington views and only one interior stereoview of the White House, “The East Room.” The New York Public Library maintains the largest collection of stereo-photographs in the United States, with holdings of more than 41,000 views. Its extensive inventory lists eighty-four stereoviews taken and published in Washington, D.C., by George Wakely between 1865 and 1869. But again, like the Getty Museum, it has only one interior view of the White House, of “The East Room.” The George Eastman Museum has two interior stereoviews of the White House by George D. Wakely. In 1990 William Seale was a consultant for the historic restoration

of the George Eastman House and subsequently became aware of two rare Wakely views of the White House held in its collection.

12. Patrick Phillips-Schrock, The White House: An Illustrated Architectural History (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2013), 170.

13. Betty C. Monkman, The White House: The Historic Furnishings and First Families, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2014), 133.

14. Ibid., 136.

15. The photographic historian Peter Penczer provided information about the 1871 White House views by E. & H. T. Anthony.

16. John S. Waldsmith, Stereo Views: An Illustrated History and Price Guide (Radnor, Penn.: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1991), 164.

Sources for captions: Historical information about the rooms in the White House is from White House Historical Association publications listed above and The White House: An Historic Guide, 24th ed. (2017), William Seale, The President’s House: A History, 2nd ed. (2008), and room descriptions on the association’s website, whitehousehistory.org. The Philadelphia Times’s account of First Lady Lucy Webb Hayes’s luncheon for fifty young ladies was written by “Miss Grundy” and posted on February 27, 2014 , on the Etiquipedia website, http:// etiquipedia.blogspot.com.

richard s. hussey

My grandfather thought of himself as a photographer.

Most people thought he was a farmer.

—Richard S. Hussey

my grandfather walter john hussey was born on April 6, 1865, on the Hussey Greenwood Farm, adjoining the picturesque village of Mount Pleasant in Jefferson County, in the rolling forested hills of eastern Ohio.1 This historic hilltop village, where I grew up seventy-seven years later, was founded in 1803 in part by North Carolina Quakers (Society of Friends). 2 Mount Pleasant is important for its role in the abolitionist movement, as a prominent station on the Underground Railroad, a place of safety west of the Ohio River for runaway slaves making their way north to freedom from the southern states. Also noteworthy, the first Quaker Yearly Meeting House west of the Allegheny Mountains was built in Mount Pleasant in 1814.3 The Ohio Yearly Meeting was held in this enormous historic two-story brick building, capable of seating two thousand people, until 1918. The land for the Hussey Greenwood Farm (109 acres) was purchased in 1847 by Penrose Hussey (1800–1872), Walter’s grandfather. Penrose built a fourteen-room brick house in 1848 and a three-story hand-hewn timber-framed barn in 1853.4 When Penrose died in 1872, the old homestead was purchased by his son, Asahel (1833–1918).5 Asahel and his wife, Martha, married in 1862 and raised Walter

(1865–1959) and two daughters, Anna Margaret (1867–1883) and Helen Jane (1868–1956), on the farm. In 1873 Asahel was recorded as a minster in the Society of Friends and thereafter traveled throughout the United States and also abroad to participate in religious services and conventions. When Asahel and Martha permanently moved to Whittier, California, in 1908, Walter remained on the farm, where he and his wife, Bess, who had married in 1898, raised their five children. The Greenwood Farm was in the Hussey family for four generations prior to being sold in 1970.

I never knew my grandfather was an exceptional photographer until I came into possession of his glass-plate negatives, since I only knew him to be a farmer when I was growing up. The information I have on Walter’s early life in Mount Pleasant and the development of his interest in photography is very limited, as few records were kept. Walter received most of his education in the Mount Pleasant schools. However, when Walter’s sister, Anna Margaret died of consumption in May 1883, his mother, Martha, took him and his sister Helen out of the Mount Pleasant schools and enrolled them in the fall of 1883 in the Raisin Valley Seminary, a four-year preparatory school

previous spread

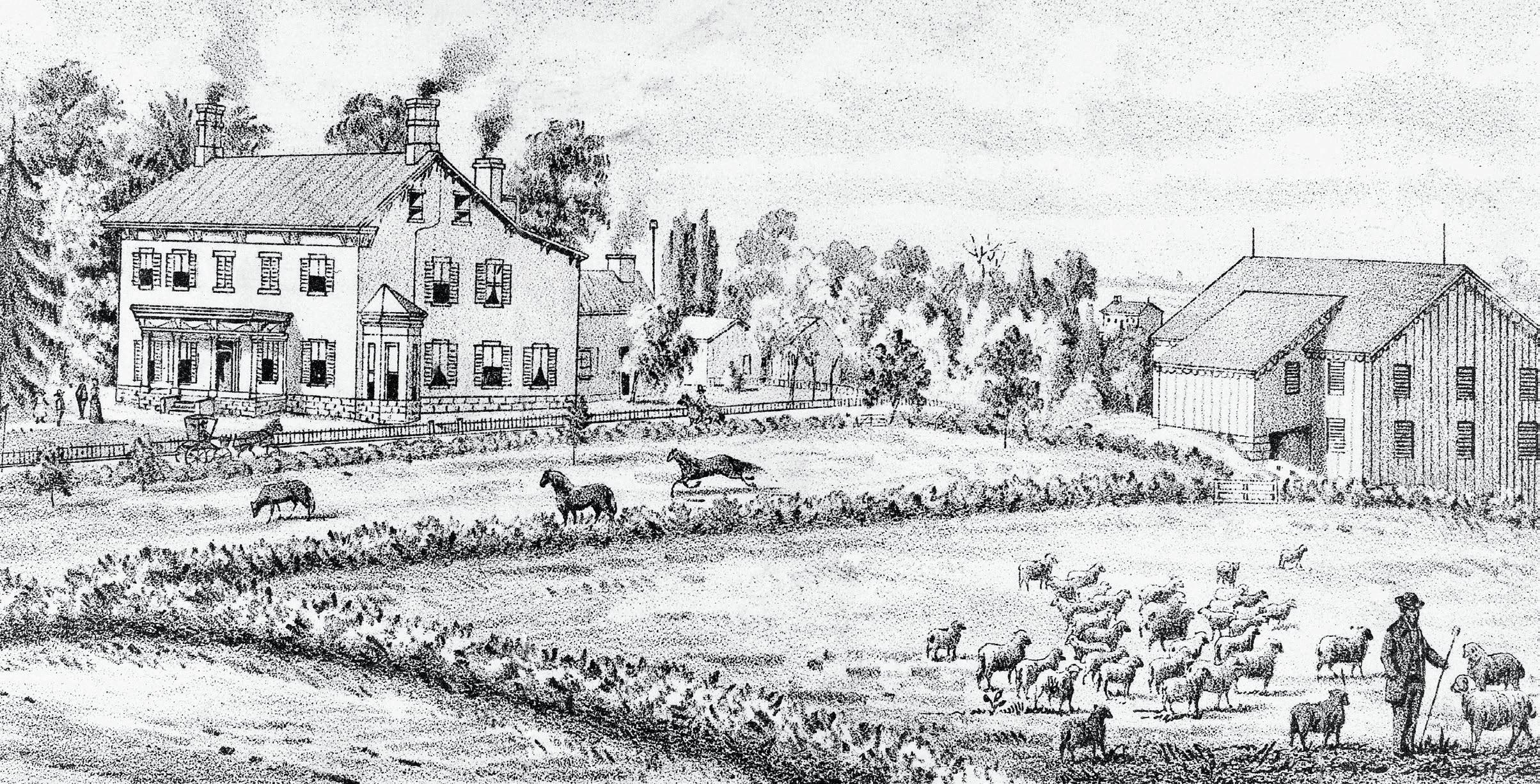

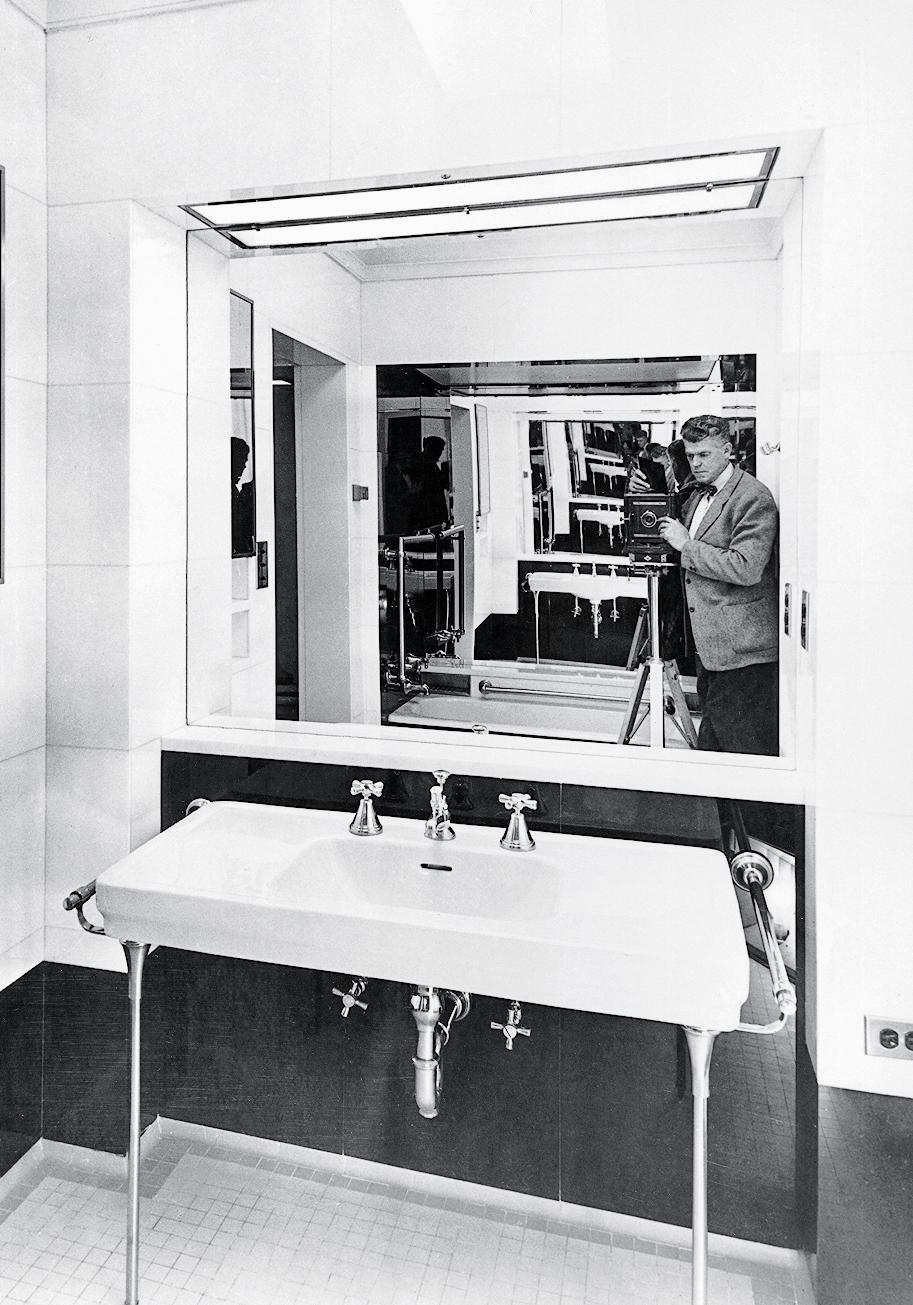

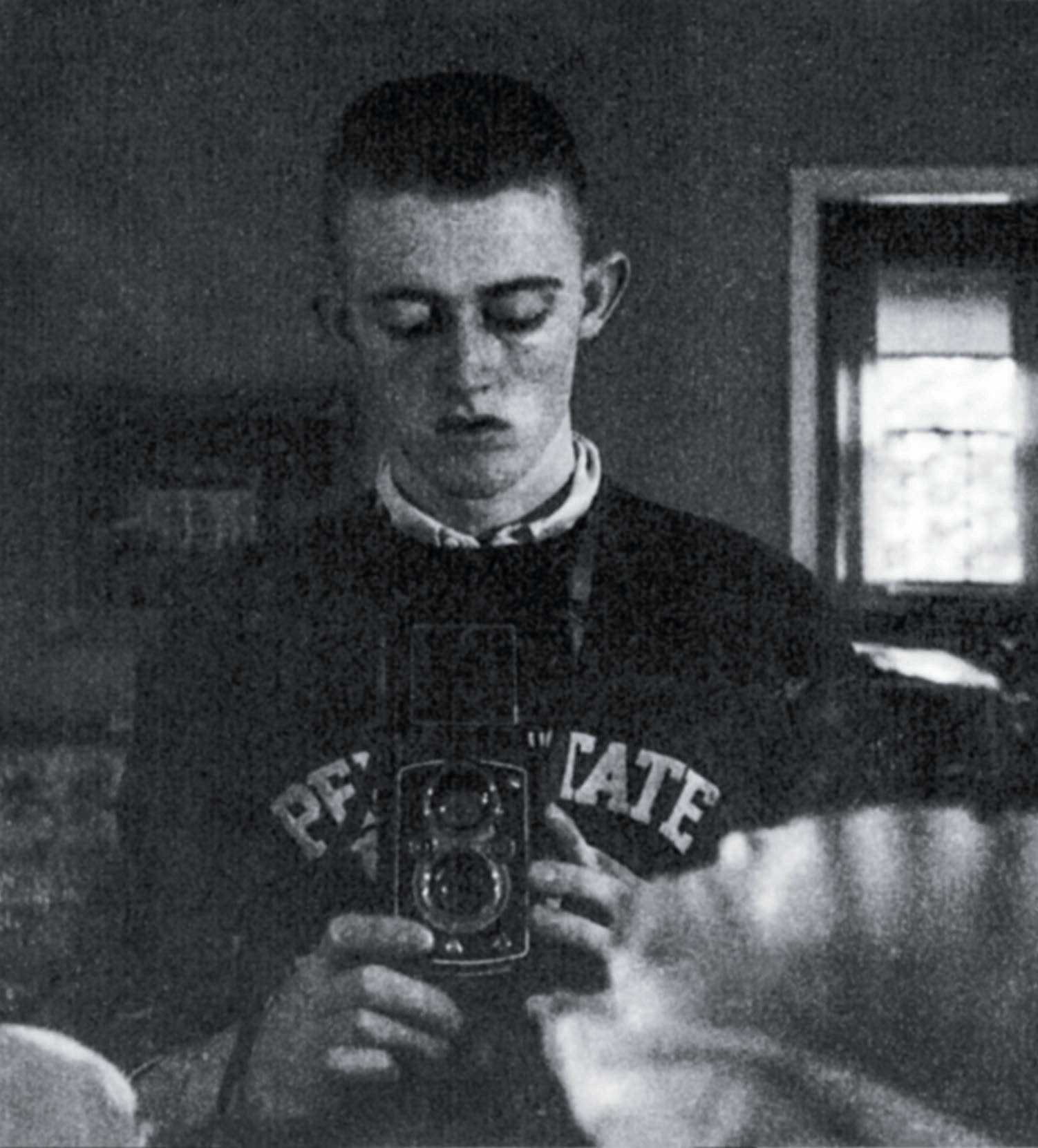

Walter J. Hussey captured his formal self-portrait with the help of a mirror in 1889. He used the camera in the image to photograph the White House on a trip to Washington, D.C. left

