Board of Directors

chairman

John F. W. Rogers

vice chairperson

Teresa Carlson

treasurer

Gregory W. Wendt secretary

Anita B. McBride

president

Stewart D. McLaurin

Eula Adams, Michael Beschloss, Gahl Hodges Burt, Merlynn Carson, Jean M. Case, Ashley Dabbiere, Wayne A. I. Frederick, Deneen C. Howell, Tham Kannalikham, Metta Krach, Barbara A. Perry, Ben C. Sutton Jr., Tina Tchen

national park service liaison: Charles F. Sams III

ex officio: Lonnie G. Bunch III, Kaywin Feldman, Carla Hayden, Katherine Malone-France, Colleen Shogan

directors emeriti: John T. Behrendt, John H. Dalton, Nancy M. Folger, Knight Kiplinger, Elise K. Kirk, Martha Joynt Kumar, James I. McDaniel, Robert M. McGee, Harry G. Robinson III, Ann Stock, Gail Berry West

white house history quarterly

founding editor

William Seale (1939–2019)

editor

Marcia Mallet Anderson

associate vice president of publishing

Lauren McGwin

editorial coordinator

Rebecca Durgin

editorial and production manager

Margaret Strolle

consulting editor

Ann Hofstra Grogg

consulting design

Pentagram

editorial advisory

Bill Barker

Matthew Costello

Mac Keith Griswold

Scott Harris

Joel Kemelhor

Jessie Kratz

Rebecca Roberts

Lydia Barker Tederick

Bruce M. White

the editor wishes to thank The Office of the Curator, The White House

susan ford bales is the daughter of President Gerald Ford and First Lady Betty Ford and serves as a trustee of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation.

john chuldenko is the grandson of Jimmy Carter and a writer and director based in Los Angeles. He is an alum of the Sundance Film Festival and regularly contributes to Departures, Panorama, Craft + Tailored , and The Motoring Journal.

melinda dart is the editor of A Glimpse of Greatness: The Memoir of Irineo Esperancilla, which explores her grandfather’s experiences as a United States Navy steward for Presidents Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

alan devalerio is a former White House contract butler. He lives in Frederick, Maryland, and enjoys speaking engagements.

tina hager is an American international photojournalist and project manager with thirty-five years

experience. As a White House photographer for the George W. Bush administration, she completed a major photography project on the White House Residence staff. Currently based in Dubai she has completed more than six-hundred assignments in sixty-five countries, typically in volatile and adverse settings, capturing a diverse collection of international newsworthy events, unique areas of interest, and stories on the human condition.

scott harris is the executive director of University of Mary Washington Museums. He is also an editorial adviser and a frequent contributor to White House History Quarterly.

david ramsey is a corporate interior designer who specializes in commercial and historic preservation interiors.

donna hayashi smith is the associate curator of collections and registrar with the Office of the Curator, the White House. She is a regular contributor to White House History Quarterly.

Cream soup bowls from the Franklin D.

64 A DREAM JOB AT THE WHITE HOUSE REMEMBERED: Reflections of a Former Contract Butler alan d e valerio

70

HONORING THE LEGACY OF MY FATHER, PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD: First Daughter Susan Ford Bales Shares the Stories Behind the Design of the 2023 Official White House Christmas Ornament

susan ford bales

80

WHITE HOUSE WAX: Discovering the White House Record Library

john chuldenko

92

PRESIDENTIAL SITES FEATURE: President William Howard Taft’s Wild Ride from Washington, D.C., to the Manassas Peace Jubilee scott harris

104

REFLECTIONS Of a White House Curator

With each passing day White House history unfolds on a public stage to be duly documented for posterity. Immeasurably more of that remarkable history, however, is experienced backstage in utilitarian spaces and ordinary routines. With this issue of White House History Quarterly our authors have turned to photo albums, storage areas, diaries, and keepsakes to bring unexplored history to light. They take us behind the scenes, exploring from the rooftop to basement, from past to present, to catch glimpses of the life and fabric of the White House unlikely to appear in history books.

The nearly one hundred people who serve on the Residence staff are dedicated to the smooth operation of the house. For many it is their life’s work, but for most their names will not be easily found by future scholars. Thanks to White House photographer Tina Hager, however, the early twenty-first-century staff will be remembered through the Residence Portraits Project. Encouraged by First Lady Laura Bush to complete the ambitious project, Hager ventured into the White House kitchens, elevators, laundry and mechanical rooms, and even under a restroom sink, creating beautiful photographic portraits that reveal not only the likenesses but the personalities and dedication of butlers, ushers, chefs, housekeepers, carpenters, gardeners, electricians, and others. Future historians will be grateful for this rich collection, shared here in the Quarterly, which documents an era in time.

The White House holds a collection of approximately five hundred works of art and sixty thousand objects, only a fraction of which can be in use or on display at any given time. Although many are stored off-site, there is a modest space within the White House itself where objects such as the bill-signing table and lectern used by the president can be quickly retrieved. Associate Curator of Collections Donna Hayashi Smith takes us on a tour of this small but state-ofthe-art collections storage area where precious objects are hung, boxed, shelved, studied, and kept safe from harm when off of public view.

One of many young Filipino men who enlisted in the U.S. Navy in the early twentieth century, Irineo Esperancilla (“IE”) would ultimately be assigned to serve as a “special steward attached to the persons” of four U.S. presidents. From 1930 to 1955, during years of war and peace, he served the presidents at the White House, on retreats, and aboard ships that took him around the world, carefully recording his experiences in an unpublished typescript. “I know that I did not have any part in history, but . . . it is my duty toward the

American people to put into writing my recollections of the great men whose service is the glory of my life,” he explained. His granddaughter Melinda Dart shares IE’s story with the Quarterly and describes how she preserved it.

Witnessed by only about six hundred people, the East Room funeral of President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most riveting events in all of White House history. Yet there is no photographic record. With documentary accounts and renderings by period artists as his starting point, David Ramsey has used twenty-first-century computer technology to create a collection of views depicting the canopied catafalque in the darkened East Room, draped in mourning, as only the funeral attendees would have seen it.

For Alan DeValerio, working at the White House was a dream fulfilled. He takes us back to the early 1980s to share his memories of the dinners and events he experienced in the role of contract butler.

Music lover John Chuldenko brings to light a little-known White House collection that holds special memories for two former White House residents, his uncles Chip and Jeff Carter, President Carter’s sons. Inspired by their stories of records played on a turntable in the Solarium, Chuldenko began a quest to find the collection. His persistence resulted in a rare opportunity to explore the record albums and play a few of his favorites, an experience he shares with the Quarterly

Millions of Official White House Ornaments are hung on American Christmas trees each holiday season. Produced by the White House Historical Association since 1981, the ornaments honor a different president or historic event each year. Susan Ford Bales shares her personal perspective on the stories behind the design of the 2023 ornament that honors her father, President Gerald R. Ford.

For our Presidential Sites feature, we experience an early version of presidential travel behind the scenes. When a jovial President William Howard Taft roared into Manassas in his White steamer automobile to speak at the 1911 Peace Jubilee, the assembled Civil War veterans were unaware of the harrowing adventure he had survived on Virginia’s muddy and flooded roads during his journey from the White House. Scott Harris retraces his route.

We open this issue with a special presidential behind-thescenes memory of the White House. With a moment recalled through a poem, “A Reflection of Beauty in Washington,”

President Jimmy Carter shares an unexpected sighting during a late night star-gazing excursion to the White House roof.

illustrated by Sarah Chuldenko

illustrated by Sarah Chuldenko

I recall one winter night going to the White House roof to study the Orion nebulae, but we could barely see the stars, their images so paled by city lights.

