A Break with Tradition: FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S “Backyard” Inauguration

MARY JO BINKER

president franklin d. roosevelt wanted his unprecedented fourth Inauguration, on January 20, 1945, to be different. His three previous ceremonies had been full of pomp and ceremony. But the America of 1945 was different, and so was he. The nation was at war, and his health was failing.

Twelve strenuous years as president—a period that included the Great Depression and most of World War II, had taken a toll on his body already weakened by polio. Although FDR was only 62, he suffered from hypertension, an enlarged heart, congestive heart failure, pulmonary disease, and severe anemia. While he could—and did—still rally, as he did during the 1944 presidential campaign, the effort took its toll.1

Emotionally, too, Roosevelt was at low ebb. Many of his close associates had died or left the West Wing. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was often away, and their four sons were in the armed services. His mother, a constant source of support, was dead. Only the Roosevelts’ daughter, Anna, was living in the White House full time and working as an aide to her father. Adding to his malaise, his well-meaning doctors had deprived him of most of his daily pleasures—restricting his diet, reducing his consumption of alcohol and cigarettes, forbidding exercise, and limiting his social contacts.2

To conserve his energies and avoid admitting his infirmities, Roosevelt decided to use the war as the excuse to shatter another precedent. He would shorten the inaugural ceremony to twenty minutes and hold it outside on the South Portico of the White House rather than at the U.S. Capitol.3 Instead of the traditional parade, he and Mrs. Roosevelt would host a gigantic buffet luncheon for approximately 1,800 guests with a menu that reflected both wartime austerity and domestic compromise—chicken salad (with more celery than chicken), rolls (no butter), unfrosted cake, and coffee. (FDR originally wanted to serve chicken à la king but White House housekeeper Henrietta Nesbitt had had the unenviable task of telling him that the White House kitchen staff could not “keep that dish hot” for so many guests.)4 The luncheon would be followed by a large tea and two receptions that would bring another 1,750 guests to the White House.5

The president’s decision to hold his Inauguration in the White House’s “backyard” put the burden of planning the event on the staffs of the East and West Wings instead of on Congress.6 Roosevelt’s secretary and military aide, Major General Edwin (“Pa”) Watson convened a working group in the Fish Room (now the Roosevelt Room) that included

previous spread and opposite President Franklin Roosevelt takes the Oath of Office on the South Portico, January 20, 1945 (page 44). While invited guests fill the president’s “backyard” inside the fence, those without tickets fill the Ellipse (page 45) to the south to get a glimpse of the president as he delivers a brief Inaugural Address (first page, opposite).

left

President and Mrs. Roosevelt pose for a family photograph with their grandchildren in the Second Floor Library (today’s Yellow Oval Room), the day of FDR’s fourth Inauguration, January 20, 1945.

White House social secretary Edith Benham Helm, representatives of the District of Columbia police, the press, and Residence staff who, according to future White House Chief Usher J. B. West, spent “two double-duty months in preparation.”7 The logistics were daunting: feeding, sheltering, and controlling a large crowd for multiple events in a tight space in what was sure to be unpredictable weather.

Eleanor Roosevelt captured the hectic preinaugural pace in her “My Day” column. “The telephones ring incessantly, adding names, making changes in addresses or asking for duplicates” of lost tickets. Many of the callers were also unpleasant, and the secretaries had to deal with the “impatience and misunderstanding and, in some cases, real irritation” from would-be guests.8

Among those who received the coveted invitations were the Roosevelts’ thirteen grandchildren. FDR had insisted that they all be present, and so by January 20, the White House was bulging “at the corners,” according to Mrs. Roosevelt. The Executive Mansion was so crowded that she had to give up her own bedroom and sleep in a Third Floor sewing and pressing room. The only place she could find to work was a corner of her secretary’s desk “in her very small office.”9 FDR’s cousin, Margaret (“Daisy”) Suckley, who had been staying in a little room off the Lincoln Bedroom, actually had to move to the home of some friends.10 The family may have been close, but they were hardly comfortable, because the Roosevelts adhered to recent federal regulations requiring that building temperatures be kept at 68 degrees to conserve coal.11