Walter J. Hussey’s portable large format Universal camera features a mahogany box and extra-long leather bellows. He purchased the camera for about $38 in 1893. It descended through his family to the author, his grandson.

below

Walter Hussey was born in 1865 on the Hussey Greenwood Farm, which was purchased by his grandfather in 1847. The house and barn built by his grandfather can be seen in an 1880 illustration published in the History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties, Ohio. Hussey kept a darkroom in an unfinished portion of the farmhouse.

sponsored by the Society of Friends, near Adrian, Michigan. Walter graduated from the Raisin Valley Seminary in the spring of 1885 and that fall he enrolled in the Society of Friends’ Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. He withdrew from Earlham College in January 1886 to travel with his family by train to Mexico City to visit missions his father helped establish. He returned to the Greenwood Farm in April of that year and did not continue his education at Earlham College. There is reference in family notes to Walter traveling to California in 1887, where, according to a business card, he was involved in selling real estate in the Santa Ana Valley near Earlham, California.

When Walter returned to the farm in 1888, he apparently had become very interested in photography, and during the period 1888–1910 he became an accomplished amateur photographer, as revealed in the breadth and quality of the images he captured on dry glass-plate negatives. I do not have any record of where and by what means Walter learned photography. However, at the time he became interested in photography the availability of commercially produced gelatin dry glass-plate negatives, coupled with the wide distribution of do-it-yourself photography instruction manuals,6 enabled individuals with an interest in photography

to become self-taught. Most likely this is the means by which Walter developed his skill in photography. Walter used two 5 × 8 inch large-format view cameras to take his photographs, and photographs made by both cameras are included in this article. A large wooden box camera was used in the 1889 self-portrait, which was taken by means of a large mirror. This would be the camera that Walter used for his early photography. The lens on this box camera used Waterhouse stops inserted in the lens mount to control light entering the camera. Since the lens did not have a shutter, the lens cap served that purpose and was removed and then replaced after a certain time interval to capture the image on the glass negative. In the self-portrait, Walter has the lens cap in his right hand. When a lens cap is used as a shutter, the subjects being photographed are required to remain still; any movement blurs the image on the negative. This blurring occurred in a few of Walter’s Washington, D.C., street scenes. The second camera Walter owned was the portable English-style folding Universal view camera manufactured by the Rochester Optical Company in Rochester, New York,7 which I am fortunate to have in my possession. This beautiful compact double swing Universal camera has a square polished mahogany camera box and features extra-long leather

bellows, a reversible back for horizontal or vertical views, and brass rack and pinion movements for smooth focusing. In 1893 the camera, without lens, cost $38 and came with a long canvas carrying case, a combination sliding and folding tripod, and one Perfection Double Plate Holder.8 Walter’s Universal camera is fitted with an unmarked 2¾ inch lens with a rotary stop brass Prosch Duplex pneumatic shutter operated by an attached rubber air bulb for timed or instantaneous exposures.9 While the shutter is marked “Duplex” on the front, it is identical to the newer Prosch Triplex shutter advertised in

photography catalogs.10 The earliest Walter could have purchased this model of the Universal camera would have been in 1893, when the camera first appeared in the Rochester Optical Company catalogs.11

Walter did not have a photography studio in Mount Pleasant, but he did build a darkroom in an unfinished part of the second floor in the rear of the farmhouse where he could load the dry glass-plate negatives into the plate holders and develop them after exposure. He also used Scovill cherry wood printing frames to make contact prints, probably

after exposing the negative and sensitized paper to sunlight, which was the practice at that time. Since Walter did not have a studio, only three of the glass negatives retained by the family have portraits of a single sitter, including his parents, and three of families. These portraits were photographed in the unfinished part of the farmhouse with a simple white background hung on the brick wall.

Walter’s gelatin dry glass-plate negatives were not properly cataloged, so there is limited information on the dates when the images were taken, the identity of many of the people shown, and

frequently the location. Nor were the negatives properly handled and stored, so the gelatin emulsions on some are damaged, showing scratches and chips. Yet the large format of the glass negatives has enabled the printing of exceptionally detailed images that are a valuable historic record. When the farm was sold in 1970, many of the negatives were retained by family members with the intent of preservation, although I remember that negatives with images of farm animals and other images were unfortunately not saved. The glass-plate negatives that were retained can be divided into two groups: negatives with images from Walter’s travels in the United States (Washington, D.C., Richmond, Virginia, and Florida), and negatives with a diverse group of interesting images of family, friends, and other people and scenes mostly in and around Mount Pleasant.

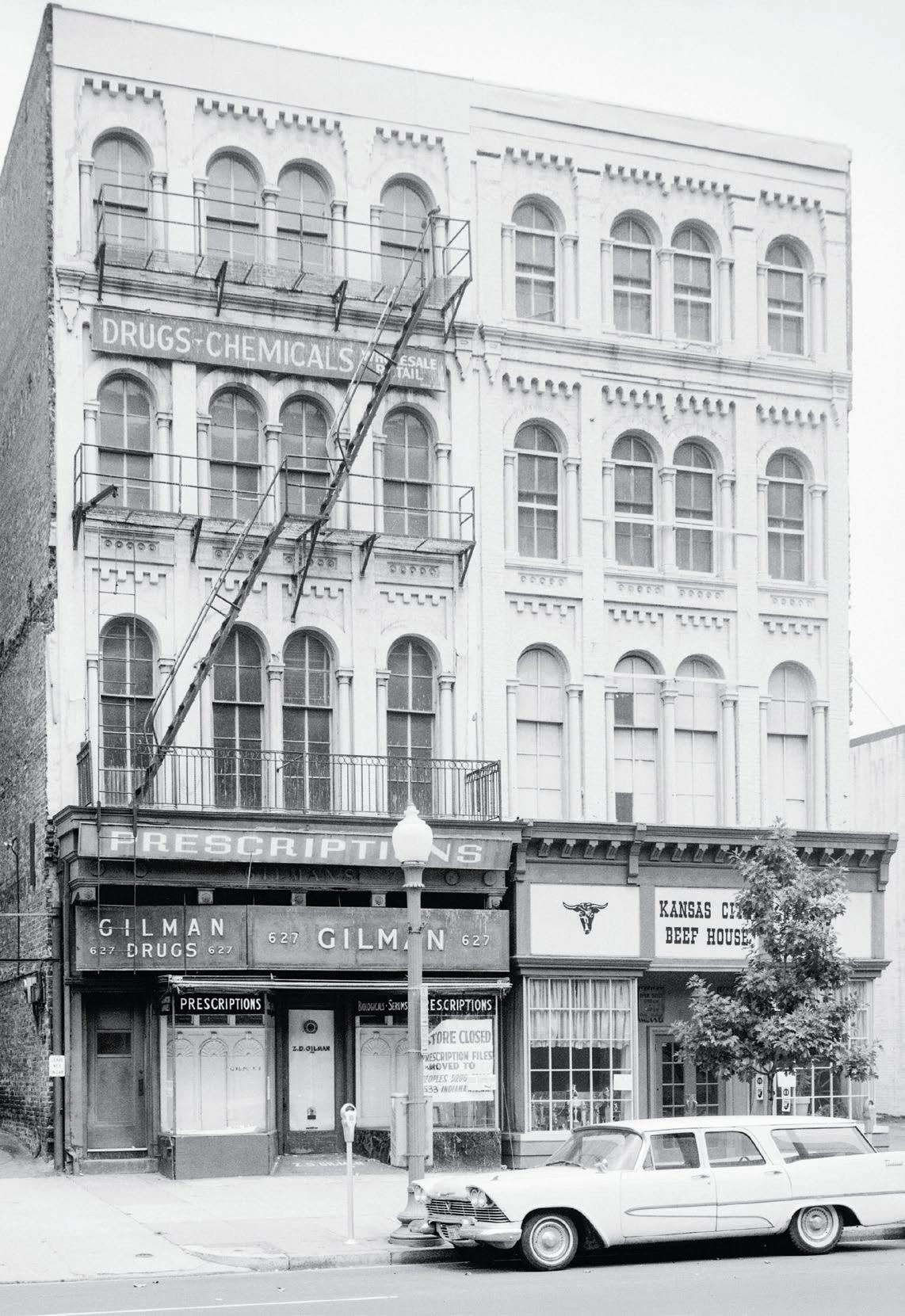

The most interesting of Walter’s travel images are the twenty-eight from his trip to Washington, D.C. They provide an extraordinary glimpse of the nation’s capital during the late nineteenth century. All were taken during the winter, since Walter would have had farm responsibilities during the rest of the year. He photographed many of the historic landmark buildings in Washington at that time, including the White House. To ascertain exactly when Walter visited Washington, I researched the dates when buildings he photographed were constructed. The Arlington Hotel was expanded in 1889,12 and in Walter’s image of the hotel the new addition was just being completed. That would place Walter in Washington during November and December 1889, when President Benjamin Harrison was residing in the White House.

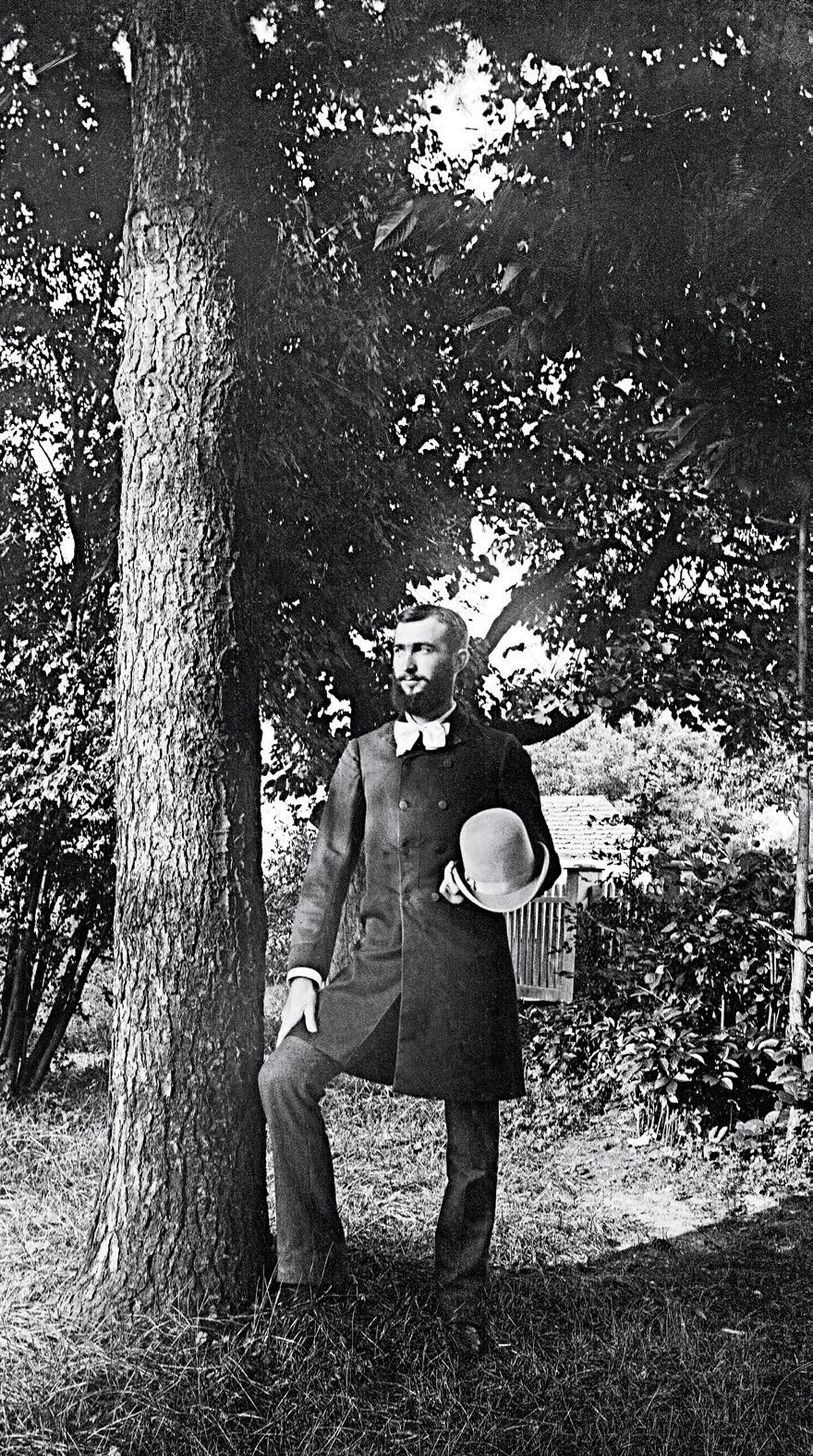

There are two great images of the White House in Walter’s negative collection. One image of the east end of the White House and the fountain at the steps leading to the White House Grounds was taken from the East Executive Avenue, next to the Treasury Building. The other is in the series of seven truly outstanding panoramas of Washington that Walter captured through the rectangular pyramidion windows positioned around the observation deck at the top of the Washington Monument. I find these to be the most fascinating of the Washington images, for the perspective they provide.