Suddenly we heard a sound primeval in its tone and rhythm coming from the northern sky. We turned to watch in silence long wavering V’s breasts transformed to brilliance by the lights we would have dimmed. The geese passed overhead, and then without a word we went down to a peaceful sleep, marveling at what we’d seen and heard.

TINA HAGER WITH MARCIA ANDERSON

TINA HAGER WITH MARCIA ANDERSON

tina hager is an accomplished photojournalist who has used her camera to capture history unfold around the world for more than thirty-five years. She served as a White House photographer during the presidency of George W. Bush, and it was during this time that she completed a special project to photograph members of the Executive Residence staff. The resulting portraits go well beyond documenting the likenesses of the nearly the one hundred professionals dedicated to ensuring the smooth operation of the house. Incorporating the historic White House rooms as well as the tools used by each of her subjects in their roles, the photographs capture responsibilities and personalities, and they provide a vivid record of a moment in time in White House history. Over the years the Quarterly has often drawn from the collection to enrich the stories we strive to tell in both words and pictures. Earlier this year, Tina Hager shared memories of the unique project with Marcia Anderson, editor of White House History Quarterly. Their conversation follows.

MARCIA ANDERSON: How did you come to work at the White House, and what did your job routinely involve?

TINA HAGER: I had been a freelance photographer working on current events and in challenging environments since the early 1990s. Occasionally I would come across news teams that were cohesive and professional. They appeared to have a camaraderie that appealed to me as much or more than the stereotypical lone photographer life-style. The penny dropped when I was working alone covering Kosovo. The White House notion started to ruminate while watching CNN in a hotel room. It was 1999, so there was obviously an already established White House team, and I discovered through research and contacts that the photographers were selected by the administration and were not carried over from one president to the next. So I had to wait for a new administration. There were no job postings, so I took a chance on sending my portfolio and resume the White House Photo Office immediately after the

election results. As I’m sure you recall, there was an extraordinary delay in the confirmation of the election results. I didn’t hear anything until April 2001, when I asked for my portfolio back; it was leather-bound and I wanted it back.

I started in early August 2001. I was hired as the third photographer to the president, with on-call duties for the first lady and the vice president. The daily schedule was intense, with 6:00 a.m. starts and 10:00 p.m. finishes most of the week and only an occasional day off. It was a precarious position; if you missed a motorcade you could lose your job. There were regular assignments to travel with the president on Air Force One. The photographers document every part of his schedule. We were recording for the National Archives and for the president. We were not press or media, so we had access to intricate and intimate meetings in the Oval Office. There were also times when we were kicked out.

PREVIOUS SPREAD

A selection of Tina Hager’s Residence portraits, c. 2001–04, clockwise from top left: Housekeeper Annie Elizabeth Brown; Carpenter Foreman Edgar Watson; Housekeeper Betty J. Finney; Houseman Bernard Ward; Curator William G. Allman; Executive Butler Ronald Guy; Assistant Usher Nancy F. Mitchell. And Hager is seen at work, 2001.

RIGHT

In her role as White House photographer, Tina Hager regularly traveled with President George W. Bush. She is seen (top) to the right of President Bush on Air Force One, 2003. While documenting the work of the president, she had access to the Oval Office, where she often photographed President Bush at work (right), 2001.

TOP:

PHOTO BY ERIC DRAPER, COURTESY OF TINA HAGER / BOTTOM: TINA HAGER, AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

TOP:

PHOTO BY ERIC DRAPER, COURTESY OF TINA HAGER / BOTTOM: TINA HAGER, AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

What was the inspiration for the Residence Portrait Project, and approximately how many members of the Residence staff did you photograph?

I mentioned the idea of the Residence staff project during my interview process. When I was a child I watched a British TV show called Upstairs, Downstairs. It was the Downton Abbey of its day. I loved the twin tale of two different dramas unfolding simultaneously, each in its own orbit. The Residence staff was much larger than the cast of the show! There were, and probably still are, almost one hundred members of the Residence staff.

Your photographs include such evocative shots as curators holding objects, engineers with tools, housekeepers with laundry, and butlers carrying serving trays. How were the shots planned? Did you work with each person to learn about his or her daily responsibilities?

On previous photo assignments, I tried to add some lateral concept to the shoot. I’m sure most photographers do the same. The props that define Residence staff members’ work are lovely. Sometimes they were hand-stitched linens, engraved silver, and works of art. Other times they were bowling pins, wrenches, and ladders. These were people I came to know personally. I did meet with every one of them to learn about his or her duties. I ultimately wanted each to have a presidential photo. I wanted them to be proud of their portraits. It was never my intention for the photographs to be candid.

Your subjects included many professionals who were accustomed to working behind the scenes— engineers, plumbers, housekeepers. I imagine that they would have rarely if ever appeared in official White House photographs. Did they enjoy the experience, or were they hesitant to be photographed?

The White House is a vast building with many levels. So much work is done to keep this very old house running. From winding a clock, keeping the plumbing working, constantly moving the priceless furniture and artwork, curating and planting the tulip bulbs in the Rose Garden. It was a hard sell at first. The staff are discreet people. They have great humility. Some took more time than others to agree to participate. As the endeavor grew and the feedback started to spread, much of the hesitancy and apprehension subsided. I want to believe that the staff realized that they were being recorded in history. I have no doubt that there was a gentle nudge or two from Chief Usher Gary Walters. The project became a team event of a kind. Some staff were instantly grateful, but I did receive a message after twenty years from one gentleman who said he disliked the project at the time but had finally made peace with it.

Why did you choose black-and-white film for the portraits?

I studied classic photography (old school) in Germany. Black-and-white, large format and Hasselblad. There was a tradition of black-and-white photography in the White House archives. David Hume Kennerly shot in black-and-white during his tenure as White House photographer. This project was the last time film was used at the White House, as we converted to digital during the Bush administration. There is an old photographer’s saying: “Tri-X film and be there.”

Many of my favorite photographs were taken in the underground utility areas. It is fun to see the equipment as well as the engineers at work. Was it difficult to set up shots in those spaces?

I had security clearance to access nearly all areas of the White House. The Secret Service vetted every photograph. It was fun exploring the unfrequented rooms, the places that are not seen on tours. With the help of a tripod and only ambient light, I managed to capture some nice moments.

You took a wonderful portrait of the Assistant Supervisor to the Housekeeping Department Benjamin Morrow. He is mirroring the famous pose of President Theodore Roosevelt in the portrait by John Singer Sargent, which can be seen in the background behind him. How did that come about?

That came up naturally. I saw the portrait and wanted to reflect the dignity in both men. The White House has had many profound personalities transition through the years. What these two men have in common is reverence.

You also used windows and mirrors in some of your photographs. There is a photograph of Jerome Warren, White House Residence

Doorman, looking toward a mirror in the president’s elevator. What makes these photos so poignant?

Reflection was the aim, both physical and metaphorical. I loved that man. He was very kind to me, as were many other members of the staff. Jerome rode an elevator all day and often with some of the most important people on the planet. Capturing an image in a reflection does give the impression that the photograph is candid, and the subject becomes almost ethereal.

Do you have a favorite photograph?

Jerome through the mirror. Both for its technical composition and, as I mentioned earlier, he was an incredibly kind man.

Benjamin Morrow struck a pose made famous by President Theodore Roosevelt in his portrait by John Singer Sargent, seen over Morrow’s shoulder in the East Room. Hager explains that the composition reflects the dignity of both men.

The image of long-serving Doorman Jerome Warren seen in the mirror of the president’s elevator is Tina Hager’s favorite photograph from the Residence Portraits Project.

The image of long-serving Doorman Jerome Warren seen in the mirror of the president’s elevator is Tina Hager’s favorite photograph from the Residence Portraits Project.