Outside it was even colder. A thin coating of snow covered the ground on Inauguration Day, and the temperature hovered just above freezing. Mansion staff had roped off an area below the South Portico and laid tarpaulins on the grass for the most important guests, including members of Congress, governors, assistant cabinet officers, District of Columbia officials, members of the Electoral College, members of the Democratic National Committee, foreign diplomats, plus fifty wounded servicemen from nearby Walter Reed Hospital. Military police patrolled that area and the section of the lawn behind it, where lower-ranking officials stood in the “cold slush,” stamping their feet to keep warm in the rain, sleet, and wind. Behind this group “at the edge of the space reserved for guests” was the Marine Band. Beyond the White

House Grounds, several thousand ticketless private citizens filled the Ellipse all the way to Constitution Avenue. The atmosphere was tense and so quiet that attendees could hear the “soft whirring” of the newsreel cameras stationed above them.12

Inside the White House, the atmosphere was noticeably different. Instead of the usual religious service at St. John’s Church on Lafayette Square, which had preceded all three of FDR’s previous Inaugurations, the president had elected to hold a small religious service in the East Room before taking the Oath of Office. Many of the two hundred guests invited to this event had not been invited to join the official party outside. Nevertheless, once the service ended, “some . . . began to surge toward the Portico in a wave that could not be stopped,” Helm later wrote.13

These uninvited guests joined the members of the Supreme Court and their spouses, the cabinet members and their wives, congressional leaders, the heads of the armed services, presidential aides, and other invited dignitaries, in what quickly became a “terrific” crowd in the small space.14 Off to the side the Roosevelt grandchildren joined by the children of Norwegian Crown Prince Olav and Crown Princess Martha and three of Eleanor Roosevelt’s nieces stood on the curved steps that led from the Portico to the ground.15

Shortly before noon, Franklin Roosevelt, preceded by Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, Vice President–Elect Harry S. Truman, and outgoing Vice President Henry Wallace, was wheeled onto