The White House is at the center of one of seven panoramic views captured by Walter Hussey from the small windows on the observation deck at the top of the Washington Monument in 1889. The sprawling Conservatory complex, which would be replaced with the West Wing in 1902, extends from the west end of the house. The surrounding neighborhood, filled with low-rise brick structures and dotted with church spires, remains largely residential. Many of these city blocks would soon be replaced with office buildings as the city evolved to house the growing federal government.

These images made me wonder how my grandfather managed to carry the bulky large-format camera (this was before he purchased the portable Universal camera) and the necessary accessories (tripod, several extra double-plate holders loaded with glass-plate negatives, etc.) up the 898 steps to the observation deck of the Washington Monument. However, I learned that a steam-powered hoist was built inside the shaft in 1880 to transport building materials while the obelisk was being constructed. After the Washington Monument was dedicated in February 1885, the hoist was converted to a passenger elevator before it was open to the public in October 1888. Thus Walter would have been able to use the elevator to ride to the observation deck with his photography equipment to take these rare early panoramic images. In the striking photograph shot to the north of the monument, the imposing State, War and Navy Building (completed in 1888)

and the Treasury Building are prominently visible flanking the White House. Other significant historical landmark buildings can be identified: the Shepherd Mansion at Connecticut Avenue and K Street NW, the Corcoran and Hay-Adams Mansions on H Street NW across from Lafayette Park, and the Arlington Hotel on Vermont Avenue and Eye Street NW. Many of these have since been demolished. 13 The White House Conservatory complex is clearly visible on the west side of the White House. The first greenhouse was built by President James Buchanan in 1857, and several more greenhouses were added through the years under different presidents. The Conservatory complex was removed in 1902 during the White House renovation under President Theodore Roosevelt, to be replaced by an executive office building that eventually would become the present-day West Wing. The U-shaped building surrounded by trees,

A detail of the panorama pictured on the previous spread reveals long since demolished landmarks in the President’s Neighborhood including the Corcoran and Hay-Adams Mansions on H Street across from Lafayette Park. Also seen here (in the lower left corner of the photograph just south of the State, War, and Navy Building) is a rare view of the brick horse stable built for President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871.

with the entrance gate facing Seventeenth Street NW just south of the State, War and Navy Building, is the last White House horse stable built in 1871 for President Ulysses S. Grant.14 In the great panoramic image with the U.S. Capitol, the Smithsonian Castle and Arts and Industries Building and the first Department of Agriculture Building are the only buildings on what was to become the National Mall. The enormous Center Market15 on B Street NW (renamed Constitution Avenue in 1931), covering two blocks between Seventh and Ninth Streets NW, and the large Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station16 at Sixth and B Streets NW are also clearly visible in this image.

Among the other Washington images captured on Walter’s glass negatives are three images of the East Front of the stately U.S. Capitol after a recent snowstorm, including a closer view of the Capitol dome. Another negative has the image of the James

A. Garfield statue in the circle at First Street and Maryland Avenue SW, with the West Front of the U.S. Capitol in the background. An interesting image of the South Front of the Patent Office Building shows pedestrians buying food bags for 10 cents from vendor carts on the corner at Seventh and F Streets NW. Walter’s interest in this building might have stemmed from his father being an inventor who was granted three U.S. patents. Another great image is a northwest scene up the wide Pennsylvania Avenue NW from Second Street NW showing several horse-drawn streetcars and buggies, which were the common modes of transportation in Washington at that time. Any moving streetcars and buggies are blurred in this image, since this photograph was a timed exposure, taken with Walter’s view camera that used the lens cap as a shutter.

above

Hussey’s photograph of the luxury Arlington Hotel following its 1889 expansion helped the author date the glass negative collection. From 1868 to 1912, the hotel stood just northeast of the White House at the present location of the Veterans Administration Building.

left

Hussey’s photograph of the south front of the Treasury Building would be difficult to capture today as the area is now within a secured perimeter.

above Street vendors can be seen selling food from their carts to passing pedestrians in Hussey’s photograph of the Patent Office Building, 1889.

John Quincy Adams Ward’s statue of President James A. Garfield, which was unveiled in the circle at First Street and Maryland Avenue SW in 1887, is seen in the foreground of Hussey’s photograph of the west front of the U.S. Capitol.

The second group of images from Walter’s glassplate negatives provides an exceptional and important visual history of his family and friends and a glimpse of life in Mount Pleasant primarily in the late 1880s and the 1890s, although additional family images were taken in the early 1900s. These wonderful images include several large gatherings of friends of Walter’s on outings in the woods with musical instruments or wooden tennis rackets. I was struck by how formally the men and women were dressed for an outing in the woods—the men in three-piece suits and derby hats, and the women in long dresses with hats of various sizes, many adorned with flowers. One truly fascinating image shows seven couples dancing to music provided by a quartet consisting of three string players (two violin and one string bass) and a clarinet player on a large wooden “dance floor” that was assembled in the woods. Children watching the couples dance can be seen under trees in the background. In one of Walter’s best artistic images, and my favorite, he has twenty formally dressed men and

women posing around a small pond, with four on a small boat and others on a bridge or at the water’s edge, some holding wooden tennis rackets and one with a fishing rod.

Examples of other interesting Mount Pleasant images in the Smithsonian’s Walter J. Hussey collection are images of formally dressed family and friends in different poses in the parlor of the Hussey farmhouse, Quaker friends staying at the Hussey farm while attending the six-day Ohio Yearly Meeting held in Mount Pleasant Yearly Meeting House , friends riding in horse-drawn sleighs after a snowstorm, a classroom heated by a potbelly stove in a one-room country schoolhouse with several grade levels of students being taught by one schoolmaster, men riding in horse-drawn buggies and high-wheeled sulkies, and several farm scenes.

I must mention that my grandfather was a skillful artist as well. Two of his landscape paintings were hanging on the wall in images Walter took of guests in the parlor in the farmhouse. However, I do not know the whereabouts of any of his paintings. While Walter did not have a studio in Mount

Many of Walter Hussey’s photographs are set in rural Mount Pleasant, Ohio. Included in the collection are outdoor gatherings of his formally dressed friends dancing in the woods (opposite) and posing (right and below).

Pleasant, I have one mounted photograph of Walter at age 26 painting a winter landscape with a young couple looking over his shoulder at a studio that is believed to be in DeLand, Florida, in 1891. Two finished landscape paintings and a man’s portrait are also visible in this photograph. I have not been able to confirm that Walter had a studio in DeLand, but that is what the handwritten label and date on the photograph say.

Most of all, my grandfather was a very successful farmer. Farming was his livelihood, and it supported his family.17 In 1893–94, at age 28, while he was still very involved with his photography, Walter embarked on building a sizable registered American Jersey dairy herd around the famous St. Lambert Jersey family by buying thirty registered Jersey cows from different breeders in the Northeast. He also bought one of the best pure St. Lambert bulls in the world to be head of his

left

Walter Hussey paints a landscape while a couple admires his work in a studio in DeLand, Florida, c. 1891.

below

Walter Hussey (standing far right) poses at the front porch of the Hussey farmhouse with three generations of his family in 1911. Hussey’s parents (the author’s great grandparents) are standing at far left. Hussey’s son John (the author’s father) is the second child on the right.

Walter Hussey strikes a pose in the front yard at the Hussey Greenwood Farm, 1890.

herd. Thereafter, Walter soon became a prominent breeder of Jersey dairy cattle and was elected into the prestigious American Jersey Cattle Club in 1895. The previous year Asahel, Walter’s father, was granted a patent for a cow-milker that could have been used to milk the Jersey dairy cows. In a letter my father sent to his grandfather, Asahel, in 1916, he wrote, “We still are milking 25 to 30 cows and ship cream to Steubenville.” However, sometime around 1920, Walter switched to raising Hereford cattle, and that was the breed raised on the farm while I was growing up.

My grandfather lived on the Greenwood Farm until October 5, 1959, when he passed away at the age of 94. He was a skilled amateur photographer whose glass negatives leave a rich visual record of the nation’s capital and life in and around Mount Pleasant, Ohio, during the late nineteenth century. To permanently preserve his negatives, I donated eighty-four glass-plate negatives to the

Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in 2010. At the museum the glass negatives are stored under archival conditions, and they have been digitized to become a permanent record in the Photographic History Collection.18 My grandfather’s legacy to his descendants lives on in this collection, and now the public can view the breadth and quality of his photography.

1. J. A. Caldwell, History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties, Ohio and Incidentally Historic Collections Pertaining to Border Warfare and the Early Settlement of the Adjacent Portion of the Ohio Valley (Wheeling: Historical Publishing Company, 1880), 530–40.

2. James L. Burke and Donald E. Bensch, Mount Pleasant and the Early Quakers of Ohio (Columbus: Ohio Historical Society, 1975), 8–9.

3. Ibid., 12–22.

4. Caldwell, History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties, Ohio, 561.

5. Ibid., 543–44.

6. For example, J. Traill Taylor, The Photographic Amateur: A Series of Lessons in Familiar Style for Those Who Desire to Become Practically Acquainted with This Useful and Fascinating Art, 2nd ed. (New York: Scovill Manufacturing Company, 1883); W. F. Carlton, The Amateur Photographer: A Complete Guide for Beginners in the Art-Science of Photography (Rochester: Rochester Optical Company, 1891). This guide was included with each Rochester Optical Company camera purchased.

7. Catalogue of Photographic Apparatus (Rochester: Rochester Optical Company, 1893), 4–5.

8. Ibid.

9. How to Make Photographs and a Descriptive Catalogue (New York: Scovill and Adams Company, 1892), 83–86.

10. Ibid.

11. Catalogue of Photographic Apparatus, 4–5.

12. “The Opulent Arlington Hotel,” Streets of Washington, www. streetsofwashington.com; James M. Goode, Capital Losses: A Cultural History of Washington’s Destroyed Buildings, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2002), 209.

13. Goode, Capital Losses.

14. Herbert R. Collins, “The White House Stables and Garages,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol 63–65 (1963–65): 366–85; Frank G. Carpenter, “Our Presidents as Horsemen,” Magazine of American History 17 (June 1887): 483–93.

15. Goode, Capital Losses, 302–03.

16. Ibid., 454–55.

17. J. H. Andrews and C. P. Filson, Centennial Souvenir of Steubenville and Jefferson County, Ohio, 1797–1897 (Steubenville: Harald Publishing Co., 1897), 199.

18. The Walter J. Hussey Collection (accession number 2010.0080, now 154 images) is accessible online via the Smithsonian home page, www.si.edu. At this site the images can be zoomed in to observe detail. The author wishes to acknowledge Jane Fraelich, who gifted him Walter’s Universal camera; Shannon Perich, associate curator of the Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, who coordinated the donation of Walter’s glass negative collection to the Smithsonian; John Dillaber, photographer, Smithsonian Photographic Services, Photographic Archives Division, who digitized the negatives; and John Hussey and the Mount Pleasant Historical Society for donating glass negatives to the collection.

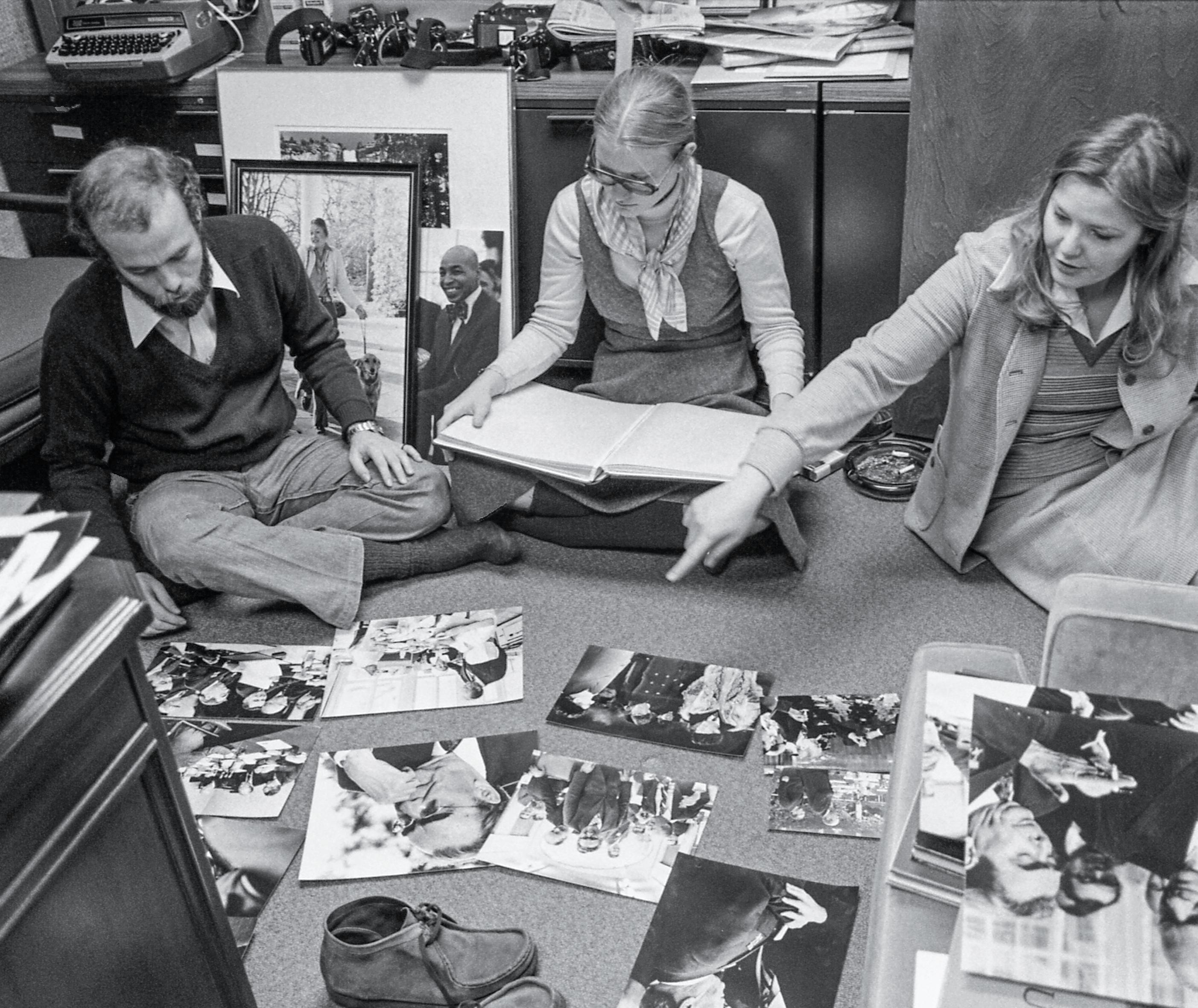

one important lesson i have learned from covering the White House for more than three decades is that some important windows into the presidency are hidden in plain sight. One example is the special role played by White House chief photographers. They are not only visual historians but also keen observers of presidential behavior who possess many insights about the leaders they worked for and how their White Houses operated.