Hager used natural light to create a portrait of White House Doorman Harold Hancock (left), who was joined by Spot, the president’s springer spaniel, in the Diplomatic Reception Room Foyer,

Hager also used evocative lighting in her portraits of Electrician James Barrett (opposite) in the East Room, Housekeeper Steven McDonald-Gates; and First Butler James Ramsey.

Hager’s project took her to the White House Kitchens and Flower Shop where she captured creative work underway. Her subjects included (clockwise from top left) florists Nancy Clarke and Wendy Elsasser, Staff Chef Paula Patton-Moutsos and Executive Chef Cristeta Comerford. Pastry Chef Susie Morrison is seen (opposite) in the Pastry Kitchen.

I know that many of your subjects held their positions for decades, and when I look at the photographs I can see the pride they take in their positions. How were you able to capture that so effectively?

I love this question. One story if I may. Dale Haney, a wonderful man and chief gardener who has worked at the White House for fifty years now, once gave me a small log. They had to cut down the cherry trees in the Rose Garden for some reason, and he gave me a piece of one. Years later, when my husband and I moved into our new house, he lifted that small log from a box and gave me the most curious look. I couldn’t stop laughing as I explained its significance to me. To this day I have it in my office.

Sometimes I can see people’s unease in front of a lens. At that point I will often look up, look them in the eye as a friend and as they look back at me,

as a friend, I steal the moment. The Hasselblad is a perfect instrument to capture this intimacy.

There is a lot of humor in the photographs as well. The photo of Kitchen Steward Adam Collick balancing a large pot on a few fingers above his head and the photo of White House Plumber Robert Gallahan smiling on the floor under a sink are good examples. Did you find that the Residence staff members enjoy a good laugh? Adam is a very strong man, just look at those arms! It was fun to show that. There is a lot of humor in the Residence, subtle but ever present. Some jobs like plumbing, for example, are hard to portray any other way. Under a sink seemed fitting. Mostly the staff brought their own humor with them. I was lucky to have such good material.

Among the many lighthearted portraits in Hagar’s Residence Portraits collection are, clockwise from top left, Kitchen Steward Adam Collick balancing a large soup pot above his head; Plumber Robert Gallahan preparing to work under a sink; and Melissa Naulin, associate curator of decorative arts, caught climbing a ladder in the Office of the Curator where even the tightest spaces are used for storage.

Tina Hager found inspiration in Edward Curtis’s portraits of Native Americans. Clockwise from top left: The Rush Gatherer—Arikara by Edward S. Curtis, 1909; and Tina Hager’s White House staff portraits of Chief Plumber Gary E. Williams; Housekeeper Lindsey R. Little; and Laundry Specialist Pearlina Blake.

RIGHT

It was First Lady Laura Bush who ensured Tina Hager was given time to complete the Residence Portraits Project. Mrs. Bush is seen here in a photograph made by Hager, 2003.

Are there any other stories about this project you would like to share?

This was work was done in my “free time,” and it spanned three years. At one point, I was asked to stop the project because there was simply not enough time in my schedule. I feel it was possibly because the events that were happening in world at the time cast a shadow on what was considered trivial. America was at war in Afghanistan and then Iraq. It was First Lady Laura Bush who understood the legacy value of the work and came to the rescue. She pushed it forward and insisted we complete the body of work. In fact, the photos were exhibited in the White House Visitor Center for many years.

Many of your photographs have appeared in White House History Quarterly over the years because they so effectively capture stories behind the scenes that have rarely been illustrated in more than two hundred years of White House life. I wish that collections such as yours had been undertaken in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as well, and I imagine that publishers a century from now will continue to draw on your body of work. Did you have a feeling that you

were documenting history for the future as you worked?

Serving at the White House was a great honor. To have one’s photos in the National Archives is humbling, and I never took it for granted. Looking back at the work, and without pretension, I sincerely hope you are right. A new generation of White House Residence staff continues the work of these elegant and humble people. I had no such ambitions of someone in the future re-creating this project when I embarked on the portfolio. I loved the work of Edward Curtis and his capture in large format images—black-and-white and sepia-tone—of the Native American tribes in the early 1900s. More contemporary photographers have tried to emulate his work. I have also had ambitions to do the same, although I would not put myself in his league. He is one of my all-time heroes of the medium. The White House Residence Portraits Collection was assembled in a turbulent time. This is a turbulent time, and the same can be said twenty years from now, and we can barely imagine the technological advances in photography in the future. Yet simple film, good lighting, and modest subjects will still be there for a dedicated photographer with a passion for history and the art.

in the museum world , collections storage is not a sexy topic. It is rarely discussed or seen by the public, primarily for security reasons but also because these utilitarian areas often do not contain the most glamourous or noteworthy objects. Yet I would argue the spaces in and of themselves carry a history and represent changes and advancements in museum protocol, technology, and aesthetics.

At the White House, in an effort to modestly update curatorial storage rooms, funding was approved in 2018 for the long-overdue purchase of new archival storage cabinets for objects. The staff of the Office of the Curator collaborated with a museum storage systems consultant to select equipment for installation in 2019.

However, in early 2019, the Curator’s Office was informed it would need to completely empty its storage rooms to allow for the completion of a White House infrastructure project. Everything from floor to ceiling, including approximately 1,400 objects of diverse media, would need to be

removed from the rooms during a three-week period. Additional funding was subsequently awarded for a complete renovation—much more extensive than originally envisioned—with the stipulation from Timothy Harleth, the chief usher at the time, that the finished product be aesthetically and functionally pleasing—an area where he would feel comfortable bringing the first lady to see the collections.

Betty Monkman, who served in the Office of the Curator from 1967 to 2002, recalls that the storage rooms had not been renovated since 1983. A complete renovation was clearly a rare opportunity to hire an architectural firm to design a customized state-of-the-art, museum-quality storage area for a growing collection. An updated storage area would be a timely accomplishment ahead of the approaching American Alliance of Museums reaccreditation process that the White House would undergo in 2022–23. While working under such a very short timeline overwhelmed the staff,

A view through one of the new rolling storage carriages captures the mirrored gilded plateau made by Jean-François Denière and François Matelin in Paris and ordered for the State Dining Room by James Monroe in 1817.

BELOW

Painting racks in the room prior to the 2019–20 renovation reflect the work done during a renovation nearly forty years earlier, in 1983.

the chance to improve space utilization, combined with a modern streamlined design, justified the effort as practical, functional, and a significant improvement for curatorial operations. The availability of advanced technologies—temperature lighting,1 key card entry, compact storage systems, a smaller and more efficient air-handling unit, and modern, sustainable flooring—would improve overall collections care practices. Staff viewed this challenging project as the time to examine each object for condition and, occasionally, for first-time photography. It was also an opportunity to properly pack and send to long-term, off-site storage those objects that were extremely fragile or in unusable condition, enabling the remaining objects to be stored on-site properly. Museum colleagues from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, and Philadelphia Museum of Art generously invited curatorial staff to tour their recent collections storage renovations and offered helpful advice on equipment selection, documentation, and lessons learned.

In April 2019, after only a few weeks of planning meetings with architects and consultants, curatorial staff, with the assistance of art-handling contractors, started the initial process of removing

and processing collections from the rooms in a multistep, phased approach. Some objects were packed individually in travel frames,2 customized boxes, and crates designed and produced by a fine arts transit company and then transported to the Executive Support Facility for temporary (oneyear) and long-term storage. Object counts taken by curatorial staff included 256 framed paintings and prints, among them works by James McNeill Whistler and Mary Cassatt; 287 pieces of glassware, many of them from the Lincoln and other nineteenth-century services; ornate mirrors and looking glasses; ceramics; table lamps and other lighting fixtures; photographs; sculpture, including the extremely fragile porcelain birds created by Edward Marshall Boehm; eighteenth-century crèche figures; and furniture, including the bill-signing table, eagle lectern, and a spare Oval Office armchair. The very fragile looking glasses, ornate frames, and Boehm birds consumed a huge footprint in the room and, although not on display, had never left the White House because of their extreme fragility. For decades, it was safest to leave them in place. All objects were emptied from the rooms by May 22, 2019. The rooms were then completely gutted.