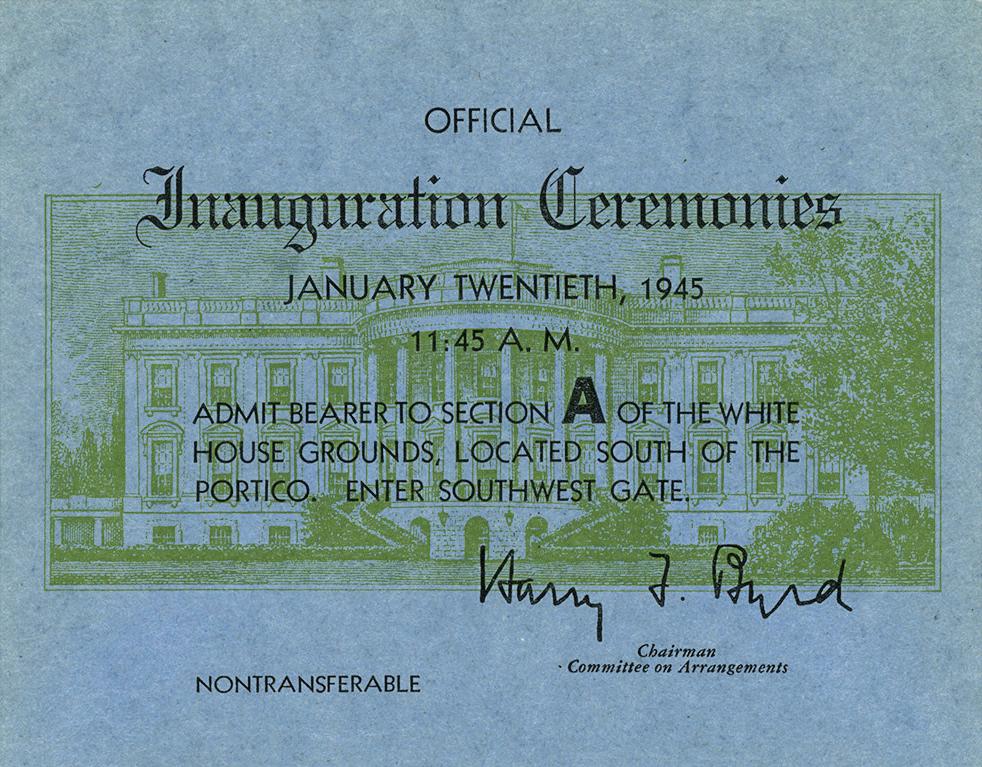

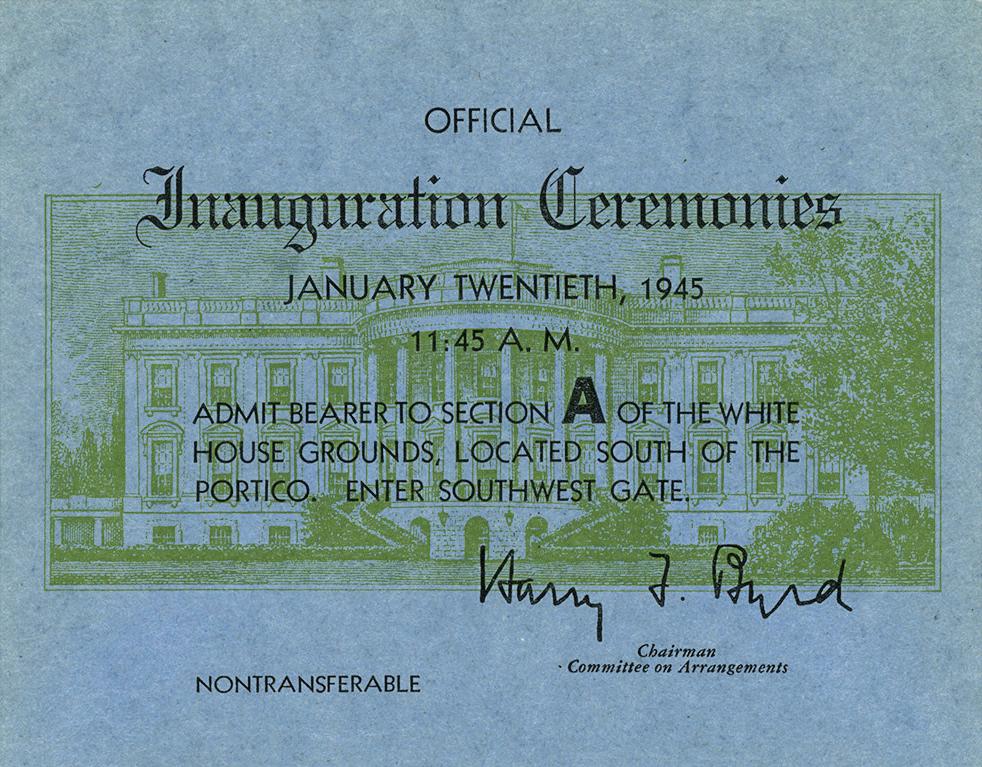

A ticket to FDR’s 1945 Inauguration allowed the bearer to stand on the South Lawn.

Wounded veterans and press can be seen among the ticketed attendees as FDR delivered his fourth and final Inaugural Address. Those without tickets gathered on the Ellipse, standing in the slush during the ceremony.

the South Portico. After an opening invocation and the playing of the National Anthem, Wallace administered the Oath of Office to Truman. Then, hatless and coatless in the bitter winter weather, Roosevelt, looking pale and drawn, “walked” to the podium on the arm of his son, James, and took the Oath of Office for the fourth time.16

In what was his final Inaugural Address, which he had insisted be no longer than five minutes, Roosevelt, speaking without gestures, urged his listeners to be patient and have faith that the Allies would win the war and achieve a “durable peace.” He then reaffirmed his faith in human progress, quoting his Groton headmaster, Endicott Peabody, that “things in life will not always run smoothly. . . . The great fact to remember is that the trend of civilization itself is forever upward.” Roosevelt reminded his listeners of the “lessons” the war had taught: “that we cannot live alone, at peace; that our own well-being is dependent on the wellbeing of other nations, far away,” and, that, quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The only way to have a friend is to be one.” Roosevelt said those precepts would guide the peacemaking process. The president closed with a prayer “for the vision to see our way clearly—to see the way that leads to a better life for ourselves and for all our fellow men.” He remained standing through the end of the ceremony, lifting “his right arm high in greeting to the crowd before he sat down.”17

“It was deeply moving to watch him standing there in the cold winter air . . . delivering these simple words,” Sam Rosenman, one of Roosevelt’s speechwriters, remembered.18 “It did all of us good to see him standing there, straight & vigorous,” Suckley noted in her diary afterward. “All the sentimental ladies who love him were ready for tears!”19

Rosenman and Suckley might have been less sanguine if they had known that shortly after the ceremony, Roosevelt suffered an angina attack similar to one he had experienced in the summer of 1944. His oldest son, James, who had been at his father’s side at all four Inaugurations, remembered the president saying, “Jimmy, I can’t take this unless you get me a stiff drink. You’d better make it straight.” James did so and the president drank the whiskey “as if it was medicine.”20 Then he went on to the festivities.