I have known all the chief photographers who served during my time on the presidential beat, since 1986. They scurry and clamber behind the scenes at both public and private events, usually with several cameras hanging from straps around their necks, snapping pictures furiously and almost always from the best vantage points, trying to remain unobtrusive yet close to the action. They are talented professionals and wonderful resources for the country, especially because of their amazing access. As I wrote in my book on White House photographers:

In fundamental ways, official photographers have morphed into presidential anthropologists who are allowed to watch, listen, and document visually nearly everything that chief executives do related to their jobs. Sometimes the photographers are

privy to the most profound personal moments, the emotional highs and lows, and the key decisions involving war and peace. Most of the official photographers’ pictures—millions of them—were never released to the public and are stored in the presidential libraries.1

The president’s official photographer, backed by his or her staff, has two roles: first, to visually record the president at official events such as speeches, receptions, receiving lines, and meetings with foreign leaders, members of Congress, and others; second, to provide historical documentation, through photography, of the presidency as an institution and the presidents as individuals. In both roles, the photographers have become the consummate storytellers about life and work at the White House. What does it take to excel as a White House staff photographer? Of course one needs to be excellent at using a camera, but there is something else of vital importance—gaining the trust of the president, the first family, and their staff. The most effective White House photographers do both—mastering their craft and managing to win the trust of the key players. Two other traits stand out: the ability to use photographs to tell stories visually, and not just capture isolated moments, and the ability to be unobtrusive so people, including the president, act naturally, as if a photographer were not there.

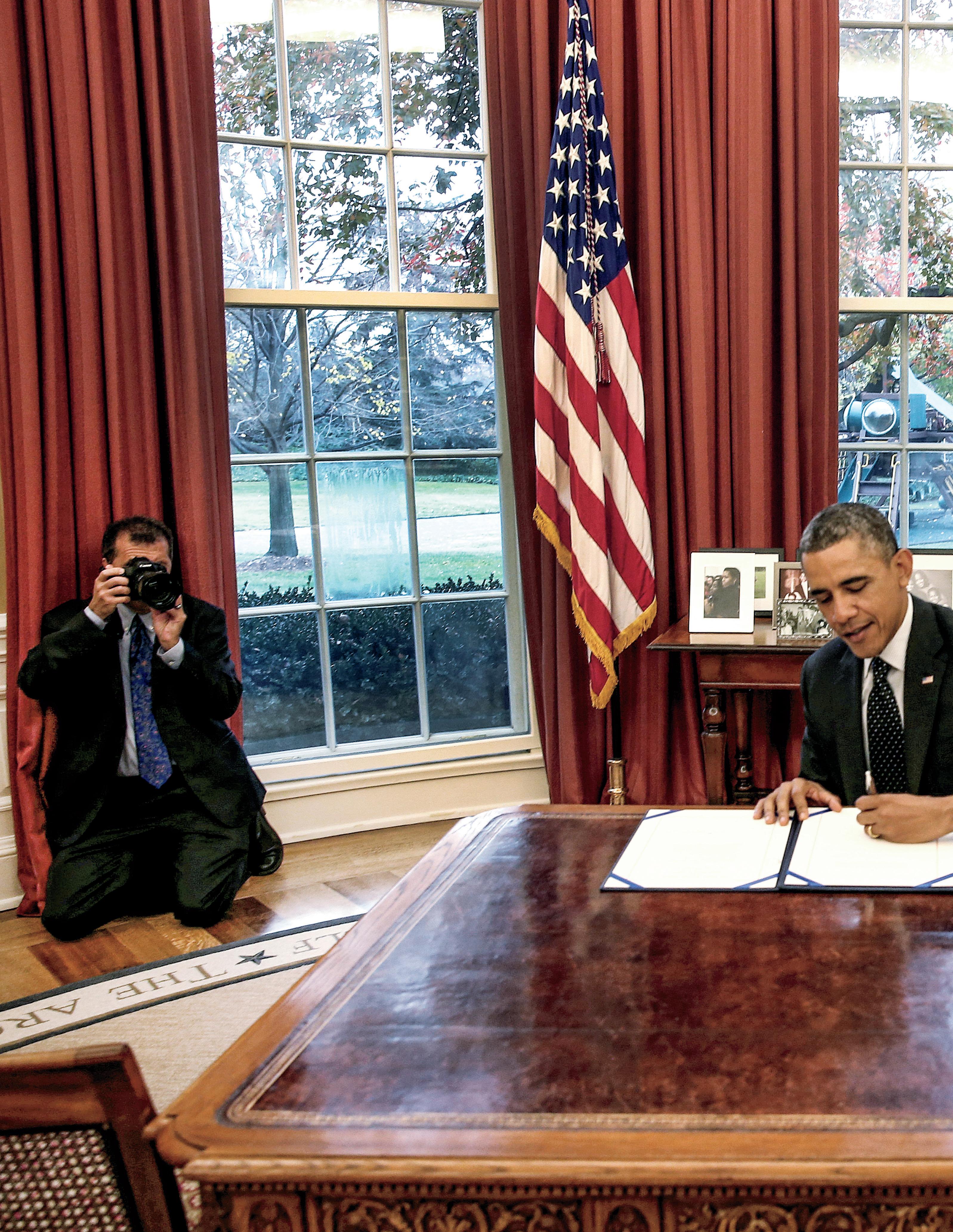

previous

spread

White House Chief Photographer Pete Souza crouches behind the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office to capture images as President Barack Obama signs three bills, November 13, 2013 .

below

Chief Photographer

Shealah Craighead trains her lens on President Donald Trump as he approaches his car, January 26, 2017.

opposite

Chief Photographer

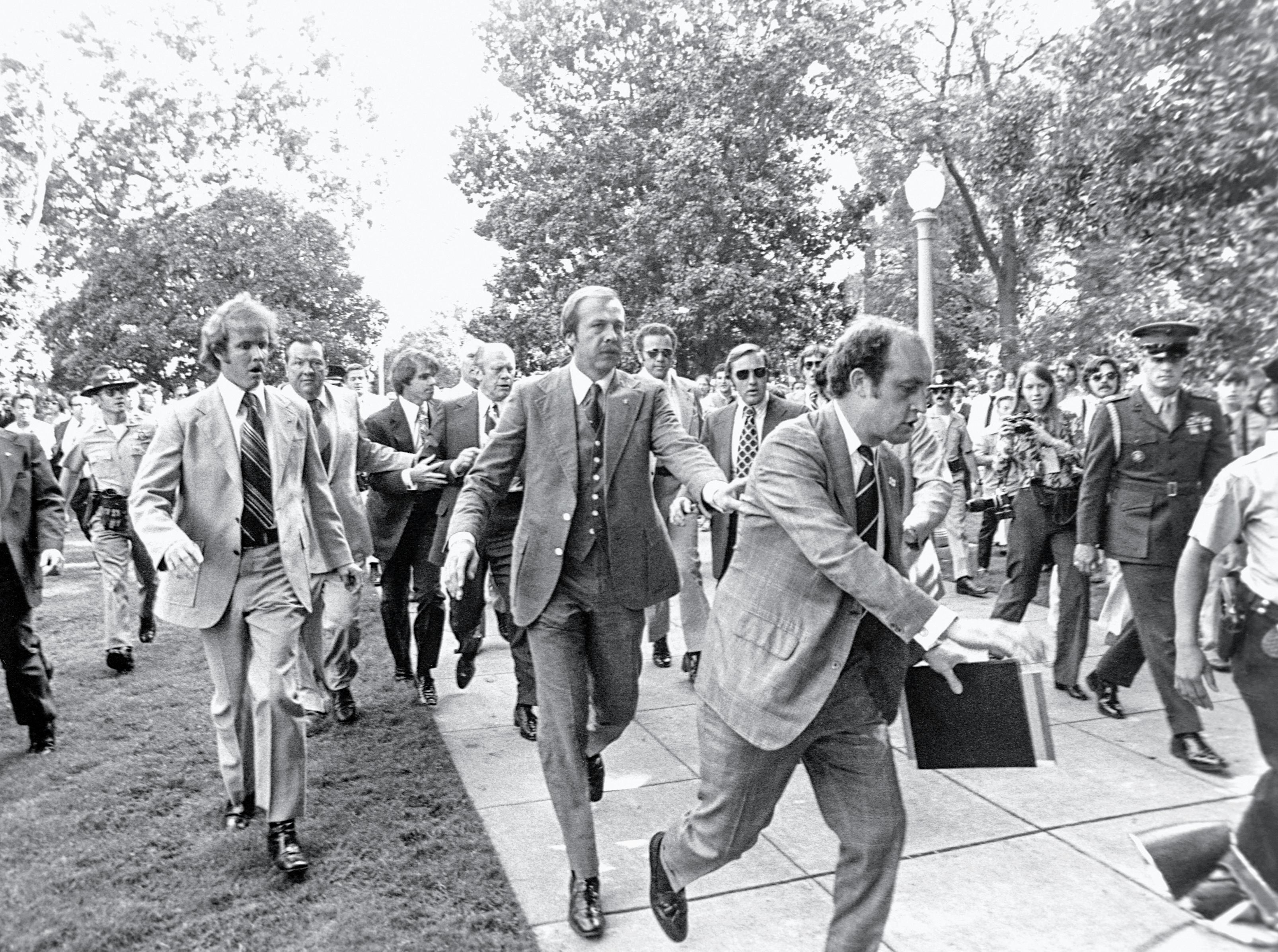

David Hume Kennerly joins President Gerald R. Ford and his entourage as they walk through the West Colonnade.

Franklin D. Roosevelt to John F. Kennedy Administrations 1941–1967

Abbie Rowe (1905–1967) occupies a special place in the history of White House photography. He was a federal employee working on public road projects in the Washington, D.C., area during the 1930s when he saw First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt riding a horse and took her picture. She later saw the photograph and was impressed. She arranged for Rowe to take pictures full time for the National Park Service. In 1941, Rowe was assigned to photograph President Franklin D. Roosevelt at official functions. Rowe was the first photographer to document a president’s official life, such as when he gave speeches and made announcements, attended ceremonies, and met with foreign leaders

and ambassadors.

Rowe was able to bond with FDR because Rowe was disabled by polio, as FDR was, although the president’s disability was much more serious: Roosevelt’s legs were paralyzed. Rowe understood the determination it took to overcome polio, and he also sympathized with the president’s desire to avoid seeming vulnerable or weak because of the disease. So Rowe willingly refrained from taking pictures of the president in a wheelchair or being lifted in and out of vehicles. Rowe stayed on the job for many years, although his talents were largely wasted because he was not given the full range of access that official chief White House photographers later received. Rowe was eventually relegated mostly to taking official photos and adding them, along with news clippings, to scrapbooks. He periodically gave these scrapbooks to President Roosevelt as mementos of life in the White House.2

Best known for documenting the Truman Renovation, photographer Abbie Rowe served four presidents, capturing daily events at the White House for more than twenty years.

left

Shot from behind the president, Rowe’s photograph of Franklin D. Roosevelt speaking at the dedication of the Jefferson Memorial includes FDR’s view of the Marine Band and spectators, April 13, 1943.

opposite clockwise from top left Rowe included his own image in the mirror while documenting a new White House bathroom as the Truman Renovation nears completion, 1952.

The moment President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s grandson David prepared to blow out his birthday candles was captured by Rowe, 1956.

Rowe himself is seen at work (standing at center to left of open doors) covering President John F. Kennedy’s address on the desegregation of the University of Alabama and civil rights, June 11, 1963.

opposite John F. Kennedy Jr. examines the camera of White House Chief Photographer Cecil Stoughton, November 11, 1963.