The storage rooms had formed a horseshoe-shape until the mid-1990s, when the center utilitarian storage room was repurposed to become a packing and study room for objects to be shared by curatorial and operations staffs. In this carpeted room were a large air-handling unit, packing table, and office supplies. The adjacent rooms still had mint green tiled walls dating to the Truman era with “No Smoking” signs, once penned by White House calligraphers, on the east and west walls—a reminder that smoking was once allowed indoors.

When a section of the packing room wall was removed, workers discovered a wall-size railroad map of the Soviet Union underneath the drywall, its installation date unknown. The wall section had a layer of steel sandwiched in it, perhaps indicating the room was once used as a meeting room. The bottom border of the map identifies it as: “Prepared by the Army Map Service (AM), Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army, Washington, D.C. Copied in 1951 from material furnished by the Central Intelligence Agency.” A curious discovery, the map was placed in storage as an ephemera object for possible future display.

Plans for a phased-in reinstallation of curatorial storage were interrupted in June 2020 when

another infrastructure project required staff to empty an additional storage room containing more than 5,000 objects of ceramic, silver, and glass. In an effort to inventory and reorganize the collections as they were being moved, curatorial staff and contractors photographed the objects, many of which were part of larger historic china and glassware services, and assessed them for condition and use. The cabinets were relocated and then refilled, but some objects were packed for transit to long-term off-site storage. The decision was made to continue the practice, initiated after 9/11, of dividing pantry services between the White House and the Executive Support Facility so that no one service could ever be lost or destroyed in the event of a disaster.

A major challenge during both storage renovation projects was the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown in 2020 and 2021. The shutdown delayed the first curatorial storage project but work never completely stopped. Rooms were outfitted with flooring, lighting, and storage equipment in late 2020 and early 2021. In anticipation of a growing collection, only objects deemed necessary for on-site storage (a much smaller percentage than what was initially in the room) were returned in late March 2021.

The architects wanted to open up the space for improved workflow and aesthetics. The spaghettilike tangles of conduits, pipes, and ductwork were either removed or hidden closer to the ceiling. Portions of the east and west walls of the packing room were removed to create walkways, and a wall was built where the interior north doors led into the original storage area. The much smaller air-handling unit, equivalent to the size of a refrigerator, was placed behind a sliding paintings rack, where it could be camouflaged by a framed object.

Selection of a durable, easy to maintain, yet neutral flooring material proved to be a challenge. After evaluating many products, which were beautiful but not appropriate for safely rolling carts with fragile objects, a sustainable linoleum was selected and a waterjet custom border was designed by curatorial staff for the new revitalized packing room.

Temperature lighting in the rooms enables the lighting of other locations to be re-created, eliminating the need for objects to leave storage for consideration.3 LED track lighting replaced the halogen system in the packing room, and adjustable swing-arm LED lighting mounted around a wall rack on the east wall is readily available for conservators and staff to study and treat objects.

OPPOSITE TOP AND RIGHT

The newly refurbished storage room features an open work space with a smaller air handler camouflaged behind a storage rack, LED track lighting, and fresh durable linoleum flooring.

OPPOSITE BELOW

Adjustable swingarm LED lighting mounted around a wall rack on the east wall allows conservators and staff to study and treat objects.

The storage systems consultant advised on efficient space utilization with a plan for integrating compact storage, rotary shelving systems, open shelving, paintings racks, and even the reuse of some existing cabinets. Stationary racks mounted onto some walls would house extremely fragile objects such as gilded looking glasses and clocks that require stability. To accommodate the priorities of operations staff, an open shelving system was designed near the door so that frequently moved objects, such as the eagle lectern, State Dining Room table leaves, and bill-signing table would be easily accessible.

RIGHT

Paintings of varying sizes are stored on sliding racks while not on display in the White House.

OPPOSITE

The rolling carriages in the refurbished storage room (top) allow for secure storage of objects while optimizing limited space. Lamps are stored securely in the unit seen here, while a fragile looking glass hangs safely on a wall mounted rack. Such frequently used objects as the eagle lectern and bill-signing table are positioned near the door for easy access (below).

Renovation of the second, more narrow storage room presented challenges, especially in 2020. The need for appropriate social distancing meant that fewer contractors were hired to assist the curatorial staff, slowing down the deinstallation and packing process. This work required careful focus in a small space.

Nevertheless, curatorial staff seized the opportunity to improve collections care and worked with a contractor to design and produce customized storage boxes to house State Service teacups, bouillon cups, and cream soup bowls. These lidded, archival, individual-celled boxes replaced utilitarian plastic tubs and were uniformly labeled for easy identification by curatorial and butlering staff and stored in designated cabinets for easy retrieval. The improvements would also enable staff to perform the annual inventory of pantry objects in a more timely and accurate manner.

Funding was approved to replace the flooring with the same sustainable linoleum sourced for the previous renovation as well as to acquire twelve new visual storage cabinets designed for museums. Funds were also secured to hire the same fine arts handlers. The move-out deadline of August 1, 2020, was met in July. The room was completed, and objects were installed in new cabinets by January 15, 2021, five days before Inauguration Day.

The collections storage renovations were demanding, with infrastructure projects dictating major collection moves that mandated expedited planning and execution time. To make it all possible, the Curator’s Office was fortunate to receive generous funding and support from the Executive Residence and the White House Historical Association. Talented and flexible contractors who were willing to assist at the last minute during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown enabled the successful and timely completion of the projects. Moving the collections in two different storage areas forced curatorial staff to appreciate the history and contemplate the future of the rooms themselves while carefully considering each object stored there. In the end, the opportunity to start from scratch to design useful and functional storage spaces and to address and rectify museum object “demons” were “once-in-a-career” gifts for this curatorial staff.

1. Temperature lighting refers to the warmth or coolness of light emitted, warmer light being more yellow, cooler being more blue. Our goal was to have a system that could mimic a room in the White House whether it be in the Private Quarters, with warmer lighting similar to a sunlit room, or a public room, with only one window and limited natural light, so that an object in storage could be viewed under the same lighting as in the intended exhibit location and thus eliminate the need to move an object in and out of storage to view as it would appear on display.

2. A travel frame is an inner frame onto which an object can be secured for transit, often inside of a crate. The frame can be utilized for multiple similar sized objects fitted with a clip system to secure the objects onto the frame. Travel frames are cost effective because they can be reused.

ABOVE

Customized archival storage boxes with individual cells now hold State Service teacups, bouillon cups, and cream soup bowls, replacing the plastic tubs used in the past. Uniform labeling allows for easy identification by curatorial and butlering staff.

OPPOSITE

Customized museum cabinets and shelving on the floor store figures from the White House’s elegant and elaborate Neapolitan crèche as well as easels, archival boxes, and other supplies.

in 1901, following the cession of the Philippines to the United States by Spain in the Treaty of Paris that ended the Spanish-American War, President William McKinley issued an executive order permitting the United States Navy to enlist Filipino men. For many who chose to volunteer, active service in the navy offered the opportunity for adventure and advancement beyond what they could expect to find at home. Most of these Filipino recruits were assigned to serve as stewards aboard U.S. Navy ships.