Meanwhile, the invited guests, defying all protocol, surged into the White House in no particular order except for members of the Diplomatic Corps,

who arrived in the correct order of precedence having been lined up by the State Department’s chief of protocol. The guests shook hands with Bess Truman and Eleanor Roosevelt, who held a bouquet of violets, a traditional inaugural gift from Hyde Park neighbors.21 Then guests proceeded to the East Room, the State Dining Room, or the Ground Floor hallway, where long tables with preplated lunches had been arranged. “You took a cup of coffee and a plate with a roll and chicken salad on it,” recalled one guest, Katherine Tupper Marshall, spouse of General George G. Marshall. “That was the entire luncheon.”22 Besides Mrs. Marshall, other guests included Edith Wilson, widow of the twentyeighth president, under whom FDR had served as undersecretary of the navy; civil rights activist and New Deal official Mary McLeod Bethune; author, lecturer, and disability rights advocate Helen Keller; and sculptor Jo Davidson, who had designed a commemorative medal to mark the occasion.23 FDR lunched in the Red Room with a “small and intimate circle” that included Truman and the Norwegian royals.24

The luncheon had scarcely ended before the Residence staff began setting up for the afternoon events—a tea for 875 guests, followed by a reception for almost 200 Democratic members of the Electoral College, and a final reception for almost 700 people who, Mrs. Roosevelt said, “didn’t come to lunch.” FDR attended the reception for the electors but skipped the other events. The day ended with a dinner in the State Dining Room for eighty close friends and political advisers.25

Two days after the Inauguration, Franklin Roosevelt left for Yalta to confer with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin about the conduct of the war in Europe and Asia, the shape of the postwar world, and the structure of the embryonic United Nations. Before he left, however, he wrote to thank Helm for her work: “I want you and all your staff to know how deeply I appreciate the very fine and efficient job you did in connection with the Inaugural ceremonies. I know how hard you have all worked during these past weeks, and I congratulate you all on the fine results of your efforts.”26

Mrs. Roosevelt wrote Helm as well, expressing her gratitude “for the magnificent job” the White House social secretary had done on the Inauguration. She also wrote Nesbitt to thank her and the Residence staff “for handling so efficiently

the very large crowd which we had on Inauguration Day. . . . I know it meant a great deal of work for everyone.”27

As historic as Franklin Roosevelt’s White House Inauguration had been, it was quickly overshadowed by more dramatic events—the Yalta Conference, his own death the following April, and the end of World War II in Europe and Asia. Nevertheless, his January 1945 ceremony remains one of the most unusual—and unique—presidential Inaugurations in American history. Roosevelt’s desire to conserve his energies resulted in an event that struck just the right note for a nation at war. At a time when the future was murky, his “backyard” Inauguration28 had not only saved him from the rigors of a more traditional ceremony but gave his listeners comfort and hope.

notes

1. Hugh Gregory Gallagher, FDR’s Splendid Deception: The Moving Story of Roosevelt’s Massive Disability—and the Intense Efforts to Conceal It from the Public (Arlington, Va.: Vandamere Press, 1999), 180–89; Robert Dallek, Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Political Life (New York: Viking, 2017), 550–51; H. W. Brands, Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 778–79, 781.

2. Gallagher, Splendid Deception, 188–89; Doris Kearns Goodwin, No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt—The Home Front in World War II (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 516.

3. “Roosevelt Asks Simple Inaugural,” New York Times, November 15, 1944, 18.

4. Henrietta Nesbitt, White House Diary (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1949), 303.

5. J. B. West and Mary Lynn Kotz, Upstairs at the White House: My Life with the First Ladies (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1973), 48; Edith Benham Helm, The Captains and the Kings (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1954), 243.

6. Robert C. Albright. “Backyard Inaugural to Find Oldtimers Other Side of Fence,” Washington Post, January 14, 1945, B1.

7. West and Kotz, Upstairs at the White House, 47. See also Helm, Captains and Kings, 241.

8. Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day,” January 20, 1945, The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition (2017), www2.gwu.edu.

9. Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 339.

10. Margaret Suckley, diary, January 16 and January 18, 1945, Closest Companion: The Unknown Story of the Intimate Friendship Between Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Suckley, ed. Geoffrey C. Ward (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 383, 385.