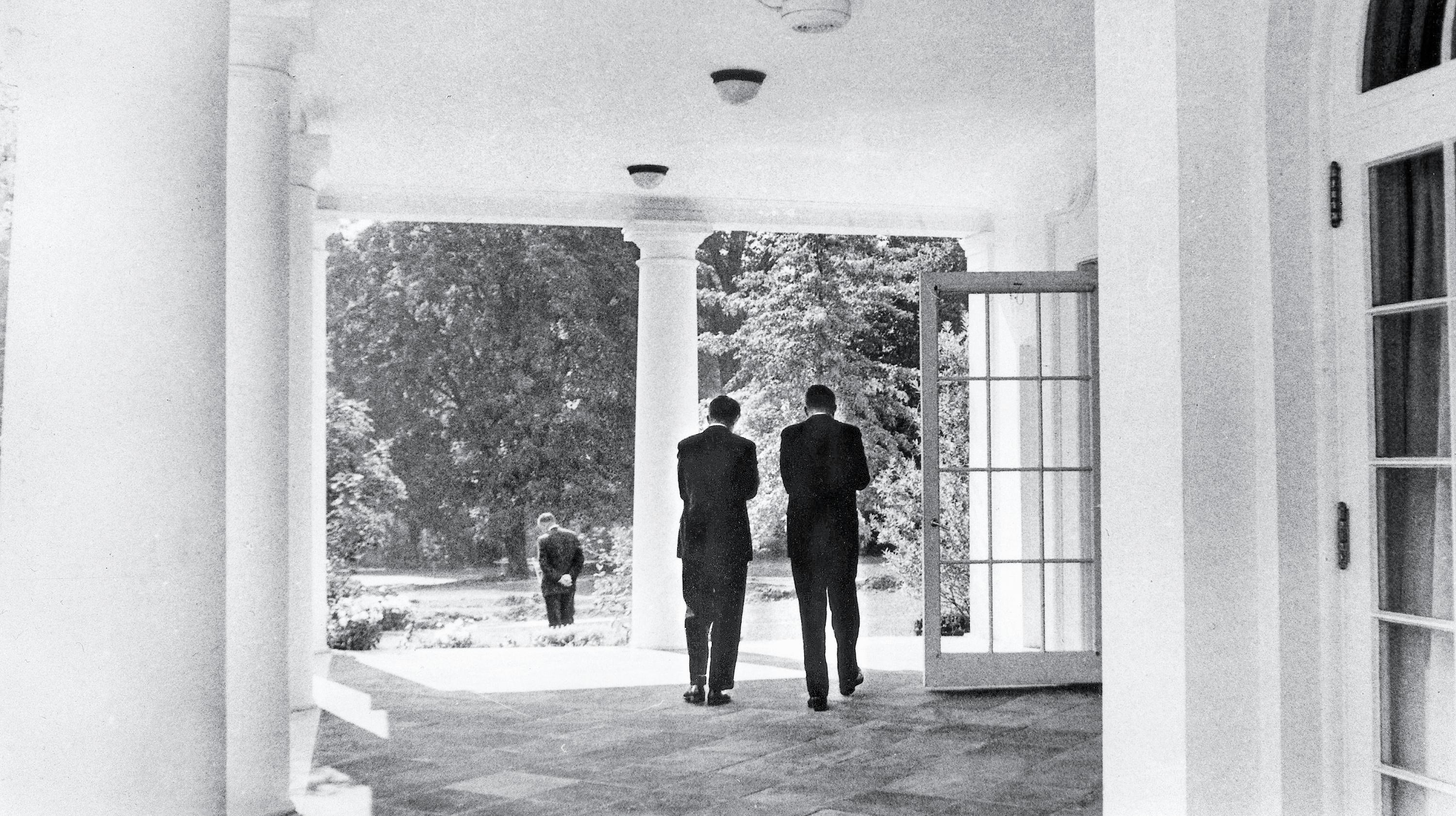

above Stoughton captured President Kennedy deep in conversation with his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, just outside the Oval Office, October 3, 1962.

There have been eleven White House chief photographers. Cecil Stoughton (1920–2008) was the first. President John F. Kennedy named Stoughton, then an army captain, to the photo job at the beginning of his administration in 1961 because he wanted a personal and public record in photographs of his time in office, which Kennedy expected would be historic.

Stoughton had some clever techniques for gaining access. One was to teach John Kennedy Jr. how to use cameras. The boy would later look at his pictures, provided by Stoughton, with delight and show them proudly to his dad and mom. A bond was formed between the pro and the kid, who had trouble pronouncing Stoughton’s name and called him “Captain Tau-ton.” But he always looked forward to seeing Stoughton, and their connection helped expand the captain’s access.

Kennedy also had warm friendships with news and commercial photographers, such as George Tames of the New York Times. He once gave Tames remarkable entre to the Oval Office during a photo

shoot about a day in the life of the president for the Times Sunday Magazine. At one point, Tames noticed Kennedy standing at a window with his back to the room, leaning over a desk. Tames captured the moment. It seemed like the weight of the world was on the young president’s shoulders, and Tames titled the photo “The Loneliest Job.” But the title does not describe what was happening. Kennedy was simply reading a newspaper standing up to ease the chronic pain in his back. The photo took on a life of its own, and it still is considered an iconic image of a solitary decision maker.

It was Stoughton who took the famous photo of Lyndon B. Johnson being sworn in aboard Air Force One after Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963—possibly the most famous presidential photo ever made. Johnson wanted the photo taken aboard Air Force One to show that the constitutional succession of power was intact and he would continue the Kennedy legacy. Stoughton got to the plane just in time, but his usually reliable Hasselblad camera failed at a key moment. “I almost died,” he recalled later. But he managed to push in a loose connector and this did the trick. Stoughton captured the swearing-in, and the pictures were used around the world.3

Yoichi Okamoto (1915–1985) followed Stoughton in the chief photographer’s job when Lyndon Johnson took over after Kennedy’s assassination. LBJ did not like Stoughton’s pictures of him, considering them inferior to the photos that Stoughton took of Kennedy. As vice president, Johnson had known Okamoto, and he liked the photographer’s work. Johnson quickly moved “Oke” from his job as director of photography at the United States Information Agency (USIA) and reassigned him to the White House as official photographer. (Stoughton was reassigned to the National Park Service.)

Okamoto was born in 1915 to Japanese American parents in Yonkers, New York. He graduated from Colgate University and worked for several years as

a photographer for the Post-Standard in Syracuse. He served as a photographer with the U.S. Army Signal Corps in Europe during World War II. He eventually moved to the U.S. Information Service, which became the USIA, and covered Johnson photographically when he visited Europe as vice president.

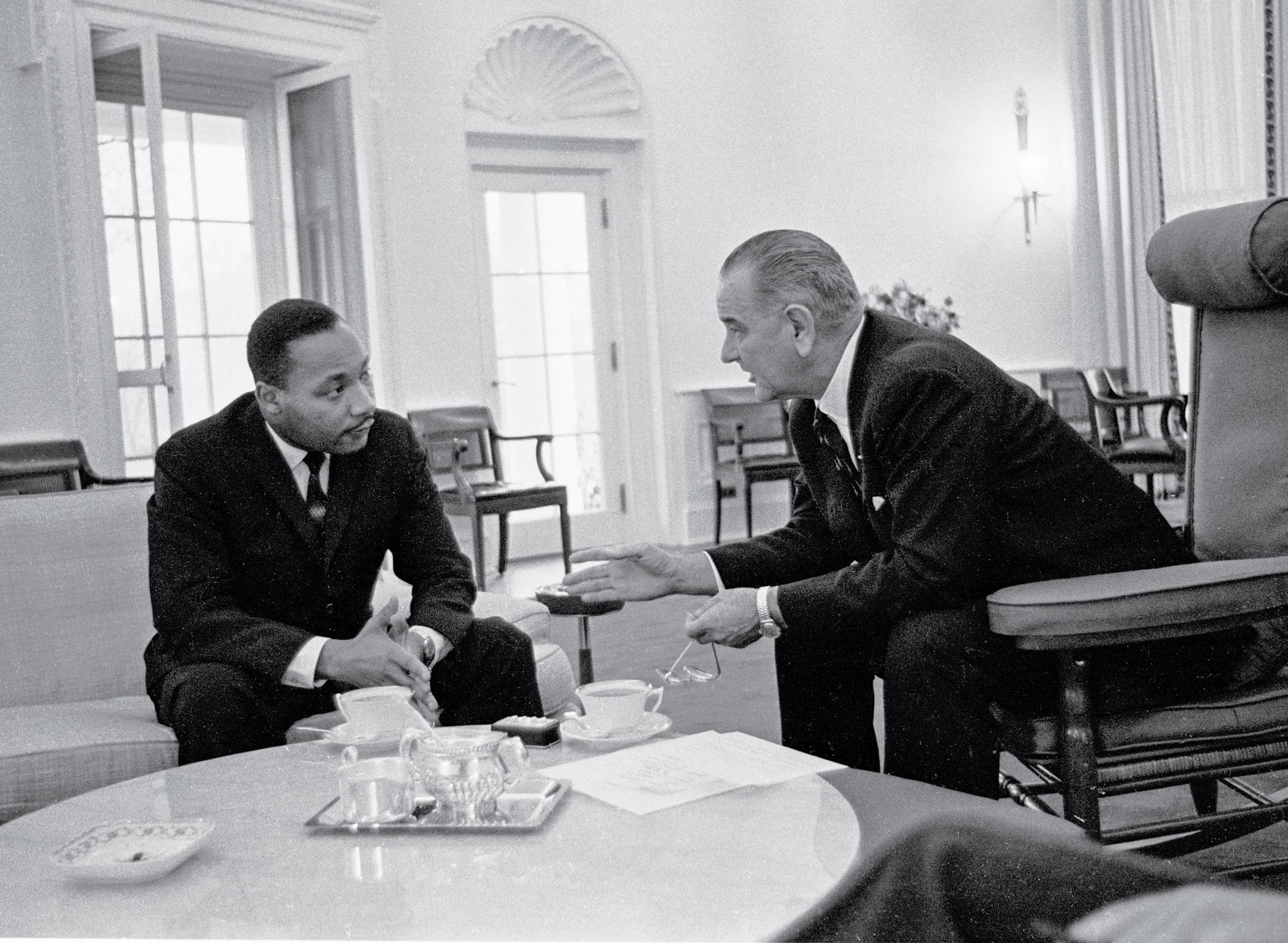

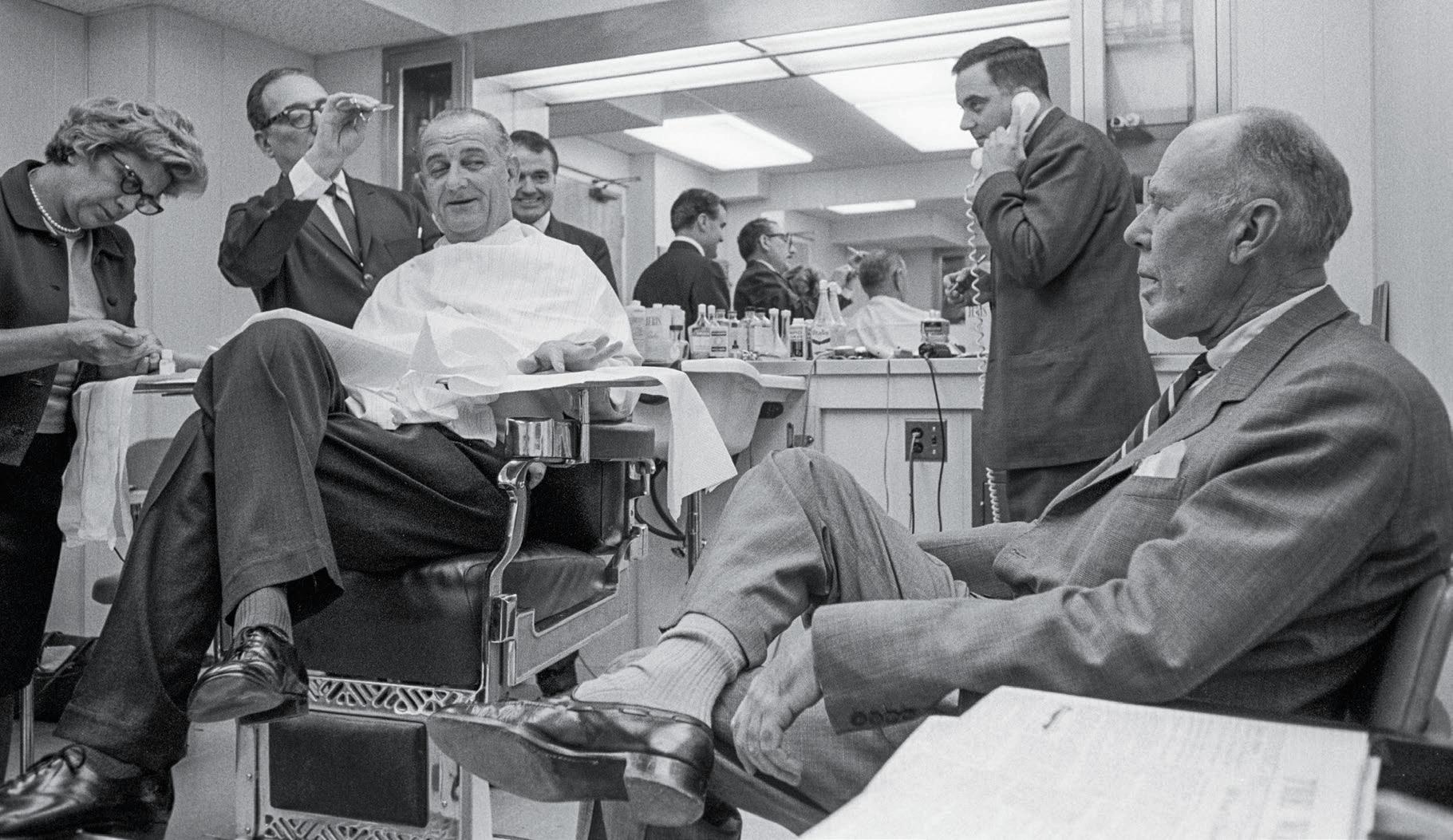

Among Oke’s photos of LBJ as president were his striking images of Johnson meeting with the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., getting a haircut, and lobbying members of Congress in his intimidating style. He once gave some advice to David Kennerly as Kennerly was about to become President Gerald Ford’s photographer. “You got to just be there all the time; 16 hours a day,” Oke said. “That’s how you’re going to get the good pictures. . . . There’s only so much time you’ll be in that job. “You’ll never have another opportunity like that.”4