One such recruit, Irineo Esperancilla, would ultimately serve a long and distinguished career as a “special steward attached to the persons” of four U.S. presidents. From 1930 to 1955, he witnessed some of the most consequential chapters of American history unfold as he attended to Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower in the White House itself; aboard the USS Arizona, USS Augusta, USS Houston, USS Indianapolis, USS Iowa, USS Potomac, USS Sequoia, and USS Williamsburg; at such presidential retreats at Camp Rapidan, Hyde Park, Shangri-La (now Camp David), the Little White House, and Gettysburg; and on presidential campaign trains that stopped in nearly every state in the nation. During years of war and peace, Esperancilla traveled with the presidents to Europe, Africa, South America, the Middle East, and the

Virgin Islands, and on vacations to such distant places as the Galapagos Islands. He served whiskey to Winston Churchill, prepared food that Joseph Stalin refused to taste, and ensured countless world leaders and diplomats were made comfortable during visits with the presidents. From 1945 to 1955 as chief steward of the U.S. Navy he was in charge of all stewards serving the first families.

With the help and encouragement of his wife, Maryann, Esperancilla drafted a memoir, and saved photographs, letters, and mementos documenting his career. He explained, “I know that I did not have any part in history, but I was in the rare position to closely observe these four leaders of the greatest democracy in the world (not just as historical figures, but also as human beings). I feel, therefore, it is my duty toward the American people to put into writing my recollections of the great men whose service is the glory of my life, that of my children, my children’s children, for the ages to come.” Although his memoir was not published in his lifetime, his granddaughter, Melinda Dart, took on the task of compiling and editing his story, which she self-published in 2022 as a book entitled A Glimpse of Greatness. In the interview that follows she shares her grandfather’s story and her own experience creating the book with Marcia Anderson, editor of White House History Quarterly.

LEFT

A postcard captures a view of Irineo Esperancilla’s first homeland. Fishermen are seen at work on the Iloilo River, lined with thatchedroof houses along the river bank, Panay Island, the Philippines, 1910.

PREVIOUS SPREAD

Irineo Esperancilla is seen in a photograph that accompanied a 1938 press release announcing his selection as President Franklin Roosevelt’s personal chef (p. 34) and in uniform (p. 35).

After joining the United States Navy, Esperancilla first served as a steward on the first USS Noa, a Clemsonclass destroyer.

MARCIA ANDERSON: Melinda, could you start by telling us what led your grandfather, Irineo Esperancilla, from the Philippines to a career in the U.S. Navy?

MELINDA DART: Yes. My grandfather loved his homeland, but he wrote that he was always fascinated by the “open sea and the exalted history of the United States.” He longed to see America and what it had to offer him. When the USS Noa arrived in the bay of Iloilo in 1925, near his hometown, he took the opportunity to answer his call to serve. Without even telling his parents, my grandfather enlisted for four years in the United States Navy. He was immediately assigned as a temporary steward. His first few years were typical for a navy recruit, but my grandfather took great pride in his job as a navy steward.

In 1930 your grandfather was assigned to work at Camp Rapidan for President and Mrs. Herbert Hoover. Did he imagine his assignments would include working for the presidents when he joined the navy?

Being assigned to serve President and Mrs. Hoover was something he never would have imagined. Considering the circumstances that preceded this assignment, he believed that it must have been his God-given destiny. You see, prior to receiving these orders, my grandfather had served a disciplinary

action for being considered AWOL when his leave status ended. He had been visiting his family in the Philippines and sent a wire telegram requesting an extension; he did not receive a reply. His grandmother had passed away, and he stayed to attend her funeral. Upon returning to the ship, my grandfather was given “forced residence in the brig” for thirty days. He thought his career might be over, but you can imagine his sigh of relief when he was released after fifteen days for good behavior. Receiving orders that he would be one of the stewards serving President and Mrs. Hoover was beyond his every dream!

It was interesting to read that several presidents gave your grandfather nicknames. Why was that, and which name should we use in this interview?

My grandfather began his memoir by stating his full name, Irineo Esperancilla, so the nicknames given by the presidents were significant to him. My grandfather described his first encounter with President Roosevelt aboard the presidential yacht, the USS Sequoia. As his personal attendant, he reported to FDR aboard the ship, giving his first and last name (while checking his strong Filipino accent). The president immediately told my grandfather that he would never be able to pronounce that name and asked if he could simply call him “Isaac.” So Isaac he remained

for his twelve years of service to FDR.

When my grandfather was promoted through the ranks to chief steward, the presidents who followed called him “Chief.” Another nickname mentioned at the end of the book was “Renny.” This was the name my grandmother called my grandfather; I heard it often growing up. I also noticed that throughout the collection of materials my grandmother kept, she had written my grandfather’s initials while labeling and referencing items, such as “IE’s notes” or “Letter to IE.” I would like to use his initials, IE, for this interview because they reference his full name.

After working for President Hoover, IE was assigned to serve Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower. His role immersed him in the most significant events of the twentieth century. Tell us about the records he kept of his career and why he felt it was important to preserve the history he witnessed.

My grandfather kept so many original documents and artifacts related to his time in service to the presidents! There is a collection of a variety of menus from presidential meals. These include the “President’s Mess Thanksgiving Dinner” from the USS Indianapolis in 1936 and a dinner menu from Key West, Florida, with President Truman in 1951. A Christmas dinner was also in this collection, titled “Season’s Greetings from the USS Williamsburg.” Turkey gumbo, baked Smithfield ham, and Parkerhouse rolls were items on this presidential menu. Others in this collection even had IE’s notes on what to serve first, second, third, fourth, and last. I also discovered typed menus on paper for meals aboard the ships, mainly the USS Williamsburg. Along with the menus, I found several copies of military orders, detailing IE’s trips with presidents abroad, as well as his responsibilities aboard presidential yachts and at the Little White House in Key West. One document that stood out to my family and me was IE’s orders aboard the USS Potomac with President Roosevelt. These orders specified that he was not to leave the immediate vicinity of the president unless ordered to do so, and in the case of “Abandon Ship” my grandfather was to assist the president.

In addition to orders, IE kept other important documents. I found lists that included stewards’ names and duties he had recorded, mainly during the Truman years. Original booklets from Camp

Rapidan, the USS Williamsburg, and “Trips of the President of the United States in 1948” were among the items preserved. There were also memos from navy commanders and the naval aide to the president, commending IE’s “almost legendary service.” Letters of appreciation from Presidents Truman and Eisenhower were a special part of IE’s historical collection.

Among these records and artifacts were pictures of the Filipino staff and crew from the USS Williamsburg at Key West and at Camp David. His collection even included an ashtray and patch from the USS Williamsburg, newspapers signed by FDR and President Truman, and personally signed photos from President and Mrs. Eisenhower.

My grandfather was fully aware that history was unfolding before him as he quietly served behind the scenes. He knew that by preserving everything he could, he would be able to tell another side of the story, another side of history—the history that we don’t always see.

Although I had this historical treasure for a few years, I never had the time I truly needed to spend going through it. During the pandemic, I realized my opportunity had come; I opened my grandmother’s trunk where everything was kept. As I began to read and process the original manuscript, notes, letters, and other records, I knew that this had now become my God-given destiny. Just like my grandmother, I knew this was a story that had to be told, no matter what it took.

To begin, I simply took out my laptop and started typing my grandfather’s manuscript. Word by word, page by page, I created a digital form of the original. Once this was complete, I sorted through the material—the letters, memos, pictures, and notes. If there was a reference in the manuscript pertaining to something I found, I added details in the appropriate place. I researched the events my grandfather described to learn more about the history he witnessed.

I wanted to keep my grandfather’s perspective, vision, and voice for the book authentic. His words rang true to me as I compiled the material: “I am not a historian, only a modest witness to history; therefore, it is not my job to describe dates and accounts of historical events. My aim is only to contribute to history my personal observations.”