11. Suckley, diary, January 16, 1945, ibid., 383. In mid-January FDR had announced that the White House and all federal agencies would comply with the order issued earlier by War Mobilization director James F. Byrnes calling for a “maximum temperature” of 68 degrees “in all homes and public buildings” to avoid “an impending coal shortage.” Byrnes also banned “ornamental” lighting and outdoor advertising lighting. “Blackout of Advertising Lighting, Reduced Heating Asked by Byrnes,” New York Times, January 11, 1945, 1. See also “President Pledges Aid on Heat Curb,” New York Times, January 13, 1945, 20.

12. West and Kotz, Upstairs at the White House, 47; Bertram D. Hulen, “Shivering Thousands Stamp in the Snow at Inauguration,” New York Times, January 21, 1945, 1. Future

Secretary of State Dean Acheson thought the “complicated” roping arrangements unnecessary since “the portico could be seen perfectly well from any one of the enclosures,” possibly because all the awnings except the center one were down and the guests’ umbrellas had been confiscated at the gates. Dean G. Acheson, Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department (New York: W. W. Norton, 1969), 102; “Roosevelt Is Batting .750 in Inauguration Weather,” New York Times, January 21, 1945, 27.

13. Helm, Captains and Kings, 242. See also West and Kotz, Upstairs at the White House, 47.

14. Helm, Captains and Kings, 242.

15. Bess Furman, Washington By-Line: The Personal History of a Newspaperwoman (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1949), 310; Hulen, “Shivering Thousands,” 1. Roosevelt first met Norwegian Crown Princess Martha in 1939 when she and her husband, Crown Prince Olav, visited the United States on a three-month goodwill tour. A year later she and her three children accepted the president’s offer of asylum after the Nazis overran their country. Attracted to Martha’s charm and beauty, the president insisted that they live in the White House, which the family did until Martha rented an estate in nearby Maryland. Thereafter the Crown Princess was a frequent White House guest. She and the children returned to Norway after the war in Europe ended. Goodwin, No Ordinary Time, 149–54.

16. Frank Freidel, Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny (Boston: Little, Brown, 1990), 573. See also Suckley, diary, January 20, 1945, Closest Companion, ed. Ward, 387; Katherine Tupper Marshall, Together: Annals of an Army Wife (Chicago: People’s Book Club, 1947), 232.

17 “Roosevelt’s Inaugural Address Text,” Washington Post, January 21, 1945, M1. See also Hulen, “Shivering Thousands,” 1; Samuel I. Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1952), 517.

18. Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt, 516–17. Rosenman (page 517) noted that he and two other speechwriters had submitted drafts for this speech to the president. Roosevelt took those drafts plus material he had previously dictated and combined them into a speech that Rosenman said “was shorter than any” of the speechwriters’ drafts—just 573 words. See also Freidel, Franklin D. Roosevelt, 574.

19. Suckley, diary, January 20, 1945, Closest Companion, ed. Ward, 387.

20. Quotations in Goodwin, No Ordinary Time, 572–73.

21. Bess Furman, “Luncheon Marked by Informality,” New York Times, January 21, 1945, 27.

22. Marshall, Together, 233. Daisy Suckley remembered that cake was also served at the luncheon. Suckley, diary, January 20, 1945, Closest Companion, ed. Ward, 387.

23. Furman, “Luncheon Marked by Informality,” 27; “President Works on Address for Inaugural; Approves Medal,” Washington Post, January 19, 1945, 12.

24. Furman, “Luncheon Marked by Informality,” 27; Suckley, diary, January 20, 1945, Closest Companion, ed. Ward, 387–88.

25. Eleanor Roosevelt quoted in Furman, “Luncheon Marked by Informality,” 27. See also Helm, Captains and Kings, 243; West and Kotz, Upstairs at the White House, 48. Furman (page 27) noted that the last guests had to make do with paper napkins and wooden spoons since, by that time, the White House kitchen had run out of silverware and cloth napkins.

26. Franklin E. Roosevelt to Edith Helm, January 22, 1945. quoted in Helm, Captains and Kings, 244.

27. Eleanor Roosevelt to Edith Helm, January 22, 1945, quoted in ibid,, 243; Eleanor Roosevelt to Mrs. Nesbitt, January 22, 1945, quoted in Nesbitt, White House Diary, 304–05.

28. Albright, “Backyard Inaugural,” B1.