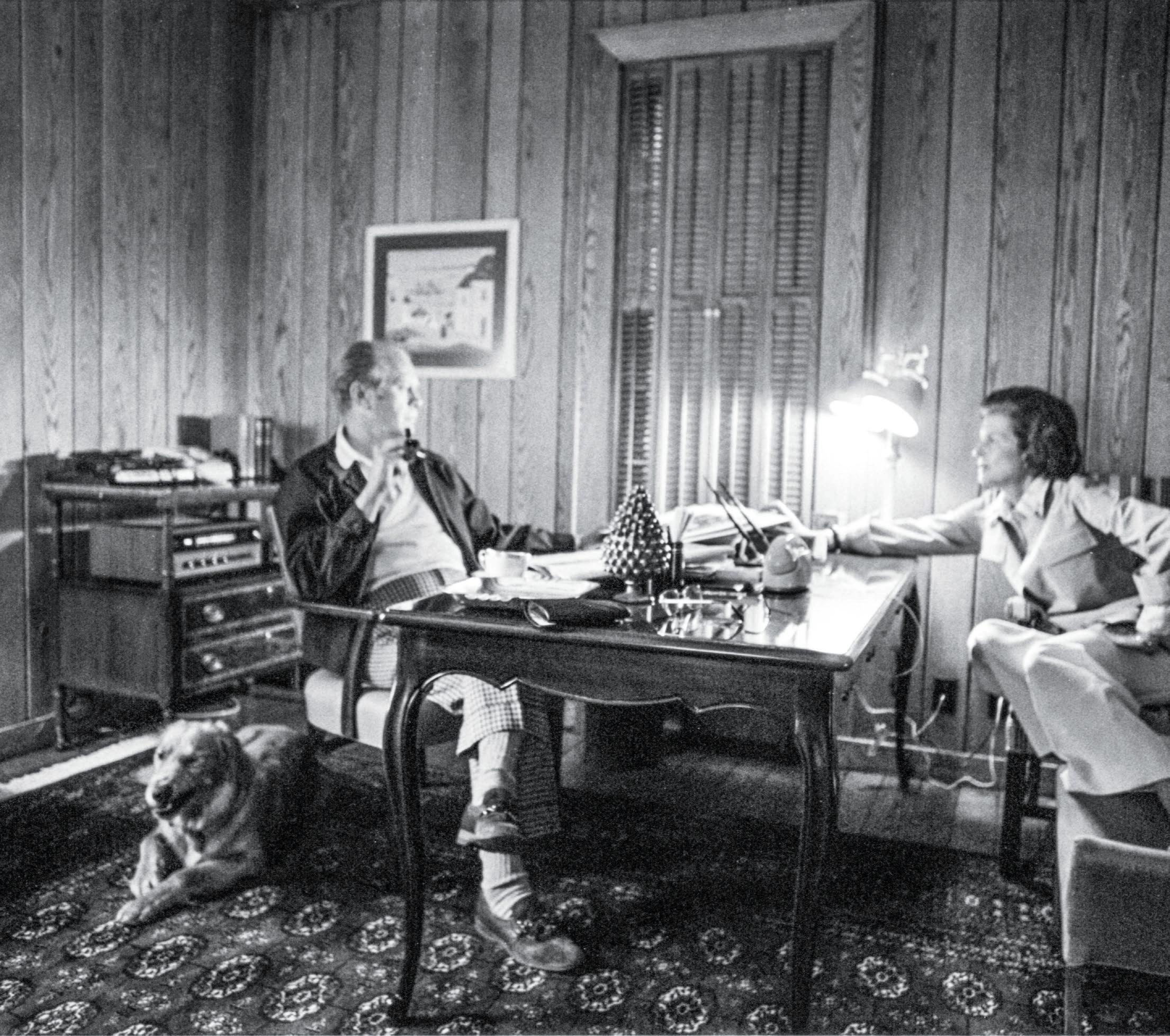

With the help of a mirror, Yoichi Okamoto includes himself in an image of a meeting held in the living room of President Lyndon Johnson’s Texas ranch, January 2, 1964.

In two of Okamoto’s most memorable images, LBJ meets with Reverend Martin Luther King in the Oval Office, December 3, 1963 (above), and gets a haircut while conducting business, April 26, 1966 (right).