OPPOSITE

IE preserved the story of his White House service with his own memoir. His granddaughter Melinda Dart would later digitize his typewritten pages (opposite) as she began to compile his biography in book form.

OPPOSITE

IE’s collection of newspaper clippings, memos, menus, and other ephemera help to tell the story of his years of service.

I love the title of the book, A Glimpse of Greatness. Is it a quote from the text?

Thank you, Marcia. A Glimpse of Greatness is not an exact quote from the original manuscript, but IE used the word “greatness” often when he described the presidents. After learning how he contributed “to the ease and success of all the functions involved” behind the scenes at the White House and other places he served, it was clear to me that my grandfather also carried that greatness. In the preface I described the book as the amazing experience of a Filipino American and his comrades and how they were destined to be that “glimpse of greatness” that was never recorded in the history books about four of the nation’s presidents.

Among the things that come through so strongly in the text is the pride IE took in his service, his humility, and his respect for the presidents he served. His memoir is written without any hint of judgment or criticism. What do you think was behind his perspective?

I appreciate your acknowledging this. My grandfather’s pride in service, humility, and respect for the presidents stood out to me as well. I believe IE’s perspective was rooted in his belief that he was called to serve a greater purpose in history. This call to serve the presidents had nothing to do with position, politics, or party; he was committed to serving them to the best of his ability simply because that was his job—to work behind the scenes for the men who held the office of the presidency. His work also allowed him to gain a unique perspective.

While serving President Hoover at the beginning of IE’s career, he discovered that “despite all its glory, it is very hard to be the president of the United States.” IE considered it a privilege and saw the men he served not just as historical figures but also as human beings. His observations and positive interactions with the presidents resulted in this genuine perspective that he summarized in one sentence: “He who reaches the presidency of the United States is not just a great human being, but also a great gentleman.”

You were just three years old when IE died. Do you remember him?

Yes, I do remember him. The nickname my siblings and I gave him was Pop-Pop. I remember him helping my parents by taking my older brother and sister to school. I would happily tag along, knowing

he would take me to his home afterward. I have clear memories of eating breakfast at my grandparents’ house, where he made me cream of wheat. Of course, I had no idea that the hands that prepared my breakfast had also prepared meals for presidents and world leaders such as Sir Winston Churchill. To me, he was simply my Pop-Pop.

Was it your grandmother who encouraged you and your family to learn about grandfather’s career?

Yes, my grandmother kept my grandfather’s legacy alive in simple ways. She proudly displayed his picture that is on the front cover of the book in her home for as long as I can remember. She talked about my grandfather’s service often, recalling notable stories including the cracked chimney incident with Mrs. Hoover and the run-in with Joseph Stalin in Tehran. My grandmother also did research of her own, looking for books or articles that could have possibly acknowledged her husband who served the presidents so well. She knew what an important role he played in history and believed that this was a story worth telling. With notes addressed to me throughout the collection of materials, my grandmother hoped that I would one day share it with the world.

It is clear from the letters and documents you share in the book that the presidents appreciated the dedication and efficiency of IE. Tell us about the mutual respect that they shared.

Just as my grandfather honored the office of the presidency, I believe each of the presidents honored the “office” or roles of those assigned to work at the White House, presidential yachts, and retreats. IE faithfully performed his duties behind the scenes as the presidents performed their official duties. I believe they shared an understanding that although their roles were vastly different, each was valued and important. This understanding created an environment in which those who served and those who were being served genuinely treated each other with kindness and respect. From the “usual friendly” greetings of President Hoover to the meaningful conversation with President Eisenhower, IE’s memoir is filled with stories that reflect this mutual respect and understanding on a daily basis.

Throughout his White House career, Irineo Esperancilla was in many group photographs of the Filipino stewards who served the presidents. He is seen (above), standing to the right of President Frankin D. Roosevelt aboard the USS Houston, 1936. At left he stands on the far left in Key West while serving President Harry S. Truman.

President Truman joins the Filipino stewards aboard the USS Williamsburg. IE is in the center of the second row, in front of the president.

Shortly before his retirement, IE posed with Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower, his fourth and last president and first lady, at Camp David. He is seated second from the left of the president, 1955.

Irineo Esperancilla served President Franklin D. Roosevelt for his entire twelve-year presidency. Among the mementos IE saved from that period are the menu for the Thanksgiving Dinner served in the President’s Mess aboard the USS Indianapolis, the cover of This Week magazine signed for him by the president, and his orders for service to the president dated June 3, 1940.

Esperancilla’s ephemera collection from his years of service to President Harry S. Truman includes many menus from dinners he planned and served on the USS Williamsburg and at Key West. President Truman wished IE good luck in an autographed copy of his photo on the cover of Parade.

Your grandfather also greatly admired each of the first ladies he served. He described Lou Hoover as gracious, kind, and caring. He remembered Eleanor Roosevelt as a friendly, caring person who was always doing something for others. What can you tell us about IE’s relationships with these two women and with Bess Truman and Mamie Eisenhower?

My grandfather truly embraced every part of his job, which included serving these first ladies. His relationships with each of them were filled with that same mutual respect that was evident with the presidents he served. I found it both heartwarming and fascinating to read the untold stories of the first ladies and the stewards who served them.

Since Camp Rapidan was IE’s first assignment at a presidential retreat, he was immediately able to observe and discern the genuine kindheartedness of Mrs. Hoover. I believe she also embraced her duties as first lady and enjoyed talking to the stewards as she took charge over them on each visit. Mrs. Hoover valued the Filipinos as navy stewards, but, more important, as human beings. She listened to their story of discrimination in Culpeper, Virginia, and took action on it. She led by example as she brought guests to the kitchen and complimented the Filipino staff. IE also wrote about a smoking cracked chimney he rushed to repair with Mrs. Hoover. The caring relationship shared was evident when Mrs. Hoover rang the bell and waited for my grandfather to arrive. The crack was patched with flour, water, and a conversation with Mrs. Hoover. At the end of her term, she took the time to gather the stewards and show gratitude for the fine service they provided. My grandfather became a part of this untold history of this first lady. I do not think her graciousness came as a surprise because IE believed that if she was a first lady, then she must also carry that same greatness that he observed in her husband.

While serving Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, IE became a familiar face to the first ladies. He experienced Mrs. Roosevelt’s kindness and wrote that everyone always felt at ease in her presence. Mrs. Truman’s kind, quiet nature was observed often during my grandfather’s time at Key West and aboard the presidential yachts. IE was filled with emotion during his farewell to President and Mrs. Truman.

As for his time serving Mrs. Eisenhower, my grandfather wrote about a special memory that

truly touched his heart. Once at Camp David, the first lady arrived at the retreat and presented the Filipino stewards with a basket of fresh mangoes. He remembered that she spent some time in the Philippines during the president’s military career and knew that Filipinos enjoyed this fruit. IE recalled other special moments with Mrs. Eisenhower as well, including planning a successful menu with her at the Geneva Summit in Switzerland and helping her granddaughter sign the guest book at Camp David.

After his retirement, IE would occasionally see Hoover, Truman, and Eisenhower, but he wrote, “I can no longer see the boss whom I served for the longest time, during the most beautiful years of my own life, the late President Roosevelt.” Do you have a sense of how Roosevelt’s death affected your grandfather? And did he play a role in his funeral?

Yes. When I read this part of the manuscript, it brought tears to my eyes. With the death of President Roosevelt, my grandfather had suffered a great loss.

IE hands a newspaper to First Lady Mamie Eisenhower at Camp David. He fondly remembered her gift of fresh mangoes to the Filipino stewards, a favorite fruit of many from the Philippines.

He wrote that there were “no words that can describe the feelings of a man who spent twelve years of his life with this extraordinary human being.” Spending almost every one of those days serving this president, witnessing his superhuman strength despite his physical limitations, IE felt that his own life had changed forever.