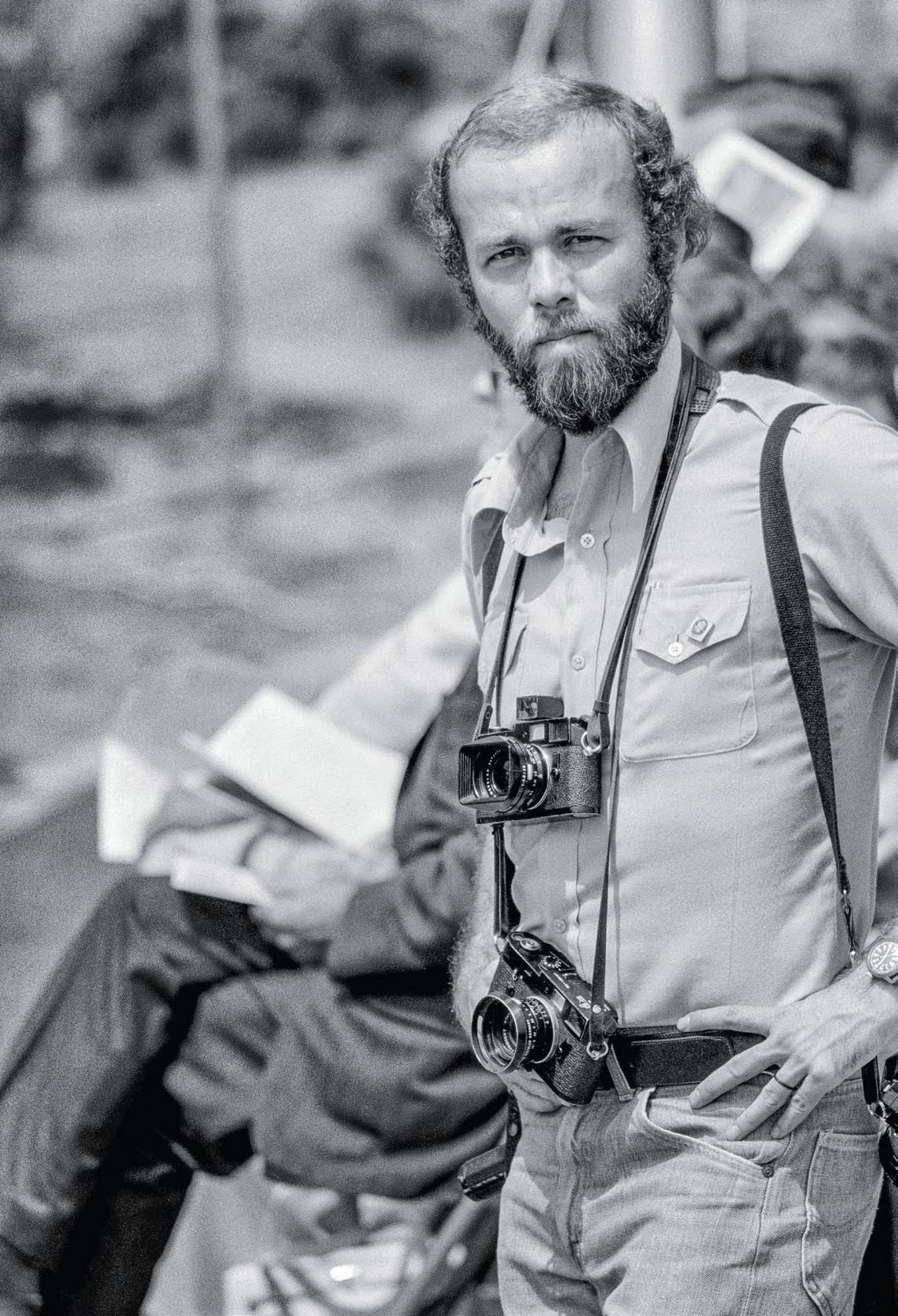

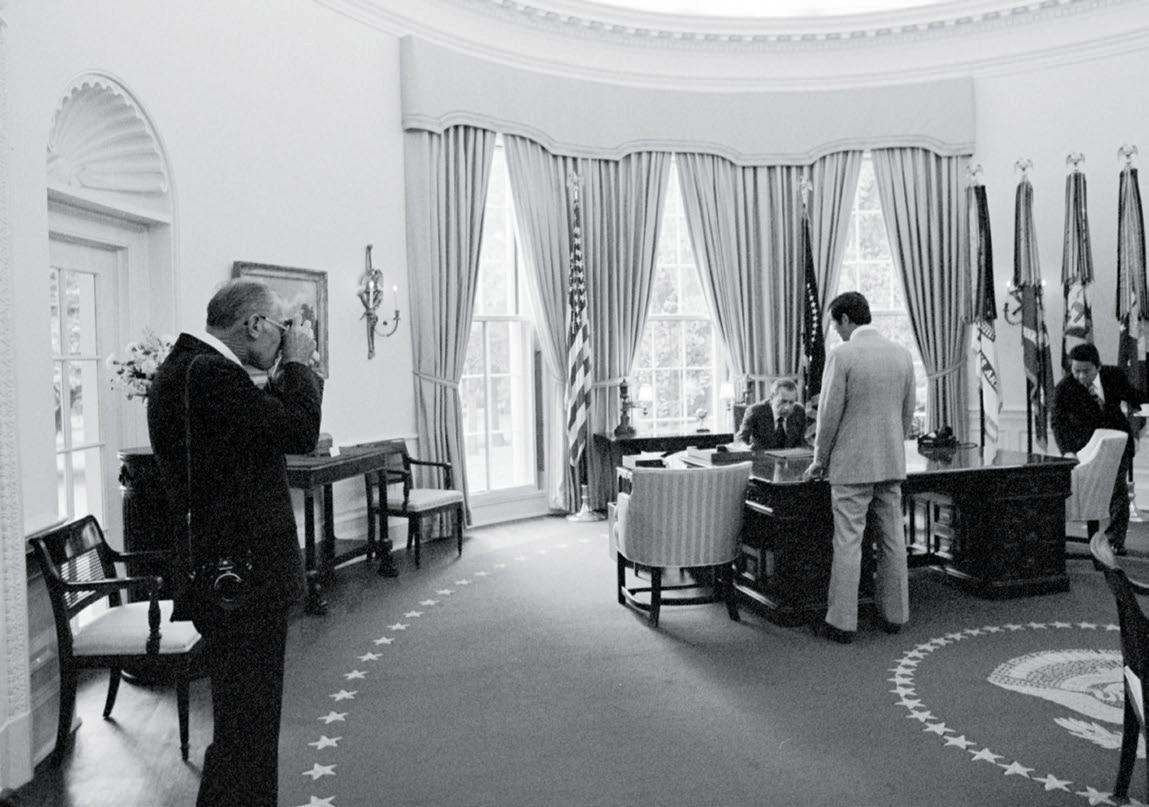

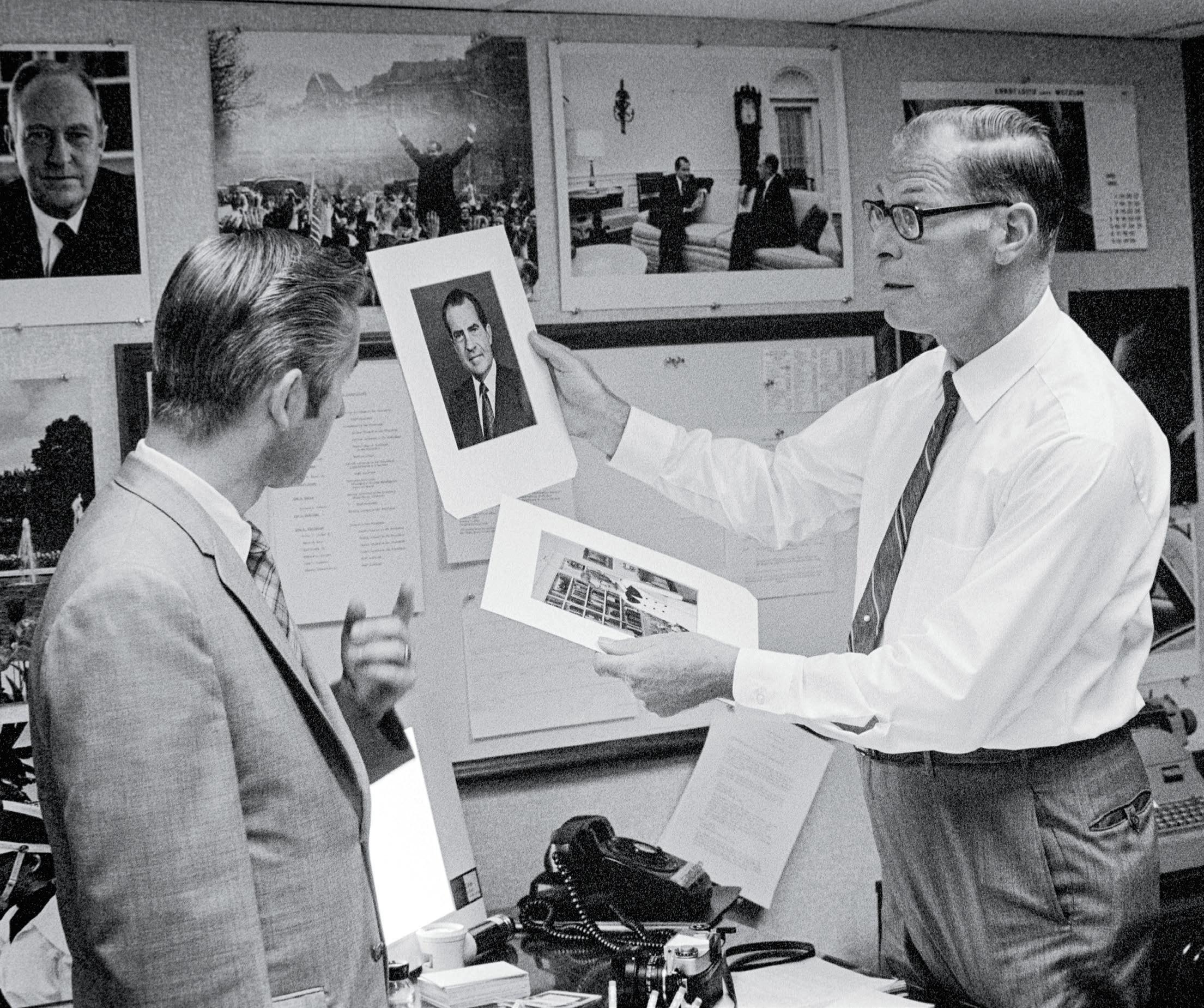

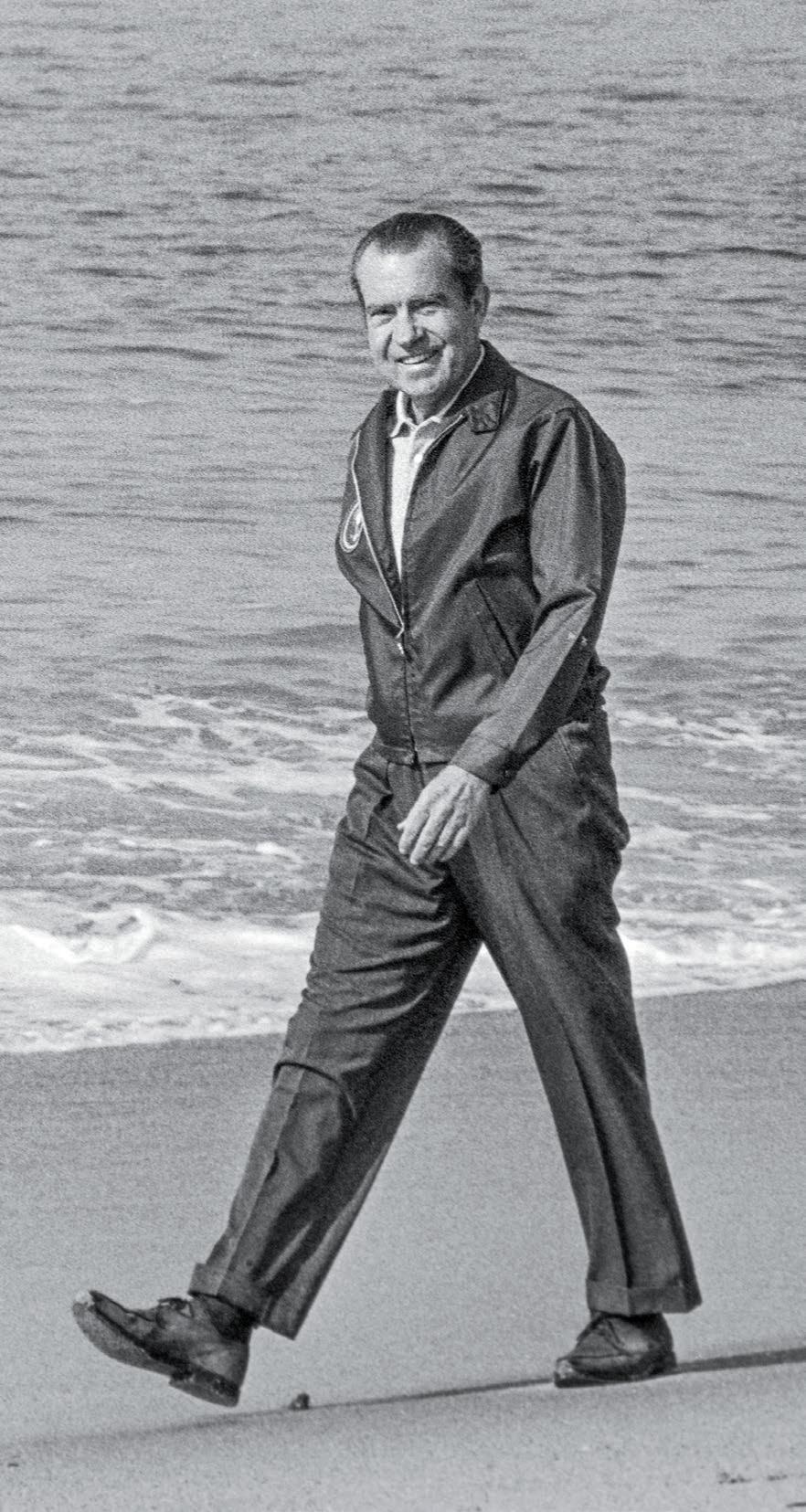

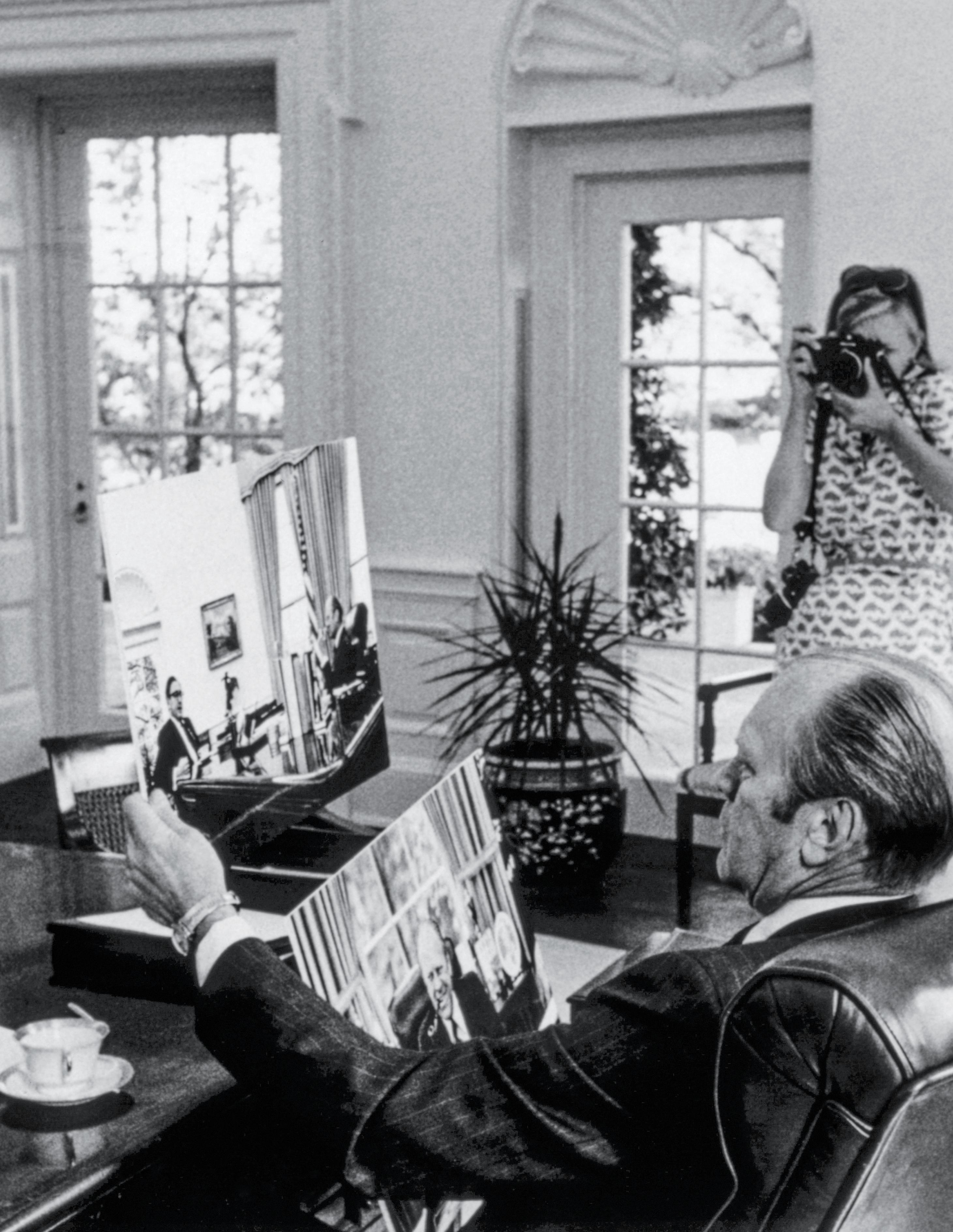

Ollie Atkins (1917–1977) was a former Saturday Evening Post photographer who had also worked for various newspapers. He had taken pictures of Presidents Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy, so he knew his way around the White House. He was named Nixon’s campaign photographer during his successful 1968 campaign. It was a natural step for Nixon to name Atkins as his White House chief photographer when he took office in 1969 since the new president knew Atkins well and trusted him, up to a point.

But Nixon was skeptical that photos would be a political benefit, and he gave Atkins a rule: “Six and

out.” This meant Atkins could take six photos and then would have to leave the room. Nixon would listen for the frames to click off on Atkins’s camera and then nod for him to leave, sometimes in a dismissive way as if Atkins were a nuisance. Atkins was regularly frustrated by not being able to get enough access to take more appealing pictures of Nixon.

Ollie Atkins poses with his camera while traveling with President Richard M. Nixon, September 30, 1972.

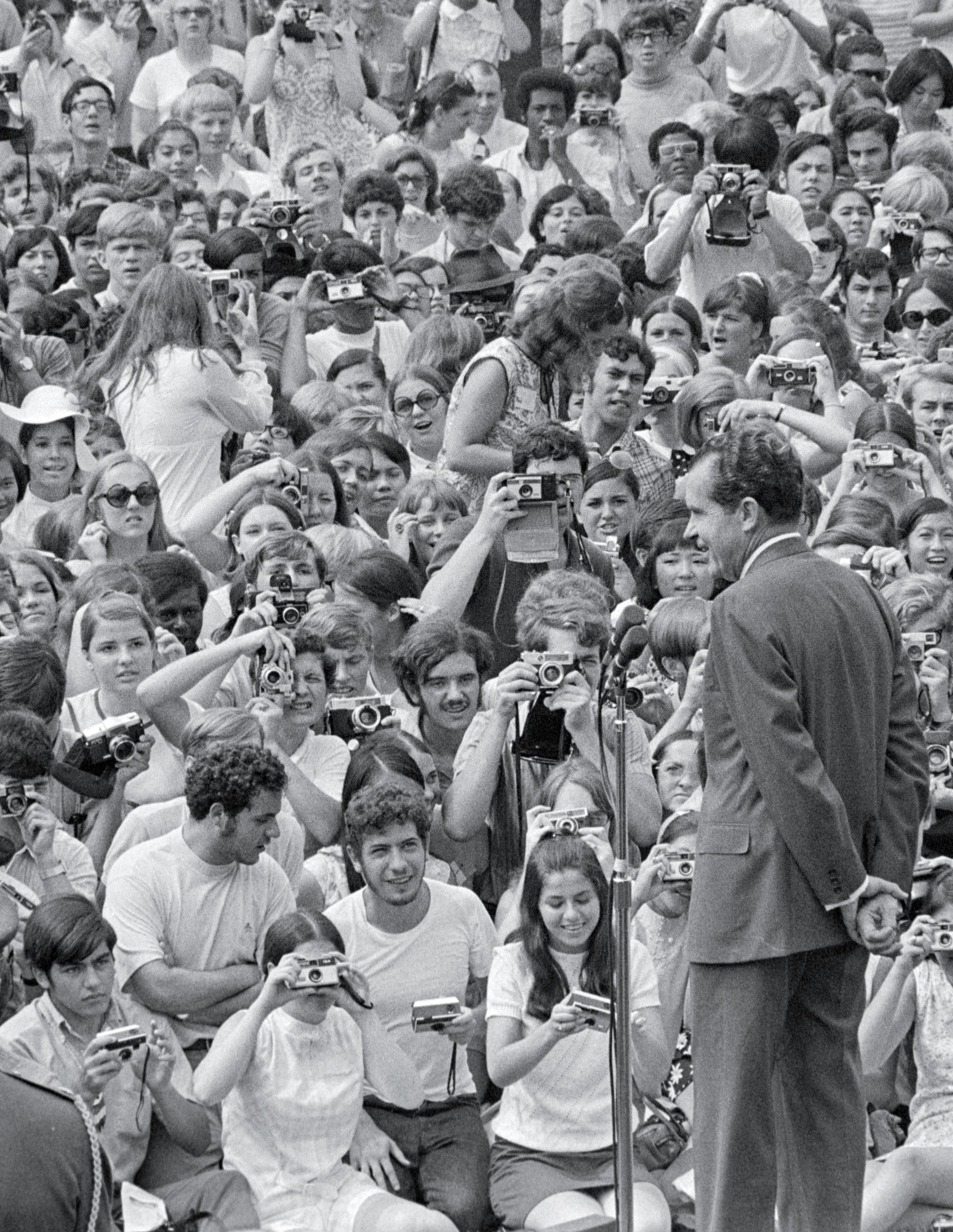

Atkins captured Nixon on the campaign trail in 1968 before being named official White House photographer.

above left

In this photograph of President Gerald R. Ford at work in the Oval Office, Liberty, a golden retriever adopted by the Fords, looks at the camera as she keeps the president company, November 1974.

above right

David Kennerly waits to photograph President Ford speaking at a newly opened Vietnamese refugee center in Arkansas, August 10, 1975.