Although my grandfather did not write about having a role in the funeral, he rushed to the White House to wait for the body of FDR to arrive. IE stood before the open coffin of his former boss, commander in chief, and friend, unable to believe that he would no longer hear this president call the name Isaac again. FDR’s daughter was there and touched my grandfather’s arm, whispering, “I know how you feel, Isaac.”

After the president’s burial at Hyde Park, the Filipino stewards received orders to stay at the White House to assist with packing and moving the Roosevelt family’s belongings. This was a difficult task for my grandfather; he wrote that FDR’s “voice that had called me often throughout the past twelve years was silent for eternity.” IE also expressed his gratitude for the opportunity given to him to go to Hyde Park to see the president’s grave; he spent time visiting Mrs. Roosevelt after this great tragedy.

IE wrote that President Truman was “like some good neighbor of yours” and that he had “simplicity in greatness.” Do you have any favorite stories from the Truman years?

I have so many favorite stories that my grandfather wrote about in the Truman chapter. I’ll start with the discovery of President Truman’s simple greatness aboard the USS Augusta. When the president first came aboard, he gave the order that no crew member should come to attention when he met the president. IE had the great pleasure of observing President Truman walk around the ship, making personal connections with service members, regardless of rank. He asked where they were from, signed letters, and he even ate meals with the seamen. President Truman refused to be served at a table while aboard the ship; he stood in the self-service waiting line with his tray in hand. Regarding these simple actions, IE wrote, “Here was living proof that in the American democracy, the presidency has nothing to do with birthright or other social privileges, but it is the right of any citizen who is qualified by his talents and honesty.”

Another favorite story from the Truman years was aboard the USS Williamsburg. IE truly loved serving the president on this yacht. He took great pride in his duties and preparations for the presidential quarters and kept them in “tip-top shape.” When President Truman entered for inspection, I can envision him smiling at my grandfather, shaking his hand, and offering kind words of a job well done.

One of many noteworthy stories with President Truman was the laying of the cornerstone of the United Nations Building in 1949. IE accompanied the president to New York and called it an “especially great day”; General Carlos Romulo of the Philippines, the president of the General Assembly of the United Nations, was also there. My grandfather witnessed the historic exchange of compliments of these two presidents. “General Romulo, you are the president of the greatest organization in the world,” my grandfather recalled his commander in chief saying. General Romulo replied, “You are the president of one of the greatest countries in the world.” My grandfather was proud to be an American citizen who was born in the Philippines.

I must mention one more story about President Truman that occurred after his time in office. He was visiting the Library of Congress where my grandfather worked as a guard after he retired. Truman recognized IE immediately, greeted him, and shook his hand. A January 1959 article in the Washington Post described this reunion saying that, “Mr. Truman had a warm handclasp for an old friend.” Their picture was taken on that day. IE sent the photo to the former president, requesting his signature, along with a box of candy for Mrs. Truman’s birthday. President Truman signed and returned the photo with a letter expressing how much he enjoyed seeing IE in Washington.

Your grandfather first met Eisenhower while he was traveling with Roosevelt during World War II. IE served primarily at Camp David during the Eisenhower presidency and was especially impressed by Eisenhower’s culinary skills. What strikes you as special about this time?

During these final years of service to the presidents, my grandfather continued to perform each of his duties with excellence and ease. He described President Eisenhower’s culinary skills as a highlight at Camp David. IE’s job was to prepare and heat the charcoals for the outdoor grill. The president

immediately followed, tying a steward’s apron around his waist and placing the steak on the grill. What strikes me about this special time is that even during the last years of my grandfather’s service, he continued to look for the simple greatness in each president he served. IE delighted in observing President Eisenhower as his guests complimented him and asked for more of his famous tenderloin.

Your grandfather didn’t discuss his own personal life in his memoir, but it is hard not to wonder how he found time to marry and raise a family during the years he spent long hours serving the presidents.

Although I do not have the details of how my grandparents met, I know that family was important to them. As my grandfather spent time away from home to serve the presidents, he knew that his family contributed to his success. My beautiful

grandmother was his glimpse of greatness on the home front. Her quiet strength as a military spouse allowed my grandfather to fully embrace his service to the presidents. Their daughter, my mom, Ann, lived her whole life as a navy family member. She met and married a navy recruit from the Philippines, my dad, Johnny Paje. He was also one of the many dedicated Filipinos who quietly served behind the scenes at the White House. The basement kitchen, which serves the White House staff, is named JP’s Cafe in honor of him. Although I was proud to have a dad who “worked at the White House” and a grandfather who “served four presidents,” I never fully realized their contribution to presidential history. Now my younger brother, Joseph Paje, plays an important role in and around the White House as the operations foreman. He carries the simple greatness of those before him, faithfully serving behind the scenes.

IE married Maryann Esperancilla in the 1940s. Their daughter Ann married Johnny Paji, a navy recruit from the Philippines who served in the White House as a cook for many years. The staff kitchen is now known as JP’s Cafe in his honor. Their grandson Joseph Paje now serves on the White House Residence staff as the operations foreman, and their granddaughter Melinda Dart, is editor of her grandfather’s memoir.

Following his retirement in 1955, IE worked to preserve his memories of the history he witnessed during his years of service to the presidents. In 1959, he shared his story with Eugene Gonda for a feature story in Look magazine. Gonda and IE are pictured outside of the White House during the interview.

It was during the Eisenhower years that IE chose to retire from the navy at about age fifty. Why do you think he made that decision?

I believe my grandfather’s decision was based on his simple desire to live a “normal” life and be home with his family. Retiring from the service at this time in his life would give him the opportunity to secure employment and enable him to be home. Seeing three of the four presidents with their adult children, I think IE knew that the time for him would come when his own children would soon be adults. In his memoir, he described a final conversation with a sitting president about retirement:

I remember clearly the president looked at me and said, “What is this bad news I hear? Are you leaving us, Chief?”

With all the guests now listening I replied, “Mister President, I am retiring now because I would like to get another job before I am fifty years old.” President Eisenhower then asked me how much my retirement pay would be, and we had quite a meaningful exchange of ideas and thoughts about the retirement conditions for service members and the strict limitation of

their earnings while receiving a pension from the government. Then the boss gave me a warm handshake, followed by his guests, and I left the room. This conversation with President Eisenhower was profound to me. I felt that he was genuinely concerned and understood the challenges of a man in the military like me.

This issue of White House History Quarterly is titled “Behind the Scenes,” a fitting title for your grandfather’s story. After publishing A Glimpse of Greatness, do you have a sense of the significance of preserving the stories of those who served behind the scenes?

Preserving the stories of those who served behind the scenes has never been more important to me than it is now. I have a greater understanding of how the untold stories are necessary to gain insight on major events in history and the smaller events that surround them. These stories provide a unique perspective. I also think it’s important to recognize and honor those who served behind the scenes; the tasks they performed were invaluable to the ease and success of both daily living and major events of presidential life.

Have you learned more about other Filipino stewards as a result of publishing the book?

Publishing the book has shed light on the untold stories of those who served behind the scenes during the presidencies of Hoover through Eisenhower. As a result, some family members of the stewards who served have reached out to me to express gratitude for the insight they gained from reading A Glimpse of Greatness. I am continuing to research to learn more about those Filipino stewards who served during my grandfather’s time in service, since there is so little information recorded. I am currently in the process of working on another book to recognize the contribution of the Filipino stewards who served the presidents.

My grandfather was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. Our family visited often with my dear grandmother when I was growing up. We continue to visit and share the untold stories with our own children. I believe that they will also bring to the world their own glimpse of greatness, as they carry the legacy of their great-grandfather, a Filipino navy steward who personally served behind the scenes of four of the nation’s presidents.