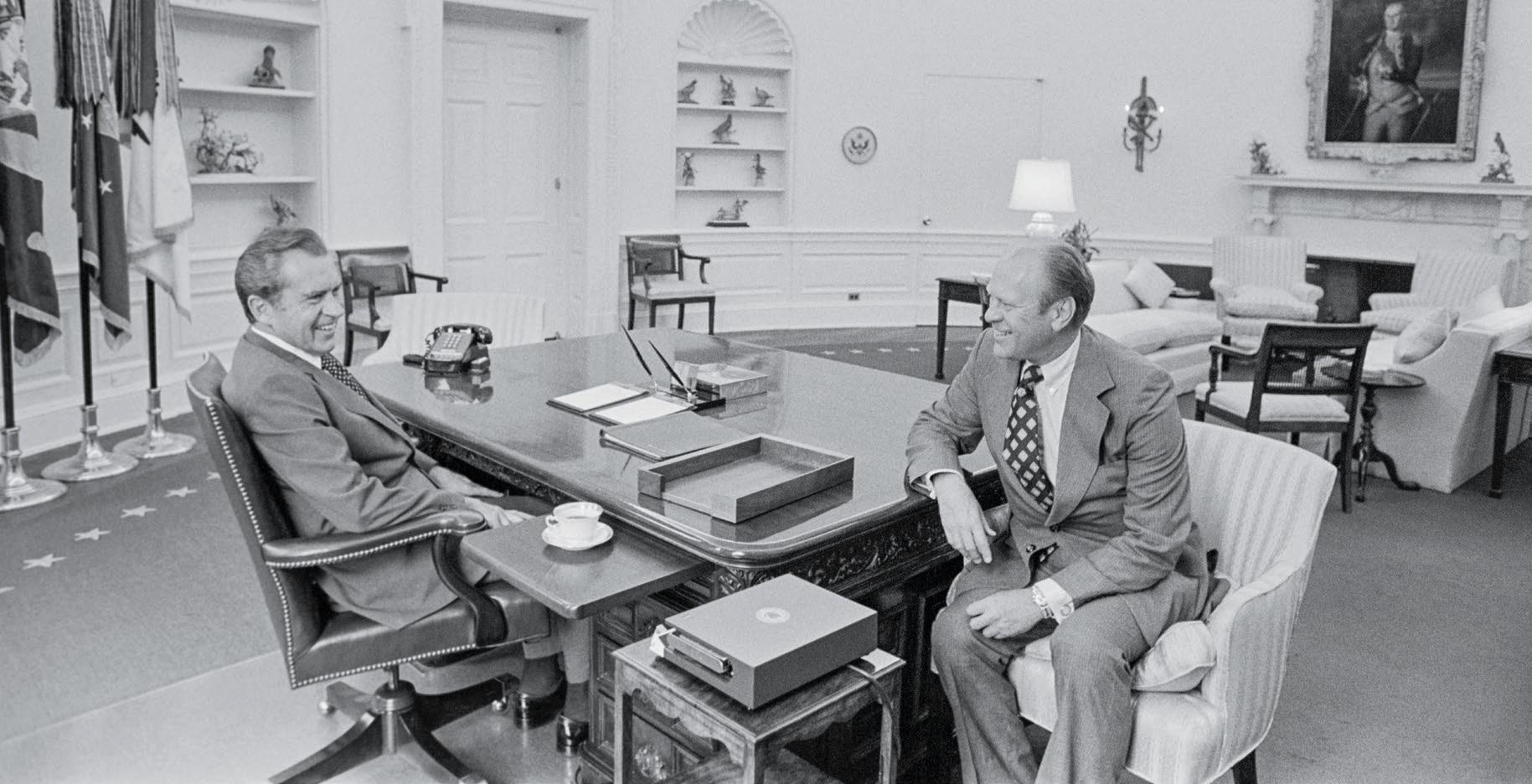

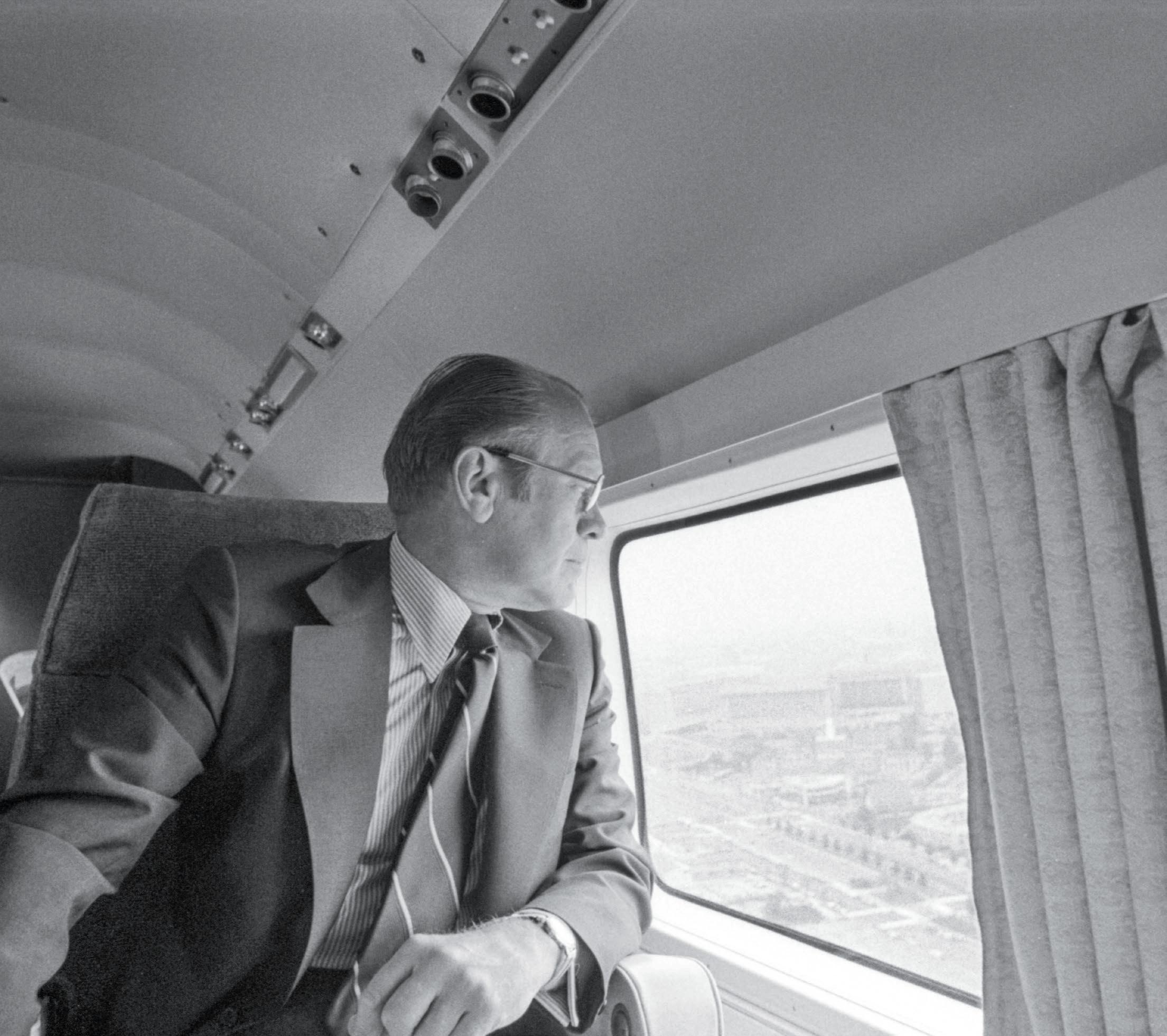

David Kennerly (1947– ), in contrast, had amazing access to Gerald Ford, who had been Nixon’s vice president and succeeded to the nation’s highest office after Nixon resigned in August 1974.

Kennerly, an affable and laid-back individual who would often wear jeans to the Oval Office, was naturally simpatico with Ford, a genial former congressman from Michigan. Both the president and First Lady Betty Ford wanted Kennerly to document the public and private history of the Ford administration.

Kennerly, who had been a Pulitzer Prize–winning news photographer for UPI during the Vietnam War, became so close to Ford that the

president asked him to join an official fact-finding mission to Vietnam in 1975. When he returned, Kennerly showed Ford the pictures he had taken of civilian casualties, including injured and dying children, and the president, Kennerly said later, was “devastated.”5 Kennerly believed these pictures helped persuade Ford to begin an airlift of Vietnamese orphans out of the country.

The president who succeeded Ford, Jimmy Carter, did not name a chief photographer, thinking that official pictures were not worth his time.

Mike Evans (1944–2005) had a big advantage as Ronald Reagan’s chief photographer: Reagan appreciated the power of imagery. He was camera savvy and actually paid attention to what his chief lensman wanted.

Evans worked for years as a news photographer, and, on assignment for Time magazine, he covered both Reagan’s unsuccessful 1976 presidential campaign and his successful 1980 campaign. After Reagan won, he named Evans as his White House chief photographer.

“The job of photographing the president—sure, you have to be a good photographer,” Evans once said. “But in many ways, the job is more like being a valet than like the secretary of state. You’re often with him and his family in very intimate settings so you have to get along. They liked my photography, sure, but I think they liked my persona more.” Wearing gray flannel suits with button-down shirts and respectful of Reagan’s conservative philosophy, Evans fit in perfectly at the Reagan White House. He was able to be “both ubiquitous and invisible,” an admiring reporter said.6

above

White House chief photographer Michael Evans confers with President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office, January 28, 1981.

opposite Evans is often remembered for his iconic image of Reagan in a cowboy hat, 1976.

George H. W. Bush Administration 1989–1993

David Valdez (1949– ), a soft-spoken son of Texas, rose from humble beginnings to become the only Latino to serve as chief photographer, starting in 1989. He was not just a staffer for George H. W. Bush, but also a presidential pal. Valdez quickly realized how to ingratiate himself with the Bushes—take great pictures of their grandchildren. Valdez once sent some prints of Bush and a grandchild to Barbara Bush while George was vice president, during his first day as the official vice presidential photographer in

December 1983. She loved his work. “As long as you take pictures of my grandchildren, you can go anywhere and photograph anything,” Barbara Bush wrote in response. Valdez said later, “That was my opening and I kept that note.”7

Valdez traveled all over the world with Bush while he was vice president and president, deepening their bond. Sometimes, at a particularly historic meeting or grand setting, Bush would elbow his photographer and whisper, “Can you believe this? Two guys from Texas doing this?”8 Their camaraderie intensified the trust between them and gave Valdez even more access.

left Photographer

David Valdez poses at the Taj Mahal with then Vice President

George H. W. Bush, May 13, 1984.

opposite

Valdez captured President Bush enjoying a conversation with Time magazine correspondent and friend Hugh Sidey (top), December 20, 1991. First Lady Barbara Bush especially appreciated the photographs Valdez took of her grandchildren. She is seen here (bottom), with granddaughter Marshall Lloyd Bush, visiting Millie’s new litter of puppies, March 18, 1989.

Clinton Administration 1993–1998

Bob McNeely (1947– ) was the chief photographer for Bill Clinton during his first term. McNeely had an excellent resume. He had taken pictures for Democratic Vice President Walter Mondale during the administration of President Jimmy Carter, had worked as a freelance photographer for news organizations such as Time and Newsweek, and earned a Bronze Star as a young combat soldier in Vietnam, so he was accustomed to fast-moving situations and crisis conditions. Having served as Clinton’s campaign photographer in the 1992 campaign, he got along well with the president and first lady. McNeely wrote in his memoir:

The job of White House photographer entailed long hours spent going to an event, waiting for an event to begin, or waiting to leave when it was over. I would always have my camera at the ready, even when nothing momentous was happening. In these moments people let their guard down, giving me some revealing character insights. Such a shot happened just after the president gave his first State of the Union address, when he and First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton met in an anteroom and spontaneously hugged. There in their faces is the obvious joy they feel in his success—in which she played no small part. But, as you can see in the reflection in the mirror behind them, they were rarely alone.9

What is revealed in the mirror, I explain in my book, is a room full of people.10 McNeely had carefully framed his shot to show the Clintons a bit off to the side, gazing into each other’s eyes, Bill with a flirtatious look on his face and Hillary smiling with delight. But as McNeely wrote, it was not really a situation that allowed privacy.

istration, was the only African Americantographer. Her approach was similar to thatphers: remain as unobtrusive as possible so -

vous about how they might look and perhaps ask her to leave. “I was quiet,” she recalled. “We would come into a room and I’d try to be

One of Farmer’s favorite pictures was a high point for her personally. “I accompanied the President and Mrs. Clinton to Ghana,” she recalled. “There was a huge rally in the stadium in Accra. There must have been over 250,000 people cheering the president and first lady. What a moment in time! Never in my wildest dreams did I ever imagine that an American president would visit an African

Clinton Administration 1999–2000

Clinton Administration 1999–2000

Sharon Farmer (1951– ), who in 1999 followed McNeely during the Clinton administration, was the only African American woman to serve as White House chief photographer. Her approach was similar to that of other successful White House photographers: remain as unobtrusive as possible so the subjects do not get self-conscious or nervous about how they might look and perhaps ask her to leave. “I was quiet,” she recalled. “We would come into a room and I’d try to be like a fly on the wall.”11

Sharon Farmer (1951– ), who in 1999 followed McNeely during the Clinton administration, was the only African American woman to serve as White House chief photographer. Her approach was similar to that of other successful White House photographers: remain as unobtrusive as possible so the subjects do not get self-conscious or nervous about how they might look and perhaps ask her to leave. “I was quiet,” she recalled. “We would come into a room and I’d try to be like a fly on the wall.”11

One of Farmer’s favorite pictures was a high point for her personally. “I accompanied the President and Mrs. Clinton to Ghana,” she recalled. “There was a huge rally in the stadium in Accra. There must have been over 250,000 people cheering the president and first lady. What a moment in time! Never in my wildest dreams did I ever imagine that an American president would visit an African country and be received so wonderfully.”12

One of Farmer’s favorite pictures was a high point for her personally. “I accompanied the President and Mrs. Clinton to Ghana,” she recalled. “There was a huge rally in the stadium in Accra. There must have been over 250,000 people cheering the president and first lady. What a moment in time! Never in my wildest dreams did I ever imagine that an American president would visit an African country and be received so wonderfully.”12

Sharon Farmer captured this photo of President and Mrs. Clinton congratulating Chelsea Clinton following her high school graduation from Sidwell Friends School, 1997.

photographs

Bill Clinton in the Oval Office as he greets President Leonid Kuchma of Ukraine during the NATO 50th Anniversary Summit, April 24, 1999.

President Bill Clinton in the Oval Office as he greets President Leonid Kuchma of Ukraine during the NATO 50th Anniversary Summit, April 24, 1999.

George W. Bush Administration 2001–2009

Eric Draper (1964– ) was an Associated Press photographer who for eighteen months covered George W. Bush’s successful 2000 presidential campaign. When Bush won, Draper realized he had a shot at being named the White House chief photographer, but, he wondered, “Could a black kid from SouthCentral Los Angeles be the photographer for the President of the United States?”13 The answer was yes.

After Bush gave him the job, Draper documented many historic moments. Most significant was Bush’s response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. On September 14, Bush flew to New York to visit first responders and firefighters at the World Trade Center crash site. Bush jumped atop a burned-out fire truck and began speaking, but some of the first responders shouted that they

could not hear him. As they chanted “USA!” he used a bullhorn and declared, “I can hear you. The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.”14 It was precisely what the country wanted to hear from the commander in chief, and Draper captured the moment of resolution and strength in a vivid photo that was sent around the world.

Draper also shifted the White House photo operation from film to digital. This technology made the images sharper and enabled the photographers to take vastly more pictures than they could with film. During his eight years in the White House, Draper made nearly 1 million pictures, a major step forward.

left

Former White House Chief Photographer

Eric Draper speaks at a Society of Professional Journalists event about his experiences photographing President

George W. Bush, August 29, 2011.

opposite Draper captured this historic moment when President George W. Bush spoke to rescue workers, firefighters, and police officers from the rubble of Ground Zero in New York City, September 14, 2001.

Obama Administration, 2009–2017