Yes, I’d like to close with this excerpt from a letter from the naval aide to the president to IE, 1955, which summarizes my grandfather’s service:

I cannot but feel the deep sense of loss to this office, to the Navy, and to all of us aware of your faithful and almost legendary service to Presidents Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman and finally President Eisenhower. When all the histories for this era are written, you may indeed have the gratification of reading between the lines and knowing to what extent you played an important part in the making of these histories. During the famed trips of the former Presidents, and in helping them fulfill engagements with the distinguished guests they have entertained and were entertained by in the United States and in other countries—your knowledge, understanding, leadership ability and the necessary tact and courtesy required, which you never failed to exhibit, contributed much to the ease and success of all the functions involved. There was never a concern as to the

successful outcome of any services rendered by you. Your assured manner and unvarying competence left nothing to be desired. For all this you have a right to feel singularly rich in memories of a job well done.

Your service record, while officially correct as to your outstanding service, does not give you full justice for the many unwritten talents contributed by you to each instance of your assigned missions. Were detailed credits to be written I’m sure they would fill many pages. It is understandably not possible to list them all.

Following his retirement from the navy, IE remained in touch with Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Hoover. In 1959, while working as a security guard at the Library of Congress, he crossed paths with Truman who was attending an event. A photo of their encounter was published in the Library’s Information Bulletin.

A memo to IE from the Naval Aide to the President, dated June 25, 1955, summarizes IE’s accomplishments during his years of “faithful and almost legendary” active service to Presidents Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower.

DAVID RAMSEY

DAVID RAMSEY

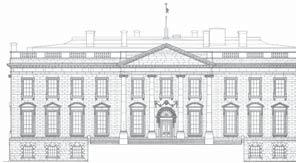

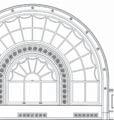

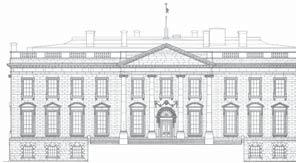

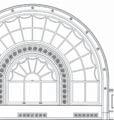

the late historian william seale often stated that Abraham Lincoln sanctified the White House.1 Various plans after Lincoln’s assassination to either demolish it or replace it were proposed, but thankfully never implemented. Many of the presidents and first ladies who followed Lincoln revered the mansion as historic, even quaint, with a nostalgia for the Founding Fathers. This reverence for the White House was also generated from the emotion that the national events of Lincoln’s administration, Lincoln’s great acts, and his personal tragedies induced. No event engendered more emotion than his assassination, his lying in state in the East Room, and his White House funeral. This article attempts to re-create—and represent, through computer technology—what firsthand sketches and later published drawings depicted of that grievous event.

A widely distributed period engraving, first published in Harper’s Weekly on May 6, 1865, depicts the funeral with Mary Lincoln standing at right in front of the coffin in heavy mourning dress, although she actually did not attend the service but stayed in the Private Quarters, overwhelmed by her grief. The artist had begun his sketch ahead of the event and assumed she would attend the funeral.

We have firsthand sketches and published drawings of the East Room at the time of Lincoln’s funeral that capture the essence of the room but omit interesting details that would have been apparent had the room been empty. On April 19, 1865, more than six hundred people crowded the darkened room, making it almost impossible for artists to document the mourning dress that had been thoughtfully and loyally created by the White House staff for the first martyred president. But we also have two written accounts that can help complete the details. The first document is background. The December 18, 1861, New York Herald, includes a description of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln’s redecoration of the room in the fall of 1861. Her work was regarded as a decorating triumph, and a later visitor to the White House found the carpet astonishing: “The most exquisite carpet ever on the East Room was a velvet one, chosen by Mrs. Lincoln. Its ground was of pale sea green, and in effect looked as if ocean, in gleaming and transparent waves, were tossing roses at your feet.”2

The most thorough description of the East Room in mourning dress is on pages 58–59 from the book created as the official record of the entire Lincoln funeral. Memorial Record of the Nation’s Tribute to Abraham Lincoln was written and compiled by Benjamin Franklin Morris and presented to James Harlan, the secretary of the interior in Andrew Johnson’s administration. These descriptions and numerous magazine illustrations inform the conjectural views presented in this article. Created by the author through computer technology, they aim to fill in some of the details of the furnishings in the East Room at the time of Lincoln’s funeral, as well as the mourning dress.

notes

The author wishes to thank Steve Larson and Jessica Marx of Adelphi Paper Hangings, LLC, for assisting with the Lincoln East Room wallcovering pattern by sharing a high resolution image of their “Renaissance Strapwork” pattern.

1. See, for example, William Seale’s Foreword to White House History, no. 24 (Fall 2008): 2.

2. Mary Clemmer Ames, Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital, as a Woman Sees Them (Hartford, Conn.: A. D. Worthington, 1873), 171.

The President’s house once more assumes the appearance of comfort and comparative beauty. Two coats of Pure white paint on the outside renew its right to be designated the “White House.” The interior, during the last six months, has been thoroughly cleansed and almost entirely reornamented. Very little new furniture has been introduced, as much of the old is yet substantial, having been procured in the time of Monroe, and is not only valuable on that account, but is really very handsome, from its antique style. Much of this old furniture, however, has been revarnished, and the chairs have been cushioned and covered with rich crimson satin brocatel [sic], tufted and laid in folds on the backs, rendering a modern appearance. Upon entering the great East Room two prominent things strike the eye—the paper on the wall and the carpet on the floor. The first is a Parisian style of heavy velvet cloth paper, of crimson, garnet and gold. It gives a massive appearance to the room, and is quite rich. In the daytime it seems rather dark; but when the soft light of the great chandeliers illuminates the room it develops its full richness and harmonizes to a shade. The carpet is an ingenious piece of work, not because of its rich quality or exquisite design, but because of the fact that it is in one piece, and covers a floor measuring one hundred feet long and forty eight feet wide. There is nothing flashy or extravagant about its appearance. The admiration of the beholder is not suddenly excited by a view of the whole surface, so ingeniously and beautifully are the various figures and colors harmonized. It is like a constellation of stars, where the beauty of one star is lost in the combined grandeur of the whole. It is a very heavy Axminster, with three medallions gracefully arranged into one grand medallion. As we walk over

its velvet surface from center to sides, or from corner to corner, the most chaste and beautiful surprises of vases, wreaths and bouquets of flowers and fruit pieces excite our love of true art. The carpet, in its mechanical construction, as well as in its artistic design, is a wonder. It was made in Glasgow, Scotland, upon the only loom existing in the world capable of weaving one so large. Mr. W. H. Carryl, of Philadelphia, went to Europe, and, after examining various patterns in different cities, including Paris and London, proceeded to Glasgow and designed this. His mission was a success.

The next attractive features among the ornamental, in the East Room, are curtains and drapery at the eight windows. The inner curtains are of the richest white needle-wrought lace, made in Switzerland. Over these and suspended from massive gold gilt cornices, are French crimson brocatels, trimmed with heavy gold fringe and tassel work. The embrace, or curtain pin, at the side of each window, is of solid brass and covered in gold gilt. The design is a commingling of banners, arrows, swords, an anchor, chain, &c., interwoven behind the American shield, upon the front of which is a raised figure of an eagle. Opposite the great east window of the room is the door leading to the promenade. In order to harmonize the interior appearance of the great East Room, this door has been curtained with lace and crimson brocatel, trimmed with gold fringe and tassel, to match the window opposite. The eight mirrors in the East Room are the same that have been there for years.

Source: New York Herald, December 18, 1861, 1.

The President’s Levee—Brilliant Appearance of the Guests—

The Foreign Ministers Present and Absent—

Rejuvenation of the White House, Etc.